94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Public Health , 08 June 2021

Sec. Public Health Policy

Volume 9 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.553980

This article is part of the Research Topic Implementing Public Health Policy Initiatives View all 7 articles

Realist evaluation is making inroads in the field of health policy and systems research to a large extent because of its good fit with complex issues. Until now, most realist studies focused on evaluating interventions or projects related to health care delivery, organization of health services, education, management, and leadership of health workers in high income countries. With this paper, we apply the realist approach to the study of national health policy implementation in a low resource country. We use the case of the user fee exemption policy for cesarean section in Benin, which we followed up from 2009 to 2018. We report on how realist evaluation can be applied for policy implementation research. We illustrate how we developed the initial programme theory—the starting point of any realist evaluation -, how we designed the study and data collection tools, and how we analyzed the data. For each step, we present current good practices, how we adapted them when needed, the challenges and the lessons learned. We report also on how the dynamic interactions between the central level (the national implementing agency) and the peripheral level (an implementing hospital) shaped the policy implementation. We found that at central level, availability of resources for a given policy is constantly challenged in the competitive national resource allocation arena. Key factors include the political power and the legitimacy of the group supporting the policy. These are influenced by the policy implementation structure, how the actual outputs of the implementation align with promises of the group supporting the policy and consequently how these outputs, the policy and its promoters are perceived by the community. We found that the service providers are key to the implementation, and that they are constrained or influenced by the dependability of the funding, their autonomy, their personal background, and the accountability arrangements. This study can inform the design and implementation of national health policies that involve interactions between central and operational level in other low-income countries.

The realist methodology, which includes realist synthesis, realist evaluation and realist research, is increasingly acknowledged as an appropriate approach to address complex problems in health policy and system research. Health policy and systems research seeks to “understand and improve how societies organize themselves in achieving collective health goals, and how different actors interact in the policy and implementation processes to contribute to policy outcomes” (1). As such, health policy and systems research deals with problems that are mostly complex by nature as they often involve many actors operating in organizations that are embedded in larger systems. Policy actors are often confronted with uncertainty about the issue at hand and the potential solutions, which, to complicate matters further, are context-dependent (1).

The complex nature of many policy issues challenges the ontological, epistemological and methodological foundations of biomedical and clinical research traditions (2). Pawson and Tilley (3) argued that because of their successionist model of causation, these approaches fall short in explaining the complex causal processes underlying policy decisions and policies in general. Realist methodologies provide an alternative model that is rooted in generative causation (4). Compared with the successionist model that attributes outcomes to an intervention on the basis of demonstrating through statistical techniques a constant conjunction between the two, realists seek to identify the mechanisms that underlie change in outcomes, and the influence of context in order to produce a causal explanation. It is increasingly used in health system research (5–10), but little so far in the domain of policy implementation research.

Policy implementation research looks at how governments put policies into effect (11). This field emerged in the 1970s in the United States and has known a number of shifts (12). The first generation adopted a top-down approach, “a conception of implementation as the hierarchical execution of centrally-defined policy intentions” [(13), p. 89]. Wildavsky and Pressman (14), seminal authors in this field, reported the implementation failure of a United States federal employment policy for minorities in Oakland. With others authors, like Derthick (15) and Bardach (16), they succeeded in making the case for implementation as a critical step in the policy cycle, but these authors did not focus on explaining the reported challenges (13). In response, the bottom-up approach to policy implementation emerged with authors like Lipsky (17), Elmore (18), Ingram (19), or Hjern and Hull (20). Hjern and Porter [(21), p. 216] analyzed the implementation outcomes of federal policies on manpower training in Germany and Sweden and showed how “implementation structures (…) formed by the initiative of individuals in relation to a programme” are important factors. The second generation views implementation as “the everyday problem-solving strategies of ‘street-level bureaucrats’” [(13), p. 89], focusing on local agencies more than on central-level officials. A vivid debate between top-down and bottom-up proponents ensued. Third generation authors like Sabatier (22) and Goggin (23) aimed to transcend this debate with “hybrid theories” that combine aspects from top-down and bottom-up approaches. Elmore (24) used forward mapping (starting with implementation and reasoning up to the outcomes) and backward mapping (starting from the outcomes and reasoning back to the decision) to show how actions of both central-level officials and local actors are complementary in shaping policy implementation outcomes.

The fourth generation took a different starting point. Indeed, by the 1990s, emerging market-based policy instruments were a central focus of policy implementation studies in the United States. The concept of multicentricity of power gained prominence, creating room for the fourth generation of policy implementation research with authors like Pierre and Peters (25), Honig (26), Ostrom (27), van Hulst and Yanow (28), and Pfadenhauer et al. (29). This generation is grounded in concepts like neo-institutionalism, institutional arrangements, networks, policy culture, and their complex interactions (12).

Policy making is indeed complex (11). It starts from the moment a policy idea emerges and makes its way to the policy agenda. Policy formulation is a key step in the process of putting the policy into effect, as actors involved or excluded from this process will influence the likelihood that the policy will be adopted by a critical mass of stakeholders (11). Multiple actors at various positions are involved, with specific power positions and interests. Policy actors belong to (in)formal networks and organizations, and often combine different roles and positions in society. Policy implementation is a multi-level process wherein mechanisms are generated at macro-level (federal or national level), meso-level (organizational and local level) and micro-level (individuals and groups within organizations or communities). Context matters as well as feedback loops between mechanisms playing out at different levels. Policy implementation is thus in essence a dynamic process (6, 30). Any change among the actors, the policy instruments, or the political, economic or social dimensions of the policy process can affect implementation outcomes (6, 31). The fourth generation of policy implementation research acknowledges the complex nature of the policy implementation process, which in turn led to particular conceptual and methodological challenges that realist methodologies may be able to address (32).

The objective of this paper is to illustrate the application of the realist evaluation approach to the study of policy implementation gaps, in casu related to the user fee exemption policy for cesarean section in Benin. For each step of the study, from eliciting the initial programme theory to formulating the refined programme theory, we will present the current common practices and how we adopted or adapted these to research topic.

With the decree N° 2008-730 of 22nd December 2008, President Yayi Boni introduced the user fee exemption policy for cesarean section in Benin. From April 2009 onwards, it was applied by 43 state-owned and non-state-owned hospitals. Pregnant women requiring a cesarean section were exempted from paying for a benefit package including referral within the health district, intravenous infusion, consultation fees, all surgical procedures, drugs and medical consumables, hospitalization, and post-operative check-up. The central implementing agency was assigned the role of checking the volume of cesarean sections declared monthly by the implementing hospitals for eligibility and of reimbursing the implementing hospitals a lump sum of XOF 100,000 (US$196) per cesarean section. We described the agenda setting and policy formulation process, and the significant variations in policy implementation, in a previous paper (33).

