95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 04 August 2022

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.951717

Objective: To explore whether biological rhythm disturbance mediates the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms and to investigate whether ego resilience moderates the mediation model.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out using an online self-report questionnaire distributed to college students from September 2021 to October 2021. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Perceived Stress Severity (PSS-10), the Biological Rhythms Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (BRIAN), and Ego Resilience (ER-96) were used for investigation. SPSS 23 was used for data analyses. The significance of mediation was determined by the PROCESS macro using a bootstrap approach.

Results: Among the participants, 9.2% (N = 1,282) exhibited significant symptoms of depression. Perceived stress was positively associated with depressive symptoms, and biorhythm partially mediated this relationship. The direct and indirect effects were both moderated by ego resilience. Perceived stress had a greater impact on depressive symptoms and biorhythm for college students with lower ego resilience, and the impact of biorhythm on depressive symptoms was also stronger for those with lower ego resilience. Perceived stress had an impact on depressive symptoms directly and indirectly via the mediation of biorhythm.

Conclusion: Schools and educators should guide college students to identify stress correctly and provide effective suggestions to deal with it. Meanwhile, maintaining a stable biorhythm can protect college students from developing depressive symptoms. Students with low resilience should be given more attention and assistance.

Depression is characterized by persistent pessimism and lack of interest or pleasure and is considered one of the most frequent mental disorders among college students (1). Several cross-sectional studies reported that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese college students ranged from 12.2 to 28.9% (2–4). The college years are distinct periods of development straddling the adolescent and young adulthood stage, as well as one of the common times for the onset of depression (5, 6). Since depression at an early age has negative consequences in long-term life (7), the current situation and factors related to depressive symptoms among college students are worth exploring.

Depression is generally considered a stress-related disorder. Statistically, nearly 70% of primary depression is caused by stress (8). Stress perception refers to a person's appraisal of the intensity of threat from stressors. Severe life stressors impact the risk of depression (9, 10). College students are confronted with considerable stress, including environmental changes, academic requirements, higher education programs and the transition to independence (11), and are therefore a vulnerable group in need of attention. A 1-year follow-up among college students found that stressful experiences are one of the strongest predictors of depression (12), but how perceived stress exerts its effects on depressive symptoms remains unclear. Some studies have reported that college students with higher perceived stress suffer from more serious sleeping problems (13, 14) and report lower physical activity and longer sedentary time (15). Additionally, perceived stress was generally accompanied by dietary behavior changes (16).

Biorhythm refers to the cyclical changes of various functional activities of an individual to maintain the homeostasis of the internal environment and adapt to the changes of the external environment. Sleeping, daily activities, eating patterns and social interactions are uniformly defined as behavioral markers of biorhythm, which often present with abnormalities in depressive individuals (17, 18). A meta-analysis indicated an association between biorhythm orientation and more severe depressive symptoms (19). At present, the most commonly evaluated is chronotype, the diurnal preference for the sleep-wake circle and daily activity, which lies on a continuum between morningness and eveningness (20). Surveys on college students found higher depressive symptom severity in non-morning chronotypes and moderate/severe perceived stress groups (21–25). Weight, appetite changes and loss of energy are also extremely common in adolescents with depressive symptoms in addition to changes in sleep and activity levels (26), but there is a lack of a multidimensional evaluation of their associated biorhythms. In this study, we will comprehensively evaluate the biorhythm of college students through a scale specially designed to evaluate biorhythm, and explore the role in depressive symptoms. Since college students have not yet established a stable life structure, comprehensively characterizing the biorhythm among college students will help in understanding the effects of biorhythm disturbance on depression and provide reliable evidence for preventive interventions. It is recognized that the stress response causes neurohumoral turbulence in the regulation of the biorhythm and further leads to mental disorders (27). Therefore, we hypothesized that biorhythm disturbances might play a mediating role in the progression of perceived stress into depressive symptoms. Liu et al. identified the mediating role of insomnia in perceived stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students (28), but other aspects concerning biorhythm changes were not discussed. A more comprehensive investigation of biorhythm and its potential mediating role in the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms among college students deserves further exploration.

