- 1Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States

- 2Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States

- 3Facultad de Medicina y Psicología, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico

Tattoos are less prevalent in Mexico and tattooed persons are frequently stigmatized. We examine the prevalence and correlates of interest in receiving tattoo removal services among 278 tattooed Mexican adults living in Tijuana, Mexico who responded to interviewer-administered surveys, including open-ended questions. Overall, 69% of participants were interested in receiving free tattoo removal services, 31% reported facing employment barriers due to their tattoos, and 43% of respondents regretted or disliked some of their tattoos. Having a voter identification card, reporting moderate/severe depression symptoms and believing that tattoo removal would remove employment barriers were independently associated with interest in tattoo removal. Our findings suggest that there is substantial interest in tattoo removal services. Publicly financed tattoo removal services may help disadvantaged persons gain access to Mexico's labor market and it may positively impact other life domains such as mental well-being and interactions with law enforcement.

Introduction

Tattooing is practiced around the world and is considered a form of art and body modification (1). Tattoos have been used as a form of self-expression, during rites of passage, to convey information about relational ties among community subgroups and about the tattooed individual; tattoos have also been used as a form of punishment (1). Over the past several decades, tattoos have gained in popularity in the United States (U.S.) and elsewhere (2). In Mexico, an estimated 12 million individuals are tattooed (3). However, tattoos may be associated with anti-social behaviors and tattooed individuals may experience negative reactions from the community (4–10). Tattoo-related stigma may create additional barriers for resettlement, among the thousands of migrants deported from the U.S. (i.e., deportees), many of whom settle in the Mexican border city of Tijuana which lies adjacent to California, U.S. (11, 12). For example, tattooed adults living in Tijuana have reported discrimination in employment, housing, as well as negative interactions with local law enforcement due to their tattoos (13–16). This study examines interest in receiving tattoo removal among structurally vulnerable adults in Tijuana, as this service may help reduce stigma experienced by tattooed community members.

Deportees residing in Tijuana face a unique risk environment that can challenge their emotional, physical and social well-being (13, 15–19). In addition, politicians and law-enforcement agencies in the U.S. have portrayed undocumented immigrants as a threat to public safety (20–23) influencing Mexicans' perceptions of deportees (9, 15, 24, 25). In Mexico, deportees often face discrimination from community members and the police, who may view them as criminals (13–16, 19). Stigma associated with tattoos may exacerbate the social precarity and vulnerability experienced by deportees in Mexican communities (4, 7–9, 15, 16).

Stigma is recognized to be a socially constructed concept that is characterized by multiple dimensions. Goffman's pioneering work initially documented the ways in which community members' treatment and perception of individuals may vary when individuals' characteristics deviate from what is deemed to be expected and the norm (26). Stigma is thus conceptualized as being created when an individual has a visible or non-visible undesirable trait that modifies an individual's relationship with other community members. Stereotyping may occur because of perceived or actual differences and the affected person's status in society may be adversely impacted (26). Additional work by Link and Phelan advance our understanding of stigma by highlighting the influence of institutions and other power structures, such as policies, in supporting the stigmatization and exclusion of individuals or groups of individuals who are deemed to not conform to the broader society's norms (26, 27). Stigma has been found to extend to the affected individual resulting in self-stigma and to that person's close contacts through stigma by association (28, 29). A growing body of work has recognized that interpersonal and structural discrimination can adversely influence health outcomes and well-being including self-esteem and self-efficacy (27, 30).

Tattoos may be stigmatized when they are visible or contain markers of stigmatized affiliations or images that are viewed as being anti-social (e.g., gang symbols) (1, 31–33). Individuals with tattoos placed near their face or hands may be judged to be of poor character (6, 34, 35), discriminated against by employers (6, 36), or harassed by police (16). Tattoo-related stigma may create feelings of regret, lead some to hide their tattoos in order to avoid discrimination or generate an interest in tattoo removal (15, 16, 37–41). While laser tattoo removal is effective (42), it is also a financially burdensome and time consuming procedure (43). The prohibitive costs of professional tattoo removal services may lead some individuals to resort to amateur methods to remove their tattoos (1, 44), which are often ineffective and can have harmful side effects including pain and scarring (38, 45, 46).

In the United States, a limited number of free or subsidized tattoo removal programs for structurally vulnerable populations (e.g., former gang members, probationers) are available (14, 44, 47). Laser tattoo removal may aid in reducing social stigma, improve social relationships, improve labor market participation, and improve the well-being of structurally vulnerable populations (44, 48, 49). However, less is known about the experiences or characteristics of tattooed Mexicans, including migrants and deportees, the prevalence of tattoo regret, interest in receiving tattoo removal, and reasons for seeking this service. These topics are the focus of this investigation which was conducted with a large sample of economically disadvantaged tattooed Mexican adults in Tijuana, Mexico; a large proportion of whom are migrants. We hypothesized that tattooed deported migrants and unemployed persons would be most interested in undergoing laser tattoo removal. Analyses were stratified by participants' interest in receiving tattoo removal in order to shed light on the characteristics of those who believe they may benefit from this service. Findings can inform the implementation of programs to support tattooed persons' integration into society and may have relevance for other communities where tattooed persons are stigmatized (50–52).

Methods

Participants and data collection

This mixed-methods cross-sectional study is based on data collected between January-May 2013. A convenience sample of 584 Mexican adults ages 18+ participated in the study; persons who were younger than age 18 based on self-report or who could not provide informed consent were excluded from joining the study. This analysis is limited to 278 tattooed Mexican adults (47% of the full sample, data not shown) attending a free healthcare clinic in Tijuana's Zona Norte [red light district] <1 mile of the U.S.-Mexico border.

