- 1Pandemic Health System REsilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) Global, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 2Neurovascular Imaging Laboratory, Clinical Sciences Stream, Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 3South Western Sydney Clinical School, University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Department of Neurology and Neurophysiology, Liverpool Hospital and South West Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD), Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 5NSW Brain Clot Bank, NSW Health Statewide Biobank and NSW Health Pathology, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Medical students are the future of sustainable health systems that are severely under pressure during COVID-19. The disruption in medical education and training has adversely impacted traditional medical education and medical students and is likely to have long-term implications beyond COVID-19. In this article, we present a comprehensive analysis of the existing structural and systemic challenges applicable to medical students and teaching/training programs and the impact of COVID-19 on medical students and education. Use of technologies such as telemedicine or remote education platforms can minimize increased mental health risks to this population. An overview of challenges during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic are also discussed, and targeted recommendations to address acute and systemic issues in medical education and training are presented. During the transition from conventional in-person or classroom teaching to tele-delivery of educational programs, medical students have to navigate various social, economic and cultural factors which interfere with their personal and academic lives. This is especially relevant for those from vulnerable, underprivileged or minority backgrounds. Students from vulnerable backgrounds are influenced by environmental factors such as unemployment of themselves and family members, lack of or inequity in provision and access to educational technologies and remote delivery-platforms, and increased levels of mental health stressors due to prolonged isolation and self-quarantine measures. Technologies for remote education and training delivery as well as sustenance and increased delivery of general well-being and mental health services to medical students, especially to those at high-risk, are pivotal to our response to COVID-19 and beyond.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a public health crisis with enormous and diverse social, economic and health consequences (1). Vulnerable and minority groups are being disproportionately impacted, often due to underlying social inequities, health disparities, and comorbidities (2, 3). Medical students are also vulnerable, particularly those from underprivileged or minority backgrounds. However, the plights of medical students in COVID-19 has drawn limited attention. Our previous reports highlighted that frontline medical professionals are vulnerable to mental illness or psychological distress (2, 4, 5). However, medical students are not considered part of the healthcare workforce, lacking access to COVID-19 mental health support available to healthcare workers. We postulate that medical students are especially vulnerable during the pandemic and hence require additional and tailored support, distinct from the general population or medical professionals. Whilst in specific instances or institutions, final year medical students' induction to the healthcare workforce has been expedited to meet increased demands during COVID-19, it's poignant that those in formative years of their education and clinical training have also been removed from structured in-person clinical environments (6, 7). The aim of this article is to critically evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on medical education, training and medical students; and to make targeted recommendations to maintain continuity and support mental health, well-being and education needs of affected students.

Methods

Relevant literature was identified via PubMed and Medline review, including original, opinion and perspective articles, topic reviews, official national medical associations/bodies and societal guidelines and media sources. The PubMed/Medline search was performed using the keywords “Medical Students,” “COVID-19” and “Medical Education” until July 31, 2020. The PICO template, with the population (medical students), intervention (COVID-19), comparator (standard medical education pre-COVID-19) and outcome (impact on medical students/education and changes adopted due to COVID-19), was used. The literature was examined to critically analyse existing structural and systemic challenges of medical education, with an emphasis on the use of technologies such as telemedicine or remote education, and formulate a synthesis on the impact of COVID-19 on medical education, students and training. Appropriate articles relevant to COVID-19 were included in this synthesis. Medical students who are especially vulnerable, such as those with pre-existing mental illness, disadvantaged backgrounds, overseas medical students and those in under-resourced settings are considered and impact of COVID-19 on these subgroups are presented. We also provide targeted recommendations to address acute and systemic challenges during and beyond COVID-19.