Resilience is the adjustment and adaptive ability of an individual to changes in the external environment in psychology and behavior (29). As a relatively stable psychological trait, resilience varies among individuals, serving as a vital protective factor in psychological health (30, 31). High resilience can protect college students from depressive symptoms (32). Moreover, resilience plays an important role in the regulation of stress (33, 34). Physiologically, high resilience can alleviate neurohormonal changes in the body and have a positive impact on biorhythm stability (35). Therefore, we conjectured that high ego resilience attenuated the effects of perceived stress on depressive symptoms and further explored the moderating effect of resilience on the mediation model.

In summary, this study aimed to explore the interrelationships among perceived stress, biorhythm, ego resilience and depressive symptoms and to test the hypothetical moderated mediation model (Figure 1), hoping to provide a reference for targeted interventions to improve the psychological health of college students.

An online investigation with convenience sampling was conducted from September 2021 to October 2021. Our questionnaires were in the local language and all scales are Chinese versions translated by previous scholars. The inclusion criteria of participants were college students in China. Data were collected via the Wenjuanxing platform (https://www.wjx.cn/vj/hP4DYhi.aspx). Basic questions are set in the questionnaire to ensure that the questionnaires submitted normally are from college students. Missing any questions will fail to submit the questionnaire properly. In data preprocessing, we also manually excluded some obviously sloppy answers (i.e., the age is obviously beyond the range of normal college students, the IP address is from the same person, and too little time to answer questions, which suggested that the questionnaire was completed casually). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University. All participants were informed with online consent. In total, 15,879 questionnaires were received, and a final sample of 13,943 (effective response rate: 87.81%) was analyzed after the elimination of the unqualified.

Information concerning age, gender, and grade was collected to recognize the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Stress levels were measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which contains 10 items rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) (36). Participants reported the degree to which situations in one's life have been unpredictable, uncontrollable and overloaded over the last month, and higher scores represent higher stress perception. The total score ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. In this study, Cronbach's α of the scale is 0.883.

Biorhythm was assessed by the Biological Rhythms Interview of Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (BRIAN), a screening measure assessing the biorhythm of activity, sleeping, eating and socializing (37). Each item is scored from 1 to 5, with a total score ranging from 18 to 90, and higher scores suggest more disturbed biorhythms. Cronbach's α of the entire scale is 0.936 in the current study.

Ego resiliency was measured by the ego-resiliency scale (ER-96), which consists of 14 items (29). Questions solicited responses on a scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (applies very strongly), and higher scores represent stronger ego resilience. In the current study, Cronbach's α of the scale was 0.909.

Depressive symptoms were measured by PHQ-9, a brief self-administered instrument, and scores each of the items as “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day) (38). The most common scoring criteria are 0–4: no depression, 5–9: probably mildly depression, 10–14: probably moderately depression, 15–19: probably moderately severe depression, and 20–27: probably severely depression. A cutoff score of 10 or higher is generally accepted as a current depressive episode, which was consistent with moderate and severe severity of depression (39). Cronbach's α of the entire scale was 0.943 in the current study.

SPSS 23 for Windows was applied for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation were used for quantitative variables, while the constituent ratio for categorical variables) were used to describe the participants' demographic characteristics and the main study variables (perceived stress, biorhythm, ego resilience and depressive symptoms). One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and t-tests were used to make a statistical comparison. Pearson's rho correlations were computed to examine the association between the variables.

To test our hypothesis concerning the direct and indirect effects of perceived stress on depressive symptoms, the following conditions are required: The independent variable predicts the mediator variable and the dependent variable and the mediator variable predicts the dependent variable; after the addition of mediating variable, the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable turns into weaker (partial mediation) or non-significant (full mediation). We used serial multiple mediator models with the PROCESS macro for SPSS described by Hayes (40), which can provide the significance of the regression coefficients for each path, and estimate the size of the mediation effects. Model 4 was performed to identify the mediating effects. We performed 5,000 bootstrap resamples to determine the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect of perceived stress on depressive symptoms. After confirming the mediation effect of biorhythm was significant, model 59, a moderated mediation model, was used to estimate the moderating role of ego resilience. There is a significant mediating effect if the 95% CI excludes 0. The significance level is set at 0.05 for all tests.

The Harman single-factor test was used to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the data since we used online self-reports. The results showed that there were seven factors with eigenvalues >1, and the variance explained by the first factor was 27.27%, less than the critical standard of 40%. In summary, there was no significant common method deviation in this study.

