- 1Centre for Eye and Vision Research Limited, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Department of Physiotherapy, Yobe State University Teaching Hospital, Damaturu, Nigeria

- 3Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 4School of Nursing, Institute of Health and Management, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 5School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 6School of Optometry, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 7Physiotherapy Department, Yobe State Specialist Hospital, Damaturu, Nigeria

- 8Department of Paediatrics, Yobe State Specialist Hospital, Damaturu, Nigeria

- 9Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria

- 10Department of Geography, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Nigeria

- 11Department of Physiotherapy, Bayero University Kano, Kano, Nigeria

- 12Department of Rehabilitation Science, Western University, London, ON, Canada

- 13Department of Medicine and Surgery, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria

- 14Department of Paediatrics, Barau Dikko Teaching Hospital, Kaduna, Nigeria

Background: Medical and socio-economic uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic have had a substantial impact on mental health. This study aimed to systematically review the existing literature reporting the prevalence of anxiety and depression among the general populace in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic and examine associated risk factors.

Methods: A systematic search of the following databases African Journal Online, CINAHL, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science was conducted from database inception until 30th September 2021. Studies reporting the prevalence of anxiety and/or depression among the general populace in African settings were considered for inclusion. The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Meta-analyses on prevalence rates were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software.

Results: Seventy-eight primary studies (62,380 participants) were identified from 2,325 studies via electronic and manual searches. Pooled prevalence rates for anxiety (47%, 95% CI: 40–54%, I2 = 99.19%) and depression (48%, 95% CI: 39–57%, I2 = 99.45%) were reported across Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex (female) and history of existing medical/chronic conditions were identified as major risk factors for anxiety and depression.

Conclusions: The evidence put forth in this synthesis demonstrates the substantial impact of the pandemic on the pervasiveness of these psychological symptoms among the general population. Governments and stakeholders across continental Africa should therefore prioritize the allocation of available resources to institute educational programs and other intervention strategies for preventing and ameliorating universal distress and promoting psychological wellbeing.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021228023, PROSPERO CRD42021228023.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), a highly transmissible ailment caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus, has generated unparalleled distress on a global scale since it was first diagnosed in Wuhan City in mainland China, with the earliest symptoms reported on the 1st of December 2019 (1, 2). COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the 11th of March 2020 (1, 3), thus joining in a series of historic global outbreaks/pandemics [including Athenian plague of 430 B.C., Antonine plague of 165–180 A.D., Justinian plague, Black death plague, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) pandemic, Smallpox outbreak of 1972, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Swine flu pandemic of 2009, Ebola outbreak of 2014–2016, and Zika outbreak of 2015–2016] that resulted in millions of human deaths (1, 4). Over 200 million cases and about 4.5 million COVID-19-related mortalities have been reported across the globe (3). Despite the concerted efforts of Governments and stakeholders to ameliorate the threat of the disease, incidence and mortality rates continue to increase across different countries and territories. Other factors such as the rapid mutation of the virus exacerbate the level of distress experienced on a global scale (3, 5). Uniquely, the COVID-19 pandemic not only affects global health systems but also severely affects the global economy and financial markets (6). A palpable decline in income, greater unemployment, and on-going disruptions in the transportation, service, and manufacturing industries are among the many consequences of the current pandemic (6).

The African continent is comprised of 54 countries situated across five distinct regions (Eastern, Middle, Northern, Southern and Western) and accounts for ~17.51% of all global inhabitants (i.e., 1.2 billion) as of 2021 (7, 8). Many countries across the continent are faced with healthcare problems due to weak healthcare infrastructures and socio-economic challenges (9). Broadly, these challenges arise from inadequate human resources, poor leadership and management, and inadequate budgetary allocation to cover essential healthcare expenditures (9). Other indirect factors limiting the provision of and access to quality healthcare in most African countries include poverty, conflict, unemployment, food insecurity, inequality, climate change, and rapid industrialization (10). Given the peculiar nature of the disease and the subsequent initiatives to contain its spread, the current pandemic has had a direct impact on the overall wellbeing of the global populace (11). Factors such as high transmissibility, a remarkable number of hospital admissions, the need for isolation during treatment, respiratory problems, and increased morbidity and mortality rates, have led to a general decline in overall health and wellbeing (3). Compared to countries in other parts of the world with robust and sophisticated healthcare systems, many African countries are faced with compounded challenges due to existing deficiencies in healthcare service delivery (12). Other indirect factors associated with the pandemic such as travel restrictions, lockdowns, job loss and economic decline, although affecting the entire global population, may have a relatively greater impact on Africans (12). These multifactorial and often indirect consequences of the pandemic not only reduce quality of life, and general wellbeing, but also affect mental health status at the societal level, leading to the pervasiveness of symptoms such as anxiety and depression (13). Therefore, a summative examination of the mental health status in the African population during the pandemic is of paramount importance.

A growing number of primary studies have been conducted to ascertain data relating to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on various mental health domains across the globe (14, 15). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have also been conducted to summarize rising mental health concerns on both a regional and global scale (13, 16–18). Other systematic reviews have examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents (19), and the prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety and depressive symptoms among pregnant women (20). The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and other psychological variables in the general population during the pandemic have also been examined (21). However, an assessment of the prevalence of these symptoms and associated risk factors among the general populace in Africa is currently lacking from the literature. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to address this knowledge gap by examining the prevalence of anxiety and depression among the general populace across the African continent during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to assess the associated risk factors as a secondary aim of the study.

Methods

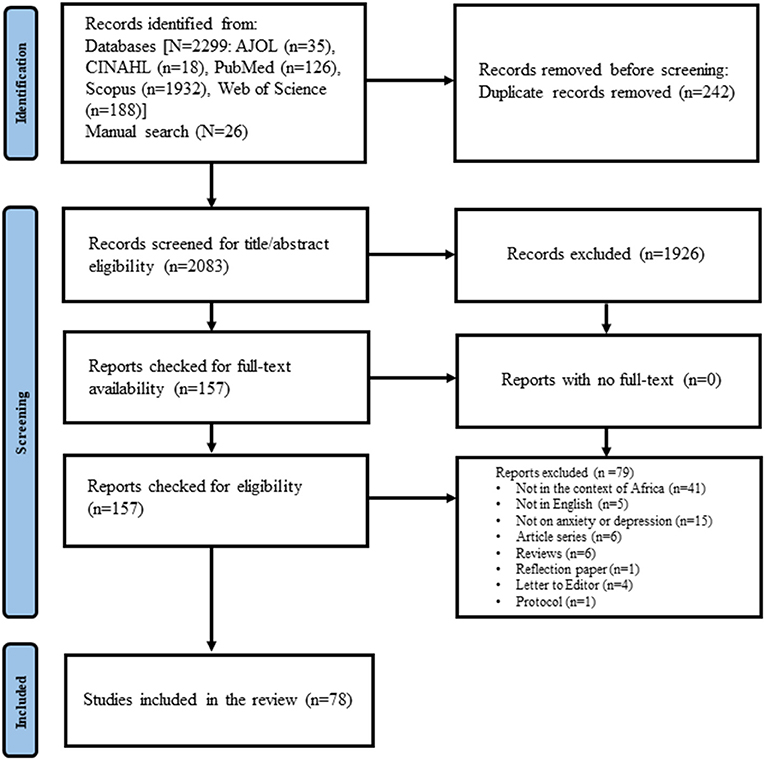

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (22). A protocol of the study was first registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; Ref. No: CRD42021228023) in January of 2021 prior to commencement. Authors (SJW, UMB, MC, DS, PK, and AMYC) conceptualized the study, and developed the protocol.

Search Strategy

A systematic search of the following databases African Journal Online, CINAHL, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from database inception until 30th September 2021 was performed. The search terms were grouped under three themes, namely: “COVID-19,” “anxiety & depression,” and “Africa”. The search theme “Africa” included all the 54 African countries to ensure wider coverage of the studies conducted across the continent. The electronic search involved combining terms under each theme using the Boolean operator “OR”. The search themes were then combined using the Boolean “AND” (Appendix 1 presents the details of the search strategy adopted in the study). Citation management software (EndNote X9, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA) was used to archive and organize search results and remove duplicates. Two of the authors (UMB, JWP) independently conducted the electronic search. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third author (SJW). The reference lists of included studies were manually searched by four review authors (DS, HAJ, AAG, and IMB).

Study Eligibility Criteria

Studies that adopted a survey method of data collection were included if they (1) assessed anxiety and/or depression among the general populace in African settings, during the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) were available in full text. Gray literature (unpublished studies) were included to minimize publication bias as recommended by Paez (23). Excluded studies were (1) systematic reviews; (2) review protocols; (3) case reports; (4) case series (5) qualitative papers; (6) editorials or (7) conference abstracts.

Article Screening

Studies identified through the electronic search underwent a three-stage title, abstract and full text screening. Two of the authors (SJW, UMB) independently selected eligible studies that adopted a survey methodology to examine the prevalence of anxiety and/or depression among the general populace in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third author (PK).

Data Extraction

The primary data extracted from included studies were the prevalence rates (summary data) of anxiety and/or depression that were assessed using questionnaires in the included studies. Other data extracted included associated risk factors, author details, aims and objectives, sample size, participant sex and other demographic characteristics, survey instrument details, other psychological variable(s) assessed, country of origin and overall conclusions. Data extraction was conducted independently by two authors (ASM, FAM) using a standardized tool designed in Excel. Disagreements between authors during the data extraction process were resolved by further discussions with a third author (UMB).

