94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 16 January 2023

Sec. Public Mental Health

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1048649

This article is part of the Research Topic Global Mental Health Among Marginalized Communities in Pandemic Emergencies View all 9 articles

Objective: The Rohingya endured intense trauma in Myanmar and continue to experience trauma related to displacement in Bangladesh. We aimed to evaluate the association of post-displacement stressors with mental health outcomes, adjusting for previously experienced trauma, in the Rohingya refugee population in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

Methods: We analyzed data from the Cox's Bazar Panel Survey, a cross sectional survey consisting of 5,020 household interviews and 9,386 individual interviews completed in 2019. Using logistic regression, we tested the association between post-displacement stressors such as current exposure to crime and conflict and two mental health outcomes: depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In adjusted analyses, we controlled for past trauma, employment status, receiving an income, food security, and access to healthcare and stratified by gender.

Results: The prevalence of depressive symptoms was 30.0% (n = 1,357) and PTSD 4.9% (n = 218). Most (87.1%, n = 3,938) reported experiencing at least one traumatic event. Multiple post-displacement stressors, such as current exposure to crime and conflict (for men: OR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.52–3.28, p < 0.001; for women: OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.44–2.56, p < 0.001), were associated with higher odds of depressive symptoms in multivariable models. Trauma (OR = 4.98, 95% CI = 2.20–11.31, p < 0.001) was associated with increased odds of PTSD. Living in a household that received income was associated with decreased odds of PTSD (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.55–1.00, p = 0.05).

Conclusion: Prevalence of depressive symptoms was high among Rohingya refugees living in Cox's Bazar. Adjusting for past trauma and other risk factors, exposure to post-displacement stressors was associated with increased odds of depressive symptoms. There is a need to address social determinants of health that continue to shape mental health post-displacement and increase mental healthcare access for displaced Rohingya.

As of May 2022, 101.1 million people in the world were forcibly displaced from their homes, accounting for more than 1% of the total global population (1). People flee for reasons such as war, systematic persecution, and climate change (2). Refugees often endure severe trauma before, during, and after their flight, putting them at high risk for mental health disorders (3–8). Recent meta-analyses estimate that the prevalence of mental health disorders among refugees ranges from 22.1 to 31.5% (9, 10). This is well above the global prevalences of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which are estimated at 4.4% (11) and 1.1% (12), respectively. To address this staggering mental health burden, it is critical to understand the respective contributions of past trauma related to displacement and ongoing trauma in post-displacement settings.

The Rohingya are a religious-ethnic minority group in Myanmar who have been continually displaced from their homes due to ongoing persecution by the Myanmar government. As such, they are at high risk for poor mental health outcomes related to trauma (3). For decades, Rohingya have been subjected to state-sanctioned violence such as destruction of homes and property, torture, rape and other sexual violence, murder, and massacre (3–5, 13–15). Moreover, the Myanmar government has systematically excluded the Rohingya from society by denying them their right to citizenship. This has resulted in a near total denial of their civil, political, cultural, social and economic rights (3, 16). A more detailed account of Rohingya persecution in Myanmar is further explored elsewhere in the literature (16).

Rohingya displacement was accelerated in 2017 when the Myanmar military, alongside civilian vigilante groups, committed genocide against the Rohingya with mortality estimates ranging from 6,700-9,400 Rohingya fatalities (13, 17, 18). Since, approximately 770,000 Rohingya have fled to refugee camps in Bangladesh (19). Because of this, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh is now home to the world's largest refugee camp, housing 925,380 Rohingya as of April 2022 (19). However, Bangladesh is neither party to the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees nor do they recognize the Rohingya as refugees via their own frameworks (16, 20). Therefore, Bangladesh does not recognize a legal obligation to protect or guarantee rights to Rohingya refugees.

The camps in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh are overcrowded, unsafe and under-resourced (3, 4, 7, 21–23). An increase in the daily stressors that refugees commonly encounter in camps, such as limited work and educational opportunities, inadequate humanitarian assistance, dangerous living conditions, and limited access to healthcare, has been associated with increased symptoms of mental disorder (3, 4, 21, 24). Moreover, the daily functioning required to manage these stressors becomes increasing difficult as mental health worsens (4, 5, 25). In 2018, the majority of Rohingya in Bangladesh reported experiencing financial insecurity (95%), food insecurity (79%), lack of educational opportunities (72%), lack of appropriate living accommodations (62%), and inadequate access to clean bathrooms and sanitation facilities (62%) (3). We hypothesize that daily stressors generated by the refugee camp environment increase the burden of mental disorder in this population. This means that the environment that refugees are welcomed into may have significant implications for their ability to heal from past traumatic experiences.

Rohingya refugees have experienced an exceptional burden of severe trauma due to the systematic oppression in Myanmar and continued denial of their rights in Bangladesh (3, 13, 16). However, there is a gap in knowledge regarding the effects of post-displacement stressors on mental health outcomes and how these stressors contribute to the continuum of trauma that a Rohingya refugee experiences (7, 26). We aimed to narrow this gap by examining how post-displacement stressors might mediate, moderate or independently contribute to the effects of previously experienced trauma on mental health outcomes in the Rohingya refugee and asylum seeking population in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

We carried out a secondary data analysis of the Cox's Bazar Panel Survey (27). The Cox's Bazar Panel Survey is a data set collected jointly by the Yale Macmillan Program on Refugees, Forced Displacement, and Humanitarian Responses, the Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence program, and the Poverty and Equity Global Practice of the World Bank. It is a cross-sectional survey of 5,020 households, comprising 25,421 individuals and 9,386 individual adult interviews from randomly selected household adults. The household surveys collected information about the household roster, food security, consumption, assistance, assets, household income, and the anthropometrics of one randomly selected child under the age of five. The individual surveys collected information about labor market outcomes, migration history, crime and conflict, and health. Data were collected in 2019 from households in refugee camps and the host community, including refugees and Bangladeshi nationals. We excluded respondents who reported being under the age of 15 or Bangladeshi.

We examined two primary outcomes: depressive symptoms and PTSD. Presence of depressive symptoms was assessed via the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (28), which was administered during individual adult interviews. The PHQ-9 is a nine question survey asking participants how often they have experienced common symptoms of depression over the last 2 weeks using a 4-point scale where 0 = “not at all,” 1 = “several days,” 2 = “more than half the days,” and 3 = “nearly every day.” Answers are summed for a cumulative score. A score of 10 or higher indicates that significant depressive symptoms are present and that the respondent is at clinical risk for depression. Symptoms assessed include little interest or pleasure in doing things, feeling down, depressed, or hopeless, irregular sleeping habits, feeling fatigued, poor appetite or overeating, feeling like a failure or disappointment, trouble concentrating, irregular motor movements, and thoughts of self-harm and suicide.

