- WHO Collaborating Centre on Investment for Health and Wellbeing, Public Health Wales NHS Trust, Cardiff, United Kingdom

Background: There is a growing recognition of the need to effectively assess the social value of public health interventions through a wider, comprehensive approach, capturing their social, economic and environmental benefits, outcomes and impacts. Social Return on Investment (SROI) is a methodological approach which incorporates all three aspects for evaluating interventions. Mental health problems are one of the leading causes of ill health and disability worldwide. This study aims to map existing evidence on the social value of mental health interventions that uses the SROI methodology.

Methods: A scoping evidence search was conducted on Medline, PubMed, Google Scholar and relevant gray literature, published in English between January 2000 and March 2021 to identify studies which capture the SROI of mental health interventions in high- and middle-income countries. Studies that reported mental health outcomes and an SROI ratio were included in this review. The quality of included studies was assessed using Krlev's 12-item quality assessment framework.

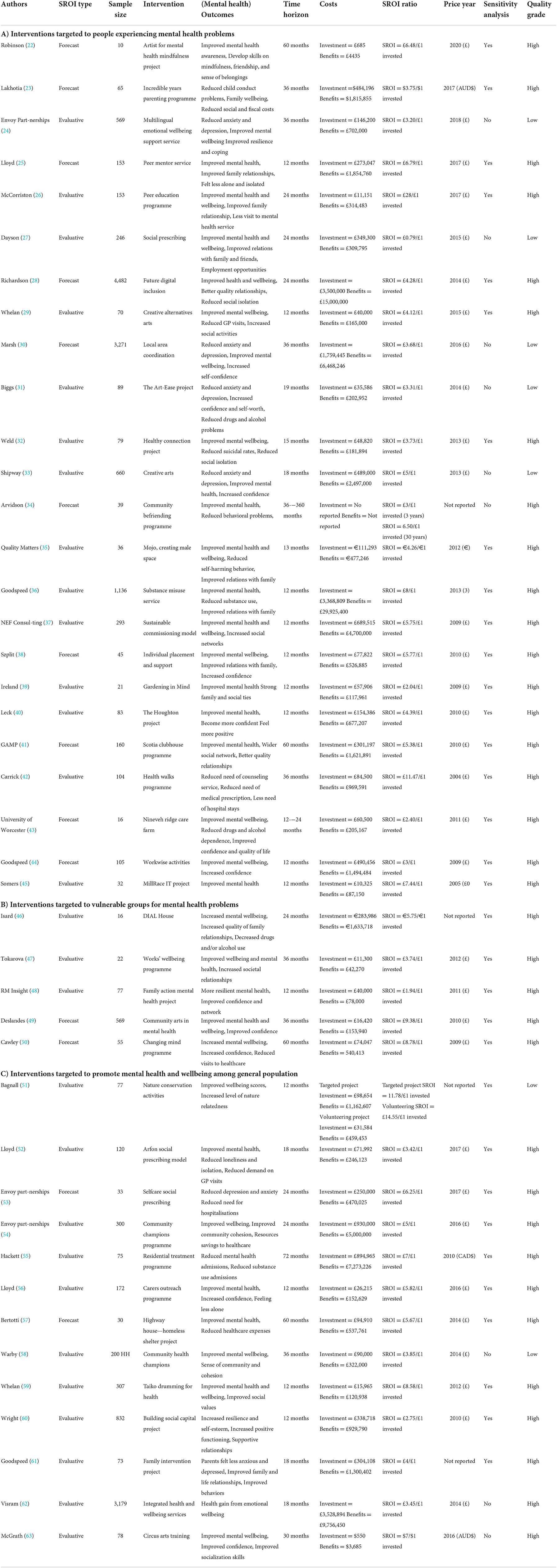

Results: The search identified a total of 435 records; and 42 of them with varying quality met the study inclusion criteria. Most of the included studies (93%) were non-peer reviewed publicly available reports, predominantly conducted in the United Kingdom (88%); and majority (60%) of those studies were funded by charity/non-for-profit organizations. Out of 42 included studies, 22 were targeted toward individuals experiencing mental health problems and the remainder 20 were targeted to vulnerable groups or the general population to prevent, or reduce the risk of poor mental health. Eighty-one percent of included studies were graded as high quality studies based on Krlev's 12-item quality assessment framework. The reported SROI ratios of the included studies ranged from £0.79 to £28.00 for every pound invested.

Conclusion: This scoping review is a first of its kind to focus on SROI of mental health interventions, finding a good number of SROI studies that show a positive return on investment of the identified interventions. This review illustrates that SROI could be a useful tool and source of evidence to help inform policy and funding decisions for investment in mental health and wellbeing, as it accounts for the wider social, economic and environmental benefits of public health interventions. More SROI research in the area of public health is needed to expand the evidence base and develop further the methodology.

