- 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 2Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 3Center of Excellence for Occupational Health, Research Center for Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 4Department of Health Education and Promotion, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 5Department of Community Oral Health, School of Dentistry, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 6Department of Endodontic, The Infection Control Committee, School of Dentistry, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 7Noandishan Behbood Gostar Kimia (NBGK) Company, Hamadan, Iran

- 8Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

- 9Department of Community Oral Health, School of Dentistry and Dental Research Centers, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Background: Coronavirus Diesease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has led to the suspension of the activities of dental schools. Therefore, reorganizing clinical settings and supporting services as quickly as possible has received much attention to reopen dental schools. The present study aimed to evaluate the applicability of the Intervention Mapping (IM) approach for designing, implementing, and evaluating an intervention program to prevent and control COVID-19 in dental schools.

Methods: Following the IM protocol, six steps were completed in the planning and development of an intervention, targeting, and management of Dental School during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results: The information obtained from the needs assessment revealed that the COVID-19 outbreak prevention was associated with the use of personal protective equipment by all target groups, infection control measures taken in the environment, preparation of the environment and equipment, changes in the treatment plan according to the COVID-19 pandemic, changing the admission process of patients, and reduction of attendance of target groups in the school are linked with. In this study, determinant factors affecting the COVID-19 prevention at the individual level were identified based on the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). In this program, various methods, such as presentation of information, modeling role, and persuasion measures, were utilized and the practical programs included educational films and group discussions implemented.

Conclusions: Our findings indicated that intervention in dental environments on the basis of the IM process can develop a comprehensive and structured program in the dental school and hence can reduce the risk of the COVID-19 infection.

Background

In recent months, the high prevalence of the new coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is considered an international public health concern (1). The virus has raised a monumental challenge to clinics and dental schools in all affected countries (2). Various treatments and control measures are performed in different healthcare systems with different economic conditions and political ideologies in every country (2).

Due to the high transmissibility of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), close contact between the patients and dentists, nature of dental procedures (3, 4), and difficulty in diagnosing the disease during the incubation period and in asymptomatic individuals (5, 6) all routine dental activities have been suspended in schools (7) and reduced to emergency treatments and virtual training in affected countries (8).

The activities of dental schools have been resumed by imposing some restrictions from June 21, 2020 in Iran due to the educational needs of students and the medical needs of patients. Given the vast number of patients and their close contact with students, teachers, and staff in the dental schools, some managerial, educational, and environmental interventions are necessary to be implemented for the protection of all stockholders. To reopen the schools, it is required to provide immediate educational, clinical, and support services (4).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American Dental Association (ADA), and WHO have provided some effective practical guidelines for controlling the prevalence of COVID-19 in dental settings (9–11). However, previous studies showed that the ultimate effect of health interventions depends not only on the effectiveness of the intervention but also on its accessibility in populations, proper application, the extent of providing information, awareness of the target groups, and the existence of a sanction to perform it correctly and completely (12). Inadequate implementation of effective interventions, guidelines, and policies could reduce the risk of transmission of the COVID-19 infection among patients, students, teachers, staff, and society and its spread in these environments (13, 14). Therefore, to implement the interventions and guidelines, there is a need for a systematic process contributing to the promotion and implementation of evidence-based interventions, which can identify determinants, mechanisms, and strategies for effective interventions (13). In this research, an intervention approach was introduced and described to implement a program for the prevention and control of COVID-19 in the School of Dentistry of Ibn-Sina University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran. The School of Dentistry implemented the interventions to achieve the Safety and Hygiene Scheme standard (SHS: 2020).

