- 1Department of Maternal and Child Health, School of Public Health, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 2School of Biological Sciences, Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin, Ireland

Introduction: Migration to another country may induce changes in infant feeding practices especially where such practices differ considerably between the two countries. This study was undertaken to compare the infant feeding practices between Chinese mothers who gave birth in Ireland (CMI) with immigrant Chinese mothers who gave birth in China (CMC), and to examine the factors that influence these practices.

Methods: A cross-sectional self-administrated survey was conducted among a convenience sample of 322 Chinese mothers living in Ireland. Data were obtained from mailed questionnaires. Infant feeding practices between CMC and CMI were compared by Chi-square or independent sample t-test. Binary logistic regression analyses were further performed to test the differences in infant feeding practices between two groups, after controlling for potential socio-demographic confounders.

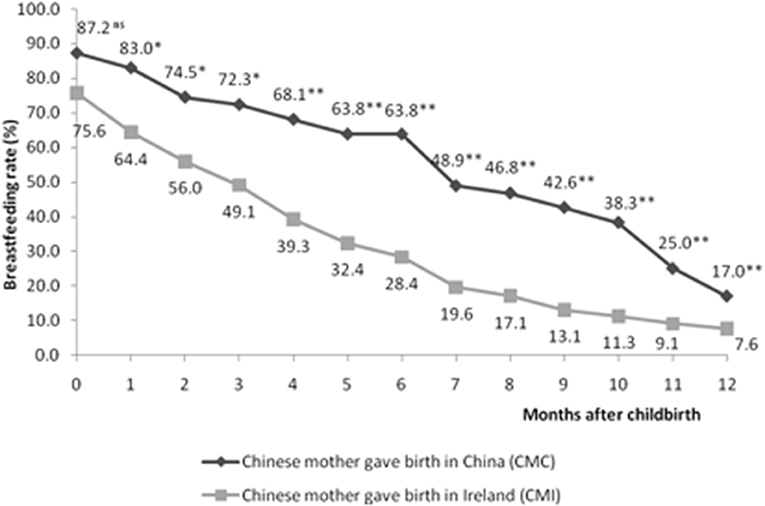

Results: High breastfeeding initiation rates were found in both groups (CMC: 87.2%; CMI: 75.6%); however sharp reductions in breastfeeding rates at 3 months (49.1%) and 6 months (28.4%) were found among CMI but not CMC (P < 0.05). Introduction of water within 1 week after childbirth was common for CMC in comparison with CMI. CMI were more likely than CMC to introduce infant formula to their child within the first 4 months after childbirth. The timing of introduction of rice porridge, vegetables, fruits and meats did not differ between CMC and CMI.

Conclusions: Cultural and perceptional factors, and changes caused by migration contribute to the decline in breastfeeding duration among CMI. Language-specific breastfeeding support and education among Chinese mothers in Ireland is needed, in particular to encourage mothers to breastfeed for 6 months or more.

Introduction

Factors associated with infant feeding practices, including maternal demographic, social, cultural and psychological, have been extensively explored (1, 2). Migration to another country may induce changes in infant feeding practices as the social environment and maternal socio-demographic status differ. A decrease in breastfeeding rates has been commonly reported in some Asian immigrant groups living in Western countries (3–7), which has been attributed to the transition from an extended to a nuclear family (8), an increased interest in Western norms (8), a need to work or study (8, 9), the social isolation caused by language barriers (6, 10), the availability of infant formula (11), an inability to access and consume traditional confinement foods (4, 12), conflict between their traditional practices and those of the host culture (13) and acculturation (14).

While the majority of mothers in China choose to breastfeed (15), previous studies found that immigrant Chinese mothers in Europe or North America seldom nursed their children (10, 16). Although the breastfeeding initiation rate remains high for Chinese mothers living in Australia, shorter breastfeeding duration was revealed (17). The perceptions of inadequate breast milk (5, 17) and inconvenience of breastfeeding, and the use of traditional infant solids are prevalent among the Chinese immigrants (18, 19).

Ireland's breastfeeding initiation rate is among the lowest in the world (20–22); despite some gradual increases over the last 10 years (23). Low rates of exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge (46.3%) (22) and at 6 months (15%) (24), and early introduction to complementary foods (before 12 weeks) (25) are reported. A 5-year breastfeeding action plan (2016–2021) has recently been published to improve breastfeeding rates and support mothers to breastfeed in Ireland (26). The population of non-nationals in Ireland has increased by 87% from the year 2002 (224,261 persons) to 2006 (419,733 persons). The number then stabilized at 544,357 persons in 2011 (27); but the most recent census data suggest these figures are rising again (28). A national infant feeding survey has suggested a need to understand the infant feeding practices of non-Irish women in Ireland (29). Hence, this project was undertaken to fill an information gap, to acquire an insight into the infant feeding practices of the Chinese, who represent one of the largest ethnic groups in Ireland (28, 30), and to determine to what extent maternal infant feeding practices have been influenced by migrating to Ireland. We compared Chinese mothers who gave birth in China (CMC) and Chinese mothers who gave birth in Ireland (CMI) in terms of their (1) breastfeeding rates, (2) milk feeding and weaning practices, and (3) potential influences of infant feeding.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were Chinese women who were born in China (including Hong Kong and Macau), had given birth to at least one child, and had been in Ireland for at least 6 months.