In brief, participants responded to an interviewer-administered questionnaire (15, 16) designed to understand the health and social needs of disadvantaged persons in the region, including migrants (i.e., deported, internal, and cross-national migrants). Eligibility criteria for this analysis were: (1) Mexico-born age ≥18 years old; (2) seeking any service at the study site; (3) speaking Spanish or English, and 4) having ≥1 tattoo. All participants who met these criteria were invited to participate; those interested in joining the study provided their signed informed consent and received refreshments and $10 compensation for their time. This study was approved by the University of California, San Diego Human Research Protection Program and the Ethics Boards of the Health Frontiers in Tijuana Clinic and the Autonomous University of Baja California Medical School.

Measures

Quantitative data

The survey was developed by the researchers, with the exception of the depression scale, for application to this unique setting; it has been used to support prior research (15, 16). Trained bilingual interviewers administered the survey. Data collection lasted ~45 min and interviewers entered participants' responses in tablet computers utilizing Qualtrics survey software (Provo, UT, US). Socio-demographic factors included age, gender, and U.S. migrant status (never migrated; deported migrant; non-deported migrant). Risk Environment measures consider the following conditions: recent drug use or injection drug use (i.e., past 6 months; both yes/no), recent trading sex (past 6 months), ever incarcerated in the USA or Mexico or both countries (yes/no). Social exclusion variables included: possession of a Mexican federal voter identification card (yes/no), covered by Seguro Popular (yes/no) a federal public health insurance program which covers impoverished persons (53), and depression symptoms (none to mild vs. moderate to severe) per the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) depression short form (PROMIS-D-8; 8b short form) (54, 55). Recent homeless status was defined by where participants slept most frequently in the prior 6 months: those who slept in migrant shelters, churches, streets, public parks, vacant lots, or the Tijuana River canal were classified as homeless. Participants responded to diverse adverse encounters: “During the last 6 months… a) have you ever been threatened or harassed by police, federal agents or army members in Tijuana? b) denied a job in Tijuana, c) denied access to housing or a shelter or other place that you can sleep or live in Tijuana? Respondents also identified potential access to social support, responding to the question: “Do you have friends or family in Tijuana”? (yes/no). These data are shown in Table 1.

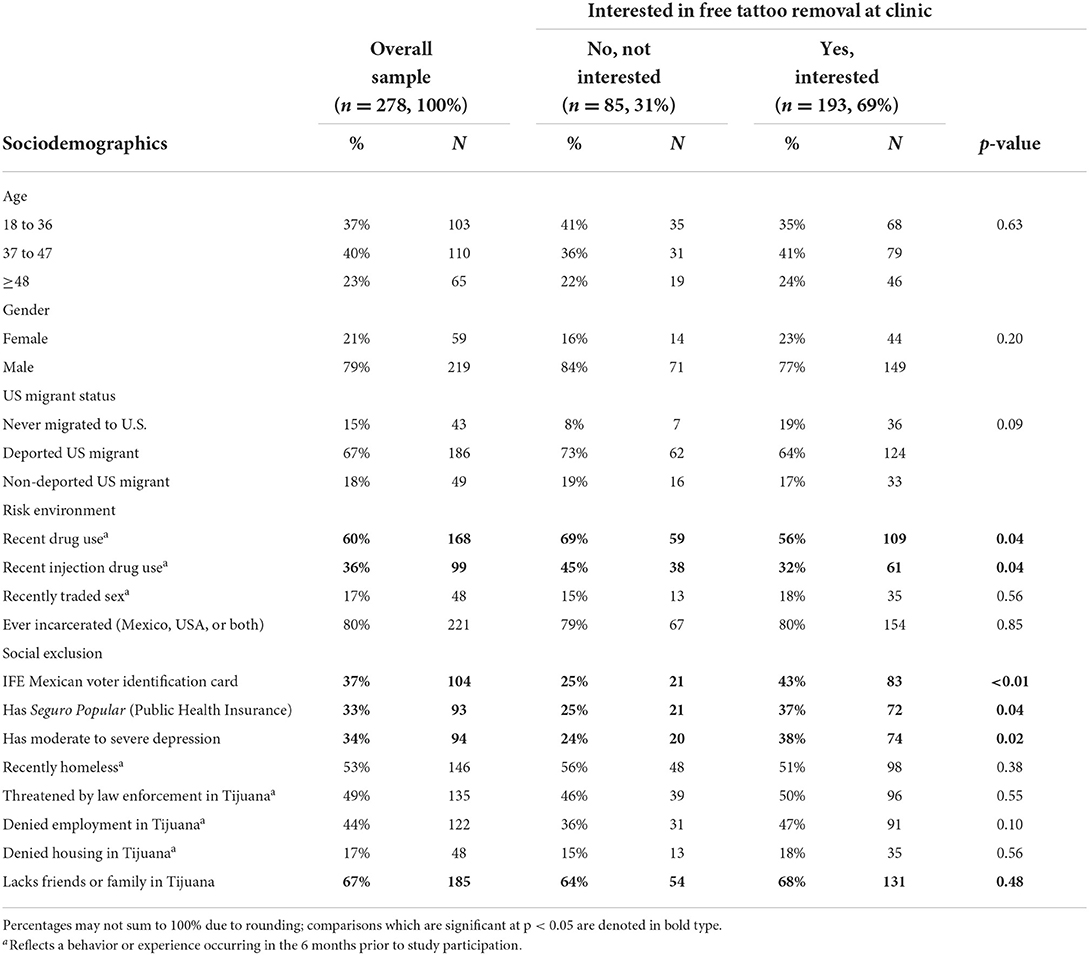

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of Mexican tattooed adults (n = 278) receiving free medical care, stratified by interest in receiving free laser tattoo removal at the study site, Tijuana, Mexico, 2013.

