- 1Department of Critical Care Medicine, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 2Department of Neurosurgery, Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Intensive Care Unit, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China

- 4Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, China

- 5Department of Neurosurgery, Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Chengdu, China

- 6Emergency Intensive Care Unit, Xuzhou Central Hospital, Xuzhou, China

- 7Neurocritical Care Unit, Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

- 8Department of Neurosurgery, The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, China

Objective: To understand the impact of COVID-19 epidemic on the mental health status of intensive care unit (ICU) practitioners in China, and to explore the relevant factors that may affect the mental health status of front-line medical workers so as to adopt efficient and comprehensive measures in a timely manner to protect the mental health of medical staff.

Methods: The study covered most of the provinces in China, and a questionnaire survey was conducted based on the WeChat platform and the Wenjuanxing online survey tool. With the method of anonymous investigation, we chose ICU practitioners to participate in the investigation from April 5, 2020 to April 7, 2020. The respondents were divided into two groups according to strict criteria of inclusion and exclusion, those who participated in the rescue work of COVID-19 (COVID-19 group) and those who did not (non-COVID-19 group). The SCL-90 self-evaluation scale was used for the evaluation of mental health status of the subjects.

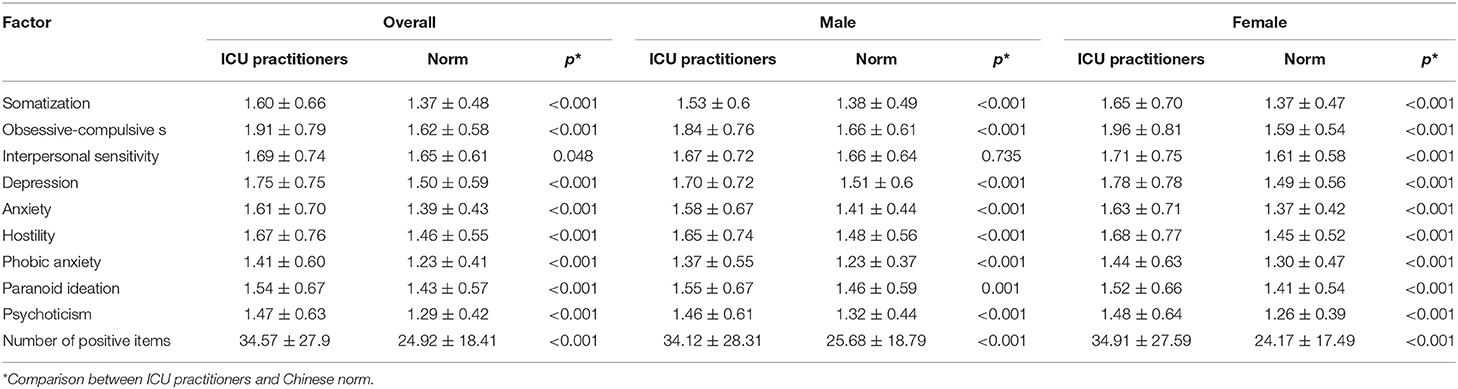

Results: A total of 3,851 respondents completed the questionnaire. First, the overall mental health status of the targeted population, compared with the Chinese norm (n = 1,388), was reflected in nine related factor groups of the SCL-90 scale, and significant differences were found in every factor in both men and women, except for the interpersonal sensitivity in men. Second, the overall mental health of the non-COVID-19 group was worse than that of the COVID-19 group by the SCL-90 scale (OR = 1.98, 95% CI, 1.682–2.331). Third, we have revealed several influencing factors for their mental health in the COVID-19 group, current working status (P < 0.001), satisfaction of diet and accommodation (P < 0.05), occupational exposure (P = 0.005), views on the risk of infection (P = 0.034), and support of training (P = 0.01).

Conclusion: The mental health status of the ICU practitioners in the COVID-19 group is better than that of the non-COVID-19 group, which could be attributed to a strengthened mentality and awareness of risks related to occupational exposure and enforced education on preventive measures for infectious diseases, before being on duty.

