- 1Center for Rehabilitation Medicine, University Clinical Center Kragujevac, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 2Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 3National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russia

- 4Department of Public Health and Healthcare, First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

- 5Department of Dentistry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

- 6Department of Human Pathology, First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

- 7Department of Global Health Economics and Policy, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Serbia

Serbia is an upper-middle income Eastern European economy. It has inherited system of health provision and financing, which is a mixture of Soviet Semashko and German Bismarck models. So far, literature evidence on long-term trends in health spending remains scarce on this region. Observational descriptive approach was utilized relying on nationwide aggregate data reported by the Republic Health Insurance Fund (RHIF) and the Government of Serbia to the WHO office. Consecutively, the WHO Global Health Expenditure Database1 was used. Long-term trends were extrapolated on existing data and underlying differences were analyzed and explained. The insight was provided across two distinctively different periods within 2000–2016. The first period lasted from 2000 till 2008 (the beginning of global recession triggered by Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy). This was a period of strong upward growth in ability to invest in health care. Spending grew significantly in terms of GDP share, national and per capita reported expenditures. During the second period (2009–2016), after the beginning of worldwide economic crisis, Serbia was affected in a way that its health expenditure growth in PPP terms slowed down effectively fluctuating around plateau values from 2014 to 2016. Serbia health spending showed promising signs of steady growth in its ability to invest in health care. Consolidation marked most of the past decade with certain growth rates in recent years (2017–2019), which were not captured in these official records. The future national strategy should be devised to take into account accelerated population aging as major driver of health spending.

Introduction

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century macroeconomic and political reforms, alongside with economy strengthening, led to rapid growth of health spending in Serbia (1). This trend has reached essentially a plateau level since the beginning of the global macroeconomic recession, recording fluctuations in 2008–2016 (2). These developments were led by several core-unfolding events across the nation. One of them was transformation of local pharmaceutical sector from domestic manufactured, generics-dominated one, toward imported brand-name and high-budget impact innovative medicines (3, 4). Acceleration of late stage population aging (5) was another far-reaching evolution with profound long-term impact on health financing sustainability, just like elsewhere throughout the Balkans (6), Eastern Europe (7, 8), and Asia (9, 10). Among other demand-side issues, sharply increased citizen welfare, purchasing power and living standards since the 1990s ultimately led to the increased civil expectations toward affordability of cutting-edge technologies (11). This fact has added pressure to the authorities to provide for their reimbursement in resource-constrained setting (12).

Last, but not least, epidemiologic transition of morbidity and mortality patterns taking place and accelerating since the post-WWII decades, brought upon blossoming of non-communicable diseases (13). Unlike mostly acute and today curable infectious diseases of the past (14), these were chronic, life-time expensive disorders (15). In the case of cancer (16), they have created so-called “the last year of life phenomenon” (17). This meant that the last 9 or 12 months of suffering and palliative care requiring expensive intensive care admissions (18) or oncology treatments (19), frequently equal the entire lifespan consumption of a citizen (20).

All these changes dictated the strong strive for health system reorganization (21) and advancement in terms of greater cost-effectiveness of resource allocation policies (22) and need for improved outcomes (23). Probably the most convincing success stories on adaptive responses to population aging challenge come from the similarly shaped post-communist health care sectors of some of the leading BRICS nations (BRICS is the acronym coined for an association of five major emerging national economics: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) (24–27).

The three leading early historical establishments of health care financing and provision models in Europe, later to be embraced by their peripheral descendant cultures, were the German Bismarck model (1883), the British Beveridge (28) model (adopted in 1911) and the Soviet-Russian Semashko (29), established in the early 1930s (30). The Semashko model, actually pioneered universal right to health care free of charge worldwide (31). It was made possible, being a part of system of a centrally-planned economy with domination of specialized institutions (32). The Bismarck model is a market-oriented model with decentralization (contract model), where primary health care acts as a gatekeeper to the system (33). This model features effect-based payments, evidence-based medicine and the capacity (excessive) is visibly reduced (34).

In the Republic of Serbia, public government-led and health insurance fund RFZO-led spending, remains by far more relevant in comparison to private provisions for health care (35). The Law on Health Insurance of the Republic of Serbia administers compulsory and voluntary health insurance (36). The RHIF is responsible for providing and managing compulsory health insurance, while voluntary insurance can be provided by private insurance. However, just like elsewhere throughout Central and Eastern European post-Semashko health systems, it remains scarce and marginal contributor to the universal coverage of these markets (37–39).

The aim of this paper is to analyze the dynamics of health care financing and spending in Serbia in the twenty-first century. For this purpose, national and international databases were employed. The novelty of this study, compared to, e.g., (40) consists in shedding light on the healthcare financing in Serbia. Following this introduction, the overview of the country background and current Serbian national healthcare system are presented. Next, data and method are introduced. After this, the results are presented. Discussion precedes the concluding section.

