- 1Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Department of Pharmacy, Shahid Behest University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 3Department of Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

- 4Hematologist-Oncologist, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

- 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Birgand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran

- 6Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, School of Medicine, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Bojnurd, Iran

- 7Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 8Department of Complex Genetics and Epidemiology, School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University, Maastricht, Netherlands

Background: Vaccination, one of the most important and effective ways of preventing infectious diseases, has recently been used to control the COVID-19 pandemic. The present meta-analysis study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality from COVID-19.

Methods: A systematic search was performed independently in Scopus, PubMed via Medline, ProQuest, and Google Scholar electronic databases as well as preprint servers using the keywords under study. We used random-effect models and the heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using I2 and χ2 statistics. In addition, the Pooled Vaccine Effectiveness (PVE) obtained from the studies was calculated by converting based on the type of outcome.

Results: A total of 54 studies were included in this meta-analysis. The PVE against SARS-COV 2 infection were 71% [odds ratio (OR) = 0.29, 95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.23–0.36] in the first dose and 87% (OR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.08–0.21) in the second dose. The PVE for preventing hospitalization due to COVID-19 infection was 73% (OR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.18–0.41) in the first dose and 89% (OR = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.07–0.17) in the second dose. With regard to the type of vaccine, mRNA-1273 and combined studies in the first dose and ChAdOx1 and mRNA-1273 in the second dose had the highest effectiveness in preventing infection. Regarding the COVID-19-related mortality, PVE was 68% (HR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.23–0.45) in the first dose and 92% (HR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.02–0.29) in the second dose.

Conclusion: The results of this meta-analysis indicated that vaccination against COVID-19 with BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1, and also their combination, was associated with a favorable effectiveness against SARS-CoV2 incidence rate, hospitalization, and mortality rate in the first and second doses in different populations. We suggest that to prevent the severe form of the disease in the future, and, in particular, in the coming epidemic picks, vaccination could be the best strategy to prevent the severe form of the disease.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, identifier [CRD42021289937].

Introduction

Over the past years, emerging and re-emerging diseases became public health challenges due to their high morbidity and mortality (1). In December 2019, an outbreak of SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was reported in Wuhan, China, and on 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) introduced it as COVID-19 (2–4). More than 250 million cases are diagnosed with COVID-19 infection worldwide of which more than 5 million are dead. As a result of this pandemic, many strategies are implemented by governments around the world to prevent further infections and control the pandemic (5, 6). The rapid spread of infection among individuals, the lack of symptoms or mild presentation of the infection during the incubation period, and the contagious nature of the disease during the incubation period have made the epidemic tremendously difficult to be controlled (7, 8). Hence, in addition to the defined protocols, most prevention programs were also concentrated on using vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, after few vaccines were licensed for emergency use by many countries (9–11).

To illustrate the safety of COVID-19 vaccines for mass vaccination, clinical trials of manufactured vaccines showed that the effectiveness of Oxford-AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1), Pfizer BioNTech (BNT162b2 mRNA), Moderna (mRNA-1273), and Johnson & Johnson (Ad26.COV2.S) vaccines in preventing infection were 70.4, 95, 94.1, and 66.9%, respectively (12–14). However, it should be noted that clinical trials are conducted under highly controlled conditions on voluntary entry of certain individuals and groups (15), which can be significantly different from the general population (16, 17). Several observational studies were designed and conducted to determine the effectiveness of mass vaccination of COVID-19 among various populations and groups to not only specify the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in real situations but also to compare the incidence of infection, mortality, and hospitalization due to COVID-19 in larger samples and with a longer follow-up (18–20).

In the meantime, considering the valuable evidence obtained from the effectiveness of vaccination in different groups, it seemed necessary to summarize the scattered evidence through meta-analysis studies. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the hospitalization and mortality due to COVID-19 after vaccination in observational studies. The findings of the present study will be applicable and valuable for governments, clinicians, public health authorities, and policymakers to design and implement more effective programs for the prevention of COVID-19.

Materials and methods

We designed this systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist (21) and PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) standards (22), under a registered protocol at the international PROSPERO (Registration Number: CRD42021289937).

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Medline, Scopus, ProQuest, and Google Scholar databases as well as the Preprint servers including medRxiv and Research Square to identify the studies related to the keywords selected based on the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) published until 15 October 2021, with full texts in English, without any restrictions. The search was performed blindly and independently by two researchers (K.R. and R.S.) using the following keywords in the abovementioned databases by combining four sets of related MeSH and Non-MeSH terms: (1) COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; coronavirus; (2) vaccine; post-vaccination; (3) mortality; hospitalization; readmission; reinfection; morbidity, and (4) breakthrough infections. Any disagreement in the searches between the two researchers was dealt with by other researchers. Duplicates were also identified by title, author's name, and journal name.

Eligibility criteria

According to the inclusion criteria, observational studies (case-control, negative case-control, case-based cohort, prospective and retrospective cohorts) were published in English that examined the effectiveness, incidence rate of COVID-19, hospitalization rate, and mortality rate after COVID-19 vaccination were suitable to enter into the meta-analysis. Also, the studies that had examined the confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on positive real-time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR or PCR) tests were included, and antibody-based studies and the ones based on other diagnostic methods were excluded from the review process. In addition, case reports, case series, letters or correspondence, animal studies, and studies with mathematical model analysis [Such as the SIR model (Susceptible, Infected and Recovers model)] were also excluded (flowchart 1). The studies on autoimmune, immunosuppressed, dialysis patients, or the patients with kidney problems and mental disorders in whom the severity of the disease varied were excluded as well (23–27). Also, the studies that lacked an unvaccinated group to compare the results with were not included in the review process. Also, studies on inactive vaccines such as CoronaVac and Covaxin as well as Ad26.COV2.S were not included in the analysis due to a lack of enough evidence on these vaccines.

Outcomes

The selected outcomes were as follows:

(1) Effectiveness of the vaccines against infection in the subjects studied (the vaccinated groups compared to the unvaccinated ones), as a relative reduction of RT-PCR test confirmed by throat swab, nasal swab, oropharyngeal swab, or saliva and sputum for COVID-19.

(2) Effectiveness of the vaccines against hospitalization of the subjects in the studies as a relative reduction of hospitalization of the individuals whose RT-PCR test was confirmed by taking throat swab, nasal samples, oropharyngeal swab, or saliva and sputum for COVID-19 disease in the vaccinated groups compared with the unvaccinated ones.

(3) Effectiveness of the vaccines against death of the subjects in the studies as a relative reduction in deaths within 40 days after the RT-PCR test was confirmed by throat swab, nasal swab, oropharyngeal swab, and or saliva and sputum for COVID-19 disease in the vaccinated groups compared with the unvaccinated ones (28).

Data extraction

Two authors extracted the data from the included studies independently. The extracted information contained the author's names, type of vaccine applied, places of study, study design, description of study conditions including study groups, positive SARS-CoV-2 test cases in vaccinated (after the first and second doses) and unvaccinated groups, and cases of death and hospitalization associated with COVID-19 in vaccinated (after the first and second doses) and unvaccinated groups. We also provided a 95% confidence interval for vaccine efficacy for the first and the second doses. Additionally, if the full text of a study was unavailable or if the reported data were missing key information, we contacted the authors by email at least two times, 1 week apart.

The HR of the studies was considered as the risk ratio of the vaccinated to unvaccinated individuals, and in the studies that HR was calculated as the risk ratio of unvaccinated to vaccinated people, it was inversed () and a 95% confidence interval was calculated. Also, in the studies that mentioned the effectiveness percentage through 1-HR × 100%, the HR and 95% of confidence intervals were converted by calculating 1-(). The follow-up periods in the studies were considered based on person-day, even in the studies where the follow-up periods were person-week and person-year.

Considering the studies examined, the people who had not taken any vaccines were classified as unvaccinated, and those who were on the ≥7th day after the first dose and ≥5th day after the second dose were classified as partial vaccinated and fully vaccinated, respectively.

Quality assessment

The quality of the articles was assessed independently by two of the authors (H.F. and M.K.) using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist (29). The included studies were evaluated on three broad criteria: (a) appropriation of the study population selection, (b) comparability of the study groups, and (c) ascertainment of the exposure (for cohort studies) or outcome (for case-control studies) of interest. The scoring range of the checklist was 0 (lowest quality) to 9 (highest quality). In the present research, the studies with a total score of ≥7 were considered high quality (Supplementary Tables 1, 2).

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was carried out using a random-effects model and the Mantel–Haenszel weighting method for each study to estimate pooled Odds Ratios (ORs), pooled Hazard Ratios (HR), and pooled Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR), and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for studies with similar effect measured (OR, IRR, or HR).

The heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using the I2 and χ2 statistics, according to the results of which I2 > 50% with P-value <0.1 showed the heterogeneity of the studies. Also, sub-group analysis was performed on the partial vaccinated and full vaccinated individuals based on the type of vaccine and the study design. In addition, to calculate the pooled vaccine effectiveness (PVE) obtained from the studies, the following conversions were used: 1-Pooled Odds Ratio × 100%, 1-Pooled Hazard Ratio × 100%, and 1-Pooled Rate Ratio × 100%. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified. The statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.1.1 (30) and Metafor Package (31).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to investigate the influence of each individual study or group of studies on the overall risk estimate by removing one study or group of studies at a time. Furthermore, potential publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of Begg funnel plots in which the log RRs were plotted against their standard errors (32).

