94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 23 September 2022

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.956214

This article is part of the Research Topic Adaption to Change and Coping Strategies: New Resources for Mental Health View all 29 articles

Objective: Drawing on the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM), the present study investigated the relationship between Chinese middle-aged and old couples' Confucian coping thinking and their marital quality in the hope to provide a theoretical basis for ameliorating marital quality.

Methods: With 744 middle-aged and old couples as participants, the Confucian Coping Questionnaire (CCQ) and the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI) were employed to probe the relationship between responsibility thinking (RT), pro-setback thinking (PT), fate thinking (FT), and marital quality.

Results: Husbands' and wives' scores in responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking had significantly positive correlations with their own and their spouses' scores in marital quality, respectively, and husbands' and wives' scores in fate thinking had significantly negative correlations with their own and their spouses' marital quality, respectively. Husbands' responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking had a significant actor effect. Husbands' responsibility thinking and fate thinking had a significant partner effect. Wives' responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking had a significant actor effect. Wives' responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking had a significant partner effect.

Conclusion: From the perspective of dyadic relationships, the present study found that responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking could positively predict marital quality, while pro-setback thinking could negatively predict marital quality.

For most people, establishing and maintaining a meaningful and positive marital relationship is an indispensable experience in their lives. Marital quality is regarded as the main indicator of marital harmony and marital stability (1). How to improve marital quality is always one of the hotspots in the marriage and family field. Marital quality is couples' subjective evaluation of their marital satisfaction and marital harmony (2). Inferior marital quality not only can negatively predict individuals' psychological health (3) but also can impair physical health (4). On the contrary, superior marital quality can be beneficial to improving marital stability (5), reducing psychological distress (6), mitigating loneliness, (7), and buffering negative emotions' adverse effects (8). Besides, related to individuals' physical activity and health behaviors, marital quality can also predict one's physical health (9). In general, individuals with higher marital quality have higher cognitive health (10), better sleep quality (11), less pain (12), and fewer disease risks (13). Moreover, low parental marital quality can also lower adolescent psychological wellbeing (14).

Coping approaches are a key predictor of marital quality (15). There might be stress, divergence, arguments, and even fights in any marriage, although a great marital relationship is expected by couples (16). The vulnerability-stress-adaptation (VSA) model assumes that the coping approaches adopted by couples in the face of daily life events and marital stress are directly associated with their subjective perception and evaluation of marriage (17). Positive emotional expressions and search for solutions can positively predict marital quality, while negative emotional expressions and avoidance of problems can negatively predict marital quality (18). On balance, coping approaches in marriage can be divided into positive and negative ones. Positive coping approaches are conducive to mitigating emotional distress between couples and enhancing the level of perceived social support for couples (19) and ameliorating marital quality (20). By contrast, negative coping approaches can be destructive to marital quality (21), and even negatively impact individuals' marital quality in a long run (22).

Coping approaches clearly show cultural characteristics, since individuals in different cultural contexts have different perceptions, evaluations, and selection of coping objectives and approaches (23). Chinese traditional culture is a composite of multiple cultures represented by Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. As the mainstream culture, Confucianism has greatly contributed to Chinese people's ideology, behavioral patterns, and psychological health (24). Confucianism has a rich discussion of how individuals deal with stress and setbacks. Different from the western culture, which assumes that stress derives from external or specific life events, Confucianism regards stress as the corollary of insufficient self-cultivation and emphasizes that the ideal coping approaches should be “unity of knowledge and action,” namely, individuals constantly improve their ability to cope with stress through moral cultivation, meanwhile cultivating their morality through specific practice (25). Furthermore, cultural differences may also be shown in the outcome of coping in the Chinese and Western contexts (26).

Confucian coping thinking refers to Chinese people's mindset in coping with difficulties and setbacks under the influence of Confucian culture, which mainly comprises responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking (27). As an important component of Confucianism, responsibility thinking assumes that individuals have responsibility for themselves, others, society, and all things in the world (28). “Cultivating the self, regulating the family, governing the country, and pacifying the world” are the crucial political ideals of Confucianism. Accordingly, a person's responsibility extends from himself to the family, the country, and even the world. Family is not only the basic unit of social organization but also the hub connecting individuals and countries. Responsibility for the family is often regarded as one's most important responsibility (29). Individuals with high responsibility thinking, whether in good or bad times, tend to voluntarily take responsibility and actively handle and solve a variety of negative events. Although Confucianism agrees that setbacks can bring pain and tension, it also believes that setbacks can effectively hone oneself and benefits one's growth (30). Individuals with high pro-setback thinking pay more attention to the positive aspects of hardship and believe that the key to success is to accept, face and overcome setbacks through their own efforts (31). Moreover, fate thinking plays a vital role in Confucian culture and greatly contributes to the coping approaches of Chinese people. Individuals with high fate thinking think that their fate is predetermined so that when encountering difficulties, they have a stronger sense of powerlessness and are less likely to seek solutions to problems (27).

Although the relationship between coping approaches and marital quality has been widely demonstrated, few studies have investigated the effect of coping approaches on marital quality from the cultural perspective (32). Since individuals' coping approaches are closely associated with their cultural contexts (33), Chinese couples would inevitably show certain coping characteristics in conformity with Chinese culture. In most cases, responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking are connected to positive psychological and behavioral outcomes, while fate thinking is connected to negative outcomes (31). According to previous studies, individuals' responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking are positively correlated with psychological resilience and negatively correlated with anxiety and depression (26, 27). Besides, psychological resilience is considered to increase marital quality (34), whereas anxiety and depression are regarded to decrease marital quality (35). In addition, responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking are the major constituents of positive Confucian ideology. Confucianism believes that the happiness brought by fulfilled personal needs is based on voluntarily taking responsibility and strenuously surmounting difficulties (30). Hence, individuals with high responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking can face frustrations with more equanimity and handle the problems in marriage with more optimism, which can improve marital quality. Therefore, it seems reasonable to postulate that responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking can positively predict marital quality, whereas fate thinking could negatively predict marital quality.