Healthcare Financing in Serbia

In Serbia, all the money directly or indirectly is provided by the citizens through financing the state budget, compulsory health insurance, direct payment “out-of-pocket,” financing from the community funds, donations, loans, etc. (21) The health care system in Serbia is funded through a combination of public finances and private contributions (41). The most important source of health care financing is the National Health Insurance Fund of the Republic of Serbia (42). Health Insurance Fund is financed also with supplementary financing from various budgetary sources, such as the Pension Fund, the Ministry of Finance Fund for Unemployed, etc. Funds for the health care of the insured persons are provided from the RHIF (40).

Due to the essential absence of private health care insurance (43), private funding is more or less completely based on out-of-pocket payments (44). It is supplemented by contributions from a small number of major companies, which have (and fund) their own institutions, specializing in the treatment of occupational diseases and provide primary care services (45). More than 90% of public costs are financed through the RHIF. In Serbia, about 69% of total current health expenditure (TCHE) are financed by public sources, thereof, the largest share by RHIF2.

An employee is granted a health insurance, which depends on employment status (temporary or permanent employment). Health insurance for retired persons is based on their paid contributions during the working life (46). The employer is obliged to pay contributions to the RHIFon a regular basis, and a health insurance notice with prolonged validity will be provided to the insured person (23). Unemployed persons have to possess mandatory employment notice with employment record. In addition, a citizen has to register at the National Employment Service based on somebody's place of residence (47). Lastly, applying for health insurance at branch offices of the RHIF, according to the place of residence, is required. Health insurance is without any payment due for unemployed persons registered at the National Employment Service (48).

Variety of countries worldwide, rich and poor alike, have historically experienced obstacles when it comes to ensuring adequate access and equity of medical care. Universal health coverage means that such care has to be accessible to the majority of citizens regardless of their income level, within the range of accessible assets (49). It was an additional challenge to ensure affordability of cutting-edge innovative medical technologies and evidence-based medicine (50). Serbia, being the historical core of the former Yugoslavia and the oldest constitutional monarchy of the Balkans, has centuries long statehood tradition (51). This has positively reflected in its evolving legislative framework in health care and successful overcoming of many hurdles since the 1990s (18).

Current Serbia's National Health Sector Challenges

Upper-middle income Serbia shares core contemporary challenges within the WHO European Region consisting of 53 countries (52). Population aging, global macroeconomic recession as of 2008–2016, Middle Eastern (53) migration routes (54) and fiscal sustainability issues (55) are common to Eastern Europe (56) and Western EU15 nations (57).

The major factor in health deprivation is the Third Demographic Transition also known as population aging. This became global phenomenon in the second half of the twentieth century, named “The Silver Tsunami.” Based on the last 2011 Census, and according to all the characteristics of population aging, Serbian population can be classified in the group of very old populations, not only in Europe, but also globally (58). At the same time, the changes achieved in the last decades, especially by the end of the twentieth and the early twenty-first century, indicate that Serbia has been exposed to a very intense population aging. This process has been manifested in low and steadily declining share of the youth and high and continuously increasing share of the elderly in the total population of the country (59).

In Serbia, the 2011 Census registered 1,025 thousand of people under the age of 15. At the same time, there were 1,250 thousand of the elderly. This means that the number of the elderly, as in the previous 2002 Census, exceeded the number of young people. In <10 years, the number of young people decreased by 150 thousand, whereas the number of the elderly increased by 10 thousand people. The share of young people decreased from 15.8 to 14.3%, while the share of the elderly increased from 16.7 to 17.4%.

Data and Method

This brief research report article represents the descriptive data analysis of macroeconomic and health expenditure indicators in Serbia in 2000–2016. The WHO Global Health Expenditure Database was selected as a core data source among the Serbian National sources, EuroStat, OECD Health, World Bank Health Data and others. It was employed due to its internationally comparable fiscal flows tracking across jurisdictions and countries due to the National Health Accounts system adoption by the UN agencies inclusive of the WHO3, back in 1995 and its consecutive revisions in 2000 and 2011. Core indicators of income and spending observed were: current health care expenditure expressed as a percentage of GDP and per capita in nominal US dollars and in purchase power parity (PPP), domestic general government health expenditure per capita in nominal US dollars and in PPP, domestic private expenditure per capita in nominal US dollars and in PPP, as well as out-of-pocket expenditure expressed in nominal US dollars and PPP, as collected by the WHO from national governments. Financial parameters are expressed in US currency, nominal, and PPP US dollars, for easier comparability with the majority of published literature sources.

