95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 23 December 2021

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.732061

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Public Health Policy: 2021 View all 11 articles

Objectives: Breastfeeding support rooms are low-cost interventions that may prolong breastfeeding and improve work performance. Thus, we sought to understand the experiences and perceptions of working women who use breastfeeding support rooms and the potential contribution to sustainable development goals.

Methods: Descriptive and exploratory research was conducted through convenience sampling of women working in companies with breastfeeding support rooms in the state of Paraná, Brazil. A semi-structured questionnaire was applied through interviews and online self-completion.

Results: Fifty-three women between 28 and 41 years old participated in the study. In addition, 88.7% had graduated from college, and 96% were married. From the women's experiences and perceptions, we identified that breastfeeding support rooms contribute to prolonged breastfeeding, improve physical and emotional well-being, allow women to exercise their professional activities comfortably, contribute to women's professional appreciation for the excellent relationship between employees and employers.

Conclusion: In this novel study, we demonstrate how, from a female point of view, breastfeeding support rooms can contribute to 8 of the 17 sustainable development goals and should therefore be encouraged and promoted.

Raising breastfeeding indicators is an international priority (1). The proven benefits to maternal and child health are indisputable, as the practice of breastfeeding affects the lives and health of women and children and contributes to the development of human capital (2, 3). Moreover, the benefits extend to low, middle, and high-income countries (3).

The relationship between the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding and its contribution to the achievement of several Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) is already established, although breastfeeding is not explicitly embedded in the SDG (2, 3). The SDG corresponds to 17 global goals defined in 2015 at the United Nations General Assembly, under A/RES/70/1: Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (4, 5).

Lack of breastfeeding support, especially in the workplace, discourages women from maintaining breastfeeding (3, 6). Women have been increasingly joining the workforce and the period after the return from maternity leave represents one of the main challenges for continued breastfeeding (7, 8).

International measures to support breastfeeding in the workplace advise that countries respect the minimum standards set by the International Labor Organization (ILO) in conventions No. 183 and No. 191 to ensure maternity and work protection, including requiring maternity leave of at least 14 weeks and breastfeeding breaks during the workday (9).

In Brazil, the Working Women who Breastfeed (Mulher Trabalhadora que Amamenta–MTA) action was created in 2010 by the Ministry of Health to bring together strategies to support breastfeeding at work. Later, in 2015, MTA was added to the Breastfeeding and Complementary Foods axis of the National Policy on Integral Attention to the Child's Health (Pnaisc) (10). MTA has three axes: (1) incentive to the optional extension of maternity leave, which is currently 120 days, to 180 days, (2) the right to daycare or a daycare voucher, which is mandatory for all companies with more than 30 women above the age of 16, and (3) the right to two breastfeeding breaks, which are mandatory for all companies until the child is 6 months old, and the incentive to the implement breastfeeding support rooms (BSRs), which is optional for all companies.

The BSRs and breaks to breastfeed or pump breast milk during the workday are low-cost measures that can reduce absenteeism, improve employee performance, commitment, and retention, and reduce barriers for employees who breastfeed (3).

In addition, BSRs and breastfeeding breaks in the workplace can increase a woman's intention to continue breastfeeding after maternity leave (11) and may increase the chances of breastfeeding for 6 months by 25% (3, 12). As a result, BSRs lead to an increase in the rates of both exclusive and continued breastfeeding (13–16) and can contribute to achieving the global goals set by the World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund for 2030, which establish the global target of exclusive breastfeeding for 70% of infants <6 months of age, 80% of infants <12 months old, and 60% of infants under 2 years old (1).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies investigating BSRs from a user's point of view, nor how BSRs contribute to achieving goals established by the SDG for 2030. Thus, this study aims to understand the perceptions and experiences of female employees who use BSRs and relate these perceptions to the potential achievement of the international goals set for 2030 to raise breastfeeding rates and achieve the SDG. This study is part of doctoral research that evaluated BSRs in southern Brazil.

This is exploratory, descriptive, and qualitative research. It was conducted between December 2019 and December 2020 but interrupted for 3 months and adjusted due to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The study selected participants via convenience sampling, usual for pilot studies, from a population of 130 female employees who used BSRs after returning to work. In addition, we selected female employees from eight companies in the state of Paraná, in southern Brazil, one of the most developed regions of the country, that implemented BSRs and whose BSR was certified by the Ministry of Health until December 2017, which correspond to 88.9% of companies with active BSR in the state.

