95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 15 July 2022

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.961726

This article is part of the Research Topic Emerging Technologies for Employee Mental Health and Work Performance under Industry 4.0/5.0 View all 9 articles

The construction industry is labor-intensive, and employees' mental health has a significant impact on occupational health and job performance. In particular, expatriates in international projects under the normalization of the epidemic are under greater pressure than domestic project employees. This paper aims to explore the association of stressors and mental health in international constructions during COVID-19. Furthermore, test the mediation effect of psychological resilience and moderating effort of international experience in this relationship. A survey of 3,091 expatriates in international construction projects was conducted. A moderating mediation model was employed to test the effect of psychological resilience and international experience. Then, statistical analysis with a bootstrap sample was used to test the mediation effect of the model, and a simple slope was used to test the moderating effect. Moderated by experience, the slope of the effect of stressors on psychological resilience changed from −1.851 to −1.323. And the slope of the effect of psychological resilience on mental health outcomes reduced by about 0.1. This suggests that experience is one of the buffering factors for individual psychological resilience of expatriates to regulate stress. Theoretically, this study verifies the mediation effect of psychological resilience between COVID-19 related stressors and mental health outcomes and importance of an expatriate's experience in an international assignment. Practically, this study provides guidelines for international construction enterprises and managers to make an assistant plan for expatriates during this pandemic time and pay more attention to their psychological status. The research also suggests that the best choice for challenging assignments is choosing a more experienced employee.

Since January 2020, COVID-19 has threatened people's physical and mental health worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of December 31, 2021, COVID-19 has caused 285,685,390 infections and 5,430,101 deaths worldwide (1). Previous studies have shown increased levels of psychological distress and perceived mental illness in different populations during pandemics (2–6) and large-scale disasters (7, 8). Studies have shown that people have higher depression, anxiety, and stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic than usual (3, 9). Some studies have also found that everyone's reaction to COVID-19 is different (10). Some people can quickly adapt to this sudden situation, and some cannot. Previous studies have shown that individuals' characteristics and abilities may be responsible for different outcomes in coping with a crisis (11), such as individual psychological resilience. People with high levels of psychological resilience can better adapt to the influence of COVID-19 (12).

The countries' response to COVID-19 has entered a period of normalization. Employees in various industries are trying their best to resume production and work, and the international construction contracting industry is recovering fully (13). Different from other industries, international construction business takes place overseas, and international construction enterprises need to send many employees to the host country to work. Taking Chinese contractors as an example, a total of 119,000 people was dispatched to overseas project contracting work in 2021, according to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce (14). In addition to adapting to common cultural differences (15, 16), expatriates also need to adapt to the differences in epidemic prevention in the post-epidemic period. The Chinese government's defense policy against COVID-19 is “dynamic clearing,” which is different from “coexisting with the virus” in many countries in the world. The difference makes many Chinese expatriates uncomfortable with the local epidemic prevention and control after working overseas and even anxiety.

International construction is inherently a high-risk industry for international contractors (17–19). For example, a car bomb attack in Pakistan killed 9 Chinese construction workers in 2021. Managers of international projects should always pay attention to the threat of such emergencies to expatriates. At the same time, the cost of sending employees by international construction companies is very high (20, 21), especially in this particular period. If an expatriate cannot adapt well after arriving in the host country, has physical and mental problems, or even wants to return to the country in advance, the company needs to incur extra costs such as high airfare and isolation fees. Poor assignments or failures negatively impact project performance (22, 23). Therefore, the enterprise managers and international construction project managers urgently hope that the expatriates can adapt to the expatriate work safely, healthily, and quickly and complete the established tasks efficiently. Understanding expatriates' physical and mental state in the host country and understanding what factors affect their mental health performance can be very meaningful for international construction managers to help them develop a help plan. However, the existing researches have not paid much attention on the group of expatriates. Especially, there is a lack of understanding in the context of international construction.

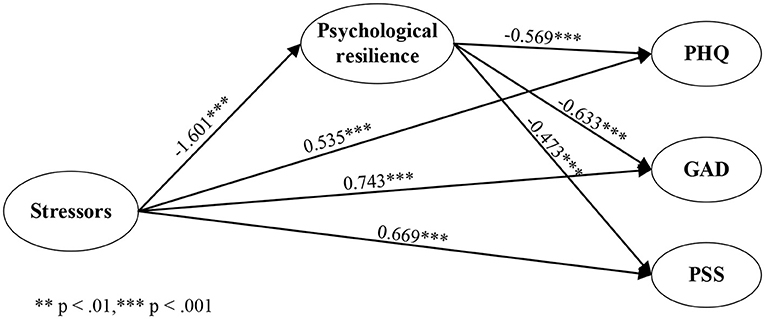

This study aimed to analyze the impact of COVID-19 related stressors on international construction expatriates' mental health levels (depression, anxiety, perceived stress). By constructing a model (Figure 1) mediated by individual psychological resilience and moderated by expatriate experience, this study uses questionnaires to investigate and analyze expatriates of international contractors. Details of the development of the hypotheses are presented in the following section.

There have been many pieces of research on psychological resilience. Most of them focus on the antecedents and consequences of psychological resilience or take psychological resilience as an intermediary or regulatory variable. The psychological resilience of this paper refers to the individual in the workplace situation. There is no uniform definition of psychological resilience. However, they all believe that the experience of adversity is the first defining element (24). This paper defines psychological resilience from the perspective of ability (25), explicitly referring to the ability of expatriates to deal with stressors and adjust themselves to normal status. Fisher, Ragsdale (26) point stressors at work may be short-term and sudden high-risk events (e.g., public safety events) or long-term continuous circumstances (e.g., work stress). For expatriates from international construction companies, they have to face the public workplace stressors mentioned above. At the same time, due to the high risk of the international construction industry and the working environment of uprooting, especially the impact of COVID-19, stressors include both from the pandemic (27), family (28), and workplace (29).