Realist research proceeds in iterative cycles that start and end with the formulation of a programme theory (3, 7). The initial programme theory can be elicited using various avenues. Using “documentary analysis, interviews and library searches,” realists can draw upon “documents, programme architects, practitioners, previous evaluation studies, and social science literature” (3).

In our study, we built the initial programme theory on the results of a literature review, previous studies on the policy, and personal experience. We started with the literature review aiming at identifying theories, frameworks and models that would help explaining health policy implementation gaps. We specifically searched for publications on maternal health care fee exemption policies in sub-Sahara Africa. We used the “berry-picking” approach (34), combining searching of electronic bibliographic databases, footnote chasing and author searching (35). We found that few publications presented or discussed theories, analytical frameworks or models. In response, we extended our search to the field of public policy and policy implementation, which yielded a number of potential programme theories. In a next step, we organized brain storming sessions with the research team members to think through how the user fee exemption policy would lead to its effects and under which conditions. At that stage, we reviewed policy documents, conducted non-participant observations of policymakers' and implementers' meetings, and conducted interviews with the policymakers and implementers in order to elicit their assumptions and folk-theories on policy implementation, and to identify the political economy dynamics underlying the user fee exemption policy for cesarean section in Benin (33). Finally, we carried out two realist research studies. The first investigated the adoption of the policy by the managers of implementing hospitals and the implementation by health workers. It used a multiple embedded case study design in two hospitals with contrasting policy implementation outputs. It allowed us to formulate a refined programme theory (36) which was tested in a second study (Publication forthcoming). The second study investigated the policy process at the macro- (or national) level, using a single case study design. The unit of analysis was the national level institutional arrangements for the policy implementation from 2009 to 2018. This process summarized in Figure 1 led to the programme theory presented in Figure 2.

For the current study, we explored the importance of the top-down design of the policy, a rather natural phenomenon in Benin's bureaucratically organized health system, in which the central level of the Ministry of Health sets out the policy directions and formulates the actual programme to be implemented by the health districts and hospitals. We focused on the interaction between the central level (arrangements governing the implementing agency) and the managers of the peripheral level (the implementing hospital), considering the dynamic nature of the implementation and the changes in context conditions and over time. We further explored the role of the contractual relationship between the national implementing agency and the implementing hospitals, the financial flows, and the conditions of enforcement. In this study, for clarity we used the terms “central level” and “peripheral level” as they describe better the field of this research as compared to “macro-level” and the “meso-level,” respectively.

In realist research, the study design follows from the initial programme theory and the research question (3). In our study, we adopted a multiple embedded case study design (37). We defined the case as the actual implementation of the user fee exemption policy for cesarean section. We focused on two units of analysis (Table 1), which we followed from 2009 to 2018. The first unit of analysis is located at central level: it is the set of institutional arrangements governing the Agence nationale de la gratuité de la césarienne, hereafter called “the implementing agency,” which is in charge of the implementation of the policy. The second unit of analysis is situated at peripheral level and is the implementation of the policy in a state-owned district hospital (hereafter referred to as “the hospital”) with a focus on the hospital managers who play a critical role in the policy implementation. The hospital is a district-level hospital with around 120 beds. It operates an emergency, internal medicine, surgery, pediatric and maternity ward, a pharmacy, a medical imaging unit, and a laboratory with blood transfusion capacity. The maternity ward provides a complete package of emergency obstetric and neonatal care. More recently, an intensive care, a neonatal care, an ophthalmology and a physiotherapy unit were opened. It serves a district with a mix of urban and rural zones, with a population that grew from 264,000 inhabitants in 2005 to about 385,500 inhabitants in 2018. We selected this hospital purposively in function of availability and quality of data for the period of interest on the dimensions of the initial programme theory.

