94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Front. Public Health, 16 February 2023

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1093720

Katharina Wabnitz1,2†

Katharina Wabnitz1,2† Eva-Maria Schwienhorst-Stich3,4*†

Eva-Maria Schwienhorst-Stich3,4*† Franziska Asbeck3

Franziska Asbeck3 Cara Sophie Fellmann3

Cara Sophie Fellmann3 Sophie Gepp2,5,6

Sophie Gepp2,5,6 Jana Leberl7

Jana Leberl7 Nikolaus Christian Simon Mezger2,8,9

Nikolaus Christian Simon Mezger2,8,9 Michael Eichinger10,11

Michael Eichinger10,11Physicians play an important role in adapting to and mitigating the adverse health effects of the unfolding climate and ecological crises. To fully harness this potential, future physicians need to acquire knowledge, values, skills, and leadership attributes to care for patients presenting with environmental change-related conditions and to initiate and propel transformative change in healthcare and other sectors of society including, but not limited to, the decarbonization of healthcare systems, the transition to renewable energies and the transformation of transport and food systems. Despite the potential of Planetary Health Education (PHE) to support medical students in becoming agents of change, best-practice examples of mainstreaming PHE in medical curricula remain scarce both in Germany and internationally. The process of revising and updating the Medical Licensing Regulations and the National Competency-based Catalog of Learning Objectives for Medical Education in Germany provided a window of opportunity to address this implementation challenge. In this article, we describe the development and content of national Planetary Health learning objectives for Germany. We anticipate that the learning objectives will stimulate the development and implementation of innovative Planetary Health teaching, learning and exam formats in medical schools and inform similar initiatives in other health professions. The availability of Planetary Health learning objectives in other countries will provide opportunities for cross-country and interdisciplinary exchange of experiences and validation of content, thus supporting the consolidation of Planetary Health learning objectives and the improvement of PHE for all health professionals globally.

The anthropogenic climate crisis and the transgression of other planetary boundaries including biodiversity loss, aberrant biogeochemical flows and pollution are the greatest threats to public health in the twenty-first century (1). Adverse health effects include increased morbidity and mortality due to extreme weather events such as floods and heat waves, changing patterns of vector-borne diseases, altered prevalences of non-communicable conditions like asthma and other atopic diseases and adverse effects on mental health (2). The interdependence between the climate and ecological crises, societal, political, and economic systems as well as health and wellbeing are at the core of the emerging concept of Planetary Health, defined as “the health of human civilization and the state of the natural systems on which it depends” (3). Mirroring this interdependence, most adaptation and mitigation policies including the transformation of transport, energy, and agri-food systems are associated with substantial health co-benefits by, inter alia, reducing air pollution, increasing physical activity, and improving nutrition.

Physicians play an important role in adapting to and mitigating the climate and ecological crises and thus in attenuating adverse health effects. This includes, but is not limited to, addressing risk factors associated with the climate and ecological crises in medical histories and anticipatory guidance, building expertise in the treatment of climate-sensitive health conditions and implementing policies to decarbonize healthcare systems. The contribution of physicians to adaptation and mitigation is based on a professional ethos emphasizing their responsibility for the wellbeing of individuals and populations now and in the future (4), high levels of trust among the general public (5, 6) and their role as advocates for health-promoting climate policies (7). Planetary Health Education (PHE) aims at equipping physicians with knowledge, attitudes, values, and skills to fully harness this potential. To strengthen the role of physicians as change agents in healthcare institutions and other sectors of society, PHE moreover stimulates the development of leadership attributes, confidence and systems thinking skills (8–10). While the urgency to integrate PHE into medical curricula has been frequently expressed (10–12), best-practice examples of mainstreaming PHE in medical curricula remain scarce both in Germany and internationally (13–16). To date, PHE in medical schools is mostly limited to student-driven extra-curricular lecture series and elective courses (17), with a majority of courses only available in English and targeting healthcare professionals from the global north (18).

