95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 06 December 2022

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1046628

Introduction: This study examined how public health (PH) and occupational health (OH) sectors worked together and separately, in four different Canadian provinces to address COVID-19 as it affected at-risk workers. In-depth interviews were conducted with 18 OH and PH experts between June to December 2021. Responses about how PH and OH worked across disciplines to protect workers were analyzed.

Methods: We conducted a qualitative analysis to identify Strengths, Weakness, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) in multisectoral collaboration, and implications for prevention approaches.

Results: We found strengths in the new ways the PH and OH worked together in several instances; and identified weaknesses in the boundaries that constrain PH and OH sectors and relate to communication with the public. Threats to worker protections were revealed in policy gaps. Opportunities existed to enhance multisectoral PH and OH collaboration and the response to the risk of COVID-19 and potentially other infectious diseases to better protect the health of workers.

Discussion: Multisectoral collaboration and mutual learning may offer ways to overcome challenges that threaten and constrain cooperation between PH and OH. A more synchronized approach to addressing workers' occupational determinants of health could better protect workers and the public from infectious diseases.

The SARS-CoV2 (hereafter, COVID-19) pandemic led to jurisdictions rapidly developing approaches to control disease spread. Despite advanced planning for the management of infectious disease and health emergencies stemming from previous public health (PH) risk events, such as SARS-CoV-1 (1), gaps appeared in areas such as data access, surveillance and consistent risk communication (2). The Public Health Agency of Canada stated that new connections across disciplines—which we refer to as multisectoral collaboration—had been made during the pandemic and recommended that these should be retained (2), though specific ways in which multisectoral collaboration might occur, and the challenges faced, remain undocumented.

Multisectoral collaboration has been considered in other PH-related studies (3) although, to our awareness, this has not been explored with consideration of occupational health (OH), PH and COVID-19. By PH, we refer to federal and provincial government agencies that focus, at the population level, on preventing disease and injuries, responding to public health threats, and promoting good physical and mental health. By OH, we refer to activities usually carried out by provincial Ministries of Labor that are focused on workplace safety and prevention of workplace accidents and illness. The involvement of various levels of government and a range of expertise that includes transdisciplinary knowledge is recognized as important for overcoming challenges in implementing and sustaining successful partnerships (4). Previous literature about multisectoral collaboration has noted complex PH issues have benefitted or been hindered by factors such as culture, structure, and leadership (5). Key strategies for success have included clear shared goals and roles, accountability measurements, and involvement of all sectors from the planning stage (5). Healthy school programs across Canada demonstrated the potential for longstanding and widescale impact through cross-sector engagement between PH and education systems (6). A 2022 systematic review examining governance during public health emergencies found it is important to document how policy actors communicate and coordinate to learn effective strategies for policy implementation (7).

Overlapping PH and OH issues related to COVID-19 were evident in workplaces, yet PH and OH responses were often siloed. The health risk from COVID-19 affected many industries, although low-wage workers, who were often public-facing, were disproportionately at risk (8). An Ontario study estimated that 12% of COVID-19 cases from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021 were linked to workplace outbreaks (9); however, these were only a portion of the cases that occurred in workplaces (others were attributed to community transmission and many were not reported at all). Embedded in occupation-based risk were class and racial disparities. For instance, in Toronto and Vancouver, the highest measure of inequality for COVID-19 positivity was among workers assessed as least able to work from home (often recent immigrants), while in Montreal the greatest inequality was among people who were visible minorities (10).

In this paper, we consider PH and OH COVID-19 measures reported by experts knowledgeable about their provincial settings. This study was important to explore how OH and PH experts perceived multisectoral work during the pandemic, and their suggestions about what worked well and what could be improved. Our study examined the following question: what can be learned from how these two sectors work together and separately to address occupational determinants of health affecting workers during the COVID-19 pandemic? Specifically, we investigated how PH and OH worked in relation to each other during the pandemic in Canada's four most populated jurisdictions: Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec.

This qualitative study is based in situational analysis and particularly, situational mapping whereby aspects of the situation and the relations between these aspects (e.g., policy or organizations) are analyzed (11). Our analysis drew on key informant (KI) expertise and utilized a policy-topics framework to identify Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) in multisectoral collaboration and prevention approaches. Strengths and weaknesses are conceived of as internal whereas opportunities and threats are considered largely external to the organization(s) at the center of analysis (12).

In-depth interviews were conducted with experts on how OH and PH sectors managed separately and collaboratively during the pandemic. We interviewed 18 key KIs, who were leaders in their areas of areas of labor, OH, employment law, and PH across Canada's four most populous provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec. These provinces were selected because they provided useful contrasts between OH and PH systems due to different structures and policies. Quebec and British Columbia have work-related injury and illness prevention and workers' compensation within the same organization: Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail in Quebec, and WorkSafe BC in British Columbia. Prevention and compensation are under separate organizations in Ontario where there is the Workers Safety Insurance Board, and The Ministry of Labor, Training and Skills Development, and in Alberta where there is the Workers Compensation Board of Alberta and the Occupational Health and Safety government branch.

