- 1Department of Psychiatry, Wuhan Mental Health Center, Wuhan, China

- 2Department of Clinical Psychology, Wuhan Hospital for Psychotherapy, Wuhan, China

- 3Department of Outpatient and Emergency, Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Background and objectives: Integrating sleep health into primary care is a promising approach to narrow the treatment gap for insomnia in older adults but data regarding the epidemiological characteristics of insomnia among elderly primary care attenders (EPCAs) are very limited. This study examined the prevalence and correlates of clinical insomnia among Chinese EPCAs.

Methods: By using two-stage consecutive sampling method, a total of 757 EPCAs were recruited from seven urban and six rural primary care centers in Wuhan, China. The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (15 item version) were administered to assess insomnia severity and depressive symptoms, respectively.

Results: The two-week prevalence of clinical insomnia (ISI score ≥ 15) was 28.9%. Significant correlates of clinical insomnia were: female sex (vs. male, OR = 2.13, P < 0.001), fair and poor family relationship (vs. good, OR = 1.59, P = 0.028), hypertension (OR = 1.67, P = 0.004), heart disease (OR = 1.73, P = 0.048), arthritis (OR = 2.72, P = 0.001), and depressive symptoms (OR = 4.53, P < 0.001).

Conclusion: The high prevalence of clinical insomnia among Chinese EPCAs suggests a high level of sleep health need in older patients in China's primary care settings. Considering the many negative outcomes associated with insomnia, it is necessary to integrate sleep health into primary care in China.

Introduction

While insomnia is prevalent among the general population, in particular among the elderly population, it is often under-recognized, under-diagnosed, and under-treated (1–4). For example, in a recently published population-based survey in Hebei, China, as high as 9.4 and 21.9% of the residents aged 18–59 years and 60 years and older suffered from insomnia symptoms, respectively, as defined by a cut-off score of seven or greater on the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) (5). However, the corresponding rates of visiting a doctor for sleep problems in the past year among individuals with insomnia of the two age-groups were as low as 5.5 and 6.8%, respectively (6). In an international survey across four high-income countries (France, Italy, Japan, and the USA), overall, 15.8% of the adults with a history of insomnia had consulted a physician about their sleep problems, 10.6% of those who consulted physicians were prescribed a drug for the sleep problems, and 6.2% of those who were prescribed drugs were still taking these drugs at the time of this survey (7). Taken together, these data suggest the high level of unmet needs in insomnia management in both the adult and elderly population in China and other countries in the world.

Given the wide availability and easy accessibility of primary care services in most countries in the world (8, 9), primary care physicians (PCPs) are in a unique position to detect older adults with sleep problems and initiate treatment at an early stage when it may be more cost-effective. In the case of China, because of its limited mental health service resources and their unequal distribution between urban and rural regions, and older adults' preference for seeking health services at primary care settings, particularly rural older adults, integrating sleep health into primary care has been a very promising approach to narrow the treatment gap for insomnia and other common mental health problems in older adults (10–13). To facilitate the planning and provision of sleep healthcare services in primary care settings, it is necessary to have the knowledge on the epidemiological characteristics of insomnia among elderly primary care attenders (EPCAs) in China.

In comparison to the numerous studies on insomnia in community-dwelling older adults (4, 14, 15), studies examining insomnia in EPCAs have been very limited. To date, three studies have investigated the prevalence and correlates of insomnia in older adults attending primary care, of which only one was conducted in China (16–18). By using DSM-III-R, Hohagen and colleagues assessed the presence of insomnia in a sample of 330 older patients from the offices of five general practitioners in Mannheim, Germany, and found a 23% prevalence of insomnia and its three significant correlates in older general practice patients: female sex, depression, and organic brain syndrome (16). In Kerala, India, Dahale and colleagues used the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) to examine insomnia in 1,574 EPCAs from 71 primary care centers and found that 11.8% of the EPCAs suffered from clinical insomnia (17). Factors associated with insomnia in EPCAs in this study included older age, female sex, chronic medical illness, common mental disorders, and greater disability (17). In an urban primary care center in Shanghai, China, Xu and colleagues used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to screen for insomnia in a volunteer sample of 90 EPCAs and found the insomnia prevalence was 53.9%; however, this study did not analyze correlates of insomnia (18). Limitations of the only available study in China include the convenient sampling, the small sample size, and no inclusion of rural EPCAs. Further, although PSQI is often used to screen for insomnia with reasonable accuracy, it has been criticized for lack of specificity and its problematic factor construct and, strictly speaking, it is only suitable for the discrimination between “good” and “poor” sleepers, not individuals with and without insomnia (19–23). Therefore, the epidemiology of insomnia in Chinese EPCAs remains largely unknown.