PTSD was assessed using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) (29). The HTQ is a two-part survey tool that has been cross-culturally validated among numerous refugee populations (30, 31). However, it should be noted that the HTQ has not yet been validated among Rohingya refugees. The first part assesses exposure to traumatic events. The second part assesses clinical risk of PTSD via 16 questions. Participants are asked about symptoms consistent with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD and to what degree each symptom has bothered them. A 4-point scale is used where 1 = “not at all,” 2 = “a little,” 3 = “quite a bit,” and 4 = “extremely.” Answers are summed and divided by the number of symptoms they answered for a score. Scores of 2.5 or higher indicate significant clinical risk for PTSD. Symptoms assessed include recurrent thoughts or memories of the traumatic event(s), recurrent nightmares, feeling detached or withdrawn from people, unable to feel emotions, feeling irritable or having outbursts of anger, not wanting to interact with others outside the household, feeling as if you don't have a future, having difficulty dealing with new situations, troubled by physical problems, feeling unable to make daily plans, feeling that people do not understand what happened to you, feeling that others are hostile to you, feeling that you have no one to rely one, feeling no trust in others, feeling powerless to help others, and spending time wondering why these events happened to you. Notably, the list of symptoms assessed in this measure does not include all symptoms in the more recent DSM-5 criteria for PTSD.

Demographic variables included if the respondent lived in the host community or a refugee camp, their country of birth, sex, age, marital status, literacy, and religion. Marital status was recoded to distinguish between being not married because of divorce, separation, or having never been married or because of being widowed (32, 33). Variables on migration history included living in the same shelter now as in July 2017, where they were living if they answered no, if they expected to return to where they were living in July 2017, and how long they expect to live where they are currently.

Exposure to traumatic events was assessed via part one of the HTQ. Respondents indicated if they had experienced, witnessed, heard about it, or never experienced 12 different categories of traumatic event. Traumatic events included imprisonment, serious injury, combat situation, rape or sexual abuse, forced isolation from others, being close to death, forced separation from family members, murder of family or friends, unnatural death of family or friends, murder of stranger or strangers, being lost or kidnapped, and torture.

Post-displacement stressors included current exposure to crime and conflict, food security, employment status, receiving income from wages in the past year, monthly household income, perceived minimum monthly income needed to meet household needs, and healthcare access as measured by transit time to healthcare and healthcare costs in takas. Participant's current exposure to crime and conflict was assessed by asking if a series of different issues (bribery/corruption, harassment, theft, forced eviction, physical violence/assault, gender based violence, business disputes, family disputes, and indebtedness) were a problem in their neighborhood and if they had experienced any of them. Food security was assessed via an adapted version of the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (34), a nine question scale used to determine one's experience with food insecurity based on feelings of anxiety over food access, perceptions that available food is of insufficient quantity or quality, reductions of food intake, and the consequences of those reductions. The resulting score was then coded into a binary variable that scored each respondent as either food secure or insecure.

We calculated frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and measures of center (mean and median) and spread (standard deviation and interquartile range) for continuous variables. We conducted bivariate tests of unadjusted associations between the covariates and depressive symptoms and PTSD, respectively, using a significance level of α = 0.05. Categorical variables were assessed via chi-square tests and continuous variables were assessed using t-tests.

Multivariable models for depressive symptoms and PTSD, respectively, were constructed using directed acyclic graphs followed by a forward-selection stepwise approach to logistic regression modeling. Starting with the variables for depressive symptoms and experiencing at least one traumatic event, covariates were added to the model one by one. All clinically significant variables (e.g., age, sex, marital status) were retained in the multivariable model regardless of statistical significance to control for potential confounding.

In both models, we tested for interaction between trauma and post-displacement stressor variables. Although not part of the initial directed acyclic graphs, bivariate analysis indicated the potential for interaction between gender, migration history, and widowhood, so these interactions were also evaluated. As appropriate, each model was stratified by gender to clarify results. All statistical analyses were completed using Stata/SE 17 Statistical Software (35).

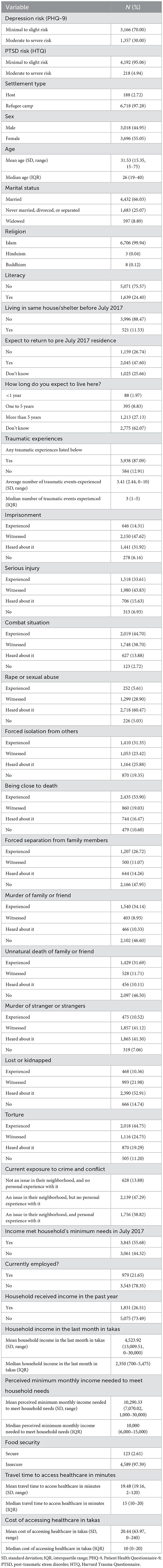

Six thousand nine hundred six Rohingya individuals over the age of 15 participated in interviews (Table 1). Of these, 4,523 answered the PHQ-9, 30.0% (n = 1,357) of whom scored a 10 or higher on the PHQ-9, indicating a moderate to severe risk of depression. Four thousand four hundred ten respondents answered the HTQ, 4.9% (n = 218) of whom reported symptoms consistent with a PTSD diagnosis. Most (97.3%, n = 6,718) respondents reported living in a refugee camp while 2.7% (n = 188) reported living in the host community. The mean and median age of respondents was 31.53 and 26, respectively, indicating a right skewed distribution. 45.0% (n = 3,018) identified as male and 55.1% (n = 3,695) identified as female. 66.0% (n = 4,432) of respondents were married, 25.1% (n = 1,683) were either separated, divorced, or have never been married, and 8.9% (n = 597) have been widowed. Nearly all respondents described themselves as Muslim (99.9%, n = 6,706). Only 24.4% (n = 1,639) reported that they are able to read a letter, meaning the majority of respondents (75.6%, n = 5,071) were illiterate.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of 6,906 Rohingya refugees living in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh as it relates to trauma exposure, daily stressors, and mental health outcomes.

