- 1Center for Medical Humanities in the Developing World, School of Translation Studies, Qufu Normal University, Rizhao, China

- 2School of International Affairs and Public Administration, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 3Centre for Quality of Life and Public Policy, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 4School of Economics and Management, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China

- 5Rizhao Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Rizhao, China

Objective: This study aimed to conduct a systematic review of the global experiences of community responses to the COVID-19 epidemic.

Method: Five electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science) were searched for peer-reviewed articles published in English, from inception to October 10, 2021. Two reviewers independently reviewed titles, abstracts, and full texts. A systematic review (with a scientific strategy for literature search and selection in the electronic databases applied to data collection) was used to investigate the experiences of community responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results: This review reported that community responses to COVID-19 consisted mainly of five ways. On the one hand, community-based screening and testing for Coronavirus was performed; on the other hand, the possible sources of transmission in communities were identified and cut off. In addition, communities provided medical aid for patients with mild cases of COVID-19. Moreover, social support for community residents, including material and psychosocial support, was provided to balance epidemic control and prevention and its impact on residents' lives. Last and most importantly, special care was provided to vulnerable residents during the epidemic.

Conclusion: This study systematically reviewed how communities to respond to COVID-19. The findings presented some practical and useful tips for communities still overwhelmed by COVID-19 to deal with the epidemic. Also, some community-based practices reported in this review could provide valuable experiences for community responses to future epidemics.

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 was reported in December 2019 (1). Considering the fast spread of the epidemic, it was declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization (WHO) on January 30, 2020 (2), and further announced as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (3). Then, the confirmed cases of COVID-19 increased from 987 on January 11, 2020, to 314,181,638 on January 11, 2022, and the death toll from 17 to 5,530,773 (4). Over the past year, the number of daily new cases has shown a fluctuating trend, ranging from 300,000 to 900,000. No downward trend has been reported in sojourns, even after the COVID-19 vaccine has been administered worldwide (3). Therefore, besides promoting vaccination campaigns, the role of epidemic prevention and control actions remains important.

Community cluster infections are a significant cause of the rapid spread of the COVID-19 pandemic; they have been reported in most affected countries in the world (5). In China, the community cluster infection was the primary reason why large numbers of people were infected at the beginning of the outbreak of COVID-19. In this review, “community” refers to “residential community”. According to the definition of the WHO, community is “a group of individuals who live together in a specific geographical place, which maintains social relations among its members who recognize that they belong to such a community” (6). Thus, activities that require the community to cluster can facilitate the spread of the epidemic within the community and expose residents to the dangers of the pandemic (7, 8). Group gathering and intimate contact are widespread due to often high population density in communities, providing a high possibility for the spread of the epidemic (9). COVID-19 pandemic is highly transmissible with various transmission routes such as airborne, respiratory droplets, and direct close contact. In this sense, communities are more susceptible to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic (10). The community spread has been reported in many countries (11).

In response to the community spread of COVID-19, the WHO launched a comprehensive guideline on community epidemic prevention, “Responding to community spread of COVID-19: Interim Guidance” on March 7, 2020 (12). Governments from many countries attached great importance to the community spread of the epidemic and took a series of strict measures to prevent and control the epidemic in communities. China, Japan, the United States, and other countries formulated plans for community epidemic prevention. Many communities around the world are exploring countermeasures to contain the epidemic. Although the epidemic is still raging around the world, some measures taken by communities have played important roles in controlling the spread of the epidemic, thus providing valuable experiences for areas still overwhelmed by COVID-19. Furthermore, global experiences of community responses to COVID-19 can also shed some light on global community responses to future pandemics.

A bulk of information exists about the community responses to COVID-19 in different countries. It is necessary to summarize the reported experiences of community responses. Several reviews explored the experiences of certain aspects of community responses to COVID-19, such as face masks (13), hand hygiene (14), contact tracing (15), and risk communication (16). However, a comprehensive review of the experiences of community responses to COVID-19 is lacking. In this study, we searched published articles about community responses to COVID-19 through electronic databases. The global experiences of community responses to COVID-19 will be approached from multiple aspects with different themes via a systematic review of the collected data.

Methods

Study Design

In this study, a systematic review was used to investigate the experiences of community responses to COVID-19 (17). Systematic review is a research method for the systematic and objective interpretation of literature content through the classification process of coding and identifying themes (18). Given its potential for interpreting the literature systematically and addressing the richness and uniqueness of the data, systematic review has been widely used in health-related disciplines and fields, including nursing (19), health promotion (20), and health services and management (21). In recent years, health researchers have begun to use this method to describe and summarize the practices and experiences in the health field (22–25).

This study was conducted based on the methodological approach pioneered by Khan et al., which consisted of the following five stages (26). Stage 1 was to identify the research question, which could guide the way of data collection. Our research question was: How did communities respond to COVID-19 worldwide? Stage 2 was to identify relevant publications. We adopted a scientific strategy to search for the relevant literature, which could answer the research question as much as possible, and employed a systematic mechanism to exclude literature not related to our research question. Stage 3 was to assess the quality of the selected literature. Stage 4 was to chart and analyze the extracted data. A narrative synthesis was used to develop themes and subthemes in this study. The last stage was to report the results and interpret the findings.

Data Collection

Literature Search

Five electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science) were used to conduct a thorough search of the published literature related to COVID-19 control and prevention in global residential communities from inception to October 10, 2021. According to the objectives of this review and the PICo template for systematic reviews (27), the search strategy consisted of sets of terms for Population (actors involved in community's response to the COVID-19), the phenomenon of Interest (community measures in response to COVID-19) and the Context (residential community). Literature search terms (MeSH terms) were used to retrieve relevant studies as much as possible (see Supplementary Material 1). All collected articles were exported into reference management software NoteExpress for convenience management.

Literature Selection

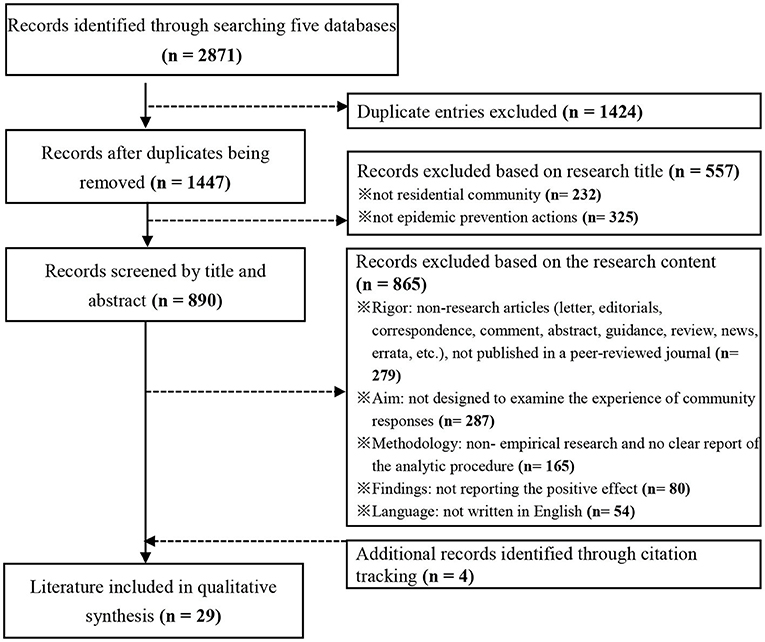

A three-step process proposed by Lockwood et al. (28) was used to review and select the relevant literature closely related to the research question (Figure 1).