Data Collection

This study was advertised in a local Chinese newspaper and websites which were well-known among the Chinese in Ireland, and was announced in several Chinese communities in Ireland. Potential participants were approached at places frequented by Chinese mothers in Dublin and suburban areas, including Chinese supermarkets, Chinese weekend language schools for children, Chinese cultural music and dancing school, church organizations and Chinese restaurants, between September and December 2008. The purpose and demands of the study were explained to each potential participant, and mothers were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. The questionnaires were returned by mail and a follow-up telephone call was made to participants who failed to complete the questionnaire or who provided unclear information. A 5-euro shopping voucher was posted to each participant upon completion of the study. A “snowball” technique was used to increase the sample size, i.e. participants were required to help announce and distribute the survey to those who were known to them and met the inclusion criteria. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Dublin Institute of Technology. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants. Written permission to approach mothers was sought from the Chinese supermarket, restaurants, schools and church organizations. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Measures

A cross-sectional questionnaire was devised to seek retrospective information on mothers' infant feeding practices of their youngest child (index child), and to explore the influences on practices. Participants were asked to indicate the first liquid and solid they provided to the index child, and the timing of the introduction of a number of liquids and complementary foods. Mothers were asked to recount the reasons for their feeding decisions. Mothers who breastfed the index child were also required to report the planned and actual duration of breastfeeding and to render the reasons for breastfeeding cessation. Socio-demographic information (including mother's age at time of birth, marital status, birthplace, duration in Ireland, education, youngest child's birthplace and order) and potential influences on feeding practices (newborn's sleeping place, mother's delivery mode, source of support and influences of infant feeding, length of maternity leave, maternal beliefs and consumption of the traditional post-partum diet) were collected.

The questionnaire took approximately 30 min to complete. It was reviewed for content validity, reliability and cultural appropriateness by two breastfeeding specialists and a Chinese medical doctor. It was translated into Chinese and blind back-translated to check the accuracy of the translation (7). The questionnaire (Chinese) was pilot tested on 20 Chinese mothers in Ireland to assess clarity, redundancy and language adequacy.

Data Analyses

The participants were separated into two groups: Chinese immigrant mothers who gave birth to the index child in China (CMC) vs. Chinese immigrant mothers who gave birth to the index child in Ireland (CMI). Sample size was calculated according to Daly and Bourke (31) to ensure adequate numbers of participants in each group. It was estimated that the size of groups had 80% power to detect a difference. Pearson Chi-squared tests were conducted to assess the differences of infant feeding and their influential factors between CMC and CMI. Difference in the average timing of individual solids introduction was compared by an independent sample t-test. Binary logistic regression analyses were further conducted to test the differences in infant feeding practices between CMC and CMI, after controlling for potential confounders. Socio-demographic variables including maternal age at time of childbirth, mothers' duration in Ireland, child's order, child's age, maternal education level, marital status and maternal birthplace were adjusted in each regression model. Data analyses were conducted with SPSS (version 15). The level of 5% significance was used in statistical analyses.

In this paper, breastfeeding is taken to mean “any breastfeeding,” i.e., the child has received breast milk with or without other drink, formula or other infant food (15). Breastfeeding initiation was defined as mother put their baby to the breast at least once and gave any breast milk (32).