Internet searches and government and industry organizational charts, publications and reports, news media and LinkedIn were used to identify key practitioners and policy experts with close knowledge of OH and PH policy, including relating to at risk workers. Using a purposive sampling strategy as we aimed for representation from PH, OH, and employment policy experts across the four jurisdictions. We recruited from the identified pool through cold calls, email, web forms and snowball/chain referral. We reached out to 117 contacts; some of these were professional and other organizations that, in turn, sent recruitment materials to an internal workforce or membership. Despite significant recruitment attempts, we did not secure PH expert interviews in Alberta and British Columbia, nor a worker advocate in Quebec. KIs had 1 to 25 years' experience (average 10 years) in PH and OH or policy.

Our final sample included government employees, lawyers from independent firms and legal aid organizations, union representatives, employees of non-profit organizations specializing in policy research and recommendations, and of non-profit social and worker advocacy organizations (Table 1).

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews, lasting 45 min to 1 h were conducted by the lead author between June and December 2021. Most were via Microsoft Teams; some were by phone when the participant preferred. Questions covered how/if PH and OH worked together during the pandemic, the scope of PH and OH operations, and protections and gaps for the health of workers.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Detailed notes capturing contextual issues and new analytic insights were written immediately following each interview, and then discussed by team members. Interview transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and uploaded to NVivo (13).

A framework with a-priori topic areas (Table 2) related to our research question was developed.

Interviews, field notes and emerging topics for the framework were discussed at weekly team meetings as data familiarization. As patterns began to appear (e.g., “Siloed legislation”) additional topics were added to the framework (14). The framework was used to develop a codebook.

The coded data were used for in-depth descriptions of each policy and thematic area and were used to compare the findings from the four provinces. With comparative data, we conducted a SWOT analysis as our final interpretation and mapping step (14). Documentary data were also gathered as topics arose, concurrent with interviews and analysis, to deepen and contextualize KI information. These materials, including employment standards/code, workers' compensation acts, and law journal legal interpretations, provided additional insight into work and health policy.

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board at [University blinded for review].

Our findings are distilled into themes under the headings of our SWOT analysis. In terms of strengths, we found novel collaboration occurred between PH and OH. However, weaknesses in organizational elements (e.g., siloes) impacted how PH and OH government bodies functioned in the context of the pandemic. This resulted in sectoral boundaries that sometimes impeded potential for PH and OH to improve health conditions. Third, we found there were several opportunities for further collaboration. Finally, our results identified threats which could be barriers to working together to address issues, and potential for ongoing gaps in worker protection.