Introduction

Mental health problems (MHPs) are one of the leading causes of ill health and disability worldwide (1, 2). One in four people experience mental health problems at some point in their lives, and many of them go undiagnosed (3). MHPs are major contributors to the global burden of disease, with the share of about 14% of years lived with disability (YLDs) and 4.9% of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2018 (4). There is huge imbalance between health burden, financing and service delivery in mental health in several countries with different income levels (5).

MHPs cause major economic consequences in terms of treatment, productivity and welfare/benefits to individuals, families and wider society (6). It is estimated that MHPs will cost $16 trillion US dollars (equivalent to £11 trillion, price year 2010) to the global economy over 20 years by 2030 (7). It is also estimated that MHPs cost the UK economy between £70–100 billion a year, about 4.5% of gross domestic product (8). The latest estimate by Deloitte showed that MHPs cost the UK employers between £33–42 billion a year (9).

Several interventions have been conducted to improve mental health and wellbeing across the life course (10). The economic evaluations of such interventions have also been well studied to see whether these interventions are financially worth-investing (11–14). However, these evaluations have not sufficiently captured the wider social value and impact of the interventions. One of the common evaluation tools to capture the wider outcomes, impact and related social value could be the Social Return on Investment (SROI) analysis (15).

SROI is an analysis framework to identify, measure and report the social, economic and environmental benefits generated from the interventions (15). The analysis is based on the concept of the theory of change and logic model. The foundations of SROI analysis is based on the traditional economic evaluations (16), and the value generated by the programme is relied upon the strong engagement of different levels of stakeholders who are directly or indirectly impacted by the programme (15, 17). A detailed SROI analysis process has been described elsewhere (15, 18). In brief, there are six stages of carrying out an SROI analysis. The first stage is establishing scope and identifying key stakeholders. In this stage, clear boundaries of what the analysis will cover, and who will be involved in the process and at what capacity. The second stage is related to mapping outcomes. In this stage, we will develop an impact map with the involvement of stakeholders, and the impact map should clearly visualize the relationship among inputs, outputs and outcomes. The third stage is evidencing outcomes and giving them a value. This stage involves exploring data to demonstrate whether the programme yields outcomes and then valuing them in a monetary term. In the fourth stage, the impact of the programme is established based on collected information and adjusted for other factors that could influence the overall results of the programme. The fifth stage calculates the SROI ratio by adding up all the benefits or savings and dividing it by the total investment in the programme, and performing sensitivity analysis. The final stage of the SROI analysis is related to reporting, using and embedding which involves sharing SROI findings with wider stakeholders, responding to their queries and embedding good practice and verification of the report.

Previous reviews on SROI included mental health interventions along with other public health interventions (18, 19), but to our knowledge, this scoping review is the first in its kind to exclusively focus on the SROI of mental health related interventions. The aim of this scoping review is to explore and map existing evidence on the social value of (public) mental health interventions that use the SROI method. The objectives of this review are to: (a) identify general characteristics of the SROI studies; (b) outline the reported SROI values; (c) assess methodological quality of SROI evidence; and (d) identify gaps in current literature related to the social value of mental health interventions. The findings can inform policy makers, budget holders and funding agencies about the value of investing in mental health and wellbeing to generate wider social, economic and environmental returns toward building healthier populations, communities and the planet.

Methods

This review is limited to studies which illustrate the SROI of public health interventions to improve mental health and wellbeing. The interventions could be targeted to people at any age group who were at risk of, or currently experiencing mental health problems.

Search process

PubMed/Medline, Google Scholar and relevant gray literature were searched for published records between January 2000 and March 2021. The search strategy combined the terms related to mental health and wellbeing, and Social Return on Investment. Potential relevant studies were first screened based on titles and abstracts, and the full texts were then retrieved for those likely to meet the inclusion criteria. The screened studies were independently assessed by two authors for inclusion in the review.

Study inclusion criteria

This scoping review was restricted to publication in English and included both scientific and gray literature of primary studies published between January 2000 and March 2021. Studies with any study design that reported SROI of interventions related to mental health and wellbeing, conducted in high and middle income countries were included.

Data extraction

Data was extracted from the eligible studies on population, intervention, outcomes and economic results in an independently developed data extraction form. Major economic findings of the SROI analysis and comprehensive data on total investment and realized benefits of the mental health interventions, or interventions targeted to improve mental health and wellbeing were extracted. Economic results were shown in monetary value of the return on every pound/dollar invested in the intervention.

