- 1Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 2Stanford Prevention Research Center, School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 3School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

College and university campuses have long been designed as embodied places of societal values and aspirations, reflecting both academic traditions and heritages alongside social and scientific change and innovation. More pragmatically, these spaces share some commonalities with other living and working environments, and must adapt to changing technological and social norms. Since the 1970's, workplace adaptations included employer-sponsored health promotion programs and facilities. While campus environments such as fitness centers and dining halls have been incorporated into health promotion initiatives, other aspects of human well-being have been neglected. In this paper, we describe an initiative, Contemplation By Design, to incorporate contemplation and mindfulness into the daily lives of all members of the Stanford University community, including students, faculty, staff, and their families, as well as alumni and retirees who live close by. This case study highlights ways that physical planning and programmatic initiatives for contemplative practices have been integrated to deliver generalizable, community-based well-being resources that can be emulated in diverse settings throughout the Stanford University campuses, including the main campus and local satellite campuses. Based on experience drawn from Contemplation By Design, practical recommendations for designing contemplative practice spaces and programs are offered.

Introduction

College and university campuses are amalgamations of built and natural environments where diverse groups of individuals live, work, learn, and play. For students, they can be both neighborhood and workplace. For employees, campuses are purpose-built workplaces that may closely resemble office, hospital, library, or dining spaces in non-academic settings. Indeed, in many communities, one or several colleges or universities can function as a primary employer, transport or housing provider, or landowner. Furthermore, many campuses engage in regular planning processes and develop land use documents akin to comprehensive plans. Scholars have also pointed to the role of American colleges and universities in the provisioning of public spaces (1–3), and as embodied places of societal values and aspirations, reflecting both academic traditions and heritages alongside social and scientific change and innovation (4). Thus, campus plans and designs often reach beyond the Ivory Tower and into surrounding neighborhoods and office parks, and, at least indirectly, follow an institution's alumni wherever they go after graduation. While the modern age of university planning is more characterized by the role of technology in the classroom, and broader questions about virtual online learning environments, the belief that good campus design can engender positive outcomes including inter- and intrapersonal personal values, emotional intelligence, and civic engagement, is resonant. Collectively, these outcomes can contribute to individual and community health and well-being.

Background: Campus and Workplace Health Promotion Initiatives

The need to address rising rates of chronic disease through health promotion and prevention in community settings, rather than medical treatment of disease states in clinics and hospitals, has been noted by US researchers and policymakers since at least the 1980's (5, 6). As a type of community setting where young adults and adults spend the majority of their waking hours, schools and workplaces provide unique opportunities for health promotion, as administrators or employers may offer programmatic and economic incentives in addition to provisioning physical spaces and facilities to support individuals engaging in healthy behaviors (7, 8). Additionally, encouraging results from health promotion interventions embedded within worksites and schools, including higher education institutions, provide a further rationale for campus administrators to consider these initiatives for their own faculty, staff, or students (9–11).

Still, there is room for improvement. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's planning document Healthy People 2010 set a target of three in four employers offering a worksite health promotion program, though a 2004 national survey of worksites found that this was only the case among 6.9% of respondents (12). The more recent Healthy People 2020 goal is for 40% of employees to have access to workplace-sponsored stress prevention or reduction programs, which would represent a six percent increase from the 2010 baseline measure (13). Overall, the trend toward workplace health promotion is positive, with some promising returns in terms of lowered medical costs and increased productivity (10), though employer adoption and rigorous evaluation have fallen short of CDC aspirations (8, 9, 14). The provisioning of physical spaces for students and employees to practice healthy behaviors has been suggested as a means of further enhancing positive outcomes, though further research is needed (11).

Campus Environments for Contemplative Practices

This case study highlights another impactful, but under-studied, element of campus design: contemplative space, or places that enable and/or encourage individuals to engage in any kind of contemplative practice. Contemplative practice (CP) is a term that encompasses a variety of behaviors that aim to quiet the striving mind, connect the individual to something larger than their own life, and sustain an experience of being seen, safe, soothed, and secure. A growing body of literature documents the social and biological benefits of contemplative practices, including stress and pain management, weight control, sustained physical activity, and promoting emotional health and overall fulfillment, purpose, and meaning (15). Contemplative practices have shown promise in reducing negative emotional behavior and increasing prosocial behaviors, thus allowing practitioners to build better social connections and feel part of something larger, purposeful, and meaningful (16).

In the clinical setting, studies have also demonstrated the benefits of contemplative practices for both patients and providers. For instance, a German study found better healing outcomes among hospital patients when their provider engaged in contemplative practices, even if the patient was unaware (17). One possible pathway between practitioners and patients may involve an enhanced sense of presence during interpersonal interactions that arises from their enhanced self-care (18, 19). Arthur Kleinman, a psychiatrist and anthropologist, describes shared presence as “an interpersonal process that mobilizes vitality from both clinician and patient, and from family caregiver and recipient of care” (20). Even outside of healthcare, there appears to be increasing interest in contemplative practices in the workplace, most notably yoga and meditation (21).

Research also demonstrates how contemplative practices can support an individual's discovery and cultivation of purpose and meaning in life, which is related to a variety of positive physical and social outcomes (22). For example, studies show that a strong sense of purpose is associated with positive health biomarkers, such as high density lipoprotein cholesterol (23–25), and behaviors, including better management of chronic conditions such as substance addiction, depression, and diabetes (26–30). More distal effects of purpose include reduced risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events (31), and lower health care costs via greater use of preventive health services and fewer nights of hospitalization (32). Especially relevant to campus design, one longitudinal cohort study of college seniors found that cultivation of purpose and skills for sustaining that cultivation throughout life was significantly associated with generativity, personal growth, and integrity later on in adulthood (33).

Some evidence exists to suggest that reliably engaging with contemplative practices helps individuals develop positive personal and interpersonal traits. For example, individuals who regularly engage in contemplative practices have been shown to score higher on scales of prosocial and interpersonal traits (34), and a more recent meditation intervention found that the cultivation of purpose through meditation was essential to the success of the treatment group, relative to the control (35). While the literature investigating contemplative practices and the development of individual and community purpose or meaning is relatively nascent (36), academic leaders have previously underscored the creative social change-making potential of contemplative practices in higher education (37).