Quality Appraisal of the Included Studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) checklist for observational studies (24). Two authors (TM, MUA) independently conducted the methodological quality assessment. The assessment criteria were adapted from a previous study (24). Scores ranged from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher quality. An overall score ≥ 7 was indicative of good methodological quality across studies, while scores of 1–3 and 4–6 indicated poor and moderate quality, respectively.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

The extracted data were first narratively synthesized (CM, DS, and MAK) due to considerable heterogeneity in reported outcomes across included studies. Risk factors for anxiety and depression reported in the included studies were also synthesized. The narrative synthesis of quantitative findings [i.e., expressed as percentages, correlations (r), between-group differences (χ2), odds ratios (OR) or adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI)] was conducted in accordance with recommendations provided by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (25). Using a random-effects model, reported prevalence estimates (i.e., percentages) for anxiety and/or depression were aggregated in several meta-analyses to generate pooled prevalence rates. The percentage prevalence score from each study was then converted to a raw prevalence score using the following equation: (overall population × reported percentage)/100. Meta-analyses were conducted by pooling the “raw prevalence score” and the “overall population score” from each study (https://www.meta-analysis.com/pages/tutorials.php). Two separate meta-analyses were conducted to estimate the overall effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the African continent. Subsequent subgroup analyses were conducted by aggregating studies according to region (i.e., Eastern, Middle, Northern, Southern, and Western Africa), country (for subgroups of ≥ 2 studies with data originating from the same country), outcome measures, and study period. A random-effects model was choosen based on the high clinical (for example study population, study period, and gender distribution) and methodological (for example study designs and mode of data collection) heterogeniety among the studies included in the meta-analyses (26). All meta-analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (CMA version 3.0, Biostat Inc., Englewood, New Jersey, USA) (UMB, CM, and DS).

Results

A total of 78 studies (14, 15, 26–−101) conducted between January 2020 and February 2021 were included in the final review (Figure 1). Five of these inclusions were categorized as gray literature (unpublished studies) (27–32).

Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 62,380 participants were recruited in the included studies, with the largest proportion of participants being male (49.8%, n = 31,074). Females constituted 47.3% of all participants (n = 29,479). Eight studies (2.9%, n = 1,854) did not report participant sex. More than half of participants were from the general population (69.9%, n = 43,646), Health workers constituted the second largest proportion (16%, n = 10,367). Others were students (11.6%, n = 7,249), and people with medical conditions (2.0%, n = 1,300). Except for Dyer et al. (33), who recruited participant samples aged 10–24 years, overall age ranged from 18 to 84 years. Only ten studies (12.8%) collected data using researcher-developed questionnaires. The majority (64.1%, n = 50) utilized instruments which were validated and reliable. However, only 24.4% (n = 19) of the studies used translated and cross-culturally validated assessments during data collection.

Many of the included studies were from Ethiopia (24.4%, n = 19), Nigeria (20.5%, n = 16), and Egypt (14.1%, n = 11). Others were from Libya (5.1%, n = 4), South Africa (3.8%, n = 3), Ghana (3.8%, n = 3), Uganda (2.6%, n = 2), Morocco (2.6%, n = 2), Kenya (2.6%, n = 2), Tunisia (2.6%, n = 2), Libya (2.6%, n = 2), Cameroon (2.6%, n = 2), Zambia (1.3%, n = 1), Algeria (1.3%, n = 1), Togo (1.3%, n = 1), Sudan (1.3%, n = 1), and Mali (1.3%, n = 1). Four studies (5.1%) covered more than one African country (15, 34–36), with two others (2.6%) covering sub-Saharan Africa (37, 38) and one other (1.3%) west African country (39).

The most commonly used tools for assessing anxiety and depression among the included studies were the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) (29.5%, n = 23), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (23.1%, n = 18), respectively. These were followed by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) (23.1%, n = 18), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (8.9%, n = 7). A summary of characteristics for included studies is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Methodological Quality

Most included studies [78% (n = 61)] were of good methodological quality (ARHQ ≥ 7). The median (range) score was 8 (5–10) points. The quality appraisal indicated that all included studies provided sources of information regarding the assessment of depression and anxiety, and participant recruitment settings (Appendix 3).