Dyadic relationships are the basic unit of interpersonal interaction (36). Since marital relationships are the closest interpersonal relationship, one party's notions and behaviors indispensably have effects on another party, which is particularly remarkable in China where interpersonal connections are highly emphasized (37). Self includes independent self and interdependent self, and Chinese people prioritize society-oriented interdependent self (38). Individuals with high interdependent self tend to regard themselves as a part of relationships, expect more to gain recognition from others, and consider the needs of others (39). Family systems theory assumes that the family can be divided into three subsystems of marital, parent–child, and sibling relationships. The same and different subsystems are interrelated and interacted (40). Since marital relationships are the most crucial subsystem, couples have strong interdependence in cognition, emotion, and behavior (41). Hence, it seems advisable to presume that husbands' or wives' Confucian coping thinking not only can affect their own marital quality but also likely affect their spouses' marital quality.

The APIM is widely employed in the analysis of dyadic data. The actor effect refers to the effect of individuals' predictor variables on their own outcome variables, while the partner effect comes to the effect of individuals' predictor variables on their partner's outcome variables (42). Unfortunately, although a multitude of studies have indicated that couples' coping approaches can predict both their own and their spouses' marital quality (32, 43), so far, no study has probed the relationship between Confucian coping thinking and marital quality using the APIM. It's noteworthy that several studies found that gender differences may exist in the partner effect of coping approaches on marital quality (44). Brandão et al. found that both husbands' and wives' dyadic coping had an actor effect on marital quality, but only husbands had a partner effect on marital quality (45). The longitudinal research also demonstrated that couples' coping approaches have different effects on their spouses' marital quality (46). Hence, it can be extrapolated that Confucian coping thinking is probably related to both one's own (the actor effect) and their spouses' marital quality (the partner effect).

According to the above analysis, several gaps in the extant literature can be crystallized. First, a paucity of studies has explored the relationship between Confucian coping approaches and marital quality, notwithstanding its cultural significance. Second, few studies have applied the APIM to probe this relationship, although it offers an effective framework. Given the existing gaps in research, we aimed to culturally investigate this relationship using the APIM. More specifically, we hypothesized that individuals' responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking were positively correlated with their own and their spouses' marital quality, and fate thinking was negatively correlated with their own and their spouses' marital quality.

The inclusion criteria for participants are: (1) Marital length≥15 years, (2) Age≥40 (both husbands and wives) (47), and (3) Couples who volunteered for the survey and signed the informed consent. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin International Studies University.

A household survey was conducted by systematically trained college students among middle-aged and old couples in their hometowns. Participants were from eight provinces of China, namely, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, and Gansu. Data collection was based on convenient sampling and snowball sampling. More specifically, researchers first had a survey on their acquaintances like relatives, friends, and neighbors. Afterward, researchers requested these acquaintances to recommend new participants meeting the inclusion criteria. By the same token, these new participants were requested to provide other new participants. In this way, sample sizes were continuously expanded. It should be noted that the survey was conducted face to face.

Before the survey, participants were informed of the purpose, the way to complete the questionnaire, confidentiality, and anonymity. Besides, participants' questions about the survey were answered, and their permission was obtained. After the paper informed consent was signed, each couple got a code for matching the data. After that, participants were sent a link for the survey from researchers to complete the online questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered separately to husbands and wives in case they influence each other. If participants had difficulties in reading the questionnaire due to their low educational level or poor eyesight, researchers would read and fill out the questionnaire for them. After the survey, researchers checked the data and removed invalid questionnaires. The criteria for removal are as follows: (1) The response time of husbands/wives was too short (<120 s). (2) Both positive and negative items were responded to the same. (3) The data could not be matched.

A total of 813 husband-reported questionnaires were collected, of which, 13 questionnaires were dropped for both positive and negative items being responded to the same, 28 questionnaires were removed for response time being too short (<120 s), and then 769 questionnaires were retained. A total of 821 mother-reported questionnaires were collected, of which, 17 questionnaires were dropped for both positive and negative items being responded to the same, 37 questionnaires were removed for response time being too short (<120 s), and then 783 questionnaires were retained. Finally, 744 sets of valid data were collected. Regarding residence, 414 (55.65%) couples lived in the city, and 330 (44.35%) couples lived in the countryside. Concerning marital length, it ranged from 15 to 59 years (Mean ± SD = 29.77 ± 12.99). Regarding annual family income, 74 couples earned <10,000 yuan (9.95%), 159 couples earned between 10,000 and 30,000 yuan (21.37%), 158 earned between 30,000 and 50,000 yuan (21.24%), 181 couples earned between 50,000 and 100,000 yuan (24.33%), 90 couples earned between 100,000 and 150,000 yuan (12.10%), 55 couples earned between 160,000 and 250,000 yuan (7.39%), 22 couples earned between 250,000 and 500,000 yuan (2.95%), and 5 couples earned more than 500,000 yuan (0.67%). Regarding age, husbands aged from 40 to 79 (Mean ± SD = 55.14 ± 11.67) and wives aged from 40 to 77 (Mean ± SD = 53.65 ± 12.12).

The Confucian Coping Questionnaire (CCQ) was first developed by Jing Huaibin and then revised by Yang Muzi (27). The scale consists of 11 items divided into three dimensions of responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking, scored on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Among them, items 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9 come to responsibility thinking, items 1, 5, and 11 belong to pro-setback thinking, and items 2, 6, and 10 refer to fate thinking. The sum of all item scores is the total scores. The higher scores in responsibility thinking, the more recognition of taking responsibility. The higher scores in pro-setback thinking, the more positive attitude toward setbacks, and the more identification with setbacks' benefits on one's growth. The higher scores in fate thinking, the more approval for fate thinking. Item examples in each dimension: “People should naturally take social responsibility,” “Only those experiencing many setbacks can be successful,” and “A good or bad life is determined by external and mysterious fate.” In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficients of responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking were 0.795, 0.718, and 0.704 for husbands, respectively, and 0.789, 0.707, and 0.705 for wives, respectively.