Just as workplace and campus health promotion campaigns are evolving to accommodate contemporary issues and interests, so too must modern campuses respond and adapt to the needs and values of their students. Recent studies have suggested that millennials may be expecting to see contemplative spaces, like meditation rooms, on campus (38). Campus planners and designers may also be confronted with needs to reimagine formerly on-campus religious buildings from single-denomination places of worship to multi-faith and/or multi-purpose environments or dedicating new structures or buildings to support new kinds of secular or spiritual contemplative and/or inter-faith activities (39). Whether by building anew or by repurposing existing environments, these on campus environmental supports may help administrators respond to calls to use contemplative practices as a means of achieving university goals, including teaching and learning outcomes (40, 41) and student health and well-being, especially mental health, and emotional well-being (42, 43).

Context

Here, we offer a descriptive community case study of the multi-level, multi-year Contemplation By Design initiative at Stanford University as a model for enabling and encouraging campus staff, students, faculty, and their families to reap the benefits of contemplative practices. The case was selected based on our personal knowledge of the Contemplation By Design initiative, and we draw upon our experiences organizing and assessing its constituent programmatic elements to identify the key components (both in terms of built spaces and programs). The case study also incorporates program participation data from 2011-present to chart broader trends in interest and engagement in contemplative practices from community members, as well as historical antecedents related to the University's founding which help place modern conversations about supporting on-campus contemplative practices into a broader context. We illustrate how the initiative has encouraged campus stakeholders to leverage well-being opportunities afforded by the campus built environment (both existing and purpose-built) beyond those often implicated in traditional health promotion programs, which have tended to focus on athletic and dining-related campus environments. By describing the various program components and their interactions, we identify opportunities for other campuses to glean generalizable lessons for designing and implementing similar contemplative practice initiatives for community health promotion.

Context for Contemplative Practices at Stanford University: Past and Present

Stanford University was founded as a deliberately innovative and unconventional, secular academic institution at the turn of the twentieth Century. Despite its modern notoriety as a center of high-tech productivity and innovation, the University's founders, the philanthropists Leland and Jane Stanford, insisted that the institution also seek to cultivate a sense of spiritual and religious purpose or meaning among the student population, breaking from many of the conventional norms among higher education that emphasized science and preparation for membership in the mechanistic endeavors of the Industrial Revolution. Following her husband's death, Jane Stanford, herself a multi-denominational Christian, continued to encourage the University's physical, and programmatic efforts at providing opportunities for contemplative, spiritual and religious exploration and discovery. Amid campus designing and planning, Stanford was particularly involved in shepherding the construction of a contemplative sanctuary as the key focal point at the center of Frederick Law Olmsted's campus plan for the university (44). Notably, this positioning of the sanctuary, known as Memorial Church, was criticized as it was non-sectarian and neither connected to a particular religious denomination, nor was it entirely secular and academic (44). Nevertheless, Jane Stanford maintained that “education needs intelligent guidance if it is to serve any good purpose,” and underscored this belief in an 1899 letter to the University's first president, “I have resolved to keep the University on the highest level morally and spiritually. The latter is more deeply interesting to me from the fact that it seems to be lost sight of in a sense” (45).

Purpose-Built Contemplative Space at Stanford University

Modern changes or expansions to the campus built environment having included the deliberate provisioning of new spaces for contemplative practices, beyond the existing natural and non-denominational places of contemplation so integral to the original university plan. Recent campus projects reflect both the challenges and solutions developed by architects and planners to scale the principles of contemplative design to different site contexts.

Center for Inter-Religious Community, Learning, and Experiences (CIRCLE)

Opening in 2007, Stanford University's Center for Inter-Religious Community, Learning and Experiences (CIRCLE) was the first in a series of modern contemplative place-making efforts, and includes meeting spaces, an interfaith sanctuary, as well as office space for related student groups and administrators (46). Designed to be inclusive to all faith traditions and practices, CIRCLE is described as a “a welcoming space where religious and spiritual communities can deepen understanding of one another and find common ground together while embracing the particular aspects of their traditions and practices” (47).

University Contemplative Center

After an extensive planning and design process, Stanford University opened the Windhover Contemplative Center to the campus community in 2014, responding, in part, to calls to substantively address increasing student stress in the fast-paced context of the Digital Age (48). The Center and its grounds were deliberately planned to provide a secular, minimalist, and contemplative practice-designated space for the Stanford University community, as a compliment to existing religious and spiritual places on campus, like Memorial Church. Embedded within a grove of live oaks, the Center was carefully designed to incorporate aspects of light, shade, nature, and quiet, and is maintained as a “no-noise, no-work,” “technology-free,” space, without any available wireless internet connections. The Center also features a granite masonry labyrinth for the practice known as labyrinth-walking which facilitates spiritual centering, contemplation, and prayer, and hosts free guided meditation and mindful yoga classes that regularly fill to capacity.

Lucile Packard Children's Hospital

Recent rebuilding and modernization projects at the Children's Hospital of Stanford University have included distinct elements of “healing” design. Five gardens and 3.5 acres of green space are accessible to hospital patients, visitors, and staff, pursuant to clinical research showing that access to green space can be beneficial to patient outcomes (49), which Stanford University was early to adopt in the hospital's first iteration during the 1990's (50). Beyond its natural elements, contemplative spaces also feature prominently into the hospital's design. An outdoor labyrinth provides patients and visitors an opportunity to practice contemplation, as does a first floor sanctuary space. For healthcare providers, a staff-only garden is available as “a dedicated zone for mindfulness and stress reduction” (51).

Redwood City Campus Contemplative Space

A major campus expansion in nearby Redwood City, includes a designated contemplative space, that acknowledges the need for spaces where employees can engage in a variety of contemplative practices, particularly at a location more geographically constrained than the planned open space environment available on the main campus. The Redwood City Campus contemplative space offers both formal and informal practice periods in which instruction in meditation is offered, a group practice is held weekly and opportunities for contemplative movement and prayer or personal meditation practice are available seven days a week throughout the day. Meditation cushions are provided in a serene atmosphere with a glass wall that opens to a quiet garden, in which a portable roll-out labyrinth is available for use. Occupant feedback from Redwood City Campus staff, including perspectives on the functioning and use of the contemplative space, is being actively solicited by the university architect's office and Contemplation By Design staff in order to respond to and accommodate its effective use into the future.

