- 1Department of Geriatrics, Internal Medicine Residency, East Alabama Medical Center, Opelika, AL, United States

- 2BMJ Case Reports, London, United Kingdom

- 3FAIMER, Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 4Psychiatry Department, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, United States

- 5Anthropology, Hadassah Academic College, Jerusalem, Israel

- 6Faculty for Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Be'er Sheva, Israel

- 7Medical School for International Health, BGU Faculty for Health Sciences, Be'er Sheva, Israel

- 8Open Clinic, Physicians for Human Rights, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 9Department of Geriatrics and Centre for Global Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Be'er Sheva, Israel

- 10Department of Geriatrics, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 11Geriatric Unit, Rambam Health Care Campus, Faculty of Medicine, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel

- 12General and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Ziv Medical Center, Tzfat, Israel

- 13The Azrieli Faculty of Medicine, Bar Ilan University, Tzfat, Israel

- 14Department of Surgery, Galilee Medical Center, Nahariya, Israel

Introduction: The standardization of global health education and assessment remains a significant issue among global health educators. This paper explores the role of multiple choice questions (MCQs) in global health education: whether MCQs are appropriate in written assessment of what may be perceived to be a broad curriculum packed with fewer facts than biomedical science curricula; what form the MCQs might take; what we want to test; how to select the most appropriate question format; the challenge of quality item-writing; and, which aspects of the curriculum MCQs may be used to assess.

Materials and Methods: The Medical School for International Health (MSIH) global health curriculum was blue-printed by content experts and course teachers. A 30-question, 1-h examination was produced after exhaustive item writing and revision by teachers of the course. Reliability, difficulty index and discrimination were calculated and examination results were analyzed using SPSS software.

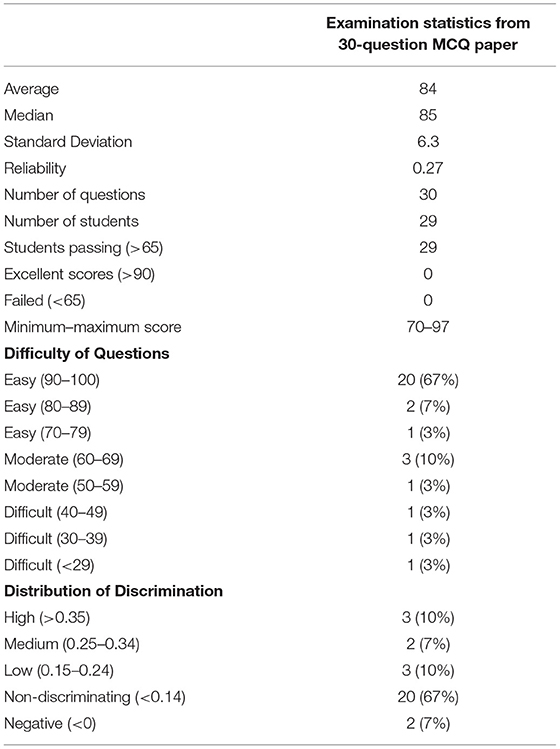

Results: Twenty-nine students sat the 1-h examination. All students passed (scores above 67% - in accordance with University criteria). Twenty-three (77%) questions were found to be easy, 4 (14%) of moderate difficulty, and 3 (9%) difficult (using examinations department difficulty index calculations). Eight questions (27%) were considered discriminatory and 20 (67%) were non-discriminatory according to examinations department calculations and criteria. The reliability score was 0.27.

Discussion: Our experience shows that there may be a role for single-best-option (SBO) MCQ assessment in global health education. MCQs may be written that cover the majority of the curriculum. Aspects of the curriculum may be better addressed by non-SBO format MCQs. MCQ assessment might usefully complement other forms of assessment that assess skills, attitude and behavior. Preparation of effective MCQs is an exhaustive process, but high quality MCQs in global health may serve as an important driver of learning.

Introduction

Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) are the most commonly used tool for assessment in medical education (1, 2). While other tools including short answer questions, long answer questions, oral examinations, and written reports also have an important role in assessment, the vast majority of summative examinations a medical student takes are based on MCQs (1, 3, 4). The popularity of MCQs rests on the ease of testing a breadth of knowledge, standard setting and production of statistical data necessary for quality control of institutional question banks (4–6). Common criticisms of standard MCQs include their failure to engage higher order thinking, test attitude, behaviors or the application of clinical skills, and their failure to take into account gender and cultural biases in question response. Thus, standard MCQs are not generally associated with transformational learning (4, 5, 7). There are, however, a multitude of MCQ styles that may, to varying degrees, test knowledge, skills, attitudes, judgement and even behavior, especially when questions are context-based.