In workplace, stressors are regarded as an adversity, and individual's protective resources are first invoked in response to stress (30). Protective resources are directly related to psychological resilience (31). If there are too many stress events and the resources that individuals can use are insufficient, the psychological elasticity will be worse. Taking mental health as an outcome of psychological resilience, scholars found that employees' resilience is positively related to their mental health (32), and negatively affects the expression of burnout and emotional exhaustion (33–35). McLarnon and Rothstein (36) pointed out that half of the indicators in the Workplace Resilience Scale were negatively correlated with depression. Moreover, Ferris, Sinclair (37) emphasized that the lack of individual psychological resilience caused physical and psychological stress, such as low emotional, easy to fatigue, and poor attention. Previous studies have started investigating the individual resilience as a mediation factor. The challenge-hindrance stressors model posits that workplace stressors can be grouped into two categories. Hindrance stressors will interfere with performance or goals, while challenge stressors contribute to performance opportunities (38). Based on the model, Crane and Searle (39) found resilience played a full mediation effect between the negative relationship of challenge stressors and strain and the positive relationship of hindrance stressors and strain. Also, Kinman and Grant (32) found resilience played a full mediation effect between the negative relationship of emotional intelligence and mental distress.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, some studies focus on the relationship between resilience and mental health. However, researchers have regarded resilience as one of the components of psychological capital, which has been found to be related with factors in workplace and employee's mental health (25). Lawal et al. (40) used the standard scale to test the mental health of ordinary people in COVID-19. Their research pointed out that the individuals' psychological distress, depression, and anxiety were significantly higher than those of normal ones due to the influence of COVID-19. In the early study, researchers paid more attention to doctors, nurses, and other people who had direct contact with COVID-19 (41). Rossi et al. (42) analyzed the mental health status of Italian residents during the closed period. They found that stressors in COVID-19 significantly impacted depression, anxiety, and stress perception. Barzilay, Moore (43) found that people with higher psychological resilience were not prone to depression and anxiety. As the pandemic continues, we believe this phenomenon may also be present among international construction expatriates. Therefore, the hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1: Psychological resilience mediates the influence of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' mental health.

Hypothesis 1a: Psychological resilience mediates the influence of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' level of depression.

Hypothesis 1b: Psychological resilience mediates the influence of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' level of anxiety.

Hypothesis 1c: Psychological resilience mediates the influence of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' perceived stress levels.

Many studies have confirmed that psychological resilience among individuals differs, which depends on many factors. Personal resources are considered one of the most critical factors (44). Employees' professional knowledge about the work (45) or technology related to work (46) is positively related to psychological resilience. Although there is no direct research on the relationship between work experience and psychological resilience, like workability, work experience is also an essential resource in the individual workplace. Experienced workers know better how to deal with difficulties and perform better under stressors (47). The positive state and emotion could improve employees' psychological resilience, while the negative emotions had an opposite effect in case of an organizational crisis (48). Therefore, we believe that it is reasonable that expatriate experience, as a unique resource, is related to individual psychological resilience. Therefore, the hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2: International assignment experience moderates the relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and psychological resilience. When expatriates' international assignment experience is more prosperous, the negative effect of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' psychological resilience is weaker.

Resilience is a protective mechanism when people are facing of adversity which is usually associated with lower mental distress (49). However, no thorough research points out that work experience is directly related to individual mental health statuses such as depression and anxiety. However, Wiseman, Curtis (50) found that individuals with different life experiences have different manifestations of depression and anxiety. Stress levels were higher for the general public than those working directly (front line nurses) with COVID patients, possibly related to experience and confidence (51).

Moreover, Rossi et al. (12) and Nwachukwu et al. (52) found that in the elderly group, psychological resilience has a more significant impact on individual mental health states such as depression and anxiety. It is found that age is the regulatory factor between psychological resilience and mental health. Furthermore, generally, older people have more work experience. Therefore, the hypothesizes are proposed.

Hypothesis 3: International assignment experience moderates the indirect effect of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' mental health via psychological resilience. When expatriates' international assignment experience is less prosperous, the negative effect of expatriates' psychological resilience on mental health is more robust.

Hypothesis 3a: International assignment experience moderates the path of psychological resilience on expatriates' level of depression.

Hypothesis 3b: International assignment experience moderates the path of psychological resilience on expatriates' level of anxiety.

Hypothesis 3c: International assignment experience moderates the path of psychological resilience on expatriates' perceived stress level.

We tested the hypothesis model with a sample of expatriates in international construction enterprises. In the study, expatriates were defined as “Citizens of the home country or third country whom international construction companies appoint to work in the host country, among which the citizens of the home country who work in the host country are mainly.” Therefore, we cooperated with SINOPEC Engineering (Group) Co. Ltd. (SEG), which was listed in the Top 250 contractors of ENR in 2020. We used the online questionnaire platform of Wenjuanxing to collect data. The HR department sent the questionnaire to all the expatriates by the inner system of SEG from May 5 to May 25 in 2020. In the survey, 3,091 valid questionnaires were received, including managers, workers, subcontractors, and others. The characteristics, including gender, age, position, and international assignments experience, were collected in the demographic information (Table 1). The expatriates of enterprises participating in the research are informed in advance that the results are only used for academic research and participate voluntarily.

Stressors (SE) during COVID-19 were assessed using a checklist of stress events developed by this research. The list of stress events was obtained through a literature review and employee interviews. Therefore, the checklist explores thirteen different stressors in Table 2. In the questionnaire, each item has a yes/no response as a binary variable. 0 = “feel no stress due to this during COVID-19” and 1 = “feel stress due to this during COVID-19.” The Cronbach's alpha was 0.888 in this research.