Contemplation by Design: Key Programmatic Elements

In 2013, Contemplation By Design was created and launched in preparation for and coordination with the 2014 opening of the Windhover Contemplative Center (48). The initiative augments longstanding health promotion programs for faculty, staff and for students, and is a campus-wide, multidisciplinary resilience-building health and well-being program that promotes the practice of contemplative lifestyle behaviors and incorporates the AMSO (awareness, motivation, skills and opportunity) framework for effective community health promotion (52–55). Faculty, staff, students and members of the greater University community are united through the opportunities to pause from high levels of productivity and innovation to experience multi-faceted, transformational learning, and develop skills to support sustainable, whole-hearted, ethical, purposeful engagement in all areas of research, teaching, learning, and service (56).

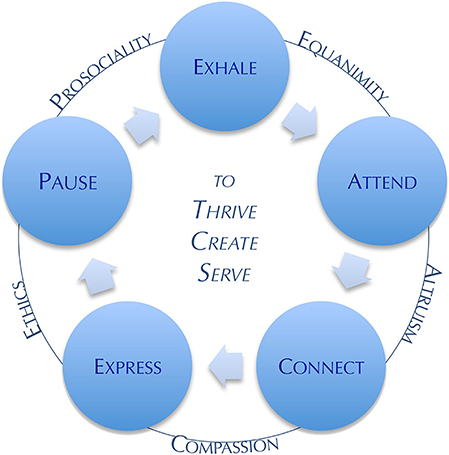

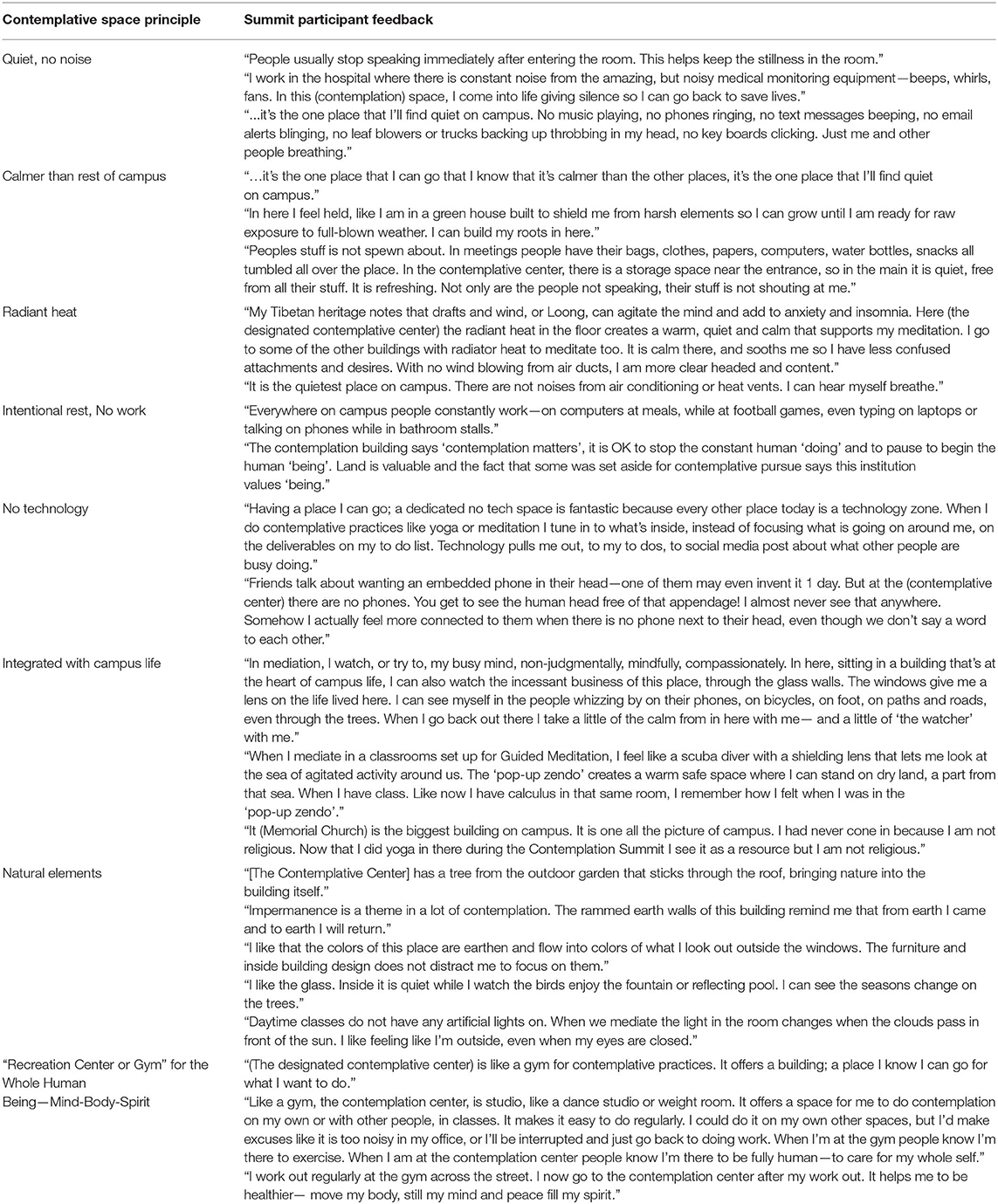

Contemplation By Design is guided by a paradigm of 10 interconnected contemplative practice constructs, the “PEACE™” paradigm (see Figure 1). Participants gain contemplative knowledge, first-hand experience, and skills to: pause the striving, driving, analytical, dualistic, and conceptualizing mind; cultivate spaciousness and possibility; sustain equanimity; and enter into compassionate relationship with themselves, others and nature; and be in a unified, interconnected oneness. They develop skills for sustaining the “power of the pause,” including deep breathing, intentional rest of the sympathetic nervous system and activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, revitalization of mind-body-spirt, and alignment between values and lifestyle habits. These skills are rooted in emerging evidence on the diverse benefits of contemplative practices, including self-awareness (57), attention regulation (58), neuroplasticity (59, 60), resilience, stress management, meaning and purpose, happiness, and compassion (58, 61–67).