Results

Sample Characteristics

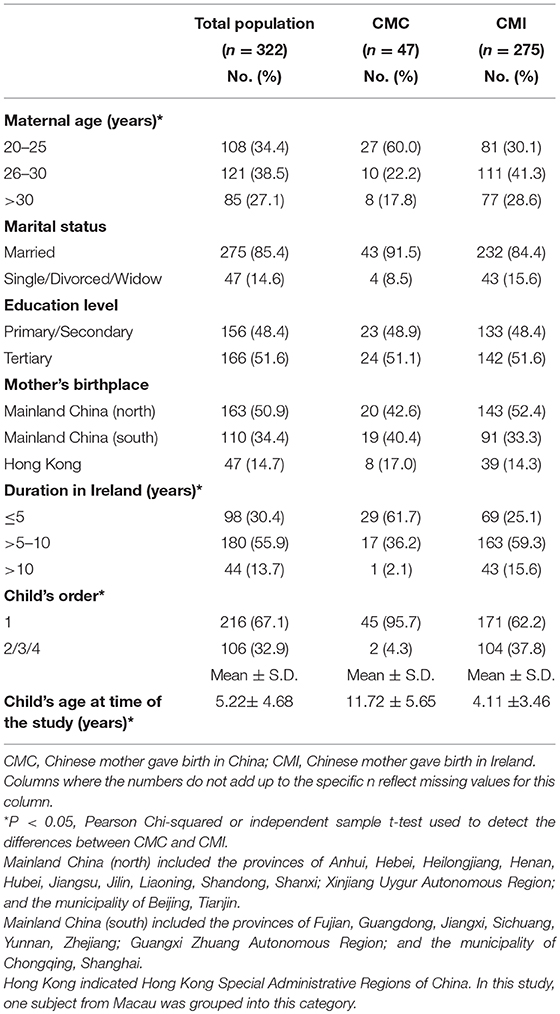

A total of 343 questionnaires were collected. With an exclusion of those who had not delivered their baby in China or Ireland, the final sample population was 322, including 47 CMC and 275 CMI. The majority of mothers were married, had a third level education (i.e., completed undergraduate and/or postgraduate study), and had been born in the northern part of mainland China. Three-fifths of CMC gave birth between 20 and 25 years old, whereas almost 70% of CMI were over 25 years old. The majority of CMC had been in Ireland for no more than 5 years however nearly 60% of CMI had been in Ireland between 5 and 10 years. Over 95% of CMC were primiparous compared with only 62.2% of CMI. The average age of children born in China was 11.72 (S.D. 5.65) years old while children born in Ireland were on average 4.11 (S.D. 3.46) years old (Table 1).

Breastfeeding Rates Between CMC and CMI

Figure 1 illustrates the “any breastfeeding” rates between CMC and CMI, from childbirth to 12 months of age. Initially, 41 out of 47 CMC (87.2%) and 208 out of 275 CMI (75.6%) breastfed their child. Rates of CMI dropped to 49.1% at 3 months and 28.4% at 6 months whereas the rate among CMC at 6 months remained above 60%. At 12 months, breastfeeding rates of CMC and CMI fell to 17 and 7.6%, respectively. Significant differences in breastfeeding rates between CMC and CMI were revealed from 1 to 3 months (P < 0.05), and even more distinct differences were found from 4 to 12 months (P < 0.001).

Figure 1. Breastfeeding prevalence between CMC (n = 47) and CMI (n = 275) at each month from birth to 12 months of life. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001; ns: no significant difference. Significance of relationships was calculated by Pearson Chi-squared tests.