To fill the above knowledge gaps, the current study was set out to investigate the prevalence and correlates of clinical insomnia in EPCAs from both urban and rural primary care centers in Wuhan, the largest city with more than 10 million residents in central China (24, 25).

Methods

Participants and sampling

Between October 2015 and November 2016, we conducted a large-scale cross-sectional survey among 791 EPCAs in seven urban and six rural primary care centers in Wuhan, China (8, 10, 26, 27). The outcomes of interest of this study included quality of life, common mental health problems, psychosocial problems, and insomnia. The present study focused on insomnia. Participants were recruited via two-stage cluster consecutive sampling. In brief, the first stage purposively selected 13 primary care centers from the 13 districts (seven urban and six rural) in Wuhan, one center each district, which were located in or nearest to the most populous area of the district. The second stage consecutively invited older patients who were 65 years old or over and seeking treatment at these primary care centers during the survey period of this study to participate. Patients who refused to participate and were not able to complete the survey due to severe physical illnesses and cognitive impairment and psychotic symptoms were excluded.

Before the fieldwork of this survey, the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wuhan Mental Health Center. All participants provided written informed consent before the interview.

Questionnaire and procedures

The survey instrument was a questionnaire, which was specifically developed for this study and was administered by trained PCPs of the selected primary care centers in a face-to-face interview format.

Socio-demographic variables in the questionnaire were age, sex, education, marital status, self-rated financial status (good, fair, poor), residence place, living arrangement (alone or with others), and self-rated relationship with family members (good, fair, poor).

Lifestyle factors included smoking and physical exercise. Current smokers were those who were currently smoking at least one cigarette per day on at least 5 days per week (10). Respondents participating in physical exercise regularly were those having the habit of physical exercise (27).

A checklist was used to ascertain the presence of six chronic medical conditions: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and arthritis.

The validated Chinese Geriatric Depression Scale, 15-item version (GDS-15), was used to assess depressive symptoms (28–30). The total score of the GDS-15 is the sum of the 15 items, with a possible range of 0–15 and a cut-off score of five or more indicating clinically significant depressive symptoms in China (31).

We used the validated Chinese ISI to evaluate insomnia in the past 2 weeks, which is developed according to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for insomnia and consists of seven items scoring from “0 = none” to “4 = very severe” (32, 33). The ISI total score ranges from zero to 28, with ≥ 15 being considered as clinical insomnia (23, 34).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of clinical insomnia was calculated. Chi-square test was used to compare rates of insomnia between/across subgroups according to characteristics such as sex and education levels. Binary logistic regression analysis with the forward selection (Wald) method was used to examine the independent correlates of insomnia. Statistically significant variables from the Chi-square test were included into the multiple logistic regression model. Odds Ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to quantify the associations between insomnia and correlates. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05 (two-sided). SPSS software version 15.0 package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

