- 1Department of Psychology, California State University, Long Beach, CA, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, Fordham University, New York City, NY, United States

- 4The WorkPlace Group, Florham Park, NJ, United States

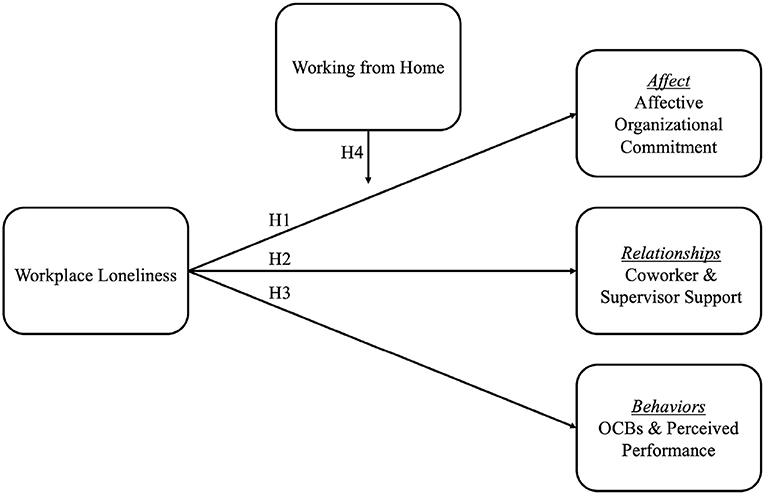

Self-determination theory posits that relatedness and autonomy are two drivers of work-relevant outcomes. Through the lens of this theory, the current study explored the potential interactive effects of relatedness and autonomy on affective, relational, and behavioral outcomes at work, operationalizing relatedness as workplace loneliness and autonomy as the ability to work from home. To test this relation, survey-based data from a sample of 391 working adults were collected and a path analysis was carried out. Results suggested that workplace loneliness negatively predicts affective organizational commitment, perceptions of coworker and supervisor support, organizational citizenship behaviors, and perceived performance. Furthermore, results suggested that workplace loneliness and working from home have an interactive effect on affective organizational commitment, perceptions of coworker support, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Specifically, working from home had a beneficial impact on the relation between workplace loneliness and affective organizational commitment/perceptions of coworker support, but a detrimental impact on the relation between workplace loneliness and organizational citizenship behaviors. These results add to the extant body of scholarly work of Self-Determination Theory by testing the theory in the post-pandemic context of working from home. In addition, these results have practical implications for managers, who should strive to create opportunities for employees who work from home to enact organizational citizenship behaviors.

Workplace Loneliness: The Benefits and Detriments of Working From Home

Due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, estimates of the number of U.S. employees working from home—either part- or full-time—have ranged from 58% (1) to 71% (2). These figures suggest that the proclivity of American workers to work from home has at least doubled, and has possibly nearly quadrupled, since prior to the onset of the pandemic (2, 3). This rapid and drastic change in worker demographics poses a number of questions about the efficacy and implications of working from home.

Prior literature has suggested a number of potential detriments to working from home. For instance, research has indicated that individuals who work from home experience increased levels of stress, irritability, worry, and feelings of guilt when compared to other workers (4). Other scholarly evidence has suggested that working from home reduces happiness (5). However, there have also been positive implications of working from home in the scholarly literature. For example, demographic research by the Pew Research Foundation has shown that over half of individuals would prefer to continue working from home after the pandemic has concluded (2), suggesting that there may be perceived benefits to working from home. Some research has even suggested that working from home may lead to performance increases (6).

The COVID-19 pandemic has also impacted experiences of loneliness. Recent research has suggested that the pandemic has significantly increased self-reported loneliness, particularly among people who were under orders to stay at home (7). In particular, workplace loneliness—or, the feeling that one's social needs are not being met at work (8)—is important to consider in the context of working from home. Traditionally, working from home has been shown to increase feelings of loneliness (4), although this finding has yet to be replicated during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, as far as the authors are aware. Workplace loneliness has also been shown to have a detrimental impact on critical, work-relevant outcomes such as performance (8).

Both workplace loneliness and working from home can be viewed via the lens of self-determination theory [SDT; (9)], which states that individuals are motivated at work by relatedness and autonomy. Relatedness, or the need to feel connected to others, is a facet of SDT that workplace loneliness maps on to, whereas autonomy, or the need to feel in control of one's own life, is a facet of SDT that working from home maps on to. Thus, an open question is whether workplace loneliness might interact with the experience of working from home. As far as the authors are aware, there is no extant literature on this topic, as of yet. Will working from home mitigate any negative impacts that loneliness has on work-relevant outcomes, or will it exacerbate them?

Contributions of the Current Study

The current study sought to make three contributions to the literature. First, from prior research we know that SDT (9) applies to human motivation in a number of different contexts [e.g., (10–13)]. However, limited work has been done on SDT in the context of working from home, which is of concern because of the recent spike in working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Accordingly, this paper addresses this concern by examining this novel application of SDT, which will contribute to the literature by extending SDT to an increasingly common modality of work—namely, working from home.

Second, the extant literature has explored the outcomes of general loneliness in substantial depth, but has focused less on the repercussions of workplace loneliness, specifically. This gap in the literature is problematic because, just like general loneliness [e.g., (14)], workplace loneliness has the potential to have a measurable, detrimental impact on individual outcomes. Thus, the current study contributes to the literature by investigating the impact of workplace loneliness on a variety of work-relevant outcomes, clarifying these relationships for both scholars and practitioners to ground future work in.

Finally, the potential interactive effect workplace loneliness and working from home on work-relevant outcomes has yet to be thoroughly investigated in the extant literature. This potential relation is of particular importance to explore given the fact that, as previously stated, working from home is increasingly common in the post-pandemic era. Accordingly, the current paper contributes to the literature by unpacking the potential moderating impact of working from home on the aforementioned relations between workplace loneliness and outcomes, which may help guide future scholarly and applied work.

Workplace Loneliness

Loneliness is defined as a perceived deficit in one's desired social relations. A common misconception about loneliness is that it occurs due to an insufficient number of personal relationships, when in fact it relates more closely to a dearth of high-quality relationships. Rather than being solely related to the number of relationships a person has, loneliness most closely reflects whether or not one has achieved their desired amount of quality contact, no matter how many or few people that may require (15).

Workplace loneliness is the feeling that one's social needs are not being met at work (8), and is often conceptualized as having two distinct facets: emotional deprivation and social companionship. Emotional deprivation is defined as a failure to emotionally connect with or attach to others, and can lead to a variety of undesirable workplace outcomes such as a drop in organizational citizenship behaviors and performance (16). Social companionship is the connection to and engagement with a network of people (17–19), and has been shown to positively predict affective organizational commitment and negatively predict the intention to seek new employment (20). Social companionship has also been shown to predict both intrinsic and extrinsic forms of job satisfaction (21).

Prior research has indicated that workplace loneliness is impacted by a number of factors. For example, a meta-analysis of the loneliness literature found that the extent of one's desire for social relationships at work predicts loneliness at work. This study also reported that individual factors such as social skills predict loneliness at work, because those with a better ability to communicate and socialize with others have more opportunities to develop high-quality, satisfying relationships (22). In a similar vein, social information processing and social skills have been shown to negatively predict loneliness at work (23). Shyness and introversion also predict loneliness at work, while extraversion serves as a protector against the experience of workplace loneliness (22). Finally, research carried out on prison staff in Turkey revealed that job satisfaction negatively predicts loneliness at work, as well (24).