Introduction

The year 2020 was disrupted by a sudden pandemic outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which was first reported in Wuhan, China (1), and it is becoming an emerging, rapidly evolving situation. According to the official website of WHO, over 160 million people have been confirmed to have a COVID-19 infection globally by the end of May 25, 2021 (2). Until now, COVID-19 is still raging in much of the world as global cases hit record highs. We have accumulated much knowledge about the COVID-19, including the virus information, clinical features, and diagnosis, but there is no effective treatment (3–5). There is extreme fear over the COVID-19 among the general public because of the strong infectivity, fast transmission, and non-specific manifestations (6). Harsh protective measures have been put in force in real-life practice. Surprisingly, surveys after the outbreak of epidemic have found that most patients who were diagnosed usually have only mild pain or moderate mental problems, including depression (DEP), anxiety (ANX), stigma, and sorrow (7). However, medical health workers are the front-line fighters to treat COVID-19 patients, facing a high risk of infection every day. In order to combat the outbreak, they need to work overtime under a stressful mentality. In short, they are under a kind of enduring pressure that risks to exceed their coping ability (8). Everyone knows that attention should be paid to the mental health of medical workers during the fight against COVID-19 (9, 10), and some reports have been made on the mental health of medical workers after the outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Zhang et al. conducted a survey on the psychosocial problems of both medical and non-medical health workers during the COVID-19 outbreak (11). They found that medical health workers had psychosocial problems and risk factors for developing them. A report conducted in Wuhan found that poor mental status and sleep quality were common among frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak (12). However, there are some limitations in the sample size and sampling representativeness of these studies. Hence, in this study, we aim to understand the impact of COVID-19 epidemic on the mental health status of intensive care unit (ICU) practitioners nationally and to explore the relevant factors that may affect the mental health status of front-line medical workers so as to take measures to protect the mental health of medical staff as quickly and comprehensively as possible.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional online survey performed based on WeChat platform and Wenjuanxing (a platform providing functions equivalent to Amazon Mechanical Turk) from April 5 to April 7, 2020, which basically was the stable stage of COVID-19 epidemic in China. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No. 20200211). The informed consent part was at the front of the questionnaire, and the participants who received the questionnaire had the right to refuse to answer.

Study Population

In China, the usage rate of WeChat could reach 100% medical staff in almost every department as each unit has its own WeChat group. A lot of information about departments and hospitals was sent through the WeChat group, and the questionnaires were distributed to the working group by the directors of the provincial and local hospitals. All the subjects were essential medicine practitioners, and there were no non-professionals among them. However, some people may be unwilling to fill in the questionnaire; besides, the representative sample covered the whole country and could provide relevant and supportive data. Third, the questionnaire was based on a Wenjuanxing platform and distributed by WeChat. Quality control falls into consideration since program design that participants are required to answer all the questions. Meanwhile, Wenjuanxing could set a time-frame in case of answering the questionnaire. This study had a preliminary investigation phase (small sample), when the authors evaluated the reasonable time setting of answering the questionnaire, but was not recorded in the final statistics (i.e., answers made out of the opening hours would be ruled out), the survey of COVID-19 would expire over time, and the sample size collected during the opening hour had reached the expectation.

With the method of anonymous investigation, ICU practitioners from most of the provinces in China were recruited in the study. The respondents who completed all questions of the online survey were divided into two groups according to strict criteria of inclusion and exclusion—those who participated in the rescue work of COVID-19 (anti-COVID-19 group) and those who did not (non-anti-COVID-19 group).

Inclusion criteria included the following: (a) Critical care medical practitioners, including doctors, nurses, and respiratory therapists; (b) Personnel in China, including 23 provinces, five autonomous regions, and four municipalities directly under the central government, excluding two special administrative regions of Hong Kong and Macau; (c) In-service personnel.

Exclusion criteria included (d) Those who did not answer the questionnaire in the opening hours; (e) Exceeding the time limit for questionnaire; (f) incomplete answering of the questionnaire.

Measurements

Information collected via survey questions were demographic data, i.e., gender, age, occupation (doctors, nurses, and others), education status (community college, bachelor, master, and doctor), marital status (married, unmarried, and other), professional title, department (ICU, surgical department, internal medicine, pneumology department, etc.), medical working time, having siblings or children, religious belief, having participated in public health emergency treatment before or not, and directly participating in COVID-19 antiepidemic work or not. Symptom check list-90 (SCL-90) (13) was used to check the mental health status of the subjects, including somatization (SOM), obsessive–compulsive (OC), interpersonal sensitivity (IS), DEP, ANX, hostility (HOS), phobic anxiety (PHOB), paranoid ideation, and psychoticism (PSY). It is a 90-item self-report scale with items to be rated on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 “not at all” to 5 “extremely”).

Outcome Definition

The statistical index of SCL-90 mainly consists of two indicators, namely total score (score range: 90–450) and factor score (score range: 1–5). Any subscale score of all above nine factors ≥2 indicate potential psychological issues (14). The number of positive items referred to the number left in the 90 questions at excluding “No” answers (score ≥2). Number of negative items referred to the number of items with a score of 1, indicating the subject does not experience the symptom. A positive result is the total score of SCL-90 ≥160 or positive items >43.

Reliability and Validity

Internal consistency of the SCL-90 score (Chinese version) was assessed by Cronbach's α and an average interitem correlation. Cronbach's α for summary score of 0.70–0.80 is considered satisfactory for a reliable comparison between groups, and more than 0.90 is required for clinical usefulness of the instrument (15).

