- 1Department of Neuroscience, University of Padova, Padua, Italy

- 2Padova Neuroscience Center, University of Padova, Padua, Italy

- 3Eating Disorder Unit, Casa di Cura “Villa Margherita” – KOS Group, Vicenza, Italy

- 4Eating Disorders Unit, Casa di Cura Villa dei Pini – KOS Group, Florence, Italy

- 5Eating Disorders Unit, Casa di Cura Villa Armonia – KOS Group, Rome, Italy

- 6Eating Disorders Unit, Casa di Cura Ville di Nozzano – KOS Group, Lucca, Italy

Introduction: Eating disorders (EDs) are complex and often linked to traumatic childhood experiences. While childhood trauma is known to increase the risk of EDs, the role of loneliness remains underexplored. This study investigates whether loneliness mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and ED symptoms.

Methods: A total of 230 individuals with EDs completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, and the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire. Mediation analysis was conducted to assess if loneliness mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and ED severity.

Results: Childhood trauma significantly predicted higher levels of loneliness (p < 0.001), which was associated with more severe ED symptoms (p = 0.001), with age and BMI as covariates. Mediation analysis showed loneliness partially mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and ED severity (indirect effect b = 0.003, 95%CI [0.001, 0.006]).

Conclusion: Loneliness partially mediates childhood trauma and ED symptoms, highlighting the need to address loneliness in treatment to mitigate the impact of childhood trauma on ED severity. These findings suggest the possible role of social connection-focused interventions in ED care and contribute to understanding the mechanisms underlying the development of EDs. Future research should explore additional mediators and moderators to provide a more comprehensive perspective.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs), which encompass conditions such as anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge-eating disorder (BED), represent a significant public health concern due to their profound physical, psychological, and social consequences (1–3). These disorders are marked by persistent disturbances in eating behavior, accompanied by distressing thoughts and emotions related to food, body weight, and shape (1). In line with the biopsychosocial model, this complex etiology underscores the importance of considering social and environmental factors, alongside biological and psychological influences, in understanding and addressing EDs (4). Among environmental factors, childhood traumas have emerged as a critical area of focus, given their long-lasting impact on mental health (5, 6). Recent studies report varying prevalence rates of EDs, with lifetime prevalence ranging from 2.2% for men to 8.4% for women (7, 8). These rates vary by region, with higher point prevalence observed in America (4.6%) and Asia (3.5%) compared to Europe (2.2%), suggesting that eating disorders are highly prevalent worldwide, particularly among women, and that the incidence of these disorders has been increasing over time. The distribution of ED varies widely, with AN typically being more prevalent in clinical settings, particularly in inpatient facilities, while BN and BED are often more common in outpatient or community samples (9). The prevalence of each diagnosis is also influenced by factors such as gender, age, and geographical region (10).

Traumatic childhood experiences, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, as well as neglect and household dysfunction, have been extensively documented as significant risk factors for the development of various psychological disorders (11, 12). These early adversities disrupt the normal developmental trajectory, leading to maladaptive coping mechanisms and alterations in neurobiological stress response systems (13). Research has consistently shown that individuals with a history of childhood trauma are at a heightened risk for developing eating disorders, as these individuals may turn to disordered eating behaviors as a means to exert control, manage negative emotions, or dissociate from traumatic memories (14). Recently, various studies have suggested the possible presence of an echophenotype in individuals with eating disorders who have a history of trauma, indicating more severe clinical conditions and physical changes that constitute a different and specific manifestation of the disorder (15, 16).

Social support, a key element in the biopsychosocial model, plays a crucial role in mental health by providing emotional resources that help individuals manage stress and adversity (17). Supportive relationships can buffer the impact of trauma, fostering resilience and promoting healthier coping strategies (18, 19). Conversely, a lack of social support or experiences of social isolation can heighten vulnerability to psychological distress, intensifying the risk of developing or worsening symptoms of mental health conditions, including eating disorders (18, 20).

Loneliness and social isolation also play critical roles in eating disorders across diagnostic categories. Social isolation, defined as a lack of meaningful social interactions, is a frequent experience among individuals with eating disorders and can heighten the sense of disconnection from others (21). This is particularly relevant given that social withdrawal is common in ED populations, where shame and stigma surrounding eating behaviors may lead to avoidance of social situations (22, 23). Such isolation exacerbates feelings of loneliness—a perceived deficit in social connections—and has been associated with the maintenance and severity of eating disorder symptoms across various diagnoses, including AN, BN, and BED (24–26). In addition to the effects of childhood trauma, the role of loneliness as a mediation feature has gained increasing attention in the context of mental health outcomes, in different disorders and different contexts (27–29). Individuals who have experienced childhood trauma often report higher levels of loneliness, stemming from difficulties in forming and maintaining secure attachments and trusting relationships (30). This chronic sense of isolation and social disconnection can exacerbate the psychological distress associated with eating disorders, creating a vicious cycle that reinforces maladaptive eating behaviors (31). Furthermore, loneliness has recently been identified as a potential factor that may contribute to the worsening of physical conditions in people with eating disorders, calling for further investigations (24).