Intervention Mapping

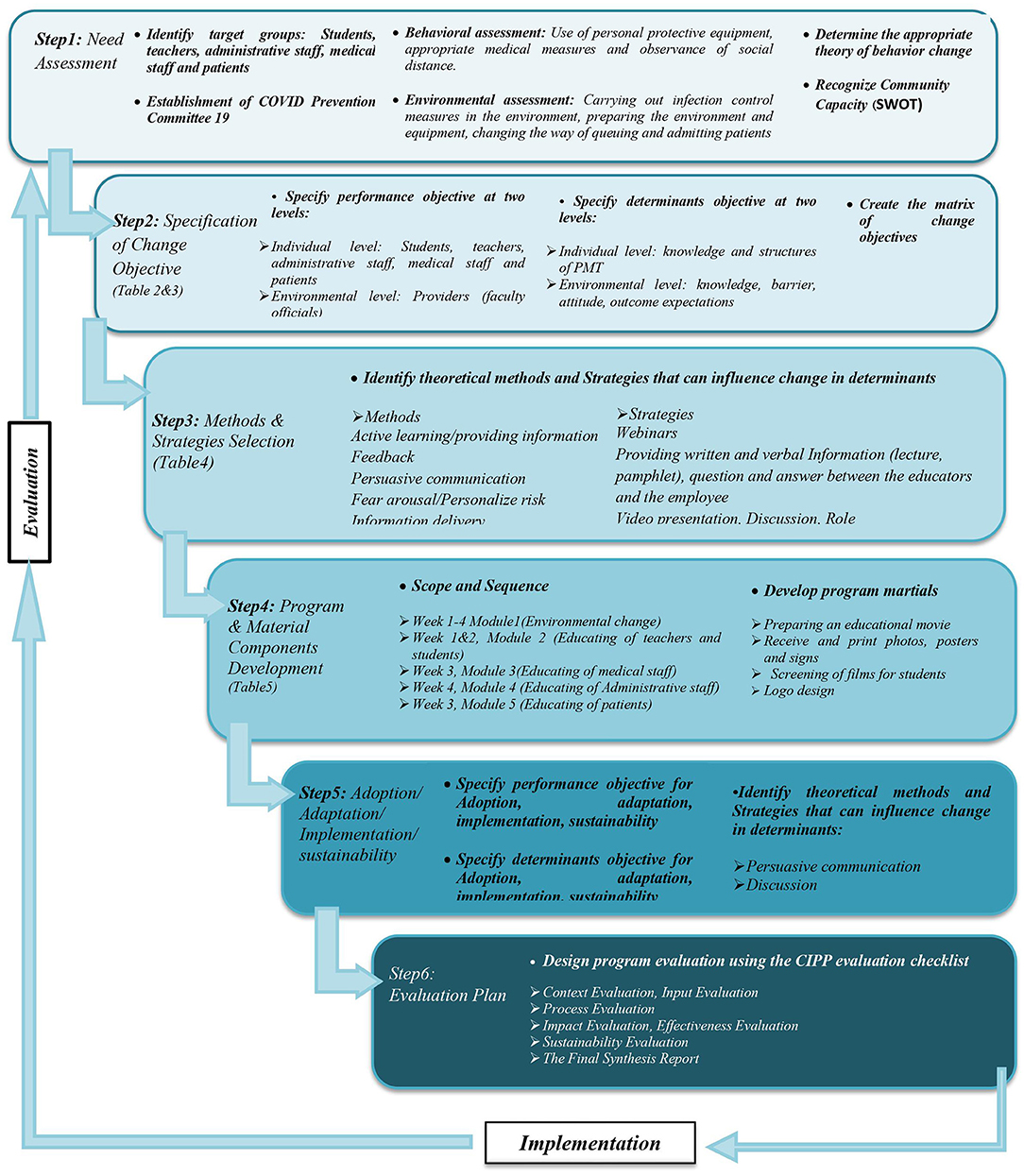

It is a protocol that helps to design multilevel health promotion interventions and selects appropriate implementation strategies (15). IM consists of six steps, and each of these steps involves a variety of tasks. Completing tasks at each stage serves as a guide for the next steps. Completing all steps acts as a work plan for designing, implementing, and evaluating interventions, that is based on theoretical, experimental, and practical information. The steps are as follows:

Step 1: Conducting needs assessment

Step 2: Specifying change objectives

Step 3: Selecting theory-based methods and practical strategies

Step 4: Developing program components

Step 5: Specifying implementation

Step 6: Generating evaluation plan (15).

Steps 1–4 focus on the presentation of multilevel interventions for improving health behaviors and environmental conditions.

Methods

Step 1: Conducting Needs Assessment

In the first step of IM, planners evaluate assets and needs.

At this stage, all representatives, such as executives and those who are responsible for protecting the intervention, were involved in the program to determine required measures for implementing the program and identifying determinants (obstacles and facilitators). To involve patients in the program, a committee called the COVID-19 Prevention Committee at the School of Dentistry (CPDS) was formed on May 21, 2020. The members of this committee consist of the representatives of the students, the chairman of the infection control committee of the school, representative of the university teachers, staff representative, manager of the nursing office, patient representative, an IT official of the school, representative of the department of financial and administrative affairs of the school, the head of public affairs, the dean of the school, and some SHS2020 standard company's representatives. The recognized stakeholders were in both individual and environmental levels. The team manager (Head of the School) determined the responsibilities of each team member and the decision-making structure. During this session, the members of the three teams, namely, education, infection control, and logistics, were separately assigned for performing relevant activities.

To assign all actors, barriers, and potential facilitators of implementing the intervention, it was necessary to conduct a needs assessment. For this reason, the brainstorming method was used in CPDS, and the results of the previous regular evaluation that have already been conducted in the school were applied. Moreover, the environmental conditions were observed and evaluated.

At this point, social, epidemiological, and behavioral-environmental analyses were performed. The needs assessment of the present study was focused on the school as the target group, such as teachers, students, staff (medical and administrative), and patients. This entailed a review of literature on determinants and factors associated with the prevalence of COVID-19 in dental settings and the role of behaviorally and environmentally predetermined risk factors in the rise of the prevalence of COVID-19 and its determinants. The committee used the experimental data, theoretical references, and collected new data (through focus group interviewing with students, patients, and infection control members of the school) to prepare a list of behavioral and environmental risk factors affecting the spread of COVID-19 and its determinants. In this phase, recognition of the school capabilities was achieved.

Step 2: Specifying Change Objective

At this stage, CPDS identified the expected changes in the behavioral and environmental factors, which were already determined in the needs assessment stage. The prioritization of behavioral and environmental consequences was performed according to their importance and variability by literature review and the consensus between the members of the CPDS committee. Afterward, functional objectives were determined for each behavioral and environmental consequence and their determinants, and a matrix of change objectives was plotted for each program level. We used brainstorming, a review of literature, and constructs of health promotion theories to identify the determinants.

Step 3: Selecting Theory-Based Methods and Practical Strategies

In this step of CPDS, the brainstorming method and literature review were used to identify the appropriate methods and strategies affecting the determinants in step 2. During this process, a summary of the theoretical methods proposed by Bartholomew et al. was applied (15). Special efforts were made for searching and selecting existing strategies, which are consistent with the theoretical methods and specific objectives of the intervention.

Step 4: Developing Program Components

In this step, the intervention content was proposed by the CPDS team, and the protocols of implementation, activities, and training materials were produced. The cultural adaptation of these programs was conducted through consultation with the program stakeholders. Then, the scope, sequence, communication channels, themes, and a list of required materials were provided and documented. Meanwhile, a review of the existing training materials was performed to determine whether the training materials have already been consistent with the objectives of this program or not. Afterward, the required training materials were produced and pre-tested.

Step 5: Specifying Implementation

At this step, the potential adopters and implementers of the program were identified. A review of the transplantation system (CPDS) was also performed. Then, the functional objectives of adoption, implementation (in terms of loyalty, comprehensiveness, and dose), and program survival were identified. In the next stage, the determinants of adoption, implementation, and survival of the program were determined using the brainstorming method and literature review. Based on the importance and variability, the prioritization of the change objectives was conducted. Then, appropriate methods and strategies affecting the determinants of adoption, implementation, and survival of the program were selected, and the intervention was designed and developed to use the program.

Step 6: Generating Evaluation Pan

In the final stage of IM, a plan was provided by the planners to evaluate the effectiveness and quality of the intervention (15). In the implemented program evaluation, the content of the questions was designed based on the information collected from the needs assessment and other previous steps of the IM.

A checklist was designed for the evaluation of behavioral and environmental factors, performance objectives, determinants, and change objectives. A checklist was also designed for the process evaluation. Evaluation indicators and criteria were determined, and the evaluation plan was documented. To evaluate the program, the context, input, process, and product (CIPP) evaluation checklist was utilized (16). The evaluation process was prepared by the CPDS team as soon as the agreement was reached on the content of the intervention.

Ethical Consideration

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1399.416). The questionnaire was anonymous, and informed consent was obtained from the participants in the survey. Participation in the study was voluntary.

Results

Step 1: Conducting Needs Assessment

As of May 21, 2020, a total of 129,341 cases with COVID-19 have been laboratory confirmed and 7,249 deaths diagnosed (11); and these numbers are rising. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) report, the healthcare workers who are exposed to aerosols generated during the examination or treatment of patients are at high occupational risk for COVID-19 (17, 18). Due to the unique features of dental procedures that generate a large number of droplets and particles suspended in the air. Moreover, due to the exposure of dental staff to blood, body fluids, saliva, and microorganisms in the mouth, nose, and respiratory secretions, the possibility of cross-infection between dentists and patients is very high (19). Therefore, dentistry is one of the most important occupations in terms of COVID-19 transmission and involvement. At this stage, the recipients of the program were identified, such as students, professors, medical staff, administrative staff, and patients. The literature review showed that the use of personal protective equipment by all target groups, performing infection control measures in the dental operatory area, preparing the environment and equipment, changing the way of queuing and admission of patients, reducing capacity and attendance of patients to reduce population density per unit area, and reducing the exposure time of the target groups in the departments are associated with the prevention of the spread of the COVID-19 disease (20, 21).

