- 1The Matilda Centre for Research in Mental Health and Substance Use, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2eCentre Clinic, School of Psychological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3Deakin Health Economics, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC, Australia

- 4Priority Research Centre for Brain and Mental Health, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Employee alcohol and other drug use can negatively impact the workplace, resulting in absenteeism, reduced productivity, high turnover, and worksite safety issues. As the workplace can influence employee substance use through environmental and cultural factors, it also presents a key opportunity to deliver interventions, particularly to employees who may not otherwise seek help. This is a systematic review of workplace-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of problematic substance use. Five databases were searched for efficacy, effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness studies and reviews published since 2010 that measured use of psychoactive substances (i.e., alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, and stimulants) as a primary or secondary outcome, in employees aged over 18. Thirty-nine articles were identified, 28 describing primary research and 11 reviews, most of which focused solely on alcohol use. Heterogeneity between studies with respect to intervention and evaluation design limited the degree to which findings could be synthesized, however, there is some promising evidence for workplace-based universal health promotion interventions, targeted brief interventions, and universal substance use screening. The few studies that examined implementation in the workplace revealed specific barriers including lack of engagement with e-health interventions, heavy use and reluctance to seek help amongst male employees, and confidentiality concerns. Tailoring interventions to each workplace, and ease of implementation and employee engagement emerged as facilitators. Further high-quality research is needed to examine the effectiveness of workplace substance use testing, Employee Assistance Programs, and strategies targeting the use of substances other than alcohol in the workplace.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=227598, PROSPERO [CRD42021227598].

Introduction

Most people who use alcohol and other drugs, both legal and illegal, are employed (1) and 60% of people with substance use disorders (SUDs) have been found to be currently employed (2). Although the relationship is complex, employee substance use has long been associated with a range of negative work-related outcomes including absenteeism (3, 4), loss of productivity (5), high turnover (6), and workplace accidents (7). The nature of a person's work and their workplace may also impact on substance use through factors such as job-related stressors, availability of substances in the workplace environment, and workplace substance use norms (3, 8–11). Of particular concern to employers, workplace stressors may specifically increase substance use that occurs before, during and after work (12).

Irrespective of whether substance use is or is not directly associated with employees' work, the workplace setting offers key opportunities for prevention, early intervention and treatment. In particular, workplace-based initiatives may facilitate early identification of those at-risk of problematic substance use, as well as facilitate access to appropriate supports, thereby reducing the likelihood of adverse personal and occupational outcomes (13). However, the workplace can also be a complex intervention setting due to the influence of both workplace (e.g., workplace culture) and workforce (e.g., age and sex) characteristics on substance use (14–17) and intervention implementation (18).

Recognizing the potential of the workplace as setting for substance use interventions, a growing number of workplace-based initiatives and interventions have been developed and evaluated. Although a relatively large number of studies have been conducted, there is considerable heterogeneity with regard to the samples and interventions investigated, the methods used, and quality of this research undertaken, making it difficult for organizations and practitioners to interpret the findings. Although several reviews have been undertaken they have been limited in scope, focusing on specific population groups (19, 20), intervention modalities (21), study designs (22), particular drug classes (23); and/or are somewhat dated. A rigorous comprehensive review and synthesis of the contemporary literature regarding the efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace-based interventions for problematic substance use, including an examination of factors influencing their impact, and barriers and facilitators to implementation, is necessary to help guide organizational decision making and inform future research priorities. As such, this review aims to examine:

i. The efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace-based interventions for problematic substance use;

ii. Workforce characteristics that influence the impact of interventions on substance use outcomes; and

iii. Barriers and facilitators to implementing interventions for different drug classes in the workplace.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD42021227598).

Search strategy

For full details of the search strategy, see Supplementary materials. Five electronic databases of published literature were searched: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library and Scopus. A combination of free-text keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were adapted to the conventions of each database. Search terms related to three main topics:

1. Substance use (e.g., “substance use,” “alcohol use”);

2. Intervention setting (e.g., “workplace,” “workforce”); and

3. Study design (e.g., “randomized controlled trial,” “cost-effectiveness”)

Following full-text screening, the reference lists of included articles (snowballing) and those articles citing them (reverse snowballing) were searched manually to identify additional eligible articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) published in 2010 or later; (ii) written in English; (iii) conducted with human participants; (iv) participants were aged 18 or over; (v) measured the efficacy, effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness of an intervention; (vi) reported individual-level outcomes relating to the use of alcohol, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, or stimulants (irrespective of whether the substance was prescribed or non-prescribed); (vii) participants were currently employed and were not volunteers; and (viii) intervention was provided by or sourced through participants' employer (i.e., workplace-based). Articles were excluded if they utilized cross-sectional, cohort or case study designs or did not describe the results of a study (e.g., protocol papers, commentaries, conference abstracts, editorials).

Data collection

Screening and data extraction were conducted in Covidence, a web-based software platform developed by Veritas Health Innovation, Australia. Following the removal of duplicates, three reviewers independently screened (title and abstract) and conducted full-text review of each article (two reviewers per article; AM, JS, MA); conflicts were resolved via consensus. Two reviewers extracted data from each article, and conflicts were resolved by the third reviewer. One author (MLC) extracted economic evaluation data from relevant articles. Extracted data included study (e.g., setting, target population), participant (e.g., age, sex), and intervention (e.g., offered to all employees or targeted, focused on substance use or broader health and well-being) characteristics, as well as outcomes measured.

Evidence synthesis and quality assessment

A narrative synthesis approach was used to address the research questions. A modified version of the Downs and Black quality assessment (24) was used to assess the quality of primary studies. Two investigators independently rated each study, and conflicts were resolved by the third reviewer (AM, JS, MA). Quality ratings were as follows: poor (scored ≤14), fair (15–18, 25), good (19, 26–30) and excellent (20–22).

The quality of systematic reviews was assessed using the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (31), comprising seven items, with an additional item for reviews that also included a meta-analysis. Higher scores indicated higher quality.

Economic evaluation quality was assessed using the Drummond Checklist (32) comprised of 10 criteria involving 33 sub-questions answered by ‘yes' (scored 1), ‘no' (scored 0) and ‘can't tell' (scored 0.5). Studies that scored at least 9 were considered ‘Good' quality, between 6 and 8 were ‘Fair' quality, and 5 or below were ‘Poor' quality.

