95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 13 December 2022

Sec. Public Health Education and Promotion

Volume 10 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1040952

This article is part of the Research Topic Achieving Impacts at Scale in Early Childhood Interventions: Innovations in Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning View all 20 articles

Introduction: Violence against children (VAC) is a violation of child rights, has high prevalence in low- and middle-income countries, is associated with long-term negative effects on child functioning, and with high economic and social costs. Ending VAC at home and at school is thus a global public health priority.

Methods: In Jamaica, we evaluated an early childhood, teacher-training, violence-prevention programme, (the Irie Classroom Toolbox), in a cluster-randomised trial in 76 preschools. The programme led to large reductions to teachers' use of VAC, although the majority of teachers continued to use VAC at times. In this paper, we describe a mixed-method evaluation of the Irie Classroom Toolbox in the 38 Jamaican preschools that were assigned to the wait-list control group of the trial. In a quantitative evaluation, 108 preschool teachers in 38 preschools were evaluated at pre-test and 91 teachers from 37 preschools were evaluated at post-test. One preschool teacher from each of these 37 preschools were randomly selected to participate in an in-depth interview as part of the qualitative evaluation.

Results: Preschool teachers were observed to use 83% fewer instances of VAC across one school day after participating in the programme, although 68% were observed to use VAC at least once across two days. The qualitative evaluation confirmed these findings with all teachers reporting reduced use of violence, but 70% reporting continued use of VAC at times. Teachers reported that the behaviour change techniques used to deliver the intervention increased their motivation, knowledge and skills which in turn led to improved child behaviour, improved relationships and improved professional well-being. Direct pathways to reduced use of VAC by teachers were through improved child behaviour and teacher well-being. The main reasons for continued use of VAC were due to barriers teachers faced using positive discipline techniques, teachers' negative affect, and child behaviours that teachers perceived to be severe.

Discussion: We describe how we used the results from the mixed-method evaluation to inform revisions to the programme to further reduce teachers' use of VAC and to inform the processes of training, supervision and ongoing monitoring as the programme is scaled-up through government services.

Violence against children (VAC) is a global public health problem with high prevalence in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Two thirds of children aged 2–4 years living in LMIC, equivalent to more than 220 million children, experience physical punishment or psychological aggression at home (1, 2). Over half a billion children each year experience violence in and around schools, including VAC by teachers (3). Article 19 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child states that children have the right to be protected from “all forms of physical and mental violence” and VAC is a clear violation of children's rights. VAC has long-term negative effects on children's physical and mental health and academic achievement and increases the risk for later perpetration of child and spousal abuse thus leading to an intergenerational cycle of violence (1, 2, 4–6). There are also large economic costs associated with VAC. In a 2014 report, global costs of VAC were estimated to be $7 trillion (between 3 and 8% of global GDP) (7), while a more recent report on ending violence in schools estimated that school violence alone costs US$11 trillion in lost future earnings caused by children learning less while in school and dropping out of school (3).

With the need to protect child rights, the high prevalence, the long-term negative effects on child functioning, and the high economic costs of VAC, ending violence against children is recognised as a global public health priority. Eliminating violence against children is included in the Sustainable Development Goals with goal 16.2 calling for an end to all forms of violence against children (8). The Global Partnership to End Violence against Children was created in 2016 to address this goal (https://www.end-violence.org) and the World Health Organisation launched the INSPIRE framework which includes seven evidence-based strategies for ending VAC (9). One of these strategies involves implementing parent and caregiver support programmes.

There is growing evidence from LMIC that violence prevention, parenting programmes can be effective in reducing parents' use of VAC at home (10, 11), although most studies have been small efficacy trials and evidence is needed on their effectiveness at scale. There is some limited evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to prevent VAC by primary and secondary school teachers (12–14), but less work has been conducted in early childhood educational settings such as preschools and childcare centers. Ending teachers' use of VAC is critical as schools reach large numbers of children and children spend a large amount of time there. The mission of schools is to promote children's learning, social-emotional competence, wellbeing, and life skills. VAC by teachers leads to school drop-out, poor health and wellbeing, physical injury, and low levels of learning (3). Interventions to prevent violence at school can thus support schools to achieve their mission of providing quality education. Early childhood is a particularly sensitive period for children's development and safe, secure, stimulating and nurturing early childhood caregiving environments promote children's cognitive and behavioural functioning and their longer-term health and development (15).

In Jamaica, violence against young children is common at school and at home with 84% of parents of children aged two-to-four years reporting using physical punishment over the past month (16) and 88% of preschool teachers observed to use VAC over two school days (17). There is thus an urgent need for violence-prevention programming during the early childhood years. This need has been recognised at the national level – Jamaica is a pathfinder country in the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children and the government has launched ‘The National Plan of Action for an Integrated Response to Children and Violence' (18). To respond to the need for violence-prevention programming, we have developed, implemented, and evaluated two early childhood programmes to reduce VAC at school and at home: (1) the Irie Classroom Toolbox: a teacher-training programme (17, 19), and (2) the Irie Homes Toolbox: a parenting programme (20, 21).

During the initial development, implementation, and evaluation of The Irie Toolbox programs, we have utilised key implementation science principles to increase the likelihood that the program will be integrated into the existing early childhood educational system in a sustainable way and maintain effectiveness at scale. These principles include designing the interventions for scale from the outset (19, 20), and embedding monitoring and evaluation activities, (including quantitative, qualitative and process evaluations), into ongoing programme implementation with lessons learnt used to inform revisions to the intervention (20, 22–24). We have given an overview of the processes involved in designing, implementing, evaluating, and initial scaling of the Irie Toolbox programmes in a recent article (Baker-Henningham et al.)1. The processes used include principles of the measurement for change approach that advocates using a monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) system guided by five interconnected concepts (25). In the Measurement for Change approach, MEL systems strive to be: (1) dynamic (flexible and responsive), (2) inclusive (involving all stakeholders), (3) informative (collecting and utilising information from a variety of sources), (4) interactive (measuring interactions among participants), and (5) people centered (acknowledging and measuring individual differences). Through utilising this framework, ECD researchers and practitioners can ensure that their MEL systems are used to adapt and iteratively revise interventions to meet changing needs as they are scaled up.

