- 1James Cook University, College of Medicine and Dentistry, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 2Queensland Health, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 3Northern Territory Health, Darwin, NT, Australia

As life expectancy increases for Indigenous populations, so does the number of older adults with complex, chronic health conditions and age-related geriatric syndromes. Many of these conditions are associated with modifiable lifestyle factors that, if addressed, may improve the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples as they age. If models of healthy aging are to be promoted within health services, a clearer understanding of what aging well means for Indigenous peoples is needed. Indigenous peoples hold a holistic worldview of health and aging that likely differs from Western models. The aims of this review were to: investigate the literature that exists and where the gaps are, on aging well for Indigenous peoples; assess the quality of the existing literature on Indigenous aging; identify the domains of aging well for Indigenous peoples; and identify the enablers and barriers to aging well for Indigenous peoples. A systematic search of online databases, book chapters, gray literature, and websites identified 32 eligible publications on Indigenous aging. Reflexive thematic analysis identified four major themes on aging well: (1) achieving holistic health and wellbeing; (2) maintaining connections; (3) revealing resilience, humor, and a positive attitude; and (4) facing the challenges. Findings revealed that aging well is a holistic concept enabled by spiritual, physical, and mental wellbeing and where reliance on connections to person, place, and culture is central. Participants who demonstrated aging well took personal responsibility, adapted to change, took a positive attitude to life, and showed resilience. Conversely, barriers to aging well arose from the social determinants of health such as lack of access to housing, transport, and adequate nutrition. Furthermore, the impacts of colonization such as loss of language and culture and ongoing grief and trauma all challenged the ability to age well. Knowing what aging well means for Indigenous communities can facilitate health services to provide culturally appropriate and effective care.

Introduction

The population worldwide is aging dramatically, with estimates that by 2050 the number of people aged 80 years and over will be more than 426 million, triple that of population numbers in 2020 (1). Moreover, for the first time in history, most people can expect to live into their sixties and beyond (2, 3). Increased longevity can potentially enable older adults to remain engaged for longer, resulting in positive outcomes for the individual, their families, and society as a whole. However, increasing longevity is not always associated with extended periods of good health. Epidemiological evidence indicates global health outcomes are not improving equitably, and quality of life during these extra years is unclear (2, 3). For those living with functional decline and disability, there is an increased demand on health and social care, and limitations on contributions they can make to society (3). Increased prevalence of geriatric syndromes, related to frailty, cognitive impairment, incontinence, delirium, and falls, compromise independence and increase demand for health and aged care services (4).

For Indigenous peoples, there is an increased prevalence of chronic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory disease (5–8). Furthermore, age-related conditions such as dementia are more prevalent in Indigenous populations and affect people at a younger age (9–12). The number of Indigenous peoples is growing (13, 14) and for many Indigenous populations, life expectancy is increasing (15). Greater proportions of Indigenous peoples over 65 years are surviving into older age (16–20). As these populations age, there may be a higher number of older adults with complex, chronic health conditions and geriatric syndromes such as falls and frailty. However, many of the problems of aging and chronic conditions are associated with lifestyle factors and are amenable to interventions that have the potential to improve the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples as they age.

Health is a holistic concept within Indigenous communities (21, 22). The connection to land is central to wellbeing and spiritual, environmental, ideological, political, social, economic, mental, and physical factors all play interrelated roles in wellbeing (23). When any of these factors are disrupted, ill health is likely to occur (23). Indigenous peoples therefore hold a different worldview where the concept of self is collectivist and inseparable from land, family, and community, and this view is likely to be significant in their concept of aging well.

Concepts of Aging Well

The concept of aging well has been given considerable attention in the literature. “Aging well” is often defined synonymously with “successful ageing,” “positive ageing,” “good old age,” “active ageing,” “robust ageing,” “healthy ageing,” “productive ageing,” “vital ageing,” and “optimal ageing,” with definitions and measurements of these varying significantly (24–35). Rowe and Kahn (36, 37) are frequently cited for introducing the concept of “successful ageing,” and their model is one of the most widely used in the scientific literature (26, 27, 30, 31, 34, 38, 39). Despite its widespread use, the term “successful ageing” has generated criticism. “Success” is often associated with economic or material achievement, especially in a Western culture where the ideal of success is reflected in the lifestyles of the fortunate elite. Those who have been able to make made positive life decisions, such as financial planning and adherence to health promotion advice, are rewarded, and those who find themselves in less favorable circumstances often experience blame or neglect. The concept of success or failure to categorize aging promotes the notion of winners and losers, rather than successful aging being on a continuum of achievement (24, 28, 29, 32, 39, 40).

The model of successful aging posited by Rowe and Khan (36) is based on three criteria: (i) freedom from disease and disability; (ii) high cognitive and physical functioning; and (iii) active engagement with life. These criteria place an emphasis on maintaining physical health and avoiding disease. However, this approach has been criticized for being a medically-orientated model which: (i) neglects social relationships and engagements (41–43); (ii) underestimates the influence of contextual factors (35, 41, 44, 45); (iii) is oblivious to cultural differences (35, 40, 41, 43, 46); (iv) ignores the interactions between individuals and their environments (43–45); (v) overlooks mental wellbeing (38, 43); (vi) fails to take into account the disadvantages that accumulate over the life course (25, 29, 40, 43–45); (vii) fails to consider the developmental process throughout the individual's lifespan (25, 29, 40, 43, 46); and (viii) does not acknowledge that successful aging is possible for those with chronic disease or disabilities (29, 38, 41–43, 45). Incorporating broader, non-medical perspectives in models of aging well can enhance theoretical definitions and enable more individual- and community-centered definitions of aging well to emerge. Studies that have encompassed lay perspectives found non-medical models of aging well to be multidimensional, with a greater focus on adaptation, meaningfulness, and connection, and provide insight into what older people value (25, 26, 29, 30, 33, 41, 42, 47). Knowing how aging well is expressed within particular communities allows health and social care providers to provide the most appropriate health care (33). It is therefore imperative that aging well is considered from a cultural perspective.

Dimensions of aging well for different cultural groups have been explored across the literature. Prior research overwhelmingly reports that older people's norms, perceptions, and self-awareness of the reality of aging differ across cultures, making aging well culture-dependent (28, 29, 44, 48). Hung and colleagues (28) compared the concept of healthy aging from Western and non-Western cultural perspectives, as well as between academics and lay older persons. They found older people from non-Western cultures held a more holistic view of healthy aging, which extended beyond functional independence, and included domains such as family, adaptation to age-related changes, financial security, personal growth, positive spirituality, and positive outlook. The authors suggested attitudes and behaviors relevant for healthy aging are greatly influenced by traditions, religious beliefs, and values derived from different individual cultural backgrounds, yet current academic definitions of healthy aging seem to be independent of cultural identity. Amin (41) explored successful aging from older adults' perspectives in Bangladesh and found, similarly to Hung and colleagues (28), that successful aging encompassed dimensions such as adaptations to one's changing body, financial security, religiosity, age identity, and social engagement. Amin (41) found that older adults' emphasis on these dimensions, however, was qualitatively different from those identified as relevant in Western societies, and that family relationships played a strong role in aging success—something often neglected in Western models.

Although some domains of aging well, such as physical health and economic wealth, may be consistent across cultures, their relative contributions to wellbeing vary. Other more culturally situated values, such as transferring cultural knowledge or participating in cultural activities, may hold greater importance in certain cultures (29, 34). Incorporating perspectives from different cultural settings will facilitate construction of a more comprehensive, culturally appropriate definition of aging well, which would be more realistic and useful for the community in which it is developed (28). Additionally, an understanding of aging well may support both health and social care systems to be better aligned to integrate services that support a holistic view of functioning and healthy aging (3). If models of healthy aging are to be promoted within health and social care services, there needs to be a clearer understanding of what aging well means for Indigenous peoples. This is particularly significant for Indigenous people where healthy aging may not be easily achieved (7, 49).