Results

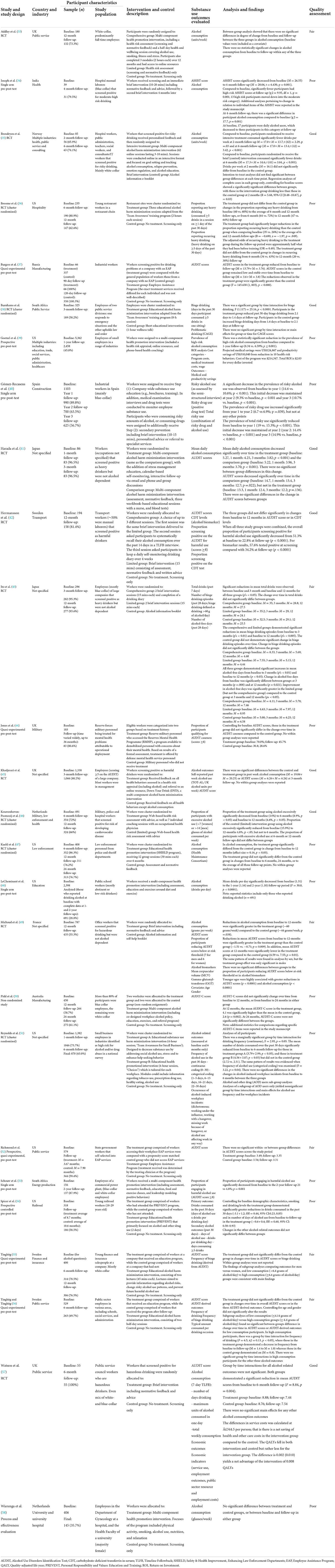

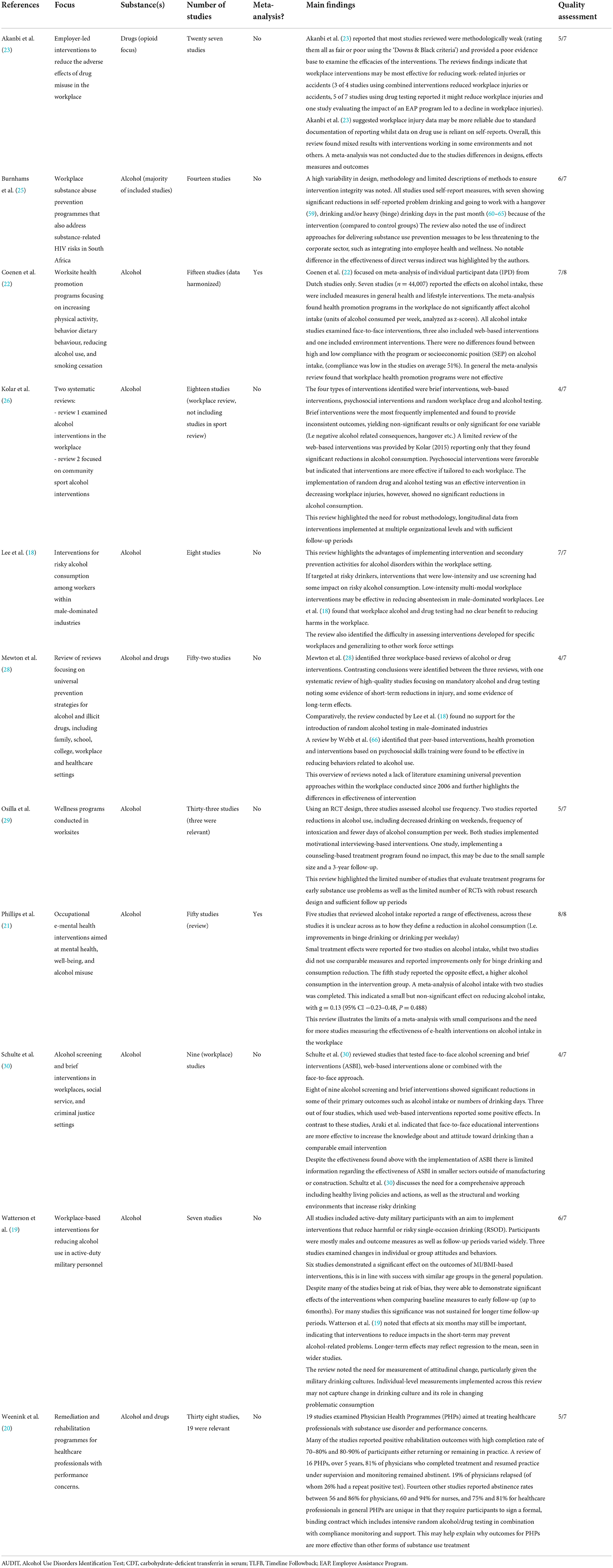

For full details of the characteristics and findings of each primary research study, see Table 1; for reviews, see Table 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of primary studies evaluating the effectiveness workplace-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of problematic substance use.

Table 2. Characteristics of reviews evaluating the effectiveness workplace-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of problematic substance use.

Study selection

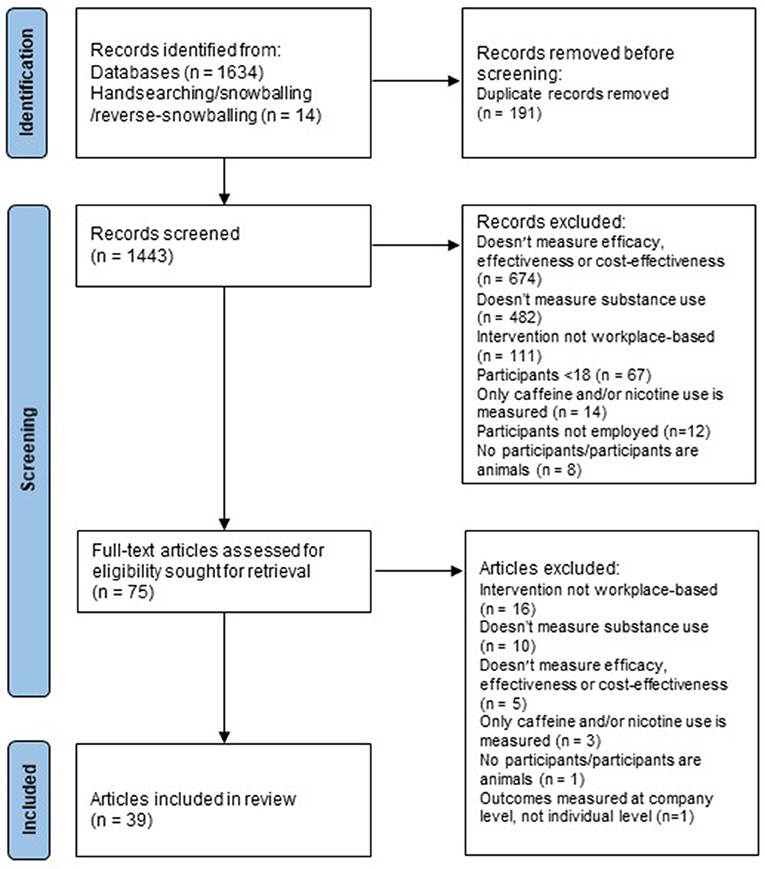

After removal of duplicates, the database searches identified 1,443 unique articles, 1,365 of which were excluded in title and abstract screening (see Figure 1). Of the 78 articles screened in full-text review, 39 met inclusion criteria; 28 were primary studies that evaluated a workplace-based intervention; 10 were systematic reviews, two of which conducted a meta-analysis (21, 22); and one was an overview of reviews (28).

Study characteristics

Of 28 primary studies, 14 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs; 5 cluster-randomized), seven were quasi-experimental, and six used single-group pre-/post-test designs. Three studies conducted an economic evaluation (39, 45, 57). Most primary studies were conducted in the United States (US; n = 7) or United Kingdom (UK; n = 5); three in Sweden; two in each of the Netherlands, Japan and South Africa; and one in each of Norway, Spain, France, Russia, India and Australia. With regard to substance use outcomes, the overwhelming majority (27/28) solely reported alcohol use.

Baseline sample sizes ranged from 39 (34) to 5,362 (39). Follow-up rates ranged from 45.8% (39) to 100% (37), with most studies achieving follow-up rates of 60–80% at their final timepoint. Final follow-up ranged from 1-month to 3-years post-baseline. Studies recruited from a range of workforces, including white- and blue-collar workers across hospitality, retail, manufacturing, transportation, energy, health, education, law enforcement and military personnel, public administration, information technology, and financial services. Five studies did not report the type of workforce they recruited.

Most reviews (7/11) exclusively reviewed studies of alcohol use; three analyzed alcohol and other drug use (20, 25, 28), and one investigated only other drug use (23). The reviews include many primary studies conducted prior to 2010, and/or focused on specific workforces, intervention modalities and/or evaluation designs, so there was relatively little overlap in the primary studies included in this review and those analyzed in existing reviews.

Effectiveness of workplace-based interventions

For all study information, including sample size, workforce characteristics, follow-up timepoints, and intervention characteristics, see Table 1. For all review characteristics, see Table 2. All primary studies examined the effectiveness of interventions rather than their efficacy. Thirteen primary studies evaluated universal interventions delivered to the entire workforce; 15 were targeted interventions delivered only to employees who met a certain risk threshold. Risk thresholds in these targeted studies included hazardous or harmful drinking (n = 10), cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk (n = 1), and having accessed an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) for mental health or alcohol and/or other drug use (n = 3). Of the 10 interventions delivered to workers who drank at hazardous or harmful levels, three excluded participants if they met criteria for alcohol dependence (41, 43, 49). Broad health promotion interventions were most common (n = 9), followed by brief interventions (BIs; n = 7), psychosocial interventions (n = 7), e-health interventions (n = 4), EAPs (n = 3), drug testing (n = 2), and stepped care (n = 1).

Broad health promotion interventions

There was evidence from both existing reviews and primary studies that universal broad health promotion interventions are associated with a reduction in alcohol use. Nine primary studies evaluated workplace-based broad health promotion interventions which addressed alcohol use amongst other health behaviors such as diet, exercise, stress, sleep, and smoking. Seven were universal interventions; one targeted at-risk drinkers (67); and one targeted employees at risk of developing CVD (46).

Reviews of health promotion interventions

Broad health promotion interventions are not focused on a single health domain or behavior, but address multiple domains/behaviors. Evidence from reviews was mixed. In their overview of reviews, Mewton et al. (28) identified one review that found evidence for health promotion interventions reducing substance use, but Mewton et al. (28) rated this review as low quality. In their systematic review, Osilla et al. (29) identified that two of three RCTs of worksite wellness interventions found an association between the intervention and a reduction in alcohol use. However, a recent meta-analysis of individual Dutch participant data (n = 44,007) found no impact of broad health promotion programs on units of alcohol consumed per week (22).