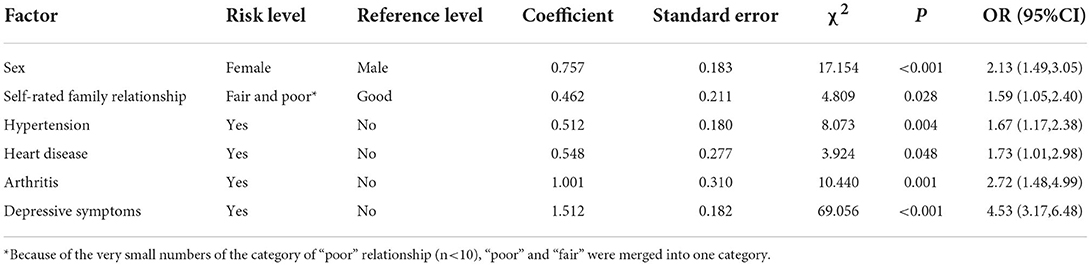

In total, 757 EPCAs completed the survey questionnaire. The mean age of the study participants was 72.78 years (standard deviation = 5.99, range = 65–97) and 407 (53.8%) were women. Characteristics of the study sample and prevalence rates of clinical insomnia by variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample of elderly primary care attenders and prevalence rates of clinical insomnia by sample characteristics.

In total, 219 elderly patients (28.9%) had clinical insomnia (ISI score ≥ 15) during the past 2 weeks.

Results from Chi-square test (Table 1) display that significantly higher rates of clinical insomnia were observed in women (vs. men), in illiterate patients (vs. middle school and above), in patients with poor financial status (vs. good), in patients having poor and fair family relationship (vs. good), in patients suffering from hypertension, in patients suffering from heart disease, in patients suffering from COPD, in patients suffering from arthritis, and in patients having depressive symptoms (P ≤ 0.032).