This article demonstrates how we used the Measurement for Change approach by embedding MEL activities into one round of implementation of the Irie Classroom Toolbox. At the time of this study, we had previously evaluated the Irie Classroom Toolbox in a cluster randomised controlled trial in seventy-six preschools and demonstrated that the Toolbox led to large reductions in teachers' use of VAC and significant improvements to the quality of the classroom environment, class-wide child prosocial behaviour and teacher wellbeing (17). However, the majority of teachers continued to use VAC at times indicating the need to further strengthen the intervention. The data for this study was collected when the Irie Classroom Toolbox was implemented with teachers in the preschools originally assigned to the wait-list control group of the trial. The aim was to collect quantitative and qualitative data that would inform future implementation of the Irie Classroom Toolbox including: 1) revisions to the content of the intervention to strengthen effectiveness in reducing VAC by teachers, 2) the design of the training and supervision processes as the programme is scaled-up through government services, and 3) the development of monitoring tools required to promote quality implementation. We conducted a pre-post quantitative evaluation of the effect of the intervention on teachers' use of violence against children, the quality of the classroom environment, class-wide child behaviour and teacher depressive symptoms to evaluate the benefits of the Toolbox training with this cohort of teachers. We also conducted a qualitative evaluation of the intervention to investigate teachers' perceptions of the mechanisms of action of the intervention.

This mixed-method study was conducted with the wait-list control arm of a cluster-randomised trial in community preschools in Kingston and St. Andrew, Jamaica. Community preschools cater to children aged 3–6 years and are run by community organisations with government support and oversight. In the original trial, 76 preschools were randomly selected from 120 eligible preschools to participate in the study. Preschools were eligible to participate if they had two-to-four classes of children, a minimum of ten children in each class and were located in urban areas of Kingston and St Andrew. All teachers and all classrooms in selected preschools participated in the study. Preschools were randomly assigned to receive the Irie Classroom Toolbox program (n = 38) or to a waitlist control group (n = 38). Measurements were conducted at baseline (May–June, 2015), post-test (May–June, 2016), and one-year follow-up (May–June, 2017) in all 76 preschools. The results of this trial have been published previously (17).

From August 2017 to April 2018, teachers in the preschools allocated to the waitlist control group participated in the Irie Classroom Toolbox training program. All teachers in the sample preschools participated in the study. Measurements conducted from May–June, 2017 in these 38 schools (the one-year follow-up point of the original trial) were used as the pre-test measurements in this study. Post-test measurements were conducted from May–June 2018. For the qualitative evaluation, we randomly selected one teacher from each preschool to participate in an in-depth, semi-structured interview. No teachers refused to participate. Interviews were conducted in June 2018.

Ethical approval for the study was given by the School of Psychology, Bangor University ethics committee (2014-14167) and the University of the West Indies ethics committee (ECP 50, 14/15). Written, informed consent was obtained from the preschool principal and all preschool teachers in each school to participate in the study. Separate written informed consent was obtained for teachers selected to participate in the in-depth interviews.

Teachers were trained in the Irie Classroom Toolbox through four full-day teacher training workshops, eight one-hour sessions of in-class support (once a month for 8 months) and fortnightly text messages. The Irie Classroom Toolbox trains teachers in classroom behaviour management and how to promote children's social and emotional skills (20). See Table 1 for full details of the intervention.

We had previously implemented the Irie Classroom Toolbox over a full school year with teachers in the 38 schools assigned to the intervention group in the cluster-randomised trial. During this year, workshop facilitators and in-class coaches received ongoing supervision and support and ongoing revisions were made to the teacher-training and in-class support manuals to address problems and needs as they arose. Hence during this second round of implementation, the staff were more experienced and confident and the facilitator manuals were more comprehensive. The content and process of implementation of the Toolbox and the materials given to the teachers remained largely unchanged.

Measurements included quantitative and qualitative data. All quantitative measurements have been used previously in early childhood classrooms in Jamaica (17, 22).

The primary outcome was teachers' use of violence against children measured through independent structured observations throughout one school day. Event sampling was used to record each discrete act of violence against children including teachers' use of: (1) physical violence (e.g., hitting with hand or object, pinching, poking, forcefully pushing or pulling a child, making a child stand or kneel in uncomfortable positions), and (2) psychological aggression (e.g., name-calling, threatening physical punishment, encouraging children to hit or harm each other, using non-verbal threats). The total score was the number of times the teacher used violence against children throughout the day (see Supplementary material). All behaviours were defined in an observation manual with clear definitions of each behaviour, examples and non-examples, and decision rules.

Secondary outcomes included observations of the classroom environment, a binary measure of observed teachers' use of violence across two schools days, and teacher depressive symptoms. The observations of the classroom environment included: (1) two measures of the quality of the classroom environment assessed using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System Pre-K (CLASS Pre-K): emotional support and classroom organisation (26), and (2) two measures of class-wide child behaviour: class-wide child aggression and class-wide child prosocial behaviour assessed using rating scales that measured the frequency, intensity and number of children involved in aggressive and prosocial behaviour respectively. These classroom observations were conducted over five 20-minute periods over one school day with the mean score over the five observations used in the analyses. They were scored on a seven-point rating scale (1–7) where 1 = low and 7 = high. During these five 20-minute observation periods, the observers also recorded whether teachers used violence against children (including physical punishment and psychological aggression) and a binary score of teachers' use of violence over two school days was created. Teacher depressive symptoms was measured by interviewer-administered questionnaire using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (27).

Data was collected by a team that included ten teacher observers who conducted observations of teachers' use of violence across one school day, ten classroom observers who conducted observations of the classroom environment over another school day and one teacher interviewer. To prevent bias, the observers and teacher interviewer were unaware that the teachers had participated in an intervention. Teachers were not masked. Each classroom was observed for five 20-minute periods over one school day by a classroom observer and then on a second day, a teacher observer conducted observations of teachers' use of violence across the whole school day. When all observations in the preschool were completed, the teacher interviewer visited the school to conduct teacher interviews. Only one observer was present in a classroom at a time and a maximum of two observers were present in a preschool each day.

Training for observers was conducted over a 4 week period at each measurement point and included 1 week of in-office training, 2 weeks of field training and 1 week to conduct interobserver reliabilities prior to the start of data collection. Interobserver reliabilities were measured using intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and were >0.8 for all classroom observations and > 0.9 for observations of teachers' use of violence over one school day. We conducted ongoing reliabilities once a week with each observer throughout each data collection period and interobserver reliabilities of ICC > 0.8 for observations of the classroom environment and ICC > 0.9 for teachers' use of violence were maintained.

The measure of teachers' depressive symptoms (CES-D) had high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha= 0.88 at pre-test, 0.89 at post-test) and high test-retest over a 2 week period (ICC = 0.82). For the observational measures, we previously calculated stability over 1 year using data from the wait-list control group (17). Stability was in the expected range for all outcomes except class-wide prosocial behaviour which showed low stability: teachers use of violence against children, ICC = 0.63; emotional support, ICC = 0.48; classroom organisation, ICC = 0.42; class-wide aggression, ICC = 0.59; class-wide prosocial behaviour, ICC = 0.13; violence against children over two school days, ICC = 0.51.

