- 1Department of Psychiatry, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan

- 2Behavioral Sleep Medicine and Sciences Laboratory, Department of Psychological Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, Tokyo Kasei University, Tokyo, Japan

- 3Department of Sociology, Durham University, Durham, United Kingdom

- 4Iverson Health Innovation Research Institute, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia

- 5Prevention Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Sydney School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Editorial on the Research Topic

The impact of social isolation and loneliness on mental health and wellbeing

Loneliness and social isolation are critical for health and wellbeing. Social isolation is a well-established social determinant of health, and its ill effects have been well-recognized for decades. Over the last 20 years, researchers have increasingly advocated that our health and wellbeing are not only detrimentally affected by being alone but also by feeling lonely (i.e., subjective social isolation) (1). Loneliness was flagged as a critical issue after the onset of the current public health crisis and was recently found to be a prevalent issue across the world (2). Although loneliness is studied as a phenomenon across different nations and cultures, and within different social groups, the exact meaning of loneliness, its antecedents, and its consequences on mental health and wellbeing may vary (3).

The way in which loneliness and social isolation contribute to mental health and wellbeing may be different during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was particularly evident after public health measures such as social restrictions, including national or localized lockdowns, were implemented. Furthermore, quarantine or self-isolation was also recommended for reducing infection (4). It is plausible that many people may have experienced the distress associated with social isolation or loneliness, or both, for the very first time during periods of lockdown, quarantine, and self-isolation. The impacts of quarantine or self-isolation may vary by population. In some populations, self-isolation due to COVID-19 had little influence on daytime sleepiness, insomnia, or depression compared with 1 year earlier (5).

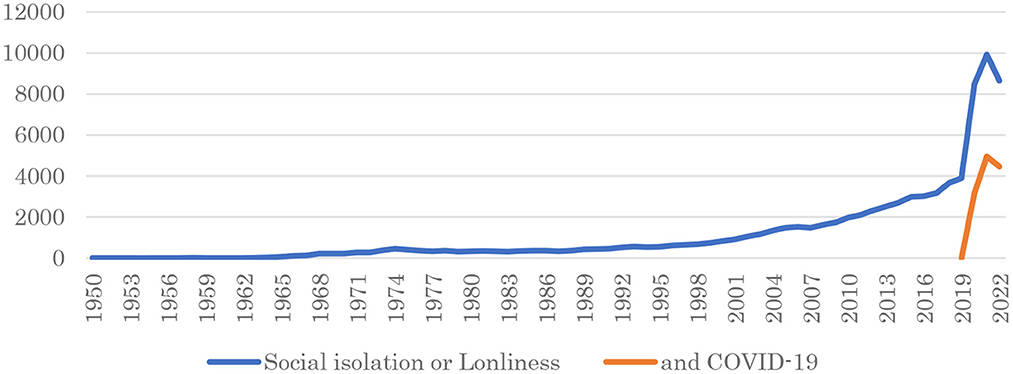

Research interest in this topic has accelerated, with the number of publications about “social isolation” or “loneliness” jumping significantly since 2020 (Figure 1). This reflects the public and research community interest in loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The estimated number of publications about “social isolation” or “loneliness” in 2022 decreased from that of 2021 (Figure 1). This decrease may reflect lower interest due to the lower incidence of new COVID-19 cases since January 2022 (6).

Figure 1. The number of publications about social isolation and loneliness by year. Data were obtained from Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/; accessed on 2022/11/4) through searches for “social isolation” or “loneliness” (blue line) and “social isolation” or “loneliness” plus “COVID-19” (orange line). The figures for 2022 were estimated from the numbers as of 2022/11/4.

This Research Topic was open for submission between 2021/7/16 and 2022/5/31, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fourteen papers were published on this special topic. Eleven of them had the term “COVID-19” (Bentley et al.; Liu et al.; Okajima et al.; Mansour et al.; Chernova et al.; McDowell et al.; Peng et al.; Lv et al.; Luo et al.; Pilcher et al.) or “coronavirus” (Goddard et al.) in the title, and another study (Lim et al.) tracked changes over time during the pandemic. Two papers were unrelated to the pandemic (Landry et al.; Chiao et al.). There was a report originally submitted to this Research Topic but it was eventually published in another section of this journal (7).

Five studies analyzed young participants aged 13–29 years old. Liu et al. and Okajima et al. studied high school students. Landry et al., Lv et al., and Chiao et al. studied young adults. Even though loneliness is also an important issue for older people (8), none of the studies in this Research Topic examined loneliness in older adult samples. Three studies targeted specific populations: Goddard et al. recruited people with mobility disabilities; Peng et al. studied consumers and their purchasing intentions; and Mansour et al. recruited men for their study. Most papers only focused on loneliness, but four investigated social isolation(Goddard et al.; Landry et al.; Luo et al.; Pilcher et al.).

