- 1Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States

- 2Bennett-Pierce Prevention Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

- 3Biobehavioral Health and Medicine, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

- 4Department of Psychology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States

Incorporating technological supplements into existing group mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), particularly for use with adolescents, is an important next step in the implementation of MBIs. Yet there is little available content. Herein we present the development and content of a technological supplement for MBIs, which incorporates multiple technological elements to support (a) skill transfer from the group MBI to daily life, (b) the establishment of a formal mindfulness practice, and (c) the use of mindfulness during periods of high stress. A mixed-methods approach was used to develop this multi-method adaptive supplement. Findings about the use of this supplement will be disseminated scientifically and/or publicly as appropriate.

Introduction

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) provide participants with opportunities to practice cultivating attention to the present moment with non-judgment, and have a robust and growing evidence base to support their use, particularly for adults [e.g., (1–4)]. MBIs are also well-liked by and effective for adolescents, and improve not only mindfulness but also emotion regulation and coping, as well as decrease internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and sleep problems (5–12).

Empirical studies have begun to explore stand-alone brief and online MBIs [e.g., (13)], and suggest that they can be effective [e.g., (14)]. However, to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated technological supplements to an in-person MBI. We have argued elsewhere that, particularly when working to increase mindfulness in adolescence, a critical next step in MBI implementation science is to utilize a mobile-technology-enhanced MBI; i.e., to incorporate technological supplements into an existing MBI (15). In the current paper, we detail the development and content of just such a mobile-technology-enhanced MBI to promote mindfulness in adolescent populations.

The Case for Incorporating Technology Into an MBI for Adolescents

Over the last several decades, mental health problems (16), and levels of stress (17) during adolescence have risen dramatically, such that adolescents now report levels of stress that are similar to those reported by adults (17). Although there are fewer studies evaluating the effects of MBI on adolescents than those evaluating the effects on adults, work focusing on adolescents indicates that MBIs improve mental health in both clinical and non-clinical samples, relative to active controls (18), and with effects that persist beyond program cessation (19).

A critical part of MBIs is encouraging participants to transfer skills learned in the program into their daily life, with emphasis on the necessity of a regular mindfulness practice in order to experience benefits for well-being [e.g., (20)]. This emphasis is supported by empirical work which suggests that the time spent practicing mindfulness between in-person sessions predicts improvements in both mindfulness and mental health (21). Furthermore, associations between mindfulness practice time and subsequent mental health are mediated by increases in mindfulness (21). However, adolescent participants in MBIs typically have very low levels of compliance with home practice recommendations. For instance, on average, adolescents engage in home practice on only about ¼ of the days they are encouraged to by intervention facilitators (22).

Based on this research, there appears to be a need to increase home practice and skill transfer for adolescents participating in MBIs. An accompanying body of literature suggests that technological tools are a very effective way to support skill transfer, particularly for adolescents. In particular, mobile technology (i.e., cell phones) has become widely incorporated into adolescent daily life (23). Most (i.e., >78%) of adolescents own mobile phones (23), with rates of cell phone ownership that are relatively equal across ethnic and socioeconomic groups (23, 24). Adolescents communicate more frequently over text than face-to-face and also endorse text as their preferred method of communication, sending a median of 60 text messages a day (25, 26). Therefore, not only is the ownership of mobile phones among adolescents almost ubiquitous, there is a seamless integration of mobile devices into the lives of adolescents. Therefore, intervention content (structured or unstructured) can be delivered via mobile technology in ecologically valid ways, in people's daily lives and natural settings. Such approaches are called ecological momentary interventions, or EMI (27). Interventions that incorporate EMI may be more likely to result in lasting behavioral and mental health change for adolescents (27, 28) because they are well-liked by adolescents (28–30), are easily assimilated into daily life for adolescents (28), and strongly support skill transfer by offering intervention content during daily life when adolescents are more likely to apply their developing skills (27). In addition, EMI components are highly flexible, and can be delivered on a pre-programmed schedule or in response to real-time participant data reflecting moments or high need (31). As such, there is a clear opportunity to leverage technology as a means of “meeting teens where they are” as digital natives to enhance engagement and home practice, in order to improve outcomes for adolescents.

Although EMIs can be stand-alone interventions or supplements to existing intervention strategies (27), there are multiple lines of evidence that converge to suggest that it may be optimal to combine EMI elements with other mindfulness intervention elements. Notably, EMI are often more efficacious when they are combined with other treatment strategies (e.g., in-person and/or group treatment) rather than when used as a stand-alone intervention (27). For instance, research in education suggests that EMI supplements enhance the effect of in-person educational interventions (32), though EMI supplements have not been tested in mindfulness interventions. Furthermore, many scholars and practitioners argue that the interpersonal and group dynamic of in-person MBIs are a very important part of the intervention [e.g., (20)]. However, studies examining technological approaches to increasing mindfulness have almost exclusively focused on stand-alone MBIs. These studies indicate that MBIs delivered online, through self-help or individually guided learning, or through a smartphone application, can increase mindfulness and lower psychological symptoms (13, 14, 33–38). Therefore, despite potential challenges of incorporating technology into an MBI [for a review, see (15)], we argue that an important next step in the implementation of MBIs is to incorporate an EMI, particularly when working to increase adolescent mindfulness. In the current paper, we discuss the development and content of a multi-method, adaptive supplement to an evidence-based MBI for adolescents.

