- 1State Key Laboratory of Reproductive Medicine, Center for Global Health, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Modern Toxicology of Ministry of Education, School of Public Health, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

- 3Women's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Nanjing, China

- 4Department of Endocrinology, Children's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China

Background: Triclosan (TCS) is an environmental chemical with endocrine disrupting effects and can enter the body through the skin or oral mucosa. Human data about the effect of TCS exposure during pregnancy on neonatal birth weight and TCS exposure during childhood on children's growth are scarce.

Objectives: To investigate the association between maternal urinary TCS level and neonatal birth weight, as well as children's urinary TCS level and children's body mass index (BMI).

Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Finally, seven epidemiological articles with 5,006 participants from September 25, 2014 to August 10, 2018 were included in the meta-analysis to identify the relationship between maternal exposure to TCS and neonatal birth weight. On the other hand, three epidemiological articles with 5,213 participants from July 22, 2014 to September 1, 2017 were included in another meta-analysis to identify the relationship between children's exposure to TCS and children's BMI. We used Stata 16.0 to test the heterogeneity among the studies and calculating the combined effect value 95% confidence interval (CI) of the selected corresponding models.

Results: TCS exposure during pregnancy was not significant associated with neonatal birth weight. The results of forest plots were as follows: ES (Estimate) = 0.41 (95% CI: −11.97–12.78). Children's urinary TCS level was also irrelevant associated with children's BMI: ES = 0.03 (95% CI: −0.54–0.60).

Conclusions: This meta-analysis demonstrated that there was no significant association between maternal TCS level and neonatal birth weight, also there has no relationship between children's urinary TCS level and children's BMI.

Introduction

Triclosan (TCS) is a synthetic, broad-spectrum biocides, and it was first licensed for use in the 1960s (1). Nowadays, TCS is still widely used as an important antibacterial in consumer products such as soap, hand sanitizer, toothpaste, and mouthwash. TCS can be absorbed into the human body, then enter various human fluids and tissues from skin or oral mucosa (2).

Currently, the relationship between exposure to TCS during pregnancy and neonatal birth weight as well as children's body mass index (BMI) is not clear. A previous study has found that females tended to have higher TCS exposure level than males (3). A study of mothers in New York found that TCS could be detected in 100% of the 181 urine samples (4). In pregnant women, TCS in maternal serum can reach the fetus through the placental barrier, and it can be detected in umbilical cord blood (5). According to some researches, maternal exposure to TCS during pregnancy can cause certain effects on neonatal birth outcomes, such as head circumference, birth weight, and birth length (6–8). Among them, abnormal birthweight is an important birth outcome and will lead to a series of consequences. Babies born with low birthweight will face increased risks for adverse health effects in a lifetime, including cerebral palsy, neurological disabilities, and vision or hearing impairment (9). Whereas, those who are born with higher birthweight are more likely to develop obesity and breast cancer (10–13). Some studies have suggested that maternal TCS exposure can lead to increased (14) or decreased (6, 7, 15, 16) birth weight. However, some articles have shown that there was no significant relationship between maternal TCS exposure and neonatal birth weight (17–20). In addition, children are also exposed to TCS during childhood (21), and it was found that TCS exposure during this period may be related to children's growth development (16, 22). Childhood obesity is an important risk factor for children's health. In addition to the psychological consequences, obesity also increases the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, cancer, and arthritis (23). But the relationship between children's TCS exposure level and children's BMI remains controversial (22, 24).

Therefore, exploring the effects of exposure to TCS during pregnancy on neonatal birthweight and exposure to TCS during childhood on children's BMI are priorities. However, there is lack of a systematic studies about the topic. The purpose of our research is mainly to compare the effects of TCS exposure on growth indicators before and after birth. We also explored the heterogeneity of the included studies and make a subgroup analysis of involved factors that may affect the outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

In our study, we used the following search terms to retrieve the relevant literature in three electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science.

TCS Exposure During Pregnancy on Neonatal Birth Weight

In this direction, we searched the published literature until December 2019.

#1: (gestation) or (pregnancy) or (prenatal) or (antepartum) or (maternal)

#2: (triclosan) or (TCS) or (phenols)

#3: (birth weight) or (neonatal weight) or (baby weight) or (birthweight) or (birth size) or (fetal growth)

#4: #1 AND #2 AND #3

TCS Exposure During Childhood on Children's BMI

In this direction, we searched the published literature until December 2019.

#1: (triclosan) or (TCS)

#2: (obesity) or (fat) or (plump) or (obese) or (corpulent) or (overweight) or (weight) or (axunge)

#3: #1 AND #2

Inclusion Criteria

TCS Exposure During Pregnancy on Neonatal Birth Weight

The inclusion criteria for the studies were:

• Able to search the full text of literature;

• Pregnant women as the subject, not experimental animals;

• Explicitly specified the substance that pregnant women were exposed to TCS during pregnancy;

• The data showing the correlation between TCS concentration and neonatal birth weight were provided, such as estimate (ES) and 95% confidence interval (95% Cl);

• If the same population was used in different studies, we selected the recent one with larger sample size;

• The research design had no defects and the literature quality was high.

TCS Exposure During Childhood on Children's BMI

The inclusion criteria for the studies were:

• Able to search the full text of literature;

• Infants or children as the subjects, not experimental animals (population);

• Explicitly specified the substance that infants or children were exposed to TCS (ES);

• The data showing the correlation between TCS concentration and children BMI were provided, such as ES and 95% CI (outcome);

• If the same population was used in different studies, we selected the recent one with larger sample size;

• The research design had no defects and the literature quality was high.

Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria for the studies were:

(1) Not conform to the research topic;

(2) Animal studies, conference abstract, lecture literature, editorial materials or comments, and so on;

(3) Studies had design defects and poor quality;

(4) The research objects exposure to multiple environmental endocrine disruptors;

(5) Raw data was unavailable;

(6) Unpublished studies.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

At first, the titles and abstracts of all identified publications were independently reviewed by two authors based on the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for the eligibility of the included articles. Then, further screening of the remaining full retrieved papers were implemented, and the references of the selected articles were evaluated. We identified the literature that were finally adopted. Studies were exported in Endnote X7, and duplicates were automatically removed. To ensure the accuracy of the results, the two authors have also checked and corrected for duplicates manually. According to literature inclusion criteria, we used a predefined template to extract information (25). Any disagreement of between the two assessors in any of the above was settled by a discussion with a third evaluator. Then, we extracted the information of each literature, including author name, publication time, study design, location, sample size, outcome, exposure distribution, effect size, and covariate adjustment in our predesigned spreadsheet.

Quality Evaluation

Referring to the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) standard, the two authors independently evaluated the quality of each literature (26). NOS consists of three categories (selection of subject, comparability, and outcomes) and eight items. NOS ranges from 0 to 9 stars: 4 stars for selection, 2 stars for comparability, and 3 stars for outcomes. We rated each study based on criteria to estimate whether it can be included in the study. If the total number of stars is ≥6, we consider the research quality to be high. If the total number of stars is 3–5, we consider the research quality to be moderate. Otherwise, the research quality is too low and was excluded (27). The disputes regarding the grading of the literature were discussed and resolved together.

Statistical Method

All data acquisition and analysis were processed in the software Stata 16.0. We inserted appropriate information extracted from related literature in the spreadsheets and used the meta-analysis module to perform statistical analysis. We used the adjusted 95% CI in both birth weight and children's BMI as the effect value for TCS exposure during pregnancy on neonatal birth weight and children TCS exposure on children's BMI, respectively.

Specific steps: (1) Subgroup analysis: We explore the characteristics of the original studies and performed a hierarchical analysis based on different adjusted methods of TCS, different gender of infants, and different trimester that TCS was detected, and calculate the 95% CI of each subgroup; (2) Sensitivity analysis: We used a one-by-one elimination method for sensitivity analysis and chose a random effects model to analyze potential instability factors in meta-analysis, and evaluate the impact of publication bias of the overall results; (3) Heterogeneity test: If P < 0.05, i2 ≥ 50%, the articles were regarded to have high heterogeneity. Considering that heterogeneity will drive different statistical methods to summarize the data, if heterogeneity is expected, random effects models will be preferable to fixed effects models (28). Otherwise, we will choose fixed effects models; (4) Test of publication bias: Begg's funnel chart and Egger's method are used to qualitatively and quantitatively test and evaluate the publication bias of literature data. The funnel plot should be similar to the asymmetrical inverted funnel, and the dispersion of small samples is large, so it is often at the bottom of the funnel chart, and the dispersion of large samples is small, so it is at the top. Egger's method is used to evaluate whether there is asymmetry related to standard error in the research results. Since the number of our studies included <10, we use only Begg's funnel plots to analyze publication bias.

Results

Study Search and Characteristics Overview

TCS Exposure During Pregnancy on Neonatal Birth Weight

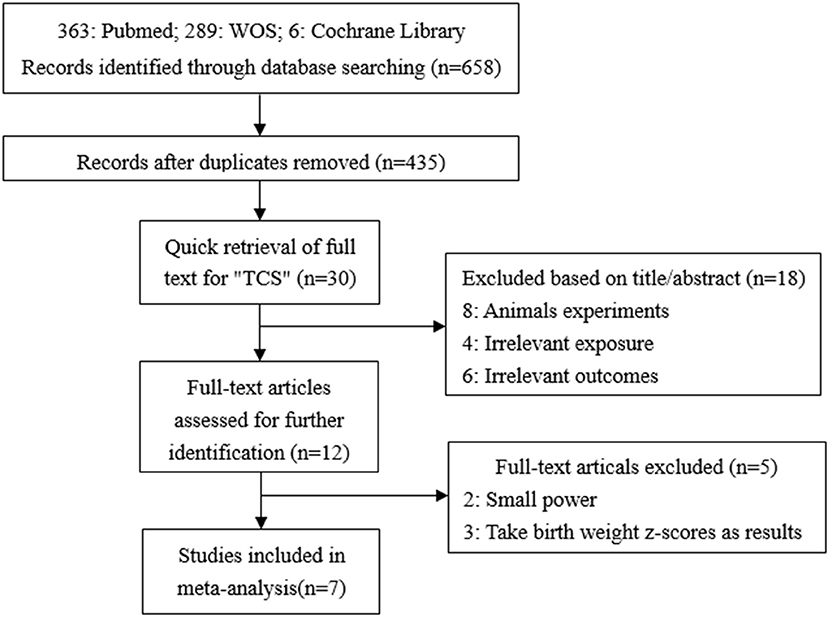

A total of 658 studies were initially included, and 435 records were obtained after eliminating the duplicate. By searching for the keyword (TCS) of the full text, 30 records were remaining. By reading titles and abstracts, 10 records were excluded due to irrelevant exposures or outcomes and eight records were experimenting on animals. The remaining 12 records were selected through reviewing the full papers. Among 12 full papers selected, five records were not considered since two had too small a sample size, and the other three records took the change in z-values as the results. Finally, seven articles were identified and included in our study (7, 14, 15, 17–20) (Figure 1). All seven studies used concentrations of urinary TCS as exposure factor, and also four of these studies used creatinine-corrected as the adjusted methods of TCS; the others used specific gravity corrected. Additionally, two out of seven studies analyzed male and female infants separately, so we have nine sets of data.