Developed by Norton in 1983, the Chinese version of the Quality of Marriage Index (QMI) was employed (48, 49). The scale with one dimension is composed of six items. Participants answer the first five items on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The sixth item is answered on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely low) to 10 (extremely high). The sum of all item scores is the total scores, with higher scores indicating higher marital quality. Item examples: “My relationship with my partner is very stable” and “My relationship with my partner makes me happy.” In the present study, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.929 for husbands and 0.927 for wives.

Descriptive statistics and item analysis were performed using SPSS 26.0. The correlation between the variables between husbands and wives was tested using Pearson's correlation coefficient. The APIM was tested using an online free web application called APIM_SEM (50). With maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), the analyses used structural equation modeling (SEM) using the program R package lavaan (51). Three APIMs were constructed to test the effect of couples' responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking on their own and their spouses' marital quality, respectively. When examining the APIM, we set marital length, annual family income, and residence as the control variables. The actor effect refers to the effect of individuals' predictor variables on their own outcome variables, while the partner effect comes to the effect of individuals' predictor variables on their partner's outcome variables. For instance, in the present study, the husbands' actor effect refers to the predictive effect of husbands' Confucian coping thinking on their own perceived marital quality, whereas the husbands' partner effect comes to the predictive effect of wives' Confucian coping thinking on husbands' marital quality. The standard model of the APIM was saturated and just-identified. Four general dyadic patterns include the actor-only, the couple, the contrast, and the mixed patterns. In the analysis of dyadic patterns, k-values, used to measure dyadic patterns, are the ratio of the partner effect to the actor effect. Only when the standardized absolute values of the actor effect are higher than 0.10 and statistically significant, k-values can be computed. With 5,000 bootstrap iterations, the confidence interval (CI) for k-values was computed, and if 1, 0, or −1 was in the CI was evaluated. If 0 is in the CI, the model is the actor-only pattern; if 1 is in the CI, the model is the couple pattern; if −1 is in the CI, the model is the contrast pattern (52); if the CI is between 0 and 1, it suggests that the APIM is between the couple pattern and the actor-only pattern, called the mixed pattern (53). Although dyadic relationships are distinguished by the role (husband vs. wife), their actor and partner effects probably cannot be distinguished (54). Two steps are needed to examine whether dyad members are distinguishable or indistinguishable. First, test if the actor and partner effects can be set equal. In this step, the actor and partner effects of the dyadic data are set equal to test whether the chi-square value significantly changes. The insignificant change in the chi-square value (p > 0.05) indicates that the actor and partner effects as the dyad numbers are probably indistinguishable (52). Second test indistinguishable dyad members. In this step, a model with complete indistinguishability is constructed by setting equal means and variances of the causal variables, intercepts of the outcome variables, error variances, actor effects, and partner effects (55). To test if gender makes a statistically significant difference, model comparison is performed by a chi-square test between a model with distinguishable members and a model with indistinguishable members. If p < 0.05, it suggests that members can be statistically distinguished by gender.

Table 1 lists the mean and standard deviation of the scores of husbands and wives in the CCQ and the QMI. As illustrated in Table 2, the scores of husbands and wives in responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking were significantly positively correlated with their own and their spouses' marital quality, respectively. The scores of husbands and wives in fate thinking were significantly negatively correlated with their own and their spouses' marital quality, respectively.

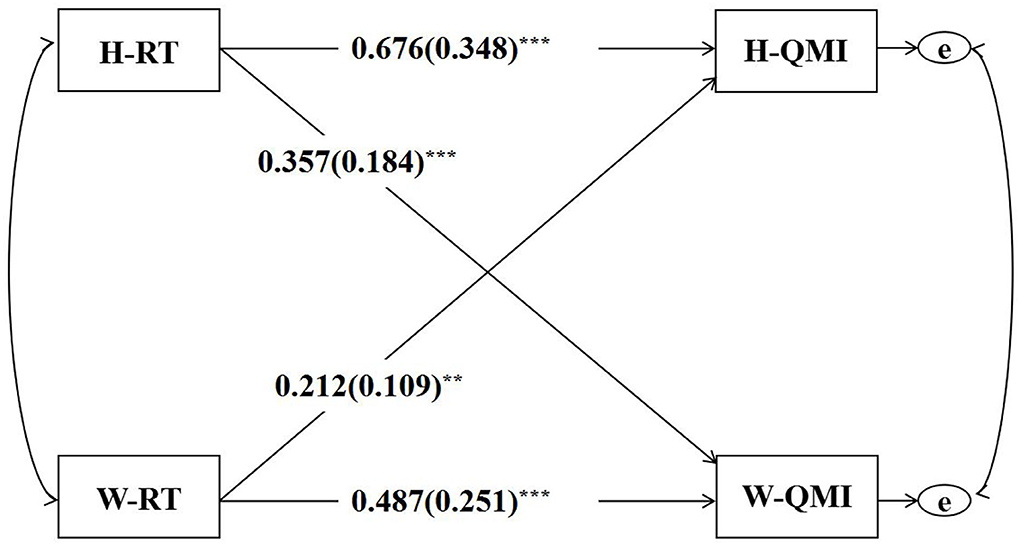

Three APIMs for the predictive effect of responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking on marital quality were constructed, respectively (see Table 3). Specifically, the APIM for the predictive effect of couples' responsibility thinking on marital quality is illustrated in Figure 1, and the actor and partner effects for husbands and wives are presented in Table 2. When tested if the two actor effects were equal, the difference was found not to be statistically significant [p = 0.070, 95%CI (−0.02, 0.39)]. Additionally, when tested if the two partner effects were equal, the difference was found not to be statistically significant [p = 0.152, 95% CI (−0.34, 0.05)]. Husbands' k-value was 0.313 with a 95% CI between 0.110 and 0.571 (the CI was between 0 and 1), suggesting that the pattern was a mixed pattern. The wives' k-value was 0.734 with a 95% CI between 0.401 and 1.263 (1 was in the CI), suggesting the couple pattern. Besides, the two k-values showed no significant difference [p = 0.132, 95% CI (−1.04, 0.07)]. Whether the pattern was with distinguishable dyad members was further tested. According to the results, χ2(15) was equal to 192.21 and p was lower than 0.001, suggesting that the predictive effect of husbands' and wives' responsibility thinking on marital quality was statistically distinguishable dyad members by gender.