In terms of work-relevant correlates, loneliness at work has been shown to be positively associated with role conflict—an inability to understand one's role at work—and role ambiguity—not understanding the expectations of one's role at work—and to negatively correlate with opportunities for friendship at work and the perceived quality of workplace friendships (25). Loneliness at work has also been shown to have negative consequences for one's health (26, 27). With regard to mental health, a study of managers across New Delhi found that loneliness at work was negatively associated with psychological well-being and self-esteem. Additionally, managers suffering from loneliness at work reported increased feelings of work alienation (26). Moreover, loneliness appears to have implications for physical well-being. For instance, a study that utilized a sample of over 10,000 individuals across 14 countries found that loneliness predicts developing a work disability (27).

While the literature on specific job types predicting loneliness at work is limited, one type of work that may be associated with increased loneliness at work is temporary work. Compared to their permanent counterparts, temporary workers report higher levels of loneliness at work (28). Furthermore, research on job roles has revealed patterns related to workplace loneliness. Contrary to the truism about it being “lonely at the top,” research has indicated that those in leadership positions (who may not have many peers in the workplace) do not feel any lonelier, on average, than their subordinates with numerous coworkers at the same level (29). Circling back to the definition of workplace loneliness, this finding implies that, although leaders may have less relationships at work, their relationship quality does not suffer.

Working From Home

During the Oil Crisis of 1973, when the worldwide price of oil rose nearly 300% (30), individuals and organizations alike were forced to quickly curtail their oil consumption. Many businesses responded by softening the requirement to commute to/from work, consequently reducing traffic congestion and energy consumption. Eventually, the term telecommuting1—or, the use of “telecommunications technology to partially or completely replace the commute to and from work” [(31), p. 273]—was coined to refer to this practice.

Long after the end of the oil crisis, companies have continued to embrace the practice of working from home, which simultaneously helps to manage work-home relations and satisfy both the Clean Air Act and the ADA requirements (32). Work-from-home arrangements also reduce employer's overhead costs and associated expenses (33); research has shown employers can save about $11,000 a year for every person that works remotely half of the time (34). Telecommuting also has a positive impact on turnover rates, with job attrition rates falling by over 50% (6). Moreover, work-from-home employees appear to work longer hours in order to compensate for time away from work (35).

In contemporary times, with the evolution of technological capabilities and the COVID-19 pandemic, working from home has become a “new normal” (36). For example, Facebook is planning for permanent remote workers and stated that within a decade as many as half of the company's more than 48,000 employees would work from home (37). Other large companies such as Google, Microsoft, and Apple are expected to follow suit (38).

Several studies have noted a positive relationship between productivity and telecommuting (39–43). In line with this finding, IBM has also noted that the productivity rate for telecommuters is 10 to 20 percent higher than their office-based workers (41). Telecommuting has been shown to do more than just help the employer's bottom line, however; it also has a positive impact on employee outcomes. For instance, research has shown that telecommuters experience less stress, less work-life conflicts, higher work engagement, and increased job performance when compared with their counterparts in the office (42, 44). Furthermore, research has indicated that the option to choose when and where to work is positively correlated with work engagement and negatively correlated with exhaustion, potentially because of more effective and efficient electronic communication with co-workers (45).

Contrasting with the benefits of working from home, many studies have observed higher levels of loneliness among telecommuters in comparison to non-telecommuters (4, 46–49). For example, a study by Mann and Holdsworth (4) found that 67% of telecommuters reported loneliness, whereas loneliness was not reported by any of the traditional, non-telecommuting workers who were surveyed. Other work has suggested that individual differences may impact experiences of workplace loneliness; for instance, telecommuting mothers have been shown to report higher levels of loneliness than telecommuting fathers (48).

The Application of Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory [SDT; (9)] states that human beings have three innate categories of psychological need that serve to motivate them: a) competence, or the need to feel capable, b) autonomy, or the need to feel in control of one's life, and c) relatedness, or the need to feel connected to others. Specifically in terms of relatedness needs, research on SDT has shown that a lack of fulfillment may result in a variety of outcomes. For instance, variations in assessments of relatedness throughout the course of the day have been shown to map onto experienced emotions (12, 13). Moreover, research has suggested that relatedness needs are closely associated with actual relationship quality, above and beyond the impact of competence and/or autonomy (10, 12). Finally, perceptions of relatedness have been shown to impact the way that individuals behave, including executing prosocial behaviors (11).

The current study focuses on the impact that a dearth in relatedness has on work-relevant outcomes; loneliness is, by definition, a lack of fulfillment in terms of relatedness, as lonely individuals sense that their current social relationships do not fulfill them adequately. Thus, in order to investigate the potential impacts of workplace loneliness, we chose to map our explored correlates of loneliness onto the preexisting pattern of correlates for SDT relatedness needs. Accordingly, we chose to emphasize the following three workplace experiences: a) affect, b) relationships, and c) behaviors.

Workplace Loneliness and Individual Affect

Work-relevant affect refers to one's moods and emotions while at the workplace. Affect can be either positive (enthusiastic, alert, excited) or negative (distressed, fearful, nervous) (50). Affect is of importance to employers, as it can have an impact on everyday business practices. For instance, both individuals and groups have been shown to exhibit increased prosocial and helping behaviors when reporting better moods (51). Positive affect at work has also been shown to positively correlate with performance (52). Furthermore, affect has also been found to predict turnover intentions; positive mood acts to protect against turnover whereas negative affect promotes turnover intentions (53).

Affective organizational commitment, as conceptualized by Allen and Meyer (54), is the affective and emotional attachment one has to their organization such that the individual identifies with, is involved in, and enjoys membership in the organization. Affective organizational commitment is a particularly important form of affect to investigate because it is associated with a variety of workplace outcomes. For example, affective commitment is negatively predictive of turnover intent and positively predictive of job performance (55, 56), and is also positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviors (57).

From the lens of SDT, a lack of relatedness has been shown to be related to emotional processes at the individual level. For example, research has shown that lacking satisfaction in terms of relatedness needs is negatively associated with emotional intelligence (58) and also impacts experienced emotions throughout the course of the day (12, 13). When specifically considering a lack of fulfillment of relatedness needs at work, there also appears to be a connection with affect. Loneliness at work has been shown to negatively predict affective organizational commitment (20, 26, 59), potentially because lonely employees are more detached from colleagues. As aforementioned, loneliness at work consists of two dimensions: emotional deprivation and a lack of social companionship (19). Increased feelings of insufficient social companionship at work are negatively correlated to employees' affective commitment (20). However, other research has indicated that both the emotional deprivation and social companionship facets of workplace loneliness have a negative impact on affective organizational commitment (59). Consequently, based on SDT and the aforementioned research results, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Loneliness at work will negatively predict affective organizational commitment.

Workplace Loneliness and Relationships With Colleagues

Workplace relationships are interpersonal relationships characterized by continuous, patterned social interactions between individuals at work. Nearly all businesses require daily social interaction and strong workplace relationships in order to function properly (60). Relationships are especially important to consider in the context of the workplace, as they affect workplace attitudes and performance. For instance, quality leader-subordinate relationships have been shown to promote information retention and protect against turnover intention (61, 62). Additionally, satisfaction with one's workplace relationships is negatively associated with individual strain, such as depression and frustration, at work (63).

There are two primary types of workplace relationships that have been shown to have critical implications for workplace functioning: those with peers and those with supervisors. Two common measures of these relationships are perceptions of coworker support (64) and supervisor support (65), respectively. In terms of coworker support, research has indicated that it is positively predictive of workplace creativity and negatively predictive of turnover intentions (66–68). Coworker support can also protect against the stressors of mistreatment by one's supervisor or organization, positively moderating the relationship between a reduction in work stress and job satisfaction (69). Studies have also shown that coworker support can serve to mollify the effects of emotional exhaustion that workers experience due to work overload [e.g., (66)]. Like coworker support, supervisor support has numerous work-relevant consequences. For example, supervisor support predicts creative work output (68, 70). Supervisor support also drives a number of additional work outcomes, including organizational commitment, employee performance, and job satisfaction, and turnover intentions (68, 71, 72).