Results

Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Students

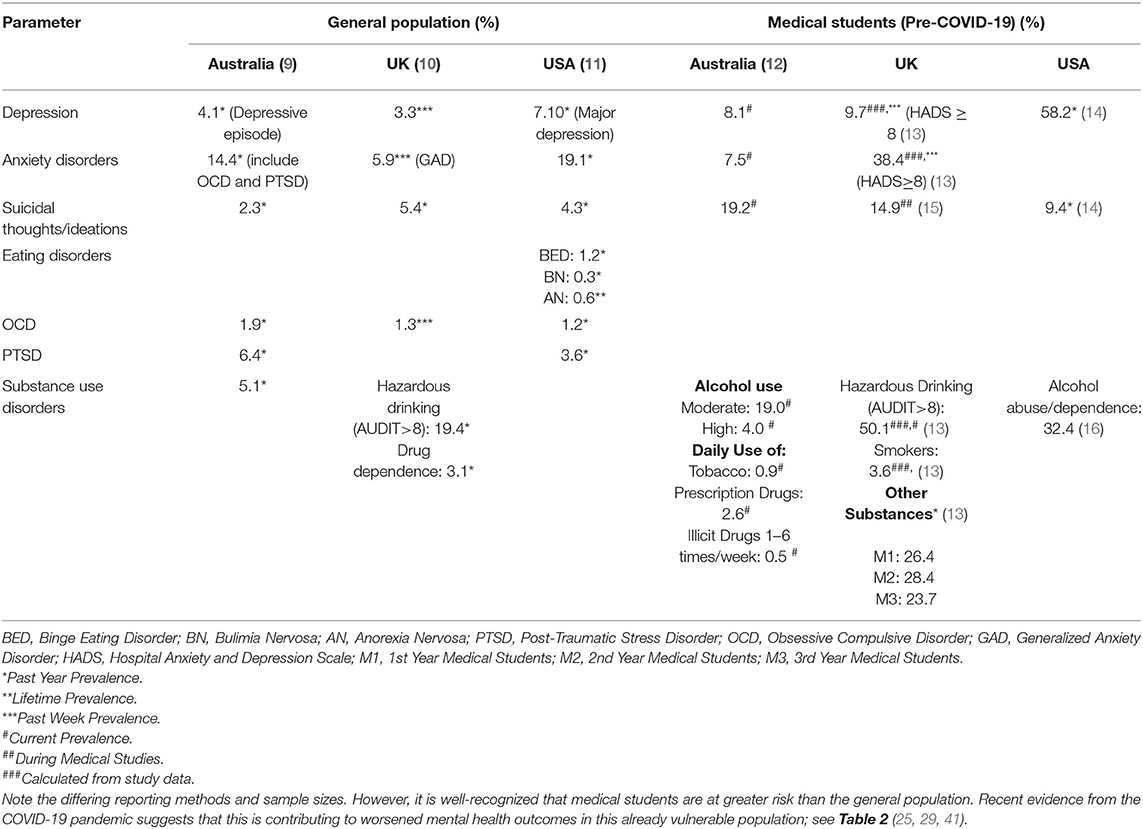

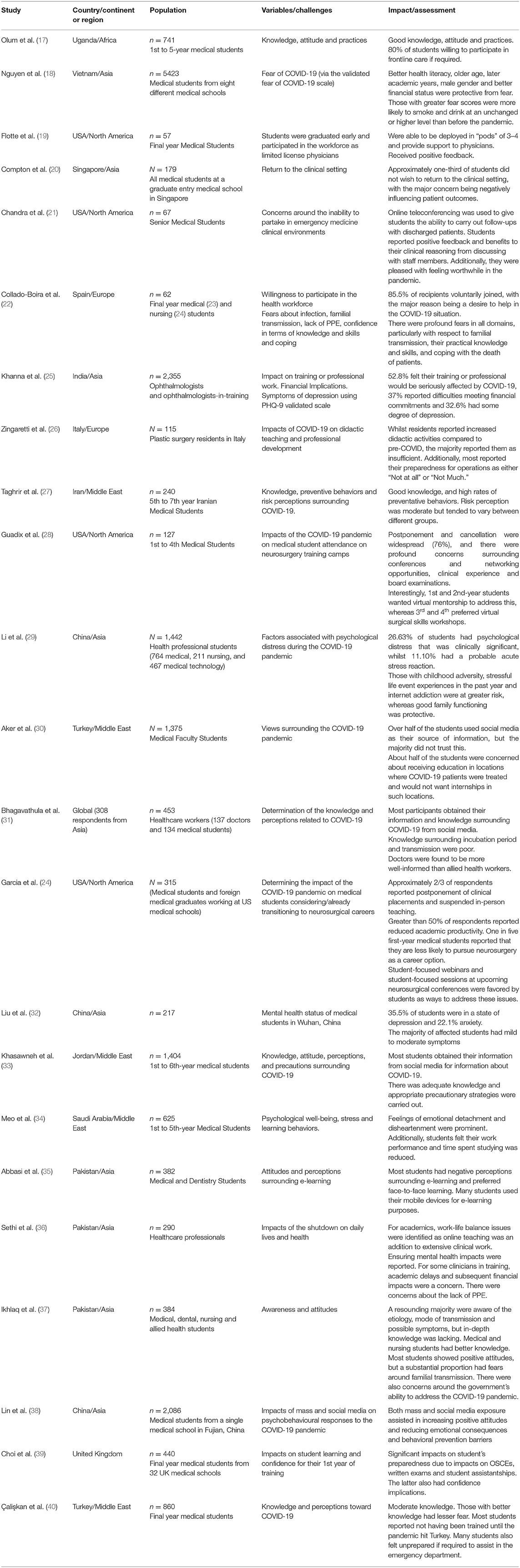

Medical students are at increased risk of mental or psychological disorders, with a significantly higher prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms and suicidal ideations relative to the general population (8) (Table 1). Disruptions in traditional medical education and training due to COVID-19 have increased risk of poor mental health among medical students worldwide (Table 2) (8–16). The mental health burden could be exacerbated in those with pre-existing mental illness (4, 42). Concerns around inadequate skill development due to suspension of hospital placements, ambiguity around future prospects and subsequent financial implications have been reported. Poor health behaviors, sleep deprivation during COVID-19 and pre-existing chronic diseases among medical students could adversely affect physical and mental health (29), with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity and chronic neurological comorbidities associated with increased risk of hospitalization and severe illness due to COVID-19. Targeted support and specific recommendations for these subgroups have been made elsewhere (2, 5).

Table 2. Impact of COVID-19 on medical education, training and mental health of medical students and trainees.

Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education

Clinical clerkship is fundamental to medical students learning from more experienced practitioners, and becoming more independent and confident clinically (43). The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) released guidelines recommending withdrawal of medical students from clinical environments after the COVID-19 outbreak (44). This was followed by suspension of clinical placements by several Australian medical schools to reduce risks associated with more personnel in clinical environments (45). This trend is true worldwide and has caused widespread concerns from medical students about their learning (46). Lost in-hospital clinical clerkships have caused fears surrounding deficiency in practical skills, training and “imposter syndrome” (17, 20, 46, 47). This extends beyond medical students, with surgical trainees reporting fears around preparedness for surgeries due to the suspension of elective surgeries and face-to-face training (26, 48).

Owing to the climate of uncertainty and limited clinical exposure, concerns surrounding progression through the medical course, training pathways and job prospects have been reported (45, 47, 49), including exploration of alternative career paths (24, 28). This also applies to those at advanced stages in their training, such as trainees and specialists-in-training (26, 28).

Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Students From Vulnerable Groups

Impact on various segments of vulnerable populations within the broad medical students' community is presented below.

Students With Pre-existing Mental Health Issues

The pandemic has caused increased stressors, with social isolation measures particularly associated with, and resulting in, increased depression, anxiety and suicidal ideations, as well as poor health behaviors among medical students during COVID-19 (32, 34), and also medical specialists and trainees (23, 50). This issue is exacerbated by lower uptake of mental health services due to stigma surrounding mental health issues, confidentiality concerns, and the belief that medical students should be self-sufficient in addressing and coping with their mental health issues (51). Social isolation is known to be linked to psychological disorders and/or mental health issues in otherwise healthy individuals, and those with existing mental illness are especially vulnerable, with an increased likelihood of concomitant social factors that can worsen their vulnerabilities (52). These may include conversion disorders, acute stress disorders, mood disorders and frustration (25). Such issues can persist beyond periods of social isolation and are associated with longer-term disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and exacerbation of obsessive-compulsive disorder like symptoms (4), as reported after the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak (52). Additionally, medical students currently on psychotherapy or psychiatric interventions may face difficulty in the prescription refill and attending regular therapy sessions (52).

Recent studies show that whilst poor eating behaviors are being seen in the general population, this is more pronounced in those with pre-existing eating disorders (41, 53). Medical students may also be at increased risk of developing eating disorders due to academic and emotional stressors (54). Those with existing eating disorders may be vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and resultant anxiety concerning their health (55). Fears about inability to obtain foods consistent with individual meal plans presumably increases anxiety, and fears of relapse (41, 53). Increased social isolation, gym closures and social media use may also precipitate relapse, and body image concerns, causing withdrawal from engaging with others through video calls, leading to heightened isolation (55). Whilst video-based cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) has shown efficacy, the success of this in pandemic situations is largely unknown (56), with patients in the early transition feeling their quality of care was reduced. Individuals with childhood traumas are also more vulnerable to mental health impacts and warrant special consideration (29).

Students From Financially Disadvantaged Backgrounds

Telecommunications technology has provided an effective way to address gaps in learning caused by the pandemic. However, for those engaging in online learning, there may be inequities, and subsequent frustration and stress, as even in developed countries, not all students have access to the digital devices or infrastructure required to effectively partake in online learning (57). Moreover, those in remote and rural areas often have poor internet connections (58). Prolongation of the course length can have significant financial consequences and hence impact academic progression (18).

The widespread redundancies, job losses and closure of non-essential services due to COVID-19 have forced several students to resume work to support their families (57). This can negatively affect their ability to engage in online learning activities due to concurrent work responsibilities (18). Medical students from disadvantaged backgrounds reliant on public transport to commute also face greater infection risks.