We characterize participants' tattoos (Table 2), including the total number of tattoos (1; 2–3; ≥4), tattoo visibility (forearms, hands, face, neck; versus not on these locations), tattoo imagery/content (text/names; animals/nature-images; religious images; death/skulls; weapons/gang symbols). Participants reported their feelings about the tattoos (i.e., does not like some or all tattoos vs. likes all tattoos or is indifferent about them), whether they believe that they have experienced barriers to employment because of their tattoos (yes/no), and beliefs that removing tattoos would reduce barriers to employment (yes/no).

Table 2. Tattoo characteristics and participants' perceptions, reported by Mexican tattooed adults (n = 278) receiving free medical care, stratified by interest in receiving free laser tattoo removal at the study site, Tijuana, Mexico, 2013.

For the dependent variable, participants were asked: “Imagine that in the next 6 months there was a free service here [at the clinic] to remove tattoos, do you think you would be interested in using those services?” (yes/no).

Qualitative data derived from the survey

The questionnaire included several open-ended questions. Participants interested in removing some or all of their tattoos were asked: “Currently, what are all the reasons for which you DO want to remove your tattoos?” Interviewers entered participants' responses (n = 156) for those who responded in the affirmative into the survey software verbatim.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated using STATA v16 to characterize participants' sociodemographic, tattoo-related, and vulnerability characteristics; analyses were stratified by interest in receiving free tattoo removal at the clinic where the study was conducted (Tables 1, 2). For categorical variables, we employed Pearson chi-square tests to assess statistical significance between groups. Variables attaining significance levels of p < 0.10 in binary analyses were considered for inclusion in multivariable logistic regression models that assessed the relationship between each independent variable and interest in receiving free tattoo removal services at the clinic. We controlled for migrant status given the pervasiveness of tattoos among U.S. migrants (Table 4).

Qualitative text data were entered into a spreadsheet and two authors utilized the methodology of “Coding Consensus, Co-occurrence, and Comparison,” based on grounded theory techniques (56, 57) to code responses and identify emergent themes; conflicts in coding were discussed and resolved (56). Some responses were assigned multiple codes. The main themes are described and illustrative quotes are provided in English and Spanish (Table 3). The authors translated all quotes into English. We provide percentages for each theme to illustrate its significance within the text responses (58). Participants who indicated that they did not want to remove their tattoos were asked why they did NOT want to remove their tattoos and themes emerging from participants' responses (n = 89) are summarized in the text (data not shown in table). The responses to both questions represent 245 responses (i.e., 88% of tattooed participants); participants were not required to respond to these questions, though most did.