Results

Study characteristics

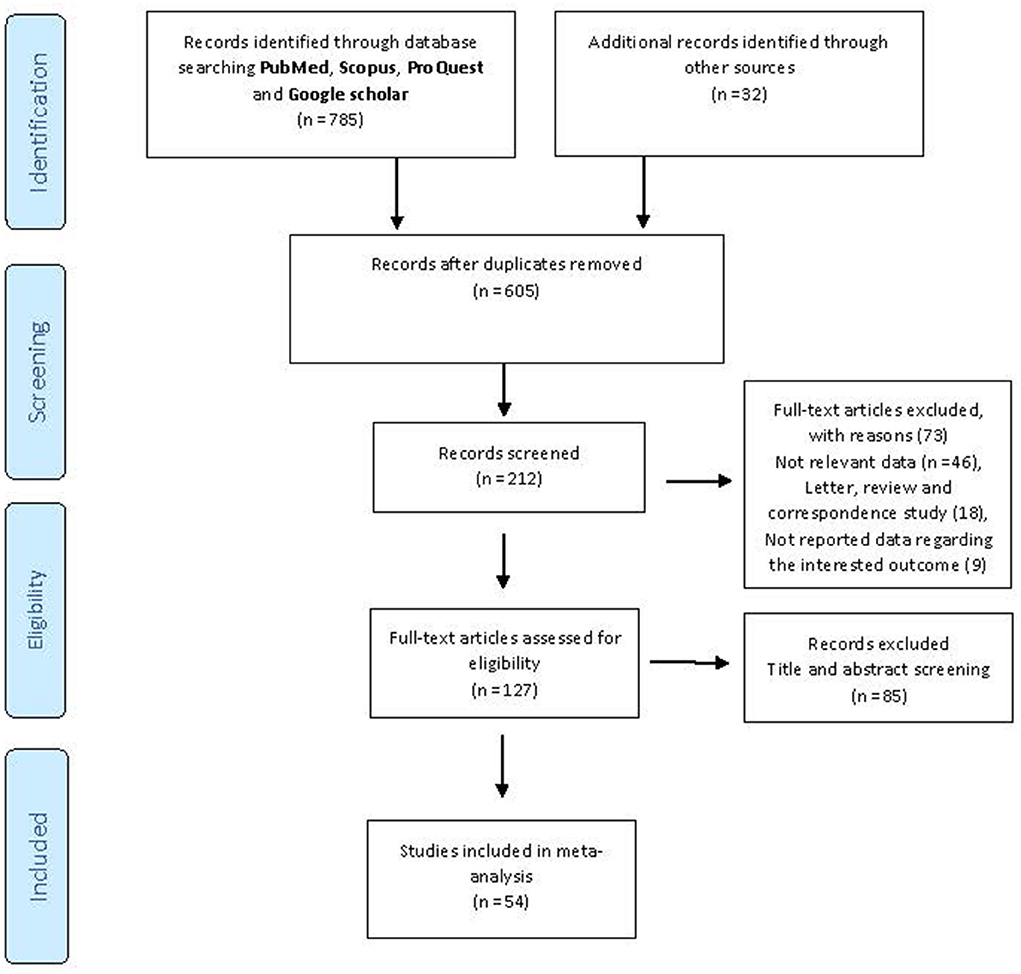

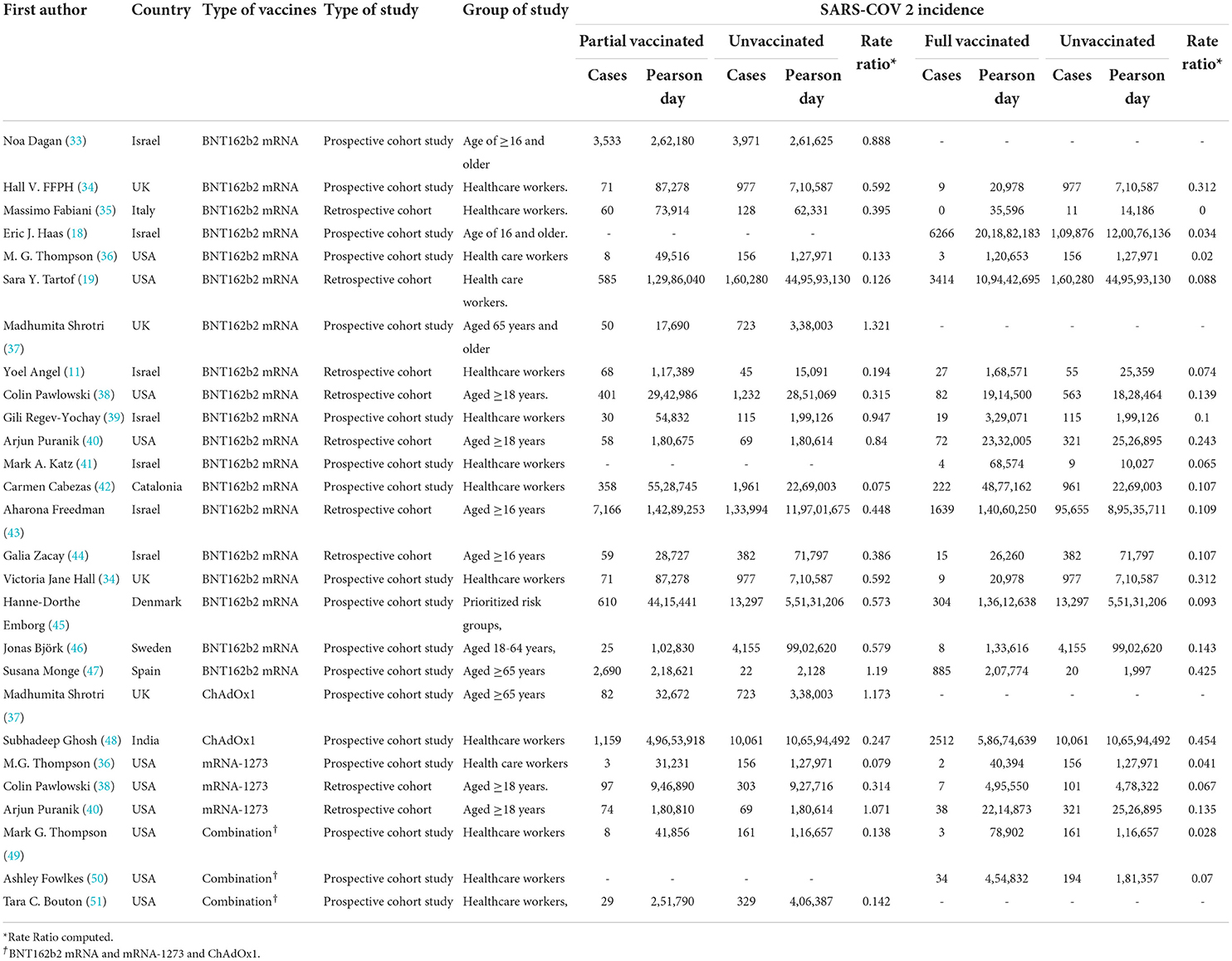

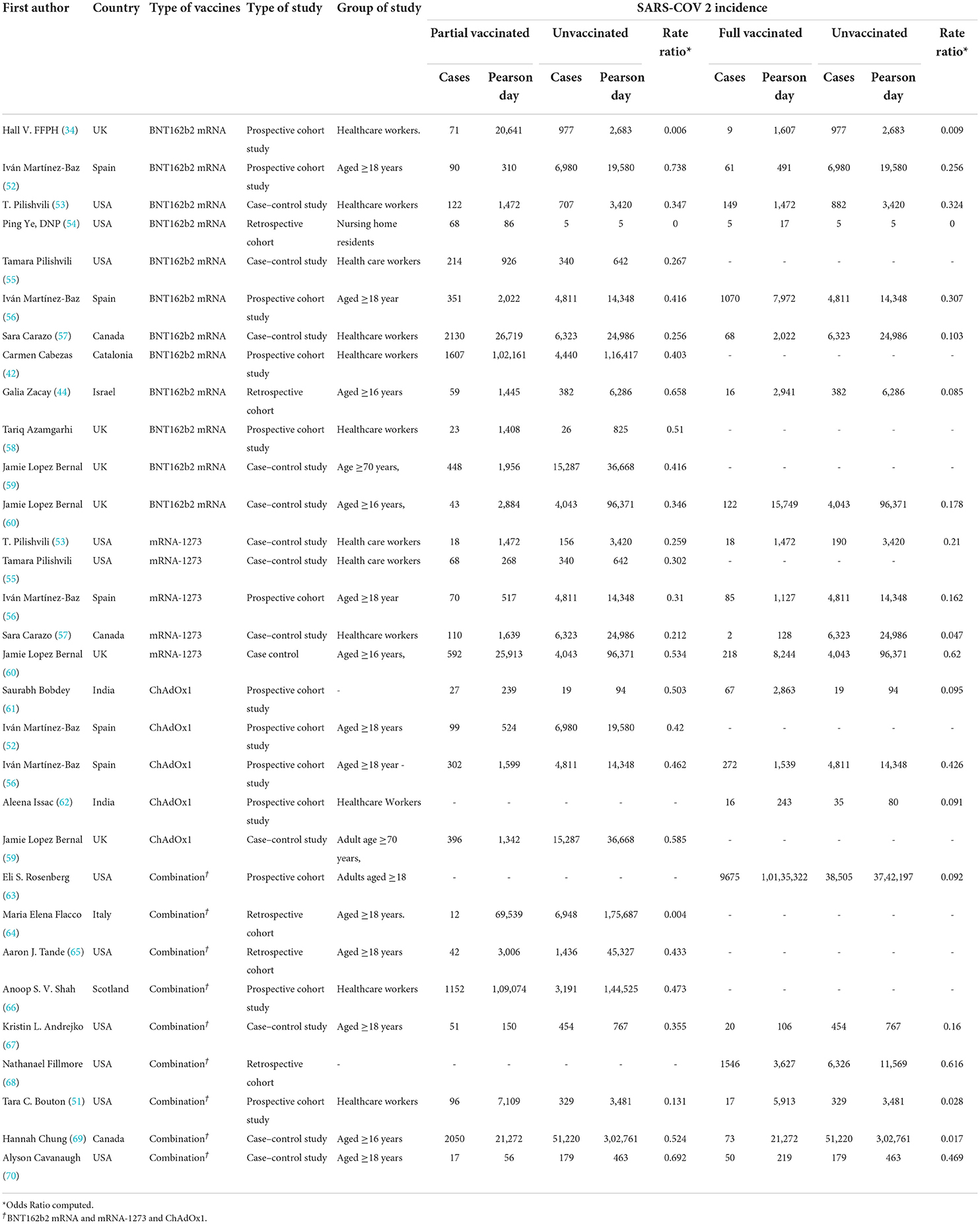

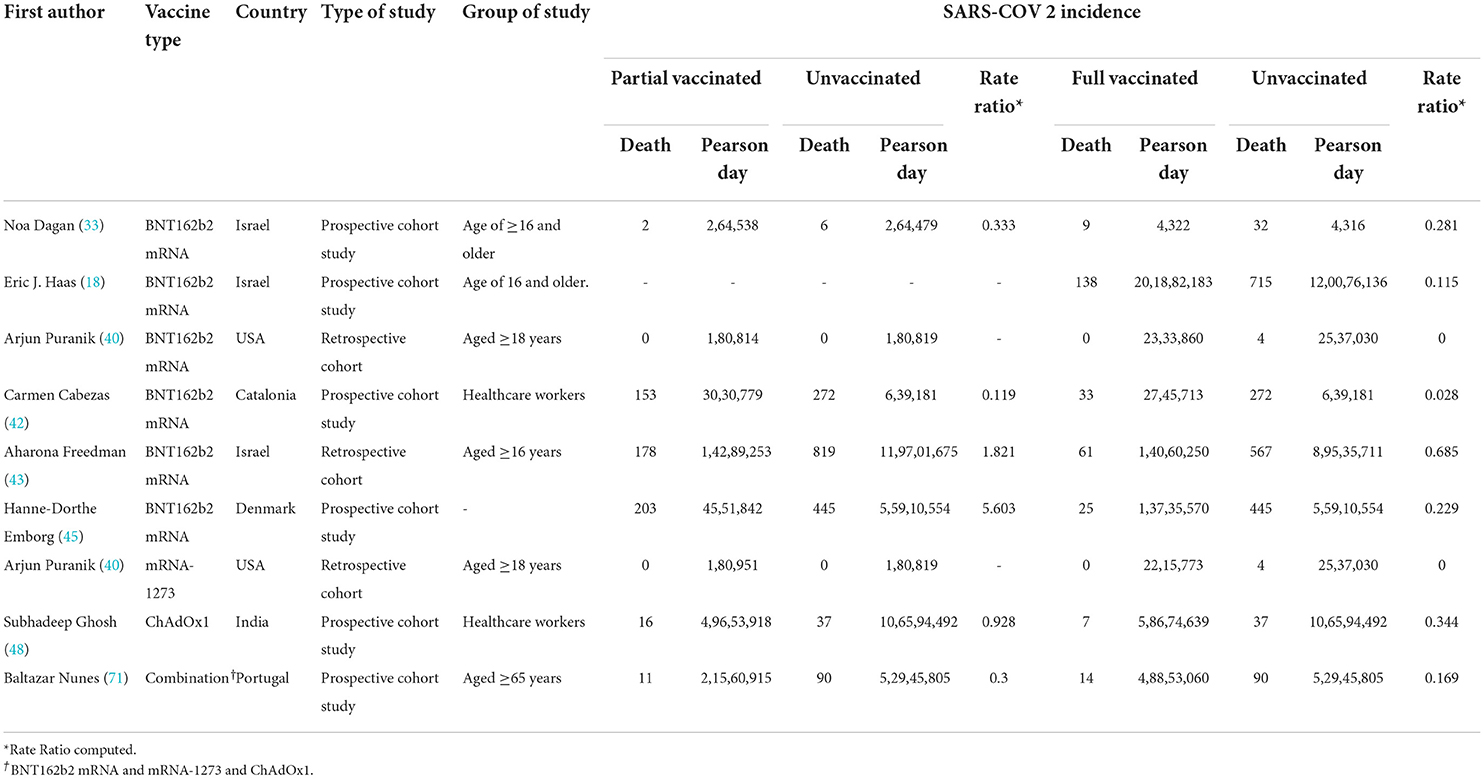

We initially identified 817 potentially relevant articles from the above-mentioned databases, and 212 records were excluded because they were duplicates. Also, after the title and abstract review, 85 articles were further excluded. Reviewing the full text of the remaining articles, 73 were excluded for the reasons presented in Figure 1. Finally, based on the research strategy, 54 records (11, 18–20, 33–81) on the effectiveness, incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, mortality, and hospitalization associated with COVID-19 vaccination were included in the current meta-analysis (the selection procedure is presented in Figure 1). In general, the BNT162b2 mRNA accounted for the most frequent studies on vaccine types (n = 37). In terms of location, most of the studies had been conducted in the USA (n = 20), UK (n = 9), Israel (n = 6), and Spain (n = 3) (Tables 1–5). All of the included studies were carried out on participants older than 14 years.

