94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Public Health, 28 November 2022

Sec. Children and Health

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1050621

This article is part of the Research TopicSafeguarding Youth from Agricultural Injury and Illness: International ExperiencesView all 29 articles

It has long been established that children on farms are especially vulnerable to major injury. This is true in much of the world (1, 2), including our own country of Canada (3, 4). It is also true of children who grow up as members of farm families who reside on farm and ranch (i.e., large farm) properties (5), as well as children who frequent farms as occasional workers (6) or as visitors to the farm and its related worksites (7). In Canada, there is potential for children to be exposed to a diversity of mechanical, structural, chemical and other physical hazards associated with agricultural production activities (8, 9). Such hazards present risks for major trauma, injury, and disability (1–9). Patterns of injury evolve as children grow, develop and begin to take on essential work roles as part of the farm operation.

In this commentary we reflect on the current state of knowledge about the injury problem on Canadian farms. Our hope is to briefly summarize the current state of epidemiological evidence surrounding the child farm injury problem in Canada using evidence from our ongoing, national surveillance program (9). Building on this foundation, we will present evidence and opinion derived from international research about what works to prevent farm injuries among different groups of children. We will highlight the existence of policies and programs that are available within the Canadian agricultural sector and summarize barriers to the implementation of known effective strategies from the perspectives of health and safety professionals (e.g., Agricultural Safety Program Coordinators, Health and Safety Advisors, Farm Safety Consultants and Educators). who work with the farming community on an ongoing basis.

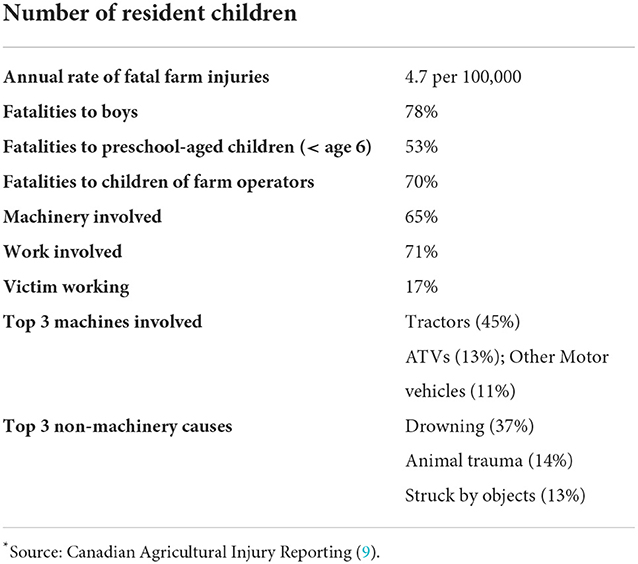

While agriculture is evolving in Canada with more corporate farms emerging in recent years, most farms continue to operate as family farms (“sole propriertorships” and “partnerships”) with a heavy emphasis on the raising of grain and large animal products (10). In terms of injury, nationally representative data on the most serious types of farm injury are available from the Canadian Agricultural Injury Reporting program (11), our national system for the surveillance of injuries related to agriculture. Available data include reports from 1990 to present on fatalities related to agricultural work and settings, including those involving children (Table 1). Trends and patterns within these fatality records are informative. Overall, while annual counts and number of children at risk have declined as the agricultural sector has changed, on a per capita basis the risks to farm children have remained fairly constant over the past three decades (11). The majority of child fatalities are experienced by boys who are residents of farms. Most involve machinery, primarily tractors due to runovers and rollovers, with emergent risks associated with ATV operation (11). Preschool-aged children (11, 12) and young workers (6) are particularly vulnerable, especially when assigned to situations and tasks that they are developmentally incapable of handling (13–15), and with inadequate adult supervision (16). This situation has persisted for generations on Canadian farms, and while much has changed due to advances in work and technology (8), much remains the same.

Table 1. Fatal farm injuries to children 0 to 14 years in Canada from 1990 to 2022 (n = 318 fatalities)*.

Tradition, culture and economic demands within farm populations are important factors in understanding why children continue to be exposed to farm hazards and associated risks for injury. Farming in North America in many ways is a unique occupation. Farm operators balance the need to keep themselves, their families and their workers safe from occupational hazards while simultaneously trying to pass on important values within their families, and while trying to maximize productivity and associated financial returns in the face of economic uncertainty (17–19). Consequences of this situation are well understood. Positively, children are intentionally exposed to situations that put them at risk to promote the values of hard work and autonomy, to advance their growth and development, and to foster strong ties between generations of families (18). All of these are good. More negatively, these values and practices can also lead to an acceptance of risk for children and young workers that is problematic, because it leads to the fatalities described above (11, 12, 16). Solutions to the injury problem on North American farms are unlikely to be effective if imposed from government or industry without the direct involvement of farmers. Farmers have historically resisted occupational health and safety regulations as an affront to their autonomy (19–21). What is valued culturally by most of the Canadian farm community often is in conflict with best practices for prevention from the public health, clinical and health and safety communities. This is an important challenge for health and safety efforts.