In-depth semi-structured interviews with each teacher selected to participate in the qualitative evaluation were conducted by one of two research assistants who had not worked with these teachers previously. Both research assistants were female with Masters' degrees in Psychology. They received 10 days' training in conducting the in-depth interviews including theory, demonstration, role play and supervised practice interviewing teachers. The interview focussed on how the intervention led to changes in teachers' use of VAC and/or reasons for teachers' continued use of VAC. The interview guide was developed by MB and HBH and piloted by MB, HBH and the two interviewers with four teachers who were not selected to participate in the in-depth interviews. The interview guide is shown in Table 2. Interviews were conducted in a quiet area on the school property, after all post-test measurements in the school were completed, and were scheduled in advance at a time convenient for the teachers. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 min and was audio-recorded and then transcribed. Transcriptions were independently checked for accuracy against the audiotape. Each teacher was given an identification number to preserve their anonymity. Children's, teachers' and schools' names were excluded from the transcriptions.

The difference between pre-test and post-test scores was analysed using a Wicoxon Paired Signed Rank Test for teachers' use of violence over one school day, a paired t-test for all other continuous variables, and a Chi-Squared test for the binary variable of teachers' use of violence over two school days. Teachers' depressive symptoms was normalised using a square root transformation prior to conducting the paired t-test.

Qualitative Data was analysed manually using the framework approach which is appropriate for applied policy research that has specific objectives and is based on a priori issues (28). The framework approach involves five steps: (1) reading and rereading the transcripts in a familiarisation phase, (2) constructing an index of codes based on the themes and subthemes in the data, (3) applying the codes to the transcripts, (4) creating tables to collate all codes related to each theme and subtheme, and 5) interpreting the data. Steps one and two were conducted by MB and HBH who read six transcripts and collaborated on developing the coding index using inductive and deductive methods. Initial codes were generated using the interview guide and inductive codes were added as new themes and subthemes emerged from the data. In step three, all text was coded and where a section of text included more than one code, all relevant codes were applied. In step four, the data was reorganised into tables of each theme/subtheme and we report the number of participants who mentioned each subtheme as an indication of its salience within the data. In step five, we examined the data and constructed mechanism diagrams to represent teacher reports of the pathways to their reduced use of VAC and continued use of VAC. Data was coded by MB in discussion with HBH with regular meetings to address any queries. In addition, another member of the Irie Toolbox team independently coded six teacher transcripts and we found acceptable levels of agreement (>80% on all codes). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with HBH and MB.

In May-June, 2017, data was collected with 108 teachers in 38 preschools. In May-June, 2018, post-test data was collected with 91 teachers in 37 preschools: a loss of one preschool and seventeen teachers. Fourteen teachers had left the school and three teachers were principals who were no longer responsible for teaching a class. There were no significant differences between those found and lost on classroom or teacher characteristics or on pre-test scores of the outcome variables (see Supplementary Table 1).

Teacher and classroom characteristics are shown in Table 3. At pre-test, teachers used a median [interquartile range (IQR)] of 6 (1–18) instances of violence over one school day and 16 (17.6%) of teachers used no violence over two school days (Table 4). Scores for the quality of the classroom environment (emotional support and classroom organisation) and for class-wide child aggression were in the mid-range and scores for class-wide prosocial behaviour were in the low range.

At post-test, there was an 83% reduction in teachers' use of violence across one school day [median (IQR) = 1 (0–1), p < 0.001] and a significant increase in the proportion of teachers using no violence over two school days [29 teachers (31.9%), p = 0.00] (Table 4). There were significant increases from pre-test to post-test for emotional support [standardised difference (d) = 0.43], classroom organisation (d = 0.43), and class-wide child prosocial behaviour (d = 0.26). Reductions to teacher depressive symptoms were marginally significant (d = −0.20, p = 0.06). There was no change in class-wide child aggression (d = 0.09, p = 0.36).

Thirty-seven teachers (one from each school at post-test), participated in the in-depth interviews. There were no refusals. All participants were female, participants had been teaching for a median (IQR) of 15.0 years (8.5–23.5), thirty-three (89.2%) had completed high school, and sixteen (43.2%) had completed a teacher-training qualification. There were no significant differences between teachers who participated in the in-depth interviews and those who were not selected on teacher and classroom characteristics or on pre-test measures of the study outcomes (see Supplementary Table 2).

Teachers who participated in the in-depth interviews also had similar engagement and participation in the intervention as the full sample (see Table 1 for details of full sample). The subsample of teachers attended a mean (SD) of 2.9 (1.0) workshops, participated in a mean (SD) of 7.8 (0.7) in-class support sessions, and completed a mean (SD) of 3.5 (2.8) classroom assignments.