Figure 1. The APIM for RT's predictive effect on QMI. RT, responsibility thinking; QMI, quality of marriage index; H, husband; W, wife; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

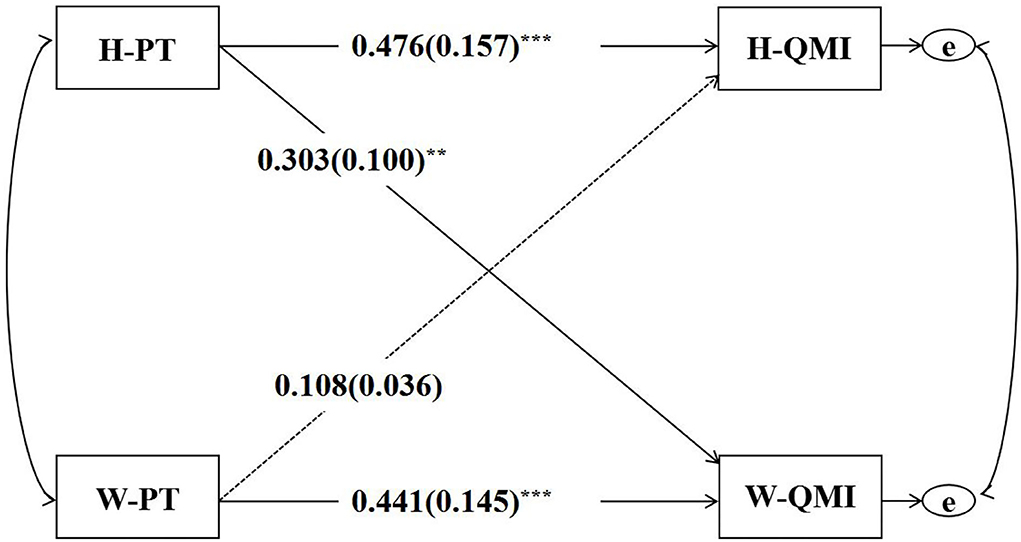

The APIM for the predictive effect of couples' pro-setback thinking on marital quality is shown in Figure 2, and the actor and partner effects for husbands and wives are presented in Table 2. When tested if the two actor effects were equal, the difference was found not to be statistically significant [p = 0.823, 95% CI (−0.27, 0.34)]. In addition, when tested if the two partner effects were equal, the difference was found not to be statistically significant [p = 0.186, 95% CI (−0.48, 0.09)]. Husbands' k-value was 0.227 with a 95% CI between −0.181 and 0.853 (0 was in the CI), suggesting the actor-only pattern. Wives' k-value was 0.686 with a 95% CI between 0.191 and 1.778 (1 was in the CI), suggesting the couple pattern. In addition, the two k-values showed no significant difference [p = 0.426, 95% CI (−1.71, 0.44)]. Whether the model was with distinguishable dyad members was further tested. Based on the results, χ2(15) was equal to 156.15 and p was lower than 0.001, suggesting that the predictive effect of husbands' and wives' pro-setback thinking on marital quality was statistically distinguishable dyad members by gender.

Figure 2. The APIM for PT's predictive effect on QMI. PT, pro-setback thinking; QMI, quality of marriage index; H, husband; W, wife; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