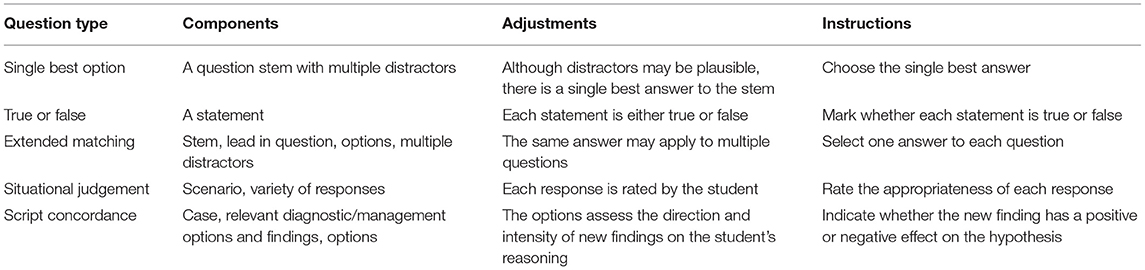

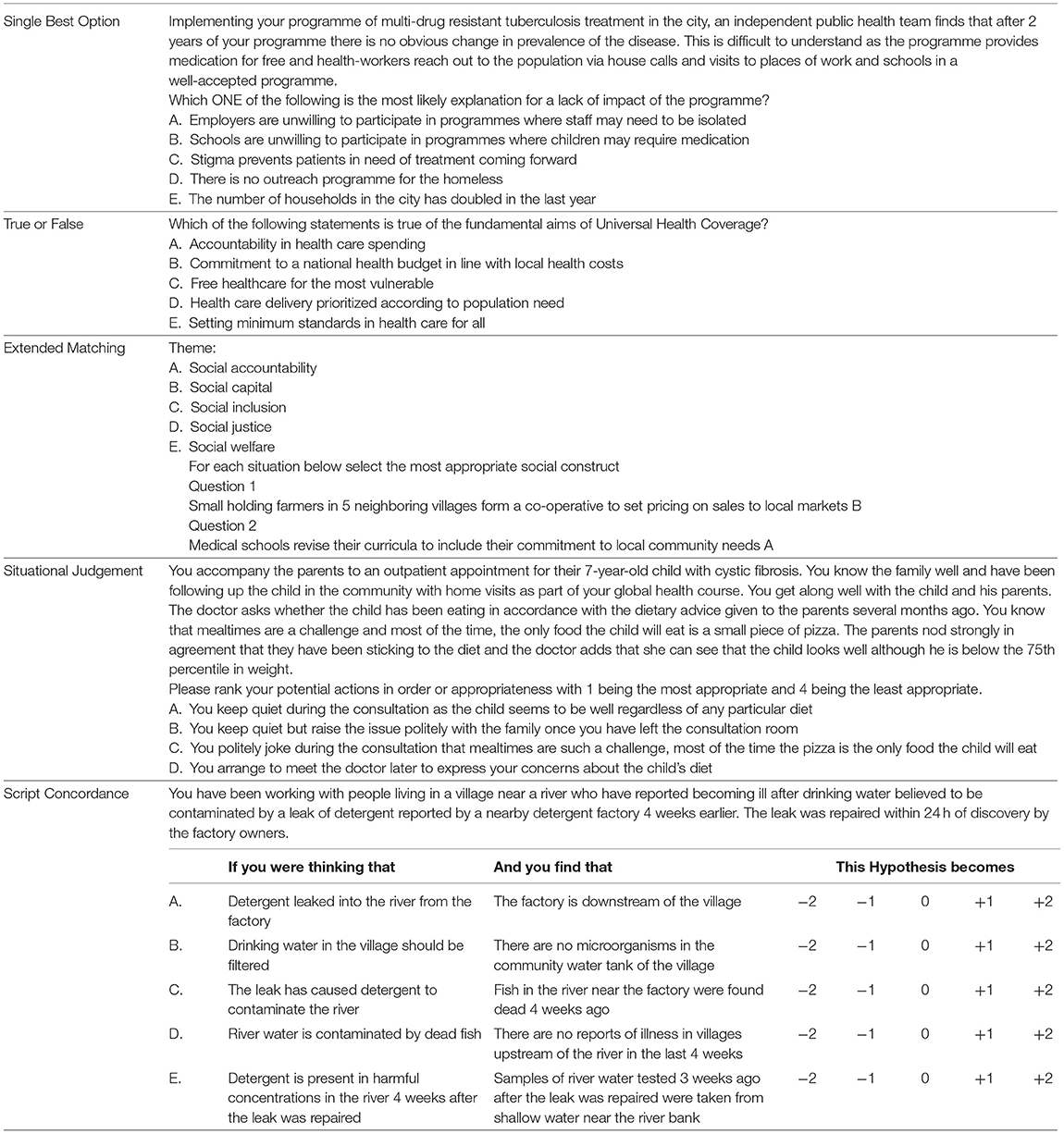

Examples of MCQ style are given in Table 1 below which summarizes the features of each type of question: single best option (SBO); true/false statements; extended matching; situational judgement; and, script concordance questions (8–11). For the most part, SBO style MCQs are used to assess the biomedical curriculum. This is the case in national licensing exams such as the United States Medical Licensing Examination (12).

In comparison to the techniques used for the assessment of the basic sciences, assessment of global health learning is more problematic. While lectures and written learning resources may be rich in factual content, there is a perception among students, and perhaps even faculty, that these facts are not immediately relevant to a scientific medical curriculum, and that a grasp of global health concepts does not necessarily require a recall of facts (13, 14). Thus, many global health programs rely exclusively on reflective essays as assessment tools—focusing on cultural and anthropological exploration, and ethics and overseas medical experience, or on a project thesis that seeks to address a distinct research question in line with Master of Public Health programs (15–17). This is at odds with standard assessment of the biomedical curriculum which substantially requires the demonstration of recall and understanding of specific facts in order to demonstrate competence to practice.

While many medical schools describe their global health learning programs in detail, there is a paucity of research into what students actually learn on these courses. There is evidence that students know far less than they think they do (13, 14, 18, 19). Eichbaum (20) writes of a frenzied growth in global health education programs with poorly defined goals and objectives, describing the need for competency-based programs. Over the last 10 years there have been calls for an agreement on undergraduate global health education frameworks and competencies (21–28). These competencies are similar to those developed by the Joint US/Canadian Committee on Global Health Core Competencies and those discussed in the 2008 Bellagio conference on global health education and include learning about: the global burden of disease; health implications of travel, migration and displacement; social and economic determinants of health; population resources and environment; globalization of health and health care; health care in low-resource settings; and, human rights in global health. The global health competencies of the Medical School for International Health (MSIH), Ben-Gurion University in Be'er Sheva, Israel, mirror these international standards.

Reflective essays alone cannot test the breadth of such curricula and do not reflect the broad range of global health competencies. Moreover, this style of assessment encourages students to view global health as a “soft” science, less of a priority in learning than the traditional disciplines usually covered in the biomedical curriculum, and to overestimate how much they actually know about global health (13, 14, 29).