Differences in Infant Feeding Patterns

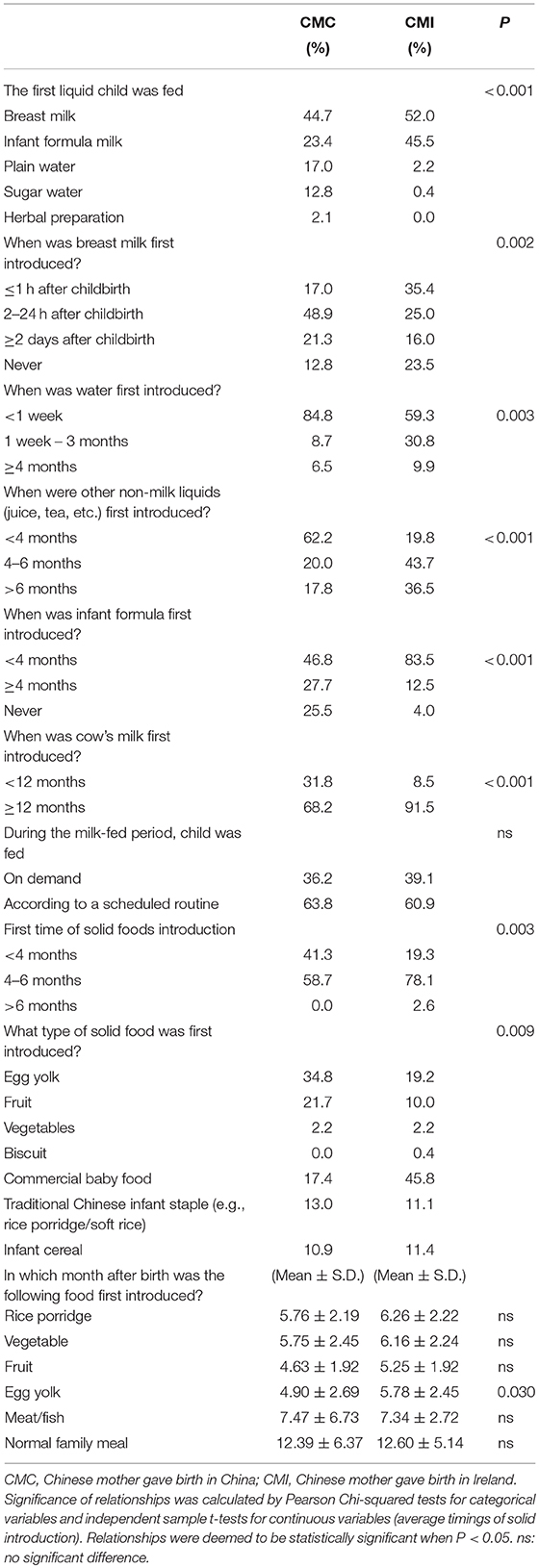

Univariate analyses revealed some differences in infant feeding practices between CMC and CMI. Most children born in China (44.7%) and Ireland (52.0%) were fed with breast milk first after birth. Breast milk was introduced sooner among CMI than CMC. For mothers who did not breastfeed at first, CMI mainly used infant formula (45.5%) while CMC mainly used non-milk liquids. More than 90% of infants born in either China or Ireland were given water before 4 months. The use of other non-milk-liquids (e.g., juice, tea) before 4 months was more prevalent among CMC (>62%) than CMI (<20%). The majority of CMI (>80%) introduced infant formula before 4 months, compared with 46.8% of CMC. Early introduction of cow's milk (<12 months) was found among 31.8% CMC and 8.5% of CMI. Over 60% of the children were fed according to a scheduled routine, with no difference between CMC and CMI (Table 2).

Over two-fifths of CMC gave their babies complementary foods before 4 months, compared with less than one-fifth of CMI. For the first solid foods introduced, egg yolk (34.8%) and commercial baby foods (45.8%) were commonly used by CMC and CMI, respectively. The proportions of mothers using traditional Chinese infant staples (e.g., rice porridge/soft rice) were similar between CMC and CMI. For the timing of solid introduction, fruit and egg yolk were introduced earlier (4–5 months), followed by rice porridge and vegetable (5–6 months), and meat/fish (7 months). A normal family meal was generally introduced after 1 years of age. No significant differences in the time of first introduction between CMC and CMI were found among most of the foods, except that egg yolk was found to be introduced earlier among CMC (4.90 ± 2.69, months) than CMI (5.78 ± 2.45, months) (P = 0.030) (Table 2).

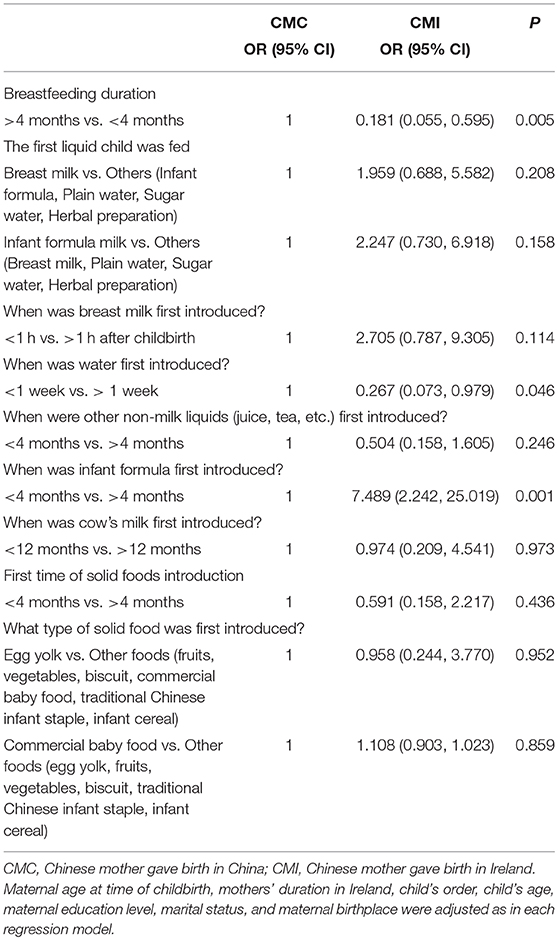

Multivariate analyses revealed that CMI was less likely breastfeed for 4 months and above (OR = 0.181, 95% CI: 0.055–0.595, P = 0.005), introduced water to their child within 1 week after childbirth (OR = 0.267, 95% CI: 0.073–0.979, P = 0.046), but more likely to introduce infant formula within 4 months after childbirth (OR = 7.489, 95% CI: 2.242–25.019, P = 0.001), in comparison to CMC, after controlling for potential confounders (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate analyses on infant feeding practices between CMC and CMI, after controlling for potential confounders.

