Abstract

Background:

Associating temporal variation of biomarkers with the onset of psychotic relapse could help demystify the pathogenesis of psychosis as a pathological brain state, while allowing for timely intervention, thus ameliorating clinical outcome. In this systematic review, we evaluated the predictive accuracy of a broad spectrum of biomarkers for psychotic relapse. We also underline methodological concerns, focusing on the value of prospective studies for relapse onset estimation.

Methods:

Following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) guidelines, a list of search strings related to biomarkers and relapse was assimilated and run against the PubMed and Scopus databases, yielding a total of 808 unique records. After exclusion of studies related to the distinction of patients from controls or treatment effects, the 42 remaining studies were divided into 5 groups, based on the type of biomarker used as a predictor: the genetic biomarker subgroup (n = 4, or 9%), the blood-based biomarker subgroup (n = 15, or 36%), the neuroimaging biomarker subgroup (n = 10, or 24%), the cognitive-behavioral biomarker subgroup (n = 5, or 12%) and the wearables biomarker subgroup (n = 8, or 19%).

Results:

In the first 4 groups, several factors were found to correlate with the state of relapse, such as the genetic risk profile, Interleukin-6, Vitamin D or panels consisting of multiple markers (blood-based), ventricular volume, grey matter volume in the right hippocampus, various functional connectivity metrics (neuroimaging), working memory and executive function (cognition). In the wearables group, machine learning models were trained based on features such as heart rate, acceleration, and geolocation, which were measured continuously. While the achieved predictive accuracy differed compared to chance, its power was moderate (max reported AUC = 0.77).

Discussion:

The first 4 groups revealed risk factors, but cross-sectional designs or sparse sampling in prospective studies did not allow for relapse onset estimations. Studies involving wearables provide more concrete predictions of relapse but utilized markers such as geolocation do not advance pathophysiological understanding. A combination of the two approaches is warranted to fully understand and predict relapse.

1 Introduction

The etiopathological underpinnings of psychosis, defined as a pathological brain state (1), as well as psychotic disorders as diagnostic constructs, still elude us after more than 50 years of research (2). Apart from their inherent heterogeneity regarding clinical manifestations, it is challenging to demystify the causality of psychotic disorders due to their seemingly random onset, chronic course and recurrent nature, which leaves a lasting and progressive impact on patient functioning. Crucially, over 80% of individuals with psychotic disorders will experience relapses (3), or transitions to a state of psychosis. The current best approach to prevent them is via continuation of antipsychotic and/or mood stabilizing treatment for years (4), which then exposes patients to a variety of serious medication side effects. It is established in the literature that this leads to issues regarding compliance (5), while treatment non-adherence has been shown to be the single most significant predictor of relapse (6). Furthermore, even among those who follow treatment, there is still a 20-30% chance of symptom recurrence after First-Episode Psychosis (FEP) (7). From a clinical perspective, early identification of psychotic relapse would be of vital importance since the clinician would then be able to stop the vicious cycle of symptom recurrence after treatment discontinuation.

Nevertheless, an overwhelming percentage of studies in the field of psychotic disorders revolve around distinguishing between patients and healthy controls. The most prominent study design includes a cross-sectional comparison of a potentially implicated etiological factor between patients and healthy controls, or between patients with different diagnoses. While this approach has unraveled several risk factors for psychotic disorders, it does not allow for predictions regarding the course of the disease for individual patients, therefore providing limited clinical benefits. Studies involving relapse, on the other hand, could shed light on possible deciders of disease course, but are significantly harder to design and perform. Given the chronicity and random trajectory of the phenomenon, these studies must be prospective, while ideally measurements or monitoring need to be close to continuous, to have available data at, or around the time of relapse, to draw comparisons with data originating from periods of remission. Additionally, the amount of data required to be amassed for a sufficient number of relapse events to be recorded is massive, given their relative sparsity (an epidemiological study (8) measured 751 events in 3980-participant years). Analyzing such a long-term phenomenon entails diligent patient monitoring for years. Another caveat that needs to be accounted for, is that treatment adherence cannot be controlled in such studies. The lack of a scalable way to confirm medication status (9) at relapse introduces confounding factors that could hinder result reliability.