Statistical Analysis

The respondents who completed all questions of the online survey were divided into two groups according to strict criteria of inclusion and exclusion. They are those who participated in the rescue work of COVID-19 (anti-COVID-19 group) and those who did not (non-anti-COVID-19 group). The measurement variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and by U-test the scores of SCL-90 factors of the ICU practitioners were compared with the Chinese norm, which is currently used in China and translated by Dang et al. (16). Frequency (%) was used for counting variables, and the Chi-square or Fisher method was used for intergroup comparison. Logistic multivariate regression was used to analyze the influence factors of the positive symptom of SCL-90 score, and the OR value was estimated. In the multivariate analysis, all features of the subjects were forced to be included in the model as independent variables, and on this basis, stepwise regression was carried out. The probability value of the stepwise regression in the setting of independent variables inclusion and removal was 0.05. The software used for statistical analysis was SAS 9.3. Both groups were tested bilaterally. When P < 0.05, the difference was considered statistically significant.

Patient and Public Involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design and conduct of the study.

Results

General Characteristics of ICU Practitioners During COVID-19 Epidemic

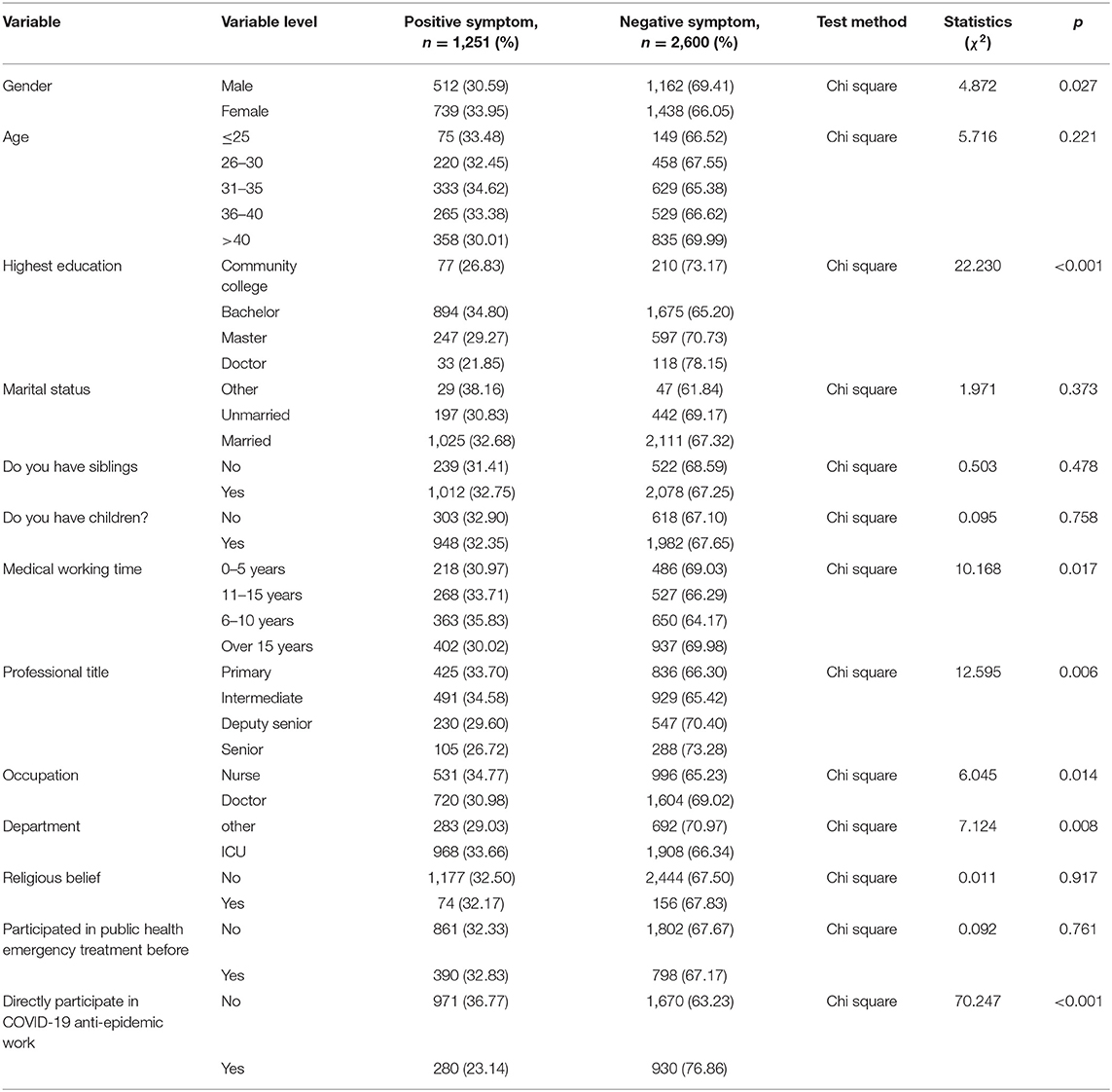

A total of 3,851 ICU practitioners [1,527 nurses (39.65%) and 2,324 doctors (60.35%)] participated in this questionnaire survey. Most of them were from the ICU (74.68%). Out of the total, 1,210 (31.42) people were directly involved in the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic. The age, educational background, professional title, marriage, and other general characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