Methodological quality assessment

A 12-point quality assessment framework developed by Krlev et al. (20) was used to assess the methodological quality of SROI studies. This quality assessment tool was used in previous reviews of the SROI studies (18, 19, 21). The quality assessment framework has proposed five quality dimensions spread over 12 different quality criteria. The quality assessment results of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

One point is given to each criterion, if it is present and zero points otherwise. A 70% benchmarking as proposed by Krlev and colleagues in 2013 was used as a “good score” to rate the study as “high quality” and “low quality” if the study scored < 70% (20).

Results

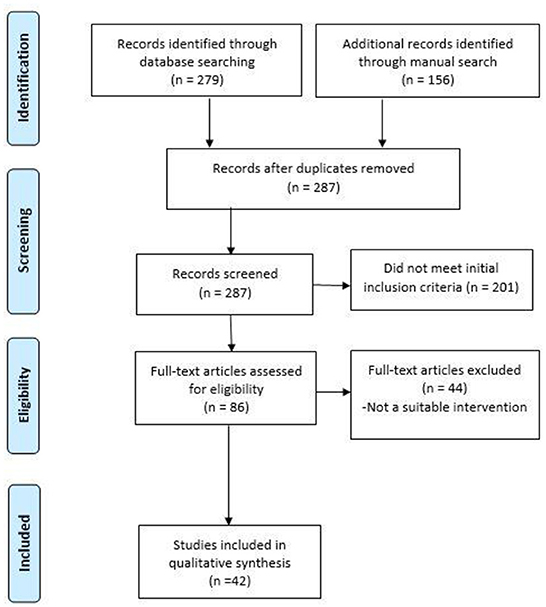

The preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline (64) was followed to report the findings of the scoping review.

The search hit a total of 435 records, 279 were from database searches and 156 from manual search (Figure 1). In total, 287 records were included for initial screening after duplicates were removed. Two hundred and one records were excluded from the initial title and abstract screening, leading to 86 records for full-text review and at this stage 44 records did not meet the inclusion criteria, which yielded 42 studies for inclusion in the final review.