Results

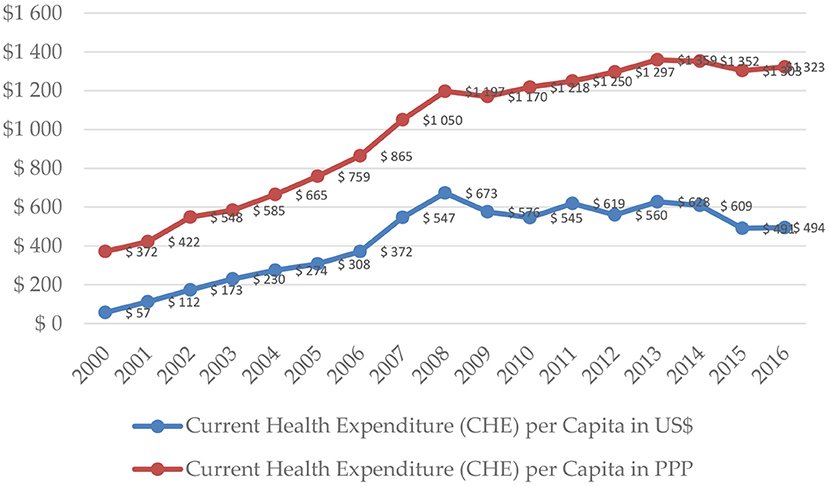

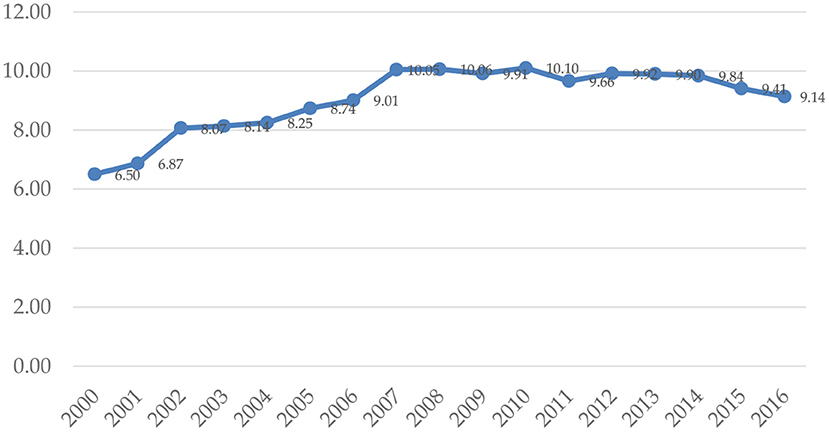

Expenditure for health care in USD per capita terms grew and later fluctuated in the period 2000–2016 in their absolute nominal and PPP amounts (Figure 1). In nominal and PPP dollar terms alike, health care expenditure rose, along with the stable share in GDP, after an increase in 2007. Nevertheless, in 2009, due to a slower growth of health care expenditure and negative growth of GDP, the total health care expenditure per capita in nominal dollar terms was inferior to the respective figure from the year before. In 2007, the share of total health care expenditure in GDP terms increased by one percentage point and stabilized in the following years at solid 10%, with a slight increase to 10.1% in 2010 (Figure 2). However, in the recent years, data indicates that there was a considerate decrease to 9.41% in 2015. The share of health care public expenditure in GDP was 9.14% in 2016 with a similar changing pace in the examined period.

Figure 1. Current health care expenditure per capita in Serbia in 2000–2016. Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.

Figure 2. Current health expenditure as a percentage of GDP in Serbia in 2000–2016. Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.

