- 1University of Texas Health Science at Houston School of Public Health, Houston, TX, United States

- 2Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3Harris County Public Health, Houston, TX, United States

- 4University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States

In Texas and across the United States, unintended pregnancy, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among adolescents remain serious public health issues. Sexual risk-taking behaviors, including early sexual initiation, contribute to these public health problems. Over 35 sexual health evidence-based programs (EBPs) have been shown to reduce sexual risk behaviors and/or prevent teen pregnancies or STIs. Because more than half of these EBPs are designed for schools, they could reach and impact a considerable number of adolescents if implemented in these settings. Most schools across the U.S. and in Texas, however, do not implement these programs. U.S. school districts face many barriers to the successful dissemination (i.e., adoption, implementation, and maintenance) of sexual health EBPs, including lack of knowledge about EBPs and where to find them, perceived lack of support from school administrators and parents, lack of guidance regarding the adoption process, competing priorities, and lack of specialized training on sexual health. Therefore, this paper describes how we used intervention mapping (Steps 3 and 4, in particular), a systematic design framework that uses theory, empirical evidence, and input from the community to develop CHoosing And Maintaining Effective Programs for Sex Education in Schools (iCHAMPSS), an online decision support system to help school districts adopt, implement, and maintain sexual health EBPs. Guided by this systematic intervention design approach, iCHAMPSS has the potential to increase dissemination of sexual health EBPs in school settings.

Introduction

In Texas and across the United States, unintended pregnancy, HIV, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among adolescents remain serious public health issues. In the U.S., the 2015 teen birth rate (among 15- to 19-year-old females) was 22.3 births per 1,000 (1). Furthermore, national estimates indicate that half of all new STIs occur among young people between the ages of 15 and 24 (2). Texas has one of the highest teen birth rates in the nation at 34.6 per 1,000 (3) and currently ranks sixth in the nation for the estimated number of HIV diagnoses among adults and adolescents (4). Sexual risk-taking behaviors, including early sexual initiation (5), are factors that contribute to these high rates of teen births and HIV/STIs (6–12).

National agencies, including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Adolescent Health (13) and National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy (14), have developed online repositories (or lists) of evidence-based HIV, STI, and teen pregnancy prevention programs [hereafter referred to as sexual health evidence-based programs (EBPs)]. These programs are designated as evidence-based because they have been rigorously evaluated (usually in an experimental or quasi-experimental design) and shown to reduce sexual risk behaviors (e.g., sexual initiation, contraceptive use, frequency of sexual activity, and number of sexual partners) and/or prevent teen pregnancies or STIs (13). Examples of sexual health EBP categories from these online repositories include abstinence education, comprehensive sexual health education (where abstinence is stressed but information on contraception is also included), and positive youth development programs. Over 35 sexual health EBPs are designed for multiple settings (e.g., school, after school, clinic, and home), but more than half are school based (13).

The broad dissemination of sexual health EBPs in school settings could reach a considerable number of adolescents and help adolescents delay sexual initiation and reduce other sexual behaviors that increase their risk for unintended pregnancy, HIV, and STIs (15, 16). Dissemination is often used to describe the adoption, implementation, and maintenance process for the delivery of a new innovation. A sexual health EBP is an “innovation” because it may be “perceived as new by an individual or unit of adoption” (17). Adoption refers to the decision to use a particular innovation (17, 18). Implementation refers to the process of program use, often measured in terms of general use, completeness (how much of the program is taught), and fidelity (adherence to core program elements) (19, 20). Maintenance, or institutionalization, refers to the process whereby a program is integrated fully into the practices and activities of an organization (21, 22).

Most school districts across the U.S. and in Texas do not adopt and implement sexual health EBPs (15, 23, 24). In Texas, there are many individual- and school district-level barriers that impede dissemination of these programs (and non-EBPs), including lack of knowledge about EBPs and where to find them, perceived lack of support from school administrators and parents, lack of guidance regarding the adoption process, competing priorities, lack of specialized training on sexual health, misinterpretation of state sexual education policies, and removal of health education as a graduation requirement (24–26). Many of these barriers are present nationally as well (27–29).

Many dissemination models for EBPs have been developed for various health topics, and some have been applied for sexual health (30–40). These models have some limitations, however, and have not been particularly successful in helping school districts disseminate sexual health EBPs. First, existing models provide guidance for adopting and implementing EBPs in community settings rather than school settings. Consequently, these models may be less helpful to school districts that are often characterized by complex organizational structures and decision-making processes (41–43). This complexity can make it challenging, in particular, for program administrators, teachers, and other stakeholders to use EBPs in schools. Examples of such tasks include getting district-level approval to adopt and implement the program, competing against other district priorities (e.g., standardized testing), and coordinating implementation across several campuses that have a diverse set of resources. Second, most models (e.g., ADAPT-ITT, McKleroy et al.’s framework) (35, 36) stress adaptation of EBPs to fit the target population’s needs and culture, which may not be practical for school districts, versus replication of EBPs. Program adaptation requires knowledge of how to balance intervention fit with program fidelity (44), as well as sufficient time and resources to pilot test the adaptation (35, 36, 44), which many school districts often lack. In addition, because of the sensitive nature of the topic, an adaptation to a sexual health EBP that is improperly conducted could potentially negatively impact students. Subsequently, a program that is not properly adapted may not produce the same results as the original EBP (44). Thus, a more practical option for school districts may be to replicate an EBP with fidelity. Third, previous models (e.g., RE-AIM, Getting to Outcomes) (30, 38) provide theoretical guidance on what needs to be accomplished to adopt, implement, and maintain EBPs (or change some general behavior, as in the transtheoretical model) (39), but they do not give step-by-step direction on how to complete these tasks, particularly in school settings. This type of practical guidance is critical for the successful dissemination of sexual health EBPs in complex school settings.