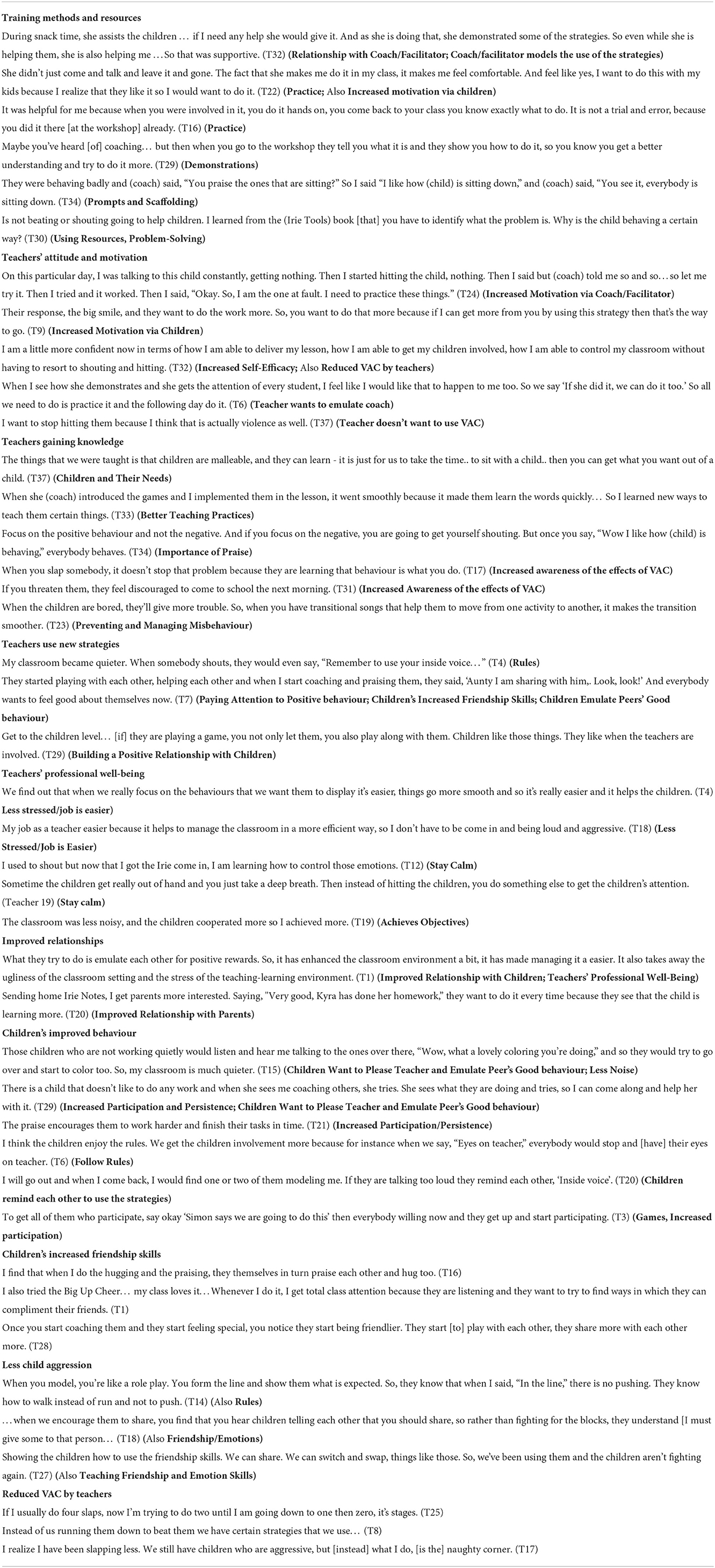

The results of the qualitative evaluation are presented in two main categories: (1) teacher-reported pathways to reduced use of VAC, and (2) teachers' reports of why they continue to use VAC. The pathways are illustrated in Figures 1, 2. In the figures, each box represents a theme and subthemes are listed within each box with the numbers of teachers mentioning each subtheme in parenthesis.

Figure 1. Teachers' reports of the pathways to their reduced use of violence against children (VAC).

Teachers reported that the training methods used led to increases in their: (1) motivation to use the strategies, (2) knowledge about child development, appropriate teaching practices and behaviour management, and (3) skills in using the strategies. Teachers reported bidirectional influences between their skills in using the strategies and their motivation and knowledge with motivation and knowledge leading to increased skills and use of the skills leading to further increases in teachers' motivation and knowledge. According to teachers' reports, their use of the strategies led to increased professional wellbeing, improved relationships with children and parents, and improvements in child behaviour including increased friendship skills and reduced child aggression. As teachers recognised the benefits of the programme to themselves (through increased wellbeing and better relationships) and to the children (in terms of improved behaviour), this further increased their use of the positive discipline strategies introduced through the programme. There was evidence of two direct pathways to reduced VAC by teachers: 1) increases in teachers' use of the strategies, and 2) increased teachers' professional wellbeing. See Figure 1 and Table 5 for sample quotes.

Table 5. Teachers' reports of factors that led to a reduction in their use of violence against children.

The behaviour change techniques used in the intervention were valued by teachers including the use of demonstration, practice, modeling, positive feedback, prompting, fun, collaborative problem-solving and provision of resources. There was a special salience around the theme of relationships with teachers reporting increased positive relationships between facilitators and teachers, between teachers and children, between teachers and parents, and among the children. Teachers described their workshop-facilitators and in-class coaches as being supportive and they felt comfortable freely sharing the challenges that they experienced in the classrooms. This resulted in the teachers feeling motivated to continue using the strategies, even during difficulties. For example:

“She motivated me… She was calm even when you say you can't bother, she would just [say] ‘Alright, try this way, try that way.' So, when she is not here you just remember everything. You want to do your job well, so you just try everything…try all the strategies that she taught you. (Teacher 14) (Increased motivation via Coach/Facilitator).

Teachers reported that their use of the strategies led to improved relationships with the children and their parents. Teachers also reported improved relationships among children in terms of increased friendship skills and less aggression:

“…when we encourage them to share, you find that you hear children telling each other that you should share, so rather than fighting for the blocks, they understand [that] I can't have it all, I must give some to that person… (Teacher 18) (Children's improved friendship skills; Less aggression)

Teachers' reported feeling motivated to use the strategies: (1) when they received positive feedback from the facilitator/coach, (2) when the coach explained the rationale for using the strategies, and (3) because they wanted to emulate the coach.

“…It pushes me more to motivate the children. Because she is praising me, it pushes me to teach them more. If I can feel that way, can you imagine how the children would feel? So that's what I do, I motivate them more. I praise them more.” (Teacher 27) (Increased Motivation via Coach/Facilitator)

They also felt motivated to use the strategies more when they saw the benefits to the children.

I do it every single day. Because the children love it, they love when you praise them. They smile and they always try to do something more for me to praise them. (Teacher 32) (Increased Motivation via Children)

Most teachers reported increased knowledge related to early childhood education including: (1) understanding of children and their needs, (2) using more supportive and fun teaching practices, (3) the importance of praise and positive attention, (4) how to prevent and manage child misbehaviour and/or (5) the effects of using violence against children. For example, a teacher described the ineffectiveness of corporal punishment in promoting positive behaviour:

“I realise that when I hit them, I have to be constantly hitting them. But when I start to praise the others, that works better.” (Teacher 24) (Increased Awareness of VAC and Its Effects)

All teachers reported increased use of praise and positive attention and nearly all reported teaching and promoting the classroom rules. The other most commonly used strategies were building positive relationships with the children, teaching friendship and emotion skills, problem-solving when difficulties arose in the classroom, use of warnings, time-out and other appropriate consequences for child misbehaviour, and interactive reading. Overall, teachers reported using strategies that promote appropriate behaviour the most, and using strategies to manage misbehaviour less frequently. There was evidence of a direct pathway between use of positive discipline strategies and reduced VAC by teachers:

“Instead of hitting on a child or shouting at a child, I just use the rules.” (Teacher 6) (Rules)

“Instead of beating them...I say, ‘I like how (child) is doing this' and then everybody wants to do it.” (Teacher 26) (Paying attention to positive behaviour)

All teachers reported that the use of positive discipline strategies led to improved child behaviour (including increased friendship skills and/or decreased aggression).

“We get the children's involvement more because for instance when we say eyes on teacher, everybody would stop and their eyes on teacher. When we say use inside voice everybody would whisper instead. And not that loud talking.” (Teacher 6) (Rules, Follow classroom rules)

Teachers reported that a key mechanism to reduced VAC was through their own professional wellbeing, including reduced stress and increased emotional self-regulation. Teachers learnt to stay calm rather than react to children's behaviour in anger, and this helped them to use positive discipline strategies rather than resort to VAC.

“The training has taught me to pause, I use the word pause because instead of jumping to say something that you shouldn't, you remember and you pause; instead of shouting, you remember and you pause; instead of administering corporal punishment, you remember and you pause, and in these pauses you can think of the strategies that were introduced to you and can figure out in your head which one to use.” (Teacher 36) (Stay calm)

There was evidence of a bidirectional relationship between teachers' use of the positive discipline strategies and teachers' professional wellbeing as utilising the strategies also led to fewer child misbehaviours and reduced teachers' frustration and stress.