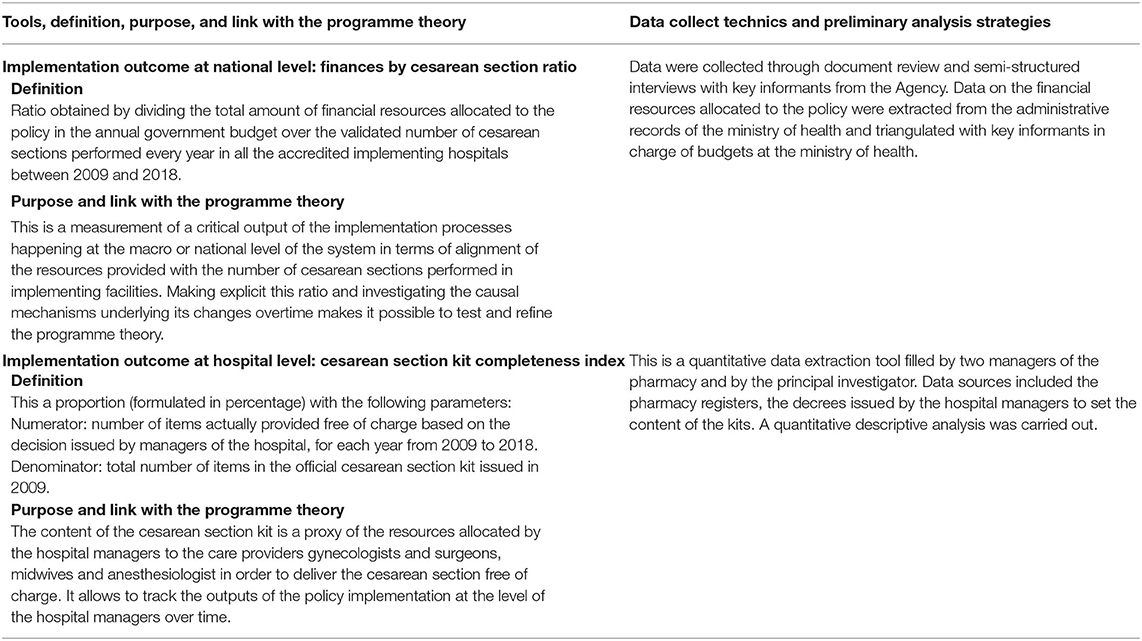

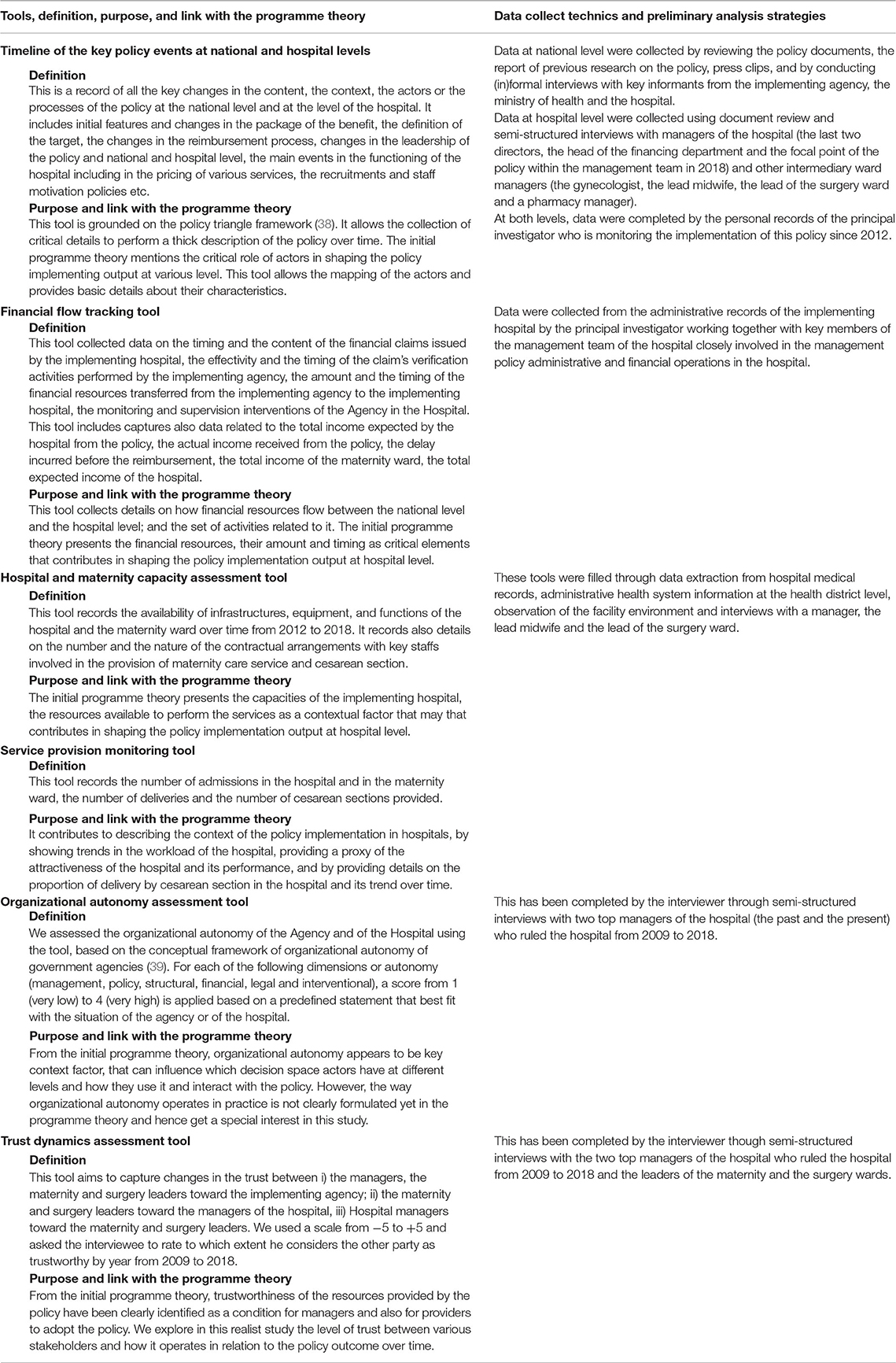

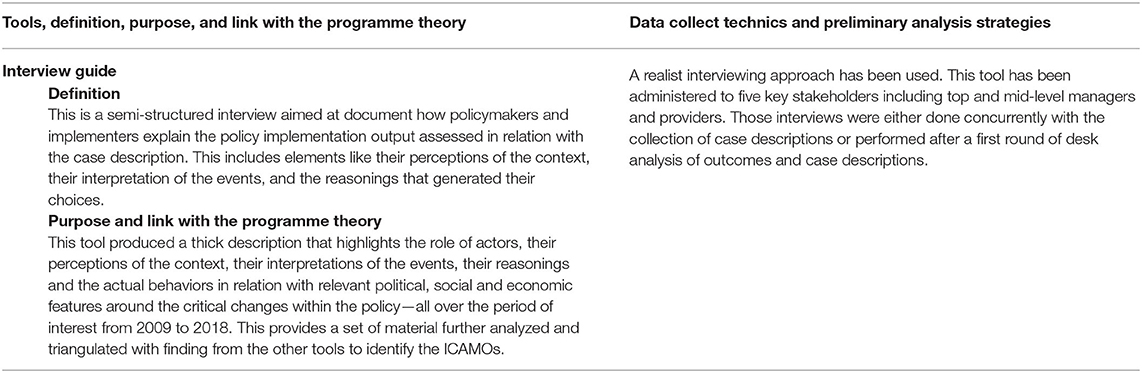

Realist evaluation is method neutral (3): realists set out to collect any data enabling the “testing” of the initial programme theory. In our study, we identified three categories of data: data required to (i) assess the outcome (see Table 2); (ii) describe the case (see Table 3); and (iii) explore the reasonings of the actors in order to identify the mechanisms (see Table 4). Data were collected in three rounds (2012, 2016, and 2018). We present the definition, the purpose and the links to the programme theory as well as the data collection and preliminary analysis strategies in Tables 2–4.

Table 2. Tools to assess the policy outcome at various levels: definition, purposes, link with the programme theory, data collection technics, and preliminary analysis strategies.

Table 3. Tools to describe the policy in its context: definition, purpose, link with the programme theory, data collect technics, and preliminary analysis strategies.

Table 4. Tools to explore the reasonings of actors: definition, purpose, link with the programme theory, data collect technics, and preliminary analysis strategies.

Realist research is characterized by a configurational approach to analysis: starting from assessing the outcome, realists explore the causal pathway that led to these outcomes. Typically, the Context-Mechanism-Outcome heuristic is used to guide the data analysis process (3). The end point of the analysis is a causal statement that explains how an intervention or policy triggered mechanisms among specific actors which led to the observed outcomes in specific context conditions.