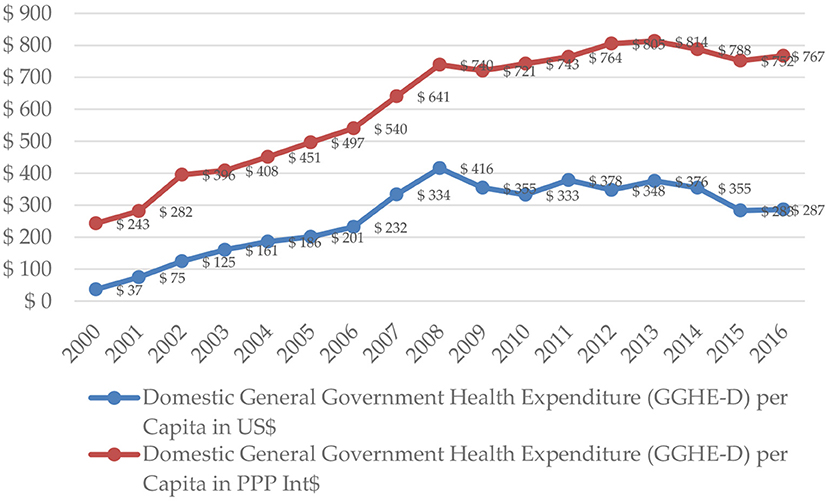

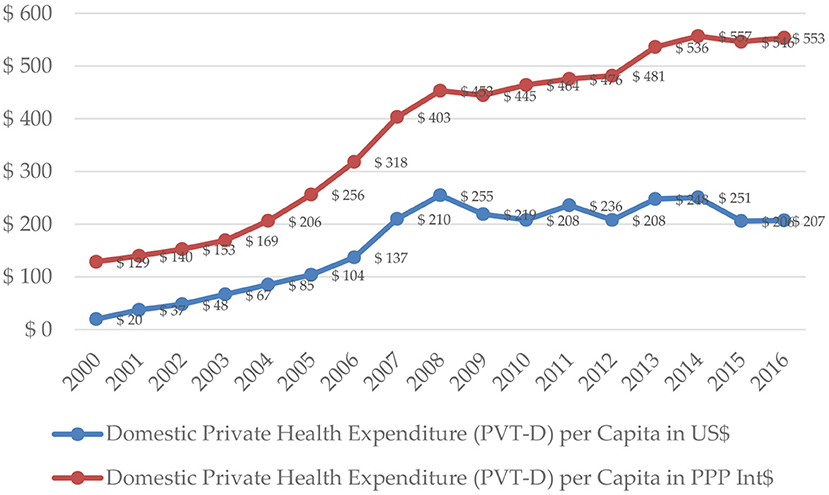

In 2010, the total health care expenditure in Serbia stabilized at the level of $545 ($1,218 PPP) per capita. During the next 3 years (2011-2013), level of total health expenditure improved to $628 ($1,359 PPP) in 2013. During the last years, there was a significant contraction to $494 ($1,323 PPP) in 2016. In 2016, the expenditure, incurred by the Domestic General Government Fund, was $287 ($767 PPP) per capita (Figure 3), while the domestic private expenditure for health care was equivalent to $207 ($553 PPP) per capita (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Domestic general government health expenditure per capita in Serbia in 2000–2016. Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.

Figure 4. Domestic private expenditure per capita in Serbia in 2000–2016. Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure Database.

When it comes to allocations for health care expressed as percentage of GDP, Serbia is slightly above the average of the European Union, with its 9.03%, i.e., approximately at the level of Belgium, Austria, Greece, and Bosnia and Herzegovina (60). In comparison to the EU countries, some non-EU countries and the average spending in the EU countries, the Republic of Serbia allocates rather modest absolute amount of funds for health care (61).

Predictably, out-of-pocket expenditure per capita almost replicate the trends demonstrated by the domestic private expenditure for health care, both in nominal and PPP dollar terms.

Plausible Causes and Recommended Policies

Health reform in Serbia started in 2003 and still is undergoing. This reform should focus on bringing health system to the optimal functionality, so it can deliver the highest positive effect on health status of the population, equity in using and financing the health care system and constant improvement in financial sustainability of the system (62, 63).

The government should accept that one of the core axioms of a country's stable development must be health of the nation (64). Poor health is in direct correlation with economic productivity (65) and development (66). Other notable factor that should be brought into focus is decentralization. The core functionality of the health care system is to be transferred while primary health care remains a top priority (67). The additional funding allocations from local level to the second administrative subdivisions of Serbia or municipalities should be mobilized (68). It appears that health system would benefit from limiting influence of frequent governments' (69) and political changes (70). Besides, municipalities and health administrative regions could share the financial risks more equally (71).

Modernizing health information system since reliability and timely information are mandatory for the health care system reform (72), represents the solid base on which planning, decision-making, managing, monitoring and implementation of reforms can be done (1). Invention of the information-communication system serving for managing the health care system (73) and gathering of all information system networks established by health institutions (74), insurance funds and regional centers (75) would tremendously aid in all of the mentioned key factors to health care system reform (76–78).

Discussion

Since the end of the Cold War Era, Serbia has suffered the painful political and economic transformation from a centrally-planned socialist economy to a free market-driven capitalist one. It has entered the so-called “transitional period” with a decade-long delay due to the civil wars of the former Yugoslavia, the consecutive sanctions and poverty, while Serbs were a major refugee ethnicity in Europe (79–81). Economic recovery allowing for increased investment in health care and social policies took place effectively since 2000, which is exactly the period of this research (82).

Degree of socio-economic development, efficiency of fund raising and priority agenda of health care among policy-makers, are some of the core drivers of local financial sustainability. Existing resources could be re-allocated in a way that will improve medical services delivery and provision. Classical inefficiencies, such as lengthy hospital admissions (83), long waiting lists for the major surgeries or invasive radiology interventions, drug shortages (84) or unaffordability of cost-effective targeted medicines (12), might become a matter of the past to a large degree. So far negotiated prices for curative technologies and preventive measures with the major industry suppliers and large hospitals, are surpassing the available Republican Health Insurance Fund's budget, creating annual net losses.

Essentially, all of the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century European health systems were built on a demographic growth model (85) with epidemiology burden of that time (86) being dominated by infectious diseases, traumatism, neonatal, and maternal mortality (87). Today, in 2019, given the radically different circumstances in European continent, it is obvious that they should all have to be changed from the very basement to the very top of its hierarchy. Given the disposable real GDP of Serbia and its share allocated to health care, authorities, and public opinion become aware of necessity for profound and long-term change.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://apps.who.int/nha/database, https://www.who.int/health-accounts/en/.

Author Contributions

MJ, VR, EA, and SB: conceptualization. MJ and VR: methodology and resources. VR, YT, and MJ: validation. KK, KJ, and EA: formal analysis, investigation, and data curation. MJ, KK, and KJ: writing—original draft preparation. YT and GR: writing—review and editing and visualization. MJ: supervision and project administration.