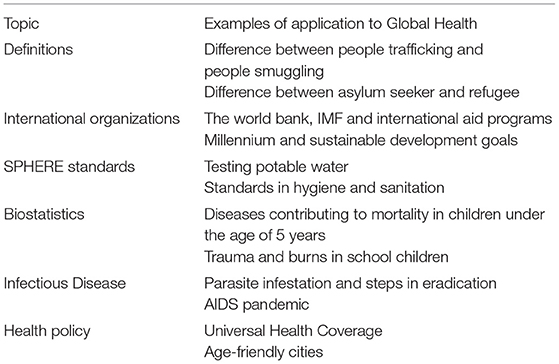

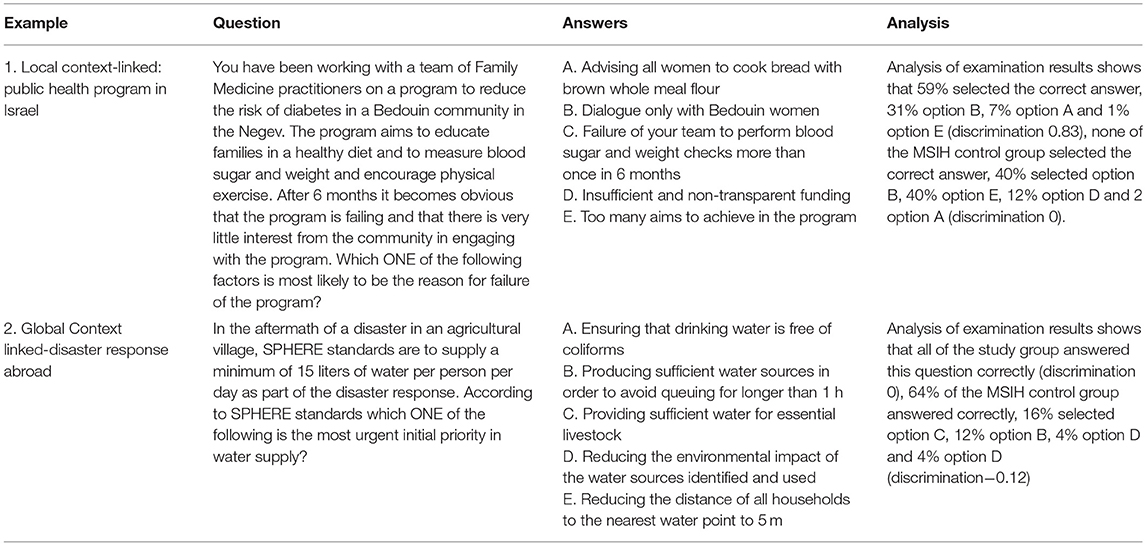

Table 2 gives examples of factual learning outcomes in the global health curriculum. Just as the breadth of the biomedical curriculum may be assessed through a SBO MCQ, we propose that for substantial areas of the global health curriculum SBO MCQs may be a useful assessment tool. Table 3 gives examples of how these learning outcomes might be assessed using different MCQ formats.

In this research we describe the challenges and limitations of devising MCQs for the assessment of knowledge across the global health curriculum and report our experience of SBOs.

Materials and Methods

Context

The Medical School for International Health (MSIH) was founded in 1996 as a collaborative effort between the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Be'er Sheva, Israel, and the Columbia University Medical Center in New York. The goal of the medical school is to produce physicians who are competent international health practitioners (30, 31). Students are mainly from the USA, some are from Canada and a few from outside North America. Teaching and assessment are conducted in English.

As part of a first year global health teaching program review at MSIH we sought to assess global health learning: looking specifically to see how many of the curricular learning outcomes may be taught and learned over a two-semester global health course; and how to assess what has been learned. Changes to the course and assessment were gradual—over, at least, 14 months (spanning two taught courses). The number of guest lectures was reduced from previous iterations of the course and student involvement in local community programs and patient interaction increased on practical placements. Material from practical placements was incorporated into lectures so that, in principle, all students had exposure to the same learning objectives within the curriculum. Learning objectives from published global health competencies were mapped to the teaching curriculum. MCQs were chosen as they were already in widespread use across the biomedical curriculum. A 30-question SBO MCQ examination was designed and administered to students at the end of the course.

Blue Printing the Curriculum

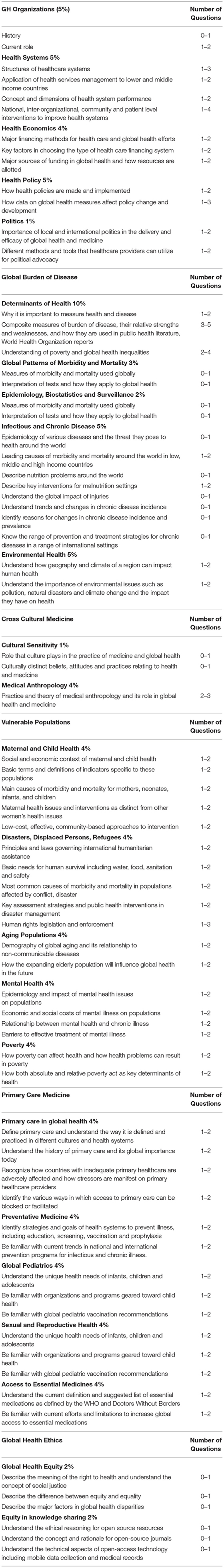

Learning objectives within each section of the global health curriculum were defined and teaching faculty agreed on the weighting of topics within the curriculum in terms of MCQ assessment (Table 4). Teachers prepared learning materials (lectures and discussion topics) with these learning objectives in mind and prepared MCQs based on these objectives.

Item Writing and Testing

MCQs were written by all (four) teachers of the course who taught distinct parts of the curriculum. The SBO format was chosen over the other MCQ styles as there was only one correct answer per question, there was broader agreement on a single correct answer, and questions were deemed less susceptible to guessing. Each question focused on a single learning objective. The final 30 questions chosen out of 100 authored by all teachers of the course were agreed to represent a broad representation of the course material.