All women on maternity leave in the year before the beginning of the study and who used the BSR in their companies were eligible for the study. However, we excluded female employees from companies whose BSR had not been used in the 6 months before the start of the study.

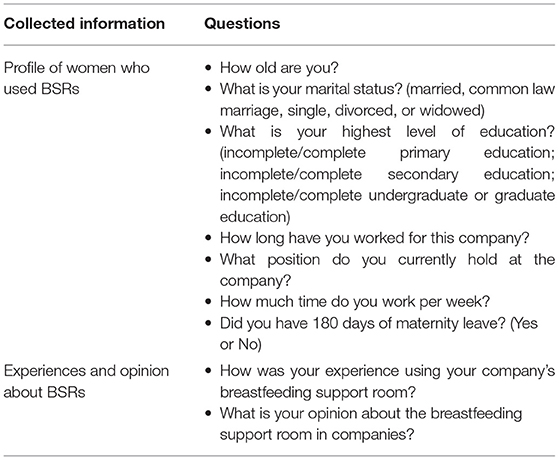

The data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire divided into two parts: (1) the profile of the women who used the BSR: time of employment at the company, position held, weekly working hours; marital status (married, common law, single, divorced, or widowed), education (incomplete/complete primary education, incomplete/complete secondary education, incomplete/complete undergraduate, or graduate education), age, and whether they had a 180-day maternity leave (yes/no), and (2) open questions about their experiences with BSRs: what it was like to use them and their opinion of BSRs in the companies, as seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Information collected from women who used Breastfeeding Support Rooms (N = 53) Paraná, Brazil, 2019–2020.

The study began with the application of the questionnaire through in-person interviews conducted within company BSRs. However, at the beginning of the data collection stage, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we decided to interrupt the research and reflect on alternative approaches. Therefore, we requested the Ethics Committee to include data collected through online self-completion questionnaires (Google Forms), including a consent form. The companies participating in the study sent invitations to their female employees, both for the interviews, announcing the date and time that the researcher (first author) would be conducting the interviews and the online self-completion questionnaire submitted within 60 days. The in-person interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed word-for-word. The answers obtained through the online questionnaire were used precisely as they were recorded in the answer sheet.

The Statistic 10.0 (StatsoftR) program was used for the sample description, and the variables studied were expressed in absolute and relative frequencies.

Qualitative analysis was carried out by the thematic categorical content analysis, following three steps (17): (1) material organization, (2) coding, and (3) result interpretation. From the categories or themes found, we deductively sought to identify their relationship with the SDG. The data were analyzed using the Atlas.ti version 9.0 software (18), which contributed to the data management.

For this study, the criteria proposed by the Journal Article Reporting Standards [American Psychological Association (19)] for qualitative research were respected.

The study included 53 women, 40.8% of BSR users in Paraná. Of these, 8 (15%) female workers participated by semi-structured interview, and 45 (85%) answered an online self-completion questionnaire.

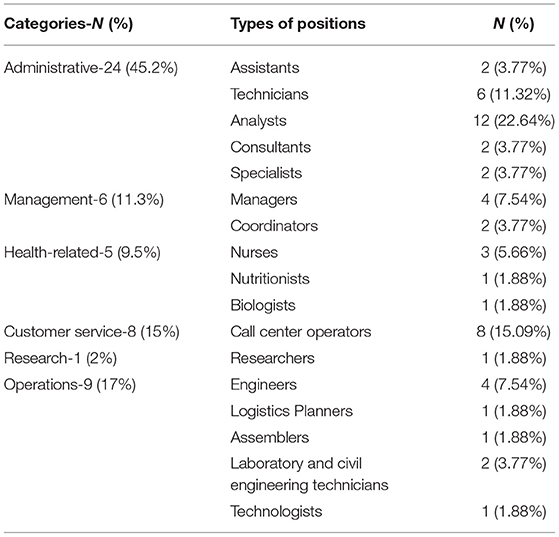

All-female employees included in this study were between 28 and 41 years old. Thirty (72%) women were between 31 and 40 years old, 47 (88.7%) had graduated college, 51 (96%) were married or living in a common-law marriage. Eleven (21%) women have worked for their company from 1 to 5 years and 42 (79%) for 6 years or more. Most of the participants, 43 (81%), had a 40–44 h weekly workday. The types of positions held by the female employees are available in Table 2. In addition, all women (100%) had 180 days of maternity leave.

