- 1Nursing Informatics, Department of Basic Sciences, Vice Dean for Academic Affairs, Dean of Prince Sultan Bin Abdulaziz College for Emergency Medical Services, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of Health Administration, College of Business Administration, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 3Social Studies Department, College of Arts, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 4Department of Emergency Medical Services (EMS), Prince Sultan College for Emergency Medical Services, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 5Department of Trauma and Accident, Prince Sultan Bin Abdulaziz College for Emergency Medical Services, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 6Department of Emergency Medical Services (EMS), Prince Sultan Bin Abdulaziz College for Emergency Medical Services, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Background and objective: Healthcare professionals have an important role in increasing awareness and protecting populations from natural disasters. This study aimed to assess the perception of healthcare students toward societal vulnerability in the context of population aging.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study conducted among students from two different health colleges over 4 months from February to May 2021. Descriptive analysis was used to assess the perception, and inferential testing was used to assess the various association of knowledge toward societal vulnerability using SPSS.

Results: The majority of respondents were male (69.2%), between 20 and 24 years of age (91.2%), and studying for a nursing degree (76.6%). Only 4.7% had previously completed a previous degree. The mean score of perceptions on the Aging and Disaster Vulnerability Scale among nursing students was 42.5 ± 10.3 (0–65) while for paramedicine 48.1 ± 9.7 (0–65). Similarly, the mean score among male students was 44.1 ±10.5. The mean PADVS total score for the cohort was 43.8 (SD = 10.5). The mean PADVS total score for nursing students was significantly lower than paramedic students (42.5 vs. 48.1; p < 0.001). There was no correlation between PADVS total score and gender, age, area of residence, or previous degree.

Conclusion: Our results indicate that Saudi healthcare students perceive older adults are somewhat vulnerable to disasters with significant differences between nursing and paramedic students. Furthermore, we suggest informing emergency services disaster response planning processes about educational intervention to overcome disasters in Saudi Arabia and other countries.

Introduction

Demographic and epidemiological transitions are defining features of geopolitics in the twenty-first century (1). It is estimated that by 2050, the global population of individuals aged 65 or older will reach 1.5 billion (1). The “oldest old” group, those aged 85 or over, is anticipated to increase by over 350% between 2010 and 2050, compared with an increase of just over 20 % among those aged under 65 (2). The projected growth in those 85 and older has significant implications for healthcare providers as advancing age is associated with chronic multi-morbidities and a range of geriatric syndromes, including frailty, functional decline, and cognitive impairment (2–4). An aging population will challenge paramedic service providers due to increased demand for attendance in community settings, more complex emergency department presentations, and transfers between residential care facilities and hospitals (5, 6). Increasing demand for paramedic services by persons aged over 85 has been identified as a significant workforce issue for the healthcare sector (6).

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is a major economic power in the global economy experiencing accelerated economic and social change and an aging population (7, 8). Older people are recognized as being more vulnerable during and after disasters and suffer greater morbidity and mortality during major disasters. Evidence of the link between increasing extreme weather events and climate change suggests such events are likely to become more frequent, longer-lasting, and more intense in coming years (9, 10). Vicedo-Cabrera et al. found that during the period from 1991 to 2018, 37% of heat-related deaths could be attributed to anthropogenic climate change, and increased mortality was observed on all continents (11). Extreme weather events are predicted to have a greater impact on older community members (12).

Previous study in the USA reported that people aged over 60 comprised 70% of deaths resulting from Hurricane Katrina and almost 50% of deaths were reported among 75 years older. During the emergency and in the aftermath of that disaster, many older people were reportedly abandoned by their carer staff (13). Elsewhere, the research identified that in the wake of a catastrophic natural disaster in Japan many older people's Alzheimer's disease symptoms were exacerbated (14) and New Zealand researchers reported prevalent psychological problems among older adults in the aftermath of major earthquakes in that country (15).