Learning to Breathe: The Adolescent MBI to Supplement

Our focus on adolescence meant it was important for us to select a developmentally appropriate MBI as the foundation for an EMI supplement. In addition to increases in mental health problems during adolescence (16), the challenges of treating adolescents' mental health problems may be due in part to the use of treatment strategies that have not adequately taken into account the unique developmental characteristics of adolescence (39). There is growing evidence to support the effectiveness of Learning to BREATHE (L2B) (6), an MBI that is rooted in the philosophy of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR; 20) but developed to be developmentally sensitive to the unique characteristics of adolescence (40). The program was developed based on the same meditative training tradition approach used in MBSR (practicing cultivating attention that is purposeful, present-focused, open and non-reactive), as well as the based on the same three families of practices: focused attention (e.g., awareness of breath), open awareness (i.e., awareness of bodily sensations, thoughts, and feelings as they occur), and compassion (i.e., loving kindness and compassion for self and others). However, L2B was further tailored to: (1) support adolescent empowerment, autonomy, and self-efficacy in the face of stress; (2) build adolescent skills for emotion regulation, a key developmental task of adolescence; (3) encourage group cohesion by focusing on the common experiences of adolescents; (4) reduce tendencies for social comparison and self-judgment; and, (5) encourage peer acceptance and support via shared practice and activities. Therefore, it is a developmentally sensitive MBI. In addition, L2B is well-liked by adolescents and increases mindfulness as well as emotion regulation while it reduces stress, internalizing symptoms, and externalizing behaviors (5–12).

L2B is built to support practice and learning of six core themes built around the acronym BREATHE: Body, Reflections, Emotions, Attention, Tenderness, and Habits, all building to the overall program goal of Empowerment. These themes can be delivered in 6, 12, or 18 sessions, and in schools or in the community [see (41) for more details]. For the purposes of our work, we have implemented the 6-session version of L2B, although given the overlap in progression and content between the 6, 12, and 18 session programs, and the flexibility of the “Plus” component, “Plus” could effectively be used to support the longer programs as well, with relatively minor modifications. In this paper, we describe the combined intervention strategy of in-person L2B plus the multi-method adaptive supplement that we designed, or L2B Plus.

Elements of L2B Plus

The philosophy guiding the development of L2B Plus was to supplement the L2B group program with multiple methods of support for practicing mindfulness in daily life and particularly during times of high need, in ways that augment and are consistent with each L2B theme/lesson. We developed multiple methods to accomplish the interconnected goals: (1) support for establishing a formal mindfulness practice; (2) support for practicing formal and informal mindfulness practices in daily life, and (3) support for using mindfulness in moments of high need (which requires first identifying those moments when support is highly needed).

Adolescents participating in L2B are encouraged to engage in practices that are both formal (intentional time set aside for a mindfulness practice; those included in L2B are similar to those for adults such as a body scan, but often of a shorter length, as is more appropriate for adolescents) and informal (e.g., paying attention to breathing throughout the day, noticing sensations in the body when emotions become dysregulated). Both formal and informal practices are important: for instance, for adults, time spent in formal (but not informal) mindfulness practice predicts increases in mindfulness as well as improvements in mental health (21), whereas informal practices are believed to be critical for transferring the skills from formal practices into real life (20). When individuals are first developing a mindfulness practice, it is typical and helpful to follow guided mindfulness practices.

First, to support participants establishing a formal mindfulness practice, we developed an extensive on-demand library of educational materials and guided mindfulness practices, consistent with the content of L2B. In L2B, like other MBIs, brief didactic teachings are used to help adolescents learn about mindfulness and its benefits and are intended to help participants apply these skills in their lives. To extend and deepen these teachings, we included supplemental, developmentally appropriate education about mindfulness in our extensive on-demand library.

Second, we developed a set of messages that can be sent to adolescents (via text message or push notifications) to support practicing mindfulness in daily life both formally and informally (i.e., an intervention text message bank). Using previous theory and evidence, we developed three different types of text messages (reminders, motivational, and self-efficacy). As noted, adolescent compliance with home mindfulness practice recommendations is generally poor (22); it is unclear, however, what specific roadblocks to home practice adolescents experience. Some anecdotal data from our own L2B facilitation suggests that one important roadblock to developing a regular mindfulness practice is remembering to practice. For instance, at the beginning of each L2B meeting after the first, adolescents are invited to share things that have been going well and things that have been challenging in terms of practicing mindfulness at home. Adolescents often share that they forgot to practice, and/or what exactly they were supposed to be practicing. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, many report appreciating a homework assignment called “three dots” in which they are provided with three colored stickers, and instructed to place them in visible places. Then, each time they see a dot, they are instructed to take three mindful breaths. Therefore, the first category of messages we developed to support the development of a regular mindfulness practice was reminders about what adolescents learned in that week's lesson and what would be beneficial to practice.

The broader literature on behavior change suggests several other possible challenges to the process of beginning to incorporate mindfulness into daily life, namely low levels of motivation and/or self-efficacy (i.e., beliefs about one's ability to meet a goal or engage in a behavior). For instance, the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model, developed in relation to HIV risk behaviors (42) but much more widely applied in behavior change work (43), highlights issues of motivation and self-efficacy as modifiable factors that are central to creating and maintaining behavior change. Therefore, the second category of messages that were developed were motivational, or messages that reinforce the importance of developing a mindfulness practice (i.e., in what ways increasing mindfulness can be beneficial). In keeping with the IMB model, as well as extensive and consistent evidence that self-efficacy is a one of the strongest predictors of behavior change (44, 45), our third category of messages targeted increasing self-efficacy. These messages were positively framed, in keeping with evidence about what types of messages are most effective at increasing self-efficacy (46). Therefore, they focused on emphasizing that adolescents already had the skills and/or attributes to successfully establish a mindfulness practice, and how to expand upon those newly developing skills to establish other new, desirable habits.