Among the eligible samples in this study, 5,057 (36.3%) were male and 8,886 (63.7%) were female. The mean age of the sample was 19.14 (SD = 1.22). As for the severity of depressive symptoms, 9,555 (68.5%) students were normal, 3,106 (22.3%) presented mild depressive symptoms, 788 (5.7%) presented moderate depressive symptoms, 335 (2.4%) presented moderately severe symptoms, 159 (1.1%) presented severe depressive symptoms. In total, the detection rate of depression was 9.2% (n = 1,282) at a threshold of 10, which included moderate and severe severity of depressive symptoms.

Female reported significantly higher scores for perceived stress (male = 13.61 ± 7.99, female = 14.98 ± 6.24, p < 0.001), ego resilience (men = 39.25 ± 11.16, women = 39.81 ± 8.05, p < 0.001) and depressive symptoms (male = 3.44 ± 4.75, female = 3.78 ± 4.50, p < 0.001), while there was no significant difference in biorhythm (p = 0.99) between genders.

In addition, age was positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.28, p = 0.01) and biorhythm (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with resilience (r = 0.049, p < 0.001). Age was not statistically related to perceived stress (p = 0.234).

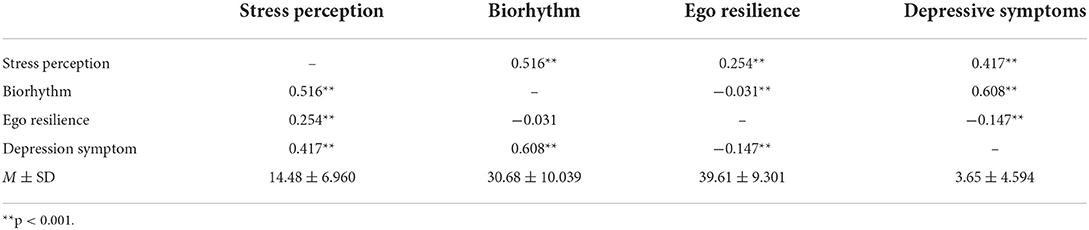

The Pearson's correlations for stress perception, biorhythm and depressive symptoms are presented in Table 1. The results showed that depressive symptoms had a positive correlation with perceived stress (r = 0.417, p < 0.001) and biorhythm (r = 0.608, p < 0.001). Perceived stress was also positively correlated with biorhythm (r = 0.516, p < 0.001).

Table 1. Correlations (r) between perceived stress, biorhythm, ego resilience and depressive symptoms (n = 13,943).

The results of the bootstrapping methods showed that the direct, indirect and total effects in the mediation model were significant after controlling for age and gender (Table 2). Perceived stress was positively associated with depression (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Perceived stress was significantly positively associated with biorhythm (β = 0.75, p < 0.001). When putting perceived stress and biorhythm into the regression equation, both perceived stress (β = 0.09, p < 0.001) and biorhythm (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) were significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms in college students. The bootstrap confidence interval of the mediation effect did not include 0 as was shown in Table 3, showing that biorhythm had a significant mediating effect between perceived stress and depressive symptoms, and the mediating effect accounted for 66.7% of the total effects. Figure 2 illustrates the mediation model, along with the standardized path coefficients.