The intersection of childhood trauma, loneliness, and eating disorder psychopathology represents a compelling area for investigation. While the link between childhood trauma and EDs has been well-established (32), the mediating role of loneliness in this relationship remains underexplored. Understanding how loneliness mediates this relationship can provide crucial insights into the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the development and persistence of eating disorders. This knowledge can inform the design of targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at alleviating loneliness, thus potentially mitigating the impact of childhood trauma on the symptoms of eating disorders.

This study aims to explore the mediating effect of loneliness in the relationship between traumatic childhood experiences and eating disorder psychopathology. By employing a mediation analysis approach, we seek to elucidate the pathways through which early adverse experiences influence EDs symptoms, highlighting the critical role of loneliness. Our findings are expected to contribute to the growing body of literature regarding the etiology of eating disorders and offer practical implications for enhancing treatment strategies to address loneliness in individuals with a history of childhood trauma.

Methods

Participants

The study involved 230 individuals diagnosed with eating disorders, recruited from four national clinics, specialized in the treatment of these disorders, at the onset of their inpatient treatment. Diagnoses were established by experienced eating disorder clinicians using the semi-structured clinical interview based on DSM-5 criteria, which is standard in clinical practice. The high proportion of AN participants is due to the recruitment setting within inpatient clinics. The exclusion criteria were the presence of a severe psychiatric acute comorbidity like psychosis or mania, or the presence of cognitive deficits. All participants identified as cisgender, with the majority being white (95.9%). All participants filled out a written informed consent to participate at the study.

Measures

Data were collected within one week of admission for the EDs group as part of routine service evaluation. The survey package included the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), the revised University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (UCLA), and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). All three instruments demonstrated good internal consistency (α > 0.80).

The EDE-Q is a 28-item self-report measure designed to assess the severity of eating disorder psychopathology (33). Participants respond using a 7-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms. The EDE-Q provides a global score and four subscales: restraint, eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns.

The UCLA Loneliness Scale is a 20-item questionnaire that evaluates subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation (34). Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting elevated levels of loneliness. This scale is widely used and validated for assessing loneliness in various populations.

The CTQ is a retrospective self-report inventory that measures the extent of traumatic experiences during childhood (35). It includes 28 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale, encompassing a total score and five subscales: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Higher scores indicate greater levels of reported childhood trauma.

Statistical plan

The statistical analysis involved a comprehensive examination of the sample, including descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and rates for the prevalence of traumatic experiences based on the CTQ. Mediation analysis was conducted using the SPSS PROCESS macro-extension (version 3.5), specifically Model 4 (36). In this analysis, the CTQ total score was utilized as the independent variable, with the UCLA Loneliness Scale score as the mediator and the EDE-Q total score as the dependent variable. To assess the mediation effect, bootstrapping with 5,000 samples was performed to estimate the indirect effects, with bias-corrected confidence intervals set at 95%. Bootstrapping involves repeatedly sampling from the data to calculate indirect effects and their confidence intervals, providing a more accurate and reliable estimate by simulating thousands of potential scenarios (37). The mediation model was evaluated including age and BMI as covariates. Additionally, the Sobel test was employed as a confirmatory analysis to validate the overall indirect effect. The Sobel test is a traditional method to check whether a mediator significantly explains the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, offering a straightforward calculation of statistical significance (38). Statistical significance was determined at an alpha level of p < 0.05 for all analyses, executed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).

