- 1Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States

- 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

- 3Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States

- 4Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

- 5Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

- 6Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

As health care continues to evolve, training the next generation of healthcare leaders is more important than ever. However, many university undergraduate students are not directly exposed to topics such as health policy and management within their coursework or co-curricular engagements. At Duke University, we developed the Student Collaborative on Health Policy (SCOHP) as an inter-disciplinary health policy hub that offers opportunities for learning, engagement, and leadership in the healthcare-related fields for students of all academic backgrounds. We see opportunity for similar student-led groups to be established by student leaders at other institutions, increasing interaction with experts, mentorship and the accessibility of experiential education, service, and leadership in the health care sector.

Introduction

Tackling tomorrow's health system challenges will require a workforce equipped with the tools to improve healthcare value and equity. With a national commitment to care re-design and payment reform, the next generation of healthcare leaders will need to work across sectors and professions, including clinical care, administration, public service, research, and industry. Universities can play a critical role in developing the pipeline of healthcare leaders, as early as at the undergraduate level.

Unfortunately, few universities offer undergraduate students adequate exposure to health policy and management through curricular and co-curricular programming. While some institutions include a health policy and management track within public health majors (1), these programs may only reach a small percentage of students interested in healthcare careers. There is a need for scalable and sustainable models to engage undergraduate students across degree programs.

One model for engagement is student organizations, which are effective outlets for students to develop leadership and professional skills, serve their local communities, and develop a supportive network of peers with similar interests (2–4). At Duke University, we developed the Student Collaborative on Health Policy (SCOHP) in partnership with the Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy. SCOHP's mission is “to unite students across disciplines and the University in a collaborative effort to increase awareness and opportunities in health policy” (5).

In this piece, we describe our process for developing our student organization's structure and opportunities for engagement. Our model and lessons learned can be a resource for students and health policy experts at other universities to partner to create their own student-led organizations or enhance existing graduate student organizations' (e.g., AcademyHealth student chapters, medical student advocacy initiatives) reach or include the undergraduate population. It is critical that awareness and access to opportunities in health policy begin earlier in the pipeline of preparing future leaders in all the facets of health and health care.

Crafting a Student-Organization Structure

The Duke-Margolis Center for Health Policy was established in 2016. Undergraduate students recognized a gap in the Center's strategic plan and established a student advisory committee to assess needs and co-design extracurricular opportunities in health policy and management with Center leadership. As engagement increased, students recommended establishing a formal organization. SCOHP was subsequently launched after a planning period in the 2018–2019 academic year. To become an official university-recognized student organization and eligible for funding support, we applied to our university's student government in 2019 (e.g., written constitution, proof of student interest and faculty advisor). After receiving approval, we advertised SCOHP to the student body via email, social media, and targeted presentations in healthcare-related classes. Interested students were invited to apply to join our executive board and attend a kick-off meeting, where students participated in a series of brainstorming activities to share their own interests to guide future projects.