Primary studies of universal health promotion interventions

Of the seven universal interventions, five found modest but significant reductions in alcohol use following the intervention (39, 47, 48, 53, 54), whereas two did not (33, 58).

Three studies conducted single-group pre/post evaluations of broad health promotion interventions. Goetzel et al. (39) offered a multi-component health promotion intervention comprised of a health risk assessment, online resources, and phone-based health coaching to employees of small US businesses. At 1-year follow-up, a significantly smaller proportion of participants reported high alcohol use (≥15 drinks/week for men or ≥8 drinks/week for women) compared to baseline. LeCheminant et al. (48) evaluated a wellness intervention for US public school district employees, consisting of a health risk assessment, feedback, and educational exercises. Employees who reported using any alcohol at baseline consumed significantly fewer alcoholic drinks per day at 1-year and 2-year follow-up. Schouw et al. (53) similarly evaluated the impact of an intervention consisting of an Health Risk Assessment, feedback, education, and workplace-based resources such as healthy meals and exercise classes offered to South African power plant workers. At 2-year follow-up, a significantly smaller proportion were classified as harmful drinkers compared to baseline.

Of the four evaluations of universal interventions that included control groups, only one also analyzed within-group changes from baseline (i.e., pre-intervention) to follow-up. Findings relating to between-group differences were mixed.

Addley et al. (33) offered Northern Irish public service employees a comprehensive health risk assessment, followed by health and well-being education sessions and online modules and resources. They had two comparison groups: assessment-only, and no intervention. The authors found no significant within-group changes in alcohol use at 12-month follow-up, and no significant differences between the groups. Spicer and Miller (54) evaluated a modified form of the PREVENT health promotion intervention, originally designed for the US Navy, with young (aged 18–29) US railroad workers. PREVENT offered participants 2 days of group-based workshops on interpersonal issues, suicide, stress, smoking and alcohol use. Compared to assessment-only controls, participants offered PREVENT consumed significantly fewer alcoholic drinks in the past 30 days at follow-up (average time between baseline and follow-up assessment was 10.6 months for controls and 8.7 for treatment participants). Kuehl et al. (47) evaluated a safety and health improvement intervention with US law enforcement officers, which consisted of 12 half-hour team-based scripted sessions over 6-months, which addressed lifestyle behaviors such as exercise, diet, and sleep. Compared to a screening-only control group in a difference-in-difference analysis, participants randomized to receive the SHIELD intervention reported a significantly greater reduction in alcohol use from baseline to 12-month follow-up, but not from baseline to 6- or 24-month follow-up. Wierenga et al. (58) implemented the broadest health promotion intervention in Dutch university and hospital workplaces, which included informational posters, free fruit, and/or peer group counseling around work-related issues. The authors did not find a significant difference between intervention and control groups in glasses of alcohol consumed per week at follow-up, most likely because no intervention activities addressed alcohol use.

Primary studies of targeted health promotion interventions

Sieck and Heirich (67) evaluated the impact of a workplace wellness counseling intervention, but were unable to perform within- or between-group inferential statistics due to their small sample size. Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij et al. (46) screened Dutch public service (military, police and hospital) employees for CVD risk, and offered the treatment group a multicomponent lifestyle change intervention. At baseline, 65.4 and 86.6% of their sample did not meet the Dutch physical activity and diet guidelines, respectively; but only 11.8% exceeded the Dutch guidelines for alcohol consumption. At 12-month follow-up, participants offered the intervention reported a significant reduction in excessive alcohol use. However, the screening-only control group also reported a significant and comparable reduction in excessive alcohol use.

Brief interventions

There was evidence from reviews and primary studies that targeted BIs are associated with a reduction in alcohol use. However, evidence for the superiority of BIs over screening alone was mixed.

Reviews of brief interventions

In their systematic review, Kolar and von Treuer (26) concluded that there was no evidence for the effectiveness of workplace-based BIs for alcohol use. However, two other systematic reviews found evidence for the effectiveness of BIs for alcohol use in male-dominated workplaces (27) and for the effectiveness of workplace-based screening and BI (30).

Primary studies of universal brief interventions

Hagger et al. (68) conducted the only evaluation of a BI for all employees who consumed alcohol, not only those who met a certain alcohol use risk threshold. The BI consisted of alcohol use screening, followed by a task to set a goal of keeping alcohol use within World Health Organization guidelines. Participants randomized to receive the BI reported consuming significantly fewer weekly units of alcohol on average at 1-month follow-up than at baseline, while assessment-only controls did not significantly change their alcohol use. Compared to assessment alone, the BI group consumed significantly fewer weekly units of alcohol on average at 1-month follow-up.

Primary studies of targeted brief interventions

The remaining six BIs were offered only to participants who screened as hazardous or harmful drinkers, five of which compared the BI to a control condition. Joseph et al. (34) screened Indian hospital workers (manual laborers) for harmful drinking, and offered a feedback and advice BI to those who screened as moderate- to high-risk. At 4-month follow-up, participants reported significant reductions in alcohol use, desire to drink, and alcohol-related problems, compared to baseline. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution as the authors recruited a small sample (n = 39) and did not have a comparison group. Hermansson et al. (42) evaluated two forms of an alcohol intervention in Swedish transport workers against a screening-only control: one limited, one comprehensive. The limited intervention was a BI consisting of screening, feedback and advice; the comprehensive intervention offered this BI in addition to another assessment and keeping a drinking diary for 4 weeks. Regardless of group assignment, significantly fewer participants screened as harmful drinkers at 12-month follow-up compared to baseline. Similarly, Watson et al. (57) evaluated the impact of a BI consisting of screening and feedback on UK public service workers' alcohol use against screening-only, and found that regardless of group allocation, overall participants reported significantly lower AUDIT scores at 6-month follow-up. Ito et al. (43) evaluated two different BI interventions for harmful (but not dependent) drinking against an information-only control group in (predominantly) blue-collar employees of large Japanese companies. Both intervention groups received two 15-min BI sessions consisting of feedback, information about the risks of harmful alcohol consumption, goal-setting and coping strategies, and one additionally kept a drinking diary for 3 months. Both BI groups significantly reduced their average weekly drinks and binge drinking episodes and increased alcohol-free days at 3- and 12-month follow-up. Addley et al. (33) found that a limited (brief) multicomponent lifestyle intervention was associated with a significant reduction in the proportion of participants reporting excessive alcohol use at 12-month follow-up compared to baseline.

Three studies found that screening alone (42, 57) or screening and information about the negative consequences of heavy alcohol consumption (43) were also associated with significant reductions in alcohol use at follow-up, and were comparable to the BI. Three studies found no benefit of a more comprehensive intervention following a BI; Ito et al. (43) and Hermansson et al. (42) found no additional benefit of keeping a drinking diary for several weeks, and Addley et al. (33) found no additional benefit of seven health coaching sessions, in addition to a BI. Michaud et al. (49) recruited French employees attending required occupational medicine appointments who screened positive for hazardous drinking. Compared to controls who were randomized to receive a self-help booklet following screening, the BI group reported a significantly lower mean score on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and significantly larger reductions in both alcohol use and AUDIT scores at 12-month follow-up. However, equivalent proportions of participants in the control and BI groups reduced their AUDIT score below the harmful threshold. The authors did not conduct within-group analyses.

Psychosocial interventions

Evidence for the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions was mixed. All three primary studies that found a psychosocial intervention was associated with reduced alcohol use evaluated modified forms of the “Team Awareness” intervention (59). However, evidence for the superiority of Team Awareness over control interventions was mixed.

Reviews of psychosocial interventions

Four reviews evaluated psychosocial interventions, which consisted of various combinations of education, problem-solving, role-playing and reinforcement exercises. Lee et al. (27) concluded that there is evidence to support the use of workplace peer-based psychosocial interventions that target alcohol use attitudes to prevent workplace injuries. They did not, however, find evidence for their effectiveness on alcohol use outcomes. In their overview of reviews, Mewton et al. (28) identified one review that included psychosocial skills-training interventions, which found them to be effective in reducing alcohol use. Kolar and von Treuer (26) found mixed evidence for the Team Awareness psychosocial intervention (59), and argued that it should be tailored to each workplace to be effective. Burnhams et al. (25) did not differentiate psychosocial interventions from other modalities in their analysis.

