- 1Division of Behavioral Sciences, National Cancer Center Institute for Cancer Control, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Division of Supportive Care, Survivorship and Translational Research, National Cancer Center Institute for Cancer Control, Tokyo, Japan

- 3Innovation Center for Supportive, Palliative and Psychosocial Care, National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Introduction: Workplace programs to prevent non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in the workplace can help prevent the incidence of chronic diseases among employees, provide health benefits, and reduce the risk of financial loss. Nevertheless, these programs are not fully implemented, particularly in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The purpose of this study was to develop implementation strategies for health promotion activities to prevent NCDs in Japanese SMEs using Implementation Mapping (IM) to present the process in a systematic, transparent, and replicable manner.

Methods: Qualitative methods using interviews and focus group discussions with 15 SMEs and 20 public health nurses were conducted in a previous study. This study applied the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and IM to analyze this dataset to develop implementation strategies suitable for SMEs in Japan.

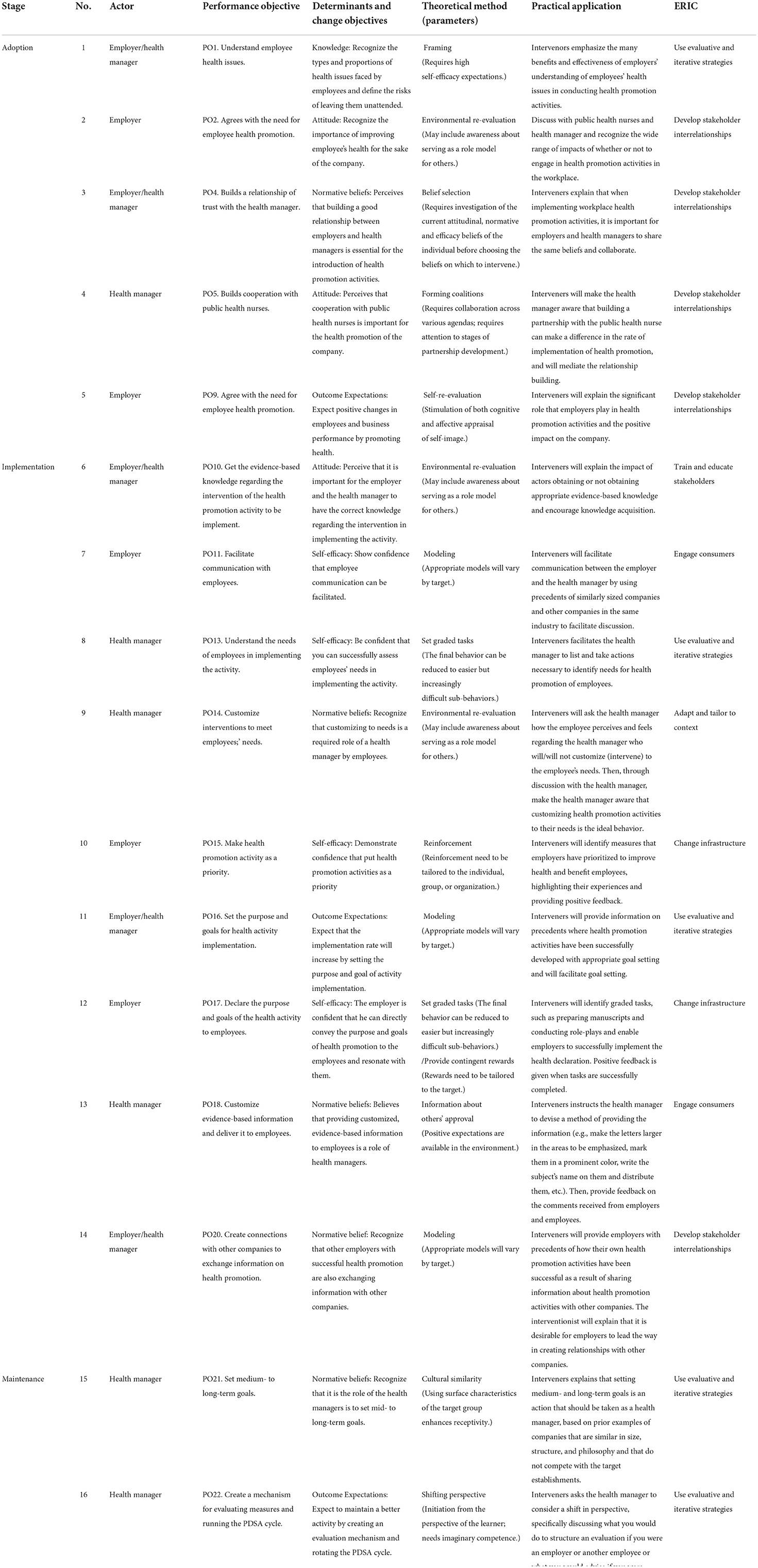

Results: In task 2 of the IM, we identified performance objectives, determinants, and change objectives for each implementation stage: adoption, implementation, and maintenance; to identify the required actors and actions necessary to enhance implementation effectiveness. Twenty-two performance objectives were identified in each implementation stage. In task 3 of the IM, the planning group matched behavioral change methods (e.g., modeling and setting of graded tasks, framing, self-re-evaluation, and environmental re-evaluation) with determinants to address the performance objectives. We used a consolidated framework for implementation research to select the optimal behavioral change technique for performance objectives and determinants and designed a practical application. The planning team agreed on the inclusion of sixteen strategies from the final strategies list compiled and presented to it for consensus, for the overall implementation plan design.