Despite these obstacles, there have been attempts to map the course of psychotic disorders and identify potential risk factors, or predictors for relapse. The vast majority of these efforts involve models with solely clinical variables as predictors and include no biological factors (or biomarkers) [see (10) for a meta-review]. Treatment non-adherence and premorbid functioning have been isolated as the most significant predictors of relapse. However, two distinct issues arise when developing exclusively clinical prediction models. Firstly, little to no new insight is gained regarding pathophysiology, thus no progress can be achieved regarding intervention effectiveness and new medications. Additionally, clinical models provide no information regarding the exact temporal onset of a relapse occurrence, which would allow for early intervention. Clinical variables such as family history, alcohol consumption, or drug abuse are represented as binary variables measured at one instance in time (cross sectional design). Other variables, such as premorbid functioning do not evolve at all in time. Yet the course of psychotic disorders is dynamic in time, characterized by psychotic episodes followed by remission phases. Moreover, given the relatively sudden onset of symptom recurrence, it would be reasonable to assume some biological change happening on short time scales. To capture it, one would have to monitor some biological factors, or biomarkers, at a sufficiently high frequency. The term biomarker is defined as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” (11), and it could refer to anything from the serum concentration of a specific hormone to the time elapsed when a human responds to some stimulus [Reaction Time). Notably, biomarkers evolve on various time scales, ranging from milliseconds to hours or even days, in stark contrast to clinical markers. Heart rate, for example, has been shown to exhibit variability on very short time scales (in the 0.15 - 0.4 Hz frequency range (12)], but also fluctuates diurnally, especially between night and day time (13). To conclude, clinical variables seem unsuitable for predicting the temporal onset of relapse, whereas the same cannot be said for biomarkers (14), whose short-term alteration could correlate with symptom reignition.

It becomes apparent that the utilization of biomarkers in predictive models for psychotic relapse, either exclusively or in conjunction with clinical parameters, could provide the missing piece to solve the conundrum in hand. In this systematic review, we consolidate and present the findings of all studies using genetic, blood-based, neuroimaging, cognitive and behavioral biomarkers as predictors for psychotic relapse. We also cover a distinct category of studies in which data is continuously accrued via wearable devices or smartphones. Data from these studies includes accelerometer or heart rate measurements, which are commonly used biomarkers, but also information regarding geolocation, text messages, duration of phone calls, or screen activity, which we consider as proxies of behavior. The detailed inclusion criteria are reported in the methods section, but to outline the process, we included studies that longitudinally monitored biomarker levels and clinically evaluated patients to identify relapse. Biomarker levels were either measured continuously, or at two or more distinct time points (usually with one corresponding to a period of relative health and one corresponding to relapse). We included cross sectional studies if and only if the entire sample consisted of patients experiencing symptom recurrence, and not first-episode psychosis. The objective of the present review is to delineate the progress that has been accomplished so far regarding relapse prediction via biomarker monitoring, but also to underline potential methodological caveats.

2 Methods

2.1 Main outcome

The main outcome of this study is psychotic relapse, which is defined clinically, and refers to the occurrence of a noninitial psychotic episode, after a period of symptom remission. We largely base our definition of remission on Andreassen’s criteria (20), where the authors propose a clinical framework for defining remission in SCZ based on score thresholds in the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANNS), for items such as P1 (Delusions), P2 (Conceptual Disorganization), P3 (Hallucinatory behavior), and G9 (Unusual thought content), as well as in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BRPS), regarding items 8(Grandiosity), 11 (Suspiciousness), 12 (Hallucinatory behavior) and others. Andreassen et al. suggest that these scores must remain at below-threshold levels for 6 months for remission to be defined, but we impose the lower bound of 1 month in the present review. Moreover, we deemed that if patients were discharged from the hospital after a clinical evaluation, it is implied that they entered a period of potential remission, even if the actual scores of the evaluations were not reported. We only excluded studies that treated rehospitalizations as adverse outcomes, with no mention of SCZ diagnosis or psychotic symptomatology as the reason for readmission to the hospital. The relative leniency of these criteria is due to the objective of this study, which is to bring the findings of biomarkers research to the forefront. Given the state of the field, we do not believe it is yet appropriate to formulate standardized guidelines, which would be directly applied in clinical practice.