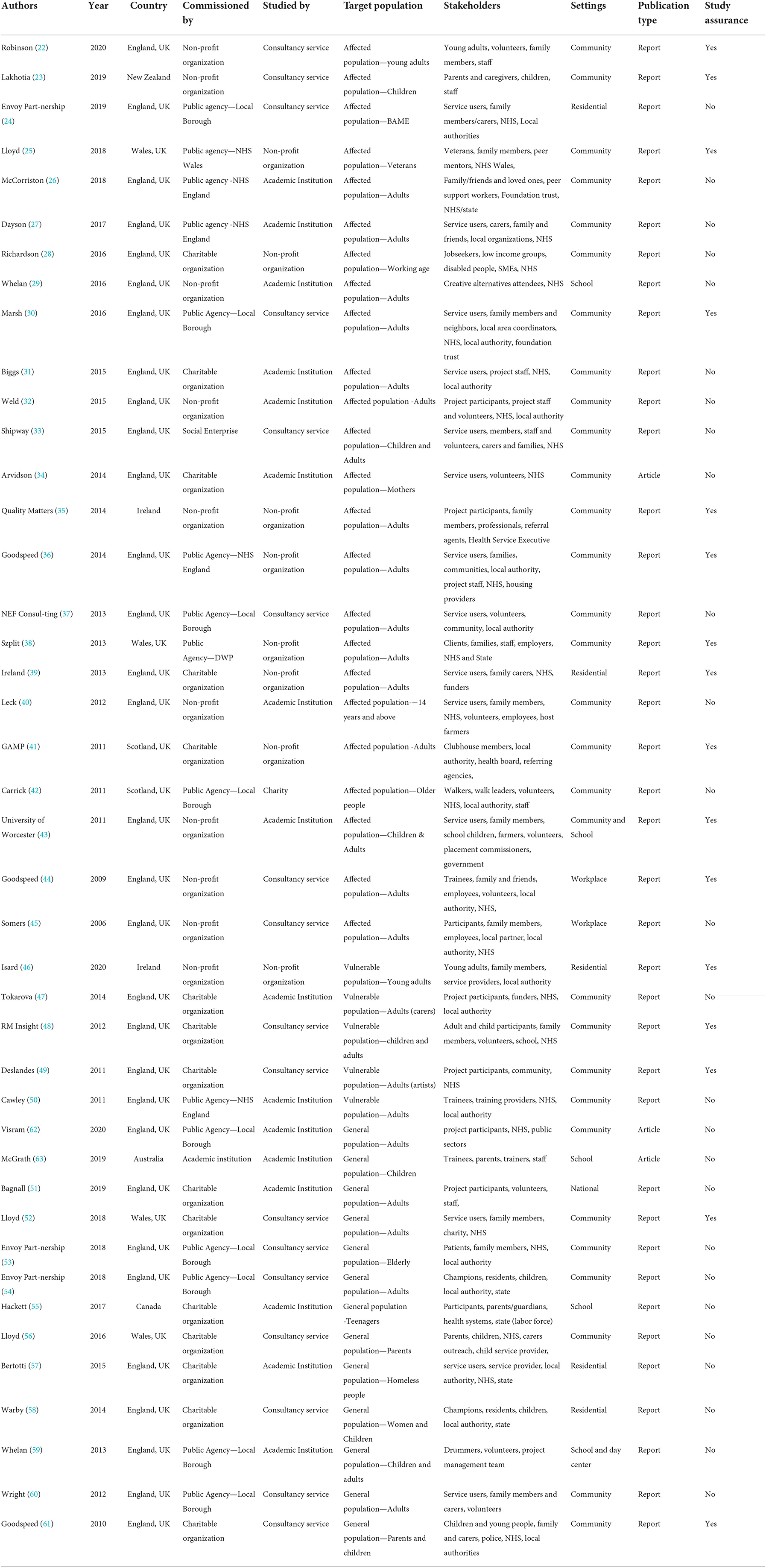

Table 2 summarizes the study characteristics; and Table 1 summarizes the SROI findings.

Study characteristics

Most of the included studies (93%) were non-peer reviewed publicly available reports, predominantly conducted in the UK (88%). The majority (60%) of the studies were funded by either charity or non-for-profit organizations, while 36% from NHS and local government agencies. We also found that the majority (74%) of the studies were conducted by either private consultancy firms or academia. Except two (44, 45), all other studies were conducted 2010 onwards.

More than two-third of the studies were conducted at the community level. In 57% of the studies, the direct beneficiaries were people experiencing some form of existing mental health problems. Majority of the studies in the review included direct beneficiaries from specific age groups (children, teenagers, youth, adults, working age, elderly). Some studies included specific population groups such as veterans, Black and Ethnic Minorities, mothers, carers, artists, parents, and homeless people. In addition to service users or direct beneficiaries, the studies included different stakeholders, such as volunteers, family members/friends, service providers, schools, local authorities, local organizations, NHS/health systems, other public services, referral agencies, charities, commissioners/funding agencies, national government. These SROI studies ranged in sample size from as low as 10 (22) to as high as 4,482 (28).

The studies evaluated SROI of different interventions related to mental health and wellbeing, including: arts for mental health (22, 29, 31, 33, 49, 63); workplace intervention (38, 44, 45, 47); farm or gardening activities (39, 40, 43); social prescribing (27, 52, 53); peer support (25, 26, 41); family support (23, 48, 61); residential interventions (46, 55, 57); awareness/training (32, 42, 50); community health champions (54, 58); ethnicity or culture—focused activities (24, 59); treatment/therapy (36, 62); digital inclusion (28); creating male space (35); nature conservation activities (51) and other community level activities (30, 34, 37, 56, 60).

Quality assessment: Out of 42 studies, 81% of the studies were considered as being high quality studies (Table 1). It was found that about 40% of the studies were submitted to and approved by the Social Value International for assurance (Table 2). Furthermore, we also found that 79% of the studies conducted sensitivity analyses to provide robustness of the SROI results (Table 1).

SROI results

In two-thirds of the studies, the SROI analyses were evaluative, with the remainder being forecast analyses. The evaluation time frame ranged from 1–6 years, with an exception of up to 30 years which evaluated the SROI of a community befriending programme to prevent post-natal depression (34).

Though there was wide variation in methodological quality and intervention types, most studies clearly illustrate the positive SROI of the interventions aimed at reducing mental health problems, and/or improving mental health and wellbeing. There is significant variation of the SROI ratio between studies—ranging from £0.79 (27) to £28 (26) for every pound invested. The SROI findings are further categorized on the basis of the mental health status/risk of the target population of the included studies. The SROI ratios of the interventions which were targeted to people who were experiencing mental health problems ranged from £0.79 to 28 for every £1 invested in the intervention. The interventions which were targeted to vulnerable/risky populations for mental health problems showed the SROI ratios that were ranged from £1.94 to 9.38 for every £1 invested. Similarly, the interventions to promote mental health and wellbeing of the general populations showed the SROI ratios that were ranged from £2.75 to 14.55 for every £1 invested in the intervention.

Twelve months was the lowest analysis time horizon where family action mental health project (48) yielded the lowest SROI of £1.94 for every pound invested, and the nature conservation activities of Wildlife Trust (51) yielded the highest SROI ratio of £14.55 for every pound invested. Thirty-year was the highest/longest SROI forecast analysis time horizon where an SROI of a community befriending programme to the families affected by post-natal depression (34) was estimated with a benefit of £6.50 for every pound invested. The detailed SROI findings of a review is presented in Table 1.