Our third goal was to support using mindfulness particularly in moments of high need, which necessitates first identifying those moments of high need. The key mental and physical health benefits of mindfulness are theoretically rooted in its ability to buffer individuals from the negative consequences of stressful experiences (47). Therefore, we conceptualized “high need” as times of high stress (broadly defined) and/or low mindfulness. As a result, a key element of L2B Plus is ecological momentary assessments (EMA) that are used throughout the day to ask participants to report on their levels of stress/mindfulness so that intervention content can be delivered “just-in-time” (JIT) to real-time data from participants. These JIT messages were intended to support adolescents applying or using mindfulness (including self-compassion) during periods of high stress.

Methods

Creation of the On-Demand Library

Elsewhere, we provided a brief overview of the methods used to develop the on-demand library (48). Here, we provide further details about this development and fuller description of the content of this library. To develop the extensive on-demand library, we (1) conducted a thorough search of freely available online mindfulness education and practices using general mindfulness terms as well as keywords from L2B themes and major practices, and (2) identified gaps in this content and created new content to fill those gaps. Both the selection of existing and creation of new content followed the same basic decision rules and/or exclusion criteria. Content was selected if it did not include any of the following exclusion criteria, and was created to avoid each of the following: (1) technical problems (e.g., with sound quality); (2) free use not allowed; (3) explicit religious reference (in either language or imagery); (4) content that was not developmentally appropriate for adolescents; (5) length of >20 min; (6) unclear or confusing practice instructions (e.g., instructions that were contradictory or vague); (7) pedagogically inappropriate as a supplement to L2B (i.e., not reflective of L2B themes of practices taught in the group program; and, (8) inappropriate types of mental training (i.e., mantra meditations, visualizations, analytical meditation, relaxation training) that may have been very high-quality but are not part of L2B. In terms of this last criteria, as noted, L2B (like the meditative tradition used in MBSR) relies on three families of practices: focused attention, open awareness, and compassion practices. Other types of contemplative practices are important in other practice systems, and share similar goals with L2B/MBSR, but are not included in L2B. Therefore, they were also excluded from the “Plus” components, in order to reinforce what is taught in the group program and also to avoid confusion for participants. Finally, we identified and developed content that varied in length to provide participants with options that would be feasible for them to complete in a variety of situations and amounts of time.

Once content was identified and/or developed, the final step was to assign that content to the most appropriate L2B theme. This sorting was guided by the principle that students should have opportunities to independently (and in their daily life) practice skills that had already been introduced and practiced in the group program. In addition, in L2B, practices are scaffolded in a developmentally appropriate sequence. Therefore, the sorting of the on-demand library was completed in ways that provided students with practices that would match participants' level of understanding and ability (e.g., making sure concepts and techniques discussed in each practice did not go beyond what had already been introduced in class). As discussed in detail in the “Results” section, as with the progression of L2B, in the on-demand library, the practices that are available to participants in early weeks are limited primarily to focused attention on one object of attention (e.g., on breath or body), but in later sessions, participants focus on multiple objects of attention (e.g., body, thoughts, and feelings simultaneously).

Creation of the Intervention Message Bank

To create the intervention message bank (as well as inform timing of message delivery), 22 adolescents (3 cohorts of 3–13 members aged 12–18) participated in the full L2B program, and then at the end of each weekly session, participated in an activity that was designed to help with the development of this message bank. Written informed consent was obtained from parents as well as adolescents 17 years of age and older; written informed assent was obtained from all other adolescents. More specifically, at the end of each session, each adolescent was asked to work independently to write down one or two short sentences that could serve as reminders and/or encouragements to practice mindfulness during the week, based on the content of that week's session. In addition, at the end of the group program, they participated in a focus group to assess issues related to the timing of message delivery (e.g., times of day that would be helpful and not helpful to receive messages).

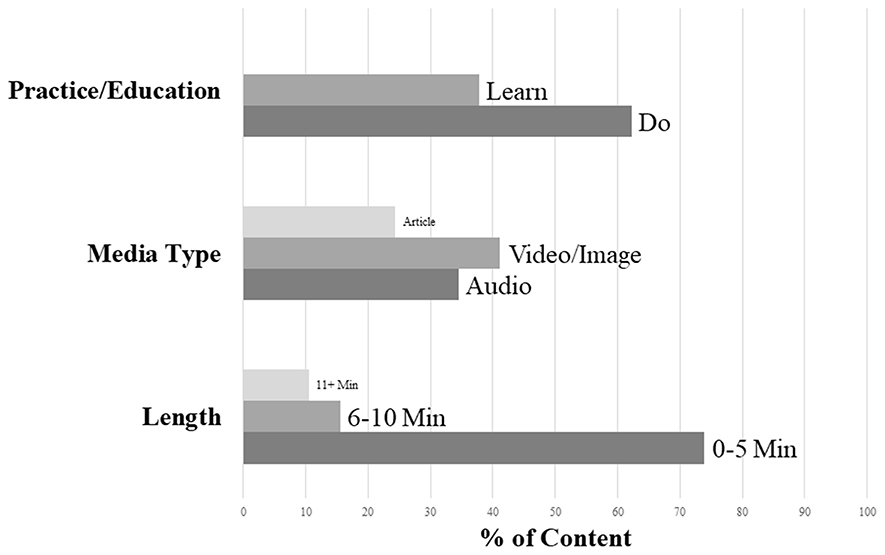

The study team carefully reviewed the pool of potential intervention messages to select and/or modify those that were the most in line with the goals of each particular session. The study team then developed additional messages to cover the most important themes of each individual lesson, making sure that each theme was represented in the categories of reminders, motivational, and self-efficacy messages (one-third of developed messages were from each category). Each topic of L2B was represented in the text messages with the exception of “habits,” as this lesson is the last day of the program and therefore participants do not receive EMI content following this session. To select which specific elements from each lesson to include in individual messages, we first identified the general theme of each session (taken from the L2B session manuals) and the main practice of the session, as well as practices secondary and/or tertiary practices (typically designed to support the main practice), if they were included in the session. As an example, the general message of the “A” lesson is, “Attention to body, thoughts, and feelings is good stress reduction;” the main practice of this session is mindful movement/mindful walking, the secondary practice is an activity to learn about stress, and the tertiary practice was a psychoeducational lesson regarding the interconnection of body, thoughts, and feelings. These essential messages as well as main, secondary, and tertiary practices were used to frame the messages in the message bank.