Results

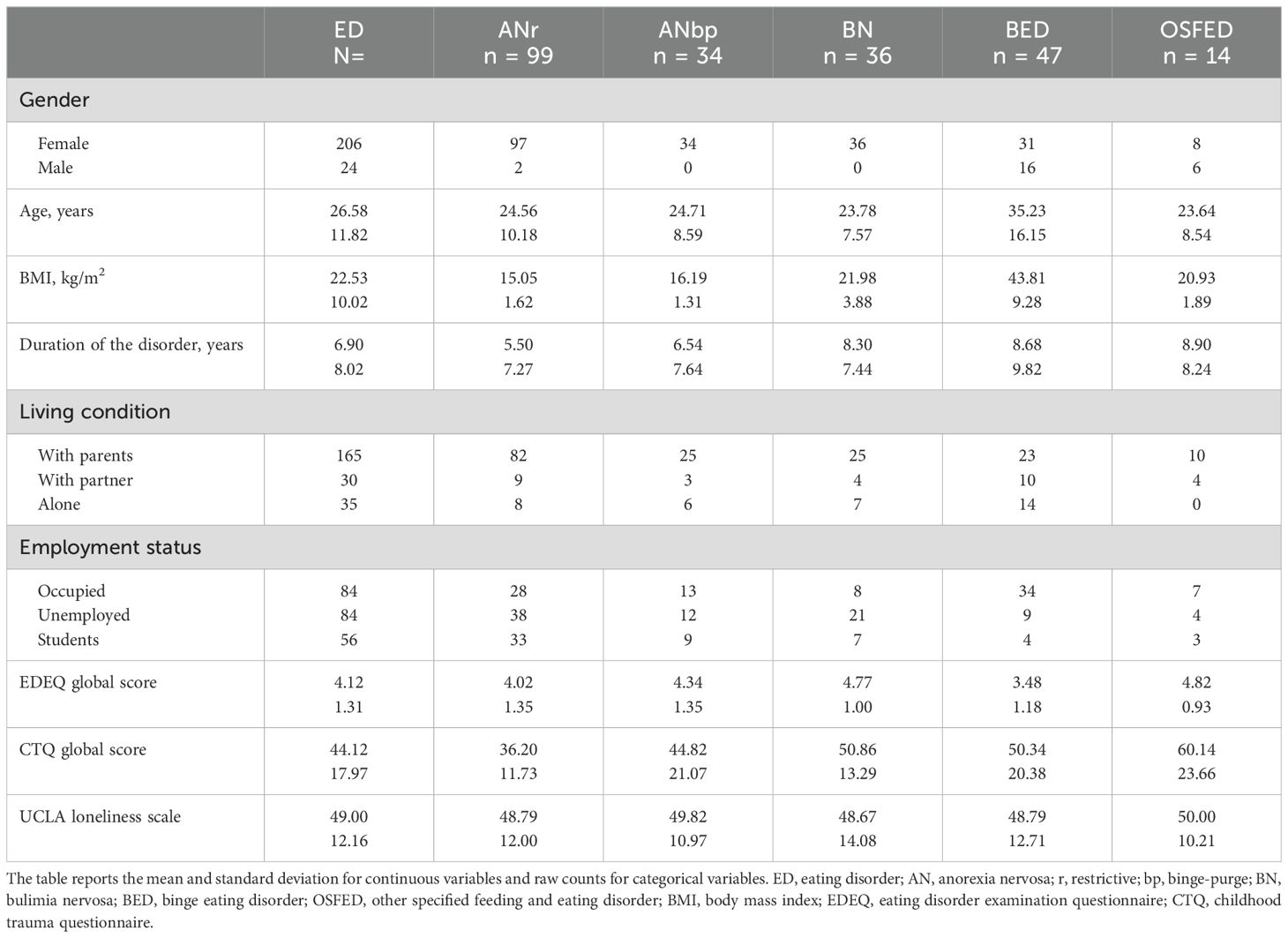

The sample consisted of 206 women (89.4%) and 24 men (10.6%). The mean age was 26.58 ± 11.82 years, with a mean BMI of 22.53 ± 12.02 kg/m2, and an average duration of the disorder of 6.90 ± 8.02 years. Diagnoses within the sample included 99 individuals with restrictive anorexia nervosa (42.8%), 34 with binge-purge anorexia nervosa (14.7%), 36 with bulimia nervosa (15.3%), 47 with binge eating disorder (20.0%), and 14 with other specified feeding and eating disorders (6.2%). Most participants lived with their parents (n = 165, 71.7%), while fewer lived alone (n = 35, 15.2%) or with a partner (n = 30, 13.0%). Regarding employment status, the majority reported having a stable occupation (n = 84, 36.5%), a significant proportion were unemployed (n = 84, 36.5%), and 56 were students (24.3%). EDEQ global score was 4.12 ± 1.31, CTQ global score was 44.12 ± 17.97, and UCLA Loneliness score was 49.00 ± 12.16. See Table 1 for details.