First, 2,871 articles were obtained in total. The title of each article was carefully read to exclude the duplicated entries. A total of 1,424 duplicated entries were found, and thus 1,447 records were screened with their titles.

Second, an initial review of the titles was conducted by two independent reviewers to exclude the entries whose titles showed that they were clearly outside the scope of the study. If an agreement on the exclusion of an article could not be reached between those who had read the title, they included it for further review of its full text. A total of 557 articles were excluded at this stage. Among these, 232 records did not involve the residential community. The topics included other forms of the community during COVID-19, such as “oncology community” (29), “virtual community” (30), “nursing community” (31), “deaf community” (32), “East African community” (33), and others. Furthermore, 325 records had no strong correlation with epidemic prevention, and the topics included “risks and vulnerabilities” (34), “community mobility” (35), “fear effect” (36), “mental health” (37), “economic impacts” (38), “living experiences” (39), and so on.

Third, the full texts of 890 remaining articles were read by two independent reviewers to exclude the entries that could not provide a valid representation of the experience of community epidemic prevention and control. Any disagreements at any stage were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (26). In this step, non-research articles, non-empirical research articles, articles without a clear report of the analytic procedure, and articles not reporting the positive effect of community responses were excluded. Besides, 54 non-English articles were also excluded. Then, 25 articles met the inclusion criteria for this study. In addition, four additional articles were identified through citation tracking.

Quality Appraisal

As this review involved quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to appraise the quality of the included literature (40). MMAT was purposely designed as a checklist for concomitantly appraising the methodological quality of different types of empirical studies (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies) included in systematic mixed-study reviews (40). The MMAT (Version 2018) provides a set of criteria for screening questions, and a score is made for each study. QZ and YW independently appraised the quality of the included studies, and appraisal disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached (Supplementary Material 2). Given the good quality score of each study, no studies were excluded (41).

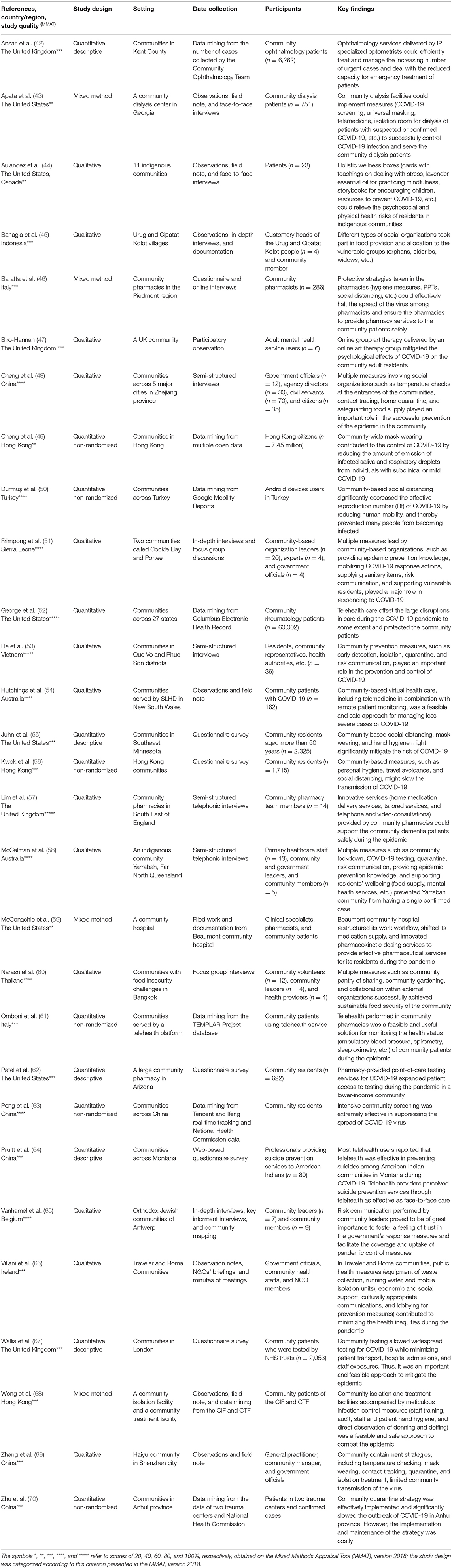

Data Extraction

Studies were extracted according to the following characteristics: authors, year, country/region, study quality (MMAT score), study design, study setting, data collection, participants, and key findings (Table 1). The first reviewer conducted data extraction, which was re-checked by a second reviewer (YW).

Data Synthesis

As the included studies were a mixture of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies, a narrative synthesis of the data was conducted using a thematic approach (71). The narrative synthesis aimed to present a descriptive summary of findings across the included studies and generate themes relevant to the aims of this review (72).

In this review, we followed the method for qualitative data synthesis proposed by Elo and Kyngäs, which consisted of three phases (73). In the preparation phase, the core tasks were “deciding on what to analyze in what detail” and “selecting the unit of analysis”; we focused our analysis on the actions/measures against the COVID-19 pandemic (74). In the organizing phase, the core tasks were open coding, creating categories, and the abstraction. For open coding, two researchers read through the article and wrote down headings about community epidemic prevention and control independently (74). For category creation, the lists of headings were grouped under higher-order subthemes, which could provide a good knowledge of community responses to COVID-19 pandemic (75). For data abstraction, sub-themes with content similarities were grouped as main themes (76). In the reporting phase, the analytical process and categories of the results were reported in detail.

To ensure methodological rigor, two researchers (QZ and YW) independently coded all the included literature. Coding disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached (77). In addition, codes were expanded and changed to ensure that they were extremely exhaustive during the coding process (78). PRISMA checklist was provided in Supplementary Material 3 (79).

Results

The characteristics and quality assessments of 29 included studies are shown in Table 1. All of them were published after 2019. Six studies were conducted in the United States, five in China, four in the United Kingdom, three in Hong Kong, two in Italy and Australia, respectively, and one in Belgium, Ireland, Thailand, Turkey, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Sierra Leone, respectively. Thirteen of the 29 included studies used qualitative study design, twelve employed quantitative study design, and four used mixed methods. MMAT findings showed that the quality of included studies was variable, with a mixture of studies having 100% (n = 3), 80% (n = 8), 60% (n = 14), and 40% (n = 4) quality.