The KSA is placed in the 84th highest position on the 2018 Global Climate Risk Index due to extreme heatwaves, repeated coastal flooding, shortage of freshwater sources, and vegetation cover of < 2% of the total land area (16). The country has experienced several natural and human-induced disasters in recent decades (17–20). Extreme weather events including heatwaves, floods, and dust storms caused considerable mortality, and economic cost, between 1980 and 2010 (17–20). In more recent times Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and COVID-19 have further tested the capacity of health services across the country (19–21).

Emergency service providers are typically integral to a community's disaster response (22, 23). During disasters ambulance, call-outs, hospital transfers, and community mortality typically increase and have a significant impact on emergency service providers, including paramedics (24, 25). Paramedics serve multiple roles during disaster responses including triage, coordination of resources, and transport and evacuation of survivors (26–28). Many disaster victims are older people living in diverse settings and paramedic services typically address the immediate healthcare needs of this demographic (14). In the aftermath of a disaster, paramedics will often be required to manage frail older people with a range of age-related syndromes including functional and cognitive decline (29). Additionally, the ongoing care needs of this population do not subside in the aftermath of disasters and can be exacerbated during such times (30).

When assessing resilience and vulnerability to disasters older community members should be considered a distinct population concerning response and recovery planning. Multiple factors contribute to older adults being more susceptible to injury, illness, or death resulting from disasters (31, 32). Housing inhabited by older people is often constructed from older materials, and residing in such buildings is associated with a higher risk of death during extreme weather events (31, 33). Older people who are reliant on community and allied care services such as domestic support or food provision before a disaster have also been shown to be at higher risk of death (31, 34). People with reduced mobility have limited capacity for evacuation, and the presence of comorbidities also negatively influences health outcomes among older adults during disasters (31, 35). Further, the compromised heat adaptation and thermoregulatory capacity of older adults place them at additional risk in heatwaves (36). Therefore, this study aimed to assess the perception of healthcare students toward societal vulnerability in the context of population aging.

Methods

Design and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted through self-administered questionnaires between February and May 2021. This study involves undergraduate paramedic and nursing students at King Saud University who were taught about disasters, undergo clinical practice experience, or had mass gathering experience in Hajj or Umrah season were eligible to participate. Participation was voluntary, and consent for the use of aggregated data in reporting was inferred by submission of the online survey. Ethics approval for this research was obtained from an institutional Human Research Ethics Committee (KSU-IRB 017E).

Survey tool development

The Perceptions of Aging and Disaster Vulnerability Scale (PADVS) is a tool for evaluating perceptions of vulnerability to disasters in the context of population aging (37). Following an extensive literature review, Annear et al. drafted 13 statements, all of which have been validated in Australia, Japan, and New Zealand settings (37). The Cronbach's α internal consistency reliability was 0.87 for the five subscales of the PADVS (37). The instrument was initially developed to enhance knowledge about the growing population aging and natural disasters in Japan. However, there is a dire need to better understand uses of the instrument in the Saudi Arabian context. Thus, given the potential application of this scale to healthcare students in Saudi Arabia, the instrument was adapted through rigorous forward-backward translation, face validity (38).