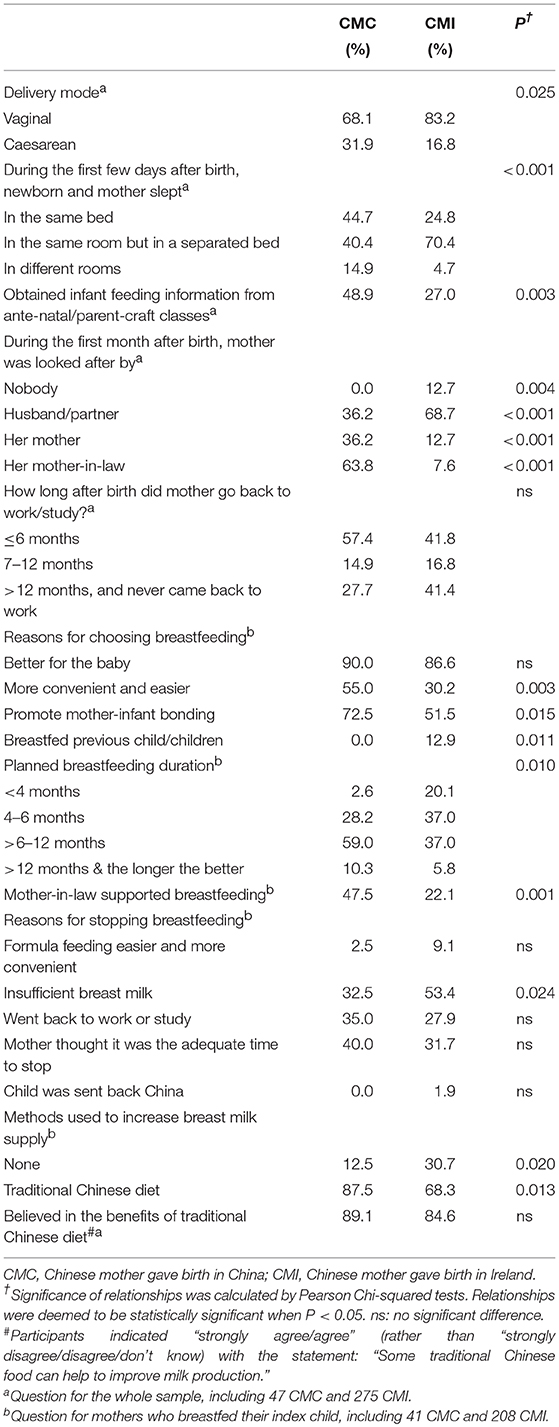

Factors Influencing Infant Feeding Practices of CMC and CMI

Over 83% of CMI delivered vaginally compared with only 68.1% of CMC. Most of the mothers roomed-in with their newborn during the first few days after childbirth, and CMC (44.7%) were more likely to bed-share with the newborn while CMI (70.4%) were more likely to sleep in a different bed. CMC and CMI reported similar sources of infant feeding information, including their own mother, doctors and other health professionals, friends, pamphlets or booklet, internet, etc. (data not shown), and a significantly higher proportion of CMC (48.9%) obtained the information from ante-natal/parent-craft classes, comparing with only 27.0% of CMI (P = 0.003) (Table 4). The husband was the most important source of family support in Ireland whereas the newborn's grandmothers played a more important role in China (P < 0.001). For breastfeeding mothers, CMC (47.5%) were more likely than CMI (22.1%) to receive breastfeeding support from their mother-in-law (P = 0.001). The majority of mothers went back to work or study before the first half year after childbirth but 41.4% of CMI stayed at home for at least 1 year (Table 4).

The benefits of breastfeeding to the babies were the main reasons given for breastfeeding, for both CMC and CMI. However, a significantly higher proportion of CMC breastfeeding mothers considered that breastfeeding promotes mother-infant bonding (72.5 vs. 51.5%) as well as being more convenient and easier (55 vs. 30.2%) than CMI breastfed mothers. About 13% of CMI breastfed because they had previous breastfeeding experience while none of the CMC indicated this reason (P = 0.011) (Table 4). “Formula feeding is more convenient” and “afraid baby being too attached” were indicated as the main reasons for mothers who had never breastfed (>25%, P > 0.05, data not shown). One-fifth of CMI planned to breastfeed for less than 4 months, compared with only 2.6% CMC. The majority of CMC planned to breastfeed for 6 to 12 months (59%) and another 10.3% planned to breastfeed for more than 1 year, while the corresponding figures for CMI were only 37.0 and 5.8%, respectively (P = 0.010). “Going back to work or study” as well as “it is the adequate time to stop” were the main reasons for breastfeeding discontinuation, among both CMC and CMI. About 2% of CMI breastfeeding mothers indicated sending the child back to China a few months after birth as one of the reasons for breastfeeding cessation. Over 53% of CMI breastfeeding mothers indicated insufficient breast milk as a reason, compared with 32.5% of CMC breastfeeding mothers (p = 0.024). To increase breast milk supply, 87.5% of CMC breastfed mothers consumed a special Chinese diet compared with 68.3% CMI (P = 0.013). A higher percentage of CMI did not use any methods to boost breast milk compared with CMC (P = 0.020) (Table 4).

Discussion

A higher percentage of CMI than CMC were recruited and CMI were more likely to have been in Ireland for a longer period. This reflects the fact that Chinese women tended to have babies after settling down in Ireland. An overwhelmingly high proportion of CMC were first-time mothers (n = 45, 95.7%), while only 2 (4.3%) CMC were multiparous. In comparison, 37.8% of CMI (n = 104) were multiparous. Such differences between CMC and CMI might be contributed by a younger maternal age at time of childbirth of CMC compared with CMI. Moreover, some mothers who had given birth in China might give birth to another child (the index child in the study) in Ireland. In addition, the differences revealed might be explained by the “One child policy” in China between 1979 and 2015 (33). CMC were only allowed to have one child in China at the time when this study was conducted. Our sample profile reflects the actual profile of the Chinese immigration mothers. Similar profile has been revealed among Chinese mothers in Australia (19).