Figure 1. Contemplation By Design PEACE™ Paradigm. Ten interconnected constructs of contemplative practice to cultivate both state and traits of contemplation.

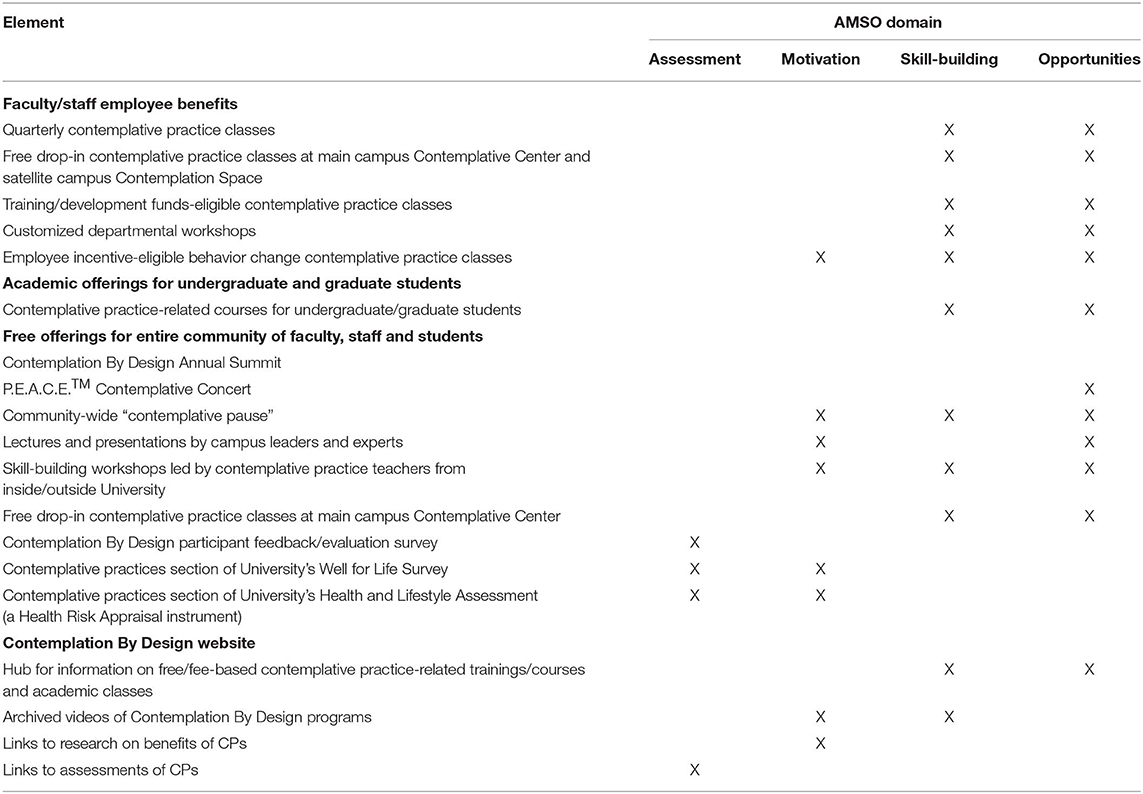

Examples of Contemplation By Design programing include: lectures on contemplative neuroscience; skill-building classes; customized departmental workshops and professional trainings on contemplative practices, resilience, meaning and purpose; an annual 10 days free Summit; contemplative concerts; a website “hub” for contemplation resources such as: research articles, free online audio and video instruction, and a calendar of campus contemplative practice groups/opportunities; as well as consistent messaging from campus leaders to increase community-wide understanding of how to incorporate contemplative practices behaviors into daily life (see Table 1). Assessment is offered to participants through online self-report surveys on health and lifestyle habits, health status and circumstances, and includes questions about contemplative practices, stress level, ability to manage stress, positive states, depression symptoms, and sleep.

The Contemplation by Design Summit

The high-profile feature of Contemplation By Design is an annual, multi- day Summit, which provides an array of opportunities for students and community members to experience and broaden their understanding of contemplative practices. Summit programming offers a variety of secular contemplative practices, as well as cultural and spiritual examples. Workshops, seminars, lectures, a large concert, and a coordinated and campus-wide “contemplative pause” are all key components of this annual Summit (see Table 1). The number of Summit programming days and opportunities have increased year-to-year, from 23 events spread over 5 days in 2014, to 111 events over 10 days in 2019. Summit enrollments have increased nearly 5-fold over the same time period (n = 1,699 in 2014, n = 8,465 in 2019), and have coincided with an increase in enrollments in contemplative practice-related workplace wellness courses for faculty and staff and contemplative practice-related academic classes for undergraduate and graduate students (see Supplemental Figure 1). This trend could also indicate how individuals who are relatively new to contemplative practices during the Summit subsequently turn to workplace wellness or academic courses for deeper, multi-week engagement in the contemplative practice topic and skill-building.

Data from annual Summit online participant surveys (distributed via email) also provide insights into how Contemplation By Design programming has engaged new audiences. Of 2018 Summit respondents (n = 391), 29% reported that they had never previously done a contemplative practice before participating in the Summit, 62% reported that they learned at least one tangible skill that they intended to do in their daily life, and 70% reported an intention to incorporate information from the Summit into their daily life. Similar patterns were also found in Summit evaluations from earlier years.

