95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 02 February 2022

Sec. Life-Course Epidemiology and Social Inequalities in Health

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.734968

This article is part of the Research Topic Social Determinants of Health Among Immigrants View all 5 articles

Jozaa Z. AlTamimi1

Jozaa Z. AlTamimi1 Reham I. Alagal1

Reham I. Alagal1 Nora M. AlKehayez1

Nora M. AlKehayez1 Naseem M. Alshwaiyat2

Naseem M. Alshwaiyat2 Hamid A. Al-Jamal3

Hamid A. Al-Jamal3 Nora A. AlFaris1*

Nora A. AlFaris1*Objective: Regular physical activity is essential for lifelong optimal health. Contrarily, physical inactivity is linked with risk for many chronic diseases. This study was conducted to evaluate the physical activity levels and factors associated with physical inactivity among a multi-ethnic population of young men living in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study involving 3,600 young men (20–35 years) living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Sociodemographic and physical activity data were collected from subjects by face-to-face interviews. Physical activity characteristics were evaluated by using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire. Weight and height were measured following standardized methods, then body mass index was calculated.

Results: Physical inactivity was reported among 24.9% of study subjects. The lowest and highest rates of physical inactivity were reported among subjects from the Philippines (14.0%) and Saudi Arabia (41.5%), respectively. There is a high variation in daily minutes spent on physical activities related to work, transport, recreation, vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activities and sedentary behaviors among study participants based on their nationalities. Nationality, increasing age, longer residency period in Saudi Arabia, living within a family household, having a high education level, earning a high monthly income, and increasing body mass index were significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity among the study participants.

Conclusion: Physical inactivity prevalence is relatively high among a multi-ethnic population of young men living in Saudi Arabia. The findings confirmed notable disparities in the physical activity characteristics among participants from different countries living in Saudi Arabia.

Physical activity is defined as any voluntary body movement performed by skeletal muscles and needs energy expenditure higher than the basal level (1). Regular physical activity has long been recognized as a protective factor in preventing and treating the most common chronic diseases, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and breast and colon cancers (2). It also plays a vital function in improving mental health and overall quality of life (3, 4). On the other hand, the lack of moderate to high physical activity in a person's lifestyle is defined as physical inactivity (5). Current evidence emphasized that over one-fourth of the world's adults are physically inactive (6). Physical inactivity has been recognized as a global public health problem and linked to increased morbidity and overall mortality among adults all over the world (7, 8). This has prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to target a 15% decrease in the global prevalence of physical inactivity in adults and adolescents by 2030 (5).

Saudi Arabia has experienced a rapid socio-economic transition in recent decades, which has coincided with changes in Saudi people's lifestyle toward sedentary behaviors due to urbanization and motorization (9). These lifestyle changes are occurring simultaneously with the rise in prevalence of obesity and other chronic diseases among Saudi people (10). In fact, the rise in obesity and chronic diseases in Saudi Arabia is primarily due to increased intake of unhealthy foods and a decrease in physical activity levels (9, 11, 12).

Interestingly, physical inactivity rates among adults vary greatly within and between countries, with certain adult subpopulations reporting rates as high as 80%. The Eastern Mediterranean, the Americas, Europe, and the Western Pacific areas have the highest rates of physical inactivity among adults, whereas the South-East Asia region has the lowest (13). These rates could be influenced by several factors such as economic growth, transportation patterns, technology use, and accepted cultural standards. During the previous few decades, Saudi Arabia has seen a tremendous influx of migrants, most of whom were young men from various Middle Eastern and Asian countries (14). Existing literature does not provide adequate information about physical activity levels and factors associated with physical inactivity among the multi-ethnic population of young men living in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to evaluate physical activity levels and factors associated with physical inactivity among young men from Saudi Arabia and eleven Middle Eastern and Asian countries.