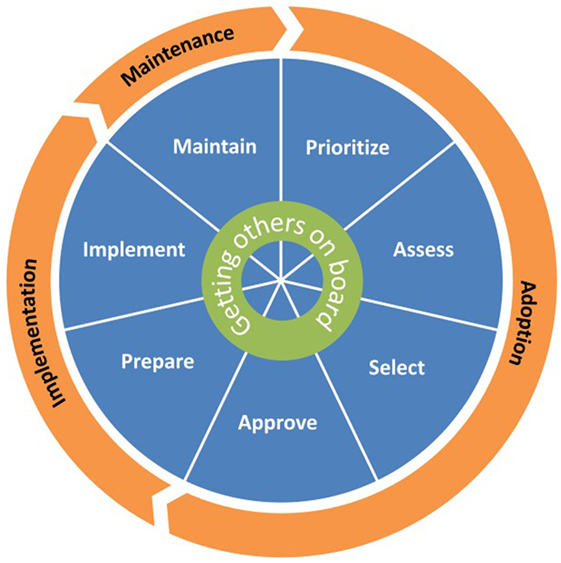

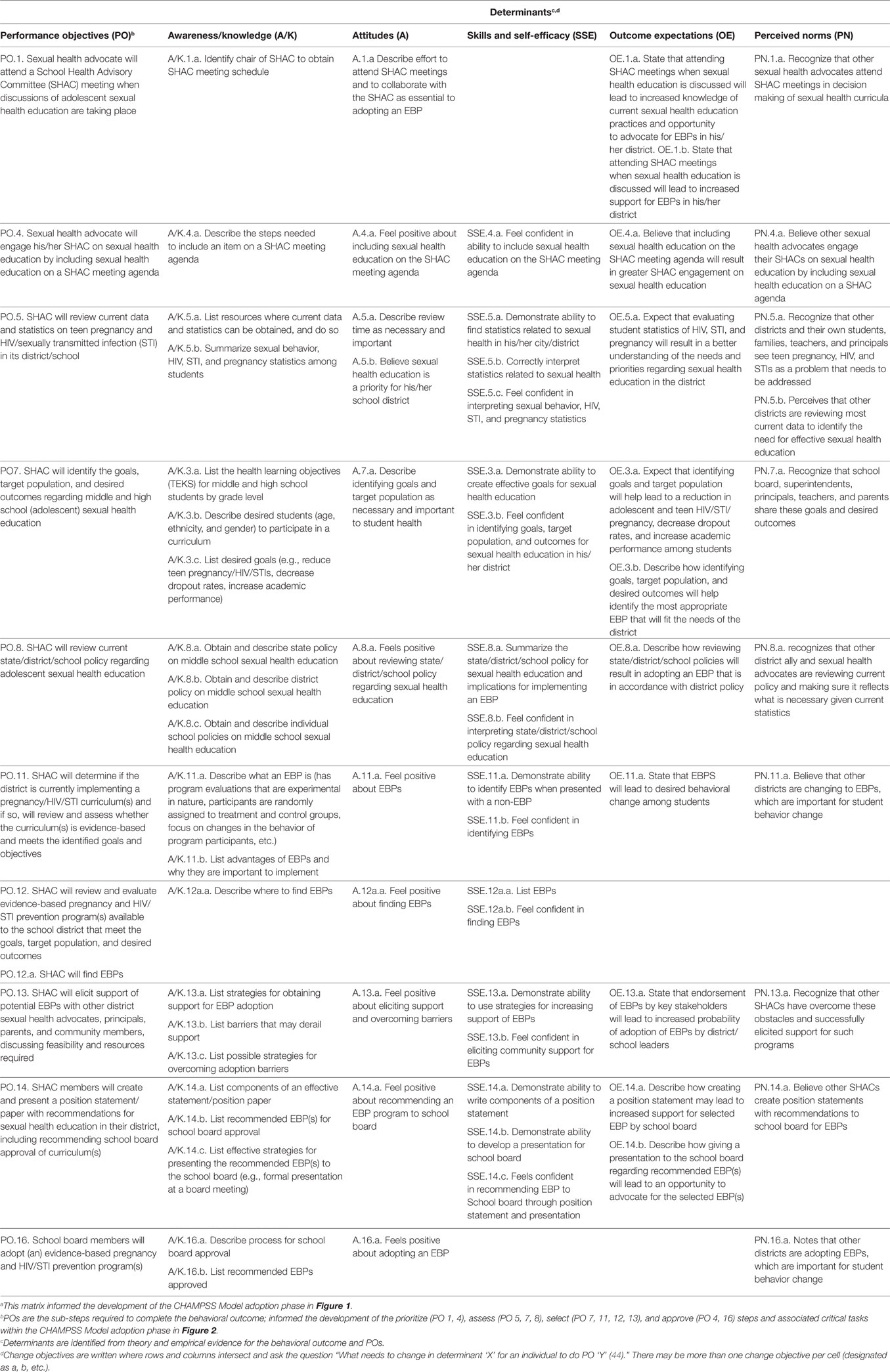

To overcome limitations of these previous dissemination models, we used intervention mapping (IM), a six-step systematic process that uses theory, empirical evidence, and community input (44) to develop the CHoosing And Maintaining Effective Programs for Sex Education in Schools (CHAMPSS) Model. Specifically, we used IM Step 1 (conduct logic model of the problem, including needs assessment) and Step 2 (develop matrices of change objectives for each behavioral outcome) to develop the model. The development of the model using these IM steps has been described in detail elsewhere (25). Briefly, we developed three matrices for three behavioral outcomes—adopt, implement, and maintain—which ultimately informed the development of the CHAMPSS Model described below and in Figures 1 and 2. As an example, a partial IM matrix for the adopt behavioral outcome is provided in Table 1.

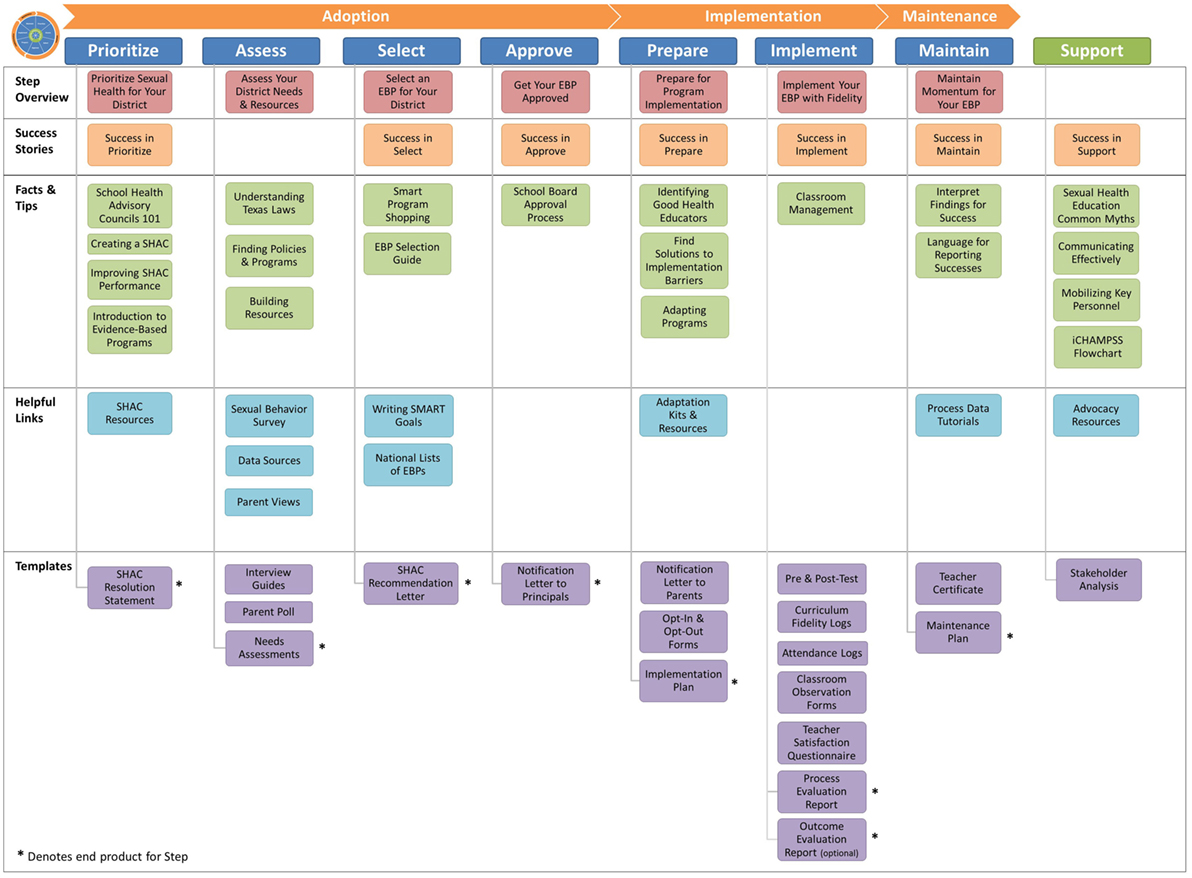

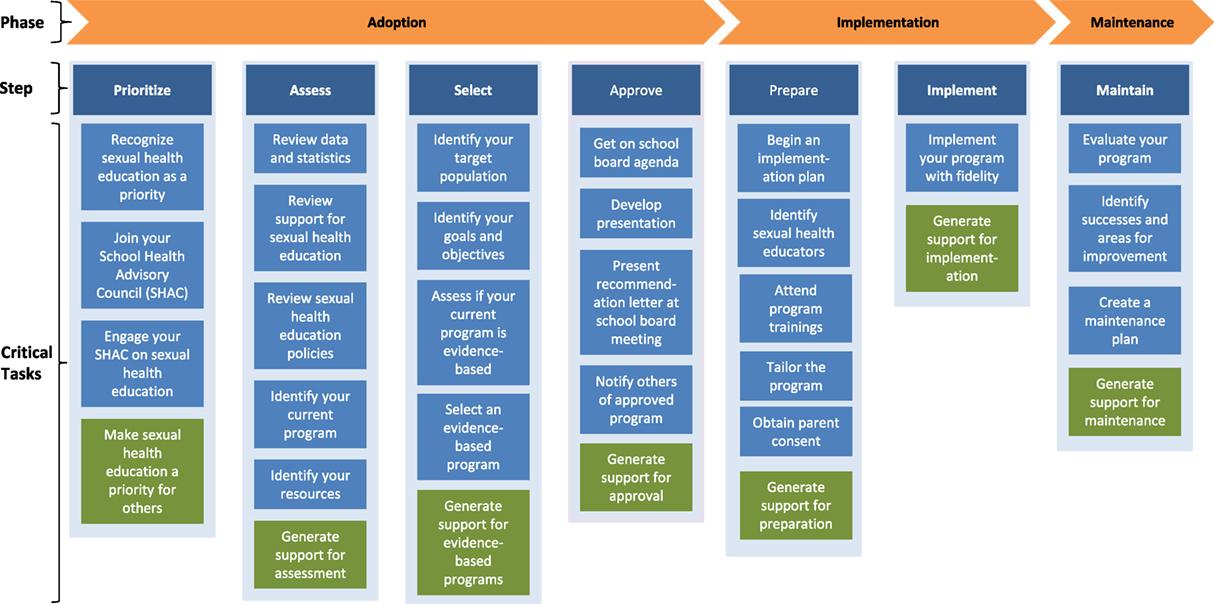

Figure 2. Steps and critical tasks for each phase in the CHoosing And Maintaining Effective Programs for Sex Education in Schools Model.