Mediation analyses

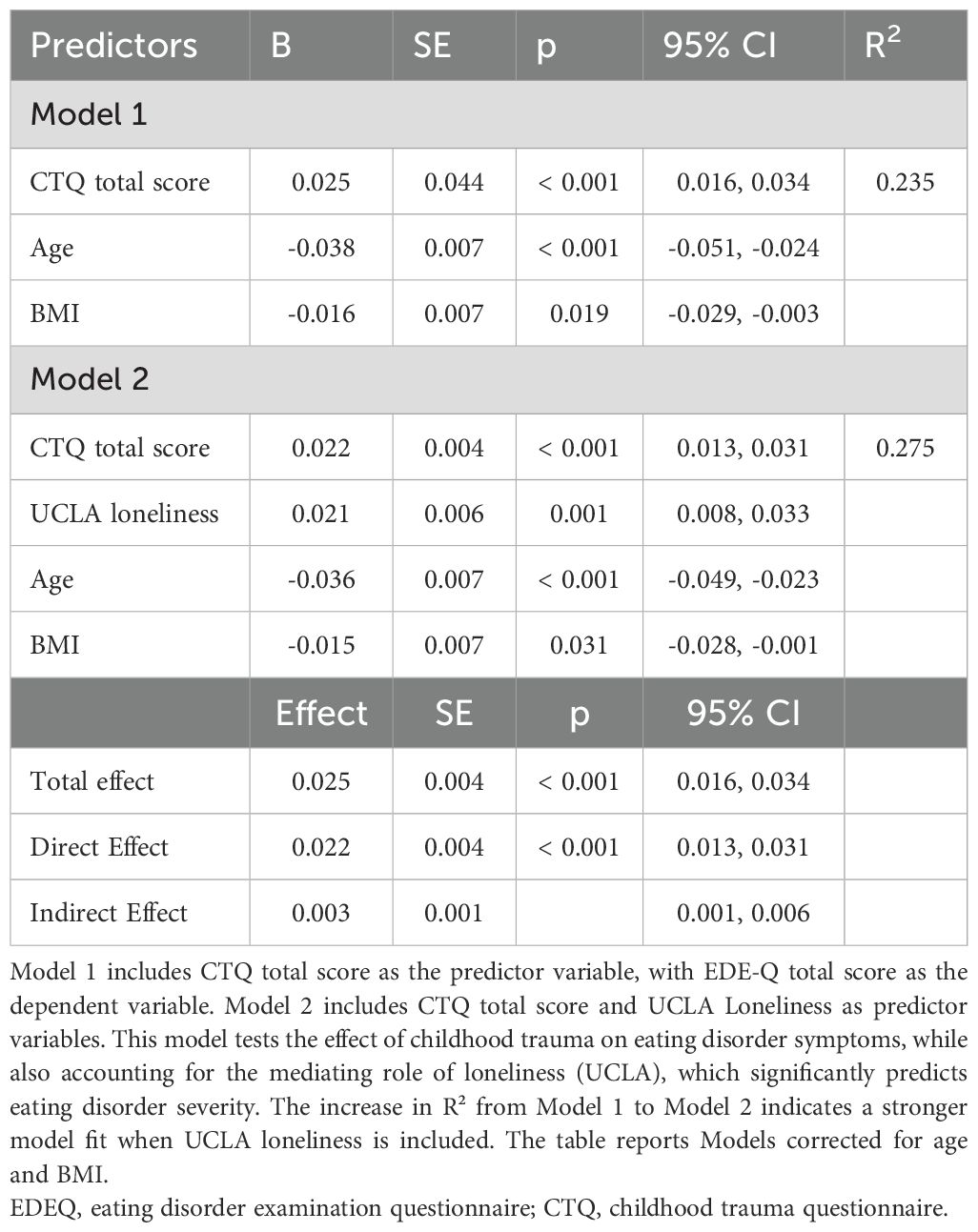

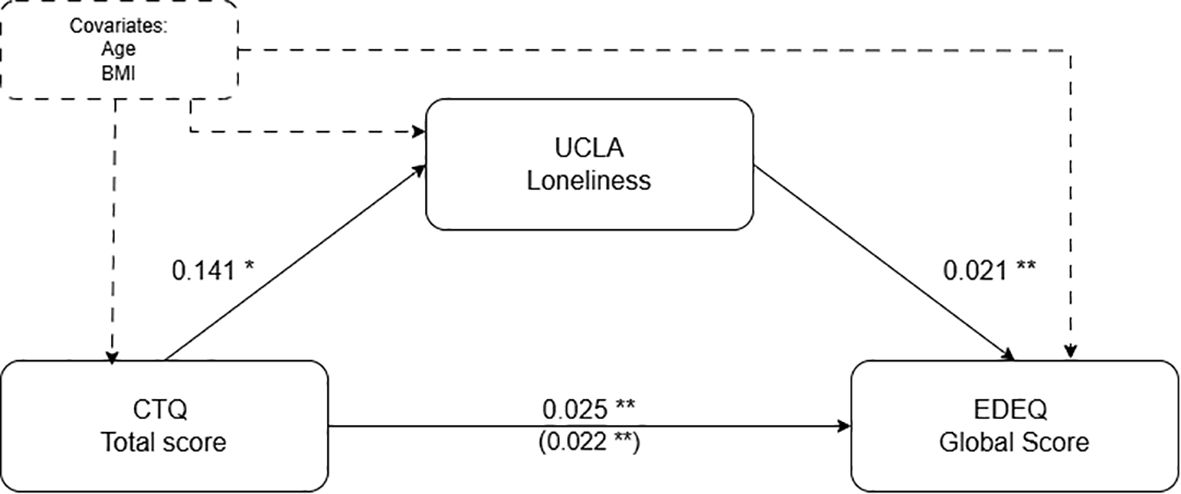

The analysis indicated that the CTQ total score significantly predicted UCLA, b = 0.141, p < 0.001, suggesting that higher levels of childhood trauma are associated with higher UCLA Loneliness scores. UCLA, in turn, significantly predicted EDEQ global score, b = 0.021, p = 0.001, indicating that greater UCLA Loneliness scores are related to more severe eating disorder symptoms.