Purpose of Review

This review was conducted as part of the lead author's PhD study to develop and implement a framework for aging well in the Torres Strait in Far North Queensland, Australia. The islands of the Torres Strait are located between the northern tip of Australia and Papua New Guinea. There are over 100 islands with Torres Strait Islanders permanently living in 18 island communities and two mainland communities on the Northern Peninsula Area (the northern most tip of Australia) (50). Torres Strait Islander peoples are a culturally distinct First Nation population in Australia, predominately of Melanesian ethnicity but due to the settlement of traders, explorers, and colonizers have a diverse and mixed ancestry (50). Torres Strait Islander peoples are sea-faring people whose culture has been influenced by peoples from Australia, Papua, and the Austronesian region (51). Early Torres Strait life was based on subsistence living with communal life revolving around hunting, fishing, gardening, and trading. Fishing remains the main economic activity across the region (50). The PhD study, to collaborate with local primary health care centers in the Torres Strait region to develop an aging well framework, follows a longstanding research and clinical partnership with local health services and community groups. Community members expressed a desire to examine what aging well meant for their older adults and how they could be supported to age well into the future. The findings of this review were used to assist with analysis of local needs and priorities.

Scope and Aims of Review

Globally, there are between 370 and 500 million Indigenous peoples who live in over 90 countries (8). Within specific Indigenous populations, there are often different cultural groups, each with distinct culture, language, beliefs, and practices. This scoping review included articles relating to many Indigenous populations, each with preferred terminology when referring to their people. The lead author of the review is a non-Indigenous clinical researcher supported by a wider research team and advisory panel of Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics, researchers, and clinicians. Together, the author group respectfully agreed that using the term Indigenous throughout the review would be inclusive to all participants across all studies.

Aspects of aging well relating to specific Indigenous groups have been documented, and a scoping review has been conducted on exploring successful aging amongst North American older Indigenous peoples (52). However, no systematic review has been conducted to explore similarities across wider Indigenous populations. The intent of this paper is not to suggest all Indigenous peoples hold the same perspectives of aging well and that a generic Indigenous model of aging well can be developed. The aims of this scoping review were to: (i) explore what aging well means for different Indigenous populations; (ii) compare concepts of aging well for these populations with non-Indigenous perceptions; and (iii) identify gaps in the literature on aging well for Torres Strait Islander populations to inform further research.

The following questions were developed to meet the aims of the review:

1. What literature exists and where are the gaps on what aging well means to Indigenous peoples?

2. What is the quality of the literature on aging well for Indigenous peoples?

3. What are the domains of aging well for Indigenous peoples?

4. What are the enablers and barriers to aging well for Indigenous peoples?

Methods

A scoping review methodology was selected as the preferred approach as it allows broad concepts to be addressed, generates key concepts, and identifies gaps in the literature whilst using a structured systematic methodology (53, 54). Furthermore, scoping review methodology enables the inclusion of both qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies (53, 54). The scoping review methodology outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (53) and enhanced by Levac et al. (55), was employed. This methodology increases the rigor and reliability of review findings (53). As recommended by Levac et al. (55) and Daudt et al. (56), a quality assessment component was included in the review. The Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) (57) was applied to assess the quality of included literature. However, as scoping reviews are intended to capture a broad range of literature regardless of study design (53, 54), no studies were excluded from this review based on the quality appraisal. The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines and checklist were used to guide the reporting for this scoping review (58).

Literature Search

The search strategy included an electronic database search and a website search. Search terms from key relevant publications were reviewed to identify key words in the areas of aging and Indigenous populations. The search was broadened or focused using truncation symbols and Boolean connectors AND, OR, NOT. The following databases were searched using MeSH headings or key words: Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Emcare, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Informit. Reference lists of articles identified through searching of databases were reviewed to identify possible additional sources. A search for gray literature was conducted on the World Wide Web, on websites such as the World Health Organization and on Indigenous-specific websites, such as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Health Info Net, and the Lowitja Institute.

Study Selection

Publications identified in the search were included if they focused on perceptions, attitudes, or experiences of aging, or domains of aging well, or barriers and enablers of aging well for Indigenous peoples. Aging well and all associated terms were included; successful aging, positive aging, good old age, active aging, robust aging, healthy aging, productive aging, vital aging, optimal aging, and harmonious aging. The United Nations states that there is no formal universal definition of “Indigenous peoples” but Indigenous peoples are identified by their social, cultural, economic and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live and are frequently marginalized within their own countries (8, 59). Articles were included where participants were described as Indigenous or recognized other titles for example First Nations, Aboriginal, Māori, Alaska Natives, and American Indians.

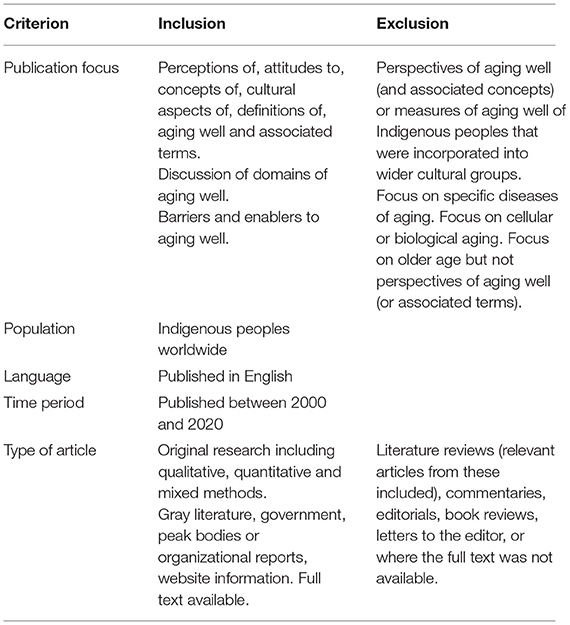

Publications identified in the searches were charted in Microsoft Excel for evaluation and eligibility assessment (54). The lead author (RQ) screened titles and abstracts using the inclusion/ exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1. Two authors (RQ, SR) independently read the full text of articles, applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and described the study characteristics. Where outcomes of eligibility assessment differed and remained unresolved after discussion, authors MRM or SL were consulted for a consensus agreement. Publication characteristics charted were source of article, year of publication, Indigenous population of study participants, aim or purpose of study, methodology including design and analysis of data, and study outcomes.

Quality Appraisal

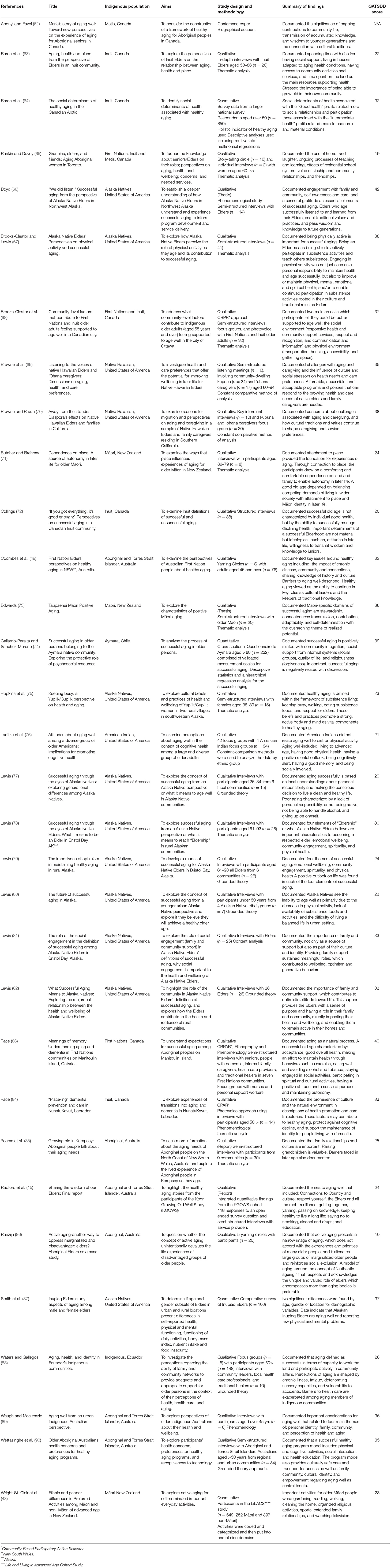

The aim of critical appraisal within a systematic review methodology is to evaluate whether the studies included in the review are accurately and completely described to assess for validity, rigor, and trustworthiness (60). Including a quality appraisal of publications within a scoping review methodology can assist with interpretation of results and facilitate the uptake of findings into policy and practice (55, 56, 61). The QATSDD is a 16-item tool that generates scores from 0 to 42 and has demonstrated good reliability and validity for use in the quality assessment of a diversity of studies, which include qualitative and quantitative work (57). Two authors, RQ and SR independently applied the tool to the 32 included studies. Where discrepancies in scores arose, consensus was reached through discussion. The scoring outcomes are included in Table 2.