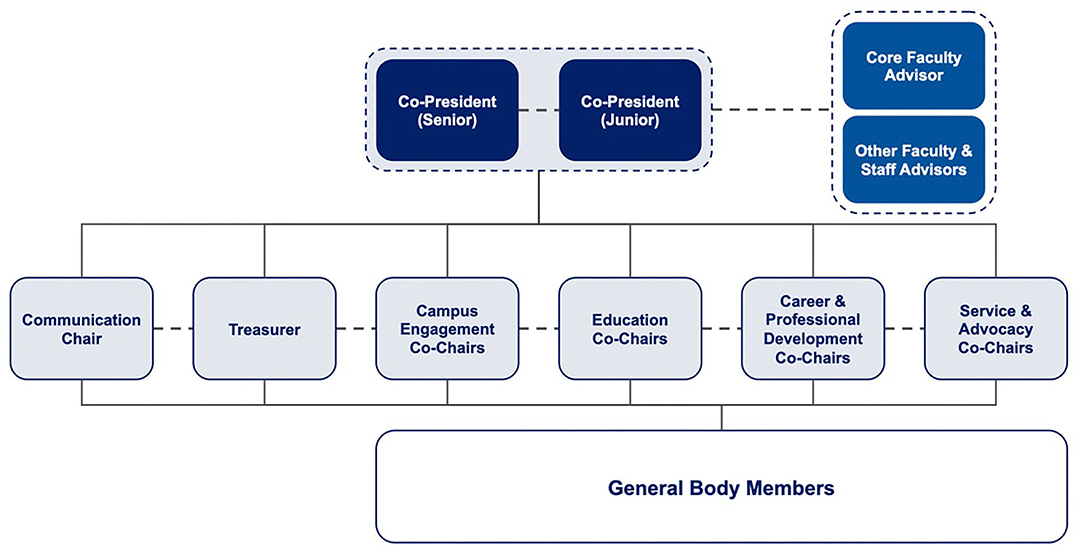

SCOHP's organizational structure establishes several levels of leadership and advising structured around SCOHP's strategic priorities: campus engagement, education, career and professional development, service and advocacy (Figure 1). Leading the organization are two co-presidents (a primary president and a secondary president), who oversee the executive board. The executive board meets biweekly and consists of the co-presidents, treasurer, communications director, and co-chairs of committees. Each committee is led by two co-chairs, meets weekly or bi-weekly with a broader group of general body members, and carries out a variety of educational and service activities. The entire general body meets monthly for each committee to share updates. The executive board also meets monthly with a faculty and staff advisory committee from the Duke-Margolis Center to identify opportunities for collaborative efforts between SCOHP, Duke-Margolis, and the local community.

