95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 25 May 2022

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.871468

This article is part of the Research Topic Accessible Health Programs Promoting Physical Activity and Fitness Level View all 14 articles

This study was conducted to develop evaluation indicators for instructor-led management of sports centers for the disabled using universal design (UD) principles in South Korea. These indicators have been developed through Delphi technique to identify the effectiveness of an instructor's management skills. There were 11 documents related to UD used in the literature review, and seven were related to the evaluation index. Through reading and analyzing the relevant contents of the collected literature and many rounds of the Delphi technique, we selected the method and criteria for deriving the evaluation index. In this study, we developed a method that constitutes an evaluation index. The index comprises one evaluation criterion and four evaluation indices. First, for the sub-items of the “recruitment” category, four principles of UD and one supplementary principle of product performance program (PPP) were applied to create items for the evaluation index. Second, the sub-items of the “education” category comprise three evaluation criteria and 10 evaluation indicators. These were applied to the fourth principle of UD and the first and second by-supplementary principles of PPP. The third category, “welfare,” comprised two evaluation criteria and six evaluation indices, and the first by-supplementary principle of PPP was applied to the evaluation indices. The index created for evaluating instructors in sports centers using the method elucidated in this study was adequately reliable. Following a similar method, more evaluation indicators should be developed for evaluations of other functions (such as programs, public relations, safety, and finance) based on the principles of UD.

Universal Design (UD) was introduced in the 1970s by Ronald Mace, an American architect and product designer with disabilities (1). UD considers human diversity in the design of products and spaces and follows the design of architects and designers (2). In addition, UD aims to create not only a value system that informs the design of environments but also products that meet the needs of all users (3).

UD is already in use in various fields in our society. It is utilized not only in building centers but also in education, IT, and medicine. In particular, in most developed countries, UD is employed in fields that regularly include people with disabilities and members of the general public to provide spaces accessible and practical for everyone; they do not distinguish between spaces used by people with disabilities and those used by others. In other words, in UD spaces, the whole room, building, complex, or facility seamlessly accommodates all members of a diverse population rather than designating distinct, separate spaces intended for individuals with particular disabilities (1, 4, 5).

In most developed countries, UD environments are being created for use by the disabled and non-disabled together. Likewise, Korean governments are also aware of the importance of UD and are planning to build and expand a sports center for the disabled incorporating UD. It has planned to build 30 centers in 2019, 23 centers in 2020, and 30 centers in 2021. In total, the number of sports centers for the disabled will be expanded to 150 by 2025 (6).

In this background, we aimed to create a continuous legacy along with the successful hosting of the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Paralympics. The name of the Bandabi Sports Center was created in honor of “Bandabi,” the mascot of the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Paralympics in support of guarantees of the priority rights for the disabled and to support the selection of regional customized models suitable for regional characteristics among gymnasiums, swimming pools, and sports specialized models as integrated sports centers used by non-disabled people. In particular, the Bandabi Sports Center was built as a UD because Rep. Kim emphasized it should be built as a national sports center for both the disabled and the general public without emphasizing the disabled (7).

Based on the UD principle, recruiting and managing instructors who are able to operate sports programs for patrons with disabilities is important for effectively distinguishing gyms that accommodate users with disabilities from what previously were “regular” gyms. In other words, a UD sports facility for the disabled can be considered “well-operated” when all of the instructors recognize and guide the concept of UD.

Over the years, many studies related to UD have been conducted, including some research combining UD with sports (8–10), such as studies of UD-related learning (11–14) and UD-related program and device development (15, 16). Research on spatial architecture incorporating UD (17, 18) and one study on the concept establishment of UD (19) have also been conducted. In addition, research on evaluation indicators for the management of sports instructors included a study on instructorship education ability evaluation (20, 21), a study on policy development (22, 23), and a study on leadership role based on the development of leadership education programs (24). Their research presents various discussions, including the reasons for grafting UD, the advantages and disadvantages of UD, and improvement measures. However, there is a scarce study in the development of evaluation indicators for the management of instructors of sports centers for the disabled incorporating UD.

We found one paper that was contextually similar to the present study: Watchorn et al. (25) considered occupations for inclusion in the discourse about architectural environments incorporating UD. The researchers combined quantitative and qualitative methods to present discourses on the jobs that are necessary and the people who are suitable for the UD occupations. Although many UD environments are incorporated into our society, the researchers concluded that such occupations should be created because there are not yet any suitable people for the various types of jobs necessary to operate UD centers and businesses. However, it can be seen that there are some differences between the available literature and this study: we aimed to clarify how to assess and manage instructors who work with all types of users, able-bodied or otherwise, in UD sports centers. Therefore, in this study, it is time to develop evaluation indicators for instructor management of sports centers for the disabled based on UD in Korea.