Analysis

A coding framework was developed by the authors based on the literature and research questions. Data from all extracted papers were deductively coded using the framework, employing NVivo 12 qualitative data software V12 (QSR International) to manage the data. Themes were created based on the identification of patterns from the coded data through use of reflexive thematic analysis methodology (91, 92). Themes and potential domains of aging well were discussed between RQ, MRM, and SR until consensus was achieved and the final themes derived.

Results

Search Results

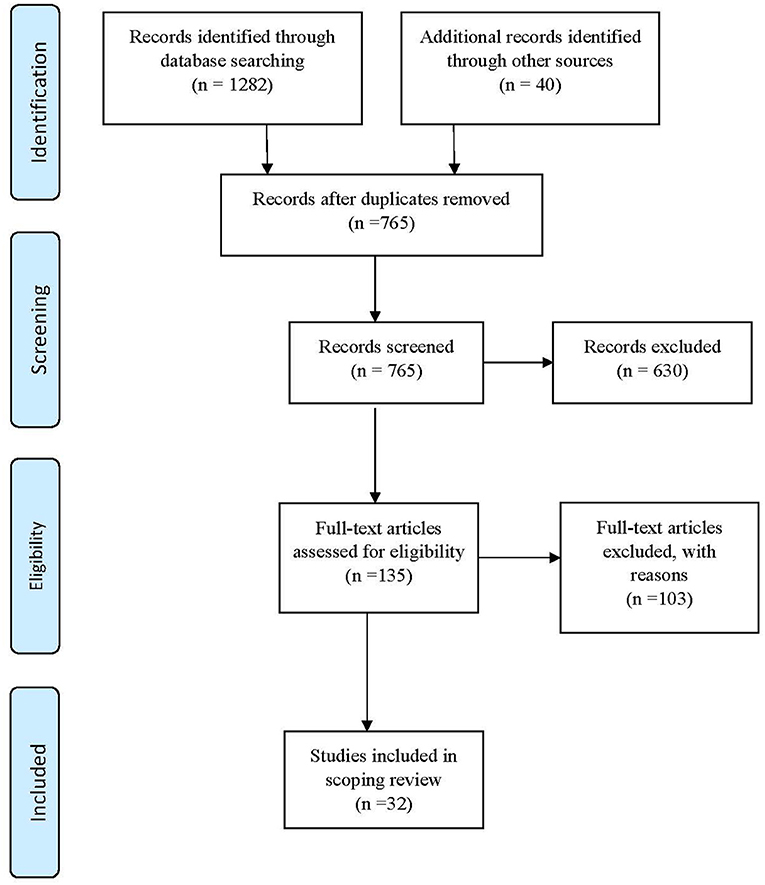

Database searching identified 1,282 potential papers with 40 articles identified through additional sources. After the exclusion of duplicates, 765 were subjected to title and abstract review. Of these, 135 publications were selected for full text review with 32 of these publications meeting the inclusion criteria and included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart (93).

Description of Studies

Table 2 provides a summary of the characteristics of the 32 included publications. The majority of the publications (n = 27) used qualitative methodology, four publications used quantitative methodology, and one publication was a biographical account. Twenty-seven articles were published in peer reviewed journals, two were published reports, and three were published theses. Indigenous populations that were the focus of the included studies were: Metis, Canada (n = 2); Inuit, Canada (n = 6); First Nations, Canada (n = 3); Alaska Natives, United States of America (USA) (n = 10); Native Hawaiian, USA (n = 2); Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Australia (n = 6); Maori, New Zealand (n = 3); Aymara, Chile (n = 1); American Indian, USA (n = 1); and Indigenous, Ecuador (n = 1).

Quality of the Included Studies

The methodological quality of the included publications was assessed from 10 through to 42 (average = 29). Whilst the biographical account (62) did not fit into a methodological framework and was therefore rated N/A, it was important to include it to ensure all Indigenous voices were heard. The three published theses (66, 73, 83) all scored highly as they included detailed methodological procedures. A common limitation of the qualitative studies was a lack of evidence to determine reliability of the analytical process (15, 49, 62, 63, 65, 75–77, 79, 80, 84–86). Other limitations noted across all study designs included lack of evidence of co-design (62, 64, 65, 72, 76, 80, 86, 88, 94), evidence of sample size considered in terms of analysis (62–65, 67–69, 71, 72, 75, 77, 81, 82, 84–86, 90, 94) and detailed recruitment data (62, 63, 69, 71, 72, 76–81, 85, 86, 94).

Synthesis of Findings

Across all Indigenous populations, there were consistently shared similarities that reflected perceptions of what aging well means for Indigenous peoples and challenges that impacted Indigenous peoples' ability to achieve good health and wellbeing in later life. Four major themes were identified: (1) achieving holistic health and wellbeing; (2) maintaining connections; (3) revealing resilience, humor, and a positive attitude; and (4) facing the challenges. These themes are interrelated, each having influence on, and being influenced by, the other themes, demonstrating that aging well is a holistic concept with reliance on connections to person, place and culture and influenced by the social determinants of health (Figure 2).

Achieving Holistic Health and Wellbeing

To achieve health and wellbeing in later life, several factors were identified that contributed to the perception of aging well. Those factors included: maintaining spirituality (15, 66, 69, 73, 74, 77–79, 83); achieving emotional wellbeing (15, 72, 73, 75, 77, 79, 80); keeping cognitively engaged (66, 73, 76, 83–85); staying active and busy (15, 49, 64, 66, 67, 73–76, 83, 87); obtaining value and respect (15, 66, 68, 73, 75, 77, 78, 89, 90); and having a sense of purpose (83, 88, 90, 94). Furthermore, the impact of the health and achievements of the wider family (71, 73, 85), being on traditional lands (15, 63, 71, 73, 80, 81, 84, 87), engaging in subsistence lifestyles (66, 67, 71, 75, 84), and accessing traditional and healthy foods (15, 66, 69, 70, 73, 75, 77, 78, 81, 83, 87) all contributed to the attainment of health and wellbeing in older age. These concepts are described in the following sub-themes of: everything healthy—mind, body and spirit; my job is done; and big stress relief when out on land. Overwhelmingly, however, it was a combination of all of these factors, along with a holistic approach to a healthy lifestyle, which contributed to holistic health and wellbeing (15, 66, 70, 72, 73, 75, 80, 83, 84, 89, 90), that is described in the sub-theme of balance—foundations for a long life.

Everything Healthy—Mind, Body, and Spirit

Having a good spirit was identified as providing a balance in life and a sense of strength (83). Through maintaining spirituality, there was a sense of guidance toward how to age well (15, 66, 73, 74, 79, 83) while alleviating worry (78), and keeping an optimistic (69) and positive attitude (15, 78).

“… one of the things that's been most important in my life has been my spirit…it is something that I had taken care of because to me it's the governing body. If I hadn't got that right, I don't think anything goes right.” [Older Maori, (73) p. 189]

Having emotional stability and being satisfied with past life decisions was viewed as an indicator of aging well (15, 72, 73). A poor mental state was reported as due to too much worry (72, 77).

“Ones that don't worry too much stay young. Ones that worry too much age faster.” [Alaskan Native Elder (79) p. 1,525]

Staying cognitively active was part of a holistic approach to aging well (66, 73), achieved through lifelong learning (15, 73) and engagement in cognitively stimulating activities (66, 73, 76, 83–85).

“I'm more into puzzles, using my head or brain to figure out things” [Older First Nations Canadian, (83) p. 68]

Physical health was viewed as important (15, 49, 66, 67, 73, 75, 83) but valued through appreciating how engagement in physical activities could provide opportunities for social connectedness (83), providing a sense of purpose (66, 73, 83, 88), improving quality of life (73, 90), promoting cultural continuity (64), and, in a practical sense, providing access to food (64). Physical activities were rarely described as formal or structured, such as visits to a gym, but were more likely to be achieved as a consequence of enacting traditional and subsistence living (64, 66, 67, 74, 75, 83), involvement in community activities (66, 76, 83, 87, 90, 94) or carrying out activities of daily living (66, 83).

“I think today most of the women are healthy for activity, physical activities. When they go berry picking, they're working using their bodies everything. When we are cutting fish, we are using everything, our muscles, lifting things” [Older Native Alaskan, (75) p. 45–6].