Quantitative Synthesis on COVID-19 Related Anxiety in Africa

Overall Prevalence of Anxiety in Africa During the COVID-19 Pandemic

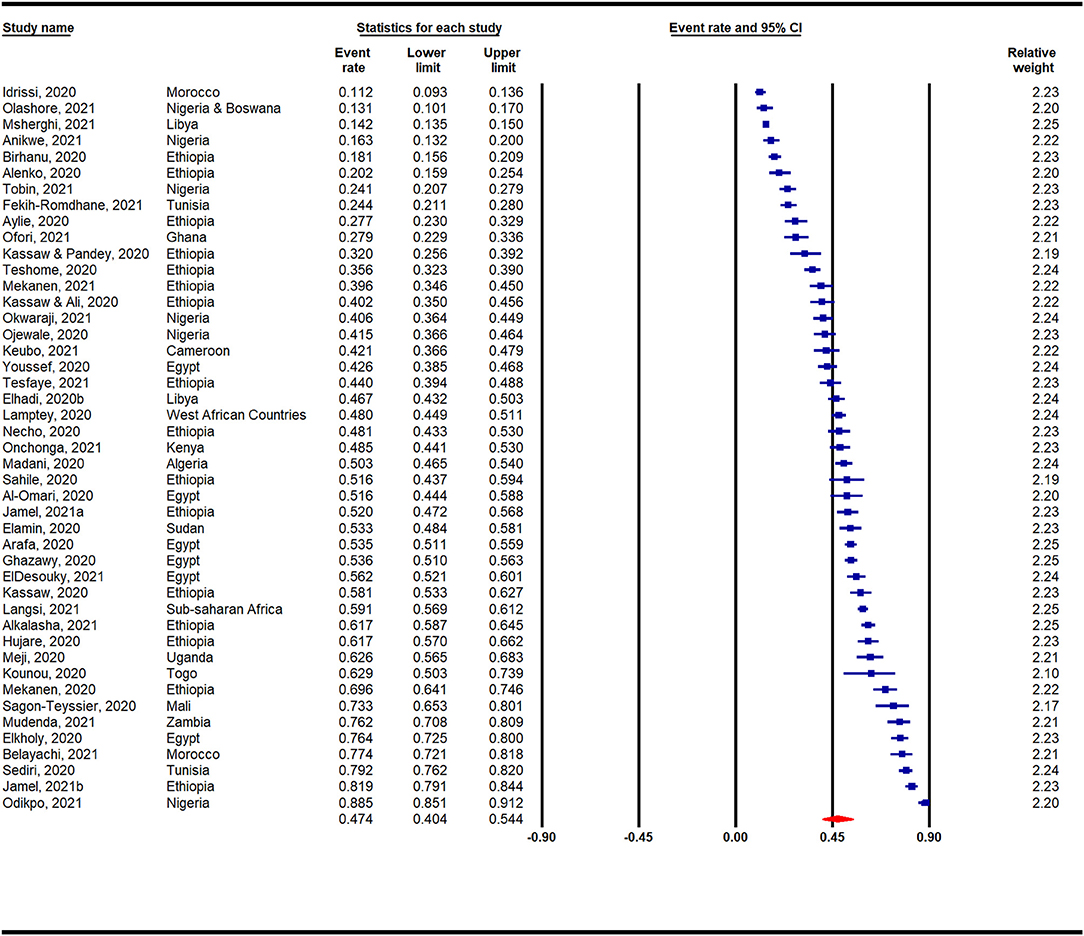

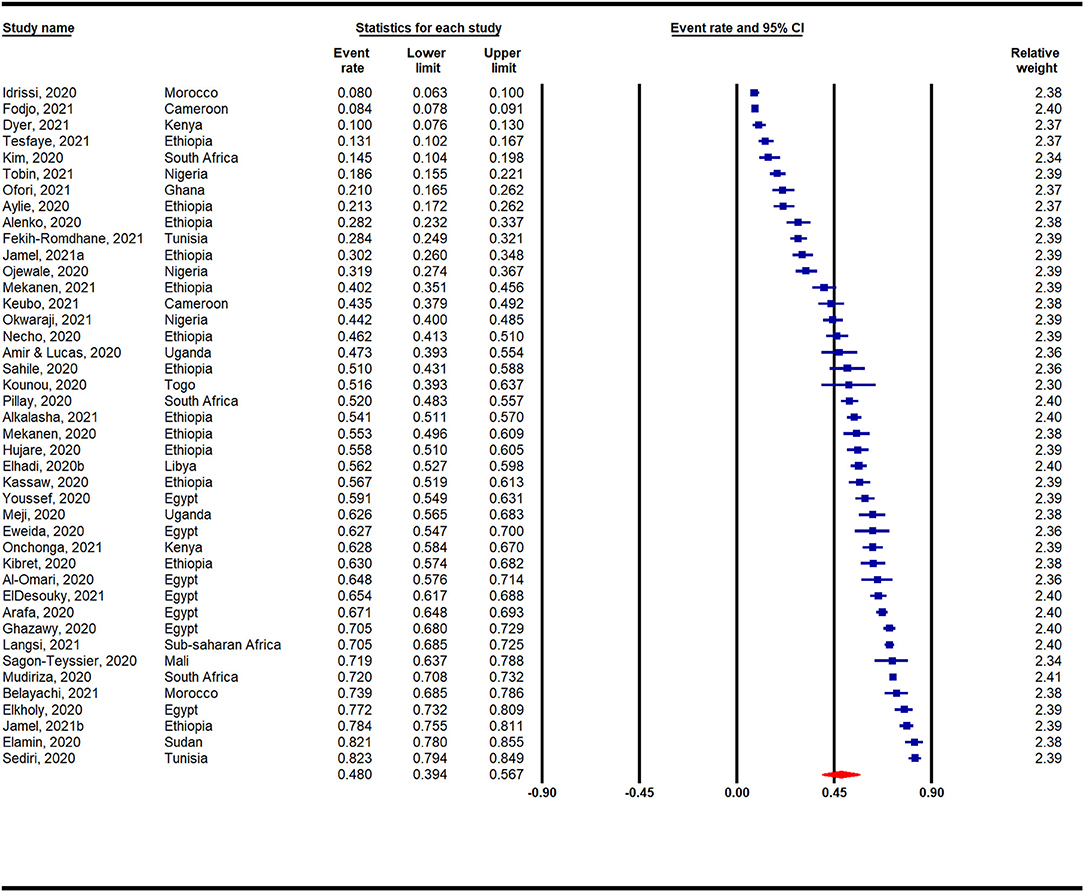

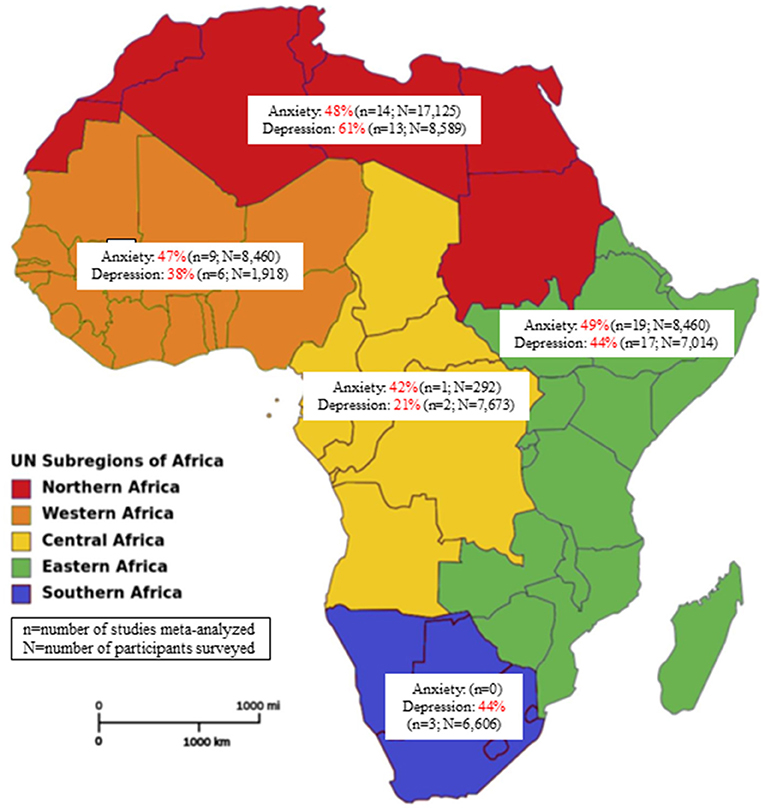

Figure 2 presents a meta-analysis on the prevalence of anxiety across Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. A pooled prevalence rate of 47% (95% CI: 40–54%) was reported among 45 individual studies that surveyed 31,300 participants. Heterogeneity among the pooled studies was high (I2 = 99.19%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of anxiety in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic according to region is presented in Appendix 3 and Figure 3. A forest plot illustrating further sub-analysis based on the outcome measures utilized to assess anxiety in the included studies is presented as Appendix 4.

Figure 3. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in Africa by regions during the COVID-19 pandemic (source of image: File:Africa map regions 2.png-Wikipedia).

Prevalence of Anxiety in Africa by Countries During the COVID-19 Pandemic

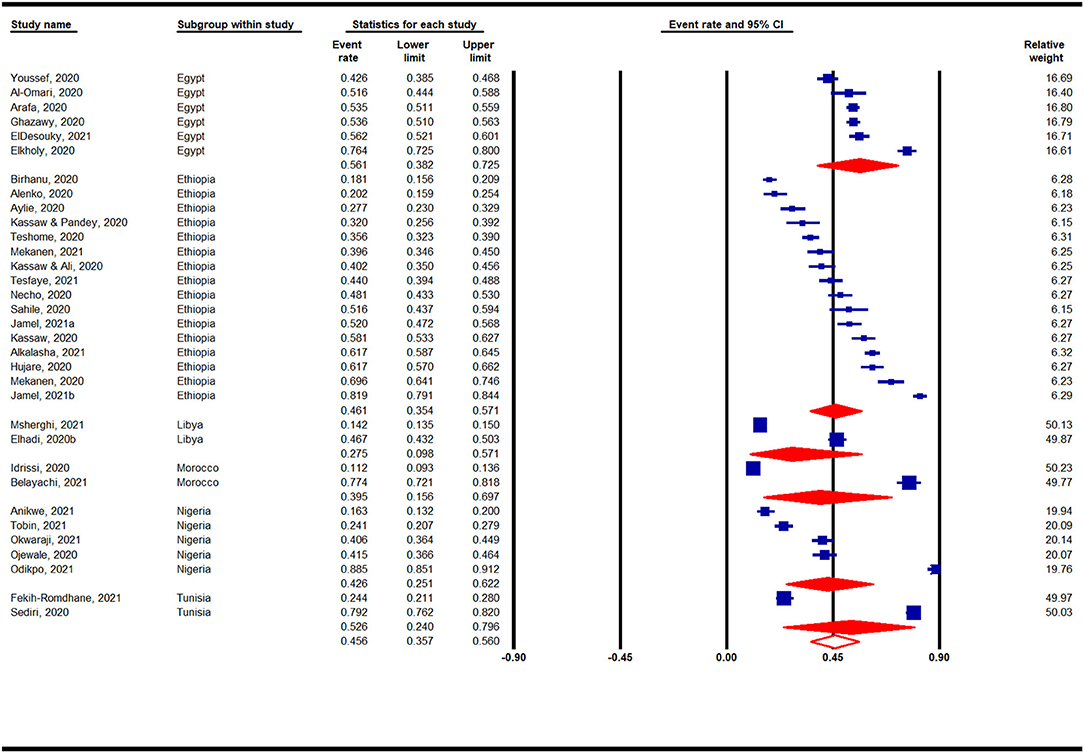

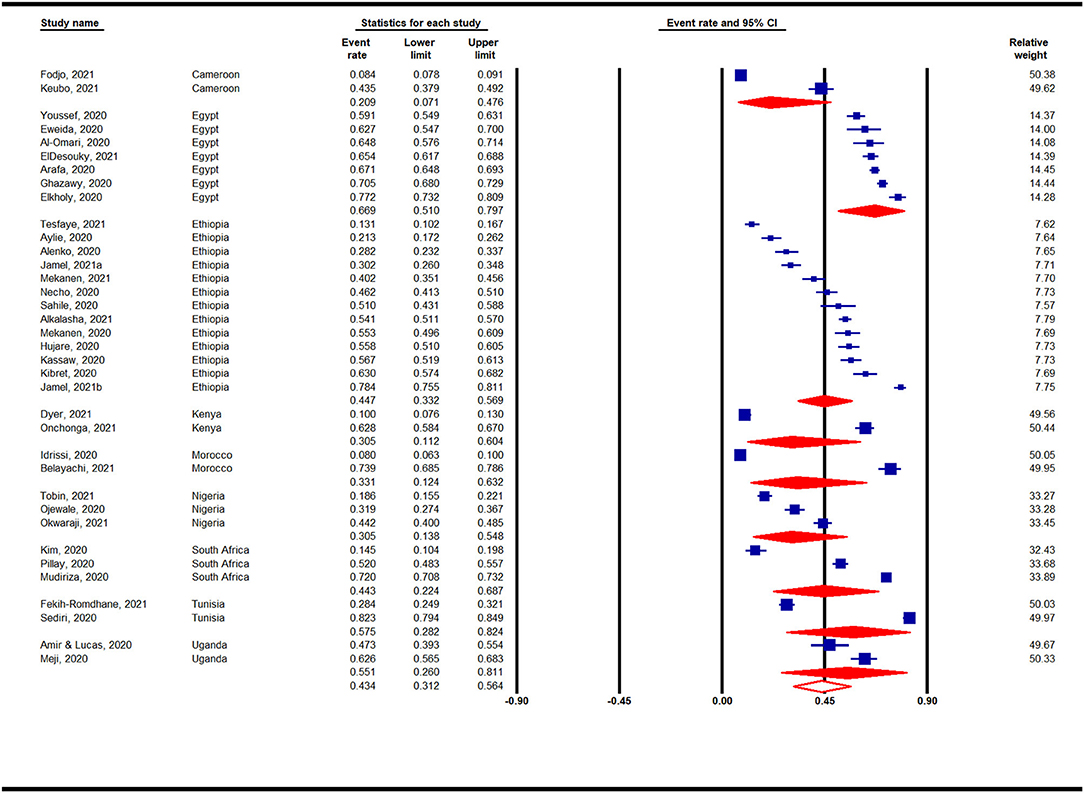

Country-based subgroup analyses on the prevalence of anxiety in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that among the 6 countries analyzed (with ≥ 2 studies) (Figure 4), the highest prevalence was reported for studies conducted in Egypt (56%, 95% CI: 38–73%, n = 6), whereas the lowest prevalence was reported for studies in Libya (28%, 95% CI: 10–57%, n = 2).

Prevalence of Anxiety in Africa by the Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Sub-analysis based on the period of the COVID-19 pandemic is presented as Appendix 5. The periods are categorized into Early 2020 (1st January−30th June), Late 2020 (1st July−31st Dec), and Early 2021 (1st January−30th June). Higher prevalence was reported for studies conducted in the Late 2020 (53%, 95% CI: 39–66%, n = 6) in comparison with Early 2020 (47%, 95% CI: 39–56%, n = 30).