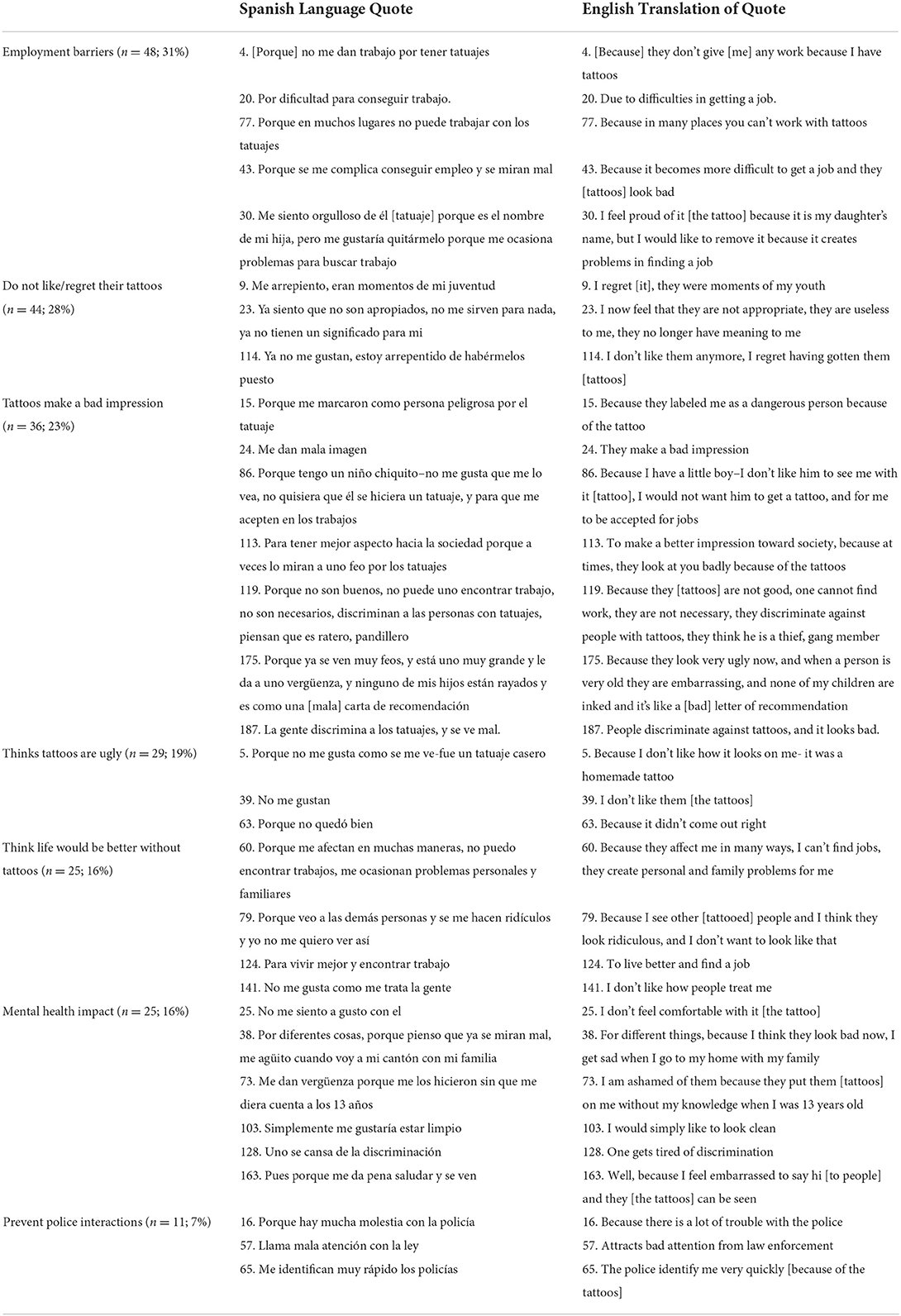

Table 3. Reasons for interest in receiving tattoo removal expressed by Mexican tattooed adults (n = 156) receiving free medical care, Tijuana, Mexico, 2013.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 presents sociodemographic characteristics and exposure to the risk environment among a sample of tattooed Mexicans (n = 278), stratified by interest in receiving free tattoo removal at the study site. Overall, 69% of participants were interested in receiving free tattoo removal services. Participants were largely non-elderly between the ages of 18–47 years (77%) and 79% were male. Most participants had a history of migration to the U.S., and 67% of participants reported a history of deportation from the U.S. With respect to the risk environment, 60% of participants reported recent drug use, 36% recently injected drugs and 17% recently traded sex. The majority of participants (80%) reported ever being incarcerated in the U.S., Mexico, or both countries. Measures of social exclusion are also reported in Table 1. Approximately one-third of participants (37%) reported having an IFE voter card at the time of interview and 33% were enrolled in Seguro Popular which is Mexico's universal health insurance program. Symptoms of moderate to severe depression were reported by 34% of participants. More than one-half of participants (53%) were recently homeless, 17% were recently denied housing, and 49% reported recently being threatened by local law enforcement. Connections to the labor market were also assessed and 44% reported being recently denied employment, while local social support was low: 67% lacked friends or family in Tijuana.

Interest in tattoo removal stratified by participant characteristics

We examined interest in tattoo removal by participants' characteristics. There were no statistically significant differences in interest in tattoo removal by age, gender, or U.S. migrant status (Table 1). Similarly, of the risk environment characteristics examined, there were no differences in interest in tattoo removal among those who recently traded sex or were recently incarcerated. Of Social Exclusion variables, interest in tattoo removal did not vary by report of recent homelessness or threats by law enforcement, being denied access to employment, or lacking friends or family in Tijuana. However, participants interested in tattoo removal were less likely than those who were uninterested in tattoo removal to report recent drug use (56 vs. 69%, respectively, p = 0.04) and recent injection drug use (32 vs. 45%, respectively, p = 0.04). Those interested in tattoo removal services were more likely to have a voter identification card (43 vs. 25%, respectively, p < 0.01) and be enrolled in Seguro Popular (37 vs. 25%, respectively, p = 0.04) than those uninterested in receiving tattoo removal. Those interested in tattoo removal were more likely to display symptoms of moderate/severe depression (38 vs. 24% among those uninterested in tattoo removal, p = 0.02).

Characteristics of participants' tattoos and stratification by interest in tattoo removal

Participants were asked about the characteristics of their tattoos (Table 2). A minority of participants had only 1 tattoo (27%), 30% reported 2–3 tattoos, and 44% had 4+ tattoos. One-third of participants (37%) had visible tattoos. Tattoo imagery and content varied. Seventy percentage included names or text; animal or nature images (32%), religious (17%), death/skulls (12%), and gang/weapon (8%) tattoos were less commonly reported. Overall, 43% of participants reported disliking some or all of their tattoos; 31% reported experiencing barriers to employment because of their tattoos, and 56% believed that removing their tattoos would help them find employment in Tijuana.

Participants' perceptions of their tattoos and their impact on their lives rather than the characteristics of the tattoos played an important role in participants' interest in removing their tattoos. Specifically, there number or visibility of tattoos or the imagery was not statistically associated with interest in removing the tattoos. Rather, those who reported an interest in tattoo removal were significantly more likely to dislike some or all of their tattoos (60 vs. 6% among those uninterested in tattoo removal, p < 0.01), to report barriers to securing employment due to their tattoos (35 vs. 20% of those uninterested in removal; p = 0.01), and to believe that tattoo removal would help them find employment (62 vs. 41% among those uninterested in removal, p < 0.01).

Qualitative results: Motivations for seeking tattoo removal

Reasons for desiring tattoo removal varied across participants; themes and illustrative quotes are presented in Table 3. Participants most frequently reported experiencing Employment Barriers (31%): they described a local labor market which wholly rejected tattooed persons. A significant number of participants disliked their tattoos and regretted them (28%). Some participants obtained tattoos as youths or no longer identified with the tattoos or what they represented. Numerous participants felt that tattoos make a bad impression (23%) and contributed to labeling and stereotyping by others. Some participants felt that their tattoos are ugly (19%) and for some participants, this emotion was related to changes in the quality of the image over time. Some participants also believed that their lives would be better without tattoos (16%) and that they negatively impacted participants' mental health (16%), contributing to feelings of discomfort or shame. Other participants identified the toll of discrimination and negative interactions and anxiety/stress resulting from family interactions as motivators for interest in tattoo removal. Negative interactions with law enforcement (7%) were infrequently reported but acknowledged by some participants.

Participants who were uninterested in receiving tattoo removal were asked to explain their reasons and responses fell into three general categories: participants liked their tattoos, or felt that their tattoos are meaningful, or were not interested because they did not have confidence in the results of tattoo removal (Data not shown).