In this commentary, we have drawn upon available systematic reviews (21, 22) to describe what is known about the effectiveness of various strategies to prevent injury on farms. There are few randomized trials or other sophisticated evaluations of different strategies to prevent child injury on farms available in the scientific literature. The most widely accepted strategies are educational in nature, and these tend to be effective in making people aware of hazards, but with limited demonstration that they ultimately change rates of major trauma. Engineered solutions are also common and effective, but not universally adopted due to very real considerations of cost and the challenge of regulating occupational worksites that are autonomous and geographically dispersed. Policy solutions (referred to as “regulations” or “enforcement” in the injury prevention literature) too are available via occupational health and safety legislation applying to child labor practices (16) and highly effective when enforced (16). Yet, such legislation sometimes does not apply to resident farm children, nor does it cover situations where children are brought in to the workplace when adults are working, a circumstance common to many child fatalities (11, 12, 16).

The prevention of traumatic injury on farms and ranches remains a major challenge. In the development of this commentary, front-line agricultural safety and health practitioners associated with the Canadian Agricultural Safety Association were consulted to seek their expertise on barriers to the implementation of safety strategies that are known to be effective in other industries. A summary follows.

Agricultural work contexts are thought to be unique. The motivations and passion behind these agricultural businesses are steeped in tradition (19, 20) and are often not motivated solely for financial gain—for the most part, people are farming and ranching because of the lifestyle and passion for the occupation. Many farms and ranches are also the location of family homes, meaning there is a mix of “workplaces” and “play places”.

“It's a deeper question than just covering regulations – it's a mind-set. Separating work from family on the farm becomes blurred when the workplace is also a living space and a playground.” Canadian Agricultural Safety and Health Practitioner (Anonymous), 2022.

Engineered solutions, including the maintaining of equipment and structures, and the creation and maintenance of safe play areas (23) are considered vital, but can be expensive. Education solutions, including teaching producers about age-appropriate work (24), and children and youth from a young age about health and safety (25) are similarly held in high regard. Policy solutions like daycare (20, 21), farm safety audits (8), regulatory enforcement of child labor practices (5), and (although not studied in detail) financial incentives to improve farm safety (26) may be most effective, but can be divisive. In practice, there is considerable support for self/farm family-driven solutions (e.g., self-directed safety audits; grassroots childcare initiatives). There is considerably less support for imposed solutions like regulatory enforcement.

“In general, the introduction of legislation is always overwhelming for farm businesses. Farms have a tremendous amount of regulatory and administrative burdens, which are identified as one of the primary stressors contributing to mental health challenges in agriculture.” Canadian Agricultural Safety and Health Practitioner (Anonymous), 2022.

Traumatic farm injuries to children remain an important public health problem in Canada. Producers, communities, and agriculture-based organizations in our country, including safety and health organizations, do embrace keeping children and youth safe. Farm families in Canada are acutely aware of hazards associated with farm life and make adjudicated decisions to balance the risks and benefits of intentional farm and farm work exposures (18). Moreover, there is agreement that it is important that the sustainability of family farms and ranches is supported, and this includes protecting farm families.

Solutions are complex and are ultimately influenced by tradition. Ultimately, the prevention of injuries to children on Canadian farms will necessarily involve a culture change, including a shift in the narrative on how children and youth live and play on farms and ranches, with the support of evidence-based education, engineering and policy solutions. This remains an ongoing challenge for all concerned.

WP prepared the initial draft of this manuscript. AL and RA surveyed agricultural safety professionals from across Canada in order to summarize their insights about the prevention of injuries to children on farms. KB, AL, RA, and DV reviewed and edited the manuscript for important intellectual content. DV and KB oversaw the analysis that underlies this commentary. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

We thank Colleen Drul (Injury Prevention Centre, Alberta) for her careful analysis of the CAIR data in support of this commentary.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. National Children's Center for Rural Agricultural Health Safety. Childhood agricultural injuries (U.S.) 2020 Fact Sheet. Available online at: https://marshfieldresearch.org/Media/Default/NFMC/PDFs/ChildAgInjuryFactsheet2020.pdf (accessed October 22, 2022).

2. Health Safety Executive. Fatal Injuries in Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing in Great Britain, 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022. Available online at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/agriculture/pdf/agriculture-fatal-injuries-2022.pdf (accessed October 22, 2022).

3. Pickett W, Hartling L, Brison RJ, Guernsey JR. Fatal work-related farm injuries in Canada, 1991-1995. Can Med Assoc J. (1999) 160:1843–8.

