- 1College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Samara University, Samara, Ethiopia

- 2Dream Science and Technology College, Dessie, Ethiopia

- 3Department of Malaria and NTD, Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 4College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia

Background: Studies conducted on the practice of COVID-19 preventive methods across the world are highly inconsistent and inconclusive. Hence, this study intended to estimate the pooled preventive practice and its determinants among the general population.

Methods: This study was conducted using online databases (PubMed, HINARI, Scopus, EMBASE, Science Direct, and Cochrane library database), African Journals online, Google Scholar, open gray and online repository accessed studies. The quality of the included studies was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS). STATA 14.0 software for analysis. The existence of heterogeneity between studies was checked using Cochran Q test and I2 test statistics and then, the presence of publication bias was detected using both funnel plot and Egger's test.

Results: 51 studies were included and the pooled level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 was 74.4% (95% CI: 70.2–78.6%, I2 = 99.7%, P < 0.001] using a random effects model. Being female [OR = 1.97: 95% CI 1.75, 2.23; I2 = 0.0%, P < 0.698], rural residence [OR = 0.53: 95% CI 0.44, 0.65; I2 = 73.5%, P < 0.013], attending higher education level [OR = 1.47: 95% CI 1.18, 1.83; I2 = 75.4%, P < 0.001], being employed [OR = 2.12: 95% CI 1.44, 3.12; I2 = 91.8%, P < 0.001], age < 30 [OR = 0.73: 95% CI 0.60, 0.89; I2 = 73.9%, P < 0.001], and knowledgeable [OR = 1.22: 95% CI 1.09, 1.36; I2 = 47.3%, P < 0.077] were the independent predictors of adequate practice level.

Conclusions: nearly three-fourths of the general population has an adequate preventive practice level toward COVID-19. Thus, the global, regional, national, and local governments need to establish policies and strategies to address the identified factors.

Background

Severe acute respiratory infection (SARS) is a group of respiratory tract infections caused by a beta coronavirus (SARS-COV2) (1–3). Corona Virus Disease-2019 (“COVID-19”) is a family of SARS caused by Novel Coronavirus and was first detected in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. Since, the World Health Organization (WHO) has declared it as a pandemic; the virus has been distributed rapidly across the world and it causes high mortality and morbidity (2–5). Globally, there is an estimated 32. million cases and nearly a million (991, 705) deaths at the end of September 2020 (6). As a result, nations across the globe have taken different preventive measures. These include movement restrictions, mask-wearing, hand washing, confinement at home, closure of schools, and other social services (7–9). Hence, appropriate knowledge, attitudes, and practices on preventive measures are mandatory to halt the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak in countries (10, 11). However, studies revealed that the communities have shown still poor knowledge and negative attitude toward the preventive measures of COVID pandemic (12, 13). Besides, studies conducted across the globe have been investigating the knowledge, attitude, and practices on preventive measures of COVID-19 pandemic predominantly focused on health care workers and patients (14–16). However, the studies conducted to date were highly variable and inconsistent to generate evidence regarding the determinants of preventive practice of the general population toward COVID-19. Therefore, this study intended to determine the pooled practice level and its determinants toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 among the general population.

Methods and Materials

We have used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA-2009) (17) to screen the included studies and PRISMA-P 2009 statements to report the findings (Additional File 1) (18).

Search Strategy

Different online databases (PubMed, HINARI, Scopus, EMBASE, Science direct, Cochrane library database, and African Journals online), Google Scholar, other open gray literatures, and online university repositories were retrieved to include articles conducted on preventive practice toward COVID-19. We have developed different Boolean operators to have comprehensive datasets on preventive practice toward COVID-19. Search MeSH terms: Wuhan coronavirus” OR “COVID-19” OR “novel coronavirus” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “coronavirus disease” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “SARS2” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2” AND “preventive practice” OR “practice” AND “associated factors” OR “risk factors” OR “determinants”) [Additional file 2]. This study involved studies conducted across the globe to assess the level of practice toward preventive measures of COVID-19 among the adult population.

Eligibility Criteria to Include Studies

In this systematic review, all observational studies (i.e., cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort), studies reported the level of preventive practice toward COVID-19 and its determinants, and studies published in English language were eligible for this study. Besides, it also included all studies involving the adult population without restriction on the year of publication. However, we excluded studies other than observational studies (case reports, conference reports, and expert opinions) and the studies did not undergo a peer review process.

Outcome Measurement

This study had two main outcomes. The first outcome was to determine the pooled level of practice toward preventive measures of COVID-19 among the general population. In this study, the adequate practice level was measured by including studies that were correctly classified the level of practice using the median (50%) score or above. Then, the pooled estimate of preventive practice was calculated by dividing the number of population with adequate practice by the total sample size multiplied by 100. The second outcome of the study was to identify determinants of preventive practice using the pooled odds ratio with the corresponding 95% confidence interval.

Note: in this study, the general population is defined as all population other than health care professionals who are assumed to have better knowledge and practice toward COVID-19 compared to the general population.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We had collected the findings of all online databases and eligible articles and it was exported to Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet. Two authors (AWT and SB) extracted the data and reviewed all screened articles. The quality of the included articles was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for observational studies (i.e., cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort) was employed (19, 20). The studies with NOS scores of six or more were considered a “good” quality study (low risk) while studies scored less than six were considered as “poor” quality study (high risk) (20) [Additional File 3]. However, all retrieved articles had a score of six or more NOS scores.

Data Analysis

The extracted data were entered into a Microsoft Excel Database and then it was imported into STATA version 14.0 software with meta-analysis package for further analysis. We had performed a narrative description of the study population, the studies included, the risk factors identified, and the determinants of preventive practice toward COVID-19. The pooled estimate of the level of preventive practice toward COVID-19 was calculated using the random-effects models (21) at 95% confidence intervals. Moreover, the pooled odds ratios were determined with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for its determinants.