Primary studies of universal psychosocial interventions

Six out of seven psychosocial interventions were universal, three of which found some evidence of effectiveness in reducing alcohol use. Two studies evaluated an educational harm minimization intervention in Swedish workplaces, one short (2 × 45-min lectures) with finance/insurance salespeople (55), the other longer (2 x half-day sessions) with public service workers (56). Neither evaluation found that the intervention was associated with a reduction in alcohol use or AUDIT scores. Pidd et al. (50) evaluated a multi-component prevention, early intervention and treatment program for alcohol harm reduction in male-dominated Australian manufacturing worksites, and found no overall reduction in AUDIT scores at 12- or 24-month follow-ups. Reynolds and Bennett (51) evaluated a shortened form of the “Team Awareness” intervention with US small business employees. The original Team Awareness intervention offered skills-based training for referring peers to support for substance use, team building, and management of stress, as well as information about participants' employer's substance use policy (59). The authors found that participants reported drinking significantly less frequently, and on significantly fewer days out of the past month, at 6-month follow-up. The two remaining studies did not analyse within-group changes from baseline to follow-up (36, 38).

Three studies found that universal psychosocial interventions did not have a significant impact on alcohol use, and were comparable to assessment-only controls (50, 55, 56). In contrast, three studies reported some benefits of universal psychosocial interventions for some alcohol-related outcomes. Reynolds and Bennett (51) compared Team Awareness to a broad educational health promotion program (both delivered in one 4-h session), and screening-only control. Both intervention conditions were associated with comparable reductions in alcohol use, and were superior to screening alone. Broome and Bennett (36) delivered Team Awareness in three 2-h sessions to young US restaurant workers and assessed heavy drinking outcomes against a screening-only control group. The authors did not find a significant difference between Team Awareness and control participants in heavy drinking, but Team Awareness participants reported a significantly larger reduction in recurrent heavy drinking (heavy drinking on 5 or more days/month) at 6- but not 12-month follow-up, compared to controls. Team Awareness participants also reported significantly fewer alcohol-related problems at 12-month follow-up compared to controls. Burnhams et al. (38) delivered Team Awareness in eight 1-h sessions to South African public service employees, and compared them to those randomized to receive a 1-h general wellness talk. They found a significant group by time interaction, as Team Awareness participants reported a reduction, and control participants an increase, in binge drinking days in the past month from baseline to 3-month follow-up.

Primary studies of targeted psychosocial interventions

Harada et al. (41) conducted the only evaluation of a targeted psychosocial intervention for high-risk (but not dependent) drinkers in white-collar Japanese workplaces. They evaluated the “Haizen Alcoholism Prevention Program” (HAPPY) against a modified version (“HAPPY Plus”). The original HAPPY intervention offered three group sessions, consisting of alcohol use assessments, goal-setting, information about the health impacts of alcohol use, and keeping an alcohol-use diary. HAPPY Plus added group discussions, interactive education about health impacts to enhance participants' perception of alcohol use risks, and stress management. Both groups significantly reduced their average daily alcohol consumption and AUDIT scores from baseline to 3-month follow-up, but the groups were not significantly different at follow-up.

e-health interventions

Evidence from reviews suggested that e-health interventions may be effective for reducing alcohol use. However, the findings of four primary studies did not support this conclusion.

Reviews of e-health interventions

Two systematic reviews and one meta-analysis reported mixed evidence for the effectiveness of e-health interventions on alcohol use and binge drinking. Schulte et al. (30) reviewed BIs for alcohol use, including four web-based BIs, three of which found some evidence of effectiveness in terms of alcohol use reduction. Kolar and von Treuer (26) identified two evaluations of web-based interventions, both of which were found to be effective in reducing alcohol use. In their meta-analysis, Phillips et al. (21) identified two occupational e-health interventions for alcohol use, and found no significant impact of the interventions compared to passive control groups in a pooled analysis.

Primary studies of universal e-health interventions

Two studies evaluated broad health promotion programs that included web-based resources such as health-related articles and videos, and smoking and weight-loss behavior change programs (39) and online resources such as a personal trainer, monitoring resources and motivational messages (33). Goetzel et al. (39) found a significant reduction in harmful alcohol use at 1-year follow-up in a single-group pre/post study, whereas Addley et al. (33) found no impact of the intervention over screening alone or screening and feedback.

Primary studies of targeted e-health interventions

Two e-health interventions were targeted to high-risk drinkers. Brendryen et al. (35) evaluated a web-based self-help intervention for harmful drinking (using the Fast Alcohol Screening Test) consisting of feedback and 62 online sessions (with email reminders) over 6-months against a feedback and information control. Sessions were interactive and up to 10 min long, and involved quizzes and cognitive behavioral tasks. Participants could also opt-in to receive supportive text messages, but the authors did not report the number of participants that opted-in. Participants in both conditions significantly reduced their weekly alcohol use between baseline and 6-month follow-up, and were not significantly different at follow-up. Khadjesari et al. (45) screened employees in a large UK organization for a range of health behaviors and recruited those who screened as harmful drinkers on the AUDIT. Participants were randomized to receive feedback on all health behaviors plus a link to the multi-component web-based alcohol use intervention Down Your Drink (intervention), or feedback on all health behaviors except alcohol use (control). The authors did not analyses within-group changes from baseline to 3-month follow-up, and did not find a significant difference in past week alcohol use or AUDIT scores between the groups.

Employee assistance programs

Reviews and primary studies of EAPs often focused on workplace-level outcomes (e.g., accidents, insurance claims) and/or cross-sectional evaluation designs. There is no consistent evidence that EAPs are associated with a reduction in substance use.

Reviews of EAPs

Two reviews analyzed the effectiveness of EAPs, but the quality of evidence was poor. In their recent review of employer-led interventions for other drug use, Akanbi et al. (23) analyzed five studies that evaluated an EAP, two of which were cross-sectional. The other three studies assessed the effectiveness of an EAP on reducing workplace accidents or worker compensation claims but did not measure drug use. Weenink et al. (20) reviewed the effectiveness of mandated rehabilitation programs for clinicians whose work performance had been affected by substance use. Although completion rates were high (80–90%) and most clinicians returned to work following treatment, their analysis primarily focused on work-related outcomes, not alcohol and/or other drug use.

Primary studies of targeted EAPs

As only employees who seek help receive an intervention, all four EAP interventions were targeted. Only one study analyzed within-group changes in substance use from baseline to follow-up. Richmond et al. (52) compared risky alcohol use in US state government employees who had accessed their EAP to comparison participants who matched the EAP group on key characteristics such as demographic and employment characteristics. The EAP group did not report significantly different AUDIT scores, and were not significantly different from controls, at follow-up (range: 2- to 12-months).

Sieck and Heirich (67) evaluated the impact of a health promotion and substance use prevention intervention in conjunction with an EAP, but were unable to perform inferential analyses due to their small sample size. Jones et al. (44) recruited UK reserve forces personnel who had returned from deployment and accessed military-provided mental health treatment. The authors compared substance use outcomes in personnel whose mental health condition was attributable to their military service (treatment group) to those with non-attributable mental health issues (control group). Treatment group participants reported significantly higher AUDIT scores at baseline and follow-up compared to controls. Burgess et al. (37) evaluated the impact of an EAP at a Russian manufacturing worksite against a non-equivalent industrial worksite. At the intervention worksite, participants who self-identified or were identified by their employer as requiring an alcohol-use intervention were referred to the EAP. The authors found a significant condition by time interaction, whereby EAP participants significantly reduced their AUDIT scores from baseline to 90-day follow-up, but controls did not. However, EAP participants reported a substantially higher mean AUDIT score at baseline (13.79) than controls (3.59).

Substance use testing

There was a focus on workplace-level outcomes (e.g., accidents, insurance claims) and/or cross-sectional evaluation designs in the substance use testing literature. There was little evidence to support workplace-based testing.

Reviews of substance use testing

Four reviews analyzed the effectiveness of workplace substance use testing, but these analyses tended to use poor quality studies and/or focus on workplace-level outcomes such as accidents and injuries. Lee et al. (27) concluded that workplace alcohol testing was not effective to reduce alcohol use in male-dominated (i.e., on average >70% male at the industry level) workplaces such as construction, mining, transport and manufacturing. In contrast, Kolar and von Treuer (26) argued that random alcohol and other drug testing is highly effective; however, only one of the three studies they reviewed reported that testing reduced substance use at the individual level. In their overview of reviews, Mewton, Visontay (28) found mixed evidence for the effectiveness of workplace substance use testing; the highest quality review in their analysis that found testing to be effective reported positive impacts on workplace injuries, not substance use per se. Akanbi et al. (23) reviewed 11 evaluations of workplace drug testing programs, five of which measured substance use. Two of these studies found an association between testing and lower rates of employee substance use, but both were cross-sectional designs and did not assess change over time.