In Germany, the National Competency-based Catalog of Learning Objectives for Medical Education (hereinafter referred to as National Catalog of Learning Objectives; Nationaler Kompetenzbasierter Lernzielkatalog Medizin, NKLM), first published in 2015 by the Association of Medical Faculties in Germany, is currently refined in a nationwide multi-stakeholder process. It consists of a mandatory core curriculum and is accompanied by several non-mandatory but thematically cross-cutting chapters that can be covered by medical schools. Paralleling the refinement of the National Catalog of Learning Objectives, the German Medical Licensing Regulations are currently updated. After approval by the Federal Council, both documents will provide the legal foundation for the structure and content of medical education in Germany. It is currently anticipated that both documents will go into effect in 2025 and will stimulate changes to the curricula of all medical schools such as strengthening primary and outpatient care and enabling clinical electives in local public health departments. The update of the Medical Licensing Regulations and the National Catalog of Learning Objectives constituted a unique window of opportunity to address the lack of PHE in German medical curricula by developing national Planetary Health learning objectives. Given their impact on curriculum design, we anticipate that the learning objectives will stimulate the development and implementation of innovative teaching, learning and exam formats in medical schools. Further background information on medical education in Germany and current reform processes is presented in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary material.

In this article, we describe the development and content of national Planetary Health learning objectives that adhere to the structural requirements of the National Catalog of Learning Objectives. We hope that the catalog of learning objectives will inspire similar activities in other (health-related) disciplines and countries.

The development of a catalog of national Planetary Health learning objectives proceeded iteratively. Initially, an ad hoc task force comprised of seven medical students and two early career health professionals with expertise in PHE were invited by the Association of Medical Faculties in Germany in 2020 to develop a set of competency-based Planetary Health learning objectives for the non-mandatory part of the National Catalog of Learning Objectives. Given that no widely used Planetary Health learning objectives were available in 2020, the task force developed an initial set of learning objectives as well as superordinate competencies and sub-competencies based on their expertise in PHE including the development and implementation of Planetary Health elective courses. Based on this initial set, we iteratively revised, restructured, and expanded the learning objectives in five steps.