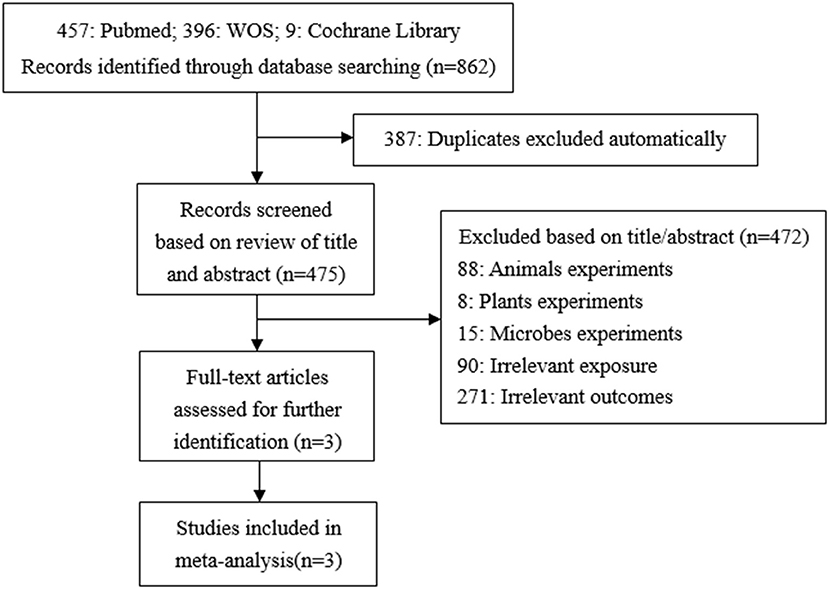

Figure 1. Flow chart of the association between maternal urinary TCS level and neonatal birth weight.

TCS Exposure During Childhood on Children's BMI

A total of 862 studies were initially included, and 475 records were obtained after eliminating the duplicate. By reading titles and abstracts, 361 records were excluded due to irrelevant exposures or outcomes, 88 records were experimenting on animals, eight records on plants, and 15 records on microbes. Finally, three articles were identified and included in our study (29–31) (Figure 2). In the same way, all of these studies used concentrations of urinary TCS as exposure factor, and the adjusted methods of TCS were creatinine-corrected.