Migration did not appear to have an influence on breastfeeding initiation in this study population, as rates of breastfeeding initiation for both CMC and CMI were close to 85% (the Chinese national target rate in 2010) (15). The high initiation rate of CMI corroborates previous Chinese migration studies undertaken in Australia (5, 17, 19) and Canada (34) and previous observations that non-Irish nationals were more likely to breastfeed than Irish nationals (29, 35). However, our results contrasted with earlier studies in the UK (10) and the US (16) that reported low breastfeeding initiation rates among Chinese immigrants. Such differences may be due to migrant composition (dominated by Hong Kong mothers in the earlier studies) and the time frame of these surveys (15–20 years earlier).

Multivariate analyses indicated that breastfeeding duration of CMI was significantly shorter than that of CMC. The breastfeeding duration of CMI was shorter than the mean duration (7–9 months) reported in the majority of cities in China (15). The decline in breastfeeding duration among CMI concurs with a number of Chinese migration studies (17, 34, 36) and other Asian migration studies (7, 9, 37) in Western countries. The consistency in these findings suggests the important influence of migration on breastfeeding duration.

Comparison of factors influencing infant feeding practices between CMC and CMI provides possible explanations for the shorter duration. Firstly, as revealed in our multivariate analyses, a greater and earlier use of infant formula among CMI may contribute to the decline of breastfeeding duration. Secondly, cultural belief that the traditional post-partum diet is beneficial to breast milk production was prevalent in this study population. CMI were less likely to have consumed the traditional diet and more likely to have indicated “not enough breast milk” than CMC. It is possible that a lack of consumption of such a diet was linked closely to the perception of insufficient breast milk production, and in turn induced the reduction of breastfeeding duration. This issue was also reported by Rossiter (38) among Vietnamese immigrants in Australia. Thirdly, smaller numbers of CMI received support from their mothers and mothers-in-law, who in this culture are typically supportive of breastfeeding (12). Furthermore, owing to a lack of family support, some babies born in Ireland were sent back to China a few months after birth to be looked after by their grandparents. The separation of mother and child unavoidably contributed to shorter breastfeeding duration. Fourthly, few CMI obtained infant feeding information from ante-natal/parent-craft classes. A lack of appropriate infant feeding information was also reported by Goel et al. (10) who attributed this to Chinese mothers' language problems in the UK. In contrast, decline in breastfeeding duration was not found among Chinese mothers in Australia who reported receiving more breastfeeding support and assistance from health professionals than mothers in their home countries (19). This would therefore emphasize the importance of such support to increase duration rates. Fifthly, a common reason for CMI to breastfeed was they had breastfed before, however CMC breast-feeders mainly considered breastfeeding easy, convenient and promoting closeness to the baby. A higher percentage of CMI breastfeeding mothers considered formula feeding easier and more convenient. Such perceptual differences may lead to the difference in planned breastfeeding duration and in turn the actual duration (39). Finally, the planned duration of breastfeeding among CMI was significantly shorter than that of CMC, which may contribute to a shorter actual duration of CMI comparing to CMC. A number of studies have revealed that planned duration was the strongest predictor of actual breastfeeding duration (40–43). Such association could be explained by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which states that most actions of social relevance are under volitional control and that individual intention to perform an action is an immediate determinant of action (44).

The decline in breastfeeding duration among CMI did not appear to be associated with maternal employment, a negative factor reported consistently (1, 2). A high proportion of CMI stayed at home for at least 1 year post-partum or never worked anymore, which confirmed the low rate of participation of Chinese women in the labor market in Ireland (45). This finding was consistent with Vietnamese women having a baby in the US (37) but contrasts with Vietnamese women in Australia, who entered the workforce as soon as possible after confinement in an attempt to establish themselves and their families in the new country (46).

Differences in infant feeding patterns implicate environmental influence on infant feeding. Infant formula and commercial infant foods are popular in the Irish market. With the free provision of infant formula in the hospital, formula feeding has dominated in Ireland (47). Feeding the infants with water within 1 week after childbirth is prevalent among CMC compared with CMI. Such phenomenon could be explained by the Chinese traditional practices of early introduction to water. Moreover, our results indicate that complementary feeding with non-milk-liquids and solids before 4 months is widespread in China, because Chinese mothers are commonly concerned about the nutritional inadequacy of their breast milk to their infant (15). Rice porridge and other solid foods were introduced at a similar time between CMC and CMI, which suggested the retention of certain weaning practices among Chinese immigrants in Ireland. These findings concurred with earlier studies in Australia (19) and Canada (34) that infant practices among Chinese immigrants were subject to both Western and Eastern influences.