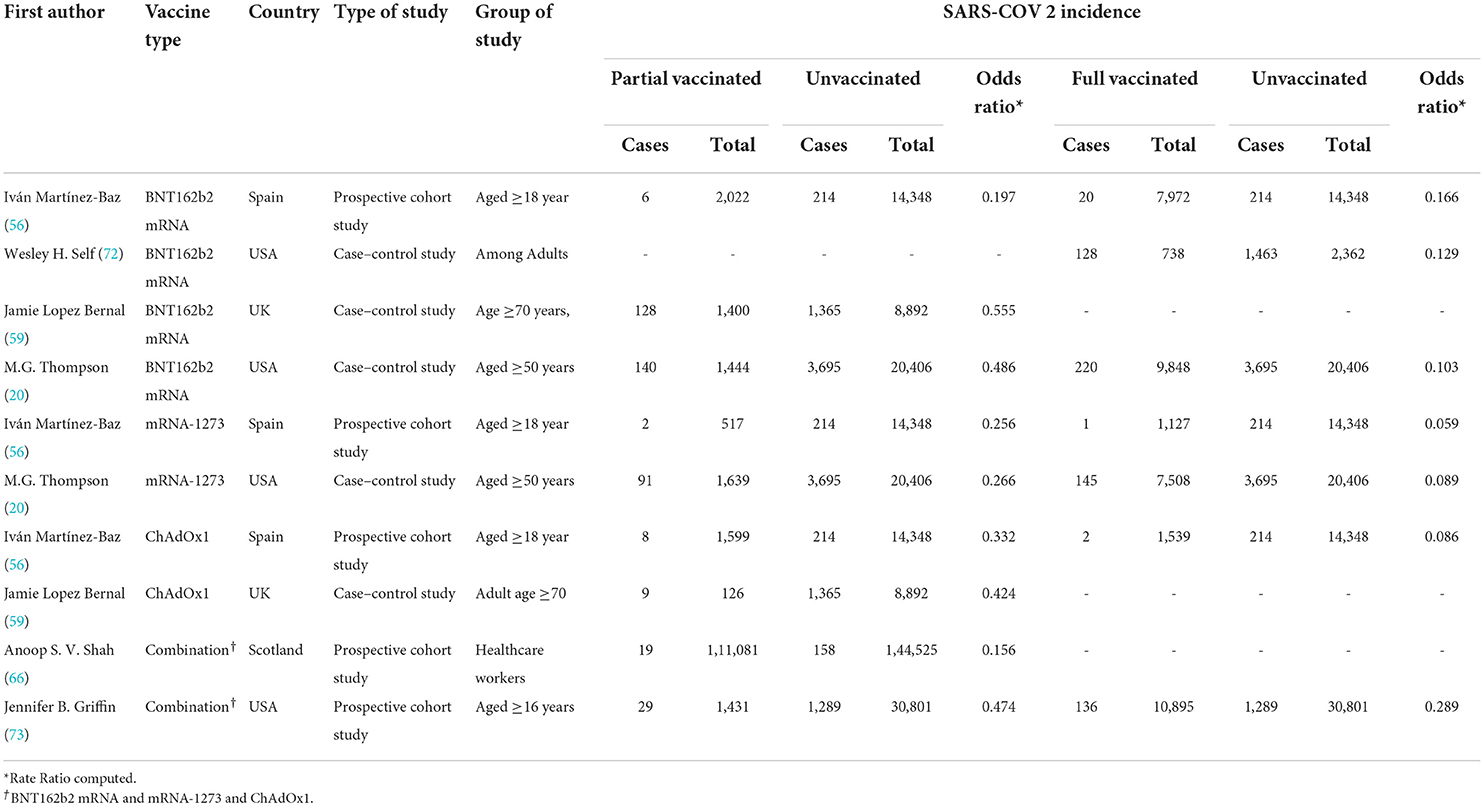

Table 1. Incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection after the first and second doses in people with a history of COVID-19 vaccination.

Table 2. Positive tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection after the first and second doses in people with a history of COVID-19 vaccination.

Table 3. COVID-19-related mortality after the first and second doses in people vaccinated with BNT162b2 mRNA.

Table 4. COVID-19-related hospitalization rate after the first and second doses of vaccinated patients.

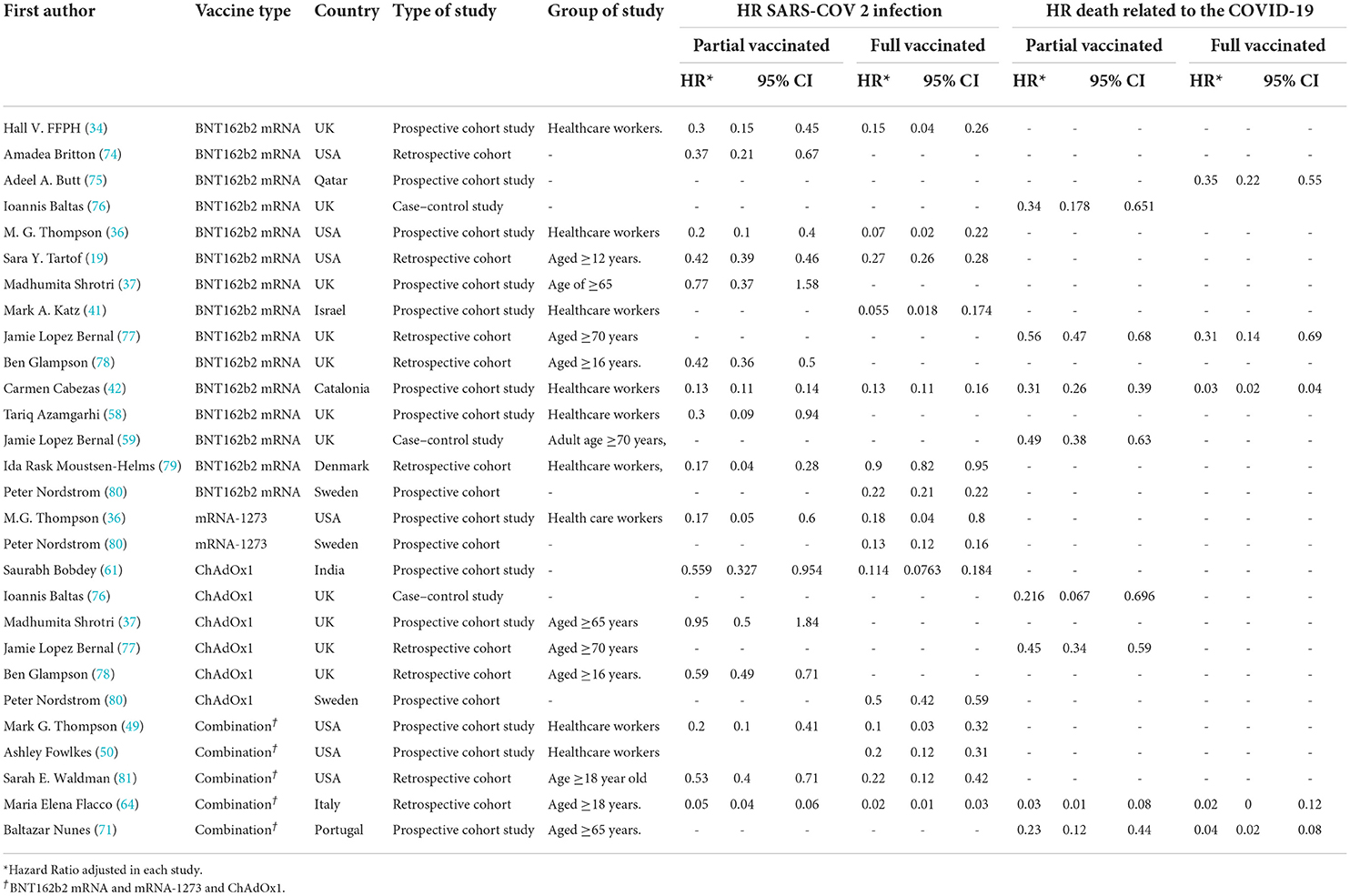

Table 5. Hazard ratio of SARS-COV 2 infection and COVID-19-related mortality in patients with a history of first- and second-dose vaccination.

Results

Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and mortality related to the COVID-19 in partial vaccinated individuals

SARS-CoV-2 infection

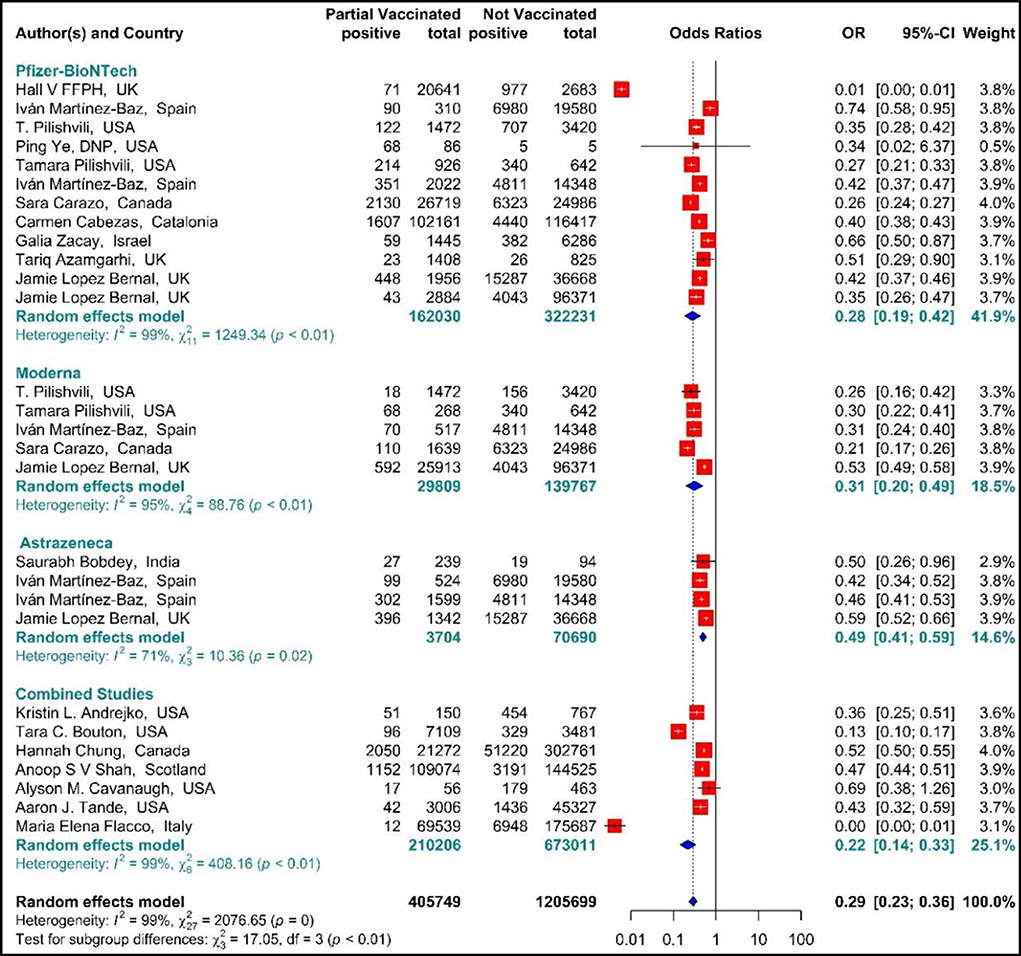

The results of the forest plot using effect measure pooled OR for the included studies (34, 42, 44, 51–61, 64–67, 69, 70) revealed that the effectiveness of the first dose (partial) of the selected vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection was 71% in total (OR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.23–0.36). This effectiveness varied according to the type of vaccine (p−valuesubgroup < 0.01); that is, the effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against SARS-COV 2 infection was 72% (pooled OR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.19–0.42), the effectiveness of mRNA-1273 vaccine was 69% (pooled OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.20–0.49), and that of ChAdOx1 vaccine was 51% (pooled OR = 0.49 95% CI: 0.41–0.59). Furthermore, the combined studies (those who were vaccinated with different types of vaccines) that examined the vaccines (BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1) reported an approximate effectiveness of 78% (pooled OR = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.14–0.33) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using odds ratio in partial vaccinated individuals.