Discussion: This paper provides the implementation strategies for NCDs prevention for SMEs in Japan following an IM protocol. Although the identified implementation strategies might not be generalizable to all SMEs planning implementation of health promotion activities, because they were tailored to contextual factors identified in a formative research. However, identified performance objectives and implementation strategies can help direct the next steps in launching preventive programs against NCDs in SMEs.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) kill 41 million people each year, equivalent to 71% of all deaths globally (1). Tobacco use, physical inactivity, harmful use of alcohol, and an unhealthy diet increase the risk of dying from NCDs (1). In Japan, four of the top five leading causes of mortality in 2019 are NCDs (i.e., Alzheimer's disease, stroke, ischemic heart disease, and lung cancer), and NCDs account for more than 80% of all health losses measured using the disability-adjusted life years (2, 3). The World Health Organization has identified workplaces as valuable access points for providing interventions targeting NCD prevention (4). In effect, workplaces provide many adults with opportunities for health promotion. Workplace health promotion programs are effective in modifying dietary behavior (5), tobacco use (6), and physical activity (7, 8). Furthermore, workplaces have existing infrastructure to provide comprehensive health promotion and disease management programs (9). Thus, workplace health promotion activities could make a significant contribution to population level reductions in chronic disease risk (10, 11).

Companies in developed countries are increasingly providing workplace health promotion programs, but the implementation in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is limited compared with that in larger companies. For example, in 2018, 82% of large firms and 53% of small enterprises in the United States offered a wellness program (12). Similarly, occupational health activities at SMEs in Japan are lagging in large companies (13). A recent national survey in Japan showed that although SMEs have become increasingly interested in workplace health promotion, only 20% are engaged in any type of health-promoting activities (14).

The challenges smaller workplaces face in offering workplace health promotion programs include having few vendors to serve them, low commitment to and internal capacity for program delivery (15), and limited direct or administrative costs of running programs (16). The identified barrier in Japanese SMEs also includes the beliefs held by the employer/manager that health management is one's own responsibility (17). Furthermore, as smaller workplaces often have high employee turnover rates, investing in workplace health promotion programs designed to prevent chronic diseases made little sense to employers (18).

New approaches are needed that are tailored to each context to overcome these barriers at SMEs. Implementation strategies are defined as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice” (19). Empirical studies in clinical settings show that implementation strategies, such as audit and feedback (20), training (21), and academic detailing (22), improve the implementation of evidence-based policies and practices. A systematic review regarding implementation strategies to improve health promotion policies or practices at the workplace identified six studies and found no conclusive evidence regarding the effects of those strategies (23), which may be partly due to the limited use of theory to design implementation strategies (24). Four out of the six included studies reported using theoretical, practical, or conceptual frameworks; however, these studies were used to understand the context rather than for the development of implementation strategies (23). Since the process of identifying implementation strategies is not clearly documented, it is difficult to understand which strategies work and why they work (25). Therefore, identifying implementation strategies that address barriers to implementation after a comprehensive formative evaluation with theoretical frameworks may be the most effective approach for maximizing the impact of implementation strategies in the workplace (23).

Implementation Mapping (IM) is derived from intervention mapping, which is one of the several methods (concept mapping, group model building, conjoint analysis, intervention mapping, etc.) that can be used to select implementation strategies to address the barriers and facilitators of specific evidence-based practices (26). Specifically, IM identifies implementation strategies that have the greatest potential impact on implementation and health outcomes and addresses the barriers to implementation after a comprehensive formative evaluation using theoretical frameworks (27). Moreover, IM can provide a systematic process for selecting the implementation strategies needed to overcome the barriers to implementation (27). The use of a systematic process has the advantage of increasing reproducibility, and the use of relevant theory has the advantage of increasing the likelihood of identifying the mechanism of action of implementation strategies (25). Therefore, in this study, we decided for IM as it can be used to systematically design implementation strategies. The purpose of this study was to develop implementation strategies for health promotion activities to prevent NCDs in Japanese SMEs using IM, to present the process in a systematic, transparent, and replicable manner.

Methods

Theoretical framework

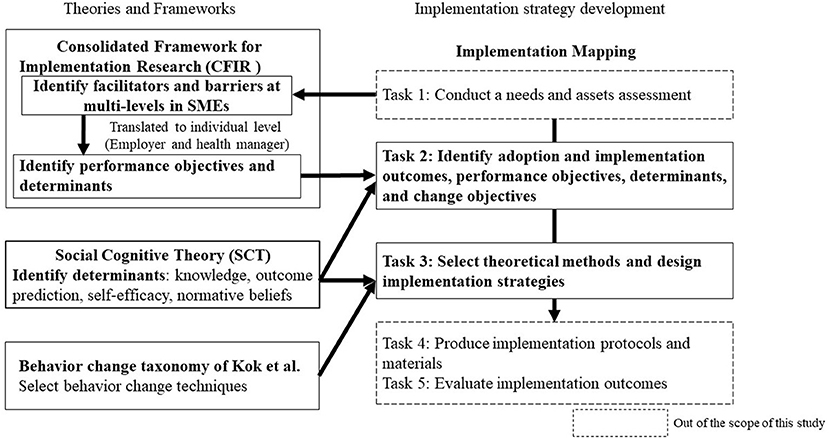

In this study, we designed the implementation strategies for health promotion activities to prevent NCDs by using the IM framework, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (28), social cognitive theory (29), and behavioral change taxonomy of Kok et al. (30) (Figure 1).

We selected evidence-based interventions that public health nurses as external change agents could support for implementation in the workplace in Japan: modifying dietary behavior (e.g., menu modification at cafeteria with nutrition education) (5), tobacco use (e.g., in combination with counseling, pharmacological treatment, and smoke-free polices) (6), and physical activity (e.g., physical activity program with pedometer delivery and tailored e-mail message) (7, 8).

The IM process consisted of five tasks: tasks 1 to 5. In this study, we used tasks 2 and 3 to develop implementation strategies for the adoption, implementation, and maintenance of workplace cancer prevention programs (Figure 1). CFIR, a meta-framework, includes five domains: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and the process (28). We used CFIR because it is important to have a comprehensive understanding of the barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation process at different levels in SMEs, which can then be used to identify context-specific implementation strategies (17). In this study, we used CFIR primarily to identify performance objectives and determinants for task 2. Similarly, we also used the social cognitive theory model (29), which can identify personal determinants and predictive relationships that promote implementation behavior, to identify the determinants of task 2. In task 3, behavioral change techniques had to be logically followed based on the determinants (27). Therefore, we used the behavior change taxonomy provided by Kok et al. (30) as prominent health behavior theories are known to influence behavioral determinants. The social cognitive theory was also used as a reference when selecting the method of behavioral change.