The 30 questions were chosen after exhaustive item review. Items were discussed and tested with the faculty (seven teachers from MSIH and four teachers from other faculties), independently (forty medical students in the United Kingdom and seven students in Israel at a different medical school). Criteria for agreement on the final 30 questions comprising the examination were that each question had a meaningful stem free of irrelevant detail, the stem ended with a question, negative phrasing was not used, and that distractors were clear, concise, roughly the same number of words, mutually exclusive and independent of each other. Distractors included common misconceptions discussed in class and were plausible alternatives unless students' precise knowledge of the topics was tested. Any questions with “all/none of the above” or non-heterogeneous distractors were omitted or rewritten. Distractors were listed in alphabetical order.

Data Analysis

Item analysis and exam statistics provided information about the quality of MCQs and difficulty and discrimination index. The aim was to develop questions that would principally test the recall of facts (in particular definitions, criteria and structural frameworks used in global health as in Table 2).

Reliability was based on Kuder-Richardson 21 (testing reliability of binary variables—where an answer is right or wrong when questions do not vary widely in their level of difficulty). We assumed all questions were equal in difficulty and the binary variable was a correct or incorrect answer. Difficulty-index was calculated as follows:

Discrimination was computed by comparing students with the highest score to students with the lowest score.

Results

Examples of multiple-choice questions used in the 30-question examination are seen in Table 3. The MSIH Examinations Department administered and analyzed student performance in the examination using their standard statistical tools and WHO guidelines. One-way ANOVA was applied to detect differences between the student scores using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software. This software was also used to determine discrimination, difficulty and reliability.

Table 5 shows the examination statistics for the 30-question examination. Twenty-nine students sat the 1-h examination. All students passed (scores above 67% as determined by MSIH examinations criteria). Twenty-three (77%) questions were found to be easy, 4 (14%) of moderate difficulty, and 3 (9%) difficult according to the examinations office statistical criteria. Eight questions (27%) were considered discriminatory and 20 (67%) were non-discriminatory. The reliability score was 0.27.

Discussion

The Role of MCQ in Global Health Assessment

The function of assessment has been described as maximizing student competence while guiding subsequent learning. Multiple assessment methods are needed to test all aspects of competence (32). Assessment (or practice for assessment) drives learning. Our experience indicates that identifying ‘factual' aspects of the global health curriculum is possible and that SBO MCQs may be tailored to assess recall and application of these facts. As factual aspects are spread across the curriculum (Table 4), global health MCQs may be employed to assess learning of the breadth of the curriculum just as in the basic sciences. Particular “facts” include definitions, roles of organizations, epidemiological trends in disease prevalence and agreed global standards or health-related goals (Table 2).

We believe that introducing MCQ assessment into a global health curriculum may introduce students to the perception of global health learning as a “hard” science with knowledge and skill competencies in common with the rest of the standard biomedical curriculum. Further, we believe that self-assessment using MCQs may assist students in defining their own learning needs and identify deficiencies in knowledge and competency for practice.