Most respondents were not yet living in Bangladesh in July 2017 (88.5%, n = 3,996). A minority (11.5%, n = 521) were already living in Bangladesh at the time of the 2017 genocide in Myanmar. 47.6% (n = 2,045) of respondents expected to return to where they were living prior to displacement. However, only 2.0% (n = 88) expected to live where they are currently for less than a year. 8.8% (n = 395) expected to live in Bangladesh for 1–5 years, and 27.1% (n = 1,213) expected to live in Bangladesh for 5 years or more. The majority of participants (62.1%, n = 2,775) did not know how long they expected to be displaced.

Most (87.1%, n = 3,938) respondents had experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetime. The median number of experienced traumatic events was three. The three most reported traumatic events were exposure to death (53.9%, n = 2,435), torture (44.8%, n = 2,018), and combat situations (44.7%, n = 2,019).

38.8% (n = 1,756) reported that crime and conflict was an issue in their neighborhood and that they had personally experienced it. 47.9% (n = 2,139) reported that crime was an issue in their neighborhood but they have not personally experienced it, while only 13.9% (n = 628) reported that there was no issue with crime and conflict in their neighborhood.

55.7% (n = 3,845) reported that their income prior to the 2017 genocide met their household's basic needs. When this survey was done in 2019, respondents reported receiving average and median household incomes (4,523.92 takas and 2,350 takas, respectively) that were much lower than what they reported as their average and median perceived household income needs (10,290.33 takas and 10,000 takas, respectively). 21.7% (n = 979) reported being currently employed and 26.5% (n = 1,831) reported receiving income from wages in the past year. The majority (97.4%, n = 4,589) of participants indicated food insecurity. Respondents reported an average transit time of 19.5 min to access healthcare services and a median time of 15 min. The average cost of healthcare reported was 20.44 takas and the median was 10 takas.

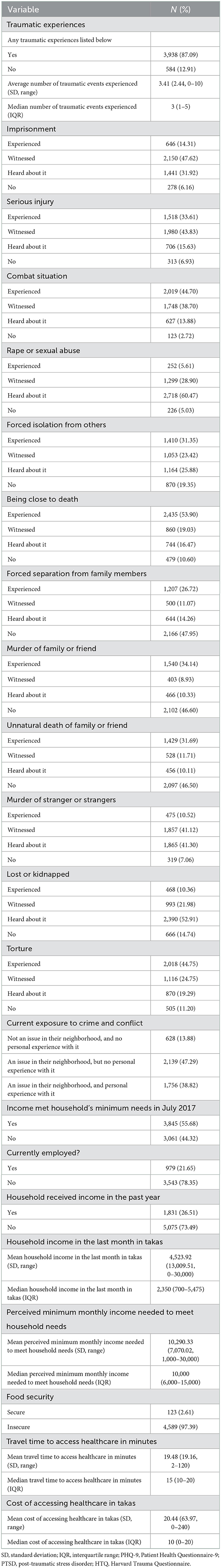

Depressive symptoms (Table 2A) are associated with PTSD (odds ratio (OR) = 24.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 15.80–38.55, p < 0.001), highlighting their comorbidity in this population. Age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.03–1.04, p < 0.001), being female (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.23–1.61, p < 0.001), being unmarried due to divorce, separation, or never being married (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.47–0.67, p < 0.001), being widowed (OR = 3.08, 95% CI = 2.50–3.79, p < 0.001), and literacy (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.55–0.76, p < 0.001) were associated with depressive symptoms. Living in the same shelter in July 2017 as they are now (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.09–1.60, p = 0.005), expecting to return to where they were living in July 2017 (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.17–1.63, p < 0.001), and expecting to live in their current shelter for 1–5 years (OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.34–0.89, p = 0.014) were all associated with depressive symptoms. Living in a refugee camp rather than the host community was not associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 2A. Bivariable associations with depression risk in 4,523 Rohingya refugees living in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

Experiencing at least one traumatic event (OR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.37–2.08, p < 0.001) was associated with depressive symptoms. Odds of depressive symptoms increased approximately 12% with each additional traumatic event experienced (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.09–1.14, p = 0.001). Imprisonment (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.12–2.13, p = 0.008), serious injury (OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.69–3.09, p < 0.001), a combat situation (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.26–3.18, p = 0.003), forced isolation from others (OR = 1.53, 95% CI = 1.27–1.85, p < 0.001), being close to death (OR = 2.5, 95% CI = 2.0–3.3, p < 0.001), forced separation from family members (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.26–1.71, p < 0.001), murder of a family or friend (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.53–2.03, p < 0.001), unnatural death of a family or friend (OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.54–2.06, p < 0.001), being lost or kidnapped (OR = 1.56, 95% CI = 1.21–2.01, p =0.001), and torture (OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.09–1.67, p = 0.007) were all associated with depressive symptoms. Witnessing the murder of strangers (OR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.52–2.68, p < 0.001) or rape or sexual abuse (OR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.56–3.05, p < 0.001) were also associated with depressive symptoms.

Experiencing crime and conflict in one's neighborhood (OR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.57–2.39, p < 0.001) nearly doubled odds of experiencing depressive symptoms. Perceiving crime and conflict as an issue without experiencing it personally (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.01–1.54, p = 0.037) increased odds of depressive symptoms by 25%. Other post-displacement stressors associated with depressive symptoms include being employed (OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.59–0.81, p < 0.001), receiving a household income in the past year (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.59–0.75, p < 0.001), monthly household income (OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.99–0.99, p = 0.004), and access to healthcare as measured by transit time in 10 min increments (OR = 1.12, 95% CI = 1.08–1.16, p < 0.001) and cost in takas (OR = 1.002, 95% CI = 1.001–1.002, p < 0.001). Lastly, odds of depressive symptoms decreased for those whose 2017 income met their monthly household's perceived needs (OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.68–0.88, p < 0.001). Food security was not associated with depressive symptoms.

PTSD (Table 2B) was associated with age (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.01–1.03, p < 0.001), being unmarried due to divorce, separation, or never being married (OR = 0.61, 95% CI = 0.40–0.94, p = 0.024), being widowed (OR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.59–3.29, p < 0.001), and literacy (OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.41–0.87, p = 0.007). Identifying as female was not associated with PTSD. Living in the same shelter in July 2017 as now (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.01–2.14, p = 0.047) was associated with increased odds of PTSD. Living in a refugee camp rather the host community was not associated with PTSD.