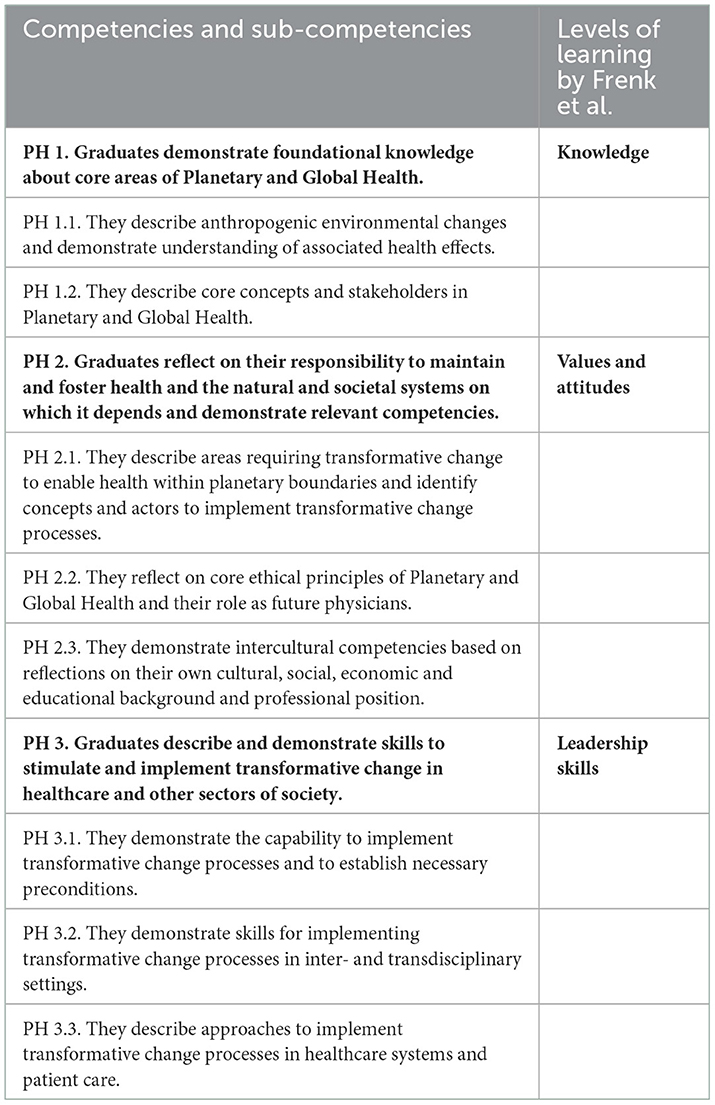

First, to improve the structure of the initial set of learning objectives, the taskforce—now consisting of four medical students and three early career health professionals with expertise in PHE—structured the learning objectives and the superordinate competencies and sub-competencies into different levels. Guided by prior work in medical education research (8), we applied the following levels of learning: (1) knowledge, (2) values and attitudes, and (3) transformative skills (Table 1).

Table 1. Competencies and sub-competencies in the catalog of national Planetary Health learning objectives and their alignment with the levels of learning presented by Frenk et al. (8).