Students in Developing Countries

Students in developing countries face unique challenges such as limited availability of online teaching resources for medical education (59). The frontline healthcare workers handling COVID-19 associated hospitalizations are limited in their ability to develop teaching resources (36). Given that online teaching modalities have been largely unexplored in many of these countries, these issues have been exacerbated (60). Poor internet access and stability are also reported, causing an unwillingness on students' part to transition to online teaching modalities, and negative perceptions surrounding use of telecommunications technology for learning (35). Perceived poor responses by governments and public leadership have also inflicted psychological stress among students (37).

Students From Minority Groups

Medical students belonging to racial, ethnic and linguistic minority groups face unique challenges due to systemic barriers (61, 62). A 2019 American study showed that white students were more likely to have grading disparities favoring them than minority groups (62). Implicit bias, along with factors such as inappropriate learning environments for minority groups, were reported to drive these disparities. Incorporation of concrete rubrics and marking criteria to limit subjectivity and implicit bias training programs to educate examiners may reduce these (62).

A 2020 study similarly found that underrepresented minorities, Asian and multiracial students, were more likely to be deprived of opportunities based on race than white students (7.3, 4.4, 3.6 vs. 1.5%, respectively) and be subjected to racially offensive comments (18.9, 12.9, 9.6 vs. 2.5%, respectively). Additionally, female students were more likely to be discriminated than males (28.2 vs. 9.4%) (63), and lesbian, gay and bisexual students were more likely to be mistreated than heterosexual students (43.5 vs. 23.6%) (63).

There are concerns that people from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, already reported to have higher rates of infection and racial discrimination during the pandemic, will present later and at more advanced stages of disease due to fears of structural racism, thereby increasing clustering and community transmission risk (64–66). Systemic issues around underreporting of racial harassment also exist, contributing to increased mental health risks among minority groups, with beliefs existing that complaints pertaining to discrimination will not be taken seriously and/or addressed appropriately (67). To our knowledge, there is limited research into impacts of COVID-19 on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI+) community. However, systemic inequalities and inequities are known to cause long-term stress, increasing vulnerability to negative mental health implications. Of particular concern is isolation and separation from trusted family and friends due to quarantine measures (68). Medical students are particularly reluctant to discuss sexual orientation, thereby raising concerns over their ability to seek help (61). Confidential telehealth services have sprung up worldwide and may assist students from minority groups.

International Medical Students

International medical students are particularly impacted, with several institutions shifting to online delivery methods soon after the start/resumption of the academic year (58). Resultantly, there is an increased risk of isolation and subsequent mental health issues, with an Australian study showing that international students have higher baseline depression risk than local students considering loneliness, anxiety and stress scores (69). Additionally, loss of employment, financial insecurity and lack of family support are significant, especially for international students not returning to their home countries (52), as social and family support may be protective against mental health sequelae (29). With university campuses closing down, accommodation may become an issue, exacerbated by job losses from closure of non-essential services (70).

For students having returned to their home countries, concerns surrounding academic progression are likely stressors, amidst new immigration measures including indefinite sealing of borders to non-citizens, temporary-residents or immediate family thereof by several countries (71). Variation in time zones during online learning for overseas courses or seminars may impact sleep cycles, with insufficient sleep associated with various mental disorders including depression (72). Once border restrictions are eased, and foreign students return to their host countries, it may not be feasible for them to return home to loved ones (73, 74). Travel restrictions could prolong course length and incur subsequent financial burden (70).

The inability to access clinical environments is particularly relevant, as engaging with patients and peers of their host country is pivotal to developing cultural competence and understanding socio-cultural norms, expectations and communication methods, along with language skills. Lack of this can be a stressor and contribute to imposter syndromes (75). Telecommunications technology may revive some degree of communication. However, non-verbal body language, pivotal in communication, cannot be adequately simulated (76).

Medical Student Parents

Medical students who are parents may have hindered engagement in interactive learning via telecommunications due to a need to take care of children, which other students might not appreciate, causing feelings of isolation and exclusion, and frustration (77, 78). Additionally, individuals may feel caught between notions of service and personal responsibility to their family, which can have personal mental health implications pertaining to guilt (79).

Discussion and Recommendations

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only presented acute challenges to medical education and students but also exposed systemic issues that merit consideration. Given the COVID-19 pandemic has had an exacerbated impact on vulnerable populations, including but not limited to students from vulnerable backgrounds; evidently, these students would need targeted interventions, while recognizing the unique challenges in the COVID-19 era and accounting for socioeconomic aspects. Technologies such as telemedicine and tele-education are emerging as important platforms in mitigating the devastating impact of COVID-19 (80–82). Given the acute impact vis-a-vis rising mortality globally (5, 83), and long-term effects of this outbreak that may last beyond the pandemic (2), strategies toward capacity building are necessary.

We provide recommendations to address the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student mental health and well-being and to build sustainable healthcare and education systems beyond the pandemic.

Technology in Remote Delivery of Medical Education and Training

Restructuring Teaching and Examination Processes

During COVID-19

COVID-19 has led to rapid uptake and development of online teaching to minimize disruption to student learning. Telecommunication technologies are an important component in this, with several institutions having implemented online teaching webinars, simulations and educational clinical skill videos (21, 46). Multimodal teaching approaches catering to various aspects of learning have been implemented (84), along with flipped learning methodologies, which involve students engaging with content prior to class and using later face-to-face time to clarify concepts. This is useful for teaching anatomy using online 3D modeling applications considering suspension of traditional cadaver-based anatomy demonstration at several institutions (85). Online teaching can be made more engaging and effective for students through interactive tools such as voting polls, chat functions and videos (86). Additionally, intensive anatomy and clinical skills workshops, building on online learning resources, can be run when students return to in-person teaching to address deskilling and imposter syndrome concerns (58). Virtual tools such as virtual reality simulations, homemade simulations and smartphone modalities could benefit surgical trainees (46, 87).

These approaches, reliant on effective use of telecommunications technology facilitate enhanced student pedagogy, and thus address the stressors of deskilling, progression and hindered knowledge. Involvement of students in telehealth to provide clinical exposure and help triage patients during the pandemic has been well-received and facilitates controlled patient exposure with feedback (21). Tele-health-based services to partially replace overseas elective placements, although not equivalent, may allow students to gain an enhanced understanding of another healthcare system (88).

Accelerated progression may help ease burdens on the healthcare system. However, immediate transition into clinical practice could instigate higher rates of work-related stress, and this needs to be monitored (89). Concerns around litigation also exist (90), and mandating indemnity guarantees before students are offered jobs could be a solution. Additionally, students can be recruited into hospitals they are familiar with, to facilitate easier and less stressful transitions (91). Increased repurposing of specialists into different roles to assist with the response to the pandemic, and the increasing reliance on telemedicine, sustained supervision and detailed training are necessary to facilitate a seamless transition (4).

Considering higher levels of baseline stress, anxiety, and mental health implications during the pandemic, and the recency of the changes to learning modalities having been implemented, variations in exam structure could be considered. Open book examinations provide an alternative that could reduce students' stress and anxiety, with some institutions also considering pass/fail grading (92, 93). Additionally, students need education about evidence-based medicine, research methodologies and reliable sources, as several students rely on social media for their information on the pandemic (30, 31, 33). Consequently, medical students can be involved in curating evidence-based recommendations and research, to deepen understanding of bias and confounding, and assist in fighting misinformation in the community (94, 95).