Therefore, the purpose was to develop an evaluation index that can evaluate the suitability of hiring and managing instructors in UD-based sports centers for the disabled based on the analysis results. This study examined the opinions on what UD elements should be employed and managed by instructors of sports centers for the disabled based on the UD principle through Delphi technique were collected and analyzed.

The indicators for the evaluation of sports instructors at all centers for disabled people to which UD was applied were derived over a total of four stages. As a first step, the extent of incorporation of the UD elements and the method of deriving evaluation indices were determined through literature research. In the second step, 17 chosen experts were subjected to the first modified Delphi technique. Among the seven principles of UD and three supplementary principles of product performance program (PPP), three elements to be reflected in the evaluation index, evaluation criteria, and evaluation index items were extracted and classified. The Delphi panel configuration is shown in Table 1.

As the third step, the second modified Delphi technique was carried out to confirm and revise the reflection factors of UD, evaluation criteria, and classification results of evaluation indicators. The final methodology step was to confirm the degree of agreement among experts regarding the evaluation categories, the criteria for selection, and index contents. This was done by using Kendall's Coefficient of Concordance W (Kendall's W) analysis and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). The detailed research procedure is shown in Figure 1.

Eleven documents related to UD were used in the literature review, and seven documents related to the construction of the evaluation index. These documents were carefully analyzed, the results helped in setting the scope of evaluation indicators to be reflected in this study. The scope of UD was applied using the Center for Universal Design (1997) and the proposed Universal Design Product Performance Program (PPP) (26). The modified Delphi technique was assessed as suitable for constructing the evaluation index. Accordingly, a structured questionnaire enquiring about the UD factors was prepared for the method. The validity of this analysis was verified through Kendall's W; the ICC reliability was also verified.

Delphi is a technique that requires the collective judgment of experts in the relevant field. As a consequence, the selection of experts is very important in the Delphi investigation process. Regarding the necessary number of experts participating in the Delphi technique, useful results can be obtained with a small group of 10–15 people (27, 28). A total of 17 field experts were selected as Delphi panels. The Delphi process was implemented over three rounds. In the first round, to incorporate the UD principles in the evaluation criteria, the UD content had to be applied to the evaluation index that was shared with the selected panel by e-mail and was further explained through phone calls or in-person interviews. This enabled multiple UD elements to be applied to the program evaluation index of the gymnasium for the disabled. In addition, it was possible to describe the index items required to operate the program. In the second round of the Delphi process, the results extracted and classified during the first round were shared with the experts by e-mail, and additional opinions to be added or modified in the results were recorded through text analysis. In the third Delphi round, a questionnaire was administered using a 5-point Likert scale to assess the suitability of the evaluation index items to confirm the consensus of the panel on the results extracted during the first and second rounds. To verify the suitability and validity of the evaluation indices, frequency analysis, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) reliability analysis, and Kendall's W analysis were conducted using SPSS 21.0. These tests confirmed the degree of agreement among the experts regarding the selections made, and the ranking of each item was analyzed to refine the attributes further.

ICC verification indicates the correlation between the evaluators of the measurement tool. ICC provides relatively stable values when the sample size is small (29). When the reliability index is 0.8 or higher, it shows very high reliability, 0.6 or higher means relatively high reliability, 0.4 or higher refers to moderate reliability, and 0.2 or higher means determined to reasonable reliability (30). Although this index cannot be called absolute, it is often used because it is considered useful (31).

Kendall's W is a method used for checking the degree of agreement among evaluators. It is used when multiple evaluators assess the same subject, and it is measured on an equality scale and a ratio scale. The W value represents a number from 0 to 1, and the closer the value is to 1, the higher the degree of consensus, and the closer it is to 0, the more disagreement there is among the experts (32).

UD is a concept created to be applied to architecture or product design, but it was also introduced in learning in 1989 by The National Center for Accessing the General Education Curriculum in the US. The universal design for learning (UDL) was instituted as a new paradigm (33, 34). UDL considers that the difficulty of incorporating the seven UD principles into learning directly and, thus, alternatively provides three core UDL principles (various presentation methods, various expression methods, and various participation methods) to be utilized (35). In this study, the researchers also judged that, as it was, it was too difficult to apply the program to the seven UD principles or the three supplementary principles of PPP to develop program evaluation indicators. Therefore, the expert group selected all seven UD principles and the three supplementary principles that were deemed applicable to the program evaluation index in the first Delphi round. In addition, the UD-based elements constituting the program evaluation index of the sports facility for the disabled were described.

Seven studies were selected for creating an evaluation index, and their methods of research and analysis were analyzed. On the basis of this analysis, to derive the results of this study, it was determined that the modified Delphi technique was the most suitable. “Modified Delphi” refers to the case where the content is not structured by the panel, but the researcher uses a structured questionnaire from the beginning (36). The reason for choosing this method was that the UD concept is broad, and the range of differences in interpretation is likely to be large when applied to the sports program aspect. Therefore, it was decided that the Delphi technique should be conducted after first extracting items for the index with the seven UD principles and the three supplementary principles of PPP. Kendall's W was selected as the method of analysis. The same method of analysis was used in a previous study using the Delphi survey, which is known to be the most suitable among the non-parametric tests used with the above-mentioned survey. The closer the W index gets to 1, the stronger the consensus (37).