Funding

This research received funding through Grant OI 175 014 of the Ministry of Education Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^WHO Global Health Expenditure Database. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/nha/database

2. ^The National Health Insurance Fund of the Republic of Serbia. Available online at: https://www.eng.rfzo.rs/index.php/aboutus

3. ^WHO National Health Accounts. Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-accounts/en/

References

1. Nelson BD, Simic S, Beste L, Vukovic D, Bjegovic V, VanRooyen MJ. Multimodal assessment of the primary healthcare system of Serbia: a model for evaluating post-conflict health systems. Prehospit Disaster Med. (2003) 18:6–13. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00000613

2. Dagovic A, Zugic A, Jakovljevic MB. Macroeconomic policy impact on oncology-related public expenditure in an emerging European market – signs of early recovery. Serbian J Exp Clin Res. (2015) 16:43–50. doi: 10.1515/sjecr-2015-0007

3. Jakovljevic MB, Djordjevic N, Jurisevic M, Jankovic S. Evolution of the Serbian pharmaceutical market alongside socioeconomic transition. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. (2015) 15:521–30. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1003044

4. Jakovljevic MB. Oncology monoclonal antibodies expenditure trends and reimbursement projections in the emerging Balkan market. Farmeconomia Health Econ Ther Pathways. (2014) 15:27–32. doi: 10.7175/fe.v15i1.909

5. Jakovljevic M. Population ageing alongside health care spending growth. Srpski Arhiv. (2017) 145:534–9. doi: 10.2298/SARH160906113J

6. Jakovljevic M, Laaser U. Population aging from 1950 to 2010 in seventeen transitional countries in the wider region of South Eastern Europe. SEEJPH. (2015) 3:1–12. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/SEEJPH-2015-49

7. Jakovljevic M, Vukovic M, Fontanesi J. Life expectancy and health expenditure evolution in Eastern Europe – DiD and DEA analysis. Expert Rev Pharmacoeco Outcomes Res. (2016) 16:537–46. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1125293

8. Jakovljevic M. The aging of Europe. The unexplored potential. Farmeconomia Health Econ Therapeut. Pathways. (2015) 16:89–92. doi: 10.7175/fe.v16i4.1220

9. Rancic N, Jakovljevic MB. Long term health spending alongside population aging in N-11 emerging nations. East Eur Bus Econ J. (2016) 2:2–26.

10. Ogura S, Jakovljevic MB. Health financing constrained by population aging—An opportunity to learn from Japanese experience. Serb J Exp Clin Res. (2014) 15:175–81. doi: 10.2478/sjecr-2014-0022

11. Eaton ML, Kennedy D. Innovation in Medical Technology: Ethical Issues and Challenges. Baltimore, MD: JHU Press (2007).

12. Jakovljevic MB, Jovanovic M, Lesch OM. Accessibility and affordability of alcohol dependency medical care in Serbia. Front. Psychiatry. (2015) 5:192. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00192

13. Jakovljevic M, Jakab M, Gerdtham U, McDaid D, Ogura S, Varavikova E, et al. Comparative financing analysis and political economyof noncommunicable diseases. J Med Econ. (2019) 22:722–7. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1600523

14. Cupurdija V, Lazic Z, Petrovic M, Mojsilovic S, Cekerevac I, Rancic N, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia: economics of inpatient medical care vis-à-vis clinical severity. J Brasil Pneumol. (2015) 41:48–57. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132015000100007

15. Jakovljevic MB, Tetsuji Y, Ching CC, Stevanović DS, Jovanović MR, Nikić-Đuričić KD, et al. Cost- effectiveness of depressive episode pharmacological treatment. Hosp Pharmacol Int Multidiscipl J. (2015) 2:235–45. doi: 10.5937/hpimj1501235J

16. Jakovljevic M, Gutzwiller F, Schwenkglenks M, Milovanovic O, Rancic N, Varjacic M, et al. Costs differences among monoclonal antibodies-based first-line oncology cancer protocols for breast cancer, colorectal carcinoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J BUON. (2014) 19:1111–20.

17. Dagovic A, Walstra KM, Gutzwiller FS, Djordjevic N, Rankovic A, Djordjevic G, et al. Resource use and costs of newly diagnosed cancer initial medical care. Eur J Oncol. (2014) 19:166–84.

18. Jakovljevic M, Vukovic M, Chen CC, Antunovic M, Dragojevic-Simic V, Velickovic-Radovanovic R, Djendji MS, et al. Do health reforms impact cost consciousness of Health care professionals? Results from a nation-wide survey in the Balkans. Balkan Med J. (2016) 33:8–17. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.15869

19. Jakovljevic M, Zugic A, Rankovic A, Dagovic A. Radiation therapy remains the key cost driver of oncology inpatient treatment. J Med Econ. (2015) 18:29–36. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.971162

20. Kovačević A, Dragojević-Simić V, Rančić N, Jurišević M, Gutzwiller F, Matter-Walstra K, et al. End-of-life costs of medical care for advanced stage cancer patients. Vojnosanitetski Pregled. (2015) 72:334–41. doi: 10.2298/VSP1504334K

21. Jakovljevic M, Jovanović M, Lazić Z, Jakovljević V, Đukić A, Velicković R, et al. Current efforts and proposals to reduce healthcare costs in Serbia. Serbian J Exp Clin Res. (2011) 12:161–3. doi: 10.5937/sjecr1104161J