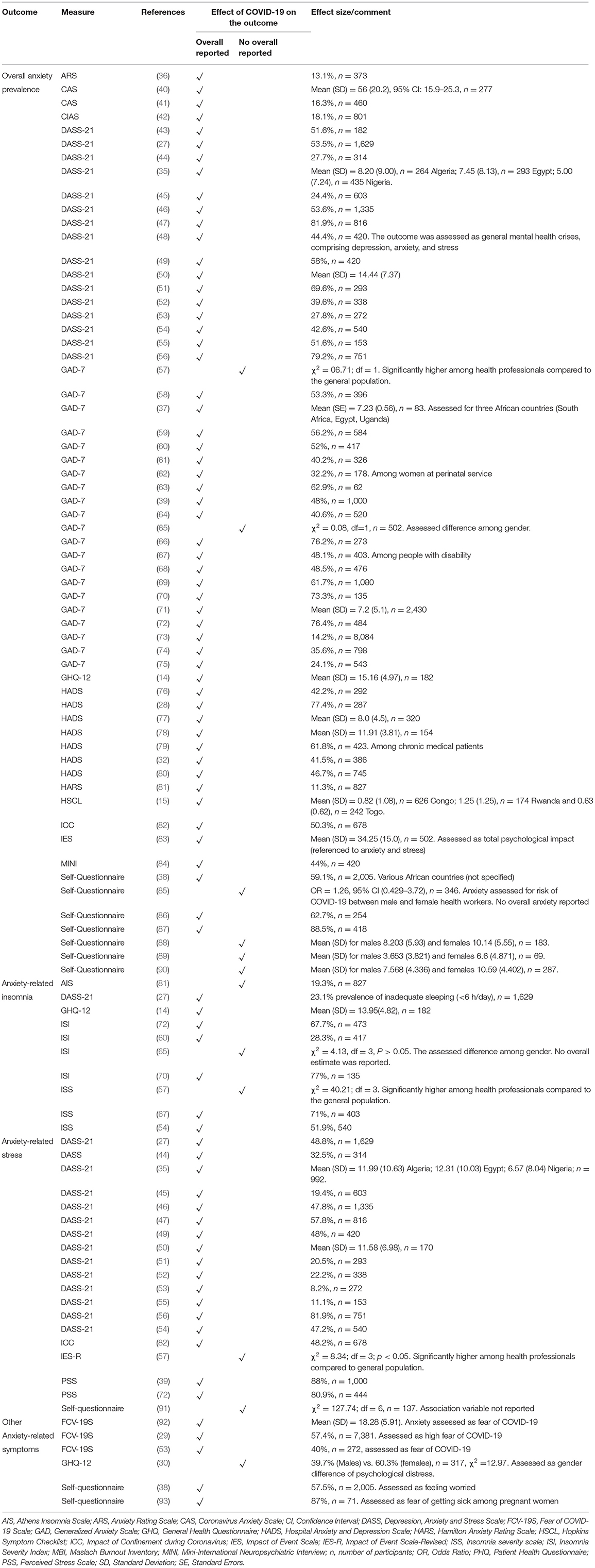

Narrative Synthesis on COVID-19 Related Anxiety in Africa

Overall, sixty-five studies (n = 65) assessed anxiety and its related symptoms in Africa (Table 1). Anxiety prevalence ranged from 11.3% (n = 827) among the general population in Morocco (81) to 88.5% (n = 418) among frontline nurses in Nigeria (87) (Table 1). DASS-21 (n = 16) and GAD-7 (n = 21) were the most used measures of anxiety, with reported proportions ranging from 18.1 to 81.9% and 24.1 to 76.4%, respectively. Anxiety prevalence was significantly associated with depression or depressive symptoms (35, 40, 50). Other anxiety-related symptoms reported were insomnia (14, 27, 40, 54, 60, 65, 67, 70, 72, 77, 81), fear of covid (29, 53, 92), psychological distress (30), worry (38), and fear of getting sick (93) (Table 1).

Socio-Demographic Factors Associated With COVID-19 Related Anxiety in Africa

Demographic variables played a significant role in anxiety prevalence. Sex was the most reported demographic variable. Most studies indicated higher levels of anxiety among females compared to males (27, 28, 30, 35, 43, 45–50, 54, 59, 60, 63, 68–70, 72, 73, 75, 81, 83, 94, 95) with the exception of one study which demonstrated an association between anxiety and being male (38). Urban residency (52, 62, 69, 81, 83), living alone (without family) and lower family income or socioeconomic status were also identified as risk factors for anxiety (35, 44, 48, 49, 69). Higher educational status was associated with increased anxiety among healthcare professionals (40, 58, 61, 69) and the general population (42, 49, 62, 83, 92). Anxiety level was higher among other professions compared to healthcare workers (27, 83, 92). Among the various healthcare professions, medical laboratory work was significantly associated with higher anxiety compared to others (AOR = 2.75, 95% CI: 1.78–4.79) (47). Younger age (30, 35, 45, 54, 67, 71, 72, 76, 79, 82, 83, 85), being a widow or single (38, 42, 67, 73), being unemployed (38, 67, 73) and being a student (35, 52, 71) were also significantly associated with COVID-19 related anxiety. Additionally, negative use of religious coping mechanisms was significantly associated with greater anxiety (36, 45).

Other Associated Factors of COVID-19 Related Anxiety in Africa

Anxiety was highest among those infected with SARS-CoV-2 (OR=9.59, 95% CI: 2.28–40.25) (73) and was significantly associated with having an infected relative or friend (39, 44, 46, 58, 96), being involved in discussions regarding COVID-19 related illness or death (45), fear of contamination (39, 76), fear of death (76) and exposure to individuals with SARS-CoV-2 or who were at risk of having SARS-CoV-2 (15, 43, 58, 74, 95). History of or having an existing mental illness (30, 35, 42, 43, 45, 69) as well as a history of an existing medical condition or chronic disease (46, 49–51, 79, 83, 94, 96) were associated with greater anxiety. Poor knowledge of COVID-19 (48, 49) and preventive practices were associated with increased odds of developing anxiety among pregnant women (41). Similarly, increased COVID-19 related anxiety was significantly associated with being a primigravida (AOR = 3.05, 95% CI: 1.53–6.08), having a gestational age >36 weeks (OR = 5.49, 95% CI: 1.04–28.78) (41), being pregnant (AOR = 4.39, 95% CI: 2.29–12.53) (62) and having a lack of social support while pregnant (AOR = 4.39, 95% CI: 2.29–12.53) (62). Highly protective behavior (AOR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.5–3.3) and perceived risk behavior (OR = 3.7, 95% CI: 1.5–12.4) predict higher anxiety among the general population (42) but not among healthcare professionals (58). Displacement due to conflict (80), lack of emotional support from family or society (46, 66, 79, 97), and experiencing discrimination or racism (AOR = 5.02, 95% CI: 1.90–13.26) (84) were significantly associated with COVID-19 related anxiety. Reading or watching COVID-19 related news via media or internet sources was associated with increased anxiety (27, 43, 45, 46). Healthcare workers were anxious about their relatives and family members contracting SARS-CoV-2 from them (39, 51, 85, 95). Similarly, long hours working in the hospital (78), fewer years of hospital experience (<3 years) (61), a lack of updated information relating to COVID-19 (74), poor access to personal protective equipment (70, 96), working in a COVID-19 isolation center (54, 60), adult medical-surgical unit (60, 95) or emergency department (58, 60) were significant predictors of higher anxiety. COVID-19 related anxiety was also associated with insomnia among healthcare workers (AOR = 6.38, 95% CI: 4.19–9.73) (54), substance or tobacco use among patients with chronic illness (AOR = 2.27, 95% CI: 1.20–4.30) (79) and alcohol use among the general public (OR 5.50, 95% CI: 2.18–13.87) (75). Among people with disabilities, anxiety-related insomnia was significantly higher among individuals with impaired vision (AOR = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.42–6.35), and hearing (AOR = 10.2, 95% CI: 4.52–35.33) (67).

Quantitative Synthesis on COVID-19 Related Depression in Africa

Overall Prevalence of Depression in Africa During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Figure 5 presents a meta-analysis on the prevalence of depression across Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. A pooled prevalence rate of 48% (95% CI: 39–57%) was observed for 42 individual studies that surveyed 33,805 participants. Heterogeneity among pooled studies was high (I2 = 99.45%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic according to African region is presented in Appendix 6 and Figure 3. A forest plot illustrating further sub-analysis based on the outcome measures utilized to assess depression in the included studies is presented as Appendix 7.

Prevalence of Depression in Africa by Countries During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Country-based subgroup analyses for depression prevalence indicated that among the nine countries (with ≥ 2 studies) analyzed, the highest prevalence was reported for studies conducted in Egypt (67%, 95% CI: 51–80%, n = 7), whereas studies conducted in Nigeria (31%, 95% CI: 14–55%, n = 3) and Kenya (31%, 95% CI: 11–60%, n = 2) reported the lowest pooled prevalence rates (Figure 6).

Prevalence of Depression in Africa by the Period of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Sub-analysis based on the period of the COVID-19 pandemic is presented as Appendix 8. The periods are categorized into Early 2020 (1st January−30th June), Late 2020 (1st July−31st Dec), and Early 2021 (1st January−30th June). Higher prevalence was reported for studies conducted in the Early 2020 (51%, 95% CI: 43–59%, n = 6) in comparison with Late 2020 (31%, 95% CI: 14–55%, n = 30).