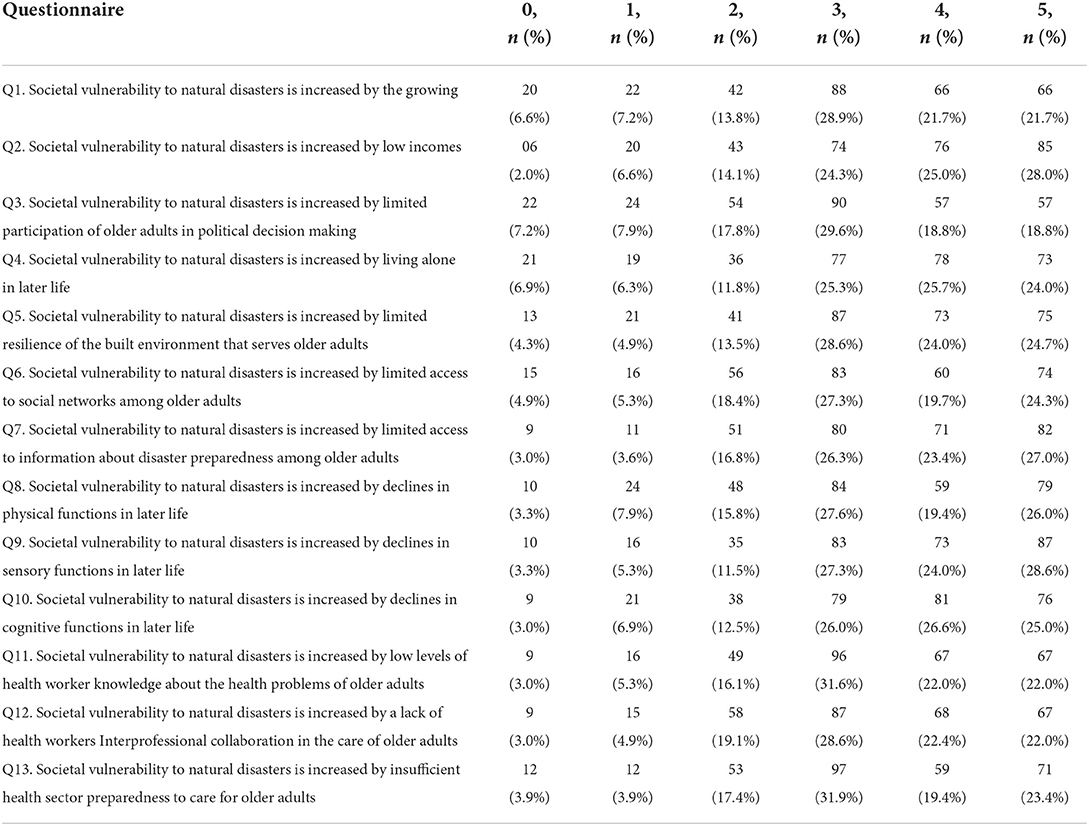

The data collection was carried out through google forms using online questionnaires, for the purpose of data collection, a researcher was appointed. The data collection was carried out using simple random sampling technique. The PADVS comprises 13 items, which are each scored from 0 to 5, based on respondents' perceptions of age-related societal vulnerability. An exemplar statement from the measure (item 1) reads as follows: “Societal vulnerability to natural disasters is increased by the growing number of older adults in the community.” Respondents scored each of the 13 statements from “0” (no increase in vulnerability) to “5” (very high increase in vulnerability). Within the 13-item measure are four validated subscales, which reflect different issues associated with age-related and societal vulnerability to disasters: (1) Isolation and access (4 items scored out of 20), (2) declining function (3 items scored out of 15), (3) community inclusiveness (3 items scored out of 15), and (4) health system and health worker readiness (3 items scored out of 15). Higher scores on the PADVS and each subscale indicate more significant concerns among respondents regarding societal vulnerability.

Data analysis

All data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Mac (version 27). Continuous data were screened for outliers, and participants with standardized scores >3 or < -3 were excluded from further analysis. Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic characteristics, PADVS total score, and subscales scores. Correlations between PADVS total score and age, gender, prior education, and current degree were examined using the Pearson correlation or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Research participants