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

The Cochran's-Q statistic and I2 statistic tests with the corresponding p-values (22) were used to determine the existence of heterogeneity between studies. In this study, a value of I2 25, 50, and 75% were used to declare the heterogeneity test as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (22). As a result, we had conducted subgroup analyses, meta-regression, and sensitivity analysis to handle the heterogeneity.

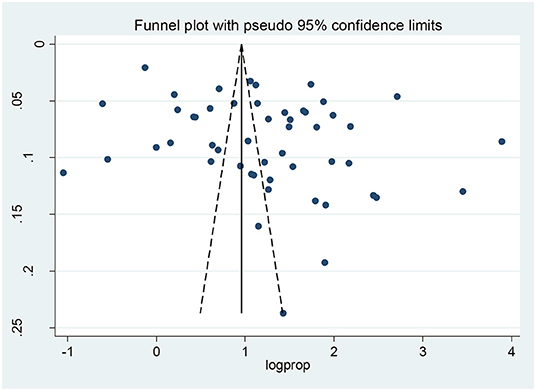

Publication bias was examined by visual inspection of funnel plots (23) and Egger's test (24). Hence, a p-value of < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistically significant publication bias.

Results

Description of the Included Studies

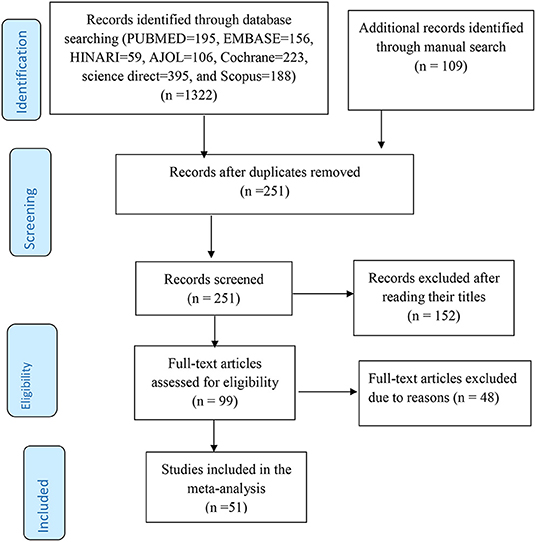

In this review, 1,431 studies were retrieved from international databases, African Journals, online, Google Scholar, open gray, and online repositories. The accessed articles were focused on the level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 and its determinants among the general population. Furthermore, extended references were reached from the published articles. All of he retrieved articles were exported into endnote X8 reference managers and 1,180 articles were removed due to duplication and 152 articles were excluded after review of their titles and abstracts. Therefore, 99 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 48 articles were also excluded due to different reasons (i.e., abstracts, case-reports, conference reports, language, and experimental studies). Finally, 51 studies were met the inclusion criteria to undergo the final systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure 1). In this review study, 88,255 study participants were included from 51 observational studies conducted across the world.

Figure 1. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow chart to screen the studies to be included in the review.

The Pooled Level of Practice Toward the COVID-19 Preventive Measures

The level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 varies from country to country. In this study, 51 observational studies conducted across the world were included to estimate the level of practice toward preventive measures of COVID-19 among the general population (13, 25–74). Thus, the overall pooled level of adequate practice level toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 was 74.4% (95% CI: 70.2–78.6%, I2 = 99.7%, P < 0.001) using a random effects model [Additional File 4].

Subgroup Analysis

Different techniques were applied to handle the high level of heterogeneity between the included studies. These include using random effects model, subgroup analysis, meta-regression, and sensitivity analysis.

In this study, subgroup analysis was done based on the region category (i.e., low-income, middle-income, and high-income) of the countries where the included studies were conducted and sample size category (i.e., sample size <380 and sample size ≥380). As a result, the pooled level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries was 69.0% [95% CI 62–76: I2 = 99.1%, p < 0.001), 81.0% (95% CI 75.0–87.0: I2 = 99.4%, p < 0.001), and 78.0% (95% CI 70–86: I2 = 99.8%, p < 0.001) respectively [Additional File 5]. Regarding sample size, the pooled level of practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19 was 81.0% (95%CI 75.1–86.0: I2 =75.5%, P < 0.01) and 74.0% (95%CI 70.0–78.0: I2 = 99.7%, P < 0.001) among studies involving fewer than 380 and 380 or more study participants, respectively [Additional File 6].

Publication Bias

To identify the presence of publication bias, both a funnel plot and Egger's test were performed. Visual inspection of the funnel plot showed an asymmetrical distribution, which indicated the presence of publication bias (Figure 2). The finding of publication bias was confirmed following the Egger's test (p <0.013).

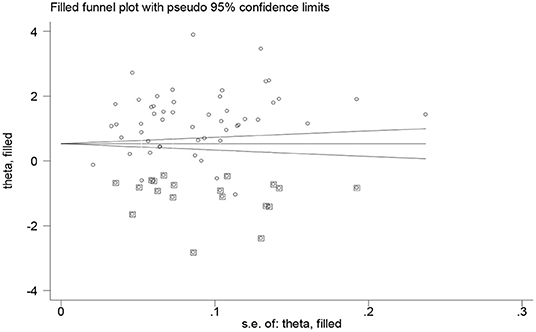

Trim and Fill Analysis

In this review, the authors confirmed that the presence of significant publication bias that may be subjected to unpublished small studies. Thus, to handle this problem, the authors did trim and fill analysis and 19 studies were filled (Figure 3).

Sensitivity Analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of any individual study on the pooled effect size. However, the sensitivity analysis done using a random effects model revealed that no single study affected the overall level of practice with the preventive measures of COVID-19 (Additional File 7).

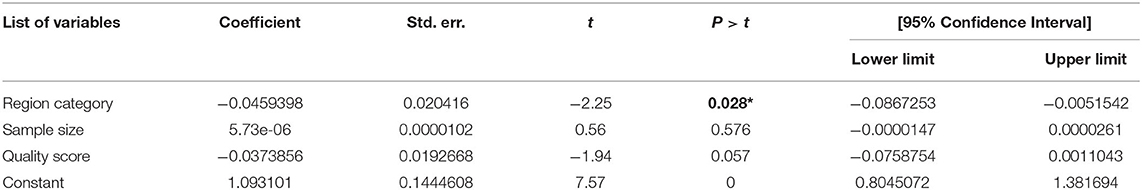

Meta-Regression Analysis

To investigate the possible source(s) of variation across the included studies, we performed meta-regression analysis using region (high, middle, and low-income), sample size, and quality of the score as covariates of interest. Thus, the results of this meta-regression analysis showed that region category was significantly associated with the presence of heterogeneity (p <0.028) (Table 1).