The total effect of CTQ total score on EDEQ global score was significant, b = 0.025, p < 0.001. The direct effect of CTQ total score on EDEQ global score, after accounting for UCLA, was also significant, b = 0.022, p < 0.001. The indirect effect of CTQ total score on EDEQ global score through UCLA Loneliness was b = 0.003, with a 95% bootstrap confidence interval of [0.001, 0.006], which does not include zero, indicating a significant mediation effect. The completely standardized indirect effect was b = 0.040 (95% CI [0.009, 0.082]), further confirming that UCLA Loneliness significantly mediates the relationship between total childhood trauma and eating disorder symptoms. These results suggest that the effect of childhood trauma on eating disorders is partially mediated by UCLA. See Figure 1 for the mediation analysis graphical representation and Table 2 for details.

Figure 1. Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between childhood trauma (CTQ total score) and eating disorder psychopathology (EDEQ global score) as mediated by UCLA Loneliness, corrected for age and BMI. The regression coefficient of the mediation is in parentheses. *p < 0.01; **p <= 0.001.

Sobel test corroborated the results of the mediation analysis showing a significant mediation with Sobel test statistic = 2.355 and p = 0.018.

Discussion

The present study explored the mediating effect of loneliness on the relationship between traumatic childhood experiences and eating disorder psychopathology. The findings reveal that loneliness significantly mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and the severity of eating disorder symptoms. This has profound clinical implications, as it provides insights into the underlying mechanisms that contribute to the development and persistence of eating disorders and suggests avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions. Previous research has established a link between childhood trauma and eating disorders (4, 12), but the mediating role of loneliness has been underexplored. Our findings extend this understanding by demonstrating that loneliness significantly mediates this relationship.

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature by examining the mediating role of loneliness, providing a more nuanced understanding of how early adverse experiences can lead to disordered eating behaviors through the intermediary of social isolation. Indeed, loneliness is pointed out as a crucial element in the pathway from childhood trauma to eating disorder symptoms. This finding aligns with the theoretical framework that traumatic childhood experiences disrupt normal developmental trajectories, leading to maladaptive coping mechanisms and alterations in neurobiological stress response systems (39, 40). From a clinical perspective, this underscores the importance of addressing loneliness in therapeutic settings to disrupt this pathway. Otherwise, interventions might be not useful for the improvement of patients’ health.

Moreover, the mediating role of loneliness suggests that interventions aimed at reducing feelings of isolation and enhancing social connections could be effective in treating individuals with eating disorders who have a history of childhood trauma. In this perspective, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT), which focus on improving social skills and building meaningful relationships, may be particularly beneficial (41–44). Also, specific remediation therapy interventions like Cognitive Remediation and Emotional Skills Training (CREST) might be considered an effective add-on treatment with these specific goals due to their efficacy in implementing specific interpersonal features (45).

The results corroborate recent studies that have identified loneliness as a significant factor in the worsening of physical and psychological conditions, including eating disorders (24, 31, 46). By empirically demonstrating the mediating role of loneliness, this study reinforces the importance of social connections in mental health and eating disorder psychopathology specifically (47, 48). We found evidence of partial mediation, supporting the idea that childhood maltreatment and loneliness have both combined and independent effects. However, the partial nature of these relationships suggests opportunities for future research to explore additional mediators and moderators. Factors such as resilience, social support, and coping strategies could be examined to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay between childhood trauma, loneliness, and eating disorders. Longitudinal studies could also investigate the temporal dynamics of these relationships, offering further insights into causality and optimal intervention timing.

Finally, the findings emphasize the need for personalized treatment plans that take into account the patient’s history of childhood trauma and current levels of loneliness (49). Clinicians should consider incorporating assessments for loneliness and trauma history into their diagnostic process to identify patients who may benefit from targeted interventions aimed at improving social connections. This tailored approach can lead to more effective treatment outcomes. Indeed, there is growing evidence that both loneliness and traumatic events have specific disruptive effects on life trajectories, increasing both psychological and physical symptoms (50). From a preventive perspective, early interventions targeting loneliness in children who have experienced trauma have been reported to be effective in reducing the long-lasting negative effects on physical and mental health (51–53). This approach could also reduce the risk of developing eating disorders later in life (54, 55). School-based programs and family interventions that promote healthy attachment and social support could play a crucial role in preventing the onset of eating disorders among at-risk populations (55–57).