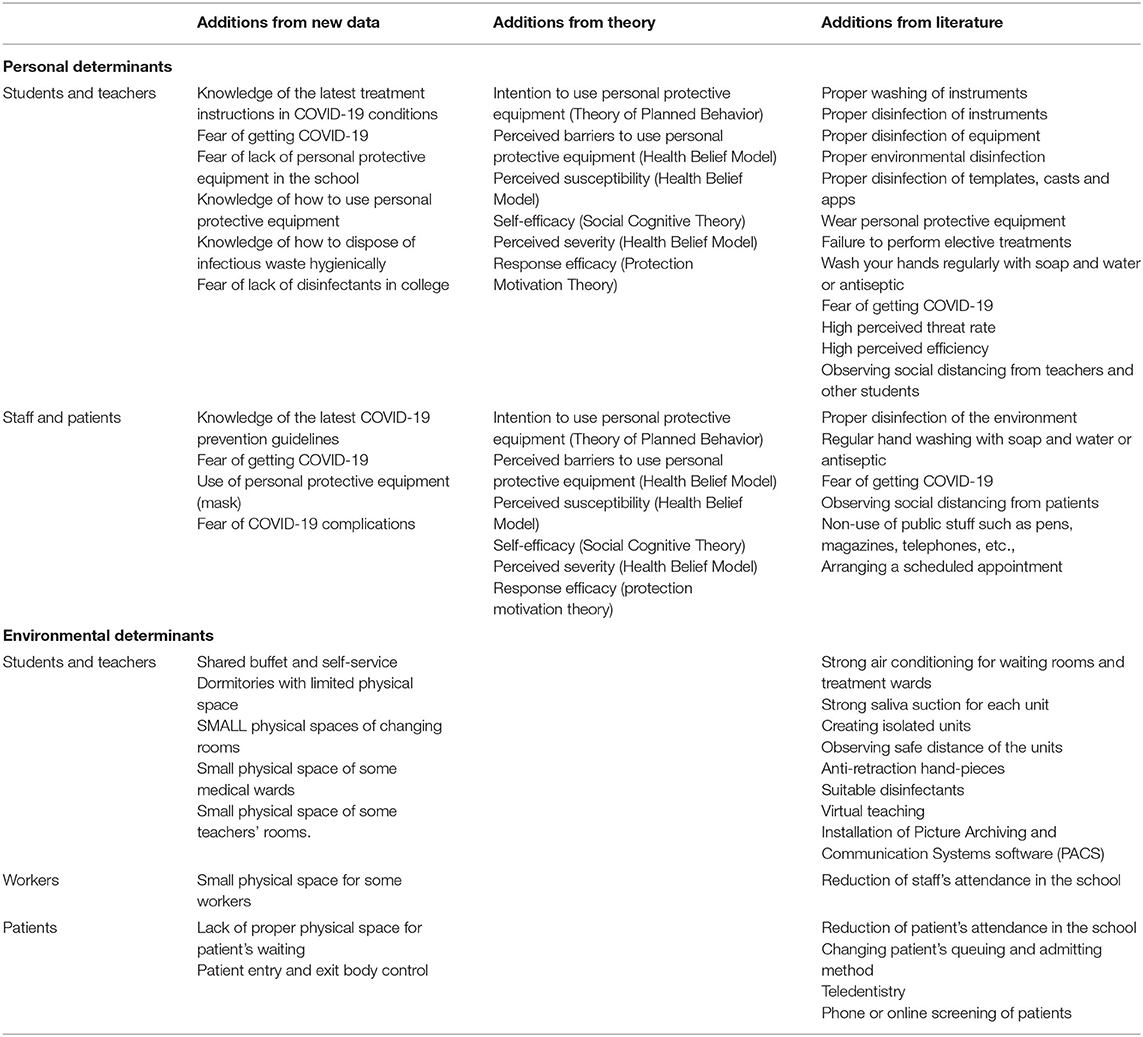

One of the key points in the control of infectious disease epidemics is designing interventions to emphasize the simultaneous increase of perceived fear and threat and perceived efficacy (such as, the effectiveness of the proposed strategies) for disease prevention and self-efficacy. Therefore, Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) was used to better understand the performance of preventive behaviors at an individual level (Table 1).

A high commitment of management to implement the intervention, high level of staff education, access to new device/equipment, sufficient budget, sufficient workforce to implement the intervention, and presence of qualified professors in the field of infection control were among the strengths of the faculty.

Step 2: Specifying Change Objective

Based on the information obtained from the needs assessment stage, two objectives of the program (at the individual and environmental levels) were considered to prevent the spread of the COVID-19. For the target group, such as students and professors, the program was defined at the individual level as the use of appropriate personal protective equipment and suitable treatment measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (such as reducing exposure time and social distance).

In the target group of administrative staff and patients, the implementation of the preventive behaviors to prevent the transmission and spread of COVID-19 was considered as the program objective at the individual level.

Due to the important role of the medical staff and service personnel in infection control, the use of appropriate personal protective equipment and precise infection control measures among them was considered at the individual level in addition to the other staff.

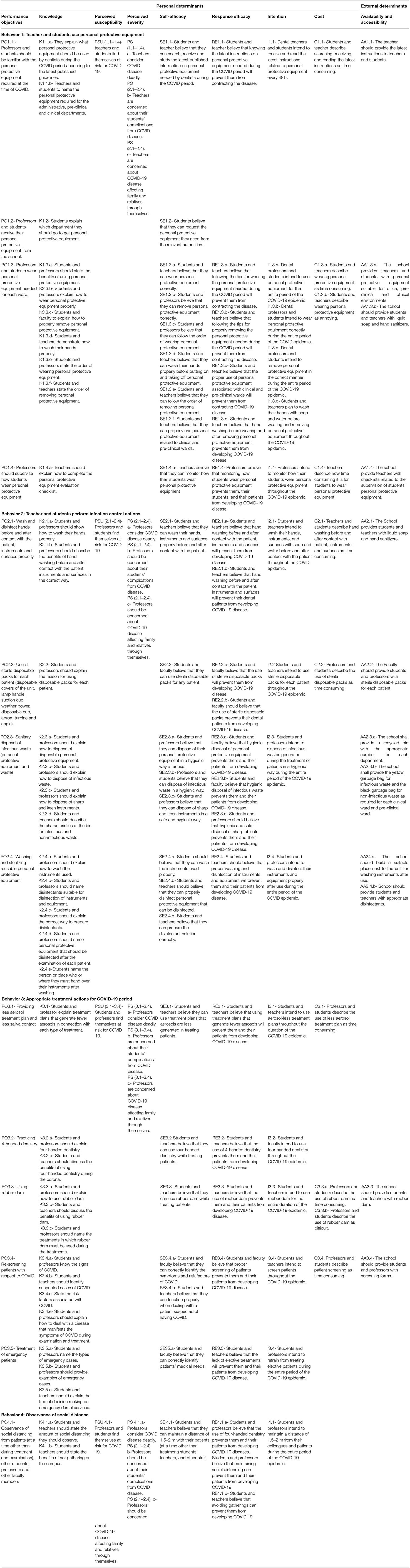

In addition, the objectives of the program for environmental factors were to prepare the environment and equipment, change the system of queuing and admission of patients, and reduce the capacity of target groups in the faculty. According to the program objectives, performance objectives were defined at the individual level for students, professors, administrative staff, medical staff, and patients, and the performance objectives were defined at the environmental level for providers (faculty officials).