My Job is Done

As part of a holistic approach to aging well, obtaining recognition and respect from both family and communities was viewed as significant (15, 68, 73, 75, 77, 78, 89, 90). Having an appreciation of the wealth of knowledge and wisdom an older adult can share elicited feelings of honor and pride and made the older adults feel supported and valued in the work they do (15, 66, 73).

“…they get to feel that they are still important, that they are of value that they have something of value to still give. You know, that they're not just pushed aside. You see I'm always conversing with my older ones, you know, that their opinion is important.” [Older Maori, (73) p. 205]

Equally, the wellbeing and achievements of the wider family unit contributed to older adults' measures of aging well. The accomplishments of children and grandchildren created a sense of pride and satisfaction for the older adult (71, 73, 85).

“What makes me happy is seeing the family happy, all my family. You know all of us, all the kids. Yeah, yeah that's what makes me happy. I don't really need that much for myself” [Older Maori (71) p. 53]

Big Stress Relief When Out on Land

Being on traditional lands was found to promote wellbeing, which in turn influenced perceptions of aging well (15, 63, 71, 81, 84, 87). Not only a place of childhood memories (63), being on traditional lands also signified a symbolic connection to culture and language (15, 63, 73). There was a deep and fundamental connection to the natural environment that facilitated both health and mental balance and where continued engagement was central to aging well (15, 73, 80).

“When she's on the land too that's when her stress is all come out, like less stress, good stress relief, because that's where she pretty much grew up so it's big stress relief when she finally goes out on the land.” [Older Inuit (63) p. 140]

Several studies discussed the contribution that subsistence living made to aging well (66, 67, 71, 75, 84). A subsistence way of living was seen as a healthy way to age for several reasons including: as a way to engage with family, a means to look after the environment, opportunity to connect to the land and to connect to past generations whilst engaging in physical exercise and providing traditional food, clothing, and shelter (66, 67, 75, 84). Furthermore, participation in subsistence living gave a sense of identity and connection for the older adult to themselves and others (66).

“every spring… we start to gather off of the land and that's what keeps our Elders healthy” [Alaskan Native Elder, (67) p. 299]

Access to traditional foods also played a part in perceptions of aging well (66, 69, 70, 73, 77, 78, 81, 83, 87). Traditional foods were viewed as healthy, making both the mind and spirit strong. Food was more than nourishment, symbolizing a connection to culture through traditions and ceremonies (69).

“In years back, before I was born, I know there were elders that were very healthy and strong because they have their food, their native food, not mixed up with the kass'aq [white person] food. Although they have a hard life, they were healthy, strong, because of their native food. Seal oil, dried fish.” [Older Native Alaskan, (75) p. 46]

Balance—Foundations for a Long Life

Aging well was seen as a combination of the factors reported above and characterized by a holistic approach to living life well and being healthy (15, 66, 70, 72, 73, 75, 77, 80, 83, 84). Several studies referred to the balance in life between physical, spiritual, mental, and emotional realms (15, 77, 80, 83, 84). This often involved working hard, keeping busy, abstaining from drugs, smoking and alcohol, taking positive measures to promote and maintain health, and having an active participation in spiritual and cultural life (15, 66, 73, 75, 77, 83, 84, 89, 90).

“I live a balanced life without alcohol and drugs. I take care of myself and consciously eat healthy foods regularly, exercise, don't drink or use drugs. Live spiritually.” [Older Native Alaskan, (77) p. 391]

Maintaining Connections

Aging well was fostered by the strength of a person maintaining connections to their own identity (66), their family (15, 49, 63–66, 69, 70, 72, 73, 77, 79–83, 85, 89), friends (65, 72), the community (15, 49, 66, 73, 81–83, 89), to their culture (15, 49, 66, 70, 73, 77, 80, 84, 89), spirit (15, 65, 66, 70, 73), and traditional lands (15, 66, 67, 70, 71, 73, 84). These concepts are explored in the sub-themes of: being with my grandchildren keeps me young; people look out for each other; and it's not about age, but about knowledge and wisdom.

Being With My Grandchildren Keeps Me Young

A significant theme across studies was the importance of the connection to, and relationships with, kin, which promoted aging well (15, 49, 63–66, 69, 70, 72, 73, 77, 79–83, 85, 89). These relationships often provided the older adult with a sense of purpose in as much as they had a role within the family (66, 77, 81, 82, 85, 89) and were motivated to look after their own health in order to be able to look after their family (66, 73, 89). Participants often reported how looking after grandchildren was rewarding, and a source of joy (63, 65, 66, 73, 85, 89). The wellbeing of the wider family was fundamental to the wellbeing of the older adult (73) and the strong family ties provided opportunities for the older adult to pass on their knowledge and values (15, 66, 83), whilst taking pride in the achievements of the family (65, 83). Families also provided the emotional and physical support that facilitated the older adult staying on traditional lands, and in their own home (83).

“Being with my grandchildren keeps me young. I love having them around me. We do fun things together, like go to the socials [at an Aboriginal agency] and we smudge [which is a cleansing ritual] at home. I try to help all my grandchildren and support them as much as I can whenever they need it, but I also teach them that they cannot ask for more than they need.” [Older Aboriginal Canadian, (65) p. 58]

People Look Out for Each Other

Integration within community, or social connectedness, was associated with aging well (15, 49, 64–66, 73–78, 80–84, 90). Community involvement was demonstrated with notions of reciprocity, where these relationships provided mutual benefits (71, 73). For older adults, engagement provided an opportunity to socialize, access food, and receive community support with chores such as housework and transport (66, 82–84). In return, communities benefited from older adults sharing their knowledge, wisdom, and experience, as well as assisting the younger generations with guidance and support (15, 66, 77, 80, 82). Socialization through connecting with community gave older adults a sense of belonging, promoted friendships and opportunities to connect with friends, and provided occasions to reminisce and share memories (15, 73, 78, 84). Throughout was the underlying idea of the importance of caring for others (15, 73).

“…to be able to enjoy life is to be able to live happily with your neighbor. Without that life is not worth it really. I like meeting people and I have a great love for the community that I live in but to make that possible you've got to love the people that are living in that community with you. I like to make myself available for anything, any help that is required regardless. If I can do it, I will do it.” [Older Maori, (73) p. 207]

Conversely, separation from family, friends and community was shown to have a negative impact on mental health. Increased feelings of loneliness and isolation was perceived by participants to be a major challenge to aging well. This was magnified when close family members left the community or physical disabilities limited access to social events (63, 83, 88, 90).

It's Not About age, but About Knowledge and Wisdom

Connection to culture was a significant contributor in perceptions of aging well. This included the ability to pass on traditional values, language, beliefs, wisdom, skills, and knowledge (15, 49, 62, 64–70, 72, 73, 75, 77, 78, 81–83, 85–87, 89, 90, 94). Aging well was promoted though the valuing of older adults, enabling them to fulfill a traditional role, resulting in: a sense of purpose and pride; an identity and meaningful role; an opportunity for continued learning; a means for engaging with family and community; a connection to the natural and spirit worlds; an opportunity for reciprocity with family and community; and allowing the older adults to stay involved in physical activities (15, 49, 65, 66, 69, 72, 73, 75, 77, 81–83, 89, 90). Consequently, through their cultural leadership, the older adults felt needed and respected, had improved emotional wellbeing and optimism, had improved life satisfaction, and gained a sense of accomplishment (15, 49, 66, 73, 78, 81–83, 87, 89, 94). Furthermore, cultural leadership gave a platform to provide advocacy for Indigenous voices, strengthened community cohesiveness, and promoted overall health of the community (49, 66, 73, 89).

“…I realized I needed to take on a lot of responsibility for the way I acted and the words that I said to people. Now is the time where those my age take all of the teachings we have received and give them back to the community. The community is my extended family. They are all my children; they are all my brothers and sisters; they are the people I love. This is my power. This is what keeps me going, all these people. I really enjoy what I do! I feel great being a part of a community!” [Older Aboriginal Canadian, (65) p. 60]

Revealing Resilience, Humor, and a Positive Attitude

Elements of this theme revealed how attitude and an approach to life can impact on the perception of aging well. This includes how older adults used humor in their life (65, 66, 73, 83), demonstrated resilience (15, 65, 66, 73, 78–80, 90), maintained a positive attitude (15, 66, 72–74, 76–79, 83–85, 90), adapted to the changes they face (66, 72–75, 79, 83), and took personal responsibility for their health and wellbeing (15, 66, 73, 77, 83, 94). These concepts are described in the sub-themes of: we're lucky we can laugh at ourselves; you have just to pick yourself up and keep going; and aging well is just being who you are and believing in who you are.