Task 1: Conduct needs and assets assessments and identify actors

Task 1 was conducted prior to this study and has been published as an original publication (17). In this previous study, we identified several barriers and facilitative factors of SMEs using CFIR through the semi-structured interviews with employers and health managers (17). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with health managers and/or employers in 15 enterprises with <300 employees and four focus group discussions with 20 public health nurses/nutritionists at the Japan Health Insurance Association (JHIA) branch offices that support SMEs in four prefectures across Japan. In the previous study, we reported that of the 39 CFIR constructs, 25 were facilitative and 7 were inhibitory for workplace health promotion implementation in SMEs at individual, internal, and external levels. In particular, the leadership engagement of employers in implementing the workplace health promotion activities was identified as a fundamental factor that may influence other facilitators, including “access to knowledge and information,” “relative priority,” and “learning climate” at organizational level, as well as “self-efficacy” at the health manager level. The main barrier was the beliefs held by the employer/manager that “health management is one's own responsibility” (17). Thereafter, we identified employers and health managers as actors because health managers are the implementers of health promotion activities, and employers have the greatest influence on SMEs. Thus, we aimed to develop implementation strategies targeting employers and health managers. In this study, we translated the barriers and facilitators identified in the previous study (17) at the individual level and used them primarily to identify performance objectives and determinants for task 2.

Formation of an implementation strategy planning team

We formed an implementation strategy planning team to guide the IM process. The group consisted of an academic team whose members specialized in psychology, public health, and epidemiology, as well as three public health nurses with at least 10 years of experience in workplace health promotion activities affiliated with the JHIA. JHIA is the largest medical insurer in Japan covering ~2.4 million enterprises (31, 32). Since most of the member companies of JHIA are SMEs (33), JHIA represents the insurers of SMEs, and more than 90% of them have <30 employees (33). In Japan, public health nurses work at various health care facilities, including publicly funded or government health insurance associations that provide health care services for workers in SMEs (34). In addition, public health nurses have recently been providing support to promote health promotion activities in SMEs and in envisioning enterprises that are members of the JHIA, as sites for implementation. We held discussions with the JHIA head office and obtained their agreement and full cooperation to promote health promotion activities in SMEs. Considering this background of public health nurses' activities in Japan along with the previous research and literature reviews conducted by the academic team and the importance of JHIA's role in scaling up the intervention, we pre-determined public health nurses affiliated with the JHIA as stakeholders for the adoption, implementation, and maintenance of health promotion activities.