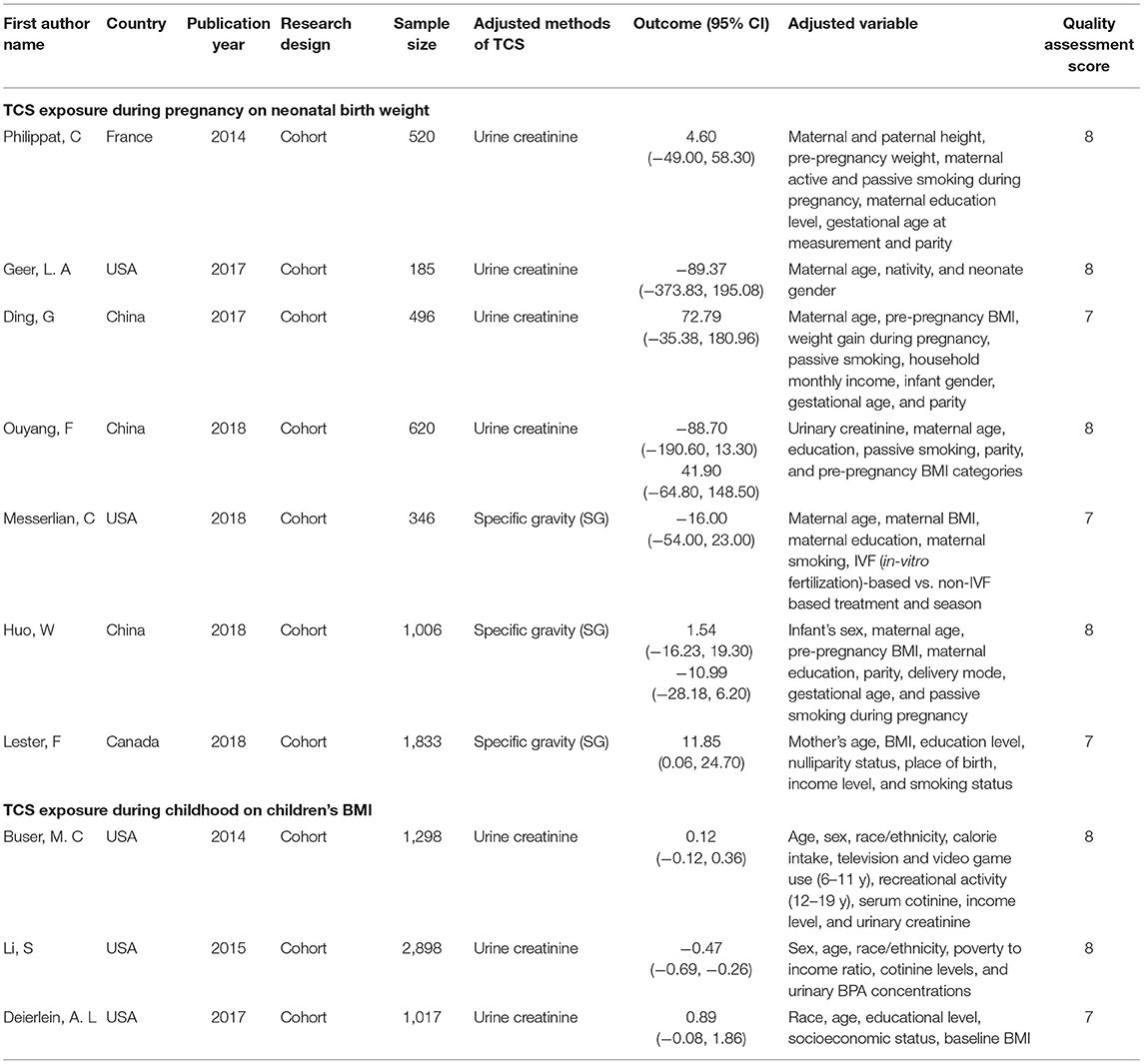

Quality Evaluation

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed by using the NOS. The characteristics of these studies are displayed in Table 1, and all of them are cohort studies. The quality assessment score of our included studies range from 6 to 8, and we considered the research quality to be high.

Correlated Forest Plots

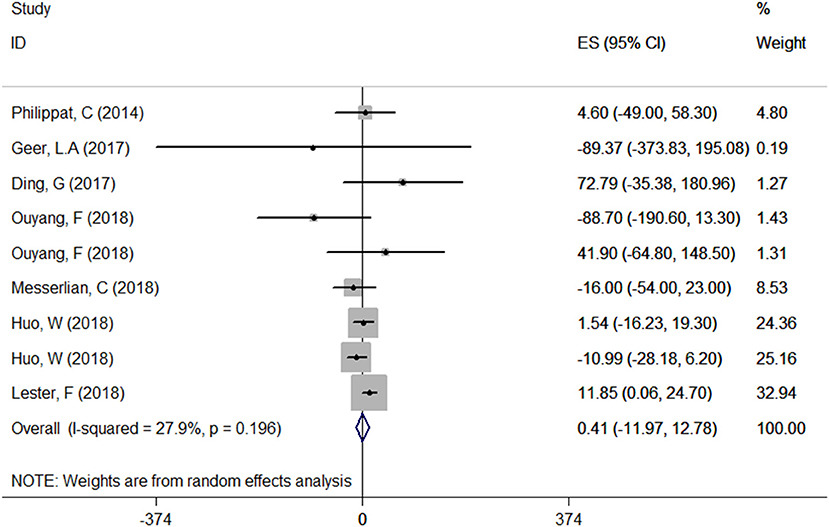

Relationship Between Maternal Urinary TCS Level and Neonatal Birthweight

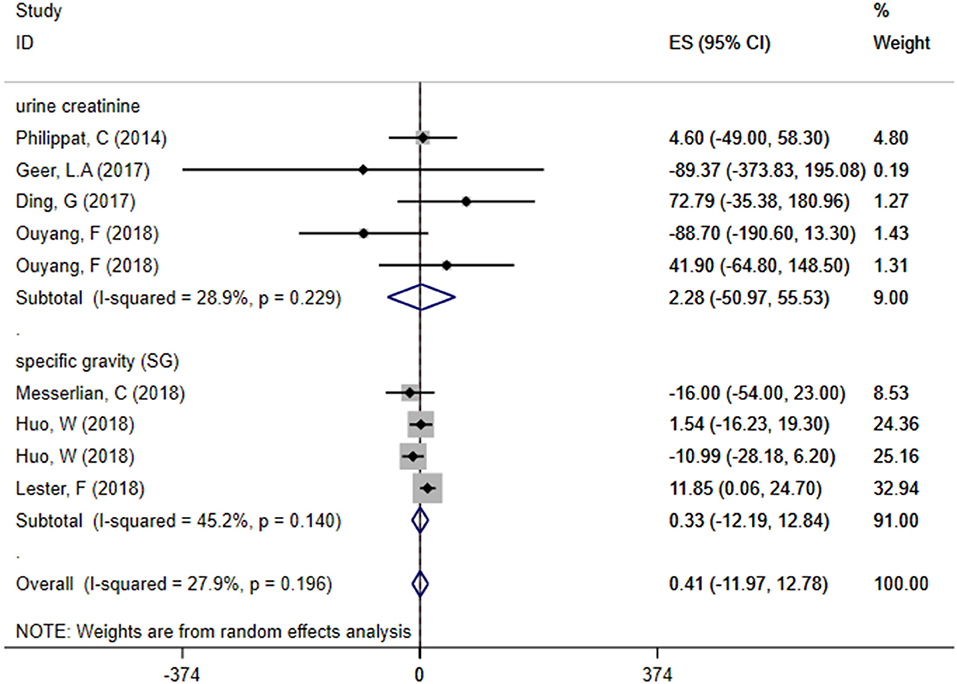

A total of seven articles were combined to analyze the relationship between TCS exposure during pregnancy and neonatal birth weight. Among seven articles, two articles studied male and female infants separately, so we have nine sets of data. The forest plot results showed that only one article (20) indicated that exposure to TCS during pregnancy may lead to the increase of neonatal birth weight with ES = 11.85 (95% CI: 0.06–24.70), while other studies found no relationship. Specfic results were as follows: ES = 0.41 (95% CI: −11.97–12.78), P = 0.196, i2 < 50%. The forest plot graph (Figure 3) shows that there are large overlaps in the CIs of these studies, indicating little heterogeneity among these studies. And there was no significant association between maternal urinary TCS level and neonatal birth weight.