Primary studies of universal substance use testing

Two primary studies evaluated the impact of universal workplace substance use testing. Sieck and Heirich (67) reported that an increase in random drug testing (RDT) at a manufacturing worksite did not significantly impact the proportion of employees reporting at-risk alcohol use. However, they measured use at each time point using anonymous surveys that were not linked to individuals, so it is unclear to what extent the baseline and follow-up survey respondents overlap. Gómez-Recasens et al. (40) introduced universal alcohol and other drug monitoring (self-report and urine screening) at multiple Spanish industrial worksites and evaluated its effectiveness in a single group pre-/post-intervention analysis. The proportion of employees reporting risky alcohol use significantly declined from baseline to 1-year follow-up, and from 1-year to 2-year follow-up (reduction maintained at 3-year follow-up). The proportion of employees reporting any other drug use did not significantly change from baseline to 1-year follow-up or 2- to 3-year follow-up, and modestly but significantly increased from 1-year to 2-year follow-up. However, Gómez-Recasens et al. (40) implemented universal substance use monitoring as part of a stepped-care intervention, so these effects may be attributable to the other interventions offered to employees (described below).

Stepped-care

Only one article described the effectiveness of a stepped-care intervention. Gómez-Recasens et al. (40) introduced universal alcohol and other drug monitoring in Spanish industrial worksites and referred employees who screened positive for risky alcohol use, or any other drug use to further intervention. Depending on their use severity, employees were offered a brief intervention or referral to specialist substance use treatment. As described above, the stepped-care model was associated with a significant reduction in risky alcohol use, although it is unclear which component/s this effect can be attributed to.

Cost-effectiveness

Only three studies conducted an economic evaluation. Goetzel et al. (39) evaluated the return-on-investment of a universal intervention addressing ten health risk behaviors, including poor diet, insufficient exercise, smoking and harmful alcohol use. The authors did not use a control group, instead comparing predicted and actual changes in employee health risk scores from baseline to 1-year follow-up and the associated financial savings from reductions in health risks through use of an existing return on investment model. The statistically significant reductions in seven risk factors (obesity, poor eating habits, poor physical activity, tobacco use, high alcohol consumption, high stress and depression) and non-significant improvements in high blood pressure, high total cholesterol and high blood glucose were estimated to result in medical and productivity cost savings and a total return-on-investment of $2.03 for every $1 spent on the intervention. The contribution of reduced alcohol consumption to the overall financial benefit is unclear. Khadjesari et al. (45) compared outcomes including preference based utility values (EQ-5D) and the cost of self-reported health care resource use and number of sick days between employees receiving feedback on alcohol in addition to other health risks compared to employees only receiving feedback on health risks. At 3-month follow-up there were no significant differences in AUDIT scores, utility values or costs. Watson et al. (57) conducted a pilot trial of a BI delivered by an occupational health nurse which resulted in a mean savings of £344.5 per intervention participant, and a very small average benefit of 0.008 quality adjusted life years (QALYs) compared to a screening only control group.

Workforce characteristics associated with intervention outcomes

As discussed, the primary studies reviewed were conducted across a range of industries. No studies allowed for a direct comparison between industries, and only one study analyzed the moderating effect of worker roles (42). A limited range of other workforce characteristics were examined across a small number of studies, including age, sex, role characteristics, substance use severity, attitudes, and socioeconomic status.

Age

Age was associated with intervention outcomes in two of three primary studies that analyzed it as a moderator. Hermansson et al. (42) and Michaud et al. (49) found that age was significantly associated with change in AUDIT score from baseline to follow-up, such that younger participants were more likely to report a score reduction at follow-up. Hermansson et al. (42) analyzed the relationship between age and difference in AUDIT score from baseline to follow-up independent of other variables, whereas Michaud, Kunz (49) controlled for AUDIT score at baseline and group allocation. Kuehl et al. (47) did not find that age moderated intervention outcomes.

Sex

There were mixed findings for the impact of sex on intervention outcomes. Broome and Bennett (36) found that male participants reported significantly more recurring heavy drinking (5 or more days in the past 30 of consuming 5 or more drinks) at baseline compared to female participants but did not examine the impact of sex on changes in alcohol use from baseline to follow-up. Three studies found that sex did not moderate changes in substance use from 12 to 24 months (42, 47, 50), whereas two studies reported greater reductions in alcohol use amongst male participants compared to female participants. Michaud et al. (49) found that baseline AUDIT scores were significantly higher amongst male participants compared to female participants, and that only males in the intervention group significantly reduced their alcohol use at follow-up compared to (male) controls. Similarly, Sieck and Heirich (67) found that women reported significantly higher perceived risks of alcohol use and significantly lower alcohol consumption at baseline compared to men, and that men reported significantly larger reductions in their alcohol use at follow-up compared to women.

Role characteristics

Hermansson et al. (42) did not find that the timing of shiftwork (day vs. night) or whether participants were employed in a manual or non-manual role impacted intervention outcomes.

Substance use severity

Evidence for the moderating effect of substance use severity on intervention outcomes was weak. Tinghög and Tinghög (56) did not find an overall intervention effect, but found that amongst the heaviest drinkers (≥6.4 g/day), only those allocated to receive the intervention significantly reduced their alcohol use at follow-up relative to heavy-drinking controls. There was no effect of group allocation amongst the lightest drinkers (≤4.14 g/day). However, Tinghög (55) did not find the same effect of heavy drinking. Richmond et al. (52) found that regardless of treatment condition, baseline AUDIT scores predicted scores at follow-up, whereas Michaud et al. (49) found no association between baseline AUDIT scores and intervention outcomes.

Attitudes

Reynolds and Bennett (51) found that changes in attitudes toward help-seeking predicted whether employees' sought counseling for alcohol use but did not predict alcohol use outcomes.

Socioeconomic status

Coenen et al. (22) found that socioeconomic status did not predict compliance with workplace-based interventions or their effectiveness for reducing alcohol use.

Barriers and facilitators

No primary studies or reviews directly examined the barriers to and/or facilitators for implementing workplace-based interventions. Lee et al. (27) and Schulte et al. (30) noted in their reviews that male employees may be more likely to experience issues with alcohol use, but less likely to seek help for them, compared to female employees. Schulte et al. (30) and Watson et al. (57) identified concerns around confidentiality and stigma as barriers to workplace-based alcohol and other drug screening, as employees may be concerned about consequences for their career if they disclose a substance use issue.

Tailoring and ease of implementation/engagement emerged as facilitators. In their review, Kolar and von Treuer (26) argued that interventions likely need to be tailored to each workplace to be effective. Echoing this conclusion, Wierenga et al. (58) found that participants reported a preference for personalized interventions. Wierenga et al. (58) also found that employees preferred interventions that were simple, easy and cheap to implement, and those that were easily accessible and did not incur significant time costs (e.g., interventions integrated into existing meetings).

Study quality

See Table 1 for primary study quality ratings. Half (14/28) of the included studies were rated “poor” quality according to Korokakis et al.'s (24) modified version of the Downs and Black Quality Index (1998), six were “fair” quality, and eight were “good” quality. No primary studies were rated “excellent”. In general, these scores reflect low scores for internal validity (i.e., high risk of bias) and underpowered studies.

See Table 2 for review quality ratings. Of the 11 reviews, two included a meta-analysis; one scored 7/8 (22) and the other scored 8/8 (21) on the NIH quality assessment tool (31). Of the nine reviews rated out of 7, one scored 7 (27), two scored 6, three scored 5, and three scored 4.

The quality scores for the three included economic evaluations ranged from fair (7.5/10 points) for Khadjesari et al. (45) to poor for Goetzel et al. (39) (5.5/10 points) and Watsonet al. (57) (4/10 points). Watson et al. (57) did not identify the perspective of the analysis or identify the sources of unit costs. Goetzel et al. (39) did not evaluate clinical or quality of life outcomes and used an existing economic model without details of the unit costs included. Khadjesari et al. (45) included healthcare resource use and sick leave costs reported by participants but did not include the cost of the intervention.

Discussion

Given considerable changes in the nature of the workplace and working arrangements, particularly in the last decade, this review provides a timely synthesis of the international evidence regarding the efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of problematic substance use. Over the last decade, interventions have been tested across a broad range of workforces, including public servants, young restaurant staff, and manufacturing workers. A range of reviews of workplace-based interventions have also been published with differing focus points including occupational medicine, BIs, and male-dominated workplaces. The vast majority of research focused on alcohol use.