4. Pickett W, Hartling L, Dimich-Ward H, Guernsey JR, Hagel L, Voaklander DC, Brison RJ. Surveillance of hospitalized farm injuries in Canada. Injury Prevent. (2001) 7:123–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.2.123

5. Wright S, Marlenga B, Lee BC. Childhood agricultural injuries: an update for clinicians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2013) 43:20–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2012.08.002

6. Marlenga B, Berg RL, Linneman JG, Brison RJ, Pickett W. Changing the child labor laws for agriculture: impact on injury. Am J Public Health. (2007) 97:276–82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.078923

7. Pickett W, King N, Marlenga B, Lawson J, Hagel L, Dosman J. for the Saskatchewan Farm Injury Cohort Study Team. Exposure to agricultural hazards among children who visit farms. Paediatrics Child Health. (2018) 23:1–7. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxy015

8. Rautiainen RH, Grafft LJ, Kline AK, Madsen MD, Lange JL, Donham KJ. Certified safe farm: identifying and removing hazards on the farm. J Agric Saf Health. (2010) 16:75–86. doi: 10.13031/2013.29592

9. Canadian Agricultural Injury Reporting. Agriculture-related fatalities in Canada. Winnipeg: Canadian Agricultural Injury Reporting (CAIR). (2016).

10. Statistics Canada. Snapshot of Canadian Agriculture. Ottawa: Canada Census of Agriculture (2016). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/95-640-x/2011001/p1/p1-01-eng.htm (accessed October 22, 2022).

11. Voaklander DC, Rudolphi JM, Berg R, Drul C, Belton KL, Pickett W. Fatal farm injuries to Canadian children. Prevent Med. (2020) 139:106233. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106233

12. Brison RJ, Pickett W, Berg RL, Linneman J, Zentner J, Marlenga B. Fatal agricultural injuries in preschool children: risks, injury patterns and strategies for prevention. Can Med Assoc J. (2006) 174:1723–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050857

13. Chang JH, Fathallah FA, Pickett W, Miller BJ, Marlenga B. Limitations in fields of vision for simulated young farm tractor operators. Ergonomics. (2010) 53:758–66. doi: 10.1080/00140131003671983

14. Fathallah FA, Chang JH, Pickett W, Marlenga B. Ability of youth operators to reach farm tractor controls. Ergonomics. (2009) 52:685–94. doi: 10.1080/00140130802524641

15. Fathallah FA, Chang JH, Berg RL, Pickett W, Marlenga B. Forces required to operate controls on farm tractors: implications for young operators. Ergonomics. (2008) 51:1096–108. doi: 10.1080/00140130801961901

16. Morrongiello BA, Zdzieborski D, Stewart J. Supervision of children in agricultural settings: implications for injury risk and prevention. J Agromedicine. (2012) 17:149–62. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2012.655127

17. Sorensen JA, Tinc PJ, Weil R, Droullard D. Symbolic interactionism: a framework for understanding risk-taking behaviors in farm communities. J Agromedicine. (2017) 22:26–35. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2016.1248306

18. Elliot V, Cammer A, Pickett W, Marlenga B, Lawson J, Dosman J, et al. Saskatchewan Farm Injury Cohort Team. Towards a deeper understanding of parenting on farms: a qualitative study. PloS ONE. (2018) 13:e0198796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198796

19. Norman PA, Dosman JA, Voaklander DC, Koehncke N, Pickett W. Saskatchewan Farm Injury Cohort Study Team. Intergenerational transfer of occupational risks on family farms. J Rural Health. (2022) 38:527–36. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12602

20. Kelsey TW. The agrarian myth and policy responses to farm safety. Am J Public Health. (1994) 84:1171–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1171

21. DeRoo LA, Rautiainen RH. A systematic review of farm safety interventions. Am J Prevent Med. (2000) 18:51–62. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00141-0

22. Hartling L, Brison RJ, Crumley ET, Klassen TP, Pickett W, A. systematic review of interventions to prevent childhood farm injuries. Pediatrics. (2004) 114:e483–96. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1038-L

23. Esser N, Heiberger S, Lee B. Creating Safe Play Areas on Farms. Marshfield, WI: Marshfield Clinic. (2003).

24. Marlenga B, Lee BC, Pickett W. Guidelines for children's work in agriculture: implications for the future. J Agromedicine. (2012) 17:140–8. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2012.661305

25. McCallum DM, Conaway MB, Drury S, Braune J, Reynolds SJ. Safety-related knowledge and behavior changes in participants of farm safety day camps. J Agric Saf Health. (2005) 11:35–50. doi: 10.13031/2013.17895

Keywords: agriculture, Canada, child health, epidemiology, farming, injury, occupational health and safety, pediatrics

Citation: Pickett W, Belton KL, Lear A, Anderson R and Voaklander DC (2022) International commentary: Child injuries on the farm: A brief commentary from Canada. Front. Public Health 10:1050621. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1050621

Received: 22 September 2022; Accepted: 03 November 2022;

Published: 28 November 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Lundqvist, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenReviewed by:

John Gerard McNamara, Teagasc Food Research Centre, IrelandCopyright © 2022 Pickett, Belton, Lear, Anderson and Voaklander. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William Pickett, d3BpY2tldHRAYnJvY2t1LmNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.