- 1Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

- 2South College, School of Physical Therapy, Knoxville, TN, USA

- 3Department of Health Promotion and Behavior, The University of Georgia College of Public Health, Athens, GA, USA

- 4Department of Health Promotion and Community Health Sciences, Texas A&M School of Public Health, College Station, TX, USA

A commentary on

Background

Each year, approximately 30% of adults aged 65 years and older fall (1), resulting in significant morbidity, mortality, and decreased quality of life (2, 3). This problem is projected to increase as baby boomers age. Research confirms fall risk detection and evidence-based prevention programs offered in clinical and community settings that serve an aging population are effective at reducing the number of falls experienced (4, 5). To expand the reach of these services beyond the aging services network, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Administration for Community Living (ACL), and other funders are supporting opportunities for public health entities to become leaders in fall-prevention initiatives. The goal is to expand the infrastructure and entry points in both clinical and community settings to better meet the challenges of older adult fall risk management.

However, integrated community-clinical efforts integral to fall risk management are relatively new endeavors for State Departments of Health (DOH) (6). To be successful, DOH must recruit and engage a set of partners representing diverse sectors. Multi-sectorial collaborations are important for sustained adoption of evidence-based fall risk management practices. Such practices ensure the availability of a continuum of prevention and referral services for older adults.

This Commentary builds upon previous work from the State Falls Prevention Project (SFPP), a project funded by the CDC, in which DOH in New York, Colorado, and Oregon were charged with implementing clinical and community fall-prevention programs in specific geographic areas (6, 7). Now that the 5-year initiative has concluded, this Commentary reflects viewpoints of the SFPP Falls Evaluation and Technical Assistance (FETA) Team as guidance statements for future delivery of multi-level evidence-based fall-prevention interventions in the United States.

State Falls Prevention Project

During the course of the SFPP, it became apparent the most effective implementation role for the DOH was to identify and connect health-care systems, community providers, and older adults to needed resources. Each DOH facilitated the implementation of three evidence-based fall-prevention programs, which were selected because of their ability to minimize risk of falling by improving balance, increasing strength, and providing education: (1) Tai Chi: moving for better balance; (2) stepping on; and (3) the Otago Exercise Program. Each state also developed strategies to increase clinical engagement in fall risk management through use of the CDC STEADI (STopping Elderly Accidents Deaths and Injuries) tool kit. Through this process, each DOH faced similar implementation challenges, which generated better appreciation of lessons learned from this experience and effective solutions.

Challenges

During the first pilot year, the DOHs deployed the strategy of: (1) engaging with health-care providers through a traditional academic detailing model (i.e., provide lunch and a brief training session) to facilitate adoption of evidence-based fall risk management practices (8) and (2) working with community providers to increase access to community evidence-based fall-prevention programs (9–12). Several challenges were quickly realized by the entire SFFP team including:

1. Changing physician practice is a monumental task requiring the development of meaningful value propositions for each practice and ongoing relationship building, which could not be accomplished with a brief “lunch and learn” session.

2. Health-care organizations and providers (e.g., physicians, nurses, and physical therapists) typically have limited knowledge about value and availability of evidence-based fall-prevention programs available in the community.

3. There are many competing health-care and clinic efficiency initiatives that make it difficult for any new project to be viewed as a priority.

4. Each health-care system is unique. What motivates one system to embed fall risk management practices [i.e., modify Electronic Medical Records (EHR), adopt STEADI] will not necessarily be valued or motivating to other health-care systems in the same region.

5. There is widespread dissemination of evidence-based programs; however, a lack of program availability exists in many communities; few communities have a central source to provide a comprehensive, up-to-date list of available programs; this makes it challenging to schedule a patient in a timely manner.

6. Referral systems are fractured. No internal systems exist within a health-care system to refer a patient to a community-based program. The converse was true – no systems existed to connect an older adult identified as a fall risk by a community provider to a health-care provider.

7. There is a supply–demand dilemma – it is a challenge to build referrals from clinics to community programs (demand) while at the same time insuring you have enough programs in the community (supply).

8. It is important to identify potential partners interested in decreasing health-care costs and achieving better outcomes. However, not all partners will be ready to implement evidence-based programs as a cost-reducing measure.

9. Once a clinical-community linkage is created, long term sustainability of the linkage may be challenging due to personnel changes, program availability, and competing demands.