Psychological resilience (PR) was measured by 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10). The CD-RISC is used widely to assess resilience (55). The original version of the CD-RISC-10 was created by Campbell-Sills and Stein (56) includes ten items. The response scale has a 5-point range: 1 (not true at all), 2 (rarely true), 3 (sometimes true), 4 (often true), and 5 (true nearly all of the time). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the overall CD-RISC-10 was 0.937.

Depression was measured by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in a Chinese version (57). PHQ-9 contains nine items measured by a 4-point Likert scale. The total score of PHQ-9 was analyzed as a continuous variable. PHQ-9 is used as a tool for screening depression in many countries around the world. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.938 in this research.

Anxiety was measured by the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) in a Chinese version (58). GAD-7 contains seven items measured by a 4-point Likert scale. The total score of GAD-7 was analyzed as a continuous variable. Many countries use GAD-7 for anxiety screening. In this research, Cronbach's alpha was 0.936.

Perceived stress was assessed by the Chinese version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) (59). PSS includes ten items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The Cronbach's alpha was 0.922 in this research.

International assignments experience was divided into five groups, and respondents could choose the answer according to their situation. This variable was analyzed as a ordinal variable with five scores (1 = 0–1 years, 2 = 1–3 years, 3 = 3–5 years, 4 = 5–10 years, 5 = 10 years and over.) The scales and question items are listed in Appendix A.

After standardized the data of PHQ and GAD scales into 5-point, the analysis process followed the steps below. Firstly, we used Harman's single-factor test to check the common method biases of all of the items in the four scales. Moreover, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted using AMOS 26.0. Secondly, we used the SPSS 26.0 to conduct descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. Thirdly, verify the mediating effect between stressors and mental distress with psychological resilience as the mediating variable. The significance of mediation effect was judged by checking whether the confidence intervals of 95% bootstrap repeated 5,000 times included zero. Finally, conditional indirect effects of COVID-19-related stressors on mental distress, which was mediated by psychological resilience and moderated by international assignment experience was tested. This moderated mediation model is based on Hayes's Model 58. Moreover, we conducted the simple slope test to determine how the international assignment experience moderates the relationship between COVID-19 related stressors and psychological resilience.

We randomly divided the sample into two parts. Half of the samples were used for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) without rotation. The results of Harman's single-factor test extracted ten factors with eigenvalues above one. Before the rotation the variance explained by the leading common factor was 37.34%, which was less than the 40% required by the critical criteria (60). Therefore, this study does not consider the influence of common method bias.

The other half of samples was conducted a confirmatory factor analysis in Amos 26.0. The expatriates' international assignments experience and stressors questionnaire answers objective facts and does not test an implicit variable. Therefore, the scale's content validity and discriminant validity are not tested. As shown in Table 3, all factor loadings were above 0.6 and significant, indicating that the measured item validity was acceptable. The composite reliability (CR) for each construct's was >0.7, indicating that CR was acceptable. Moreover, each construct's average variance extracted (AVE) is more significant than 0.5, indicating that convergence validity was acceptable. In addition, the square root of AVE of each construct is larger than the correlation coefficient between any two constructs. This shows that the discrimination of each structure is significant. Therefore, the validity of each measure is acceptable. And the RMSEA value of the model is 0.062 (< 0.01), CFI value is 0.937 (>0.09), and NFI value is 0.933 (>0.09). Thus, the model fit is acceptable.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the main study variables were presented in Table 4. Correlation analyses showed that expatriates' psychological resilience is significantly associated with stressors (r = −0.374, p < 0.01), PHQ (r = −0.665, p < 0.01), GAD (r = −0.619, p < 0.01), and PSS (r = −0.510, p < 0.01). This satisfied the prerequisites of mediation analysis.

For the control variables, age correlated significantly with IAE (r = 0.423, p < 0.01), PR (r = 0.120, p < 0.01), PHQ (r = −0.155, p < 0.01), GAD (r = −0.118, p < 0.01), and PSS (r = −0.055, p < 0.01); gender correlated significantly with IAE (r = −0.086, p < 0.01) and PR (r = 0.044, p < 0.05). In the tests of relevant hypotheses, age and gender were controlled (61).

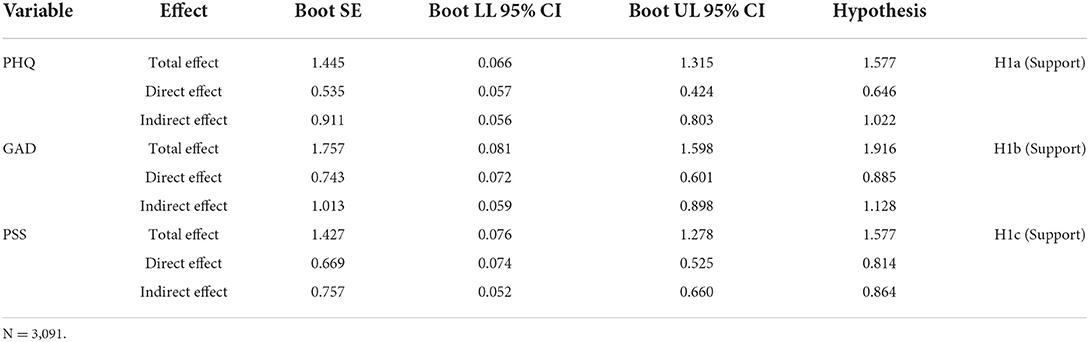

According to the correlation analysis results, they meet the conditions for establishing an intermediary relationship between the three factors. The mediating model (Hypothesis 1) was tested by Model 4 of PROCESS. The results in Figure 2 show that stressors significantly negatively predicted psychological resilience (t = −1.601, p < 0.001). When stressors and psychological resilience were considered in the regression equation, psychological resilience was significantly negative with PHQ (t = −0.569, p < 0.001). The indirect effect was tested by 5,000 resampling bootstraps. Results in Table 5 showed the mediation effect of psychological resilience between COVID-19 stressors and PHQ is significant (Effect = 0.911, SE = 0.056, 95% boot CI = [0.803, 1.022]). The mediation effect's 95% bootstrap confidence interval (CI) did not contain zero, and the indirect effect accounted for 63.26% of the total effect. Therefore, psychological resilience mediated the relationship between stressors and PHQ. Thus, Hypothesis 1a was supported.