Finally, for those entering clinical environments, targeted training in addressing the unique needs of the COVID-19 pandemic would be necessary, with a recent systematic review suggesting a multimodal training approach, which improves student skills, knowledge and attitudes (96). This would also entail teaching around effective communication using telemedicine, including professionalism and catering for patients with different technological capabilities (97).

Beyond COVID-19

Flipped learning could be of great utility toward encouraging independent learning, an integral part of ongoing medical professional development. Due to limited access to cadavers for medical education, such learning methods may be necessary beyond the pandemic (98) and may provide students greater flexibility. Training or volunteering opportunities to work in infectious disease outbreak settings, particularly via teaching around effective telemedicine consultations, could be embedded into medical school curricula to develop student confidence and resilience should an epidemic occur in future (96, 97).

Considering minority groups, training examiners on the role of implicit biases may facilitate longer-term benefits in education and assessment of medical students, and in establishing equitable and fair training, which will indelibly influence students' mental health positively (62). Finally, the misinformation propagated through social media with regards to this pandemic illustrates the role for doctors to act as educators, which could be a key part of medical school curricula going forward (99). Medical students should also be encouraged to be proactive to gain knowledge about COVID-19, to increase awareness on and contest misinformation (100).

Skill Building

During COVID-19

Incorporating inclusive language in everyday practice is pivotal in preventing marginalization of patients from the LGBTQI+ community, who already experience increased levels of stress and fear (68). Mental health first-aid training can help medical students develop strategies to cope with stressors, and help reduce stigmatizing attitudes toward mental health in the broader community (101, 102), with the Australian Government announcing funding to this end (103).

Webinars by experts from various medical disciplines have set a benchmark toward upskilling students and trainees and maintaining their interest and motivation. Using staggered timings to overcome issues related to time zones has been highly effective and can contribute to a global sense of community (46, 104). One such initiative is a collaborative series of recorded seminars and accompanying associated modules by the American College of Surgeons Division of Education and Association for Surgical Education (105), which specifically assist medical students with core surgical knowledge (105). Numerous institutions have also successfully implemented volunteering initiatives including research, assisting hospital triage, contact tracing, and support hotlines to support medical services during the pandemic but also boost student morale as they develop skills and feel “useful” (21, 106, 107). Telehealth service forms the backbone of such initiatives, allowing students to develop skills safely (108, 109).

Beyond COVID-19

Evaluation of skills development programs and their effectiveness is critical. Should they prove beneficial, their incorporation into regular teaching through telecommunications technology could potentially positively influence medical student and trainee mental health in an accessible and convenient manner. Additionally, considering the unpredictability surrounding further spread of the virus, and future outbreaks, such programs may inform future methods of addressing pandemics (108).

Telemedicine for Care of General Well-Being and Mental Health of Medical Students

Creation of Mental Health Support Networks

Supporting medical students and trainees should not be limited to times of crisis such as this pandemic, but this pandemic has brought this important issue to the forefront. We discuss various strategies that can foster mental health support networks for students harnessing technology as an enabler (95).

Mentoring groups

During COVID-19. The creation of mentoring groups for students can facilitate sharing of ideas, advice and combating feelings of isolation. This can be particularly beneficial for international students who have not returned home and may feel isolated, as well as minority groups (69). Such groups can be stratified, with senior students providing advice and guidance to junior students, which may help address stressors related to progression and encourage participation in other areas such as research and peer teaching (110). Discussions with other students can provide a sense of unity and reassure students that they are not alone in feeling “imposter syndrome,” with sharing of online resources such as 3D anatomical models also being beneficial (111). Students from various backgrounds, including international, minority and medical student parents can be placed together in groups to facilitate increased understanding of the various challenges others from different backgrounds face, which may assist with developing empathetic competence (111). Such mentoring doesn't need to be faculty-driven but can be led by medical students themselves, who can use existing social media networks and telecommunications to overcome barriers imposed by social distancing policies (104, 111–113).

Beyond COVID-19. Mentoring groups or networks developed during COVID-19 should be continued beyond this pandemic. This would provide students an opportunity to interact with others, and obtain advice and guidance about study, research, and future training prospects (24, 110). Also, the social media-enabled hashtag support networks should be encouraged and propagated, with the “pay it forward” attitude (104, 112).