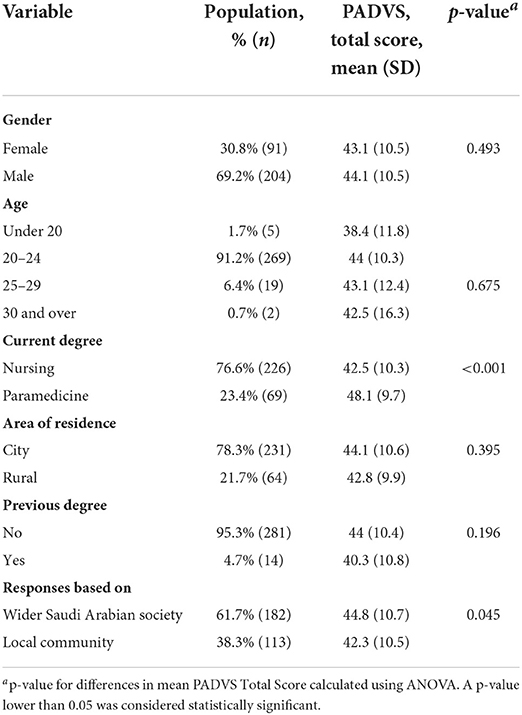

Of the 300 survey respondents, 295 were included in the analysis (Table 1). The majority of respondents were male (69.2%), between 20 and 24 years of age (91.2%), and studying for a nursing degree (76.6%). Only 4.7% had previously completed a previous degree. The mean score of perceptions on the Aging and Disaster Vulnerability Scale among nursing students was 42.5 ± 10.3, while for paramedicine 48.1± 9.7. Similarly, the mean score among male students was 44.1 ±10.5.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants according to perceptions of aging and disaster vulnerability score.

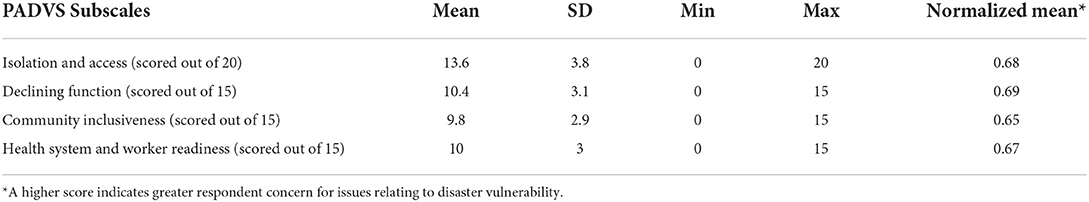

Table 2 detailed the student's frequency of perceptions of disaster vulnerability scale. The mean PADVS total score for the cohort was 43.8 (SD=10.5). The mean PADVS total score for nursing students was significantly lower than paramedic students (42.5 vs. 48.1; p < 0.001). There was no correlation between PADVS total score and gender, age, area of residence, or previous degree. Participants basing their responses on the wider Saudi Arabian society had a significantly higher PADVS total score than those considering their local community (44.8 vs. 42.3; p = 0.045). Respondents showed similar levels of concern across all four PADVS subscales (Table 3).

Table 3. Absolute and comparative scores on 4 PADVS subscales addressing issues associated with age-related and societal vulnerability to disasters.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Saudi Arabia that has investigated the Societal vulnerability in the context of population aging given the perceptions of healthcare students' in Saudi Arabia. Although not much literature was identified nationally about the perceptions of Societal vulnerability concerning aging. However, most of the literature reported internationally on the context of vulnerability of aging (37, 39). This study would make a substantial contribution to protecting populations from natural disasters, especially concerning the effects of climate change in Saudi Arabia, and would serve as a reference for future studies that are desperately needed.

In this study, the mean PADVS total score among Saudi healthcare students was 43.8, which is slightly inconsistent with previous studies conducted in other countries (37, 39). For instance, an earlier study conducted among Australian healthcare students reported a total score of perceptions was 45.39 (range 0–65). The difference in the findings might be due to the differences in the study site, population, and weather of the country or country profile where the participants live. Furthermore, it is evidenced that islands occupied by oceans, the possibilities of frequent innocence of natural disasters (37, 39). This might be the reason for a higher understanding of disasters and their consequences in previous studies, where earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons are common, compared to an arid country like Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, in the current study, the mean overall score for the isolation and access, declining function, community inclusiveness, and health system and worker readiness was 13.6 ± 3.8, 10.4 ± 3.1, 9.8 ± 2.9, 10 ± 3. While the mean score for the domains of isolation and access, the declining function was reported poorly in comparison to a previous study by Lucas et al. in 2019, who reported 14.28 ± 3.70, 12.58 ± 2.48 (51). However, the community inclusiveness and the domain of health system worker readiness scores in this study are better than the previous study conducted by Lucas et al. in 2019 (39). This indicates that this topic should be given more attention in Saudi healthcare education programs, and other international levels, as community resilience to disaster is dependent on active engagement and awareness (39, 40). Furthermore, our research reveals a lack of awareness regarding disaster vulnerability in the context of an aging population in Saudi Arabia.