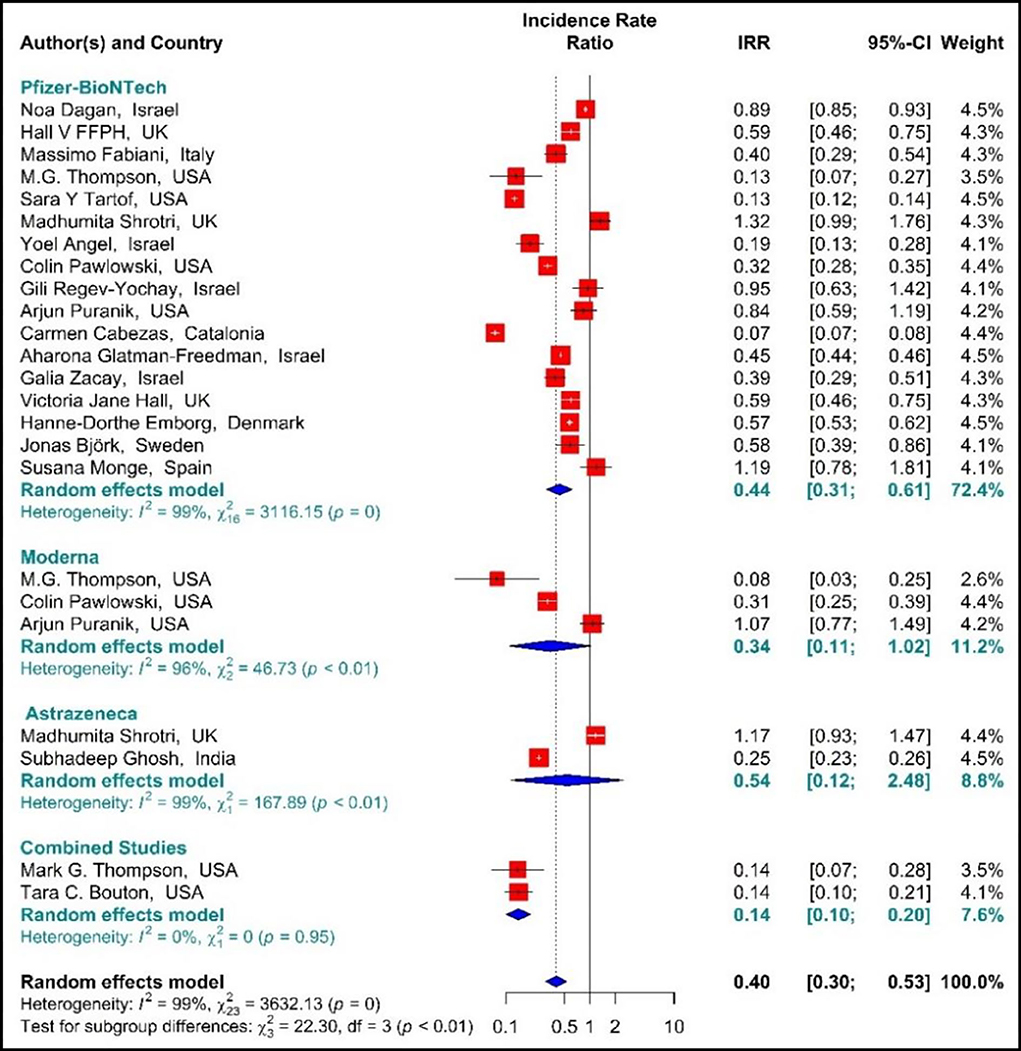

The estimated effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using IRR indicated that the rate of SARS-COV 2 infection in the people vaccinated with BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1, and Combined studies on the first dose was reduced by 60% (IRR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.30–0.53 (Figure 3). The reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection rate in the individuals vaccinated with the first dose of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 was 56% (IRR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.31–0.61), 66% (IRR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.11–1.02), and 46% (IRR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.12–2.48), respectively. In the combined studies, the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection was 86% (IRR = 0.14, 95% CI: 0.10–0.20). The results of the sub-group analysis in the first dose showed well that there was a significant difference between the effectiveness of different types of vaccines against SARS-COV 2 infection (p−valuesubgroup < 0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using incidence rate ratio (IRR) in partial vaccinated individuals.

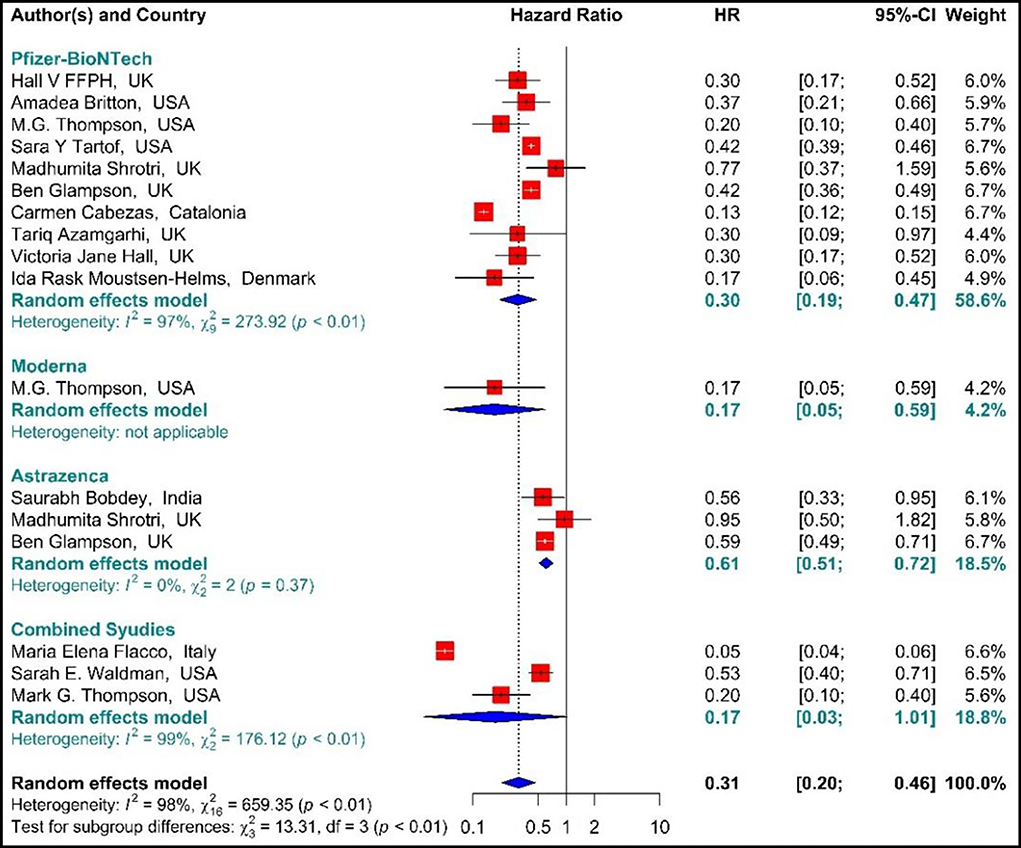

Studying the Hazard ratio associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection showed that vaccination with the first dose of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1, and Combined studies reduced the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection by 69% (HR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.20–0.46) (Figure 3) (19, 34, 36, 37, 42, 49, 58, 61, 64, 74, 78, 79, 81). In other words, the first doses of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines had reduced the SARS-CoV-2 infection by 70% (HR = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.19–0.47), 83% (HR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.05–0.59), and 39% (HR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.51–0.72), respectively. On the other hand, the combined studies had reduced the risk of SARS-COV 2 infection by 83% (HR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.03–1.01). The results of the sub-group analysis on those who received the first dose suggested that there was a difference between the effectiveness of different types of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection (p−valuesubgroup < 0.01) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using hazard ratio in partial vaccinated individuals.

Hospitalization

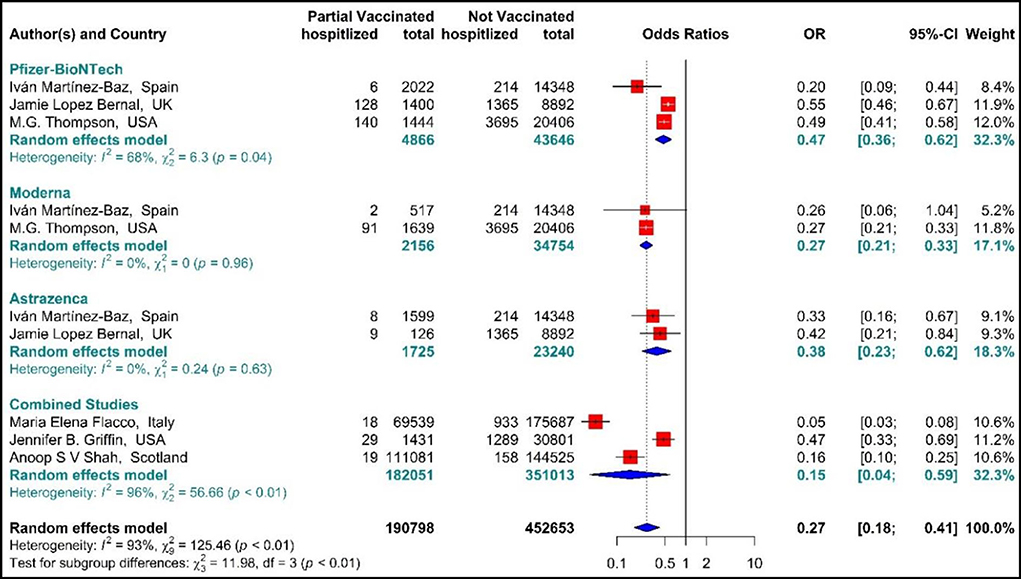

The total effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines as well as the combined studies in the first dose against COVID-19-related hospitalization was 73% (OR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.18–0.41) (Figure 5) (20, 56, 59, 64, 66, 73). Considering the type of vaccines, the results of pooled analysis showed that the effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was 53% (OR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.36–0.62), that of mRNA-1273 was 73% (OR = 0.27, 95% CI: 0.21–0.33), and the effectiveness of ChAdOx1 vaccine was about 62% (OR = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.23–0.62). In the Combined studies, the pooled efficacy of the vaccines was about 85% (OR = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.04–0.59). The results of the sub-group analysis on the type of vaccines indicated no significant difference between the effectiveness of the vaccines in the first dose against hospitalization with COVID-19 (p−valuesubgroup < 0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19-related hospitalization in partial vaccinated individuals.