We're Lucky We Can Laugh at Ourselves

Humor was used to face the realities of past and present trauma and tragedy and helped participants to maintain a positive attitude (65, 83) and cope with changes (66, 83). In this sense, humor was a form of resilience and the need to seek enjoyment was of importance (63, 73, 83).

“We're lucky we can laugh at ourselves. During my life, I remember there were so many moments of tragedy and drama. Then I look at it from another viewpoint and think, “How stupid is that?” They are all funny! It's just the whole irony of being alive. You look at it and you think, “That was my life. Good God, I could have done better!” But actually, I could have done worse. Aboriginal people can laugh and don't need to hold a grudge.” [Older Aboriginal Canadian (65) p. 52]

You Have Just to Pick Yourself Up and Keep Going

Resilience and stoicism in the face of adversity was significant across studies (15, 65, 66, 73, 78, 90). Findings highlighted how older adults were aging well, despite experiencing a variety of losses. Participants also demonstrated humility and gratitude for people they had in their lives and the abilities they retained as they aged (65, 66, 80). Having a positive attitude meant facing challenges with courage and not giving up, having a sense of purpose, keeping engaged with life, families, community, and making contributions for the good of the wider community (15, 66, 72, 73, 80, 83, 85). Furthermore, having a positive attitude toward life including demonstrating forgiveness, optimism, belief in oneself, and embracing life, were seen as factors that contributed to aging well (15, 65, 66, 72–74, 76, 78, 79, 84, 90).

“…you live simply, you live well, you live happily no matter, you are bound to have a few hiccups and some of those hiccups can be dramatic, but you have just to pick yourself up and keep going.” [Older Māori, (73) p. 217]

Conversely, negative feelings of hopelessness, depression, and worry presented challenges to aging well (74, 77, 87, 90). Three studies referred to older adults' feelings of being a burden on family and community (49, 83, 90).

Having a positive attitude also included the willingness to adjust or adapt to changes in ability or circumstances or changes in roles (66, 72–75, 79, 83). These changes were both personal changes as well as changes within the community such as consequences of assimilation or urbanization. Older adults that were seen to be aging well were able to accept the limitations of old age and make adaptions to accommodate those changes (66, 73, 74, 83, 90).

Aging Well Is Just Being Who You Are and Believing in Who You Are

Demonstrating agency and autonomy were seen as factors that promoted aging well with older adults (66, 73, 77, 79, 83, 94). This included gaining and maintaining control over their own life, exercising choice, asserting their needs, managing their own limitations, and staying independent (66, 73, 77, 79, 83). Additionally, taking personal responsibility in managing their health was highlighted. This included having self-awareness and practicing self-care, making good choices in relation to a healthy lifestyle, and taking preventative measures and practicing self-management with regard to chronic disease (15, 66, 73, 77, 94).

“Aging well in the community is just being who you are and believing in who you are.” [Older Native Alaskan, (66) p. 63]

Facing the Challenges

Several factors were documented as challenges to aging well including: access to services or health care (49, 63, 66, 68–70, 73, 83, 85, 88, 90); availability of culturally safe health programs or services (15, 49, 65, 68–70, 73, 74, 85, 86, 88–90); access to resources (63, 68–70, 85, 88, 90); transport (49, 63, 68–70, 73, 83, 85, 88, 90); housing (63, 68, 69, 85); finances (49, 69, 70, 73, 83, 85, 86, 88); and environmental adaptions (63, 68, 85). Impacts of colonization such as: grief and loss (15, 63, 65, 66, 85, 90); loss of language and culture (15, 63, 66, 72, 73, 80, 83–85, 87, 89); and historical trauma (15, 49, 65, 73, 83–86, 89, 90) were also viewed as having an effect on the ability to age well. The elements of this theme are described in the following sub-themes of: services have to be the right fit; comfort of housing and money; and loss.

Services Have to Be the Right Fit

Access to mainstream services posed several difficulties for older adults (49, 63, 66, 69, 70, 73, 83, 85, 88, 90). For those living in remote communities, location and availability of services was an issue (63, 68, 69, 88, 90). Lack of transport was frequently cited as being a barrier to service access (15, 49, 63, 68–70, 73, 83, 85, 88, 90). Additionally, older adults were often unaware of the existence services or activities in the local area often as a result of poor information provided to Indigenous communities, or lack of access to computers or Internet to search for or access existing services (63, 68, 70, 85, 88, 90).

“There are a lot of people who can help, but not knowing where to go or how to go about getting the information is difficult.” [Older Native Hawaiian, (70) p. 404]

Mainstream services were often reported as expensive and at times were viewed as alienating, promoting further marginalization of Indigenous peoples, and deterring them from accessing care and supports. By contrast, culturally safe programs and services were overwhelming perceived as more appropriate and beneficial. These tended to have a holistic approach, involve community, understand culture and language, and foster trust and respect between providers and older adults (15, 49, 65, 68–70, 73, 74, 85, 86, 88–90).

“It's important to have an Aboriginal specific program as they feel welcomed here and they see Auntie's and sisters” [Older Aboriginal Australian, (49) p. 363]

Comfort of Housing and Money

Issues with housing were significantly detrimental to the ability to age well. Factors included housing, which was poor quality, expensive, and poorly maintained, as well as a lack of availability resulting in overcrowding (63, 68, 69, 85). Houses were often poorly adapted to health conditions, requiring modifications to enable safety and ongoing independence (63, 68, 85).

“Main thing is shower is too small and needs to be modified to allow easy access for self and wife. My wife is on walking frame but she will be in a wheelchair sometime in future.” [Older Aboriginal Australian, (85) p. 40]

Better housing options were those that were affordable, safe, secure, accessible, and supportive of older adults' needs as they aged (68).

Poverty was also a challenge to aging well. Many older adults were living under substantial financial pressure. Lack of adequate finances influenced access to healthy (often more expensive) food, suitable housing, transport, medications, health care, and services (69, 70, 83, 85, 86, 88).

“I don't get enough money to buy the food I'm supposed to have…I can't buy no fruits and vegetables, they're too expensive.” [Older First Nations Canadian, (83) p. 72]

Loss

The impacts of colonization are deep and wide, and as such, aging needs to be understood through the lens of loss. Loss of family, culture, language, traditions, and land are shared between all Indigenous groups subjected to colonization. Furthermore, social disadvantage, racism, and the ongoing impact of intergenerational and current grief and trauma are all experienced realities (15, 73, 85). Loss of family members and significantly a spouse, meant grieving was an ongoing situation, which affected mental health and wellbeing (63, 65, 66, 85, 90).

“It takes a lot of coping with and getting over. It's the hardest thing to lose someone in your family. It's very hard” [Older Aboriginal Australian, (90) p. 7]

Loss of culture and traditional ways has in many cases led to a more sedentary lifestyle (72, 80, 83). Loss of the connections with family and culture was perceived to contribute to a lack of respect from the younger generation (63, 66, 72, 83, 89). Changes in work and social demands mean families spend less time together and the older adults have less opportunity to pass on their knowledge, wisdom, traditions, and language (63, 66, 72, 73, 83).

Historical trauma such as the residential school system, the stolen generations and dispossession of land has impacted on all aspects of Indigenous lives (15, 49, 63, 65, 66, 73, 83–85, 90). The consequences of this trauma are immense and for the aging participants in the reviewed studies included having a lack of a family network to provide support, loss of opportunities, loss of identity, fear and suspicion of governmental services and care—and therefore avoidance of needed supports- and lack of resources to support aging well (49, 65, 73, 83–86, 89, 90).

“Our life has been interrupted, spiritually and culturally … my people have been hurt … that affected their health. They're lost. It's the loss of their way of life … identity and their culture, their everything. And it's been taken away from them” [Older Aboriginal Australian, (89) p. 28]

Discussion

This is the first known systematic search of the literature to scope what aging well means for different Indigenous populations, to compare the described concepts of aging well across these populations, and how the concepts differed to non-Indigenous perceptions of successful aging. Gaps in the literature on aging well for Torres Strait Islander populations was also examined to inform further research.

Concepts of what constitutes aging well are similar between Indigenous and non-Indigenous older adults, with literature reporting physical and mental health, social interactions, and attitude as important for all aging populations (26, 27, 46, 95). The cultural and social determinants of health significantly influence how older adults can age well in their communities whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous (3). However, this review has revealed that from an Indigenous perspective, aging well is a more holistic concept where connections to place, person and culture are interrelated.