22. Eichler HG, Kong SX, Gerth WC, Mavros P, Jönsson B. Use of cost effectiveness analysis in health care resource allocation decision-making: how are cost effectiveness thresholds expected to emerge? Value Health. (2004) 7:518–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.75003.x

23. Mihailovic N, Kocic S, Jakovljevic M. Review of diagnosis-related group-based financing of hospital care. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. (2016) 3:2333392816647892. doi: 10.1177/2333392816647892

24. Jakovljevic M, Potapchik E, Popovich L, Barik D, Getzen TE. Evolving health expenditure landscape of the BRICS nations and projections to 2025. Health Econ. (2017) 26:844–52. doi: 10.1002/hec.3406

25. Korotayev A, Arkhangelsky V, Bogevolnov J, Goldstone J, Khaltourina GA, Malkov A, et al. Critical 10 Years. Demographic Policies of the Russian Federation: Successes and Challenges. Moscow: “Delo” Publishing House (RANEPA) (2015).

26. Jakovljevic MB, Milovanovic O. Growing burden of non-communicable diseases in the emerging health markets: the case of BRICS. Front Public Health. (2015) 3:65. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00065

27. Jakovljevic MB. The key role of the leading emerging BRIC markets in the future of global health care. Serbian J Exp Clin Res. (2014) 15:139–43. doi: 10.5937/sjecr1403139J

28. Musgrove P. Health insurance: the influence of the Beveridge Report. Bull World Health Organ. (2000) 78:845–6.

29. Chernichenko MY. H.A. Семашко – первый нарком здравоохранения: новый век-новые исследовательские горизонты (N.A. Semashko – the first people's commissar of health: a new century – new research horizons). History Med. (2014) 3:73–81. doi: 10.17720/2409-5583.t1.3.2014.38k

30. Reshetnikov VA, Tregubov VN, Mikeroa MS. Pоссийский опыт профессиональной подготовки врачей по специальности ≪Организация здравоохранения и общественное здоровье≫ (Russian experience of professional training of physicians in the specialty ≪Organization of public health service and public health≫). Problemy Zdorovya I Ekologii. (2017) 2:80–4.

31. Reshetnikov VA, Nesvizhsky YV, Kasimovskaya NA. H.A. Семашко – первый нарком здравоохранения: новый век-новые исследовательские горизонты (N.A. Semashko – theorist and organizer of public health). History Med. (2014) 3:24–9. doi: 10.17720/2409-5583.t1.3.2014.33t

32. Arsentyev EV, Reshetnikov VA. To the biography of N.A. Semashko: the activities of the first Commissar of Health in 1920-1925. Hist Med. (2018) 3:183–92. doi: 10.3897/hmj.5.3.32480

33. Gerlinger T, Schmucker R. A long farewell to the Bismarck system: incremental change in the german health insurance system. German Policy Studies/Politikfeldanalyse. (2009) 5:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.11.001

34. Kutzin J. Bismarck vs. Beveridge: is there increasing convergence between health financing systems. In: 1st Annual Meeting of SBO Network on Health Expenditure (Paris) (2011). p. 21–22.

35. Radevic S, Kocic S, Jakovljevic M. Self-assessed health and socioeconomic inequalities in Serbia: data from 2013 National Health Survey. Front. Pharmacol. (2016) 7:140. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00140

36. Gavrilović A, Trmčić S. Health insurance system in Serbia – quality, reform, financial sustainability. MEST J. (2013) 1:114–26. doi: 10.12709/mest.01.01.02.11

37. Nemec J, Kolisnichenko N. Market-based health care reforms in Central and Eastern Europe: lessons after ten years of change. Int Rev Admin Sci. (2006) 72:11–26. doi: 10.1177/0020852306061611

38. Łyszczarz B. Public-private mix and performance of health care systems in CEE and CIS countries. Oeconomia Copernicana. (2016) 7:169–85. doi: 10.12775/OeC.2016.011

39. Borda M. The role of private health care financing in the central and Eastern European countries. Ekonomika/Economics. (2008) 83:100–9.

40. Jakovljevic M. Health expenditure dynamics in Serbia 1995-2012. Hosp Pharmacol. (2014) 1:180–3. doi: 10.5937/hpimj1403180J

41. Arandarenko M, Golicin P. Serbia. In: Deacon B, Stubbs P, editors. Social Policy and International Interventions in South East Europe. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. (2007). p. 167–186. doi: 10.4337/9781847208606.00016

42. Vlahovic Z, Radojkovic D. Healthcare in Serbia in transition period. EPMA J. (2010) 1:601–6. doi: 10.1007/s13167-010-0055-9

43. Arsenijevic J, Pavlova M, Groot W. Measuring the catastrophic and impoverishing effect of household health care spending in Serbia. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 78:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.014

44. Vojvodic K, Terzic-Supic Z, Santric-Milicevic M, Wolf GW. Socio-economic inequalities, out-of-pocket payment and consumers' satisfaction with primary health care: data from the national adult consumers' satisfaction survey in Serbia 2009-2015. Front Pharmacol. (2017) 8:147. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00147

45. McCarthy M. Serbia rebuilds and reforms its health-care system. Lancet. (2007) 369:360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60173-1

46. Jakovljevic M, Romeu-Gordo L, Vukovic M, Krstic M. Gender-specific health-seeking behavior and income status among the elderly citizens of Serbia. Eastern Eur Bus Econ J. (2017) 3:67–86.