From an SDT perspective, fulfillment of relatedness needs has been shown to be related to actual relationship quality (10, 12). In the specific context of the workplace, this connection between relatedness and relationships with coworkers also seems to hold true. Loneliness at work can be explained, in part, due to a dearth of high-quality relationships at work. In line with this notion, insufficient support from colleagues has been shown to be a strong contributor to a feeling of loneliness at work (19). Better-quality relationships with supervisors also lead to lower levels of loneliness at work (16, 73). Specifically, a lack of support from supervisors can result in feelings of suspicion and fear that serve to promote workplace loneliness (73). Other research has demonstrated that certain leadership styles, such as paternal approaches to leadership, are associated with decreased levels of workplace loneliness (74). Overall, the research trends point to a negative relationship between loneliness at work and both supervisor and coworker support. Accordingly, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 2: Loneliness at work will negatively predict a) coworker and b) supervisor support.

Workplace Loneliness and Behavioral Outcomes

Employee behavior has the potential to have a measurable impact on outcomes at the organization level. Two types of behavior that have been shown to be particularly influential are task and contextual performance. First, task performance is conceptualized as an individual's productivity at work, comprising both the accuracy and efficiency with which individuals carry out assigned tasks (75). Workplace performance is important to understand because it can be impacted by a multitude of variables including, but not limited to, the physical environment, supervisor support, coworker support, and loneliness at work (8, 16, 76). On the other hand, contextual performance—also known as organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs)—constitute any contributions to the organization or work community that are not required of employees (77). OCBs are necessary to any workplace or business because of the potential consequences these behaviors have on performance; research has shown that higher amounts of organizational citizenship behaviors often result in increased performance volume and quality (78).

From the literature on SDT, a lack of relatedness can lead to alterations in individuals' behavior (11). This pattern also appears to hold true in the workplace, as loneliness at work has been shown to negatively correlate with job performance (8, 79). Self-evaluations as well as peer and supervisor evaluations have revealed those who are lonelier at work to have lower performance ratings (80). Loneliness at work may also indirectly predict worse job performance by mediating the relation between work alienation and job performance (81). Results of similar research have suggested that loneliness at work leads to reduced job satisfaction and, consequently, decreased performance (21). Although the authors are not aware of any research connecting workplace loneliness and organizational citizenship behaviors, we expect that a similar pattern will emerge. Accordingly, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Loneliness at work will negatively predict a) organizational citizenship behaviors and b) perceived performance.

Working From Home as a Moderator

One of the benefits of working from home is increased worker autonomy (82); some scholars even refer to working from home as locational autonomy [e.g., (83)]. Through the lens of SDT (9), working from home exemplifies autonomy, which is another theorized area of psychological need.

Extant research suggests that autonomy brings about positive, affective responses in people of all ages (84). Autonomy has also been shown to positively correlate with social functioning (85). Finally, autonomy has been shown to positively impact behavioral outcomes; for instance, autonomy has been linked to the enactment of prosocial behaviors (86).

Accordingly, we believe that autonomy will moderate the relation between workplace loneliness and work-relevant outcomes. Although a dearth of fulfillment of relatedness needs is expected to have a deleterious impact on emotions, relationships, and behaviors, it also stands to reason that fulfillment of autonomy needs may mitigate that harmful effect. Thus, we expect that working from home (autonomy) will mollify the relationship between workplace loneliness (lack of relatedness) and affective, relational, and behavioral work outcomes. As such, we posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Working from home will moderate the relation between workplace loneliness and a) affective, b) relational, and c) behavioral outcomes, such that the deleterious impact of loneliness on outcomes will be less pronounced for individuals who work from home.

For a visual rendition of our full theoretical model, please see Figure 1.

Methods

The current study employed a quantitative, survey-based, cross-sectional methodology, the details of which are described below. All data were collected using Qualtrics (87), a software survey system.

Participants

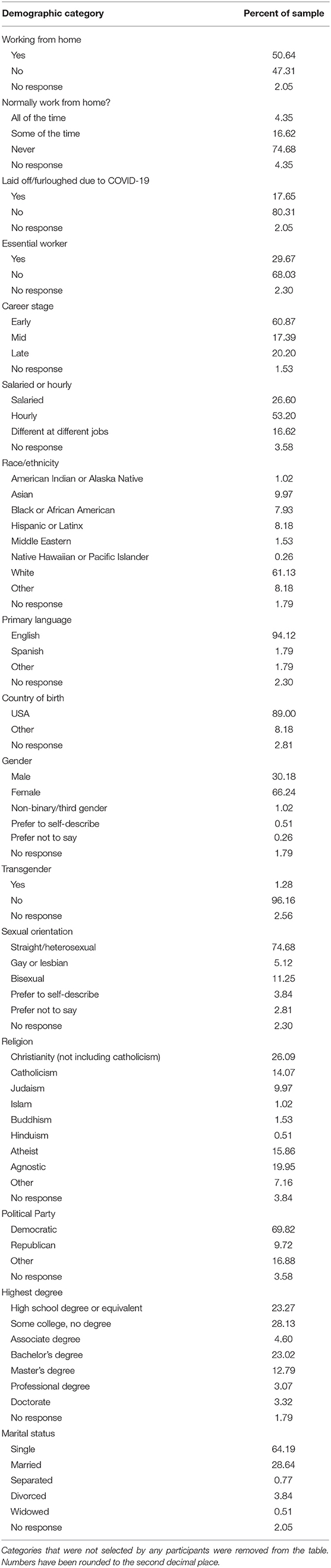

Five-hundred and sixty-one survey responses were received. Of these responses, 391 completed surveys were usable for analyses. Responses that were eliminated from the final sample included: individuals who didn't respond to any questions (n = 92), individuals who were unemployed and had never previously been employed (n = 51), individuals who did not provide consent for their data to be used (n = 15), responses that came from the research group testing out the survey (n = 11), and one response that, based on respondent location and pattern of answers, appeared to be a duplicate response (n = 1). Of the 391 usable data points, 100% of individuals were currently employed or had previously been employed. Participants reported working in a variety of industries, including education (18.93%), dining (11.25%), sales (9.21%), healthcare (9.21%), business (7.93%), and administration (6.39%). The average age of the sample was 32.41 years (SD = 15.90). Please see Table 1 for additional information on participant demographics.

Procedure

The population of interest in this study was employed, American adults. In order to derive a sample from that population, participants were primarily recruited to complete a web-based survey from a database of U.S. job candidates from a talent acquisition and development consulting company, but also partially from an alumni network from a small, liberal arts college in Southern California and social media posts. From the database of U.S. job candidates, 33,140 candidates were contacted via a personalized email with a link to the survey. These individuals were selected based on the following criteria: a) residing in the United States, b) having updated their candidate record within the past 5 years, and c) having a valid email address. The job candidates in the database include individuals who work in a variety of industries such as manufacturing, finance, health, pharmaceuticals, consumer products, IT, and engineering. These candidates range from no work experience to those who are mid- and late-career professionals. This database includes individuals in both trade as well as professional occupations.

Measures

The following measures were used to capture conceptual variables in the current study. Survey items were not adapted or modified in any way.

Workplace Loneliness

Workplace loneliness was measured using Wright et al. (88) 16-item scale. An example item is as follows: “I often feel isolated when I am with my coworkers.” Response options ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.93.

Affective Organizational Commitment

Affective organizational commitment was captured using Allen and Meyer's (54) eight-item scale. An example item is as follows: “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.” Response options ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.86.

Coworker and Supervisor Support

Perceptions of coworker support were captured using O'Driscoll et al. (64) four-item scale. An example item is as follows: “How often, over the past 3 months, have you received sympathetic understanding and concern from colleagues?” Response options ranged from “never” (1) to “all the time” (6). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.92.

Perceptions of supervisor support were captured using Kottke and Sharafinski (65) 16-item scale. An example item is as follows: “My supervisor really cares about my well-being.” Response options ranged from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.96.