Table 2 showed the current working status of the workers directly participating in the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic. There were 995 (82.23%) who had finished the anti-COVID-19 work and had been in the succeeding period or back to work, and the other 215 (17.77%) were still in the rescue work. About two-thirds of the participants had worked for more than a month in the fight against the COVID-19 epidemic. More than half of the people were satisfied with their diet and accommodation during the epidemic, whereas only a minority (2.23–3.22%) was dissatisfied. About 65.45% believed that the training they had received in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases was adequate in both theory and practice. In comparison, a minority (1.40%) believed that the theory was inadequate and poor in operability. Moreover, the proportion who thought they were at high risk of infection at work reached 43.88%. The proportions of suspicious occupational exposure and infection caused by occupational exposure were 36.61 and 9.42%, respectively. During the antiepidemic period, the weekly working hours were generally substantial, with about half of the staff working more than 40 h per week, and 8.02% working more than 80 h.

Table 2. The positive symptom ratio of SCL-90 score in ICU practitioners with different characteristics.

SCL-90 Score and Positive Symptom Rate of ICU Practitioners

The Cronbach's alpha of every factor was over 0.85, indicating the high reliability and validity. The mean SCl-90 score of all the participants in this survey was 147.84 ± 58.45. Compared with the Chinese norm, the scores of eight factors of SOM, OC, DEP, ANX, HOS, PHOB, paranoid ideation, and PSY of the male and female ICU practitioners were both higher than those of the norm except for IS (P < 0.001). In terms of IS, the male and female ICU practitioners were different by comparison with the norm, with no significant difference was found in males (p = 0.735). By contrast, the score of female ICU practitioners was still higher than the norm (p < 0.001). The mean positive number of the 90 symptoms among ICU practitioners was 34.57 ± 27.90, which was also significantly higher than the Chinese norm population. The results are shown in Table 1.