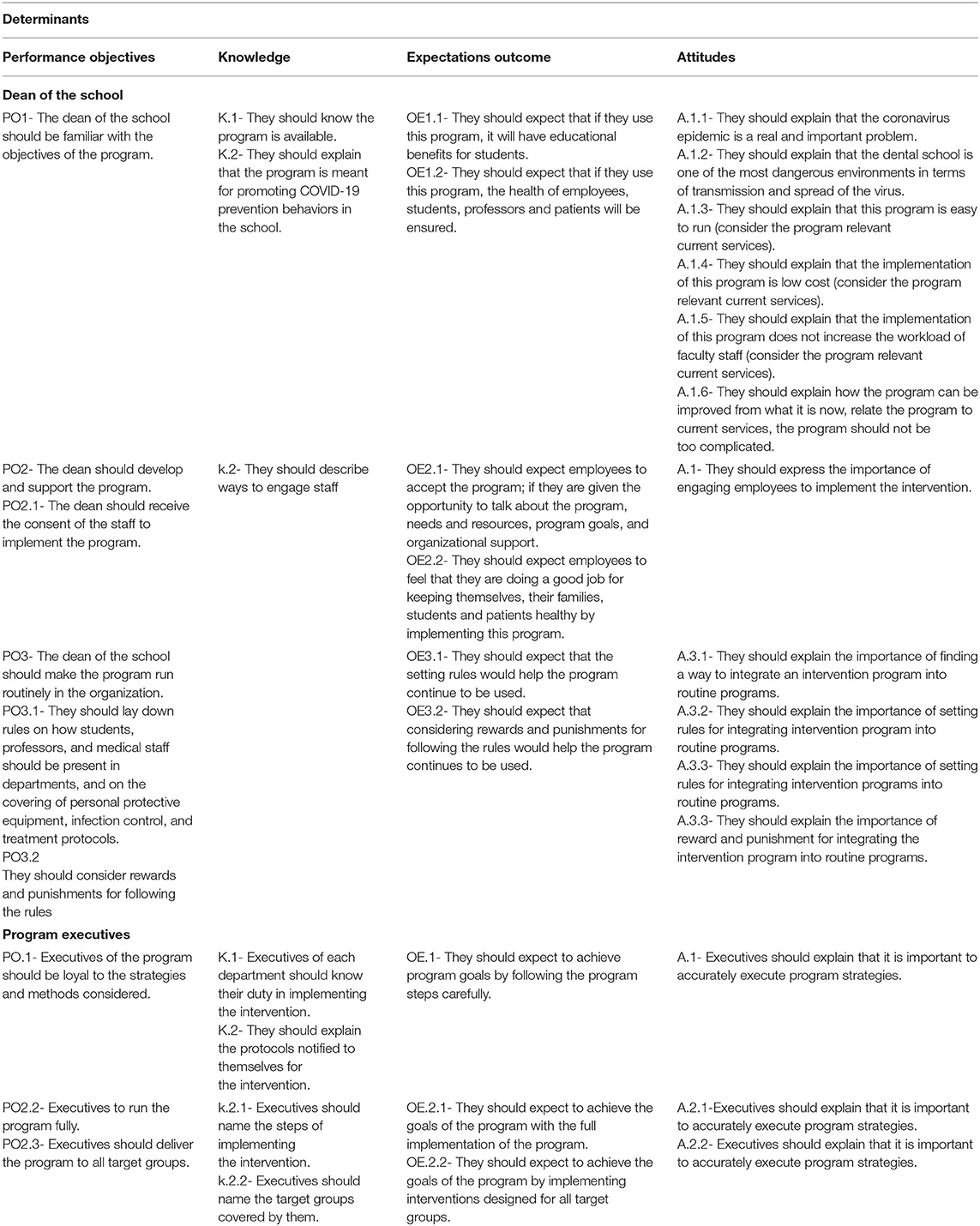

After identifying the functional objectives, the important and changeable determinants of these objectives were selected for each level based on the results of the IM phase. For the individual level, PMT was selected as a framework for describing factors in relation to preventive behaviors of COVID-19 (22). Another important determinant was knowledge about the latest COVID-19 prevention guidelines in dental settings. Table 2 presents an example of this matrix.