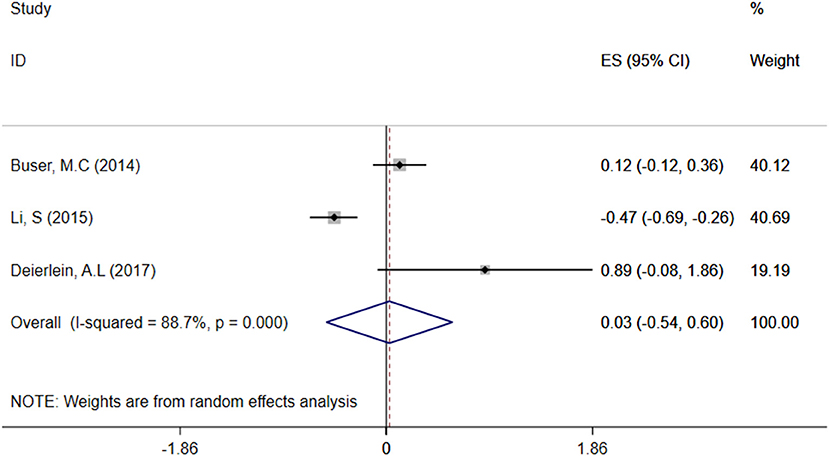

Relationship Between Children's Urine TCS Level and BMI

A total of three articles were combined to analyze the relationship between TCS exposure during childhood and children's BMI. TCS was adjusted for urine creatinine in all studies. Three articles identified a irrelevant relationship between TCS exposure during childhood and children's BMI (29–31). Specific results were as follows: ES = 0.03 (95% CI: −0.54–0.60), P = 0.000, i2 ≥ 50%, indicating a great heterogeneity among these studies. And there had no association between TCS exposure during childhood and children's BMI (Figure 4).

Subgroup Analysis—The Relationship Between Exposure to TCS of Different Adjusted Methods During Pregnancy and Neonatal Birth Weight

We divided included studies into two groups based on the adjusted methods of TCS of either urine creatinine or specific gravity (SG). The results were as follows: ES = 2.28 (95% CI: −50.97–55.53), P = 0.229, i2 < 50% and ES = 0.33 (95% CI: −12.19–12.84), P = 0.140, i2 < 50%, respectively, which manifested that whether use urine creatinine or SG as the adjusted method of TCS, the maternal urinary TCS level had no significant effect on neonatal birth weight. Meta-analysis forest plot was shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Subgroup analysis of different adjusted methods of TCS in TCS exposure on neonatal birth weight.

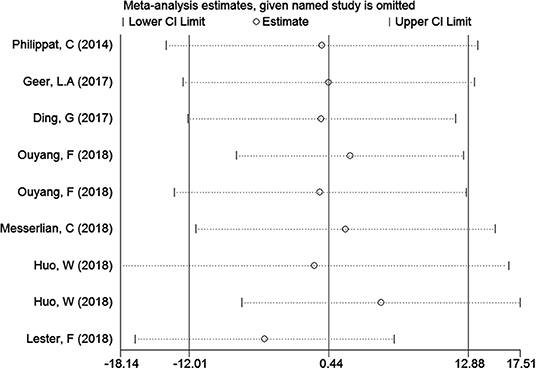

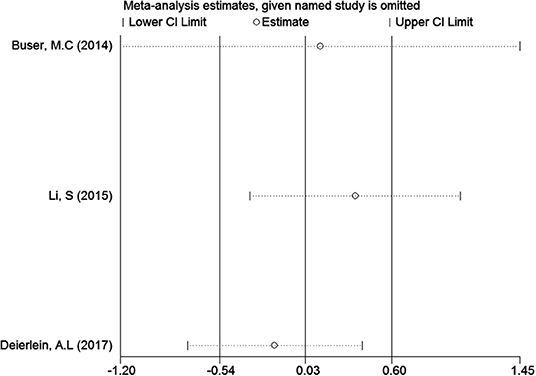

Sensitivity Analyses

In the meta-analysis of the association between maternal urinary TCS level and neonatal birth weight as well as urinary TCS level of children and children's BMI, several articles were combined, which may lead to heterogeneity between studies. However, the results showed that the pooled ES values before and after the exclusion of a study were essentially the same as the 95% CIs, indicating that the original meta-analysis was reliable (Figures 6, 7).

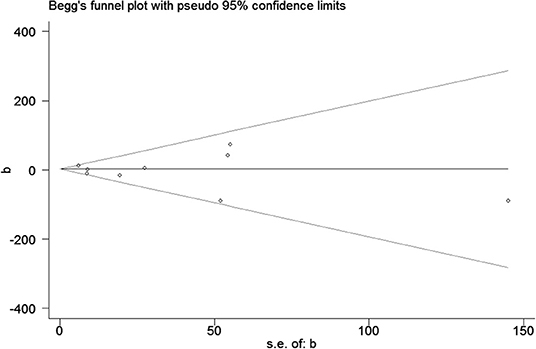

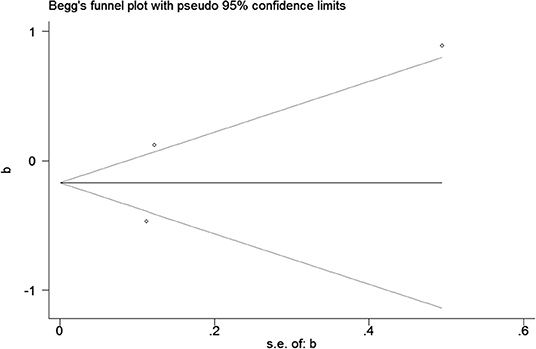

Publication Bias

Publication bias was observed for TCS exposure during pregnancy and birth weight as well as TCS exposure during childhood and children's BMI using Begg's test and funnel plots (P = 0.754; Figure 8 and p = 1.000; Figure 9). In Figure 9, all three points fall outside, suggesting the possibility of heterogeneity, but too few studies have been included, which may lead to bias in the results.