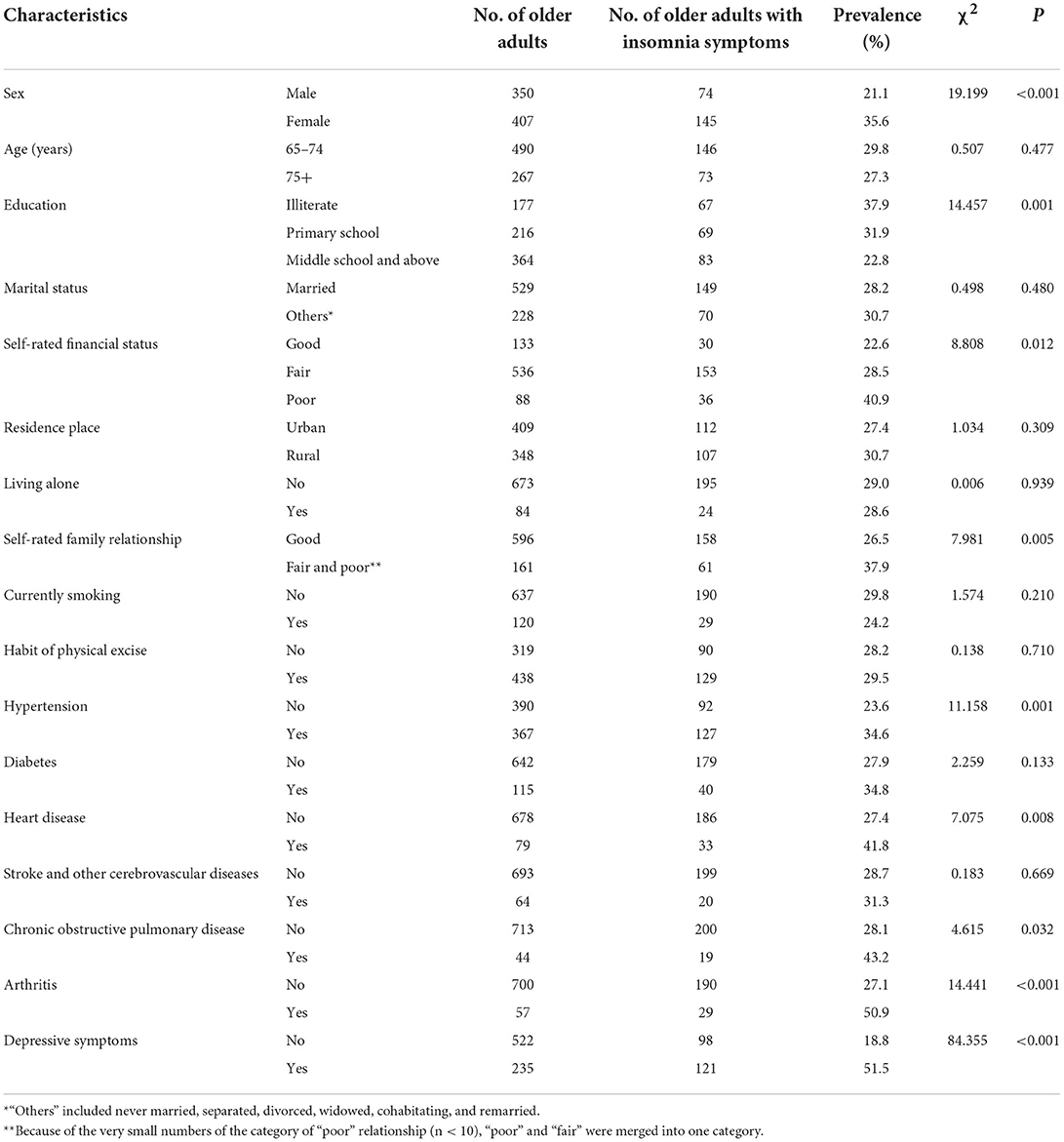

Six significant correlates of clinical insomnia were identified (Table 2): female sex (vs. male, OR = 2.13, P < 0.001), fair and poor family relationship (vs. good, OR = 1.59, P = 0.028), hypertension (OR = 1.67, P = 0.004), heart disease (OR = 1.73, P = 0.048), arthritis (OR = 2.72, P = 0.001), and depressive symptoms (OR = 4.53, P < 0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in China that examined the epidemiological characteristics of insomnia in older adults attending primary care centers. The main findings are the 28.9% prevalence of clinical insomnia in EPCAs and six correlates of insomnia in this patient population: female sex, fair and poor family relationship, hypertension, heart disease, arthritis, and depressive symptoms.

In population-based studies using ISI and the same definition of clinical insomnia, the prevalence rates of clinical insomnia in rural community-residing older adults and older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in China were 19.2 and 15.6%, respectively (22, 35). Compared to these prevalence estimates in the elderly population, we found a much higher prevalence of clinical insomnia in Chinese EPCAs. The 28.9% prevalence of insomnia in Chinese EPCAs is also much higher than the 11.8% prevalence of insomnia in India EPCAs (17). Because both older age and major medical conditions are major risk factors for insomnia in population-based studies (5, 35, 36), the elevated risk of insomnia in Chinese EPCAs might be primarily due to the older age and poor physical health of this older and physically ill population. In addition, we speculated that the very low treatment rate of insomnia in the elderly population in China might partly explain the high risk of insomnia in EPCAs (6).

In line with previous studies (15–17, 35, 37), we found the greater risk of insomnia in EPCAs who were women, had fair and poor family relationship, and were depressed. The higher prevalence of insomnia in females may be ascribed to their more vulnerability to negative socioeconomic factors and stressful life events in comparison to males (38). Further, women are more likely to develop common mental health problems, including depression and anxiety, which could result in elevated risk of insomnia in women (37). The close relationship between depression and insomnia has been consistently reported in various populations including the EPCAs (16, 17, 35, 39). The reciprocal relationship between depression and insomnia might be explained by their shared pathophysiological pathways, including gut microbiome composition, genetic overlap, and neurotransmitter system in the brain (40). The traditional Chinese culture values filial piety and family harmony, which are significant determinants of mental wellbeing in older Chinese adults (41, 42). Because Confucianism is deeply rooted in values, beliefs, and attitudes of older Chinese adults (43), the significant association of insomnia with fair and poor family relationship, an indicator of family disharmony, is expected.