Summit survey also provide guidance for improving programming design and content. For example, Summit participants are asked: “Why have you never tried taking a contemplative pause for relaxation and self-renewal before?” Top responses in both 2014 and 2019 included not knowing how to take a contemplative pause, not knowing about health and well-being benefits associated with contemplative practices, and having other means of relaxing or taking a quiet break (see Supplemental Table 1). These data support the value of providing contemplative practice skill-building opportunities to engage new people in these lifestyle behaviors and also providing ongoing opportunities and spaces for regular contemplative practice. Open-ended responses to the Summit evaluation survey along with open-ended class feedback and reflections provide additional context for how programs influenced participant perspectives on contemplative practices. Respondents mentioned the importance of the Summit in realizing opportunities to use the “power of the pause” on campus and elsewhere, and to connect with other members of the community (see Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

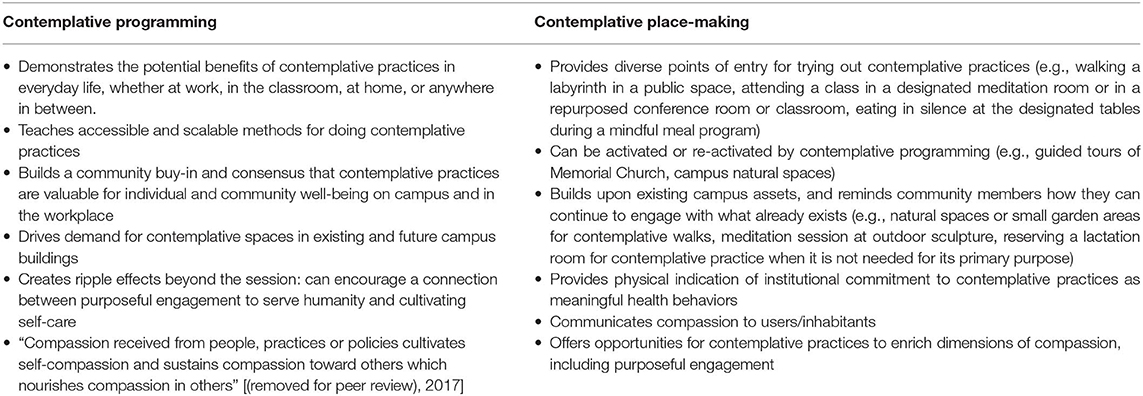

From our experience designing and implementing the Contemplation By Design initiative, several insights on creating a culture of contemplative practices on campus can be drawn for application in new settings. Here we offer some reflections on the connections between contemplative practice programming and place-making (Table 2), drawn from our experiences implementing contemplative practice programming in both purpose-built, retrofitted, and natural spaces. Based on these insights, we also suggest several specific design principles for new, retrofitted designated contemplative spaces, or repurposed spaces for temporary use for contemplative practice (Table 3), as well as reflections on the programmatic aspects of Contemplation By Design.

Table 2. Features of on-campus contemplative practice programming and place-making, based on the Stanford University experience.

Integrating Contemplative Programming With Contemplative Spaces

Glimpses of the founders' success in cultivating a sense of meaning through campus design are evident around the present-day university's use of original built spaces such as Memorial Church, as well as its open spaces which are explored as potential sites for contemplative practices as part of Contemplation By Design programming. The initiative also encourages community members to envision the use of built spaces around the campus, including, but also beyond those for religious practices (e.g., Memorial Church or CIRCLE), or even those non-religious spaces specifically designed for contemplation (e.g., Windhover Contemplative Center). Adaptive options for contemplative practices are also encouraged throughout existing campus buildings by the designation of lactation rooms as “Lactation/Wellness Rooms” wherein nursing mothers have priority, though all community members are able to use the spaces for contemplation.

By encouraging participants to consider how to practice contemplation in environments that are conducive, but not always dedicated to contemplative experiences, such as prayer, yoga, or meditation, Contemplation By Design helps participants see themselves as competent contemplative practitioners in a wide variety of settings. In annual Summit feedback, participants have also described how the combination of built environment for contemplation and programming promoted their contemplative practice as a lifestyle habit in the same way physical activity programming and gyms promote a physically active lifestyle. Common space characteristics cited as supportive to contemplative practices included quiet and calmness, radiant heating and natural elements, with clear designations of space use for rest rather than for work, no technology, and integration into broader campus life (see Table 4). Some participants made comparisons to gym facilities, indicating that contemplative spaces were needed to support overall well-being, just as recreation centers are made available for physical activities.

Table 4. Contemplation By Design participant comments on effective qualities of contemplative practices spaces.

Health promotion and disease prevention programs in other arenas have demonstrated that individuals can develop enduring lifelong health habits through structured engagement with healthy behaviors through formal means for cultivating a habit, such as physical activity class and healthy meals programs in worksites (68–70). For instance, for an individual to increase their physical activity, they may be asked to engage in immersive physical activity experiences, such as fitness classes that use specialized instruction or equipment only available at a gym; yet, a participant may also be asked to consider complimentary behavior changes, such parking further from one's destination to incur a short period of walking. Similarly, a contemplative practitioner may feel the need to immerse themselves in a meditation class at the Contemplative Center, though they could also adopt a contemplative practice as part of their daily train or bus commute to campus. Further research exploring the transportability of contemplative practice skills beyond designated contemplative spaces is warranted.

Design Principles for Contemplative Spaces

Design organizations have only begun to develop guidelines and certification systems for contemplative spaces. For example, the International WELL Building Institute has proposed a building standard that includes a “Mind” concept, which identifies factors such as altruism, healthy sleep policy, and biophilic design (71). Researchers have outlined general categories of “contemplative landscapes,” based on expert review and elicitation, which include landscape layers, landform, vegetation, light and color, compatibility, archetypal elements, and character of peace and silence (72). Still, these guidelines for mind-friendly workplaces do not completely address contemplative practices, nor do they describe the ideal form for specific, dedicated spaces for them to occur. With this in mind, further study of the influence of building and landscape architecture on contemplative practices is warranted.