Most studies analyzed social isolation and loneliness and their impact on mental health symptoms or related issues. Four studies analyzed depression (Liu et al.; Lim et al.; McDowell et al.; Lv et al.), three analyzed distress (Bentley et al.; Liu et al.; Chernova et al.) and anxiety (Okajima et al.; Lim et al.; McDowell et al.), and two analyzed sleep or sleep problems (Okajima et al.; Pilcher et al.). In addition, there were international collaborations during the pandemic (9). Two international studies are reported in this Research Topic (Bentley et al.; Lim et al.). The first study examined the association between loneliness and distress in the early stage of the pandemic in eleven countries (Bentley et al.). A subset of countries (three countries) in the study also repeated the analysis 3 months later and revealed that increased loneliness over time was associated with increased psychological distress (Bentley et al.). The second study examined how social restrictions contributed to the severity of loneliness, depression, and social anxiety in participants recruited from the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States (Lim et al.). The authors found that as social restrictions eased, loneliness and depression reduced, but there was an increase in social anxiety. Overall, the findings of these studies highlighted how sleep problems, social anxiety, and depression are interrelated (10). However, whether these interrelationships are maintained outside of the context of the pandemic remains unclear without the inclusion of pre-COVID-19 data.

The restrictions imposed on people's lives due to COVID-19 have come as a critical reminder of how fundamental social relationships are to our mental health and wellbeing. Countries around the world observed increasing rates of mental ill health during the pandemic and responded with significant government investment and policy changes to combat it (11).

Overall, the pandemic and its associated consequences for health and wellbeing may have highlighted the critical need for being around people and being meaningfully connected to others around us. A deeper knowledge of loneliness and social isolation is required to allow us to better understand their impact on mental health and wellbeing.

Author contributions

HK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ML wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception, manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Lim MH, Eres R, Vasan S. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: an update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2020) 55:793–810. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7

2. Surkalim DL, Luo M, Eres R, Gebel K, van Buskirk J, Bauman A, et al. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2022) 376:e067068. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067068

4. WHO. Contact Tracing and Quarantine in the Context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 6 July 2022 (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoVContact_tracing_and_quarantine-2022.1 (accessed November 14, 2022).

5. Ubara A, Sumi Y, Ito K, Matsuda A, Matsuo M, Miyamoto T, et al. Self-isolation due to COVID-19 is linked to small one-year changes in depression, sleepiness, and insomnia: results from a clinic for sleep disorders in Shiga Prefecture, Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:8971. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238971

6. WHO. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. (2022). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—2-november-2022 (accessed November 11, 2022).

7. Omichi O, Kaminishi Y, Kadotani H, Sumi Y, Ubara A, Nishikawa K, et al. Limited social support is associated with depression, anxiety, and insomnia in a Japanese working population. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:981592. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.981592

8. Noone C, Yang K. Community-based responses to loneliness in older people: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Soc Care Community. (2022) 30:e859–73. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13682

9. Hameed M, Najafi M, Cheeti S, Sheokand A, Mago A, Desai S. Factors influencing international collaboration on the prevention of COVID-19. Public Health. (2022) 212:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2022.08.017

10. Okajima I, Chung S, Suh S. Validation of the Japanese version of stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) and relationship among stress, insomnia, anxiety, and depression in healthcare workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. Sleep Med. (2021) 84:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.035

Keywords: social isolation (SI), loneliness, mental health, wellbeing, COVID-19

Citation: Kadotani H, Okajima I, Yang K and Lim MH (2022) Editorial: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on mental health and wellbeing. Front. Public Health 10:1106216. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1106216

Received: 23 November 2022; Accepted: 24 November 2022;

Published: 14 December 2022.

Edited and reviewed by: Wulf Rössler, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Kadotani, Okajima, Yang and Lim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hiroshi Kadotani,  a2Fkb3RhbmlzbGVlcEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

a2Fkb3RhbmlzbGVlcEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

†ORCID: Hiroshi Kadotani orcid.org/0000-0001-7474-3315

Isa Okajima orcid.org/0000-0003-3494-4328

Keming Yang orcid.org/0000-0003-0898-7420

Michelle H. Lim orcid.org/0000-0002-4136-5909

Hiroshi Kadotani

Hiroshi Kadotani Isa Okajima

Isa Okajima Keming Yang

Keming Yang Michelle H. Lim

Michelle H. Lim