2.2 Study design overview

This systematic review was conducted in alignment with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [ (15, 16), see Supplementary Materials]. The selection process of articles that were included broadly consisted of three phases, which started in February of 2024 and were concluded in April of the same year. During the first step of the process, a list of relevant keywords were identified, which were then run against records in the PubMed and Scopus databases. We also hand-checked citations of all retrieved papers, obtaining no new, unique records. Search results were then screened (title and abstract initially, then full papers) based on a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria tailored to the PICOS/PECOS worksheet (15, 16). The final step included a categorization of studies into subgroups according to the nature of examined biomarkers, namely genetic, blood-based, neuroimaging, cognitive, behavioral and related to wearable devices and smartphones. Studies were then meticulously analyzed, and relevant information was distilled in the form of tables.

2.3 Selection and analysis procedure

To begin with, PubMed and Scopus databases were searched based on a list of predetermined keywords (exact search queries depicted in Table 1), with no temporal restrictions and no other applied filter.

Table 1

| Database | Search query | No of results PubMed + Scopus = Total results (no deduplication) |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed+Scopus | (“psychotic” AND “relapse” AND “prediction”) | 454 + 181 = 635 |

| PubMed+Scopus | (“psychotic” AND “relapse” AND “biomarkers”) | 64 + 40 = 104 |

| PubMed+Scopus | (“schizophrenia” AND “relapse” AND “prediction”) | 633 + 299 = 932 |

| PubMed+Scopus | (“schizophrenia” AND “relapse” AND “biomarkers”) | 121 + 99 = 220 |

| Results across all queries:1891 |

Keyword combinations used in queries in both PubMed and Scopus, alongside the number of results produced in the initial search.

After removing duplicate records, we scanned (AS and CT) the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies independently and excluded those that were irrelevant to the research question. Any discrepancies were addressed by a third independent reviewer (PF or NS). The main reason for exclusions at this stage of the process was that in search queries using the key word “prediction”, which yielded more results, the utilization of biomarkers instead of clinical variables as predictors was relatively rare. We then defined (see Table 2 below) and applied the PICOS/PECOS worksheet criteria to a pool of 121 full papers, ultimately selecting a total of 42 studies for inclusion.

Table 2

| Parameter | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Patients experiencing symptom relapse | Population of solely FEP patients |

| Interventions or Exposures | Measurements of biomarkers, in the genetic, blood-based, neuroimaging, cognitive or behavioral domain | Solely clinical assessments, effects of different treatment regimens. |

| Comparisons | Within the patient group at different time points for longitudinal studies, relapsed vs healthy controls or vs FEP for cross-sectional studies | Treatment groups, groups with different diagnoses, or groups consisting of solely FEP patients in cross-sectional comparisons. |

| Outcomes | Relapse prediction, or relapse risk assessment | Diagnosis distinction, response to medication |

| Study Design | Original studies in English, longitudinal or cross sectional, if and only if the patient group consisted of relapsed patients | Reviews either narrative or systematic, meta-analyses. |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria designed according to the blueprint of the Population, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcomes, and Study Design (PICOS/PECOS) worksheet.

Since the goal of the present review is to assess available means for relapse prediction via biomarker monitoring, we only included original studies using biological or behavioral factors, involving relapsed patients. The notion of prediction implies monitoring the evolution of some phenomenon in time and drawing conclusions regarding occurrence rate and time of onset relative to some fixed time point. This would suggest that only longitudinal studies should be included, however, we also include cross sectional studies where patients experiencing relapse are compared to FEP patients or healthy controls. While this design introduces a plethora of confounding factors (for instance FEP patients are usually drug-naïve, whereas relapsed patients have taken or are still taking antipsychotic medication), it is still meaningful to consider them, since for certain categories, such as blood-based biomarkers, continuous and even sequential monitoring presents extreme practical difficulties. Regarding study outcomes, we only included studies where the main objective was to either predict relapse in a temporal sense, or to at least shape an a priori relative-risk profile. Studies related to diagnosis or treatment effects were excluded.