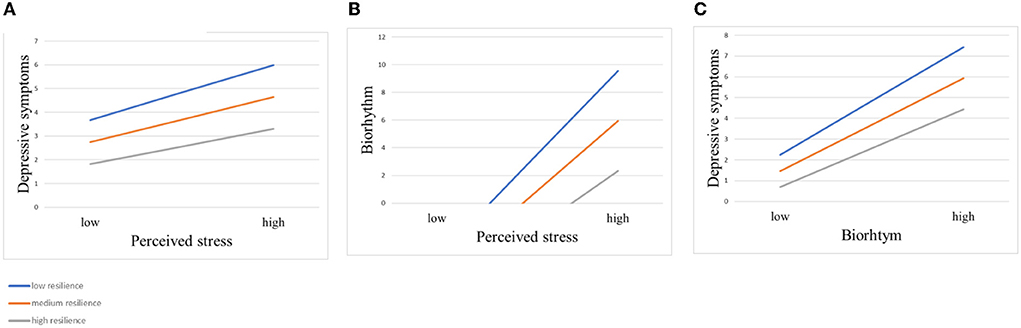

Table 4 shows the results of the moderating mediation. First, resilience directly moderates the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. When ego resilience was low (−1 SD), perceived stress had a greater impact on depressive symptoms (effect = 0.166, p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval [0.152, 0.180]. When the individual's ego resilience was high (+1 SD), perceived stress had little effect on depressive symptoms (effect = 0.107, p < 0.001), and the 95% confidence interval was [0.095, 0.120]. In addition, ego resilience moderated both the anterior and posterior pathways of the mediation effects. The effects of perceived stress on biorhythm and biorhythm on depressive symptoms were greater when resilience was lower. To analyze the moderating effect of resilience more intuitively, the participants were divided into a high group (those whose resilience score was one standard deviation higher than the mean), a middle group (those whose resilience score was equal to the mean) and a low group (those whose resilience score was one standard deviation lower than the mean). The moderating effect charts were drawn stratified by resilience score group. Figure 3 shows that in the low resilience group, biorhythm scores and depressive symptoms scores increased rapidly with an increase in perceived stress scores. However, in the high resilience group, the increasing slope of the biorhythm score and depressive symptom score was relatively gentle.

Figure 3. Moderating effects of different levels of resilience on the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. (A) Moderating effect of different levels of resilience on perceived stress and depressive symptoms. (B) Moderating effect of different levels of resilience on perceived stress and biorhythm. (C) Moderating effect of different levels of resilience on biorhythm and depressive symptoms.

These results suggest a positive association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms, which was mediated by biorhythm. In addition, resilience moderated the direct and indirect effects of the mediation model, serving as an internal resource in college students' ability to deal with perceived stress and reducing their risk of developing depressive symptoms.

In the present study, the proportion of college students who were suffering from depressive symptoms was 9.2%, which was lower than that of other studies among Chinese college students (2–4). Regional differences, periods, and varied measurements may explain some discrepancies among studies. Most of our samples came from Sichuan Province, and the investigation period was during the normal period of Corona Virus Disease 2019, therefore the stress perception intensity may generally be lower than that during the outbreak period. In addition, there are differences in sensitivity and specificity for depressive symptoms in different self-rating scales of depressive symptoms. Female students reported higher stress perception and more severe depressive symptoms, which is consistent with previous studies (41–43). Men possess greater reactivity to the environment and better-coping abilities (44). Interestingly, female students were more resilient than men despite showing more severe depressive symptoms. The reason may be that resilience has different moderating abilities to different stressors and cannot buffer the effect against some stressors, such as the physical and emotional neglect experienced by women (45). Future studies can further identify gender differences in the response to different types of stress to clarify the regulatory mechanism.

Our study also found that younger college students displayed more severe depressive symptoms. Younger college students are more likely to be freshmen, who are at increased risk of self-reported severe depression (42), although they have the lightest class load compared to students in other grades. Sudden environmental changes from relatively regular high school life to the unfamiliar college life may be the explanation, since secondary school life is dominated by specific lectures, while college life requires more self-management to meet academic requirements and more diversified social skills. With the advances in age and social experience, coping strategies for different kinds of stressful events and emotion regulation abilities are improved.

Along with previous findings, the present study revealed a positive association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. The stress response is divergent in college students. Contributing factors consist of the nature of the events, behavioral and genetic factors, previous experience and personal resources. Severe stress perception leads to a range of emotional responses when individuals feel inadequate to cope with challenges. Chronic stress increases the severity of depressive symptoms (6, 46). Stress also induces serotonin alterations, which disrupts mood regulation and serves as critical pathogenesis of depression (47). Moreover, psychological stress could suppress the immune system (48), leading to changes in immune cytokine levels that may generate depressive symptoms (49).

Our findings corroborate our hypothesis that biorhythm may be a mediator in the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms. When stress is perceived, the human body needs to maintain relative homeostasis through a series of physiological and biochemical reactions (50). The stress response plays a causal role in depression onset, perhaps via neurobiological hyperactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) (51, 52). Typical responses to acute stress, such as immediate threats to physiological homeostasis, activate the SNS, with the release of catecholamines, contributing to the biorhythm (53, 54). Alternatively, activation of the HPA axis is crucial in the response to psychological stress and dysfunction of the HPA axis plays a crucial role in the development of depression (55). Normally, hormones controlled by the HPA axis fluctuate regularly throughout the day and display biorhythm involving sleeping, digestion, and activity (56).