The etiology of insomnia is multifactorial and involves various social, mental, and physical factors (15). In the literature, medical conditions linked with insomnia include cancer, heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, arthritis, chronic pain, and gastrointestinal problems (44–46). Our findings on the significant associations of insomnia with hypertension, heart disease, and arthritis are consistent with prior studies. The physical discomfort, pain, and feelings of depression and stress caused by major medical conditions may explain the elevated risk of insomnia in EPCAs with hypertension, heart disease, and arthritis.

This study has a few limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study, so the causality between identified correlates and insomnia cannot be inferred in EPCAs. Longitudinal data are warranted to answer this clinical question. Second, we did not assess the recognition and treatment of insomnia in EPCAs by PCPs and older patients' attitudes toward sleep health services provided in general practice, which are important for the planning of sleep health services in Chinese primary care centers. Third, some factors associated with insomnia such as social support, chronic pain, and environmental noise were not measured in this study.

In conclusion, nearly 30% of the Chinese EPCAs suffer from clinical insomnia, suggesting a high level of sleep health need in older patients in China's primary care settings. Considering the many negative outcomes associated with insomnia and the inadequate mental health service resources in China (25), it is necessary to integrate sleep health into primary care. Sleep health services for Chinese EPCAs need to include periodic screening for insomnia, expanded psychosocial supports, effective management of major medical conditions and depression, and, when necessary, referral to psychiatrists and sleep specialists. Further, services for EPCAs would be more effective if they targeted those who are women, have fair and poor family relationship, suffer from several chronic medical conditions such as hypertension and arthritis, and are depressed.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wuhan Mental Health Center (approval number WMHC-IRB-S065). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

B-LZ: acquisition and analysis of data for the study, drafting the article, and interpretation of data for the study. H-JL and Y-MX: design and acquisition of data for the study. X-FJ and B-LZ: drafting the article, revising the article for important intellectual content, and interpretation of data for the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 71774060), 2015 Irma and Paul Milstein Program for Senior Health Awards from the Milstein Medical Asian American Partnership Foundation, the Young Top Talent Programme in Public Health from Health Commission of Hubei Province (PI: B-LZ), and Wuhan Health and Family Planning Commission (Grant Number: WX18C12, WX17Q30, WG16A02, and WG14C24). The funding source listed had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the research staff for their team collaboration work and all the older adults and primary healthcare physicians involved in this study for their cooperation and support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Dopheide JA. Insomnia overview: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring, and non-pharmacologic therapy. Am J Manag Care. (2020) 26:S76–84. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2020.42769

2. McCall WV. Sleep in the elderly: burden, diagnosis, and treatment. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. (2004) 6:9–20. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0104

3. Xu Y, Li C, Zhu R, Zhong BL. Prevalence and correlates of insomnia symptoms in older Chinese adults during the COVID-19 outbreak: a classification tree analysis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2022) 35:223–8. doi: 10.1177/08919887221078561

4. Cao XL, Wang SB, Zhong BL, Zhang L, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. The prevalence of insomnia in the general population in China: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0170772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170772

5. Wang W, Shi H, Jia H, Sun J, Li L, Yang Y, et al. A cross-sectional study of current status and risk factors of insomnia among adult residents in Hebei province. Chin Ment Health J. (2021) 35:455–60. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2021.06.003

6. Sun L, Li K, Zhang Y, Zhang L. Sleep-related healthcare use prevalence among adults with insomnia symptoms in Hebei, China: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e057331. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057331

7. Leger D, Poursain B. An international survey of insomnia: under-recognition and under-treatment of a polysymptomatic condition. Curr Med Res Opin. (2005) 21:1785–92. doi: 10.1185/030079905X65637

8. Zhong BL, Ruan YF, Xu YM, Chen WC, Liu LF. Prevalence and recognition of depressive disorders among Chinese older adults receiving primary care: a multi-center cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 260:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.011

9. Almeneessier AS, Alamri BN, Alzahrani FR, Sharif MM, Pandi-Perumal SR. Insomnia in primary care settings: still overlooked and undertreated? J Nat Sci Med. (2018) 1:64–8. doi: 10.4103/JNSM.JNSM_30_18