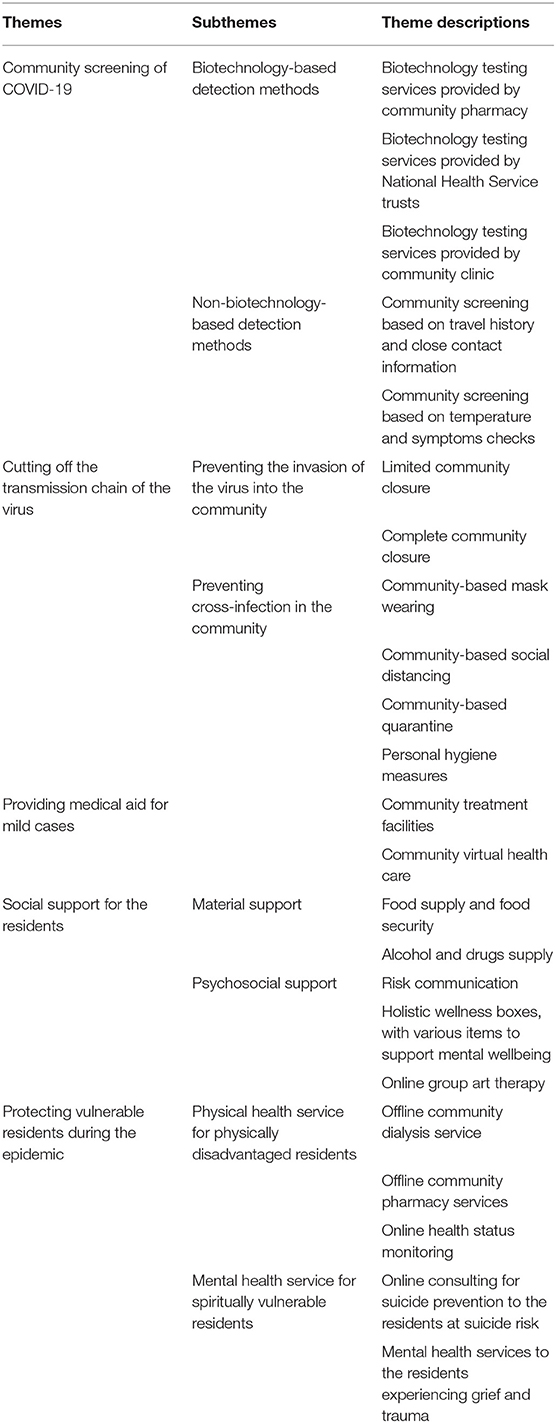

The results showed that global experience of community responses to COVID-19 epidemic were composed of the following five themes (Table 2).

Community Screening for COVID-19

Six studies addressed the theme of community screening for COVID-19 (48, 53, 58, 62, 63, 67). There were two subthemes relating to this theme: biotechnology-based detection methods and non-biotechnology-based detection methods.

Biotechnology-Based Detection Methods

Biotechnology-based methods for COVID-19 testing have been widely used in communities of developed countries, where medical resources are relatively abundant. Compared with centralized COVID-19 testing, community-based testing has its unique advantages. In a large lower-income community in Arizona, a community pharmacy provided point-of-care testing services for its residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacists were trained to administer COVID-19 tests to their community residents. Residents received a pharmacist-guided nasal self-swab collection and got their results within 24 h by a follow-up phone call (62). The community testing program provided by National Health Service Trust in London also showed that community testing could provide an accurate picture of how many confirmed cases would exist in a community (67). In an Australian indigenous community Yarrabah, community-based testing was provided by a primary healthcare center. Community-based testing, aside from other measures, successfully prevented the invasion of COVID-19 into Yarrabah community (58). It was also suggested that the nationwide intensive community screening in China was extremely effective in controlling the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic (63).

Non-biotechnology-based Detection Methods

Biotechnology-based detection methods require a large amount of human and medical resources, which pose great challenges for communities. Thus, besides biotechnology-based detection methods, non-biotechnology-based detection methods were also used in community responses to COVID-19. In Vietnam, the community volunteers collected epidemic-related data from residents, including daily temperature and symptoms of household members (53). In addition, community officials collected residents' travel history and their close contact information in order to identify at-risk cases (53). The suspected cases were reported to the local health authority, which decided whether they needed testing, isolation, quarantine, or hospitalization. This ensured the early detection of high-risk cases and prevented the spread of COVID-19 in communities (53). In China, community officials aside from volunteers contacted each resident to determine whether they had been in close contact with confirmed patients. The screening information was shared with the local Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for further measures (48).

Cutting Off the Transmission Chain of the COVID-19

This theme examined how residential communities cut off the transmission chain of COVID-19. This theme involved nine studies (48–50, 53, 55, 56, 58, 69, 70). Two subthemes underpinned this theme, that is, preventing the invasion of the COVID-19 into the community and preventing cross-infection in the community.

Preventing the Invasion of the COVID-19 Into the Community

Community closure was carried out to prevent the invasion of COVID-19 into the community. Different countries adopted different strategies for community closure with different stringencies. A community called Yarrabah in Australia implemented limited “community lockdown” measure, which required that all residents should undergo a 14-day isolation before entry or re-entry into Yarrabah. Note that residents who were in urgent circumstances were exempt from travel restrictions. For example, community residents suffering from illnesses were allowed to travel to the designated hospitals outside the community for short-term medical treatment (58). Some communities in China adopted complete community closure. For instance, an 18-day community lockdown was implemented in the Yuanqiao community in Zhejiang province of China, and all residents were not allowed to leave their homes unless for a permitted reason. The local government and community-based organizations provided food (pork, vegetables, eggs, rice, cooking oil, etc.) for the residents living in the Yuanqiao community to help them get through the quarantine period (48). Community closure proved effective in preventing the community spread of the COVID-19.

Preventing Cross-Infection in the Community

Multiple measures have been adopted to prevent cross-infection in the community. Mask wearing, an initiative from the WHO, is the most widely used measure across the global communities. More evidence has shown that community-wide mask wearing can help stop the spread of COVID-19. Data from Hong Kong communities showed that community-wide mask wearing contributed to the control of COVID-19 by reducing the amount of emission of infected saliva and respiratory droplets from infected patients (49). The surveys on communities in the United States and China also showed that community-based mask wearing limited the community transmission of the virus (55, 69).

Social distancing is another effective way for community epidemic prevention, preventing disease transmission by reducing close contact between people. Social distancing consists of a range of concrete measures, including public place closure, gathering cancellation, avoiding close contact with other people, and staying at home. Data from Google Mobility Reports in Turkey showed that the community-based social distancing interventions (e.g., public place closure. travel restrictions, and cancellation of religious activities) significantly decreased the transmission of COVID-19 by reducing human mobility, and thereby prevented residents from becoming infected (50). In addition, community-based social distancing (e.g., avoiding taking public transport and engaging in social activities, and keeping a distance of 6 feet from others in a public space) played an important role in stopping the transmission of COVID-19 in Southeast Minnesota, the United States, and Hong Kong, China (55, 56).