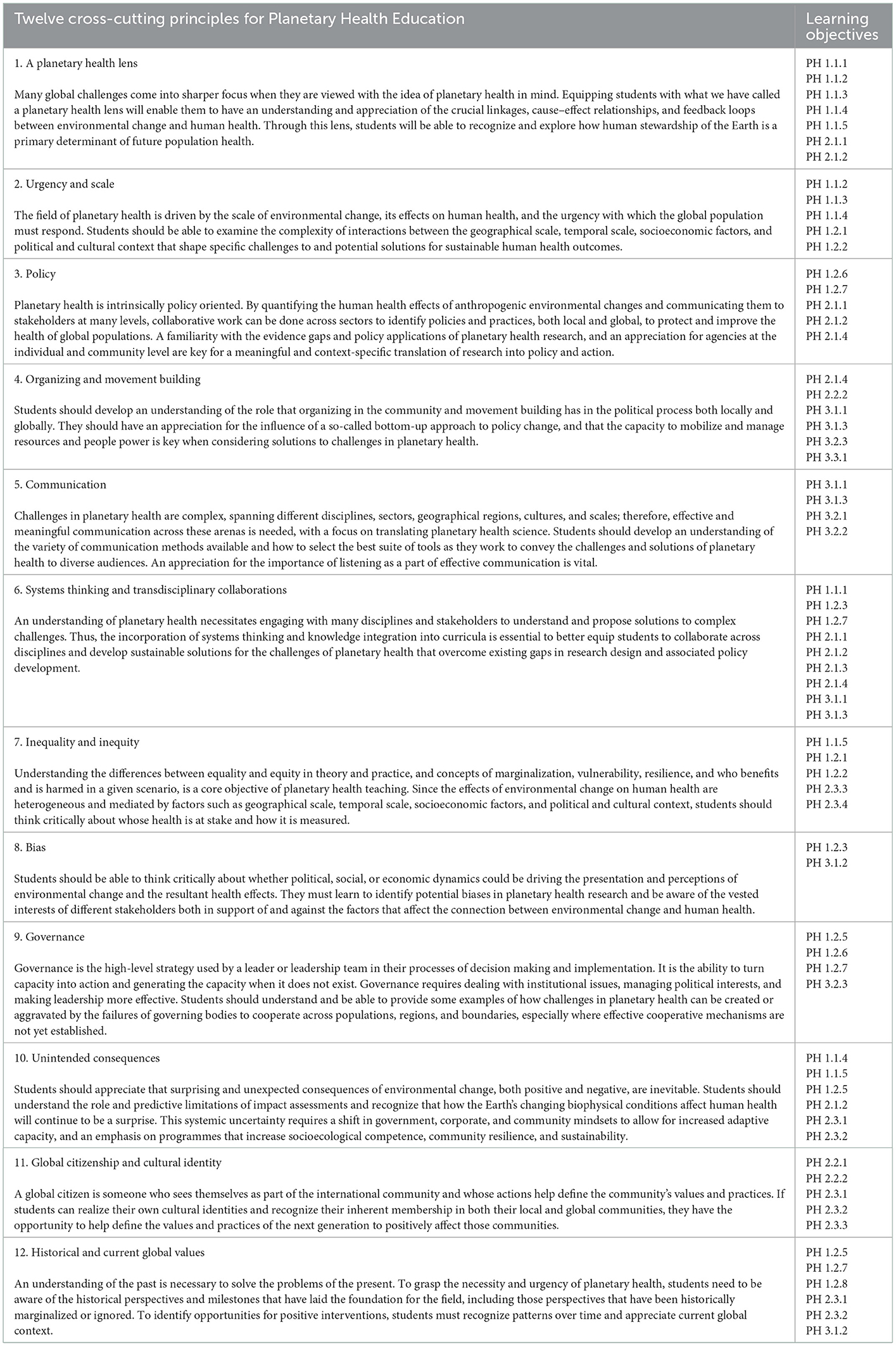

Second, to improve the comprehensiveness of the initial set of learning objectives, we expanded the set based on seminal contributions to the emerging field of Planetary Health and PHE. Two members of the task force independently mapped the learning objectives against the 12 Cross-cutting principles of planetary health education, a set of foundational principles proposed to guide teaching in the field of Planetary Health (Table 2) (19). In addition, one member of the task force reviewed three additional documents, (1) the first Planetary Health textbook (20), (2) the Report of the Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health (3) and (3) the 2019 Report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change (21). Based on gaps identified during the mapping and review, we expanded the initial set of learning objectives, resulting in a refined catalog comprised of three overarching competencies, eight sub-competencies and 31 learning objectives. To increase practical relevance and to facilitate the application of the Planetary Health learning objectives in curriculum development and teaching, we identified several health-related examples for each learning objective (see last column in Appendix 2 in the Supplementary material).

Table 2. Mapping of Planetary Health learning objectives against the Twelve cross-cutting principles for Planetary Health Education (19).

Third, the refined catalog of Planetary Health learning objectives was subjected to a first round of external peer review by two university professors for Global Health and Health and Climate Change in Germany, respectively. Based on their comments and feedback, we further refined the learning objectives.

Fourth, given that the Planetary Health learning objectives are part of the non-mandatory but cross-cutting chapters of the National Catalog of Learning Objectives, we established links to the mandatory core curriculum to showcase the relevance of Planetary Health to other medical subject areas. To this end we (1) implemented cross-references between learning objectives in the Planetary Health catalog and the core curriculum and (2) added examples pertinent to Planetary Health to learning objectives in the core curriculum. Initially, we identified learning objectives suitable for cross-linking and adding Planetary Health examples by a double-blinded screening of the core curriculum. Next, we reached consensus in pairs and the entire task force on which learning objectives were to be linked and the wording and location of Planetary Health examples to be included in the core curriculum, respectively. Finally, we sought approval from the chapter authors of the core curriculum for integrating Planetary Health examples in their chapters.

In 2021, the Institute for Medical and Pharmaceutical Examinations (Institut für Medizinische und Pharmazeutische Prüfungsfragen, IMPP), responsible for developing and administering centralized state examinations, established an interdisciplinary working group on Climate, Environment and Health Impact Assessment (22) coordinated by two members of the task force (EMS and ME). The working group aims at informing and leading on the development of Planetary Health-related exam questions to be included in state examinations for physicians and other health professionals and is comprised of experts with a broad spectrum of expertise including different medical specialties, psychology, psychotherapy, sociology, and transition research. In a fifth and final step, members of the working group reviewed the Planetary Health learning objectives and suggested further refinements based on several rounds of discussions within the working group. Refinements were mostly focused on concretizing content of specific learning objectives and examples. The final catalog of national Planetary Health learning objectives was published together with the core curriculum in July 2021 and is now available online (23). An English translation of the learning objectives is presented in Appendix 2 in the Supplementary material.