Tele-Psychiatry and Support Services

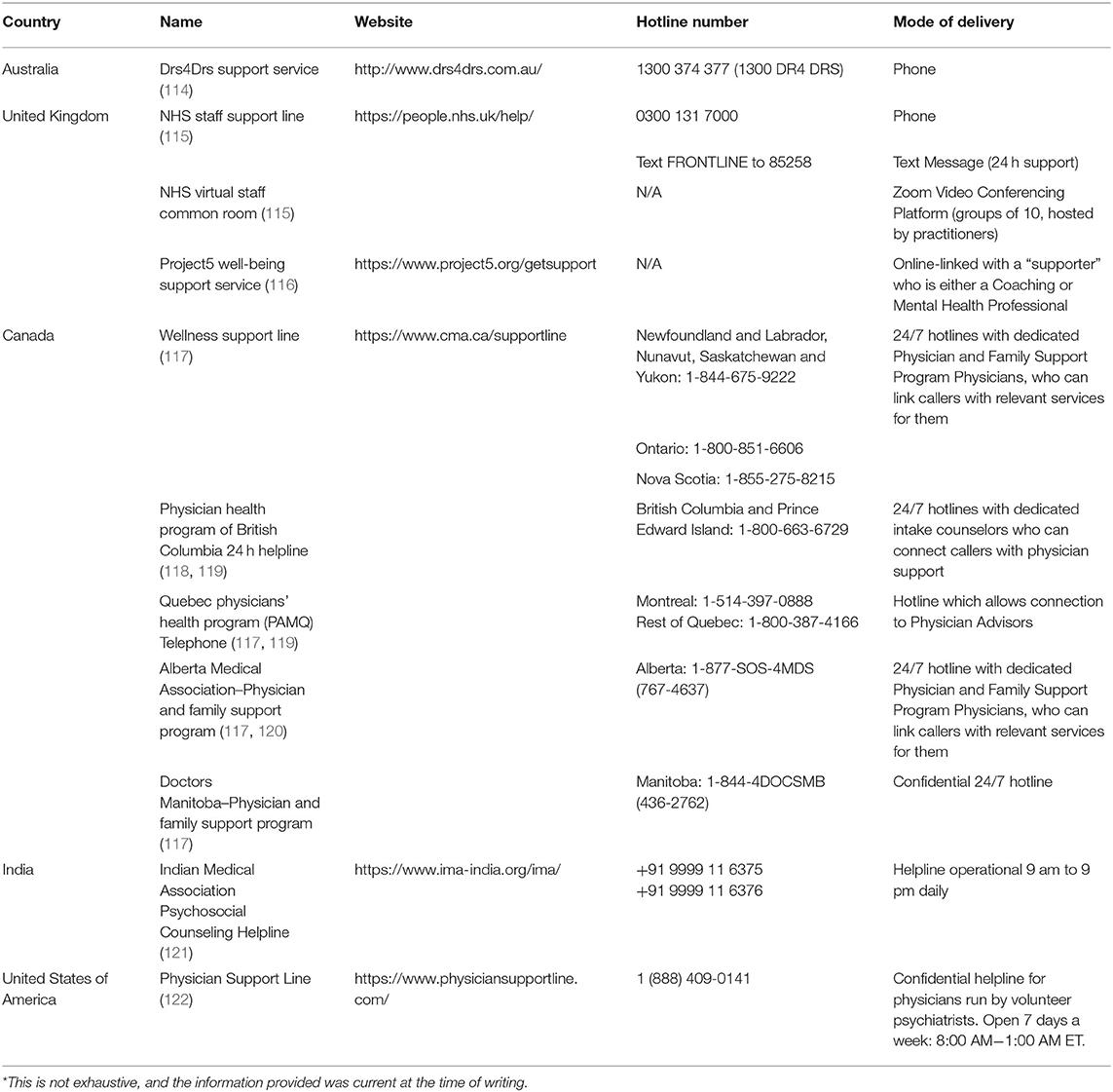

During COVID-19. Considering increasing reports of mental health consequences of the pandemic on medical students and trainees, telemedicine can be harnessed to provide constant support to these individuals and resultantly safeguard our future generations of medical professionals from longer-term sequelae. Confidentiality would be crucial to such a system, as many individuals, particularly those from minority groups, are reluctant to share their vulnerabilities (61). Additionally, training psychologists and psychiatrists involved in this service about unique demands of different groups will be critical to providing personalized care (74). Several telepsychiatry and support services have been started worldwide (Table 3).

Table 3. Various support services available to doctors and medical students in various countries and regions*.

Additionally, CBT has been found to have utility for both depression and generalized anxiety disorder in university students. Although online CBT is not as effective as face-to-face equivalents, COVID-19 precautions and restrictions mean it is a useful way provide students with positive coping skills, and can bypass fears of stigma within medical student populations. Engagement has been problematic with online platforms in the past, and thus constant appraisal and remodeling are critical (123–125).

Beyond COVID-19. Maintenance of such telemedicine services provide medical students and trainees with a convenient and accessible outlet for any mental health concerns they may have and resultantly can assist in early identification or prevention of longer-term impacts of known stressors associated with the medical profession (95). Additionally, normalizing health-seeking behaviors through supportive rhetoric can help overcome barriers related to stigma (51).

Increase Accessibility to Support Services

During COVID-19. Support services are being implemented for vulnerable students. For instance, the NSW state government in Australia has provided funding for crisis accommodation for international students under financial duress due to the COVID-19 pandemic (126). Informing students to whom such support mechanisms are relevant is pivotal, with use of social media, targeted mail-outs, and newsletter segments being possibilities.

Beyond COVID-19. Appraising and optimizing such targeted communication with student subgroups can make them feel more valued and allow early access to any support required. Additionally, incorporating student input into developing programs can make these more effective and targeted to their needs.

Minority groups may be unlikely to make complaints about harassment and bullying for fear of their complaint not being taken seriously or retaliation. To address this, and increase the accessibility of support, public statements of zero tolerance for bullying, harassment and discrimination should be made. Additionally, diversification of staff and complaints committees and incorporation of lived experience members may be useful in highlighting to students that their viewpoints and challenges will be respected and that they will get fair redressal for untoward experiences or incidents (67, 127).

In conclusion, medical students, the future of our healthcare system, are vulnerable during the current pandemic, with subgroups of medical students from specific backgrounds more impacted. Targeted support for these subgroups, and students overall, is warranted. COVID-19 has exposed systemic issues within our healthcare and education systems. Recognizing these issues and developing strategies to combat them is pivotal to our response to an infection outbreak in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

SB contributed to the planning, draft and revision of the manuscript supervision of the student, and encouraged DS to investigate and supervised the findings of this work. SB and DS wrote the first draft of this paper. Both authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to dedicate this work to our healthcare workers who have died due to COVID-19 while serving the patients at the frontline and to those who continue to serve during these challenging times despite lack of personal protective equipment.

References

1. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. (2020) 395:1417–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5

2. Bhaskar S, Rastogi A, Chattu VK, Adisesh A, Thomas P, Alvarado N, et al. Key strategies for clinical management and improvement of healthcare services for cardiovascular disease and diabetes patients in the coronavirus (COVID-19) settings: recommendations from the REPROGRAM consortium. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:112. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00112

3. Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. (2020) 323:2466–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598

4. Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Israeli-Korn S, Menon B, Chattu VK, Thomas P, et al. Chronic neurology in COVID-19 era: clinical considerations and recommendations from the REPROGRAM consortium. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:664. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00664

5. Bhaskar S, Sharma D, Walker AH, McDonald M, Huasen B, Haridas A, et al. Acute neurological care in the COVID-19 era: the pandemic health system REsilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) consortium pathway. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:579. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00579

6. Baker DM, Bhatia S, Brown S, Cambridge W, Kamarajah SK, McLean KA, et al. Medical student involvement in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. (2020) 395:1254. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30795-9

7. Liang S-W, Chen R-N, Liu L-L, Li X-G, Chen J-B, Tang S-Y, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on guangdong college students: the difference between seeking and not seeking psychological help. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:2231. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02231

8. Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2016) 316:2214–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324

9. Slade T, Johnston A, Teesson M, Whiteford H, Burgess P, Pirkis J, et al. The Mental Health of Australians 2: Report on the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. (2009). Available online at: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-m-mhaust2 (accessed July 31, 2020).

10. McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T editors. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital (2016). Available online at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey-survey-of-mental-health-and-wellbeing-england-2014 (accessed July 31, 2020).

11. National Institute of Mental Health. Statistics: National Institute of Mental Health. (2018). Available online at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/index.shtml (accessed July 31, 2020).

12. Wu F, Ireland M, Hafekost K, Lawrence D. National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students. Beyond Blue (2013). Available online at: https://www.beyondblue.org.au/about-us/our-work-in-improving-workplace-mental-health/health-services-program/national-mental-health-survey-of-doctors-and-medical-students (accessed July 31, 2020).

13. Bogowicz P, Ferguson J, Gilvarry E, Kamali F, Kaner E, Newbury-Birch D. Alcohol and other substance use among medical and law students at a UK university: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Postgrad Med J. (2018) 94:131–6. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135136

14. Jackson ER, Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Satele DV, Dyrbye LN. Burnout and alcohol abuse/dependence among U.S. medical students. Acad Med. (2016) 91:1251–6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001138

15. Billingsley M. More than 80% of medical students with mental health issues feel under-supported, says student BMJ survey. BMJ. (2015) 351:h4521. doi: 10.1136/sbmj.h4521

16. Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. (2014) 89:443–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

17. Olum R, Kajjimu J, Kanyike AM, Chekwech G, Wekha G, Nassozi DR, et al. Perspective of medical students on the COVID-19 pandemic: survey of nine medical schools in Uganda. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020) 6:e19847. doi: 10.2196/19847

18. Nguyen HT, Do BN, Pham KM, Kim GB, Dam HTB, Nguyen TT, et al. Fear of COVID-19 Scale-associations of its scores with health literacy and health-related behaviors among medical students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4164. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114164

19. Flotte TR, Larkin AC, Fischer MA, Chimienti SN, DeMarco DM, Fan P-Y, et al. Accelerated graduation and the deployment of new physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. (2020) 95:1492–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003540

20. Compton S, Sarraf-Yazdi S, Rustandy F, Radha Krishna LK. Medical students' preference for returning to the clinical setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Educ. (2020) 54:943–50. doi: 10.1111/medu.14268

21. Chandra S, Laoteppitaks C, Mingioni N, Papanagnou D. Zooming-out COVID-19: virtual clinical experiences in an emergency medicine clerkship. Med Educ. (2020). doi: 10.1111/medu.14266. [Epub ahead of print].