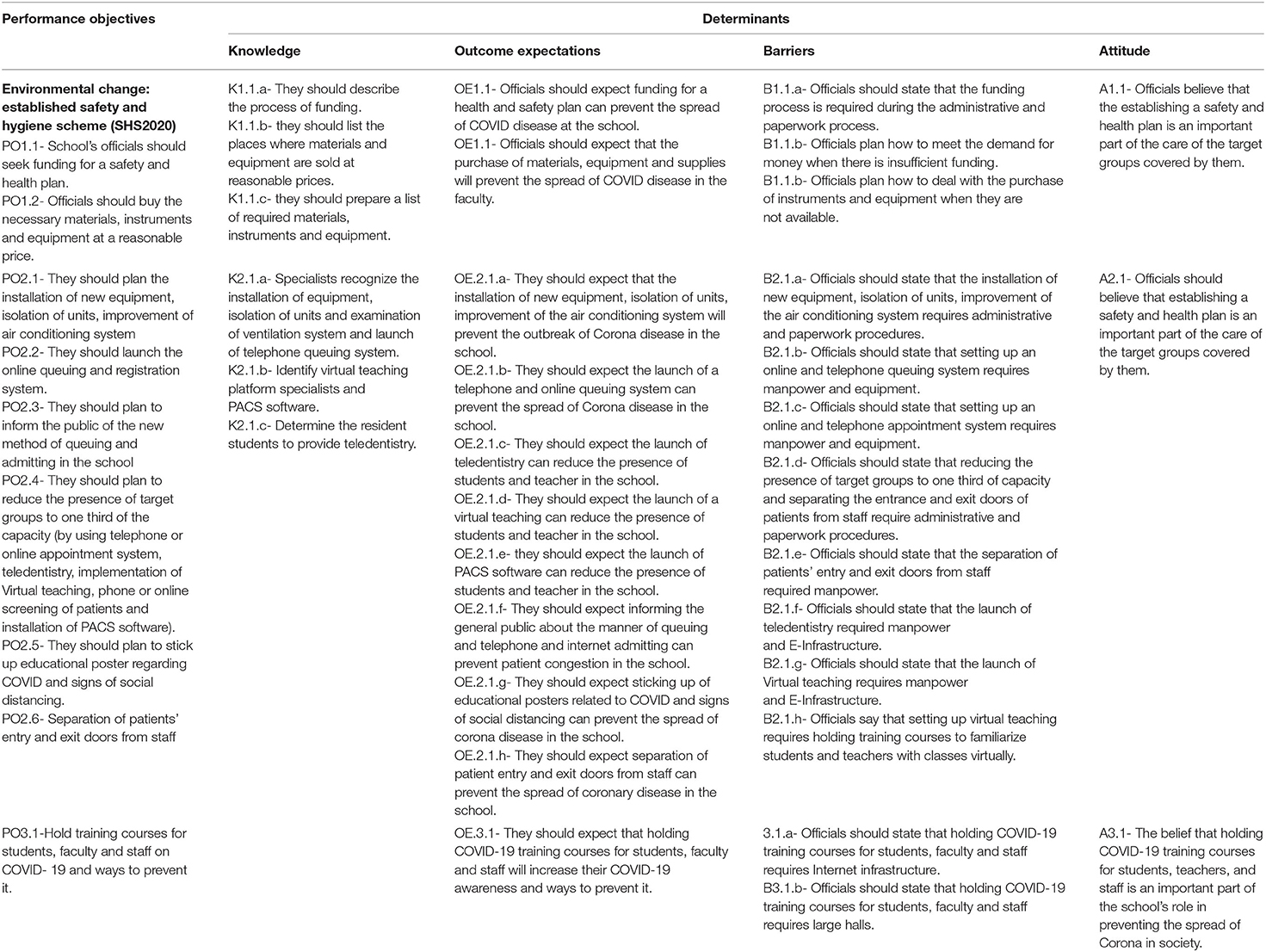

Finally, for providers (school's officials) at the environmental level, the knowledge of the latest COVID-19 prevention guidelines in dental settings, barriers, attitudes, and outcome expectations were chosen as determinants. Next, the matrix of change objectives, which is derived from the intersection of performance objectives with determinants, was formed for each level of intervention (Table 3).

These performance objectives have been developed based on the protocols of the WHO, CDC, and the Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran (9–11).

To reduce the presence of target groups in the school, contact-less treatment and remote learning were considered. This intervention was performed by using a telephone or online appointment system, teledentistry, implementation of virtual teaching, phone or online screening of patients, and installation of the Picture Archiving and Communication Systems software (PACS). The patient screening was conducted through a telephone call or appointment system so that before making an appointment, the patient was asked to complete the COVD-19 screening. After completing the screening form, if he/she was not identified as a high-risk case, was referred to oral diseases resident to do teledentistry. At this level, patients would express their symptoms and problems, and then if necessary, would send a photograph of their mouth to the oral diseases resident. The resident determines whether the person needs essential or urgent treatment or not based on the patient history and the provided photograph. An appointment was considered for the patients who need special treatments.

Virtual teaching was considered for theoretical courses. Adobe connect platform was considered for theoretical courses and webinar.

The installation of PACS software, which reduces paper records, increases the speed and accuracy of diagnoses and subsequently reduces the patient waiting time and their contact with staff, students, and faculty in the department. The PACS software could increase the speed and accuracy of diagnoses and subsequently reduce the patient waiting time and their contact with staff, students and faculty in the department.

Step 3: Selecting Theory-Based Methods and Practical Strategies

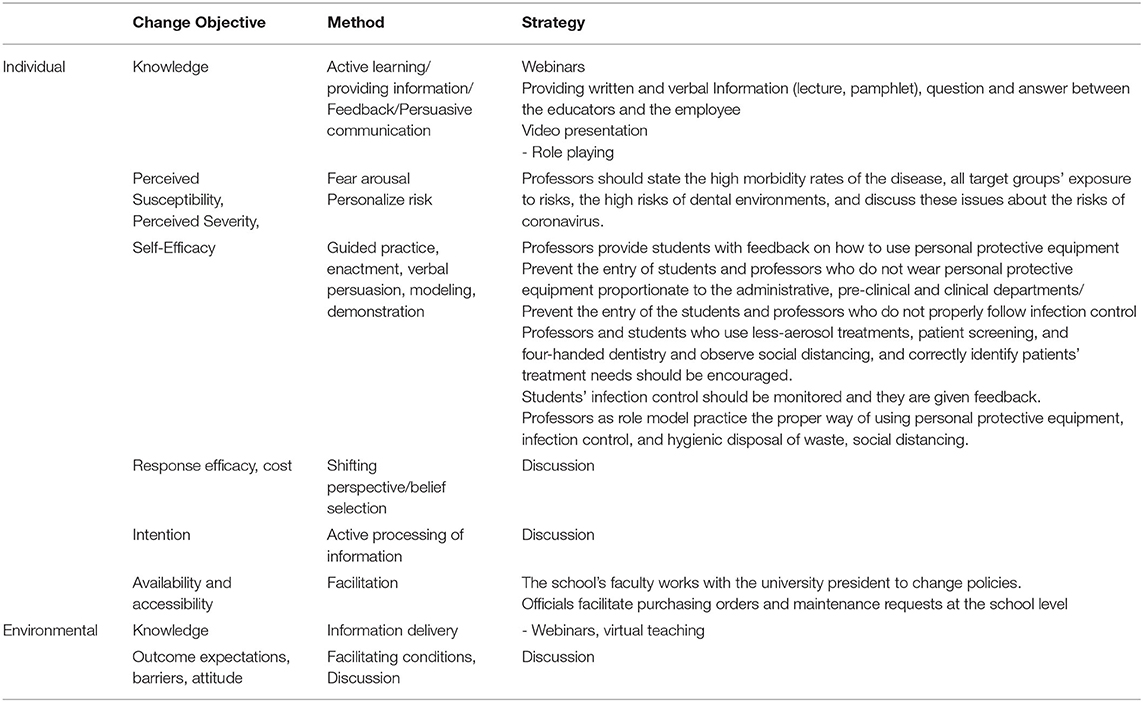

At this stage, all the change objectives were organized by the relevant determinants, and the methods of each category of the objectives were identified through the brainstorming method. Afterward, a theoretical and experimental review was performed to identify the appropriate methods and strategies for changing determinants.