First, sleep disturbance is a defining feature of depression, presenting as difficulty in sleep onset, mid-nocturnal, and early morning insomnia symptoms (57). It is considered not only a common finding of depression but also a significant predictor of the onset of depression (58, 59). Sleep disturbance disrupts stability and regulation (60) and hence may play a role in the pathophysiology of depressive symptoms.

Second, low activity levels are associated with subsequent depressive symptoms (61, 62). Patients with depression perform less physical activity (17, 63). A large-scale genome-wide association study (GWAS) also verified the predictive effect of physical activity on depression (64). Furthermore, stress alters ghrelin levels, which are involved in the regulation of appetite and digestion (65). Diet-induced changes in the gastrointestinal microbiome can affect mood and behavior by altering the gut microbiome (66). Weight change in depressed people may be a result of an increase or decrease in appetite (67).

Social function, defined as the ability to perform regular social roles, is considered a nonnegligible sign of depression (68). Social deficits are also manifestations of a state of depression (69). The interpersonal difficulties might be a result of reduced motivation (70). Depressed subjects rated life stimuli as more negative and arousing, which is associated with reduced social and emotional competence (71). In summary, our results demonstrated the important roles of these aspects involved in biorhythm changes in the development of depressive symptoms.

Our results revealed that ego resilience may function as a moderator between perceived stress and depressive symptoms separately, as well as in the direct and indirect effects. Resilience not only moderates the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms but also the association between perceived stress and biorhythm, as well as the relationship between biorhythm and depressive symptoms. Specifically, compared to high ego resilience individuals, the direct and indirect effects of perceived stress on depressive symptoms are greater in individuals with low ego resilience. That is, resilience can mitigate the negative effects of perceived stress. As an important psychological trait, resilience serves as a restorative factor to resist negative stimuli and adverse situations. The reason may be that people with high ego resilience usually have more social support and more positive emotional regulation (72, 73) and hence can stabilize their biorhythm and show milder depressive symptoms. The upper limit of stress tolerance of resilience may affect the risk of depression in college students under stress: strong resilience can help individuals adapt well, while poor resilience leads to failure to properly handle stress. College students with lower ego resilience should be taken more seriously when they perceive stress.

Our findings suggest that biorhythm is a critical mediator in the development of depressive symptoms, providing reasonable suggestions for reducing the incidence of depression among college students from the perspective of biorhythm regulation and coping strategies when reacting to stressors. Proper campus life arrangements, such as providing sports activities, social activities, regular daily schedules and the popularization of mental health knowledge, can help alleviate the consequences of severe stress perception.

Perceived stress has an impact on depressive symptoms directly and indirectly via the mediation of biorhythm. Ego resilience moderates the association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms, as well as the relationships between perceived stress and biorhythm and between biorhythm and depressive symptoms.

Schools and educators should guide college students to identify stress correctly and provide effective suggestions to deal with it. Meanwhile, maintaining a stable biorhythm can protect college students from developing depression when perceiving stress, thus achieving the goal of reducing depressive symptoms. Students with low resilience should be given more attention and assistance.

There are some limitations to this study as this is an online study. First, our results found a higher proportion of females and a higher detection rate of depressive symptoms in females, thus possibly overestimating the detection rate of depressive symptoms in the entire college population. Future studies can use more theoretical sampling methods to investigate the prevalence of depressive symptoms among college students. Second, we adopted a self-report survey method, so there may be recall bias. Third, the psychological impact of major public health events on the population cannot be excluded. In addition, causal inference cannot be established from this cross-sectional study, and a large-scale prospective study is needed to further assess the critical role of biorhythm in depressive symptoms.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YMa and CQ: conceptualization. YMa and BZ: methodology. YMa: software and formal analysis and writing—original draft preparation. YMa, YMeng, YC, and YMao: investigation. YMa, CQ, BZ, YMeng, and YC: writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was funded by the Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan provincial government (Grant No. 2022YFS0345).