Creation of Just-in-Time Messages

Finally, the study team worked to create messages that were congruent with each L2B theme that would support practicing mindfulness in the face of stressful experiences. Messages were designed to be brief and general, so that they were applicable to a wide variety of possible unpleasant emotions and/or stressful experiences. These messages were intended to be stand-alone reminders about how to remain mindful even when feeling upset, stressed, or overwhelmed, so that participants might be better equipped to use mindfulness during moments of high need. Messages were framed compassionately, in line with the lessons of L2B. Each message also included links to two practices from the on-demand library that the study team identified as being helpful for enhancing mindfulness when under stress. Participants were given the opportunity to select one of the practices if interested and able to listen to one while they were struggling. One selected practice was very brief, and one was longer, to account for differences in the amount of time participants might have to engage in a practice.

Results

Overview

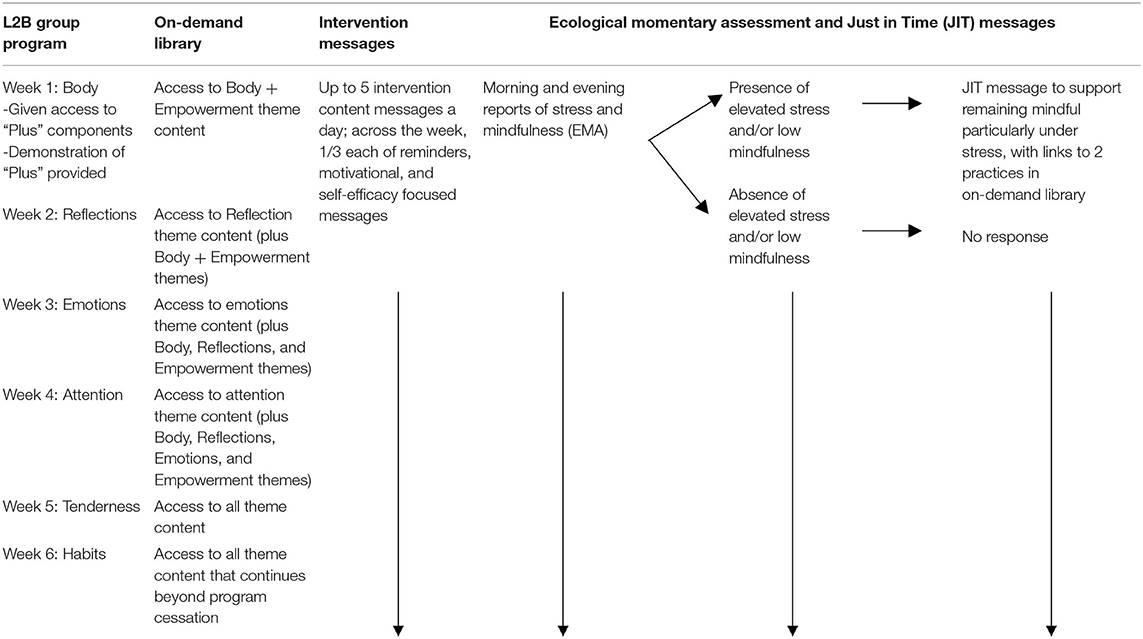

As our “Plus” components were designed to supplement the L2B group program (rather than to stand alone as a program), it is important to understand how the in-person and EMI elements are designed to fit together. An overview of the integration between the group program, on-demand library, intervention content messages, and EMA/JIT messages is provided in Table 1. As is evident in that table, after each week's content is introduced and practiced in the in-person group meeting, adolescents are given access to that week's content in the on-demand library (and are still given access to all of the previous weeks of content as well). The on-demand library also includes a recorded summary of each group meeting, so that students who miss a week can to some extent “catch up” on the material they missed. The day after the group meeting, adolescents also start receiving intervention content messages, as well as EMA to assess levels of stress and mindfulness, which can trigger the delivery of messages specifically designed to support remaining mindful when it is challenging. Both intervention content and JIT messages are tailored to that specific week of content (i.e., they focus on the theme discussed in the last week's group program). In the following sections, we provide more detail about each of the three important “Plus” components.