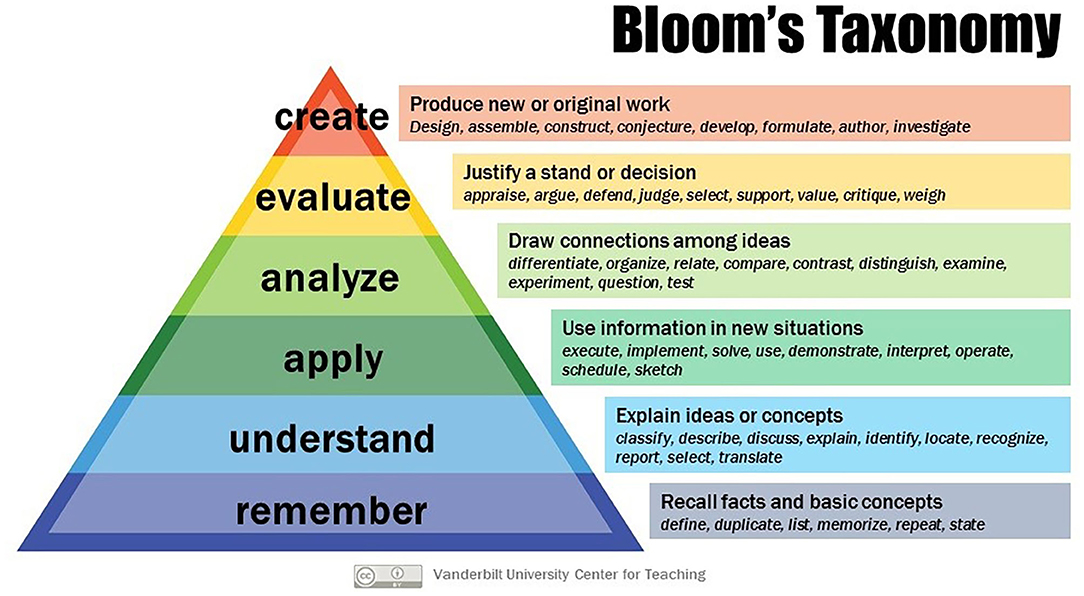

In combination with other assessment modalities based on patient-focused assessment tools such as the global health case report, the MCQ may have a role to play in global health education (33–35). Indeed, MCQs may focus learning in what some students may perceive a rather nebulous and unfocused subject. According to Bloom's taxonomy (Figure 1) MCQ-based assessment may overly emphasize the bottom two phases, “remember,” and “understand,” while neglecting higher orders of learning. Topic selection and item writing, therefore, require careful thought that encourages critical (and reflective) thinking, where possible—using diverse MCQ formats (Table 3) (4, 37–39).

Figure 1. Bloom's taxonomy [Creative Commons, Vanderbilt University. Bloom's Taxonomy. (internet) Vanderbilt University (36). Obtained from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/ on 1/3/2020].

Topics Suitable for MCQ

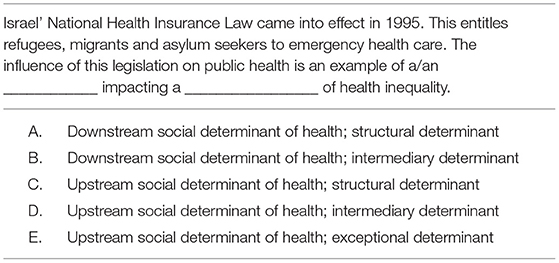

The suitability of SBO MCQs in assessing breadth of knowledge is relevant in global health assessment (4, 40). Few medical fields require as broad a knowledge base as global health. Topics suitable for MCQ assessment must be identified with clear learning and assessment objectives in mind. The process of defining learning objectives, blueprinting, developing the practical course and putting together a final examination to review took 14 months. We were at pains to ensure that we had taught what we planned to assess and assessed what we knew we had taught. Particular emphasis was placed on understanding why distinct definitions exist to describe vulnerable populations and the rights and entitlements these entail, for example (Table 2). While students may feel that they have a grasp of these topics, choosing only one option from a list of distractors forces the student to accept that precise knowledge and understanding of the topics is required to practice safely and access the care their patients require. Table 6 offers an example of a question that we believe tests the application of knowledge and understanding of the social determinants of health.

Item Writing and Quality Control

Writing “good” global health questions is a challenge that requires multiple contributors of questions, exhaustive criticism and review. MCQs should be based on a blueprint of the curriculum and test topics most suited to MCQ-style assessment. We emphasized context as students were encouraged to learn global health on practical placements as well as lectures (41). Our aim is to better engage students (providing real-life experience of global health problems patients experience) and make assessment relevant to future clinical practice. Epstein (6) explains that “questions with rich descriptions of the clinical context invite the more complex cognitive processes that are characteristic of clinical practice. Conversely, context-poor questions can test basic factual knowledge but not its transferability to real clinical problems.” Thus, we believe that context-based questions may place potentially abstract global health concepts in practical, realistic settings relevant to students, easier to identify, recall, and apply knowledge.

Although reliability may have been improved by increasing the number of test items in the exam, we opted for a 30-question examination so that the assessment would be completed within 1 h. We selected 30 questions that represented the breadth of the curriculum and our blueprint. A greater spread of scores with more moderately difficult questions (Difficulty Index 0.4–0.8) and discriminatory questions, would also have been preferable.

Limitations

The most obvious deficiency in this research is that the examination was run only once, and exam questions subjected to statistical analysis only once. This substantially limits any conclusion regarding reliability and validity. Clearly testing needs to be repeated. The research period (a 3-year PhD program that included the running of the global health course) precluded repeated testing. Also important is the development of other styles of MCQs to evaluate their role in the assessment of attitudes and behaviors expected of global health practitioners. We have since increased our bank of questions and written MCQs in other formats better suited to testing judgement, decision making and situational awareness. Examples are given in Table 7. Further testing and analysis of all formats of MCQs for global health teaching and learning is planned.