The strategy planning team determined the strategies in two ways, such as (1) brainstorming and documenting ideas about strategies, materials, and communication channels during the planning process; and (2) thinking about selected methods and deciding on the specific strategies that can make them practical. Table 4 represents the selected methods and practical applications for changing the factors determined at each level of the intervention.

Table 4. Overview of the selected theoretical methods and practical strategies used in the intervention.

Step 4: Developing Program Components

In this step, a final intervention framework was produced for implementation. Based on the needs assessment data and the additional focus group discussion with the target group, to collect the data regarding intervention material preferences, the planning team provided a list of intervention materials and activities. In practical, in this intervention, the COVID-19 instructions recommended by Iran's Ministry of Health and the instructions in relation to infection control were considered (9).

A three-part educational video entitled “Providing Dental Services in COVID-19 Conditions” was also provided by the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences based on the latest instructions of the Ministry of Health. Photos, posters, and signs were received and prepared from the Ministry of Health website. The video clip was displayed for residents.

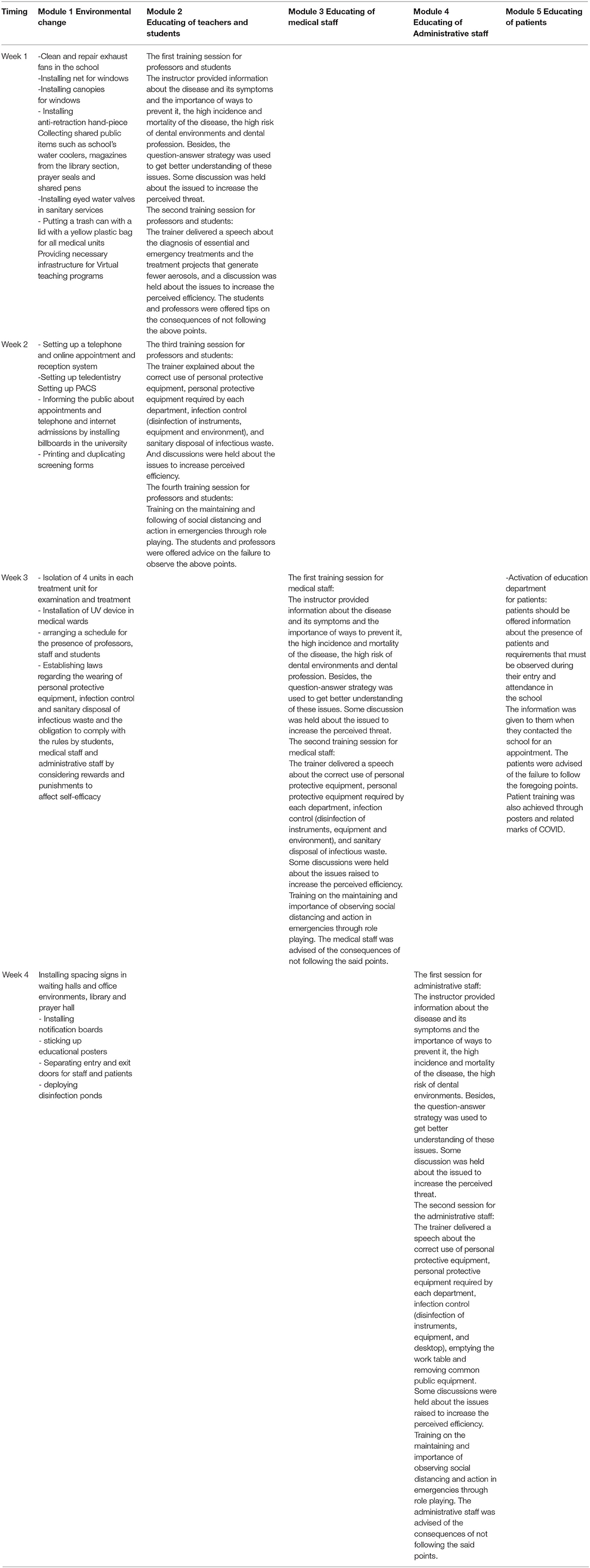

The intervention was implemented at the faculty through the development of intervention modules. Table 5 presents an overview of the interventions and their related modules. The intervention at the faculty level consisted of five intervention modules (modules 1–5). A logo was designed for the program, which expresses an important health message to faculty stakeholders (Figure 1). During the formative phase, positive recommendations were received regarding the designed logo.

Step 5: Specifying Implementation

In this step, IM helped planners to adopt and implement the programs. The executive team included the head of the dental school. The executives of the program included the middle managers (head of public affairs, administrative, and financial deputy), ward managers, infection control team of the school, and the representatives of SHS2020 standard.

Table 6 illustrates the performance of objectives for the adoption, implementation, and survival of the program. Persuasive communication and discussion were used as effective methods for adopting and implementing the intervention. For this reason, in the first step, a briefing session was held with the program executives, and then they were informed about the objectives and all the program information.

Then, the executive team was informed about the methods and strategies for implementation of the intervention in different target groups and the tasks of the designated teams in detail.

The instructions of the Ministry of Health were also provided for the executors.

Step 6: Generating Evaluation Plan

Context, Input, Process, and Product evaluation checklist was used to evaluate the program (16). This checklist is composed of 10 components, such as the contract agreements, context, input, process, impact, effectiveness, sustainability, transportability evaluation, Meta evaluation, and final synthesis report (16). To perform the evaluation of the program according to the CIPP model, the activities required for the evaluation were extracted from the last published checklist of the CIPP model (2007). Afterward, with the help of SHS2020 standard representatives, these activities were coordinated with the objectives of SHS2020 standards, and finally, the evaluation checklist was provided and completed during the internal audit.

Context, Input, Process, and Product components were selectively used in different sequences and generally at the same time depending on the need for specific evaluations (16). In this study, eight components, such as contractual agreements, context, input, process, impact, effectiveness, sustainability, the final synthesis report, were applied.

Evaluation in this study encompassed the following steps:

1. Contractual agreements: A clear understanding of the evaluation that needs to be conducted was established.

2. Assessing the conditions and programming context: The needs, strengths and weaknesses, threats, opportunities, and problems in the faculty environment were assessed and evaluated. This step was consistent with the needs assessment phase and performed concurrently with this phase.

3. Evaluation of the program inputs: Existing strategies and programs, capacity and feasibility of the designed program, evaluation of budget and equipment, tools, and materials required to conduct the program were assessed and evaluated. This step was also performed with the needs assessment phase.