Figure 2. Path coefficients of COVID-19 related stressors, psychological resilience, and mental health.

Table 5. Psychological resilience as a mediator in the relationship between COVID-19 related stressors and mental health.

Also, psychological resilience significantly negatively predicted GAD (t = −0.633, p < 0.001). Results in Table 5 showed the mediation effect of psychological resilience between COVID-19 stressors and GAD is significant (Effect = 1.013, SE = 0.059, 95% boot CI = [0.898, 1.128]). The mediation effect's 95% bootstrap confidence interval (CI) did not contain zero, and the indirect effect accounted for 57.66% of the total effect. Therefore, psychological resilience mediated the relationship between stressors and GAD. Thus, Hypothesis 1b was supported.

Finally, psychological resilience significantly negatively predicted PSS (t = −0.473, p < 0.001). Results in Table 5 showed the mediation effect of psychological resilience between COVID-19 stressors and PSS is significant (Effect = 0.757, SE = 0.052, 95% boot CI = [0.660, 0.864]). The mediation effect's 95% bootstrap confidence interval (CI) did not contain zero, and the indirect effect accounted for 53.05% of the total effect. Therefore, psychological resilience mediated the relationship between stressors and PSS. Thus, Hypothesis 1c was supported. The effect value of each path is shown in Figure 2.

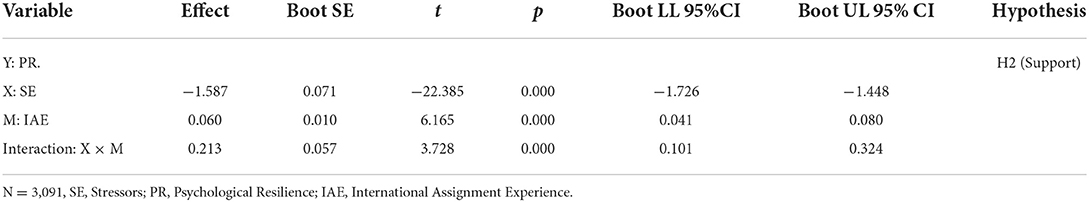

Moderating effects are hypothesized at two stages of the mediation relationship. The first stage is the effect of stressors on psychological resilience. International assignment experience moderates the relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and psychological resilience. When expatriates' international assignment experience is more prosperous, the negative effect of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' psychological resilience is weaker. The second stage is the effect of psychological resilience on mental health outcomes. International assignment experience moderates the indirect effect of stressors during COVID-19 on expatriates' mental health via psychological resilience. When expatriates' international assignment experience is less prosperous, the negative effect of expatriates' psychological resilience on mental health is more robust. PROCESS model 58 was conducted to test Hypotheses 2, 3a, 3b, and 3c, respectively.

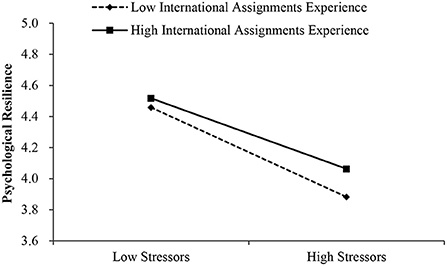

According to Table 6, it was revealed that effect of stress events during COVID-19 on psychological resilience was significant (Effect = −1.587, SE = 0.071, 95% bootstrap CI = [−1.726, −1.448]), and more importantly, the effect was significantly moderated by expatriates' international assignments experience (Effect = 0.213, SE = 0.057, 95% bootstrap CI = [0.101, 0.324]). For clarity, we plotted stressors during COVID-19 on psychological resilience (Figure 3), separately for low and high stress (Mean-SD and Mean + SD, respectively). Simple slope tests indicate that for expatriates who have high international assignments experience, psychological resilience level is significantly descended as the increase of stressors during COVID-19 (Effect = −1.323, SE = 0.100, p < 0.001); for expatriates have low international assignments experience, psychological resilience level is also significantly descended as the increase of stressors during COVID-19 (Effect = −1.851, SE = 0.100, p < 0.001). Moderated by experience, the slope of the effect of stressors on psychological resilience changed from −1.851 to −1.323, reduced by about 0.5. It can be revealed that experience is a buffering factor when dealing with stressors during COVID-19, the psychological resilience of expatriates decreases slowly compared with those who have less experience (Figure 3). Thus, H2 was supported.

Table 6. International assignment experience modifies the relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and mental health.

Figure 3. Simple slopes of international assignments experience moderate the relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and psychological resilience.