Factors independently associated with interest in receiving free laser tattoo removal

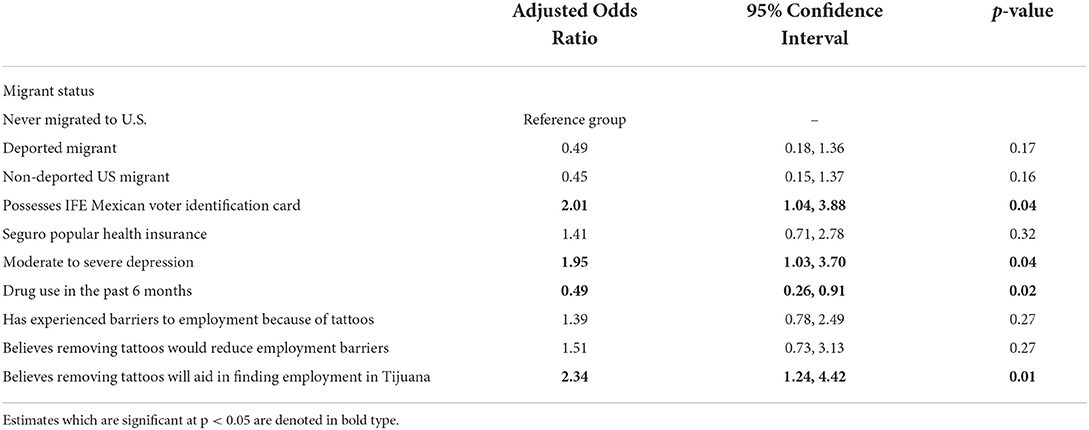

Table 4 presents results from logistic regression analyses identifying factors independently associated with interest in free tattoo removal services at the study site. No demographic factors were associated with interest in receiving tattoo removal. Of Social Exclusion variables, possession of an IFE Mexican voter identification card was independently associated with being interested in receiving free tattoo removal services at the clinic [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR): 2.01; 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.04, 3.88; p = 0.04], as was reporting moderate to severe depression (AOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.03, 3.70; p = 0.04). Of Participants' Perceptions regarding the impact of tattoos, believing that tattoo removal would remove barriers to employment (AOR: 2.34; 95% CI: 1.24, 4.42; p = 0.01) was also associated with a greater interest in tattoo removal. From Risk Environment variables, drug use in the past 6 months was negatively associated with interest in tattoo removal (AOR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.91; p = 0.02).

Table 4. Factors independently associated with interest in receiving free laser tattoo removal at the clinic among Mexican adult tattooed free clinic patients (n = 278), Tijuana, Mexico, 2013.

Discussion

Tattooing is a pervasive practice worldwide, however, to our knowledge, this study contributes previously unavailable data regarding the perceptions and experiences of a diverse sample of tattooed adults in Mexico. The popular press and several studies have identified tattoo-related stigma and discrimination, including among migrants returning to Mexico (16, 59, 60). Our mixed-methods study corroborates anecdotal evidence with quantitative and qualitative data from a large sample; key findings are contextualized below. This study has important public health implications: laser tattoo removal is desired and can assist tattooed adults engage more broadly with Mexican society and potentially overcome tattoo-related stigma and discrimination (17). Findings may have relevance for other migrant-receiving communities.

For many decades, Mexico has been a major migrant sending country to the U.S. due to diverse social and economic ties that have supported migrant flows between both countries (61, 62). Return migration is not uncommon and our research demonstrates that tattoos are pervasive among persons with histories of U.S. migration. Notably, recent changes to immigration enforcement policies have resulted in the forcible expulsion or voluntary return of Mexican nationals: for example, annually between 2013 and 2020, the United States deported between ~151,000 to ~307,000 migrants to Mexico (12). Consequently, innovative strategies are needed to reintegrate migrants into Mexican society. Moreover, by reducing social exclusion, stigma and discrimination, migrants returning to Mexico may be able to leverage skills and human capital developed in the U.S. for their benefit as well as that of receiving communities in Mexico (63).

In multivariate analyses, participants who believed that removing their tattoos would assist them in finding employment and those possessing a voter identification card were more likely to be interested in tattoo removal. We interpreted these findings to mean that those with a governmental identification card were more likely to be able to navigate the legal aspects associated with interacting with public and private institutions, including the labor market as a governmental identification is required to join workplaces in the formal economy. The qualitative data collected by this study indicated that tattoos often generated stigma and discrimination which contributed to the exclusion of study participants from the labor market. Thus, removal of unwanted tattoos was believed to support access to employment opportunities.

Individuals lacking a Mexican voter identification card are, in effect, undocumented. Studies examining the experiences of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. have demonstrated that lacking a legal status and identification is associated with social stigma, increased stress, anxiety and situations that create vulnerability (64). An undocumented status is also associated with social, economic and health disadvantages due to reduced access to legal, safe and well-paying employment opportunities (65) or public benefits programs (e.g., health insurance coverage) (64). In Mexico, only adults who also possess a birth or naturalization certificate can access the voter card (formerly IFE, now INE card), which serves as the nation's primary form of national identification (66). While Mexico is currently classified as a Upper Middle Income Country (67) it continues to experience economic and geographic disparities; rural communities especially may encounter challenges in providing timely access to birth certificates to their residents, resulting in an “undocumented” status among some individuals (68). Other nations have implemented diverse strategies to overcome challenges to birth certificate access, including birth registration campaigns, providing birth certificates free of charge, and expediting access to this document (68, 69). These strategies may be implemented more broadly to ensure that individuals' identity can be substantiated across the lifespan. Migrants can benefit from Mexico's “Programa de Repatriación” (Repatriation Program) and “Programa Somos Mexicanos” (We are Mexicans Program) which can help migrants re-establish their identity (via access to birth certificates, temporary identification cards and other documents) and obtain critical services early within the repatriation process (e.g., nutrition, health, housing, employment services, and others) (63, 70). To overcome barriers to legal identity among voluntary and forcibly returned migrants, access to the aforementioned programs should be expanded beyond the repatriation period or to other individuals in need of these services.