Aging well for Indigenous peoples was fundamentally characterized by the component of “engagement with life” proposed by Rowe and Khan, rather than by the components of “lack of illness or disability” or “high cognitive and physical function” that was also included in their model (36). For Indigenous older adults, relationships are essential to aging well (15, 66, 73). Rowe and Khan (36) described active engagement with life as maintenance of interpersonal relationships and productive activity, with interpersonal relations being described as contact with others, exchange of information, emotional support, and direct assistance. Yet for Indigenous older adults, engagement with life was epitomized through the significance of relationality and connectivity, and where interpersonal relationships were more complex. Connections were not solely to maintain contact with others but involved a connection to culture, spirit, place, and whole of community. These relationships provided direction and motivation and the community was viewed as an extension of family. In this respect, Indigenous perspectives took a collective approach to aging well and could not be viewed individually (23). The collective approach to aging well is in contrast to the Western model of successful aging that places the emphasis on the individual (36). These findings align with those described by Pace and Grenier (52), who reviewed perceptions of aging with Indigenous peoples in North America and found relationships with family and community were integral to successful aging.

The importance of connections to traditional land was a significant aspect of aging well across the majority of publications. Indigenous peoples hold a deep connection to their ancestral land and connection to land is central to Indigenous peoples' existence (96). This spiritual connection, created through relationships, is expressed through Indigenous belief and knowledge systems (96). For Indigenous older adults, wellbeing and aging are embedded in their connections to, and relationship with, land (15, 71, 73, 83). Disconnection from their traditional lands compromised health and wellbeing, and impacted on the ability to age well (71, 73, 83).

The importance of generativity- the propensity and willingness to promote the wellbeing of younger generations, contributing to the growth of the next generation—was a further determinant of aging well from an Indigenous North American perspective. The acquisition of material goods or wealth was not considered important for these Elders (65, 66, 78, 81, 82). For Indigenous peoples from across most populations, transmitting their accumulated knowledge, traditional values, and wisdom to the younger generations, and advocating for Indigenous voices, was a fundamental indicator that they had aged well. Aging well helped to establish strong futures for the next generation. Through cultural leadership and as holders of knowledge, older Indigenous adults were shown respect, and were held in high esteem by their communities. This is in contrast to Western society, which, at times, portrays a negative stereotype toward aging adults (97). Within a Western culture, aging adults are commonly depicted as a socioeconomic risk, or a burden on society, as they face frailty and decline with very little to contribute to the overall wealth of the economy (98, 99). These views may well explain why older adults living in Western societies seek to defy aging and prolong youth. In contrast Indigenous peoples report taking joy in aging, as it signifies a time in life where they garner respect and feel valued (100).

Historical and cultural context, disparities, and inequality, are significant in the assessment of aging well (101). The successful aging literature indicates that economic and social privilege facilitates aging well when measured by lack of disease and disability and the maintenance of cognitive and physical function (24, 28, 29, 43). Moreover, in the Rowe and Khan model of successful aging, the success of how well an individual ages is attributed to the individual's choices, effort, and behaviors (36). Yet, lifestyle choices and individual volition are restricted by the accumulative disadvantage across the life course (45). For Indigenous peoples, life course, specifically the impacts of colonization, and the influence of the social determinants of health were ubiquitous across the publications on their perceptions of aging well. The reviewed publications reported that poverty, lack of adequate housing and transport, and ongoing grief and loss posed a challenge to aging well for older Indigenous adults. It is documented that an accumulation of deficits (personal, social, economic, and environmental) predicts ill health and unsatisfactory aging (102). However, positive assets such as resilience, positive attitude, and approach to life, were reported as means to mitigate those negative factors and promote aging well.

This scoping review also aimed to identify gaps in the literature on aging well for specific Indigenous populations, to provide recommendations for further research. The majority of publications were situated in North America (the USA and Canada) and distinguished between their specific Indigenous populations. Whilst six publications focused on Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, all included Aboriginal perspectives only with no perspectives specific to the Torres Strait population. Torres Strait Islander peoples are a culturally distinct Indigenous group within Australia, with their own identities formed from different environmental, cultural, and historical circumstances (51). Promotion of local programs for aging well requires a context-specific approach based on the concerns that local older adults find essential to their health (103). Understanding of local needs could decrease barriers to culturally appropriate health care (103), whilst supporting a holistic view of functioning and healthy aging (3). Therefore, research that explores concepts of aging well specifically for Torres Strait Islander peoples is required, and will address a gap in the existing literature.

Implications of Findings

Access to culturally appropriate health services and support programs remain a challenge for older Indigenous adults. A range of barriers was reported including locality, transport, cost, and cultural appropriateness. To successfully engage with older Indigenous adults and achieve program objectives, culturally safe approaches to care are critical (15, 90, 104, 105). Existing health care programs often neglect the cultural safety needs of Indigenous peoples (90) and do not consider the views of the consumer using the service (106). This can result in poor access to, and perceived non-compliance with, services (90). The findings of the review suggest any aging well programs or support services should take a culturally safe, holistic, multifaceted, and whole-of-community approach. Models of aging well also need to account for the complex health conditions that arise from the inequalities across the life course and the social determinants of health that influence aging (52). Empowering individuals to recognize and build on their strengths (resilience, attitude, and approach to life), may help promote their health status and aging trajectory (102). A strengths-based approach to aging well values the skills, knowledge, and relationships to both older adults and their communities.

Limitations

This scoping review had some limitations. Only articles published in English were included, thus potentially excluding studies of Indigenous peoples from non-English speaking nations such as inclusion of Indigenous peoples from Africa, Asia, the Pacific Islands, and Europe. The databases used in the scoping review were chosen due to their wide-spread use within the Australian context. Indigenous-focused databases or websites specific to countries other than Australia, or in languages other than English, may have additional publications of relevance not identified. The majority of studies (excluding those from Ecuador and Chile) were from English-speaking nations that had a common history of colonization by Britain, although this was not an inclusion criteria. As such, this may reduce the generalisability of the findings. Further research is needed to effectively explore aging for Indigenous peoples of other continents, different languages, and those without a history of colonisiation. A further limitation arose due to differences in original research methodologies of the included studies. Differences in the importance of domains of aging well may have been influenced by specific questions asked of participants across studies. Some studies had predetermined domains of aging identified and specific topic areas, whilst other studies had more open-ended questioning formats. The application of the quality appraisal tool had its own limitations. A Western approach to appraising publications may not be suitable for all types of data—for this reason the autobiographical account was not rated but deemed valuable in adding to the understanding of aging well from an Indigenous perspective. Finally, findings synthesized from the reviewed publications were of a secondary source. As such, these findings were dependent on the rigor and trustworthiness of the primary authors in interpreting their results so that they accurately represented the voices of the Indigenous participants.

Conclusion

This scoping review presents concepts of what aging well means for different Indigenous peoples, providing an insight into how these perspectives differ from a non-Indigenous aging well model. Aging well for Indigenous peoples is a holistic concept where connections to culture, land and the wider community are integral. The literature reviewed highlighted the challenges common to Indigenous populations to achieve good health and wellbeing as they age. Gaps in perspectives from specific Indigenous populations, such as Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, has been identified, which highlights the call for locally conducted research into the specific needs of this population. Opportunities exist for health service and social support providers to develop strengths-based, culturally safe programs that better align health and social care systems to integrate services that support a holistic and positive view of aging well.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study and the details of which are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

RQ, SR, MR-M, and SL contributed to the conception and design of the study. RQ completed the literature search, led the analysis with input from SR and MR-M, and wrote the manuscript. RQ and SR reviewed all articles. MR-M and SL provided consensus where required. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Open Access publication fees paid by College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. (2018). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed September 20, 2021).

2. Beard JR, Officer A, Aravjo de C. The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet. (2016) 387:2145–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4

4. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA, Geriatric S. Clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2007) 55:780–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x

5. Reading J. The Crisis of Chronic Disease among Aboriginal Peoples: A Challenge for Public Health, Population Health and Social Policy. Victoria, BC: Centre for Aboriginal Health Research, University of Victoria (2009).