Conclusion

Global health curricula now have internationally agreed defined competencies and learning objectives (42). As medical teaching worldwide becomes increasingly standardized, there is a need to define precise measures of assessment of student learning that may be used in combination with existing assessment tools such as reflective essays or case reports. We propose further development of MCQs in their diverse formats and testing so that we may determine, not simply their utility in testing what has been learned, but how this knowledge may be applied in the practice of doctors who study global health.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ben Gurion University IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SB designed and researched the material. SB and ND wrote the article. SB, KM, MA, and M-TF wrote the questions. JN, AC, TD, ES, and IW evaluated the questions. All co-authors were involved in revising the article for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

This work was supported in part by funding from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev for SB's PhD thesis work.

Conflict of Interest

SB is editor-in-chief of BMJ Case Reports which publishes Global Health case reports. ND is an associate editor of BMJ Case Reports.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students, faculty and colleagues who participated in the item-writing and testing process, the MSIH examinations department, and the students who participated in this course and sat the examination.

References

1. Grainger R, Dai W, Osborne E, Kenwright D. Medical students create multiple-choice questions for learning in pathology education: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1312-1

2. Kilgour JM, Tayyaba S. An investigation into the optimal number of distractors in single-best answer exams. Adv Health Sci Educ. (2016) 21:571–85. doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9652-7

3. Mehta B, Bhandari B, Sharma P, Kaur R. Short answer open-ended versus multiple-choice questions: a comparison of objectivity. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci. (2016) 52:173–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712619

4. Javaeed A. Assessment of higher ordered thinking in medical education: multiple choice questions and modified essay questions. MedEdPublish. (2018). 7. doi: 10.15694/mep.2018.0000128.1

5. Farooqui F, Saeed N, Aaraj S, Sami MA, Amir M. A comparison between written assessment methods: multiple-choice and short answer questions in end-of-clerkship examinations for final year medical students. Cureus. (2018) 10:e3773. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3773

6. Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. (2007) 356:387–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054784

7. Palmer EJ, Devitt PG. Assessment of higher order cognitive skills in undergraduate education: modified essay or multiple choice questions? Research paper. BMC Med Educ. (2007) 7:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-49

8. Fournier JP, Demeester A, Charlin B. Script concordance tests: guidelines for construction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2008) 8:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-18

9. Patterson F, Zibarras L, Ashworth V. Situational judgement tests in medical education and training: research, theory and practice: AMEE Guide No. 100. Med. Teacher. (2016) 38:3–17. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1072619

10. Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. Written assessment. Br Med J. (2003) 22:643–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7390.643

11. van Bruggen L, Manrique-van Woudenbergh M, Spierenburg E, Vos J. Preferred question types for computer-based assessment of clinical reasoning: a literature study. Pers. Med. Educ. (2012) 1, 162–171. doi: 10.1007/s40037-012-0024-1

12. Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME). Step 1: Question Formats. (2020). Available online at: https://www.usmle.org/step-1/#question-formats (accessed on February 1, 2020).

13. Bozorgmehr K, Menzel-Severing J, Schubert K, Tinnemann P. Global Health Education: a cross-sectional study among German medical students to identify needs, deficits and potential benefits (Part 2 of 2: Knowledge gaps and potential benefits). BMC Med Educ. (2010) 10:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-67

14. Bozorgmehr K, Schubert K, Menzel-Severing J, Tinnemann P. Global Health Education: a cross-sectional study among German medical students to identify needs, deficits and potential benefits (Part 1 of 2: mobility patterns andamp; educational needs and demands). BMC Med Educ. (2010) 10:66. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-66

15. Aulakh A, Tweed S, Moore J, Graham W. Integrating global health with medical education. Clin Teach. (2017) 14:119–23. doi: 10.1111/tct.12476

16. Moran D, Edwardson J, Cuneo CN, Tackett S, Aluri J, Kironji A, et al. Development of global health education at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine: a student-driven initiative. Med Educ Online. (2015) 20:28632. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28632

17. Rowson M, Smith A, Hughes R, Johnson O, Maini A, Martin S, et al. The evolution of global health teaching in undergraduate medical curricula. Global Health. (2012) 8:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-8-35

18. Rosling H. The joy of facts and figures. Bull World Health Organ. (2013) 91:904–5. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.031213

19. Schell CO, Reilly M, Rosling H, Peterson S, Mia Ekström A. Socioeconomic determinants of infant mortality: a worldwide study of 152 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Scand J Public Health. (2007) 35:288–97. doi: 10.1080/14034940600979171

20. Eichbaum Q. The problem with competencies in global health education. Acad Med. (2015) 90:414–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000665

21. Ablah E, Biberman DA, Weist EM, Buekens P, Bentley ME, Burke D, et al. Improving global health education: development of a global health competency model. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2014) 90:560–5. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0537