Discussion

This meta-analysis included seven studies that evaluate the effect of TCS exposure during pregnancy on neonatal birth weight and three studies that evaluate the effect of TCS exposure during childhood on children's BMI. The results showed that there was no significant association between exposure to TCS during pregnancy and neonatal birth weight, as well as exposure to TCS during childhood on children's BMI. Sensitivity analysis showed that after one-by-one elimination, the results were consistent.

Differences in the characteristics of participants, sampling times, and testing methods might lead to different results in the included studies. In the first part of our meta-analysis, Geer et al. (15) and Messerlian et al. (7) found that TCS exposure would decrease neonatal birth weight, while Ouyang et al. (14) found that there was a positive association between maternal TCS and birth weight in female infants, and a non-significant inverse association was found in male infants. These results were different from the conclusions of several other studies (17–20). Moreover, the participants in these two studies of Messerlian et al. (7) and Philippat et al. (18) were predominantly white people from the USA who were older, earned more, and most of them had a higher college education. Calafat et al. (32) found that participants who were white, older, more educated, married, and had a higher household income had higher urinary TCS concentrations, and their infants may have been more affected compared to other women. In Ouyang et al. (14), the BMI of 14.6% of participants was 23–24.9 kg/m2, 10.4% of the participants were overweight with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and 12.7% of the participants were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus; we considered that this may lead to the inauthenticity of their results. Furthermore, different studies were adjusted for different potential confounders, and this may also contribute to the inconsistent results. For example, the adjustment variables in Geer et al. (15) were only maternal age group, nativity, and neonate gender, while the adjustment variables of Messerlian et al. (7) were maternal BMI, maternal education, and season (ordinal). On the other hand, the adjustment variables of Ouyang et al. (14) were urinary creatinine, passive smoking, parity, and prepregnancy BMI categories. This may also be the reason why the conclusions of the studies by Geer et al. (15), Messerlian et al. (7), and Ouyang et al. (14) were different from others.

In our second meta-analysis, Li et al. (30) found that TCS exposure was inversely associated with BMI. Buser et al. (29) and Deierlein et al. (31) showed no significant association between TCS and children's BMI. Furthermore, Li et al. (30) detected one spot-urine sample, while other studies detected urine samples multiple times at different gestational weeks, which may have caused some bias because TCS is usually rapidly metabolized and excreted (33). The participants in the studies by Deierlein et al. (31) were girls who came from the USA and were predominantly exposed to TCS during their childhood, while both boys and girls during childhood and adolescence were surveyed in other studies. The difference in age and gender may play key roles in the results. Due to few studies have examined the relationship between children exposure to TCS and BMI by different genders, we could not determine the effect of TCS on BMI in children of different genders.

TCS is an environmental endocrine disruptor with antibacterial activity. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals may alter metabolism via estrogenic, antiestrogenic, or antiandrogen action by interfering with other hormone functions (34). However, studies suggest that levels of these chemicals are reasonably stable over time for the purpose of ranking and have acceptable intraindividual variability over more than a year (33). This may explain how exposure to TCS during childhood has no relationship on the children's BMI. Also, exposure to TCS during pregnancy did not effect neonatal birth weight; it was probably due to the placental protection mechanism (35, 36).

Our meta-analysis found that there was no significant association between maternal urinary TCS level during pregnancy and neonatal birth weight, which was consistent with the latest published meta-analysis (37). However, our study had stricter literature inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. We conducted unified classification and screening according to the types of research data and adjustment methods. To explore the reasons for the existence of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis for the results, while Zhong et al. (37) did not. However, the result of our study differs from the article published in June 2020 (38), which showed that exposure to TCS during pregnancy will increase the birth weight of newborns. However, the CI for the results of the study on birth weight crossed zero in the forest plot, indicating that their results were not statistically significant.

The publication bias of a study by Deierlein et al. (31) was significantly greater than the others. We compared the differences between a study by Deierlein et al. (31), and the other two articles, and found that TCS were adjusted for relatively simple covariates including race, age, educational level, socioeconomic status, and baseline BMI, which may explain the asymmetry of the funnel graph.

The strengths of our study were as follows: First, this meta-analysis analyzed the effects of TCS exposure during pregnancy on children and the effects of TCS exposure in children, respectively. Second, subgroup analyses were performed to explore the relationship between TCS exposure and neonatal birth weight by different adjusted methods. Third, the most relevant studies were high-quality prospective cohort studies, which can enhance the credibility of our study. Fourth, in the first meta-analysis to evaluate the relationship between maternal urinary TCS level and neonatal birthweight, we classified the included studies according to the TCS adjusted methods and performed a meta-analysism. In the other studies, urine TCS concentrations were all adjusted for creatinine, and all of these improved the reliability of the results. Finally, we used birth weight as an indicator and referred to a unified calibration method and unit.