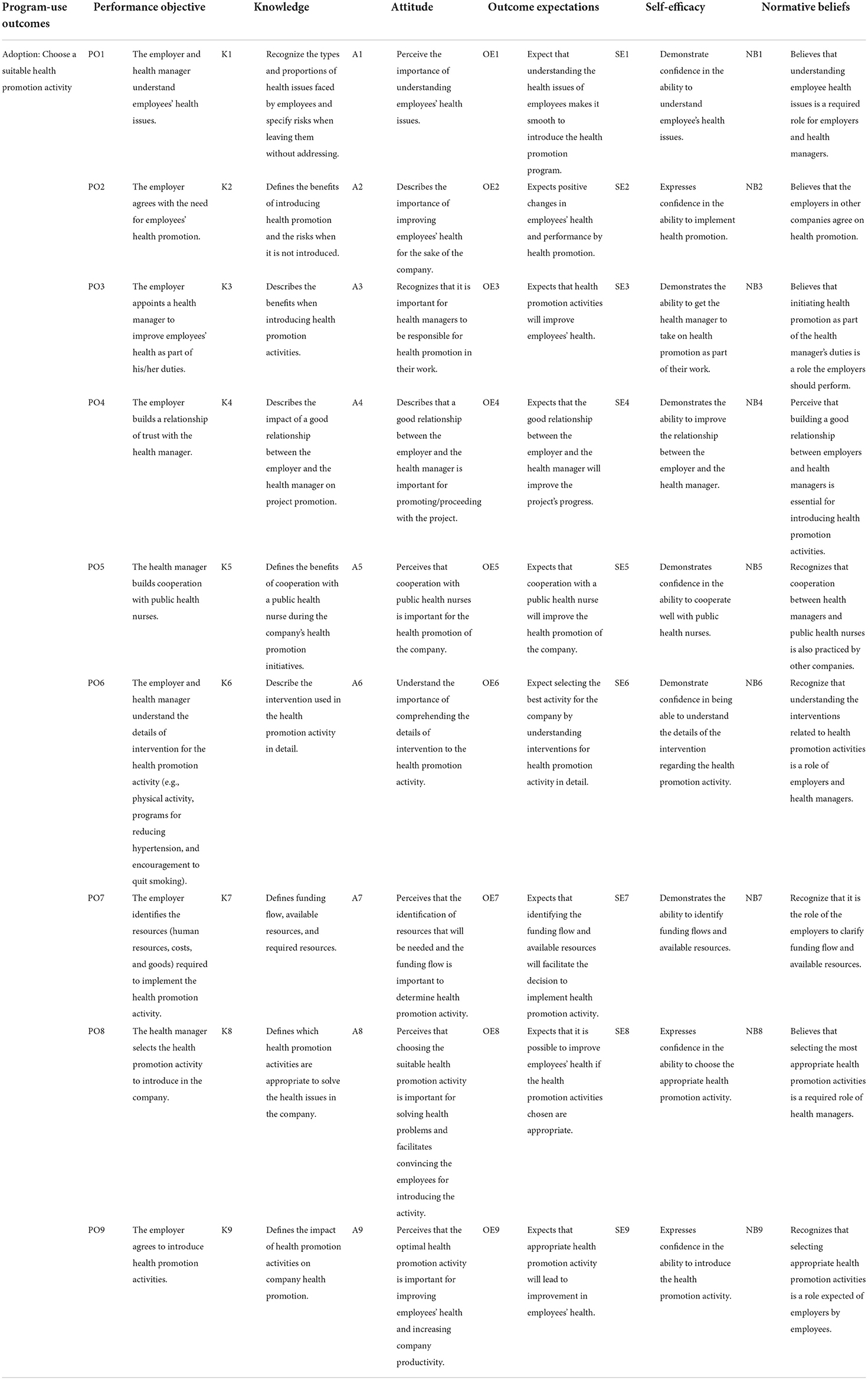

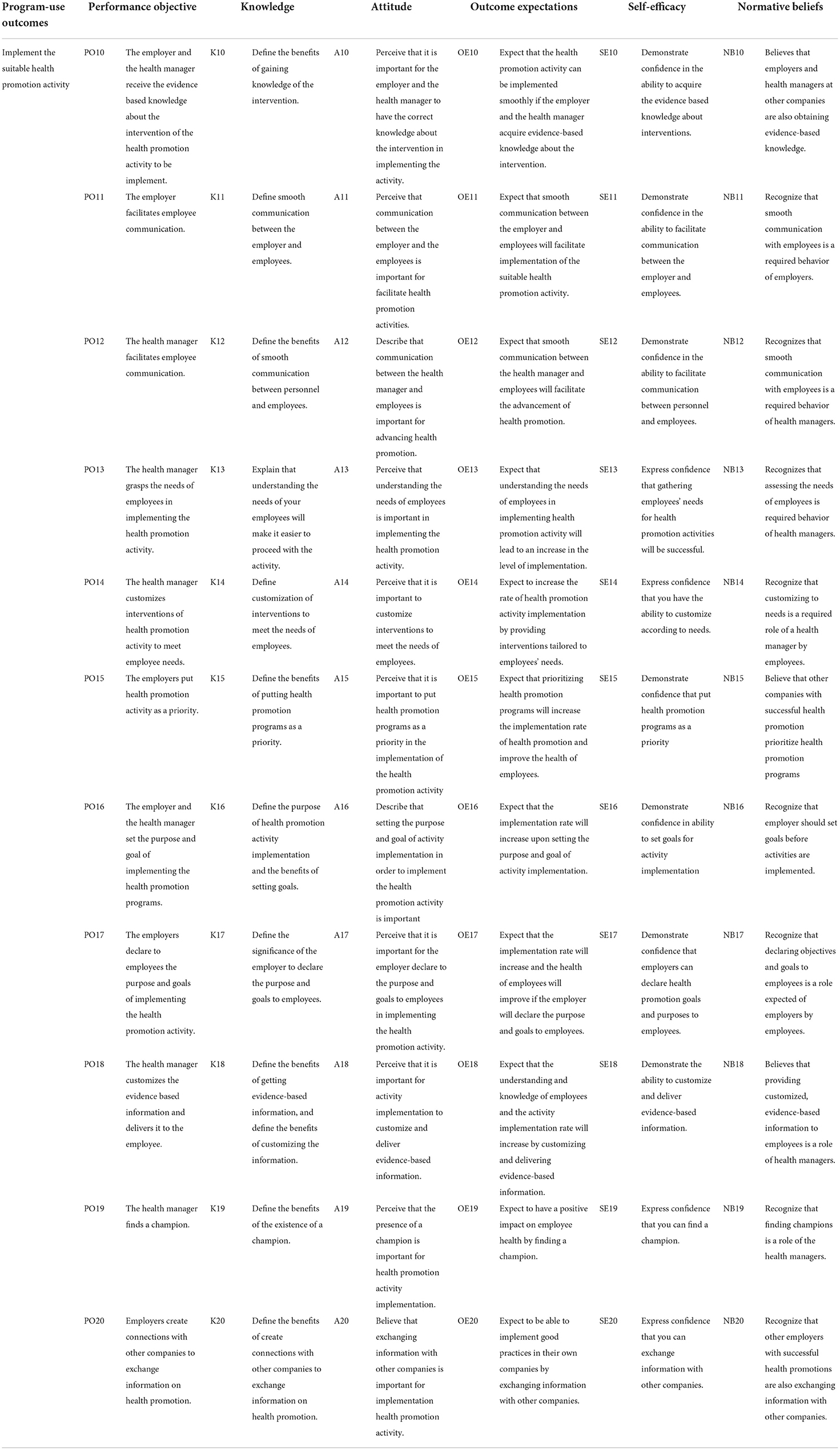

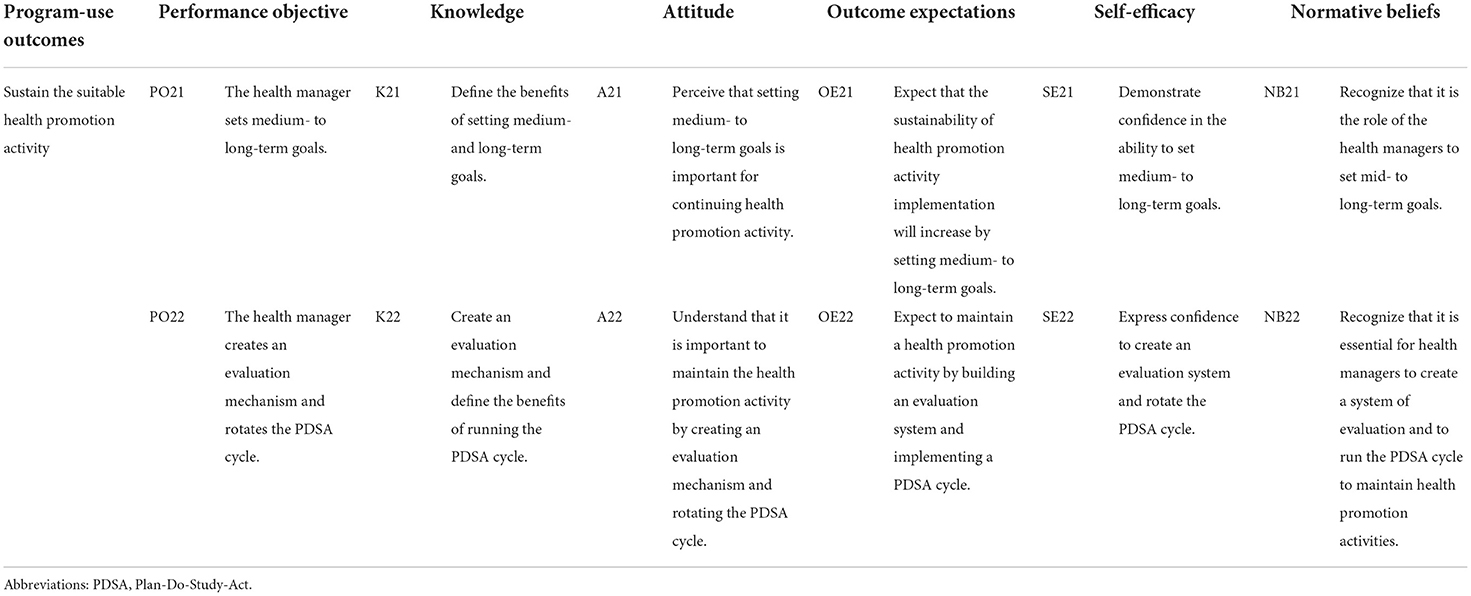

Task 2: Identifying adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes; performance objectives; determinants; and change objectives

In task 2, we identified the program-use outcomes and the performance objectives for each implementation stage as adoption, implementation, and maintenance because the actor who adopts, and those who implements and maintains programs will be often different. First, we determined the program-use outcomes based on each implementation stage definition (35): “adoption is the decision to use a new program; implementation is the use of the program over a long enough period to allow for evaluation regarding the innovation and whether it meets the perceived need; and maintenance is the extent to which the program is continued, and then becomes a part of normal practices.” We then selected the performance objectives necessary to achieve the program-use outcomes. The performance objectives denoted specific behaviors of those who needed to act if the change was to occur. As such, the performance objectives are action-oriented and do not include cognitive processes such as knowing and believing (27). To formulate the determinants, we used the barriers identified in task 1 and social cognitive theory (Figure 1). The academic team developed draft performance objectives that should be achieved by employers and health managers to implement the programs based on the facilitators identified in task 1, and used CFIR to provide answers to “What do the program implementers need to do to deliver the essential program components?” Since the interventionists envisioned in this workplace health promotion activities are public health nurses in JHIA, we focused on performance objectives in which public health nurses can intervene. We refined the draft performance objectives, through discussion with the public health nurses, and divided them into implementation stages of adoption, implementation, and maintenance to achieve the program-use outcomes. We then sought input from the SMEs employers and health managers who participated in the task 1 interviews, and selected performance objectives based on the feasibility, especially in terms of financial and human resources. This was done to overcome one of the barriers to implementing health promotion programs in SMEs: low available human resources and limited economic costs (15, 16). Subsequently, a matrix based on the combination of performance objectives and individual determinants of the theory of action was created. Next, we identified the personal determinants of the actors. Determinants answered the question “why,” and the barriers and facilitators of adoption were also deemed as determinants (27). We identified the determinants for each stage in a brainstorming session where the academic team answered the questions, “why do employers not understand their employees' health issues?” and “why are employers not making workplace health promotion activities a priority?” Therefore, we derived the personal determinants from the barriers identified in task 1 and the social cognitive theory model (29). In Tables 1–3, the second column of the matrix contains the performance objectives, while the other column headings are the determinants. The change objectives required to achieve each performance objective are listed under the headings in the determinant's column of the matrix. Three different matrices were created for each implementation stage of the program: Adoption (Table 1), Implementation (Table 2), and Maintenance (Table 3). In developing the matrices for task 2, the academic team held weekly discussions to reach a consensus and asked the employers and health managers of the SMEs who participated in the interviews in task 1 to share their opinions on the draft performance objectives. We sent an email to the SMEs with a draft of the performance objectives, followed by a 30-min telephonic interview with each SME. We then spent a month to make decisions after two 1-h discussions with the public health nurses. Specifically, the academic team developed a draft matrix, held online meetings with public health nurses, and revised the matrix, confirming that the change objectives were feasible and capable of achieving the performance objectives.