47. Stošić S, Karanović N. Health care economics in Serbia: current problems and changes. Vojnosanitetski Pregled. (2014) 71:1055–61. doi: 10.2298/VSP120205002S

48. Arsenijevic J, Pavlova M, Groot W. Out-of-pocket payments for health care in Serbia. Health Policy. (2015) 119:1366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.07.005

49. Ikegami N, Yoo BK, Hashimoto H, Matsumoto M, Ogata H, Babazono A, et al. Japanese universal health coverage: evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet. (2011) 378:1106–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60828-3

50. Jakovljevic M, Ranković A, Rančić N, Jovanović M, Ivanović M, Gajović O, et al. Radiology services costs and utilization patterns estimates in Southeastern Europe – A retrospective analysis from Serbia. Value Health Reg Issues. (2013) 2:218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2013.07.002

51. Dragović-Soso J. Rethinking Yugoslavia: Serbian Intellectuals and the ‘National Question' in Historical Perspective. Contemp Eur History. (2004) 13:170–84. doi: 10.1017/S0960777304001638

52. Jakovljevic M, Varavikova EA, Walter H, Wascher A, Pejcic AV, Lesch OM. Alcohol beverage household expenditure, taxation and government revenues in broader European WHO region. Front Pharmacol. (2017) 8:303. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00303

53. Nikitović V, Lukić V. Could refugees have a significant impact on the future demographic change of Serbia? Int Migrat. (2010) 48:106–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00519.x

54. Jakovljevic MM, Netz Y, Buttigieg SC, Adany R, Laaser U, Varjacic M. Population aging and migration—History and UN forecasts in the EU-28 and its east and south near neighborhood—One century perspective 1950–2050. Global. Health. (2018) 14:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0348-7

55. Andrić V, Arsić M, Nojković A. Public debt sustainability in Serbia before and during the global financial crisis. Econ Ann. (2016) 61:47–77. doi: 10.2298/EKA1610047A

56. Jakovljevic M, Camilleri C, Rancic N, Grima S, Jurisevic M, Grech K, et al. Cold war legacy in public and private health spending in Europe. Front Public Health. (2018) 6:215. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00215

57. Jakovljevic M, Lazarevic M, Milovanovic O, Kanjevac T. The new and old Europe: east-west split in pharmaceutical spending. Front Pharmacol. (2016) 7:18. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00018

58. Santric-Milicevic M, Vasic V, Terzic-Supic Z. Do health care workforce, population, and service provision significantly contribute to the total health expenditure? An econometric analysis of Serbia Human Resources for Health. Hum Resour Health. (2016) 14:50. doi: 10.1186/s12960-016-0146-3

59. Stojilković J. Growing number of pensioners and population aging in Serbia. J Geogr Inst “Jovan Cvijić”. (2011) 61:69–84. doi: 10.2298/IJGI1102069S

60. Jakovljevic MB. Resource allocation strategies in Southeastern European health policy. EurJ Health Econ. (2013) 14:153. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0439-y

61. Jakovljevic M, Arsenijevic J, Pavlova M, Verhaeghe N, Laaser U, Groot W. Within the triangle of healthcare legacies: comparing the performance of South-Eastern European health systems. J Med Econ. (2017) 20:483–92. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1277228

62. Andrić V, Arsić M, Nojković A. Fiscal reaction to interest payments - the case of Serbia. Industrija Casopis za Ekonomiku Industrije. (2016) 44:117–44. doi: 10.5937/industrija44-12031

63. Rakić B, Radenović T. The effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy in Serbia. Industrija. (2013) 41:103–22. doi: 10.5937/industrija41-4011

64. Bloom DE, Canning D. The health and wealth of nations. Science. (2000) 287:1207–9. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1207

65. Nordhaus WD. The Health of Nations: The Contribution of Improved Health to Living Standards (No. w8818). National Bureau of Economic Research (2002). doi: 10.3386/w8818

66. Tompa E. The impact of health on productivity: empirical evidence and policy implications. Rev Econ Perform Soc Prog. (2002) 2:181–202.

67. Straussman JD. An essay on the meaning (s) of “capacity building” – with an application to Serbia. Int J Public Admin. (2007) 30:1103–20. doi: 10.1080/01900690701434661

68. Avlijaš S, Bartlett W. The Political Economy of Decentralisation and Regional Policy in Serbia: Choices and Outcomes. LSEE Papers on Decentralisation and Regional Policy in South Eastern Europe (3). London: The London School of Economics and Political Science (2011). Available online at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63573

69. Fedosova RN, Rodionova EV.Формы участия государства, негосударственного и частного секторов в реализации социальной политики (Features of the ratio of government, non-government and private sectors in the framework of the corporate social responsibility). Manage Econ Syst Sci Electron J. (2014) 7:67. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2583219

70. Reutov NV. Государственная политика и практика обеспечения активного долголетия (Government policy and practice to ensure active longevity). Vestnik Universiteta. (2015) 13:291–3.