Our study also had limitations. First, birth weight and children's BMI may be influenced by other confounding factors, such as other environmental chemicals, mother or child nutrition, mother or child age, and so on. Inadequate adjustment of confounders might cause overestimation or underestimation of the actual effect of exposure to TCS on outcomes. Second, the studies included were generally from the United States, China, and Europe. There was a lack of relevant research in other regions, which may cause regional biases in this study. Third, the two studies of this meta-analysis contained few records, which may lead to unstable results. What's more, all studies included were log or in the transformation of TCS (considerate the abnormal distribution) except for one study that TCS was not converted.

Conclusion

In summary, in our meta-analysis, there was no significant association between exposure to TCS during pregnancy and neonatal birth weight, as well as TCS exposure during childhood on children's BMI. We recommend a broader, larger prospective cohort study to assess the relationship between prenatal TCS exposure and neonatal birth outcomes. In addition, we should pay more attention to TCS exposure during childhood and reduce children's exposure to TCS.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

JL carefully read and screened the literature related to the research direction and collected the data. DC made figures and tables and they were all the main authors of the manuscript. YH polished the language and optimized the format of the first draft. In the process of reviewing the manuscript, the language was checked and polished by FB. TC reviewed and revised the final manuscript and gave advice during the submission process. XW was the final reviewer. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81803259) and the Basic Research Plan of Jiangsu Province (Natural Science Foundation)-Youth Fund Project (Grant No. BK20180682). The funding was used in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Wu Yan. Yun Fan ensured the original data, figures, materials, code, and confirmed that their presentation accurately reflects the original. Weiyue Hu made some changes to the format.

References

1. Ley C, Pischel L, Parsonnet J. Triclosan and triclocarban exposure and thyroid function during pregnancy-A randomized intervention. Reprod Toxicol. (2017) 74:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.09.005

2. Weatherly LM, Gosse JA. Triclosan exposure, transformation, and human health effects. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. (2017) 20:447–69. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2017.1399306

3. Yin J, Wei L, Shi Y, Zhang J, Wu Q, Shao B. Chinese population exposure to triclosan and triclocarban as measured via human urine and nails. Environ Geochem Health. (2016) 38:1125–35. doi: 10.1007/s10653-015-9777-x

4. Heffernan AL, Baduel C, Toms LM, Calafat AM, Ye X, Hobson P, et al. Use of pooled samples to assess human exposure to parabens, benzophenone-3 and triclosan in Queensland, Australia. Environ Int. (2015) 85:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.09.001

5. Wang X, Ouyang F, Feng L, Wang X, Liu Z, Zhang J. Maternal urinary triclosan concentration in relation to maternal and neonatal thyroid hormone levels: a prospective study. Environ Health Perspect. (2017) 125:067017. doi: 10.1289/EHP500

6. Etzel TM, Calafat AM, Ye X, Chen A, Lanphear BP, Savitz DA, et al. Urinary triclosan concentrations during pregnancy and birth outcomes. Environ Res. (2017) 156:505–11. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.04.015

7. Messerlian C, Mustieles V, Minguez-Alarcon L, Ford JB, Calafat AM, Souter I, et al. Preconception and prenatal urinary concentrations of phenols and birth size of singleton infants born to mothers and fathers from the environment and reproductive health (EARTH) study. Environ Int. (2018) 114:60–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.02.017

8. Inokuchi M, Matsuo N, Takayama JI, Hasegawa T. Tracking of BMI in Japanese children from 6 to 18 years of age: reference values for annual BMI incremental change and proposal for size of increment indicative of risk for obesity. Ann Hum Biol. (2011) 38:146–9. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2010.499883

9. Pycke BF, Geer LA, Dalloul M, Abulafia O, Jenck AM, Halden RU. Human fetal exposure to triclosan and triclocarban in an urban population from Brooklyn, New York. Environ Sci Technol. (2014) 48:8831–8. doi: 10.1021/es501100w

10. Abel KM, Wicks S, Susser ES, Dalman C, Pedersen MG, Mortensen PB, et al. Birth weight, schizophrenia, and adult mental disorder: is risk confined to the smallest babies? Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2010) 67:923–30. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.100

11. Moore VM, Davies MJ. Diet during pregnancy, neonatal outcomes and later health. Reprod Fertil Dev. (2005) 17:341–8. doi: 10.1071/RD04094

12. Rich-Edwards JW, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Gillman MW, Hennekens CH, et al. Birthweight and the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in adult women. Ann Intern Med. (1999) 130(4 Pt 1):278–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-4_Part_1-199902160-00005

13. Silva Idos S, De Stavola B, McCormack V. Birth size and breast cancer risk: re-analysis of individual participant data from 32 studies. PLoS Med. (2008) 5:e193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050193

14. Ouyang F, Tang N, Zhang HJ, Wang X, Zhao S, Wang W, et al. Maternal urinary triclosan level, gestational diabetes mellitus and birth weight in Chinese women. Sci Total Environ. (2018) 626:451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.102

15. Geer LA, Pycke BFG, Waxenbaum J, Sherer DM, Abulafia O, Halden RU. Association of birth outcomes with fetal exposure to parabens, triclosan and triclocarban in an immigrant population in Brooklyn, New York. J Hazard Mater. (2017) 323(Pt A):177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.03.028

16. Stacy SL, Eliot M, Etzel T, Papandonatos G, Calafat AM, Chen A, et al. Patterns variability, and predictors of urinary triclosan concentrations during pregnancy and childhood. Environ Sci Technol. (2017) 51:6404–13. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b00325