Discussion

This scoping review aims to explore the application of the SROI method to evaluate (public) mental health interventions. Compared to previous reviews on the SROI of public health interventions, which also included studies on the SROI of mental health interventions (18, 19), our scoping review incorporates studies with mental health intervention or studies that included mental health and/or wellbeing outcomes while evaluating social value of the intervention. The application of SROI to evaluate the wider social benefits of the mental health interventions could be used to inform policy decisions and investment prioritization in mental and wider public health.

Our review has found a good number of published reports that have shown a sizeable SROI of interventions addressing/preventing mental health issues or improving mental health and wellbeing. Overall, 42 studies with varying methodological quality were included in this review. The SROI ratios of the included studies ranged from £0.79 to 28 for every pound invested. Eighty-one percent of the studies were identified as high quality, using the Krlev's 12-item quality assessment framework (20), which allows studies for comparisons with relevant previous SROI reviews (18, 19). Our review findings are consistent with previous review findings related to SORI of mental health interventions.

The SROI method is being increasingly used to evaluate the wider impact and social value of various enterprises (65) as well as different programmes in health sectors (18) for the past two decades. The evaluation of public health interventions using a Social Value approach and SROI method have rapidly increased after 2010 in the health sector, especially by UK public and not-for-profit organizations. This might be due to the development of the guideline to SROI in 2009 (66) and the subsequent endorsement of the Public Service (Social Value) Act 2012 (67). However, there is little interest or motivation from evaluators and researchers to publish such evidence in peer-reviewed journals. This may partly be due to the introduction of SROI to evaluate the social value of the programmes delivered through not-for-profit or third sector organizations where publishing findings in academic journals may not be the priority; or partly due to potential “methodological fallacy” of the SROI approach perceived by the academic scholars.

The study interventions identified in this review were targeted either to reduce or prevent mental health problems, or to promote mental health and wellbeing, but interestingly none of the included SROI studies evaluated clinical treatment of mental health problems. We also found that studies vary widely in terms of types of interventions used, ranging from creative arts to nature conservation activities. The review showed considerable variation in the SROI findings according to mental health risk status of the target population in the included studies, but none of the studies showed negative SROI results. This implies that interventions that aimed to reduce/prevent mental health problems or promote mental health and wellbeing could have potential to yield positive Social Return on Investment.

This review also highlights the relevance of the SROI method to improve the measurement, valuation and reporting of the influence of mental health and wellbeing related intervention(s) to the wider society, economy and the planet, compared to traditional economic evaluations (18).

There is growing interest and drive from government and non-profit organizations to assess and maximize the value for money, and social value, of the public health interventions (62). Our review shows good SROI values of public health interventions for the prevention or reduction of mental health problems and promotion of mental health and wellbeing. These findings provide substantial evidence and a helpful insight related to a number of mental health interventions, to support policy makers and budget holders when taking decisions, evaluating programmes and prioritizing funding and investment in mental and wider public health and wellbeing.

Study limitations

Our review has several limitations. Only English language studies were included, while there might be studies conducted in other languages. We only included published SROI studies; there could be some studies which have not been published in the databases and sources searched. The existing Krlev's 12-item quality assessment framework has not been updated; some of the quality criteria have been subjective and difficult to judge, which may affect the reliability of the study results. We, however, used the quality criteria to the best of our ability to consistently apply throughout the included studies. There has been a high variability in the way the included studies have been conducted, which has limited the capacity to collate or draw summary/collective findings in the review. Due to large heterogeneity in sample size, intervention methods and benefit periods of the SROI ratios, it has not been possible to quantitatively synthesize the SROI results.

Gaps for further research

Our review has aimed to explore the existing evidence on SROI of mental health related interventions, but has not assessed other existing methods that might be also used to assess the value of mental health related interventions. Further research is needed to understand whether other existing methods could provide robust evidence in terms of identifying, measuring and reporting of the wider benefits/outcomes, impact and social value of interventions related to mental health and wellbeing. Current focus of the SROI data collection process is based on input/output of the intervention, but it is necessary to focus more on impact-oriented measures to capture their true value in the mid/long-term. There is also a need to publish more studies from SROI research work in the academic (peer reviewed) journals to attract wider academic audiences to explore and develop further this method and its application venues. More SROI research in the area of public health is needed to expand the evidence base and better inform investment prioritization, commissioning/funding decisions and programme improvement.

Author contributions

RK designed a scoping review, developed search strategies, assessed studies for inclusion, analysis, and drafting an initial manuscript. AS involved in the assessment of studies for inclusion. RK, AS, KA, RM, and MD subsequently revised and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rehm J, Shield KD. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2019) 21:10. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-0997-0

2. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:171–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2

3. Mental Health Foundation. Fundamental Facts about Mental Health. London: Mental Health Foundation (2016). Available online at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/fundamental-facts-about-mental-health-2016.pdf

4. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 (GBD 2017) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (2018).