71. Petrić J, Maričić T, Basarić J. The population conundrums and some implications for urban development in Serbia. Spatium. (2012) 28:7–14. doi: 10.2298/SPAT1228007P

72. Smolnitskaya NY Общественное здоровье: политико-экономический аспект (Public health: political and economic aspect). Russian Econ Internet J. (2009) 2:839–47.

73. Supic ZT, Bjegovic V, Marinkovic J, Milicevic MS, Vasic V. Hospital management training and improvement in managerial skills: Serbian experience. Health Policy. (2010) 96:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.01.002

74. Kalmykov VV, Timonin RV. Социальная политика в стратегии экономической безопасности (Social policy in the economic security strategy). Vestnik Vladimirskogo Yuridicheskogo Instituta. (2017) 3:86–90.

75. Grigoriev VV. Государственная политика в сфере печатных СMИ (State policy in sphere of printed media). Sotsialnyi Communikatsii. (2011) 4:5–21.

76. Milenković MJ, Radojičić Z, Milenković D, Vukmirović D. Applying electronic documents in development of the healthcare information system in the Republic of Serbia. Comput Sci Inform Syst. (2009) 6:111–26. doi: 10.2298/CSIS0902111J

77. Nelson BD, Dierberg K, Šćepanović M, Mitrović M, Vuksanović M, Milić L, et al. Integrating quantitative and qualitative methodologies for the assessment of health care systems: emergency medicine in post-conflict Serbia. BMC Health Serv Res. (2005) 5:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-14

78. Tosevski DL, Milovancevic MP, Deusic SP. Reform of mental health care in Serbia: ten steps plus one. World Psychiatry. (2007) 6:115–7.

79. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Serbia: Europe's Largest Protracted Refugee Situation. (2017). Available online at: https://www.osce.org/serbia/24323?download=true

80. ReliefWeb. UNHCR Serbia Factsheet - February 2019. (2019). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/serbia/unhcr-serbia-factsheet-february-2019

81. B92. FM: Serbia has largest number of refugees and IDPs in Europe. (2017). Available online at: https://www.b92.net/eng/news/politics.php?yyyy=2017&mm=10&dd=24&nav_id=102632

82. Janošević S, DŽenopoljac V, Bontis N. Intellectual capital and financial performance in Serbia. Knowled Process Manage. (2013) 20:1–11. doi: 10.1002/kpm.1404

83. Živković V, Nikolić S, Lukić V, Živadinović N, Babić D. The effects of a new traffic safety law in the Republic of Serbia on driving under the influence of alcohol. Accident Anal Prevent. (2013) 53:161–5. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2013.01.012

84. Milovanovic DR, Pavlovic R, Folic M, Jankovic SM. Public drug procurement: the lessons from a drug tender in a teaching hospital of a transition country. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2004) 60:149–53. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0736-1

85. Lee R. The demographic transition: three centuries of fundamental change. J Econ Perspect. (2003) 17:167–90. doi: 10.1257/089533003772034943

86. Levina EI. История демографии как науки и ее роль в современной макроэкономической ситуации в Pоссии (Demography history as a science and its role in the modern macroeconomic situation in Russia). Tambov Univers Rev. Humanit. (2008) 11:409–13.

87. Cherkasskaya EA. Профессионально-демографический анализ занятости населения đ CCCP,PСФСP и УССP по данным всесоюзных переписей (Occupational-demographic analysis of the USSR population employment, the RSFSR and the Ukrainian SSR according to the All-Union d censuses). Gigiyena Truda i Professional'nye Zabolevaniya. (1991) 5:4–6.

Keywords: health care, public health expenditure, private health expenditure, Serbia, Semashko model

Citation: Krstic K, Janicijevic K, Timofeyev Y, Arsentyev EV, Rosic G, Bolevich S, Reshetnikov V and Jakovljevic MB (2019) Dynamics of Health Care Financing and Spending in Serbia in the XXI Century. Front. Public Health 7:381. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00381

Received: 27 August 2019; Accepted: 26 November 2019;

Published: 13 December 2019.

Edited by:

Nemanja Rancic, Faculty of Medicine, Military Medical Academy, SerbiaReviewed by:

Maja Račić, University of East Sarajevo, Bosnia and HerzegovinaMilena Gajic-Stevanovic, Institute of Public Health of Serbia, Serbia

Copyright © 2019 Krstic, Janicijevic, Timofeyev, Arsentyev, Rosic, Bolevich, Reshetnikov and Jakovljevic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mihajlo B. Jakovljevic, c2lkYXJ0YWdvdGhhbWFAZ21haWwuY29t

Kristijan Krstic

Kristijan Krstic Katarina Janicijevic2

Katarina Janicijevic2 Yuriy Timofeyev

Yuriy Timofeyev Gvozden Rosic

Gvozden Rosic Mihajlo B. Jakovljevic

Mihajlo B. Jakovljevic