In this study, we used the Intervention-Context-Actor-Mechanism-Outcome (ICAMO) heuristic, which aims at making the role of actors more explicit and facilitates a more nuanced distinction between context and intervention (40). We defined mechanisms as “reasoning” of actors interpreting and responding to the “resources” provided by the programme and/or by other interventions in a given context (3).

The analysis started during the field work, whereby the first author actively started to make sense of the data while collecting them, compare initial findings to the initial programme theory and adapting the data collection when needed. Once all data were collected, the qualitative data were imported in NVIVO 12 for Mac and coded. We adopted thematic analysis principles (41) whereby the initial coding tree was based on the key themes of the initial programme theory. This coding tree evolved during the analytical process as new themes were added. We identified the ICAMO configurations by triangulating data from the various sources, using the retroductive approach, in which the researcher starts from the observed events to identify and postulate the conditions without which these events cannot exist (42). Multiple conjectural ICAMOs emerged, which were compared and checked against the data, leading to consolidation of an ICAMO configuration that provided the most plausible explanation of the observed outcomes.

A realist study ends with a refined programme theory, which results from a careful abstraction of the consolidated ICAMO configurations to the level of the initial programme theory, which is then adapted if needed (3).

We present first the findings of our study in the next section and present then the “translation” of the empirical results to the level of the refined programme theory.

In this section, we first describe the policy implementation outputs and the practices of policy makers and implementers related to the policy with focus on the two units of analysis. This is followed by a description of the ICAMO configurations we identified.

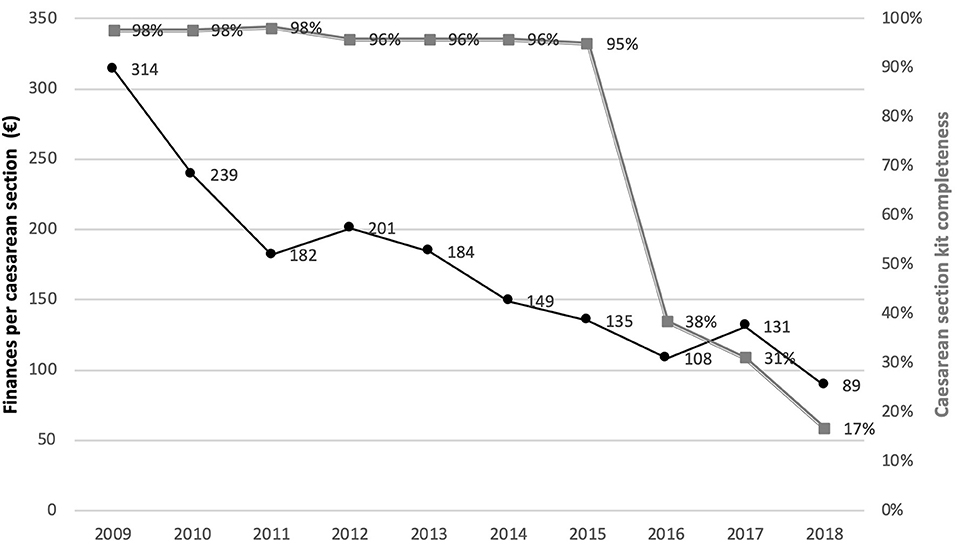

The fee exemption policy set out to reduce the financial barriers to access and use of maternal health services, specifically as related to cesarean sections. At the level of the implementing agency, we found that the amount of financial resources allocated to the policy as well as the actual rate for reimbursing a cesarean section dropped consistently over time (see black and single line in Figure 2).

We used the completeness of the cesarean section kit as a proxy for policy implementation output at the level of the hospital. The cesarean section kit should contain the full set of drugs and consumables that is required for a cesarean section. Under the policy, the kit is free. In practice, women pay for missing drugs and consumables. The more complete the kit, the lower the cost of the cesarean section. At the level of the district hospital, our analysis showed that there were two phases. Between 2009 and 2015, we found the kits were quite complete, but between 2016 and 2018, the kits contained only between 17 and 38% of the items (double gray line on Figure 3).

Figure 3. Trend of the financial resources allocated to the policy per cesarean section (at the central level) and cesarean section kit completeness in the implementing hospital (at the peripheral level) between 2009 and 2018.

Our analysis showed that this hospital was not much used by the community between 2005 and 2009, before the fee exemption policy was introduced. Our respondents mentioned that the community considered the availability and quality of services in the hospital to be sub-optimal. The community members voiced several complaints and exerted pressure that culminated in the period 2008–2009.

In 2009, the management team was led by “M1.” He was dedicated to the hospital's providers, prioritized their well-being, and tended not to question the decisions of the hospital's specialists. We found he perceived the policy as an opportunity to meet the community's demands for better availability of services and quality of care. He considered that the policy is

“a state policy for vulnerable women; to do otherwise (not adopting the policy), you will be socially frowned upon. For your hierarchy, it is a disobedience and we tried to sustain it for the happiness of the policy targets.” (Semi-structured interview, Hospital manager, Male, 2012)

From 2009 to 2015, the government reimbursed the hospital on a regular basis. M1 found that the reimbursement process during the initial phase of the policy implementation was fast and easy. He was comforted by the positive feedback he received from the Implementing Agency, who considered the Hospital as a good pupil in terms of policy implementation. When asked about the role of trust in implementing the policy, the hospital managers reported they live in a “forced trust” relationship with the state, since they are managing a state-owned hospital. The timing of the reimbursement determined the trust of M1 in the state, and as indicated in Table 2, the trust index of the hospital's managers remained high during this period.

Based on the perceived steady revenue, M1 attracted new gynecologists and surgeons. Contracted by the hospital, the specialists were engaged to work a given number of hours per week; in return, the hospital agreed to pay them a fixed fee of €46 per 24 h and an extra fee linked to the number of surgical procedures they performed. For a cesarean section for instance, this extra fee corresponds to 20% of the €76 fee charged for the surgical act. The number of staff performing cesarean sections in the hospital increased from three in 2008 to eight in 2011. The number of deliveries doubled between 2008 and 2012, and the proportion of delivery by cesarean section increased from 33.3% in 2009 to 69% in 2011. The overall utilization of the hospital increased as the total number of admissions increased from 2.980 in 2008 to 4.839 in 2011.