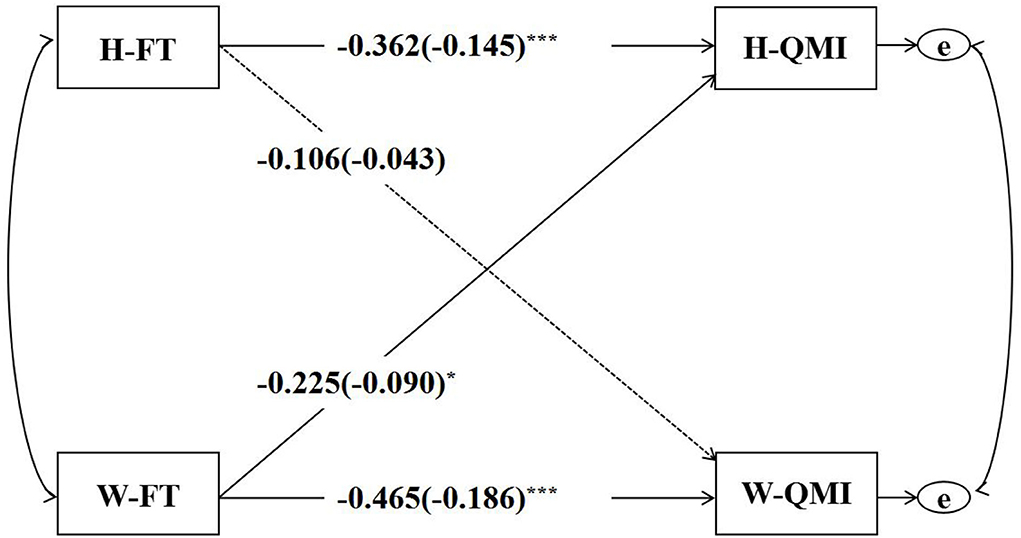

The APIM for the predictive effect of couples' fate thinking on marital quality is shown in Figure 3, and the actor and partner effects for husbands and wives are presented in Table 2. When tested if the two actor effects were equal, the difference was found not to be statistically significant [p = 0.489, 95% CI (−0.19, 0.40)]. Besides, when tested if the two partner effects were equal, the difference was found not to be statistically significant [p = 0.407, 95% CI (−0.41, 0.16)]. Husbands' k-value was 0.621 with a 95% CI between 0.090 and 2.021 (1 was in the CI), suggesting the couple pattern. Wives' k-value was 0.229 with a 95% CI between −0.149 and 0.822 (0 was in the CI), suggesting the actor-only pattern. In addition, the two k-values showed no significant difference [p = 0.672, 95% CI (−0.54, 1.93)]. Whether the model was with distinguishable dyad members was further tested. According to the results, χ2(15) was equal to 174.92 and p was lower than 0.001, suggesting that the predictive effect of husbands' and wives' fate thinking on marital quality was statistically distinguishable dyad members by gender.

Figure 3. The APIM for FT's predictive effect on QMI. FT, fate thinking; QMI, quality of marriage index; H, husband; W, wife; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

The studies pertaining to coping approaches and marital quality have always been the hotspot of marriage and family fields. Marital quality, as individuals' subjective feelings, is not static. Influenced by social culture, personality traits, interaction modes, attachment styles, and so forth, marital quality is always a dynamic process. Among a variety of factors, coping approaches play a vital role in affecting marital quality (56). People in the same cultural context may show certain common characteristics (15). As the mainstream culture of China, Confucianism has shaped the value judgment and behavioral patterns of Chinese people. Although an increasing number of scholars have realized that coping approaches have clear cultural characteristics (57), hitherto, no study has probed the relationship between Confucian coping approaches and marital quality. Particularly, no study has used dyadic data to investigate the relationship between the actor and partner effects of husbands' and wives' responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, and fate thinking on marital quality. Based on the APIM, the present study, with middle-aged and old couples as participants, investigated the predictive effect of Confucian coping thinking on individuals' own and their spouses' marital quality. At present, China has been facing the social problem of a rising divorce rate (58). Marital quality has been considered the most important predictor of marital stability (59). The results of the present study can be conducive to deepening the understanding of the relationship between Confucian coping thinking and marital quality, so as to provide theoretical reference for improving marital quality and reducing the divorce rate.

In the APIM for the predictive effect of responsibility thinking on marital quality, both husbands' and wives' responsibility thinking could significantly positively predict their own and their spouses' marital quality. Responsibility thinking is the premise of developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships. According to previous studies, responsibility can improve marital quality (60). To the authors' knowledge, the present study is the first one that investigated the relationship between responsibility thinking and marital quality and drew a similar conclusion. Responsibility's contribution to a marriage has been identified in both Chinese and western cultures, although in the two cultures, the emphasis and view on responsibility are not identical, and the connotation and manifestation of responsibility are also different. Confucianism regards the self as a kind of “relational self,” and believes that everyone should be responsible for others in a relationship, which requires individuals to actively improve their self-cultivation in order to better take their responsibility (61). As the most basic social relationship, marital relationships are considered a person's main responsibility (62). Both husbands and wives have the responsibility to jointly maintain the stability, sustainability, and harmony of marriage. Influenced by Confucianism's view on family, individuals attaching importance to marital harmony tend to voluntarily take family responsibility and even sacrifice their own interests (63).

In the APIM of the predictive effect of pro-setback thinking on marital quality, both husbands' and wives' pro-setback thinking could significantly positively predict their own marital quality, which was consistent with the hypothesis. However, only husbands' pro-setback thinking could positively wives' marital quality, which was not in line with the hypothesis. Based on previous studies, the predictive effect of couples' coping approaches on marital satisfaction is not identical (56). For instance, Bodnmann et al. found that husbands' positive coping approaches were positively correlated with couples' marital quality, while wives' positive approaches were only correlated with their own marital quality and were not correlated with their husbands' marital quality (46). Pro-setback thinking, as a sort of positive coping thinking, also shares the same predictive effect. Confucianism assumes that both men and women should take responsibility in line with their gender, identity, and status, and act accordingly. On the contrary, the cultivation of pro-setback thinking is more aimed at men. Confucianism regards “improving oneself,” “striving for progress,” and “daring to take responsibility” as important spiritual characteristics of a “gentleman” personality (64). Confucianism insists that men should hold a positive attitude toward the setbacks and hardships encountered in their careers and growth. In addition, Confucianism's concept of hierarchy is also reflected in marital relationships, assuming that women should be subordinate and obedient to men (65). Women's happiness is largely dependent on men's career achievements. Setbacks are considered the key to self-transcendence and success (31). Therefore, husbands' optimistic attitude in handling and overcoming setbacks means that they are more likely to succeed in the future, which can enhance the wife's evaluation of marital quality.

In the APIM of the predictive effect of fate thinking on marital quality, both husbands and wives had actor and partner effects, namely, both husbands' and wives' fate thinking could significantly negatively predict their own marital quality, which was consistent with the hypothesis. According to previous studies, fate thinking, different from responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking, can negatively predict individuals' psychological health, emotional experience, and psychological resilience (27, 31). The present study also demonstrated in the marital relationship field that fate thinking was negative. Fate thinking shows individuals' inclination of attributing it to external uncontrollable factors when encountering stress. Individuals with higher fate thinking are more inclined to attribute the good or bad results to “fate,” and passively accept and comply with the “predetermined” results (66). The idea of “obeying fate” can cause uncontrollability and powerlessness. Individuals with high fate thinking usually take tolerant and passive approaches in coping with the confrontation and dissatisfaction in marriage, which may cause a decline in marital quality.