Developing Opportunities for Student Engagement

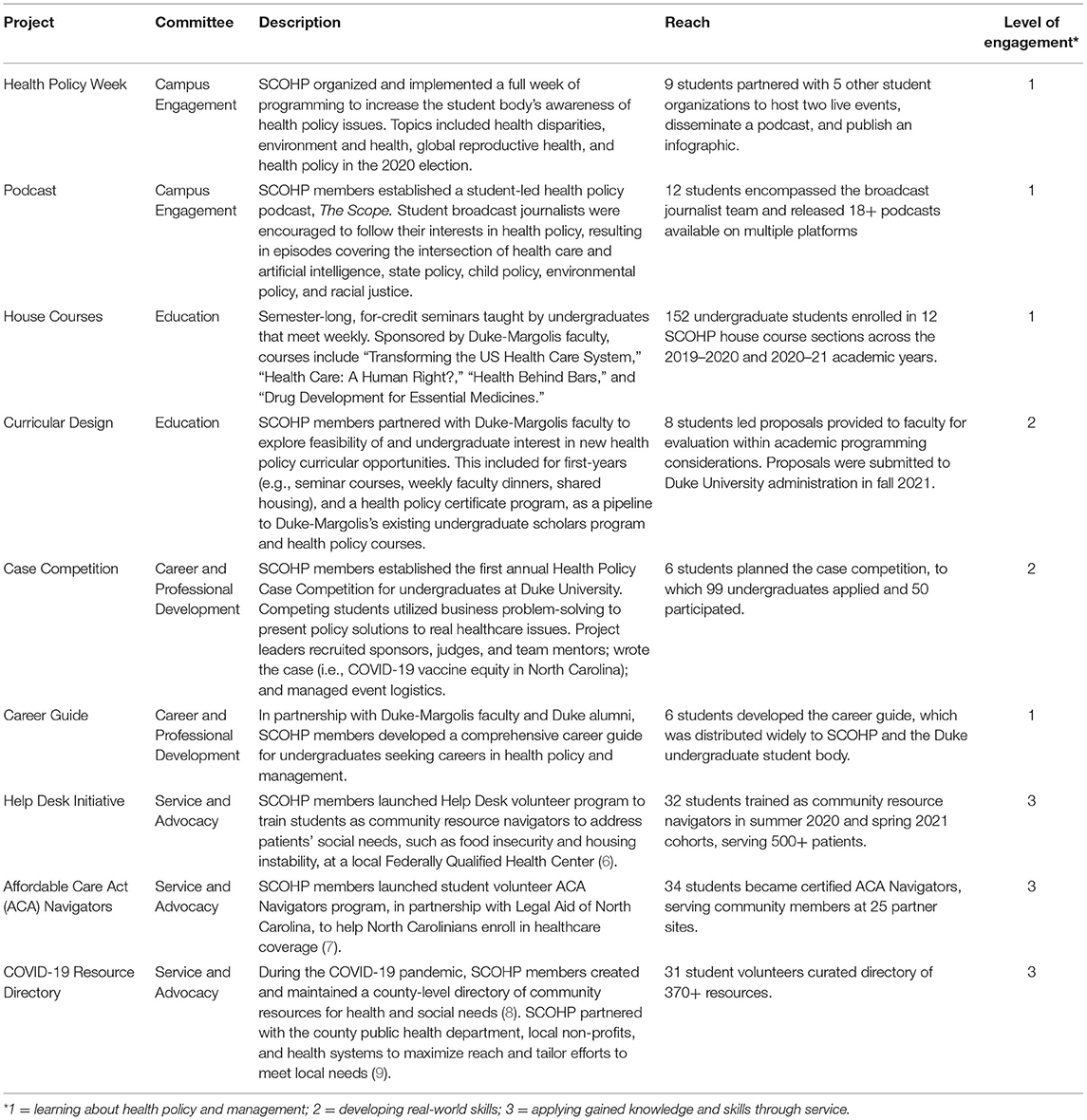

We organized SCOHP activities and projects into four committees, one for each of our four priorities (Table 1). Within each committee, we designed four levels of engagement to ensure students had different points of access based on their interests, time available, and personal or professional goals. The SCOHP committee levels of engagement are: (1) learning about health policy and management, (2) developing real-world skills, (3) applying gained knowledge and skills through service, and (4) leading their peers.

First, students interested in gaining exposure to health policy can participate in SCOHP's Health Policy Week (hosted by our campus engagement committee in the fall semester), in which undergraduates engage with a different healthcare topic each day through guest speakers, forum discussions, and online resources. For a longitudinal learning experience, undergraduates looking to learn the basics about healthcare delivery and reform can enroll in a semester-long, for-credit “House Course,” taught by members of our education committee under the mentorship of Duke-Margolis core and affiliate faculty. SCOHP organizes two to four House Courses each fall and spring semester and the registered students ranging from 7 to 18 per seminar meet once a week (online since spring 2020).

Second, students hoping to develop skills in health policy and management through experiential learning could compete in our annual case competition. Planned by our career and professional development committee, and sponsored by internal and external partner organizations, the case competition allows undergraduates to develop and pitch proposed solutions for real-world health challenges to a multi-sector panel of community member and faculty judges. Participating students also gain the opportunity to network with competition sponsors and explore opportunities to interview or intern with them.

Third, our service and advocacy committee provides students with the opportunity to apply knowledge and skills in health policy through service activities and academic-community partnerships. For example, in collaboration with a non-profit law firm, we recruited and trained students as Affordable Care Act Navigators to help community members enroll in health insurance (7).

Fourth, across all four committees and the executive board, students can develop leadership skills essential for successful careers in health policy and management. Students leading committees and projects learn to translate their ideas into action, organize and motivate their peers, and mentor the next generation of students to sustain their projects beyond their own SCOHP tenure. For example, in SCOHP's second year, students decided to launch a health policy and management podcast, “The Scope.” Students developed skills in outlining 20-min episodes and developing scripts, networking with subject matter experts, recording and editing podcasts, and creating handbooks to support their peers in leading their own episodes.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Adopting Our Model

Based upon our experience of developing and implementing the SCOHP model, we have learned three primary lessons that may be useful for students and health policy educators to consider when adopting our model or adapting specific elements to an existing context.

Leveraging Existing Faculty and University Support

Essential to SCOHP's launch was faculty and staff mentorship through the Duke-Margolis Center. Our mentors fostered SCOHP's growth by collaborating on programming and facilitating academic-community partnerships for service activities. For example, our mentors' expertise was instrumental to developing a health policy career guide that best reflected the diverse career paths in the field. Our mutually-beneficial partnership also enabled the Duke-Margolis Center to expand its presence among undergraduates and have a direct connection to a large body of students with whom to share research and education opportunities.

Transitioning from an advisory committee to an official student organization allowed us to access University funds to support events targeting undergraduates, such as Health Policy Week, and to increase recruitment through student organization activity fairs and websites. We also leveraged our status as an official student organization to partner with more well-established student organizations (e.g., consulting clubs, politics and policy groups, and departmental organizations) to increase reach of SCOHP's programming. Students from other institutions with limited access to University funds should consider utilizing external resources. For example, our policy case competition has external sponsors and the AcademyHealth student chapters can apply for mini-grants and discounted conference registrations (8). Across approaches, we encourage students and faculty to be transparent about their goals and identify projects with most potential for synergy.

Fostering a Tiered, Mentorship Model to Ensure Organization Sustainability

Maintaining an organization with 100+ members requires thoughtful mechanisms to ensure progress and sustainability. First, our committee structure allows committees to implement several projects simultaneously and independently. Nonetheless, regular check-ins with a broader general body and executive board still create a culture of accountability and peer support. We also learned that structuring primary and secondary co-positions for all leadership levels facilitates peer mentorship and smooth transfers of leadership as students graduate or explore other roles within SCOHP. When starting an undergraduate student organization, we recommended co-presidents and co-chairs represent different years and that founders include 1st and 2nd year students in their executive board. Such an approach, coupled with mechanisms for knowledge sharing and documentation (e.g., archiving meeting notes and organizational materials in a shared Google Drive, creating best practices one-pagers for programs) enables the organization to sustain and scale after the founding team graduates.