Table 2B. Bivariable associations with PTSD risk in 4,410 Rohingya refugees living in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

Experiencing at least one traumatic event (OR = 5.48, 95% CI = 2.42–12.40, p < 0.001) was associated with higher odds of PTSD symptoms. Odds of PTSD increased with each additional traumatic event experienced (OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.26–1.40, p < 0.001). Imprisonment (OR = 2.78, 95% CI = 1.07–7.21, p = 0.036), serious injury (OR = 6.39, 95% CI = 2.34–17.44, p < 0.001), forced isolation from others (OR = 5.17, 95% CI = 3.10–8.64, p < 0.001), being close to death (OR = 12.26, 95% CI = 3.90–38.56, p < 0.001), forced separation from family members (OR = 1.98, 95% CI = 1.43–2.75, p < 0.001), murder of family or friend (OR = 2.67, 95% CI = 1.97–3.60, p < 0.001), unnatural death of family or friend (OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.46–2.62, p < 0.001), being lost or kidnapped (OR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.03–2.60, p = 0.038), and torture (OR = 5.00, 95% CI = 2.44–10.25, p < 0.001) were all associated with PTSD. Experiencing a combat situation or the murder of strangers were not associated with PTSD. Witnessing rape or sexual abuse (OR = 3.79, 95% CI = 1.38–10.45, p = 0.010) was associated with PTSD.

Crime and conflict in one's neighborhood were not associated with PTSD. Living in a household that received income from wages in the past year (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.49–0.87, p = 0.003) was associated with reduced odds of PTSD, but there was no association between individual employment and PTSD. There was also no association between PTSD and monthly household income, having an income in July 2017 that met the household's needs, food security, or healthcare access.

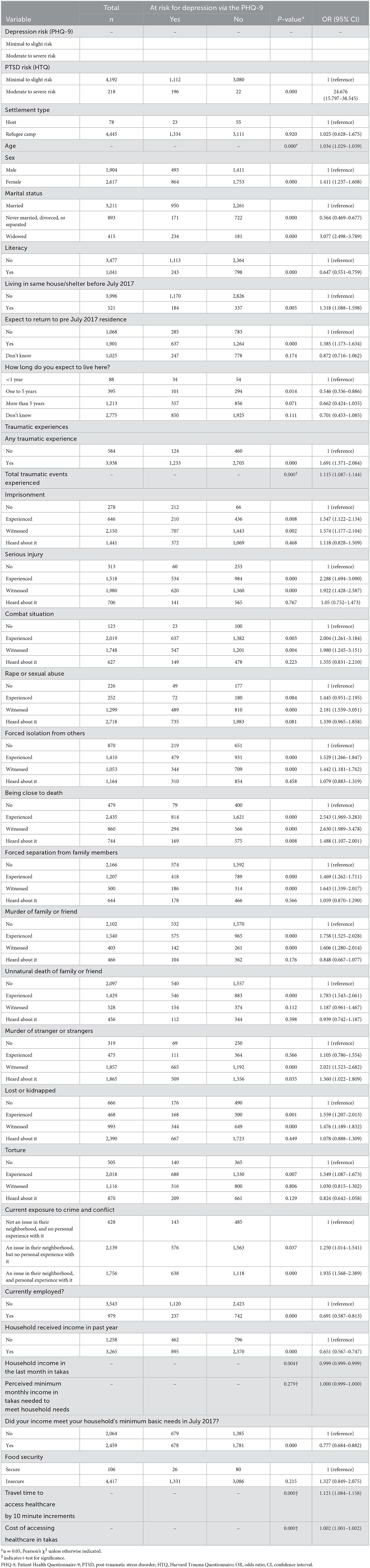

No interaction effects on depressive symptoms were identified between post-displacement stressors and trauma. However, interaction effects were identified between sex and marital status, as well as sex and tenure in Bangladesh. The multivariable model for depressive symptoms is stratified based on sex (Table 3). The unstratified multivariable model for depressive symptoms with interaction terms can be found in the Supplementary material.

Table 3. Multivariable logistic regression model for depression among Rohingya refugees living in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, stratified by gender (n = 4,314).

Among men, odds of depressive symptoms increased with age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.02–1.04, p < 0.001), being widowed (OR = 4.58, 95% CI = 1.82–11.50, p = 0.001), and transit time to healthcare (OR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.04–1.15, p = 0.001). Odds of depressive symptoms were lower among those who reported having an income that met their household's needs in July 2017 (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.62–0.97, p = 0.028), expecting to live in their current home for more than 5 years (OR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.23–0.84, p = 0.013), and being employed (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.60–0.96, p = 0.022). Experiencing at least one traumatic event was not associated with depressive symptoms in men. Adjusting for other factors, including past exposure to trauma, personally experiencing crime and conflict in their neighborhood was associated with more than twice the odds of depressive symptoms in men (OR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.52–3.28, p < 0.001).

Among women, odds of depressive symptoms increased with age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.02–1.03, p < 0.001), being widowed (OR = 1.60, 95% CI = 1.23–2.10, p = 0.001), living in the same shelter in July 2017 as they are now (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.15–1.95, p = 0.003), and transit time to healthcare (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.06–1.16, p < 0.001). Women who had experienced at least one traumatic event also had higher odds of depressive symptoms (OR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.29–2.24, p < 0.001). Odds of depressive symptoms were lower for those whose households received income from wages in the past year (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.64–0.94, p = 0.010). Adjusting for other factors, including past exposure to trauma, personally experiencing crime and conflict in their neighborhood was associated with nearly twice the odds of depressive symptoms in women (OR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.44–2.56, p < 0.001).