22. Collado-Boira EJ, Ruiz-Palomino E, Salas-Media P, Folch-Ayora A, Muriach M, Baliño P. “The COVID-19 outbreak” -an empirical phenomenological study on perceptions and psychosocial considerations surrounding the immediate incorporation of final-year Spanish nursing and medical students into the health system. Nurse Educ Today. (2020) 92:104504. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104504

23. Huckins JF, daSilva AW, Wang W, Hedlund E, Rogers C, Nepal SK, et al. Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the covid-19 pandemic: longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e20185. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/4enzm

24. Garcia RM, Reynolds RA, Weiss HK, Chambless LB, Lam S, Dahdaleh NS, et al. Letter: preliminary national survey results evaluating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on medical students pursuing careers in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. (2020) 87:E258–9. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa214

25. Khanna R, Honavar S, Metla A, Bhattacharya A, Maulik P. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ophthalmologists-in-training and practising ophthalmologists in India. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2020) 68:994–8. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1458_20

26. Zingaretti N, Contessi Negrini F, Tel A, Tresoldi MM, Bresadola V, Parodi PC. The impact of COVID-19 on plastic surgery residency training. Aesthetic Plast Surg. (2020) 44:1381–5. doi: 10.1007/s00266-020-01789-w

27. Taghrir MH, Borazjani R, Shiraly R. COVID-19 and Iranian medical students; a survey on their related-knowledge, preventive behaviors and risk perception. Arch Iran Med. (2020) 23:249–54. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.06

28. Guadix SW, Winston GM, Chae JK, Haghdel A, Chen J, Younus I, et al. Medical student concerns relating to neurosurgery education during COVID-19. World Neurosurg. (2020) 139:e836–47. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.090

29. Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J, Valdimarsdóttir UA, Fall K, Fang F, et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Med. (2020). doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001555. [Epub ahead of print].

30. Aker S, Midik Ö. The views of medical faculty students in turkey concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. J Community Health. (2020) 45:684–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00841-9

31. Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, Mahabadi MA, Bandari DK. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2020) 6:e19160. doi: 10.2196/19160

32. Liu J, Zhu Q, Fan W, Makamure J, Zheng C, Wang J. Online mental health survey in a medical college in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychiatry. (2020) 11:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00845

33. Khasawneh AI, Humeidan AA, Alsulaiman JW, Bloukh S, Ramadan M, Al-Shatanawi TN, et al. Medical students and COVID-19: knowledge, attitudes, and precautionary measures. a descriptive study from Jordan. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:253. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00253

34. Meo SA, Abukhalaf AA, Alomar AA, Sattar K, Klonoff DC. COVID-19 Pandemic: impact of quarantine on medical students' mental wellbeing and learning behaviors. Pak J Med Sci. (2020) 36:S43–8. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2809

35. Abbasi S, Ayoob T, Malik A, Memon SI. Perceptions of students regarding E-learning during Covid-19 at a private medical college. Pak J Med Sci. (2020) 36:S57–61. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2766

36. Sethi BA, Sethi A, Ali S, Aamir HS. Impact of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals. Pak J Med Sci. (2020) 36:S6–S11. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2779

37. Ikhlaq A, Bint-E-Riaz H, Bashir I, Ijaz F. Awareness and attitude of undergraduate medical students towards 2019-novel corona virus. Pak J Med Sci. (2020) 36:S32–6. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2636

38. Lin Y, Hu Z, Alias H, Wong LP. Influence of mass and social media on psychobehavioral responses among medical students during the downward trend of COVID-19 in Fujian, China: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e19982. doi: 10.2196/19982

39. Choi B, Jegatheeswaran L, Minocha A, Alhilani M, Nakhoul M, Mutengesa E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: a national survey. BMC Med Educ. (2020) 20:206. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02117-1

40. Çalişkan F, Midik Ö, Baykan Z, Senol Y, Tanriverdi EÇ, Tengiz FI, et al. The knowledge level and perceptions toward COVID-19 among Turkish final year medical students. Postgraduate Med. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1795486. [Epub ahead of print].

41. Termorshuizen JD, Watson HJ, Thornton LM, Borg S, Flatt RE, MacDermod CM, et al. Early impact of COVID-19 on individuals with self-reported eating disorders: a survey of ~1,000 individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. Int J Eat Disord. (2020). doi: 10.1002/eat.23353. [Epub ahead of print].

42. Akers A, Blough C, Iyer MS. COVID-19 implications on clinical clerkships and the residency application process for medical students. Cureus. (2020) 12:e7800. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7800

43. Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. (2020) 323:2131–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227

44. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Important Guidance for Medical Students on Clinical Rotations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak. AAMC (2020). Available online at: https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/important-guidance-medical-students-clinical-rotations-during-coronavirus-covid-19-outbreak (accessed July 31, 2020).

45. Zou D. COVID-19: Implications for Medical Students. The Medical Journal of Australia (2020). Available online at: https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2020/12/covid-19-implications-for-medical-students/ (accessed July 31, 2020).

46. Dedeilia A, Sotiropoulos MG, Hanrahan JG, Janga D, Dedeilias P, Sideris M. Medical and surgical education challenges and innovations in the covid-19 era: a systematic review. In Vivo. (2020) 34(Suppl. 3):1603–11. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11950

47. Franchi T. The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on current anatomy education and future careers: a student's perspective. Anat Sci Educ. (2020) 13:312–5. doi: 10.1002/ase.1966

48. Kapila AK, Schettino M, Farid Y, Ortiz S, Hamdi M. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on plastic surgery training: the resident perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. (2020) 8:e3054. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003054

49. Mian A, Khan S. Medical education during pandemics: a UK perspective. BMC Med. (2020) 18:100. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01577-y

50. Kaparounaki CK, Patsali ME, Mousa D-PV, Papadopoulou EVK, Papadopoulou KKK, Fountoulakis KN. University students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 290:113111. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111

51. Suwalska J, Suwalska A, Szczygieł M, Łojko D. Medical students and stigma of depression. Part 2. Self-stigma. Psychiatr Pol. (2017) 51:503–13. doi: 10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/67373

52. Usher K, Bhullar N, Jackson D. Life in the pandemic: social isolation and mental health. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:2756–7. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15290

53. Phillipou A, Meyer D, Neill E, Tan EJ, Toh WL, Van Rheenen TE, et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project. Int J Eat Disord. (2020) 53:1158–65. doi: 10.1002/eat.23317

54. Jahrami H, Sater M, Abdulla A, Faris MeA-I, AlAnsari A. Eating disorders risk among medical students: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. (2019) 24:397–410. doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0516-z

55. Fernández-Aranda F, Casas M, Claes L, Bryan DC, Favaro A, Granero R, et al. COVID-19 and implications for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. (2020) 28:239–45. doi: 10.1002/erv.2738

56. Touyz S, Lacey H, Hay P. Eating disorders in the time of COVID-19. J Eat Disord. (2020) 8:19. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00295-3

57. UNESCO. Universities tackle the impact of COVID-19 on disadvantaged students Paris, France. (2020). Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/news/universities-tackle-impact-covid-19-disadvantaged-students (accessed July 31, 2020).