Prevalence of formula feeding among CMI and early introduction of water and complementary feeding among CMC suggests a need to promote exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months among the Chinese. Education to feed the newborns on demand (48) is needed since most CMC and CMI fed according to a scheduled routine.

The potential for recall bias should be acknowledged, especially in the case of older children (49). However, the data may be relatively accurate because 95.7% of CMC had only one child with an average age of 11.7 years, and studies have demonstrated that the duration of breastfeeding can be remembered accurately up to 10 years later (50). In addition, results of this study were specific to Chinese mothers in Ireland, limiting the study's generalizability to Asian mothers in other countries. Finally, owing to the reality discussed previously that CMC was dominated by first-time mothers, sample size and characteristics of CMC and CMI were unequal. To minimize bias, multivariate analyses have been performed to control for some potential confounders (e.g., child's order, child's age, maternal age at time of childbirth).

In conclusion, a sharp decline in breastfeeding duration was observed among CMI. The difference in infant feeding patterns between CMC and CMI suggests the importance of environmental influences on infant feeding practices. Breastfeeding support and education among Chinese in Ireland is needed, in particular to extend breastfeeding duration.

Author Contributions

QZ was responsible for the study design and development, data collection and analyses and drafting the manuscript. JK and KY were involved in study design and development, gave critical review and comments on this manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Postgraduate R&D Skill, Strand I, the Republic of Ireland.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participation of Chinese mothers and the support of the Chinese communities in Ireland.

References

1. Thulier D, Mercer J. Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs (2009) 38:259–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01021.x

2. Meedya S, Fahy K, Kable A. Factors that positively influence breastfeeding duration to 6 months: a literature review. Women Birth (2010) 23:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.02.002

3. Rossiter JC. Attitudes of Vietnamese women to baby feeding practices before and after immigration to Sydney, Australia. Midwifery (1992) 8:103–12. doi: 10.1016/S0266-6138(05)80078-6

4. Rossiter JC, Yam BM. Breastfeeding: how could it be enhanced? The perceptions of Vietnamese women in Sydney, Australia. J Midwifery Women Health (2000) 45:271–6. doi: 10.1016/S1526-9523(00)00013-1

5. Homer CS, Sheehan A, Cooke M. Initial infant feeding decisions and duration of breastfeeding in women from English, Arabic and Chinese-speaking backgrounds in Australia. Breastfeed Rev. (2002) 10:27–32.

6. Chan-Yip A. Health promotion and research in the Chinese community in Montreal: a model of culturally appropriate health care. Paediatr Child Health (2004) 9:627–9. doi: 10.1093/pch/9.9.627

7. McLachlan HL, Forster DA. Initial breastfeeding attitudes and practices of women born in Turkey, Vietnam and Australia after giving birth in Australia. Int Breastfeed J. (2006) 1:7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-7

8. Desantis L. Infant feeding practices of Haitian mothers in south Florida: cultural beliefs and acculturation. Mat Child Nurs J. (1986) 15(2):77-89.

9. Babington L, Patel B. Understanding child feeding practices of Vietnamese mothers. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. (2008) 33(6):376-381. doi: 10.1097/01.NMC.0000341259.03298.26

10. Goel KM, House F, Shanks RA. Infant-feeding practices among immigrants in Glasgow. Br Med J. (1978) 2:1181–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6146.1181

11. James DC, Jackson RT, Probart CK. Factors associated with breast-feeding prevalence and duration among international students. J Am Dietet Assoc. (1994) 94:194–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90248-8

12. Fok D. Cross cultural practice and its influence on breastfeeding-the Chinese culture. Breastfeed Rev. (1996) 4:13–8.

13. Romero-Gwynn E. Breast-feeding pattern among Indochinese immigrants in northern California. Am J Dis Children (1960) (1989) 143:804–8.

14. Sussner KM, Lindsay AC, Peterson KE. The influence of acculturation on breast-feeding initiation and duration in low-income women in the US. J Biosoc Sci. (2008) 40:673–96. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007002593

15. Xu F, Qiu L, Binns CW, Liu X. Breastfeeding in China: a review. Int Breastfeed J. (2009) 4:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-4-6

16. Tuttle CR, Dewey KG. Determinants of infant feeding choices among southeast Asian immigrants in northern California. J Am Dietet Assoc. (1994) 94:282–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)90369-7

17. Diong S, Johnson M, Langdon R. Breastfeeding and Chinese mothers living in Australia. Breastfeed Rev. (2000) 8:17–23.

18. Roville-Sausse FN. Westernization of the nutritional pattern of Chinese children living in France. Public health (2005) 119:726–33. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.021

19. Li L, Zhang M, Scott JA, Binns CW. Infant feeding practices in home countries and Australia: Perth Chinese mothers survey. Nutr Dietet. (2005) 62:82–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2005.00006.x

20. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, Franca GV, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet (2016) 387:475–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7

21. EURO-PERISTAT Project SE, and EURONEOSTAT. European Perinatal Health Report. Paris: Institut de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM) (2013).