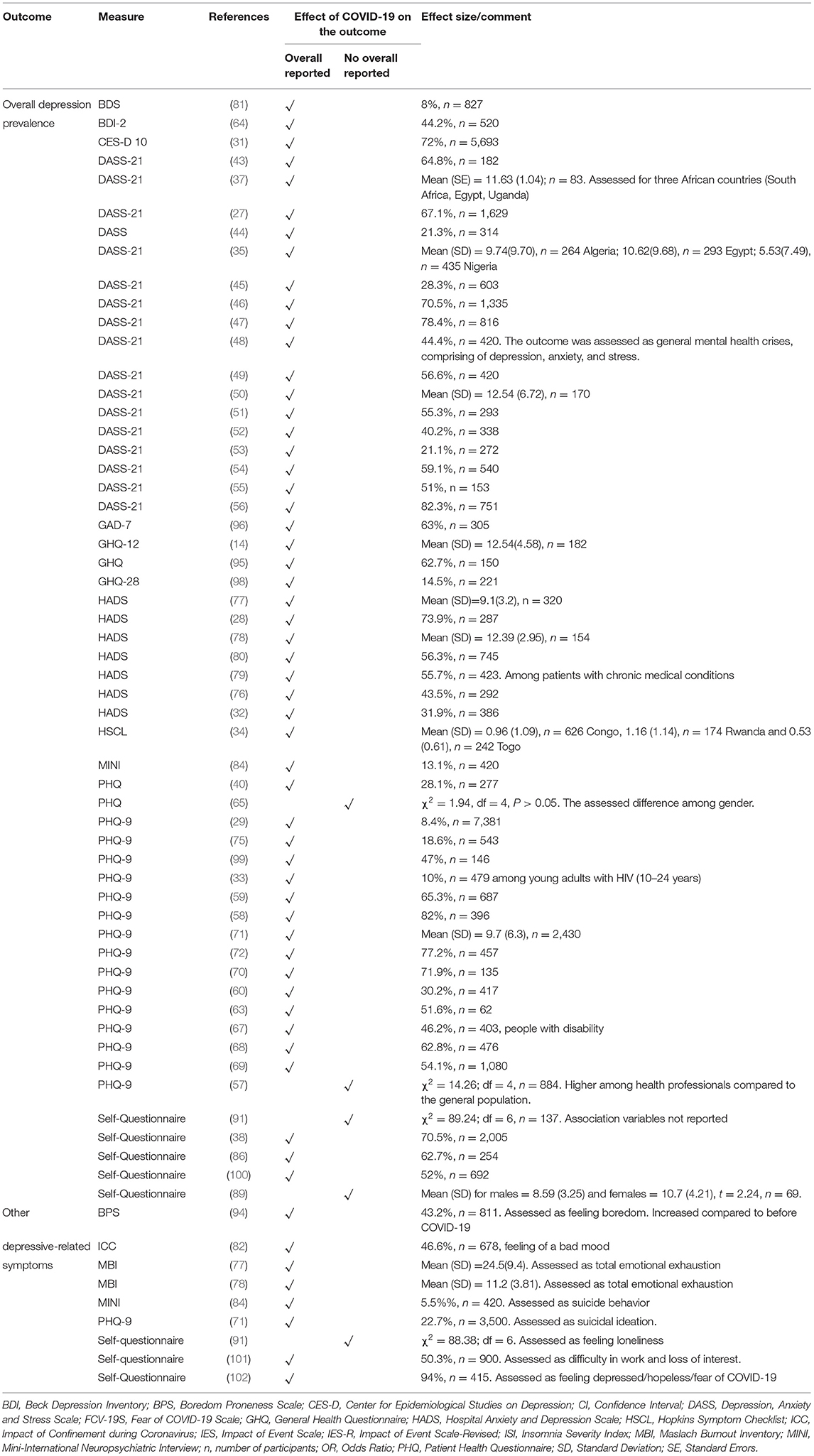

Narrative Synthesis on COVID-19 Related Depression in Africa

Overall, fifty-nine (n = 59) studies reported depression or depressive symptoms (Table 2). The prevalence of depression ranged from 8% (n = 846) among the general population in Morocco (81) to 82.3% (n = 751) among women in Tunisia (56) (Table 2). DASS-21 (n = 17) and PHQ (n = 17) were the most commonly used measures of depression, with proportions ranging from 21.1 to 82.3% and 8.2 to 82%, respectively. Depression scores were significantly correlated with overall anxiety (14, 35, 40, 50) and sleeplessness (14, 54). Overall depression was significantly associated with symptoms of mania (AOR = 4.3, 95% CI: 1.71–11.02) (84) and Fear of Covid scores (r = 0.5, p < 0.001) (77). Depression-related symptoms included reports of boredom (94), poor mood (82), loneliness (91), loss of interest (101), total emotional exhaustion (77, 78) and suicidal ideation or behavior (71, 84) (Table 2).

Socio-Demographic Factors Associated With COVID-19 Related Depression in Africa

Among the demographic characteristics of the respondents, older age (≥65 years) was associated with a decrease in depression or depressive symptoms (34, 80) (35, 45, 59, 81, 94), while another study reported greater depression among middle-aged people (45–65 years) (58). The prevalence of depression was significantly higher among females than males (27, 28, 31, 34, 35, 43–50, 59, 60, 63, 72, 79, 81, 94, 99). Marital status (i.e., being single, widowed, divorced, or separated) (59, 67, 79), living alone without family or having a lack of emotional support from family and society (71, 97) (45, 46), family size ≥ 3 (48, 49) and living in an urban area (31, 32, 69) were found to significantly increase depression, with the exception of two studies (47, 60) which indicated that married people were more than three times as likely to experience depression (p < 0.05). Higher educational level and professional qualification were found to significantly increase depression (29, 31, 49, 59, 60, 69) with the exception of one study, which indicated higher depressive symptoms among non-educated people with disability (AOR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.12–5.90) (67). Unemployment (AOR = 2.1, 95% CI: 1.32–5.11) (67) and low socioeconomic status significantly influenced the prevalence of depressive symptoms (35, 48, 49, 57, 69). Among healthcare professions, medical lab workers (AOR = 4.69, 95% CI: 2.81–9.17) were more likely to experience depression (47), followed by nurses (47, 63). Religion also contributed to the prevalence of depression, with negative use of religious coping mechanisms being associated with greater depression (r = 0.135) (45).

Other Associated Factors of COVID-19 Related Depression in Africa

The prevalence of depressive symptoms was significantly higher among healthcare professionals compared to the general population (χ2 = 14.26, p < 0.01) (57). In the healthcare sector, depression prevalence was associated with working in the emergency department (58, 60, 80), fewer years of experience (60), working in a surgical unit (80), working in a COVID-19 isolation center in comparison to other units (AOR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.05–4.39) (47) and in fever hospitals compared to designated COVID-19 quarantine hospitals (OR = 1.52, 95% CI: 1.11–2.09) (72). Similarly, nurses who received negative feedback from their families (AOR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.27–3.79) and a lack of COVID-19 management guidelines (AOR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.21–4.21) were more likely to experience depression (51). Depression was associated with a history of other medical conditions or chronic disease (32, 44–46, 49, 63, 94), flu-like symptoms (29), fear of death (76), the recent death of a loved one (84), quarantine or home stay (29, 43, 44) and poor social support among students (35, 44, 46) and chronic medical patients (79). Reading or watching COVID-19 related news via media or internet sources was associated with increased depression (43, 45, 97). A history of or existing mental illness (35, 43, 51), the current use of medication (75), perceived COVID-19 risk (98), and exposure to individuals with SARS-CoV-2 at risk of having contracted SARS-CoV-2 (43) or having a family member with COVID-19 positive test results (52) significantly increased the odds of COVID-19 related depression. Prevalence of depression was significantly associated with insomnia (AOR = 7.58, 95% CI: 4.91–11.68) among healthcare workers (54), and alcohol use among the general population (OR 4.27, 95% CI: 1.56–12.04, p < 0.01) (75). Prevalence of depression was also associated with conflict-affected regions (71). Stigma significantly affected symptoms of depression (34, 80).

Discussion

This study aimed to systematically review the literature on the prevalence and risk factors associated with anxiety and depression among the general populace in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, this review is the first most comprehensive multidimensional synthesis of COVID-19 associated depression and anxiety prevalence across the African continent. Although new data is rapidly emerging, the prevalence reported in African countries has largely been overlooked in similar reviews encompassing the global population (16, 21), while a recent African-based systematic review in this area of research focused only on healthcare workers (18) or included only limited number of studies (103). Although no causal inference can be made given the interplay of other related factors (i.e., lockdowns, misinformation, civil unrest, etc.), our evidence suggests the COVID-19 pandemic had a substantial impact on anxiety and depression among the general populace in Africa. The meta-analysis results indicated a high overall prevalence of anxiety (47%). Regionally, the highest prevalence of anxiety was seen in Eastern Africa (49%), with the lowest in the Middle African region (42%). Furthermore, the overall prevalence of depression in Africa (48%) was comparable to the prevalence of anxiety. Northern and Middle African regions had the highest (61%) and lowest (21%) prevalence rates of depression in the continent, respectively. Commonly reported risk factors for anxiety and depression were sex (i.e., female) and a history of chronic medical conditions. Age was a risk factor for both psychological symptoms, with lower and higher (≥60 year) ages relating to greater levels of anxiety and depression, respectively.

To contextualize the present findings in the existing literature, a previous review on the global prevalence of anxiety disorders reported Africa to have a lower prevalence (5.3%) compared to Europe (10.4%) and the United States (0.7–16.2%) before the emergence of COVID-19 (104, 105). Similarly, depression was found to be higher in Southeast Asian and Western Pacific regions (106). However, with the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the global prevalence of mental health problems increased exponentially. The pooled prevalence of anxiety in this review was higher than that reported in China (22–28%) (13, 107, 108), and South Asian countries (41.3%) (109). The prevalence of depression was also reported to be higher in Africa compared to the United States (5.1–24.6%) (105) and China (22%) among healthcare workers. A collation of studies published at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (between January 2020-April 2021), reported wider ranges of prevalence rates of anxiety (9.5–73.3%) and depression (12.5–71.9%) among healthcare workers in Africa (18). Our meta-analytic findings on the overall prevalence of anxiety and depression are slightly higher in comparison with an earlier systematic review and meta-analysis (between February 2020-February 2021) that reported 37% and 45% prevalence rates of anxiety and depression, respectively (103). Apart from the fact that our search for included studies extends to the end of September 2021, the inclusion of fewer studies by Chen et al. (n = 28), might have resulted in the discrepant findings.