Mortality

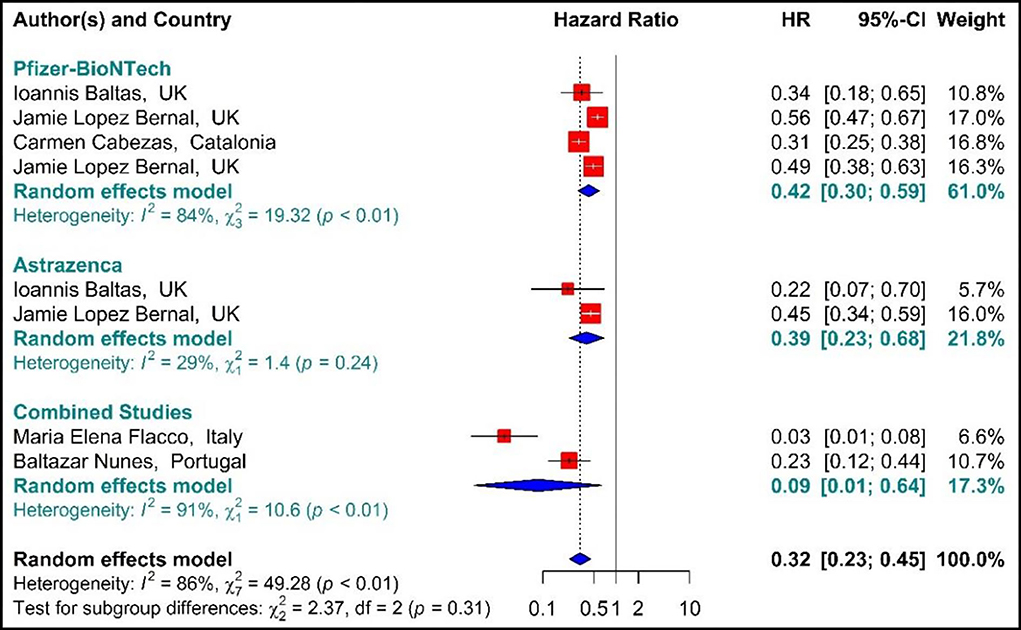

As presented in Figure 6, the COVID-19-associated mortality Hazard ratio in the first-dose vaccinated individuals (42, 59, 64, 71, 76, 77) suggested that the first-dose vaccination with BNT162b2 mRNA, ChAdOx1, and Combined studies had reduced the COVID-19-related mortality rate by 68% (HR = 0.32, 95% CI: 0.23–0.45). However, people who were vaccinated with the first dose of BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 showed 58% (HR = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.30–0.59) and 61% (HR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.23–0.68) reduction in the mortality risk. Besides, the combined studies reduced the risk of COVID-19-related mortality by 91% (HR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.01–0.64). The results of sub-group analysis for the first dose suggested that there was no difference between the effectiveness of different types of vaccines against COVID-19-related mortality rates (p−valuesubgroup = 0.31) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19-related mortality using hazard ratio in partial vaccinated individuals.

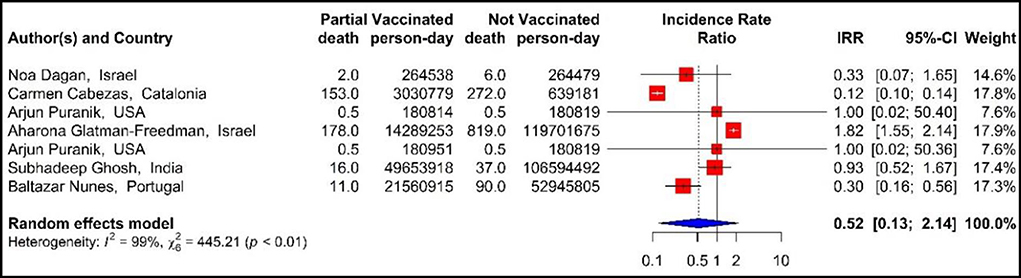

The results of examining the effectiveness of the first dose of vaccines against COVID-19-related mortality using IRR (33, 40, 42, 43, 48, 71), showed that the mortality rate in the people vaccinated with the first dose of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1, and combined studies were reduced by 48% (IRR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.13–2.14) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19-related mortality using incidence rate ratio in partial vaccinated individuals.

Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and mortality related to the COVID-19 in fully vaccinated individuals

SARS-CoV-2 infection

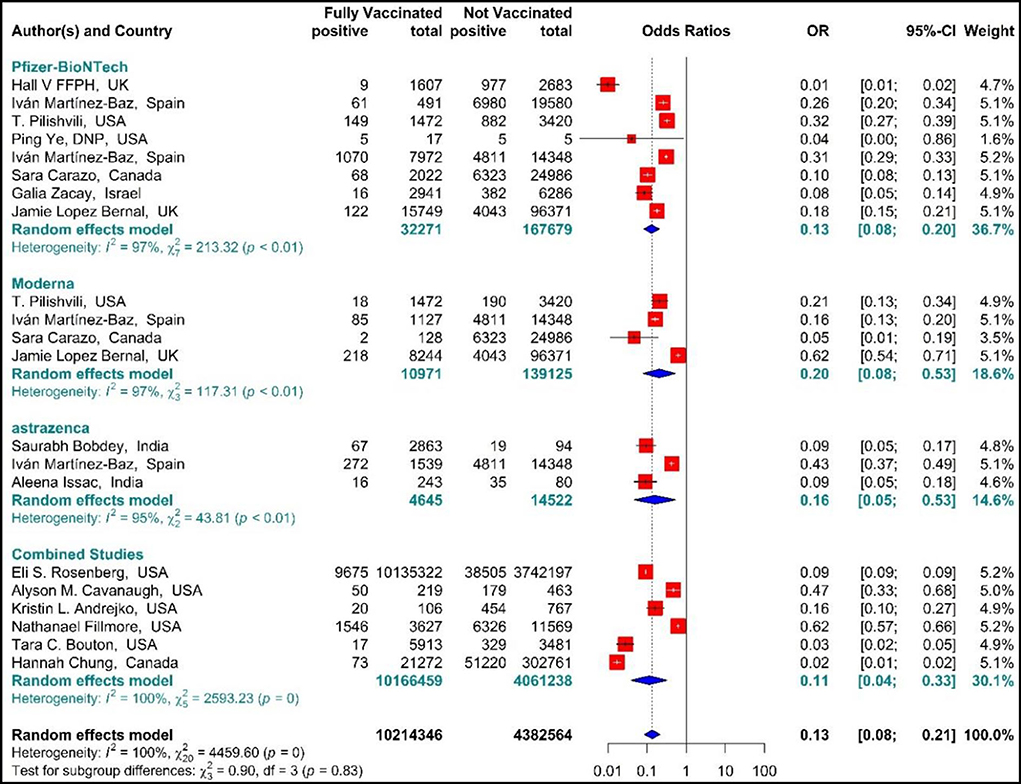

The results of studies (34, 44, 51–54, 56, 57, 60–63, 67–70) are presented as forest plots using effect measure pooled OR in Figure 8. The results showed that the total effectiveness of the second dose of the vaccines (Fully vaccinated) against COVID-19 infection was 87% (OR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.08–0.21); that is, the effectiveness of the second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 infection was 87% (OR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.08–0.20), that of mRNA vaccine-1273 was 80% (OR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.08–0.53), and the effectiveness of the second dose of ChAdOx1 vaccine was 84% (OR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.05–0.53). In addition, the combined studies that examined BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines reported an approximate effectiveness of 89% for the second doses (OR = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.04–0.33). The results of the sub-group analysis in the second dose suggested that there was no significant difference between different types of vaccines in terms of their effectiveness (p−valuesubgroup = 0.83) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using odds ratio in Full vaccinated individuals.

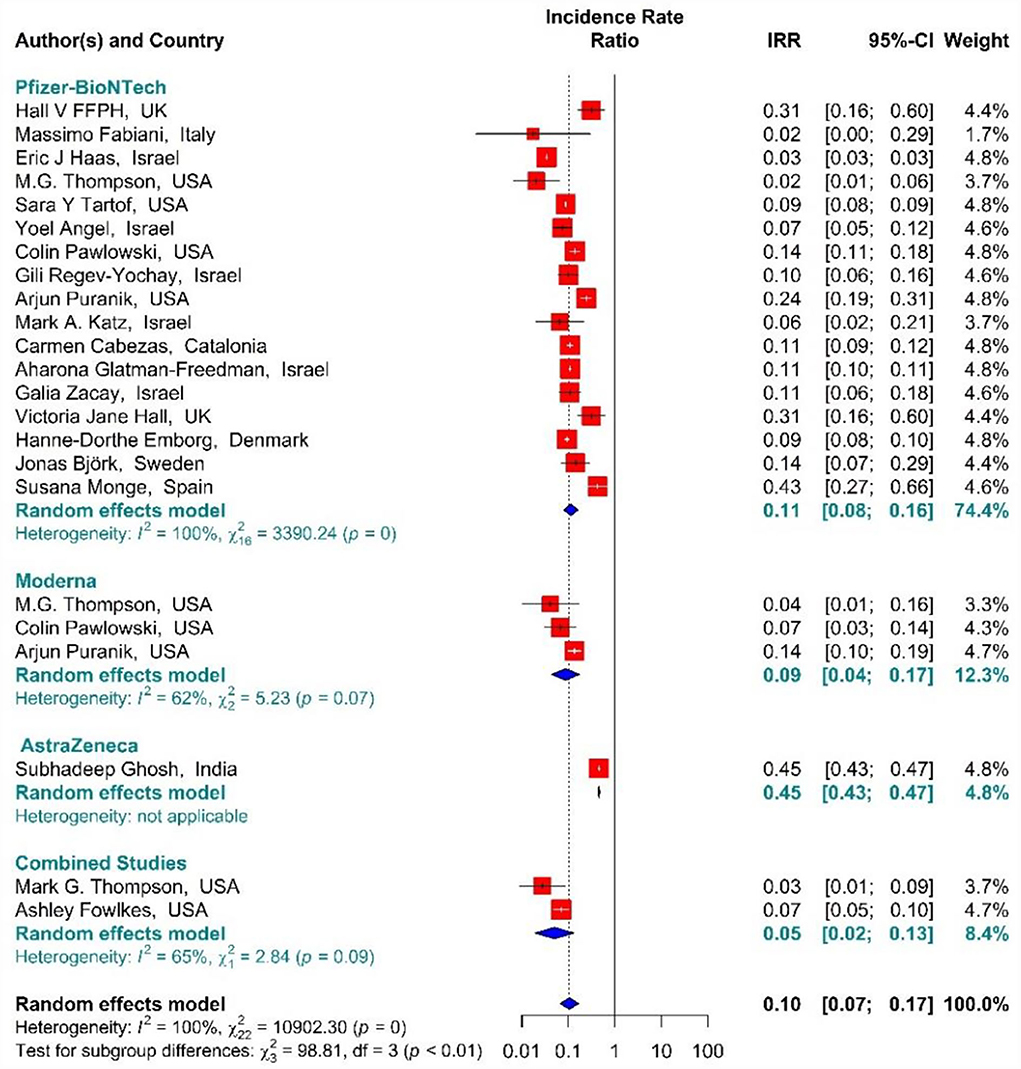

In the people vaccinated with the second dose (fully vaccinated) of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, ChAdOx1, and combined studies, the rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection using IRR were reduced by 90% (IRR = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.07–0.17) (Figure 9) (11, 18, 19, 34, 35, 38, 39, 42–50, 80, 82). The reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection rate in the individuals vaccinated with the second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 was 89% (IRR = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.08–0.16), 91% (IRR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.04–0.17), and 55% (IRR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.43–0.47), respectively (Figure 9). In the combined studies, the SARS-CoV-2 infection rate after the second dose had reduced by 95% (IRR = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.02–0.13). The results of the sub-group analysis in the second dose suggested that there was a difference between the effectiveness of different types of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection (p−valuesubgroup < 0.01) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using incidence rate ratio in full vaccinated individuals.