The 42 studies that were finally selected, were thoroughly analyzed, and the following information was extracted: Authors and country of origin, Study design (longitudinal or cross sectional), Sample size and diagnosis for patient groups, Data collection process, examined biomarkers, Analysis tools, Main objectives related to relapse, Statistical results and Synthesis of main findings. Data extraction was initially performed by AS, and was independently validated by CT, PF, and NS. No protocol was registered beforehand for this review. Excel files and data used in this systematic review are available upon request.

2.4 Quality assessment of included studies

The Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS (17), Table 3) was utilized for risk of bias assessment of included studies and it encompasses questions related to study objective and design, sample size justification, sample selection process and reasons for exclusion of participants, internal validity, presentation and replicability of statistical tools and their corresponding results as well as limitations, funding sources or conflicting interests. Note that although theoretically the AXIS tool is tailored to cross sectional studies, almost all questions can apply to a wider range of study designs. Reviewers had the same assigned roles as in the data extraction procedure.

Table 3

| The Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) study (Y = YES, N = NO, - = NOT APPROPRIATE) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | (21) | (22) | (23) | (24) | (25) | (26) | (27) | (28) | (29) | (30) | (31) | (32) | (33) | (34) | (35) | (36) | (37) | (38) | (39) | (40) | (41) |

| Introduction | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Were the aims/objectives of the study clear? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Methods | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| 3. Was the sample size justified? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 4. Was the target/reference population clearly defined? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5. Was the sample frame taken from an appropriate population base so that it closely represented the target/reference population under investigation? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 6. Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

| 7. Were measures undertaken to address and categorize Nn-responders? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y |

| 8. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aims of the study? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 9. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured correctly using instruments/measurements that had been trialled, piloted or published previously? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 10. Is it clear what was used to determined statistical significance and/or precision estimates? (eg, p values, CIs) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 11. Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Were the basic data adequately described? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 13. Does the response rate raise concerns about Nn-response bias? | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| 14. If appropriate, was information about Nn-responders described? | – | – | N | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Y | Y | – | N | – | – | N | – |

| 15. Were the results internally consistent? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 16. Were the results for the analyses described in the methods, presented? | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Discussion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Were the authors’ discussions and conclusions justified by results? | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 18. Were the limitations of the study discussed? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Were there any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of results? | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 20. Was ethical approval or consent attained? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Introduction | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Were the aims/objectives of the study clear? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Methods | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)? | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3. Was the sample size justified? | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 4. Was the target/reference population clearly defined? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5. Was the sample frame taken from an appropriate population base so that it closely represented the target/reference population under investigation? | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 6. Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation? | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 7. Were measures undertaken to address and categorize Nn-responders? | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 8. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aims of the study? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 9. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured correctly using instruments/measurements that had been trialled, piloted or published previously? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| 10. Is it clear what was used to determined statistical significance and/or precision estimates? (eg, p values, CIs) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 11. Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Results | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Were the basic data adequately described? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| 13. Does the response rate raise concerns about Nn-response bias? | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| 14. If appropriate, was information about Nn-responders described? | – | Y | – | – | – | – | – | – | N | Y | – | – | – | – | – | N | – | – | N | – | – |

| 15. Were the results internally consistent? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| 16. Were the results for the analyses described in the methods, presented? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Discussion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Were the authors’ discussions and conclusions justified by results? | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| 18. Were the limitations of the study discussed? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Other | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Were there any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of results? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 20. Was ethical approval or consent attained? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Quality assessment of included studies via the appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS).