Quarantine, one of the oldest and most effective tools for controlling the spread of communicable diseases, has also been used to stop the community spread of COVID-19. The WHO recommends that the contacts of patients with COVID-19 must be quarantined for 14 days from their last contact with the patient. These measures are adopted by many countries, but the range of residents required to be quarantined varies from country to country. In some residential areas of developed countries such as Australia, suspected cases need to be quarantined based on biotechnology-based testing (58). However, in some developing countries, suspected patients were quarantined at home based on mass non-biotechnology-based community screening. For example, in Vietnam, residents who traveled to the pandemic epicenter needed to be quarantined at home (53). In China, close contacts, travelers from the pandemic epicenter, and residents with a high fever for a week had to undergo 14 days of home quarantine (69). It was suggested that community quarantine of residents with suspected symptoms and clear exposure history significantly reduced the risk of the outbreak of COVID-19 in Anhui province of China (70).

Providing Medical Aid for Mild Cases

This theme concerned how residential communities provided home-based medical aid for infected patients with mild symptoms. At the beginning of the epidemic, medical facilities did not have sufficient capacity for admitting patients. Thus, some communities tried to provide medical aid for their residents with mild symptoms. Hong Kong built community isolation facilities (CIF) and community treatment facilities (CTF) for symptomatic patients who did not require advanced medical resources. CIF and CTF accompanied by meticulous infection control measures (staff training, audit, staff and patient hand hygiene, and direct observation of donning and doffing) proved to be a feasible and safe approach to combat the epidemic (68).

In addition to centralized surveillance and care, some countries explored virtual observation and care to meet the challenge of housing and personnel storage. In New South Wales, Australia, virtual health care was established by Sydney Local Health District (SLHD) to monitor the residents' body condition, including respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, pulse rate, and temperature. Patients who were quarantined at home were contacted by video conference software twice every 24 h to recognize the signs and symptoms related to their deteriorating conditions. The deteriorating patients were transferred to the local emergency department by ambulances (54).

Social Support for the Residents

Seven studies highlighted community's social support for the residents (44, 45, 47, 48, 60, 65, 66). This theme consisted of two sub-themes, that is, material support and psychosocial support.

Material Support

In response to the movement restrictions imposed by the lockdown measures, some communities provided food supplies to their residents. For example, in a community called Yuanqiao in the Zhejiang province of China, a 18-day community lockdown was implemented. The local government and community-based organizations delivered food (e.g., pork, vegetables, eggs, rice, and cooking oil) to the residents who were not allowed to leave their homes during the quarantine period. Due to these efforts, the degree of complaints about the long-time lockdown was significantly reduced (48). In terms of food insecurity, the communities in Bangkok and Thailand adopted multiple measures (e.g., community pantry and community gardening) to ensure food security (60). In two Indonesian villages (Urug and Cipatat Kolot), the residents experienced a severe food shortage because the food markets were suspended from operations. The food shortages were addressed by charitable donations. Different types of social organizations took part in food provision and allocation to the vulnerable groups (orphans, elderly people, widows, etc.) (45).

Psychosocial Support

Some communities adopted “risk communication” to establish trusted communication channels with their residents. In communities of Ireland, culturally appropriate communication strategies were used to increase community trust (66). To be specific, the culture (norms, beliefs, and values) of the target population was fully considered. In this sense, communication strategy would be more likely to be accepted by the target population (66). In the Orthodox Jewish communities of Antwerp, Belgium, a community-based communication strategy was used to promote risk communication with their residents. In addition, community volunteers operated a telephone “hotline,” to which community residents could turn for help when they were in trouble. Furthermore, the risk communication performed by community leaders in Orthodox was also proved to be of great importance in fostering a feeling of resident trust in the government (65).

Along with risk communication, mental health services were provided to community residents during the epidemic. The Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health delivered holistic wellness boxes (e.g., cards with teachings on dealing with stress, lavender essential oil for practicing mindfulness, and storybooks for encouraging children) to indigenous communities in the United States and Canada, which relieved their psychosocial problems effectively (44). An online art therapy group from the United Kingdom delivered online therapy to the community residents. They were encouraged to share artworks they made and discuss their images and techniques used, which helped them build resilience, increase self-awareness, and improve self-esteem (47).

Protecting Vulnerable Residents During the Epidemic

This theme addressed eight studies that focused on protecting vulnerable residents during the epidemic (43, 46, 52, 57–59, 61, 64). Two subthemes underpinned this theme: physical health service for physically disadvantaged residents and mental health service for spiritually vulnerable residents.

Physical Health Service for Physically Disadvantaged Residents

Residents with severe or chronic diseases are more vulnerable to the COVID-19 epidemic. Many medical institutions tried to reform their working models to sustain their medical services for vulnerable individuals. A community dialysis center in Georgia, the United States, implemented a range of measures (e.g., screening tests, wearing masks for all individuals, reducing patient wait times, telemedicine, and isolation room for suspected or confirmed patients) for infection prevention and control and could thus be able to continue providing patients with hemodialysis services (43). Also, pharmacies in Piedmont communities of Italy adopted some effective strategies (e.g., personal hygiene measures, disinfection in public spaces, social distancing, universal masking, and confirmed staff being placed under quarantine) to stop the spread of the virus among pharmacists, which could ensure that they could provide safe health care to their community residents (46). In addition, many community health facilities offered telehealth services for their residents during this epidemic. Community pharmacies in the South East of England reformed their service modes and implemented innovative services, which consisted of home medication delivery services, tailored services, and telephone consultations (57). This benefited community-based dementia patients a lot (57). In Italy, telehealth performed by community pharmacies was proved to a feasible and useful way to monitor the health status (e.g., ambulatory blood pressure, spirometry, and sleep oximetry) of community patients during the epidemic (61).

Mental Health Service for Spiritually Vulnerable Residents

Some residents felt stressed, worried, or anxious during the epidemic. Thus, communities tried to provide psychological comforts for their residents. For example, American Indians and Alaska Natives were at a higher risk of suicide than any other racial or ethnic groups in the United States (64). Thus, these individuals were provided with online consulting services via video conferencing platforms, telephone, e-mail, or texting, which were effective in preventing suicides (64). In addition, a social and emotional wellbeing team was established in a community called Yarrabah in Australia, which provided home-based mental health services for community residents experiencing elevated fear, anxiety, grief, and trauma (58).