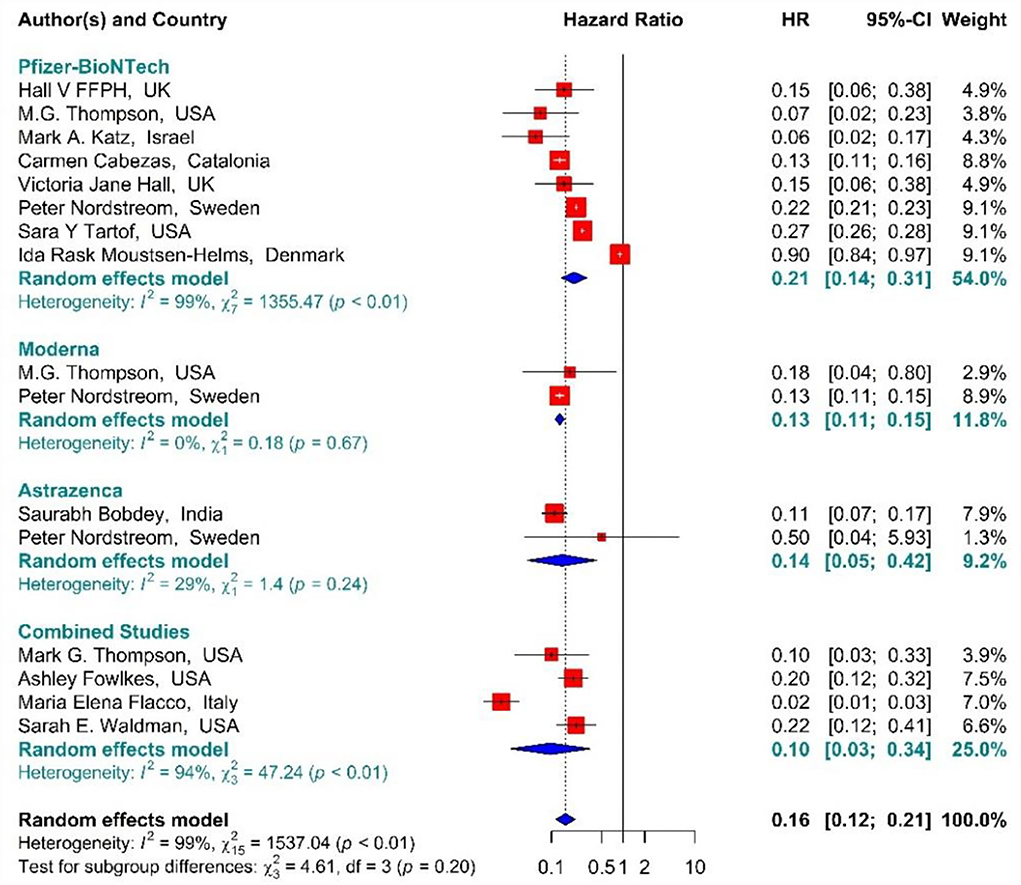

In the individuals vaccinated with the second dose (Full vaccinated) of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines, as well as the combined studies, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection using Hazard Ratio was reduced by 84% (HR = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.12–0.21) (Figure 10) (19, 34, 36, 41, 42, 49, 50, 61, 64, 79–81). However, the second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines reduced the risk of infection by 79% (HR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.14–0.31), 87% (HR = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.11–0.15), and 86% (HR = 0.14, 95% CI: 0.05–0.42) respectively. Furthermore, the combined studies suggested that vaccination reduced the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the individuals vaccinated with a second dose by 90% (HR = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.03–0.34). The results of the sub-group analysis in the second dose suggested that there was no difference between the effectiveness of different types of vaccines (p−valuesubgroup = 0.2) (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection using hazard ratio in full vaccinated individuals.

Hospitalization

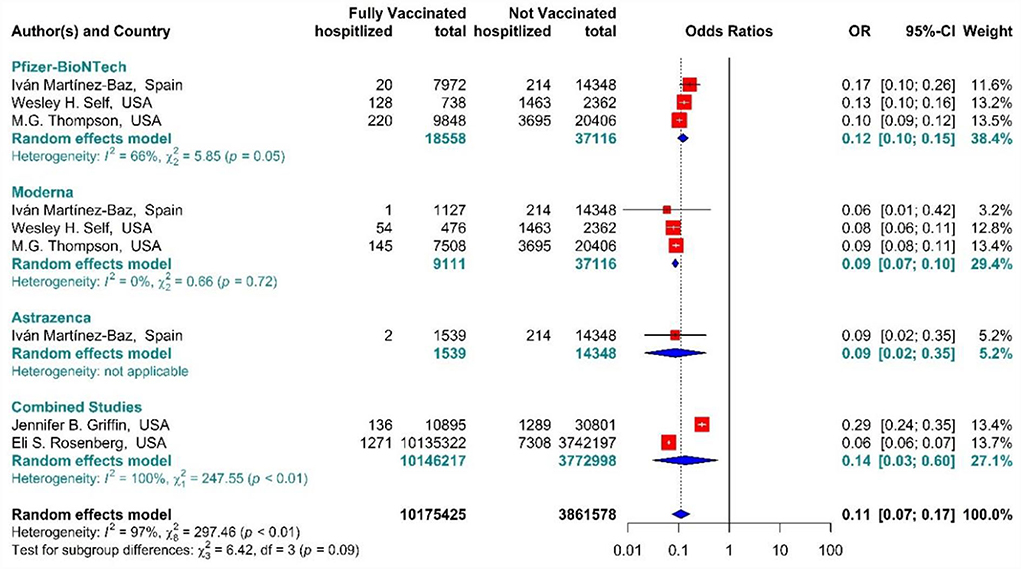

The total effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines, as well as the combined studies, for the second dose against COVID-19-related hospitalization was 89% (OR = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.07–0.17), while BNT162b2 mRNA, MRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines had the effectiveness of 88% (OR = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.10–0.15), 91% (OR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.07–0.10), and 91% (OR = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.02–0.35), respectively (Figure 11) (20, 56, 63, 72, 73). In addition, the effectiveness of the vaccines in the combined studies was 86% (OR = 0.14, 95% CI: 0.03–0.60). The results of the sub-group analysis in the second dose suggested that there was no significant difference between the effectiveness of different types of vaccines against hospitalization (p−valuesubgroup = 0.09).

Figure 11. Effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19-related hospitalization in full vaccinated individuals.

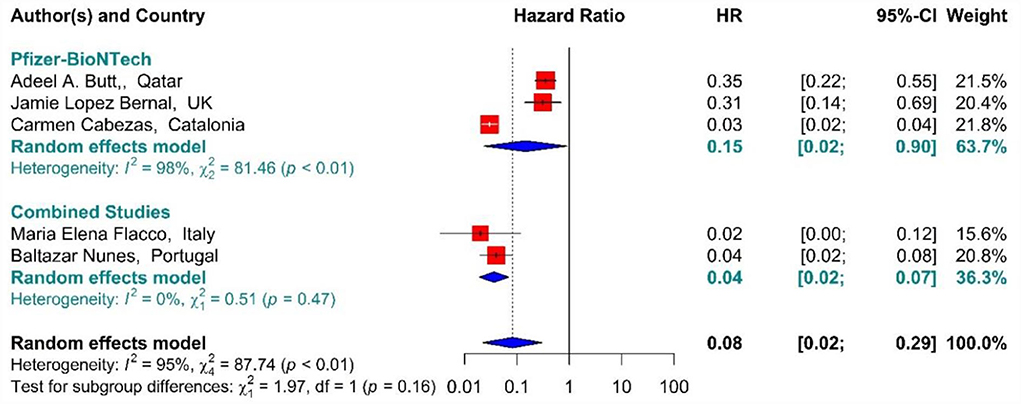

Mortality

In the individuals fully vaccinated with BNT162b2 mRNA as well as combined studies, the COVID-19-associated mortality risk using Hazard Ratio was reduced by 92% (HR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.02–0.29) (Figure 12) (42, 64, 71, 75, 77). However, BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and the combined studies reduced the risk by 85% (HR = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.02–0.90) and 96% (HR = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.02–0.07), respectively. The results of the sub-group analysis in the second dose showed that there was no difference between the effectiveness of different vaccines against COVID-19-related death (p−valuesubgroup = 0.16) (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19-related mortality using hazard ratio in full vaccinated individuals.

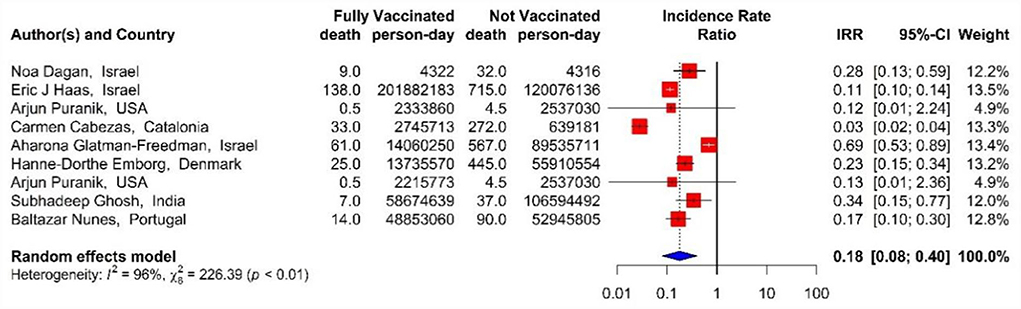

In addition, the effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines, as well as the combined studies, against COVID-19-related mortality using IRR in the second dose was 82% (IRR = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.08–0.40) (Figure 13) (18, 33, 40, 42, 43, 45, 48, 71).

Figure 13. Effectiveness of vaccines against COVID-19-related mortality using incidence rate ratio in full vaccinated individuals.

Sub-group analysis by study design

The results of the sub-group analysis with regard to the type of studies suggested that there was no statistically significant difference between case-control studies, prospective studies, and retrospective studies in terms of the effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization rate, and mortality associated with COVID-19 (Supplementary File 1 in Figures 1–12).

Quality assessment, sensitivity analysis, and publication bias

Supplementary File 1 in Tables 1, 2 shows the quality of the included articles according to NOS (due to limited space and word counting, the results of the NOS tool are provided as Supplementary File 2). The results of the sensitivity analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the studies included in the meta-analysis (Supplementary File 2 in Figures 1–12). In addition, publication bias in the studies included in the meta-analysis was investigated through Funnel Plot and Eggers' test, the results of which showed no publication bias in the studies included in the meta-analysis (Eggers' test P-value > 0.05) (Supplementary File 2 in Figures 13–15).

Discussion

In the present meta-analysis of the observational studies, we aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of vaccination in reducing the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection as well as mortality and hospitalization.

Although some systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCT studies have been conducted in the field of vaccination and COVID-19, none of them has wholly and comprehensively investigated the effective role of vaccination for COVID-19 on the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality of patients. On the other hand, focusing on the influential role of injectable doses of vaccine in observational studies was fully investigated in this meta-analysis, which was not comprehensively examined in the previous studies.

The results supported the findings of phase 3 of the clinical trials on the effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 vaccines (12, 83, 84). More precisely, previously, the effectiveness of the first and second doses of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection was reported to be 82% and 95%, respectively (12), and we found that the pooled estimates of the effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 were 72 and 89%, respectively. Also, the effectiveness of ChAdOx1 and mRNA-1273 vaccines against the incidence of infection was estimated at about 51 and 69% in the first dose and 84% and 80% in the second dose, respectively. These results are consistent with the previous studies (33, 83, 84).

Notably, the observed difference in the effectiveness of the first and the second doses could be due to the fact that those corona vaccines that were designed as two-dose regimens are suggested to be injected at regular intervals to achieve the highest immunity. Several studies suggested that receiving only one dose of the vaccine creates a partial immunity response and might provide a shorter period of immunity than receiving full doses (18, 34, 78, 85, 86).

As such, the pooled increased effectiveness of the studied vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection after the second dose was 16% (from 71% in the first dose to 87% after the second dose). The increased effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in the second dose compared to the first one was 15%, and that of mRNA-1273 and ChAdOx1 vaccines was 11% and 33%, respectively. Also, the difference between the effectiveness of the two doses of vaccines against the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the studies that examined the vaccines heterogeneously (a combination of COVID-19 vaccines on the general population) was 11%.

Interestingly, especially after the second dose, the effectiveness of the vaccines increased significantly with the increased post-vaccination follow-up periods. Accordingly, Hunter and Brainard (87) reported relatively high effectiveness of the first dose of BNT162b2 mRNA 21 days after the second injection. The Hunter's study results indicated that high effectiveness of the second dose of COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality was achieved between 20 and 30 days after the first dose.