The first Delphi round surveyed the scope of applicability of UD's seven principles and the three supplementary principles to the program evaluation index for the panel and allowed them freedom to describe the essential elements of the Instructor evaluation index. While enquiring about the applicability range of UD's seven principles and three supplementary principles, the first priority of experts was “Product Quality and Aesthetics;” the second priority was the “Perceptible information,” and lastly, they prioritized the “Human environmental consideration.” Detailed results are shown in Table 2.

In addition, the elements that must be included in the index that evaluates the instructor of the sports facility for the disabled were classified into six evaluation criteria and 22 evaluation indices. The detailed results are shown in Table 3.

In the second round of the Delphi process, the evaluation index was classified into three categories by confirming and revising the results of the first Delphi round, wherein two evaluation indices were deleted. With regards to the second deleted indicator, they explained that the “Priority hiring of professional sports instructors for the disabled” has the same meaning as the indicator “Priority hiring experienced sports instructors for the disabled and those who majored in special sports,” and hence does not need to be considered.

The panel finally selected three principles as suitable to be applied to evaluate sports instructors (Principle 4: Perceptible information, supplementary principles 1: Product Quality and Aesthetics, 2: People's Health and the Natural Environment). This selection was made out of a total of seven UD principles and three supplementary principles. The panel also confirmed that these deletions were reflected in the evaluation index depending on their meaning and intention. Accordingly, the evaluation index was modified during the second Delphi and was further divided into six evaluation criteria according to three categories (selected principles). These six evaluation criteria were then expanded into an evaluation index of 20 items. The evaluation indicators classified as secondary are shown in Table 4.