On-Demand Library

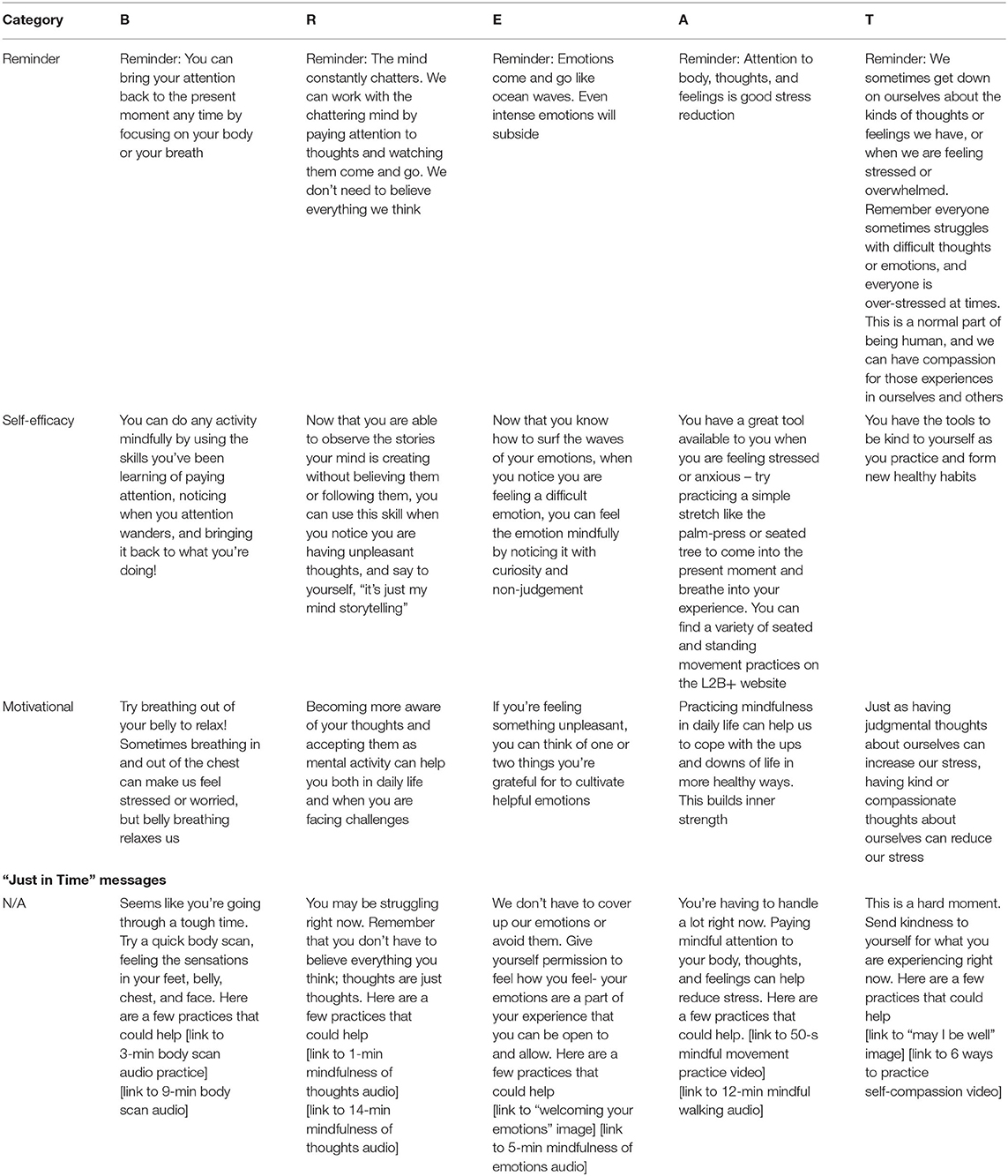

The on-demand library is a searchable database organized by weekly theme for the intervention. Themes become available as participants move through the in-person class sessions. For example, after the first session, participants are given access to the “B” theme and to the “Empowerment” theme. After the second session, participants are additionally given access to the “R” theme, and so on. After the last session, participants have access to all themes in the library. Content for each theme is targeted to the topics covered in class. See Figure 1 for information about the categories and quantity of content available for each theme.

Figure 1. Specific practices included in the on-demand library for each theme of L2B. Some types of practices are included in small amounts in multiple week of L2B. Where that is the case, the practices here have been grouped with the theme where most are included. “Person Just Like Me” is a compassion practice considered to be a core component of L2B. One “Person Just Like Me” practice occurs in each week of L2B, so it has not been grouped into a single theme.