Although the present study aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of homologous vaccines, there were some studies that examined the effectiveness of different combinations of vaccines in different populations. For example, few studies evaluated the immunity of populations that were vaccinated with BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 (and even Ad26.COV2.S in some rare cases), the results of which showed significant improvement in the effectiveness of the vaccines. In a study of combined vaccines, Nordstrom et al. (80) showed that vaccines' effectiveness varied from 67 to 79% depending on the types administered. The results of our meta-analysis on the effectiveness of combined vaccines were also consistent with the study by Nordstrom et al. and strengthened the hypothesis of the better effect of combined vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Considering different variants of COVID-19, although the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against alpha and delta variants is reported to be lower, the effectiveness of full vaccination against these variants has been revealed to be acceptably high (60). In an observational study, Haas et al. (18) reported the high effectiveness of two doses of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against the B.1.1.7 variant of SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and mortality. However, another study on the effects of COVID-19 vaccines on delta variants did not observe a significant effect 28 days after the first dose (88). Our meta-analysis also suggested that the effect of complete vaccination on the reduction of the incidence of infection, hospitalization, and mortality is high regardless of SARS-CoV-2 variants (88). Moreover, the effectiveness of complete COVID-19 vaccination in reducing the rate of hospitalization in our study confirmed the results of the previous studies on the prevention of COVID-19-related hospitalization (18, 20, 59). The biggest difference in the effectiveness of the two vaccine doses against hospitalization was related to BNT162b2 mRNA and mRNA-1273 with 35 and 29% increase, respectively, in the effectiveness of vaccines after the second doses. Also, administering the second dose injection was associated with 21% decrease in the risk of COVID-19 mortality compared to the first dose (68% in the first vs. 89% in the second doses).

It is suggested that the effectiveness of vaccines in the community is an ecological issue, and separating it from non-medical measures such as quarantine and wearing masks is difficult. However, various studies reported high levels of vaccine effectiveness even after the reopening of communities (18). The other concern in evaluating the study's results is the test policies for vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, which vary from community to community. For example, in Israel, SARS-CoV-2 testing policy was different for unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals; the vaccinated individuals must provide evidence of being in contact with PCR-positive persons or returning from abroad (33). This may lead to an overestimation of vaccine effectiveness. Moreover, vaccinated and unvaccinated people have different behaviors in seeking healthcare and taking diagnostic tests for COVID-19, which can, in turn, affect the effectiveness of the vaccine. People who have refused to be vaccinated are also less likely to take a diagnostic test, which can lead to underestimated vaccine effectiveness. Other reasons that can affect the validity of the results is different follow-up times in various studies, the interval between the first and the second doses of vaccines, and the fact that the persons may delay taking the second dose of vaccine deliberately or due to a lack of logistic and technical preparations. This can in turn affect the vaccine's effectiveness (18, 89).

Although the differences were not significant, the results of the present study showed that the effectiveness of the vaccines varies in different studies. For example, several prospective cohort studies showed higher effectiveness compared to retrospective cohorts, and they both showed higher effectiveness than case-control studies. Although, it has been suggested that the best studies to evaluate the effectiveness of vaccines are randomized clinical trials, because they strongly differentiate the protective effect of vaccines at the individual level (90), non-randomized studies played a major role in estimating the effectiveness of vaccines during the pandemic. For example, a Scottish retrospective cohort study provided promising findings on the effectiveness of the first doses of Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines in Scotland (86). A considerable reason for the importance of non-randomized studies is that different variants cannot be randomly divided into different groups and thus, non-randomized studies are a good alternative to clinical trials to estimate the effectiveness of vaccines against new variants. In addition, negative test studies are considered as one of the most appropriate types of studies that properly reduce the disruptive effect of health seeking behavior in the compared groups (91), as a recent negative test study in Canada provided evidence of the effectiveness of Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines against alpha, beta, gamma, and delta variants (92).

This study has some strengths and limitations to be noted. Among the strengths of the present study is that we examined all aspects of the effectiveness of vaccination against the incidence of COVID-19, including SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalization, and mortality from COVID-19. Since the quality of meta-analyses is largely reliant on the quality of the original studies included, in our study, we included high-quality studies from different parts of the world with relatively large sample sizes and cohort studies with appropriate follow-ups resulting in increasing the validity of the results. The presence of studies from different regions may influence the generalizability of our study results. Notably, the important procedures such as searching studies, data extraction, and quality assessment were independently performed and reviewed by two experts in the field of secondary studies. Despite the significance of our findings about the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the incidence of infection, hospitalization, and mortality associated with COVID-19, this study had a number of limitations, including the effects of different vaccines on different variants, the possibility of vaccination in a specific age group, or vaccine hesitancy, which refers to the delay in accepting or refusing available vaccination, which indicated that non-vaccinated people had a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and we had no access to such data. The confounding of the background factors may, however, have a limited influence on our results when using HR adjusted in the included trials. Another disadvantage is that the less investigated COVID-19 vaccines did not have the chance to be assessed and hence were not included in our analysis. As a result, further research is needed to validate the efficacy of vaccinations that have received less attention.

Conclusion

The results of this meta-analysis indicated that vaccination against COVID-19 with BNT162b2 mRNA, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1, and also their combination, was associated with a favorable effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 incidence rate, hospitalization, and mortality rate in the first and second doses in different populations. On the other hand, due to the higher effectiveness of the second dose of vaccines, compared to the first dose, in reducing the incidence rate of infection, mortality rate, and hospitalization associated with COVID-19, we suggest that to prevent the severe form of the disease in the future, and, in particular, in the coming epidemic picks, vaccination could be compulsory for high-risk individuals. We, also, strongly suggest more research on the durability of immunity after booster vaccines and the effect of booster doses on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines on the incidence rate, mortality rate, and hospitalization rate of the disease. Also, more research on the effectiveness of booster doses with different vaccines on the new variants is highly recommended. Likewise, our results would apply to health policymakers and stakeholders to encourage people to accept the effects of vaccines and minimize vaccine hesitancy in the prevention of severe forms of the disease.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

KR, RS, and MD contributed to the design and implementation of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data, and were involved in drafting the manuscript. HD and MK contributed to the assessing quality of studies. MFor and RO contributed to the interpretation of data and were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. MS and MR contribute to the data extractions and data management. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.873596/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Morens DM, Folkers GK, Fauci AS. The challenge of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Nature. (2004) 430:242–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02759

2. Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, Chen C, Chen J, Mei W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 21:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331

3. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. (2020) 395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

4. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. (2020) 395:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7

5. Organization WH. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Geneva: World Health Organization (2020).

6. Sharma O, Sultan AA, Ding H, Triggle CR. A review of the progress and challenges of developing a vaccine for COVID-19. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:2413. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.585354

7. Covid CD, Team R, COVID C, Team R, Bialek S, Boundy E et al. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:343. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2

8. Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, Ahn D, Sen AI, Fischer A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children's hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr. (2020) 174:e202430–e202430. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430

9. Forni G, Mantovani A. COVID-19 vaccines: where we stand and challenges ahead. Cell Death Differ. (2021) 28:626–39. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00720-9

10. Verbeke R, Lentacker I, De Smedt SC, Dewitte H. The dawn of mRNA vaccines: The COVID-19 case. J Control Release. (2021) 333:511–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.03.043

11. Angel Y, Spitzer A, Henig O, Saiag E, Sprecher E, Padova H et al. Association between vaccination with BNT162b2 and incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among health care workers. JAMA. (2021) 325:2457–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7152

12. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2603–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

13. Voysey M, Clemens SA, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. (2021) 397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1

14. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, Cárdenas V, Shukarev G, Grinsztejn B, et al. Safety and efficacy of single-dose Ad26.COV2 S vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:2187–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101544

15. Helfand BK, Webb M, Gartaganis SL, Fuller L, Kwon C-S, Inouye SK. The exclusion of older persons from vaccine and treatment trials for coronavirus disease 2019—missing the target. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:1546–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5084

16. Welch MJ, Lally R, Miller JE, Pittman S, Brodsky L, Caplan AL, et al. The ethics and regulatory landscape of including vulnerable populations in pragmatic clinical trials. Clin Trial. (2015) 12:503–10. doi: 10.1177/1740774515597701

17. Cooper DM, Afghani B, Byington CL, Cunningham CK, Golub S, Lu KD, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine testing and trials in the pediatric population: biologic, ethical, research, and implementation challenges. Pediatr Res. (2021) 90:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41390-021-01402-z

18. Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, Anis E, Singer SR, Khan F, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. (2021) 397:1819–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8

19. Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, Hong V, Ackerson BK, Ranasinghe ON, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. (2021) 398:1407–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02183-8

20. Thompson MG, Stenehjem E, Grannis S, Ball SW, Naleway AL, Ong TC, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in ambulatory and inpatient care settings. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1355–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110362

21. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Jama. (2000) 283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008

22. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. (2009) 62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

23. Henry BM, Lippi G. Chronic kidney disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Int Urol Nephrol. (2020) 52:1193–4. doi: 10.1007/s11255-020-02451-9

24. Li L, Li F, Fortunati F, Krystal JH. Association of a prior psychiatric diagnosis with mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2023282. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23282

25. Warren N, Kisely S, Siskind D. Maximizing the uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine in people with severe mental illness: a public health priority. JAMA psychiatry. (2021) 78:589–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4396

26. Gao Y, Chen Y, Liu M, Shi S, Tian J. Impacts of immunosuppression and immunodeficiency on COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. (2020) 81:e93. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.017

27. Gisby J, Clarke CL, Medjeral-Thomas N, Malik TH, Papadaki A, Mortimer PM, et al. Longitudinal proteomic profiling of dialysis patients with COVID-19 reveals markers of severity and predictors of death. Elife. (2021) 10:e64827. doi: 10.7554/eLife.64827

28. Weinberg GA, Szilagyi PG. Vaccine epidemiology: efficacy, effectiveness, and the translational research roadmap. J Infect Dis. (2010) 201:1607–10. doi: 10.1086/652404

29. Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (2011). p.1–12.

30. Team, RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online at: http://www.R-projectorg/2013

31. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. (2010) 36:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03

32. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

33. Dagan N, Barda N, Kepten E, Miron O, Perchik S, Katz MA, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:1412–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765

34. Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Saei A, Andrews N, Oguti B, Charlett A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet. (2021) 397:1725–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00790-X

35. Fabiani M, Ramigni M, Gobbetto V, Mateo-Urdiales A, Pezzotti P, Piovesan C. Effectiveness of the Comirnaty (BNT162b2, BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccine in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers, Treviso province, Veneto region, Italy, 27 December 2020 to 24 March 2021. Eurosurveillance. (2021) 26:2100420. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.17.2100420

36. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, Tyner H, Yoon SK, Meece J, et al. Prevention and attenuation of COVID-19 by BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines. medRxiv. (2021).