Factors Associated With the Level of Practice Toward COVID-19 Prevention

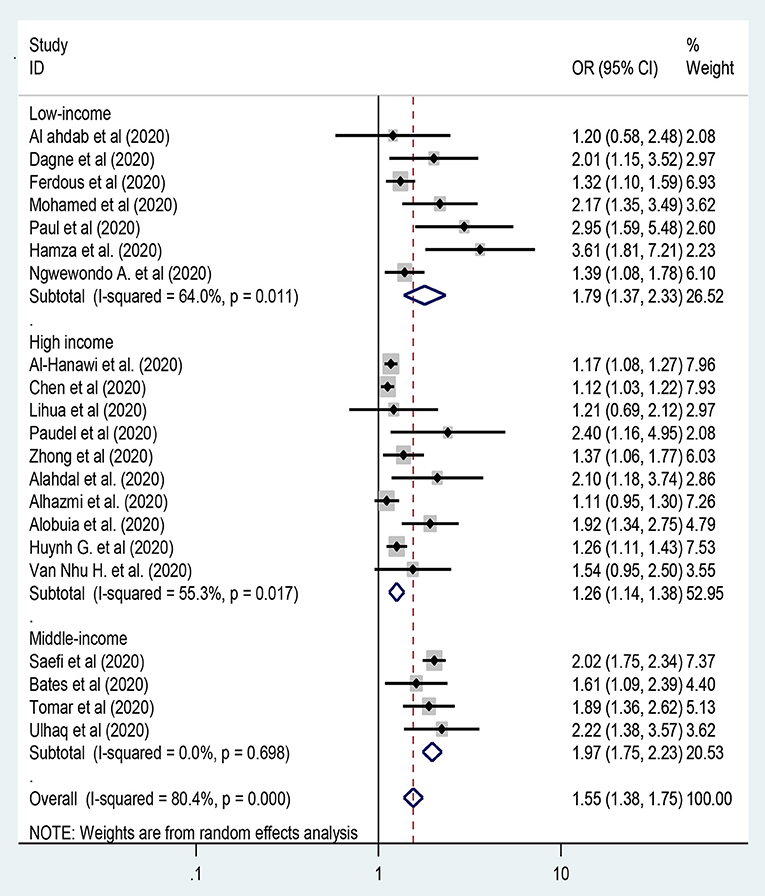

Sex of the Participants

In this meta-analysis, twenty-one studies were included to assess the association between sex of the participants and preventive practice toward COVID-19 (13, 27, 28, 33, 34, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45, 50–56, 60, 65, 67, 73). Hence, female participants in middle-income countries were twice more likely to have adequate practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19 [OR = 1.97: 95% CI 1.75, 2.23: I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.698] compared to male participants (Figure 4). In this meta-analysis, there was heterogeneity between the included studies while we applied random-effects model and then subgroup analysis by region was done to handle the variation between studies.

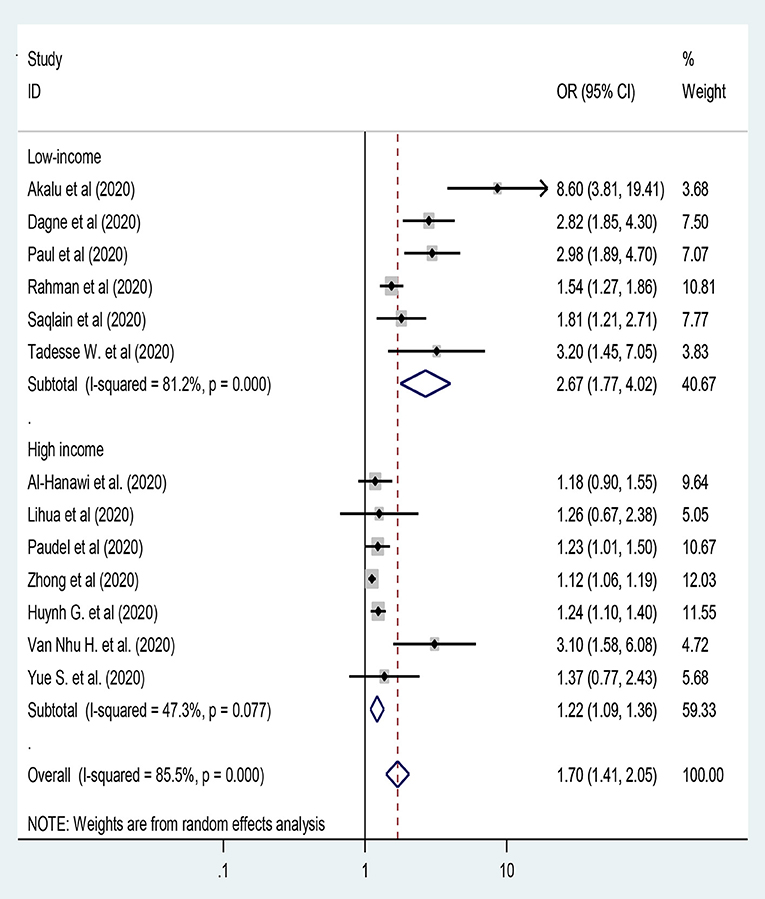

Knowledge Level as A Factor of Preventive Practice Toward COVID-19

In this study, thirteen studies were included to assess knowledge level as a predictor of practice of preventive measures toward COVID-19 (26, 28, 34, 37, 41, 42, 44, 46, 49, 53, 65, 73, 74) by using random-effect model analysis. However, still we were unable to handle the heterogeneity between studies [I2 = 86.2%, P < 0.001]. Hence, subgroup analysis was done using country development category [i.e., low-and high-income]. Hence, participants from high-income countries and with adequate knowledge had 22% more likely to have adequate practice toward COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 1.22: 95% CI 1.09, 1.36; I2 = 47.3%, P = 0.077] (Figure 5).