In the analysis of the partner effect, the present study only found that wives' fate thinking could negatively predict their husbands' marital quality, while husbands' fate thinking could not significantly predict their wives' marital quality, which was not completely consistent with the hypothesis. Fate is a complicated concept, comprising three dimensions: “fearing fate,” “obeying fate” and “utilizing fate.” Among them, “fearing fate” is the most negative attitude toward fate. Individuals fearing fate tend to believe that everyday issues have already been ordained by fate, and then passively accept them. In Confucianism's view on marriage, women have no free choice of their husbands, so their perceived marital quality is completely dependent on their predetermined husbands, which manifests in “fearing fate” (67). In other words, women would blame their marital miseries on the fate of failing to marry a good husband (68). Women's complaints about their husbands and marriage could negatively affect their own and their husbands' marital quality. In addition, different from the view of women, Confucianism emphasizes that “Junzi” (gentlemen) should “obey fate.” With the prerequisite of fate being unchangeable, “obeying fate” assumes that personal morality could be strengthened to realize, understand, and obey fate (69). Confucianism believes that a “Junzi” should always strengthen his self-cultivation, although it is a very difficult and long process from “fearing fate” to “obeying fate.” Therefore, men are more inclined to ascribe the negative effect of fate to their lack of self-cultivation, which properly justifies husbands' FT only negatively predicting their own perceived marital quality but failing to significantly predict their wives' marital quality.

Adopting the APIM, the present study investigated the relationship between Confucian coping thinking and marital quality. The present study has certain theoretical significance, as it is an expansion and supplement to the Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) Model and the family systems theory. In addition, the present study also has certain practical significance, as it can serve as a reference for marriage therapy and family intervention. From the perspective of culture, different and targeted measures can be developed to improve marital quality. Moreover, marital quality can also be enhanced by cultivating couples' responsibility thinking and pro-setback thinking and reducing their fate thinking. It is noteworthy that although Confucian coping thinking is relatively stable and significantly correlated with marital quality, individuals' coping approaches are by no means invariable, and the specific strategies shown in a specific context of stress are affected by internal and external factors (70). More specifically, the coping approaches adopted by couples in handling and solving various problems or stress in marriage are also related to both the thinking and context at that time (71). Hence, in the intervention of marital quality, the psychological features, interaction modes, family of origin, economic status, and other factors of couples also need to be investigated comprehensively, in addition to the role of Confucian coping thinking.

The present study also has some limitations. First, a cross-sectional survey was used in the present study, so the causality between Confucian coping thinking and marital quality is hard to be explained. A longitudinal survey needs to be conducted in future work to probe how Confucian coping thinking affects marital quality as time rolls on. Second, the data were collected by self-report measures, which may cause recall bias. Besides, China has the concept of “don't wash your dirty linen in public,” which possibly leads to the inaccuracy of the results under the Social Desirability Effect. Third, in the process of China's modernization, Chinese culture is characterized by diversity. Especially, younger people are deeply influenced by western culture (72). Consequently, in terms of Confucian coping thinking, as well as the attitude and evaluation of marital quality, young couples may show relatively huge differences from their middle-aged and old counterparts. Therefore, whether the results in the present study are applicable to young couples still needs more empirical evidence. Fourth, the sample was insufficient in representativeness, since participants were all recruited from college students' acquaintances based on convenient sampling and snowball sampling. Therefore, random sampling can be adopted in future work to further examine the relationship between Confucian coping thinking and marital quality.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin International Studies University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This study was supported by the Higher Education Research Project of Jilin Province (jgjx2021D149) and the Social Science Funding Support Project for PhDs and Youth of Jilin Province (2022C8).

We are very much thankful to all the researchers for data collection and processing. We also thank all the survey participants in our study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. James SL. Variation in marital quality in a national sample of divorced women. J Fam Psychol. (2015) 29:479–89. doi: 10.1037/fam0000082

2. Delatorre MZ, Wagner A. Marital quality assessment: reviewing the concept, instruments, and methods. Marriage Fam Rev. (2020) 56:193–216. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2020.1712300

3. Alipour Z, Kazemi A, Kheirabadi G, Eslami A-A. Relationship between marital quality, social support and mental health during pregnancy. Community Ment Health J. (2019) 55:1064–70. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00387-8

4. Lee HJ, Han SH, Boerner K. Psychological and physical health in widowhood: does marital quality make a difference? Res Aging. (2022) 44:54–64. doi: 10.1177/0164027521989083

5. Yu Y, Wu D, Wang J, Wang Y. Dark personality, marital quality, and marital instability of chinese couples: an actor-partner interdependence mediation model. Pers Individ Differ. (2020) 154:109689. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109689

6. Sadiq U, Rana F, Munir M. Marital quality, self-compassion and psychological distress in women with primary infertility. Sex Disabil. (2022) 40:167–77. doi: 10.1007/s11195-021-09708-w

7. Marini CM, Ermer AE, Fiori KL, Rauer AJ, Proulx CM. Marital quality, loneliness, and depressive symptoms later in life: the moderating role of own and spousal functional limitations. Res Hum Dev. (2020) 17:211–34. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2020.1837598

8. Bulanda JR, Yamashita T, Brown JS. Marital quality, gender, and later-life depressive symptom trajectories. J Women Aging. (2021) 33:122–36. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2020.1818538

9. Thomas PA, Richards EA, Forster AK. Is marital quality related to physical activity across the life course for men and women? J Aging Health. (2022). doi: 10.1177/08982643221083083

10. Kim Y. Gender differences in the link between marital quality and cognitive decline among older adults in Korea. Psychiatry Investig. (2021) 18:1091–9. doi: 10.30773/pi.2021.0131

11. August K. Marital status, marital transitions, and sleep quality in mid to late life. Res Aging. (2022) 44:301–11. doi: 10.1177/01640275211027281

12. Wilson SJ, Martire LM, Zhaoyang R. Couples' day-to-day pain concordance and marital interaction quality. J Soc Pers Relat. (2019) 36:1023–40. doi: 10.1177/0265407517752541