This study is part of a larger research project entitled as the Relationship between Obesity, physical Activity, and Dietary pattern among men in Saudi Arabia (ROAD-KSA). It is a cross-sectional study that aimed to determine the prevalence of overweight and obesity, physical activity levels, and dietary patterns among young and middle-aged men from Saudi Arabia (reference group) and 11 Middle Eastern and Asian countries (Egypt, Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Sudan, Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines) residing in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, as well as the correlations between these factors. The current research was conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Study subjects were chosen randomly from public sites in Riyadh, including public gardens and shopping centers, using a stratified clustered sampling technique based on geographic areas in Riyadh. The Riyadh city was stratified into five areas (east, west, north, south and center), and each area was clustered into several neighborhoods. Two neighborhoods from each area were chosen randomly. Public gardens and shopping centers in the selected neighborhoods were targeted to recruit our participants randomly. The eligibility for participation includes young men between the ages of 20 and 35 who live in Riyadh, are free of any physical impairment, and have a single nationality from one of the following countries (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, Jordan, Sudan, Turkey, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines). Former to recruitment, subjects signed an informed consent form as required by the Helsinki Declaration. The research ethics committee of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, approved the study procedure.

Face-to-face interviews were used to collect sociodemographic data from study participants by trained researchers. Participants' nationality, age, length of stay in Saudi Arabia, household type, marital status, educational level, and monthly income are the sociodemographic parameters collected.

The weight and height of study subjects were measured by trained researchers. A training session about standardized methods for weight and height measurement was organized for all research team members before data collection to minimize personnel measurement bias. A calibrated digital weight scale was used to measure the body weight to the closest 100 g while wearing little clothing and without shoes. Furthermore, the subject's body height was measured to the closest 1 mm in full standing posture without shoes using a calibrated portable stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) was computed by dividing weight (kg) by height (m2) (15).

Physical activity levels of subjects were evaluated by using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ, version 2.0) developed by WHO (16). It has acceptable reliability and validity in measuring the physical activity of adults in surveillance studies (17). The GPAQ consists of 16 questions and collects information on physical activity participation in three different domains (work, transport, and recreation) and sedentary behavior. The intensity of physical activities studied with GPAQ is divided into two categories: moderate and vigorous-intensity activities. Physical activities that involve hard physical effort and create significant increases in respiration or heart rate are classified as vigorous-intensity activities, while physical activities that involve moderate physical effort and induce slight increases in breathing or heart rate are classified as moderate-intensity (18). The Metabolic Equivalent of Tasks (METs) is a standard unit of measurement for expressing physical activity intensity. When using GPAQ data to calculate a person's overall energy expenditure, time spent in moderate-intensity physical activities is given four METs, and time spent in vigorous-intensity physical activities is given eight METs. The GPAQ's first and third domains inquired about the number of usual weekly days and typical daily periods spent on vigorous and moderate-intensity work and recreation activities, respectively. The GPAQ's second domain inquired about the number of average weekly days and typical daily times spent on moderate-intensity transportation activities (18). The GPAQ also asked about typical daily times spent on sedentary behaviors. Sedentary behaviors are defined as sitting or reclining at work or home, including time spent travelling by vehicles, reading or watching television, but do not include time spent sleeping (18). The physical activity data were collected by face-to-face interviews conducted by trained researchers. Showcards developed by WHO for each type of activity covered by the GPAQ were used during physical activity data collection to help subjects recognize the domain of physical activity meant by each question.

According to the GPAQ analysis guide, The GPAQ categorized physical activity into three levels (high, moderate and low) based on specific criteria. The physical activity level is classified as high if a person reported vigorous-intensity activity on at least 3 days, with a minimum of 1,500 MET-minutes per week or seven or more days of any combination of walking or moderate or vigorous-intensity activities, with a minimum of 3,000 MET-minutes per week. The level of physical activity is classified as moderate if a person reported three or more days of vigorous-intensity activity of at least 20 min per day or 5 or more days of moderate-intensity activity of at least 30 min per day or 5 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate or vigorous-intensity activities achieving a minimum of 600 MET-minutes per week. Otherwise, the level of physical activity is classified as low if the above criteria were not satisfied (18). Subjects with low physical activity were considered physically inactive, while subjects with moderate or high physical activity were considered physically active (5, 19). Furthermore, the GPAQ data analysis results examined if WHO recommendations for physical activity had been met or not by each participant. WHO recommendations on physical activity for health include doing at least 150 min per week of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 min per week of vigorous-intensity physical activity or equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity achieving at least 600 MET-minutes per week (18). Other results generated from the GPAQ data analysis include total daily minutes spent on physical activity, daily minutes spent on various physical activity domains (work, transportation and recreation), daily minutes spent on vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activities, the proportion of daily minutes spent on various physical activity domains from total daily minutes spent on physical activity, the proportion of daily minutes spent on vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activities from total daily minutes spent on physical activity, percent of participants doing no physical activities related to various physical activity domains, and percent of participants doing no physical activities related to vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activities (18).