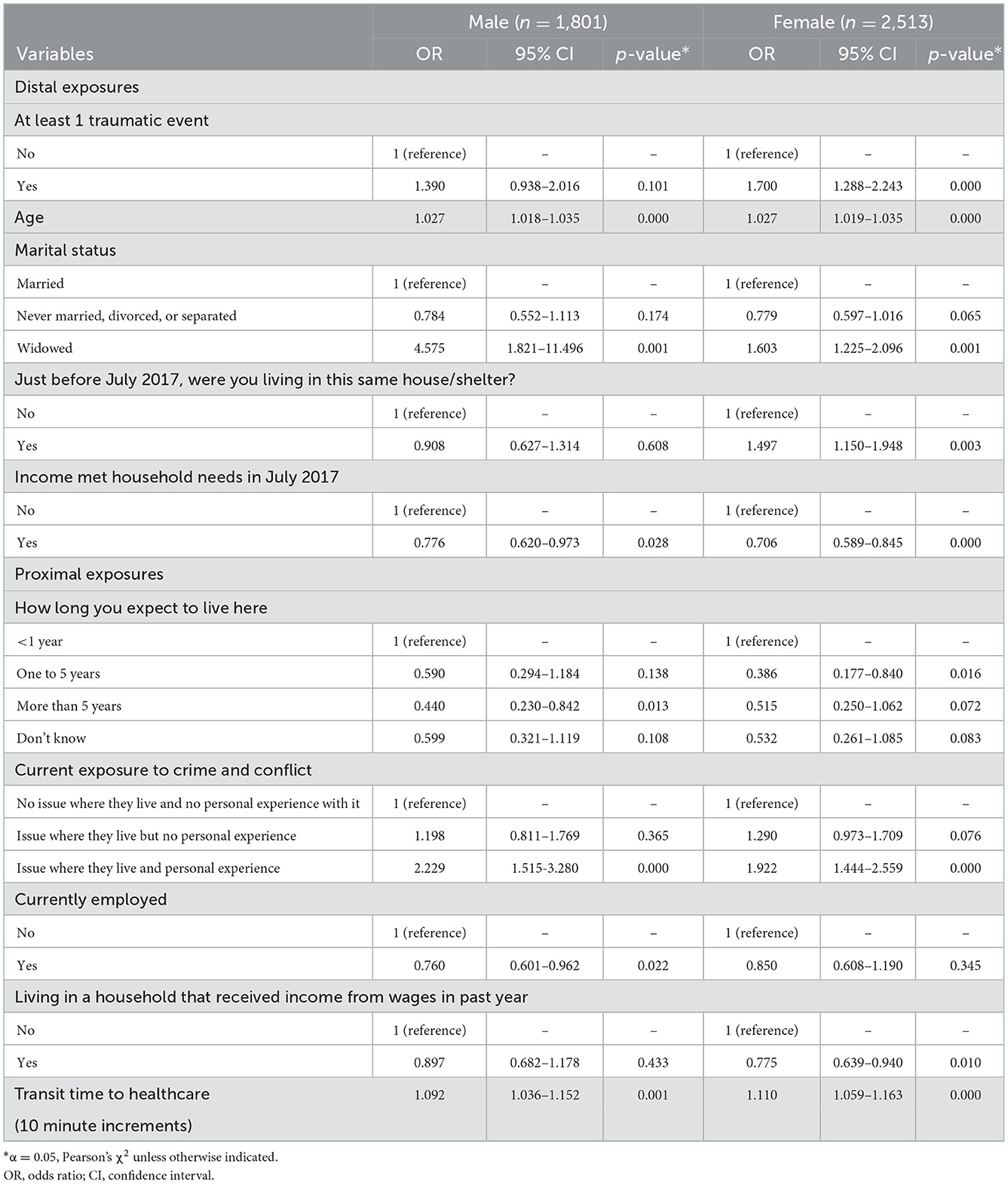

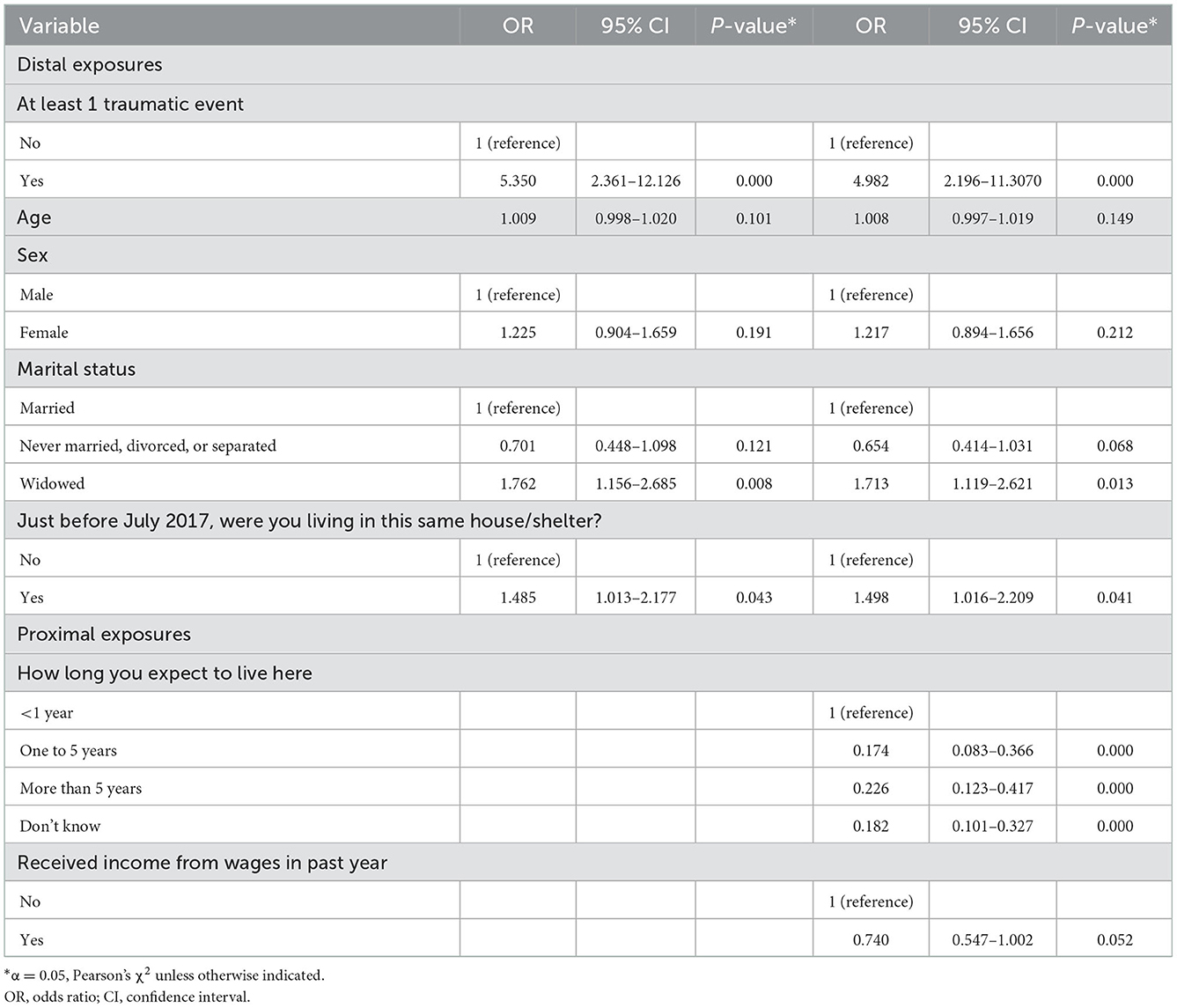

In a multivariable model, PTSD (Table 4) was associated with experiencing at least one traumatic event (OR = 4.98, 95% CI = 2.20–11.31, p < 0.001), being widowed (OR = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.12–2.62, p = 0.013), living in the same shelter in July 2017 as now (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 1.02–2.21, p = 0.041). Odds of PTSD were lower among those who expect to live in their current home more than one more year. Age and sex were not associated with PTSD. Receiving household income in the past year (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.55–1.00, p = 0.052) was associated with decreased odds of PTSD. No interaction was found between traumatic events and current exposure to crime and conflict.

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression model for PTSD among Rohingya refugees in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, stratified by gender (n = 4,349).

In this secondary analysis of data from 6,906 Rohingya in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, we found that nearly one in three adults experienced symptoms consistent with depression and nearly 5% experienced symptoms consistent with PTSD. We also found evidence that post-displacement stressors independently increased the odds of depressive symptoms among Rohingya. In particular, we found that exposure to crime and conflict in one's current neighborhood approximately doubled the odds of depressive symptoms, controlling for a wide range of other risk factors, including past trauma. This is particularly alarming as human rights organizations have reported recently that conditions for Rohingya in Bangladesh have grown increasingly violent since data were collected in 2019 (36–38). We did not find evidence that post-displacement stressors modify the effect of previously experienced trauma on mental health outcomes.

While global reported prevalence of depression is 4.4% and prevalence of PTSD is 1.1% (11, 12), 30.0 and 4.9% of respondents in this study reported symptoms consistent with depression and PTSD, respectively. Exposure to trauma is associated with depression and PTSD (39). Moreover, these estimates are consistent with the prevalence of depression in the global refugee community, estimated to range from 22.1 to 31.5% (9, 10). Indeed, our study's estimates are lower than previous studies of Rohingya displaced to Bangladesh, which range as high as 84% for depression (3) and 23.1–61% for PTSD (3, 21). This variation may be explained by differences in survey instruments, sample size, and sampling strategy. Riley et al. (3, 4) developed their own scale based upon the Hopkins Symptom Checklist in order to capture local idioms of distress. Doing so may have increased their instrument's sensitivity at the cost of its specificity. Further, previous studies were limited by smaller sample sizes (n = 148 and n = 495, respectively) (3, 4), which can reduce precision and bias estimates upwards (40). Regardless, it is clear that the burden of mental disorder among Rohingya is substantial. The need for mental health promotion and intervention among displaced Rohingya is urgent.