“Before the training programme I would be focusing on the negative behaviour, shouting at that person, calling to that person and wasting a lot of time and draining my energy and so forth.” (Teacher 29) (Less stressed/job is easier)

“Because the friendship skills cuts down some of the shouting, the fighting, it doesn't frustrate me so much.” (Teacher 27) (Teaching friendship skills, Less child aggression, Less frustration)

The majority of teachers (26/37 (70%) reported that they continued to use VAC at times. The main reasons given for continued use of VAC were due to barriers in implementing the positive discipline strategies, as a response to perceived child misbehaviour, and due to poor emotional self-regulation (Figure 2). Less commonly mentioned reasons were due teachers' attitudes and beliefs to VAC and parent influences. See Table 6 for examples of quotes.

Teachers reported several barriers to their consistent use of the strategies in the classroom. Some strategies were perceived to be ineffective, to work inconsistently, to take too much effort and/or take too long to work in practice. These barriers to strategy use were sometimes related to the context in which the teachers worked. Some teachers reported that larger class sizes and/or insufficient space and resources made it difficult for them to consistently use the strategies.

You want the right behaviours now… but some strategies (now just have to..) just take time. The most I had this week is 19 - I find that I can use the strategies with this number of children, but when me have 27 pikney (children) in front of me oh my gosh you going to say things, you don't want it to come out. (Teacher 2) (Strategies take too long to work)

In addition, some teachers of three-year-old children reported that strategies involving teaching rules, friendship and emotion skills were less effective and/or difficult to use with the younger children; while a teacher of the 5–6-year-old children (who were transitioning to primary school), disagreed with some strategies as she believed that the focus on positive behaviour and praise wouldn't prepare children for the primary school classroom.

“You have to remember that they are small but at the same time you have to teach them that they are going into a different world (primary school) where they're not going to get that (praise).” (Teacher 33) (Disagree with strategy)

There was also some evidence that teachers equated non-violent consequences with VAC use in that they considered either strategy to be appropriate for certain behaviours and didn't appear to differentiate between them:

“You spoke to her once and she do it again and the third, so 3 strikes and you are out and so she always let the three strikes catch her so she have to get a little pat or she go in the time-out corner.” (Teacher 9) (Equating consequences with VAC)

Teachers reported using VAC for child misbehaviours that they perceived to be particularly severe, especially repeated misbehaviour and aggressive behaviour.

“You only clap them when they harm another person or they are trying to harm themselves.” (Teacher 14) (Aggressive behaviour)

“If I'm teaching the class and the child is being disruptive and I speak to the child and the child continues, I will give the child a slap or two.” (Teacher 19) (Repeated misbehaviour)

Another important pathway to continued VAC by teachers was due to teachers' negative affect (e.g., frustration and anger). When teachers were frustrated by children's behaviour, they were more likely to resort to VAC.

“You know when you see certain behaviour and you just feel upset and all that you just want to knock the child.” (Teacher 15) (Teachers' negative affect)

Others reported feeling frustrated when they used the strategies, and they are ineffective or took too long to correct the behaviour.

“If I keep talking to a child for one particular incident over and over I tend to get irritated at some point or another and as I said I would hold the child and physically, ‘Sit! I said you are to sit.”' (Teacher 1) Teachers' negative affect)

A minority of teachers reported a direct link between their attitudes to VAC and VAC use. For example, some teachers reported that VAC was an effective method of managing child misbehaviour and some teachers believed that VAC was an acceptable form of punishment as long as it didn't lead to severe physical abuse:

“I remember when I was going to school and I get, is not slap I get. They beat you. A tap, right. There is nothing wrong with that. When you take up a belt and beat a child, that is where something is wrong.” (Teacher 21) (VAC is acceptable if it is not severe)

Parent influences were mentioned by a small minority of teachers. This included: 1) parents not disciplining children at home, leading to severe child misbehaviour at school, 2) parents supporting VAC use by teachers, and 3) parents' use of VAC at home justifying teachers' use of VAC at school.

“I will ask them, ‘Your parents slap you at home?' It's like something they are used to. So, if the teacher slaps you, it's like nothing.” (Teacher 14) (Parents use VAC at home)

In a pre-post evaluation, the Irie Classroom Toolbox reduced VAC by teachers by 83% and increased the proportion of teachers using no violence by 14%. However, 68% of teachers were observed to use VAC at least once over 2 days of observation at post-test. These findings were corroborated through the qualitative evaluation with all teachers reporting reduced VAC, but 70% reporting continuing to use VAC at times. The reductions in teachers' use of VAC were accompanied by significant benefits to the observed quality of the classroom environment and class-wide prosocial behaviour, although no benefits were found for class-wide child aggression. Reductions were also found for teachers' depressive symptoms. Teachers reported that the behaviour change techniques used in the intervention led to increased motivation, knowledge and skills which in turn led to improved child behaviour, improved relationships and improved professional wellbeing. There was evidence of bidirectional influences with improved child behaviour, relationships and professional wellbeing also leading to increased use of positive discipline skills by teachers which in turn increased teachers' motivation and knowledge. Teachers reported that the direct mechanisms to reduced VAC were through their increased use of positive discipline strategies and improved professional wellbeing. The main reasons for teachers' continued use of VAC were due to barriers faced in using the positive discipline strategies, teachers negative affect and certain child behaviours, especially child repeated misbehaviour and child aggression. Attitudes to violence and parental influences were also mentioned as reasons for continued use of VAC by a minority of teachers.