58. Pather N, Blyth P, Chapman JA, Dayal MR, Flack NAMS, Fogg QA, et al. Forced disruption of anatomy education in Australia and New Zealand: an acute response to the covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. (2020) 13:284–300. doi: 10.1002/ase.1968

59. Aghakhani K, Shalbafan M. What COVID-19 outbreak in Iran teaches us about virtual medical education. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1770567. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1770567

60. Sahi PK, Mishra D, Singh T. Medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Pediatr. (2020) 57:652–7. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1894-7

61. Najibi S, Carney PA, Thayer EK, Deiorio NM. Differences in coaching needs among underrepresented minority medical students. Fam Med. (2019) 51:516–22. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.100305

62. Low D, Pollack SW, Liao ZC, Maestas R, Kirven LE, Eacker AM, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in clinical grading in medical school. Teach Learn Med. (2019) 31:487–96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1597724

63. Hill KA, Samuels EA, Gross CP, Desai MM, Sitkin Zelin N, Latimore D, et al. Assessment of the prevalence of medical student mistreatment by sex, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:653–65. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0030

64. Ajilore O, Thames AD. The fire this time: the stress of racism, inflammation and COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. (2020) 88:66–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.003

65. Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, et al. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2020) 14:779–88. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.035

66. Rzymski P, Nowicki M. COVID-19-related prejudice toward Asian medical students: a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 fears in Poland. J Infect Public Health. (2020) 13:873–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.013

67. Kmietowicz Z. Are medical schools turning a blind eye to racism? BMJ. (2020) 368:m420. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m420

68. Rosa WE, Shook A, Acquaviva KD. LGBTQ+ inclusive palliative care in the context of COVID-19: pragmatic recommendations for clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2020) 60:e44–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.155

69. Bupa. Mental Wellbeing Survey of Prospective International and Overseas Students. (2019). Available online at: https://aiec.idp.com/uploads/AIEC_2019/Proceedings/AIEC2019_231_1013_Tomyn_Ngyen.pdf (accessed July 31, 2020).

70. Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. (2020) 12:e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541

71. Australian Government Department of Health. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Advice for Travellers: Commonwealth of Australia. (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-advice-for-travellers (accessed July 31, 2020).

72. Zhang J, Paksarian D, Lamers F, Hickie IB, He J, Merikangas KR. Sleep patterns and mental health correlates in US adolescents. J Pediatr. (2017) 182:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.007

73. Smith CA. Covid-19: healthcare students face unique mental health challenges. BMJ. (2020) 369:m2491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2491

74. Zhai Y, Du X. Mental health care for international Chinese students affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:e22. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30089-4

75. Bentata Y. The COVID-19 pandemic and international federation of medical students' association exchanges: thousands of students deprived of their clinical and research exchanges. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1783784. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1783784

76. Parisi MCR, Frutuoso L, Benevides SSN, Barreira NHM, Silva JLG, Pereira MC, et al. The challenges and benefits of online teaching about diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2020) 14:575–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.043

77. Khadjooi K, Scott P, Jones L. What is the impact of pregnancy and parenthood on studying medicine? Exploring attitudes and experiences of medical students. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. (2012) 42:106–10. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2012.203

78. Arowoshola L. Medical education engagement during the COVID-19 era–a student parents perspective. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1788799. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1788799

79. Klasen JM, Vithyapathy A, Zante B, Burm S. “The storm has arrived”: the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on medical students. Perspect Med Educ. (2020) 9:181–5. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00592-2

80. Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Chattu VK, Adisesh A, Nurtazina A, Kyrykbayeva S, et al. Telemedicine as the new outpatient clinic gone digital: position paper from the pandemic health system REsilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) international consortium (part 2). Front Public Health. (2020) 8:410. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00410

81. Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Chattu VK, Adisesh A, Nurtazina A, Kyrykbayeva S, et al. Telemedicine across the globe - position paper from the COVID-19 pandemic health system resilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) international consortium (Part 1). Front Public Health. (2020) 8:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.556720

82. Bhaskar S, Bradley S, Sakhamuri S, Moguilner S, Chattu VK, Pandya S, et al. Designing futuristic telemedicine using artificial intelligence and robotics in the COVID-19 era. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:556789. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.556789

83. Bhaskar S, Sinha A, Banach M, Mittoo S, Weissert R, Kass JS, et al. Cytokine storm in COVID-19—immunopathological mechanisms, clinical considerations, and therapeutic approaches: the REPROGRAM consortium position paper. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1648. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01648

84. Ruthberg JS, Quereshy HA, Ahmadmehrabi S, Trudeau S, Chaudry E, Hair B, et al. A multimodal multi-institutional solution to remote medical student education for otolaryngology during COVID-19. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2020) 163:707–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599820933599

85. Moszkowicz D, Duboc H, Dubertret C, Roux D, Bretagnol F. Daily medical education for confined students during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a simple videoconference solution. Clin Anat. (2020) 33:927–8. doi: 10.1002/ca.23601

86. Singh K, Srivastav S, Bhardwaj A, Dixit A, Misra S. Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a single institution experience. Indian Pediatr. (2020) 57:678–9. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1899-2

87. Hoopes S, Pham T, Lindo FM, Antosh DD. Home surgical skill training resources for obstetrics and gynecology trainees during a pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. (2020) 136:56–64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003931

88. Chandratre S. Medical students and COVID-19: challenges and supportive strategies. J Med Educ Curric Dev. (2020) 7:2382120520935059. doi: 10.1177/2382120520935059

89. Lapolla P, Mingoli A. COVID-19 changes medical education in Italy: will other countries follow? Postgrad Med J. (2020) 96:375. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137876

90. Wang JHS, Tan S, Raubenheimer K. Rethinking the role of senior medical students in the COVID-19 response. Med J Aust. (2020) 212:490.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50601

91. Australian Medical Students Association (AAMC). Coronavirus (Covid-19) Medical Student Public Hospital Engagement Contract Offer Checklist. AAMC (2020). Available online at: https://ama.com.au/article/COVID_19_Medical_Student_Public_Hospital_Engagement (accessed July 31, 2020).