First of all, we wish to thank the respondents for participating in the study. We are also grateful for the support from the Department of Science and Technology of the Sichuan provincial government.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Boehm MA, Lei QM, Lloyd RM, Prichard JR. Depression, anxiety, and tobacco use: Overlapping impediments to sleep in a national sample of college students. J Am Coll Health. (2016) 64:565–74. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2016.1205073

2. Wang Z-H, Yang H-L, Yang Y-Q, Liu D, Li Z-H, Zhang X-R, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: a large cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 275:188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.034

3. Li L, Lok GKI, Mei SL, Cui XL, An FR, Li L, et al. Prevalence of depression and its relationship with quality of life among university students in Macau, Hong Kong and mainland China. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:15798. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72458-w

4. Cheung DK, Tam DKY, Tsang MH, Zhang DLW, Lit DSW. Depression, anxiety and stress in different subgroups of first-year university students from 4-year cohort data. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.041

5. Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. (2016) 46:2955–70. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001665

6. Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, et al. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. (2018) 127:623–38. doi: 10.1037/abn0000362

7. Whitton SW, Whisman MA. Relationship satisfaction instability and depression. J Fam Psychol. (2010) 24:791–4. doi: 10.1037/a0021734

8. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. (2005) 1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938

9. Kendler KS, Gardner CO. Depressive vulnerability, stressful life events and episode onset of major depression: a longitudinal model. Psychol Med. (2016) 46:1865–74. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000349

10. Tao M, Li Y, Xie D, Wang Z, Qiu J, Wu W, et al. Examining the relationship between lifetime stressful life events and the onset of major depression in Chinese women. J Affect Disord. (2011) 135:95–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.054

11. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2016) 316:2214–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324

12. Ebert DD, Buntrock C, Mortier P, Auerbach R, Weisel KK, Kessler RC, et al. Prediction of major depressive disorder onset in college students. Depress Anxiety. (2019) 36:294–304. doi: 10.1002/da.22867

13. Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD, Grieser EA, Tatum JI, Roane BM. Epidemiology of insomnia in college students: relationship with mental health, quality of life, and substance use difficulties. Behav Ther. (2013) 44:339–48. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.12.001

14. Zhai X, Wu N, Koriyama S, Wang C, Shi M, Huang T, et al. Mediating effect of perceived stress on the association between physical activity and sleep quality among Chinese college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:289. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010289

15. Tan SL, Jetzke M, Vergeld V, Müller C. Independent and combined associations of physical activity, sedentary time, and activity intensities with perceived stress among university students: internet-based cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020) 6:e20119. doi: 10.2196/20119

16. Roy SK, Jahan K, Alam N, Rois R, Ferdaus A, Israt S, et al. Perceived stress, eating behavior, and overweight and obesity among urban adolescents. J Health Popul Nutr. (2021) 40:54. doi: 10.1186/s41043-021-00279-2

17. Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2019) 107:525–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.040

18. Ozcelik M, Sahbaz C. Clinical evaluation of biological rhythm domains in patients with major depression. Braz J Psychiatry. (2020) 42:258–63. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0570

19. Au J, Reece J. The relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. (2017) 218:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.021

20. Adan A, Almirall H. Horne and ostberg morningness-eveningness questionnaire: a reduced scale. Pers Individ Dif. (1991) 12, 241–53. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(91)90110-W

21. Romo-Nava F, Tafoya SA, Gutierrez-Soriano J, Osorio Y, Carriedo P, Ocampo B, et al. The association between chronotype and perceived academic stress to depression in medical students. Chronobiol Int. (2016) 33:1359–68. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2016.1217230

22. Gulec M, Selvi Y, Boysan M, Aydin A, Oral E, Aydin EF. Chronotype effects on general well-being and psychopathology levels in healthy young adults. Biol Rhythm Res. (2013) 44:457–68. doi: 10.1080/09291016.2012.704795

23. Hidalgo MP, Caumo W, Posser M, Coccaro SB, Camozzato AL, Chaves ML. Relationship between depressive mood and chronotype in healthy subjects. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2009) 63:283–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01965.x

24. Li T, Xie Y, Tao S, Yang Y, Xu H, Zou L, et al. Chronotype, sleep, and depressive symptoms among chinese college students: a cross-sectional study. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:592825. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.592825

25. Zhou J, Hsiao FC, Shi X, Yang J, Huang Y, Jiang Y, et al. Chronotype and depressive symptoms: a moderated mediation model of sleep quality and resilience in the 1st-year college students. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:340–55. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23037