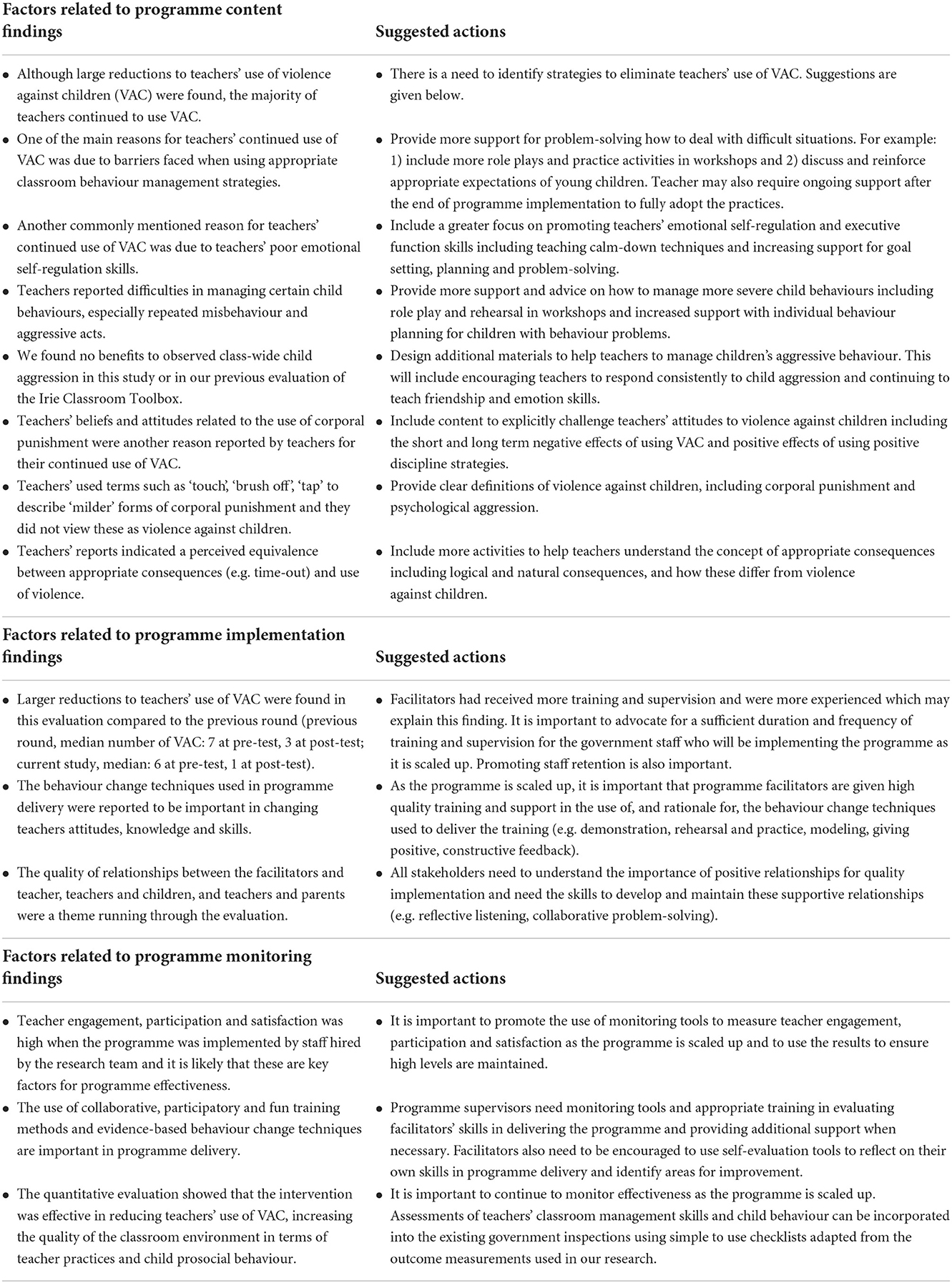

The findings from this mixed method evaluation are useful for informing revisions to the content of the programme to strengthen its effectiveness in reducing violence against children by teachers (see Table 7). For example, the in-depth interviews highlight the importance of training in alternative discipline and emotional self-regulation as these are key factors in the pathways to reduced VAC and are also reasons given for teachers' continued use of VAC. These factors have been recognised as core components of effective violence-prevention parenting programmes (29), and were also described as the most salient mechanism to reduced VAC by parents who participated in the Irie Homes Toolbox (24). Previous qualitative evaluations of violence-prevention programmes in primary schools in LMIC have also reported that training in alternative discipline strategies is a key mechanism to reduced VAC by teachers (22, 30) with emotional regulation (22), improved relationships (22, 30) and improved child behaviour (22) also being described as being on the pathway of change. An important finding was that some teachers understood corporal punishment to be more severe child abuse and they did not differentiate between appropriate consequences (such as time-out) and slapping a child. In Uganda, teachers and students expressed a similar belief that VAC is acceptable if it is proportionate and fair (30). Addressing teachers' knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to VAC may be one strategy for further reducing VAC by teachers.

Table 7. Using the results of the mixed method assessment to inform the further scale-up of the Irie Classroom Toolbox.

The Irie Classroom Toolbox has been designed to be integrated into the early childhood educational network in Jamaica with training and supervision to be provided by government early childhood officers as part of their routine duties. The findings from our MEL activities give insights into teachers' preferred training methods and the mechanisms of action of the intervention, thus providing important guidance related to programme implementation and programme monitoring as it is scaled up in Jamaica (see Table 7). This includes the importance of using evidence-based behaviour change techniques, fun and interactive training methods and building supportive relationships between facilitators and participants. Qualitative evaluations of early childhood parenting programmes in LMIC have highlighted the importance of these techniques in promoting engagement and learning (31–33) and there is growing empirical evidence of their importance for participant engagement [(34); Bernal et al.]2 and programme effectiveness (34, 35) (see footnote 2). In addition, we reported larger reductions to teachers' use of VAC in this round of implementation compared to our previous round (see Table 7) (17). The main difference in implementation was the fact that the programme staff were more experienced and had received more training and supervision. This highlights the importance of providing sufficient training and ongoing supervision to programme staff as learning to utilise effective training methodologies requires practice with skills developing over time (34, 36). As the programme is scaled up, it will also be important to continue to monitor intervention implementation including: (1) teacher satisfaction and engagement with the intervention, (2) facilitators' skills in implementing the intervention, and (3) the effectiveness of the intervention on teacher and child outcomes (Table 7).

Our MEL activities also point to the limitations of teacher-training alone for eliminating VAC at school. Corporal punishment is banned by law in Jamaican early childhood institutions and yet as seen in this study, VAC continues to be widely used. Reviews of the global status of VAC in schools indicate that this situation is common across many countries with legal bans (37, 38). In Jamaica, education and training alone was insufficient for ensuring teachers' compliance with the law against corporal punishment and monitoring and enforcing compliance is also necessary. In addition, interventions to change attitudes and beliefs relating to VAC within the wider community may be necessary. Implementing complementary teacher and parent, early childhood violence prevention programmes is one step in this process to ensure a shared understanding and co-ordinated approach to positive discipline at home and at school. Conducting violence-prevention programmes in primary and secondary schools with the aim of preventing VAC by teachers in all educational institutions could also help change societal attitudes toward VAC at school. Additionally, mass media campaigns may be helpful for awareness raising and behaviour change at the population level (39, 40).

This study has demonstrated the value of MEL activities to inform future implementation of an early childhood, violence prevention, teacher-training programme. The study illustrates four of the five concepts described in the Measurement for Change framework. The MEL activities were informative and dynamic in that information was gained from quantitative and qualitative methods and this information was used to guide future decision-making related to the content, process of delivery and future monitoring of the intervention as it is implemented at scale. We found evidence of the importance of MEL activities being interactive from the salience of the theme of relationships in the qualitative data. Teachers reported that the positive, supportive relationships they had with the facilitator were mirrored in their relationships with children and parents and in more friendly behaviours among the children. Including methods for monitoring relationships will be an important component of the MEL process as the programme is scaled-up. A further illustration of the interactive concept is given in the evidence of bidirectional effects (see Figure 1). For example, teachers use of positive discipline strategies led to improved child behaviour and improved child behaviour encouraged teachers to use the strategies more. Finally, the data from the MEL activities illustrate the importance of being people-centered. Different teachers faced different challenges and expressed different needs related to implementing the intervention. Although the content of the Irie Classroom Toolbox is relevant for all teachers, how this content is operationalised in each teachers' individual classroom context will differ. Furthermore, additional support may be required at times, for example, in emotional self-regulation skills, in dealing with specific child behaviours, and/or in changing norms and attitudes to VAC. In this study, our MEL activities were not inclusive as due to resource constraints, we were only able to collect data from teachers and classrooms, and not from other relevant stakeholders.