92. Sandhu P, de Wolf M. The impact of COVID-19 on the undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1764740. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1764740

93. Zaed I. COVID-19 consequences on medical students interested in neurosurgery: an Italian perspective. Br J Neurosurg. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2020.1777260. [Epub ahead of print].

94. Boodman C, Lee S, Bullard J. Idle medical students review emerging COVID-19 research. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1770562. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1770562

95. Sklar DP. COVID-19: lessons from the disaster that can improve health professions education. Acad Med. (2020) 95:1631–3. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003547

96. Ashcroft J, Byrne MHV, Brennan PA, Davies RJ. Preparing medical students for a pandemic: a systematic review of student disaster training programmes. Postgrad Med J. (2020). doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137906. [Epub ahead of print].

97. Iancu AM, Kemp MT, Alam HB. Unmuting medical students' education: utilizing telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e19667. doi: 10.2196/19667

98. Singal A, Bansal A, Chaudhary P. Cadaverless anatomy: darkness in the times of pandemic Covid-19. Morphologie. (2020) 104:147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.morpho.2020.05.003

99. Dawidziuk A, Gandhewar R. Preparing medical students for global challenges beyond COVID-19. Health Sci Rep. (2020) 3:e162. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.162

100. Roll R, Chiu M, Huang C. Answering the call to action: COVID-19 curriculum design by students for students. Acad Med. (2020) 95:e6. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003588

101. Bond KS, Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, Reavley NJ. Mental health first aid training for Australian medical and nursing students: an evaluation study. BMC Psychol. (2015) 3:11. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0069-0

102. Davies EB, Beever E, Glazebrook C. A pilot randomised controlled study of the mental health first aid eLearning course with UK medical students. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:45. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1154-x

103. Australian Goverment Department of Health. Mental Health First Aid Training for Medical Students. Commonwealth of Australia (2020). Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/mental-health-first-aid-training-for-medical-students (accessed July 31, 2020).

104. Finn GM, Brown MEL, Laughey W, Dueñas A. #pandemicpedagogy: using twitter for knowledge exchange. Med Educ. (2020). doi: 10.1111/medu.14242. [Epub ahead of print].

105. American College of Surgeons (ACS). Medical Student Core Curriculum Chicago: American College of Surgeons. (2020). Available online at: https://www.facs.org/education/program/core-curriculum?fbclid=IwAR2Sb7rSQ7MZHtCEPfRxiKTgg_1JaIZ9zynu5XozzgA53TSPs7pi63qAUKQ (accessed July 31, 2020).

106. Haines MJ, Yu ACM, Ching G, Kestler M. Integrating a COVID-19 volunteer response into a year-3 md curriculum. Med Educ. (2020) 54:960–1. doi: 10.1111/medu.14254

107. Miller DG, Pierson L, Doernberg S. The role of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:145–6. doi: 10.7326/M20-1281

108. Cerqueira-Silva T, Carreiro R, Nunes V, Passos L, Canedo B, Andrade S, et al. Bridging Learning in Medicine and Citizenship During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Telehealth-Based Strategy. (2020). Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3625871 (accessed July 31, 2020).

109. Santos JJ, Chang DD, Robbins KK, Cam EL, Garbuzov A, Miyakawa-Liu M, et al. Answering the call: medical students reinforce health system frontlines through ochsner COVID-19 hotline. Ochsner J. (2020) 20:144. doi: 10.31486/toj.20.0065

110. Abedi M, Abedi D. A letter to the editor: the impact of COVID-19 on intercalating and non-clinical medical students in the UK. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1771245. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1771245

111. Rastegar Kazerooni A, Amini M, Tabari P, Moosavi M. Peer mentoring for medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic via a social media platform. Med Educ. (2020) 54:762–3. doi: 10.1111/medu.14206

112. Huddart D, Hirniak J, Sethi R, Hayer G, Dibblin C, Meghna Rao B, et al. #MedStudentCovid: how social media is supporting students during COVID-19. Med Educ. (2020) 54:951–2. doi: 10.1111/medu.14215

113. Roberts V, Malone K, Moore P, Russell-Webster T, Caulfield R. Peer teaching medical students during a pandemic. Med Educ Online. (2020) 25:1772014. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1772014

114. Australian Medical Association Limited. New Free, Confidential Mental Health Counselling Service for Doctors and Medical Students. (2020). Available online at: https://ama.com.au/gp-network-news/new-free-confidential-mental-health-counselling-service (accessed July 31, 2020).

115. NHS. Support Now: NHS Leadership Academy. (2020). Available online at: https://people.nhs.uk/help/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

116. Project5.org. Access Support-for NHS Staff. (2020). Available online at: https://www.project5.org/getsupport (accessed July 31, 2020).

117. Canadian Medical Association. Support Line. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cma.ca/supportline (accessed July 15, 2020).

118. Physician Health Program. Physician Health Program of British Columbia. (2020). Available online at: https://www.physicianhealth.com/about-us (accessed July 15, 2020).

119. Quebec Physicians' Health Program (PAMQ). PAMQ. (2020). Available online at: http://www.pamq.org/en (accessed July 15, 2020).

120. Alberta Medical Association. Physician and Family Support Program: Alberta Medical Association. (2020). Available online at: https://www.albertadoctors.org/services/pfsp (accessed July 31, 2020).

121. Indian Medical Association. IMA. (2020). Available online at: https://www.ima-india.org/ima/index.php (accessed July 31, 2020).

122. Physician Support Line USA. United States of America: Physician Support Line. (2020). Available online at: https://www.physiciansupportline.com/ (accessed July 31, 2020).

123. Howell AN, Rheingold AA, Uhde TW, Guille C. Web-based CBT for the prevention of anxiety symptoms among medical and health science graduate students. Cogn Behav Ther. (2019) 48:385–405. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2018.1533575

124. Huang J, Nigatu YT, Smail-Crevier R, Zhang X, Wang J. Interventions for common mental health problems among university and college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 107:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.09.018

125. Lattie EG, Kashima K, Duffecy JL. An open trial of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for first year medical students. Internet Interv. (2019) 18:100279. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100279

126. Service NSW. (2020). International student COVID-19 crisis accommodation–guidelines. Available online at: https://www.service.nsw.gov.au/international-student-covid-19-crisis-accommodation-guidelines (accessed July 1, 2020).

Keywords: medical education, training, remote delivery, tele-education, telemedicine, technologies, digital humanities, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

Citation: Sharma D and Bhaskar S (2020) Addressing the Covid-19 Burden on Medical Education and Training: The Role of Telemedicine and Tele-Education During and Beyond the Pandemic. Front. Public Health 8:589669. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.589669

Received: 31 July 2020; Accepted: 06 November 2020;

Published: 27 November 2020.

Edited by:

Andreea Molnar, Swinburne University of Technology, AustraliaReviewed by:

M. Mahbub Hossain, Texas A&M University, United StatesLaszlo Balkanyi, University of Pannonia, Hungary

Copyright © 2020 Sharma and Bhaskar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sonu Bhaskar, U29udS5CaGFza2FyQGhlYWx0aC5uc3cuZ292LmF1

Divyansh Sharma

Divyansh Sharma Sonu Bhaskar

Sonu Bhaskar