Discussion

Principal Findings

This study revealed some common experiences of community responses to the COVID-19 epidemic. First, this review found that the viral screening test was mostly used to stop the spread of the virus in the community, and untimely or delayed screening may cause community spread. In addition, immediate measures were taken to cut off the transmission route of the virus, which is in line with many previous studies (80, 81). Some measures were community-oriented measures, such as community closure and home quarantine. Whole-of-society measures including mask wearing and social distancing were also implemented in the community setting. Second, it is of great importance to balance epidemic management and residents' daily lives. As mentioned earlier, some measures, such as community closure and social activity restrictions, may influence the normal lives of residents. Thus, some community services, including material and psychological support, were used to balance epidemic management and residents' lives. Third, vulnerable individuals have been given more attention during the epidemic (82, 83). Vulnerable individuals may suffer more from COVID-19, thus a range of measures have been taken, including physical health service for physically disadvantaged residents and mental health service for spiritually vulnerable residents. Fourth, the participation of multiple actors is the key to the success of community epidemic control and prevention. Many actors are involved in community response to the epidemic, including the government, community organizations, community hospitals and medical centers, pharmacists, community workers, volunteers, residents, NGOs, business organizations, and so on. The participation of multiple actors, also known as community engagement, can give full play to the strengths of different actors in different tasks of epidemic prevention, such as plan designing, trust building, risk communication, surveillance and tracing, resource supply, trust building, and protection of vulnerable groups (84–87).

The global experiences of community responses to COVID-19 is a rich database for future epidemic prevention and control in the community. However, no “one-size-fits-all” model exists for community epidemic prevention and control, and many of these experiences cannot be replicated directly in every instance. Some preconditions need to be considered in the design of community measures.

First, measures taken by communities need to be commensurate with the affordability of the national economy. Some measures such as social distancing and societal closure have proven highly effective at reducing the community transmission of COVID-19. However, these measures may cause social and economic damage (88, 89). For example, a study showed that the lockdown measure in Chile was associated with a 10–15% drop in local economic activity, which was twice the reduction in local economic activity suffered by municipalities that were not under lockdown. A 3-to-4 month lockdown had a similar effect on economic activity than a year of the 2009 great recession (90). In low-and middle-income countries, strict social distancing measures (e.g., nationwide lockdown) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are unsustainable in the long term due to knock-on socioeconomic and psychological effects. Compared with prolonged lockdown, zonal or local lockdowns may be a better option for these countries (91). Therefore, resources and economic capacity should be taken into full account when designing and taking epidemic prevention measures.

Second, existing health system capabilities, as the basis of prevention measures, cannot be ignored. For example, a strategy of limited lockdown of an objectively identified selected high-risk population might be a cost-effective option compared with a generalized lockdown. However, limited lockdown is more commonly used in developed countries rather than in developing ones. It can involve comprehensive biotechnology-based screening for suspected cases and thorough tracing of contacts based on adequate medical resources and a well-supported, community-based team of trained personnel, which are often not available in developing countries (92, 93). Health system capabilities define possible boundaries for community prevention measures.

Third, a country's social culture needs to be considered. For example, epidemic-relevant information registration is accepted by East Asian countries such as China, Japan, and Singapore (94, 95) but may be considered an infringement of privacy in Western countries (96, 97). In addition, home quarantine, which is widely used in China, India, and Vietnam, may be considered a restriction on personal freedom in Western countries (98, 99).

Fourth, community epidemic prevention and control need to be commensurate with the national concepts of epidemic prevention. Taking “cutting off the transmission route of the virus” as an example, community closure, social distancing (public places closure and gathering cancellation), quarantine, and travel restrictions are collectively referred to as community containment strategies (100). However, personal protective measures (handwashing, cough etiquette, and face mask), social distancing (maintaining physical distance between persons in community settings and staying at home), and cleaning and disinfection in community settings are collectively referred to as community mitigation strategies (9). Some countries (e.g., China and Singapore) tend to use community containment strategies, whereas others (e.g., the UK) prefer to use community mitigation strategies (101).

Finally, the unique circumstances of each community should be considered. Just as CDC Community Mitigation Framework (the United States) reported, each community is unique, and prevention strategies should be carried out based on the characteristics of each community (102). Specifically, different communities vary significantly in economic conditions (103), population density (104), vulnerability degree (105), physical environment (106), health facilities (107), and so on. Thus, these factors should be fully considered by policymakers when making prevention measures. In this sense, it seems that no “one-size-fits all” approach exists to fight COVID-19 in the community, and multiple contextual factors should be taken into full account.

Strengths and Limitations

In this review, we made a comprehensive analysis of community responses to COVID-19, which could provide not only a comprehensive understanding of community responses to COVID-19, but also insightful findings that could not be obtained by a review focusing mainly on a single measure. Although this review followed a rigorous process of systemic literature review, it could not be guaranteed that this review could fully reflect “global experiences of community responses to COVID-19.” As with all literature reviews, five electronic databases rather than all electronic databases were used for searching the literature due to the huge cost of searching all the databases (108, 109). Accordingly, some relevant studies might be missing in this review. The eligibility criteria were used for literature selection. Therefore, some relevant studies (gray literature, non-English literature, etc.) could not be included in this review (110, 111).

Conclusions

Communities around the world took multiple measures to fight against the epidemic. Community responses to COVID-19 consisted mainly of five ways. On the one hand, community-based screening and testing for Coronavirus was performed; on the other hand, the possible sources of transmission in communities were identified and cut off. In addition, communities provided medical aid for patients with mild cases of COVID-19. Moreover, social support for community residents, including material and psychosocial support, was provided to balance epidemic control and prevention and its impact on residents' lives. Last and most importantly, special care was provided to vulnerable residents during the epidemic. The findings presented some practical and useful tips for communities still overwhelmed by COVID-19 to deal with the epidemic. Also, some community-based practices reported in this review could provide valuable experiences for community responses to future epidemics.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

QZ conceived the study and all authors participated in its design. YW drafted the manuscript. ML, QM, and LL have been involved in discussing earlier versions of the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant ID: ZR2021QG015). The funding body did not influence this paper in any way prior to circulation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to scholars who have conducted research on COVID-19 prevention in the community.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.907732/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019; PHEIC, public health emergency of international concern; WHO, World Health Organization; MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; UK, United Kingdom; PPE, personal protective equipment; Rt, effective reproduction number; NGOs, non-government organizations; NHS, National Health Service; CIF, community isolation facility; CTF, community treatment facility; CDC, center for disease control and prevention; VHC, virtual health care; CAIH, center for American Indian health; LMICs, low and middle-income countries; CMH, Community mental health.

References

1. Ciotti M, Ciccozzi M, Terrinoni A, Jiang WC, Wang CB, Bernardini S. The COVID-19 pandemic. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. (2020) 57:365–88. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198

2. WHO. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report 11. Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200131-sitrep-11-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=de7c0f7_4 (accessed January 31, 2020).

3. WHO. WHO Announces COVID-19 Outbreak a Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic (accessed May 11, 2020).

4. Worldometers. Coronavirus Worldwide Graphs. Available online at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/worldwide-graphs/ (accessed January 13, 2022).

5. Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Hosein Z, Patidar R, Desai P, Prakash S, et al. Global pandemicity of COVID-19: situation report as of June 9, 2020. Infect Dis Res Treat. (2021) 14:1178633721991260. doi: 10.1177/1178633721991260

6. GarcÍa I, Giuliani F, Wiesenfeld E. Community and sense of community: the case of an urban barrio in Caraca. J Commun Psychol. (1999) 27:727–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199911)27:6<727::AID-JCOP7>3.0.CO;2-Y

7. Kim NJ, Choe PG, Park SJ, Lim JY, Lee WJ, Kang CK, et al. A cluster of tertiary transmissions of 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in the community from infectors with common cold symptoms. Korean J Internal Med. (2020) 35:758–64. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2020.122

8. Prabhu SM, Subramanyam N, Girdhar R. Containing COVID-19 pandemic using community detection. J Phys Conf Series. (2021) 1797:012008. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1797/1/012008

9. Lasry A, Kidder D, Hast M, Poovey J, Sunshine G, Winglee K, et al. Timing of community mitigation and changes in reported COVID-19 and community mobility - Four U.S. metropolitan areas, February 26-April 1, 2020. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:451–7. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e2

10. Furuse Y, Tsnchiya N, Miyahara R, Yasuda I, Sando E, Ko YK, et al. COVID-19 case-clusters and transmission chains in the communities in Japan. J Infect. (2021) 84:248–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.08.016

12. WHO. Responding to Community Spread of COVID-19: Interim Guidance. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/responding-to-community-spread-of-covid-19 (accessed March 07, 2020).

13. Bubbico L, Mastrangelo G, Larese-Filon F, Basso P, Rigoli R, Maurelli M, et al. Community use of face masks against the spread of covid-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3214. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063214

14. Hoffmann T, Bakhit M, Krzyzaniak N, Mar CD, Scott AM, Glasziou P. Soap versus sanitiser for preventing the transmission of acute respiratory infections in the community: a systematic review with meta-analysis and dose–response analysis. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e046175. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046175

15. Grekousis G, Liu Y. Digital contact tracing, community uptake, and proximity awareness technology to fight COVID-19: a systematic review. Sustain Cities Soc. (2021) 71:102995. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.102995

16. Tambo E, Djuikoue IC, Tazemda G K, Fotsing MF, Zhou XN. Early stage risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) strategies and measures against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Global Health J. (2021) 5:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.glohj.2021.02.009

17. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. New York: Springer (2007)

18. Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. Am J Nurs. (2014) 114:53–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000444496.24228.2c

19. Cummings G, Lee H, Macgregor T, Davey M, Wong C, Paul L, et al. Factors contributing to nursing leadership: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2008) 13:240–8. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007154

20. Cyril S, Smith BJ, Renzaho AMN. Systematic review of empowerment measures in health promotion. Health Promot Int. (2016) 31:809–26. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav059

21. Henssler J, Stock F, van Bohemen J, Walter H, Heinz A, Brandt L. Mental health effects of infection containment strategies: quarantine and isolation—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2021) 271:223–34. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01196-x

22. Braithwaite J, Marks D, Taylor N. Harnessing implementation science to improve care quality and patient safety: a systematic review of targeted literature. Int J Qual Health Care. (2014) 26:321–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu047

23. Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:98. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z

24. Zitzmann N U, Matthisson L, Ohla H, Joda T. Digital undergraduate education in dentistry: a systematic review. Int J Environmental Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3269. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093269

25. Zygouri I, Cowdell F, Ploumis A, Gouva M, Mantzoukas S. Gendered experiences of providing informal care for older people: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:730. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06736-2

26. Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. J R Soc Med. (2003) 96:118–21. doi: 10.1177/014107680309600304

27. Pettigrew M, Roberts H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing (2015).

28. Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evid Implement. (2015) 13:179–87. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

29. Vanderpuye V, Elhassan MMA, Simonds H. Preparedness for COVID-19 in the oncology community in Africa. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:621–2. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30220-5

30. Austin R, Holt J, Odom K, Odom K, Rajamani S, Monsen K. Virtual community outreach to examine resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Adv Health Med. (2021) 10:47.

31. Bagnasco A, Zanini M, Hayter M, Catania G, Sasso L. COVID 19: a message from Italy to the global nursing community. J Adv Nurs. (2020) 76:2212–4. doi: 10.1111/jan.14407

32. Panko TL, Contreras J, Postl D, Mussallem A, Champlin S, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. The deaf community's experiences navigating COVID-19 pandemic information. Health Literacy Res Pract. (2021) 5:e162–70. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20210503-01

33. Affara M, Lagu H I, Achol E, Karamagi R, Omari N, Ochido G, et al. The East African Community (EAC) mobile laboratory networks in Kenya, Burundi, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan-from project implementation to outbreak response against Dengue, Ebola, COVID-19, and epidemic-prone diseases. BMC Med. (2021) 19:160. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02028-y

34. Poteat T, Millett GA, Nelson LRE, Beyrer C. Understanding COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities among black communities in America: the lethal force of syndemics. Ann Epidemiol. (2020) 47:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004

35. Sulyok M, Walker M. Community movement and COVID-19: a global study using Google's Community Mobility Reports. Epidemiol Infect. (2020) 148:e284. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002757

36. Bozkurt F, Yousef A, Abdeljawad T, Kalinli A, Mdallal QA. A fractional-order model of COVID-19 considering the fear effect of the media and social networks on the community. Chaos Solitons Fractals. (2021) 152:111403. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111403

37. Scott JM, Yun SW, Qualls SH. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and distress of community dwelling older adults. Geriatr Nurs. (2021) 42:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.06.020

38. Hoque MS, Bygvraa DA, Pike K, Hasan MM, Rahman MA, Akter S, et al. Knowledge, practice, and economic impacts of COVID-19 on small-scale coastal fishing communities in Bangladesh: policy recommendations for improved livelihoods. Marine Policy. (2021) 131:104647. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104647

39. Xie B, Shiroma K, De Main AS, Davis NW, Fingerman K, Danesh V. Living through the COVID-19 pandemic: community-dwelling older adults' experiences. J Aging Soc Policy. (2021) 33:380–97. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2021.1962174

40. Pluye, P, Robert, E, Cargo, M, Bartlett, G, O'Cathain, A, Griffiths, F, et al. Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews. Available online at: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/page/24607821/FrontPage (accessed January 14, 2022).