Task 3: Select theoretical methods and design implementation strategies

Task 3 aimed to select a theoretical method and design implementation strategies. We selected suitable behavioral change techniques using the behavior change taxonomy of Kok et al. (30) for each determinant of the matrix created in task 2. This taxonomy outlines ways to change perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, outcome expectations, skills, abilities, self-efficacy, environmental conditions, social norms, social support, organizations, communities, and policies. In selecting behavioral change techniques, as in task 2, the academic team created a draft and revised it through online or in-person discussions with the public health nurses. These discussions were held over the course of a month and involved two 1-h discussions with the public health nurses on two occasions.

Results

The results are presented by IM task.

Task 2: Identify adoption, implementation, and maintenance outcomes; performance objectives; determinants; and change objectives

For this task, we identified the program-use outcomes, performance objectives (“What had to be done by whom to implement the program?”), determinants (“Why would an actor perform the program as planned?”), and change objectives (“What has to change in this determinant in order to bring about the performance objective?”), for each implementation stage. Tables 1–3 show the program-use outcome, the subsequent specific steps required to meet them (i.e., performance objectives), determinants, and change objectives for each implementation stage. For the adoption stage, we set the program-use outcome as “choosing health promotion activities that are suitable for the company's health issues.” Therefore, we set the performance objectives as the process of team building to adopt health promotion activities, such as “employer identification of employee's health issues” and “building trust between employers and health managers.” We selected these performance objectives from the facilitators at the “inner setting” and “process” CFIR domains (in particular “readiness for implementation,” “implementation climate,” and “formally appointed internal implementation leaders”) (Table 1).

We set the program-use outcome for the implementation stage as implementing health promotion activities appropriate to the company's health issues (Table 2). For instance, we chose the performance objective to include the health manager assessing the needs of the employees and customizing the intervention, and the employer setting the objectives and goals of the health promotion activities, and declaring them to the employees. We selected these from the “outer setting” (e.g., “needs and resources of those served by the organization”) and “inner setting” (especially “leadership engagement” and “goals and feedback”) facilitators of the CFIR domains. In addition, we also chose “employers to connect with other businesses and exchange information on health promotion” for the performance objectives, based on information from the CFIR domain “cosmopolitanism.” We set the program-use outcome for the maintenance stage to sustain health promotion activities (Table 3). Therefore, we chose the performance objectives to include mid-to long-term goal setting and evaluation of health promotion activities. These were selected from the facilitators of the “process” (“reflecting and evaluating”) CFIR domain.