6. Jernigan VBB, Duran B, Ahn D, Winkleby M. Changing patterns in health behaviors and risk factors related to cardiovascular disease among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. (2010) 100:677–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.164285

7. LoGiudice D. The health of older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Australas J Ageing. (2016) 35:82–5. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12332

9. Russell S, Quigley R, Thompson F, Sagigi B, LoGiudice D, Smith K, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the Torres Strait. Austral J Ageing. (2020) 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12878

10. Smith K, Flicker L, Lautenschlager MD, Almeida OP, Atkinson D, Dwyer A, et al. High prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment in Indigenous Australians. Neurology. (2008) 71:1470–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000320508.11013.4f

11. Radford K, Mack HA, Draper B, Chalkley S, Daylight G, Cumming R, et al. Prevalence of dementia in urban and regional Aboriginal Australians. Alzheimer's Dement. (2015) 11:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.007

12. Warren LA, Shi Q, Young K, Borenstein A, Martiniuk A. Prevalence and incidence of dementia among indigenous populations: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. (2015) 27:1959–70. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215000861

13. Jackson Pulver K, Haswell M, Ring J, Clark W. Indigenous Health Australia, Canada, Aotearoa New Zealand, and the United States - Laying Claim to a Future That Embraces Health for Us All: World Health Report Background Paper, no 33, 2010. Geneva: Indigenous Health Australia (2010).

14. Bradley K, Smith R, Hughson J, Atkinson D, Bessarab B, Flicker L, et al. Let's CHAT (community health approaches to) dementia in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: protocol for a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Servic Res. (2020) 20:208. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4985-1

15. Radford K, Allan W, Donovan T, Delbaere K, Garvey G, Broe GA, et al. Sharing the Wisdom of Our Elders Final Report. Sydney, NSW: Neuroscience Research Australia (2019).

16. Tjepkema M, Bushnik T, Bougie E. Life expectancy of First Nations, Métis and Inuit household populations in Canada. Health Rep. (2019) 30:3–10. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x201901200001-eng

17. Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Australia's Health Series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW. (2016). Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9844cefb-7745-4dd8-9ee2-f4d1c3d6a727/19787-AH16.pdf.aspx (accessed September 20, 2021).

18. Phillips B, Daniels J, Woodward A, Blakely T, Taylor R, Morrell S. Mortality trends in Australian Aboriginal peoples and New Zealand Māori. Popul Health Metr. (2017) 15:25. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0140-6

19. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 to 2031. Cat. No. 3238.0, 2019. Canberra, ACT: ABS (2019). Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/estimates-and-projections-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release (accessed September 20, 2021).

20. Davy C, Kite E, Aitken G, Dodd G, Rigney J, Hayes J. What keeps you strong? A systematic review identifying how primary health-care and aged-care services can support the well-being of older Indigenous peoples. Austral J Ageing. (2016) 35:90–7. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12311

21. World Health Organization. The Health of Indigenous Peoples. (2007). Available online at: https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/factsheet-indigenous-healthn-nov2007-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed September 20, 2021).

22. Stephens C, Nettleton C, Porter J, Willis R, Clark S. Indigenous peoples' health—why are they behind everyone, everywhere? Lancet. (2005) 366:10–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66801-8

23. Dudgeon P, Bray A, D'Costa B, Walker R. Decolonising psychology: validating social and emotional wellbeing. Aust Psychol. (2017) 52:316–25. doi: 10.1111/ap.12294

24. Bowling A. Aspirations for older age in the 21st century: what is successful aging? Int J Aging Hum Dev. (2007) 64:263–97. doi: 10.2190/L0K1-87W4-9R01-7127

25. Carstensen G, Rosberg B, McKee KJ, Aberg AC. Before evening falls: Perspectives of a good old age and healthy ageing among oldest-old Swedish men. Archiv Gerontol Geriatr. (2019) 82:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.01.002

26. Cosco TD, Prina AM, Perales J, Stephen BCM, Brayne C. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. (2013) 3:e002710. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002710

27. Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. (2006) 14:6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc

28. Hung LW, Kempen GIJM, Vries De NK. Cross-cultural comparison between academic and lay views of healthy ageing: a literature review. Ageing Soc. (2010) 30:1373–91. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10000589

29. Martin P, Kelly N, Kahana B, Kahana E, Willcox BJ, Willcox DC, et al. Defining successful aging: a tangible or elusive concept? Gerontologist. (2015) 55:14–25. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu044

30. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Vahia IV. Successful cognitive and emotional aging. World Psychiatry. (2010) 9:78–84. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00277.x

31. McKee KJ, Schüz B. Psychosocial factors in healthy ageing. Psychol Health. (2015) 30:607–26. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2015.1026905

32. Peel N, Bartlett H, McClure R. Healthy ageing: how is it defined and measured? Austral J Ageing. (2004) 23:115–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2004.00035.x

33. Phelan EA, Larson EB. “Successful aging”—where next? J Am Geriatr Soc. (2002) 50:1306–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50324.x

34. Willcox DC, Willcox BJ, Sokolovsky J, Sakihara S. The cultural context of “successful aging” among older women weavers in a Northern Okinawan village: the role of productive activity. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2007) 22:137–65. doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9032-0

35. Torres S. Different ways of understanding the construct of successful aging: Iranian immigrants speak about what aging well means to them. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2006) 21:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9017-z

36. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful ageing. Gerontologist. (1997) 37:433–40. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.433

38. Bosch-Farre C, Garre-Olmo J, Bonmati-Tomas A, Malalgon-Aguilera MC, Gelabert-Vilella S, Fuentes-Pumarola C, et al. Prevalence and related factors of Active and Healthy Ageing in Europe according to two models: results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0206353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206353

39. Stephens C, Breheny M, Mansvelt J. Healthy ageing from the perspective of older people: a capability approach to resilience. Psychol Health. (2015) 30:715–31. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.904862

40. Dillaway HE, Byrnes M. Reconsidering successful ageing. J Appl Gerontol. (2009) 28:702–22. doi: 10.1177/0733464809333882

41. Amin I. Perceptions of successful aging among older adults in Bangladesh: an exploratory study. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2017) 32:191–207. doi: 10.1007/s10823-017-9319-3

42. Bowling A. Lay perceptions of successful ageing: findings from a national survey of middle aged and older adults in Britain. Eur J Ageing. (2006) 3:123–36. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0032-2

43. Martinson M, Berridge C. Successful aging and its discontents: a systematic review of the social gerontology literature. Gerontologist. (2015) 55:58–69. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu037

44. Shooshtari S, Menec V, Swift A, Tate R. Exploring ethno-cultural variations in how older Canadians define healthy aging: the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). J Aging Stud. 52:100834. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100834

45. Katz S, Calasanti T. Critical perspectives on successful aging: does it “appeal more than it illuminates”? Gerontologist. (2015) 55:26–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu027

46. Peterson JR, Baumgartner DA, Austin SL. Healthy ageing in the far North: perspectives and prescriptions. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2020) 79:1735036. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2020.1735036

47. Phelan EA, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ, Larson EB. Older adults' views of “successful aging”—how do they compare with researchers' definitions? J Am Geriatr Soc. (2004) 52:211–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52056.x

48. Manasatchakun P, Chotiga P, Roxberg A, Asp M. Healthy ageing in Isan-Thai culture—A phenomenographic study based on older persons' lived experiences. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. (2016) 11:29463. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.29463

49. Coombes J, Lukaszyk C, Sherrington C, Keay L, Tiedemann A, Moore R, et al. First Nation Elders' perspectives on healthy ageing in NSW, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2018) 42:361–4. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12796

50. Dudgeon P, Wright M, Paradies Y, Garvey D, Walker I. The social, cultural and historical context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Austral Instit Health Welfare Canberra. (2010) 2010:5–42. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30058500

51. Korff J. Creative Spirits. Torres Strait Islander Culture. (2021). Available online at: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/people/torres-strait-islander-culture (accessed sepetember 13, 2021).

52. Pace JE, Grenier A. Expanding the circle of knowledge: reconceptualizing successful aging among North American Older Indigenous peoples. J Gerontol Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2017) 72:248–58. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw128

53. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

54. The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual 2015. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute (2015).

55. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

56. Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2013) 13:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

57. Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Armitage G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new tool. J Eval Clin Pract. (2012) 18:746–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x

58. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

59. United Nations. Indigenous Peoples at the United Nations 2021. (2021). Available online at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/about-us.html (accessed September 20, 2021).