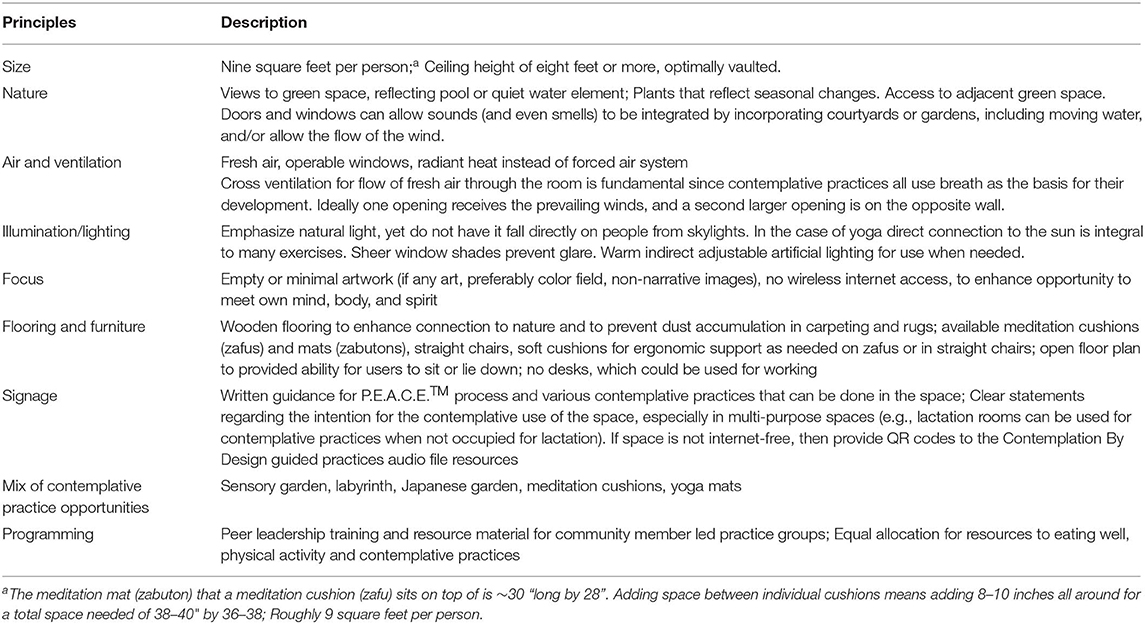

Here, we reflect on effective ways of (re)dedicating (as in the case of Memorial Church) or creating contemplative spaces (as with the Contemplative Center), and identify 10 practical principles for contemplative spaces, drawn from our experiences designing, and implementing contemplative practice programming at Stanford University (see Table 3). We believe that principles of size, ceiling height, nature, ventilation, illumination, focus, flooring and furniture, signage, mix of contemplative practice opportunities, and programming have all influenced the relative success of different contemplative spaces around the university. These principles may be adaptable to a variety of contexts, from smaller colleges and universities, to large employers in office campuses.

Contemplative Practice Programming

The AMSO model for community health promotion suggests an optimal programmatic framework that reflects the relative influence of constructs to achieving health behavior change: 5% awareness, 30% motivation, 25% skills, and 40% opportunity (52, 53). Survey data from Contemplation By Design show how in 2014, 50% of respondents reported that the primary benefit of the initiative was the provisioning of opportunities to engage in contemplative practice (see Supplemental Table 3). This figure declined over subsequent years (to 28% in 2018), perhaps suggesting that once opportunities were built, literally in this case in terms of providing several new designated spaces and a reliable schedule of space repurposed for contemplative practices, along with programming offering a variety of high-quality contemplative practices skill-building classes, perceived benefits of participation shifted to other domains. Further research and program evaluation is needed to illuminate the most effective mix of programming for promoting contemplative practice behaviors. By offering multiple doorways, for literal and figurative entry, into the benefits of contemplative practices health promotion programs can effectively provide opportunities that appeal to a wide range of people's existing interests and life goals.

To date, much of the contemplative programming has focused on neuroscience, emotional health and well-being, or spiritual seeking. Contemplative practices also are keenly relevant to facilitating integrative learning, sustainable careers in public service, acts of social justice and democratic values. By thinking broadly about contemplative practice programming and places to nourish contemplative skills, public health policy and initiatives can utilize variety of existing spaces to facilitate experience of contemplation as something that is adaptable and transportable, and can simultaneously promote the health of others, as well as oneself.

Limitations

While we have attempted to identify relatively unique features of the case context that might limit the generalizability of themes identified to other settings, it is possible that other unidentified factors have influenced the success of Contemplation By Design initiatives. Further research of similar programs in other contexts could help test or validate the robustness of the suggestions we have made. Additionally, new analyses of individual-level participant data could start to unpack specific programs, activities, or spaces that were particularly effective in supporting learning and behavior, with special attention to possibly influential participant characteristics (e.g., age, employee/student status, prior experience with contemplative practices, etc.). By providing a descriptive overview of the quantitative and qualitative insights gleaned from program assessments, we hope to have provided a general framework for others to design similar or improved evaluation opportunities.

Conclusion

In this period of internationally and historically high rates of chronic disease, especially stress-related disease, we also see increasing (or, perhaps, re-emerging) interest in contemplative practices such as meditation and yoga. The field of health promotion is ripe to integrate contemplative practice into community-based program design as society responds to mounting stressors and dissonance, and grows toward what nourishes it, including secular opportunities for contemplative practice and self-care (21). Campus designers and planners can respond to these forces by facilitating an ecology of designated or repurposed contemplative space, recognizing the value of these places to help individuals develop contemplative skills for effective stress management and enhanced capacity to constructively engage with the complexity of the modern life and world issues that increasingly impact all of us each day. Contemplative practices and spaces offer an important cost effective addition to public health policy, programing, and as a tangible resource essential to an environment designed to promote health and well-being.

As has been demonstrated in other lifestyle behaviors, significant advantages for human health can be made by leveraging what is known about effective health promotion and architectural and urban design. Adding contemplative practice behaviors to this mission has great potential to promote broad well-being, both at the individual and societal level, and research shows that contemplative practices both directly and indirectly contribute to enhanced health and well-being (73). Stanford University has leveraged both programmatic and environmental resources to provide its students, faculty, staff and community members with deep and broad opportunities to engage with contemplative practices. While some university initiatives, such as the construction of Windhover Contemplative Center, are not readily replicable elsewhere, we offer adaptable principles that may be applied in a variety of campus and “campus-like” environments. Overall, our experience suggests that contemplative places and programming can contribute to a community-wide cultural shift toward recognizing the “Power of the Pause.”

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

BC and TR contributed to the conceptualization of the paper. BC prepared the manuscript for publication. TR provided detailed comments and feedback.

Funding

This case study was supported by the Contemplation By Design program at Stanford University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00031/full#supplementary-material

Figure S1. Increases in Contemplation-Related Programming Enrollment at Stanford, 2011-2018. Note: Contemplative Practice-Related Healthy Living Course enrollment is limited to Stanford faculty and staff; Contemplation By Design Summit enrollment is open to faculty, staff, students, and community members.

References

1. Griffith JC. Open space preservation: an imperative for quality campus environments. J High Educ. (1994) 65:645–69. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1994.11774745

2. Gumprecht B. The campus as a public space in the American college town. J Hist Geogr. (2007) 33:72–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jhg.2005.12.001

4. Turner PV. Campus: An American Planning Tradition. 1st ed. New York, NY; Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press (1987).