Several interviewees reported that the community's perceptions about the hospital improved and they found the hospital had become more attractive. As a manager reported:

“The providers were motivated, they were working well, and the hospital was working. The population was satisfied with this strategy since patients were treated without delay. The fame of the hospital skyrocketed. So, there was a gain for the providers, a gain for us who manage the system and a gain for the population.” (Semi-structured interview, Hospital manager, 2018)

An important champion of the policy since inception in 2009 was President Yayi Boni (elected in 2006, re-elected in 2011). Several technical staff of the Ministry of Health, health providers and community representatives portrayed the strong personal support from the president as a means to seek popular support for re-election in 2011. This is in line with our finding that prior to his re-election in 2011, the President used the policy as a campaign argument, presenting it as a successful social programme of his first mandate.

At the level of the implementing agency, from 2009 and up to 2013, the terms and obligations of the relationship between the central implementation agency and the hospital were not clearly formulated, and the contract was not signed. In 2013, the Agency introduced a system of contracting implementing facilities in response to reports of hospitals that still charged fees for items that were supposed to be free. The contract enforced the benefit package defined in the Policy decree and specified that the Agency has to reimburse the Hospital within 20 days after the validation of the claims for reimbursement. The contract also stated that in case a hospital is found to charge fees, administrative and criminal sanctions would be raised and the Hospital would be required to pay back these fees. In practice, our data show that from 2014 onwards, important delays were observed in the reimbursement of the Hospital by the Agency. In our interviews, managers of the Hospital declared they were not surprised by this failure, and that this situation reinforced their feeling of being forced to implement the policy. On the other hand, we found that during this period, no procedures were initiated to monitor the fees and that hospitals still charged patients.

Related to the intervention, we found that sufficient financial resources were provided regularly at predictable moments (I). The monitoring from the implementing agency (Actors) focused on checking the expenses claimed; the actual user fee removal was not monitored (I). The personal engagement of the president signaled very high political support for the policy (Context). There were no other policy or initiatives with similar goals that needed funding (Context). Ministry of Health staff (A) questioned the relevance and sustainability of the policy but as civil servants, they considered it their duty to comply to governmental policy (O). This was enhanced by their perception that the policy would generate popular support toward the political regime in place and favor its re-election (M). At central level, managers and policy makers trusted the implementing hospital to apply the policy as planned. In this configuration, the implementation resulted in sufficient resources being allocated to the policy at the central level (Outcome).

The policy was introduced in the peripheral implementing hospital at a moment when the hospital managers (Actors) were experiencing a high bottom-up pressure to increase availability and quality of services, and were looking for opportunities to respond to it (Context). They felt the political pressure as a strong constraint; they did not want to be perceived as disobedient civil servants and become socially excluded. The hospital managers perceived the regularity of the reimbursement as a stabilization factor (Mechanism), which reduced their distrust toward the state (Intermediate outcome). They perceived the policy as a double win situation (Mechanism): not only was it an opportunity to comply both with the bottom-up and top-down pressure, but also to improve the financial situation of the hospital and maintain the motivation of their health workers. Managers believed they have enough autonomy to make necessary “positive” adaptations in the policy (Context). As a result, the hospital managers ensured the implementation of the policy (O).

Open critique emerged around 2016, when Ministry of Health staff questioned the fee exemption policy (33) and argued for a national health insurance scheme. The latter received considerable support under the presidency of Patrice Talon from 2016 onwards. His first Minister of Health declared in the media that:

“The free care approach for all is itself a problem. Many Beninese can pay and we offer them free care… The worst point is that, if we continue like this, we will waste so much resources that we will not be able to address and guarantee the fee exemption for those who need it the most.” (Minister of Health of Benin, 2018 in interview with journalists)

Moreover, the staff of the Ministry of Health in charge of resource allocation reported that despite the correct funding of the policy, women were still paying a significant fees and were expressing low satisfaction with the policy. The staff expressed doubts about the efficiency of the policy and they feared corruption:

“Mistrust is the problem! Because we realized that the amounts the providers claimed was higher than the services which were provided. There are women who give birth naturally but who are counted as beneficiaries of the policy.” (Semi-structured interview, Manager at the ministry of health, 2018)

Our analysis found that the delays in reimbursement of the hospital increased. For instance, cesarean sections carried out in August 2016 were reimbursed in May 2018. Up to the end of June 2018, none of the cesarean section performed in 2017 and in 2018 were reimbursed yet.

In 2016, manager M2 replaced M1. During his tenure, the trust index plunged from +2 to −3 (Table 2). According to M2, the arrangement introduced by M1 to attract and maintain specialists created a perverse incentive, generating unnecessary cesarean sections and poorer quality of services:

“Since providers are paid directly on the hospital budget and paid by percentage (receiving a share of the income generated by their services), the more interventions they do, the higher is the payment they receive. So the service provided is no longer objective, the service provision became driven by personal interests… So, there are cases (of caesarean section) we can avoid, but we do them anyway.”(Semi-structured interview, Hospital manager, 2018)

Aiming at both lowering the rate of unnecessary cesarean sections and reducing the loss of revenue due to the reimbursement delays, M2 reduced the number of medical staff under contract. She kept only one trusted gynecologist. The number of cesarean sections performed in the hospital decreased by 24% in 2017, as compared to 2015. M2 linked the payment of the cesarean section bonus to the prior reimbursement by the agency. She reviewed the contents of the cesarean section kit and removed antibiotics, pain relief and antimalarials in 2016. The number of other consumables like needles were halved. As a result, the kit completeness index (double gray line in Figure 3) dropped sharply from 95% in 2015 to 38% in 2016. The managers of the hospital felt they had strong arguments to introduce these reforms, but expressed being constrained in their autonomy:

“If drugs are delivered for free, the pharmacy will need to be closed and patients will have to buy them in private pharmacies or will have to be referred to other hospitals. (But) we do not feel free (…) We are not comfortable at all [to take measures that safeguard financial survival of the facility but that introduce charges to users]. The status of a public hospital limits the autonomy of taking certain decisions.” (Semi-structured interview, Hospital manager, 2018)

Despite being aware of these changes, the implementing agency did not officially notify the hospital nor sanction it. The agency managers reported that since they were failing to deliver on a critical part of the contract (for instance the timely reimbursement), they felt weakened in their capacity to enforce the policy or the contracts. They also felt it was beyond their core duties and means.

The reimbursement became irregular and unpredictable. The Agency still focused on checking the expense claims but did no longer monitor how the hospitals adapted to the financial constraints induced by the reimbursement delays (Intervention). The political support for the policy became very low (Context). The national health insurance policy created competition (Context) and obtained support among both political and technical actors. The outcome was reduced implementation of the policy at the central level (O).