26. Rice F, Riglin L, Lomax T, Souter E, Potter R, Smith DJ, et al. Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptom profiles. J Affect Disord. (2019) 243:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.015

27. Russell G, Lightman S. The human stress response. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:525–34. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0228-0

28. Liu Z, Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Liang L, Wang Y, et al. Association between perceived stress and depression among medical students during the outbreak of COVID-19: the mediating role of insomnia. J Affect Disord. (2021) 292:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.028

29. Block J, Kremen AM. IQ and ego-resiliency: conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1996) 70:349–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.349

30. Padmanabhanunni A, Pretorius T. The loneliness-life satisfaction relationship: the parallel and serial mediating role of hopelessness, depression and ego-resilience among young adults in South Africa during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18, 3613. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073613

31. Hjemdal O, Vogel PA, Solem S, Hagen K, Stiles TC. The relationship between resilience and levels of anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adolescents. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2011) 18:314–21. doi: 10.1002/cpp.719

32. Ye B, Zhou X, Im H, Liu M, Wang XQ, Yang Q. Epidemic rumination and resilience on college students' depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of fatigue. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:560983. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.560983

33. Wrenn GL, Wingo AP, Moore R, Pelletier T, Gutman AR, Bradley B, et al. The effect of resilience on posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed inner-city primary care patients. J Natl Med Assoc. (2011) 103:560–6. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30381-3

34. Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M, Aslaksen PM, Flaten MA. Resilience as a moderator of pain and stress. J Psychosom Res. (2006) 61:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.12.007

35. Buckley TM, Schatzberg AF. On the interactions of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sleep: normal HPA axis activity and circadian rhythm, exemplary sleep disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2005) 90:3106–14. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1056

36. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. (1983) 24:385–96. doi: 10.2307/2136404

37. Giglio LM, Magalhaes PV, Andreazza AC, Walz JC, Jakobson L, Rucci P, et al. Development and use of a biological rhythm interview. J Affect Disord. (2009) 118:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.018

38. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

39. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. (2012) 184:E191–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829

40. Bolin JH. (2014). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. J Educ Meas. 51:335–7. doi: 10.1111/jedm.12050

41. Hawley LD, MacDonald MG, Wallace EH, Smith J, Wummel B, Wren PA. Baseline assessment of campus-wide general health status and mental health: opportunity for tailored suicide prevention and mental health awareness programming. J Am Coll Health. (2016) 64:174–83. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2015.1085059

42. Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, Baubet T, Habran E, Veerapa E, et al. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in france confined during the COVID-19 PANDEMIC. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2025591. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591

43. Graves BS, Hall ME, Dias-Karch C, Haischer MH, Apter C. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0255634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255634

44. Corsi-Cabrera M, Ramos J, Guevara MA, Arce C, Gutiérrez S. Gender differences in the EEG during cognitive activity. Int J Neurosci. (1993) 72:257–64. doi: 10.3109/00207459309024114

45. Wei J, Gong Y, Wang X, Shi J, Ding H, Zhang M, et al. Gender differences in the relationships between different types of childhood trauma and resilience on depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents. Prev Med. (2021) 148:106523. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106523

46. Mayer SE, Lopez-Duran NL, Sen S, Abelson JL. Chronic stress, hair cortisol and depression: a prospective and longitudinal study of medical internship. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2018) 92:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.03.020

47. Mahar I, Bambico FR, Mechawar N, Nobrega JN. Stress, serotonin, and hippocampal neurogenesis in relation to depression and antidepressant effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2014) 38:173–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.11.009

48. Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. (2004) 130:601–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601

49. Karrenbauer BD, Muller CP, Ho YJ, Spanagel R, Huston JP, Schwarting RK, et al. Time-dependent in-vivo effects of interleukin-2 on neurotransmitters in various cortices: relationships with depressive-related and anxiety-like behaviour. J Neuroimmunol. (2011) 237:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.05.011

50. O'Connor DB, Thayer JF, Vedhara K. Stress and health: a review of psychobiological processes. Annu Rev Psychol. (2021) 72:663–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

51. Soder E, Krkovic K, Lincoln TM. The relevance of chronic stress for the acute stress reaction in people at elevated risk for psychosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2020) 119:104684. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104684

52. Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2000) 23:477–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7

53. Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Dissociation between reactivity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system to repeated psychosocial stress. Psychosom Med. (2003) 65:450–60. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000035721.12441.17