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

OCBs were measured using Smith et al. (77) 16-item scale. Participants were instructed to respond about their own behavior. An example item is as follows: “Makes innovative suggestions to improve department.” Response options ranged from “very uncharacteristic” (1) to “very characteristic” (5). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.79.

Job Performance

Perceived job performance was measured using Bal and De Lange (89) 3-item scale. An example item is as follows: “How would you rate your job performance, as an individual employee?” Response options ranged from “very poor” (1) to “excellent” (5). Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.84.

Demographics

Work-related and social demographics were measured by asking participants to self-report their demographic categories. Please see Table 1 for detailed information on the demographic items that participants responded to. In addition to the items listed in Table 1, we also asked participants to self-report their age, current employment status, and employment industry.

Covariates

General loneliness, which was included in analyses as a covariate, was measured using Rubenstein and Shaver (90) eight-item scale. An example item is as follows: “I am a lonely person.” All questions utilized Likert-type response formats, although the number of response options and scale points varied from question to question. Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.88.

Results

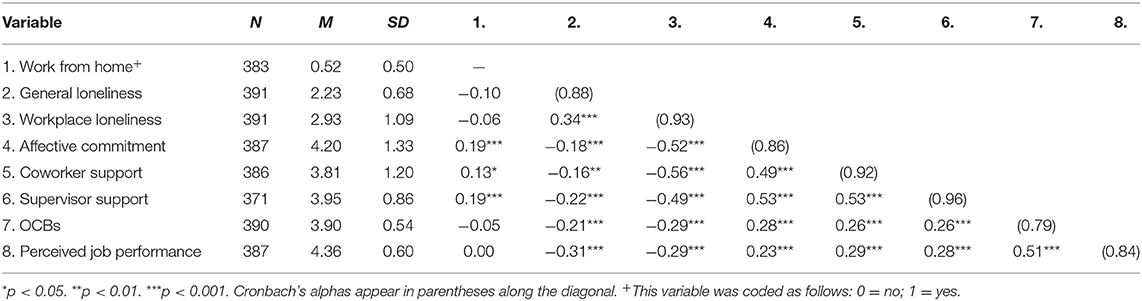

All measured variables were deemed to be normally distributed. Descriptive statistics and Pearson's correlations were calculated for all of the study's primary variables, in addition to alphas coefficients, which were all deemed to be acceptable based on the standard academic interpretation of this statistic (91). These results can be seen in Table 2. Notably, loneliness at work and working from home were not significantly correlated with one another.

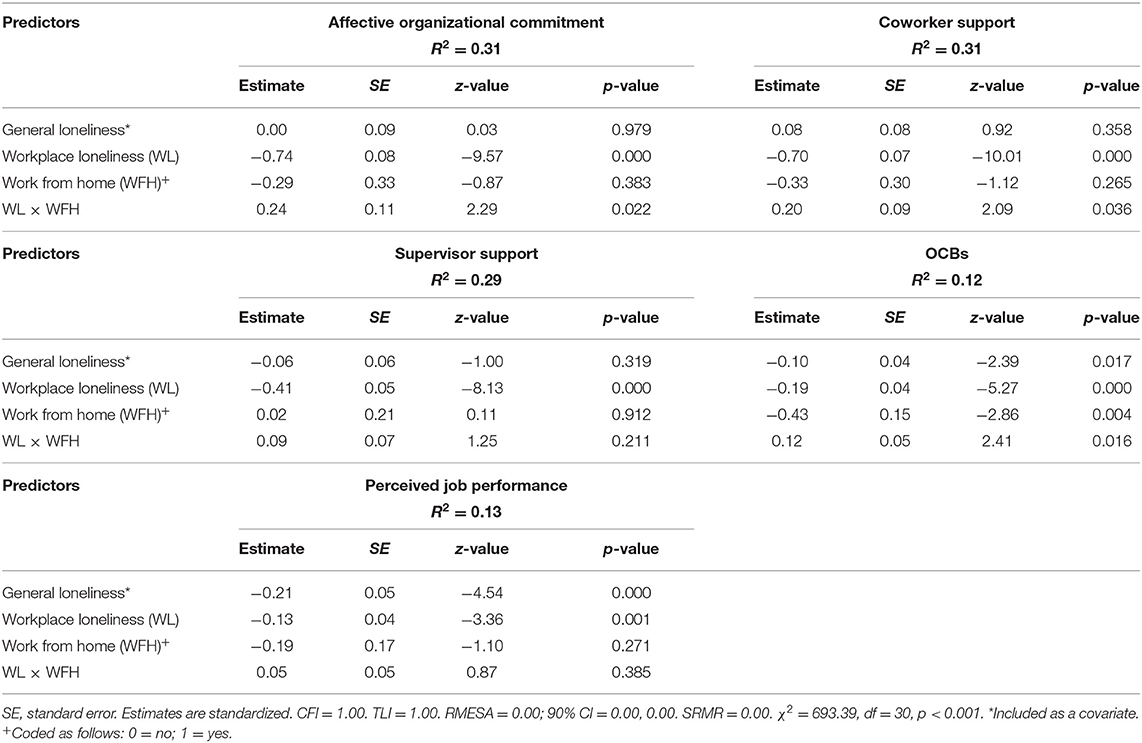

Next, in order to test Hypotheses 1 through 4, a single path analysis was run. General loneliness was included as a control variable, in order to ensure that the pattern of results was driven by workplace loneliness, specifically. Detailed results of this path analysis can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Path analysis regressing affective organizational commitment, coworker support, supervisor support, OCBs, and perceived job performance on workplace loneliness, working from home, and their interaction (N = 362).

First, in order to test Hypothesis 1—which posited that loneliness at work would negatively predict affective organizational commitment—affective organizational commitment was regressed onto loneliness at work. Results suggested that loneliness at work negatively predicts affective organizational commitment (estimate = −0.74, p < 0.001). Accordingly, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Second, in order to test Hypothesis 2a—which posited that loneliness at work would negatively predict coworker support—coworker support was regressed onto loneliness at work. Results suggested that loneliness at work negatively predicts coworker support (estimate = −0.70, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 2a was supported.

Third, in order to test Hypothesis 2b—which posited that loneliness at work would negatively predict supervisor support—supervisor support was regressed onto loneliness at work. Results suggested that loneliness at work negatively predicts supervisor support (estimate = −0.41, p < 0.001). Accordingly, Hypothesis 2b was supported.

Fourth, in order to test Hypothesis 3a—which posited that loneliness at work would negatively predict OCBs—OCBs were regressed onto loneliness at work. Results suggested that loneliness at work negatively predicts OCBs (estimate = −0.19, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 3a was supported.

Fifth, in order to test Hypothesis 3b—which posited that loneliness at work would negatively predict perceived performance—perceived performance was regressed onto loneliness at work. Results suggested that loneliness at work negatively predicts perceived performance (estimate = −0.13, p < 0.01). Accordingly, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