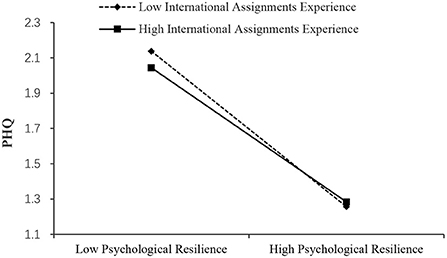

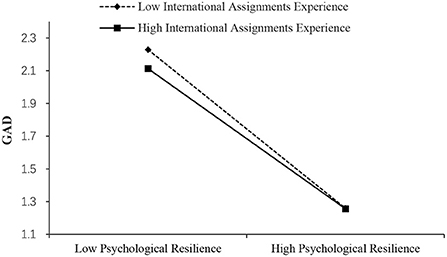

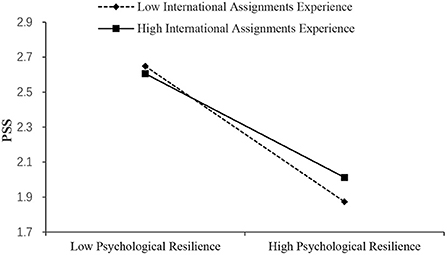

As shown in Table 7, the effect of psychological resilience on PHQ was significant when international assignments experience was high (Effect = −0.517, SE = 0.019, 95% boot CI = [−0.555, −0.479]) and low (Effect = −0.599, SE = 0.016, 95% boot CI = [−0.631, −0.567]). And, the of psychological resilience on GAD was significant when international assignments experience was high (Effect = −0.583, SE = 0.025, 95% boot CI = [−0.631, −0.535]) and low (Effect = −0.659, SE = 0.021, 95% boot CI = [−0.700, −0.618]). Also, the effect of psychological resilience on PSS was significant when international assignments experience was high (Effect = −0.403, SE = 0.025, 95% boot CI = [−0.452, −0.354]) and low (Effect = −0.527, SE = 0.021, 95% boot CI = [−0.569, −0.486]). Thus, it can be concluded from the simple slopes that expatriates' international assignments experience attenuated the effect of psychological resilience on mental health (Figures 4–6). Moderated by experience, the slope of the effect of psychological resilience on mental health outcomes reduced by about 0.1. This indicated that experience can be regarded as a buffering factor for individual psychological resilience of expatriates to regulate stress. Thus, H3a, H3b, and H3c were supported. While, the results indicate the buffering effect of experience differs in the two stages. It is more significant between stressors and psychological resilience.

Figure 4. Simple slopes of international assignments experience moderate the effect of psychological resilience on PHQ.

Figure 5. Simple slopes of international assignments experience moderate the effect of psychological resilience on GAD.

Figure 6. Simple slopes of international assignments experience moderate the effect of psychological resilience on PSS.

A moderated mediation model was established to assess the indirect relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and mental distress via psychological resilience and whether expatriates' international assignments experience moderated the first and second stages of this indirect association. The results explain how and when stressors during COVID-19 impact expatriates' mental health.

Consistent with our expectation (Hypothesis 1), stressors during COVID-19 positively predicted PHQ, GAD, and PSS scores. Psychological resilience was a mediation factor in this relation, extending previous theory and empirical research. Previous researches showed that the COVID-19 pandemic had significantly increased the depression, anxiety, and stress perceived level (12, 42, 62). Our research findings also confirmed the positive association between stressors and mental distress. Moreover, other than directly affecting depression, anxiety, and stress perceived level, stressors during COVID-19 indirectly affect these three variables. This mediation model suggests a possible reason why the more stressors, the more prone to depression, anxiety, and stress may be beyond their resilience to deal with adversity.

Specifically, it advances our understanding of psychological resilience by applying the negative outcome of COVID-19-related stressors into depression, anxiety, and perceived stress. Although the antecedents and consequences of psychological resilience have been verified with various studies (45, 48, 63), there is no relevant evidence in the expatriates of multinational companies. Consistent with the results of Rossi's et al. (12) research, psychological resilience plays a mediation role between stressors during COVID-19 and mental health. After expatriates encounter COVID-19 related stressors, individual protective factors will play a role in helping expatriates recover from adversity. However, when the resilience is poor, the psychological state of expatriates will change and threaten their mental health. The mental health problems of expatriates in multinational enterprises are more prominent than their domestic employees (64), especially in the face of the outbreak and persistence of COVID-19. In our survey, 70% of the respondents were delayed in their return.

In addition, the two stages of the mediation process will be discussed separately. Consistent with previous reports, we find that COVID-19-related stressors decrease psychological resilience scores (65). According to the standard definition of psychological resilience, individuals experiencing stressors can inspire one's ability to cope with adversities (66). According to resource conservation theory (67, 68), psychological resilience is a positive conservation resource for individuals (69). The more the external stressors, the more resources the individual needs to recover from this state with a longer recovery process. The ability to recover is also reduced (68). Besides, psychological resilience scores are correlated with depression, anxiety, and stress perceived level. It indicates that higher psychological resilience can buffer the effect of COVID-19 related stressors on such depression, anxiety, and stress perceived (70). These researches are consistent with our results that people with a high level of psychological resilience have a more vital ability to recover from adversity. The probability of psychological problems will decrease, and their mental state will be healthier.

Compared with Rossi et al.'s (12) research, in the expatriates' group, the path influence coefficient of stressors during COVID-19 on individual psychological resilience is significantly higher than that of the general group. The path coefficient of COVID-19-related stressors on depression, anxiety, and stress perception is also significantly higher than ordinary people.

The moderating effect on the two stages in our mediation model is discussed separately.