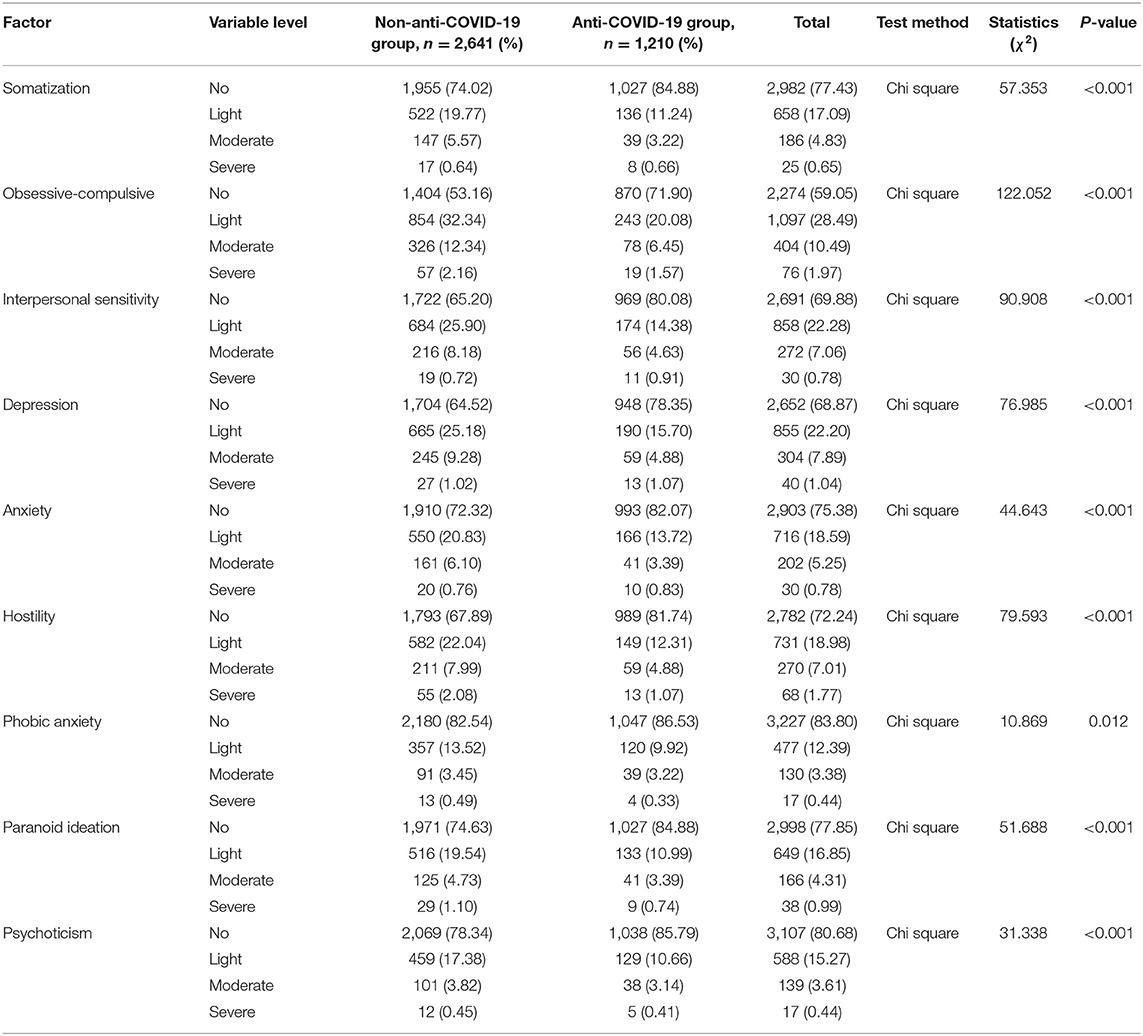

According to the total score of SCL-90, the overall positive symptom rate of ICU practitioners was 32.49% (95% CI: 31.01–33.96). Unifactorial analysis revealed that women, intermediate education (bachelor's degree), intermediate working time (6–15 years), lower professional title, nurse occupation, being from ICU, and those who did not directly participate in COVID-19 epidemic had higher positive symptom rate (p < 0.05), as shown in Table 2. The characteristics of ICU practitioners were taken as independent variables, and the factors affecting positive symptoms of SCL-90 score were selected by stepwise logistic multivariate analysis, including education background, professional title, department, whether participating in the treatment of public health emergencies, and whether directly participating in antiepidemic work. The risk of positive symptoms of the SCL-90 score increased by 98% (OR = 1.98, 95% CI, 1.682–2.331) among those who did not directly participate in the antiepidemic program. The symptoms of those who directly participated in the antiepidemic program were all less severe in the nine factors, including SOM, OC, IS, DEP, ANX, HOS, PHOB, paranoid ideation, and PSY, as displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of SCL-90 scoring factors between anti-COVID-19 group and non-anti-COVID-19 group.