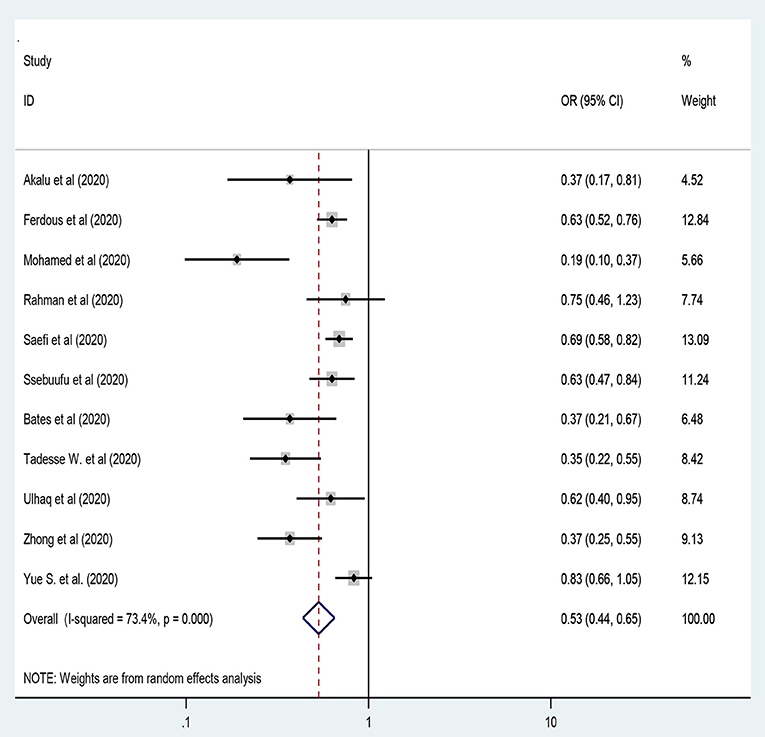

Residence Areas and Practice of the COVID-19 Preventive Measures

Eleven studies were included to assess residence in rural areas as a negative predictor of adequate practice of preventive measures toward COVID-19 (13, 26, 39, 44, 45, 48, 49, 51–53, 74) by using a random-effect model that was applied to handle the variation between studies [I2 = 71.8%, P < 0.001]. Hence, people living in rural areas had 47% less likely to have adequate practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 0.53: 95% CI 0.44, 0.65; I2 = 73.5%, P < 0.001] [Figure 6].

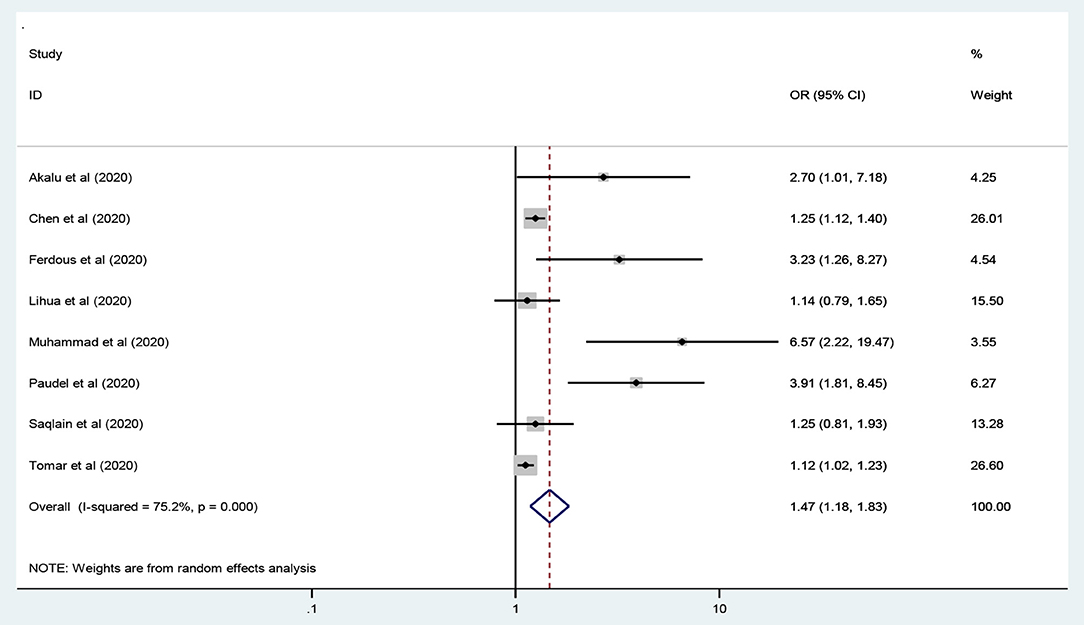

Education Level and Practice of the COVID-19 Preventive Measures

Seven studies were included to assess education level as an independent predictor of level of practice toward COVID-19 the preventive measures (13, 26, 33, 37, 41, 46, 50). The meta-analysis results revealed that participants who had attended higher education levels were 47% more likely to practice preventive measures toward COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 1.47: 95% CI 1.18, 1.83: I2 = 75.4%, P < 0.001]. We applied random-effects model to handle the variation between studies (Figure 7).