5. Cohen WS. Health promotion in the workplace: a prescription for good health. Am Psychol. (1985) 40:213–6. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.40.2.213

6. Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion as a public health strategy for the 1990's. Annu Rev Public Health. (1990) 11:319–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.11.050190.001535

7. Fish C. Health promotion needs of students in a college environment. Public Health Nurs. (1996) 13:104–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00227.x

8. Sparling PB. Worksite health promotion: principles, resources, and challenges. Prev Chronic Dis. (2009) 7:A25.

9. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services (2018).

10. Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z. Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff. (2010) 29:304–11. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

11. Plotnikoff RC, Costigan SA, Williams RL, Hutchesson MJ, Kennedy SG, Robards SL, et al. Effectiveness of interventions targeting physical activity, nutrition and healthy weight for university and college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2015) 12:45. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0203-7

12. Linnan L, Bowling M, Childress J, Lindsay G, Blakey C, Pronk S, et al. Results of the 2004 National Worksite Health Promotion Survey. Am J Public Health. (2008) 98:1503–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100313

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Chart | Healthy People 2020. Healthy People 2020. (2019) Available online at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data/Chart/5051?category=1&by=Total&fips=-1 (accessed June 5, 2019).

14. Goetzel RZ, Henke RM, Tabrizi M, Pelletier KR, Loeppke R, Ballard DW, et al. Do workplace health promotion (wellness) programs work? J Occup Environ Med. (2014) 56:927. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000276

15. Olano HA, Kachan D, Tannenbaum SL, Mehta A, Annane D, Lee DJ. Engagement in mindfulness practices by U.S. adults: sociodemographic barriers. J Altern Complement Med. (2015) 21:100–2. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0269

16. Kemeny ME, Foltz C, Cavanagh JF, Cullen M, Giese-Davis J, Jennings P, et al. Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional behavior and promotes prosocial responses. Emot Wash DC. (2012) 12:338–50. doi: 10.1037/a0026118

17. Grepmair L, Mitterlehner F, Loew T, Bachler E, Rother W, Nickel M. Promoting mindfulness in psychotherapists in training influences the treatment results of their patients: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Psychother Psychosom. (2007) 76:332–8. doi: 10.1159/000107560

18. Fortney L, Taylor M. Meditation in medical practice: a review of the evidence and practice. Prim Care Clin Off Pract. (2010) 37:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.004

19. Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. (2009) 302:1284–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384

21. Kachan D, Olano H, Tannenbaum SL, Annane DW, Mehta A, Arheart KL, et al. Prevalence of mindfulness practices in the US workforce: National Health Interview Survey. Prev Chronic Dis. (2017) 14:e01. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160034

22. Czekierda K, Banik A, Park CL, Luszczynska A. Meaning in life and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. (2017) 11:387–418. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2017.1327325

23. Bower JE, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Fahey JL. Finding positive meaning and its association with natural killer cell cytotoxicity among participants in a bereavement-related disclosure intervention. Ann Behav Med. (2003) 25:146–55. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2502_11

24. Fredrickson BL, Grewen KM, Coffey KA, Algoe SB, Firestine AM, Arevalo JMG, et al. A functional genomic perspective on human well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:13684–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305419110

25. Ryff CD, Singer BH, Dienberg Love G. Positive health: connecting well-being with biology. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. (2004) 359:1383–94. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1521

26. Kim ES, Hershner SD, Strecher VJ. Purpose in life and incidence of sleep disturbances. J Behav Med. (2015) 38:590–7. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9635-4

27. Kim ES, Kawachi I, Chen Y, Kubzansky LD. Association between purpose in life and objective measures of physical function in older adults. JAMA Psychiatry. (2017) 74:1039–45. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2145

28. Martin RA, MacKinnon S, Johnson J, Rohsenow DJ. Purpose in life predicts treatment outcome among adult cocaine abusers in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. (2011) 40:183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.10.002

29. Rasmussen NH, Smith SA, Maxson JA, Bernard ME, Cha SS, Agerter DC, et al. Association of HbA1c with emotion regulation, intolerance of uncertainty, and purpose in life in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prim Care Diabetes. (2013) 7:213–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2013.04.006

30. Robak RW, Griffin PW. Purpose in life: what is its relationship to happiness, depression, and grieving? North Am J Psychol. (2000) 2:113–9.

31. Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. (2016) 78:122. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274

32. Kim ES, Strecher VJ, Ryff CD. Purpose in life and use of preventive health care services. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:16331–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414826111

33. Hill PL, Burrow AL, Brandenberger JW, Lapsley DK, Quaranto JC. Collegiate purpose orientations and well-being in early and middle adulthood. J Appl Dev Psychol. (2010) 31:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.12.001

34. Haimerl CJ, Valentine ER. The effect of contemplative practice of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal dimensions of the self-concept. J Transpers Psychol. (2001) 33:37–52.

35. Jacobs TL, Epel ES, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Wolkowitz OM, Bridwell DA, et al. Intensive meditation training, immune cell telomerase activity, and psychological mediators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2011) 36:664–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.09.010

36. Strecher VJ. Life on Purpose: How Living for What Matters Most Changes Everything. San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins (2016).

37. Rockefeller SC. Meditation, social change, and undergraduate education. Teach Coll Rec. (2006) 108:1775–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00761.x

38. Rickes P. Make way for millennials! Plan High Educ. (2011) 39:61–71. doi: 10.1109/EMR.2011.5876177

39. Johnson K, Laurence P. Multi-faith religious spaces on College and University Campuses. Relig Educ. (2012) 39:48–63. doi: 10.1080/15507394.2012.648579

40. Bright J, Pokorny H. Contemplative practices in higher education: breathing heart and mindfulness into the staff and student experience. HERDSA News. (2013) 35:9–12.

41. Christian C. Contemplative practices and mindfulness in the interior design studio classroom. J Inter Des. (2019) 44:29–43. doi: 10.1111/joid.12134

42. Golden L, Levin L, Mizrahi R, Biebel K. College to Career: Supporting Mental Health. Shrewsbury, MA: University of Massachusetts Medical School. Available online at: https://www.umassmed.edu/globalassets/transitionsrtc/about-us/news-and-events/college-to-career-supporting-mental-health-jed-umass-whitepaper-final-v2.pdf (accessed February 14, 2020).