10. Zhong BL, Xu YM, Xie WX, Liu XJ. Quality of life of older Chinese adults receiving primary care in Wuhan, China: a multi-center study. PeerJ. (2019) 7:e6860. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6860

11. Chen WC, Chen SJ, Zhong BL. Sense of alienation and its associations with depressive symptoms and poor sleep quality in older adults who experienced the lockdown in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2022) 35:215–22. doi: 10.1177/08919887221078564

12. Zhong BL, Xiang YT. Challenges to and recent research on the mental health of older adults in china during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2022) 35:179–81. doi: 10.1177/08919887221078558

13. Hua R, Ma Y, Li C, Zhong B, Xie W. Low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cognitive decline. Science Bulletin. (2021) 66:1684–90. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2021.02.018

14. Lu L, Wang SB, Rao W, Zhang Q, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. The prevalence of sleep disturbances and sleep quality in older chinese adults: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Behav Sleep Med. (2019) 17:683–97. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2018.1469492

15. Morin CM, Jarrin DC. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, course, risk factors, and public health burden. Sleep Med Clin. (2022) 17:173–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2022.03.003

16. Hohagen F, Kappler C, Schramm E, Rink K, Weyerer S, Riemann D, et al. Prevalence of insomnia in elderly general practice attenders and the current treatment modalities. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (1994) 90:102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01563.x

17. Dahale AB, Jaisoorya TS, Manoj L, Kumar GS, Gokul GR, Radhakrishnan R, et al. Insomnia among elderly primary care patients in India. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. (2020) 22:258. doi: 10.4088/PCC.19m02581

18. Xu H, Huang L, Sheng Y. Investigation of the status quo of insomnia in visiting residents of a community in Shanghai. Shanghai Med Pharmaceutic J. (2019) 40:45–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1533.2019.18.014

19. Buysse DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger JD, Lichstein KL, Morin CM. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. (2006) 29:1155–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1155

20. Moul DE, Hall M, Pilkonis PA, Buysse DJ. Self-report measures of insomnia in adults: rationales, choices, and needs. Sleep Med Rev. (2004) 8:177–98. doi: 10.1016/S1087-0792(03)00060-1

21. Espie CA, Kyle SD, Hames P, Gardani M, Fleming L, Cape J. The Sleep Condition Indicator: a clinical screening tool to evaluate insomnia disorder. BMJ Open. (2014) 4:e004183. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004183

22. Zhang QQ Li L, Zhong BL. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in older chinese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). (2021) 8:779914. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.779914

23. Omachi TA. Measures of sleep in rheumatologic diseases: epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), functional outcome of sleep questionnaire (FOSQ), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). (2011) 11:S287–96. doi: 10.1002/acr.20544

24. Luo W, Zhong BL, Chiu HF. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2021) 30:e31. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000202

25. Zhong BL, Xu YM Li Y. Prevalence and unmet need for mental healthcare of major depressive disorder in community-dwelling chinese people living with vision disability. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:900425. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.900425

26. Zhong BL, Xu YM, Xie WX, Liu XJ, Huang ZW. Depressive symptoms in elderly Chinese primary care patients: prevalence and sociodemographic and clinical correlates. J Geriatr Psych Neur. (2019) 32:312–8. doi: 10.1177/0891988719862620

27. Zhong BL, Liu XJ, Chen WC, Chiu HF, Conwell Y. Loneliness in Chinese older adults in primary care: prevalence and correlates. Psychogeriatrics. (2018) 18:334–42. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12325

28. He X, Xiao S, Zhang D. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Geriatric Depression Scale: a study in a population of Chinese rural community-dwelling elderly. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2008) 16:473–5, 543.

29. Liu J, Wang Y, Wang X, Song R, Yi X. Reliability and validlity of the Chinese version of Geriatric Depression Scale among Chinese urban community-dwelling elderly population. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2013) 21:39–41.