37. Shrotri M, Krutikov M, Palmer T, Giddings R, Azmi B, Subbarao S, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of the first dose of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and BNT162b2 against SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of long-term care facilities in England (VIVALDI): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2021). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3814794

38. Pawlowski C, Lenehan P, Puranik A, Agarwal V, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Niesen MJ, et al. FDA-authorized COVID-19 vaccines are effective per real-world evidence synthesized across a multi-state health system. medRxiv. (2021). doi: 10.31219/osf.io/y6pdw

39. Regev-Yochay G, Amit S, Bergwerk M, Lipsitch M, Leshem E, Kahn R, et al. Decreased infectivity following BNT162b2 vaccination: a prospective cohort study in Israel. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2021) 7:100150. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100150

40. Puranik A, Lenehan PJ, Silvert E, Niesen MJM, Corchado-Garcia J, O'Horo JC, et al. Comparison of two highly-effective mRNA vaccines for COVID-19 during periods of Alpha and Delta variant prevalence. medRxiv. [Preprint]. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.08.06.21261707

41. Katz MA, Harlev EB, Chazan B, Chowers M, Greenberg D, Peretz A, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness in healthcare personnel in six Israeli hospitals (CoVEHPI). Vaccine. (2022) 40:512–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.092

42. Cabezas C, Coma E, Mora-Fernandez N, Li X, Martinez-Marcos M, Fina F, et al. Associations of BNT162b2 vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospital admission and death with covid-19 in nursing homes and healthcare workers in Catalonia: prospective cohort study. BMJ. (2021) 374:n1868. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1868

43. Glatman-Freedman A, Bromberg M, Dichtiar R, Hershkovitz Y, Keinan-Boker L. The BNT162b2 vaccine effectiveness against new COVID-19 cases and complications of breakthrough cases: A nation-wide retrospective longitudinal multiple cohort analysis using individualised data. EBioMedicine. (2021) 72:103574. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103574

44. Zacay G, Shasha D, Bareket R, Kadim I, Hershkowitz Sikron F, Tsamir J, et al. BNT162b2 vaccine effectiveness in preventing asymptomatic infection with SARS-CoV-2 virus: a nationwide historical cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2021) 8:ofab262. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab262

45. Emborg H-D, Valentiner-Branth P, Schelde AB, Nielsen KF, Gram MA, Moustsen-Helms IR, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine against RT-PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalisations and mortality in prioritised risk groups. medRxiv. [Preprint]. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.05.27.21257583

46. Björk J, Inghammar M, Moghaddassi M, Rasmussen M, Malmqvist U, Kahn F. High level of protection against COVID-19 after two doses of BNT162b2 vaccine in the working age population - first results from a cohort study in Southern Sweden. Infect Dis (Lond). (2022) 54:128–33. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1982144

47. Monge S, Olmedo C, Alejos B, Lapeña MF, Sierra MJ, Limia A. Direct and Indirect Effectiveness of mRNA Vaccination against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Long-Term Care Facilities, Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:2595. doi: 10.3201/eid2710.211184

48. Ghosh S, Shankar S, Chatterjee K, Chatterjee K, Yadav AK, Pandya K, et al. COVISHIELD (AZD1222) VaccINe effectiveness among healthcare and frontline Workers of INdian Armed Forces: Interim results of VIN-WIN cohort study. Med J Armed Forces India. (2021) 77:S264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.06.032

49. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, Tyner HL, Yoon SK, Meece J, et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers—eight US locations, December 2020–March 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:495. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3

50. Fowlkes A, Gaglani M, Groover K, Thiese MS, Tyner H, Ellingson K, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among frontline workers before and during B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) variant predominance—eight US locations, December 2020–August 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1167. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e4

51. Bouton TC, Lodi S, Turcinovic J, Schaeffer B, Weber SE, Quinn E, et al. COVID-19 vaccine impact on rates of SARS-CoV-2 cases and post vaccination strain sequences among healthcare workers at an urban academic medical center: a prospective cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.03.30.21254655

52. Martínez-Baz I, Miqueleiz A, Casado I, Navascués A, Trobajo-Sanmartín C, Burgui C, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalisation, Navarre, Spain, January to April 2021. Eurosurveillance. (2021) 26:2100438. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.21.2100438

53. Pilishvili T, Gierke R, Fleming-Dutra KE, Farrar JL, Mohr NM, Talan DA, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine among US health care personnel. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:e90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2106599

54. Ye P, Fry L, Liu H, Ledesma S, Champion JD. COVID outbreak after the 1st dose of COVID vaccine among the nursing home residents: What happened? Geriatric Nursing. (2021) 42:1105–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.06.022

55. Pilishvili T, Fleming-Dutra KE, Farrar JL, Gierke R, Mohr NM, Talan DA, et al. Interim estimates of vaccine effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines among health care personnel-−33 US Sites, January–March 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:753. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e2

56. Martínez-Baz I, Trobajo-Sanmartín C, Miqueleiz A, Guevara M, Fernández-Huerta M, Burgui C, et al. Product-specific COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against secondary infection in close contacts, Navarre, Spain, April to August 2021. Eurosurveillance. (2021) 26:2100894. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.39.2100894

57. Carazo S, Talbot D, Boulianne N, Brisson M, Gilca R, Deceuninck G, et al. Single-dose mRNA vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare workers extending 16 weeks post-vaccination: a test-negative design from Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) ciab739. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab739 [Epub ahead of print].

58. Azamgarhi T, Hodgkinson M, Shah A, Skinner JA, Hauptmannova I, Briggs TW, et al. BNT162b2 vaccine uptake and effectiveness in UK healthcare workers–a single centre cohort study. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23927-x

59. Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, Robertson C, Stowe J, Tessier E, et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. BMJ. (2021) 373:n1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1088

60. Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B. 1.617. 2 (Delta) variant. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:585–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891

61. Bobdey S, Kaushik SK, Sahu R, Naithani N, Vaidya R, Sharma M, et al. Effectiveness of ChAdOx1 nCOV-19 Vaccine: Experience of a tertiary care institute. Med J Armed Forces India. (2021) 77:S271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2021.06.006

62. Issac A, Kochuparambil J. EPH140 SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections among the healthcare workers post-vaccination with chadox1 ncov-19 vaccine in the south indian state of kerala. Value in Health. (2022) 25:S460.

63. Rosenberg ES, Holtgrave DR, Dorabawila V, Conroy M, Greene D, Lutterloh E, et al. New COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations among adults, by vaccination status—New York, May 3–July 25, 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1306. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037a7

64. Flacco ME, Soldato G, Acuti Martellucci C, Carota R, Di Luzio R, Caponetti A, et al. Interim estimates of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in a mass vaccination setting: data from an Italian Province. Vaccines. (2021) 9:628. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060628

65. Tande AJ, Pollock BD, Shah ND, Farrugia G, Virk A, Swift M, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine on asymptomatic infection among patients undergoing Preprocedural COVID-19 molecular screening. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 74:59–65. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab229

66. Shah AS, Gribben C, Bishop J, Hanlon P, Caldwell D, Wood R, et al. Effect of vaccination on transmission of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1718–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2106757

67. Andrejko KL, Pry J, Myers JF, Jewell NP, Openshaw J, Watt J, et al. Prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) by mrna-based vaccines within the general population of california. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 74:1382–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab640

68. Fillmore NR, La J, Zheng C, Doron S, Do NV, Monach PA, et al. The COVID-19 hospitalization metric in the pre-and postvaccination eras as a measure of pandemic severity: A retrospective, nationwide cohort study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2022) 1–24. doi: 10.1017/ice.2022.13. [Epub ahead of print].

69. Chung H, He S, Nasreen S, Sundaram ME, Buchan SA, Wilson SE, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 covid-19 vaccines against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe covid-19 outcomes in Ontario, Canada: test negative design study. BMJ. (2021) 374:n1943. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1943

70. Cavanaugh AM, Spicer KB, Thoroughman D, Glick C, Winter K. Reduced risk of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19 vaccination—Kentucky, May–June 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1081. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7032e1

71. Nunes B, Rodrigues AP, Kislaya I, Cruz C, Peralta-Santos A, Lima J, et al. mRNA vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19-related hospitalisations and deaths in older adults: a cohort study based on data linkage of national health registries in Portugal, February to August 2021. Eurosurveillance. (2021) 26:2100833. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.38.2100833

72. Self WH, Tenforde MW, Rhoads JP, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, Douin DJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among adults without immunocompromising conditions—United States, March–August 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1337. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7038e1

73. Griffin JB, Haddix M, Danza P, Fisher R, Koo TH, Traub E, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections and hospitalizations among persons aged≥ 16 years, by vaccination status—Los Angeles County, California, May 1–July 25, 2021. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:1170. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e5

74. Britton A, Slifka KM, Edens C, Nanduri SA, Bart SM, Shang N, et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine among residents of two skilled nursing facilities experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks—Connecticut, December 2020–February 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:396. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7011e3

75. Butt AA, Nafady-Hego H, Chemaitelly H, Abou-Samra AB, Al Khal A, Coyle PV, et al. Outcomes among patients with breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 110:353–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.008

76. Baltas I, Boshier FA, Williams CA, Bayzid N, Cotic M, Guerra-Assunção JA, et al. Post-vaccination coronavirus disease 2019: a case-control study and genomic analysis of 119 breakthrough infections in partially vaccinated individuals. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) ciab714. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab714. [Epub ahead of print].

77. Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, Stowe J, Tessier E, Simmons R, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine and ChAdOx1 adenovirus vector vaccine on mortality following COVID-19. medRxiv. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.05.14.21257218 [preprint].

78. Glampson B, Brittain J, Kaura A, Mulla A, Mercuri L, Brett SJ, et al. Assessing COVID-19 vaccine uptake and effectiveness through the North West London vaccination program: retrospective cohort study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2021) 7:e30010. doi: 10.2196/30010

79. Moustsen-Helms IR, Emborg HD, Nielsen J, Nielsen KF, Krause TG, Mølbak K, et al. Vaccine effectiveness after 1st and 2nd dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in long-term care facility residents and healthcare workers–a Danish cohort study. MedRxiv. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.03.08.21252200 [preprint].

80. Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. Effectiveness of heterologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and mRNA prime-boost vaccination against symptomatic Covid-19 infection in Sweden: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2021) 11:100249. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100249

81. Waldman SE, Adams JY, Albertson TE, Juárez MM, Myers SL, Atreja A, et al. Real-world impact of vaccination on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) incidence in healthcare personnel at an academic medical center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2021) 42:1–7. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.336

82. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, Tyner H, Yoon SK, Meece J, et al. Prevention and attenuation of Covid-19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:320–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2113575

83. Falsey AR, Sobieszczyk ME, Hirsch I, Sproule S, Robb ML, Corey L, et al. Phase 3 safety and efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:2348–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105290

84. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:403–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

85. Chodick G, Tene L, Patalon T, Gazit S, Tov AB, Cohen D, et al. The effectiveness of the first dose of BNT162b2 vaccine in reducing SARS-CoV-2 infection 13-24 days after immunization: real-world evidence. medRxiv. [Preprint]. (2021). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3769977

86. Vasileiou E, Simpson CR, Shi T, Kerr S, Agrawal U. Akbari A, et al. Interim findings from first-dose mass COVID-19 vaccination roll-out and COVID-19 hospital admissions in Scotland: a national prospective cohort study. Lancet. (2021) 397:1646–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00677-2

87. Hunter PR, Brainard JS. Estimating the effectiveness of the Pfizer COVID-19 BNT162b2 vaccine after a single dose. A reanalysis of a study of'real-world'vaccination outcomes from Israel. Medrxiv. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.02.01.21250957 [preprint].

88. Sheikh A, McMenamin J, Taylor B, Robertson C. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. (2021) 397:2461–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1

89. Kadire SR, Wachter RM, Lurie N. Delayed second dose versus standard regimen for Covid-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:e28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMclde2101987

90. Kim JH, Marks F, Clemens JD. Looking beyond COVID-19 vaccine phase 3 trials. Nat Med. (2021) 27:205–11. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01230-y

91. Lewnard JA, Patel MM, Jewell NP, Verani JR, Kobayashi M, Tenforde MW, et al. Theoretical framework for retrospective studies of the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Epidemiology. (2021) 32:508–17. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001366

Keywords: SARS-CoV2 infection, vaccination, hospitalization, mortality, COVID-19, effectiveness

Citation: Rahmani K, Shavaleh R, Forouhi M, Disfani HF, Kamandi M, Oskooi RK, Foogerdi M, Soltani M, Rahchamani M, Mohaddespour M and Dianatinasab M (2022) The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality from COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 10:873596. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.873596

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 26 July 2022;

Published: 26 August 2022.

Edited by:

Vijay Kumar, Louisiana State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mojtaba Keikha, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, IranMahmoud Khodadost, Larestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2022 Rahmani, Shavaleh, Forouhi, Disfani, Kamandi, Oskooi, Foogerdi, Soltani, Rahchamani, Mohaddespour and Dianatinasab. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rasoul Shavaleh, cmFzb3VsLnNoYXZhbGVoJiN4MDAwNDA7Z21haWwuY29t

Mostafa Dianatinasab bS5kaWFuYXRpbmFzYWImI3gwMDA0MDttYWFzdHJpY2h0dW5pdmVyc2l0eS5ubA==

†ORCID: Mostafa Dianatinasab orcid.org/0000-0002-0185-5807

Kazem Rahmani1

Kazem Rahmani1 Mostafa Dianatinasab

Mostafa Dianatinasab