4. Evaluation of the program processes: Monitoring, documentation, and evaluation of the program activities were performed, and representatives of SHS2020 standard were involved in monitoring, observation, preserving photographic records, and providing periodic progress reports on the program implementation. At this stage, the checklists were prepared and completed by the standard representatives through observation. By photography and preparing a report regarding the documentation and intervention processes and the periodic progress reports to the faculty officials, they were informed of the program process. This time, it was determined whether all the modules of the program have been implemented? Does the program run according to the predetermined sequences and strategies? Did all the target groups receive the program? To what extent are the targets groups have involved in the program? Is the predetermined performance objective accomplished?

The satisfaction of the target groups related to the intervention was also questioned.

5. Evaluation of the program consequences: The information about the acceptance, modification, or rejection of the program was evaluated by asking from the target groups. The outcomes of this program included: increasing knowledge, perceived threat, perceived efficiency, reducing barriers to understanding, and increasing preventive behaviors against COVID-19 infection, which is obtained through completing the PMT questionnaire by staff, faculty, and students before and after the intervention.

6. Evaluation of the effectiveness of program: The results of the quality and importance of the program must be evaluated. In this regard, the effectiveness of the interventions will be evaluated by the number of involved cases in dental school related to therapeutic and educational processes 3 months after the intervention. After performing above six evaluation steps by the representatives of BRSM Company and providing a report on the observance of applicable professional standards to the faculty officials, the identified defects were fixed. Moreover, the head office of the BRSM Company was invited to refer to the faculty for the final evaluation of the program. After conducting the final evaluations by the faculty, the evaluators of this company, on 28 June, 2020, considered the faculty to be eligible for the SHS2020 standard certification (23).

7. Sustainability evaluation: This stage that will be carried out by BRSM Company 6 months after the initial evaluation, it will be determined to what extent the program has been successfully institutionalized and will continue over time.

8. The final synthesis report: Consistent reports of evaluation findings were collected and communicated to the faculty stakeholders. Reports on the program background, implementation, and results of the program were presented to a wide range of audiences, and they were informed of the interventions carried out and the results of the evaluation by BRSM.

Figure 2 describes a stepwise process for dental school management during the COVID-19 pandemic based on IM. Further results on the intervention evaluation will be described in a different article.

Discussion

The present study describes the process design, content, and evaluation of COVID-19 preventive intervention in dental schools. This study for the first time provides practical and simple guidelines for reopening dental schools and providing dental services during the COVID-19 epidemic. Due to the lack of a global protocol for dental services during this pandemic, dental services have been partially or completely disrupted in many countries. In this regard, the lack of standard protocols can increase the prevalence of COVID-19 in dental health centers.

While some national health institutions, such as the NHS, have provided guidance and advice for managing clinical dental emergencies during epidemics (24). This intervention focuses on the behavioral and environmental changes simultaneously. These changes are very important to control and prevent the COVID-19 infection among dentists. In this regard, the present study mainly focused on the identification of COVID-19 preventive behaviors in target groups, factors affecting these behaviors, and determining environmental conditions.

In this study, IM was used as a conceptual framework for the intervention design. Although the design of the intervention was a time-consuming process, it can lead to the implementation of the intervention with a systematic and evidence-based approach.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ADA, and WHO provided some recommendations for the control of the prevalence of COVID-19 for dentists and dental staff, such as patient screening, infection control (environmental disinfection, equipment and tools, and unit isolation), behavioral measures (use of personal protective equipment and handwashing), and treatment measures (performing essential and emergency treatments, using rubber dam placement, reducing aerosol production during examination and treatment, etc.) (9–11).

The first essential step for the safe management of patients during the pandemic is investigating risk level of patient through screening patients to cut the transmission chain and evaluating the chief complaint of the patients (25). These cases should be managed remotely to avoid useless direct contact with patients that can increase the risk of infection for patients and dentists. In this intervention, to reduce the presence of patients, students, and professors in the school, contact-less treatment and remote learning were performed. These interventions were performed by using a telephone or online appointment system, teledentistry, implementation of virtual teaching, phone or online screening of patients, and installation of PACS. Previous studies have demonstrated that teledentistry (26, 27), virtual teaching (28–30), and PACS software (31) reduced the prevalence of COVID-19 among dental schools through the reduction of contact between individuals.

The most important measures to control the infection included selecting one person to supply the disinfectants for surfaces, equipment, and tools. At the beginning of each day, this person prepared the appropriate disinfectants for the surfaces, equipment, and tools according to the standard protocol and provided them for the medical staff in different wards. Isolation of well-ventilated dental chair unit (with conventional and novel air conditioning systems, such as photocatalytic technologies and windows) was conducted as another important measure of infection control (32).

Fear arousal strategy as behaviors that protect people against life-threatening conditions (such as COVID-19) is often used as an effective way to promote health, prevent disease, and adopt healthy behaviors in society (33). However, this strategy can be effective when people are confident that can perform the recommended measures (self-efficacy), and meeting the recommended measures has favorable consequences (response efficiency) for them. In this study, the PMT model was used to identify the determinants affecting behavioral factors, and methods and strategies of behavioral changes. Regular monitoring of certain behaviors (such as wearing personal protective equipment and medical measures) and rewards and punishment for not following the behaviors as important behavioral measures were considered to increase the effectiveness of the target groups. In this intervention, to avoid overcrowding of people in the faculty and the risks associated with infection, virtual online and offline teaching, webinar lecture, and training sessions were held for the students and professors. Virtual teaching as a suitable method offers many advantages, such as saving time and better performance of students (34).

Staff training was also conducted in small groups in large spaces with proper ventilation.

In the present study, the intervention was designed based on the latest scientific findings in the field of COVID-19 as another important measure. Therefore, a scientific research team was formed to access the latest scientific findings through searching and then inform the planning team every 72 h. The planning team examines the received information scientifically, evaluates their compliance with the facilities and policies of the organization, makes the necessary changes in the program, and informs the project implementers. However, finding a balance between previous and new findings and constantly updating the information regarding the transmission and prevention ways of COVID-19 are still challenges, especially in dentistry.

This study had some limitations at the time of implementation of the intervention. These limitations were related to insufficient scientific information about the nature of the virus like its transmission modes, and incubation time, and due to constant updating information, the effectiveness of the preventive methods remains a challenge.

Conclusions

This study describes the performance of the Iranian School of Dentistry in developing disease prevention strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the IM process. Our findings indicated that the intervention in dental settings based on the IM process leads to a comprehensive and structured program in dental schools. Therefore, the teamwork can consider the necessary changes in the running programs as the global and national guidelines for the epidemic change. Therefore, it can be concluded that intervention in dental environments based on the IM process can develop a comprehensive and structured program in the dental school.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (approval code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1399.416). This study and the method of obtaining consent were approved by the Ethics Committee. The questionnaire was anonymous and informed consent was considered as agreeing to participate in the survey. Participation in the study was voluntary. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AM, SS, SB, NR, AH, MM, HK, and OA contributed to the study concept and design. SS, NR, BB, OA, and AP contributed to the acquisition of data. SS, MM, and AP contributed to the initial drafting of the manuscript. SS, AM, AH, and SB contributed to study supervision. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and critical revision of the report.