We observed that participants reporting mental health challenges (i.e., depression symptoms) were more likely to report an interest in tattoo removal while recent substance users were less likely to be interested in tattoo removal. Tattoos may include images that make the individual uncomfortable or embarrassed, hinder their participation in social or economic pro-social activities, or the images may contribute to personal harm due to interpersonal violence (e.g., gang-related motifs) (71). These findings are concordant with extant studies that report that tattoos can provoke adverse mental health impacts when personal identities evolve (e.g., older age) or social affiliations change (e.g., withdrawing from gangs) (14, 39, 72). Entities implementing tattoo removal programs should consider the mental health consequences of having unwanted tattoos when defining the eligibility criteria in order to provide the maximum benefit to persons seeking this service. For example, programs may consider removing all tattoos regardless of their source (e.g., prison; gang affiliation) or location on the body; there is precedent for such an approach in the U.S. and preliminary data indicate that this approach has yielded favorable results for participants (73).

Limitations

Findings must be considered in light of the following factors. The study may not reflect the experiences of all migrant receiving communities or migrants from other regions. However, the study recruited a large convenience sample of migrants, including tattooed migrants, which are important strengths of this investigation as the research sheds light not only on the experience of tattoos among migrants but how they perceive these marks impact their integration into receiving communities such as Tijuana, Mexico. This study was conducted in 2013 and should be replicated to explore changes in policies, social views regarding tattoos, and changing migration flows from Central America, Eastern Europe and other countries to the US-Mexico border region. Undertaking a similar study in multiple deportee receiving countries would be helpful to understand the challenges faced by deportees seeking to resettle outside of the United States. While our study included a small sample of women, the experiences of tattooed women are generally under-represented in the literature, thus, this study suggests that additional research is needed to understand the challenges that tattooed women may face in Latin America. The data were based on self-report and may be subject to social desirability bias or recall bias. Nevertheless, our study makes significant contributions to the study of social exclusion in the context of Latin America, including the challenges faced by migrants in the region.

Conclusions

This study explored the issues of tattoo regret, motivations for seeking removal of unwanted tattoos and interest in receiving laser tattoo removal in the U.S.-Mexico border city of Tijuana. Our findings suggest that there is a substantial interest in receiving tattoo removal services, which are quite costly and may be a significant barrier to this service for low income and underserved persons in Mexico (74). A package of services (i.e., governmental identification, tattoo removal) which are publicly financed may assist disadvantaged persons, especially migrants, gain increased access to the labor market, which will aid other life domains (e.g., mental well-being, interactions with law enforcement, income, housing, food insecurity, interpersonal relationships with community members). Similar research should be undertaken elsewhere in order to shed light on the impact of tattoo related stigma across diverse communities and for population subgroups (e.g., forcibly returned migrants, voluntarily returned migrants, asylum seekers, refugees). Findings may shed light on the types of interventions that are needed to overcome tattoo regret and tattoo-related stigma in diverse social context. Longitudinal research is needed to understand whether the social, economic and mental health status of tattooed individuals improves as a result of eliminating unwanted tattoos.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of California, San Diego, Human Research Protection Program; the Ethics Boards of the Health Frontiers in Tijuana Clinic and the Autonomous University of Baja California Medical School. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

VO, JB, and AV-O conceptualized the study and wrote the manuscript. CM and OS assisted with the analyses and preparation of manuscript. All authors prepared and reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the UC GloCal Fellowship and the AIDS International Training Research Program funded by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R25TW009343 and D43TW008633; the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse under Grant #K01DA025504 and #R37DA019829-S1; the National Institute on Mental Health under Grant #K01MH095680, and the University of California Global Health Institute. The views presented here do not represent the funders.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants and for sharing their time with us; without them, this study would not have been possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Demello M. The convict body: tattooing among male American prisoners. Anthropol Today. (1993) 9:10–3. doi: 10.2307/2783218

2. Kluger N. Epidemiology of tattoos in industrialized countries. Tattooed Skin and Health. (2015) 48:6–20. doi: 10.1159/000369175

3. Cruz O. Si Buscas Trabajo Y Tienes Tatuajes, Esto Te Interesa. Ciudad de México: UnoTVCom (2019).

4. Broussard KA, Harton HC. Tattoo or taboo? Tattoo stigma and negative attitudes toward tattooed individuals. J Soc Psychol. (2018) 158:521–40. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2017.1373622

5. The Harris Poll (2016). Available online at: https://theharrispoll.com/tattoos-can-take-any-number-of-forms-from-animals-to-quotes-to-cryptic-symbols-and-appear-in-all-sorts-of-spots-on-our-bodies-some-visible-in-everyday-life-others-not-so-much-but-one-thi/

6. Larsen G, Patterson M, Markham L. A deviant art: tattoo-related stigma in an era of commodification. Psychol Mark. (2014) 31:670–81. doi: 10.1002/mar.20727

7. Zestcott CA, Tompkins TL, Kozak Williams M, Livesay K, Chan KL. What do you think about ink? An examination of implicit and explicit attitudes toward tattooed individuals. J Soc Psychol. (2018) 158:7–22. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2017.1297286

8. Zestcott CA, Bean MG, Stone J. Evidence of negative implicit attitudes toward individuals with a tattoo near the face. Group Process Intergroup Relat. (2017) 20:186–201. doi: 10.1177/1368430215603459

9. Anderson J. “Tagged as a criminal”: narratives of deportation and return migration in a Mexico City call center. Lat Stud. (2015) 13:8–27. doi: 10.1057/lst.2014.72

10. Herrera E, Jones GA. Benítez STd. Bodies on the line: identity markers among Mexican street youth Children's Geographies. (2009) 7:67–81. doi: 10.1080/14733280802630932

11. Amuedo-Dorantes C, Puttitanun T, Martinez-Donate AP. Deporting “Bad Hombres”? the profile of deportees under widespread versus prioritized enforcement. Int Migr Rev. (2019) 53:518–47. doi: 10.1177/0197918318764901