43. Turnage C. In Higher Ed's Mental-Health Crisis, an Overlooked Population: International Students. Chron High Educ Wash. (2017) Available online at: https://search.proquest.com/docview/1945187650/abstract/76F4B42D291C4BFEPQ/1 (accessed January 29, 2019).

44. Coulson J, Roberts P, Taylor I, Roberts P, Taylor I. University Planning and Architecture?: The search for perfection. London: Routledge (2015). doi: 10.4324/9781315750774

45. Nagel GW, Stanford JL. Jane Stanford, Her Life, and Letters. Stanford: Stanford Alumni Association (1975). Available online at: http://archive.org/details/janestanfordherl00nage (accessed September 18, 2018).

46. Sveinsson C. Religious Spaces Provide Sanctuary for Students. The Stanford Daily (2014) Available online at: https://www.stanforddaily.com/2014/01/31/religious-spaces-provide-sanctuary-for-students/ (accessed September 28, 2018).

47. Karlin-Neumann P, Sanders J. Bringing faith to campus: religious and spiritual space, time, and practice at Stanford University. J Coll Character. (2013) 14:125–132. doi: 10.1515/jcc-2013-0017

48. Xu V. Windhover Contemplative Center to Finish by Early Summer. The Stanford Daily (2014) Available online at: https://www.stanforddaily.com/2014/05/08/windhover-contemplative-center-to-finish-by-early-summer/ (accessed September 28, 2018).

49. Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. (1984) 224:420–1. doi: 10.1126/science.6143402

50. DeTrempe K. Family, Nature Key to Healing at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford. Stanford Medicine (2017) Available online at: http://stanmed.stanford.edu/2017fall/packard-childrens-hospital-values-healing-environment.html (accessed September 28, 2018).

51. Healing Gardens and Outdoor Spaces. Stanford Children Health (2018). Available online at: https://newhospital.stanfordchildrens.org/our-services/healing-gardens/ (accessed September 28, 2018).

52. O'Donnell MP, Ainsworth TH. Health Promotion in the Workplace. New York, NY: Wiley (1984). Available online at: https://oxford.worldcat.org/search?q=isbn%3A9780471098508 (accessed January 18, 2020).

53. O'Donnell MP. A simple framework to describe what works best: improving awareness, enhancing motivation, building skills, and providing opportunity. Am J Health Promot. (2005) 20:1–11. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-20.1.TAHP-1

54. Bourdillon A. Contemplation by Design Week Begins Nov. 3, Emphasizing Calm, Meditation. Stanford Daily (2014) Available online at: https://www.stanforddaily.com/2014/10/27/contemplation-by-design-week-begins-nov-7-emphasizing-calm-meditation/ (accessed June 4, 2019).

55. Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. (1996) 10:282–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282

56. Sullivan KJ. Stanford Community to Enjoy the “Power of the Pause.” Stanford News (2018). Available online at: https://news.stanford.edu/2018/10/26/stanford-encourages-campus-community-enjoy-power-pause/ (accessed January 18, 2020).

57. Farb NA, Segal ZV, Mayberg H, Bean J, McKeon D, Fatima Z, et al. Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. (2007) 2:313–22. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm030

58. Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ. Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci. (2008) 12:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005

59. Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Dixon ML, Floman JL, Ellamil M, Rumak SP, et al. Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2014) 43:48–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016

60. Treadway MT, Lazar SW. Meditation and neuroplasticity: using mindfulness to change the brain. In: Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance Processes in Clients: Illuminating the Theory and Practice of Change. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications (2010). p. 185–206.

61. Eisendrath SJ (ed). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy: Innovative Applications. Switzerland: Springer (2016).

62. Farb NA, Anderson AK, Segal ZV. The mindful brain and emotion regulation in mood disorders. Can J Psychiatry. (2012) 57:70–7. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700203

63. Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol. (2013) 69:28–44. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21923

64. Neff KD, Kirkpatrick KL, Rude SS. Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. J Res Personal. (2007) 41:139–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

65. Neff KD, Pommier E. The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self Identity. (2013) 12:160–76. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2011.649546

66. Salzberg S. Real Happiness: The Power of Meditation: A 28-Day Program. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company (2010).

67. Simkin DR, Black NB. Meditation and mindfulness in clinical practice. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin. (2014) 23:487–534. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.03.002

68. Ni Mhurchu C, Aston LM, Jebb SA. Effects of worksite health promotion interventions on employee diets: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2010) 10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-62

69. Malik SH, Blake H, Suggs LS. A systematic review of workplace health promotion interventions for increasing physical activity. Br J Health Psychol. (2014) 19:149–80. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12052

70. Engbers LH, van Poppel MNM, Chin A, Paw MJM, van Mechelen W. Worksite health promotion programs with environmental changes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. (2005) 29:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.03.001

71. Mind | WELL Standard. Available online at: https://standard.wellcertified.com/mind?_ga=2.80174037.357493808.1538193137-1230548370.1538193137 (accessed September 29, 2018).

72. Olszewska AA, Marques PF, Ryan RL, Barbosa F. What makes a landscape contemplative? Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci. (2018) 45:7–25. doi: 10.1177/0265813516660716

Keywords: contemplative practices, mindfulness, health promotion, workplace, higher education, colleges and universities, campus planning and design, case study

Citation: Chrisinger BW and Rich T (2020) Contemplation by Design: Leveraging the “Power of the Pause” on a Large University Campus Through Built and Social Environments. Front. Public Health 8:31. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00031

Received: 08 November 2019; Accepted: 03 February 2020;

Published: 28 February 2020.

Edited by:

Rosemary M. Caron, University of New Hampshire, United StatesReviewed by:

Todd Allen Telemeco, University of North Carolina at Pembroke, United StatesKrista Mincey, Xavier University of Louisiana, United States

Copyright © 2020 Chrisinger and Rich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Benjamin W. Chrisinger, YmVuamFtaW4uY2hyaXNpbmdlckBzcGkub3guYWMudWs=

Benjamin W. Chrisinger

Benjamin W. Chrisinger Tia Rich

Tia Rich