Table 2. Positions occupied by women who used breastfeeding support rooms (n = 53), Brazil, 2019–2020.

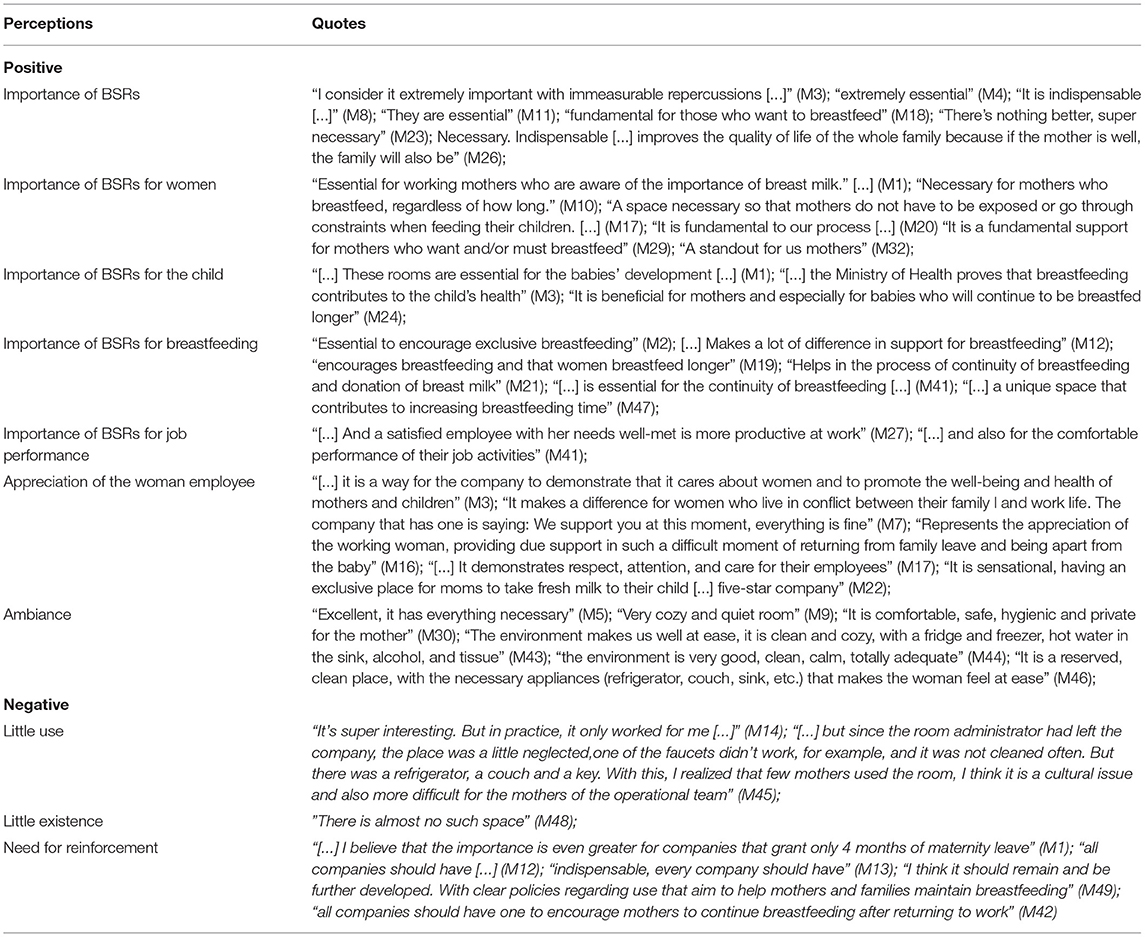

We consider that all the experiences with BSRs were positive. From the participating reports, we identified that the experience categories are related to the fact that the BSRs: (1) allows for breastfeeding continuity, (2) contributes to the bonding and well-being of the child, (3) provides comfort and emotional well-being for the woman, (4) provides comfort and physical well-being for the woman, (5) is related to the adequate, quiet place with all the necessary infrastructure for breastfeeding, and (6) allows women to donate breast milk to a milk bank, as seen in Table 3.