Table 1. Partial intervention mapping Step 2 matrix of change objectives for adopt behavioral outcomea: school district board members will adopt (i.e., vote to approve) a sexual health evidence-based program (EBP).

The CHAMPSS Model comprises three phases: “adoption,” “implementation,” and “maintenance” and seven steps: “prioritize,” “assess,” “select,” “approve,” “prepare,” “implement,” and “maintain.” A core element is “Getting Others on Board” (i.e., connecting with other supporters of EBPs and adolescent sexual health), which extends across all seven steps (Figure 1). Akin to some previous models (e.g., RE-AIM, Getting to Outcomes) (30, 38), the CHAMPSS Model is circular because school district stakeholders may enter the model at any step, depending on their readiness. Furthermore, school district stakeholders may complete one step but then realize that they need to go back to a previous step. A unique feature of the model, though, is the corresponding list of prescribed critical tasks that must be accomplished to complete a step (Figure 2). As an example, the performance objectives (PO) (sub-steps required to complete each behavioral outcome) (44) in Table 1 informed the development of the prioritize, assess, select, and approve steps and associated critical tasks within the CHAMPSS Model adoption phase in Figure 2.

Key stakeholders, who have the authority and ability to adopt, implement, and maintain sexual health EBPs in the school setting, are included throughout the CHAMPSS Model (25). Key adopter stakeholders may include members of the school district’s Board of Trustees (who vote to approve adoption of a sexual health EBP in the school district) and School Health Advisory Committee (SHAC, a school district subcommittee which includes parents—required by law in Texas—and makes health-related program recommendations to the school board) (45). Key implementers may include individuals at the school district level (e.g., a district curriculum coordinator) and at the local school level (e.g., principals, school curriculum coordinators, and teachers). Individuals responsible for maintaining implementation of a sexual health EBP may include district and school curriculum coordinators. In addition, any other person who is interested in and committed to supporting the dissemination of a sexual health EBP (a “sexual health advocate”) can be an adopter, implementer, or maintainer.

The CHAMPSS Model overcomes limitations of previous dissemination models because it specifically targets school district stakeholders; stresses replication with fidelity; and provides detailed, step-by-step instructions that include realistic tasks for school district stakeholders to accomplish in each step of the model (25). Although the CHAMPSS Model provides a useful guiding framework for school district stakeholders, we envisioned the development of an online decision support system that further operationalizes the steps of the model. This online decision support system would specifically guide users through the prescribed critical tasks within the CHAMPSS Model, provide resources and skills specific to each task, provide technical assistance to help overcome barriers, and foster linkages with users in other school districts. Thus, the purpose of this “Methods” paper is to describe how we used IM Steps 3, Program Design, and 4, Program Production, to develop this online decision support system, ultimately named iCHAMPSS (so named because it was the interactive version of the CHAMPSS Model).

Methods

The iCHAMPSS development group was an academic-community-health department collaboration that was formed during the development of the CHAMPSS Model (25). Group members comprised study investigators (epidemiologists, behavioral scientists, psychologists); masters-level staff trained in public health; county health department representatives; and the “CHAMPSS Group,” a group of school-based community stakeholders who themselves adopted the name of the model. Briefly, the CHAMPSS Group comprised individuals from a subgroup of the Harris County School Health Leadership Group that was convened by the Harris County Public Health department. This subgroup included 22 members and was formed to specifically help school districts in Harris County adopt and implement sexual health EBPs. Members of the CHAMPSS Group represented 15 area school districts and included parents, nurses, science curriculum coordinators, and SHAC representatives. The CHAMPSS Group met together bimonthly; study investigators and/or staff often presented at their meetings to provide skills related to using and implementing sexual health EBPs (e.g., developing program objectives, finding data on adolescent sexual health, and assessing parental support for EBPs) as well as to garner buy-in and input for iCHAMPSS intervention development. By working with the CHAMPSS Group, we hoped to ensure the development of a user-friendly and useful online decision support system for school districts.

To develop iCHAMPSS, the development group completed Steps 3 (Program Design) and 4 (Program Production) of IM (44). In Step 3, we used theory and empirical evidence to (a) identify intervention delivery vehicles and program themes; (b) identify theoretical methods and practical applications for each group of change objectives, organized by determinants, for each behavioral outcome; and (c) draft a program scope and sequence. According to Bartholomew and colleagues, “a theory- and evidence-based change method is a general technique for influencing the determinants of behaviors….” Practical applications include the intervention strategies used to operationalize those methods. It was also important to specify the “parameters” or situations under which a method is used appropriately. In Step 4, we used our methods and applications from Step 3 to (a) refine the iCHAMPSS program structure and organization; (b) prepare plans for program materials; (c) draft messages, materials, and protocols; and (d) pretest, refine, and produce materials. This study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Board.

Results

Step 3: Program Design

Program Delivery Vehicle and Theme

As part of the initial design process for iCHAMPSS, we first identified the delivery vehicle by which we would operationalize the CHAMPSS Model. Early on, during IM Steps 1 and 2, we had decided that we would use the Internet to create an online decision support system to accomplish this task. The Internet is widely used to transmit information, and members of the CHAMPSS Group agreed that a website would be the most efficient way to provide access to the iCHAMPSS tools and resources. Furthermore, the Internet has been widely used to disseminate information about sexual health EBPs (13, 14), although this information predominantly focuses on describing EBPs, providing program materials, and linking users to training resources. In addition, other online decision support systems have been designed to help health care providers make decisions regarding their patients’ symptoms and treatment plans within the clinical arena (46, 47). Recently, for example, an online decision support system was developed in Canada to promote the use of research evidence to inform decisions regarding public health (48). We also identified a program theme for the online decision support system, which was to be a sexual health advocate, or champion, for the dissemination of sexual health EBPs by school districts. Finally, we created an iCHAMPSS logo, which incorporated the round CHAMPSS Model, and the byline of the iCHAMPSS website (which appears on every web page) is “CHoosing And Maintaining Effective Programs for Sex Education in Schools.”