The strengths of the study include the mixed-method approach that included quantitative and qualitative data. The qualitative data triangulated the results of the quantitative data and provided valuable information on the perspectives of teachers relating to the mechanisms of action of the intervention and reasons for continued VAC use. Incorporating participant perspectives into MEL activities is an essential component of the Measurement for Change Approach (25). Measurements were conducted by persons masked to the study design and most had good psychometric properties, with the exception of class-wide child prosocial behaviour which had low stability. Although, 16% of teachers were lost at post-test, there was no differences between those lost and found on any of the characteristics measured at pre-test. In addition, we randomly selected one teacher from each school to participate in the in-depth interviews and the selected teachers were not significantly different from those not selected on pre-test characteristics and had similar levels of engagement and satisfaction with the intervention. The views of the teachers who participated in the in-depth interviews are thus likely to be reasonably representative of the wider sample. The measurements of teachers' use of VAC were through independent observation, thus reducing the bias of teacher reports which tend to underestimate VAC use (40, 41). The young age of the children prevented the use of child-reported measures. It is possible that teachers behaved differently during the observational assessment. However, the presence of the observer is generally non-intrusive in these preschool classrooms given the structural conditions, with high noise levels and several classrooms sharing a common space. In addition, there is evidence that when observations conducted over a whole school day, the effects of an observer on teacher behaviour are reduced (42) and in our trial we found reductions in teachers' use of VAC did not differ across the school day (17).

The limitations of the study are that this was a pre-post study with no untreated control group. Furthermore, as the preschools were in the wait-list control group of a cluster-randomised trial, they had participated in multiple rounds of measurement which may have resulted in changes to teachers' behaviour. Only thirty-seven teachers (one per preschool) participated in the in-depth interviews and hence the reported mechanisms of action require cautious interpretation and need to be investigated in future empirical research. Social desirability bias may also have influenced teachers' responses during these interviews as the teachers were aware that the interview was being conducted on behalf of the Irie Toolbox Team. All respondents were female which reflects the lack of male early childhood teachers in Jamaica (only 1/91 teacher (1.1%) in the study preschools was male). It is possible that male teachers may experience the intervention differently. We conducted the in-depth interviews at the end of the intervention only and hence we were unable to track teachers' perceptions of the mechanisms of change throughout the intervention implementation and we did not have the resources to get feedback from teachers on the interpretation of the results. In addition, in this study, we only report data from teachers and classrooms. Other important stakeholders include parents, government field officers and their supervisors, members of the school board, and members of the local communities. It will be important to include the perspectives of a wider group of stakeholders in future studies. Finally, all participating preschools were situated in urban areas and future studies need to include preschools from rural and semi-rural areas of Jamaica.

In this study, we demonstrate how embedding MEL activities into ongoing intervention implementation can help to plan for implementation at scale. We used a mixed-method evaluation of the Irie Classroom Toolbox when implemented with teachers in preschools from the wait-list control group of a cluster-randomised trial. We had previously demonstrated that the Toolbox led to large reductions in teachers' use of VAC, although the majority of teachers continued to use VAC at times (17). The MEL activities in this round of implementation confirmed these findings and provided insights into teachers' perspectives of the mechanism of action of the intervention and their reasons for continuing to use VAC. The information is useful for preparing additional content to further reduce and ultimately eliminate VAC by teachers. In addition to strengthening the intervention, the MEL activities also provide valuable information to guide the process of scaling the intervention, including provision of high-quality training, supervision and ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by School of Psychology, Bangor University Ethics Committee and University of the West Indies Ethics Committee. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HB-H contributed to funding acquisition. MB and TF contributed to project investigation and data curation. MB and HB-H contributed to data analysis. MB wrote the original draft. HB-H and TF reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the study and project administration.

This research was funded by the Medical Research Council UK, the Wellcome Trust, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) (grant number MR/M007553/1).

We thank the principals, teachers, parents, and children who participated in this study, the intervention facilitators, and the data collectors.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1040952/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Baker-Henningham H, Bowers M, Francis T. The process of scaling early childhood violence prevention programs in Jamaica. Special issue on promoting early childhood globally through caregiving interventions. Pediatrics (submitted).

2. ^Bernal R, Gomez ML, Perez-Cardona S, Baker-Henningham H. Quality of implementation of a parenting program in Colombia and its effect on child development and parental investment. Pediatrics (submitted).

1. McCoy D, Seiden J, Cuartas J, Pisani L, Waldman M. Estimates of a multidimensional index of nurturing care in the next 1000 days for children in low- and middle-income countries: a modeling study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2022) 6:324–34. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00076-1

2. Cuartas J, McCoy DC, Rey-Guerra C, Britto PR, Beatriz E, Salhi C. Early childhood exposure to non-violent discipline and physical and psychological aggression in low- and middle-income countries: national, regional, and global prevalence estimates. Child Abuse Negl. (2019) 92:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.021

3. Woden Q, Fevre C, Male C, Nayihouba A, Nguyen H. Ending Violence in Schools: An Investment Case. Washington, DC: The World Bank and the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children. (2021).

4. Gershoff E. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull. (2002) 128:539–79. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539

5. Heilmann A, Mehay A, Watt R, Kelly Y, Durrant JE, van Turnhout J. et al. Physical punishment and child outcomes: a narrative review of prospective studies. Lancet. (2021) 398:355–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00582-1

6. Hillis SD, Mercy JA, Saul JR. The enduring impact of violence against children. Psychol Health Med. (2017) 22:393–405. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1153679

7. Pereznieto P, Montes A, Routier S, Langston L. The Costs and Economic Impact of Violence Against Children. London: Overseas Development Institute, Child Fund Alliance (2014).

8. United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. (2015). Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed August 29, 2022).