12. United States Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2020. Washington, DC (2020).

13. Horyniak D, Pinedo M, Burgos JL, Ojeda VD. Relationships between integration and drug use among deported migrants in Tijuana, Mexico. J Immigrant Minority Health. (2017) 19:1196–206. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0518-8

14. Bazan LE, Harris L, Lorentzen LA. Migrant gangs, religion and tattoo removal. Peace Review. (2002) 14:379–83. doi: 10.1080/1040265022000039150

15. Kremer P, Pinedo M, Ferraiolo N, Vargas-Ojeda AC, Burgos JL, Ojeda VD. Tattoo removal as a resettlement service to reduce incarceration among mexican migrants. J Immigrant Minority Health. (2019) 22:110–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00870-0

16. Pinedo M, Burgos JL, Ojeda AV, FitzGerald D, Ojeda VD. The role of visual markers in police victimization among structurally vulnerable persons in Tijuana, Mexico. Int J Drug Policy. (2015) 26:501–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.08.019

17. Dibble S. Deportees Learn Workforce and Life Skills at Tijuana Migrant Shelter. San Diego Union-Tribune (2018).

18. Infante C, Idrovo AJ, Sánchez-Domínguez MS, Vinhas S, González-Vázquez T. Violence committed against migrants in transit: experiences on the Northern Mexican Border. J Immigrant Minority Health. (2012) 14:449–59. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9489-y

19. Pinedo M, Burgos JL, Ojeda VD. A critical review of social and structural conditions that influence HIV risk among Mexican deportees. Microbes Infect. (2014) 16:379–90. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.02.006

20. Chavez LR. Mexicans of Mass Destruction:: National Security and Mexican Immigration in a Pre- and Post-9/11 World. In: MartÍNez S, editor. International Migration and Human Rights. The Global Repercussions of U.S. Policy. 1 ed. University of California Press (2009). p. 82–97.

21. Miller TA. Blurring the boundaries between immigration and crime control after september 11th immigration law and human rights: legal line drawing post-september 11-symposium article. BC Third World LJ. (2005) 25:81–124.

22. Macías-Rojas P. Immigration and the war on crime: law and order politics and the illegal immigration reform and immigrant responsibility act of 1996. Journal on Migration and Human Security. (2018) 6:25. doi: 10.1177/233150241800600101

23. Baker B, Marchevsky A. Gendering deportation, policy violence, and Latino/a family precarity. Lat Stud. (2019) 17:207–24. doi: 10.1057/s41276-019-00176-0

24. Wheatley C. Push Back: U.S Deportation Policy and the Reincorporation of Involuntary Return Migrants in Mexico*. The Latin Americanist. (2011) 55:35–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1557-203X.2011.01135.x

25. Sarabia H. “Felons, not Families”: Criminalized illegality, stigma, and membership of deported “criminal aliens”. Migration Letters. (2018) 15:284–300. doi: 10.33182/ml.v15i2.374

26. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster (1963).

27. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. (2001) 27:363–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

28. Bos AE, Pryor JB, Reeder GD, Stutterheim SE. Stigma: advances in theory and research. Basic Appl Soc Psych. (2013) 35:1–9. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2012.746147

29. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. (2006) 25:875. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875

30. Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. (2013) 103:813–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069

31. Adams J. Marked difference: tattooing and its association with deviance in the United States. Deviant Behav. (2009) 30:266–92. doi: 10.1080/01639620802168817

32. Lane DC. Tat's All folks: an analysis of tattoo literature. Sociology Compass. (2014) 8:398–410. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12142

33. Jennings WG, Fox BH, Farrington DP. Inked into crime? An examination of the causal relationship between tattoos and life-course offending among males from the cambridge study in delinquent development. J Crim Justice. (2014) 42:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2013.12.006

34. Funk F, Todorov A. Criminal stereotypes in the courtroom: facial tattoos affect guilt and punishment differently. Psychol. Public Policy, Law. (2013) 19:466–78. doi: 10.1037/a0034736

35. Stuppy DJ, Armstrong ML, Casals-Ariet C. Attitudes of health care providers and students towards tattooed people. J Adv Nurs. (1998) 27:1165–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00626.x

36. Bekhor PS, Bekhor L, Gandrabur M. Employer attitudes toward persons with visible tattoos. Aust J Dermatol. (1995) 36:75–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1995.tb00936.x

37. Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project (2010). Available online at: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/

38. Kluger N, Koljonen V. Chemical burn and hypertrophic scar due to misuse of a wart ointment for tattoo removal. Int J Dermatol. (2014) 53:e9–e11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05314.x

39. Armstrong ML, Roberts AE, Koch JR, Saunders JC, Owen DC, Anderson RR. Motivation for contemporary tattoo removal: a shift in identity. Arch Dermatol. (2008) 144:879–84. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.7.879

40. Madfis E, Arford T. The dilemmas of embodied symbolic representation: regret in contemporary American tattoo narratives. Soc Sci J. (2013) 50:547–56. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2013.07.012

41. Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, Cavigli A, Lavin BC, Murina A. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. (2015) 41:1283–9. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000500

42. Kent KM, Graber EM. Laser tattoo removal: a review. Dermatol Surg. (2012) 38:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02187.x

43. American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Laser Therapy for Unwanted Tattoos (2015). Available online at: https://www.asds.net/_PublicResources.aspx?id=6073

44. Poljac B, Burke T. Erasing the past: tattoo-removal programs for former gang members. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. (2008) 77:13–8. doi: 10.1037/e511472010-005

45. Yim GH, Hemington-Gorse SJ, Dickson WA. The perils of do it yourself chemical tattoo removal. Eplasty. (2010) 10:177–9.