Solutions and Lessons Learned

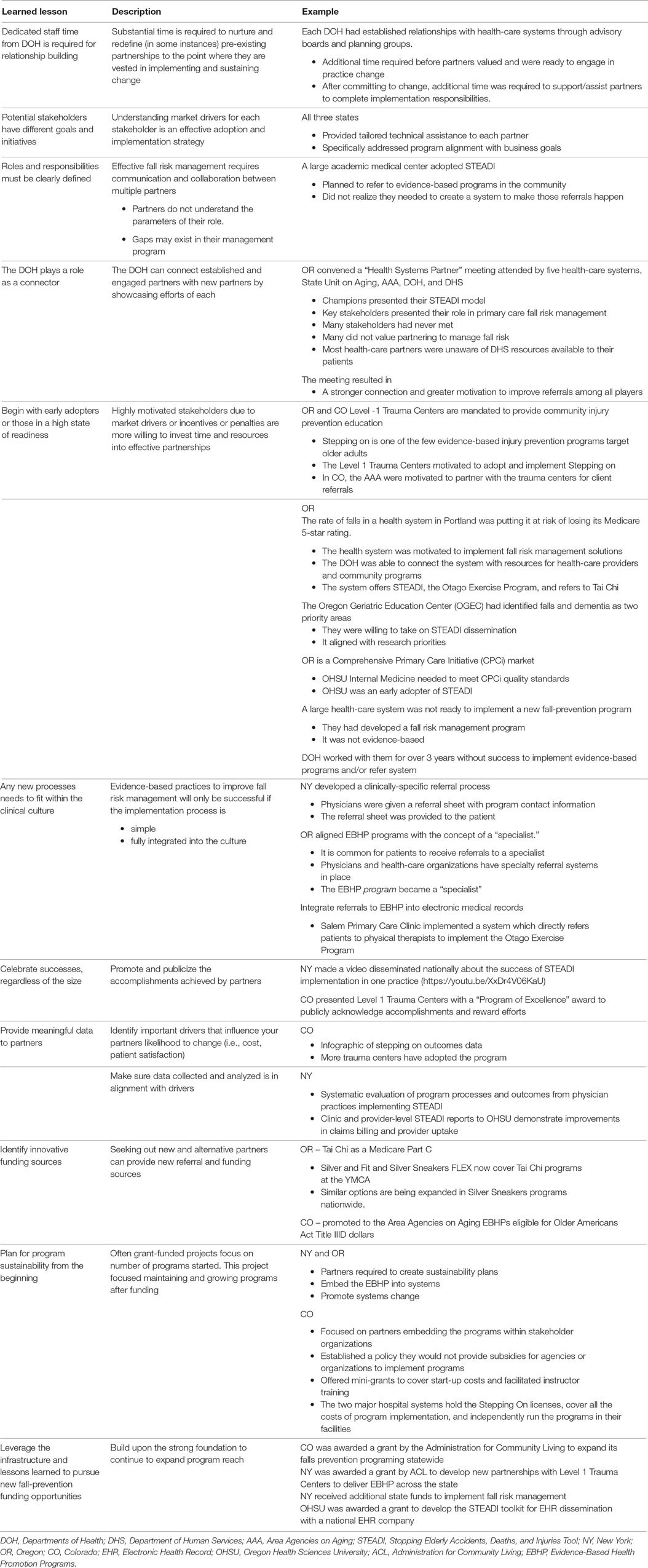

Reflecting on these challenges, the SFPP FETA Team, in collaboration with funders and grantees, gained perspectives about effective solutions. The role of the DOH as a “connector and convener” seemed the most effective model. As connector, the DOH educated and engaged stakeholders from health care and community settings about respective roles in fall-prevention efforts. As convener, the DOH brought stakeholders together to identify problems, discuss feasible strategies and solutions, and create state-specific systems to advance fall prevention. This strategy ultimately created stakeholder buy-in and ownership while developing potentially sustainable solutions to these challenges (6, 13). Table 1 presents lessons learned (with examples) from this project.

Table 1. Lessons learned, with examples, from the State-driven Fall-Prevention Project from New York (NY), Colorado (CO), and Oregon (OR) Departments of Health (DOH).

The challenges and solutions inherent in implementation of fall-prevention initiatives served to define effective roles for DOH in these three states. Each DOH developed its own unique role in fall prevention; however, all the successful initiatives relied on DOH helping organizations identify the problem of falls and guiding them toward evidence-based solutions.