In this study, the perception score was high among paramedical students [48.1 (9.7)] compared to nursing students [42.5 (10.3)]. However, evidence was shown that paramedics are well-trained to address the health problems faced by older adults during and after a natural disaster. In the typically chaotic aftermath of a big disaster, health and social care workers must be able to function successfully in times of social and environmental disturbance (39). Similarly, the perception scores were significantly different between students belonging to Wider Saudi Arabian society and the local community. In Saudi Arabia, where a significant number of older people live in holy cities (41) and the risk of tropical diseases and fire, is exacerbated as a result of annual pilgrimages visits to holy cities and also due to extreme weather events, the vulnerability of older adults is also likely to increase (42). Furthermore, in Saudi Arabia, increased temperatures in the Summer may increase the risks of heat-related mortalities.

Limitations

The current study has some limitations, first, the research involved students from one campus of a large public university in the capital of Saudi Arabia. Consequently, results may not be more broadly generalizable at this stage and or not-representative of others, as well as being not generalizable globally. However, the distribution in the data and a diversity of perspectives among the sample suggest that the findings may be replicated with larger random samples. Second, the results were based on a self-completed questionnaire, which may have increased the possibility of biases such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

Recommendation

The findings of this study recommend that disaster vulnerability be established a central part of geriatric education for aspiring healthcare students particularly paramedics and nurses. In order to inform future initiatives aimed at increasing awareness of societal vulnerability to disaster in the context of an aging population, we urge that outcomes of any such educational programs be extensively examined.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that Saudi healthcare students perceive older adults are somewhat more vulnerable to disasters with significant differences between nursing and paramedic students. Our findings suggest that current healthcare professional education does not adequately prepare students to overcome the natural disasters, which are expected to become more frequent and extreme as the Geological era progresses. Furthermore, it is advisable to inform emergency services about disaster response planning processes and educational intervention.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval for this research was obtained from an institutional Human Research Ethics Committee, King Saud University No. KSU-IRB 017E. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, investigation, supervision, and project administration: OS, MAb, MAlj, and AA-W. Methodology, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation: AAlo, NA, MAlh, and AAlg. Software: OS and NA. All authors reviewed the manuscript, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

MA received a fund from the Researcher Supporting Project number (RSP2022R481), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, to support the publication of this article. The funding agency had no role in designing the study, conducting the analysis, interpreting the data or writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their appreciation to King Saud University for funding this work through the Researcher Supporting Project (RSP2022R481), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Omran A. The epidemiologic transition: a theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Quart. (2005) 83:731–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00398.x

2. Arendts G, Lowthian J. Demography is destiny: an agenda for geriatric emergency medicine in Australasia. Emerg Med Austral. (2013) 25:271–8. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12073

3. Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. (2006) 366:2112–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0

4. Lowthian J, Jolley D, Curtis A, Currell A, Cameron P, Stoelwinder J, et al. The challenges of population ageing: accelerating demand for emergency ambulance services by older patients, 1995–2015. Med J Australia. (2011) 194:574. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03107.x

5. Chilton M. A brief analysis of trends in prehospital care services and a vision for the future. Austral J Paramed. (2004) 2:5. doi: 10.33151/ajp.2.1.252

6. Lowthian J, Curtis A, Stoelwinder J, McNeil J, Cameron P. Emergency demand and repeat attendances by older patients. Intern Med J. (2013) 43:554–60. doi: 10.1111/imj.12061