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 26. Armonk, New York, United States, 2019) was used for data analysis. The method of cleaning and scoring GPAQ data has been described in detail elsewhere (18). There is no missing data. Statistical analysis for physical activity parameters was carried out for the complete study sample of subjects and the study sample subgroups after stratifying study participants based on their nationality. Categorical variables were analyzed by using the Chi-squared test and presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed by using the one-way ANOVA test and presented as means and standard deviations. The Tukey post hoc test was used to determine significant differences between subjects with different nationalities. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to detect the factors related to physical inactivity risk. All reported P-values were made based on two-tailed tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

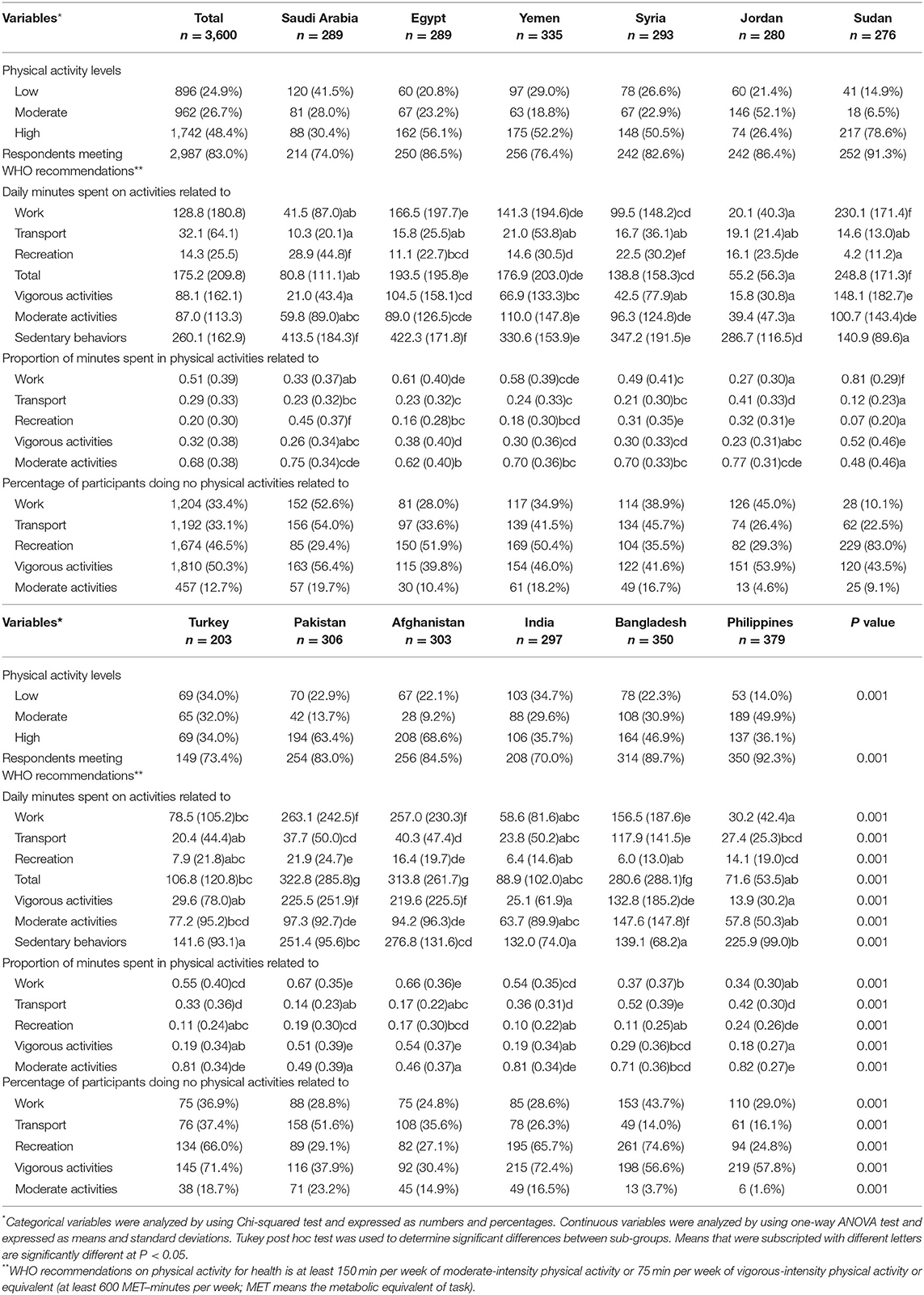

The sociodemographic characteristics and BMI of the study subjects are presented in Table 1. The current study included 3600 young men from Saudi Arabia and 11 Middle Eastern and Asian countries living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Physical activity characteristics of study subjects and subjects stratified by nationalities are presented in Table 2. Low physical activity level (physical inactivity) was reported among 24.9% of study subjects. By nationalities, the lowest and highest rates of low physical activity level were reported among subjects from the Philippines (14.0%) and Saudi Arabia (41.5%), respectively. Furthermore, moderate and high physical activity levels were reported among 26.7 and 48.4% of study subjects, respectively. A relatively high rate of study participants (83.0%) was found meeting WHO recommendations on physical activity for health.

Table 2. Physical activity characteristics of all study subjects (n = 3,600) and subjects stratified by nationalities.

The mean total daily minutes spent on physical activity by study subjects was 175.2 ± 209.8 min, whilst the mean daily minutes spent on physical activities related to work, transport, recreation, vigorous-intensity physical activities and moderate-intensity physical activities were 128.8 ± 180.8, 32.1 ± 64.1, 14.3 ± 25.5, 88.1 ± 162.1, and 87.0 ± 113.3 min, respectively. High variation was observed among participants from different countries regard daily minutes spent on physical activities related to work (20.1 min for Jordanian subjects and 263.1 min for Pakistani subjects), transport (10.3 min for Saudi subjects and 117.9 min for Bangladeshi subjects), recreation (4.2 min for Sudanese subjects and 28.9 min for Saudi subjects), vigorous-intensity physical activities (13.9 min for Filipino subjects and 225.5 min for Pakistani subjects), moderate-intensity physical activities (39.4 min for Jordanian subjects and 147.6 min for Bangladeshi subjects), and sedentary behaviors (132.0 min for Indian subjects and 422.3 min for Egyptian subjects).