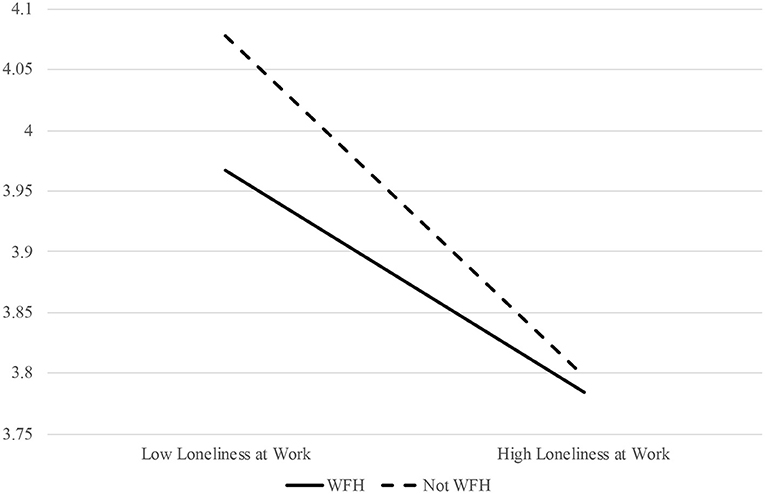

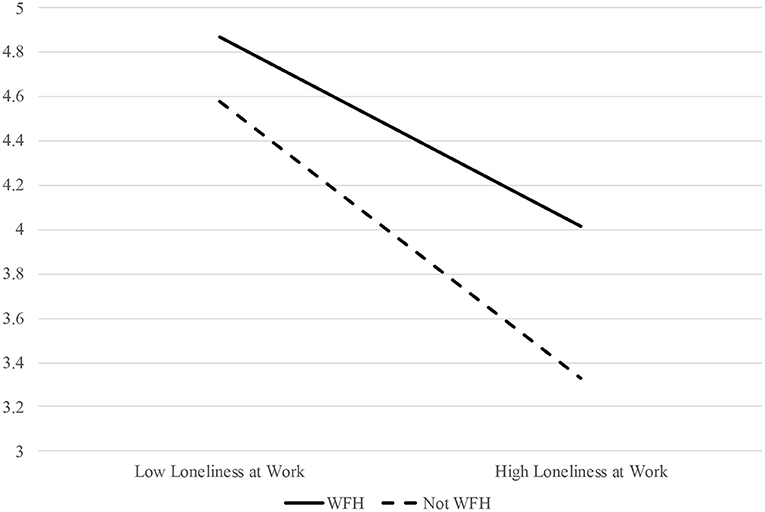

Sixth, in order to test Hypothesis 4a—which posited that working from home would moderate the relation between workplace loneliness and affective outcomes, such that the deleterious impact of loneliness on affective outcomes will be less pronounced for individuals who work from home—the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home was tested as a predictor of affective organizational commitment. Results suggested that loneliness at work and working from home have an interactive effect on affective organizational commitment in the expected direction (estimate = 0.24, p < 0.05). Accordingly, Hypothesis 4a was supported. For a visualization of the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home on affective organizational commitment, please see Figure 2.

Figure 2. The interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home (WFH) on affective organizational commitment.

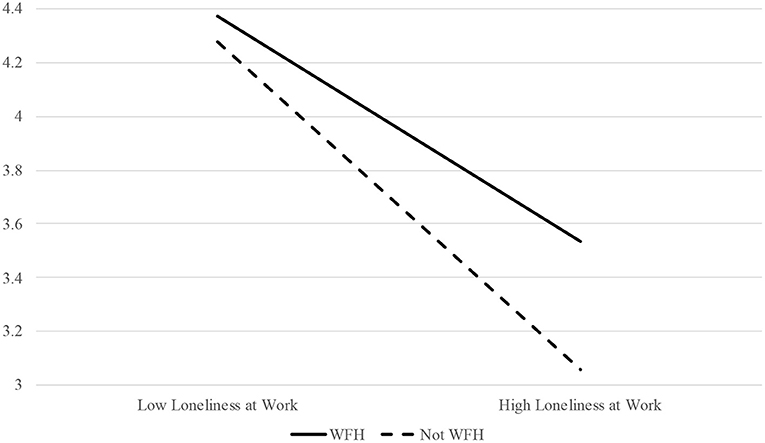

Seventh, in order to test Hypothesis 4b—which posited that working from home would moderate the relation between workplace loneliness and relational outcomes, such that the deleterious impact of loneliness on relational outcomes will be less pronounced for individuals who work from home—the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home was tested as a predictor of coworker and supervisor support. Results suggested that loneliness at work and working from home have an interactive effect on coworker support in the expected direction (estimate = 0.20, p < 0.05) but do not have an interactive effect on supervisor support (estimate = 0.09, ns). Accordingly, Hypothesis 4b was partially supported. For a visualization of the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home on coworker support, please see Figure 3.

Figure 3. The interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home (WFH) on perceived coworker support.

Eighth, in order to test Hypothesis 4c—which posited that working from home would moderate the relation between workplace loneliness and behavioral outcomes, such that the deleterious impact of loneliness on behavioral outcomes will be less pronounced for individuals who work from home—the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home was tested as a predictor of OCBs and perceived performance. Results suggested that loneliness at work and working from home have an interactive effect on OCBs, but not in the expected direction (estimate = 0.12, p < 0.05). However, loneliness at work and working from home did not have an interactive effect on perceived job performance (estimate = 0.05, ns). Accordingly, Hypothesis 4c was not supported. For a visualization of the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home on OCBs, please see Figure 4.

Discussion

The current study explored the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home on a number of work-relevant outcomes, through the theoretical lens of SDT (9). Overall, results suggested that a dearth of relatedness (i.e., workplace loneliness) negatively predicted affective organizational commitment, perceptions of coworker and supervisor support, organizational citizenship behaviors, and perceived performance. Moreover, autonomy (i.e., working from home) partially mitigated the negative effect that workplace loneliness has on perceptions of coworker and supervisor support. Autonomy also was found to buffer the negative relation between lack of relatedness and affective organizational commitment, but it exacerbated the negative relation between lack of relatedness and OCBs. A detailed discussion of these results can be found below.

Summary of Results

Providing support for Hypotheses 1 through 3, our results indicated that loneliness at work negatively predicts affective organizational commitment, perceptions of coworker support, perceptions of supervisor support, OCBs, and perceived performance. In support of Hypothesis 4a, results suggested that working from home moderates the relation between workplace loneliness and affective organizational commitment, such that working from home weakens the deleterious impact of workplace loneliness on affective organizational commitment. In partial support of Hypothesis 4b, results suggested that working from home moderates the relation between workplace loneliness and perceptions of coworker support, such that working from home weakens the deleterious impact of workplace loneliness on perceptions of coworker support. However, working from home did not have a significant moderating impact on the relation between workplace loneliness and perceptions of supervisor support, as was expected. Finally, results suggested that loneliness at work and working from home have an interactive effect on OCBs, but not in the expected direction; working from home strengthened the deleterious impact of workplace loneliness on OCBs. In terms of perceived performance, our results suggested that there was not a significant interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home. Thus, Hypothesis 4c was not supported.

Theoretical Contributions

First, the current paper presents a novel application of SDT (9). While SDT has been demonstrated as an effective theory of motivation in many contexts [e.g., (10–13)], the specific experience of working from home has yet to be thoroughly explored through the lens of SDT. The current paper applied SDT to this context, providing a framework for future researchers to extent this line of thinking in the future.

Second, in terms of direct effects of workplace loneliness, our results suggest a negative relation to affective, relational, and behavioral outcomes. First, workplace loneliness was shown to negatively predict affective organizational commitment, as was hypothesized. This implies that loneliness at work has a measurable impact on the way that employees feel about their employer; less lonely employees feel more connected and committed to their employer, and vice versa. Second, workplace loneliness negatively predicted perceptions of both coworker and supervisor support. This finding reaffirms extant literature on the linkage between coworker relationships and loneliness, which has also shown that the two are negatively correlated with one another (19). Finally, workplace loneliness negatively predicted both of the behaviors that were measured in this study: organizational citizenship behaviors and perceived performance. The negative relation between loneliness at work and perceived performance is of particular interest, since perceived performance can be thought of as an operationalization of competence, the third type of psychological need delineated by SDT (9). So, our results also support the notion that relatedness and competence are interrelated needs, a finding that has been demonstrated in previous literature [e.g., (12)].

Finally, in line with our hypotheses, workplace loneliness and working from home had an interactive effect on both affective organizational commitment and perceptions of coworker support, such that very lonely people were more committed to their organizations and perceived their coworkers as more supportive when they worked from home as opposed to not. So, in line with SDT (9), it seems that fulfillment of autonomy needs buffers the negative impact that lack of fulfillment of relatedness has on affective and relational work outcomes.