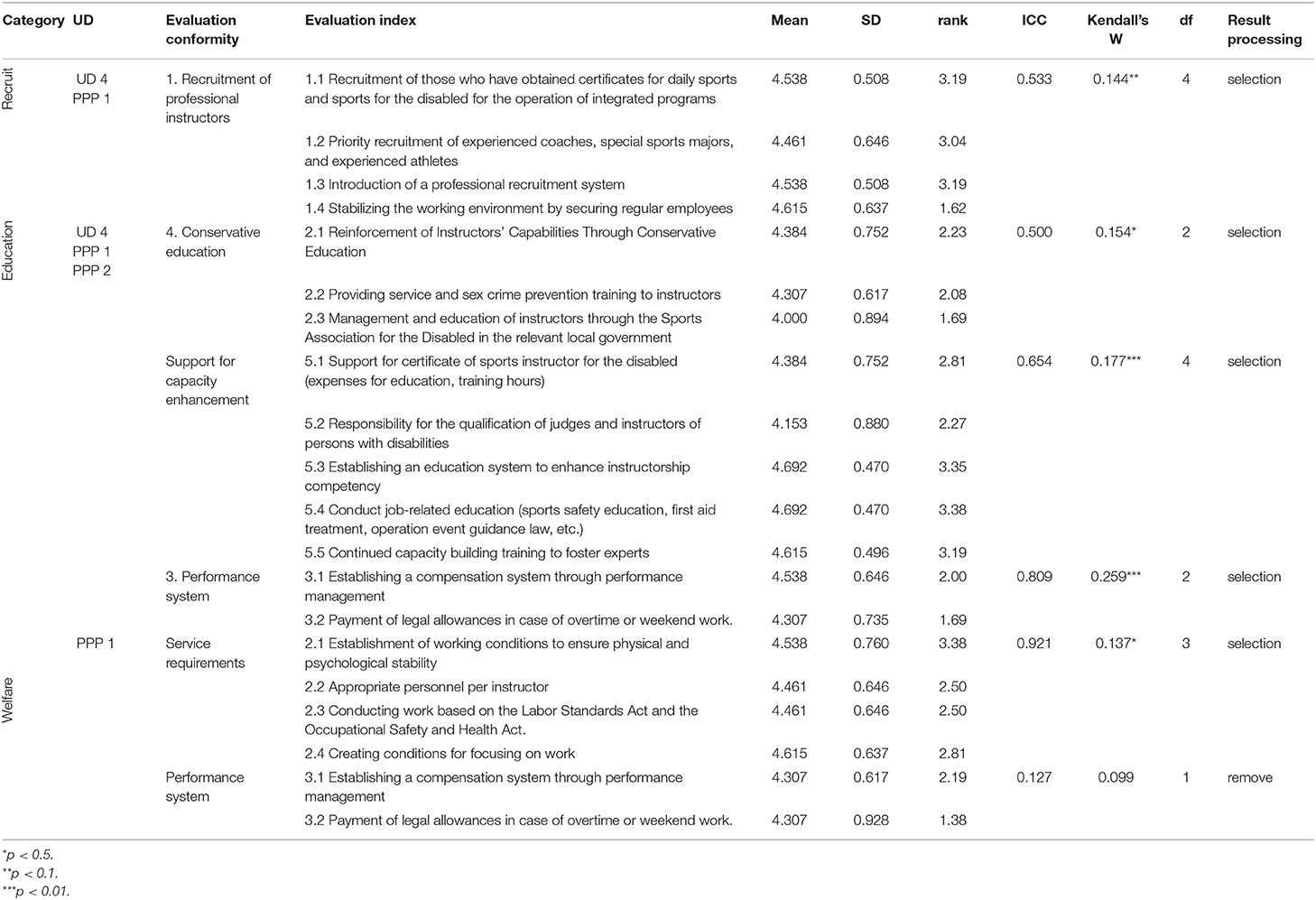

In order to verify the validity and reliability of the evaluation indices obtained in the previous round, in the third Delphi round, the panel was asked to respond to a 5-point Likert scale indicating whether the contents of the evaluation index were appropriate. The results are shown in Table 5. To establish the statistical strengths of the evaluation index, we checked the average value and standard deviation value of the index. Data on the quantitative part of the questionnaire can be measured using average scores as a standard measure of the indicator's importance.

Table 5. Contents of evaluation index and Results of analysis of reliability, and validity of evaluation indicators.

According to Linstone and Turoff (37), average values can be used to determine whether expert opinions on questionnaire items are consistent and stable (38). Secondly, the ICC index was confirmed by the verification of reliability. Since previous studies have stated that the value of the ICC is valid above 0.2, all items with scores below 0.2 were targeted for removal. Hence, the reliability index of “the performance system” was removed, as it had an ICC value of 0.127. Finally, the results of Kendall's W verification showed that there were statistically significant agreements in five evaluation criteria out of the six. The criteria for evaluation that did not match was the “achievement system.” Accordingly, the “achievement system” of “welfare” was removed, and the remaining five criteria were added.

This study has developed the evaluation indicators for instructor management of sports centers for the disabled following the UD principle. Using Delphi technique we determined which UD elements should be employed and managed by instructors of UD principle-based sports centers for the disabled. Hence, an evaluation index for assessing the suitability of hiring and managing instructors in UD principle-based sports centers for the disabled was created. In this section, we would like to discuss further the meaning of the development of evaluation indicators.

First, the results of a literature survey on UD revealed seven principles and three supplementary rules of commonly used UD. The seven principles were fair use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, recognizable information, tolerance for mistakes, small physical efforts, size, and space for approach and use. The three supplementary rules were the pursuit of quality and psychology, consideration of the human body and the environment, and economic feasibility and validity. In addition, based on previous studies, evaluation indicators were developed through Delphi surveys.

According to previous studies, it can be seen that UD is a necessary element in the present era. In addition, according to UD's definition, it is predicted that it will be applied in various fields (1). Currently, the society we live in is changing into a fast and diverse society (38). In other words, it is important that UD technology, which can be conveniently used together, is applied not only to the hardware field but also to software. Although UD technology has already been applied and actively utilized in various fields other than the field of sports (39–42), it remains to be seen whether it is well applied and operated.

In an environment related to the disabled, even if the centers are good, the impact on the disabled depends on the ability of the instructor (43). Therefore, the management of the instructor who guides the disabled or the evaluation of the instructor's ability should be prioritized (44). In particular, the ability of the instructor is more important for exercise (45). In elite games, the ability of the instructor determines whether the team will win or lose. Similarly, in sports for all, depending on the level of knowledge and various experiences of the instructor, it is possible to continue with fun in sports without injury. A qualified and effective instructor is particularly key for safe and successful exercise for people with disabilities. The disabled have more things to pay attention to than the general public, so expertise in the disabled and experience in guiding the disabled movement is very important.

Therefore, it is necessary to not only select professional instructors but also evaluate them. Various studies related to people with disabilities have also emphasized the importance of evaluation indicators for leadership management (46–51). However, research on the instructor evaluation index of sports centers for the disabled incorporating UD is still insufficient. Therefore, this study would be meaningful to select and analyze questions that fit the instructor management evaluation index through the principle of UD. Moreover, UD will be applied, operated, and expanded in many places throughout our society in the future. Likewise, the practical approach to the development of the instructor evaluation index of sports centers for the disabled based on UD technology is considered an especially important practice.

Second, according to the results of the Delphi survey of the expert group, a large category of evaluation indicators was set for recruitment, education, and welfare. First, recruitment factors appeared to be important in hiring. The evaluation index in recruitment was found to stabilize the working environment by supporting the hiring of people with daily sports and sports certificates for the integrated program operation; establishing preferential recruitment of experienced athletes and special sports majors; introducing a professional recruitment system; and securing regular employees.