However, we identified some difficulties regarding room usage, although they were not indicated as negative by women, such as: (1) distance from the rooms to the workplace, and (2) need to stop using the rooms due to the child's age (Table 3).

The female participants had positive opinions about the BSRs about (1) the importance of the rooms for different purposes, (2) the respect of working women, and (3) the atmosphere (physical structure and equipment). On the other hand, the negative perceptions are related to (1) little use, (2) the small amount of BSRs implemented by companies, and (3) the need to reinforce this action. The thematic analysis is available in Table 4.

Table 4. Perceptions of female employees about breastfeeding support rooms (n = 53), Brazil, 2019–2020.

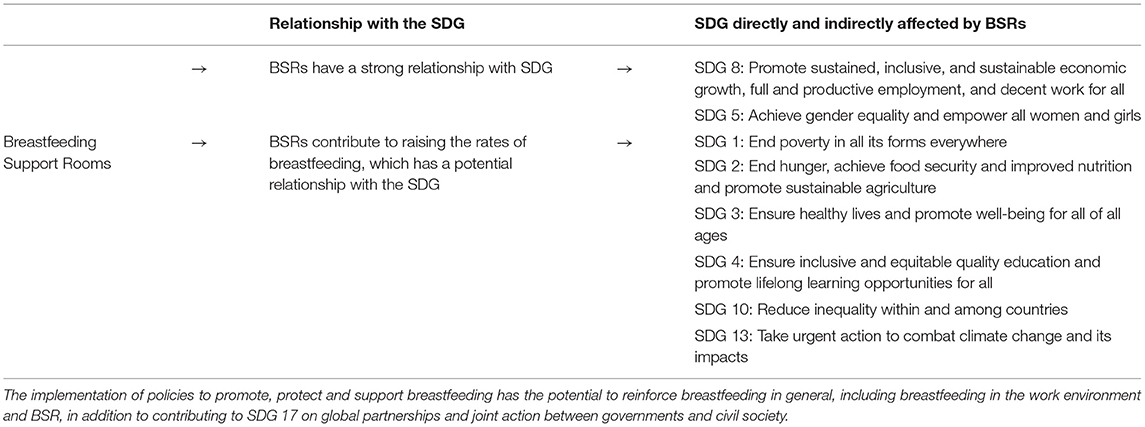

From the codings and themes resulting from the experiences using the BSRs and the opinions of women who use BSRs, we were able to establish the positive relationship between the BSRs and the international goals to raise breastfeeding indicators worldwide, and to several of the SDG.

We observe a strong relationship between BSRs and SDG 8, particularly regarding decent work and economic growth, as breastfeeding in the workplace can promote decent work, women's productivity and contribute to economic growth.

In Table 3, some reports show that BSRs provide comfort, physical, and emotional well-being for women to perform their activities, with comments such as “It was wonderful, I felt welcomed, safe, cared for, very calm” (M23); “[…] A major benefit was being able to pump milk and avoid mastitis, which happened when I had my first daughter, precisely because I had no way to pump milk.” (M15); and “[…] The room was essential. […] Also, to relieve any discomfort throughout the day.” (M29). In Table 4, we can see how the BSR contributes to a good relationship between employees and employers. Once women recognize the importance of the BSRs for the full realization of their professional activities, they realize that BSRs contribute to the appreciation of the women in the workforce since they feel happy and valued professionally: “[…] And a satisfied employee with her needs well-met is more productive at work” (M27) and “[…] and also for performing their job activities smoothly” (M41).

In addition, the discourse surrounding women points to an appreciation of the differential that the company provides for them. Women recognize and value a company that meets their needs as a woman, as a mother, and as a professional: “[…] it is a way for the company to demonstrate that it cares about women and to promote the well-being and health of mothers and children” (M3), and “It makes a difference for women who live in a conflict between their family and work life. The company has a saying: We support you at this moment, everything is fine” (M7).

We observed a potential relationship between BSR availability in work environments and the achievement of SDG 5 concerning gender equality. As observed in Tables 3, 4, BSRs contribute to women having the opportunity to perform their professional activities just as well as men, without physical or emotional stress, feeling valued and recognized professionally.