23. Brick A, Nolan A. Explaining the increase in breastfeeding at hospital discharge in Ireland, 2004-2010. Irish J Med Sci. (2014) 183:333–9. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-1012-0

25. Tarrant RC, Younger KM, Sheridan-Pereira M, White MJ, Kearney JM. Factors associated with weaning practices in term infants: a prospective observational study in Ireland. Br J. Nutr. (2010) 104:1544–54. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002412

26. HSE Breastfeeding in a Healthy Ireland: the HSE Breastfeeding Action Plan 2016 - 2021. Dublin: Health Service Executive (2016).

27. Central Statistics Office. Census 2011 Results. Profile 6: Migration and Diversity. Dublin: The Stationery Office (2012).

28. Central Statistics Office Census 2016 Summary Results-Part 1. Ireland: Central Statistics Office (2017).

29. Begley C, Gallagher L, Clarke M, Carroll M, Millar S. The National Infant Feeding Survey 2008. Dublin: Health Service Executive (2009).

30. Central Statistics Office. Census 2006 Non-Irish nationals living in Ireland. Dublin: The Stationery Office (2008).

31. Daly LE, Bourke GJ. Interpretation and Uses of Medical Statistics, 5th Edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science (2000).

32. Griffiths LJ, Tate AR, Dezateux C. The contribution of parental and community ethnicity to breastfeeding practices: evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol. (2005) 34:1378–86. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi162

33. Zeng Y, Hesketh T. The effects of China's universal two-child policy. Lancet (2016) 388:1930–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31405-2

34. Sit C, Yeung D, He M, Anderson G. The growth and feeding patterns of 9 to 12 month old Chinese Canadian infants. Nutr Res. (2001) 21:505–16. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(01)00263-9

35. Tarrant RC. An Investigation of the Diets of Infants Born in Ireland During the First Six Months of Life. Dublin: Dublin Institute of Technology (2008).

36. Chan-Yip AM, Kramer MS. Promotion of breast-feeding in a Chinese community in Montreal. Can Med Assoc J. (1983) 129:955–8.

37. Mistry Y, Freedman M, Sweeney K, Hollenbeck C. Infant-feeding practices of low-income Vietnamese American women. J Hum Lact. (2008) 24:406–14. doi: 10.1177/0890334408318833

38. Rossiter JC. Maternal-infant health beliefs and infant feeding practices: the perception and experience of immigrant Vietnamese women in Sydney. Contemp Nurse (1992) 1:75–76, 79–82. doi: 10.5172/conu.1.2.75

39. Vogel A, Hutchison BL, Mitchell EA. Factors associated with the duration of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr. (1999) 88:1320–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1999.tb01044.x

40. Scott JA, Landers MC, Hughes RM, Binns CW. Factors associated with breastfeeding at discharge and duration of breastfeeding. J Paediatr child Health (2001) 37:254–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00646.x

41. Blyth RJ, Creedy DK, Dennis CL, Moyle W, Pratt J, De Vries SM, et al. Breastfeeding duration in an Australian population: the influence of modifiable antenatal factors. J Hum Lact. (2004) 20:30–8. doi: 10.1177/0890334403261109

42. Bosnjak AP, Grguric J, Stanojevic M, Sonicki Z. Influence of sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics on breastfeeding duration of mothers attending breastfeeding support groups. J Perinatal Med. (2009) 37:185–92. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.025

43. O'Brien M, Buikstra E, Hegney D. The influence of psychological factors on breastfeeding duration. J Adv Nurs. (2008) 63:397–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04722.x

45. OECD. Balancing Work and Family Life: Helping Parents into Paid Employment. Employment Outlook. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2001).

46. Manderson L, Mathews M. Vietnamese attitudes towards maternal and infant health. Med J Aus. (1981) 1:69–72.

47. Twomey A, Kiberd B, Matthews T, O'Regan M. Feeding infants - an investment in the future. Irish Med J. (2000) 93:248–50.

49. Li R, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr Rev. (2005) 63:103–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00128.x

Keywords: breastfeeding, Chinese, Ireland, migration, infant feeding

Citation: Zhou Q, Younger KM and Kearney JM (2018) Infant Feeding Practices in China and Ireland: Ireland Chinese Mother Survey. Front. Public Health 6:351. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00351

Received: 12 June 2018; Accepted: 12 November 2018;

Published: 28 November 2018.

Edited by:

Saralee Glasser, Gertner Institute for Epidemiology & Health Policy Research, IsraelReviewed by:

Chris Fradkin, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, BrazilAmeer Ahmad, Quaid-i-Azam Medical College, Bahawalpur, Pakistan

Copyright © 2018 Zhou, Younger and Kearney. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qianling Zhou, cWlhbmxpbmcuemhvdUBiam11LmVkdS5jbg==

Qianling Zhou

Qianling Zhou Katherine M. Younger2

Katherine M. Younger2