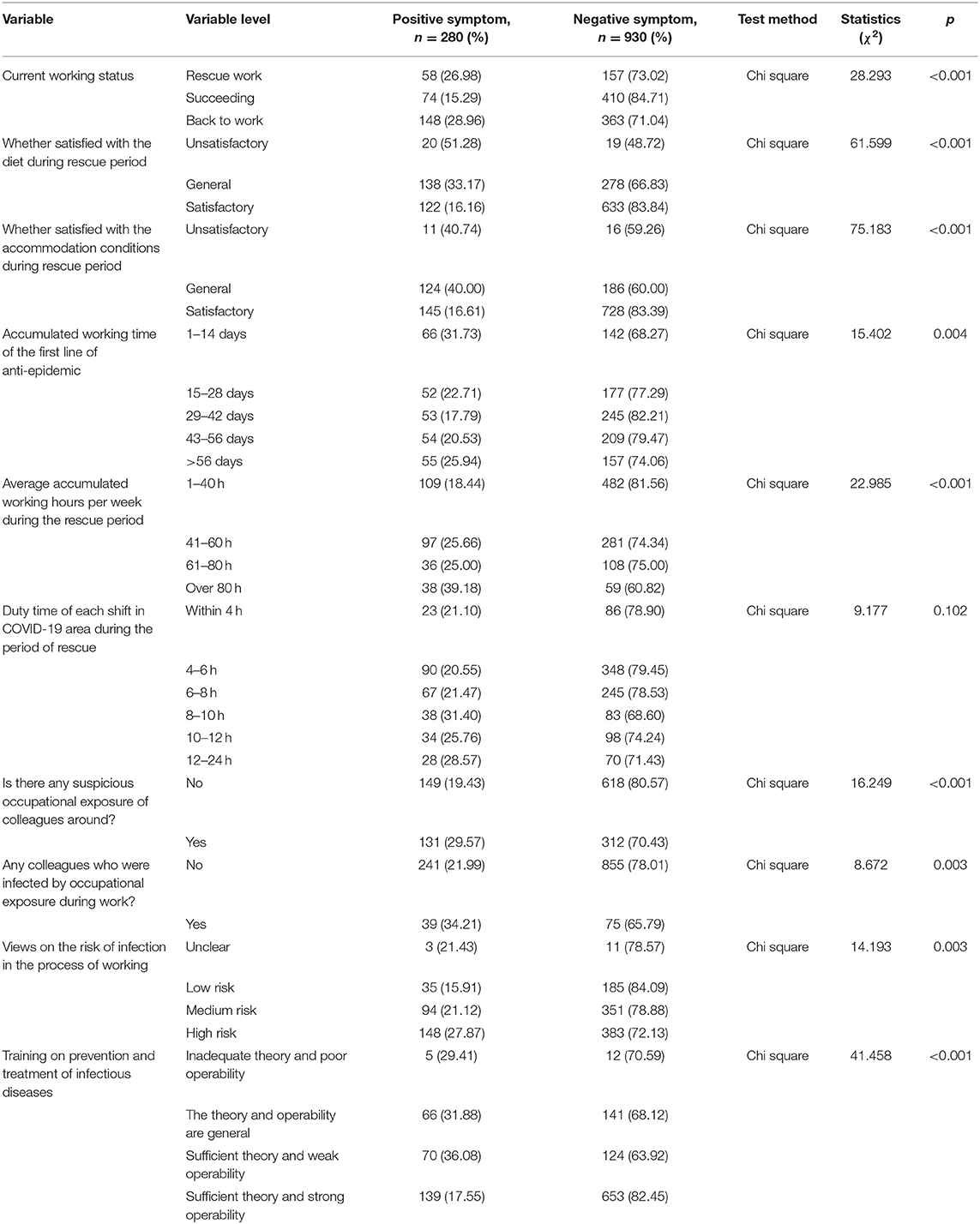

The Influence of Working Conditions on SCL-90 Score During Anti-COVID-19 Epidemic

The overall positive rate of SCL-90 for the anti-COVID-19 epidemic ICU practitioners was 23.14% (95% CI: 20.76–25.52), and the lowest positive rate was 15.29% for the succeeding period. The more satisfied the diet and accommodation during the epidemic, the lower the positive symptom rate. During the period of fighting the epidemic, the longer the average weekly cumulative working hours, the higher the positive rate of symptoms, and the positive rate of those working more than 80 h per week reached 39.18%. The rate of positive symptoms was the highest (31.73%) within 2 weeks of participating in the anti-COVID-19 epidemic campaign. The rate was stable (about 20%) within 2–7 weeks, and there was a small increase (25%) over 8 weeks. The rate of positive symptoms was significantly higher when surrounding colleagues had suspected occupational exposure or were infected by occupational exposure (p < 0.001). The two kinds of people who thought their risk of being infected in the period not high, that who thought they had received sufficient training of theory and practice on infectious disease protection and treatment. They had significantly lower positive symptom rate than others, as shown in Table 4. The work status of the ICU practitioners participating in the antiepidemic campaign was taken as an independent variable. The factors influencing the positive symptom of SCL-90 score were screened by stepwise logistic multivariate analysis, including current work status, diet, accommodation, infection status of the surrounding colleagues, work infection risk, protection, and treatment training, as shown in Table 5.

Table 4. The proportion of positive symptoms with SCL-90 score among the people directly participate in COVID-19 anti-epidemic work.

Table 5. Multi-factor analysis of positive symptom of SCL-90 score of people directly participate in COVID-19 anti-epidemic work.

Discussion

This cross-sectional survey enrolled 3,851 respondents and revealed worse conditions of mental health by SCL-90 scale among ICU practitioners compared with the Chinese norm. Moreover, we found that the overall mental health of the COVID-19 group was better than that of the non-COVID-19 group by the SCL-90 scale, which might be due to a state of full feelings and sense of responsibility in the face of the epidemic plus the satisfactory diet and accommodation as well as adequate training on prevention and control of infectious diseases.

Previous studies have shown that COVID-19 has an adverse psychological impact on ordinary citizens during the level I emergency response period through the SCL-90 (17). Compared with the general public, medical health workers, including doctors and nurses, working in front-line clinical positions are the main force for hospitals to complete the task of medical security, but also face a higher risk of infection and intense mental pressure during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Compared to the mental health status of the Chinese norm, the ICU practitioners during the COVID-19 epidemic had higher rates of SOM, OC symptoms, DEP, ANX, HOS, terror, paranoia, and psychosis based on SCL-90 score, in both men and women. In terms of interpersonal relationship sensitivity, no significant difference was found in men, but women were found to be sensitive. According to previous studies, results have indicated gender difference, while men tend to be less inter-personally sensitive than women because women typically remember more emotional information than men (18, 19), which may explain this result. The mean positive numbers among the 90 symptoms of ICU practitioners were also significantly higher than the Chinese norm population, indicating that the ICU practitioners face higher risk of mental health problems, which should be given more attention and support by the whole society.