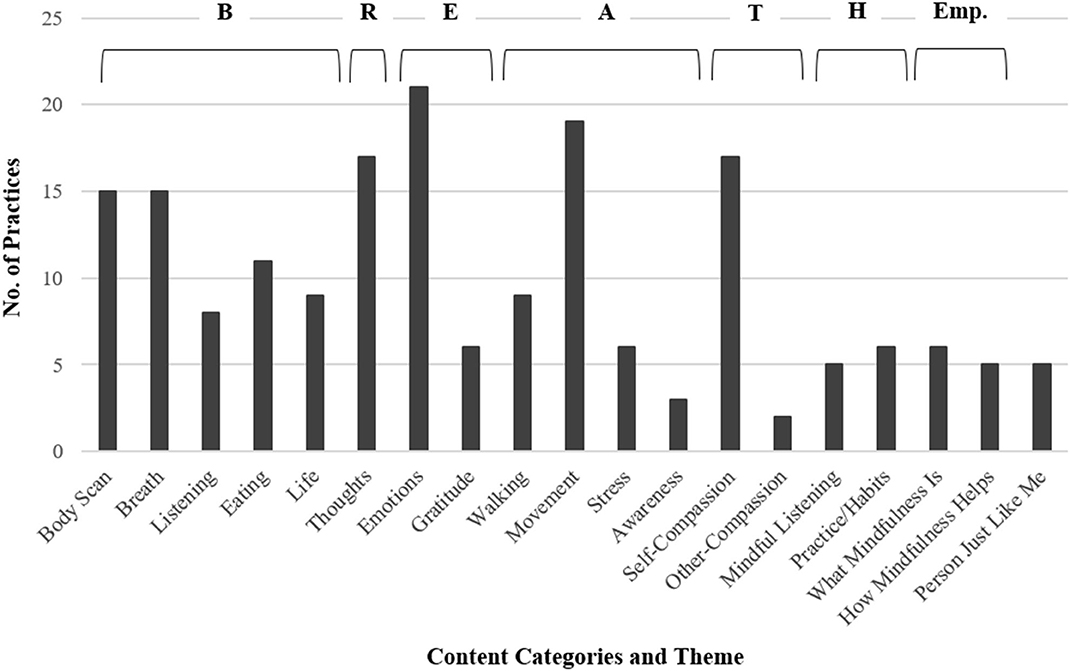

In light of evidence that user-centered digital interventions promote greater engagement (49), we allowed participants to self-tailor their content to promote greater practice. Participants are able to search the available library by (a) theme, (b) length of practice (0–5, 6–10, 11+min, and up to 20 min), and (c) type of activity (e.g., watch an educational video about mindfulness, do a listening audio practice, read more about mindfulness, follow a written practice, watch a mindfulness practice video). Participants can also rate activities and/or save their favorites to facilitate returning to them in the future. In addition to searching the database of activities, each week, the home page is also updated with a few recommended practices for the current theme, allowing participants to quickly find practices and instructional content related to their most recent class. The on-demand library provides a blend of audio, video/image, and reading content. The library also emphasizes brief practices (<20 min and particularly <5 min), in keeping with feedback from adolescents about how much time they are willing to practice at any given time, as well as the length of practices introduced in the group program. See Figure 2 for information about the distribution of lengths, media format, and practice or education type for library content across weeks.

Figure 2. Percentages of on-demand library content types by practice vs. education, length, and media type.

Intervention Content Messages

We designed intervention content messages to be sent several times a day to participants (see Table 2 for example intervention text messages of each type for each message). These messages are also designed to be distributed flexibly, based on the needs of individual samples, and to allow for adolescent self-tailoring of distribution times. Messages have been developed to send up to five intervention text messages every day; for instance, first thing in the morning (7:00 am), before school (9:00 am), at lunchtime (12:00 pm), right after school (4:00 pm), at dinnertime (6:00 pm), or at bedtime (9:00 pm). The specific timing of these messages was based on focus groups conducted with the 22 adolescents who participated in the full L2B program; these times were reported as being appropriate and helpful times to receive intervention messages. Message delivery is distributed throughout the week by message type (reminder, motivational, or self-efficacy) and key theme (general theme, main, second, or tertiary practice) following a set pattern. Reminder and self-efficacy message types are sent at different frequencies throughout the week, with reminders being sent most frequently earlier in the week and self-efficacy sent later in the week. Motivational messages are sent at a similar and consistent frequency throughout the week. This method was chosen in an effort to support the development of knowledge retention earlier in the week, and then new ideas for expanding newfound skills later in the week. It is our belief that participants must first focus on what mindfulness is and how to practice it (the content of reminder text messages), and then be supported to build confidence that they can increase their mindfulness (the content of self-efficacy messages), with information about why to practice mindfulness (in motivational messages) spread throughout the week. In addition, messages regarding main practices and essential themes are weighted more heavily toward the beginning of the week as a way of solidifying the most important ideas from the last session before moving on to a higher concentration of messages about secondary and tertiary practices toward the end of the week.

JIT Messages and the Ecological Momentary Assessments That Trigger Them

To provide support to adolescents in moments and contexts of high need, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) messages are sent to participants twice a day (first thing in the morning, and right before bed) to assess levels of stress and mindfulness. When respondents endorse relatively low levels of mindfulness [i.e., >30 on a scale from 1 (very mindLESS) to 100 (very mindFUL)] or high levels of stress [i.e., >70 on a scale from 0 (not stressed at all) to 100 (very stressed)], they are sent brief messages to acknowledge that they seem to be experiencing a challenging moment, and to provide a brief suggestion about ways to increase mindfulness in times of need. In addition, accompanying each brief message are direct links to two relevant practices in the on-demand library (see Table 2 for example JIT messages).

Dissemination of Product

These materials are available upon request from the first author.

Discussion

Our goal in this paper was to describe the development and content of a multi-method, adaptive supplement to an evidence-based MBI for adolescents. We have argued here and elsewhere (15) that it is critical to investigate supplements such as these to in-person, group mindfulness programs to better support skill transfer and the establishment of a regular mindfulness practice, particularly in adolescence. This assertion is based on evidence that MBIs are well-liked by and effective for adolescents (5–12), but effect sizes for MBIs are small-to-moderate and variable in size (5, 18), and compliance rates with home practice recommendations in adolescence are very poor (22).

The first step in investigating technological supplements to in-person mindfulness programs is the creation of a supplement that can augment and support what participants learn in the group program. We have aimed to do that with L2B Plus, described here, with multiple methods to support developing a formal mindfulness practice, applying mindfulness in daily life, and remaining mindful during periods of stress. The creation of this multi-method supplement is therefore a critical next step in the science of the implementation of MBIs. In future research, we intend to test the extent to which L2B Plus is a feasible and acceptable intervention approach for adolescents (48), explore whether L2B Plus seems effective to reduce adolescent stress and anxiety (48), identify the particular elements of the multiple Plus components that are the most effective at improving adolescent outcomes, and determine the extent to which there is specific added value in the Plus components over and above the in-person, group L2B program. Evidence that L2B Plus is feasible and acceptable, and that the multi-method supplement improves adolescent outcomes over and above the group program, would also suggest that clinical applications of L2B might benefit from incorporation of Plus components. Randomized controlled trials will be important to evaluate internal validity; in addition, community-based work with diverse samples will contribute critical information about generalizability.