To our knowledge, the catalog of national Planetary Health learning objectives is the first attempt to operationalize general principles of PHE and to develop a catalog of actionable learning objectives for medical education in Germany. Following the principle of constructive alignment, defined here as the alignment of teaching, and learning activities and assessment tasks with intended learning objectives (24), we anticipate that the Planetary Health learning objectives will support the development and implementation of innovative Planetary Health teaching, learning and exam formats in medical schools. Complementing local initiatives in medical schools, the adaptation of national state examinations based on the catalog of Planetary Health learning objectives is a promising lever to stimulate PHE in medical schools, independent of local initiatives. The activities described in this article complement a small number of similar initiatives internationally (25–28). The availability of other PHE catalogs will provide opportunities for cross-country and interdisciplinary exchange of experiences and validation of content, thus supporting the consolidation of Planetary Health learning objectives and alignment of PHE for all health professionals.

Given the increasing health impacts of the climate and ecological crises (2), we expect a growing interest from policy and health systems stakeholders in actions to adapt to and mitigate these crises in the healthcare sector, in Germany and internationally. This is underscored, inter alia, by the adoption of several motions at the annual meeting of the German Medical Association, including a motion on the integration of Planetary Health in continuous professional education (29). PHE guided by the national Planetary Health learning objectives has the potential to equip physicians with the knowledge, values, skills, confidence, and leadership attributes to adequately respond to the climate and ecological crises. We are glad to share our experiences with interested individuals and organizations worldwide and are grateful for any feedback that stimulates the refinement of the current version of the national Planetary Health learning objectives for Germany.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

KW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. E-MS-S and ME provided substantial conceptual input to the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the different versions of the manuscript, suggested revisions, and approved the version to be published.

This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Wuerzburg.

We thank all members of the ad hoc task force and the working group on Climate, Environment and Health Impact Assessment at the IMPP for contributing to the catalog of Planetary Health learning objectives. Moreover, we are indebted to Sabine Gabrysch, Karin Geffert, Jacqueline Jennebach, and Michael Knipper for reviewing an earlier draft of the article; to Olaf Ahlers for administrative and technical support and to Leonie Dudda and Karin Geffert for initiating the develop of National Planetary Health learning objectives.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1093720/full#supplementary-material

1. Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, Ball S, Bell S, Bellamy R, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet. (2009) 373:1693–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1

2. Romanello M, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, Green C, Kennard H, Lampard P, et al. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet. (2022) 400:1619–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01540-9

3. Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C, Boltz F, Capon AG, de Souza Dias BF, et al. Safeguarding human health in the anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet. (2015) 386:1973–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1

4. Parsa-Parsi RW. The international code of medical ethics of the world medical association. JAMA. (2022) 328:2018–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.19697

5. Ipsos MORI. Ipsos MORI Veracity Index 2020. (2020). Available online at: https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/ipsos-mori-veracity-index-2020-trust-in-professions (accessed January 12, 2023).

6. Chen L, Vasudev G, Szeto A, Cheung WY. Trust in doctors and non-doctor sources for health and medical information. Am Soc Clin Oncol. (2018) 36 (15 Suppl):10086. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.10086

7. Maibach E, Frumkin H, Ahdoot S. Health professionals and the climate crisis: trusted voices, essential roles. World Med Health Policy. (2021) 13:137–45. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.421

8. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, Evans T, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. (2010) 376:1923–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5

9. Guzmán CAF, Aguirre AA, Astle B, Barros E, Bayles B, Chimbari M, et al. A framework to guide planetary health education. Lancet Planet Health. (2021) 5:e253–5. doi: 10.5822/phef2021

10. Shaw E, Walpole S, McLean M, Alvarez-Nieto C, Barna S, Bazin K, et al. AMEE consensus statement: planetary health and education for sustainable healthcare. Med Teach. (2021) 43:272–86. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1860207

11. Wellbery C, Sheffield P, Timmireddy K, Sarfaty M, Teherani A, Fallar R. It's time for medical schools to introduce climate change into their curricula. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. (2018) 93:1774. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002368

12. El Omrani O. Climate Change and Medical Schools. (2020). Available online at: https://ifmsa.org/climate-change-medical-schools/ (accessed January 12, 2023).

13. Shea B, Knowlton K, Shaman J. Assessment of climate-health curricula at international health professions schools. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e206609. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6609

14. Planetary Health Report Card. 2021-2022 Summary Report for Germany. (2022). Available online at: https://phreportcard.org/germany/ (accessed January 12, 2023).