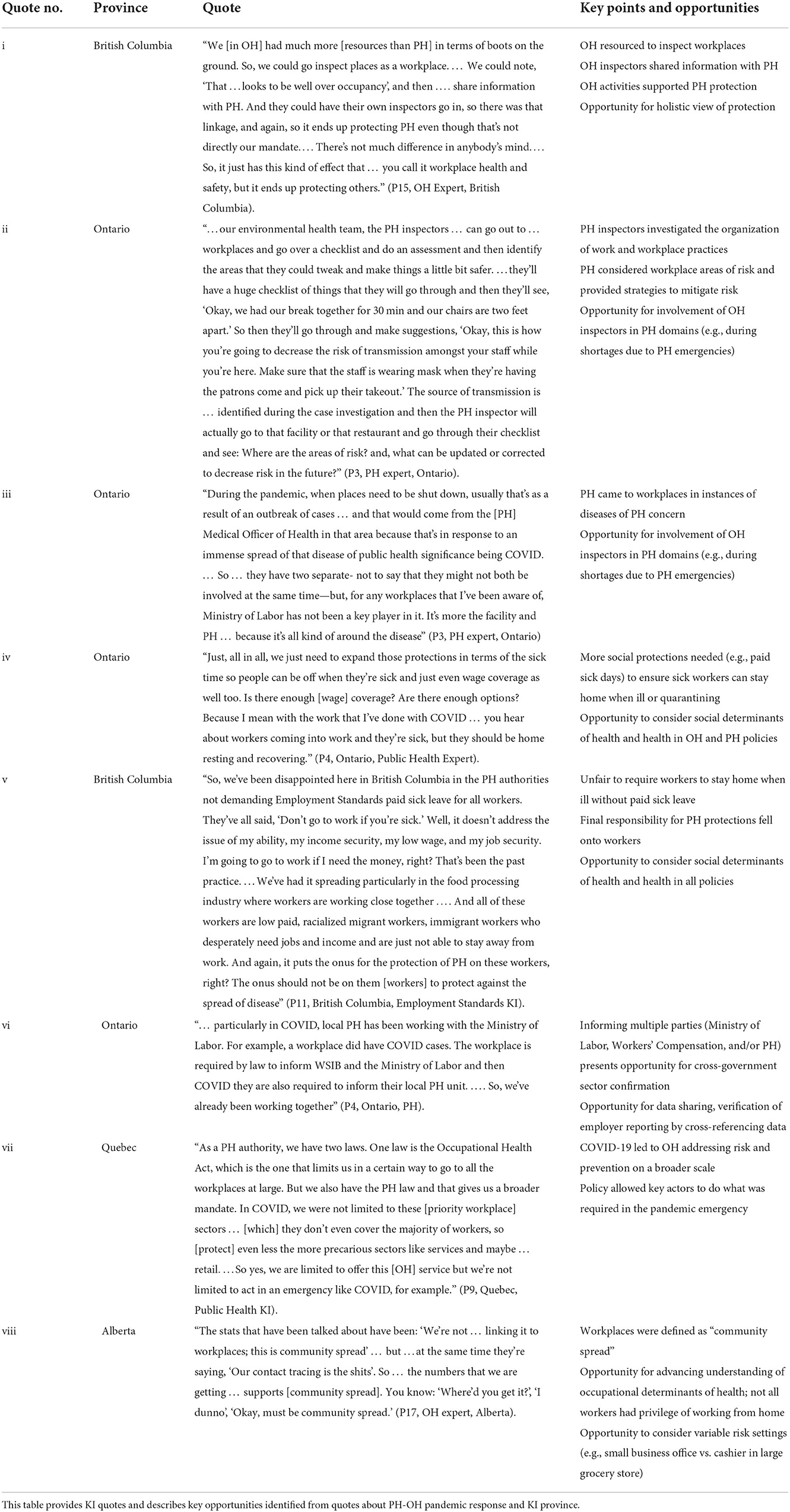

OH and PH sectors were described by KIs as having shared interest in health and safety risks and in prevention activity, which intersected within workplaces with infectious disease, such as COVID-19. For example, an Ontario PH KI described how their PH inspectors included work organization issues when investigating how people might have been exposed to COVID-19 (see Table 3, quote iii). In Ontario, KIs and documents both explained that PH became involved in workplaces in response to disease outbreaks, with COVID-19 outbreaks considered as two or more laboratory-confirmed cases where workers on the same shift or work area plausibly contracted the disease at work (15).

During the pandemic, KIs described how OH and PH collaborated to develop COVID-19 safety information (e.g., Table 3, quote ii). This primarily involved communication between the sectors, such as sharing information and developing materials; however, cooperation sometimes occurred on frontlines. For example, in British Columbia, a KI discussed how OH was involved in spreading information and ensuring compliance with safety plans for COVID-19 (Table 3, quote i.). British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec KIs spoke about how collaboration allowed for improved COVID-19 guidelines at the intervention development stage, as it fostered collaboration and communication between parties that typically did not interact (including different departments within an organization). In Quebec, a KI mentioned two groups that managed recommendations for the public and workplaces together developed consistent guidelines for masks. Similarly, a British Columbia KI said OH grew closer to PH during the pandemic while they worked together on safety plans (Table 3, quote i.). In Ontario, KIs spoke about how PH considered work environment factors in COVID-19 outbreak inspections. Also in Ontario, and while not mentioned directly by our KIs, it is worth mentioning that OH collaborated indirectly with PH by reimbursing employers for three paid COVID-related sick days; however, this reached only a portion of the working population because of the many (e.g., gig) workers classified as self-employed and presenteeism among low-wage workers due to fear of job loss. In Table 3, we highlight strengths in collaborations and intersections reported by KIs.

There were no Alberta examples of collaboration or cooperation between PH and OH from our data. This may be because we were unable to recruit PH participants from Alberta, who might have contributed examples. It may also reflect what our other Alberta participants described; that a preventive, protective PH/OH approach in Alberta had regressed, with low support for unions, and degraded protections through Occupational Health and Safety legislation change.

In this section we present KIs identification of organizational issues that created weaknesses in protecting workers and the public. These fell into two areas: communication, and the structure of separate prevention and workers' compensation policy. We draw on KI insights to illustrate how compensation is administered separately from worker protection in two provinces and we suggest that this may indicate prioritizing business at the expense of PH/OH and public/worker health and safety.