This study prioritized mediation analysis to explore the mechanisms underlying the relationships between childhood trauma, loneliness, and ED symptoms. The decision not to examine moderation was guided by our aim to identify potential indirect pathways rather than the interaction effects or conditions that might influence these relationships (58). However, investigating moderation could offer valuable insights into how individual differences or contextual factors, such as gender, cultural background, or severity of symptoms, might shape these associations (59)-all aspects that ED research needs (60). Future research should consider incorporating moderation analyses to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complexity of these interactions.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes any definitive conclusions about the causal relationships between childhood trauma, loneliness, and eating disorder symptoms. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish the temporal sequence of these variables. Second, the reliance on self-report measures may introduce response biases, such as social desirability or recall biases, which could affect the accuracy of the data. Third, the sample predominantly consisted of individuals identifying as cisgender and white, limiting the generalizability of the findings to more diverse populations. Additionally, the mixed sample, which includes individuals with various eating disorder diagnoses, may represent a limitation, as these disorders differ significantly in their phenotypic expression and in their associations with childhood trauma—particularly as bulimic variants are more frequently associated with histories of physical and sexual abuse. Moreover, the higher representation of individuals with anorexia nervosa in our sample, likely due to the enrollment criteria of inpatient facilities, may limit the generalizability of the findings to those with other eating disorder diagnoses, as inpatient settings tend to prioritize patients with more severe forms of AN. Furthermore, the inclusion of male participants could introduce a confounding variable, as gender may affect the presentation and correlates of eating disorder symptoms. Moreover, while loneliness was a central variable in our study, we did not assess depressive symptoms, which may be associated with loneliness and could provide a broader understanding of its role in eating disorders; this is a key limitation and an area for further exploration in future studies. Finally, the study did not account for other potential mediators or moderators that could influence the relationship between childhood trauma and eating disorders, such as genetic factors, personality traits, or other environmental influences.

Conclusion

This study underscores the significant mediating role of loneliness in the relationship between traumatic childhood experiences and eating disorder psychopathology. These findings highlight the importance of addressing loneliness in therapeutic interventions to mitigate the impact of childhood trauma on eating disorder symptoms. By advancing the understanding of the underlying mechanisms and suggesting targeted therapeutic approaches, this study contributes to the development of more effective and personalized treatment strategies. Additionally, it fills a critical gap in the literature and sets the stage for future research to further elucidate the complex relationships between childhood trauma, loneliness, and eating disorders.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Vicenza Ethics Committee for Clinical Practice. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

PM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. BM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. FC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. LM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. PT: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Open Access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Padova | University of Padua, Open Science Committee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association and others. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5{\textregistered}). Am Psychiatr Assoc. (2013). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

2. Meneguzzo P, Todisco P, Calonaci S, Mancini C, Dal Brun D, Collantoni E, et al. Health-related quality of life assessment in eating disorders: adjustment and validation of a specific scale with the inclusion of an interpersonal domain. Eating Weight Disord. (2020) 26:2251–62. doi: 10.1007/s40519-020-01081-5

3. Forbush KT, Hagan KE, Kite BA, Chapa DAN, Bohrer BK, Gould SR. Understanding eating disorders within internalizing psychopathology: A novel transdiagnostic, hierarchical-dimensional model. Compr Psychiatry. (2017) 79:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.06.009

4. Culbert KM, Racine SE, Klump KL. Research Review: What we have learned about the causes of eating disorders - A synthesis of sociocultural, psychological, and biological research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2015) 56:1141–64. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12441

5. Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Pellegrino F, Ruzzi V, Patriciello G, Marone L, et al. The association between childhood maltreatment and eating disorder psychopathology: A mixed-model investigation. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 61:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.08.002

6. Meneguzzo P, Cazzola C, Castegnaro R, Buscaglia F, Bucci E, Pillan A, et al. Associations between trauma, early maladaptive schemas, personality traits, and clinical severity in eating disorder patients: A clinical presentation and mediation analysis. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:661924. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661924

7. Qian J, Wu Y, Liu F, Zhu Y, Jin H, Zhang H, et al. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eating Weight Disord. (2022) 27:415–28. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01162-z

8. Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: A systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 109:1402–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

9. Smink FRE, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2012) 14:406–14. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

10. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. (2007) 61:348–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040

11. McKay MT, Cannon M, Chambers D, Conroy RM, Coughlan H, Dodd P, et al. Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2021) 143:189–205. doi: 10.1111/acps.13268

12. Hogg B, Gardoki-Souto I, Valiente-Gómez A, Rosa AR, Fortea L, Radua J, et al. Psychological trauma as a transdiagnostic risk factor for mental disorder: an umbrella meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2023) 273:397–410. doi: 10.1007/s00406-022-01495-5

13. Murphy F, Nasa A, Cullinane D, Raajakesary K, Gazzaz A, Sooknarine V, et al. Childhood trauma, the HPA axis and psychiatric illnesses: a targeted literature synthesis. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:748372. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.748372