We can also see indirect relationships between BSRs and the achievement of six other SDGs from the increase in breastfeeding rates, which positively impact the achievement of the following SDG: (1) end poverty (SDG 1): breastfeeding contributes to higher financial income for breastfed adults, (2) zero hunger (SDG 2): breastfeeding reduces hunger and malnutrition, promoting total child growth, and development in the early years of life, (3) good health and well-being (SDG 3): breastfeeding improves the physical and mental health, and well-being of mothers and children, (4) quality education (SDG 4): breastfeeding contributes to an increase in intelligence quotient. Breastfed children for longer participate in more educational activities, (5) reducing inequalities (SDG 10): breastfeeding provides the best start in life. With the increase in breastfeeding rates, there is a decrease in infant morbidity and mortality, an increase in physical and emotional well-being, in income when adult, thus reducing social inequalities throughout generations, (6) climate action (SDG 13): breastfeeding is sustainable and does not harm the environment, unlike baby formulas that can contribute to the greenhouse effect and waste generation, and should only be used when necessary. This relationship can be seen in Table 5.

Table 5. Relationship between Breastfeeding Support Rooms and their contribution to achieving Sustainable Development Goals, Brazil, 2019–2020.

From the reports of formal female workers, we identified how their experiences using BSRs, their perceptions and opinions on the BSR strategy, and the support for breastfeeding at work as a result of implementing BSRs, can contribute directly to SDG 8 and SDG 5 and consequently lead to six other SDGs as the time women continue breastfeeding increases. Although there are studies that investigate BSRs, we could not find studies with this focus. Our sample corresponded to a little more than 40% of active BSR users in the state of Paraná, which we consider an acceptable standard for studies with self-completion questionnaires.

Most women were middle-aged, between 31 and 40 years old, married or living in a common-law marriage. Regarding the positions occupied by women at work, we observed that most were placed in administrative functions. According to Dagher et al. (7), women who work in an office have a higher chance of initiating breastfeeding. In addition, research shows that the sociodemographic conditions of women in southern Brazil are favorable for exclusive breastfeeding but that it is a challenge to keep breastfeeding for more than 12 months (20).

Most of the women in our study had graduated college, worked up to 8 h a day, and were encouraged by the company and their superiors to take breaks to pump breast milk. These findings corroborate with Tsai (21) in a study conducted in Taiwan with 715 female employees.

We know that the high level of education can be a favorable factor for breastfeeding [Tsai (20, 21)], thus contributing to women having more positive perceptions about the actions that contribute to the maintenance of breastfeeding, including the BSRs. We emphasize, however, that only 6 (11.3%) of the women held higher management positions, and it was unanimous for all users, even female workers, and assistants, to be satisfied with being able to use SAA in the workplace. Furthermore, in our study, 100% of the women had a late return to work after the 180-day maternity leave, and it is common for workers to extend this period with 30 vacation days, resulting in a return to work of around 7 months after the baby is already on complementary feeding. In addition, most women also had the privilege of using BSRs even after the time established in the labor legislation of breaks up to 6 months. We believe that this was due to employers becoming more aware of the importance of breastfeeding.

The Citizen Company (Empresa Cidadã) program, instituted in 2008 by Law 11.770 (22), is aimed at the optional extension of maternity leave from 120 to 180 days through the concession of a tax incentive. The extension of maternity leave is an achievement that has ensured progress for public policies in support of early childhood in Brazil. Six-month maternity leave is associated with an increased prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (8). All the companies participating in this study have adopted a 180-day maternity leave, and most have also adopted a 20-day paternity leave.

Most of the women had worked for a long time in the company. From their accounts, as seen in Table 4, we found that employees perceive that the company, upon implementing BSRs, values their work and provides conditions for a good work performance, contributing strongly to the achievement of SDG 8 and 5. This relationship between BSRs and SDG 8 and 5 was more specifically about promoting decent work, allowing women to find physical and emotional comfort that enables them to be more relaxed, and willing to perform their professional activities on equal grounds.

We noticed that the BSRs contribute to the appreciation of female employees. For example, women reported feeling happy and valued professionally for having rooms available since they feel that the company supports them in their needs. In addition, we found that female employees recognize the company's advantage, which is related to an increase in satisfaction and contentment concerning the company they work for, as observed in some reports in Table 4.