6. Knapp M, Wong G. Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:3–14. doi: 10.1002/wps.20692

7. Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet (London, England). (2018) 392:1553–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

8. Department of Health UK. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2013: Public Mental Health Priorities: Investing in the Evidence. London: Department of Health (2013). Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/413196/CMO_web_doc.pdf

9. Deloitte MCS. Mental Health and Employers: The Case for Investment London: The Creative Studio at Deloitte. London: Deloitte MCS Limited (2017).

10. Baskin C, Zijlstra G, McGrath M, Lee C, Duncan FH, Oliver EJ, et al. Community-centred interventions for improving public mental health among adults from ethnic minority populations in the UK: a scoping review. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e041102. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041102

11. Jankovic D, Bojke L, Marshall D, Saramago Goncalves P, Churchill R, Melton H, et al. Systematic review and critique of methods for economic evaluation of digital mental health interventions. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2021) 19:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s40258-020-00607-3

12. Gaillard A, Sultan-Taïeb H, Sylvain C, Durand M-J. Economic evaluations of mental health interventions: A systematic review of interventions with work-focused components. Saf Sci. (2020) 132:104982. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104982

13. Le LK, Esturas AC, Mihalopoulos C, Chiotelis O, Bucholc J, Chatterton ML, et al. Cost-effectiveness evidence of mental health prevention and promotion interventions: a systematic review of economic evaluations. PLoS Med. (2021) 18:e1003606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003606

14. Feldman I, Gebreslassie M, Sampaio F, Nystrand C, Ssegonja R. Economic evaluations of public health interventions to improve mental health and prevent suicidal thoughts and behaviours: a systematic literature review. Adminis Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. (2021) 48:299–315. doi: 10.1007/s10488-020-01072-9

15. The SROI Network. A guide to Social Return on Investment (2012). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/The%20Guide%20to%20Social%20Return%20on%20Investment%202015.pdf

16. Muyambi K, Gurd B, Martinez L, Walker-Jeffreys M, Vallury K, Beach P, et al. Issues in using social return on investment as an evaluation tool. Eval J Aust. (2017) 17:32–9. doi: 10.1177/1035719X1701700305

17. Nicholls J. Social return on investment—Development and convergence. Eval Program Plann. (2017) 64:127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.11.011

18. Banke-Thomas AO, Madaj B, Charles A, van den Broek N. Social Return on Investment (SROI) methodology to account for value for money of public health interventions: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:582. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1935-7

19. Ashton K, Schröder-Bäck P, Clemens T, Dyakova M, Stielke A, Bellis MA. The social value of investing in public health across the life course: a systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:597. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08685-7

20. Krlev G, Münscher, R, Mülbert, K,. Social Return on Investment (SROI): State-ofthe-Art Perspectives: A Meta-Analysis of practice in Social Return on Investment (SROI) studies published 2000–2012. Germany: CSI (2013). Available online at: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/volltextserver/18758/

21. Gosselin V, Boccanfuso D, Laberge S. Social return on investment (SROI) method to evaluate physical activity and sport interventions: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. (2020) 17:26. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00931-w

22. Robinson S,. Artists for Mental Health Mindfulness Project: Social Return on Investment Evaluation. (2020). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/artist-for-mh-final.pdf

23. Lakhotia S,. Incredible Years Parenting Programme: Forecast Social Return on Investment Analysis. (2019). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Assured-SROI-Report-Incredible-years.pdf

24. Envoy Partnership,. Social Return on Investment of BME Health Forum's Multilingual Emotional Wellbeing Support Service in RBKC. (2019). Available online at: https://www.bmehf.org.uk/files/5015/7122/3993/BMEHF_multilingual_emotional_wellbeing_SROI_2018_FINAL_21.01.19.pdf

25. Lloyd E,. Social Return on Investment report of the Change Step service in partnership with Veterans' NHS Wales. (2018). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Change-Step-SROI-report.pdf

26. McCorriston E, Stevenson, N, SROI,. Evaluative Analysis: Recovery College East Peer Education Programme (PEP). England: Angelia Ruskin University (2018). Available online at: https://www.cpft.nhs.uk/Documents/Andrea%20G/SROI%20Report%20from%20Anglia%20Ruskin%20University%202018.pdf

27. Dayson C, Bennett, E,. Evaluation of the Rotherham Mental Health Social Prescribing Service 2015/16-2016/17. England: Sheffield Hallam University (2017). Available online at: https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2021/09/2017-evaluation-rotherham-health-social-prescribing-2015-2017.pdf

28. Richardson J, Lawlor, E, Bowen, N,. A Social Return on Investment Analysis for Tinder Foundation. England: Tinder Foundation (2016). Available online at: http://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/sroi250216formatted4_0.pd