7. Salam A, Mouselhy M. Ageing in Saudi Arabia: impact of demographic transition. BOLD. (2013) 24:33–46.

8. Hussein S, Ismail M. Ageing and elderly care in the Arab region: policy challenges and opportunities. Ageing Int. (2017) 42:274–89. doi: 10.1007/s12126-016-9244-8

9. Meehl GA, Tebaldi C. More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science. (2004) 305:994–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704

10. Kovats RS, Hajat S. Heat stress and public health: a critical review. Annu Rev Public Health. (2008) 29:41–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090843

11. Vicedo-Cabrera AM, Scovronick N, Sera F, Royé D, Schneider R, Tobias A, et al. The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nat Clim Change. (2021) 11:492–500. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-01058-x

12. Aldrich N, Benson WF. Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults. Prev Chronic Dis. (2008) 5:A27. Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jan/07_0135.htm

13. The White House. The Federal Response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons Learned. Washington, DC (2006). Available online at: http://library.stmarytx.edu/acadlib/edocs/katrinawh.pdf (accessed July, 2022).

14. Furukawa K, Ootsuki M, Nitta A, Okinaga S, Kodama M, Arai H. Aggravation of Alzheimer's disease symptoms after the earthquake in Japan: a comparative analysis of subcategories. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2013) 13:1081–2. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12085

15. Annear M, Wilkinson T, Keeling S. Psychological challenges among older adults following the Christchurch earthquakes. J Disaster Res. (2013) 8:508–11. doi: 10.20965/jdr.2013.p0508

16. Alyami A, Dulong CL, Younis MZ, Mansoor S. Disaster preparedness in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: exploring and evaluating the policy, legislative organisational arrangements particularly during the Hajj period. Eur J Environ Public Health. (2020) 5:em0053. doi: 10.29333/ejeph/8424

17. Alsalem MM, Alghanim SA. An assessment of Saudi hospitals' disaster preparedness. Eur J Environ Public Health. (2021) 5:em0071. doi: 10.21601/ejeph/9663

18. Shalhoub AAB, Khan AA, Alaska YA. Evaluation of disaster preparedness for mass casualty incidents in private hospitals in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. (2017) 38:302. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.3.17483

19. Alraga S. An investigation into disaster health management in Saudi Arabia. J Hosp Med Manage. (2017) 3:18. doi: 10.4172/2471-9781.100037

20. Otto IM, Reckien D, Reyer CP, Marcus R, Le Masson V, Jones L, et al. Social vulnerability to climate change: a review of concepts and evidence. Reg Environ Change. (2017) 17:1651–62. doi: 10.1007/s10113-017-1105-9

21. Bissell RA, Becker BM, Burkle FM Jr. Health care personnel in disaster response. Emerg Med Clin. (1996) 14:267–88. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70251-0

22. Chaffee M. Willingness of health care personnel to work in a disaster: an integrative review of the literature. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. (2013) 3:42–56. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e31818e8934

23. Hughes L, Hanna E, Fenwick J. The Silent Killer: Climate Change and the Health Impacts of Extreme Heat. The Climate Council of Australia (2016).

24. Nitschke M, Tucker GR, Hansen AL, Williams S, Zhang Y, Bi P. Impact of two recent extreme heat episodes on morbidity and mortality in Adelaide, South Australia: a case-series analysis. Environ Health. (2011) 10:42. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-42

25. Kahn CA, Schultz CH, Miller KT, Anderson CL. Does START triage work? An outcomes assessment after a disaster. Ann Emerg Med. (2009) 54:424–30.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.12.035

26. Lerner EB, Schwartz RB, Coule PL, Weinstein ES, Cone DC, Hunt RC, et al. Mass casualty triage: an evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. (2013) 2:S25–34. doi: 10.1097/DMP.0b013e318182194e

27. Kilner T. Triage decisions of prehospital emergency health care providers, using a multiple casualty scenario paper exercise. Emerg Med J. (2002) 19:348–53. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.4.348