We also found that post-displacement stressors, such as current exposure to crime and conflict, reduced household access to income, and transit time to healthcare, significantly increase the odds of Rohingya refugees experiencing depressive symptoms. Other studies examining the impact of daily stressors on depression among Rohingya have identified stressors such as harassment by police and locals, food insecurity, income, discrimination, and sense of safety as significant predictors of negative mental health outcomes (3, 4, 40). In Bangladesh, the Rohingya have not been legally recognized as refugees by the Bangladeshi government since 1991 (20). They are not legally allowed to work, and do not have access to basic services and protections, thus exacerbating their risk for mental disorder (20, 23). These findings underscore the significant trauma that Rohingya continue to endure throughout displacement, and its poor mental health outcomes. Taken together, this work suggests that interventions to improve the post-displacement environment could significantly improve mental health outcomes.

The displacement experience affects mental health differently depending on gender. Living in Bangladesh in July 2017 – and therefore, not directly experiencing the 2017 genocide but spending more time in a Bangladeshi refugee camp - significantly increased women's odds of experiencing depressive symptoms. Men, on the other hand, did not have higher odds of depressive symptoms if they had lived in the camp since at least July 2017. Startlingly, this implies that, for women, protracted residence in Cox's Bazar may be worse for their mental health than surviving a genocide. Globally, refugee women are understood to experience worse mental health outcomes than men (9, 10), and Rohingya women are no exception (3, 4). Overcrowding, inadequate access to reproductive healthcare, and financial insecurity in refugee camps force women into exceedingly vulnerable positions (22, 41–43). Furthermore, displacement disrupts traditional gender norms, which can increase prevalence of gender based violence (GBV) (22, 42). Whether due to persecution in Myanmar or from dangerous conditions in Bangladesh, nearly every Rohingya woman has experienced sexual violence of some kind (15, 22, 44). Increasing access to reproductive healthcare and developing interventions that reduce GBV could improve the safety and mental health of Rohingya women.

Although harmful for both, widowhood increased odds of depressive symptoms among men more than among women. Other studies on the Rohingya have found little to no association between marital status and mental disorder (3, 4, 21, 24). However, to our knowledge, no studies specifically examine the mental health impacts of premature widowhood. For Rohingya women, marriage is a primary source of social and financial security (43), so it is surprising to see that widowhood is associated with worse outcomes among men. This could be explained, in part, by differential access to humanitarian aid. In Bangladesh, specific humanitarian programming is available for female widows, but not their male counterparts (45). However, this finding should be interpreted with caution given the small number of widowed men in our study. More research is needed on widowed refugee men as they may be an overlooked vulnerable population.

Post-displacement stressors were no longer significantly associated with PTSD in models controlling for age, sex, marital status, migration history, and past exposure to trauma. While some previous studies have identified relationships between PTSD and daily stressors (4, 21, 24), past exposure to trauma is the most important risk factor for PTSD meaning that individuals suffering from PTSD require clinical services (3–5, 21, 24, 39, 46). Although programs to address the social determinants of health are critically important, increased attention to them has come at the expense of clinical care in Bangladesh (15, 47, 48). Effective, accessible clinical care for PTSD is needed.