This finding corroborates the assertion of Rollins et al. (3) that BSRs can reduce absenteeism, improve work performance, engagement, and workforce retention. We understand that BSRs have a great potential to reduce barriers to continued breastfeeding among working women, promote decent work, which concerns SDG 8, and are a low-cost investment that employers could easily implement.

By allowing women to alleviate their physical discomfort during the workday and find emotional well-being and comfort, the relationship between BSRs and gender equality merges with the relationship between BSRs and decent work. When women can use the BSRs, the environment is considered safe and comfortable. In addition, they have emotional comfort because the woman knows that her child will safely drink her milk stored in an appropriate place during her professional activities and avoid using baby formula. Therefore, women can dedicate themselves to their professional activities more efficiently, allowing for equal working conditions as men, who do not have such concerns. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies support our findings regarding how BSRs could contribute to gender equality related to SDG 5, seeing as this field is still little explored. Therefore, we highlight the need for further studies on this topic.

In Tables 3, 4, we can see that women relate the importance of the SAA with the maintenance and continuity of breastfeeding. Moreover, several authors corroborate the relationship between BSRs and increased breastfeeding rates (3, 12–16).

We consider that increasing breastfeeding rates has the potential to positively impact at least six of the SDGs, like Victora et al. (2), who relate the promotion of breastfeeding to several SDGs.

There is a relationship between breastfeeding and reducing poverty and increasing human capital, which, in turn, can also reduce social inequalities. According to Victora et al. (23), breastfeeding improves human capital and significantly affects adult education and income. Breastfed children have better intellectual development for a more extended period (average increase of 3 IQ points). As a result, they can show positive results in school performance and a higher income in the long term. These findings relate to SDGs 1, 4, and 10.

The relationship between breastfeeding, maternal, and child health, included in SDG 3, is supported by several authors. Breastfeeding benefits both children's (2, 3, 23, 24) and women's health (2, 3, 25) and strengthens the emotional bond between the mother and baby. Breastfeeding reduces infant deaths (2, 6, 24, 26, 27) and can prevent 13% of worldwide deaths in children under 5 years of age (6, 26). Extending breastfeeding to an almost universal level could prevent 823,000 annual deaths of children under 5 and 20,000 annual deaths from breast cancer (2).

Breastfeeding ensures food and nutritional security and promotes total growth and development for children. Breastfeeding is a child's first protection against hunger, malnutrition, illnesses, and is also their most lasting investment in physical, cognitive, and social aspects (24) related to SDG 2.

According to the women, BSRs are essential because they can avoid using baby formulas, as seen in Tables 3, 4. This fact can be related to the achievement of SDG 13, which concerns reducing the impacts of climate change. In addition, breastfeeding is sustainable and does not harm the environment, unlike baby formulas, which contribute to the greenhouse effect and waste generation, and thus, should only be used when necessary. According to Rollins et al. (3), breastfeeding has economic and environmental benefits.

Managers have a critical role in the success of breastfeeding for working women (28). We know that lack of breastfeeding support in the workplace and inconvenient breastfeeding conditions discourage women from maintaining the practice (6, 21, 29, 30).

In our study, most women reported that they receive support and encouragement from their companies. However, from the experience of two BSRs users, one of the barriers when using the rooms is related to the fact that they would have liked to have used the BSRs longer. One of these participants was discouraged from using the BSR after her child turned 8 months. This fact indicates that despite the government's efforts to encourage BSRs, this strategy can be improved.

Through Convention 183, the ILO proposes measures to protect maternity and breastfeeding in the workplace, assigning countries the responsibility to institute a period for breastfeeding breaks, the reduction of daily working hours, the duration of breastfeeding breaks, among others, as noted in items 1 and 2 of article 10 (31).

According to Rollins et al. (3), 130 countries have paid breastfeeding breaks, seven countries have unpaid breaks, and 45 countries do not have a policy for breastfeeding at work. In Brazil, the right to a breastfeeding break date back to the 1940s and is included in the labor legislation. Article 396 of the Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT) determines that a woman should have two 30-min breastfeeding breaks during the workday until the child is 6 months old. The law also incorporates an extension to the 6 months at the discretion of competent authorities, depending on the child's health (32).