A study on the mental health of medical and nursing staff in Wuhan reported that among 994 medical and nursing staff, 36.9% had subthreshold mental health disturbances, 34.4% had mild disturbances, 22.4% had moderate disturbances, and 6.2% had severe disturbance in the immediate wake of the viral epidemic (20). Another online survey showed that the prevalence of DEP, ANX, insomnia, and distress symptoms were 50.7, 44.7, 36.1, and 73.4%, respectively, among frontline healthcare workers in China (21). Based on this study, health authorities, academic institutions and societies in China rapidly developed various measures and responses including, education materials and programs, 24 h hotline services, on-site crisis psychological interventions, and relevant research (12). Consequently, the prevalence of psychiatric problems among frontline healthcare workers gradually declined in subsequent studies (22).

In the current study, both unifactorial and logistic multivariate analysis showed that educational background, professional title, department, and whether directly participating in antiepidemic work could likely contribute to a higher positive symptom rate. The risk of positive symptoms of the SCL-90 score increased by 98% among those who did not directly participate in the antiepidemic program. Moreover, the symptoms of those who directly participated in the antiepidemic program were all less severe in the nine factors. The reasons for the psychological distress of medical health workers might be related to the many aspects during COVID-19 epidemic, such as insufficient understanding of the virus, the lack of prevention and control knowledge and equipment, the long-term workload, the high risk of exposure to patients with COVID-19 (23, 24), and the exposure to critical life events (25), such as death. However, from the results, we found that the mental health status of those who directly participated in the antiepidemic was not more severe than those who did not, but was even better. This is not consistent with our hypothesis before the investigation. We assume this could be explained by the following explanations: first, during our investigation period, the domestic epidemic had been basically at a steady stage. Many front-line personnel had returned to their original posts, or even though they were still working in the front-line, the most severe stage had already passed, and their psychological state was relaxed to varying degrees. Second, the mentality of those who voluntarily participated (most of whom were Party members) in the rescue work was strong and well-prepared. Third, those medical workers who participated in the rescue work got enough training about the knowledge of COVID-19 and received sufficient protection equipment. Indeed, no doctor (out of 40,000 medical personnel) from other provinces was infected with COVID-19 during their aid period in Hubei Province (26). Finally, a strong sense of social responsibility and encouragement from the whole society and family played spiritual pillars, which supported them to overcome fear and hesitation, leaving them staying in a healthier mental status. Other incentives or policies from government and institutions may act as a supportive factor in improving their mental health.

Many factors affect the positive symptom rate for participants in the epidemic. From the study, we found that the more the doctors were satisfied with the diet and accommodation, the less likely they would develop positive symptoms. In addition, the average weekly cumulative working hours is also correlated with the rate of positive symptoms. These are in accordance with the results we expected. The rate of positive symptoms was significantly higher when surrounding colleagues had suspected occupational exposure or were infected by occupational exposure. Medical health workers might worry about being infected because different workplaces require different medical skills to tackle different medical conditions. In addition, multivariate analysis screened many factors, including current work status, diet and accommodation conditions, infection status of surrounding colleagues, work infection risk, protection and treatment training, that could influence the SCL-90 score of positive symptom. The results indicate that Chinese government and medical institutions should make various efforts to reduce the pressure on medical and nursing staff, such as sending more medical and nursing staff to reduce work intensity, adopting strict infection control, providing personal protective equipment, offering practical guidance as well as improving their working environment.

This study has some limitations. First, a cross-sectional design was applied to investigate the short term mental health influence of COVID-19; however, long term impact, especially posttraumatic stress disorder, might occur as the COVID-19 proceeds. Second, psychological assessment was only based on online survey and self-reporting tool, and there may be some deviation. Moreover, WeChat is adopted as the tool to distribute questionnaire, where selection, reporting and response bias may exist. At last, our survey was made in the basically stable stage of COVID-19 epidemic in China, and mental health status was only at a moderate level, and it was not for those who were at higher risk.

In conclusion, the overall mental health status of the ICU practitioners is worrying. In addition, among the ICU practitioners, the mental health status in the COVID-19 group is better than that of the non-COVID-19 group, and the reasons may vary. Moreover, for the medical workers in the COVID-19 rescue operation, we should select those who have enough related experience and provide them adequate health protection training and better working conditions to enhance their resilience and psychological well-being.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical Committee of Beijing Tongren Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained by all study participants.