The means of the proportion of weekly minutes spent in physical activities related to work, transport, and recreation from total physical activity were 0.51 ± 0.39, 0.29 ± 0.33, and 0.20 ± 0.30, respectively. Similarly, the means of the proportion of weekly minutes spent in vigorous-intensity physical activities and moderate-intensity physical activities from total physical activity were 0.32 ± 0.38 and 0.68 ± 0.38, respectively. Moreover, the percentages of participants who did not engage in any physical activity related to work, transport, recreation, vigorous-intensity physical activities, and moderate-intensity physical activities were 33.4, 33.1, 46.5, 50.3, and 12.7%, respectively.

The risk of physical inactivity among all subjects for sociodemographic characteristics and BMI is shown in Table 3. Compared with subjects from the Philippines, subject form several other countries had a significantly higher risk of being physically inactive, including Saudi Arabia [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 10.50, P = 0.001], Egypt (unadjusted OR = 1.61, P = 0.021), Yemen (adjusted OR = 3.09, P = 0.001), Syria (adjusted OR = 1.93, P = 0.003), Jordan (unadjusted OR = 1.68, P = 0.013), Turkey (adjusted OR = 5.08, P = 0.001), Pakistan (adjusted OR = 2.45, P = 0.001), Afghanistan (adjusted OR = 2.40, P = 0.001), India (adjusted OR = 5.19, P = 0.001), and Bangladesh (adjusted OR = 2.77, P = 0.001). Moreover, increasing age was significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity (adjusted OR = 1.05, P = 0.002). Similarly, longer residency period in Saudi Arabia was significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity (adjusted OR = 1.02, P = 0.001). Subjects those who live within a family household had a significantly higher risk of physical inactivity compared with those who live within non-family household (adjusted OR = 1.46, P = 0.001). Participants have at least a college degree had a significantly higher risk of physical inactivity compared with those with lower education level (adjusted OR = 1.59, P = 0.001). In the same fashion, participants having high monthly income (1,000 USD or more) had a significantly higher risk of physical inactivity compared with those who have low monthly income (unadjusted OR = 1.47, P = 0.001). Finally, Increasing BMI was significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity (adjusted OR = 1.04, P = 0.002).