Methods and Practical Applications

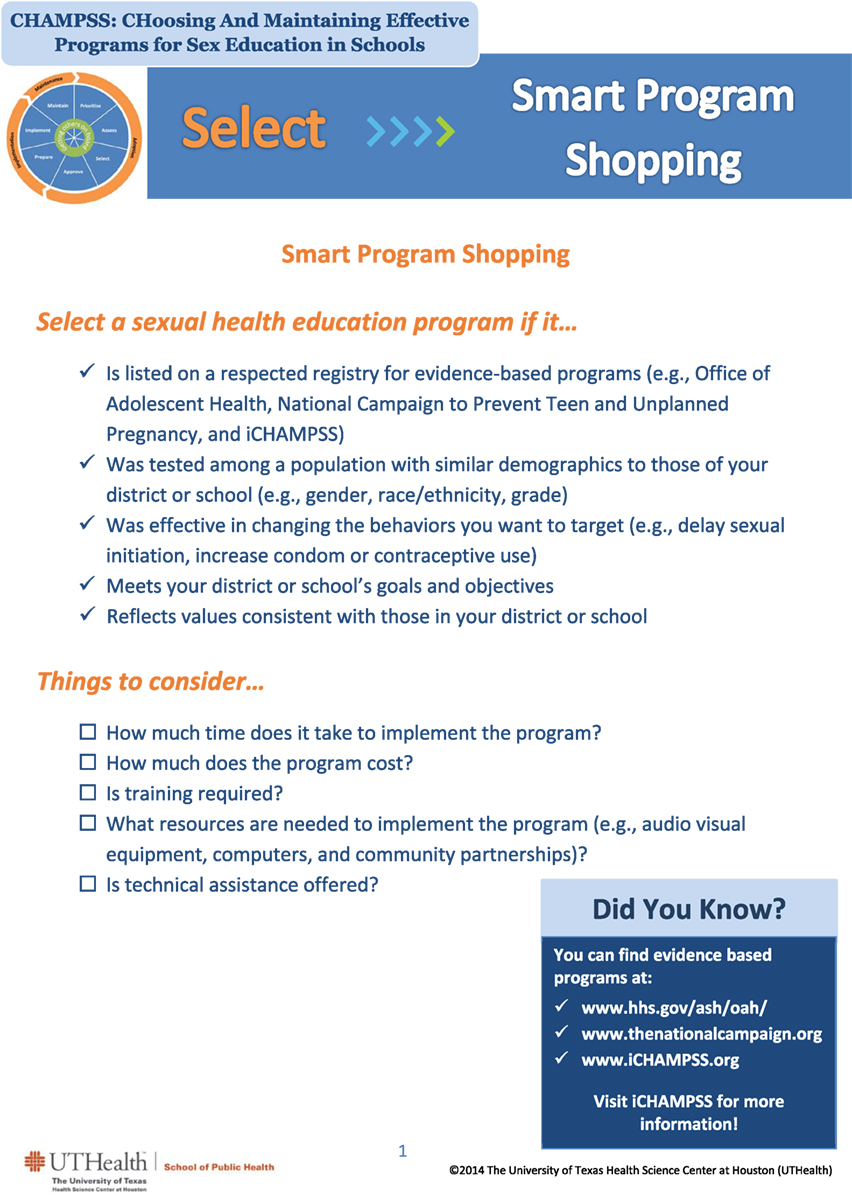

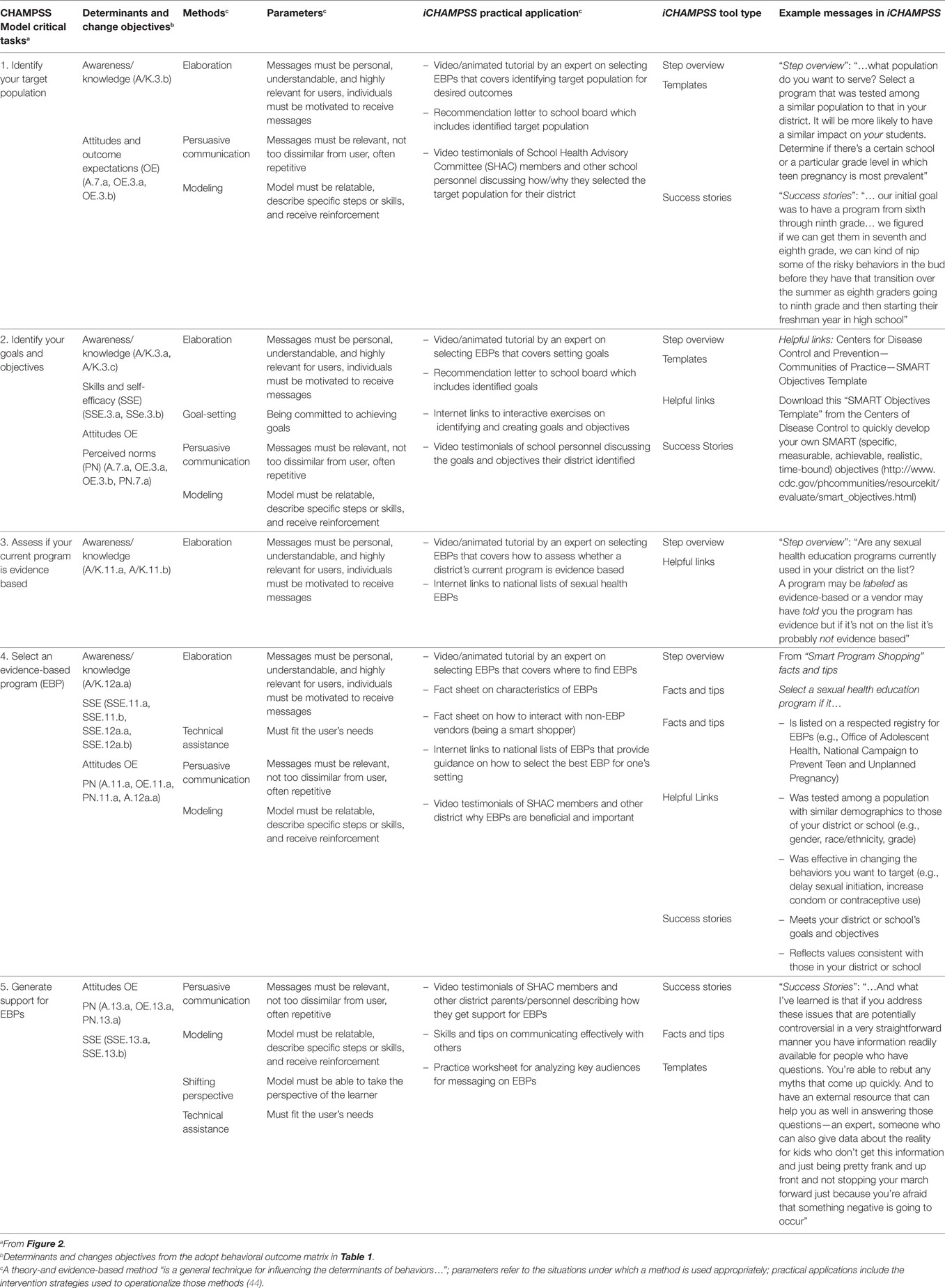

To begin the process of developing specific activities for iCHAMPSS, we identified methods, parameters, and practical applications. We used several behavioral science theories, including theories of information processing (44, 49), social cognitive theory (44, 50, 51), and diffusion of innovations (17) to identify specific methods for each group of change objectives, organized by determinants, for each behavioral outcome. Table 2 provides examples of methods, parameters, and practical applications for each critical task from the CHAMPSS Model adoption phase-select step (informed by the adopt behavioral outcome matrix provided in Table 1). For example, in task 1 (identify the target population), theories of information processing (44, 49) informed our use of elaboration as a theoretical method to influence change objectives associated with increasing awareness and knowledge related to describing the target population (age, ethnicity, and gender) for the EBP curriculum (change objectives A/K.7.b). In addition, modeling from social cognitive theory (44, 50, 51) was used to help promote more favorable attitudes and outcome expectations (OE) related to identifying the target population (change objectives A.7.a, OE.7.a, OE.7.b).

Table 2. Partial intervention mapping Steps 3 and 4: identifying methods, parameters, practical applications, tool types, and example messages for each critical task from the CHAMPSS Model adoption phase-select step.

Next, we brainstormed practical applications that would correspond to each theoretical method. For elaboration (theoretical method), we included a video/animated tutorial by an expert on selecting EBPs that covered identifying the target population for desired outcomes (practical application). Experts were members of the iCHAMPSS development group who were personal, motivating, understandable, and relevant to each school district, which were parameters for elaboration. To change attitudes and OE using modeling (theoretical method), we recommended a video-based testimonial of SHAC members and other school personnel discussing how and why they selected the target population for their school district (practical application). Models were similar to potential iCHAMPSS users (and, thus, relatable), explained the specific steps they used to overcome challenges, and expressed receiving reinforcement for their decisions (44), which were all parameters for modeling. Table 2 (first five columns) provides additional examples of the methods, parameters, and practical applications for the five critical tasks from the CHAMPSS Model adoption phase-select step (Figure 2), organized by determinants and change objectives from Table 1.