Allowing for Multiple Levels and New Forms of Student Engagement

In our experience, students join SCOHP with varying levels of interest in health policy and engagement in the student organization. Creating low-touch (e.g., attending speaker events during our Health Policy week) and high-touch (e.g., leading and coordinating our annual case competition) opportunities for engagement can allow students to tailor their participation to best meet their needs. Inviting students to initiate projects that forge connections between health policy and their own academic and professional interests (e.g., climate change, mental health, racial justice) has been crucial for retaining students. Additionally, faculty advisors can help students identify geographically relevant health policy projects. For example, many of our service projects relate to addressing health-related social needs, given North Carolina's recent push to integrate health and social services through Medicaid reform (10). Several research projects are connected with global health priorities. Regardless of how project ideas are sourced, we recommended club leadership consider how to produce “value-add” initiatives that do not duplicate existing curricular or extra-curricular offerings.

Conclusion

Our experience with SCOHP provides a model for undergraduate student engagement in health policy and management that other universities can replicate and adapt in their local contexts and for students at any or all learning levels. We encourage students and educators to consider partnering to create meaningful opportunities to inspire the next generation of health care and health policy leaders.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

CT, SS, and JL drafted the manuscript. GS and JP revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and all authors approved of the version of the manuscript to be published. All authors were involved in the conception and implementation of the project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sarah Dunn Phillips and the SCOHP executive board members from 2019 to 2021 for their contributions to the development of this model. We look forward to collaborating with other institutions to expand opportunities nationwide.

References

1. Tarasenko YN, Lee JM. U.S. Undergraduate education in public health: hot or not? Front Public Health. (2015) 3:71. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00071

2. Smith LJ, Chenoweth JD. The contributions of student organization involvement to students' self-assessments of their leadership traits and relational behaviors. Am J Bus Educ. (2015) 8:279–88. doi: 10.19030/ajbe.v8i4.9422

3. Zeeman JM, Bush AA, Cox WC, Buhlinger K, McLaughlin JE. Identifying and mapping skill development opportunities through pharmacy student organization involvement. AJPE. (2019) 83:6950. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6950

4. Soria K, Troisi J, Stebleton M. Reaching out, connecting within: community service and sense of belonging among college students. High Educ Rev. (2012). 9:65–8.

5. Duke Student Collaborative on Health Policy. https://sites.duke.edu/dukescohp/ (accessed June 5, 2021)

6. Sandhu S, Xu J, Blanchard L, et al. A community resource navigator model: utilizing student volunteers to integrate health and social care in a community health center setting. Int J Integr Care. (2021) 21:2. doi: 10.5334/ijic.5501

7. Hallur S, Sandhu S, Herold E. Embedding student volunteer affordable care act navigators in a primary care clinic. Ann Fam Med. (2022). doi: 10.1370/afm.2794. [Epub ahead of print].

8. Student Chapter Mini Grants. AcademyHealth. https://academyhealth.org/page/student-chapter-mini-grants (accessed December 31, 2021).

9. Sandhu S, Lemmon ME, Eisenson H, Crowder C, Bettger JP. Addressing the social determinants of health during the COVID-19 pandemic: ensuring equity, quality, and sustainability. Fam Community Health. (2021) 44:78–80. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000290

Keywords: education, undergraduate (MeSH), health policy, healthcare, management-healthcare, student organization

Citation: Thomas C, Sandhu S, Li J, Sanders GD and Prvu Bettger J (2022) Developing the Next Generation of Leaders in Health Policy and Management: Lessons From an Undergraduate Student-Led Organization. Front. Public Health 10:855712. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.855712

Received: 15 January 2022; Accepted: 24 February 2022;

Published: 18 March 2022.

Edited by:

Andrew Harver, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher Mierow Maylahn, New York State Department of Health, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Thomas, Sandhu, Li, Sanders and Prvu Bettger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sahil Sandhu, c2FoaWxzYW5kaHVAaG1zLmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

Charlotte Thomas1

Charlotte Thomas1 Sahil Sandhu

Sahil Sandhu Janet Prvu Bettger

Janet Prvu Bettger