As federal and state agencies continue to fund delivery infrastructures to bring programs “to scale,” more effort should be given to defining the roles of each partner/stakeholder and connecting individual agencies to create/support a continuum of fall-prevention services.

Author Contributions

All the authors were involved as evaluators of this 5-year initiative. All the authors wrote the manuscript and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the leadership and guidance of CDC personnel throughout this SFPP project. More specifically, the authors acknowledge Margaret Kaniewski, Judy Stevens, Erin Parker, and Robin Lee. The authors also acknowledge the hard work and ongoing dedication of the Colorado, New York, and Oregon State Departments of Health. Under the leadership of Sallie Thoreson, Michael Bauer, Lisa Shields, and David Dowler, respectively, these public health teams were able to confront and overcome challenges to realize amazing successes related to fall prevention in their states.

Funding

This research was supported under the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Centers Program, funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under Cooperative Agreement 1U48-DP005017 at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention and Cooperative Agreement 1U48 DP001924 at the Texas A&M Health Science Center School of Public Health Center for Community Health Development.

References

1. Tinetti ME, Williams CS. The effect of falls and fall injuries on functioning in community-dwelling older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (1998) 53(2):M112–9. doi:10.1093/gerona/53A.2.M112

2. Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev (2006) 12(5):290–5. doi:10.1136/ip.2005.011015

3. Alexander BH, Rivara FP, Wolf ME. The cost and frequency of hospitalization for fall-related injuries in older adults. Am J Public Health (1992) 82(7):1020–3. doi:10.2105/AJPH.82.7.1020

4. Stevens JA, Burns ER. A CDC Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 3rd ed. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2015).

5. Carande-Kulis V, Stevens JA, Florence CS, Beattie BL, Arias I. A cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions. J Safety Res (2015) 52:65–70. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2014.12.007

6. Thoreson SR, Shields LM, Dowler DW, Bauer MJ. Public health system perspective on implementation of evidence-based fall prevention strategies for older adults. Front Public Health (2015) 2:119. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00191

7. Kaniewski M, Stevens JA, Parker EM, Lee R. An introduction to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s efforts to prevent older adult falls. Front Public Health (2015) 2:119. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00119

8. Schuster RJ, Cherry CO, Smith ML. The clinician engagement and education (CEE) session: modernizing “academic detailing”. Am J Med Qual (2013) 28(6):533–5. doi:10.1177/1062860613491976

9. Shubert TE, Smith ML, Ory MG, Clarke C, Bomberger SA, Roberts E, et al. Translation of The Otago Exercise Program for adoption and implementation in the United States. Front Public Health (2015) 2:119. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00152

10. Smith ML, Stevens JA, Ehrenreich H, Wilson AD, Schuster RJ, O’Brien Cherry C, et al. Healthcare providers’ perceptions and self-reported fall prevention practices: findings from a large New York health system. Front Public Health (2015) 2:119. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.00017

11. Ory MG, Smith ML, Jiang L, Lee R, Chen S, Wilson AD, et al. Fall prevention in community settings: results from implementing stepping on in three states. Front Public Health (2015) 2:119. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00232

12. Ory MG, Smith ML, Parker EM, Jiang L, Chen S, Wilson AD, et al. Fall prevention in community settings: results from implementing Tai Chi: moving for better balance in three states. Front Public Health (2015) 2:119. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00258

Keywords: state health departments, evidence-based strategy, older adults, fall prevention, health promotion

Citation: Shubert TE, Smith ML, Schneider EC, Wilson AD and Ory MG (2016) Commentary: Public Health System Perspective on Implementation of Evidence-Based Fall-Prevention Strategies for Older Adults. Front. Public Health 4:252. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00252

Received: 22 August 2016; Accepted: 26 October 2016;

Published: 16 November 2016

Edited by:

Renae L. Smith-Ray, Walgreens, USAReviewed by:

Jo Ann Shoup, Kaiser Permanente, USACopyright: © 2016 Shubert, Smith, Schneider, Wilson and Ory. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tiffany E. Shubert, dGlmZmFueV9zaHViZXJ0QG1lZC51bmMuZWR1

Tiffany E. Shubert

Tiffany E. Shubert Matthew Lee Smith

Matthew Lee Smith Ellen C. Schneider

Ellen C. Schneider Ashley D. Wilson4

Ashley D. Wilson4 Marcia G. Ory

Marcia G. Ory