We also solicited input on other practical applications from the CHAMPSS Group. CHAMPSS Group members, in particular, requested a discussion forum to learn about what other school districts were doing. This suggestion corresponds to the method of interpersonal networking, which has been shown to facilitate adoption of effective programs by later users (17, 52, 53). CHAMPSS Group members also requested customizable templates that they could use, such as needs assessment and program evaluation forms, as well as tips sheets on engaging administrators, school board members, and others in getting district support for sexual health EBPs. These practical applications correspond to the method of facilitation from social cognitive theory (44, 50). The “Stage Your District” tool was another practical application suggested by the CHAMPSS Group. The original concept for this tool came from our partner at Harris County Public Health who had developed a simple four-question worksheet that would allow districts to determine in which stage of the CHAMPSS Model they were, indicating their level of readiness to adopt, implement, or maintain sexual health EBPs. At the beginning of every CHAMPSS Group meeting, members would stage themselves informally in the CHAMPSS Model, which they found useful for staying on track and monitoring progress. The “Stage Your District” practical application corresponds to the method of tailoring from the transtheoretical model (39, 44).

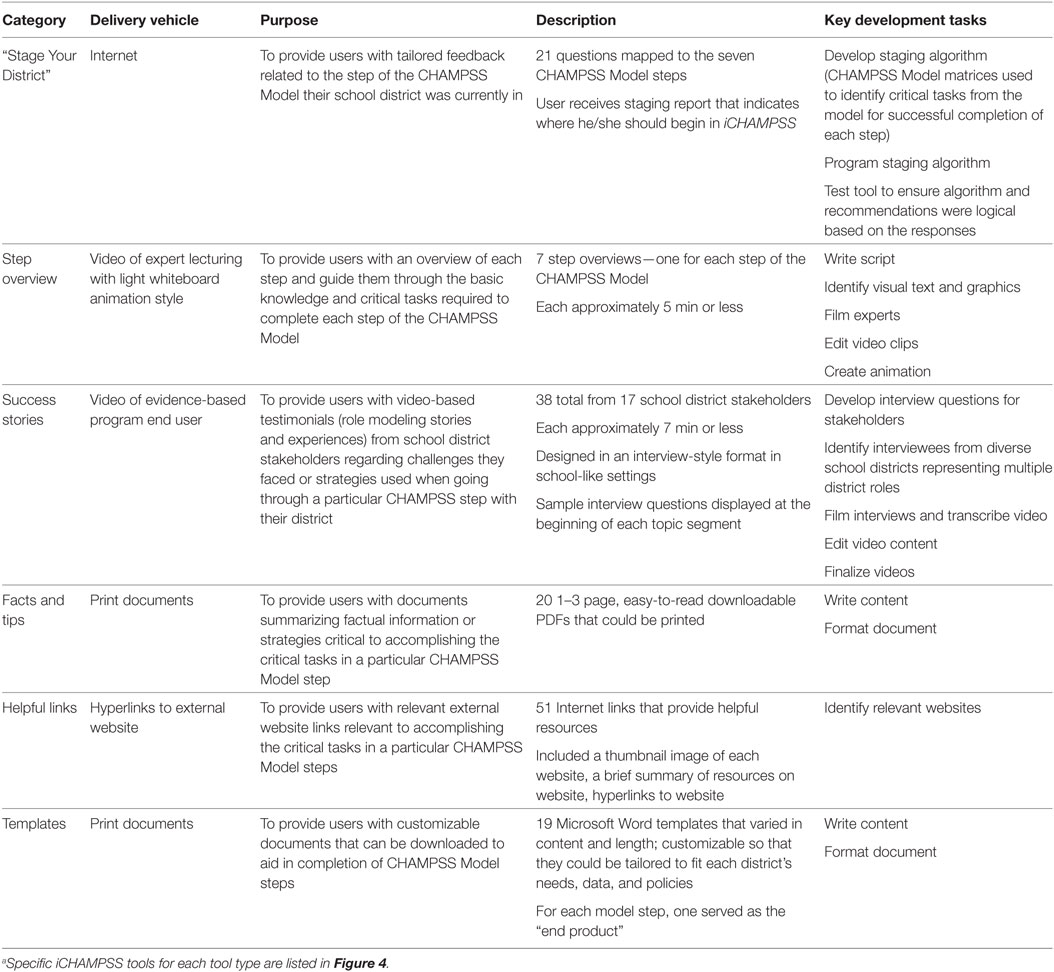

After examining the list of practical applications for all CHAMPSS Model critical tasks, organized by determinants and change objectives from each matrix, we identified some commonalities in the types of applications being proposed. These common practical applications included step overviews, success stories (videos/testimonials), facts and tips, helpful Internet links to outside resources, and templates. Next, we organized the list of practical applications by specific topical areas (e.g., sexual health priority, needs assessment, state law, and SHACs) to narrow the list and determine if there was any overlap among applications. These practical applications became known as the five types of “tools” available in iCHAMPSS. Table 2 (sixth column) provides an example of how the tool types were matched to practical applications.

Scope and Sequence

We described the scope and sequence of iCHAMPSS as self-directed and self-paced. However, we recommended that users (e.g., school district stakeholders) first complete the staging tool, “Stage Your District,” which would direct them to specific tools based on their level of readiness to adopt, implement, or maintain sexual health EBPs. Message tailoring is recognized as a crucial element in the creation of effective interactive health promotion programs (54). iCHAMPSS was also designed to allow users from any step of the CHAMPSS Model the flexibility to use whichever iCHAMPSS tools they deem most appropriate at any given time.