3 Results

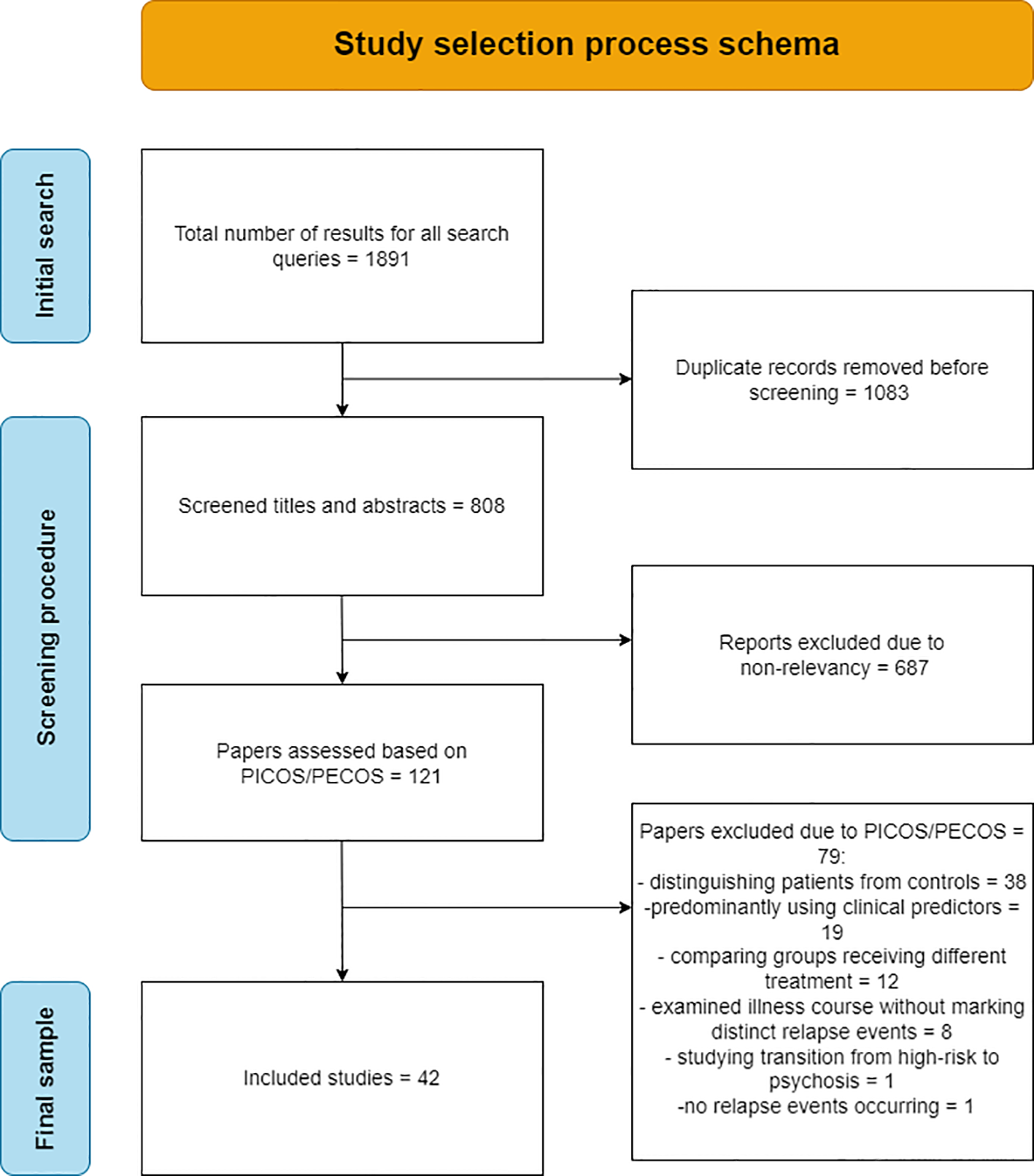

Figure 1 depicts a schematic representation of the selection process, which starts with a series of queries in the PubMed and Scopus databases yielding a total of 1891 results. Given the conceptual closeness of the various keyword combinations, duplicate records were expected and after their removal, a list of 808 unique papers was compiled. Of these 808 papers, 687 were excluded from the title and abstract, on grounds of non-relevancy to the research question. After application of the defined PICOS/PECOS criteria to the remaining 121 papers, a total of 42 were finally selected and analyzed. Of the 79 papers excluded based on PICOS/PECOS, 19 incorporated models using predominantly clinical parameters and not biomarkers, 38 were focused on distinguishing patients from controls, 12 made comparisons between groups receiving different treatment, 8 examined illness course via symptom scales such as PANNS, but relapse events were not identified and classified, 1 (18) sought to predict relapse, but no relapse instances occurred due to limited study duration and 1 (19) revolved around the transition of patients from high-risk to psychosis.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the selection process of the final 42 papers analyzed in the review.