Contrary to our hypothesis, however, workplace loneliness and working from home had an interactive effect on OCBs such that people who did not work from home tended to engage in more OCBs than people who did, and this was especially true for people who were less lonely. This result suggests that working from home takes a toll on the ability of workers to enact OCBs. Logistically, this finding makes sense; many OCBs hinge on in-person interaction, such as noticing that a colleague needs help and pitching in to assist. In support of this notion, research from the era of the COVID-19 pandemic has indicated that employees are seemingly less prone to engaging in behaviors that emerge most readily in face-to-face contexts; for instance, collective action (92).

Finally, workplace loneliness and working from home did not have an interactive effect on perceptions of supervisor support or perceived performance. So, while our results suggest that lack of relatedness (workplace loneliness) and autonomy (working from home) have an interactive impact on certain affective, relational, and behavioral work-relevant outcomes, these interactive impacts did not apply to all variables that we measured in the current study. One possible explanation for this pattern of results is that perceptions of supervisor support and perceived performance are particularly resilient to the impact of working from home. In other words, regardless of whether individuals are working from the office or home, the relation between workplace loneliness and perceptions of supervisor support/perceived performance are similar, implying that the impact that loneliness has on these outcomes may not be mitigated by the location where work takes place.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that we would like to broach. First, the current study is cross-sectional in nature, which limits our ability to make causal inferences. In fact, we urge readers not to draw causal inferences of any kind based off of the current study, due to the fact that our design is not conducive to inferring cause and effect. Second, our study is subject to the mono-method bias. Because our results are entirely based off of self-report, survey-based data, it is possible that effect sizes have been artificially aggrandized.

Third, our sample may have issues of generalizability. As seen in Table 1, while our sample was diverse in many ways, it was not entirely reflective of the larger U.S. population of working adults. So, these results may not generalize to all people in all places. Fourth, perceived job performance is a relatively weak measure of performance, since it is subject to the social desirability bias. In other words, because performance was self-reported, results related to performance may not be accurate.

Finally, the current study did not measure working from home as a continuous variable, and also did not capture degree of interaction with colleagues whilst working from home. Both of these metrics would be an interesting direction for future researchers to capture, in terms of their operationalization of working from home and assessment of covariates.

Future Directions

In terms of future directions that are based off of the current study's limitations, we recommend that future researchers endeavor to study the interactive effect of workplace loneliness and working from home on work-relevant outcomes using longitudinal, multi-methodological research designs with large, diverse samples of workers. We also recommend that, for future studies that focus on performance as an outcome, researchers collect relatively objective measures of performance.

In addition, future researchers should venture to explore whether the experiences of people who work from home are fundamentally different during a global pandemic vs. not. Is the COVID-19 pandemic driving the current study's results, either fully or in part? Moving forward, collecting data for purposes of comparison, during and after the pandemic, would help to shed light on this question. Furthermore, we suggest that future researchers explore working from home as a continuous rather than a categorical variable. In reality, working from home is a spectrum; thus, one avenue for future work would be to operationalize this variable as such, and glean results accordingly.

We also suggest that future researchers investigate cross-compare experiences of workplace loneliness in virtual organizations (i.e., organizations where all employees work remotely) as compared with traditional organizations. Does it matter where the majority of workers work from? With many large employers suggesting that half of their workforce may continue to work from home post-pandemic, researchers will have unique opportunities to explore the dynamics of organization, work, and job design on workplace loneliness and its effect on workplace outcomes.

Applied Implications

With statistically significant negative correlations between loneliness at work and affective organizational commitment, coworker support, supervisor support, OCBs, and perceived job performance (see Table 2), strategies to minimize loneliness at work are strongly recommended, as employers who mitigate workplace loneliness will potentially reduce employee turnover and increase OCBs and job performance. The current study found that less lonely employees have higher levels of affective organizational commitment, signifying that tackling workplace loneliness will reduce employee turnover and the costs of recruiting and training replacements.

Accordingly, we recommend that employers strategically nurture positive, supportive relationships among coworkers and supervisors, as this may reduce loneliness in the workplace. This can be done by facilitating relationship-building amongst employees via interventions such as team building, networking events, or structured social hours. While it may seem that employees spending time at work focusing on activities that are not directly work-relevant would hurt organizational productivity, the results of the current study demonstrate just the opposite; less lonely employees end up with the best outcomes for themselves and the organization as a whole, and these employees are the same people who likely carved out time at work to develop high-quality relationships. In creating opportunities for relationships between coworkers to develop, employers should focus on the quality of the relationships that employees build with one other rather than the number of relationships. Strong, supportive, high-quality relationships with coworkers and supervisors are the bonds that mitigate loneliness.

The current study also found that loneliness at work is not tied to where a person works; employees working from home were just as lonely as those working from corporate offices. However, those working from home reported higher affective organizational commitment and coworker/supervisor support levels than those who did not, suggesting that it may be better to be lonely working from home than from a corporate office. That being said, we caution the reader not to overgeneralize this observation. The COVID-19 pandemic created unique work-from-home circumstances where employees had to redesign their jobs and workflows in order to do from home what they once did from corporate offices. With many people working exclusively from home during the pandemic, coworkers may be more likely to initiate frequent calls and web-based meetings with each other to get work done. Consequently, these unique circumstances may have increased coworker interactions, perceived levels of coworker and supervisor support, and lowered feelings of loneliness. Overall, our results suggest that workplace loneliness is not dependent on where an employee works but rather on the quality of their relationships with peers and supervisors.

Finally, employers need to facilitate ways for employees to make OCB-type contributions to the workplace from home. The current study found that the negative relation between workplace loneliness and OCBs was exacerbated for individuals who worked from home. This is likely because OCBs tend to be contingent on coworkers observing peers in need of help. When the workplace is the home, peers and supervisors are not as easily observable as they would be in an office. Thus, employers should consider training programs to teach managers how to help work-from-home employees contribute OCB-type behaviors, in addition to training programs for work-from-home employees to assist them with contributing OCB-type behaviors to the same extent as they would if working from a corporate office.

Conclusion

Through the lens of SDT (9), the current study sought to: a) clarify the direct impact of workplace loneliness on work-relevant outcomes, and b) unpack the potential moderating impact of working from home on the aforementioned relations between workplace loneliness and outcomes. Results suggested that workplace loneliness negatively predicts affective organizational commitment, perceptions of coworker and supervisor support, organizational citizenship behaviors, and perceived performance. Furthermore, results implied that workplace loneliness and working from home have an interactive effect on affective organizational commitment, perceptions of coworker support, and organizational citizenship behaviors. While working from home had a beneficial impact on the relation between workplace loneliness and affective/relational outcomes, it had a detrimental impact on the relation between workplace loneliness and behavioral outcomes. Our findings highlight the importance of facilitating opportunities for employees to engage in OCBs from home.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

This study, which involved human participants, was reviewed and approved by Occidental College's IRB. Participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Working from home is also referred to as teleworking, remote working, and telecommuting. For the purposes of this paper, we will use these terms interchangeably.