At the hospital, the bottom-up pressure on the hospital managers decreased from 2016 onwards (Context). The reimbursement delays (Intervention) increased the financial burden (Intermediate outcome), which the hospital managers perceived as a threat (Mechanism). Managers perceived enough autonomy (Context) to reduce the benefit package (Intermediate outcome) in order to secure the financial survival of the hospital despite fears of administrative sanctions. The latter did not materialize as neither the Agency nor the Ministry of Health felt entitled to sanction in case a party failed to implement the policy (Context). In term of outcomes, the financing for the policy reduced significantly at central level. At peripheral level, the resources allocated to the policy by hospital managers were equally reduced. Trust among the stakeholders declined.

We present the refined programme theory in a graphical format (Figure 4).

This study followed a policy from its inception in 2009 to 2018. It focused on the relationship between the implementing agency at central level and an implementing hospital at peripheral level. It identified two phases in the policy implementation. In a first period, both the central and peripheral level allocated sufficient resources to correctly implement the policy, while in the second period, the opposite happened.

We found that the key contextual difference was the political support and the perception of the relevance, effectiveness and sustainability of the policy as compared to available policy alternatives. We found thus that the actual implementation of a policy in the form of a programme at the central level depends on how it is perceived and endorsed by political and technical stakeholders, which influences the level of resource allocation within the public resource allocation arena.

Most of the pioneering implementation literature starts from the premise that politics determines policy goals and that implementers translate it into action (11). We found that the implementers and the final beneficiaries determine the policy implementation output as much as the policymakers. Our study shows that the objectives and expectations of policymakers concerning a given policy may change over time, influenced by (in)formal feedback from various communities experiencing the policy; such feedback shapes next phases of the policy implementation through a set of mechanisms like loss of trust, perceived inefficiency, the resurgence of ideological resistance, loss of political support, all resulting in a change of the resources allocated to the policy.

“Insufficient resources” and “opposition within the policy community” are often reported as determinants of policy implementation since the first generation of policy implementation research (12, 43). They are also mentioned in the recent literature on implementation of user fee exemption policy in sub-Saharan Africa (44–46). Funding for the policy is likely to reduce if influential stakeholders no longer support it, either because they perceive it as inefficient or untrustworthy. We found that policy community members interpret political support in terms of expected political rewards (mechanism) that may originate from the implementation of the policy. The political reward is more likely to be low if key stakeholders, including the citizens, are not satisfied (voter dissatisfaction—mechanism). If the policy implementation is hampered for instance because of inadequate central funding, the policy community may start perceiving it as a threat and disengage from it, setting off a negative feedback loop.

At the level of the hospitals, we found the vision of the managers, their perception of the policy and its instruments, the pressure they feel (either administrative and hierarchical or political in nature), the room of maneuver they perceive, and the level of trust to be determinants of policy implementation, in line with (47). We found, for instance, that one manager developed a response centered on community expectations and health workers' motivation, while the other focused on containing unnecessary cesarean sections and reducing the loss of revenue. In both cases, the manager perceived sufficient managerial autonomy to make adaptations. The timely availability of resources at the peripheral level is an intermediate outcome and a logical determinant of successful policy implementation. The timely provision of resources to the hospital improves the central level's legitimacy, contributes to higher levels of trust between local managers and their staff and lowers the stress levels of local managers as it improves their self-efficacy and allows them to plan and develop strategies. The contract introduced in 2013 did little to improve the implementation because the implementing agency failed to deliver on its own commitments, and by doing so lost the political legitimacy to enforce it. This resulted in a laissez-faire response from the central level to the adaptations introduced in policy implementation by local managers, even if they prevent the policy to achieve its goals.

We can also draw some methodological lessons, which we summarized in Box 1. In our study, we analyzed the behavior of the implementing agency and a hospital implementing the policy over a period of 10 years. This long period allowed for a configurational comparative analysis over time. In applying the realist evaluation approach to the study of the implementation of a policy over a long period of time, we encountered the well-known challenge of exploring policy processes that not only occurred a long time ago, but which were also not well-documented. This made developing thick descriptions (48) of the context, the policy, the process, and the actors not an easy task. Since realists seek to explore the causal pathways underlying change and thus must look for mechanisms, the task of retrospective policy analysis was even more difficult. In response, we collected data from a multitude of sources and analyzed these using different strategies. After lengthy discussions amongst the authors, we presented our preliminary analysis to key respondents, using the realist interview technique to seek respondent validation (49, 50).

Box 1. Summary of key methodological lessons for using realist methodologies in policy implementation research.

What do you need? Strong policy process documentation is necessary

Applying realist methodologies to policies may require documenting in detail key features of the policy over a long period of time. Policy process documentation is thus paramount. It has to focus on key components like policy content, policy context, policy process and policy actors.

Where to start? Anchor the data collection process on the outcome

Anchoring the data collection process on the outcome, meaning that we assessed the outcomes first and organized the rest of the study to explain this outcome, facilitated the study of a fluid policy process that plays out in an open system. As the potential outcome scenarios are limited, starting from there facilitates the identification of the ICAMO configurations.

How to deal with the unexpected outcomes and conditions inherent to health policies and health systems? Engage the stakeholders, use multiple tools, technics and sources, and adopt a long-term approach

In applying realist methodologies to policies studies, it may be challenging to define the outcome, since the policy process may have multiple (un)intended or (un)expected outputs. Another challenge is to identify unexpected context conditions that may influence the intervention, or its outputs and outcomes. Clarifying the research question or ensure a proper engagement of various stakeholders who will use the result of the research help to address those challenges. Moreover, using multiple tools, technics and sources, and adopt a long-term follow-up approach enhance the researcher to remain open and to capture unexpected relevant factors and unexpected outcomes.

What key added values of realist methodologies in HPSR from this study? Facilitate the development of prospective policy analysis and systemic learning

Realist evaluation can strengthen prospective policy analysis. With a configurational analytical approach centered on actors in contexts, generative causation and a focus on theory, realist evaluation can enhance the methodological ground, the feasibility and the relevance of the prospective policy analysis. It can facilitate the systematic learning by aligning realist cycles with learning cycles within the policy process.

Where are more methodological research and guidance needed? Scientific abstraction and scientific concretisation

Applying realist methodologies to policy studies requires a process of navigating between “scientific abstraction and scientific concretisation.” There is still little methodological guidance in the literature on how to do this. We call for more attention and guidance on this methodological process in the current debate on realist research.