30. D'Ath P, Katona P, Mullan E, Evans S, Katona C. Screening, detection and management of depression in elderly primary care attenders. I: the acceptability and performance of the 15 item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15) and the development of short versions. Fam Pract. (1994) 11:260–6.

31. Cao H, Zhang J, Guo R, Ye X. Comparison of reliability and validity of two scales in the evaluation of depression status in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. J Neurosci Ment Heal. (2017) 17:721–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6574.2017.10.010

32. Bai C, Ji D, Chen L, Li L, Wang C. Reliability and validity of insomnia severity index in clinical insomnia patients. Chinese J Pract Nurs. (2018) 34:2182–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1672-7088.2018.28.005

33. Li E. The Validity and Reliability of Severe Insomnia Index Scale. Guangzhou, China: Southern Medical University (2018).

34. Li E, Li W, Xie Z, Zhang B. Psychometric property of the Insomnia Severity Index in students of a commercial school. J Neurosci Mental Health. (2019) 19:268–72. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6574.2019.03.012

35. Yang JJ, Cai H, Xia L, Nie W, Zhang Y, Wang S, et al. The prevalence of depressive and insomnia symptoms, and their association with quality of life among older adults in rural areas in China. Front Psychiatr. (2021) 12:727939. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727939

36. Zhang J, Lu C, Tang J, Qiu H, Liu L, Wang S, et al. A cross-sectional study of sleep quality in people aged 18 years or over in Shandong Province. Chin J Psychiatry. (2008) 41:97–101. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1006-7884.2008.02.009

37. Zeng LN, Zong QQ, Yang Y, Zhang L, Xiang YF, Ng CH, et al. Gender difference in the prevalence of insomnia: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Psychiatr. (2020) 11:577429. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577429

38. Zhang B, Wing YK. Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. (2006) 29:85–93. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.85

39. Fang H, Tu S, Sheng J, Shao A. Depression in sleep disturbance: A review on a bidirectional relationship, mechanisms and treatment. J Cell Mol Med. (2019) 23:2324–32. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14170

40. Lancel M, Boersma GJ, Kamphuis J. Insomnia disorder and its reciprocal relation with psychopathology. Curr Opin Psychol. (2021) 41:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.02.001

41. Lam WW, Fielding R, McDowell I, Johnston J, Chan S, Leung GM, et al. Perspectives on family health, happiness and harmony (3H) among Hong Kong Chinese people: a qualitative study. Health Educ Res. (2012) 27:767–79. doi: 10.1093/her/cys087

42. Ren P, Emiliussen J, Christiansen R, Engelsen S, Klausen SH. Filial Piety, Generativity and older adults' wellbeing and loneliness in Denmark and China. Appl Res Qual Life. (2022) 22:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s11482-022-10053-z

43. Zhong BL, Chen SL, Tu X, Conwell Y. Loneliness and cognitive function in older adults: findings from the chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2017) 72:120–8. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw037

44. Bhaskar S, Hemavathy D, Prasad S. Prevalence of chronic insomnia in adult patients and its correlation with medical comorbidities. J Family Med Prim Care. (2016) 5:780–4. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.201153

45. Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Riedel BW, Bush AJ. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. (2007) 30:213–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.213

Keywords: insomnia, elderly, primary care, epidemiology, China

Citation: Zhong B-L, Li H-J, Xu Y-M and Jiang X-F (2022) Clinical insomnia among elderly primary care attenders in Wuhan, China: A multicenter cross-sectional epidemiological study. Front. Public Health 10:1026034. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1026034

Received: 23 August 2022; Accepted: 10 October 2022;

Published: 21 October 2022.

Edited by:

Liye Zou, Shenzhen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Han Qi, Capital Medical University, ChinaYandong Xu, University of Science and Technology of China, China

Copyright © 2022 Zhong, Li, Xu and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xue-Feng Jiang, MTMzMzE5MDE2MThAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Bao-Liang Zhong

Bao-Liang Zhong Hong-Jie Li1,2†

Hong-Jie Li1,2† Yan-Min Xu

Yan-Min Xu