References

1. Brenan M. COVID-19 and remote work: an update. Gallup. (2020). Available online at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/321800/covid-remote-work-update.aspx

2. Parker K, Horowitz JM, Minkin R. How the Coronavirus outbreak has – and hasn't – changed the way Americans work. Pew Research Center: Social and Demographic Trends. (2020). Available online at: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/12/09/how-the-coronavirus-outbreak-has-and-hasnt-changed-the-way-americans-work/

3. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Ability to work from home: Evidence from two surveys and implications for the labor market in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Monthly Labor Review. (2020). Available online at: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2020/article/ability-to-work-from-home.htm

4. Mann S, Holdsworth L. The psychological impact of teleworking: Stress, emotions and health. New Technol Work Employ. (2003) 18:196–211. doi: 10.1111/1468-005X.00121

5. Song Y, Gao J. Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. J Happiness Stud. (2020) 21:2649–68. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00196-6

6. Bloom N, Liang J, Roberts J, Ying ZJ. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q J Econ. (2015) 130:165–218. doi: 10.1093/qje/qju032

7. Killgore WD, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Lucas DA, Dailey NS. Loneliness during the first half-year of COVID-19 lockdowns. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 294:113551. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113551

8. Ozcelik H, Barsade SG. No employee an island: Workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad Manag Ann. (2018) 61:2343–66. doi: 10.5465/amj.2015.1066

9. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. (2000) 11:227–68. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

10. Patrick H, Knee CR, Canevello A, Lonsbary C. The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: a self-determination theory perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2007) 92:434–57. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434

11. Pavey L, Greitemeyer T, Sparks P. Highlighting relatedness promotes prosocial motives and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2011) 37:905–17. doi: 10.1177/0146167211405994

12. Reis HT, Sheldon KM, Gable SL, Roscoe J, Ryan RM. Daily well-being: the role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2000) 26:419–35. doi: 10.1177/0146167200266002

13. Tong EM, Bishop GD, Enkelmann HC, Diong SM, Why YP, Khader M, et al. Emotion and appraisal profiles of the needs for competence and relatedness. Basic Appl Soc Psych. (2009) 31:218–25. doi: 10.1080/01973530903058326

14. Malhotra R, Tareque MI, Saito Y, Ma S, Chiu CT, Chan A. Loneliness and health expectancy among older adults: a longitudinal population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69:3092–102. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17343

16. Lam LW, Lau, DC. Feeling lonely at work: Investigating the consequences of unsatisfactory workplace relationships. Int J Hum Resour. (2012) 23:4265–82. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.665070

17. De Jong Gierveld J, van Tilburg T, Dykstra P. Loneliness social isolation. In: Vangelisti A and Perlman D, Editor. The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2006). p. 485–500.

18. Weiss RS. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (1973).

19. Wright SL. Organizational climate, social support and loneliness in the workplace. Res Emot Organ. (2005) 1:123–42. doi: 10.1016/S1746-9791(05)01106-5

20. Erdil O, Ertosun OG. The relationship between social climate and loneliness in the workplace and effects on employee well-being. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. (2011) 24:505–25. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.091

21. Tabancali E. The relationship between teachers' job satisfaction and loneliness at the workplace. Eurasian J Educ Res. (2016) 16:1–30. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2016.66.15

22. Wright S, Silard A. Unravelling the antecedents of loneliness in the workplace. Hum Relat. (2021) 74:1060–81. doi: 10.1177/0018726720906013

23. Silman F, Dogan T. Social intelligence as a predictor of loneliness in the workplace. Span J Psychol. (2013) 16:E36. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2013.21

24. Kaymaz YDDK, Eroglu YDDU. Effect of loneliness at work on the employees' intention to leave. ISGUC the Journal of Industrial Relations and Human Resources. (2014) 16:38–53. doi: 10.4026/1303-2860.2014.0241.x

25. Senturan S, Çetin C, Demiralay T. An investigation of the relationship between role ambiguity, role conflict, workplace friendship, and loneliness at work. Int J Bus Soc. (2017) 8:60–8.

26. Mohapatra M, Madan P, Srivastava S. Loneliness at work: Its consequences and role of moderators. Glob Bus Rev. (2020) 1–18. doi: 10.1177/0972150919892714

27. Morris ZA. Loneliness as a Predictor of Work Disability Onset Among Nondisabled, Working Older Adults in 14 Countries. Journal of Aging and Health. (2020) 32(7–8), 554–563. doi: 10.1177/0898264319836549

28. Moens E, Baert S, Verhofstadt E, Van Ootegem L. Does loneliness lurk in temp work? Exploring the associations between temporary employment, loneliness at work and job satisfaction. PLoS ONE. (2019) 16:e0250664.

29. Wright SL. Is it lonely at the top? an empirical study of managers' and nonmanagers' loneliness in organizations. J Psychol. (2012) 146:47–60. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.585187

30. Powell L. Security of global oil flows: Risk assessment for India (part II). Observer Research Foundation: Energy News Monitor (2011, November 29). Available online at: https://www.orfonline.org/research/security-of-global-oil-flows-risk-assessment-for-india-part-ii/

32. Allen TD, Golden TD, Shockley KM. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol Sci. (2015) 16:40–68. doi: 10.1177/1529100615593273

33. Van Reenen CA, Nkosi M. Environmental benefits of telecommuting-A hypothetical case study. In: Sustainability Handbook 2020, Vol. 1. CSIR (2020). p. 97–105.

34. Global Workplace Analytics. Global Work-from-Home Experience Survey Report. (2020). Available online at: https://globalworkplaceanalytics.com/whitepapers

35. Steward B. Changing times: the meaning, measurement, and use of time in teleworking. Time Soc. (2000) 9:57–74. doi: 10.1177/0961463X00009001004

36. Zeidner R. Coronavirus makes work from home the new normal. SHRM. Available online at: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/all-things-work/pages/remote-work-has-become-the-new-normal.aspx (accessed March 23, 2020).

37. Conger K. Facebook Starts Planning for Permanent Remote Workers. The New York Times. (2020). Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/21/technology/facebook-remote-work-coronavirus.html (accessed May 21, 2020).

38. Abilash KM, Siju NM. Telecommuting: an empirical study on job performance, job satisfaction and employees commitment during pandemic circumstances. Shanlax Int J Manag. (2021) 8:1–10. doi: 10.34293/management.v8i3.3547

39. Kazekami S. Mechanisms to improve labor productivity by performing telework. Telecomm Policy. (2020) 44:101868. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2019.101868

40. Dutcher EG. The effects of telecommuting on productivity: an experimental examination. The role of dull and creative tasks. J Econ Behav Organ. (2012) 84:355–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2012.04.009

41. Ruth S, Chaudhry I. Telework: a productivity paradox? IEEE Internet Computing. (2008) 12:87–90. doi: 10.1109/MIC.2008.132

42. Baruch Y. Teleworking: benefits and pitfalls as perceived by professionals and managers. New Technol Work Employ. (2000) 15:34–49. doi: 10.1111/1468-005X.00063

43. Martin BH, MacDonnell R. Is telework effective for organizations? Manag Res Rev. (2012) 35:602–16. doi: 10.1108/01409171211238820

44. Delanoeije J, Verbruggen M. Between-person and within-person effects of telework: a quasi-field experiment. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. (2020) 29:795–808. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2020.1774557

45. ten Brummelhuis LL, Bakker AB, Hetland J, Keulemans L. Do new ways of working foster work engagement? Psicothema. (2012) 24:113–20.

46. McCloskey DW, Igbaria M. A review of empirical research on telecommuting and directions for future research. In: Igbaria M, Tan M, editors. The Virtual Workplace. Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing (1998). p. 338–58.