“Anchoring” the data collection process on the outcome, meaning that we assessed the outcomes first and organized the rest of the study to explain this outcome, facilitated the study of a fluid policy process that plays out in an open system. As the potential outcome scenarios are limited, starting from there facilitates the identification of the ICAMO configurations.

Another methodological lesson relates to the “abstraction process” inherent to the application of the realist methodology to policy processes. There is in the current literature little guidance on this process of navigating between “scientific abstraction and scientific concretisation” (51, 52), while it is key in the methodological process. “Effective programme, for instance, is an abstract concept that requires concrete criteria of assessment. The criteria may vary in function of the policy under investigation. In our study, we used the ratio “financial resources allocated in the budget of the Ministry of Health over the number of the cesarean section performed in the accredited facilities” to make concrete the abstract concept of “effective programme.” During such analysis, the researcher shifts from the collected data to a more abstract level to refine the programme theory. We call for more attention and guidance on this methodological process in the current debate on realist research.

We also found that realist evaluation can strengthen prospective policy analysis, which is a “real-time documentation and analysis of political economy factors and feedback to engender reform” (53). With a configurational analytical approach centered on actors in contexts, generative causation and a focus on theory, realist evaluation can enhance the methodological ground, the feasibility and the relevance of the prospective policy analysis. It can facilitate the systematic learning by aligning realist cycles with learning cycles within the policy process. This can happen by making explicit the assumptions of policy makers and implementers and testing them prospectively (54). The refined theories which result from such studies can inform the subsequent stages of the policy process and strengthen the learning system necessary for stronger and more resilient health systems (55).

Finally, “outcome” in realist evaluation is a construct that reflects “the practical effects produced by causal mechanisms being triggered in a given context.” (56), which can be assessed in terms of intensity and sub-groups (57). In our study, a particular challenge was the definition of the outcome, since the policy process may have multiple (un)intended or (un)expected outputs. Another challenge is to identify unexpected context conditions that may influence the intervention, or its outputs and outcomes. Thanks to the diversity of the tools, the variety of technics and of the sources, and the long-term follow-up we felt better equipped to remain open and to capture unexpected factors and unexpected outcomes.

With our study, we set out to test whether realist methodologies can be applied to policy research. In the example presented in this paper, realist evaluation made it possible to formulate plausible explanatory theories on what drives change in policy implementation outputs over time in a low-income country. At central level, the availability of resources for a given policy is constantly challenged in a competitive resource allocation arena where the political power and legitimacy of the group supporting a policy are key. Political power and legitimacy are influenced by the trustworthiness of the policy, its implementation structure and how its outputs are perceived by the community. The role of the health facilities at the meso-level, where the services are delivered, is key in this regard and depends on the trustworthiness of the resources received from the central level, the organizational autonomy, the personal attributes of the managers, and the accountability arrangements that surround the operational management of the policy.

Realist methodologies have strong potential for health policy research and especially in prospective policy analysis. This is maybe one of the way policy research can have a transformative impact necessary to foster the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals in LMICs.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Comité Local d'Éthique pour la Recherche Biomédicale, Université de Parakou (CLERB-UP), Bénin. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

J-PD, BM, and SV wrote the protocol of the study. J-PD collected the data, performed the primary analysis, drafted the first version of the manuscript, and integrated and inputs of all authors. SV and BM reviewed it extensively for inputs. All authors approved the last version.

J-PD received a doctoral scholarship from the Directorate-General Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid of Belgium. The authors received funding from the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Union to conduct the research that led to the development of this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. World Health Organization. WHO|What is Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR)? Geneva: World Health Organization (2017). Available online at: https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/about/hpsr/en/ (accessed May 8, 2019).

2. Parkhurst JO. Evidence-based policymaking: an important first step and the need to take the next. In: Parkhurst J, editor. The Politics of Evidence (Open Access) From Evidence-Based Policy to the Good Governance of Evidence. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group (2016). p. 14–37. doi: 10.4324/9781315675008

5. Marchal B. Why do some hospitals perform better than others? a realist evaluation of the role of health workforce management in well-performing health care organisations. A study of 4 hospitals in Ghana (Dissertation), Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium (2011).

6. Gilson L. Health Policy and System Research: A Methodology Reader. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and System Research, World Health Organization (2012).

7. Marchal B, van Belle S, van Olmen J, Hoerée T, Kegels G. Is realist evaluation keeping its promise? A review of published empirical studies in the field of health systems research. Evaluation. (2012) 18:192–212. doi: 10.1177/1356389012442444

8. Usher AM, McShane KE, Dwyer C. A realist review of family-based interventions for children of substance abusing parents. Syst Rev. (2015) 4:177. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0158-4

9. Bamberger M, Vaessen J, Raimondo E. Dealing With Complexity in Development Evaluation: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. (2016).

10. Robert E, Samb OM, Marchal B, Ridde V. Building a middle-range theory of free public healthcare seeking in sub-Saharan Africa: a realist review. Health Policy Plan. (2017) 32:1002–14. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx035

11. Hill M, Hupe P. Implementing Public Policy: An Introduction to the Study of Operational Governance. London: Sage (2009).

12. Nilsen P, Ståhl C, Roback K, Cairney P. Never the twain shall meet?–A comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implement Sci. (2013) 8:63. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-63

13. Fischer F, Miller GJ, Sidney MS. Handbook of Public Policy Analysis: Theory, Politics, and Methods. London: CRC Press (2007). doi: 10.4135/9781848608054

14. Wildavsky AB, Pressman J. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland, The Oakland Project Series. Berkley, CA: University of California Press (1973). doi: 10.1016/S0012-8252(01)00080-0

15. Derthick M. New Towns In-Town; Why a Federal Program Failed. Washington, DC: Urban Institute (1972).

16. Bardach E. The Implementation Game: What Happens After a Bill Becomes a Law. Cambridge: MIT Press (1977).

17. Lipsky M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation (1980).

18. Elmore RF. Backward mapping: implementation research and policy decisions. Polit Sci Q. (1979) 94:601–16.

19. Ingram H. Policy implementation through bargaining: the case of federal grants-in-aid. Public Policy. (1977) 25:499–526.