Table 3. Risk of physical inactivity among all subjects (n = 3,600) for sociodemographic characteristics and body mass index.

This study provides a clear overview of physical activity levels among a multi-ethnic population of young men from Saudi Arabia and 11 Middle Eastern and Asian countries living in Saudi Arabia. According to the findings, around one-fourth of young men living in Saudi Arabia are physically inactive. Saudi Arabia has high physical inactivity prevalence rates at the global level (9). Regular physical activity is a challenging choice for Saudis due to several barriers, including lack of motivation, increased urbanization, heavy traffic, hot arid weather, cultural hurdles, lack of social support, and limited time and resources (9). Hence, the Saudi population's daily physical activity has decreased, leading to an increasing prevalence of physical inactivity, and consequently, the risk of chronic diseases (10). Physical inactivity was reported among 66.6% of the overall population in Saudi Arabia (60.1% for men and 72.9% for women), while only 16.8% and 16.6%of the population engaged in moderate and high levels of physical activity, respectively (19). A large population-based study conducted in Saudi Arabia found that the prevalence of physical inactivity among Saudi adults was 96.1% (93.9% among men and 98.1% among women) (20). Another study reported that 56.3% of male college students aged 17 to 25 years were physically inactive (21). A recent population-based study carried out also in Saudi Arabia reported that the rates of physical inactivity were 82.6% among Saudis aged 15 years or more (71.7% of Saudi males and 91.1% of Saudi females) and 86.1% of non-Saudi counterpart residents (83.9% of non-Saudi males and 92.0% of non-Saudi females) (22).

Saudi Arabia is one of the Middle East's fastest-growing high-income countries. Consequently, Saudi Arabia attracts workers from all over the world, mainly from the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. In 2013, expatriates made up 56.5% of the total workforce and 89% of the private sector employment in Saudi Arabia (14). Non-Saudi residents make up roughly 31% of the population of Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, males accounted for almost 70% of the non-Saudi population in Saudi Arabia (23). This is especially fascinating because the presence of migrants from diverse countries allows for a cross-sectional study of variations between their populations in various areas, such as lifestyle patterns and health markers.

The current study results revealed significant disparities in physical activity parameters among young men living in Saudi Arabia from various countries. Certain lifestyle characteristics, such as work type, transportation, leisure time activities, and the intensity and duration of physical activity, could explain these discrepancies (12, 24). Manual labor jobs such as working in construction, medical emergency, and firefighting are typically connected with higher physical activity levels than office labor jobs such as working in the education sector, banking and call answering services (25). For example, most Saudi young men work in office labor jobs. In contrast, most Pakistani young men living in Saudi Arabia work in manual labor jobs. Our results confirmed this observation as there is a notable difference in work-related physical activity among Saudi and Pakistani young men. Furthermore, common transportation ways can influence people's physical activity levels. Using automated vehicles for short distance travels, walking or riding a bicycle has been related to higher physical activity levels (26). In fact, most Bangladeshi young men living in Saudi Arabia commute short travels by bicycle. Contrarily, Saudi young men rely heavily on their automobiles for transportation, even short trips. Current study findings supported this observation as there is a variation in transport-related physical activity among Saudi and Bangladeshi young men. Cultural values, available free time, and available resources and relevant sites for completing workouts and engaging in recreational physical activities influence the leisure time physical activities of young men from various countries (27, 28). For example, young Saudi men were more engaged in recreational physical activities than young Sudanese men living in Saudi Arabia. In fact, examining these disparities in physical activity characteristics provides a chance to identify and implement appropriate measures to minimize physical inactivity in high-prevalence groups.

The monitoring of physical activity levels and associated risk factors for different community groups is an important aspect of health-promoting initiatives to combat physical inactivity (29). Our results revealed that several sociodemographic factors were significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity. The nationality of subjects was one of these factors, and this could be refed to cross-cultural variation among young men from different countries in occupations, common transportation ways and lifestyles including typical leisure time activities (13). Increasing age was also found to play a crucial role in physical inactivity. Young adults with ageing usually tend to do less physical activity and have more sedentary behaviors (30). This is consistent with previously reported results in Saudi Arabia (20, 22, 31). A longer residency period in Saudi Arabia was significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity, and this could be explained by urbanization and motorization commonly seen in Saudi Arabia and their effect on people lifestyles (9, 12). This result was in line with previous studies from Saudi Arabia (32, 33). The health of emigrants is thought to decline with the length of time they spend in a new host country. Cultural differences, interpersonal and economic changes, and lifestyle changes, including eating habits and physical activity associated with migration, may all contribute to health problems (34). Living within a family household was also significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity. Social gathering is a common feature of family structure in Saudi Arabia. Unfortunately, these gatherings focus mainly on sedentary behaviors such as eating meals and watching television (9). Higher education and higher income were significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity. In Saudi Arabia, educated and/or wealthy men typically have office labor jobs with sitting for long hours and using automobiles for transportation, which may be physically inactive (25). Finally, only marital status was not significantly associated with the risk of physical inactivity. A similar result was reported in a previous study (35).