46. Snelling A, Ball E, Adams T. Full thickness skin loss following chemical tattoo removal. Burns. (2006) 32:387–8. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2005.07.011

47. Leap J, Franke TM, Christie CA, Bonis S. Nothing Stops a Bullet Like a Job: Homeboy Industries Gang Prevention and Intervention in Los Angeles. In: Serra Hoffman J, Knox L, Cohen R, editors. Beyond Suppression: Global Perspectives on Youth Violence (Global Crime and Justice). Santa Barbara CA: Praeger (2011).

48. Deas A. Out Of The Darkness And Into The Light: Removing Gang Related and Offensive Tattoos - A Mixed Methods Study. San Jose State University (2008).

49. Beers K, Collins C, Sachez-Garcia M. Expanding Opportunity and Erasing Barriers: Tattoo Removal as a Gang Transition Strategy. Washington, USA: Whitman College (2014).

50. Golash-Boza T, Ceciliano-Navarro Y. Life after deportation. Contexts. (2019) 18:30–5. doi: 10.1177/1536504219854715

51. Pereira N. Pacific Island Nations, Criminal Deportees, and Reintegration Challenges. Migration Policy Institute (2014).

52. Bibler Coutin S. Exiled Home: Salvadoran Transnational Youth in the Aftermath of Violence. Duke University Press (2016). doi: 10.2307/j.ctv11g96sk

53. Wassink JT. Implications of mexican health care reform on the health coverage of nonmigrants and returning migrants. Am J Public Health. (2016) 106:848–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303094

54. Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. (2010) 63:1179–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011

55. Teresi JA, Ocepek-Welikson K, Kleinman M, Eimicke JP, Crane PK, Jones RN, et al. Analysis of differential item functioning in the depression item bank from the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS): an item response theory approach. Psychol Sci Q. (2009) 51:148–80.

56. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (1998).

57. Willms DG, Best JA, Taylor DW, Gilbert JR, Douglas MCW, Lindsay EA, et al. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. (1990) 4:391–409. doi: 10.1525/maq.1990.4.4.02a00020

58. Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousands Oak, CA: Sage (1994).

60. Alonso Olivares E. Se ha incrementado la discriminación contra migrantes en México, indican ONG. La jOrnada. (2019). Available online at: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2019/07/29/politica/012n1pol

61. Cornelius WA, Salehyan I. Does border enforcement deter unauthorized immigration? The case of Mexican migration to the United States of America. Regul Gov. (2007) 1:139–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00007.x

62. Kosack E. Guest worker programs and human capital investment the bracero program in mexico, 1942–1964. J Hum Resour. (2021) 56:570–99. doi: 10.3368/jhr.56.2.0616-8015R2

63. Instituto Nacional de Migracion: Gobierno de Mexico. En Mexico Hay Oportunidades Para Los Repatriados! Mexico, DF: Gobierno de Mexico (2016). Available online at: https://www.gob.mx/inm/articulos/en-mexico-hay-oportunidades-para-los-repatriados?idiom=es

64. Sullivan MM, Rehm R. Mental health of undocumented Mexican immigrants: a review of the literature. Adv Nurs Sci. (2005) 28:240–51. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200507000-00006

65. Flynn MA, Eggerth DE, Jacobson CJ Jr. Undocumented status as a social determinant of occupational safety and health: the workers' perspective. Am J Ind Med. (2015) 58:1127–37. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22531

66. Instituto Nacional Electoral: Gobierno de Mexico. Detalles de la solicitud para la Credencial para Votar. Mexico, DF2019.

67. World Bank. World Band Country and Lending Groups Washington, DC2021. Available online at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

68. Publimetro. 527 mil niños y adolescentes mexicanos sin acta de nacimiento: Inegi. Publimetro (2019).

69. Mexico U,. El Derecho a la Identidad Mexico DF: UNICEF Mexico. (2019). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/mexico/el-derecho-la-identidad

70. Insituto Nacional de Migracion: Gobierno de Mexico. Programa de Repatriacion Mexico, DF: Gobierno de Mexico (2019). Available online at: https://www.gob.mx/inm/acciones-y-programas/programa-de-repatriacion-12469

71. Ojeda VD, Romero L, Ortiz A. A model for sustainable laser tattoo removal services for adult probationers. Int J Prison Health. (2019). doi: 10.1108/IJPH-09-2018-0047

73. Ojeda VD, Magana C, Hiller-Venegas S, Romero LS, Ortiz A. Motivations for seeking laser tattoo removal and perceived outcomes as reported by justice involved adults. Int sJ Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2022:0306624X221102807. doi: 10.1177/0306624X221102807

74. REMOVINK. Blog: Cuanto Cuesta Borrar Un Tatuaje (2017). Available online at: http://removink.mx/2017/04/18/cuanto-cuesta-borrar-un-tatuaje/

Keywords: Mexico, tattoo removal, tattoo stigma, migration, deportation

Citation: Ojeda VD, Magana C, Shalakhti O, Vargas-Ojeda AC and Burgos JL (2022) Tattoo discrimination in Mexico motivates interest in tattoo removal among structurally vulnerable adults. Front. Public Health 10:894486. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.894486

Received: 11 March 2022; Accepted: 11 July 2022;

Published: 18 August 2022.

Edited by:

Stefania Cella, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyReviewed by:

Annarosa Cipriano, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyMarco Scotto Rosato, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Ojeda, Magana, Shalakhti, Vargas-Ojeda and Burgos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria D. Ojeda, dm9qZWRhQGhlYWx0aC51Y3NkLmVkdQ==

Victoria D. Ojeda

Victoria D. Ojeda Christopher Magana

Christopher Magana Omar Shalakhti

Omar Shalakhti Adriana Carolina Vargas-Ojeda

Adriana Carolina Vargas-Ojeda Jose Luis Burgos

Jose Luis Burgos