This study was conducted based on sports centers. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to select a professional sports instructor. In particular, the expertise of sports for the disabled is noticeable (52). Professionalism includes obtaining certificates, experiences of professional study related to the disabled, and experiences of working in occupations related to the disabled. However, the most important thing is whether someone has direct experience in the field of sports for the disabled. Due to the extent of the differences in the sports-related characteristics of people with disabilities, the instructors with direct experience teaching sports to the disabled must be hired first (8, 53–56).

In addition, stabilization of the working environment is of paramount importance. In the case of Korea, it continues to raise questions about the working environment of sports instructors for the disabled (57). In order to solve the stabilization of the working environment for disabled people, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of Korea has increased its budget since 2015. However, the problem of the working environment of sports instructors with disabilities in Korea has not disappeared and is continuously making claims for improvement (57). Likewise, even if a sports facility for the disabled based on the UD principle is completed, the expansion project of these centers will be ruined if the working environment of employees working there is not stabilized. The utilization rate of people who use this place and the disabled among them will be high. One study argued that disabled people in Korea would actively participate in exercise if they had space to exercise near their residence (58). As shown in the study, space is more important than anything else for the disabled, but if there is no one to guide the disabled in the exercise space, it is judged that this is a result of not seeing a distant future. Therefore, stabilizing the working environment of full-time employees is the most important matter.

In terms of education, conservative education, capacity building, and expertise building are considered most important. The evaluation indicators of conservative education are strengthening leadership capabilities through conservative education, service and sex crime prevention education for instructors, and leader education through sports associations for the disabled in local governments. The evaluation indicators for competency building are sports instructor certification support for the disabled, the duty of the disabled to acquire referee and instructor qualifications, the establishment of an education system to strengthen leadership competency, job-related education, and continuous competency building education. Finally, the evaluation indicators for strengthening expertise are UD instructor training education, UD-related seminars in sports centers for the disabled, and educational support.

In certain organizations, groups, organizations, etc., educational support from members is one of the most important parts (59). In particular, job training is very important in the field of exercise instruction. Its importance is further highlighted in the field targeting the disabled (60). In addition, there are also exercises that people with disabilities can do alone, but in most cases, someone has to assist them. Therefore, it is necessary to be accurately aware of sports safety education, first aid education, and operation education for sports. Even if it is a simple method, it is difficult to master it without experiencing it; thus, operation experience is essential.

There is a growing trend of incorporating UD principles into designs for sports centers for the disabled. UD designs may include elements of the space, centers, and equipment that differ from what is generally expected in “traditional” gyms and sports complexes. Reports from regions overseas where UD principles have long been used in construction emphasize that because UD centers are marked differences compared to general centers, the education of leaders and users must be prioritized to maximize the usability of UD centers (61). The recommended education is, above all, related to expertise. Thus, guidelines are needed for sports centers for the disabled incorporating UD, and evaluations of each center's performance should be based on how well they are following those guidelines.

Above all, in sports centers for the disabled, the instructors' service to facility users is important (59, 62). Even with elite disabled athletes familiar with sports, conflicts with instructors continue to occur (63). Therefore, it is paramount that the kindness of instructors is also evaluated. It is of paramount importance for instructors to demonstrate kindness beyond the times when they are providing movement guidance. If these details are included in education and applied to the evaluation index, both the economic level and the social culture of Korea will advance.

Finally, working conditions and performance systems were important in welfare. The evaluation index for working conditions was found to prepare working conditions to ensure physical and psychological stability, arrange appropriate personnel per instructor, conduct tasks based on the Labor Standards Act and the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and create conditions for concentration of assigned departments. The evaluation indicators of the performance system were found to establish a compensation system through performance management, overtime, and payment of legal allowances for weekend work.

Many office workers worldwide value the welfare of their workplace. This value is also paramount to work-life balance (64–66). Additionally, sufficient rest positively affects and increases work efficiency. In the case of Korea, a five-day workweek is operated. However, it is one of the countries with the highest working hours among OECD countries. The happiness index is one of the low countries (67). This means that life in Korea is not happy. For happiness, the welfare of workers should be prioritized, and it should not be forgotten that well-being jobs have a positive impact on performance in the end.

Therefore, even in sports centers for the disabled based on the UD principle, it is important to evaluate the welfare of workers. Also, instructors in sports centers who work with people with disabilities must provide more guidance (and more frequent guidance) to their clients compared to instructors who work with the general public. Work that requires more concentration—and more attention to more details—can generate more work stress for these instructors (59, 62). The heightened level of attention and potential stress for instructors in UD sports centers should be included in the evaluation index, and heightened stress should be evaluated. In addition, careful assessment to determine whether an appropriate compensation system has been implemented was found to be an evaluation point that can clearly motivate workers. When each element of the evaluation items are applied well, investments in UD principle-based sports centers for the disabled will increase, and utilization of the UD sports centers will also be increasingly more positive.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate and analyze the UD factors related to sports instructors that should be reflected in the assessment and operation of sports centers for the disabled. Using the Delphi technique with experts, we developed evaluation indicators to assess the hiring and training of instructors and measure the instructors' management skills.