These results reinforce the importance of an update to Brazilian labor laws concerning an extension of breaks to breastfeed or pump milk during the workday, either if breastfeeding continues or at least until the child is 2 years old, which is the recommended threshold for breastfeeding.

This right to breastfeed children up to 2 years of age must be established by law and available to all women, regardless of the manager's goodwill. The institutionalization of the right to breastfeed at work for the first 2 years of the child's life would also contribute to achieving the international breastfeeding goals for 2030, which are 80% breastfeeding by age one and 60% by age two (1). To that end, governments, donors, and civilians must commit and invest in the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding (3).

There are some limitations to our study that need to be pointed out. First, we focused only on one state in Brazil, which has 76.2% of SAA in the southern region of the country and 8% of the total 200 BSRs certified in Brazil by 2017. Brazil is a very diverse country; thus, it would be beneficial to use complementary studies to verify our findings in other regions. Second, our study involved companies that adhered to other support strategies for working women, such as extending maternity and paternity leave, which may have influenced the positive perception of women about the Breastfeeding Support Rooms. Finally, the use of the online questionnaire instead of in-depth interviews may have made it challenging to capture women's perceptions somehow.

However, despite these limitations, this is the first study in Brazil to gather data on women's experience using BSRs and their perception about it. This is also the first study that points to the great potential relationship between BSRs and the achieving SDG 5 and 8 by promoting decent work, professional appreciation, comfort, and physical and emotional well-being, all factors that contribute to work productivity and economic growth besides impacting other SDGs by increasing breastfeeding rates.

Our findings conclude that the BSR is seen as an important and cheap strategy for female employees. Therefore, countries should invest to promote breastfeeding in the workplace through BSRs because they contribute directly and indirectly to achieving the SDG.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are in Portuguese and will be provided by the authors, without reservation, upon a request sent via email to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Department of the Federal University of Paraná, under Certificate of Presentation of Ethical Appreciation (CAAE) number 65401917.5.3004.5225. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

CBS collected, analysed, and interpreted the data and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. SIV and RPGVCS interpreted the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study and approved the final version to be published.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to thank the coordination of the Technical Wing of Child Health and Breastfeeding of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Health Care for Children and Adolescents Division of the State Secretary of health in Paraná, and all women and institutions involved in this research.

1. World Health Organization, United Nations Children's Fund? Global Breastfeeding Scorecard, 2019: Increasing Commitment to Breastfeeding Through Funding and Improved Policies and Programmes. (2019). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326049 (accessed April 27, 2021).

2. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. (2016). 387:75–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

3. Rollins NC, Lutter CK, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. (2016). 387:491–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2

4. United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online at: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed April 27, 2021).

5. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, Secretaria Especial de Articulação Social. Objetivos para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável: Indicadores Brasileiros para os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável. (2021). Available online at: https://odsbrasil.gov.br/home/videos (accessed April 27, 2021).

6. Bai YK, Dinour LM, Pope GA. Determinants of the intention to pump breast milk on a University campus. J Midwifery Womens Health. (2016). 61:563–70. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12488

7. Dagher RK, McGovern PM, Schold JD, Randall XJ. Determinants of breastfeeding initiation and cessation among employed mothers: a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2016) 16:194. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0965-1

8. Monteiro FR, Buccini GS, Venâncio SI, Costa TH. Influence of maternity leave on exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatria. (2017) 93:475–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.11.016

9. Addati L, Cassirer N, Gilchrist K. Maternity Paternity at Work: Law Practice Across the World International Labour Office. Geneva: ILO (2014). p. 204. Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_242615.pdf (accessed April 27, 2021).

10. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria n° 1.130de agosto de 2015. Institui a política nacional de atenção integral à saúde da criança (PNAISC) no âmbito do sistema único de saúde (SUS). (2015). Available online at: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2015/prt1130_05_08_2015.html (accessed April 27, 2021).