Saudi Arabia has one of the highest rates of overweight and obesity in the world (10, 36). It is well-known that a lack of physical activity is an important variable that can lead to obesity (37). High overweight and obesity rates were seen in the Saudi population could be accused largely to highly prevalent physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles (38). Our results revealed that increasing BMI was significantly associated with a higher risk of physical inactivity among the study subjects. This result was consistent with previous studies from Saudi Arabia (20, 25, 31, 39, 40).

Notably, Saudi Arabia's population is considered a young population, with 72% of the population aged 34 or younger (23). In Saudi Arabia, young Saudi men aged 20 to 34 years made up around 30% of the male population, whereas young non-Saudi men aged 20 to 34 years made up around 38% of all non-Saudi male residents (23). Generally, young adults are particularly vulnerable to physical inactivity for several reasons, including time limitations, lack of accessible and suitable sports places, having other important priorities, lack of friends to encourage and lack of motivation (21, 41). Sedentary behaviors became widespread during this stage of life. These sedentary behaviors usually seen among young adults include computer use, television watching, reading, electronic gaming and smartphone use (42, 43). Unfortunately, physical inactivity and sedentary behaviors are connected with higher rates of health problems (7, 8). The significant incidence of physical inactivity among young men should raise alarm bells for health officials, especially when considering that most physically inactive young men maintained sedentary lifestyles (21). Health education for young adults to encourage them to engage in regular physical activities is critical for lifelong optimal health (44). This could be challenging due to a lack of motivation and time to engage in an active lifestyle (28). As a result, developing appropriate intervention programs and making physical activity counseling a priority in clinical practice is crucial (45). In Saudi Arabia, there were several initiatives aimed at encouraging physical activity. The majority of them were disjointed, short-term efforts that lacked a coordinating body and objective appraisals of their outcomes. There is a need for a national strategy that encourages active living while discouraging sedentary behavior, with input from all parties concerned (46).

There are certain limitations to this study that should be considered. One of the drawbacks of a cross-sectional design is that it cannot determine causality. Another limitation is that the core variables, physical activity parameters, are self-reported outcome measures prone to recall and social desirability biases. To effectively quantify the prevalence of physical activity, objective methods such as accelerometers are required. Finally, because our data came just from Riyadh, we may not generalize our findings across Saudi Arabia. However, the current study is unique because it provides useful information about physical activity levels and factors associated with physical inactivity in a multi-ethnic community of young men living in Saudi Arabia.

This study showed relatively high rates of physical inactivity among young men from Saudi Arabia and 11 Middle Eastern and Asian countries living in Saudi Arabia. The data revealed significant disparities in daily minutes spent on physical activities related to work, transport, recreation, vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activities and sedentary behaviors among study participants based on their nationalities. Participants' physical inactivity was significantly associated with nationality, age, residency period in Saudi Arabia, household type, education level, monthly income and BMI.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JA and NAlF: conceptualization. NAlK and JA: methodology. JA, NAlK, RA, and NAlF: software. JA and HA: validation. NAlF, NAls, and HA: formal analysis. RA: investigation and funding acquisition. NAlF: resources and supervision. NAlF and NAls: data curation. JA and RA: writing—original draft preparation. NAls and HA: writing—review and editing. JA: visualization and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R34), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

BMI, body mass index; WHO, World Health Organization; GPAQ, Global Physical Activity Questionnaire; OR, odds ratio.

1. WHO. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity For Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010).