Subsequently, we identified the determinants of the barriers to task 1 and social cognitive theory. The primary barrier was the belief held by the employers or managers that “health care is a self-responsibility” with information from the CFIR domain characteristics of individuals (17). We adopted this as a determinant factor as “attitude”, which implies a low awareness of the importance of health promotion activities in the workplace. Furthermore, from the theoretical determinants of the social cognitive theory, we employed knowledge, outcome prediction, self-efficacy, and normative beliefs as the determinants of relevance for performance objective.

With the performance objectives and determinants established, task 2 outcomes were used in the creation of the matrix of change objectives for each stage. We identified 22 performance objectives and 5 determinants (i.e., knowledge, attitudes, outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and normative beliefs). Change objectives (written where the matrix rows and columns intersect) reflected the changes in the five determinants that were needed for the performance objectives to be completed successfully for each implementation stage of health promotion activities. We received opinions from the employers and health care managers, primarily for performance objectives, whether they were appropriate to achieve program use outcomes in each implementation stage, and whether they were feasible with the support of public health nurses. The public health nurses advised the academic team, based on their experience in health promotion support activities, to set feasible performance objectives with respect to cost and human resources. The academic team revised and finalized the performance objective based on their advice.

Task 3: Select theoretical methods and design implementation strategies

The planning team selected discrete implementation strategies to operationalize performance objectives.

First, we selected behavioral change techniques from the taxonomy of behavioral change methods (30) (e.g., modeling and setting of graded tasks [social cognitive theory], framing [protection motivation theory], self-re-evaluation, and environmental re-evaluation [transtheoretical model]). These behavioral change techniques were selected according to the following three criteria: (1) the interventionists could use convincing language to encourage the adoption and implementation of the program, (2) the methods could be used even by non-expert health professionals, and (3) they considered the real-life work environment and Japanese culture. We decided on these criteria through discussions with the public health nurses.

Second, we selected behavioral change techniques for each determinant regarding social cognitive theory and designed practical applications. For example, the behavioral change technique, modeling, is known to be associated with normative beliefs, outcome expectations, and self-efficacy (29).

Information on health promotion activities in other SMEs could improve organization leadership's receptiveness to adopting workplace programs. Furthermore, information on the role of other employers in health promotion activities could help them acquire their own role models and predict positive outcomes. Therefore, modeling was selected as a method of behavioral change for the determinants of normative beliefs, outcome expectations, and self-efficacy. We then designed the practical application of modeling to address the performance objective-14 as, “to provide employers with precedents of how their own health promotion activities have been successful as a result of sharing information regarding health promotion activities with other companies.” In addition, the interventionist would explain that it is desirable for employers to take the lead in creating relationships with other companies (Table 4). This task was completed in 1 month with the planning team meeting weekly to review the outputs of task 3, review and discuss the literature, and iteratively update the list of change methods and practical applications. The team discussed the determinants most strongly associated with each performance objective and agreed to include 16 discrete strategies in the overall implementation plan design. Table 4 summarizes the agents, determinants, methods of change, and discrete strategies used according to the implementation phase of the health promotion activities in the implementation strategies. In addition, to compare with previous reviews, the academic team discussed and reached a consensus on where the practical application corresponds to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy and included it in Table 4.

Table 4. Implementation strategies in health promotion activities within small- to medium-enterprises.

Discussion

In this paper, we described how we developed implementation strategies for health promotion activities to prevent NCDs in SMEs. Sixteen strategies for implementing health promotion activities were developed from multiple perspectives of employers and health managers from SMEs, public health nurses, and researchers, including how to improve the programs, while receiving feedbacks from within and outside the company and being aware of social desirability.

In this study, we selected discrete implementation strategies according to the context and determinants of the organizations. Implementation strategies have different effects depending on the determinants (barriers and facilitators) (36), and the context and barriers to implementation need to be properly understood to select strategies that best address them (37). Moreover, we involved the stakeholders, the headquarters of JHIA, to build the strong partnerships needed for implementation. Strong partnerships must be necessary when it comes to changing organizational-level systems (38). For example, when considering methods to change physician behaviors, individual doctors cannot be expected to change without corresponding changes in healthcare teams and the overall organization (39). Likewise, in this study, partnership with public health nurses in JHIA was an essential element because the implementation of health promotion activities requires system changes that need to be integrated into the usual workflows at the organizational level, and also the importance of JHIA's role in scaling up the intervention in the future.

Moreover, the discrete implementation strategies we derived through IM have been reported in a systematic review of implementation strategies (23) as follows: the “develop stakeholder interrelationships” (40) (e.g., the employer agrees with the need for employees' health promotion and the health manager builds cooperation with public health nurses) in the adoption phase of our intervention; “train and educate stakeholders” (40) (e.g., the employer and health manager receive the evidence-based knowledge about the intervention of the health promotion activity to be implemented) in the implementation stage; and use evaluative and iterative strategies” (40) (e.g., the health manager sets medium- to long-term goals) in the maintenance stage. These consistencies with well-established barriers and strategies enhance the validity of our process and results and predict a degree of generalizability to other settings.

However, we identified two implementation strategies that were not found in the previous systematic review. The first strategy was to “engage consumers” (40), which is related to attentiveness and communication. For example, the health manager at SMEs customizes the content and delivery methods of evidence-based information according to the characteristics of each employee. This strategy would reflect the advantage of SMEs, which is more accommodating (16) and provides a more intimate work culture due to fewer employees, thus encouraging employees to participate in health promotion activities (41).