Funding

We acknowledge funding from the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (9905283448).

Author Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; IM, Intervention Mapping; PMT, Protection Motivation Theory; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; CDC, Disease Control and Prevention; ADA, American Dental Association; WHO, World Health Organization; CPDS, COVID-19 Prevention Committee at the School of Dentistry; OSHA, Occupational Safety and Health Administration; SHS, Safety and Hygiene Scheme standard; NHS, National Health Service; CIPP, Context, Input, process, product; PPE, Personal protective equipment.

References

1. The Lancet. Emerging understandings of 2019-nCoV. Lancet. (2020) 395:311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30186-0

2. Coulthard P. Dentistry and coronavirus (COVID-19)-moral decision-making. Br Dental J. (2020) 228:503–5. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1482-1

3. Zemouri C, de Soet H, Crielaard W, Laheij A. A scoping review on bio-aerosols in healthcare and the dental environment. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0178007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178007

4. Qian M, Wu Q, Wu P, Hou Z, Liang Y, Cowling BJ, et al. Psychological responses, behavioral changes and public perceptions during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: a population based cross-sectional survey. medRxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.02.18.20024448

5. Backer JA, Klinkenberg D, Wallinga J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20–28 January 2020. Eurosurveillance. (2020) 25:2000062. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062

6. Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Internal Med. (2020) 172:577–82. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504

7. Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, Adnan S, Aftab M, Zafar MS, et al. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2821. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082821

8. Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. (2020) 12:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9

9. CDA Committee. Protocol for the Provision of Dental Services and Related Letters in the Context of the COVID-19 Epidemic. Tehran: The Ministry of Health and Medical Education (2020).

10. CDC CfDCaP. CDC Recommendation: Guidance for Dental Settings. CDC (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html (accessed July 21, 2020).

11. World Health Organization. Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection When COVID-19 is Suspected. WHO (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19 (accessed July 21, 2020).

12. Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. (2011) 104:510–20. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180

13. Fernandez ME, Ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, et al. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:158. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00158

14. Fernandez ME, Ruiter RA, Markham CM, Kok G. Intervention mapping: theory-and evidence-based health promotion program planning: perspective and examples. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:209. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00209

15. Bartholomew E, L Kay, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Fernández ME, Kok G, et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. Washington, DC: John Wiley & Sons (2016).

17. OSaHA. Worker Exposure Risk to COVID-19. Michigan (2020). Available online at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3993.pd (accessed June 6, 2020).

18. Checchi V, Bellini P, Bencivenni D, Consolo U. COVID-19 dentistry-related aspects: a literature overview. Int Dental J. (2021) 71, 21–26. doi: 10.1111/idj.12601

19. Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings-2003. (2004) 135, 33–47. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0019

20. CDC CfDCP. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Dental Settings during the COVID-19 Response. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019).

21. CDC CfDCP. CDC Recommendation: Postpone Non-Urgent Dental Procedures, Surgeries, and Visits Washington, DC (2020).

22. Witte K. Fear control and danger control: a test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Commun Monogr. (1994) 61:113–34. doi: 10.1080/03637759409376328

23. BRS roo. SHS Certification: 2020. Ibn Sina Dental School (2020). Available online at: http://brsm.ir/node/96

24. Alharbi A, Alharbi S, Alqaidi S. Guidelines for dental care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Saudi Dental J. (2020) 32, 181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2020.04.001

25. Peditto M, Scapellato S, Marcianò A, Costa P, Oteri G. Dentistry during the COVID-19 epidemic: an Italian workflow for the management of dental practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3325. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093325

26. Rahman N, Nathwani S, Kandiah T. Teledentistry from a patient perspective during the coronavirus pandemic. Br Dental J. (2020) 14, 1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1919-6

27. Ghai S. Teledentistry during COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome Clin Res Rev. (2020) 14:933–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.029

28. Al-Azzam N, Elsalem L, Gombedza F. A cross-sectional study to determine factors affecting dental and medical students' preference for virtual learning during the COVID-19 outbreak. Heliyon. (2020) 6:e05704. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05704

29. Spanemberg JC, Simões CC, Cardoso JA. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the teaching of dentistry in Brazil. J Dental Educ. (2020) 84:1185–7. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12364

30. Chavarría-Bolaños D, Gómez-Fernández A, Dittel-Jiménez C, Montero-Aguilar M. E-learning in dental schools in the times of COVID-19: a review and analysis of an educational resource in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Odovtos Int J Dental Sci. (2020) 22:69–86. doi: 10.15517/ijds.2020.41813

31. Jahangiri L, Akiva G, Lakhia S, Turkyilmaz I. Understanding the complexities of digital dentistry integration in high-volume dental institutions. Br Dental J. (2020) 229:166–8. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1928-5

32. Poormohammadi A, Bashirian S, Rahmani AR, Azarian G, Mehri F. Are photocatalytic processes effective for removal of airborne viruses from indoor air? A narrative review. Environ Sci Pollution Res. (2021) 20, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14836-z

33. Simpson JK. Appeal to fear in health care: appropriate or inappropriate? Chiropractic Manual Ther. (2017) 25:27. doi: 10.1186/s12998-017-0157-8

Keywords: dentistry, COVID-19, infection control, intervention, evaluation, prevention

Citation: Heidari A, Miresmaeili A, Poormohammadi A, Bashirian S, Meschi M, Karkehabadi H, Baharmastian B, Aziziansoroush O, Rabienejad N and Shirahmadi S (2021) Management of Dental School During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Application of Intervention Mapping. Front. Public Health 9:685678. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.685678

Received: 25 March 2021; Accepted: 14 October 2021;

Published: 16 November 2021.

Edited by:

Satoshi Takizawa, The University of Tokyo, JapanReviewed by:

Gulnihal Ozbay, Delaware State University, United StatesYaser Maddahi, Tactile Robotics, Canada

Alexandre Rezende Vieira, University of Pittsburgh, United States

Copyright © 2021 Heidari, Miresmaeili, Poormohammadi, Bashirian, Meschi, Karkehabadi, Baharmastian, Aziziansoroush, Rabienejad and Shirahmadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nazli Rabienejad, bmF6bGlyYWJpQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==; Samane Shirahmadi, c2hpcmFobWFkaV9zQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Ali Heidari

Ali Heidari Amirfarhang Miresmaeili

Amirfarhang Miresmaeili Ali Poormohammadi3

Ali Poormohammadi3 Samane Shirahmadi

Samane Shirahmadi