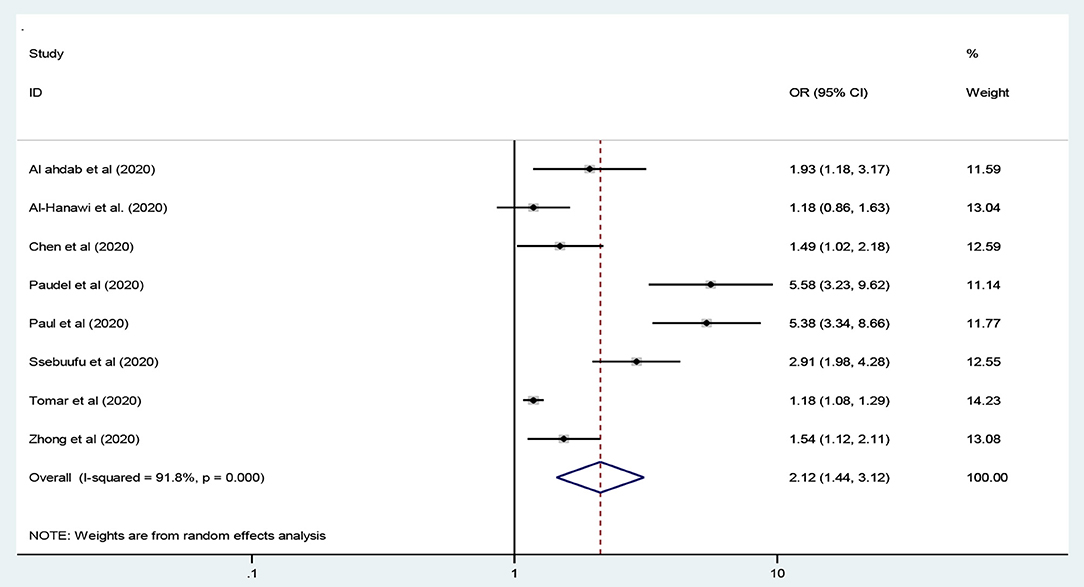

Employment Status and Practice of the COVID-19 Preventive Measures

In this study, eight studies were included to assess being employed as a predictor of adequate practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 globe (27, 28, 33, 41, 42, 48, 50, 53). As a result, employed participants had twice higher odds of adequate practice compared to unemployed participants [OR = 2.12: 95% CI 1.44, 3.12, I2 = 91.2%, P < 0.001] using a random-effects model analysis (Figure 8).

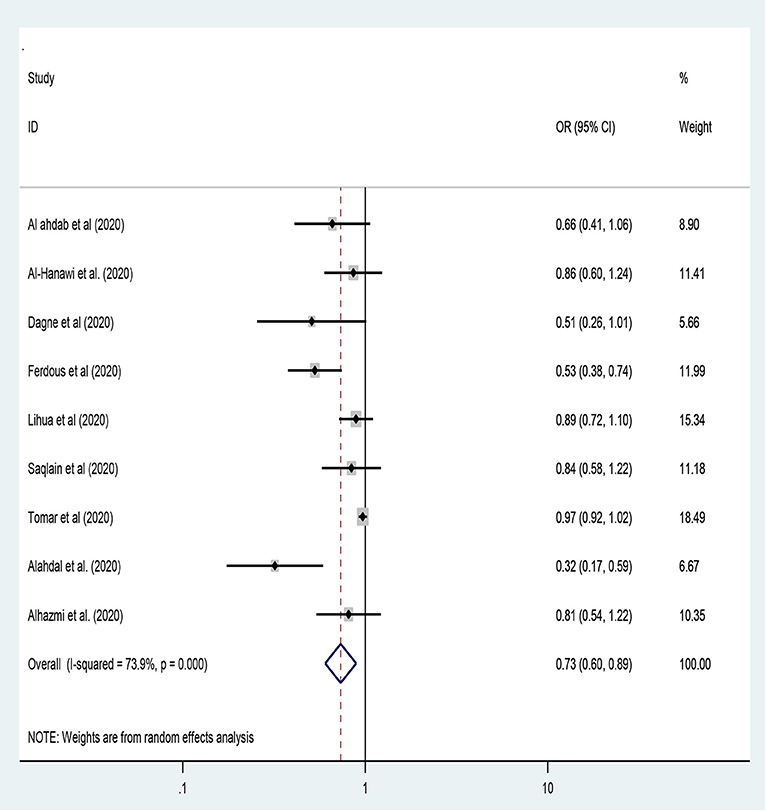

Age of the Participants and Practice of the COVID-19 Preventive Measures

In this study, nine studies were included to assess the association between the age of the participants and the level of practice of preventive measures toward COVID-19 (13, 27, 28, 34, 37, 46, 50, 54, 55). Hence, young age [<30 years of age] participants had 27% lower odds of adequate practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 0.73: 95% CI 0.60, 0.89, I2 = 73.9%, P < 0.001]. Besides, the random-effect model was employed to handle the heterogeneity between studies [Figure 9].

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, 51 observational studies were retrieved across the world focusing on the level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 and its determinants. In this review, the overall pooled level of adequate practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19 was 74.4% [95% CI: 70.2–78.6%] that was done using a random effects model. This finding is lower than studies conducted Pakistan (80.5%) (46), Sudan (89.9%) (39), Shaanxi Province, China (87.9%) (75), Uganda (85.3%) (48). However, this finding is higher than studies conducted in Ethiopia (26.1 to 72.5%) (26, 34, 49, 76), Bangladesh (55.1%) (13), and Pakistan (57.3%) (15). The differences in the practice of preventive measures could have been subjected to variation in the cut-off values to classify good or poor practices. For instance, most of the previous studies have been used the score of 80% and above to classify adequate practice, while the current study was classified based on the median score (50% or more), to consider studies with a good level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19. In addition, the discrepancies might be due to differences in sample size, in which the current study involved a large sample sizes. Therefore, further investigation should be done to identify the main reasons for this variation across the regions.

On the other hand, the subgroup analysis indicated that the pooled level of practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries was 69, 81, and 78%, respectively. This indicated that substantial heterogeneity of the level of preventive practice across countries. Such differences might be subject to low adherence of preventive practice toward COVID-19 in low-income countries. The other reason for the lower prevalence in these regions might be due to more studies were included in the review process.

This study revealed that females from middle-income countries had twice higher odds of adequate practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19 [OR = 1.97] compared to male participants, which was similar to the findings of studies conducted across the world (13, 27, 28, 33, 34, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45, 50–56, 60, 65, 67, 73). In most of the countries, females are more responsible to take care than the family members. Besides, females are more likely to obey the regulations and rules of the government so that they are more likely to adhere the practice of preventive measures toward COVID-19 compared to males.