An initial challenge to communication was that PH messages to the public could independently come from different levels of government. Sub-provincial (regional or local) PH units allowed for population-targeted program delivery and interventions. In PH, regional authorities could issue varied edicts. For instance, one PH expert KI described how a specific sub-provincial PH unit might act differently than the province (Table 4, quote i.).

Table 4. Weaknesses: Key points identified from quotes about PH-OH pandemic response and KI province.

During the pandemic, the geographic boundaries of Ontario sub-provincial PH units defined where some measures were implemented. For instance, contact tracing operations were established at the local PH unit level. While local approaches are always needed for targeted PH interventions, in the context of COVID-19 they created neighboring areas with different regulations in place. Consistent messaging was important in this context: for example, an OH expert KI in Ontario said the Ministry of Labor received many questions from workers and always instructed people to refer to their local public health unit to see what was currently applicable in their area (Table 3, quote ii). They also noted it could be challenging for workers to obtain help or guidance from federal or provincial offices on related matters—for instance, regarding lost wages due to quarantine, or concerns about COVID as a workplace hazard.

From an OH perspective, one KI suggested that, because Alberta Workers' Compensation and OH prevention programs are run as separate organizational units, and because of employers' under-reporting of work accidents (to avoid workers' compensation claim costs), there was a disconnect between prevention in the workplace and illness management (Table 4, quote v.). This administrative division of the prevention and compensation OH components might have contributed to what some OH experts considered a relative lack of collaboration between OH and PH in Alberta, and to some extent in Ontario. For example, an Alberta KI described siloed legislation and workers not knowing where to obtain help. In British Columbia and Quebec, however, where KIs described OH and PH as more collaborative, both the prevention and workers' compensation arms of OH are operated under the same organizational umbrella.

In Ontario, KIs described that OH and PH shared physical space when PH entered workplaces; however, legislation and thus responsibility for health issues remain siloed between the OH and PH domains (Table 4, quote vii). The importance of clearly demarked responsibilities was realized during the pandemic. For example, one piece of guidance from the Ontario Ministry of Health clarified roles for: local PH units, the Ministry of Health, Ontario Health, Public Health Ontario, the Ministry of Labor, Training and Skills Development, and roles of employers (15). However, this document was created only in October 2021, almost 2 years after the declaration of the pandemic.

A potential gap for protecting workers' OH, as indicated by an OH expert in Ontario was that, while legislation included a broad description of employers having to take reasonable precautions to protect workers from COVID-19 exposure, the Ministry of Labor inspectors were limited to conducting inspections that focused on OH legislation and policy, which did not always overlap with PH considerations (Table 4, quote vii).

Sectoral division of responsibility became problematic when COVID-19 crossed typical boundaries. Circumstances when PH authorities enter a workplace were raised by KIs. Some described tension around when COVID-19 is considered an occupational illness vs. worker exposure through or to the public. KIs also spoke about workers being uncertain of who was responsible for paying wages for time lost to quarantine or illness and employers being unsure of which authority to report illnesses to. Opportunities to bridge traditional sectoral boundaries, including opportunities for PH/OH collaboration and the management of infectious diseases were further identified by the KIs.

Several KIs suggested there was opportunity to consider health protection more holistically. In part, this was because many workers do not have traditional workplaces that could be inspected (e.g., self-employed workers, including gig workers). Some KIs also saw an opportunity to more widely consider health protections as inclusive of population health and social determinants of health, rather the current segregated PH and OH domains. For instance, an OH expert in British Columbia spoke about the importance of protection regardless of who was doing what (Table 5, quote i).

Table 5. Opportunities: Key points identified from quotes about PH-OH pandemic response and KI province.

We found that some boundaries created an artificial distinction between workplaces and PH, given that workplaces were a site of transmission for COVID-19, and that PH issues (e.g., community spread) affected front-line and essential workers. Workplaces with a public-worker interface were particularly illustrative of how workplace and PH issues intersected. For example, a PH KI in Ontario explained that the presence of COVID-19 in the workplace determined when there would be PH involvement at workplaces (Table 4, quote ii.). In Alberta, some KIs described a historically weak OH sector as having had adverse system-level consequences during the pandemic. For instance, one KI described how weaknesses in COVID-19 data collection led to failures in identifying workplace spread (Table 5, quote viii). OH expertise was also described as directly relevant to COVID challenges with broad prevention approaches including the hierarchy of controls (e.g., engineering controls; Table 6, quote ii), evaluating occupancy levels (Table 6, quote i), and specific exposure control measures, such as ventilation (Table 6, quote ii).