The evaluation index developed through the literature review and subsequent rounds of the Delphi techniques consisted of three categories: “recruitment,” “education,” and “welfare.” First, we established the sub-items of the “recruitment” category consisting of one evaluation criterion and four evaluation indices. Supplementary principles, based on the fourth UD principle (recognizable information) and the supplementary principles of PPP (Product Quality and Aesthetics), were also identified as relevant to the study's aims and applied to the evaluation index. Second, we developed the sub-items of the “education” category consisting of three evaluation criteria (remedial education, capacity building, specialization strengthening) and 10 evaluation indices. These were based on the fourth UD principle and the first and second sub-principles of PPP (People's Health and the Natural Environment). The third category, “welfare,” comprises two evaluation criteria (work conditions and achievement system) and six evaluation indices derived from PPP's first supplement. The chosen welfare category items were also applied to the evaluation indices.

Based on our findings and the evaluation indices, the recommendations of this study are as follows: First, the work of validating the evaluation indices should be carried out by applying the developed evaluation index to instructors and operators of public sports centers and sports centers for the disabled that offer integrated programs. Second, more evaluation indicators are needed (and should be developed) for other functions—such as programs, public relations, safety, and finance—of sports centers for the disabled based on the UD principles. An awareness education program promoting and clarifying the UD concept and informing the public about the purpose of the centers is needed to ensure the provision of a fair and comfortable environment wherein everyone has access to UD sports centers. Moreover, steps should be taken to guarantee that everyone can easily and conveniently patronize the centers.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

EY and AO: original draft preparation. AO: data analysis. EY and JS: critical review of the contents. AO and JS: data collection and critical review of the manuscript. AO, JS, and EY: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research project was supported by the Sports Promotion Fund of Seoul Olympic Sports Promotion Foundation from Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism of the Republic of Korea (R&D/1375026989).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

2. Connell, et al. Principles of Universal Design. (1997). Available online at: http://www.design.ncsu.edu/cud/about_ud/udprinciples.htm (accessed July 27, 2009).

3. Mcguire JM, Scott SS, Shaw SF. Universal design and its applications in educational environments. Remedial Spec Educ. (2006) 27:166–75. doi: 10.1177/07419325060270030501

4. David R. Walking the walk: universal design on the web. J Spec Educ Technol. (2000) 15:45–9. doi: 10.1177/016264340001500307

5. Thunberg G, Johnson E, Bornman J, Öhlén J, Nilsson S. Being heard - supporting person-centred communication in paediatric care using augmentative and alternative communication as universal design: A position paper. Nurs Inq. (2021) 29:1–14. doi: 10.1111/nin.12426

6. Ministry of Culture Sports Tourism. (2018). Available online at: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_notice/press/pressView.jsp?pSeq=16824 (accessed January 10, 2022).

7. Lee SG. Bandabi Sports Center, low tide? “Discrimination against people with disabilities”. Able News. Available online at: http://abnews.kr/1RoW (accessed January 10, 2022).

8. Nikolajsen H, Sandal LF, Juhl CB, Troelsen J, Kristensen BJ. Barriers to, and facilitators of, exercising in fitness centres among adults with and without physical disabilities: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:7341. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147341

9. Gurgis JJ, Kerr GA. Sport administrators' perspectives on advancing safe sport. Front Sports Act Living. (2021) 3:630071. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.630071

10. Shen Y, Ross S, Dyson B. Social and emotional learning for underserved children through a sports-based youth development program grounded in teaching personal and social responsibility. Phys Educ Sport. (2022) 27:1–17. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2022.203961427

11. Cumming TM. Rose MC. Exploring universal design for learning as an accessibility tool in higher education: a review of the current literature. Aust Educ Res. (2021) 235:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s13384-021-00471-7

12. Flanagan S. Morgan JJ. Ensuring access to online learning for all students through universal design for learning. Teach Except Child. (2021) 53:459–62. doi: 10.1177/00400599211010174

13. Flood M, Banks J. Universal design for learning: is it gaining momentum in Irish education? Educ Sci. (2021) 11:115–26. doi: 10.3390/educsci11070341

14. Xie J, Rice MF. Professional and social investment in universal design for learning in higher education: insights from a faculty development program. J Furth High Educ. (2021) 45:886–900. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1827372

15. Júlia GF, Struyven K, Vantieghem W. Toward more inclusive education: an empirical test of the universal design for learning conceptual model among preservice teachers. J Teach Educ. (2021) 72:381–95. doi: 10.1177/0022487120965525