22. Arthur MA, Battat R, Brewer TF. Teaching the basics: core competencies in global health. Infect Dis Clin North Am. (2011) 25:347. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2011.02.013

23. Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, Chanda MY, Nehme J, Hulme J, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ. (2010) 10:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94

24. Cole DC, Davison C, Hanson L, Jackson SF, Page A, Lencucha R, et al. Being global in public health practice and research: complementary competencies are needed. Can J Public Health. (2011) 102:394–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03404183

25. Harmer A, Lee K, Petty N. Global health education in the United Kingdom: a review of University undergraduate and postgraduate programmes and courses. Public Health. (2015) 129:797–809. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.12.015

26. Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V, Evert J, Fields E, Hall T, et al. Identifying interprofessional global health competencies for 21st-century health professionals. Ann Global Health. (2015) 81:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.03.006

27. Margolis CZ. Carmi Z Margolis on Global Health Education. (2009). Available online at: http://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/bellagio-center/conferencesand-residencies/17709 (accessed on February 1, 2020).

28. Peluso MJ, Encandela J, Hafler JP, Margolis CZ. Guiding principles for the development of global health education curricula in undergraduate medical education. Med Teach. (2012) 34:653–8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687848

29. Blum N, Berlin A, Isaacs A, Burch WJ, Willott C. Medical students as global citizens: a qualitative study of medical students' views on global health teaching within the undergraduate medical curriculum. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1631-x

30. Margolis CZ, Deckelbaum RJ, Henkin Y, Baram S, Cooper P, Alkan ML. A medical school for international health run by international partners. Acad Med. (2004) 79:744–51. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00005

31. Willott C, Khair E, Worthington R, Daniels K, Clarfield AM. Structured medical electives: a concept whose time has come? Glob Health. (2019) 15, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0526-2

32. Moghaddam AK, Khankeh HR, Shariati M, Norcini J, Jalili M. Educational impact of assessment on medical students' learning at Tehran University of Medical Sciences: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e031014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031014

33. BMJ. Global Health. BMJ Case Reports. (2020). Available online at: https://casereports.bmj.com/pages/global-health/ (accessed on February 3, 2020).

34. Biswas S. Writing a global health case report. Student BMJ. (2015). 23:h6108. doi: 10.1136/sbmj.h6108

35. Douthit NT, Biswas S. Global health education and advocacy: using BMJ case reports to tackle the social determinants of health. Front Publ Health. (2018) 6:114. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00114

36. Vanderbilt University. Bloom's Taxonomy. (2020). Available online at: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/ (accessed March 1, 2020).

37. Kerry VB, Ndung'u T, Walensky RP, Lee PT, Kayanja VFI, Bangsberg DR. Managing the demand for global health education. PLoS Med. (2011) 8:e1001118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001118

38. Leinster S. Evaluation and assessment of social accountability in medical schools. Med Teach. (2011) 33:673–6. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.590253

39. Wilkie RM, Harley C, Morrison C. High level multiple choice questions in advanced psychology modules. Psychol Learn Teaching. (2009) 8:30–6. doi: 10.2304/plat.2009.8.2.30

40. Elstein AS. Beyond multiple-choice questions and essays: the need for a new way to assess clinical competence. Acad Med. (1993) 68:244–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199304000-00002

Keywords: global health, medical education, multiple-choice questions, assessment, single-best option

Citation: Douthit NT, Norcini J, Mazuz K, Alkan M, Feuerstein M-T, Clarfield AM, Dwolatzky T, Solomonov E, Waksman I and Biswas S (2021) Assessment of Global Health Education: The Role of Multiple-Choice Questions. Front. Public Health 9:640204. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.640204

Received: 10 December 2020; Accepted: 11 June 2021;

Published: 22 July 2021.

Edited by:

Shazia Qasim Jamshed, Sultan Zainal Abidin University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Mary Thompson, Alson Ltd, United KingdomJeff Bolles, University of North Carolina at Pembroke, United States

Copyright © 2021 Douthit, Norcini, Mazuz, Alkan, Feuerstein, Clarfield, Dwolatzky, Solomonov, Waksman and Biswas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Seema Biswas, eic.bmjcases@bmj.com

Nathan T. Douthit

Nathan T. Douthit John Norcini3,4

John Norcini3,4 Michael Alkan

Michael Alkan A. Mark Clarfield

A. Mark Clarfield Tzvi Dwolatzky

Tzvi Dwolatzky Igor Waksman

Igor Waksman Seema Biswas

Seema Biswas