When workplace outbreaks occurred, COVID-19 was generally considered by PH units as solely a PH issue. However, the situations reported by KIs indicate there may be an opportunity to bring OH authorities on board to assist with workplace issues. An additional reason for involving OH in workplace outbreaks during a pandemic is to alleviate the high demands on PH staff. Involving OH in some aspects of outbreaks in workplace investigations could draw on existing skills and free up PH to conduct other activities (e.g., vaccination clinics). Jointly addressing prevention and compensation presented a potential opportunity for cooperation as a workplace outbreak inspection could not only allow for preventive measures, but also provide opportunity for assessing the likelihood of the disease being considered an occupational-acquired disease. Extended cooperation presented further potential for support; for instance, by allowing OH to be involved in contact tracing for workers who test positive to COVID-19.

Cooperation among OH and PH occurred at a provincial level. Cooperation at a federal level was not apparent in our interviews. This may be because the federal government is largely seen as responsible for federal employees and federally regulated industries, while other industries fall under provincial OHS legislation. Another consideration is that most policy is at the provincial level, although we consider the federal Employment Insurance as an OHS protective policy.

In Alberta, new OH legislation took effect in 2021, which defined a legitimate “undue hazard” for workers who refuse to work due to safety concerns as something that poses a “serious and immediate health and safety threat,” such as sudden infrastructure collapse, broken equipment, or gas leaks (16). For respiratory viruses, if employers have taken “reasonable precautions,” such as barriers or space for physical distance, implemented sick leave policy, screening programs, or rules for wearing masks, the government explicitly stated, “If your employer has implemented reasonable controls to address the risk of respiratory viruses, it's unlikely that there will be an undue hazard under OH legislation” (16). In our view such situations may provide an opportunity for OH and PH to work together when a worker is concerned about the hazards of work and reasonable controls. As infectious disease experts, PH could be consulted by OH when there is doubt about the risk level, particularly as Alberta equated workplace transmission with community spread thereby dismissing elevated risk associated with workplace exposure. PH data (e.g., hazard ratios) in local areas could also be used as a baseline measure for undue hazard in the workplace. While this approach may present challenges in smaller and medium workplaces, drawing on information from large workplace may provide an opportunity to estimate workers' levels of risk, compared to community levels of risk.

In Ontario, differences occurred regarding what policy applied to a situation or what party was responsible. This especially created confusion in workplaces with a public interface, such as retail stores. For example, an Ontario OH KI (P2) noted that owner-operators who took deliveries or had customers pick up orders may not have developed workplace safety plans.

Workplace-based outbreaks sometimes drew in three authorities. For instance, in Ontario, the Ministry of Labor, workers' compensation, and local PH units each needed to be informed of disease outbreak situations. An opportunity in this case may be a shared-data system, which could serve as a cross-sectoral tool for OH and PH units as they could cross-reference data and follow up with employers who only reported to a single sector. A shared data system could also reduce the reporting burden on employers and support evaluation of OH and PH activities. Notably, as all occupational diseases are supposed to be reported to both the Ontario Ministry of Labor, Training and Skills Development and to workers' compensation, shared data systems might ensure that each organization received information reported to the other. Overall, a shared data system represents a major opportunity that would have benefits extending beyond COVID-19.

A few KIs spoke about the importance of ensuring sick workers were enabled to remain off work when unwell; however, some KIs noted that some worker populations could not afford to remain home and lose wages, and the employment and social security systems failed to fully compensate such workers for lost income. Ensuring workers were resourced (e.g., sick pay or lost wages benefits) to stay home when ill or isolating was a key strategy to slow the spread of COVID-19. Workers who continued to attend work while sick or in quarantine posed a threat to containing disease transmission. Paid days to quarantine during mandatory isolation were not always provided, especially for low-wage or other precarious workers (Table 5, quote v, Table 6, quote ii).

KIs noted various shortcomings in multisectoral collaboration sometimes resulted in less robust PH measures. Multiple KIs made reference to the idea that both OH and PH policies had not kept pace with the nature of work or science. For instance, one Alberta OH expert described how OH ventilation concerns did not receive the same sort of attention as other issues that fell within a more conventional PH evidence paradigm (e.g., Table 6).

Misalignment between OH and other authorities sometimes blunted the effect of OH mandates. For instance, when PH mandates required COVID-19-infected workers to stay home, employment standards legislation did not ensure that these workers could afford to take sick leave. Similarly, an employment standards KI described how OH legislation for workers' health protection existed but was not well enforced (Table 6, quote iii). Although the threats of a lack of enforcement were exposed by COVID-19, these concerns were well-noted prior to the pandemic. A 2019 report by the Auditor General of Ontario found the Ministry of Ontario, Labor and Skills Development found that 72% of businesses were uninspected. Of the 28% that were inspected, only one percent were proactive inspections (i.e. not in response to reported hazards) (17).