54. Salaberry NL, Mendoza J. The circadian clock in the mouse habenula is set by catecholamines. Cell Tissue Res. (2022) 387:261–74. doi: 10.1007/s00441-021-03557-x

55. Fiksdal A, Hanlin L, Kuras Y, Gianferante D, Chen X, Thoma MV, et al. Associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety and cortisol responses to and recovery from acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2019) 102:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.11.035

56. Phillips MI. Neuropeptides: regulators of physiological processes. Regul Pept. (2000) 90:101. doi: 10.1016/S0167-0115(00)00102-6

57. Sunderajan P, Gaynes BN, Wisniewski SR, Miyahara S, Fava M, Akingbala F, et al. Insomnia in patients with depression: a STAR*D report. CNS Spectr. (2010) 15:394–404. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900029266

58. Hertenstein E, Feige B, Gmeiner T, Kienzler C, Spiegelhalder K, Johann A, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2019) 43. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006

59. Zhai L, Zhang H, Zhang D. Sleep duration and depression among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Depress Anxiety. (2015) 32:664–70. doi: 10.1002/da.22386

60. Jackson ML, Sztendur EM, Diamond NT, Byles JE, Bruck D. Sleep difficulties and the development of depression and anxiety: a longitudinal study of young Australian women. Arch Womens Ment Health. (2014) 17:189–98. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0417-8

61. Merikangas KR, Swendsen J, Hickie IB, Cui L, Shou H, Merikangas AK, et al. Real-time mobile monitoring of the dynamic associations among motor activity, energy, mood, and sleep in adults with bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. (2019) 76:190–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3546

62. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Silva ES, et al. Physical activity and incident depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175:631–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17111194

63. Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, Hallgren M, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:308–15. doi: 10.1002/wps.20458

64. Choi KW, Chen C-Y, Stein MB, Klimentidis YC, Wang M-J, Koenen KC, et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between physical activity and depression among adults: a 2-sample mendelian randomization study. JAMA Psychiatry. (2019) 76:399–408. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4175

65. Stengel A, Wang L, Tache Y. Stress-related alterations of acyl and desacyl ghrelin circulating levels: mechanisms and functional implications. Peptides. (2011) 32:2208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.07.002

66. Bremner JD, Moazzami K, Wittbrodt MT, Nye JA, Lima BB, Gillespie CF, et al. Diet, stress and mental health. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2428. doi: 10.3390/nu12082428

67. Maxwell MA, Cole DA. Weight change and appetite disturbance as symptoms of adolescent depression: toward an integrative biopsychosocial model. Clin Psychol Rev. (2009) 29:260–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.007

68. Hirschfeld RM, Montgomery SA, Keller MB, Kasper S, Schatzberg AF, Möller HJ, et al. Social functioning in depression: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. (2000) 61:268–75. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v61n0405

69. Tse WS, Bond AJ. The impact of depression on social skills. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2004) 192:260–8. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120884.60002.2b

70. Rehman US, Gollan J, Mortimer AR. The marital context of depression: research, limitations, and new directions. Clin Psychol Rev. (2008) 28:179–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.007

71. Wenzler S, Hagen M, Tarvainen MP, Hilke M, Ghirmai N, Huthmacher AC, et al. Intensified emotion perception in depression: differences in physiological arousal and subjective perceptions. Psychiatry Res. (2017) 253:303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.040

72. Li J, Theng Y-L, Foo S. Does psychological resilience mediate the impact of social support on geriatric depression? An exploratory study among Chinese older adults in Singapore. Asian J Psychiatr. (2015) 14:22–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.01.011

Keywords: depression, college students, adolescents, biorhythm, perceived stress, moderating mediation, resilience

Citation: Ma Y, Zhang B, Meng Y, Cao Y, Mao Y and Qiu C (2022) Perceived stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of biorhythm and ego resilience. Front. Public Health 10:951717. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.951717

Received: 24 May 2022; Accepted: 04 July 2022;

Published: 04 August 2022.

Edited by:

M. Tasdik Hasan, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Martin Rigelsky, University of Prešov, SlovakiaCopyright © 2022 Ma, Zhang, Meng, Cao, Mao and Qiu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Changjian Qiu, cWl1Y2hhbmdqaWFuMThAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.