Author Contributions

WC, WH, and DZ conceived and designed the experiments. WC, WH, XL, SK, and LZ performed the experiments. WH, WC, TP, XW, and RR analyzed the data. WC and WH wrote the paper. WC and DZ revised the paper. All authors had reviewed and agreed on the contents of this paper.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants in this survey.

References

1. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

2. World Health Organization. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/

3. Chen L, Li Q, Zheng D, Jiang H, Wei Y, Zou L, et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with Covid-19 in Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:e100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009226

4. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. (2020) 579:270–3. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7

5. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. (2020) 30:269–71. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

6. Ji D, Ji YJ, Duan XZ, Li WG, Sun ZQ, Song XA, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and healthcare workers during the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:12784–91. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14498

7. Kamara S, Walder A, Duncan J, Kabbedijk A, Hughes P, Muana A. Mental health care during the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Sierra Leone. Bull World Health Org. (2017) 95:842–7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.190470

8. Fava GA, McEwen BS, Guidi J, Gostoli S, Offidani E, Sonino N. Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2019) 108:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.028

9. Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. (2020) 395:e37–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3

10. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, Chen M, Yang C, Yang BX, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e14. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X

11. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosomatics. (2020) 89:242–50. doi: 10.1159/000507639

12. Zhou Y, Ding H, Zhang Y, Zhang B, Guo Y, Cheung T, et al. Prevalence of poor psychiatric status and sleep quality among frontline healthcare workers during and after the COVID-19 outbreak: a longitudinal study. Transl Psychiatry. (2021) 11:223. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01190-w

13. Chen S, Li L. Re-testing reliability, validity, and norm applicability of SCL-90. Chin J Nerv Ment Dis. (2003) 29:117–21. doi: 10.1007/s11769-003-0089-1

14. Chen X, Li P, Wang F, Ji G, Miao L, You S. Psychological results of 438 patients with persisting gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms by symptom checklist 90-revised questionnaire. Euro J Hepato Gastroenterol. (2017) 7:117–21. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1230

16. Dang W Xu Y, Ji J, Wang K, Zhao S, Yu B, Liu J, et al. Study of the SCL-90 scale and changes in the chinese norms. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 11:524395. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.524395

17. Tian F, Li H, Tian S, Yang J, Shao J, Tian C. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 288:112992. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112992

18. Hall JA, Murphy NA, Mast MS. Recall of nonverbal cues: exploring a new definition of interpersonal sensitivity. J Nonverbal Behav. (2006) 30:141–55. doi: 10.1007/s10919-006-0013-3

19. Bloise SM, Johnson MK. Memory for emotional and neutral information: gender and individual differences in emotional sensitivity. Memory. (2007) 15:192–204. doi: 10.1080/09658210701204456

20. Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 87:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028

21. Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

22. Zhou Y, Zhou Y, Song Y, Ren L, Ng CH, Xiang YT, et al. Tackling the mental health burden of frontline healthcare staff in the COVID-19 pandemic: China's experiences. Psychol Med. (2020). doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001622. [Epub ahead of print].

23. Central steering group: over 3 000 medical staff in Hubei were infected in the early stage of the epidemic currently no infection reports among medical aid staff. Guangming Online. Beijing (2020). Available online at: https://politics.gmw.cn/2020-03/06/content_33626862.htm

24. World Health Organization. Shortage of Personal Protective Equipment Endangering Health Workers Worldwide. Geneva (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protectiveequipment-endangering-health-workersworldwide

25. Theorell T. Evaluating life events and chronic stressors in relation to health: stressors and health in clinical work. Adv Psychosom Med. (2012) 32:58–71. doi: 10.1159/000330004

26. In January Hubei had more than 3 000 medical infections and the Wuhan Health and Medical Committee reported “none” for half a month. SINAnews. Beijing (2020). Available online at: https://news.sina.com.cn/o/2020-03-06/dociimxyqvz8395569

Keywords: COVID-19, ICU practitioners, mental health, SCL-90, intervening measure

Citation: He W, Chen W, Li X, Kung SS, Zeng L, Peng T, Wang X, Ren R and Zhao D (2021) Investigation on the Mental Health Status of ICU Practitioners and Analysis of Influencing Factors During the Stable Stage of COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Front. Public Health 9:572415. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.572415

Received: 14 June 2020; Accepted: 05 July 2021;

Published: 18 August 2021.

Edited by:

Jutta Lindert, University of Applied Sciences Emden Leer, GermanyReviewed by:

Muhammad Salman, University of Lahore, PakistanReina Granados, University of Granada, Spain

Copyright © 2021 He, Chen, Li, Kung, Zeng, Peng, Wang, Ren and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Di Zhao, MTc5MzgxNzQ5QHFxLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wei He1†

Wei He1† Di Zhao

Di Zhao