Step 4: Program Production

Refining Program Structure and Organization

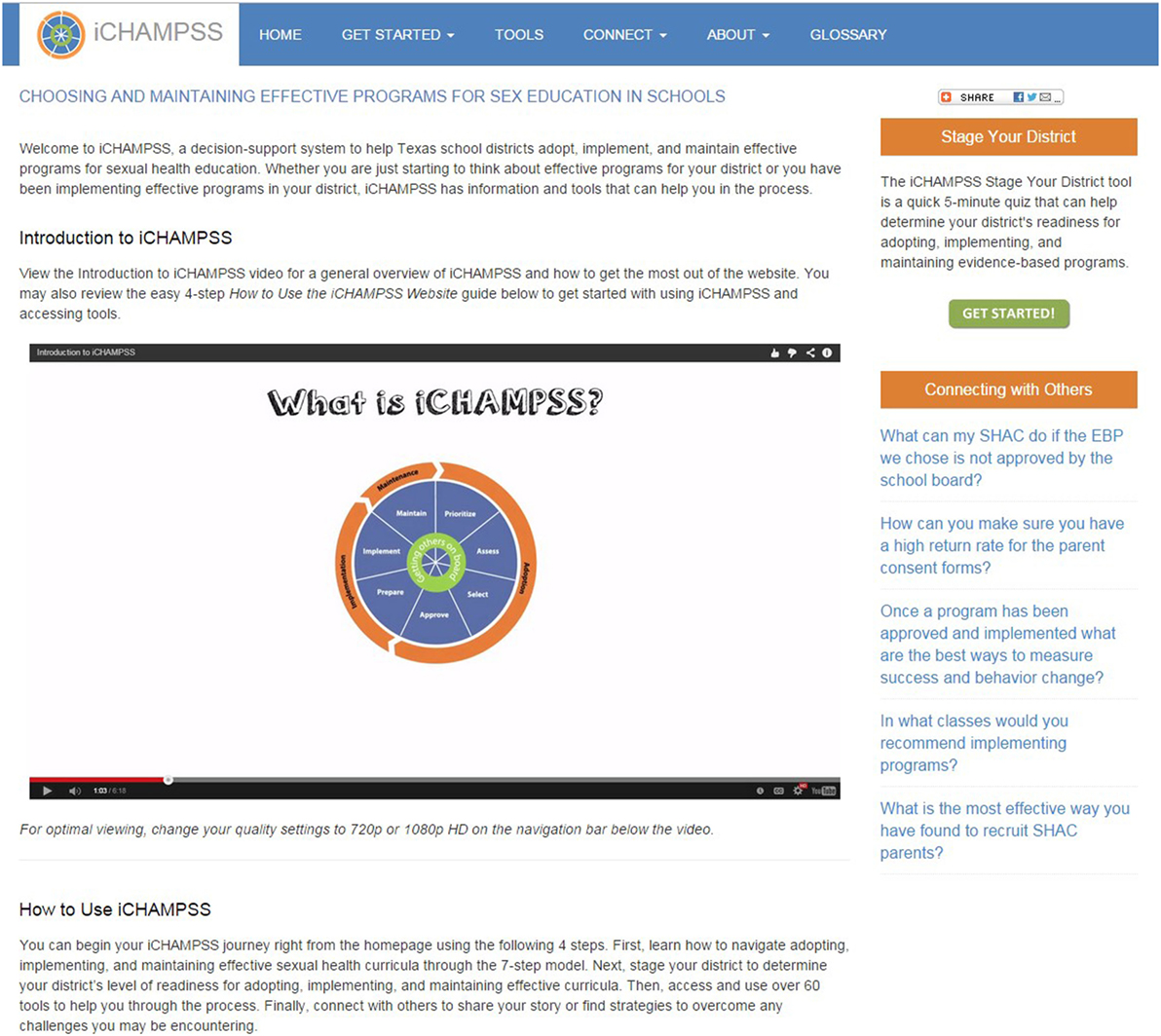

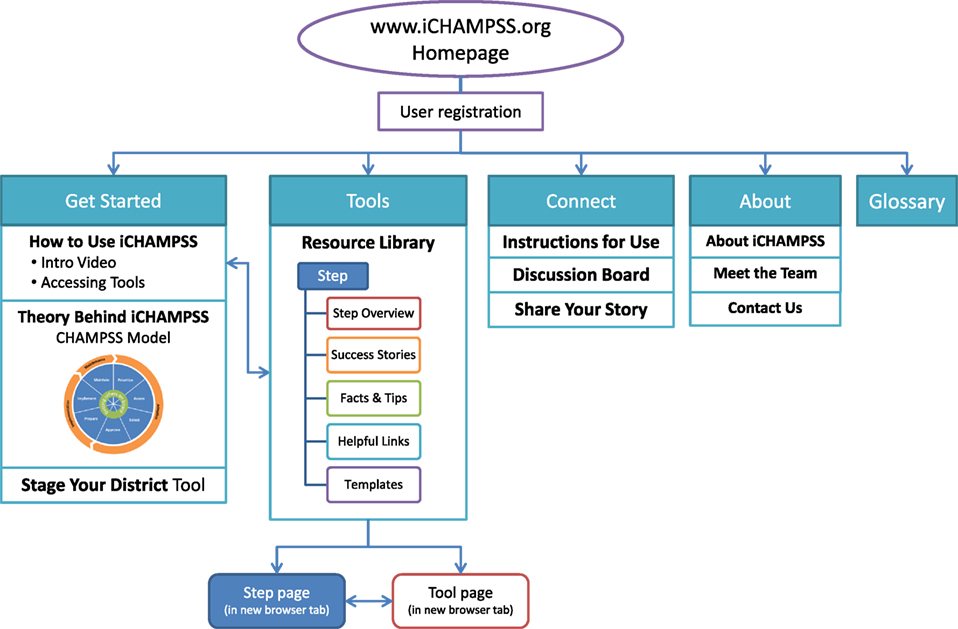

The goal of iCHAMPSS was to provide decision support to aid sexual health advocates in adopting, implementing, and maintaining a sexual health EBP in their district/school. To that end, iCHAMPSS included four features. The first feature, the CHAMPSS Model description, was designed to familiarize users to the CHAMPSS Model. In addition to introducing users to this conceptual framework, there is a video-based tutorial that guides users through the iCHAMPSS process to learn how all the iCHAMPSS tools and CHAMPSS Model steps fit together (see Figure 3). The second feature comprises the staging tool described in IM Step 3. Also described in IM Step 3, the third feature, the tools library, disseminates useful information and forms through the five iCHAMPSS “tool types” (step overviews, success stories, fact and tips, helpful Internet links, and templates). Users do not need to understand the CHAMPSS Model to find and use the tools. Finally, the fourth feature (also described in IM Step 3) comprises a linkage system, or online discussion board, to help users communicate with other users across school districts and receive technical assistance from experts in the field.

Preparing Plans for Program Materials

As part of IM Step 4, we developed design documents for iCHAMPSS’s features, website, and tools. Design documents are detailed planning documents that instruct the program designers on how to produce the program materials (44). For iCHAMPSS’s features and website, we developed a 35-page design document outlining their specifications. In this design document, we specified several critical features of iCHAMPSS (available online at http://www.iCHAMPSS.org), including how it would be accessible to school district stakeholders, data collection features (only basic site usage data to be collected but user sign-in is necessary for the discussion board), hosting and maintenance capabilities, development constraints (e.g., server specificities and compatibility with all Internet browsers), and user interface frame (i.e., header, dashboard, content space, and footer). We also specified what users would see on the iCHAMPSS homepage: the name and an introduction to the system, photographs indicating that the focus of the site is on the health of adolescents, social networking share buttons, and direct links with short descriptions to the CHAMPSS process, the tools library, and the connect with others forum. Embedded within the CHAMPSS process page is an image of the circular, seven-step CHAMPSS Model, which expands to give a description of each phase or step when the user clicks on that part of the model.

For the five tool types, we also developed design documents that specified the purpose/main objectives of the tools, target audience/likely users, instructions for use, format (e.g., PDF file and video), and detailed description of tool content. For each tool type, the goal was to develop a variety of tools mapped to each CHAMPSS step and associated critical tasks.

Drafting Messages, Materials, and Protocols

We procured the services of an IT developer, computer graphic designer, video production, and post-production specialists to design and produce iCHAMPSS’s website, features, and tools. However, we produced the content for the tools in-house, including the “Stage Your District” tool. We wrote the messages within each tool with the goals of accomplishing each critical task outlined in the CHAMPSS Model; these critical tasks were previously identified through the PO in each of the intervention matrices. One or two project team members initially developed each tool’s content, but we regularly included discussion of the tools to assess progress and address development questions and concerns in weekly meetings. Table 2 (seventh column) provides an example of how methods, parameters, and practical applications were operationalized to produce example messages that were incorporated into each of the tool types. During the development of messages, we also specified one of the templates as the “end product” for each CHAMPSS step that signified that step’s completion. We produced 62 tools, which are listed in a “tools library” on the iCHAMPSS website (Figure 4). See Figure 5 for screen capture of a selected facts and tips tool. Because we were producing a variety of tools with different delivery vehicles, the purpose and development approach varied for each tool (see Table 3 for a summary).

Table 3. iCHAMPSS “Stage Your District” tool and tool typesa: delivery vehicles, purpose, description, and development.

Pretesting, Refining, and Producing Materials

Members of the CHAMPSS Group reviewed iCHAMPSS after it was initially completed. Overall, the majority felt the website was professional, informative, and visually pleasing. However, some felt that the image on the homepage was too scientific and that the homepage lacked sufficient information to draw visitors to the website. Their suggestions included the following: (a) placing a prominent description of iCHAMPSS on the homepage; (b) reorganizing the placement of some of the dashboard buttons, and (c) including upcoming national and local trainings and events. Members of the CHAMPSS Group also reviewed the “Stage Your District” tool and suggested changing the color scheme and enabling a print option. Some felt that the staging tool was unclear. Lastly, project team members reviewed iCHAMPSS and tested it in different Internet browsers and on mobile phones to ensure that it would function on different platforms.

Based on these reviews, we made several changes to the website to clarify its purpose and specify where a user should begin. First, we revised the website name. Originally, CHAMPSS stood for “CHoosing And Maintaining Programs for Sex Education in Schools.” However, it was important to add the word “Effective” before the word “Programs” because this was a distinguishing feature of the website. We added this new tagline to every page of the website, so that the purpose of the website was clear. Second, we modified the dashboard to clearly direct users to a “Get Started” button. The “Get Started” button included three drop-down menus: “How to use iCHAMPSS,” “Theory behind iCHAMPSS,” and “Stage Your District.” Third, we added a direct link to the “Stage Your District” tool on the homepage and modified its color scheme to be more clear and visually appealing. We also included a brief description of this staging activity so that users would understand its purpose. Stylistic modifications were also made to the entire website, including changing coloring to be consistent throughout the website and fixing spacing issues. A final mock-up of the iCHAMPSS online decision support system is provided in Figure 6.