Notably, we found no effect of gender on likelihood of PTSD in adjusted analyses. This is not consistent with most findings on PTSD prevalence; women are up to three times as likely to suffer PTSD compared to men. There are at least two possible explanations for this surprising finding. First, the HTQ has not yet been validated among Rohingya refugee populations, so the measure of PTSD used in our analysis may be subject to bias. It is possible that the version of the HTQ used in this study is not sensitive Rohingya women's experiences of PTSD symptoms. Second, it is important to note that Rohingya in Bangladesh are not “post-trauma.” Indefinite confinement to a refugee camp without access to safety, education, and income may constitute an ongoing trauma that interferes with symptom presentation or recognition. There is great need for validation of the HTQ in a Rohingya population and for more research examining gender and trauma in long-term displacement.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the data are cross-sectional. While respondents were asked to reflect on past events, there is risk of recall bias and causality cannot be established. Second, eight refugee camp blocks refused participation in data collection. Refusal was attributed to distrust of outsiders and the humanitarian community. Therefore, this study did not include a subset of the Rohingya population in Cox's Bazar that may be particularly vulnerable. Third, although the most recent version of the HTQ has been updated to reflect the full range of PTSD symptoms described in the DSM-5 (49), this study relies on the original version of the questionnaire, which was based upon the DSM-IV. As the DSM-5 criteria include several additional symptoms, it is possible that our study underreports the true prevalence of PTSD in this population. Finally, neither the PHQ-9 nor the HTQ have been formally validated as measures of depression or PTSD among Rohingya, so caution should be taken when interpreting these results. Nonetheless, both the PHQ-9 and HTQ are some of the most commonly used tools for screening for depression and PTSD, respectively, and have been validated across a diverse range of settings.

This study also has strengths. A large sample size enabled well-powered, stratified analyses. Moreover, large sample size can contribute to more accurate prevalence estimates (40). We also used a directed acyclic graph of hypothesized associations to guide the development and interpretation of multivariable models, an approach to causal diagramming that can improve inference from cross-sectional data.

Rohingya displaced to Bangladesh experience a high burden of mental disorder attributable to stressors associated with living in a refugee camp. Adjusting for other factors, including past exposure to trauma, personally experiencing crime and conflict in their present neighborhood was associated with approximately twice the odds of depressive symptoms for both men and women in Cox's Bazar. The significant impact of the refugee camp environment on mental health outcomes points to a major missed opportunity for improving refugee health. While trauma directly associated with displacement increases risk of depressive symptoms among Rohingya refugees, the quality of a refugee's immediate neighborhood environment is a more substantial—and substantially more modifiable—risk factor for depressive symptoms. Increased access to mental healthcare and the provision of safe and dignified living conditions for all Rohingya could help reduce post-displacement stress and, therefore, mitigate this mental health crisis.

Finally, the Rohingya are an understudied refugee population that deserve further inquiry. This analysis demonstrates that large data collection efforts like the CBPS are a valuable resource for public health researchers and practitioners. However, refugee camps are dynamic settings. There is a critical need for repeated collection of key data on refugee wellbeing to inform humanitarian response and public health interventions.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

HR and MA-H conceptualized and designed the study. HR carried out statistical analyses in consultation with MA-H. HR drafted the initial manuscript. MA-H reviewed and revised. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors wish to acknowledge mentorship from Dr. Nina Parikh and Dr. Peter Navario. Some elements of this work were part of a thesis from the New York University School of Global Public Health.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1048649/full#supplementary-material

1. million people forcibly displaced. UNHCR Refugee Statistics. (2022). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/insights/explainers/100-million-forcibly-displaced.html (accessed August 6, 2022).

2. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR Global Trends - Forced displacement in 2020. UNHCR Flagship Reports. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globaltrends/ (accessed September 15, 2021).

3. Riley A, Akther Y, Noor M, Ali R, Welton-Mitchell C. Systematic human rights violations, traumatic events, daily stressors and mental health of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Confl Health. (2020) 14:60. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00306-9

4. Riley A, Varner A, Ventevogel P, Taimur Hasan MM, Welton-Mitchell C. Daily stressors, trauma exposure, and mental health among stateless Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Transcult Psychiatry. (2017) 54:304–31. doi: 10.1177/1363461517705571

5. Khan S, Haque S. Trauma, mental health, and everyday functioning among Rohingya refugee people living in short- and long-term resettlements. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:497–512. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01962-1

6. Tay AK, Riley A, Islam R, Welton-Mitchell C, Duchesne B, Waters V, et al. The culture, mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Rohingya refugees: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2019) 28:489–94. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000192

7. Li SSY, Liddell BJ, Nickerson A. The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2016) 18:82. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0

8. Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA. (2005) 294:602. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602

9. Blackmore R, Boyle JA, Fazel M, Ranasinha S, Gray KM, Fitzgerald G, et al. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. (2020) 17:e1003337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003337

10. Charlson F, Ommeren M, van Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2019) 394:240–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

11. World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization. Report No.: WHO/MSD/MER/2017.2. World Health Organization (2017).

12. Karam EG, Friedman MJ, Hill ED, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Petukhova M, et al. Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Depress Anxiety. (2014) 31:130–42. doi: 10.1002/da.22169

13. Parmar PK, Leigh J, Venters H, Nelson T. Violence and mortality in the Northern Rakhine State of Myanmar, 2017: results of a quantitative survey of surviving community leaders in Bangladesh. Lancet Planetary Health. (2019) 3:e144–53. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30037-3

14. Haar RJ, Wang K, Venters H, Salonen S, Patel R, Nelson T, et al. Documentation of human rights abuses among Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. Confl Health. (2019) 13:42. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0226-9

15. Physicians for Human Rights. Sexual Violence, Trauma, and Neglect: Observations of Health Care Providers Treating Rohingya Survivors in Refugee Camps in Bangladesh. (2020). Available online at: https://phr.org/our-work/resources/sexual-violence-trauma-and-neglect-observations-of-health-care-providers-treating-rohingya-survivors-in-refugee-camps-in-bangladesh/ (accessed November 19, 2021).

16. Mahmood SS, Wroe E, Fuller A, Leaning J. The Rohingya people of Myanmar: health, human rights, and identity. Lancet. (2017) 389:1841–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00646-2

17. Myanmar/Bangladesh: MSF surveys estimate that at least 6 700 Rohingya were killed during the attacks in Myanmar | MSF. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. (2017). Available online at: https://www.msf.org/myanmarbangladesh-msf-surveys-estimate-least-6700-rohingya-were-killed-during-attacks-myanmar (accessed October 2, 2021).