Heterogeneity between studies regarding workforce (e.g., white or blue collar; industry; organization size), intervention design (e.g., universal or targeted; focused on substance use or addressed a range of health behaviors; single- or multi-component) and evaluation approach (e.g., study design; measures used; analysis of within- or between-groups differences) limited the degree to which the data could be synthesized to draw robust conclusions. In addition, most primary studies were rated as poor quality. Although there was insufficient (and mixed) evidence to determine the overall effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace-based interventions for problematic substance use, there was some promising evidence to support workplace-based universal broad health promotion interventions, targeted BIs, and universal screening.

Consistent with earlier reviews (28, 29), this review found evidence that universal broad health promotion interventions are associated with a reduction in substance use. Most (5/7) universal health promotion interventions were associated with a reduction in alcohol use, and two studies of a psychosocial alcohol-focused intervention (Team Awareness) found it to be equivalent to a broad health and wellness intervention on at least one outcome measure (38, 51). However, the quality of these studies tended to be poor; only 4/7 studies included a control group. Workplace wellness programs are increasingly common, particularly in larger US organizations (69, 70). However, these programs do not consistently address substance use beyond smoking (71). There is some evidence that workplace wellness interventions can improve a range of health behaviors (72), but more high-quality evidence is needed to determine their effectiveness for substance use.

All but one of the primary studies that evaluated a BI examined targeted interventions, and all found some evidence of effectiveness in reducing alcohol use. Moreover, four evaluations of more intensive intervention modalities found that control BIs were associated with equivalent reductions in alcohol use as compared to intensive interventions (35, 42, 43, 46). However, there was mixed evidence with regard to the superiority of BIs over screening alone, as 3/5 BI evaluations that included a control group found no significant differences between intervention and control at follow-up. Inconsistent evidence for the effectiveness of BIs for alcohol use could be due to heterogeneity in intervention approach (e.g., motivational vs. informational) and intensity (e.g., 5 vs. 60+ minutes), comparison groups (e.g., screening-only vs. screening and information/feedback), severity of substance use at baseline (e.g., low- vs. high-risk), or lack of consideration for the cultural context in which the BI was applied (73).

There was comparatively weak evidence to support the use of workplace-based psychosocial or e-health interventions. The most promising evidence from primary studies of psychosocial interventions was for Team Awareness (59), but 2/3 studies found that a general health intervention produced comparable outcomes. Of the four reviews that assessed psychosocial interventions, only Mewton et al. (28) found evidence of their effectiveness, specifically for skills-based interventions. Consistent with three previous reviews (21, 26, 30), no significant differences were found between intervention and control groups in three of four evaluations of e-health interventions (35, 45) or those with web-based components (33). Phillips et al. (21) note that attrition rates are often high in e-health interventions; indeed, only 3% of Khadjesari et al.'s (45) treatment group registered for the intervention website (Down Your Drink), and only five participants (12% of the treatment group) completed all 62 web sessions in Brendryen et al.'s (35) study. In addition, Wierenga et al. (58) reported that participants did not engage with the online components of their multicomponent intervention – they did not visit the website, or read emails about the program. Engagement should be a key consideration for implementation of e-health interventions, as they provide a range of benefits over face-to-face intervention modalities, such as providing accessibility and anonymity to participants who would otherwise be unable or unwilling to seek help, and reducing healthcare costs (74).

Unfortunately at this time, the quality of primary studies and those included in reviews were particularly poor, and cannot be used to draw robust conclusions about the effectiveness of Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) or workplace substance use testing. In all four EAP evaluations, participants self-selected into treatment, follow-up periods varied within and between EAP and comparison groups, the treatment offered to EAP participants was unclear, and comparison groups were systematically different from EAP groups. The lack of evidence on the effectiveness of EAPs for substance use may be explained by a focus on workplace-level outcomes such as absenteeism in EAP evaluations, driven by organizations' need to demonstrate return-on-investment (75). Similarly, evaluations of workplace substance use testing tend to focus on workplace-level safety outcomes and/or use cross-sectional designs, limiting their utility for determining the effect of testing on employees' substance use (76).

Six primary studies (35, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49, 57) and two reviews (27, 28) found that screening alone was associated with a significant reduction in substance use, suggesting that screening is itself a substance use intervention. Indeed, a meta-analysis of the impact of screening in the absence of any subsequent intervention found that completing an assessment was associated with a significant reduction in alcohol use (77). In settings such as primary healthcare, screening is used in conjunction with a BI and/or specialist referral to safely guide people using substances at harmful levels into treatment (78), an approach that has been underutilized in the workplace (79). It is crucial that workplaces use effective screening measures to identify at-risk employees to facilitate early intervention (80).

Few primary studies analyzed workforce characteristics as moderators of treatment outcomes. There was mixed evidence for sex, age and substance use severity moderating intervention outcomes; however, it appears that participants reporting heavier substance use at baseline (who tend to be young and/or male) are more likely to report a reduction at follow-up.

The workplace is a complex intervention context as employers must balance their duty of care to employees (81) against safety concerns resulting from substance-induced impairment (76, 82, 83). It is therefore important to consider the barriers and facilitators to implementing a substance use intervention in the workplace alongside evaluating effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Unfortunately, few primary studies or reviews have considered implementation factors. However, the overwhelming focus on alcohol use outcomes (27/28 primary studies) suggests that addressing other drug use in the workplace is more challenging. Lack of engagement with e-health interventions, heavier use and reluctance to seek help amongst male employees (compared to female employees), and concerns around confidentiality, emerged as barriers. Intervention tailoring, and ease of implementation and engagement were identified as facilitators in the workplace. More evidence on workplace-specific implementation factors is needed, ideally through process evaluations.

The scarcity of high-quality economic evaluations of workplace interventions to reduce substance use may be due to the limited time-horizons, difficulty collecting cost and outcome data alongside trials or the complexity of the workplace as a setting for intervention. Businesses may also rely on previous literature suggesting health promotion programs result in lower absenteeism and health care costs as sufficient evidence for implementation (84), despite more recent research suggesting that study quality may influence findings (85).

Primary studies and reviews conducted over the past decade have revealed some promising evidence for universal health promotion interventions, targeted brief interventions, and universal substance use screening. The sparse evidence around factors influencing implementation suggests that preserving confidentiality (and assuring employees that their disclosures will not be provided to their employer), tailoring interventions to each workplace, and making interventions easy to implement and engage with may assist implementation. There is a need for future studies to address implementation, as well as use of substances other than alcohol.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

AM, MA, and JS developed the database search strategy, screened articles, extracted data from included articles, analyzed extracted data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. KD analyzed extracted data and summarized the findings of the included systematic reviews. KM revised the database search strategy and drafted and revised the manuscript. M-LC drafted and revised the economic analyses in the paper and reviewed the draft manuscript. AF and CM revised the database search strategy and reviewed the draft manuscript. FK-L, MS, LH, NP, and MT reviewed the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding for this review was provided by icare NSW. KM, CM, FK-L, EB, and MT received fellowship funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1051119/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Smith DE, Marzilli L, Davidson LD. Strategies of Drug Prevention in the Workplace: an International Perspective of Drug Testing and Employee Assistance Programs. Textbook Addiction Treatment. New York, NY: Springer (2021). p. 733-56. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36391-8_51

2. Goplerud E, Hodge S, Benham T. A Substance use cost calculator for us employers with an emphasis on prescription pain medication misuse. J Occupat Environ Med. (2017) 59:1063. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001157

3. Frone MR. Employee psychoactive substance involvement: historical context, key findings, and future directions. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. (2019) 6:273–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015231

4. Roche A, Pidd K, Kostadinov V. Alcohol-and drug-related absenteeism: a costly problem. Aust N Z J Public Health. (2016) 40:236–8. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12414

5. Sorge JT, Young M, Maloney-Hall B, Sherk A, Kent P, Zhao J, et al. Estimation of the impacts of substance use on workplace productivity: a hybrid human capital and prevalence-based approach applied to Canada. Can J Public Health. (2020) 111:202–11. doi: 10.17269/s41997-019-00271-8

6. Hoffmann J, Larison C. Drug use, workplace accidents and employee turnover. J Drug Issues. (1999) 29:341–64. doi: 10.1177/002204269902900212

7. Elliott K, Shelley K. Effects of drugs and alcohol on behavior, job performance, and workplace safety. J Employ Counsel. (2006) 43:130–4. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1920.2006.tb00012.x

8. Frone MR. Relations of negative and positive work experiences to employee alcohol use: testing the intervening role of negative and positive work Rumination. J Occup Health Psychol. (2015) 20:148. doi: 10.1037/a0038375

9. Frone MR, Brown AL. Workplace substance-use norms as predictors of employee substance use and impairment: a survey of us workers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2010) 71:526–34. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.526

10. Biron M, Bamberger PA, Noyman T. Work-related risk factors and employee substance use: insights from a sample of israeli blue-collar workers. J Occup Health Psychol. (2011) 16:247. doi: 10.1037/a0022708

11. Bufquin D, Park J-Y, Back RM, de Souza Meira JV, Hight SK. Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: an examination of restaurant employees during Covid-19. Int J Hospital Manag. (2021) 93:102764. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102764

12. Frone MR. Are work stressors related to employee substance use? the importance of temporal context assessments of alcohol and illicit drug use. J App Psychol. (2008) 93:199. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.199

13. Ames GM, Bennett JB. Prevention interventions of alcohol problems in the workplace: a review and guiding framework. Alcohol Res Health. (2011) 34:175–87.