17. Ding G, Wang C, Vinturache A, Zhao S, Pan R, Han W, et al. Prenatal low-level phenol exposures and birth outcomes in China. Sci Total Environ. (2017) 607–8:1400–7. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.084

18. Philippat C, Botton J, Calafat AM, Ye X, Charles MA, Slama R. Prenatal exposure to phenols and growth in boys. Epidemiology. (2014) 25:625–35. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000132

19. Huo W, Xia W, Wu C, Zhu Y, Zhang B, Wan Y, et al. Urinary level of triclosan in a population of Chinese pregnant women and its association with birth outcomes. Environ Pollut. (2018) 233:872–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.073

20. Lester F, Arbuckle TE, Peng Y, McIsaac MA. Impact of exposure to phenols during early pregnancy on birth weight in two Canadian cohort studies subject to measurement errors. Environ Int. (2018) 120:231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.005

21. Jackson-Browne MS, Papandonatos GD, Chen A, Calafat AM, Yolton K, Lanphear BP, et al. Identifying vulnerable periods of neurotoxicity to triclosan exposure in children. Environ Health Perspect. (2018) 126:057001. doi: 10.1289/EHP2777

22. Kalloo G, Calafat AM, Chen A, Yolton K, Lanphear BP, Braun JM. Early life Triclosan exposure and child adiposity at 8 Years of age: a prospective cohort study. Environ Health. (2018) 17:24. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0366-1

23. Daniels SR, Arnett DK, Eckel RH, Gidding SS, Hayman LL, Kumanyika S, et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation. (2005) 111:1999–2012. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000161369.71722.10

24. Xue J, Wu Q, Sakthivel S, Pavithran PV, Vasukutty JR, Kannan K. Urinary levels of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including bisphenols, bisphenol A diglycidyl ethers, benzophenones, parabens, and triclosan in obese and non-obese Indian children. Environ Res. (2015) 137:120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.12.007

25. Yang Y, Tang R, Qiu H, Lai PC, Wong P, Thach TQ, et al. Long term exposure to air pollution and mortality in an elderly cohort in Hong Kong. Environ Int. (2018) 117:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.034

26. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

27. Yang Y, Zhang D, Feng N, Chen G, Liu J, Chen G, et al. Increased intake of vegetables, but not fruit, reduces risk for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. (2014) 147:1031–42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.005

28. Barili F, Parolari A, Kappetein PA, Freemantle N. Statistical Primer: heterogeneity, random- or fixed-effects model analyses? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2018) 27:317–21. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy163

29. Buser MC, Murray HE, Scinicariello F. Association of urinary phenols with increased body weight measures and obesity in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. (2014) 165:744–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.06.039

30. Li S, Zhao J, Wang G, Zhu Y, Rabito F, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Urinary triclosan concentrations are inversely associated with body mass index and waist circumference in the US general population: experience in NHANES 2003-2010. Int J Hyg Environ Health. (2015) 218:401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.03.004

31. Deierlein AL, Wolff MS, Pajak A, Pinney SM, Windham GC, Galvez MP, et al. Phenol concentrations during childhood and subsequent measures of adiposity among young girls. Am J Epidemiol. (2017) 186:581–92. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx136

32. Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong L-Y, Reidy JA, Needham LL. Urinary concentrations of triclosan in the U.S. Population: 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. (2008) 116:303–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10768

33. Sandborgh-Englund G, Adolfsson-Erici M, Odham G, Ekstrand J. Pharmacokinetics of triclosan following oral ingestion in humans. J Toxicol Environ Health A. (2006) 69:1861–73. doi: 10.1080/15287390600631706

34. Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, et al. EDC-2: the endocrine society's second scientific statement on endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Endocrine Rev. (2015) 36:E1–150. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1010

35. James MO, Li W, Summerlot DP, Rowland-Faux L, Wood CE. Triclosan is a potent inhibitor of estradiol and estrone sulfonation in sheep placenta. Environ Int. (2010) 36:942–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.02.004

36. Wang X, Chen X, Feng X, Chang F, Chen M, Xia Y, et al. Triclosan causes spontaneous abortion accompanied by decline of estrogen sulfotransferase activity in humans and mice. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:18252. doi: 10.1038/srep18252

37. Zhong Q, Peng M, He J, Yang W, Huang F. Association of prenatal exposure to phenols and parabens with birth size: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 703:134720. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134720

Keywords: environmental, urinary, pregnancy, neonatal, epidemiological

Citation: Liu J, Chen D, Huang Y, Bigambo FM, Chen T and Wang X (2021) Effect of Maternal Triclosan Exposure on Neonatal Birth Weight and Children Triclosan Exposure on Children's BMI: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 9:648196. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.648196

Received: 31 December 2020; Accepted: 11 May 2021;

Published: 08 July 2021.

Edited by:

Panagiotis Georgiadis, National Hellenic Research Foundation, GreeceReviewed by:

Theodora Katsila, National Hellenic Research Foundation, GreeceOctavio Jiménez-Garza, University of Guanajuato, Mexico

Copyright © 2021 Liu, Chen, Huang, Bigambo, Chen and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ting Chen, Y2hlbnRpbmdAbmptdS5lZHUuY24=; Xu Wang, c2VwbmluZUBuam11LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jiani Liu

Jiani Liu Danrong Chen

Danrong Chen Yanqiu Huang1,2

Yanqiu Huang1,2 Xu Wang

Xu Wang