9. World Health Organization. INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. Geneva: WHO (2016).

10. Branco M, Altafim E, Linhares M. Universal intervention to strengthen parenting and prevent child maltreatment: updated systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2021) 23:1658–1676. doi: 10.1177/15248380211013131

11. McCoy A, Melendez-Torres GJ, Gardner F. Parenting interventions to prevent violence against children in low- and middle-income countries in East and Southeast Asia: a systematic review and multi-level meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 103:104444. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104444

12. Devries KM, Knight L, Child JC, Mirembe A, Nakuti J, Jones R, et al. The good school toolkit for reducing physical violence from school staff to primary school students: a cluster randomised controlled trial in Uganda. Lancet Glob Health. (2015) 385:e378–86. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00060-1

13. Nkuba M, Hermenau K, Goessmann K, Hecker T. Reducing violence by teachers using the preventative intervention interaction competencies with children for teachers (ICC-T): a cluster randomized controlled trial at public secondary schools in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0201362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201362

14. Ssenyonga J, Katharin H, Mattonet K, Nkuba M, Hecker T. Reducing teachers' use of violence toward students: A cluster-randomized controlled trial in secondary schools in Southwestern Uganda. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2022) 138:106521. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106521

15. Black M, Walker S, Fernald L, Andersen C, DiGirolamo A, Lu C, et al. For the lancet early childhood development series steering committee. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. (2016) 389:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

16. Lansford J. Deater-Deckard K. Childrearing discipline and violence in developing countries. Child Dev. (2012) 83:62–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01676.x

17. Baker-Henningham H, Bowers M, Francis T, Vera-Hernandez M, Walker S. The Irie classroom toolbox, a universal violence-prevention teacher-training programmme, in jamaican preschools: a single-blind, cluster randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e456–68. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00002-4

18. Government of Jamaica. National Plan of Action for an Integrated Response to Children and Violence (NPACV) 2018-2023. Kingston, Jamaica. (2018).

19. Baker-Henningham H. The Irie classroom toolbox: developing a violence prevention, preschool teacher training program using evidence, theory and practice. Ann NY Acad Sci. (2018) 1419:179–200. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13713

20. Francis T, Baker-Henningham H. Design and implementation of the irie homes toolbox. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:282961. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.582961

21. Francis T, Baker-Henningham H. The Irie Homes Toolbox: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of an early childhood parenting program to prevent violence against children in Jamaica. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2021) 126:106060. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106060

22. Baker-Henningham H, Scott Y, Bowers M, Francis T. Evaluation of a violence-prevention program with Jamaican primary school teachers: a cluster randomized trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2797. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152797

23. Baker-Henningham H, Walker S. Effect of transporting an evidence-based violence prevention intervention to Jamaican preschools on teacher and class-wide child behavior: a cluster randomised trial. Glob Ment Health. (2018) 5:e7. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2017.29

24. Francis T, Baker-Henningham H. A qualitative evaluation of the mechanism of action in an early childhood parenting programme to prevent violence against children in Jamaica. Child Care Health Dev. (2022) 27:1–12. doi: 10.1111/cch.13074

25. Krapels J, van der Haar L, Slemming W, de Laat J, Radner J, Sanou AS, et al. The aspirations of measurement for change. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:568677. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.568677

26. Pianta R, La Paro K, Hamre B. Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) Manual. Pre-K. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Pub Co. (2008).

27. Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

28. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In M. Huberman, H. Miles, editors, The Qualitative Researcher's Companion. London: Sage Publications. (2002), p 305–29.

29. Melendez-Torres G, Leijten P, Gardner F. What are the optimal combinations of parenting intervention components to reduce physical child abuse recurrence? reanalysis of a systematic review using qualitative comparative analysis. Child Abuse Rev. (2019) 28:181–97. doi: 10.1002/car.2561

30. Kyegombe N, Namakula S, Mulindwa J, Lwanyaaga J, Naker D, Namy S, et al. (2017). How did the Good School Toolkit reduce the risk of past week physical violence from teachers to students? Qualitative findings on pathways of change in schools in Luwero, Uganda. Soc Sci Med. (2017) 180:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.008

31. Smith JA, Baker-Henningham H, Brentani A, Mugweni R, Walker SP. Implementation of reach up early childhood parenting program: acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility in Brazil and Zimbabwe. Ann NY Acad Sci. (2018) 1419:120–40. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13678

32. Gomez ML, Bernal R, Baker-Henningham H. Qualitative evaluation of a scalable early childhood parenting programme in rural Colombia. Child Care Health Dev. (2022) 48:225–38. doi: 10.1111/cch.12921

33. Singla DR, Kumbakumba E. The development and implementation of a theory-informed, integrated mother-child intervention in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. (2015) 147:242–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.069

34. Luoto JE, Lopez-Garcia I, Aboud FE, Singla DR, Zhu R, Otieno R, et al. An implementation evaluation of a group-based parenting intervention to promote early childhood development. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:653106. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.653106

35. Araujo MC, Dormal M, Rubio-Codina M. Quality of Parenting Programs and Child Development Outcomes: The Case of Peru's Cuna Mas. IDB Working Paper Series No IDB-WP-951. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. (2018).

36. Yousafzai AK, Rasheed MA, Siyal S. Integration of parenting and nutrition interventions in a community health program in Pakistan: an implementation evaluation. Ann NY Acad Sci. (2018) 1419:160–78. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13649

37. Gershoff ET. School corporal punishment in global perspective: prevalence, outcomes and efforts at intervention. Psychol Health Med. (2017) 22:224–39. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1271955

38. Heekes SL, Kruger CB, Lester SN, Ward CL, A. Systematic review of corporal punishment in schools: global prevalence and correlates. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2022) 23:52–72. doi: 10.1177/1524838020925787

39. Kasteng F, Murray J, Cousens S, Sarrassat S, Steel J, Meda N, et al. Cost-effectiveness and economies of scale of a mass radio campaign to promote household life-saving practices in Burkino Faso. BMJ Glob Health. (2018) 3:e000809. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000809

40. Sarrassat S, Meda N, Badolo H, Ouedraogo M, Some H, Bambara R, et al. Effect of a mass radio campaign on family behaviours and child survival in Burkino Faso: a repeated cross-sectional, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:e330–341. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30004-4

41. Merrill KG, Smith SC, Quintero L, Devries KM. Measuring violence perpetration: stability of teachers' self-reports before and after an anti-violence training in Cote d'Ivoire. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 109:104687. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104687

Keywords: violence prevention, teacher-training, violence against children, early childhood, preschool, behaviour change, low-and middle-income country

Citation: Bowers M, Francis T and Baker-Henningham H (2022) The Irie Classroom Toolbox: Mixed method assessment to inform future implementation and scale-up of an early childhood, teacher-training, violence-prevention programme. Front. Public Health 10:1040952. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1040952

Received: 09 September 2022; Accepted: 21 November 2022;

Published: 13 December 2022.

Edited by:

Wiedaad Slemming, University of the Witwatersrand, South AfricaReviewed by:

Vidisha Vallabh, Swami Rama Himalayan University, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Bowers, Francis and Baker-Henningham. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helen Baker-Henningham, aC5oZW5uaW5naGFtQGJhbmdvci5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.