60. Fenton L, Lauckner H, Gilbert RT. critical appraisal tool: comments and critiques. J Eval Clin Pract. (2015) 21:1125–8. doi: 10.1111/jep.12487

61. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. (2009) 26:91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

62. Abonyi S, Favel M. Marie's story of aging well: toward new perspectives on the experience of aging for Aboriginal seniors in Canada. Anthropol Aging Quart. (2012) 33:11–20. Available online at: http://anthropologyandgerontology.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/AAQ33-1.pdf

63. Baron M, Fletcher C, Riva M. Aging, health and place from the perspective of elders in an inuit community. J Cross Cultur Gerontol. (2020) 35:133–53. doi: 10.1007/s10823-020-09398-5

64. Baron M, Riva M, Fletcher C. The social determinants of healthy ageing in the Canadian Arctic. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2019) 78:1630234. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2019.1630234

65. Baskin C, Davey CJ. Grannies, elders, and friends: aging aboriginal women in Toronto. J Gerontol Soc Work. (2015) 58:46–65. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2014.912997

66. Boyd KM. “We Did Listen.” Successful Aging from the Perspective of Alaska Native Elders in Northwest Alaska. (2018). Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igy023.630

67. Brooks-Cleator LA, Lewis JP, Alaska N. Elders' perspectives on physical activity and successful aging. Can J Aging. (2020) 39:294–304. doi: 10.1017/S0714980819000400

68. Brooks-Cleator LA, Giles AR, Flaherty M. Community-level factors that contribute to First Nations and Inuit older adults feeling supported to age well in a Canadian city. J Aging Stud. (2019) 48:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2019.01.001

69. Browne CV, Mokuau N, Ka'opua LS, Jung Kim B, Higuchi P, Braun KL. Listening to the voices of native hawaiian elders and ‘ohana caregivers: discussions on aging, health, and care preferences. J Cross Cultur Gerontol. (2014) 29:131–51. doi: 10.1007/s10823-014-9227-8

70. Browne CV, Braun KL. Away from the Islands: diaspora's effects on native hawaiian elders and families in California. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2017) 32:395–411. doi: 10.1007/s10823-017-9335-3

71. Butcher E, Breheny M. Dependence on place: a source of autonomy in later life for older Māori. J Aging Stud. (2016) 37:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2016.02.004

72. Collings P. “If you got everything, it's good enough”: perspectives on successful aging in a Canadian Inuit community. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2001) 16:127–55. doi: 10.1023/A:1010698200870

74. Gallardo-Peralta LP, Sanchez-Moreno E. Successful ageing in older persons belonging to the Aymara native community: exploring the protective role of psychosocial resources. Health Psychol Behav Med. (2019) 7:396–412. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2019.1691558

75. Hopkins SE, Kwachka P, Lardon C, Mohatt GV. Keeping busy: a Yup'ik/Cup'ik perspective on health and aging. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2007) 66:42–50. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18224

76. Laditka SB, Corwin SJ, Laditka JN, Liu R, Tseng W, Wu B, et al. Attitudes about aging well among a diverse group of older Americans: implications for promoting cognitive health. Gerontologist. (2009) 49:S30–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp084

77. Lewis JP. Successful aging through the eyes of alaska natives: exploring generational differences among alaska natives. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2010) 25:385–96. doi: 10.1007/s10823-010-9124-8

78. Lewis JP. Successful aging through the eyes of alaska native elders. What it means to be an elder in Bristol Bay, AK. Gerontologist. (2011) 51:540–9. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr006

79. Lewis JP. The importance of optimism in maintaining healthy aging in Rural Alaska. Qual Health Res. (2013) 23:1521–7. doi: 10.1177/1049732313508013

80. Lewis J. The future of successful aging in Alaska. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2013) 72:575–9. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21186

81. Lewis J. The role of the social engagement in the definition of successful ageing among alaska native elders in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Psychol Dev Soc J. (2014) 26:263–90. doi: 10.1177/0971333614549143

82. Lewis J. What successful aging means to Alaska Natives: exploring the reciprocal relationship between the health and well-being of Alaska Native Elders. Int J Aging Soc. (2014) 3:77–88. doi: 10.18848/2160-1909/CGP/v03i01/57722

83. Pace J. Meanings of Memory: Understanding Aging and Dementia in First Nations Communities on Manitoulin Island, Ontario. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University (2013).

84. Pace J. “Place-ing” dementia prevention and care in NunatuKavut, Labrador. Can J Aging. (2020) 39:247–62. doi: 10.1017/S0714980819000576

85. Pearse K, Avuri S, Craig K. Moreton Consulting. Growing old in Kempsey. Aboriginal People Talk About Their Ageing Needs. Australia. Bellingen, NSW: Moreton Consulting (2016).

86. Ranzijn R. Active ageing- another way to oppress marginalized and disadvantaged elders? aboriginal elders as a case study. J Health Psychol. (2010) 15:716–23. doi: 10.1177/1359105310368181

87. Smith J, Easton PSS. Inupiaq elders study: aspects of aging among male and female elders. Int J Circumpolar Health. (2009) 68:182–96. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i2.18323

88. Waters WF, Gallegos CA. Aging, health, and identity in Ecuador's indigenous communities. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2014) 29:371–87. doi: 10.1007/s10823-014-9243-8

89. Waugh E, Mackenzie L. Ageing well from an urban Indigenous Australian perspective. Aust Occup Ther J. (2011) 58:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00914.x

90. Wettasinghe PM, Allan W, Garvey G, Timbery A, Hoskins S, Veinovic M, et al. Older aboriginal australians' health concerns and preferences for healthy ageing programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7390. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207390

91. Braun K. Thematic Analysis: A Reflexive Approach. (2021). Available online at: https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/thematic-analysis.html (accessed September 20, 2021).

92. Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitat Res Sport Exerc Health. (2019) 11:589–97. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

93. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. (2009) 62:1006–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

94. Wright-St Clair VA, Rapson A, Kepa M, Connolly M, Keeling S, Rolleston A, et al. Ethnic and gender differences in preferred activities among Māori and non-Māori of Advanced age in New Zealand. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2017) 32:433–46. doi: 10.1007/s10823-017-9324-6

95. Sixsmith J, Sixsmith A, Malmgren Fange A, Naumann D, Kucsera C, Tomsone S, et al. Healthy ageing and home: the perspectives of very old people in five European countries. Soc Sci Med. (2014) 106:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.006

96. Kingsley J, Townsend M, Henderson-Wilson C, Bolam B. Developing an exploratory framework linking Australian Aboriginal peoples' connection to Country and concepts of wellbeing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2013) 10:678–98. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10020678

97. Dionigi RA. Stereotypes of aging: their effects on the health of older adults. J Geriatr. (2015) 2015:954027. doi: 10.1155/2015/954027

98. Tanaka MF, Glasser M, Suphan T, Vater J. Giving back to get back: assessment of native and non-native american perceptions of generativity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2020) 31:1427–39. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2020.0103

99. Gonzales E, Matz-Costa C, Morrow-Howell N. Increasing opportunities for the productive engagement of older adults: a response to population aging. Gerontologist. (2015) 55:252–61. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu176

100. Ryan C, Jackson R, Gabel C, King A, Masching R, Thomas C. Successful aging: indigenous men aging in a good way with HIV/AIDS. Can J Aging. (2020) 39:305–17. doi: 10.1017/S0714980819000497

101. Pruchno R. Successful aging: contentious past, productive future. Gerontologist. (2015) 55:1–4. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv002

102. Hornby-Turner YC, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Health assets in older age: a systematic review. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e013226. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013226

103. Howell BM, Peterson JR. “With age comes wisdom:” a qualitative review of elder perspectives on healthy aging in the circumpolar north. J Cross Cult Gerontol. (2020) 35:113–31. doi: 10.1007/s10823-020-09399-4

104. Hayman NE, White NE, Spurling GK. Improving Indigenous patients' access to mainstream health services: the Inala experience. Med J Austral. (2009) 190:604–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02581.x

105. Liaw ST, Lau P, Pyett P, Furler J, Burchill M, Rowley K, et al. Successful chronic disease care for Aboriginal Australians requires cultural competence. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2011) 35:238–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00701.x

Keywords: Indigenous, aging, Indigenous health, Indigenous wellbeing, Indigenous older adults, scoping review

Citation: Quigley R, Russell SG, Larkins S, Taylor S, Sagigi B, Strivens E and Redman-MacLaren M (2022) Aging Well for Indigenous Peoples: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 10:780898. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.780898

Received: 21 September 2021; Accepted: 10 January 2022;

Published: 10 February 2022.