13. Bennett-Britton I, Teyhan A, Macleod J, Sattar N, Davey Smith G, Ben-Shlomo Y. Changes in marital quality over 6 years and its association with cardiovascular disease risk factors in men: findings from the alspac prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2017) 71:1094–100. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209178

14. Wahyuningsih H, Kusumaningrum FA, Novitasari R. Parental marital quality and adolescent psychological well-being: a meta-analysis. Cogent Psychol. (2020) 7:1819005. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2020.1819005

15. Kim WJ, Yu S. Psychological adaptation among marriage migrant women in South Korea: stress and coping, culture learning, and social cognition approaches. Am J Fam Ther. (2021) 50:1–18. doi: 10.1080/01926187.2021.1934752

16. Batista da Costa C, Pereira Mosmann C. Conflict resolution strategies and marital adjustment of heterosexual couples: assessment of actor–partner interaction. J Fam Issues. (2021) 42:2711–31. doi: 10.1177/0192513X20986974

17. Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: a review of theory, method, and research. Psychol Bull. (1995) 118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3

18. Chow CM, Buhrmester D, Tan CC. Interpersonal coping styles and couple relationship quality: similarity versus complementarity hypotheses. Eur J Soc Psycholy. (2014) 44:175–86. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2000

19. Yazdani F, Kazemi A, Fooladi MM, Samani HR. The relations between marital quality, social support, social acceptance and coping strategies among the infertile iranian couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2016) 200:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.034

20. Falconier MK, Jackson JB, Hilpert P, Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2015) 42:28–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.002

21. Kim B, Kim J, Moon SS, Yoon S, Wolfer T. Korean women's marital distress and coping strategies in the early stage of intercultural marriages. J Ethn Cult Divers. (2021) 30:523–41. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2020.1753616

22. Pihet S, Bodenmann G, Cina A, Widmer K, Shantinath S. Can prevention of marital distress improve well-being? a 1 year longitudinal study. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2007) 14:79–88. doi: 10.1002/cpp.522

23. Agadullina E, Belinskaya E, Dzhuraeva M. Personal and situational predictors of proactive coping with difficult life situations: cross-cultural differences. Natl Psychol J. (2020) 39:30–8. doi: 10.11621/npj.2020.0304

24. Yao C, Duan Z, Baruch Y. Time, space, confucianism and careers: a contextualized review of careers research in china – current knowledge and future research agenda. Int J Manag. (2020) 22:222–48. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12223

25. Lu Y. Wang yangming's theory of the unity of knowledge and action revisited: an investigation from the perspective of moral emotion. Philos East West. (2019) 69:197–214. doi: 10.1353/pew.2019.0006

26. Zhou L, Chen G, Jiang Y, Liu L, Chen J. Self-compassion and confucian coping as a predictor of depression and anxiety in impoverished Chinese undergraduates. Psychol Rep. (2017) 120:627–38. doi: 10.1177/0033294117700857

28. Ren Y. Exploration into Chinese traditional confucian thoughts on responsibility. Acta Psychol Sin. (2008) 40:1221–8. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2008.01221

29. Rosemont H. Against Individualism: A Confucian Rethinking of the Foundations of Morality, Politics, Family, and Religion. LanHam: Lexington Books (2005).

30. Huo Y, Chen Y, Guo Z. An exploration on the inter complementary optimistic psychological thoughts of the Confucianism and Taoism in the traditional Chinese culture. Acta Psychol Sin. (2013) 45:1305–12. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2013.01305

31. Li T, Hou Y. Psychological structure and psychometric validity of the Confucian coping. J Educ Sci Hunan Norm Univ. (2012) 11:11–8.

32. An H, Chen C, Du R, Cheng C, Wang P, Dong S. Self-efficacy, psychological distress, and marital quality in young and middle-aged couples facing lymphoma: the mediating effect of dyadic coping. Psychooncology. (2021) 30:1492–501. doi: 10.1002/pon.5711

33. Lam A, Zane N. Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors: a test of self-construals as cultural mediators. J Cross Cult Psychol. (2004) 35:446–59. doi: 10.1177/0022022104266108

34. Aydogan D, Dinçer D. Creating Resilient Marriage Relationships: Self-Pruning and the Mediation Role of Sacrifice with Satisfaction. Curr Psychol. (2020) 39:500–10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00472-x

35. Barton AW, Lavner JA, Sutton NC, McNeil Smith S, Beach SRH. African Americans' relationship quality and depressive symptoms: a longitudinal investigation of the marital discord model. J Fam Psychol. (2022). doi: 10.1037/fam0000967 [Epub ahead of print].

36. Lee H, Kang HS, De Gagne JC. Life satisfaction of multicultural married couples: actor-partner interdependence model analysis. Health Care Women Int. (2021) 2:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2021.1894151

37. Jiang Y, Lin X, Hinshaw SP, Chi P, Wu Q. Actor-partner interdependence of compassion toward others with qualities of marital relationship and parent-child relationships in Chinese families. Fam Process. (2020) 59:740–55. doi: 10.1111/famp.12436

38. Fan W, Li M, Leong F, Zhou M. West meets east in a new two-polarities model of personality: combining self-relatedness structure with independent-interdependent functions. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:739900. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.739900

39. Moscardino U, Miconi D, Carraro L. Implicit and explicit self-Construals in Chinese-heritage and Italian nonimmigrant early adolescents: associations with self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Dev Psychol. (2020) 56:1397–412. doi: 10.1037/dev0000937

40. Cox MJ, Paley B. Understanding families as systems. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. (2003) 12:193–6. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01259

41. Terrone G, Mangialavori S, Lanza di Scalea G, Cantiano A, Temporin G, Ducci G, et al. The relationship between dyadic adjustment and psychiatric symptomatology in expectant couples: an actor-partner interdependency model approach. J Affect Disord. (2020) 273:468–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.040

42. Kenny D. Reflections on the actor–partner interdependence model. Pers Relat. (2018) 25:160–70. doi: 10.1111/pere.12240