14. Roche AM, Lee NK, Battams S, Fischer JA, Cameron J, McEntee A. Alcohol use among workers in male-dominated industries: a systematic review of risk factors. Saf Sci. (2015) 78:124–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2015.04.007

15. Pidd K, Duraisingam V, Roche A, Trifonoff A. Young construction workers: substance use, mental health, and workplace psychosocial factors. Adv Dual Diagn. (2017). doi: 10.1108/ADD-08-2017-0013

16. Frone MR. Predictors of overall and on-the-job substance use among young workers. J Occup Health Psychol. (2003) 8:39. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.8.1.39

17. Roche AM, Fischer J, Pidd K, Lee N, Battams S, Nicholas R. Workplace Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders in Male-Dominated Industries: A Systematic Literature Review. Adelaide: National Centre for Education and Training on Addiction (2012).

18. Lee NK, Roche A, Duraisingam V, Fischer JA, Cameron J. effective interventions for mental health in male-dominated workplaces. Mental Health Review Journal. (2014). doi: 10.1108/MHRJ-09-2014-0034

19. Watterson JR, Gabbe B, Rosenfeld J, Ball H, Romero L, Dietze P. Workplace intervention programmes for decreasing alcohol use in military personnel: a systematic review. BMJ Mil Health. (2021) 167:192–200. doi: 10.1136/bmjmilitary-2020-001584

20. Weenink J-W, Kool RB, Bartels RH, Westert GP. Getting back on track: a systematic review of the outcomes of remediation and rehabilitation programmes for healthcare professionals with performance concerns. BMJ Qual Saf. (2017) 26:1004–14. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006710

21. Phillips EA. Gordeev, V, Schreyögg J. Effectiveness of occupational e-mental health interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scandinavian J Work Environ Health. (2019) 45:560–76. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3839

22. Coenen P, Robroek SJ, Van Der Beek AJ, Boot CR, Van Lenthe FJ, Burdorf A, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in effectiveness of and compliance to workplace health promotion programs: an individual participant data (Ipd) meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutri Physical Activ. (2020) 17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-01002-w

23. Akanbi MO, Iroz CB, O'Dwyer LC, Rivera AS, McHugh MC, A. Systematic review of the effectiveness of employer-led interventions for drug misuse. J Occup Health. (2020) 62:e12133. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12133

24. Korakakis V, Whiteley R, Tzavara A, Malliaropoulos N. The effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in common lower limb conditions: a systematic review including quantification of patient-rated pain reduction. Br J Sports Med. (2018) 52:387–407. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097347

25. Burnhams NH, Musekiwa A, Parry C, London L. A systematic review of evidence-based workplace prevention programmes that address substance abuse and hiv risk behaviours. Af J Drug Alcohol Stud. (2013) 12:1.

26. Kolar C, von Treuer K. Alcohol misuse interventions in the workplace: a systematic review of workplace and sports management alcohol interventions. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2015) 13:563–83. doi: 10.1007/s11469-015-9558-x

27. Lee NK, Roche AM, Duraisingam V, Fischer J, Cameron J, Pidd K, et al. Systematic review of alcohol interventions among workers in male-dominated industries. Journal of Men's Health. (2014) 11:53–63. doi: 10.1089/jomh.2014.0008

28. Mewton L, Visontay R, Chapman C, Newton N, Slade T, Kay-Lambkin F, et al. Universal prevention of alcohol and drug use: an overview of reviews in an australian context. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2018) 37:S435–S69. doi: 10.1111/dar.12694

29. Osilla KC, Van Busum K, Schnyer C, Larkin JW, Eibner C, Mattke S. Systematic review of the impact of worksite wellness programs. Am J Manag Care. (2012) 18:e68–81.

30. Schulte B, O'Donnell AJ, Kastner S, Schmidt CS, Schäfer I, Reimer J. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in workplace settings and social services: a comparison of literature. Front Psychiatry. (2014) 5:131. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00131

31. National Institutes of Health. Study Quality Assessment Tools (2021). Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed December 15, 2021).

32. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2015).

33. Addley K, Boyd S, Kerr R, McQuillan P, Houdmont J, McCrory M. The impact of two workplace-based health risk appraisal interventions on employee lifestyle parameters, mental health and work ability: results of a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. (2014) 29:247–58. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt113

34. Joseph J, Das K, Sharma S, Basu D. Assist-linked alcohol screening and brief intervention in indian work-place setting: result of a 4 month follow-up. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. (2014) 30:80–6.

35. Brendryen H, Johansen A, Duckert F, Nesvåg S. A pilot randomized controlled trial of an internet-based alcohol intervention in a workplace setting. Int J Behav Med. (2017) 24:768–77. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9665-0

36. Broome KM, Bennett JB. Reducing heavy alcohol consumption in young restaurant workers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. (2011) 72:117–24. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.117

37. Burgess K, Lennox R, Sharar DA, Shtoulman A. A substance abuse intervention program at a large russian manufacturing worksite. J Workplace Behav Health. (2015) 30:138–53. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2015.1000159

38. Burnhams NH, London L, Laubscher R, Nel E, Parry C. Results of a cluster randomised controlled trial to reduce risky use of alcohol, alcohol-related hiv risks and improve help-seeking behaviour among safety and security employees in the Western Cape, South Africa. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2015) 10:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13011-015-0014-5

39. Goetzel RZ, Tabrizi M, Henke RM, Benevent R. Brockbank CvS, Stinson K, et al. Estimating the return on investment from a health risk management program offered to small colorado-based employers journal of occupational and environmental medicine. Am Coll Occupat Environ Med. (2014) 56:554. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000152

40. Gómez-Recasens M, Alfaro-Barrio S, Tarro L, Llauradó E, Solà R, A. Workplace intervention to reduce alcohol and drug consumption: a nonrandomized single-group study. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6133-y

41. Harada K, Moriyama M, Uno M, Kobayashi T, Yuzuriha T. Effects of a revised moderate drinking program for enhancing behavior modification in the workplace for heavy drinkers: a randomized controlled trial in Japan. Health. (2015) 7:1601. doi: 10.4236/health.2015.712173

42. Hermansson U, Helander A, Brandt L, Huss A, Rönnberg S. Screening and brief intervention for risky alcohol consumption in the workplace: results of a 1-year randomized controlled study. Alcohol Alcoholism. (2010) 45:252–7. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq021

43. Ito C, Yuzuriha T, Noda T, Ojima T, Hiro H, Higuchi S. brief intervention in the workplace for heavy drinkers: a randomized clinical trial in Japan. Alcohol Alcoholism. (2015) 50:90. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu090

44. Jones N, Wink P, Brown R, Berrecloth D, Abson E, Doyle J, et al. A clinical follow-up study of reserve forces personnel treated for mental health problems following demobilisation. Journal of Mental Health. (2011) 20:136–45. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.541299

45. Khadjesari Z, Freemantle N, Linke S, Hunter R, Murray E. Health on the web: randomised controlled trial of online screening and brief alcohol intervention delivered in a workplace setting. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e112553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112553

46. Kouwenhoven-Pasmooij TA, Robroek SJ, Kraaijenhagen RA, Helmhout PH, Nieboer D, Burdorf A, et al. Effectiveness of the blended-care lifestyle intervention ‘perfectfit': a cluster randomised trial in employees at risk for cardiovascular diseases. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5633-0

47. Kuehl KS, Elliot DL, MacKinnon DP, O'Rourke HP, DeFrancesco C, Miočević M, et al. The shield (safety & health improvement: enhancing law enforcement departments) study: mixed methods longitudinal findings. J Occupat Environ Med. (2016) 58:492. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000716

48. LeCheminant J, Merrill RM, Masterson TD. Changes in behaviors and outcomes among school-based employees in a wellness program. Health Promot Pract. (2017) 18:895–901. doi: 10.1177/1524839917716931