15. Klünder V, Schwenke P, Hertig E, Jochem C, Kaspar-Ott I, Schwienhorst-Stich EM, et al. A cross-sectional study on the knowledge of and interest in Planetary Health in health-related study programmes in Germany. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:937854. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.937854

16. Nordrum OL, Kirk A, Lee SA, Haley K, Killilea D, Khalid I, et al. Planetary health education in medical curricula in the Republic of Ireland. Med Teach. (2022) 44:1237–43. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2072279

17. Wabnitz KJ, Galle S, Hegge L, Masztalerz O, Schwienhorst-Stich EM, Eichinger M. Planetary health-transformative education regarding the climate and sustainability crises for health professionals. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. (2021) 64:378–83. doi: 10.1007/s00103-021-03289-x

18. Asaduzzaman M, Ara R, Afrin S, Meiring JE, Saif-Ur-Rahman KM. Planetary health education and capacity building for healthcare professionals in a global context: current opportunities, gaps and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:11786. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191811786

19. Stone SB, Myers SS, Golden CD. Cross-cutting principles for planetary health education. Lancet Planet Health. (2018) 2:e192–3. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30022-6

20. Myers S, Frumkin H. Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves. Washington, DC: Island Press (2020). doi: 10.5822/978-1-61091-966-1

21. Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Boykoff M, et al. The 2019 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet. (2019) 394:1836–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32596-6

22. Stühler M. Klimafolgen und Diversity in den Medizinischen Staatsexamina verankern. (2021). Available online at: https://www.img.uni-bayreuth.de/de/presse/2021/IMPP_Klimawandel/IMPP-Medieninformation-AG-Klima-Gender-2021-03-03.pdf (accessed January 12, 2023).

23. NKLM. Planetare und Globale Gesundheit. (2021). Available online at: https://nklm.de/zend/objective/list/orderBy/@objectivePosition/studiengang/Themen/zeitsemester/Themen%20und%20Fachkataloge/fachsemester/Planetare%20und%20Globale%20Gesundheit%20(Stand%201.%20Juli%2021) (accessed January 12, 2023).

24. Biggs J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High Educ. (1996) 32:347–64. doi: 10.1007/BF00138871

25. Burch H, Beaton LJ, Simpson G, Watson B, Maxwell J, Winkel K. A planetary health-organ system map to integrate climate change and health content into medical curricula. Med J Aust. (2022) 217:469–73. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51737

26. Health Environment Adaptive Response Task Force. Planetary Health Competencies. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cfms.org/what-we-do/global-health/heart-competencies (accessed January 12, 2023).

27. Navarrete-Welton A, Chen JJ, Byg B, Malani K, Li ML, Martin KD, et al. A grassroots approach for greener education: an example of a medical student-driven planetary health curriculum. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:1013880. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1013880

28. Tun S, Martin T. Education for Sustainable Healthcare—A curriculum for the UK. London: Medical Schools Council (2022).

29. Bundesärztekammer. Beschlussprotokoll des 125. Deutschen Ärztetags. Berlin (2021). Available online at: https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/BAEK/Aerztetag/125.DAET/pdf/Beschlussprotokoll_125DAET2021_Stand_24112021.pdf (accessed January 12, 2023).

Keywords: climate change, curriculum development, education for sustainable healthcare, medical education, Planetary Health, Planetary Health Education, transformative education

Citation: Wabnitz K, Schwienhorst-Stich E-M, Asbeck F, Fellmann CS, Gepp S, Leberl J, Mezger NCS and Eichinger M (2023) National Planetary Health learning objectives for Germany: A steppingstone for medical education to promote transformative change. Front. Public Health 10:1093720. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1093720

Received: 09 November 2022; Accepted: 28 December 2022;

Published: 16 February 2023.

Edited by:

Cecilia Sorensen, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Natasha Sood, Penn State College of Medicine, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Wabnitz, Schwienhorst-Stich, Asbeck, Fellmann, Gepp, Leberl, Mezger and Eichinger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eva-Maria Schwienhorst-Stich, c2Nod2llbmhvcl9lQHVrdy5kZQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.