20. Hjern B, Hull C. Implementation research as empirical constitutionalism. Eur J Polit Res. (1982) 10, 105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1982.tb00011.x

21. Hjern B, Porter DO. Implementation structures: a new unit of administrative analysis. Organ Stud. (1981) 2:211–27. doi: 10.1177/017084068100200301

22. Sabatier PA. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: a critical analysis and suggested synthesis. J Public Policy. (1986) 6:21–48. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00003846

23. Goggin ML. Implementation theory and practice–toward a 3rd generation. Am Polit Sci Rev. (1991) 85:267–268. doi: 10.2307/1962902

24. Elmore RF. Forward and Backward Mapping: Reversible Logic in the Analysis of Public Policy. Washington, DC: Washington University (1983).

26. Honig MI. Complexity and policy implementation: challenges and opportunities for the field. In: Honig M, editor. New Directions in Education Policy Implementation: Confronting Complexity. Albany, NY: The State University of New York (2006). p. 1–22.

27. Ostrom E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015).

28. van Hulst M, Yanow D. From policy “frames” to “framing”: theorizing a more dynamic, political approach. Am Rev Public Admin. (2016) 46:92–112. doi: 10.1177/0275074014533142

29. Pfadenhauer LM, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Lysdahl KB, Booth A, Hofmann B, et al. Making sense of complexity in context and implementation: The context and implementation of complex interventions (CICI) framework. Implement Sci. (2017) 12:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0552-5

30. Peters DH, Tran TN, Adam T. Implementation Research in Health: A Practical Guide. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization (2013).

31. Grindle MS, Thomas JW. (1991) Public choices and policy change : the political economy of reform in developing countries. Johns Hopkins University Press.

32. Van Belle S, van de Pas R, Marchal B. Towards an agenda for implementation science in global health: there is nothing more practical than good (social science) theories. BMJ Glob Health. (2017) 2:e000181. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000181

33. Dossou JP, Cresswell JA, Makoutodé P, De Brouwere V, Witter S, Filippi V, et al. “Rowing against the current”: the policy process and effects of removing user fees for caesarean sections in Benin. BMJ Glob Health. (2018) 3:e000537. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000537

34. Booth A. Unpacking your literature search toolbox: on search styles and tactics. Health Inform Libr J. (2008) 25:313–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2008.00825.x

35. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. New York, NY: Springer Pub. Co. (2007).

36. Dossou JP, De Brouwere V, Van Belle S, Marchal B. Opening the “implementation black-box” of the user fee exemption policy for caesarean section in Benin: a realist evaluation. Health Policy Plan. (2020) 35:153–66. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz146

37. Yin RK. Case Study Research Design and Methods. Applied Social Research Methods Series Volume 5, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. (2009).

38. Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. (1994) 9:353–70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.4.353

39. Verhoest K, Peters BG, Bouckaert G, Verschuere B. The study of organisational autonomy: a conceptual review. Public Admin Dev. (2004) 24:101–18. doi: 10.1002/pad.316

40. Marchal B, Kegels G, Van Belle S. Theory and realist methods. In: Emmel N, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, Monaghan M, Dalkin S, editors. Doing Realist Research. London: Sage Publications Ltd. (2018). p. 79–90. doi: 10.4135/9781526451729.n6

41. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. (1984). p. 1–263.

42. Meyer SB, Lunnay B. The application of abductive and retroductive inference for the design and analysis of theory-driven sociological research. Sociol Res Online. (2013) 18:1–11. doi: 10.5153/sro.2819

43. Schofield J. Time for a revival? Public policy implementation: a review of the literature and an agenda for future research. Int J Manage Rev. (2001) 3:245–63. doi: 10.1111/1468-2370.00066

44. Gilson L, McIntyre D. Removing user fees for primary care in Africa: the need for careful action. BMJ. (2005) 331:762–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.762

45. Witter S, Adjei S. Start-stop funding, its causes and consequences : a case study of the delivery exemptions policy in Ghana. Int J Health Plan Manage. (2007) 22:133–43. doi: 10.1002/hpm

46. Olivier de Sardan JP, Ridde V. L'exemption de paiement des soins au Burkina Faso, Mali et Niger. Afr Contemp. (2012) 243:11. doi: 10.3917/afco.243.0011

47. Berman P. The Study of Macro and Micro Implementation of Social Policy. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation (1978).

48. Geertz C. Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture. In: Geertz C, editor. Interpretation of Cultures. New York, NY: Basic Books (1973). p. 3–32.

49. Manzano A. The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation. (2016) 22:342–60. doi: 10.1177/1356389016638615

50. Mukumbang FC, Marchal B, Van Belle S, van Wyk B. Using the realist interview approach to maintain theoretical awareness in realist studies. Qual Res. (2019) 20:146879411988198. doi: 10.1177/1468794119881985

51. Portides DP. A theory of scientific model construction: the conceptual process of abstraction and concretisation. Foundat Sci. (2005) 10:67–88. doi: 10.1007/s10699-005-3006-5

52. Nielsen N. Scientific Knowledge and Scientific Abstraction, Medium. (2018). Available online at: https://medium.com/@jnnielsen/scientific-knowledge-and-scientific-abstraction-4adeb6589706 (accessed May 26, 2019).

53. Buse K. Addressing the theoretical, practical and ethical challenges inherent in prospective health policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. (2008) 23:351–60. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn026

54. Marchal B, Giralt AN, Sulaberidze L, Chikovani I, Abejirinde IO. Designing and evaluating provider results-based financing for tuberculosis care in Georgia: a realist evaluation protocol. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e030257. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030257

55. Meessen B, Akhnif ELH, Kiendrébéogo JA, Alaoui AB, Bello K, Bhattacharyya S, et al. Learning for universal health coverage. BMJ Glob Health. (2019) 4:e002059. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002059

56. Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation: An Overview. Nottingham: Founding Conference of the Danish Evaluation Society (2000).

Keywords: realist methodologies, policy process, implementation, complexity, sub-Saharan Africa, user fees, exemption mechanisms, theory

Citation: Dossou J-P, Van Belle S and Marchal B (2021) Applying the Realist Evaluation Approach to the Complex Process of Policy Implementation—The Case of the User Fee Exemption Policy for Cesarean Section in Benin. Front. Public Health 9:553980. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.553980

Received: 20 April 2020; Accepted: 07 May 2021;

Published: 08 June 2021.

Edited by:

Raphael Lencucha, McGill University, CanadaReviewed by:

Matthew Hunt, McGill University, CanadaCopyright © 2021 Dossou, Van Belle and Marchal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jean-Paul Dossou, amRvc3NvdTgwQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.