49. Michaud P, Kunz V, Demortière G, Lancrenon S, Carré A, Ménard C, et al. Efficiency of brief interventions on alcohol-related risks in occupational medicine. Global Health Promot. (2013) 20(2_suppl):99–105. doi: 10.1177/1757975913483339

50. Pidd K, Roche A, Cameron J, Lee N, Jenner L, Duraisingam V. Workplace alcohol Harm reduction intervention in Australia: cluster non-randomised controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2018) 37:502–13. doi: 10.1111/dar.12660

51. Reynolds GS, Bennett JB. A cluster randomized trial of alcohol prevention in small businesses: a cascade model of help seeking and risk reduction. Am J Health Promot. (2015) 29:182–91. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.121212-QUAN-600

52. Richmond MK, Pampel FC, Wood RC, Nunes AP. Impact of employee assistance services on depression, anxiety, and risky alcohol use: a quasi-experimental study. J Occupat Environ Med. (2016) 58:641–50. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000744

53. Schouw D, Mash R, Kolbe-Alexander T. Changes in risk factors for non-communicable diseases associated with the ‘healthy choices at work'programme, South Africa. Glob Health Action. (2020) 13:1827363. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1827363

54. Spicer RS, Miller TR. the evaluation of a workplace program to prevent substance abuse: challenges and findings. J Prim Prev. (2016) 37:329–43. doi: 10.1007/s10935-016-0434-7

55. Tinghög ME. The workplace as an arena for universal alcohol prevention–what can we expect? Evaluat Short EducatIntervent Work. (2014) 47:543–51. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131733

56. Tinghög ME, Tinghög P. Preventing alcohol problems and improving drinking habits among employees: an evaluation of alcohol education. Work. (2016) 53:421–8. doi: 10.3233/WOR-152231

57. Watson H, Godfrey C, McFadyen A, McArthur K, Stevenson M, Holloway A. Screening and brief intervention delivery in the workplace to reduce alcohol-related harm: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2015) 52:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.013

58. Wierenga D, Engbers L, Van Empelen P, De Moes K, Wittink H, Gründemann R, et al. The implementation of multiple lifestyle interventions in two organizations: a process evaluation. J Occupat Environ Med. (2014) 56:1195. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000241

59. Bennett JB, Patterson CR, Reynolds GS, Wiitala WL, Lehman WE. Team awareness, problem drinking, and drinking climate: workplace social health promotion in a policy context. Am J Health Promot. (2004) 19:103–13. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.2.103

60. Cook RF, Back AS, Trudeau J. Preventing alcohol use problems among blue-collar workers: A field test of the Working People program. Subst Use Misuse. (1996) 31:255–75. doi: 10.3109/10826089609045812

61. Matano RA, Koopman C, Wanat SF, Winzelberg AJ, Whitsell SD, Westrup D, et al. (2007). A pilot study of an interactive web site in the workplace for reducing alcohol consumption. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2007) 32:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.020

62. Billings DW, Cook RF, Hendrickson A, Dove DC. A Web-based approach to managing stress and mood disorders in the workforce. J Occup Environ Med. (2008) 50:960–8. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31816c435b

63. Deitz D, Cook R, Hersch R. Workplace health promotion and utilization of health services: follow-up data findings. J Behav Health Serv Res. (2005) 32:306–19. doi: 10.1007/BF02291830

64. Walters ST, Woodall WG. Mailed feedback reduces consumption among moderate drinkers who are employed. Prevent Sci. (2003) 4:287–94. doi: 10.1023/A:1026024400450

65. Doumas DM, Hannah E. Preventing high-risk drinking in youth in the workplace: A web-based normative feedback program. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2008) 34:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.006

66. Webb G, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R, Havard A. A systematic review of work-place interventions for alcohol-related problems. Addiction. (2009) 104:365–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02472.x

67. Sieck CJ, Heirich M. Focusing attention on substance abuse in the workplace: a comparison of three workplace interventions. J Workplace Behav Health. (2010) 25:72–87. doi: 10.1080/15555240903358744

68. Hagger MS, Lonsdale A, Chatzisarantis NL. Effectiveness of a brief intervention using mental simulations in reducing alcohol consumption in corporate employees. Psychol Health Med. (2011) 16:375–92. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.554568

69. Mattke S, Schnyer C, Van Busum KR. A review of the us workplace wellness market. Rand Health Quart. (2013) 2:4.

70. Mulder L, Belay B, Mukhtar Q, Lang JE, Harris D, Onufrak S. Prevalence of workplace health practices and policies in hospitals: results from the workplace health in america study. Am J Health Promot. (2020) 34:867–75. doi: 10.1177/0890117120905232

71. Mattke S, Liu H, Caloyeras J, Huang CY, Van Busum KR, Khodyakov D, et al. Workplace wellness programs study. Rand Health Quart. (2013) 3:254. doi: 10.7249/RR254

72. Peñalvo JL, Sagastume D, Mertens E, Uzhova I, Smith J, Wu JH, et al. Effectiveness of workplace wellness programmes for dietary habits, overweight, and cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. (2021) 6:e648–e60. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00140-7

73. McCambridge J. Reimagining brief interventions for alcohol: towards a paradigm fit for the twenty first century? Addict Sci Clin Pract. (2021) 16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00250-w

74. Kruse CS, Lee K, Watson JB, Lobo LG, Stoppelmoor AG, Oyibo SE. Measures of effectiveness, efficiency, and quality of telemedicine in the management of alcohol abuse, addiction, and rehabilitation: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e13252. doi: 10.2196/13252

75. Joseph B, Walker A, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. Evaluating the effectiveness of employee assistance programmes: a systematic review. Eu J Work OrgPsychol. (2018) 27:1–15. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2017.1374245

76. Pidd K, Roche AM. How Effective Is Drug Testing as a Workplace Safety Strategy? A Systematic Review of the Evidence Accident Analysis & Prevention. (2014) 71:154–65. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2014.05.012

77. McCambridge J, Kypri K. Can simply answering research questions change behaviour? Systematic review and meta analyses of brief alcohol intervention trials. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e23748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023748

78. Bernstein SL, D'Onofrio G. Screening, treatment initiation, and referral for substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. (2017) 12:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13722-017-0083-z

79. McPherson TL, Goplerud E, Olufokunbi-Sam D, Jacobus-Kantor L, Lusby-Treber KA, Walsh T. Workplace alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (Sbirt): a survey of employer and vendor practices. J Workplace Behav Health. (2009) 24:285–306. doi: 10.1080/15555240903188372

80. Babor TF, Kadden RM. Screening and interventions for alcohol and drug problems in medical settings: what works? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. (2005) 59:S80–S7. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174664.88603.21

81. Zolkefli Y. Disclosure of mental health status to employers in a healthcare context. Mal J Med Sci MJMS. (2021) 28:157. doi: 10.21315/mjms2021.28.2.14

82. Kunyk D. Substance Use Disorders among registered nurses: prevalence, risks and perceptions in a disciplinary jurisdiction. J Nurs Manag. (2015) 23:54–64. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12081

83. Chapman J, Roche AM, Duraisingam V, Phillips B, Finnane J, Pidd K. Working at heights: patterns and predictors of illicit drug use in construction workers. Drugs Educat Prevent aPolicy. (2021) 28:67–75. doi: 10.1080/09687637.2020.1743645

84. Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff. (2010) 29:304–11. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

Keywords: substance use, alcohol use, drug use, workplace, systematic review

Citation: Morse AK, Askovic M, Sercombe J, Dean K, Fisher A, Marel C, Chatterton M-L, Kay-Lambkin F, Barrett E, Sunderland M, Harvey L, Peach N, Teesson M and Mills KL (2022) A systematic review of the efficacy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of workplace-based interventions for the prevention and treatment of problematic substance use. Front. Public Health 10:1051119. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1051119

Received: 22 September 2022; Accepted: 18 October 2022;

Published: 07 November 2022.

Edited by:

Lode Godderis, KU Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Ezequiel Pinto, University of Algarve, PortugalPerpetua Modjadji, South African Medical Research Council, South Africa

Copyright © 2022 Morse, Askovic, Sercombe, Dean, Fisher, Marel, Chatterton, Kay-Lambkin, Barrett, Sunderland, Harvey, Peach, Teesson and Mills. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katherine L. Mills, a2F0aGVyaW5lLm1pbGxzQHN5ZG5leS5lZHUuYXU=

Ashleigh K. Morse1

Ashleigh K. Morse1 Frances Kay-Lambkin

Frances Kay-Lambkin Maree Teesson

Maree Teesson Katherine L. Mills

Katherine L. Mills