The second strategy involves “change in infrastructure” (40), wherein employers prioritize health promotion programs and establish the purpose and goals of implementing health promotion activities among their employees. Furthermore, it involves the “development of stakeholder interrelationships” (40), wherein employers build connections with other companies to exchange information on health promotion in the workplace; and this may generate a modeling effect across companies. These strategies, newly identified in our study, appear to reflect the Japanese culture. The declarations made by employers have a strong impact on Japanese employees, who tend to be obedient to their superiors. In the interviews conducted as part of our previous study, there was an opinion that the progress of the business would be different if there was “a word from the top” or the employer (17). In addition, the creation of horizontal connections makes “modeling” possible and makes it easier to create behavioral changes with an awareness of social norms. In Asian societies, especially in Japan, social norms are strict, with duties and obligations taking precedence (42, 43). Therefore, learning about health promotion activities in other companies generates a belief that the activities being performed in other companies should also be performed in their companies. Moreover, those norms and beliefs are often created by the opinions and attitudes of employers in SMEs. Therefore, it is an effective implementation strategy aimed at fostering the norms about health promotion activities in the company by encouraging employers to change their knowledge, attitudes, and norms.

These newly identified implementation strategies for workplace health promotion could be attributed to the focus on SMEs and the fact that we used IM to derive strategies based on real-world opinions. The implementation strategies of large businesses cannot be generalized to SMEs due to their different contexts (16), and there is a need for strategies that are optimal for the challenges faced by SMEs. Further studies to identify implementation strategies that consider the characteristics of SMEs would promote the efforts of the SMEs to overcome the barriers to the adoption and implementation of workplace health promotion.

The implementation strategies designed in this study are primarily for health promotion activities in SMEs, focusing on five NCD prevention measures (i.e., tobacco use, alcohol consumption, diet, physical activity, and health check-ups). We are currently developing protocols and materials according to task 4 of IM, which is being evaluated in a researcher-led pilot study, to implement an intervention focused on one (smoking cessation) of these five topics (44). The main focus of the workplace smoking cessation strategy is to encourage healthcare managers to encourage smokers in the workplace to quit smoking, so that SMEs with limited resources can implement it. The goal is to reduce the prevalence of smoking while providing implementation strategies tailored to the disincentive. If the pilot study confirms the effectiveness of the implementation strategies, public health nurses at JHIA will participate in the national scaling up of the program. Among employees in SMEs, the proportions of health and behavioral problems, such as hypertension, obesity, and smoking, were higher than those in employees from larger organizations (45). Therefore, employers in SMEs must make a serious effort to promote the health of their employees and prioritize health-promoting programs.

This study has several limitations. In the selection of behavioral change techniques and development of practical applications (task 3), there was insufficient involvement of SMEs. Furthermore, in task 2, employers and health managers of the SMEs were involved, but not their employees. In addition, planning with public health nurses was not a participatory approach, but rather a form of listening to their opinions. This is because it is not yet common in Japan for stakeholders in the field to be actively involved in research. Since this was our first implementation study with SMEs and JHIA, we had to be careful not to place a burden on SMEs and JHIA during this period. As a result of this background, it is possible that the opinions of the SMEs and public health nurses were not fully reflected in the field, or that they were insufficient to foster a proactive attitude among SMEs and public health nurses toward health promotion activities in the workplace. Additionally, it may take time for SMEs and public health nurses to incorporate these strategies into their workflow. This is because researcher-led implementation creates a perception of “somebody else's business,” i.e., that an external change agent, the researcher, will take care of the company's health activities.

The selection of the implementation strategies was tailored to the context of SMEs in Japan, where health promotion activities are already being implemented, and may not be effective in other settings because the strategy may not resonate with other settings, such as the limited readiness of the employer to implement the health promotion. However, in countries and communities like Japan, where the social norms influence behavior, it may be effective, but this needs to be verified.

This study developed implementation strategies for health promotion activities in SMEs in Japan by applying IM in conjunction with the constructs of the CFIR framework, social cognitive theory, and behavioral change techniques. To our knowledge, there are only a few studies that applied and integrated these three frameworks and techniques simultaneously to develop implementation strategies. The IM protocol provided a valuable guideline for the development of comprehensive implementation strategies. The identified performance objectives and implementation strategies can help direct further steps in launching health promotion activities to prevent NCDs in SMEs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical Committee of the National Cancer Center. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MO and TS conceived of the paper and designed the study. MO, JS, AY-S, and TS were members of the academic team of the implementation strategy planning group and developed the implementation strategy according to the IM protocol. MO drafted the initial manuscript and all authors revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. TS was the principal investigator of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center Consortium in Implementation Science for Health Equity (N-EQUITY) and funded by the Japan Health Research Promotion Bureau (JH) Research Fund (2019-(1)-4) and JH Project fund (JHP2022-J-02), the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (30-A-18 and 2021-A-19), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Numbers JP21K17319 and JP22H03326).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to the public health nurses of the JHIA who participated in the implementation strategy planning. This study received guidance from N-EQUITY. We are grateful to Hanako Saito for her cooperation in this study as a research staff.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CFIR, consolidated framework for implementation research; IM, Implementation Mapping; NCD, non-communicable disease; SMEs, small- and medium-sized enterprises.

References

1. World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases (NCD). Available online at: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en/ (accessed January 07, 2021).

2. Nomura S, Sakamoto H, Ghaznavi C, Inoue M. Toward a third term of Health Japan 21—Implications from the rise in non-communicable disease burden and highly preventable risk factors. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. (2022) 21:100377. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100377

3. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease (GBD). (2020). Available online at: http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/2019 (accessed October 29, 2020).

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy for Health for All by 2000. Geneva: WHO Press (1981).

5. Geaney F, Kelly C, Greiner BA, Harrington JM, Perry IJ, Beirne P. The effectiveness of workplace dietary modification interventions: a systematic review. Prev Med. (2013) 57:438–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.032

6. Cahill K, Lancaster T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2014) (2):Cd003440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003440.pub4

7. Malik SH, Blake H, Suggs LS, A. systematic review of workplace health promotion interventions for increasing physical activity. Br J Health Psychol. (2014) 19:149–80. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12052

8. To QG, Chen TT, Magnussen CG, To KG. Workplace physical activity interventions: a systematic review. Am J Health Promot. (2013) 27:e113–23. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.120425-LIT-222

9. Pelletier KR, A. Review and analysis of the clinical and cost-effectiveness studies of comprehensive health promotion and disease management programs at the worksite: update Viii 2008 to 2010. J Occup Environ Med. (2011) 53:1310–31. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182337748

10. Mattke S, Liu H, Caloyeras J, Huang CY, Van Busum KR, Khodyakov D, et al. Workplace wellness programs study: final report. Rand Health Q. (2013) 3:7. doi: 10.7249/RR254

11. Proper KI, van Oostrom SH. The effectiveness of workplace health promotion interventions on physical and mental health putcomes—a systematic review of reviews. Scand J Work Environ Health. (2019) 45:546–59. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3833

12. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018 Employer Health Benefits Survey (2018). Available online at: https://Www.Kff.Org/Health-Costs/Report/2018-Employer-Health-Benefits-Survey/ (accessed February 18, 2021).