16. Tobin TJ. Reaching all learners through their phones and universal design for learning. J Adult Learn Knowl Innov. (2021) 4:9–19. doi: 10.1556/2059.03.2019.01

17. Dikmen CB, BozdemIr G. Universal design approach in shopping centers: sample of Kayseri. J Sci B Art Humani Des Plan. (2021) 9:217–34. Available online at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/1936917

18. Paykoc E, Ballice G, Güler G. Evaluation of playgrounds in terms of universal design: Izmir, Karşiyaka coast after Izmir Deniz project. Game Des Educ. (2021) 13:35–51. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-65060-5_3

19. Coffman S, Draper C. Universal design for learning in higher education: a concept analysis. Teach Learn Nurs. (2021) 16:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.teln.2021.07.009

20. Lyle J. Lessons learned from programme evaluations of coach development programmes in the UK. Can J Study Adult Edu. (2021) 33:35–50. Available online at: http://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/7114/1/LessonsLearnedFromProgrammeEvaluationsOfCoachDevelopmentProgrammesIn TheUKAM-LYLE.pdf

21. McCarthy L, Allanson A. Stoszkowski J. Moving toward authentic, learning-oriented assessment in coach education. Int Sport Coach J. (2021) 8:400–4. doi: 10.1123/iscj.2020-0050

22. Kiosoglous C, Callary B. Policy Development for Coached Masters Sport: Possibilities and Problematization, Coaching Masters Athletes. 1st Ed. Milton Park: Routledge (2021).

23. Varmus M, Kubina M, Adámik R. Sustainable management of sports organizations. Strateg Sport Manage. (2021) 212:87–142. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-66733-7_4

24. Kelly S, Regan NO. The union of european football associations (2020) coaching convention update and coach education in the football association of Ireland. Int Sport Coach J. (2021) 8:382–93. doi: 10.1123/iscj.2020-0090

25. Watchorn V, Hitch D, Grant C, Tucker R, Aedy K, Ang S, et al. An integrated literature review of the current discourse around universal design in the built environment – is occupation the missing link? Disabil Rehabil. (2021) 43:1–12. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1612471

27. Anderson ET. Important Distance Education Practices: A Delphi Study of Administrators and Coordinators of Distance Education Program in Higher Education. Idaho: University of Idaho (1997). p. 228.

28. Ziglio E. Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers (1996). p. 3–33.

29. Terry K. Koo, Mae Y. Li. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropract Med. (2016) 15:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

30. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. (1977) 33:159–74. doi: 10.2307/2529310

31. Donner A, Eliasziw M. Sample size requirements for reliability studies. Stat Med. (1987) 6:441–8. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060404

32. Schmidt RC. Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decis Sci. (1997) 28:763–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.1997.tb01330.x

33. Scott SS, Mcguire JM, Shaw SF. Universal design for instruction: A new paradigm for adult instruction in postsecondary education. Remedial Spec Educ. (2003) 24:369–79. doi: 10.1177/07419325030240060801

34. Kortering LJ, McClannon TW, Braziel PM. Universal design for learning: a look at what algebra and biology student with and without high incidence conditions are saying. Rem Spec Educ. (2008) 29:352–63. doi: 10.1177/0741932507314020

35. Murry JW, Hammons JO. Delphi: A versatile methodology for conducting qualitative research. RHE. (1995) 18:426–36. doi: 10.1353/rhe.1995.0008

36. Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manage. (2004) 42:5–29. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

37. Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications [Electronic Version]. Newark, NJ: New Jersey Institute of Technology (2002).

38. Fontaine RG. On-line social decision making and antisocial behavior: some essential but neglected issues. Clin Psychol Rev. (2008) 28:17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.004

39. Grangaard S. How to communicate universal design to architects on a new website? A reflection on the type of knowledge requested. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2021) 4:301–14. doi: 10.3233/SHTI210406

40. Levey JA, Burgstahler S. Montenegro E, Webb A. COVID-19 pandemic: universal design creates equitable access. J Nurs Meas. (2021) 29:185–7. doi: 10.1891/JNM-D-21-00048

41. McNutt L. Craddock G. Embracing universal design for transformative learning. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2021) 4:176–82. doi: 10.3233/SHTI210394

42. Scheirer TF. Using universal design principles in a fundamentals course to promote student transition to nursing education. Nurs Educ Perspect. (2021) 42:111–3. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000672

43. Kim Y, Lee S. Effects of physical exercise on women with disabilities in south korea: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312791

44. Kalyanpur M. Development, Education and Learning Disability in India. Berlin: Springer Nature: Palgrave Studies in Disability and International Development (2021).