Although originally developed for use in high school settings, L2B has been expanded to community settings (12) and also for use at different ages, including middle school and college aged students, as well as residents in senior living facilities. We believe that L2B Plus has great potential to support the development of a mindfulness practice in any setting, context, and age range that L2B is applied to, but it will be important to evaluate participant- and setting-level characteristics that increase or decrease feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of L2B Plus. For instance, because L2B Plus incorporates a multi-method supplement that is technologically based, individuals who do not have access to or are not comfortable with technology may experience barriers to engaging with L2B Plus. However, the broader literature on EMIs has dealt with these issues, and also provides evidence that even individuals uncomfortable with technology can benefit from EMIs, particularly with additional attempts to reduce fear of and increase comfort with technology (27). Although access to technology to support L2B Plus is another potential obstacle to its successful implementation, mobile phone, and/or tablet ownership is relatively equally distributed across racial/ethnic and socioeconomic groups, including in adolescence (23, 24). Therefore, EMI supplements typically do not create health disparities because of inequitable patterns of access to mobile technology, but instead may actually be a way to more equitably deliver treatment. In addition, this issue is also one that applies to the broader use of EMIs, and this broader work provides evidence-based solutions to problems with access to technology (e.g., providing mobile phone access to participants) (27). The L2B Plus approach, particularly with possibilities for self-tailoring that are built in, is in line with trends toward personalized prevention. By allowing choice and acknowledgment of unique needs for adolescents, this supplement is in keeping with personalized intervention methods to promote engagement and practice.

Our goal is to increase the efficacy of MBIs targeting adolescents through the development and, in the future, integration of technological support for skill transfer from an in-person MBI to daily life. It will be critical in future work to empirically evaluate the benefit of the multi-method adaptive supplement that we have described here, but its development is a crucial next step in the implementation of interventions to increase adolescent mindfulness.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Colorado State University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from parents as well as adolescents 17 years of age and older; written informed assent was obtained from all other adolescents.

Author Contributions

RL-T, SR, and NS wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. PB, JS, JC, and KH read and revised the manuscript. All authors were involved with study design, supplement development, and approved the publication of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by Award Number K01AT009592-01 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (PI, RL-T) as well as a Colorado State University Ventures Grant to Lucas-Thompson. Partial funding for open access publication fees were provided by a Colorado State University Open Access Research and Scholarship Fund.

Disclaimer

The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Conflict of Interest

PB receives a royalty from Learning 2 BREATHE when the manual is purchased.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. de Vibe M, Bjorndal A, Tipton E, Hammerstrom KT, Kowalski K. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life and social functioning in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Campell Syst Rev. (2017) 13:1–264. doi: 10.4073/csr.2017.11

2. Eberth J, Sedlmeier P. The effects of mindfulness meditation: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. (2012) 3:174–89. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0101-x

3. Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. J Psychos Res. (2004) 57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

4. Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2013) 33:763–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005

5. Bluth K, Campo RA, Pruteanu-Malinici S, Reams A, Mullarkey M, Broderick PC. A school-based mindfulness pilot study for ethnically diverse at-risk adolescents. Mindfulness. (2016) 7:90–104. doi: 10.1007/s12671-014-0376-1

6. Broderick PC, Metz S. Learning to BREATHE: a pilot trial of a mindfulness curriculum for adolescents. Adv School Mental Health Promot. (2009) 2:35–46. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2009.9715696

7. Dvorakova K, Kishida M, Li J, Elavsky S, Broderick PC, Agrusti MR, et al. Promoting healthy transition to college through mindfulness training with first-year college students: pilot randomized controlled trial. J Am College Health. (2017) 65:259–67. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2017.1278605

8. Eva AL, Thayer NM. Learning to BREATHE: a pilot study of a mindfulness-based intervention to support marginalized youth. J Evid Based Compl Alter Med. (2017) 22:580–91. doi: 10.1177/2156587217696928

9. Fung J, Guo SS, Jin J, Bear L, Lau A. A pilot randomized trial evaluating a school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth. Mindfulness. (2016) 7:819–28. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0519-7

10. Fung J, Kim JJ, Jin J, Chen G, Bear L, Lau AS. A randomized trial evaluating school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth: exploring mediators and moderators of intervention effects. J Abnormal Child Psychol. (2018) 47:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0425-7

11. Metz SM, Frank JL, Reibel D, Cantrell T, Sanders R, Broderick PC. The effectiveness of the learning to BREATHE program on adolescent emotion regulation. Res Hum Dev. (2013) 10:252–72. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2013.818488

12. Shomaker LB, Bruggink S, Pivarunas B, Skoranski A, Foss J, Chaffin E, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness-based group intervention in adolescent girls at risk for type 2 diabetes with depressive symptoms. Compl Ther Med. (2017) 32:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.04.003

13. Lindsay EK, Young SZ, Smyth JM, Brown KW, Creswell JD. Acceptance lowers stress reactivity: dismantling mindfulness training in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2018) 87:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.09.015

14. Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Cicconi F, Griffiths N, Wyper A, Jones F. A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behav Res. (2013) 51:573–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.06.003

15. Lucas-Thompson RG, Broderick PC, Coatsworth JD, Smyth JM. New avenues for promoting mindfulness in adolescence using mHealth. J Child Family Stud. (2018). doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1256-4

16. Collishaw S, Maughan B, Goodman R, Pickles A. Time trends in adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2004) 45:1350–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00335.x

17. American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association survey Shows Teen Stress Rivals That of Adults. (2014). American Psychological Association. Available online at: http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2014/02/teen-stress.aspx (retrieved on March 22, 2017).

18. Zoogman S, Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT, Miller L. Mindfulness interventions with youth: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness. (2014) 6:290–302. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0260-4

19. Klingbeil DA, Renshaw TL, Willenbrink JB, Copek RA, Chan KT, Haddock A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: a comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. J School Psychol. (2017) 63:77–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

20. Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York, NY: Delacorte (1990).

21. Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. (2008) 31:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7

22. Quach D, Gibler RC, Mano KEJ. Does home practice compliance make a difference in the effectiveness of mindfulness interventions for adolescents? Mindfulness. (2017) 8:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0624-7

23. Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, Cortesi S, Gasser U. Teens and Technology 2013. (2013). Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/03/13/teens-and-technology-2013/

24. Blair BL, Fletcher AC. The only 13-Year-old on planet earth without a cell phone: meanings of cell phones in early adolescents' everyday lives. J Adol Res. (2011) 26:155–77. doi: 10.1177/0743558410371127

25. Lenhart A. Teens, smartphones & texting. Pew Internet Am Life Project. (2012) 21:1–34. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/03/19/teens-smartphones-texting/ (accessed October 31, 2020).

26. Lister-Landman KM, Domoff SE, Dubow EF. The role of compulsive texting in adolescents' academic functioning. Psychol Pop Media Cult. (2017) 6:311–25. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000100

27. Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol. (2010) 15:1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063

28. Heron KE, Everhart RS, McHale S, Smyth JM. Using mobile-technology-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methods with youth: a systematic review and recommendations. J Pediatr Psychol. (2017) 42:1087–107. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx078

29. Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of sweet talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med. (2006) 23:1332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x

30. Obermayer JL, Riley WT, Asif O, Jean-Mary J. College smoking-cessation using cell phone text messaging. J Am Coll Health. (2004) 53:71–8. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.2.71-78

31. Smyth JM, Heron KE. Is providing mobile interventions “just-in-time” helpful? An experimental proof of concept study of just-in-time intervention for stress management. In: Proceeedings of the IEEE Wireless Health Conference. (2016) doi: 10.1109/WH.2016.7764561

32. Sung YT, Chang KE, Liu TC. The effects of integrating mobile devices with teaching and learning on students' learning performance: a meta-analysis and research synthesis. Comput Educ. (2016) 94:252–75. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.008

33. Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Forder L, Jones F. Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. (2014) 34:118–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.001

34. Fish J, Brimson J, Lynch S. Mindfulness interventions delivered by technology without facilitator involvement: what research exists and what are the clinical outcomes? Mindfulness. (2016) 7:1011–23. doi: 10.1007/s12671-016-0548-2

35. Gluck TM, Maercker A. A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. BMC Psychiatry. (2011) 11:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-175

36. Krusche A, Cyhlarova E, King S, Williams JMG. Mindfulness online: a preliminary evaluation of the feasibility of a web-based mindfulness course and the impact on stress. BMJ Open. (2012) 2:803. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000803

37. Lim D, Condon P, DeSteno D. (2015). Mindfulness and compassion: An examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS ONE. 10:e118221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118221

38. Shore R, Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Hayward M, Ellett L. A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention on paranoia in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness. (2018) 9:294–302. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0774-2

39. Hammen C, Rudolph K, Weisz J, Rao U, Burge D. The context of depression in clinic-referred youth: neglected areas in treatment. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. (1999) 38:64–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00021

40. Blewitt P, Broderick P. Adolescent identity: peers, parents, culture and the counsellor. Counsel Human Dev. (1999) 31.

41. Broderick PC. Learning to Breathe: A Mindfulness Program for Adolescents. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger (2013).

42. Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. (1992) 111:455–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455

43. Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The information-motivation-behavioral skill model: a general social psychological approach to understanding promoting health behavior. In: Suls J, Wallston KA. editors. Social Psychological Foundation of Health and Illness. Blackwell. (2003). p. 82–106. doi: 10.1002/9780470753552.ch4

44. Sheeran P, Maki A, Montanaro E, Avishai-Yitshak A, Bryan A, Klein WM, et al. The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. (2016) 35:1178–88. doi: 10.1037/hea0000387

45. Strecher VJ, DeVellis BM, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ Q. (1986) 13:73–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108

46. Egbert N, Omosun F. (2017). Message-induced self-efficacy and its role in health behavior change. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.344

47. Creswell JD, Lindsay EK. How does mindfulness training affect health? A mindfulness stress buffering account. Curr Direc Psychol Sci. (2014) 23:401–7. doi: 10.1177/0963721414547415

48. Lucas-Thompson R, Seiter N, Broderick PC, Coatsworth JD, Henry KL, McKernan CJ, et al. Moving 2 Mindful (M2M) study protocol: testing a mindfulness group plus ecological momentary intervention to decrease stress and anxiety in adolescents from high-conflict homes with a mixed-method longitudinal design. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e030948. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030948

Keywords: adolescence, mindfulness-based interventions, ecological momentary intervention, ecological momentary assessment, home practice

Citation: Lucas-Thompson RG, Rayburn S, Seiter NS, Broderick PC, Smyth JM, Coatsworth JD and Henry KL (2020) Learning to BREATHE “Plus”: A Multi-Modal Adaptive Supplement to an Evidence-Based Mindfulness Intervention for Adolescents. Front. Public Health 8:579556. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.579556

Received: 02 July 2020; Accepted: 19 October 2020;

Published: 17 November 2020.

Edited by:

Raz Gross, Sheba Medical Center, IsraelReviewed by:

Andrew Leung Luk, Nethersole Institute of Continuing Holistic Health Education (NICHE), Hong KongMandakini Sadhir, University of Kentucky, United States

Copyright © 2020 Lucas-Thompson, Rayburn, Seiter, Broderick, Smyth, Coatsworth and Henry. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rachel G. Lucas-Thompson, bHVjYXMtdGhvbXBzb24ucmFjaGVsLmdyYWhhbUBjb2xvc3RhdGUuZWR1

Rachel G. Lucas-Thompson

Rachel G. Lucas-Thompson Stephanie Rayburn

Stephanie Rayburn Natasha S. Seiter1

Natasha S. Seiter1 Patricia C. Broderick

Patricia C. Broderick Joshua M. Smyth

Joshua M. Smyth J. Douglas Coatsworth

J. Douglas Coatsworth Kimberly L. Henry

Kimberly L. Henry