Members of the CHAMPSS Group also provided feedback during the development process of various tools, mainly the end product templates and facts and tips. Most CHAMPSS Group members reported that the tools were useful, feasible, and likely to be used by their districts. After the iCHAMPSS tools were developed, three project team members successively reviewed each tool to assess its content, readability, and ability to meet intended objectives. The original tool developer(s) then finalized the tool content based on the feedback from all reviewers and submitted the tool for one final review and approval by the project team.

To further assess the usability, acceptability, and potential impact of iCHAMPPS, we also conducted a pilot study with 16 participants who were given access to iCHAMPSS for 3 weeks (55). During this time period, participants could download and use any of the tools on the website. They were asked to complete a web-based pretest and immediate posttest using Qualtrics survey software. Participants included professional staff from school districts and community organizations throughout Texas, and parents of school-aged children. To recruit participants, we distributed (via e-mail) a flyer describing the study to our community partners, which include the state health department, school districts, community organizations, the Texas School Health Advisory Committee, and The Texas Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. A description of the study was also placed within the “Friday Beat,” the state health department’s weekly newsletter. Participants received a $50 gift card for completing both surveys. In summary, 16 participants reported that iCHAMPSS was motivational, easy to use, trustworthy, and helpful. They also reported that their self-efficacy for obtaining approval to implement an evidence-based sexual health education program from the School District Board significantly increased as a result of using iCHAMPSS. Elaborate results of this pilot test are published elsewhere (55).

Conclusion

Steps 3 and 4 of the IM process provided a systematic framework that was critical for translating the CHAMPSS Model (developed using IM Steps 1 and 2) into the iCHAMPSS online decision support system to help school district stakeholders adopt, implement, and maintain sexual health EBPs. Specifically, these steps provided a detailed process for ensuring that appropriate theoretical methods were identified and practical applications were developed to best meet the change objectives in the CHAMPSS Model matrices. The use of parameters, in particular, was most helpful in ensuring that the applications we chose best operationalized our chosen theoretical methods (44).

Some lessons can be learned from our experience developing iCHAMPSS. First, while we worked closely with the CHAMPSS Group to ensure the development of a system that was compatible with school district needs, time constraints prevented us from obtaining their feedback on every aspect of iCHAMPSS. For example, they never reviewed the final iteration of the discussion board, which was particularly disappointing because this feature was specifically requested by them. In addition, we received less feedback from the CHAMPSS Group on the implementation and maintenance plans because most group members did not have experience with these tasks (most CHAMPSS Group members were in the earlier stages of the CHAMPSS Model). It will be critical to obtain additional input on these tools from future iCHAMPSS users. Second, we learned important lessons about developing technology-based applications: (a) we did not anticipate the lengthy amount of time that would be needed to identify an appropriate IT developer and (b) it is important to adequately vet the IT developer to ensure that he/she has the requisite qualifications and communication skills. Regarding the former, the IT developer “search” process took approximately 9 months, which significantly delayed production of iCHAMPSS. For the latter, we had to hire a new IT developer mid-way through the development process because the original developer was not adequately meeting the needs of the project (e.g., the original “tools library” had to be rebuilt because the original programmed version did not allow us to add, delete, or format existing tools).

Future studies should focus on a rigorous evaluation of iCHAMPSS (IM Steps 5 and 6) to assess its impact on adoption, implementation, and maintenance of sexual health EBPs in school settings. This study should also assess the impact of iCHAMPSS on school district personnel’s psychosocial factors related to adoption, implementation, and maintenance, such as knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, and perceived support for sexual health EBPs. If effective in improving these outcomes, iCHAMPSS could serve as a model implementation science practice for sexual health EBPs nationally. Furthermore, iCHAMPSS could be adapted to increase dissemination of school-based EBPs that address other adolescent health issues, such as substance use and violence prevention.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of “University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Institutional Review Board” with passive informed consent from all subjects when required, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This publication only described our intervention development process. Verbal permission from the community advisory board partners for their input was obtained during the development process. The papers by Hernandez et al. (25, 55) did require passive informed consent which was required and stated in those manuscripts.

Author Contributions

All authors (MP, BH, EG, PC, DL, ER, KR-H, YR, KJ-B, SE, and RS) made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data; drafted the work or critically revised it for important intellectual content; provided final approval of the manuscript; and agreed to be accountable to all aspects of the work.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lionel Santibáñez for his editorial assistance. A modified version of this paper was originally published as a case study in Bartholomew Eldredge et al. (44) (Bartholomew 4e Book Companion Site, Jossey Bass 2016). Permission has been granted to publish this work from Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, USA. Earlier versions of Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2 were published in Hernandez et al. (25). Permission has been obtained to publish these tables and figures from Dr. Christopher Greely, Editor-in-Chief. Figure 4 was published in Hernandez et al. (55). Permission has been obtained to publish this figure from SAGE Publications.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP001949), Office of Adolescent Health (OAH), and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (grant number FTP1AH000072).

References

1. Hamilton BE, Mathews TJ. Continued declines in teen births in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief (2016) 259:1–8.

2. Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis (2013) 40(3):187–93. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53

3. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Texas Data. (2017). Available from: https://thenationalcampaign.org/data/state/texas

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015. (2016). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1991-2013 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. (2015). Available from: http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Default.aspx

6. O’Donnell L, O’Donnell CR, Stueve A. Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex-related risks among urban minority youth: the reach for health study. Fam Plann Perspect (2001) 33(6):268–75. doi:10.2307/3030194

7. Flanigan CM. Sexual activity among girls under age 15: findings from the National Survey of Family Growth. In: Albert B, Brown S, Flanigan CM, editors. 14 and Younger: The Sexual Behavior of Young Adolescents. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy (2003). p. 57–64.

8. Philliber S, Carrera M. Sexual behavior among young teens in disadvantages areas of seven cities. In: Albert B, Brown S, Flanigan CM, editors. 14 and Younger: The Sexual Behavior of Young Adolescents. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy (2003). p. 103–6.

9. Magnusson BM, Nield JA, Lapane KL. Age at first intercourse and subsequent sexual partnering among adult women in the United States, a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:98. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1458-2

10. Heywood W, Patrick K, Smith AM, Pitts MK. Associations between early first sexual intercourse and later sexual and reproductive outcomes: a systematic review of population-based data. Arch Sex Behav (2015) 44(3):531–69. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0374-3

11. Epstein M, Bailey JA, Manhart LE, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, et al. Understanding the link between early sexual initiation and later sexually transmitted infection: test and replication in two longitudinal studies. J Adolesc Health (2014) 54(4):435–41. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.016

12. Sandfort TG, Orr M, Hirsch JS, Santelli J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: results from a National US study. Am J Public Health (2008) 98(1):155–61. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444

13. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Evidence-Based TPP Programs. (2017). Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/grant-programs/teen-pregnancy-prevention-program-tpp/evidence-based-programs/index.html

14. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Sex Education and Effective Programs. (2017). Available from: https://thenationalcampaign.org/featured-topics/sex-education-and-effective-programs

15. Kirby D. The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res (2002) 39(1):27–33. doi:10.1080/00224490209552116

16. Thomas A. Policy Solutions for Preventing Unplanned Pregnancy. (2012). Available from: http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2012/03/unplanned-pregnancy-thomas

18. Olstad DL, Campbell EJ, Raine KD, Nykiforuk CI. A multiple case history and systematic review of adoption, diffusion, implementation and impact of provincial daily physical activity policies in Canadian schools. BMC Public Health (2015) 15(1):385. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1669-6

19. Wang B, Stanton B, Deveaux L, Poitier M, Lunn S, Koci V, et al. Factors influencing implementation dose and fidelity thereof and related student outcomes of an evidence-based national HIV prevention program. Implement Sci (2015) 10(1):44. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0236-y

20. Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Hansen WB, Walsh J, Falco M. Quality of implementation: developing measures crucial to understanding the diffusion of preventive interventions. Health Educ Res (2005) 20(3):308–13. doi:10.1093/her/cyg134

21. Parham DL, Goodman R, Steckler A, Schmid J, Koch G. Adoption of health education-tobacco use prevention curricula in North Carolina school districts. Fam Community Health (1993) 16(3):56–67. doi:10.1097/00003727-199310000-00008

22. Steckler A, Goodman RM. How to institutionalize health promotion programs. Am J Health Promot (1989) 3(4):34–43. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-3.4.34

23. Crosse S, Williams B, Hagen CA, Harmon M, Ristow L, DiGaetano R, et al. Prevalence and Implementation Fidelity of Research-Based Prevention Programs in Public Schools: Final Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Education (2011).