Even within government ministries, the application of policy to the COVID-19 situation created confusion and inconsistences, especially in relation to non-standard workplaces. For example, an Ontario OH expert described how the OH system missed large sections of the workforce that did not fit the setup of standard workplaces (Table 6, quote iv). Indeed, the lack of a physical workplace for some workers made it difficult for PH to disseminate prevention materials or for OH inspectors to conduct inspections. Non-static workplaces posed a further policy application challenge, as per the example a truck driver in Table 6, quote v).

Another interesting difference across provinces was how recognition of COVID-19 as an occupational illness differed. For instance, Alberta was the only province within our sample that did not consider COVID-19 as a presumed workplace-acquisition for some occupations, with the exception of healthcare workers. In Alberta, the workers' compensation board policy updated March 24, 2022 (18) was that every claim must be individually adjudicated whereas, in other provinces, blanket presumptions existed about workplace acquisition of COVID-19 for certain sectors, such as grocery or retail. Although not presumptive of workplace acquisition, Alberta's policy allowed case managers to “take into consideration” workplace acquisition on a case-by-case basis. Still, all jobs with greater risk were not taken into consideration, as the policy excluded, for example, grocery store clerks. For these workers, Alberta WCB stated that COVID-19 is not considered workplace acquired because: “You are in contact with many people but not specifically with infected shoppers. This is considered casual contact” (18). As one KI pointed out (Table 6, quote i) this position failed to acknowledge that workers who are in public-facing positions logically have greater exposure to the virus than those who do not interact with the public.

Taken together with other examples (e.g., Alberta's definitions of undue hazard under OH legislation and denial of work refusals), the Alberta compensation board's normalization of workers' having greater exposure risk via elevated contact with the public points to a larger issue. As some KIs indicated, there appeared to be a tendency in some jurisdictions to minimize state responsibility to the detriment of PH and OH protection for workers.

This aim of this paper was to examine how OH and PH coordinated with each other during the pandemic. We found that, while cooperation occurred between PH and OH to varying degrees, organizational factors such as sectoral policy and practice boundaries appeared to lead to siloed approaches and constituted a barrier to optimal communication and fulsome collaboration. Using SWOT analysis highlighted that the division between PH and OH did not allow for consideration of COVID-19 risks in all workplace situations. Such organizational and policy appeared to leave blind spots in worker protection. In this discussion, we consider how protection and gaps in the wake of government levels and sectoral divides might be addressed. We also examine opportunities to facilitate workers' health and safety from a broader, multisectoral lens.

The separate OH and PH architecture in Canada contributed to some weaknesses in the COVID-19 response. Our data suggested that there are several opportunities for mutually supportive interaction and collaboration among the two authorities. As far back as 2004, multisectoral communication was noted as important in Canada when health issues cross geographic boundaries:

“The issue of externalities and spillovers is closely linked to the primary reason why governments need to interact in public health. Threats to health produced in one region have the potential to spread and cause harm to individuals who live in other regions. For example, if one province chooses not to immunize its children against a certain condition, then the effectiveness of the immunization programs in other parts of Canada can be undermined” (p. 410) (19).

Our data support other findings that, despite OH legislation intended to protect Canadian workers, including via the right to refuse unsafe work and a right to information, there have been numerous failures in practice with respect to COVID-19 (20). Lippel (20) noted that, in Ontario, workers were required to work even when personal protective equipment was unavailable and health information was not forthcoming, and the Ontario Ministry of Labor appeared to systematically deny work refusals and that this “underreporting” of workers' compensation claims appeared to have been occurring for COVID-19. Our analysis adds that the division of PH and OH responsibilities did not fully consider the situated reality of workers in the context of infectious disease, such as COVID-19. Our findings suggest PH/OH segregation may have overlooked some workplace OH concerns as health issues for PH consideration. For example, recent investigative journalism found that Ontario's ‘essential' workers in manufacturing accounted for more workplace COVID deaths than any other sector, including health care (21).

An ethical issue emerges in consideration of public health orders requiring sick workers to stay home but not requiring income support compensation for those workers. This violates the principle of reciprocity, which calls for society to provide options to support individuals to “discharge their duty” when a public health measure burdens them (22). In the case of sick workers, wherein it is their public health duty to remain home when sick, the principle of reciprocity indicates that they should be financially compensated so they are able to afford to stay home and are not forced to go to work and expose others as a result of their own financial need.

The pandemic illustrated that PH and OH have complementary purposes that can be beneficial for protecting the health of populations during a pandemic. KIs described some instances where PH experts consulted with OH to devise recommendations for different workplace sectors; however, there is also room for this knowledge exchange to flow in the other direction: from OH to PH. OH expertise in airborne exposures is rich in tools and practices for measuring various substances and the appropriate protective measures (23, 24). For instance, OH experts did not support the notion of a strictly droplet spread of COVID-19, but rather, that particulate occurred in various sizes including airborne particles (25). Many OH experts recommended the use of fitted N95 masks as useful control measures early in COVID-19—masks that PH still did not recommended for most settings even two years into the pandemic (25).