45. Krops LA, Geertzen JHB, Horemans HLD, Bussmann JBJ, Dijkstra PU. Dekker R. Feasibility and short-term effects of Activity Coach: a physical activity intervention in hard-to-reach people with a physical disability. Disabil Rehabil. (2021) 43:2769–78..doi: 10.1080/09638288.2020.1717650

46. Brannick MT, Levine EL. Job Analysis: Methods, Research, and Applications for Human Resource Management in the New Millennium. London: Sage Publications (2002)

47. Jeannerex PR. Strong MH. Linking O-NET job analysis information to job requirement predictors: An O-NET application. Pers Psychol. (2003) 56:465–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00159.x

49. Raymond MR. Job analysis and the specification of content for licensure and certification examinations. Appl Meas Educ. (2001) 14:369–415. doi: 10.1207/S15324818AME1404_4

50. Domingos J, Família C, Fernandes JB, Dean J, Godinho C. Is being physically active enough or do people with parkinson's disease need structured supervised exercise? Lessons learned from COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:2396. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042396

51. Soyer F, Gülle M, Mizrak O, Zengin S, Kaya E. Analysis of resiliency levels of disabled individuals doing sports according to some variables. Univ J Phys Educ Sport Sci. (2013) 7:126–36. Available online at: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1032459

52. Antoine K. The role of the coach in training the athlete with a disability. Br J Ther Rehabil. (2013) 3:436–9. doi: 10.12968/bjtr.1996.3.8.14789

53. Fontan L, Fraval M, Michon A, Déjean S, Welby-Gieusse M. Vocal problems in sports and fitness instructors: a study of prevalence, risk factors, and need for prevention in France. J Voice. (2017) 31:261. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2016.04.014

54. Kraft E, Leblanc R. Instructing children with autism spectrum disorder: examining swim instructors' knowledge building experiences. Disabil Health J. (2018) 11:451–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.11.002

55. Mavritsakis O, Treschow M, Labbé D, Bethune A, Miller WC. Up on the hill: the experiences of adaptive snow sports. Disabil Rehabil. (2021) 43:2219–26. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1692379

56. Richardson EV, Smith B, Papathomas A. Disability and the gym: experiences, barriers and facilitators of gym use for individuals with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. (2017) 39:1950–7. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1213893

57. Ministry of Culture Sports Tourism. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_data/budget/budgetView.jsp?pSeq=847&pMenuCD=0413000000. (accessed March 30, 2020).

58. Perreault S, Vallerand RJ. A test of self-determination theory with wheelchair basketball players with and without disability. Adapt Phys Act Q. (2007) 24:305–16. doi: 10.1123/apaq.24.4.305

59. Rimmer JH., Padalabalanarayanan S, Malone LA, Mehta T. Fitness facilities still lack accessibility for people with disabilities. Disabil Health J. (2017) 10:214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.12.011

60. Luke EK. Adapted Physical Education National Standards. 3 ed. Champaign, IL. Human Kinetics (2019).

61. Molly Follette Story MS. Maximizing usability: the principles of universal design. Official J RESNA. (1998) 10:4–12. doi: 10.1080/10400435.1998.10131955

62. Orr K, Evans MB, Tamminen KA, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP. A scoping review of recreational sport programs for disabled emerging adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. (2020) 91:142–57. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2019.1653432

63. Page SJ, Martin SB, Wyda VK. Attitudes toward seeking sport psychology consultation among wheelchair basketball athletes. Adapt Phys Activ Q. (2001) 18:183–92. doi: 10.1123/apaq.18.2.183

64. Gragnano A, Simbula S, Miglioretti M. Work-life balance: weighing the importance of work-family and work-health balance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:907. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17030907

65. Lucia-Casademunt AM, García-Cabrera AM, Padilla-Angulo L, Cuéllar-Molina D. Returning to work after childbirth in europe: well-being, work-life balance, and the interplay of supervisor support. Front Psychol. (2018) 6:68. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00068

66. Seo HY, Lee DW, Nam S, Cho SJ, Yoon JY, Hong YC. Lee N. Burnout as a mediator in the relationship between work-life balance and empathy in healthcare professionals. Psychiatry Investig. (2020) 17:951–9. doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0147

67. The World Happiness Report. (2021). Available online at: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2021/happiness-trust-and-deaths-under-covid-19/ (accessed March 20, 2021).

Keywords: universal design, disability, Delphi technique, instructor management, sports centers

Citation: Yi E, Shin J and Oh A (2022) Developing Indicators to Evaluate Instructor Management of Sports Centers for the People With Disabilities Based on Universal Design Principles in South Korea. Front. Public Health 10:871468. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.871468

Received: 08 February 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 25 May 2022.

Edited by:

Guoxin Ni, Beijing Sport University, ChinaReviewed by:

Seokmin Yun, Yeungnam University, South KoreaCopyright © 2022 Yi, Shin and Oh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jongseob Shin, anN0a2Q2OEBnbWFpbC5jb20=; Ahra Oh, b2gteWFuZzAzMjlAaGFubWFpbC5uZXQ=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.