24. Wiley D, Miller F, Quinn D, Valentine R, Miller K. Conspiracy of Silence: Sexuality Education in Texas Public Schools. (2017). Available from: http://a.tfn.org/sex-ed/tfn-sex-ed-report-2016-web.pdf

25. Hernandez BF, Peskin M, Shegog R, Markham C, Johnson K, Ratliff EA, et al. Choosing and maintaining programs for sex education in schools: the CHAMPSS model. J Appl Res Child (2011) 2(2):1–33.

26. Peskin MF, Hernandez BF, Markham C, Johnson K, Tyrrell S, Addy RC, et al. Sexual health education from the perspective of school staff: implications for adoption and implementation of effective programs in middle school. J Appl Res Child (2011) 2(2):1–38.

27. Demby H, Gregory A, Broussard M, Dickherber J, Atkins S, Jenner LW. Implementation lessons: the importance of assessing organizational “fit” and external factors when implementing evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs. J Adolesc Health (2014) 54(3 Suppl):S37–44. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.022

28. Craft LR, Brandt HM, Prince M. Sustaining teen pregnancy prevention programs in schools: needs and barriers identified by school leaders. J Sch Health (2016) 86(4):258–65. doi:10.1111/josh.12376

29. Fagen MC, Stacks JS, Hutter E, Syster L. Promoting implementation of a school district sexual health education policy through an academic-community partnership. Public Health Rep (2010) 125(2):352–8. doi:10.1177/003335491012500227

30. Chinman M, Imm P, Wandersman A. Getting to Outcomes 2004: Promoting Accountability through Methods and Tools for Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation. (2004). Available from: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2004/RAND_TR101.pdf

31. Lesesne CA, Lewis KM, White CP, Green DC, Duffy JL, Wandersman A. Promoting science-based approaches to teen pregnancy prevention: proactively engaging the three systems of the interactive systems framework. Am J Community Psychol (2008) 41(3–4):379–92. doi:10.1007/s10464-008-9175-y

32. Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Arthur MW, Egan E, Brown EC, Abbott RD, et al. Testing communities that care: the rationale, design and behavioral baseline equivalence of the community youth development study. Prev Sci (2008) 9(3):178–90. doi:10.1007/s11121-008-0092-y

33. Spoth R, Greenberg M. Impact challenges in community science-with-practice: lessons from PROSPER on transformative practitioner-scientist partnerships and prevention infrastructure development. Am J Community Psychol (2011) 48(1–2):106–19. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9417-7

34. Wandersman A, Duffy J, Flaspohler P, Noonan R, Lubell K, Stillman L, et al. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: the interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am J Community Psychol (2008) 41(3–4):171–81. doi:10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z

35. McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, Jones P, Harshbarger C, Collins C, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev (2006) 18(4 Suppl A):59–73. doi:10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59

36. Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (2008) 47(Suppl 1):S40–6. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1

37. Collins CB Jr, Edwards AE, Jones PL, Kay L, Cox PJ, Puddy RW. A comparison of the interactive systems framework (ISF) for dissemination and implementation and the CDC division of HIV/AIDS prevention’s research-to-practice model for behavioral interventions. Am J Community Psychol (2012) 50(3–4):518–29. doi:10.1007/s10464-012-9525-7

38. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health (1999) 89(9):1322–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322

39. Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The transtheoretical model and stages of change. 4th ed. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2008). p. 97–121.

40. Napoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Stewart AL. Methods for translating evidence-based behavioral interventions for health-disparity communities. Prev Chronic Dis (2013) 10:E193. doi:10.5888/pcd10.130133

41. Little MA, Pokhrel P, Sussman S, Rohrbach LA. The process of adoption of evidence-based tobacco use prevention programs in California schools. Prev Sci (2015) 16(1):80–9. doi:10.1007/s11121-013-0457-8

42. Keshavarz N, Nutbeam D, Rowling L, Khavarpour F. Schools as social complex adaptive systems: a new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Soc Sci Med (2010) 70(10):1467–74. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.034

43. Butler H, Bowes G, Drew S, Glover S, Godfrey C, Patton G, et al. Harnessing complexity: taking advantage of context and relationships in dissemination of school-based interventions. Health Promot Pract (2010) 11(2):259–67. doi:10.1177/1524839907313723

44. Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernandez ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2016).

45. Texas Department of State Health Services. School Health Advisory Councils. (2015). Available from: https://www.dshs.state.tx.us/schoolhealth/sdhac.shtm

46. Gold RS. The potential of technology in health education: in recognition of the first HEDIR award. Int Electron J Health Educ (1998) 1:52–9.

47. Dixon BE, Gamache RE, Grannis SJ. Towards public health decision support: a systematic review of bidirectional communication approaches. J Am Med Inform Assoc (2013) 20(3):577–83. doi:10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001514

48. Peirson L, Catallo C, Chera S. The registry of knowledge translation methods and tools: a resource to support evidence-informed public health. Int J Public Health (2013) 58:493–500. doi:10.1007/s00038-013-0448-3

49. Petty RE, Barden J, Wheeler SC. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion: developing health promotions for sustained behavioral change. 2nd ed. In: Diclemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler M, editors. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2009). p. 185–214.

50. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall (1986).

51. McAlister A, Perry CL, Parcel GS. How individuals, environments, and health behaviors interact: social cognitive theory. 4th ed. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass (2008). p. 169–88.

52. Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH, Murray N, Cribb PW, Conroy J, Parcel GS. Dissemination and adoption of the child and adolescent trial for cardiovascular health (CATCH): a case study in Texas. J Public Health Manag Pract (2001) 7(2):90–100. doi:10.1097/00124784-200107020-00012

53. Paulussen T, Kok G, Schaalma H, Parcel GS. Diffusion of AIDS curricula among Dutch secondary school teachers. Health Educ Q (1995) 22(2):227–43. doi:10.1177/109019819502200210

54. Krueter M, Farrell DW, Olevitch L, Brennan LK, Rimer B. Tailoring Health Messages: Customizing Communication with Computer Technology. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1999).

Keywords: dissemination, evidence-based, intervention mapping, sexual health, adolescents

Citation: Peskin MF, Hernandez BF, Gabay EK, Cuccaro P, Li DH, Ratliff E, Reed-Hirsch K, Rivera Y, Johnson-Baker K, Emery ST and Shegog R (2017) Using Intervention Mapping for Program Design and Production of iCHAMPSS: An Online Decision Support System to Increase Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance of Evidence-Based Sexual Health Programs. Front. Public Health 5:203. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00203

Received: 29 March 2017; Accepted: 25 July 2017;

Published: 11 August 2017

Edited by:

Gerjo Kok, Maastricht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Julia V. Bailey, University College London, United KingdomJoanne Leerlooijer, HU University of Applied Sciences Utrecht, Netherlands

Copyright: © 2017 Peskin, Hernandez, Gabay, Cuccaro, Li, Ratliff, Reed-Hirsch, Rivera, Johnson-Baker, Emery and Shegog. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melissa F. Peskin, bWVsaXNzYS5mLnBlc2tpbkB1dGgudG1jLmVkdQ==

†Kelly Reed-Hirsch is no longer with Harris County Public Health though she was with that agency at the time the paper was written. She is currently at Panola College

Melissa F. Peskin

Melissa F. Peskin Belinda F. Hernandez

Belinda F. Hernandez Efrat K. Gabay

Efrat K. Gabay Paula Cuccaro1

Paula Cuccaro1 Dennis H. Li

Dennis H. Li Kelly Reed-Hirsch

Kelly Reed-Hirsch Yanneth Rivera

Yanneth Rivera Kimberly Johnson-Baker

Kimberly Johnson-Baker Ross Shegog

Ross Shegog