29. Whelan G, Holden, H, Bockler, J,. A Social Return on Investment Evaluation of the St Helens Creative Alternatives Arts on Prescription Programme. England: Creative Alternatives (2016). Available online at: http://iccliverpool.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Creative-Alternatives-evaluation-report-2016.pdf

30. Marsh H. Social Value Coordination in Derby: A forecast Social Return on Investment Analysis for Derby City Council. England: Social Value UK (2016). Available online at: https://www.thinklocalactpersonal.org.uk_assets/Resources/BCC/Assured-SROI-Report-for-Local-Area-Coordination-in-Derby-March-2016.pdf

31. Biggs O, Jones M, Weld S, Kimberlee R, Aubrey P. The Art-Ease Project: Evaluation and Social Return on Investment Analysis of an Arts and Mental Health Project Delivered by Knowle West Health Park Company, Bristol. England: Knowledge West Health Park (2015).

32. Weld S, Kimberlee R, Biggs O, Blackburn K, Clifford Z, Jones M. For All Healthy Living Centre's Healthy Connections Project. Final evaluation report and Social Return on Investment (SROI) Analysis. England: University of the West of England (2015).

33. Shipway R,. The Social Value of Creative Arts in Supporting Mental Health. England: Hall Aitken (2015). Available online at: http://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2015-The-Social-Value-of-Creative-Arts-in-Supporting-Mental-Health.pdf

34. Arvidson M, Battye F, Salisbury D. The social return on investment in community befriending. Int J Public Sector Manage. (2014) 27:225–40. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-03-2013-0045

35. Quality Matters,. Mojo: A 12-Week Programme for Unemployed Men Experiencing Mental Health Distress—A Social Return on Investment Analysis. Dublin: Health Service Executive. (2014). Available online at: http://qualitymatters.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/MOJO_SROI_Report.pdf

36. Goodspeed T,. Value of Substance: A Social Return on Investment evaluation of Turning Point's Substance Misuse Services in Wakefield. England: Turning Point (2014). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Value%20of%20Substance%20FINAL.pdf

37. NEF Consulting. Equality outcomes: Social Return on Investment Analysis. England: NEF Consulting (2013). Available online at: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/nef_equality_outcomes_and_sroi_full_report_june13_final_0.pdf

38. Szplit K. Social Return on Investment (SROI) Forecast for the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) For Period April 2010 to March 2011. Cardiff: The SROI Network (2013). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IPS%20Forecast%20SROI%20Revised%20Feb%2013%20Assured.pdf

39. Ireland N,. Gardening in Mind Social Return on Investment Report England: The SROI Network. (2013). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gardening-in-Mind-SROI-Report-final-version-1.pdf

40. Leck C,. Social Return on Investment of the Houghton Project. England: University of Worcester (2012). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Houghton%20Project%20SROI%20assured.pdf

41. GAMH. Scotia Clubhouse Social Return on Investment Final Report. Glasgow: Glasgow Association for Mental Health (2011). Available online at: Scotia Clubhouse Social Return on Investment Final Report. Glasgow: Glasgow Association for Mental Health

42. Carrick K, Lindhof J. The Value of Walking: A Social Return on Investment Study of a Walking Project. England: Paths for All (2011).

43. University of Worcester. Forecast of Social Return on Investment of Nineveh Ridge activities. England: Care Farming West Midland (2011). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Final%20Nineveh%20Ridge%20SROI.pdf

44. Goodspeed T,. Forecast of Social Return on Investment of Workwise Activities. England: Workwise (2009). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SROI-Report-Workwise-Oct-09.pdf

45. Somers AB,. MillRace IT: A Social Return on Investment Analysis 2005-2006. England: NEF Consulting (2006). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/SROI-Report-Workwise-Oct-09.pdf

46. Isarad P, Gardner, C,. A Social Return on Investment Analysis on the Impact of DIAL House. (2020). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/A-Social-Return-on-Investment-Analysis-on-the-Impact-of-DIAL-House.pdf

47. Tokarova Z,. A Social Return on Investment Study of Wellbeing Works' Wellbeing Programme. England: Wellbeing Works (2014). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Wellbeing-Annual-Report-2014.pdf

48. RM Insight,. ESCAPE: a Social Return on Investment (SROI) Analysis of a Family Action Mental Health Project. England: Family Action (2012). Available online at: https://www.family-action.org.uk/content/uploads/2014/07/ESCAPE-SROI-Assured-Report.pdf

49. Deslandes C,. The Social Return on Investing in Community Arts in Mental Health at Inside Out. Scotland: Inside Out Community (2011). Available online at: http://www.insideoutcommunity.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Inside-Out-Final-SROI-Report-2011.pdf

50. Cawley J, Berzins K, SROI. Evaluation of Changing Minds for the South London and the Maudsley Mental Health Foundation Trust. England: University of East London (2011).