11. Tsai SY. Employee perception of breastfeeding-friendly support and benefits of breastfeeding as a predictor of intention to use breast-pumping breaks after returning to work among employed mothers. Breastfeed Med. (2014) 9:16–23. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2013.0082

12. Dabritz HA, Hinton BG, Babb J. Evaluation of lactation support in the workplace or school environment on 6-month breastfeeding outcomes in Yolo County, California. J Hum Lactation. (2009) 25:182–93. doi: 10.1177/0890334408328222

13. Basrowi RW, Sulistomo AB, Adi NP, Vandenplas Y. Benefits of a dedicated breastfeeding facility and support program for exclusive breastfeeding among workers in Indonesia. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. (2015) 18:94–9. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2015.18.2.94

14. Lee CC, Chiou ST, Chen LC, Chien LY. Breastfeeding-friendly environmental factors and continuing breastfeeding until 6 months postpartum: 2008-2011 national surveys in Taiwan. Birth. (2015) 42:42–248. doi: 10.1111/birt.12170

15. Kozhimannil KB, Jou J, Gjerdingen DK, McGovern PM. Access to workplace accommodations to support breastfeeding after passage of the affordable care. Act Womens Health Issues. (2016) 26:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.08.002

16. Nardi AL, Von Frankenberg AD, Franzosi OS, Espírito-Santo LC. Impacto dos aspectos institucionais no aleitamento materno em mulheres trabalhadoras: uma revisão sistemática. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. (2020) 25:1445–62. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232020254.20382018

19. American Psychological Association. Qualitative Mixed Methods Research. (2018). Available online at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/highlights/qualitative (accessed April 27, 2021).

20. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Estudo Nacional de Alimentação e Nutrição Infantil ENANI-2019: Resultados preliminares – Indicadores de aleitamento materno no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ (2020). p. 9. Available online at: https://enani.nutricao.ufrj.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Relatorio-preliminar-AM-Site.pdf (accessed April 27, 2021).

21. Tsai SY. Impact of a breastfeeding-friendly workplace on an employed mother's intention to continue breastfeeding after returning to work. Breastfeeding Med. (2013) 8:210–6. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2012.0119

22. Ministério da Economia. Receita Federal. Programa Empresa Cidadã. (2021). Available online at: https://receita.economia.gov.br/orientacao/tributaria/isencoes/programa-empresa-cidada/orientacoes (accessed April 27, 2021).

23. Victora CG, Horta BL, Mola CL, Quevedo L, Pinheiro RT, Gigante DP, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet. (2015) 3:e199–205. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70002-1

24. Hansen, K. Breastfeeding: a smart investment in people and in economies. Lancet. (2016) 387:416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00012-X

25. Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, Taneja S, Bhandari N, Rollins N, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. (2015) 104:96–113. doi: 10.1111/apa.13102

26. World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical [Students and Allied Health Professionals]. Geneva: World Health Organization (2009). Available online at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9789241597494/en/ (accessed April 27, 2021).

27. Sankar, MJ, Sinha, B, Chowdhury, R, Bhandari, N, Taneja, S, Martines, J, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. (2015) 104:3–13. doi: 10.1111/apa.13147

28. Mills SP. Workplace lactation programs: a critical element for breastfeeding mothers' success. AAOHN J. (2009) 57:227–31. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20090518-02

29. Chen YC, Wu YC, Chie WC. Effects of work-related factors on the breastfeeding behavior of working mothers in a Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. (2006) 21:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-160

30. Bai YK, Gaits SI, Wunderlich SM. Workplace lactation support by New Jersey employers following US Reasonable Break Time for Nursing Mothers law. J Human Lactat. (2015) 31:76–80. doi: 10.1177/0890334414554620

31. International Labour Organization. Maternity Protection Convention, n° 183. (2000). Available online at: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C183 (accessed April 27, 2021).

32. Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho. Decreto-Lei n° 5.442. (1943). Available online at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/del5452.htm (accessed April 27, 2021).

Keywords: breastfeeding, breastfeeding support, breastfeeding promotion, breastfeeding policies, lactation workplace programs, program evaluation, sustainable development, sustainable development goals

Citation: De Souza CB, Venancio SI and da Silva RPGVC (2021) Breastfeeding Support Rooms and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development Goals: A Qualitative Study. Front. Public Health 9:732061. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.732061

Received: 28 June 2021; Accepted: 29 November 2021;

Published: 23 December 2021.

Edited by:

Angela Giusti, National Institute of Health (ISS), ItalyReviewed by:

Francesca Zambri, National Institute of Health (ISS), ItalyCopyright © 2021 De Souza, Venancio and da Silva. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carolina Belomo De Souza, YmVsb21vLmNhcm9saW5hQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.