18. Médecins Sans Frontières. “No one was left” Death and Violence Against the Rohingya in Rakhine State, Myanmar. Médecins Sans Frontières. (2018).

19. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Situation Refugee Response in Bangladesh. UNHCR Operational Data Portal (ODP). (2022). Available online at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/myanmar_refugees (accessed April 10, 2022).

20. Cortinovis R, Rorro L. Country Note Bangladesh: International Protection Issues and Recommendations from International and Regional Human Rights Mechanisms and Bodies. ASILE: Global Asylum Governance and the European Union's Role. ASILE Project at the Centre for European Policy Studies. (2021).

21. Hossain A, Baten RBA, Sultana ZZ, Rahman T, Adnan MA, Hossain M, et al. Predisplacement abuse and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health symptoms after forced migration among Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e211801. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1801

22. Parmar PK, Jin RO, Walsh M, Scott J. Mortality in Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh: historical, social, and political context. SRHM. (2019) 27:39–49. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1610275

23. Milton AH, Rahman M, Hussain S, Jindal C, Choudhury S, Akter S, et al. Trapped in statelessness: Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2017) 14:942. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080942

24. Kaur K, Sulaiman AH, Yoon CK, Hashim AH, Kaur M, Hui KO, et al. Elucidating mental health disorders among Rohingya Refugees: a Malaysian perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6730. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186730

25. Tay AK, Rees S, Miah MAA, Khan S, Badrudduza M, Morgan K, et al. Functional impairment as a proxy measure indicating high rates of trauma exposure, post-migration living difficulties, common mental disorders, and poor health amongst Rohingya refugees in Malaysia. Transl Psychiatry. (2019) 9:213. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0537-z

26. Saadi A, Al-Rousan T, AlHeresh R. Refugee mental health-an urgent call for research and action. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e212543. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2543

27. Baird S, Davis CA, Genoni M, Lopez-Pena P, Mobarak AM, Palaniswamy N, et al. Cox's Bazar Panel Survey. Harvard Dataverse. (2021). Available online at: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/citation?persistentId= (accessed September 15, 2021).

28. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

29. Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S. The Harvard trauma questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese Refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1992) 180:111–6. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008

30. Rasmussen A, Verkuilen J, Ho E, Fan Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder among refugees: Measurement invariance of Harvard Trauma Questionnaire scores across global regions and response patterns. Psychol Assess. (2015) 27:1160–70. doi: 10.1037/pas0000115

31. Wind TR, van der Aa N, de la Rie S, Knipscheer J. The assessment of psychopathology among traumatized refugees: measurement invariance of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 across five linguistic groups. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2017) 8:1321357. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1321357

32. Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chong SA, Shafie S, Sambasivam R, Zhang YJ, et al. The association of mental disorders with perceived social support, and the role of marital status: results from a national cross-sectional survey. Arch Public Health. (2020) 78:108. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00476-1

33. Hobfoll SE, Watson P, Bell CC, Bryant RA, Friedman MJ, Friedman M, et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid–term mass trauma intervention: empirical evidence. Psychiatry. (2007) 70:33. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283

34. Coates J, Swindale, A, Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide: Version 3: (576842013-001). American Psychological Association. (2007). Available online at: http://doi.apa.org/get-pe-doi.cfm?doi=10.1037/e576842013-001 (accessed April 10, 2022).

36. Fortifyrights. Bangladesh: Investigate Refugee-Beatings by Police, Lift Restrictions on Movement. Fortify Rights. (2022). Available online at: https://www.fortifyrights.org/bgd-inv-2022-05-26/ (accessed November 26, 2022).

37. Human Rights Watch (Organization). “An island jail in the middle of the sea”: Bangladesh's relocation of Rohingya refugees to Bhasan Char. New York, N.Y.: Human Rights Watch. (2021). 75.

38. Bangladesh: New Restrictions on Rohingya Camps. Human Rights Watch. (2022). Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/04/bangladesh-new-restrictions-rohingya-camps (accessed November 26, 2022).

39. Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA, van Ommeren M. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2009) 302:537–49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1132

40. Hynie M. The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: a critical review. Can J Psychiatry. (2018) 63:297–303. doi: 10.1177/0706743717746666

41. UN Women Bangladesh. Gender brief on Rohingya refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Bangladesh. (2017). 4.

42. Wachter K, Horn R, Friis E, Falb K, Ward L, Apio C, et al. Drivers of intimate partner violence against women in three Refugee Camps. Violence Against Women. (2018) 24:286–306. doi: 10.1177/1077801216689163

43. Ripoll S, Iqbal I, Farzana KF, Masood A, Galache CS, Mirante E, et al. Social and cultural factors shaping health and nutrition, wellbeing and protection of the Rohingya within a Humanitarian Context. (2017). Available online at: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13328 (accessed April 29, 2022).

44. Islam MM, Khan MN, Rahman MM. Intimate partner abuse among Rohingya women and its relationship with their abilities to reject husbands' advances to unwanted sex. J Interpers Violence. (2021). doi: 10.1177/0886260521991299

45. Gaynor T. Rohingya Widows Worry about their Families' Futures. UNHCR. (2018). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2018/4/5ad494934/rohingya-widows-worry-families-futures.html (accessed April 22, 2022).

46. O'Connor K, Seager J. Displacement, violence, and mental health: evidence from Rohingya adolescents in cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5318. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105318

47. Silove D, Ventevogel P, Rees S. The contemporary refugee crisis: an overview of mental health challenges. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:130–9. doi: 10.1002/wps.20438

48. Jeffries R, Abdi H, Ali M, Bhuiyan ATMRH, Shazly ME, Harlass S, et al. The health response to the Rohingya refugee crisis post August 2017: Reflections from two years of health sector coordination in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0253013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253013

Keywords: global mental health, forced displacement, trauma, marginalized communities, refugee mental health, emergency

Citation: Ritsema H and Armstrong-Hough M (2023) Associations among past trauma, post-displacement stressors, and mental health outcomes in Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh: A secondary cross-sectional analysis. Front. Public Health 10:1048649. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1048649

Received: 19 September 2022; Accepted: 15 December 2022;

Published: 16 January 2023.

Edited by:

Nawaraj Upadhaya, HealthRight International, United StatesReviewed by:

Khadija Mitu, University of Chittagong, BangladeshCopyright © 2023 Ritsema and Armstrong-Hough. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haley Ritsema,  aGFsZXlyaXRzZW1hQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

aGFsZXlyaXRzZW1hQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.