In the narrative synthesis, we report a wide-spread prevalence of COVID-19 related-anxiety (11.3–88.5%) and depression (8.0–82.3%) across the included studies. Pooled prevalence rates reported for anxiety (47%) and depression (48%) were roughly equivalent, suggesting that these symptoms may occur in tandem rather than independently of one another. It should be noted that the largest proportion of studies reported in this review also represented countries with the largest GDP and more developed healthcare infrastructure in Africa (i.e., Nigeria, Egypt, Ethiopia). This suggests that in most other African countries with comparatively lower GDP and less developed healthcare infrastructure, the prevalence of anxiety and depression is likely to be either understudied, underreported or presumably worse. Libya was the only exception, with a relatively lower prevalence of anxiety (28%) in comparison to most other countries in Africa. Although on-going geopolitical events (e.g., civil war, change in political leadership, etc.) possibly overshadow the effect of the pandemic in terms of an attributable cause of anxiety (71), the number of studies was also limited (i.e., n = 2) (73, 80), suggesting that this subgroup may be comparatively underpowered. More large-scale survey studies need to be conducted in impoverished African countries to produce a broader and more comprehensive picture of COVID-19 related anxiety and depression prevalence.

The concomitant effects of socioeconomic, political, and managerial challenges are also factors attributed to the higher prevalence of anxiety and depression. Many countries in the African continent face healthcare challenges owing to a limited number of healthcare workers, insufficient budgetary allocation to improve healthcare infrastructure, and poor leadership coupled with inter-professional conflict among healthcare workers, ultimately making the health system less effective in handling the COVID-19 pandemic (9, 12). Furthermore, other indirect factors such as endemic poverty, large disparities between the wealthy and the impoverished, geopolitical instability and insecurity (e.g., Boko Haram, the Islamic State's West Africa Province, banditry, and communal clashes), high rates of unemployment, and an unequal or ineffective social support system further exacerbate the burden associated with the pandemic response in comparison to other continents (10). Together, these factors make it difficult for the general population to cope with and adhere to broad mandates and preventative measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, or quarantines as many individuals and families struggle economically. The overall impact translates to a reduced quality of life and a general decline in mental health (e.g., anxiety and depression) (11).

As wealthy countries progress expeditiously toward general immunity through large scale, fully subsidized, and newly mandated vaccination programs (110), many developing countries, and indeed entire continents, are bracing to prepare for potentially endemic COVID-19. The hesitancy of G7 countries to pledge support for the provision of initial vaccine doses to other developing countries while concomitantly stockpiling booster vaccines (111), will inevitably widen the global divide between those who are vaccinated and unvaccinated, a distinction now being referred to “the jabs and the jab-nots” (112). Normalization of community mask-wearing, particularly in the rural areas of developing countries, not only require the free distribution of masks but also multifaceted promotion strategies (e.g., text reminders, signage, advocacy by local religious leaders, etc.) for eliciting changes in social norms as the driver of sustained, community-wide behavior change (113). Policies on the adoption of vaccine passports, while meant to incentivize vaccination among the general public, are replete with ethical and legal concerns (114). Within Africa, the public perception of these impending circumstances may potentially exacerbate symptoms of COVID-19 related anxiety and depression (29, 53, 92), in addition to the possibility of novel viral strains that are likely to emerge in subsequent waves (5). The anticipatory distress of potentially contracting the virus (30, 38, 93) among the overall population (encompassing frontline health care workers) (87) is contributing to what we see as an emerging mental health crisis throughout the African continent (36).

Our study has several strengths. Firstly, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analyses on the overall prevalence of anxiety and depression in the African continent during the COVID-19 pandemic and various sub-analyses based on the African countries, regions, outcome measures and study period. Secondly, our literature search was robust, encompassing a search theme that included all the countries in Africa, and we searched the “African Journal Online” database to ensure wider coverage of published studies in the research area. Finally, we adopted an appropriate methodological quality checklist (the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) in the study. However, this review has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the reported findings. Firstly, our search was limited to articles published in the online academic journals. Therefore, locally published articles in African-based non-indexed journals might have not been identified during the literature search process. Secondly, due to high heterogeneity reported in the study, care should be taken when interpreting the meta-analyses. Finally, we excluded conference abstracts and non-English language studies from the review, which may limit the external validity of the study.

Conclusions

Understanding the current prevalence of anxiety and depression in Africa is important for the allocation of resources dedicated to mental healthcare providers and related education programs. In the coming year, broader access to vaccines and masks, and the societal pressure to either adopt or avoid these preventative strategies are also potential sources of anxiety and depression. This may be ameliorated through the robust implementation of COVID-19-related education programs and subsequent provision of mental healthcare.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

UB: accessed and verified data, conceptualization, article electronic search, article screening, meta-analysis, and manuscript drafting. PK and AC: conceptualization, manuscript drafting, and project supervision. MC: accessed and verified data, conceptualization, narrative synthesis, meta-analysis, and manuscript drafting. DS: accessed and verified data, conceptualization, manual search narrative synthesis, meta-analysis, and manuscript drafting. TM: quality rating and manuscript drafting. JP: article electronic search. AM and FM: data extraction. HJ, IB, and AG: manual search, and manuscript drafting. MA: quality rating. MK: narrative synthesis. SS and AL: manuscript drafting and data curation. SW: conceptualization, article electronic search, articles screening, manuscript drafting, and project supervision. All authors had full access to the data and are in general agreement with the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding

The work of UB and AC was supported by the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government and InnoHK.

Conflict of Interest

UB and AC were employed by the Centre for Eye and Vision Research (CEVR) Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.814981/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Liu Y-C, Kuo R-L, Shih S-R. COVID-19: the first documented coronavirus pandemic in history. Biomed J. (2020) 43:328–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.04.007

2. Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Indian J Pediatr. (2020) 87:281–6. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6

3. WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. (2021). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed September 19, 2021).

4. Huremović D. Brief history of pandemics (pandemics throughout history). In: Psychiatry of Pandemics. Springer (2019).p. 7–35.

5. Sahoo JP, Mishra AP, Samal KC. Triple mutant bengal strain (B. 1618) of coronavirus and the worst COVID outbreak in India. Biotica Research Today. (2021) 3:261−5.

6. Pak A, Adegboye OA, Adekunle AI, Rahman KM, McBryde ES, Eisen DP. Economic consequences of the COVID-19 outbreak: the need for epidemic preparedness. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:241. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00241

7. Ntoumi F, Velavan TP. COVID-19 in Africa: between hope and reality. Lancet Infect Dis. (2021) 21:315. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30465-5

8. STATISTICA. Distribution of the Global Population 2021, by Continent. (2021). Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/237584/distribution-of-the-world-population-by-continent/ (accessed November 1, 2021).

9. Oleribe OO, Momoh J, Uzochukwu BS, Mbofana F, Adebiyi A, Barbera T, et al. Identifying key challenges facing healthcare systems in Africa and potential solutions. Int J Gen Med. (2019) 12:395. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S223882

10. Mooketsane KS, Phirinyane MB. Health governance in sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Soc Policy. (2015) 15:345–8. doi: 10.1177/1468018115600123d

11. Kola L. Global mental health and COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:655–7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30235-2

12. El-Sadr WM, Justman J. Africa in the path of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:e11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008193

13. Arora T, Grey I, Östlundh L, Lam KBH, Omar OM, Arnone D. The prevalence of psychological consequences of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Health Psychol. (2020) 27:805–24. doi: 10.1177/1359105320966639

14. Afolabi A. Mental health implications of lockdown during coronavirus pandemic among adults resident in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Soc Work. (2020) 10:50–8.

15. Cénat JM, Dalexis RD, Guerrier M, Noorishad P-G, Derivois D, Bukaka J, et al. Frequency and correlates of anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in low-and middle-income countries: a multinational study. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 132:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.09.031

16. De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, Grindle M, Munoz S-A, Ellis L, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3

17. Dutta A, Sharma A, Torres-Castro R, Pachori H, Mishra S. Mental health outcomes among health-care workers dealing with COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. (2021) 63:335. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1029_20

18. Olashore AA, Akanni OO, Fela-Thomas AL, Khutsafalo K. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on health-care workers in African Countries: a systematic review. Asian J Soc Health Behav. (2021) 4:85. doi: 10.4103/shb.shb_32_21

19. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 59:1218–39. e1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

20. Shorey SY, Ng ED, Chee CY. Anxiety and depressive symptoms of women in the perinatal period during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Public Health. (2021) 49:730–40. doi: 10.1177/14034948211011793

21. Necho M, Tsehay M, Birkie M, Biset G, Tadesse E. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2021) 67:892–906. doi: 10.1177/00207640211003121

22. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. (2021) 88:372. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

23. Paez A. Gray literature: an important resource in systematic reviews. J Evid Based Med. (2017) 10:233–40. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12266

24. Kaptein S, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU. Association between cardiovascular diseases and mobility in persons with lower limb amputation: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. (2018) 40:883–8. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1277401

25. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. (2006) 1:b92.

26. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. (2010) 1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12

27. Arafa A, Mohamed A, Saleh L, Senosy S. Psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the public in Egypt. Commun Ment Health J. (2021) 57:64–9. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00701-9

28. Belayachi J, Benammi S, Chippo H, Bennis RN, Madani N, Hrora A, et al. Healthcare workers psychological distress at early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Morocco. medRxiv. (2021). doi: 10.1101/2021.02.02.21250639

29. Fodjo JNS, Ngarka L, Njamnshi WY, Nfor LN, Mengnjo MK, Mendo EL, et al. Fear and depression during the COVID-19 outbreak in Cameroon: a nation-wide observational study. BMC Psychiatry. (2021) 21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03323-x

30. Idowu OM, Adaramola OG, Aderounmu BS, Olugbamigbe ID, Dada OE, Osifeso CA, et al. A gender comparison of the psychological distress of medical students in Nigeria during the Coronavirus pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.11.08.20227967

31. Mudiriza G, De Lannoy A. Youth Emotional Well-being During the COVID-19-Related Lockdown in South Africa. Cape Town: SALDRU (2020).

32. Ojewale LY. Psychological state and family functioning of University of Ibadan students during the COVID-19 lockdown. medRxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.07.09.20149997

33. Dyer J, Wilson K, Badia J, Agot K, Neary J, Njuguna I, et al. The psychosocial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth living with HIV in Western Kenya. AIDS Behav. (2021) 25:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03005-x

34. Cénat JM, Noorishad P-G, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Dalexis RD, Hajizadeh S, Guerrier M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and the major role of stigmatization in low-and middle-income countries: a multinational cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. (2021) 297:113714. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113714

35. Eisenbeck N, Pérez-Escobar JA, Carreno DF. Meaning-centered coping in the era of COVID-19: direct and moderating effects on depression, anxiety, and stress. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:667. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648383

36. Olashore AA, Akanni OO, Oderinde KO. Neuroticism, resilience, and social support: correlates of severe anxiety among hospital workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria and Botswana. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06358-8

37. Alzueta E, Perrin P, Baker FC, Caffarra S, Ramos-Usuga D, Yuksel D, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: a study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol. (2021) 77:556–70. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23082

38. Langsi R, Osuagwu UL, Goson PC, Abu EK, Mashige KP, Ekpenyong B, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with mental and emotional health outcomes among africans during the COVID-19 lockdown period—A web-based cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:899. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030899

39. Lamptey E. Psychological impacts of COVID-19 on health professionals: a cross-sectional survey of 1000 nurses across ECOWAS countries. Res J Med Health Sci. (2020) 1:22–33.

40. Alenko A, Agenagnew L, Beressa G, Tesfaye Y, Woldesenbet YM, Girma S. COVID-19-related anxiety and its association with dietary diversity score among health care professionals in Ethiopia: a web-based survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2021) 14:987. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S305164

41. Anikwe CC, Ogah CO, Anikwe IH, Ewah RL, Onwe OE, Ikeoha1c CC. Coronavirus 2019 pandemic: assessment of the level of knowledge, attitude, and anxiety among pregnant women in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. (2021) 11:1267–73.

42. Birhanu A, Tiki T, Mekuria M, Yilma D, Melese G, Seifu B. COVID-19-induced anxiety and associated factors among urban residents in West Shewa Zone, Central Ethiopia, 2020. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:99. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S298781

43. Al Omari O, Al Sabei S, Al Rawajfah O, Abu Sharour L, Aljohani K, Alomari K, et al. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of depression, anxiety, and stress among youth at the time of COVID-19: an online cross-sectional multicountry study. Depress Res Treat. (2020). doi: 10.1155/2020/8887727

44. Aylie NS, Mekonen MA, Mekuria RM. The psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic among university students in Bench-Sheko Zone, South-west Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2020) 13:813. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S275593

45. Fekih-Romdhane F, Cheour M. Psychological distress among a Tunisian community sample during the COVID-19 pandemic: correlations with religious coping. J Relig Health. (2021) 60:1446–61. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01230-9

46. Ghazawy ER, Ewis AA, Mahfouz EM, Khalil DM, Arafa A, Mohammed Z, et al. Psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on the university students in Egypt. Health Promot Int. (2020) 36:1116–25. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa147

47. Jemal K, Deriba BS, Geleta TA, Tesema M, Awol M, Mengistu E, et al. Self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress among healthcare workers in Ethiopia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2021) 17:1363. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S306240

48. Kassaw C, Pandey D. The current mental health crisis of COVID-19 pandemic among communities living in Gedeo Zone Dilla, SNNP, Ethiopia, April 2020. J Psychosoc Rehabil Mental Health. (2021) 8:5–9. doi: 10.1007/s40737-020-00192-7

49. Kassaw C. The magnitude of psychological problem and associated factor in response to COVID-19 pandemic among communities living in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, March 2020: a cross-sectional study design. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2020) 13:631. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S256551

50. Khalaf OO, Khalil MA, Abdelmaksoud R. Coping with depression and anxiety in Egyptian physicians during COVID-19 pandemic. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. (2020) 27:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s43045-020-00070-9

51. Mekonen SB, Muluneh N. The psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak on nurses working in the Northwest of Amhara Regional State Referral Hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2020) 13:1353. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S291446

52. Mekonen BS, Ali MS, Muluneh NY. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on graduating class students at the University of Gondar, northwest Ethiopia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:109. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S300262

53. Ofori AA, Osarfo J, Agbeno EK, Manu DO, Amoah E. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on health workers in Ghana: a multicentre, cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. (2021) 9:20503121211000919. doi: 10.1177/20503121211000919

54. Youssef N, Mostafa A, Ezzat R, Yosef M, El Kassas M. Mental health status of health-care professionals working in quarantine and non-quarantine Egyptian hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. East Mediterr Health J. (2020) 26:1155–64. doi: 10.26719/emhj.20.116

55. Sahile AT, Ababu M, Alemayehu S, Abebe H, Endazenew G, Wubshet M, et al. Prevalence and severity of depression, anxiety, and stress during pandemic of COVID-19 among college students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2020: a cross sectional survey. Int J Clin Exp Med Sci. (2020) 6:126. doi: 10.11648/j.ijcems.20200606.13

56. Sediri S, Zgueb Y, Ouanes S, Ouali U, Bourgou S, Jomli R, et al. Women's mental health: acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Arch Womens Mental Health. (2020) 23:749–56. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01082-4

57. Agberotimi SF, Akinsola OS, Oguntayo R, Olaseni AO. Interactions between socioeconomic status and mental health outcomes in the nigerian context amid covid-19 pandemic: a comparative study. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:2655. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559819

58. Elamin MM, Hamza SB, Abdalla YA, Mustafa AAM, Altayeb MA, Mohammed MA, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health professionals in Sudan 2020. Sudan J Med Sci. (2020) 15:54–70. doi: 10.18502/sjms.v15i5.7136

59. El Desouky ED, Fakher W, El Hawary ASA, Salem MR. Anxiety and depression among Egyptians during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study. J Psychol Afr. (2021) 31:109–16. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2021.1910414

60. Jemal K, Deriba BS, Geleta TA. Psychological distress, early behavioral response, and perception toward the COVID-19 pandemic among health care workers in North Shoa Zone, Oromiya Region. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:628898. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.628898

61. Kassawa C, Ali Y. Magnitude of generalized anxiety among health professionals working on Covid-19 at Dilla Referral Hospital Dilla, Ethiopia. Asian J Adv Med Sci. (2020) 2:13–20.

62. Kassawa C, Pandey D. The prevalence of general anxiety disorder and its associated factors among women's attending at the perinatal service of Dilla University referral hospital, Dilla town, Ethiopia, April, 2020 in Covid pandemic. Heliyon. (2020) 6:e05593. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05593

63. Kounou KB, Guédénon KM, Foli AAD, Gnassounou-Akpa E. Mental health of medical professionals during the Covid-19 pandemic in Togo. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020). doi: 10.1111/pcn.13108

64. Okwaraji FE, Onyebueke GC. A cross sectional study on the mental health impacts of Covid-19 pandemic in a sample of Nigerian Urban Dwellers. Int Neuropsychiatr Dis J. (2021) 15:28–36. doi: 10.9734/indj/2021/v15i430161

65. Olaseni AO, Akinsola OS, Agberotimi SF, Oguntayo R. Psychological distress experiences of Nigerians during Covid-19 pandemic; the gender difference. Soc Sci Human Open. (2020) 2:100052. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100052

66. Mudenda S, Mukosha M, Mwila C, Saleem Z, Kalungia AC, Munkombwe D, et al. Impact of the coronavirus disease on the mental health and physical activity of pharmacy students at the University of Zambia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. (2021) 10:324. doi: 10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20211010

67. Necho M, Birkie M, Gelaye H, Beyene A, Belete A, Tsehay M. Depression, anxiety symptoms, Insomnia, and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic period among individuals living with disabilities in Ethiopia, 2020. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0244530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244530

68. Onchonga D, Ngetich E, Makunda W, Wainaina P, Wangeshi D. Anxiety and depression due to 2019 SARS-CoV-2 among frontier healthcare workers in Kenya. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e06351. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06351

69. AlKalasha SH, Kasemy ZA. Anxiety, depression, and commitment to infection control measures among Egyptians during COVID-19 pandemic. Menoufia Med J. (2020) 33:1410.