43. Brown M, Whiting J, Fessler E, Banford Witting A, Jensen J. A dyadic model of stress, coping, and marital satisfaction among parents of children with autism. Fam Relat. (2020) 69:138–50. doi: 10.1111/fare.12375

44. Chaves C, Canavarro MC, Moura-Ramos M. The role of dyadic coping on the marital and emotional adjustment of couples with infertility. Fam Process. (2019) 58:509–23. doi: 10.1111/famp.12364

45. Brandão T, Brites R, Hipólito J, Pires M, Nunes O. Dyadic coping, marital adjustment and quality of life in couples during pregnancy: an actor-partner approach. J Reprod Infant Psychol. (2019) 38:49–59. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2019.1578950

46. Bodenmann G, Pihet S, Kayser K. The relationship between dyadic coping and marital quality: a 2-year longitudinal study. J Fam Psychol. (2006) 20:485–93. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.485

47. Robert C, Erdt M, Lee J, Cao Y, Naharudin NB, Theng YL. Effectiveness of eHealth nutritional interventions for middle-aged and older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e15649. doi: 10.2196/15649

48. Norton R. Measuring marital quality: a critical look at the dependent variable. J Marriage Fam. (1983) 45:141–51. doi: 10.2307/351302

49. Hou J. The Impact of Marital Stress on Marital Quality: The Role of Risk Factors and Protective Factors [Dissertation]. Beijing: Beijing Normal University (2012).

50. Stas L, Kenny DA, Mayer A, Loeys T. Giving dyadic data analysis away: a user-friendly app for actor-partner interdependence models. Pers Relat. (2018) 25:103–19. doi: 10.1111/pere.12230

51. Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. (2011) 48:1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

52. Kenny DA, Ledermann T. Detecting, measuring, and testing dyadic patterns in the actor-partner interdependence model. J Fam Psychol. (2010) 24:359–66. doi: 10.1037/a0019651

53. Liu C, Wu X. Dyadic patterns in the actor-partner interdependence model and its testing. Psychol Dev Educ. (2017) 1:101–12. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.01.12

54. Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor-partner interdependence model: a model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. Int J Behav Dev. (2005) 29:101–9. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405

55. Olsen JA, Kenny DA. Structural equation modeling with interchangeable dyads. Psychol Methods. (2006) 11:127–41. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.127

56. Won SK, Seol KO. Actor and partner effects of couple's daily stress and dyadic coping on marital satisfaction. J Korean Acad Nurs. (2020) 50:813–21. doi: 10.4040/jkan.20162

57. Yesilot SB. Coping styles and resilience in women living in the same neighborhood with distinct cultures. Int J Intercult. (2021) 84:200–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.08.001

58. Chen M, Rizzi E, Yip P. Divorce trends in China across time and space: an update. Asian Popul. (2020) 17:1–27. doi: 10.1080/17441730.2020.1858571

59. Esmaeili NS, Schoebi D. Research on correlates of marital quality and stability in muslim countries: a review. J Fam Theory Rev. (2017) 9:69–92. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12181

60. Mofasali RH, Jajarmi M, Akbari H. The relationship between social responsibility and marital conflicts in couples with the mediating role of optimistic and self-regulatory. Soc Determinants Health. (2022) 8:1–9. doi: 10.22037/sdh.v8i1.37322

61. Wang Q. The relational self and the Confucian familial ethics. Asian Philos. (2016) 26:1–13. doi: 10.1080/09552367.2016.1200222

62. Kim H. Individuals in family and marriage relations in Confucian context. Korea Rev Int Stud. (2007) 10:67–84. doi: 10.25024/review.2007.10.3.003

63. Ng T. The impact of culture on chinese young people's perceptions of family responsibility in Hong Kong, China. Intellect Discourse. (2019) 27:131–54.

64. Ge X, Li X, Hou Y. Confucian ideal personality traits (Junzi personality): exploration of psychological measurement. Acta Psychol Sin. (2021) 53:1321–34. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.01321

65. Koo E. Women's subordination in confucian culture: shifting breadwinner practices. Asian J Women Stud. (2019) 25:417–36. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2019.1648065

66. Ding W. Destiny and heavenly ordinances: two perspectives on the relationship between heaven and human beings in Confucianism. Front Philos China. (2009) 4:13–37. doi: 10.1007/s11466-009-0002-9

67. Shan C. Marriage law and Confucian ethics in the Qing dynasty. Front Law China. (2013) 8:814–33. doi: 10.3868/s050-002-013-0027-2

68. Tang T, Oatley K. Belief in common fate and psychological well-being among chinese immigrant women. Asian J Soc Psychol. (2009) 12:274–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2009.01293.x

69. Perkins F. The moist criticism of the confucian use of fate. J Chin Philos. (2008) 35:421–36. doi: 10.1163/15406253-03503005

70. Coppens C, Boer S, Koolhaas J. Coping styles and behavioural flexibility: towards underlying mechanisms. Phil Trans R Soc B. (2010) 365:4021–8. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0217

71. Ghadimi M, Latif ABA, Ninggal MT, Amin NFM. A review of the relationship between dispositional coping styles and situational coping strategies. Adv Sci Lett. (2018) 24:4202–5. doi: 10.1166/asl.2018.11571

Keywords: middle-aged and old couples, responsibility thinking, pro-setback thinking, fate thinking, marital quality, the actor-partner interdependence model

Citation: Fan Z, Wu H, Tao M and Chen L (2022) Relationship between Chinese middle-aged and old couples' Confucian coping thinking and marital quality. Front. Public Health 10:956214. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.956214

Received: 30 May 2022; Accepted: 31 August 2022;

Published: 23 September 2022.

Edited by:

María Del Mar Molero Jurado, University of Almeria, SpainReviewed by:

Rebekka Weidmann, University of Basel, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2022 Fan, Wu, Tao and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Chen, Y2hlbmxlaW15QDEyNi5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.