41. Aston L, Eyre C, McLoughlin M, Shaw RL. Reviewing the evidence base for the children and young people safety thermometer (CYPST): a mixed studies review. Health. (2016) 4:8. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4010008

42. Ansari E, Patel M, Harle D. Acute community ophthalmology services provided by independent prescribing optometrists supporting hospital eye services during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Optometry. (2022) 15:175–8. doi: 10.1016/j.optom.2021.01.002

43. Apata IW, Cobb J, Navarrete J, Burkart J, Plantinga L, Lea JP. COVID-19 infection control measures and outcomes in urban dialysis centers in predominantly African American communities. BMC Nephrol. (2021) 22:81. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02281-6

44. Aulandez KMW, Walls ML, Weiss NM, Sittner KJ, Gillson SL, Tennessen EN, et al. Cultural sources of strength and resilience: a case study of holistic wellness boxes for covid-19 response in indigenous communities. Front Sociol. (2021) 6:612637. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.612637

45. Bahagia B, Hudayana B, Wibowo R, Anna Z. Local wisdom to overcome COVID-19 pandemic of Urug and Cipatat Kolot societies in Bogor, West Java, Indonesia. Forum Geografi. (2020) 34:146–60. doi: 10.23917/forgeo.v34i2.12366

46. Baratta F, Visentin GM, Enri LR, Parente M, Pignata I, Venuti F, et al. Community pharmacy practice in Italy during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: regulatory changes and a cross-sectional analysis of seroprevalence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:2302. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18052302

47. Biro-Hannah E. Community adult mental health: mitigating the impact of Covid-19 through online art therapy. Int J Art Ther. (2021) 26:96–103. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2021.1894192

48. Cheng Y, Yu JN, Shen YD, Huang B. Coproducing responses to COVID-19 with community-based organizations: lessons from Zhejiang Province, China. Public Adm Rev. (2020) 80:866–73. doi: 10.1111/puar.13244

49. Cheng VCC, Wong SC, Chuang VWM, So SYC, Chen JHK, Sridhar S, et al. The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. (2020) 81:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.024

50. Durmuş H, Gökler ME, Metintaş S. The effectiveness of community-based social distancing for mitigating the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. J Prevent Med Public Health. (2020) 53:397–404. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.381

51. Frimpong LK, Okyere SA, Diko SK, Abunyewah M, Erdiaw-Kwasie MO, Commodore TS, et al. Actor-network analysis of community-based organisations in health pandemics: evidence from Covid-19 response in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Disasters. (2021) 12508. doi: 10.1111/disa.12508 [Epub ahead of print].

52. George MD, Danila MI, Watrous D, Reddy S, Alper J, Xie FL, et al. Disruptions in rheumatology care and the rise of Telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in a community practice-based network. Arthritis Care Res. (2021) 73:1153–61. doi: 10.1002/acr.24626

53. Ha BTT, Quang LN, Thanh QP, Duc DM, Mirzoev T, Bui TMA. Community engagement in the prevention and control of COVID-19: insights from Vietnam. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0254432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254432

54. Hutchings OR, Dearing C, Jagers D, Shaw MJ, Raffan F, Jones A, et al. Virtual health care for community management of patients with COVID-19 in Australia: observational cohort study. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e21064. doi: 10.2196/21064

55. Juhn YJ, Wi CI, Ryu E, Sampathkumar P, Takahashi PY, Yao JD, et al. Adherence to public health measures mitigates the risk of COVID-19 infection in older adults: a community-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. (2021) 96:912–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.016

56. Kwok KO, Li KK, Chan HHH, Yi YY, Tang A, Wei WI, et al. Community responses during early phase of COVID-19 epidemic, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. (2020) 26:1575–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200500

57. Lim RHM, Shalhoub R, Sridharan BK. The experiences of the community pharmacy team in supporting people with dementia and family carers with medication management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Soc Adm Pharm. (2021) 17:1825–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.10.005

58. McCalman J, Longbottom M, Fagan S, Fagan R, Andrews S, Miller A. Leading with local solutions to keep Yarrabah safe: a grounded theory study of an Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation's response to COVID-19. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:732. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06761-1

59. McConachie S, Martirosov D, Wang B, Desai N, Jarjosa S, Hsaiky L, et al. Surviving the surge: evaluation of early impact of COVID-19 on inpatient pharmacy services at a community teaching hospital. Am J Health Syst Pharm. (2020) 77:1994–2002. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa189

60. Narasri P, Tantiprasoplap S, Mekwiwatanawong C, Sanongde W, Piaseu N. Management of food insecurity in the COVID-19 pandemic: a model of sustainable community development. Health Care Women Int. (2020) 41:1363–9. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2020.1823984

61. Omboni S, Ballatore T, Rizzi F, Tomassini F, Panzeri E, Campolo L. Telehealth at scale can improve chronic disease management in the community during a pandemic: an experience at the time of COVID-19. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0258015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258015

62. Patel J, Christofferson N, Goodlet KJ. Pharmacist-provided SARS-CoV-2 testing targeting a majority-Hispanic community during the early COVID-19 pandemic: results of a patient perception survey. J Am Pharm Assoc. (2022) 62:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2021.08.015

63. Peng TL, Liu XH, Ni HF, Cui Z, Du L. City lockdown and nationwide intensive community screening are effective in controlling the COVID-19 epidemic: analysis based on a modified SIR model. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0238411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238411

64. Pruitt Z, Chapin KP, Eakin H, Glover AL. Telehealth during COVID-19: suicide prevention and American Indian communities in Montana. Telemed eHealth. (2021) 28:325–33. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2021.0104

65. Vanhamel J, Meudec M, Van Landeghem E, Ronse M, Gryseels C, Reyniers T, et al. Understanding how communities respond to COVID-19: experiences from the Orthodox Jewish communities of Antwerp city. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:78. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01417-2

66. Villani J, Daly P, Fay R, Kavanagh L, McDonagh S, Amin N. A community-health partnership response to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Travellers and Roma in Ireland. Global Health Promot. (2021) 28:46–55. doi: 10.1177/1757975921994075

67. Wallis G, Siracusa F, Blank M, Painter H, Sanchez J, Salinas K, et al. Experience of a novel community testing programme for COVID-19 in London: lessons learnt. Clin Med. (2020) 20:e165. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0436

68. Wong SC, Leung M, Tong DWK, Lee LLY, Leung WLH, Chan FWK, et al. Infection control challenges in setting up community isolation and treatment facilities for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): implementation of directly observed environmental disinfection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2021) 42:1037–45. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.1355

69. Zhang XM, Zhou HE, Zhang WW, Dou QL, Li Y, Wei J, et al. Assessment of coronavirus disease 2019 community containment strategies in Shenzhen, China. JAMA Network Open. (2020) 3:e2012934. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12934

70. Zhu W, Li X, Wu Y, Xu C, Fang S. Community quarantine strategy against coronavirus disease 2019 in Anhui: an evaluation based on trauma center patients. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 96:417–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.016

71. Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2005) 10:45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110

72. Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J Dev Effectiv. (2012) 4:409–29. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2012.710641

73. Elo S, Kyngäsv H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. (2008) 62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

74. Hsieh HF, Sahnnon SE, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

75. Cavanagh S. Content analysis: concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Res. (1997) 4:5–16. doi: 10.7748/nr1997.04.4.3.5.c5869

76. Dey I. Qualitative Data Analysis. A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientists. London: Routledge (1991).

77. Hammersley M. Social Research: Philosophy, Politics and Practice. London/Newbury Park/New Delhi: Sage (1993).

78. Sproule W. Social Research Methods: An Australian Perspective. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press (2006).

79. Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG The The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. (2009) 3:123–30. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

80. Falahi S, Kenarkoohi A. Transmission routes for SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of evidence. New Microbes New Infect. (2020) 38:100778. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100778

81. Yang Y, Shang W, Rao X. Facing the COVID-19 outbreak: what should we know and what could we do? J Med Virol. (2020) 92:536–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25720

82. Lancet T. Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395:1089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30757-1

83. Kuy SR, Tsai R, Bhatt J, Chu QD, Gandhi P, Gupta R, et al. Focusing on vulnerable populations during COVID-19. Acad Med. (2020) 95:e2–3. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003571

84. Anoko JN, Barry BR, Boiro H, Diallo B, Diallo AB, Belizaire MR, et al. Community engagement for successful COVID-19 pandemic response: 10 lessons from Ebola outbreak responses in Africa. BMJ Global Health. (2020) 4:e003121. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003121

85. Gilmore B, Ndejjo R, Tchetchia A, de Claro V, Mago E, Diallo AA, et al. Community engagement for COVID-19 prevention and control: a rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health. (2020) 5:e003188. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003188

86. Bangura MS, Gonzalez MJ, Ali NM, Qiao YL. A collaborative effort of China in combating COVID-19. Global Health Res Policy. (2020) 5:47. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00174-z

87. Nutbeam D. The vital role of meaningful community engagement in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Res Pract. (2021) 31:e3112101. doi: 10.17061/phrp3112101

88. Mofijur M, Fattah IMR, Alam MA, Islam ABMS, Ong HC, Rahman SMA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the social, economic, environmental and energy domains: lessons learnt from a global pandemic. Sustain Prod Consumption. (2021) 26:343–59. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2020.10.016

89. Yeyati, EL, Filippini, F. Social and Economic Impact of COVID-19. Available online at: http://www.brookings.edu/research/social-and-economic-impact-of-covid-19/ (accessed February 10, 2022).

90. Asahi K, Undurraga E A, Valdés R, Wagner R. The effect of COVID-19 on the economy: evidence from an early adopter of localized lockdowns. J Global Health. (2021) 11:05002. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.05002

91. Chowdhury R, Luhar S, Khan N, Choudhury SR, Matin I, Franco OH. Long-term strategies to control COVID-19 in low and middle-income countries: an options overview of community-based, non-pharmacological interventions. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:743–8. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00660-1

92. Das S, Ghosh P, Sen B, Pyne S, Mukhopadhyay I. Critical community size for COVID-19: a model based approach for strategic lockdown policy. Stat Appl. (2020) 18:181–96. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2004.03126

93. Nachega JB, Ashraf G, Hassan M, Geoffrey F, Wolfgang P, Oscar K, et al. From easing lockdowns to scaling-up community-based COVID-19 screening, testing, and contact tracing in Africa - shared approaches, innovations, and challenges to minimize morbidity and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 72:327–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa695

94. Citizen Health Section of HIDA City. Covid-19 Infection Information: Please Use the Action Sheet. Available online at: https://www.city.hida.gifu.jp/site/corona/21389.html (accessed June 12, 2020).

95. Jack, G. No Smartphone? No Problem. Singapore Rolls Out Coronavirus Contract-Tracing Device for Seniors. Available online at: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/29/asia/tracetogether-tokens-singapore-scli-intl/index.html. (accessed June 29, 2020).

96. Hatamian M, Wairimu S, Momen N, Fritsch L. A privacy and security analysis of early-deployed COVID-19 contact tracing Android Apps. Emp Software Eng. (2021) 26:36. doi: 10.1007/s10664-020-09934-4

97. Faraj S, Renno W, Bhardwaj A. Unto the breach: what the COVID-19 pandemic exposes about digitalization. Inform Org. (2021) 31:100337. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2021.100337

98. Fisher D, Wilder-Smith A. The global community needs to swiftly ramp up the response to contain COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395:1109–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30679-6

99. Sroka T. Home quarantine or home isolation during the Covid-19 pandemic as a deprivation of liberty under Polish Law. Med Law Soc. (2021) 14:173–88. doi: 10.18690/mls.14.2.173-188.2021

100. Manzar MD, Pandi-Perumal SR, Bahammam AS. Lockdowns for community containment of COVID 19: Present challenges in the absence of interim guidelines. J Nat Sci Med. (2020) 3:318–21. doi: 10.4103/JNSM.JNSM_68_20

101. Marais BJ, Sorrell TC. Pathways to COVID-19 community protection. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 96:496–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.058

102. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Mitigation Framework. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/community-mitigation.html (accessed October 29, 2020).

103. Ali A, Ahmed M, Hassan N. Socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from rural mountain community in Pakistan. J Public Affairs. (2020) 19:e2355. doi: 10.1002/pa.2355

104. Aw SB, Teh BT, Ling GHT, Leng PC, Chan WH, Ahmad MH. The COVID-19 pandemic situation in Malaysia: lessons learned from the perspective of population density. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:6566. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126566

105. Daras K, Alexiou A, Rose TC, Buchan I, Taylor-Robinson D, Barr B. How does vulnerability to COVID-19 vary between communities in England? Developing a small area vulnerability index (SAVI). J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2021) 75:729–34. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215227

106. Xu W, Xiang LL, Proverbs D, Xiong S. The influence of COVID-19 on community disaster resilience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:88. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010088

107. Lauriola P, Martín-Olmedo P, Leonardi GS, Bouland C, Verheij R, Dückers MLA, et al. On the importance of primary and community healthcare in relation to global health and environmental threats: lessons from the COVID-19 crisis. BMJ Global Health. (2021) 6:e004111. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004111

108. Bettany-Saltikov J. How to Do a Systematic Literature Review in Nursing: A Step-by-Step Guide. London: McGraw-Hill Education (2016).

109. Ridley D. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students. Los Angeles/London/New Delhi/Singapore/Washington, DC: Sage (2012).

110. Thomé AMT, Scavarda LF, Scavarda AJ. Conducting systematic literature review in operations management. Prod Plan Control. (2016) 27:408–20. doi: 10.1080/09537287.2015.1129464

Keywords: COVID-19, community, responses, epidemic prevention, global experience

Citation: Wu Y, Zhang Q, Li M, Mao Q and Li L (2022) Global Experiences of Community Responses to COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Public Health 10:907732. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.907732

Received: 30 March 2022; Accepted: 17 June 2022;

Published: 19 July 2022.

Edited by:

Zisis Kozlakidis, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), FranceReviewed by:

Mingming Liang, Anhui Medical University, ChinaAl Asyary, University of Indonesia, Indonesia

Copyright © 2022 Wu, Zhang, Li, Mao and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Quan Zhang, emhhbmdxdWFucmVzZWFyY2hAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Yijin Wu

Yijin Wu Quan Zhang2,3*

Quan Zhang2,3*