51. Bagnall A, Freeman C, Southby K, Brymer E. Social Return on Investment Analysis of the Health and Wellbeing Impacts of Wildlife Trust Programmes. Engand: Leeds Beckett University (2019).

52. Llyod E. The Social Impact of the Arfon Social Prescription Model Social Return on Investment (SROI) Evaluation and Forecast Report. Cardiff: Social Value Cymru (2018).

53. Envoy Partnership,. Social Return on Investment of Self-Care Social Prescribing. England: Envoy Partnership (2018). Available online at: https://www.kcsc.org.uk/sites/kcsc.org.uk/civi_files/files/civicrm/persist/contribute/files/Self%20Care/7641_SROI-Report_DIGITAL_AW.pdf

54. Envoy Partnership,. Community Champions Social Return on Investment Evaluation. England: Community Champions (2018). Available online at: https://www.jsna.info/sites/default/files/Community%20Champions%20SROI%20Report%202018.pdf

55. Hackett C, Jung Y, Mulvale G. Pine River Institute: Social Return on Investment for a Residental Treatment Programme. Canada: McMaster University (2017). Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/555e3952e4b025563eb1c538/t/595252a5d482e9a9a8d855c2/1498567338303/2017+SROI+small.pdf

56. Lloyd E,. Gwynedd Parent Carers Social Return on Investment (SROI) Evaluation Report. Wales: Social Value Cymru (2016). Available online at: https://www.carersoutreach.org.uk/downloads/190417-gwynedd-parent-carers-sroi-report-eng.pdf

57. Bertotti M, Farr, R, Akinbode, A,. Highway House Social Return on Investment Report. England: Institute for Health Human Development (2015). Available online at: https://www.pathway.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Highway-House-SROI-Report-July-2016.pdf

58. Warby AG. Social Return On Investment (SROI) analysis of Church Street Community Health Champions. England: Envoy Partnership (2014). Available online at: http://democracy.lbhf.gov.uk/documents/s85524/Community%20Champions%20-%20Appendix%202%20Social%20Retrun%20On%20Investment%20Executive%20Summary.pdf

59. Whelan G,. An evaluation of the social value of the Taiko Drumming for Health initiative in Wirral, Merseyside. England: Centre for Public Health (2014). Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279054305_An_evaluation_of_the_social_value_of_the_Taiko_Drumming_for_Health_initiative_in_Wirral_Merseyside

60. Wright T, Schifferes J, Consulting N. Growing Social Capital: A Social Return on Investment Analysis of the Impact of Voluntary and Community Sector Activities Funded by Grant Aid, December 2011. England: NEF Consulting (2012).

61. Goodspeed T,. The Economic Social Return of Action for Children's Family Intervention Project, Northamptonshire. England: Action for Children (2010). Available online at: https://socialvalueuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/assurance%20submission%20final%20TVB.pdf

62. Visram S, Walton N, Akhter N, Lewis S, Lister G. Assessing the value for money of an integrated health and wellbeing service in the UK. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 245:112661. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112661

63. McGrath R, Stevens K. Forecasting the social return on investment associated with children's participation in circus-arts training on their mental health and well-being. Int J Sociol Leisure. (2019) 2:163–93. doi: 10.1007/s41978-019-00036-0

64. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. (2009) 339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700

65. Corvo L, Pastore L, Mastrodascio M, Cepiku D. The social return on investment model: a systematic literature review. Meditari Account Res. (2022) 30:49–86. doi: 10.1108/MEDAR-05-2021-1307

66. Cabinet Office UG,. Guide to Social Return on Investement. (2009). Available online at: https://evaluationsupportscotland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/cabinet_office_a_guide_to_social_return_on_investment.pdf

67. UK Government,. Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. (2012). Available online at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted

Keywords: review, SROI, interventions, mental health and wellbeing, social value

Citation: Kadel R, Stielke A, Ashton K, Masters R and Dyakova M (2022) Social Return on Investment (SROI) of mental health related interventions—A scoping review. Front. Public Health 10:965148. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.965148

Received: 09 June 2022; Accepted: 28 November 2022;

Published: 09 December 2022.

Edited by:

Shen Liu, Anhui Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Kadel, Stielke, Ashton, Masters and Dyakova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rajendra Kadel, cmFqZW5kcmEua2FkZWxAd2FsZXMubmhzLnVr

Rajendra Kadel

Rajendra Kadel Anna Stielke

Anna Stielke Kathryn Ashton

Kathryn Ashton Rebecca Masters

Rebecca Masters Mariana Dyakova

Mariana Dyakova