2. Warburton DE, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr Opin Cardiol. (2017) 32:541–56. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437

3. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Smith L, Rosenbaum S, Schuch F, Firth J. Physical activity and mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:873. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30343-2

4. An HY, Chen W, Wang CW, Yang HF, Huang WT, Fan SY. The relationships between physical activity and life satisfaction and happiness among young, middle-aged, and older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4817. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134817

5. WHO. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People For a Healthier World. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

6. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1· 9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. (2018) 6:e1077–86. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7

7. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. (2012) 380:219–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

8. Booth FW, Roberts CK, Thyfault JP, Ruegsegger GN, Toedebusch RG. Role of inactivity in chronic diseases: evolutionary insight and pathophysiological mechanisms. Physiol Rev. (2017) 97:1351–402. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2016

9. Al-Hazzaa HM. Physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia revisited: a systematic review of inactivity prevalence and perceived barriers to active living. Int J Health Sci. (2018) 12:50. doi: 10.2196/preprints.9883

10. DeNicola E, Aburizaiza OS, Siddique A, Khwaja H, Carpenter DO. Obesity and public health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Rev Environ Health. (2015) 30:191–205. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2015-0008

11. ALFaris NA, Al-Tamimi JZ, Al-Jobair MO, Al-Shwaiyat NM. Trends of fast food consumption among adolescent and young adult Saudi girls living in Riyadh. Food Nutr Res. (2015) 59:26488. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v59.26488

12. AlQuaiz AM, Kazi A, Almigbal TH, AlHazmi AM, Qureshi R, AlHabeeb KM. Factors Associated with an Unhealthy Lifestyle among Adults in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare. (2021) 9:221. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020221

13. WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization (2014).

14. De Bel-Air F. Demography, Migration Labour Market in Saudi Arabia. Gulf Labour Markets Migration. European University Institute (EUI) Gulf Research Center (GRC) (2014). GLMM - EN - No. 1/2014. Available online at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/32151/GLMM%20ExpNote_01-2014.pdf (accessed December 16, 2021).

16. Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the world health organization global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health. (2006) 14:66–70. doi: 10.1007/s10389-006-0024-x

17. Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Activity Health. (2009) 6:790–804. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.6.790

18. WHO. Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) Analysis Guide. (2012). Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/resources/GPAQ_Analysis_Guide.pdf (accessed December 16, 2021).

19. Al-Zalabani AH, Al-Hamdan NA, Saeed AA. The prevalence of physical activity and its socioeconomic correlates in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional population-based national survey. J Taibah Univ Medical Sci. (2015) 10:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2014.11.001

20. Al-Nozha MM, Al-Hazzaa HM, Arafah MR, Al-Khadra A, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA, et al. Prevalence of physical activity and inactivity among Saudis aged 30-70 years. Saudi Med J. (2007) 28:559–68.

21. Awadalla NJ, Aboelyazed AE, Hassanein MA, Khalil SN, Aftab R, Gaballa II, et al. Assessment of physical inactivity and perceived barriers to physical activity among health college students, south-western Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. (2014) 20:596–604. doi: 10.26719/2014.20.10.596

22. Alqahtani BA, Alenazi AM, Alhowimel AS, Elnaggar RK. The descriptive pattern of physical activity in Saudi Arabia: analysis of national survey data. Int Health. (2021) 13:232–9. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihaa027

23. General Authority of Statistics of Saudi Arabia. Population by Gender, Age Groups and Nationality (Saudi/Non-Saudi), The Fifth Saudi census. (2010). Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/ar-census2010-dtl-result_2_1.pdf (accessed December 16, 2021).

24. Haase A, Steptoe A, Sallis JF, Wardle J. Leisure-time physical activity in university students from 23 countries: associations with health beliefs, risk awareness, and national economic development. Preventive medicine. (2004) 39:182–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.028

25. Almuzaini Y, Jradi H. Correlates and levels of physical activity and body mass index among Saudi men working in office-based jobs. J Community Health. (2019) 44:815–21. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00639-4

26. Sallis JF, Frank LD, Saelens BE, Kraft MK. Active transportation and physical activity: opportunities for collaboration on transportation and public health research. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract. (2004) 38:249–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2003.11.003

27. Amin TT, Al Khoudair AS, Al Harbi MA, Al Ali AR. Leisure time physical activity in Saudi Arabia: prevalence, pattern and determining factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2012) 13:351–60. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.1.351

28. Ashton LM, Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME, Morgan PJ, Collins CE. Motivators and barriers to engaging in healthy eating and physical activity: a cross-sectional survey in young adult men. Am J Mens Health. (2017) 11:330–43. doi: 10.1177/1557988316680936

29. WHO. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

30. Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2000) 32:1601–9. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013

31. Mahmoud WSED, Ahmed AS, Elnaggar RK. Physical activity in overweight and obese adults in Al-kharj, Saudi Arabia. Eur J Sci Res. (2016) 137:236–45.