In this study, knowledge level was the independent predictor of adequate practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19. Hence, the subgroup analysis showed that participants from high-income countries and with adequate knowledge had 22% more likely to have adequate practice toward COVID-19 [OR = 1.22] compared to their counterparts. Evidences across the world revealed that (26, 28, 34, 37, 41, 42, 44, 46, 49, 53, 73, 74) adequate knowledge level positively correlated with adequate practice scores toward the preventive measures of COVID-19.

The meta-analysis results revealed that participants who had attended higher education levels were 47% more likely to have adequate practice toward the preventive measures COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 1.47]. Evidences of several studies conducted in different countries 19 (13, 26, 33, 37, 41, 46, 50) supported this finding. When the education level of the participants increases, they will have good knowledge regarding the preventive measures of COVID-19. This in terms improves the practice of the participants on preventive measures upon COVID-19.

In this study, the subgroup analysis by region category pointed out that participants from middle-income countries and those living in rural areas had 47% less likely to have adequate practice toward preventive measures of COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 0.53]. This finding is similar to the findings from different studies conducted in several countries (13, 26, 39, 44, 45, 48, 49, 51–53, 74). In most countries, people living in rural settings are not accessible to the preventive measures provided by the government so that they are less likely to practice the preventive measures of the COVID-19 compared to people in urban settings.

This study indicated that the odds of adequate practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 was twice higher among employed participants compared to unemployed participants [OR= 2.12]. This finding is similar to studies conducted across the globe (27, 28, 33, 41, 42, 48, 50, 53). Employed individuals have the chance to be exposed to preventive measures since the employers safeguard their employees to be free of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, employed people are more likely to have adequate practice on the preventive measures of COVID-19 compared to non-employed individuals.

Worldwide, studies revealed that people under 30 years of age are less likely to be adhered to the preventive practice of COVID-19 (13, 27, 28, 34, 37, 46, 50, 54, 55). In our study, young age (<30 years of age) participants had 27% lower odds of adequate practice toward the preventive measures of COVID-19 compared to their counterparts [OR = 0.73]. In adulthood, people are less likely to adhere to the preventive measures recommended by the government so that they will have less compliance with practice of the COVID-19 preventive measures.

Limitations of the Study

The first limitation of the study was only English articles or reports were considered to carry out the analysis. Even though the quality of each study was assessed by using The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, inter-author bias might be occurred with the leveling of the scale of each article. Reviewing of different characteristics of the involved cases with different sampling methods was also the other limitation of this study.

Conclusions

In this review, nearly three-fourths of the participants worldwide had a pooled levels of adequate practice toward COVID-19. Being female, rural residence, higher education level, being employed, age <30, and above median knowledge score were independent predictors of preventive practice toward COVID-19. Thus, the national and local governments should develop effective and inclusive prevention strategies to address students who are at home due to COVID-19 pandemic.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: we will provide the dataset based on request when necessary. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to YWJheXdvbmRheUBzdS5lZHU=.

Author Contributions

AWT, SBA, KUM, SMT, and GB have conceived the title, write the significance of the study, generate the research questions, and write the methods section. AWT and SBA have done the data extraction and quality assessment. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Samara University librarian and ICT complex staffs for availing an uninterrupted internet connection. We also acknowledge the open access online database publishers.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.844692/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

OR, Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; COVID 19, Corona Virus Diseases 19; FMOH, Federal Ministry of Health; PRISMA-2009, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-analyses; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

1. Skowronski DM, Astell C, Brunham RC, Low DE, Petric M, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a year in review. Annu Rev Med. (2005) 56:357–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.091103.134135

2. Wu D, Wu T, Liu Q, Yang Z. The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: what we know. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.004

3. Zumla A, Hui DS, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. (2015) 386:995–1007. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60454-8

4. Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown Etiology in Wuhan China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:401–2. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678

5. CDC for disease Prevention: people who are at higher risk for severe illness. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020 (accessed April 5, 2020).

6. WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 201. Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports-131.2020

7. Burke RM. Active monitoring of persons exposed to patients with confirmed COVID-19—United States, January–February 2020. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2020, 69. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6909e1

8. Zettler I, Schild C, Lilleholt L, Böhm R. Individual differences in accepting personal restrictions to fight the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a Danish adult sample. PsyArXiv [Preprint]. (2020).

9. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. (2020). doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702

10. Hu W, Su L, Qiao J, Zhu J, Zhou Y. Countrywide quarantine only mildly increased anxiety level during COVID-19 outbreak in China. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.01.20041186

11. Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, Xiang Y-T, Liu Z, Hu S, et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e17–8. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8

12. Li S, Wang Y, Xue J, Zhao N, Zhu T. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active Weibo users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2032. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062032

13. Ferdous MZ, Islam MS, Sikder MT, Mosaddek AS, Zegarra-Valdivia JA, Gozal D. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: An online-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE (2020) 15:e0239254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239254

14. Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, Wang Y, Nie H, Zhang L, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hospital Infect. (2020) 105:183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.012

15. Muhammad K, Saqlain M, Hamdard A, Naveed M, Umer MF, Khan S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of community pharmacists about COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey in two provinces of Pakistan. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.05.22.20108290

16. Olum R, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR, Bongomin F. Coronavirus Disease-2019: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of health care workers at Makerere university teaching hospitals, Uganda. Front Pub Health. (2020) 8:181. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00181

17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj. (2009) 339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

18. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ: Br Med J. (2015) 349:g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647

19. Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell PJ. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (2011). p. 1–2.

20. McPheeters ML, Kripalani S, Peterson NB, Idowu RT, Jerome RN, Potter SA, et al. Closing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science (vol. 3: quality improvement interventions to address health disparities). Evid Rep Technol Access (Full Rep). (2012) 1–475.

21. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis of clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. (1986) 7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

22. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

23. Liu JL. The role of the funnel plot in detecting publication and related biases in meta-analysis. Evid Based Dent. (2011) 12:121–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400831

24. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis is detected by a simple graphical test. Bmj. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

25. Adesegun OA, Binuyo T, Adeyemi O, Ehioghae O, Rabor DF, Amusan O, et al. The COVID-19 crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Nigerian public. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2020) 107:1997. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0461

26. Akalu Y, Ayelign B, Molla MD. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards COVID-19 among chronic disease patients at Addis Zemen hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. (2020) 13:1949–60. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S258736

27. Al Ahdab S. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards pandemic COVID-19 among Syrians. Res Square [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-27859/v1

28. Al-Hanawi M, Angawi K, Alshareef N, Qattan A, Helmy H, Abudawood Y, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among the public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public health. (2020) 8:217. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00217

29. Ali M, Uddin Z, Banik PC, Hegazy FA, Zaman S, Ambia AS, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and fear of COVID-19: An online-based cross-cultural study. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00638-4. [Epub ahead of print].

30. Anikwe CC, Ogah CO, Anikwe IH, Okorochukwu BC, Ikeoha CC. Coronavirus disease 2019: knowledge, attitude, and practice of pregnant women in a tertiary hospital in Abakaliki, southeast Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obst. (2020) 151:197–202. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13293

31. Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sern TJ, Ayub SH, Mohamad E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0233668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233668

32. Byanaku A, Ibrahim M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards COVID-19: a quick online cross-sectional survey among Tanzanian residents. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020).

33. Chen X, Ran L, Liu Q, Hu Q, Du X, Tan X. Hand hygiene, mask-wearing behaviors and its associated factors during the COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional study among primary school students in Wuhan, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2893. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082893

34. Dagne H, Alemu KA, Dagnew B, Taddesse D, Alemayehu AM, Andualem Z, et al. Prevention practice and associated factors of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak among educated ethiopians: an online based cross-sectional survey. Res Square [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-34504/v1

35. Joshi K, Jamadar D. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding COVID-19 among medical students-A cross sectional study. Int J Adv Community Med. (2020) 3:1–5. doi: 10.33545/comed..v.i.142

36. Lau LL, Hung N, Go DJ, Ferma J, Choi M, Dodd W, Wei X: Knowledge attitudes attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the Philippines: a cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. (2020) 10:7. doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.011007

37. Lihua M, Ma L, Liu H, Jiang N, Wang S, Jiang X. Knowledge, beliefs/attitudes and practices of rural residents in the prevention and control of COVID-19: an online questionnaire survey. Res Square [Preprint]. (2020) 1–12. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-22257/v1

38. Maheshwari S, Gupta PK, Sinha R, Rawat P. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among medical students: a cross-sectional study. J Acute Disease. (2020) 9:100. doi: 10.4103/2221-6189.283886

39. Mohamed A, Elhassan E, Mohamed AO, Mohammed AA, Mahgoop MA, Sharif ME, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of the Sudanese people towards COVID-19: an online survey. Res Square [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-32375/v1

40. Naser AY, Dahmash EZ, Alwafi H, Alsairafi ZK, Al Rajeh AM, Alhartani YJ, et al. Knowledge and practices towards COVID-19 during its outbreak: a multinational cross-sectional study. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.13.20063560

41. Paudel S Shrestha P Karmacharya I Pathak OK: Knowledge attitude and practices (KAP) towards COVID-19 among Nepalese residents during the COVID-19 outbreak: an online cross-sectional study. Res Square [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-31044/v1

42. Paul A, Sikdar D, Hossain MM, Amin MR, Deeba F, Mahanta J, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards novel corona virus among bangladeshi people: implications for mitigation measures. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20091181

43. Peng Y, Pei C, Zheng Y, Wang J, Zhang K, Zheng Z, et al. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice associated with COVID-19 among undergraduate students in China. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09392-z

44. Rahman A, Sathi NJ. Knowledge, attitude, and preventive practices toward COVID-19 among Bangladeshi internet users. Elect J General Med. (2020) 17:8223. doi: 10.29333/ejgm/8223

45. Saefi M, Fauzi A, Kristiana E, Adi WC, Muchson M, Setiawan ME, et al. Survey data of COVID-19-related knowledge, attitude, and practices among Indonesian undergraduate students. Data in Brief. (2020) 51:105855. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105855

46. Saqlain M, Ahmed A, Nabi I, Gulzar A, Naz S, Munir MM, et al. Public knowledge and practices regarding coronavirus disease 2019: a cross-sectional survey from Pakistan. Front. Public Health (2021) 9:629015. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.629015

47. Sima R, Mariam I, Aisha B: Knowledge attitudes and practices (KAP) towards COVID-19: A quick online cross-sectional survey among Tanzanian residents. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020).

48. Ssebuufu R, Sikakulya F, Binezero SM, Wasingya L, Nganza SK, Ibrahim B, et al. Awareness, knowledge, attitude and practice towards measures for prevention of the spread of COVID-19 in the Ugandans: a nationwide online cross-sectional survey. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20092247

49. Tadesse AW, Abebe NM, Tadesse SE, Wube MC, Abate AA. Preventive practice and associated factors towards COVID-19 among college students in Amhara region, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Ethiopian J Health Sci. (2021) 31:3–14. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v31i1.2

50. Tomar BS, Singh P, Nathiya D, Suman S, Raj P, Tripathi S, et al. Indian communitys knowledge, attitude, & practice towards COVID-19. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20092122

51. Bates BR, Moncayo AL, Costales JA, Herrera-Cespedes CA, Grijalva MJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among ecuadorians during the outbreak: an online cross-sectional survey. J Comm Health. (2020) 9:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00916-7

52. Ulhaq ZS, Kristanti RA, Hidayatullah AA, Rachma LN, Susanti N, Aulanni'am A. Data on attitudes, religious perspectives, and practices towards COVID-19 among Indonesian residents: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Data Brief. (2020) 32:106277. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106277

53. Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1745. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221

54. Alahdal H, Basingab F, Alotaibi R. An analytical study on the awareness, attitude and practice during the COVID-19 pandemic in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. (2020) 13:1446–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.015