13. Nishikido N, Yuasa A, Motoki C, Tanaka M, Arai S, Matsuda K, et al. Development of multi-dimensional action checklist for promoting new approaches in participatory occupational safety and health in small and medium-sized enterprises. Ind Health. (2006) 44:35–41. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.35

14. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Available online at: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/2r9852000001qjfu-att/2r9852000001qjk8.pdf. (accessed July 29, 2021).

15. Harris JR, Hannon PA, Beresford SA, Linnan LA, McLellan DL. Health promotion in smaller workplaces in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. (2014) 35:327–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182416

16. McCoy K, Stinson K, Scott K, Tenney L, Newman LS. Health promotion in small business: A systematic review of factors influencing adoption and effectiveness of worksite wellness programs. J Occup Environ Med. (2014) 56:579–87. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000171

17. Saito J, Odawara M, Takahashi H, Fujimori M, Yaguchi-Saito A, Inoue M, et al. Barriers and facilitative factors in the implementation of workplace health promotion activities in small and medium-sized enterprises: a qualitative study. Implement Sci Commun. (2022) 3:23. doi: 10.1186/s43058-022-00268-4

18. Hannon PA, Hammerback K, Garson G, Harris JR, Sopher CJ. Stakeholder perspectives on workplace health promotion: a qualitative study of midsized employers in low-wage industries. Am J Health Promot. (2012) 27:103–10. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.110204-QUAL-51

19. Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

20. Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2012) (6):Cd000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3

21. Forsetlund L, Bjørndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2009) 2009:Cd003030. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003030.pub2

22. O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2007) 2007:Cd000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2

23. Wolfenden L, Goldman S, Stacey FG, Grady A, Kingsland M, Williams CM, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of workplace-based policies or practices targeting tobacco, alcohol, diet, physical activity and obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 11:Cd012439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012439.pub2

24. Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM, A. Systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-14

25. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:42. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0892-4

26. Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, Aarons GA, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, et al. Methods to improve the selection and tailoring of implementation strategies. J Behav Health Serv Res. (2017) 44:177–94. doi: 10.1007/s11414-015-9475-6

27. Fernandez ME, Ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, et al. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:158. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00158

28. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. (2009) 4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

29. Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. (2004) 31:143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660

30. Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJ, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RA, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. (2016) 10:297–312. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155

31. Japan Health Insurance Association. Monthly report of the Japan Health Insurance Association (summary). (2021) (accessed September 15, 2021).

32. Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Labor Force Survey. (2021). (accessed September 15, 2021).

33. Statistics Bureau Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Survey of insured people covered by Health Insurance and Seamen's Insurance (e-stat GL08020103). (2011) (accessed January 10, 2022).

34. Hara M, Matsuoka K, Muto T. Workplace health promotion activities for workers in small-scale enterprises under the auspices of the social insurance health project foundation, Japan. J UOEH. (2002) 24:130–7.

35. Bartholomew-Eldredge LK, Markham MC, Ruiter RA, Fernandez ME, Kok G, Parcel G. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach, 4th edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. (2016).

36. Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. (2012) 7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50

37. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. (2011) 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

38. Kennedy MA, Bayes S, Newton RU, Zissiadis Y, Spry NA, Taaffe DR, et al. We have the program, what now? Development of an implementation plan to bridge the research-practice gap prevalent in exercise oncology. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2020) 17:128. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01032-4

39. Grol R. Changing physicians' competence and performance: Finding the balance between the individual and the organization. J Contin Educ Health Prof. (2002) 22:244–51. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340220409

40. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (Eric) project. Implement Sci. (2015) 10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

41. Hunt MK, Barbeau EM, Lederman R, Stoddard AM, Chetkovich C, Goldman R, et al. Process evaluation results from the healthy directions-small business study. Health Educ Behav. (2007) 34:90–107. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277971

42. Kitayama S, Park J, Miyamoto Y, Date H, Boylan JM, Markus HR. et al. Behavioral adjustment moderates the link between neuroticism and biological health risk: a US-Japan comparison study. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. (2018) 44:809–22. doi: 10.1177/0146167217748603

43. Gelfand MJ, Raver JL, Nishii L, Leslie LM, Lun J, Lim BC, et al. Differences between tight and loose cultures: a 33-nation study. Science. (2011) 332:1100–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1197754

44. Saito J OM, Fujimori M, Saito E, Kuchiba A, Tatemichi M, Fukai K, et al. A feasibility study of interactive assistance via ehealth for small and medium-sized enterprises' employer and health care manager teams on tobacco control: Esmart-Tc. 14th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health. (2021).

Keywords: Implementation Mapping, implementation strategies, workplace, non-communicable diseases, health promotion, implementation science

Citation: Odawara M, Saito J, Yaguchi-Saito A, Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y and Shimazu T (2022) Using implementation mapping to develop strategies for preventing non-communicable diseases in Japanese small- and medium-sized enterprises. Front. Public Health 10:873769. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.873769

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 20 September 2022;

Published: 06 October 2022.

Edited by:

Maria E. Fernandez, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, United StatesReviewed by:

Rinad Beidas, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesRoss Brownson, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Copyright © 2022 Odawara, Saito, Yaguchi-Saito, Fujimori, Uchitomi and Shimazu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Taichi Shimazu, dHNoaW1henVAbmNjLmdvLmpw

Miyuki Odawara

Miyuki Odawara Junko Saito1

Junko Saito1 Taichi Shimazu

Taichi Shimazu