Collaboration becomes especially important when staff surge capacity is required (26). PH-OH collaboration could also be a viable option. For instance, our data showed that the British Columbia labor ministry had inspectors already visiting workplaces (Table 3, quote i). Providing OH inspectors with training and protocols for managing implementation of safety plans and some limited and appropriate workplace-inspection components of PH investigations was a missed opportunity that might have freed up more PH workers. While some support for PH could be facilitated in this manner, identified PH concerns (e.g., outbreak scenarios) would still require PH investigation.

The separation of PH and OH organizationally and legislatively meant lost opportunities for responding to COVID (e.g., failure to draw on OH expertise around airborne controls/policies). Based on KI information both OH and PH policies and organization were not sufficient to protect non-standard workplaces and workers (e.g., mobile workers). While OH inspectors were physically present in workplaces, they could not help prevent disease transmission due to limits in legislative scope, and there was no evidence of communication to engage them in that role by PH, except in British Columbia. Despite barriers, PH and OH collaborations that did occur generated beneficial policies and actions (e.g., unified mask requirements for community and workplace settings in Quebec).

The physical presence of OH in workplaces offers PH an opportunity for enhanced preventive actions, particularly during emergency circumstances where OH may be able to provide PH surge capacity. Collaboration between OH and PH practitioners leads to beneficial policies and should be supported (e.g., via interpersonal networking, or formalizing multisectoral activities).

A strength of this study was the comparative examples from four Canadian provinces. This allowed for observation of a range of OH and PH activities during COVID-19 and triangulation of themes. A further strength of this study was the multi-sectoral knowledge of our KIs that allowed us to probe various aspects of PH/OH regarding the protection of workers. A limitation of this study was that our sample in each area of expertise for each province was small and we were unable to obtain PH participants from Alberta. Therefore, our findings should not be considered representative of every jurisdiction or generalizable. Nevertheless, our sampling strategy allowed for data generation that raises useful propositions. Further, as a qualitative study our study was able to access contextualized accounts of policy situations.

The COVID-19 pandemic response saw multisectoral OH-PH communication and collaboration become important for improved worker and PH measures and operational function. As OH and PH policies are updated across Canada, more cooperation among these authorities may overcome communication weaknesses. Our study suggests that there is opportunity in cooperation: OH and PH stakeholders found value in, and may support the continuation of, new productive relationships. Overall, there is also opportunity for more coordination of PH and OH measures; for instance, the precautionary principles from OH and the upstream preventive measures of PH each offer upstream opportunity to evaluate risk. We conclude that a collaborative multisectoral approach with mutual PH and OH supports could strengthen Canada's response to the risk of COVID-19 and potentially other health risks.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Waterloo Office of Research. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

EM, SEM, and SBM conceived of and designed the study. Interviews were conducted by PH and all authors contributed to data analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by PH and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was funded by a Canadian Institute for Health Research Operating Grant: SARS-CoV-2 variants supplement stream grant (Grant # VS1-175546).

Thank you to Meera Parthipan for assistance with the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Goel V. Building public health ontario: experience in developing a new public health agency. Can J Public Health. (2012) 103:e267–e9. doi: 10.1007/BF03404233

2. Public Health Agency of Canada. Chief Public Health Officer's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2021 Ottawa: Government of Canada (2021). Available onine at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/state-public-health-canada-2021.html (accessed February 8, 2022).

3. Alhassan JAK, Gauvin L, Judge A, Fuller D, Engler-Stringer R, Muhajarine N. Improving health through multisectoral collaboration: enablers and barriers. Can J Public Health. (2021) 112:1059–68. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00534-3

4. Bteich M, Da Silva Miranda E, El Khoury C, Gautier L, Lacouture A, Yankoty LI, et al. Proposed core model of the new public health for a healthier collectivity: how to sustain transdisciplinary and intersectoral partnerships. Crit Public Health. (2019) 29:241–56. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2017.1419167

5. Mondal S, Van Belle S, Maioni A. Learning from intersectoral action beyond health: a meta-narrative review. Health Policy Plan. (2021) 36:552–71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa163

6. Government of Canada. School Health. (2022). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/school-health.html#a2 (accessed July 13, 2022).