70. Sagaon-Teyssier L, Kamissoko A, Yattassaye A, Diallo F, Castro DR, Delabre R, et al. Assessment of mental health outcomes and associated factors among workers in community-based HIV care centers in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in Mali. Health Policy Open. (2020) 1:100017. doi: 10.1016/j.hpopen.2020.100017

71. Elhadi M, Buzreg A, Bouhuwaish A, Khaled A, Alhadi A, Msherghi A, et al. Psychological impact of the civil war and COVID-19 on Libyan medical students: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:2575. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.570435

72. Elkholy H, Tawfik F, Ibrahim I, Salah El-din W, Sabry M, Mohammed S, et al. Mental health of frontline healthcare workers exposed to COVID-19 in Egypt: a call for action. Int J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 67:522–31. doi: 10.1177/0020764020960192

73. Msherghi A, Alsuyihili A, Alsoufi A, Ashini A, Alkshik Z, Alshareea E, et al. Mental health consequences of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.605279

74. Teshome A, Glagn M, Shegaze M, Tekabe B, Getie A, Assefa G, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder and its associated factors among health care workers fighting COVID-19 in southern Ethiopia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2020) 13:907. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S282822

75. Tobin E, Okogbenin E, Obi A. A population-based cross-sectional study of anxiety and depression associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Cent Afr J Public Health. (2021) 7:127–35. doi: 10.11648/j.cajph.20210703.16

76. Keubo FRN, Mboua PC, Tadongfack TD, Tchoffo EF, Tatang CT, Zeuna JI, et al. Psychological distress among health care professionals of the three COVID-19 most affected Regions in Cameroon: prevalence and associated factors. Ann Méd Psychol Rev Psychiatr. (2021) 179:141–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amp.2020.08.012

77. Abdelghani M, El-Gohary HM, Fouad E, Hassan MS. Addressing the relationship between perceived fear of COVID-19 virus infection and emergence of burnout symptoms in a sample of Egyptian physicians during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Middle East Current Psychiatry. (2020) 27:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s43045-020-00079-0

78. Elhadi M, Msherghi A, Elgzairi M, Alhashimi A, Bouhuwaish A, Biala M, et al. The mental well-being of frontline physicians working in civil wars under coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic conditions. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 11:598720. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.598720

79. Hajure M, Tariku M, Mohammedhussein M, Dule A. Depression, anxiety and associated factors among chronic medical patients amid COVID-19 pandemic in Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Mettu, Ethiopia, 2020. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2020) 16:2511. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S281995

80. Elhadi M, Msherghi A, Elgzairi M, Alhashimi A, Bouhuwaish A, Biala M, et al. Psychological status of healthcare workers during the civil war and COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. (2020) 137:110221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110221

81. Idrissi AJ, Lamkaddem A, Benouajjit A, El Bouaazzaoui MB, El Houari F, Alami M, et al. Sleep quality and mental health in the context of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown in Morocco. Sleep Med. (2020) 74:248–53. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.07.045

82. Madani A, Boutebal SE, Bryant CR. The psychological impact of confinement linked to the coronavirus epidemic COVID-19 in Algeria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3604. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103604

83. El-Zoghby SM, Soltan EM, Salama HM. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and social support among adult Egyptians. J Community Health. (2020) 45:689–95. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00853-5

84. Tesfaye Y, Agenagnew L, Anand S, Tucho GT, Birhanu Z, Ahmed G, et al. Mood symptoms, suicide, and associated factors among Jimma community. A cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:248. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.640575

85. Ejeh FE, Owoicho S, Saleh AS, Madukaji L, Okon KO. Factors associated with preventive behaviors, anxiety among healthcare workers and response preparedness against COVID-19 outbreak: a one health approach. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. (2021) 10:100671. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.11.004

86. Meji MA, Dennison MS. Survey on general awareness, mental state and academic difficulties among students due to COVID-19 outbreak in the western regions of Uganda. Heliyon. (2020) 6:e05454. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05454

87. Odikpo LC, Abazie HO, Emon D, Mobolaji-Olajide MO, Gbahabo DD, Musa-Malikki A. Knowledge and reasons for anxiety among nurses towards COVID-19 in Nigeria. Afr J Infect Dis. (2021) 15:16. doi: 10.21010/ajid.v15i2.4

88. Rakhmanov O, Dane S. Knowledge and anxiety levels of African university students against COVID-19 during the pandemic outbreak by an online survey. J Res Med Dental Sci. (2020) 8:53–6.

89. Rakhmanov O, Demir A, Dane S. A brief communication: anxiety and depression levels in the staff of a Nigerian private university during COVID 19 pandemic outbreak. J Res Med Dent Sci. (2020) 8:118–22.

90. Rakhmanov O, Shaimerdenov Y, Dane S. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety in secondary school students. J Res Med Dental Sci. (2020) 8:186–90.

91. Akorede S, Ajayi A, Toyin A, Uwadia G. Influence of COVID-19 on the psychological wellbeing of tertiary institution students in Nigeria. Tanzania J Sci. (2021) 47:70–9. doi: 10.4103/mmj.mmj_245_20

92. Aluh DO, Mosanya AU, Onuoha CL, Anosike C, Onuigbo EB. An assessment of anxiety towards COVID-19 among Nigerian general population using the Fear of COVID-19 scale. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. (2021) 1:36–43. doi: 10.12740/APP/129705

93. Moyer CA, Sakyi KS, Sacks E, Compton SD, Lori JR, Williams JE. COVID-19 is increasing Ghanaian pregnant women's anxiety and reducing healthcare seeking. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. (2021) 152:444–5. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13487

94. Boateng GO, Doku DT, Enyan NIE, Owusu SA, Aboh IK, Kodom RV, et al. Prevalence and changes in boredom, anxiety and well-being among Ghanaians during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based study. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10998-0

95. Eweida RS, Desoky GM, Khonji LM, Rashwan ZI. Mental strain and changes in psychological health hub among intern-nursing students at pediatric and medical-surgical units amid ambience of COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive survey. Nurse Educ Pract. (2020) 49:102915. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102915

96. Kibret S, Teshome D, Fenta E, Hunie M, Tamire T. Prevalence of anxiety towards COVID-19 and its associated factors among healthcare workers in a Hospital of Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0243022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243022

97. Arafa A, Mohammed Z, Mahmoud O, Elshazley M, Ewis A. Depressed, anxious, and stressed: what have healthcare workers on the frontlines in Egypt and Saudi Arabia experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Affect Disord. (2021) 278:365–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.080

98. Kim AW, Nyengerai T, Mendenhall E. Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms in urban South Africa. Psychol Med. (2020) 1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003414

99. Amir K, Lucas A. Depression and associated factors among refugees amidst covid-19 in nakivale refugee camp in Uganda. J Neurol Res Rev Rep. (2021) 3:1–5. doi: 10.47363/JNRRR/2021(3)132

100. Pillay L, van Rensburg DCCJ, van Rensburg AJ, Ramagole DA, Holtzhausen L, Dijkstra HP, et al. Nowhere to hide: the significant impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) measures on elite and semi-elite South African athletes. J Sci Med Sport. (2020) 23:670–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2020.05.016

101. Sanusi YM, Oluwaseun OR, Ayotola KK, Damilola OD. Depressive Effect of COVID-19 Lockdown in South-Western Nigeria. Lagos; Oyo; Ogn; Osun; Ondo; Ekiti: Benin Journal of Social Work and Community Development (2021).

102. Tadesse DB, Gebrewahd GT, Demoz GT. Knowledge, attitude, practice and psychological response toward COVID-19 among nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in northern Ethiopia, 2020. New Microbes New Infect. (2020) 38:100787. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100787

103. Chen J, Farah N, Dong RK, Chen RZ, Xu W, Yin J, et al. Mental health during the COVID-19 crisis in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10604. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010604

104. Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med. (2013) 43:897–910. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200147X

105. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686

106. Friedrich MJ. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA. (2017) 317:1517. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3826

107. Bareeqa SB, Ahmed SI, Samar SS, Yasin W, Zehra S, Monese GM, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in china during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. (2021) 56:210–27. doi: 10.1177/0091217420978005

108. Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382

109. Hossain MM, Rahman M, Trisha NF, Tasnim S, Nuzhath T, Hasan NT, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in South Asia during COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e06677. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06677

110. Rothstein MA, Parmet WE, Reiss DR. Employer-mandated vaccination for COVID-19. Am J Public Health. (2021) 111:1061–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306166

111. Forman R, Shah S, Jeurissen P, Jit M, Mossialos E. COVID-19 vaccine challenges: what have we learned so far and what remains to be done? Health Policy. (2021) 125:553–67. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.03.013

113. Abaluck J, Kwong LH, Styczynski A, Haque A, Kabir MA, Bates-Jefferys E, et al. (2021). Normalizing Community Mask-Wearing: A Cluster Randomized Trial in Bangladesh (No. w28734). National Bureau of Economic Research (2021).

Keywords: Africa, COVID-19, pandemics, anxiety, depression

Citation: Bello UM, Kannan P, Chutiyami M, Salihu D, Cheong AMY, Miller T, Pun JW, Muhammad AS, Mahmud FA, Jalo HA, Ali MU, Kolo MA, Sulaiman SK, Lawan A, Bello IM, Gambo AA and Winser SJ (2022) Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Among the General Population in Africa During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 10:814981. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.814981

Received: 14 November 2021; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 17 May 2022.

Edited by:

Mohammed A. Mamun, CHINTA Research Bangladesh, BangladeshReviewed by:

Mark Mohan Kaggwa, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, UgandaJavier Santabarbara, University of Zaragoza, Spain

Ram Bajpai, Keele University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Bello, Kannan, Chutiyami, Salihu, Cheong, Miller, Pun, Muhammad, Mahmud, Jalo, Ali, Kolo, Sulaiman, Lawan, Bello, Gambo and Winser. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Umar Muhammad Bello, dW1hci5tLmJlbGxvQGNvbm5lY3QucG9seXUuaGs=; Allen M. Y. Cheong, YWxsZW4ubXkuY2hlb25nQHBvbHl1LmVkdS5oaw==

Umar Muhammad Bello

Umar Muhammad Bello Priya Kannan3

Priya Kannan3 Muhammad Chutiyami

Muhammad Chutiyami Dauda Salihu

Dauda Salihu Allen M. Y. Cheong

Allen M. Y. Cheong Tiev Miller

Tiev Miller Abdullahi Salisu Muhammad

Abdullahi Salisu Muhammad Stanley John Winser

Stanley John Winser