55. Alhazmi A, Ali MHM, Mohieldin A, Aziz F, Osman OB, Ahmed WA. Knowledge, attitudes and practices among people in Saudi Arabia regarding COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. J Public health Res. (2020) 9:1867. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2020.1867

56. Alobuia WM, Dalva-Baird NP, Forrester JD, Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J, Kebebew E. Racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID-19 in the USA. J Pub Health. (2020) 42:470–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa069

57. Chan EYY, Huang Z, Lo ESK, Hung KKC, Wong ELY, Wong SYS. Sociodemographic predictors of health risk perception, attitude and behavior practices associated with health-emergency disaster risk management for biological Hazards: the case of COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong, SAR China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3869. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113869

58. Dkhar SA, Quansar R, Saleem SM, Khan SMS. Knowledge, attitude, and practices related to COVID-19 pandemic among social media users in J&K, India. Indian J Public Health. (2020) 64(Supplement):S205–10. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_469_20

59. Domiati S, Itani M, Itani G. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of the lebanese community toward COVID-19. Front Med. (2020) 7:542. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00542

60. Hamza MS, Badary OA, Elmazar MM. Cross-sectional study on awareness and knowledge of COVID-19 among senior pharmacy students. J Comm Health. (2020) 3:1-8. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-33352/v1

61. Honarvar B, Lankarani KB, Kharmandar A, Shaygani F, Zahedroozgar M, Rahmanian Haghighi MR, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, risk perceptions, and practices of adults toward COVID-19: a population and field-based study from Iran. Int J Public Health. (2020) 65:731–9. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01406-2

62. Hossain MA, Jahid MIK, Hossain KMA, Walton LM, Uddin Z, Haque MO, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and fear of COVID-19 during the rapid rise period in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0239646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239646

63. Hu Y, Zhang G, Li Z, Yang J, Mo L, Zhang X, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to COVID-19 pandemic among residents in Hubei and Henan Provinces. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. (2020) 40:733–40. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.05.20

64. Hussain I, Majeed A, Imran I, Ullah M, Hashmi FK, Saeed H, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices toward COVID-19 in primary healthcare providers: a cross-sectional study from three tertiary care hospitals of Peshawar, Pakistan. J Comm Health. (2020) 9:1-9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00879-9

65. Huynh G, Nguyen MQ, Tran TT, Nguyen VT, Nguyen TV, Do THT, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding COVID-19 among chronic illness patients at outpatient departments in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2020) 13:1571–8. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S268876

66. Li C, Xu J, Yue L, Shen M, Dai M, Liu N. Knowledge, attitude, and practice survey regarding coronavirus disease 2019 among residents in Hunan Province. Zhong nan da xue xue bao Yi xue ban = J Central South Univ Med Sci. (2020) 45:665–72. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2020.200277

67. Ngwewondo A, Nkengazong L, Ambe LA, Ebogo JT, Mba FM, Goni HO, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, practices of/towards COVID 19 preventive measures and symptoms: a cross-sectional study during the exponential rise of the outbreak in Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2020) 14:e0008700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008700

68. Nicholas T, Mandaah FV, Esemu SN, Vanessa ABT, Gilchrist KTD, Vanessa LF, et al. COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes and practices in a conflict affected area of the South West region of Cameroon. Pan Af Med J. (2020) 35:22963. doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.22963

69. Olaimat AN, Aolymat I, Elsahoryi N, Shahbaz HM, Holley RA. Attitudes, anxiety, and behavioral practices regarding COVID-19 among university students in jordan: a cross-sectional study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2020) 103:1177–83. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0418

70. Pal R, Yadav U, Grover S, Saboo B, Verma A, Bhadada SK. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19 among young adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus amid the nationwide lockdown in India: a cross-sectional survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2020) 166:108344. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108344

71. Reuben RC, Danladi MMA, Saleh DA, Ejembi PE. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: an epidemiological survey in North-Central Nigeria. J Comm Health. (2020) 8:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00881-1

72. Salman M, Mustafa ZU, Asif N, Zaidi HA, Hussain K, Shehzadi N, et al. Knowledge, attitude and preventive practices related to COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in two Pakistani university populations. Drugs Therapy Perspectives: Rational Drug Select Use. (2020) 37:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s40267-020-00737-7

73. Van Nhu H, Tuyet-Hanh TT, Van NTA, Linh TNQ, Tien TQ. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the Vietnamese as key factors in controlling COVID-19. J Comm Health. (2020) 4:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00919-4

74. Yue S, Zhang J, Cao M, Chen B. Knowledge. Attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among Urban and rural residents in China: a cross-sectional study. J Comm Health. (2020) 7:1-6. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00877-x

75. Peng Y, Pei C, Zheng Y, Wang J, Zhang K, Zheng Z, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice associated with COVID-19 among university students: a cross-sectional survey in China. Res Square [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-21185/v1

Keywords: systematic review, meta-analysis, preventive practice, COVID-19, population

Citation: Tadesse AW, Aychiluhm SB, Mare KU, Tarekegn SM and Biset G (2022) Practice Level and Associated Factors Towards the Preventive Measures of COVID-19 Among the General Population; A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 10:844692. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.844692

Received: 28 December 2021; Accepted: 09 May 2022;

Published: 15 June 2022.

Edited by:

Kingston Rajiah, Gandhi Institute of Technology and Management University, IndiaReviewed by:

Hossein Hajianfar, Islamic Azad University, IranJunxiang Chen, University of Pittsburgh, United States

Copyright © 2022 Tadesse, Aychiluhm, Mare, Tarekegn and Biset. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abay Woday Tadesse, YWJheXdvZGF5QHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Abay Woday Tadesse

Abay Woday Tadesse Setognal Birara Aychiluhm

Setognal Birara Aychiluhm Kusse Urmale Mare

Kusse Urmale Mare Setegn Mihret Tarekegn2,4

Setegn Mihret Tarekegn2,4 Gebeyaw Biset

Gebeyaw Biset