14. Levine MP, Smolak L. Paradigm clash in the field of eating disorders: a critical examination of the biopsychiatric model from a sociocultural perspective. Adv Eating Disord. (2014) 2:158–70. doi: 10.1080/21662630.2013.839202

15. Meneguzzo P, Mancini C, Terlizzi S, Sales C, Francesconi MF, Todisco P. Urinary free cortisol and childhood maltreatments in eating disorder patients: New evidence for an ecophenotype subgroup. Eur Eating Disord Rev. (2022) 30(4):364–72. doi: 10.1002/erv.2896

16. Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Ruzzi V, Pellegrino F, Patriciello G, Barone E, et al. Emotional traumatic experiences significantly contribute to identify a maltreated ecophenotype sub-group in eating disorders: Experimental evidence. Eur eating Disord Rev. (2021) 29:269–80. doi: 10.1002/erv.2818

17. Phillipou A, Musić S, Lee Rossell S. A biopsychosocial proposal to progress the field of anorexia nervosa. Aust New Z J Psychiatry. (2019) 53:1145–7. doi: 10.1177/0004867419849487

18. Ramjan LM, Smith BW, Miskovic-Wheatley J, Pathrose SP, Hay PJ. Social support for young people with eating disorders—An integrative review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2024) 33(6):1615–36. doi: 10.1111/inm.13363

19. Schirk DK, Lehman EB, Perry AN, Ornstein RM, McCall-Hosenfeld JS. The impact of social support on the risk of eating disorders in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Int J Womens Health. (2015) 7:919–31. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S85359

20. Makri E, Michopoulos I, Gonidakis F. Investigation of loneliness and social support in patients with eating disorders: A case-control study. Psychiatry Int. (2022) 3:142–57. doi: 10.3390/psychiatryint3020012

21. Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. (2010) 40:218–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

22. Patel K, Tchanturia K, Harrison A. An exploration of social functioning in young people with eating disorders: A qualitative study. PloS One. (2016) 11:e0159910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159910

23. Rotenberg KJ, Bharathi C, Davies H, Finch T. Bulimic symptoms and the social withdrawal syndrome. Eat Behav. (2013) 14:281–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.05.003

24. Meneguzzo P, Terlizzi S, Maggi L, Todisco P. The loneliness factor in eating disorders: Implications for psychopathology and biological signatures. Compr Psychiatry. (2024) 132:152493. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2024.152493

25. McNamara N, Wakefield JRH, Cruwys T, Potter A, Jones BA, McDevitt S. The link between family identification, loneliness, and symptom severity in people with eating disorders. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. (2022) 32:949–62. doi: 10.1002/casp.2606

26. Marffy MJ, Fox J, Williams M. An exploration of the relationship between loneliness, the severity of eating disorder-related symptoms and the experience of the ‘anorexic voice.’. Psychol Psychotherapy: Theory Res Pract. (2024) 97:122–37. doi: 10.1111/papt.12502

27. Shevlin M, McElroy E, Murphy J. Loneliness mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and adult psychopathology: evidence from the adult psychiatric morbidity survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2015) 50:591–601. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0951-8

28. Hyland P, Shevlin M, Cloitre M, Karatzias T, Vallières F, McGinty G, et al. Quality not quantity: loneliness subtypes, psychological trauma, and mental health in the US adult population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2019) 54:1089–99. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1597-8

29. Southward MW, Christensen KA, Fettich KC, Weissman J, Berona J, Chen EY. Loneliness mediates the relationship between emotion dysregulation and bulimia nervosa/binge eating disorder psychopathology in a clinical sample. Eating Weight Disorders-Studies Anorexia Bulimia Obes. (2014) 19:509–13. doi: 10.1007/s40519-013-0083-2

30. Breidenstine AS, Bailey LO, Zeanah CH, Larrieu JA. Attachment and trauma in early childhood: A review. Assess Trauma Youths. (2016), 125–70.

32. Barone E, Carfagno M, Cascino G, Landolfi L, Colangelo G, Della Rocca B, et al. Childhood maltreatment, alexithymia and eating disorder psychopathology: a mediation model. Child Abuse Negl. (2023) 146:106496. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106496

33. Aardoom JJ, Dingemans AE, Slof Op’t Landt MCT, Van Furth EF. Norms and discriminative validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). Eat Behav. (2012) 13:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.09.002

34. Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1980) 39:472. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

35. Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. (2003) 27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

36. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications. (2017).

37. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res methods instruments Comput. (2004) 36:717–31. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553

38. Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. (1982). doi: 10.2307/270723

39. Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield CH, Perry BD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2006) 256:174–86. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

40. Smolak L, Levine MP. Toward an integrated biopsychosocial model of eating disorders. Wiley Handb eating Disord. (2015), 929–41. doi: 10.1002/9781118574089

41. Hilbert A, Petroff D, Herpertz S, Pietrowsky R, Tuschen-Caffier B, Vocks S, et al. Meta-analysis on the long-term effectiveness of psychological and medical treatments for binge-eating disorder. Int J Eating Disord. (2020) 53:1353–76. doi: 10.1002/eat.23297

42. Miniati M, Callari A, Maglio A, Calugi S. Interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders: Current perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2018) 11:353–69. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S120584

43. Todisco P, Meneguzzo P, Garolla A, Diomidous E, Antoniades A, Vogazianos P, et al. Understanding dropout and non-participation in follow-up evaluation for the benefit of patients and research: evidence from a longitudinal observational study on patients with eating disorders. Eat Disord. (2023) 31:337–52. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2022.2135738

44. Linardon J, de la Piedad Garcia X, Brennan L. Predictors, moderators, and mediators of treatment outcome following manualised cognitive-behavioural therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review. Eur Eating Disord Rev. (2017) 25:3–12. doi: 10.1002/erv.2492

45. Meneguzzo P, Bonello E, Tenconi E, Todisco P. Enhancing emotional abilities in anorexia nervosa treatment: A rolling-group cognitive remediation and emotional skills training protocol. Eur Eating Disord Rev. (2024) 32(5):1026–37. doi: 10.1002/erv.3113

46. Shiovitz-Ezra S, Parag O. Does loneliness ‘get under the skin’? Associations of loneliness with subsequent change in inflammatory and metabolic markers. Aging Ment Health. (2019) 23:1358–66. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1488942

47. Rowlands K, Grafton B, Cerea S, Simic M, Hirsch C, Cruwys T, et al. A multifaceted study of interpersonal functioning and cognitive biases towards social stimuli in adolescents with eating disorders and healthy controls. J Affect Disord. (2021) 295:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.013

48. Christensen KA, Haynos AF. A theoretical review of interpersonal emotion regulation in eating disorders: Enhancing knowledge by bridging interpersonal and affective dysfunction. J Eat Disord. (2020) 8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40337-020-00298-0

49. Brewerton TD. An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2019) 28:445–62. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940

50. Day S, Hay P, Tannous WK, Fatt SJ, Mitchison D. A systematic review of the effect of PTSD and trauma on treatment outcomes for eating disorders. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2024) 25:947–64. doi: 10.1177/15248380231167399

51. Landry J, Asokumar A, Crump C, Anisman H, Matheson K. Early life adverse experiences and loneliness among young adults: The mediating role of social processes. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:968383. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.968383

52. Allen SF, Gilbody S, Atkin K, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. The associations among childhood trauma, loneliness, mental health symptoms, and indicators of social exclusion in adulthood: A UK Biobank study. Brain Behav. (2023) 13:e2959. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2959

53. Dagan Y, Yager J. Addressing loneliness in complex PTSD. J Nervous Ment Dis. (2019) 207:433–9. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000992

54. Kong S, Bernstein K. Childhood trauma as a predictor of eating psychopathology and its mediating variables in patients with eating disorders. J Clin Nurs. (2009) 18:1897–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02740.x

55. Schaefer LM, Hazzard VM, Wonderlich SA. Treating eating disorders in the wake of trauma. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2022) 6:286–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00072-4

56. Currin L, Schmidt U. A critical analysis of the utility of an early intervention approach in the eating disorders. J Ment Health. (2005) 14:611–24. doi: 10.1080/09638230500347939

57. Gkintoni E, Kourkoutas E, Vassilopoulos SP, Mousi M. Clinical intervention strategies and family dynamics in adolescent eating disorders: A scoping review for enhancing early detection and outcomes. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:4084. doi: 10.3390/jcm13144084

58. Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. (2007) 42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316

59. Frazier PA, Tix AP, Barron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. (2004) 51:115. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115

Keywords: trauma, loneliness, mediation, child trauma, psychopathology, eating disorders

Citation: Meneguzzo P, Marzotto A, Mezzani B, Conti F, Maggi L and Todisco P (2024) Bridging trauma and eating disorders: the role of loneliness. Front. Psychiatry 15:1500740. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1500740

Received: 23 September 2024; Accepted: 25 November 2024;

Published: 10 December 2024.

Edited by:

Lené Levy-Storms, University of California, Los Angeles, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Meneguzzo, Marzotto, Mezzani, Conti, Maggi and Todisco. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paolo Meneguzzo, cGFvbG8ubWVuZWd1enpvQHVuaXBkLml0

†ORCID: Paolo Meneguzzo, orcid.org/0000-0003-3323-6071

Paolo Meneguzzo

Paolo Meneguzzo Anna Marzotto3

Anna Marzotto3 Patrizia Todisco

Patrizia Todisco