As predicted in our hypothesis 2, expatriates' international assignments experience moderates the association between stressors during COVID-19 and psychological resilience. Specifically, the negative predicting role of stressors during COVID-19 on psychological resilience is significant slowdown among those with richer international assignments experience; in contrast, for those with less international assignments experience, the relation between stressors during COVID-19 and psychological resilience is stronger. This is consistent with the point of view of resource conservation theory (67). Expatriate experience is an essential resource for individual international construction expatriates. When employees encounter stressors, the more experienced one can fully mobilize their resources (71). It is easier for them to find ways and attitudes to deal with the incident from their experience, thereby improving their ability to return to normal. Nevertheless, international construction is a highly uncertain environment (72); especially during the outbreak and duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, expatriates' feelings about home are amplified (73). This is also related to the feelings toward home in Chinese traditional culture (74). However, the continuation of the epidemic has made the road home extremely difficult. At this time, international assignments experience can fully adjust the ability of expatriates to regulate stressors and quickly recover to a well-adjusted state. This suggests that experience is one of the buffering factors for individual psychological resilience of expatriates to regulate stress.

As predicted in our hypothesis 3, expatriates' international assignments experience moderates the second mediation path from psychological resilience to PHQ, GAD, and PSS. The moderating role of expatriates' international assignments experience can be explained by the combined action of expatriates' international assignments experience and psychological resilience on PHQ, GAD, and PSS (60). Rossi et al. (12) find that age plays a moderating role between resilience, depression, and anxiety. Generally speaking, older people have more work experience. Expatriates with high psychological resilience are less likely to have depression and other emotions (75) because they have a more vital ability to adjust themselves to external events. This phenomenon is evident among experienced expatriates. These people can find similar experiences from their existing experiences and draw inferences from one instance (76). They know better how to improve their ability to adapt to crises to avoid unhealthy psychological states such as depression and anxiety. At the same time, the existing experience allows them to know the possible results after the occurrence of stressors to reduce their fear of the unknown future, which is very important for emotional stability and mental health.

When comparing the moderating effect in the two stages, it is more significant between stressors and psychological resilience. This result indicate that psychological resilience can be affect significantly by individual resources. Expatriates can take more measures to deal with adversities and adapt to health status. However, once the level of psychological resilience decreases and causes mental health problems, the moderating effect of experience is less significant.

Our research has practical value for international construction enterprises and managers of international construction projects, including three aspects. First, managers accurately understand the psychological health of expatriates under the normalization of COVID-19 and formulate intervention and help plans in time. Secondly, managers are more transparent that priority should be given to those with rich expatriate experience when selecting expatriates. In emergencies, experienced people can do an excellent job in self-psychological adjustment. Finally, managers should pay more attention to the psychological resilience of expatriates, which negatively affects the psychologically unhealthy states of expatriates, such as depression, anxiety, and stress. The individual's psychological resilience can be improved. Managers can prioritize those with high psychological resilience to work abroad and formulate improvement plans to help expatriates.

There are several limitations to this study. First, due to the limitations of cross-sectional data, the results of this study have limitations. The follow-up research can increase the data collection of profile and psychological experiment. Second, this study makes a subjective evaluation of self-perception. Although this method is widely used in a large number of studies, there may be a deviation between participants' self-perception and the actual state. In the future, physical measurement tools can be used to assist in the evaluation of psychological and emotional states. Finally, all the participants are Chinese. The cultural background of different countries may lead to differences in their psychological resilience. At the same time, the social environment of the host country may also have effect on physical and mental health of expatriates. Therefore, our findings may not be applicable to expatriates from other cultural backgrounds. In future research, we will cooperate with more international contractors to collect data to verify the research results and take specific measures to improve the psychological resilience of expatriates.

Based on our analysis and discussion, the current study suggests that expatriates' psychological resilience mediates the relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and mental health. International assignments experience moderates the first and second half of the mediation process. Furthermore, stressors affect mental health through expatriates' psychological resilience.

The research provided a theoretical and empirical basis for understanding the relationship between stressors during COVID-19 and expatriates' mental health. According to the moderated mediating model, stressors negatively predicted psychological resilience, and psychological resilience negatively predicted depression, anxiety, and perceived stress. Moreover, when expatriates have high international assignments experience, their psychological resilience level had a significant descending trend as the increased COVID-19 related stressors. On the other hand, when expatriates have low international assignments experience, the effect of psychological resilience on expatriates' depression, anxiety, and perceived stress level is significantly weakened with the increased level of psychological resilience. The results also indicate that the mental health of expatriates in international projects not only depends on individual resources, but also requires resources at the project team and organization level. In addition, we can effectively intervene in the impact of stressors on mental health by improving expatriates' psychological resilience during COVID-19. Meanwhile, managers can prioritize international expatriates with rich experience working on overseas projects in the post epidemic era.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

LG: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, formal analysis, and validation. XD: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, and resources. WY: software and visualization. JF: investigation and data collection. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 72171048 and 72101053), the Scientific Research Foundation of Graduate School of Southeast University (Grant No. YBPY2130), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. KYCX21_0167).

JF was employed by SINOPEC Engineering (Group) Co. Ltd. (SEG).

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. WHO. Available online at: https://Covid19.Who.Int/ (2021) (accessed December 31, 2021).

2. Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Zhou AB, Sang HB, Liu SY, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102092. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092

3. Li JF, Yang ZY, Qiu H, Wang Y, Jian LY, Ji JJ, et al. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry. (2020) 19:249–50. doi: 10.1002/wps.20758

4. Madani A, Boutebal SE, Bryant CR. The psychological impact of confinement linked to the Coronavirus epidemic COVID-19 in Algeria. Int J Env Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3604. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103604

5. Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102683. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076

6. Qiu JY, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu YF. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry. (2020) 33:e100213. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

7. Moosavi S, Nwaka B, Akinjise I, Corbett SE, Chue P, Greenshaw AJ, et al. Mental health effects in primary care patients 18 months after a major wildfire in Fort Mcmurray: risk increased by social demographic issues, clinical antecedents, and degree of fire exposure. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:683. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00683

8. McKinzie AE. In their own words: disaster and emotion, suffering, and mental health. Int J Qual Stud Health Wellbeing. (2018) 13:1440108. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2018.1440108