28. Gamble JL, Hurley BJ, Schultz PA, Jaglom WS, Krishnan N, Harris M. Climate change and older Americans: state of the science. Environ Health Perspect. (2013) 121:15–22. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205223

29. Fernandez LS, Byard D, Lin C-C, Benson S, Barbera JA. Frail elderly as disaster victims: emergency management strategies. Prehosp Disaster Med. (2012) 17:67–74. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00000200

30. Vandentorren S, Bretin P, Zeghnoun A, Mandereau-Bruno L, Croisier A, Cochet C, et al. August 2003 heat wave in France: risk factors for death of elderly people living at home. Eur J Public Health. (2006) 16:583–91. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl063

31. Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, Blackstock J, Byass P, Cai W, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet. (2015) 386:1861–914. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6

32. Bright F, Gilbert JD, Winskog C, Byard R. Inadequate domestic insulation in australia - an additional risk factor for lethal hypothermia. Pathology. (2013) 45:S90. doi: 10.1097/01.PAT.0000426967.80938.31

33. Dirkzwager AJ, Grievink L, Van der Velden PG, Yzermans CJ. Risk factors for psychological and physical health problems after a man-made disaster. Br J Psychiatry. (2006) 189:144–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017855

34. Cutter SL, Emrich CT, Webb JJ, Morath D. Social vulnerability to climate variability hazards: a review of the literature. Final Rep Oxfam Am. (2009) 5:1–44.

35. Coates L, Haynes K, O'Brien J, McAneney J, de Oliveira FD. Exploring 167 years of vulnerability: an examination of extreme heat events in Australia 1844–2010. Environ Sci Policy. (2014) 42:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2014.05.003

36. Nofal A, Alfayyad I, Khan A, Al Aseri Z, Abu-Shaheen A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of emergency department staff towards disaster and emergency preparedness at tertiary health care hospital in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. (2018) 39:1123. doi: 10.15537/smj.2018.11.23026

37. Annear MJ, Otani J, Gao X, Keeling S. Japanese perceptions of societal vulnerability to disasters during population ageing: constitution of a new scale and initial findings. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. (2016) 18:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.06.001

38. Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK. Instrument translation process: a methods review. J Adv Nurs. (2004) 48:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x

39. Lucas P, Annear M, Harris W, Eyles H, Rotheram A. Health care student perceptions of societal vulnerability to disasters in the context of population aging. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness. (2019) 13:449–55. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.65

40. Bergstrand K, Mayer B, Brumback B, Zhang Y. Assessing the relationship between social vulnerability and community resilience to hazards. Soc Indic Res. (2015) 122:391. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0698-3

41. ARAB, NEWS,. Number of elderly people in ksa rises — as do the burdens on their caregivers. Available online at https://www.arabnews.com/node/1318831/offbeat (accessed May 17, 2022).

Keywords: disaster, aging, healthcare students, societal vulnerability, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Samarkandi OA, Aljuaid M, Abdulrahman Alkohaiz M, Al-Wathinani AM, Alobaid AM, Alghamdi AA, Alhallaf MA and Albaqami NA (2022) Societal vulnerability in the context of population aging—Perceptions of healthcare students' in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 10:955754. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.955754

Received: 29 May 2022; Accepted: 09 August 2022;

Published: 27 September 2022.

Edited by:

Russell Kabir, Anglia Ruskin University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Atta Al-Sarray, Middle Technical University, IraqMondira Bardhan, Khulna University, Bangladesh

Copyright © 2022 Samarkandi, Aljuaid, Abdulrahman Alkohaiz, Al-Wathinani, Alobaid, Alghamdi, Alhallaf and Albaqami. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Osama A. Samarkandi, b3NhbWFzYW1hcmtoYW5kaTIyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Osama A. Samarkandi1*

Osama A. Samarkandi1* Mohammed Aljuaid

Mohammed Aljuaid Abdullah A. Alghamdi

Abdullah A. Alghamdi