7. Díaz-Castro L, Ramírez-Rojas MG, Cabello-Rangel H, Sánchez-Osorio E, Velázquez-Posada M. The analytical framework of governance in health policies in the face of health emergencies: a systematic review. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:791 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.628791

8. Côté D, Durant S, MacEachen E, Majowicz S, Meyer S, Huynh AT, et al. A rapid scoping review of Covid-19 and vulnerable workers: intersecting occupational and public health issues. Am J Ind Med. (2021) 64:551–66. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23256

9. Buchan SA, Smith PM, Warren C, Murti M, Mustard C, Kim JH, et al. Incidence of outbreak-associated Covid-19 cases by industry in Ontario, Canada, 1 April 2020–31 March 2021. Occup Environ Med. (2022) 79:403–11. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2021-107879

10. Xia Y, Ma H, Moloney G, Garcia HAV, Sirski M, Janjua NZ, et al. Geographic concentration of SARS-CoV-2 cases by social determinants of health in metropolitan areas in canada: a cross-sectional study. CMAJ. (2022) 194:E195. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.211249

11. Clarke AE, Friese C, Washburn R (editors). Situational Analysis in Practice: Mapping Research with Grounded Theory. New York, NY: Routledge (2016).

12. Gurel E. Swot analysis: a theoretical review. J Int Soc Res. (2017) 10:994–1006. doi: 10.17719/jisr.2017.1832

14. Srivastava A, Thomson SB. Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. J Admin Governance. (2009) 4:72. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2760705

15. Ministry of Health. Covid-19 Guidance: Workplace Outbreaks. (2021). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/2019_workplace_outbreak_guidance.pdf (accessed April 15, 2022).

16. Government of Alberta. Occupational Health and Safety Guidance for Workers: Respiratory Viruses Edmonton. (2022). Available online at: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/6304396f-81d7-4b8b-abb0-0c96e726752c/resource/9f890bad-0008-4d12-813f-c183671de748/download/lbr-covid-19-information-ohs-guidance-for-workers-respiratory-viruses-2022-02.pdf (accessed April 16, 2022).

17. Lysyk B. Chapter 3: Reports on Value-for-Money Audits Toronto, Ontario: Queen's Printer for Ontario. (2019). Available online at: https://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en19/v1_307en19.pdf (accessed October 25, 2022).

18. Workers' Compensation Board Alberta,. Infectious Diseases: General. (2022). Available online at: https://www.wcb.ab.ca/assets/pdfs/workers/WFS_Infectious_diseases.pdf (accessed April 15, 2022).

19. Wilson K. The complexities of multi-level governance in public health. Can J Public Health. (2004) 95:409–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03403981

20. Lippel K. Occupational Health and Safety and Covid-19: Whose Rights Come First in a Pandemic? In: Flood CM MacDonnell V Philpott J Thériault S Venkatapuram S Fierlbeck K, editors. Vulnerable: The Law, Policy and Ethics of Covid-19. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. (2020).

21. Mojtahedzadeh S. They Made Doors, Gum and Jerry Cans. Ontario's ‘Essential' Workers in Manufacturing Accounted for More Workplace Covid Deaths Than Any Other Sector—Even Health Care Toronto. Ontario: Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd. Available online at: https://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/2022/10/27/they-made-tile-gum-and-jerry-cans-ontarios-essential-workers-in-manufacturing-accounted-for-more-workplace-covid-deaths-than-any-other-sector-even-health-care.html (accessed October 30, 2022).

22. Upshur REG. Principles for the justification of public health intervention. Can J Public Health. (2002) 93:101–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03404547

23. Watterson A. Covid-19 in the UK and occupational health and safety: predictable not inevitable failures by government, and trade union and nongovernmental organization responses. J Environ Occup Health Policy. (2020) 30:86–94. doi: 10.1177/1048291120929763

24. Cadnum JL, Donskey CJ. If You can't measure it, you can't improve it: practical tools to assess ventilation and airflow patterns to reduce the risk for transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 and other airborne pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2022) 43:915–17. doi: 10.1017/ice.2022.103

25. Coates P,. Airborne Transmission Not Revolutionary—It's Déjà Vu Toronto: Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd. (2022). Available online at: https://www.thestar.com/nd/opinion/contributors/2022/01/26/airborne-transmission-not-revolutionary-its-dj-vu.html (accessed April 16, 2022).

Keywords: public health systems research, population surveillance, occupational exposure, occupational health, interdisciplinary, COVID-19

Citation: Hopwood P, MacEachen E, Majowicz SE, Meyer SB and Amoako J (2022) “We need to talk to each other”: Crossing traditional boundaries between public health and occupational health to address COVID-19. Front. Public Health 10:1046628. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1046628

Received: 16 September 2022; Accepted: 17 November 2022;

Published: 06 December 2022.

Edited by:

Roberta Pirastu, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Miftachul Huda, Sultan Idris University of Education, MalaysiaCopyright © 2022 Hopwood, MacEachen, Majowicz, Meyer and Amoako. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ellen MacEachen, ZWxsZW4ubWFjZWFjaGVuQHV3YXRlcmxvby5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.