9. Tull MT, Edmonds KA, Scamaldo KM, Richmond JR, Rose JP, Gratz KL. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiat Res. (2020) 289:113098. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113098

10. Zhang J, Lu HP, Zeng HP, Zhang SN, Du QF, Jiang TY, et al. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:49–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.031

11. Wang CY, Pan RY, Wan XY, Tan YL, Xu LK, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Env Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729

12. Rossi R, Jannini TB, Socci V, Pacitti F, Lorenzo GD. Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:635832. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635832

13. Emell Adolphus PRaJK. Enr 2021 the Top 250 Internatiaonl Contractors (2021). Available online at: www.enr.com.

15. Zhong YF, Zhu JC, Zhang MM. Expatriate management of emerging market multinational enterprises: a multiple case study approach. J. Risk Financ. Manag. (2021) 14:252. doi: 10.3390/jrfm14060252

16. Edwards KJ, Dodd CH, Rosenbusch KH, Cerny LJ. Measuring expatriate cross-cultural stress: a reanalysis of the CernySmith assessment. J Psychol Theol. (2016) 44:268–80. doi: 10.1177/009164711604400402

17. Dikmen I, Budayan C, Birgonul MT, Hayat E. Effects of risk attitude and controllability assumption on risk ratings: observational study on international construction project risk assessment. J Manag Eng. (2018) 34:04018037. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000643

18. Deng XP, Pheng LS. Understanding the critical variables affecting the level of political risks in international construction projects. KSCE J Civ Eng. (2013) 17:895–907. doi: 10.1007/s12205-013-0354-5

19. Deng XP, Low SP, Zhao XB, Chang TY. Identifying micro variables contributing to political risks in international construction projects. Eng Constr Archit Manag. (2018) 25:317–34. doi: 10.1108/ECAM-02-2017-0042

20. Nowak C, Linder C. Do you know how much your expatriate costs? An activity-based cost analysis of expatriation. J Glob Mobility. (2016) 4:88–107. doi: 10.1108/JGM-10-2015-0043

21. Swaak RA. Expatriate failures: too many, too much cost, too little planning. Compens Benefits Rev. (1995) 27:47–55. doi: 10.1177/088636879502700609

22. Semi A. Expatriate Adjustment and Work Performance During COVID-19: The Role of Organisational Support in Hostile Environments. UNIVERSITY OF VAASA (2021).

23. Konanahalli A, Oyedele LO. Emotional intelligence and British expatriates' cross-cultural adjustment in international construction projects. Constr. Manag. Econ. (2016) 34:751–68. doi: 10.1080/01446193.2016.1213399

24. Masten AS. Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. (2001) 56:227–38. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227

25. Luthans F, Avolio BJ, Avey JB, Norman SM. Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers Psychol. (2007) 60:541–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

26. Fisher DM, Ragsdale JM, Fisher ECS. The importance of definitional and temporal issues in the study of resilience. Appl Psychol. (2019) 68:583–620. doi: 10.1111/apps.12162

27. Tripathi CM, Singh T. Sailing through the COVID-19 pandemic: managing expatriates' psychological well-being and performance during natural crises. J Glob Mobility. (2021) 10:192–208. doi: 10.1108/JGM-03-2021-0034

28. Shah D, de Oliveira RT, Barker M, Moeller M, Nguyen T. Expatriate family adjustment: how organisational support on international assignments matters. J Int Manag. (2021) 28:100880. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2021.100880

29. Shaaban MSA. The Relationship between Expatriate Job Deprivation and Thriving at Workplace: Examining the Antecedents, Moderator, and Outcomes. University of Essex (2022).

30. Harms PD, Vanhove A, Luthans F. Positive projections and health: an initial validation of the implicit psychological capital health measure. Appl Psychol Int Rev. (2017) 66:78–102. doi: 10.1111/apps.12077

31. Meneghel I, Martinez IM, Salanova M. Job-related antecedents of team resilience and improved team performance. Pers Rev. (2016) 45:505–22. doi: 10.1108/PR-04-2014-0094

32. Kinman G, Grant L. Exploring stress resilience in trainee social workers: the role of emotional and social competencies. Br J Soc Work. (2011) 41:261–75. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcq088

33. Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian General Practice Registrars. BMC Med Educ. (2013) 13:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-2

34. Harker R, Pidgeon AM, Klaassen F, King S. Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work. (2016) 54:631–7. doi: 10.3233/WOR-162311

35. Shoss MK, Jiang L, Probst TM. Bending without breaking: a two-study examination of employee resilience in the face of job insecurity. J Occup Health Psychol. (2018) 23:112–26. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000060

36. McLarnon MJ, Rothstein MG. Development and initial validation of the workplace resilience inventory. J Pers Psychol. (2013) 12:63–73. doi: 10.1037/t23880-000

37. Ferris PA, Sinclair C, Kline TJ. It takes two to tango: personal and organizational resilience as predictors of strain and cardiovascular disease risk in a work sample. J Occup Health Psychol. (2005) 10:225–38. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.3.225

38. Cavanaugh MA, Boswell WR, Roehling MV, Boudreau JW. an empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. Managers. J Appl Psychol. (2000) 85:65–74. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

39. Crane MF, Searle BJ. Building resilience through exposure to stressors: the effects of challenges versus hindrances. J Occup Health Psychol. (2016) 21:468–79. doi: 10.1037/a0040064

40. Lawal MA, Shalaby R, Chima C, Vuong W, Hrabok M, Gusnowski A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: stress, anxiety, and depression levels highest amongst indigenous peoples in Alberta. Behav Sci. (2021) 11:115. doi: 10.3390/bs11090115

41. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang Y-T, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e17–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

42. Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G, Di Marco A, Siracusano A, et al. Mental health outcomes among front and second line health workers associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. MedRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.16.20067801

43. Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, Di Domenico GE, Brown LA, White LK, et al. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl Psychiatry. (2020) 10:291. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4

44. Hartmann S, Weiss M, Newman A, Hoegl M. Resilience in the workplace: a multilevel review and synthesis. Appl Psychol. (2020) 69:913–59. doi: 10.1111/apps.12191

45. Cameron F, Brownie S. Enhancing resilience in registered aged care nurses. Australas J Ageing. (2010) 29:66–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00416.x

46. Jensen PM, Trollope-Kumar K, Waters H, Everson J. Building physician resilience. Can Fam Physician. (2008) 54:722–9.

47. Puyod JV, Charoensukmongkol P. The contribution of cultural intelligence to the interaction involvement and performance of call center agents in cross-cultural communication: the moderating role of work experience. Manag Res Rev. (2019) 42:1400–22. doi: 10.1108/MRR-10-2018-0386

48. Sommer SA, Howell JM, Hadley CN. Keeping positive and building strength: the role of affect and team leadership in developing resilience during an organizational crisis. Group Organ Manag. (2016) 41:172–202. doi: 10.1177/1059601115578027

49. Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, Panter-Brick C, Yehuda R. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumato. (2014) 5:25338. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

50. Wiseman TA, Curtis K, Lam M, Foster K. Incidence of depression, anxiety and stress following traumatic injury: a longitudinal study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. (2015) 23:29. doi: 10.1186/s13049-015-0109-z

51. Roberts NJ, McAloney-Kocaman K, Lippiett K, Ray E, Welch L, Kelly C. Levels of resilience, anxiety and depression in nurses working in respiratory clinical areas during the COVID pandemic. Respir Med. (2021) 176:106219. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106219

52. Nwachukwu I, Nkire N, Shalaby R, Hrabok M, Vuong W, Gusnowski A, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: age-related differences in measures of stress, anxiety and depression in Canada. Int J Env Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6366. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176366

53. Driessen M. Chinese workers in Ethiopia caught between remaining and returning. Pac Aff. (2021) 94:329–46. doi: 10.5509/2021942329

54. Al Maskari Z, Al Blushi A, Khamis F, Al Tai A, Al Salmi I, Al Harthi H, et al. Characteristics of healthcare workers infected with COVID-19: a cross-sectional observational study. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 102:32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.009

55. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. (2003) 18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

56. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:1019–28. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271

57. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

58. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

59. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. (1983) 24:385–96. doi: 10.2307/2136404

60. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford publications (2017).

61. Becker WJ, Curhan JR. The dark side of subjective value in sequential negotiations: the mediating role of pride and anger. J Appl Psychol. (2018) 103:74–87. doi: 10.1037/apl0000253

62. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. (2020) 16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

63. Förster C, Duchek S. What makes leaders resilient? An exploratory interview study. Ger J Hum Resour Manag. (2017) 31:281–306. doi: 10.1177/2397002217709400

64. Bonache J. Job satisfaction among expatriates, repatriates and domestic employees: the perceived impact of international assignments on work-related variables. Pers Rev. (2005) 34:110–24. doi: 10.1108/00483480510571905

65. Fletcher D, Sarkar M. Psychological resilience. Eur Psychol. (2013) 18:12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

67. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. (1989) 44:513–24. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

68. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience. Aust J Psychol. (2011) 66:82–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195375343.013.0007

69. Chen S, Westman M, Hobfoll SE. The commerce and crossover of resources: resource conservation in the service of resilience. Stress Health. (2015) 31:95–105. doi: 10.1002/smi.2574

70. Bitsika V, Sharpley CF, Bell R. The buffering effect of resilience upon stress, anxiety and depression in parents of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil. (2013) 25:533–43. doi: 10.1007/s10882-013-9333-5

71. Al Ariss A, Syed J. Capital mobilization of skilled migrants: a relational perspective. Br J Manag. (2011) 22:286–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00734.x

72. Walewski J, Gibson G. International Project Risk Assessment: Methods, Procedures, and Critical Factors. Center for Construction Industry Studies, University of Texas at Austin, Report (2003). p. 31.

73. Shen J, Wajeeh-ul-Husnain S, Kang H, Jin Q. Effect of outgroup social categorization by host-country nationals on expatriate premature return intention and buffering effect of mentoring. J Int Manag. (2021) 27:100855. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2021.100855

74. Song H, Varma A, Zhang Zhang Y. Motivational cultural intelligence and expatriate talent adjustment: an exploratory study of the moderation effects of cultural distance. Int J Hum Resour Manag. (2021) 1–25. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2021.1966491 [Epub ahead of print].

75. Fradelos EC, Alikari V, Vus V, Papathanasiou IV, Tsaras K, Tzavella F, et al. Assessment of the relation between religiosity, anxiety, depression and psychological resilience in nursing staff. Health Psychol Res. (2020) 8:8234. doi: 10.4081/hpr.2020.8234

76. Liu Y, Mattar MG, Behrens TE, Daw ND, Dolan RJ. Experience replay is associated with efficient nonlocal learning. Science. (2021) 372:eabf1357. doi: 10.1126/science.abf1357

Keywords: COVID-19 related stressors, psychological resilience, mental health, international assignments experience, expatriates, international construction

Citation: Gao L, Deng X, Yang W and Fang J (2022) COVID-19 related stressors and mental health outcomes of expatriates in international construction. Front. Public Health 10:961726. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.961726

Received: 05 June 2022; Accepted: 24 June 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

Hanliang Fu, Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Jin Zhu, University of Connecticut, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Gao, Deng, Yang and Fang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaopeng Deng, ZHhwQHNldS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.