47. Crosbie T, Moore J. Work–life balance and working from home. Soc Policy Soc. (2004) 3:223–33. doi: 10.1017/S1474746404001733

48. Lyttelton T, Zang E, Musick K. Gender differences in telecommuting and implications for inequality at home and work. (2020). doi: 10.31235/osf.io/tdf8c

49. Huws U. Teleworking in Britain: A Report to the Employment Department. Employment Department (1993).

50. Sonnentag S, Mojza EJ, Binnewies C, Scholl A. Being engaged at work and detached at home: a week-level study on work engagement, psychological detachment, and affect. Work and Stress. (2008) 22:257–76. doi: 10.1080/02678370802379440

51. George JM. State or trait: effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. J Appl Psychol. (1991) 76:299–307. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.299

52. Staw BM, Barsade SG. Affect and managerial performance: a test of the sadder-but-wiser vs. happier-and-smarter hypotheses. Adm Sci Q. (1993) 38:304–31. doi: 10.2307/2393415

53. Pelled LH, Xin KR. Down and out: an investigation of the relationship between mood and employee withdrawal behavior. J Manage. (1999) 25:875–95. doi: 10.1177/014920639902500605

54. Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol. (1990) 63:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

55. Vandenberghe C, Bentein K, Stinglhamber F. Affective commitment to the organization, supervisor, and work group: antecedents and outcomes. J Vocat Behav. (2004) 64:47–71. doi: 10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00029-0

56. Vandenberghe C, Bentein K. A closer look at the relationship between affective commitment to supervisors and organizations and turnover. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2009) 82:331–48. doi: 10.1348/096317908X312641

57. Bolon DS. Organizational citizenship behavior among hospital employees: a multidimensional analysis involving job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Hosp Health Serv Adm. (1997) 42:221–41.

58. Trigueros R, Aguilar-Parra JM, López-Liria R, Rocamora P. The dark side of the self-determination theory and its influence on the emotional and cognitive processes of students in physical education. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4444. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224444

59. Tabancali E, Korumaz M. Relationship between supervisors' loneliness at work and their organizational commitment. Int Online J Educ Sci. (2015) 7:172–89. doi: 10.15345/iojes.2015.01.015

60. Sias PM. Exclusive or exclusory: Workplace relationships and ostracism, cliques, and outcasts. In: Omdahl BL, Harden Fritz JM, editors. Problematic Relationships in the Workplace, Vol. 2. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing (2012). p. 105–24.

61. Graen GB Liden RC, Hoel W. Role of leadership in the employee withdrawal process. J Appl Psychol. (1982) 67:868–72. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.67.6.868

62. Sias PM. Workplace relationship quality and employee information experiences. Communication Studies. (2005) 56:375–95. doi: 10.1080/10510970500319450

63. O'Driscoll MP, Beehr TA. Moderating effects of perceived control and need for clarity on the relationship between role stressors and employee affective reactions. J Soc Psychol. (2000) 140:151–9. doi: 10.1080/00224540009600454

64. O'Driscoll MP, Brough P, Kalliath TJ. Work/family conflict, psychological well-being, satisfaction and social support: A longitudinal study in New Zealand. Equal Oppor Int. (2004) 23:36–56. doi: 10.1108/02610150410787846

65. Kottke JL, Sharafinski CE. Measuring perceived supervisory and organizational support. Educ Psychol Meas. (1988) 48:1075–9. doi: 10.1177/0013164488484024

66. Ducharme LJ, Knudsen HK, Roman PM. Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: the protective role of coworker support. Sociological Spectrum. (2007) 28:81–104. doi: 10.1080/02732170701675268

67. Tews MJ, Michel JW, Ellingson JE. The impact of coworker support on employee turnover in the hospitality industry. Group Organ Manag. (2013) 38:630–53. doi: 10.1177/1059601113503039

68. Zaitouni M, Ouakouak ML. Key predictors of individual creativity in a Middle Eastern culture: the case of service organizations. Int J Organ Anal. (2018) 26:19–42. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-03-2017-1139

69. Sloan MM. Unfair treatment in the workplace and worker well-being: the role of coworker support in a service work environment. Work Occup. (2012) 39:3–34. doi: 10.1177/0730888411406555

70. Škerlavaj M, Cerne M, Dysvik A, I. get by with a little help from my supervisor: creative-idea generation, idea implementation, and perceived supervisor support. Leadersh Q. (2014) 25:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.05.003

71. Gagnon M, Michael JH. Outcomes of perceived supervisor support for wood production employees. For Prod J. (2004) 54:172–7.

72. Maertz CP, Griffeth RW, Campbell NS, Allen DG. The effects of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on employee turnover. J Organ Behav. (2007) 28:1059–75. doi: 10.1002/job.472

73. Stoica M, Brate TA, Bucu?ă M, Dura H, Morar S. The association of loneliness at the workplace with organisational variables. Eur J Sci Theol. (2014) 10:101–12.

74. Öge E, Çetin M, Top S. The effects of paternalistic leadership on workplace loneliness, work family conflict and work engagement among air traffic controllers in Turkey. J Air Transp. (2018) 66:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.10.003

75. Borman WC, Motowidlo SJ. Task performance and contextual performance: the meaning for personnel selection research. Hum Perform. (1997) 10:99–109. doi: 10.1207/s15327043hup1002_3

76. Vischer JC. The effects of the physical environment on job performance: towards a theoretical model of workspace stress. Stress and Health. (2007) 23:175–84. doi: 10.1002/smi.1134

77. Smith CA, Organ DW, Near JP. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J Appl Psychol. (1983) 68:653–63. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.68.4.653

78. Podsakoff PM, Ahearne M, MacKenzie SB. Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. J Appl Psychol. (1997) 82:262–70. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.262

79. Deniz S. Effect of loneliness in the workplace on employees' job performance: a study for hospital employees. J Health Serv Res Policy. (2019) 4:214–24. doi: 10.23884/ijhsrp.2019.4.3.06

80. Uslu O. Being alone is more painful than getting hurt: The moderating role of workplace loneliness in the association between workplace ostracism and job performance. Cent Eur Bus. (2020) 10:19–38. doi: 10.18267/j.cebr.257

81. Santas G, Isik O, Demir A. The effect of loneliness at work; work stress on work alienation and work alienation on employees' performance in Turkish health care institutions. South Asian J Manage Sci. (2016) 10:30–8. doi: 10.21621/sajms.2016102.03

82. Kelliher C, Anderson D. For better or for worse? an analysis of how flexible working practices influence employees' perceptions of job quality. Int J Hum Resour. (2008) 19:419–31. doi: 10.1080/09585190801895502

83. De Spiegelaere S, Van Gyes G, Van Hootegem G. Not all autonomy is the same Different dimensions of job autonomy and their relation to work engagement and innovative work behavior. Hum Factors Ergon Manuf. (2016) 26:515–27. doi: 10.1002/hfm.20666

84. Froiland JM. Parents' weekly descriptions of autonomy supportive communication: promoting children's motivation to learn and positive emotions. J Child Fam Stud. (2015) 24:117–26. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9819-x

85. Budge C, Carryer J, Wood S. Health correlates of autonomy, control and professional relationships in the nursing work environment. J Adv Nurs. (2003) 42:260–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02615.x

86. Gagn, é M. The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motiv Emot. (2003) 27:199–223. doi: 10.1023/A:1025007614869

87. Qualtrics [computer software] (2020). Available online at: https://www.qualtrics.com/.

88. Wright SL, Burt CD, Strongman KT. Loneliness in the workplace: construct definition and scale development. NZ J Psychol. (2006) 35:59–68.

89. Bal PM, De Lange AH. From flexibility human resource management to employee engagement and perceived job performance across the lifespan: a multisample study. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2015) 88:126–54. doi: 10.1111/joop.12082

Keywords: workplace loneliness, working from home (WFH), affective organizational commitment, coworker support, supervisor support, OCBs, perceived performance

Citation: Wax A, Deutsch C, Lindner C, Lindner SJ and Hopmeyer A (2022) Workplace Loneliness: The Benefits and Detriments of Working From Home. Front. Public Health 10:903975. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.903975

Received: 24 March 2022; Accepted: 29 April 2022;

Published: 27 May 2022.

Edited by:

Francesco Chirico, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Minseong Kim, Louisiana State University in Shreveport, United StatesPerengki Susanto, Padang State University, Indonesia

Pietro Crescenzo, Volunteer Military Corps, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Wax, Deutsch, Lindner, Lindner and Hopmeyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amy Wax, YW15LndheEBjc3VsYi5lZHU=

Amy Wax

Amy Wax Caleb Deutsch2

Caleb Deutsch2 Steven J. Lindner

Steven J. Lindner