32. Amin TT, Al Sultan AI, Mostafa OA, Darwish AA, Al-Naboli MR. Profile of non-communicable disease risk factors among employees at a Saudi university. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2014) 15:7897–907. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.18.7897

33. Alzeidan RA, Rabiee-Khan F, Mandil AA, Hersi AS, Ullah AA. Changes in dietary habits and physical activity and status of metabolic syndrome among expatriates in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. (2017) 23:836–44. doi: 10.26719/2017.23.12.836

34. Lassetter JH, Callister LC. The impact of migration on the health of voluntary migrants in western societies: a review of the literature. J Transcult Nurs. (2009) 20:93–104. doi: 10.1177/1043659608325841

35. Hull EE, Rofey DL, Robertson RJ, Nagle EF, Otto AD, Aaron DJ. Influence of marriage and parenthood on physical activity: a 2-year prospective analysis. J Phys Activity Health. (2010) 7:577–83. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.5.577

36. Al-Rethaiaa AS, Fahmy AEA, Al-Shwaiyat NM. Obesity and eating habits among college students in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Nutr J. (2010) 9:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-39

37. Chin SH, Kahathuduwa CN, Binks M. Physical activity and obesity: what we know and what we need to know. Obesity Reviews. (2016) 17:1226–44. doi: 10.1111/obr.12460

38. Memish ZA, El Bcheraoui C, Tuffaha M, Robinson M, Daoud F, Jaber S, et al. Obesity and associated factors—Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. (2014) 11:40236. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140236

39. Assiri HM, Almazarigeh SD, Moshibah AM, Al-Shahrani SF, Al-Qarni NS, Hadadi AM. Risk factors for physical inactivity in Saudi Arabia. Al-Azhar Assiut Med J. (2015) 13:132–8.

40. Jadou NS, AlFaraj ZM, Abdulhameed S, Alahmad SNAA, Saleh M, Alonazi AMA, et al. Prevalence of obesity and its relation to physical activity in the Saudi population. IJMDC. (2019) 3:450–456. doi: 10.24911/IJMDC.51-1547147458

41. Deyab AA, Abdelrahim SA, Almazyad A, Alsakran A, Almotiri R, Aldossari F. Physical inactivity among University Students, Saudi Arabia. IJCRMS. (2019) 5:1–7. doi: 10.22192/ijcrms.2019.05.09.001

42. Alshehri AG, Mohamed AMAS. The relationship between electronic gaming and health, social relationships, and physical activity among males in Saudi Arabia. Am J Mens Health. (2019) 13:1557988319873512. doi: 10.1177/1557988319873512

43. Al-Hanawi MK, Chirwa GC, Pemba LA, Qattan AM. Does prolonged television viewing affect body mass index? a case of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0228321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228321

44. Alahmed Z, Lobelo F. Physical activity promotion in Saudi Arabia: a critical role for clinicians and the health care system. J Epidemiol Glob Health. (2018) 7:S7–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.10.005

45. Berra K, Rippe J, Manson JE. Making physical activity counseling a priority in clinical practice: the time for action is now. JAMA. (2015) 314:2617–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16244

Keywords: physical activity, physical inactivity, body mass index, young men, multi-ethnic, Saudi Arabia

Citation: AlTamimi JZ, Alagal RI, AlKehayez NM, Alshwaiyat NM, Al-Jamal HA and AlFaris NA (2022) Physical Activity Levels of a Multi-Ethnic Population of Young Men Living in Saudi Arabia and Factors Associated With Physical Inactivity. Front. Public Health 9:734968. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.734968

Received: 01 July 2021; Accepted: 27 December 2021;

Published: 02 February 2022.

Edited by:

Samera Qureshi, Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), NorwayReviewed by:

Palash Chandra Banik, Bangladesh University of Health Sciences, BangladeshCopyright © 2022 AlTamimi, Alagal, AlKehayez, Alshwaiyat, Al-Jamal and AlFaris. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nora A. AlFaris, bmFhbGZhcmlzQHBudS5lZHUuc2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.