The final 42 studies were grouped based on the nature of the examined biomarkers. This categorization consisted of:

the genetic biomarker subgroup (n = 4, or 9%) summarized in Table 4,

the blood-based biomarker subgroup (n = 15, or 36%) summarized in Table 5,

the neuroimaging biomarker subgroup (n = 10, or 24%) including studies in structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), functional MRI, electroencephalogram (EEG) and Positron Emission Tomography. summarized in Table 6,

the cognitive-behavioral biomarker subgroup (n = 5, or 12%) including markers used to assess performance in cognitive domains such as memory, attention, perception and executive function, as well as behavior markers based on internet search history and Facebook posting habits, summarized in Table 7,

and the wearables biomarker subgroup (n = 8, or 19%). which encompasses studies that apply machine learning models on passively collected data from wearable devices such as smartwatches, but also from smartphones, to identify sudden pattern breaks constituting the signature of impending relapse, summarized in Table 8.

Table 4

| Study/Country | Study Design | Sample (Diagnosis) | Data Collection Process | Biomar-kers examined | Analysis Tools | Main objectives | Statistical Results | Synthesis of main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meier et al.2015 (21) (Denmark/Germany) | Cross sectional | n = 1681 patients SCZ, ICD-10 for Danish sample/n = 1306 SCZ for German sample | DNA extracted from dry blood spots and genome-wide amplified | >Genomic risk profile score (GPRS), consisting of alleles at thou-sands of loci | Logistic regression model for GPRS calculation, Spearman’s rank correlation to assess relationship between GPRS and number of admissions | >Identify a link between GPRS and admission frequency/duration | Danish Sample: Patients divided into 4 groups (SCZ or other, in or out-patient). Analysis was repeated with different P value thresholds (0.05,0.1,0.2) for inclusion of single nucleotide polymorphisms. For a P-value threshold of 0.05, Spearman’s r values for GPRS with number of admissions were 0.053, 0.063, 0.044, 0.054 and the corresponding P-values were 0.066, 0.037, 0.103, and 0.06. German Sample: Spearman’s r = 0.066 with a P-value of 0.016. For a P-value threshold of 0.2 (21) report the following r values (0.077,0.081,0.074,0.073) with the corresponding P-values (0.014,0.01,0.016,0.018) for the Danish sample, and an r = 0.062 with P =0.024 for the German sample. | GPRS correlates with frequency and duration of admissions. The highest correlation values were observed when the threshold for including single-nucleotide polymorphisms was set to 0.2, when compared to lower values, implying that chronic SCZ could be associated with a wider range of susceptibility variants. | |

| Pawelczyk et al., 2015 (22) (Poland) | Cross sectional | n = 86 patients with SCZ according to ICD-10 criteria (Non-random, convenience sample), who were split into two groups: Early-SCZ, n=42 and Chronic SCZ, n=44. The criterion for classification in the chronic group, was one distinct relapse event and a minimum of 2 years from illness onset. | Genomic DNA from blood samples, telomeric DNA amplified via qPCR assay. Clinical evaluation using PANNS for SCZ symptoms and GAF for overall psychoso-cial functioning | >Telomere length | A one-way Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was utilized to control for confounders, mainly age, with PANNS scores and hospital admissions/number of psychotic episodes as the dependent variables. Univariate analyses (Spearman’s rank correlation) were performed to examine correlations of telomere length with disease severity/chronicity irrespective of group. | >Assessing whether shortening of telomere length predicts disease severity and number of relapses | In univariate analyses, telomere length negatively correlated with number of psychotic episodes (r = -0.594/p <0.001). Subgroup analyses presented the same trends but did not reach significance. In the ANCOVA, a difference in telomere length between patients with E-SCZ and C-SCZ (F [1,82] =47.08, P<0.001) was reported. | Telomere length is connected to disease chronicity, since a (negative) correlation was found between TL and number of psychotic episodes. Furthermore, telomere length was shorter in patients with the Chronic Subphenotype, indicating that telomere erosion could lead to a more severe disease course. | |

| Gasso et al., 2021 (23) (Spain) | Prospective (2 samples: at baseline and after 3 years or at relapse) | n= 91 patients at baseline, n = 31 at relapse, n = 36 after 3 years of follow up. SCZ diagnosis according to DSM-IV, all patients in remission at baseline, according to Andeassen’s criteria (20). | Total RNA (Clariom S Human Array) covers over 337,100 transcripts and variants, which in turn represent 20,800 genes.) from blood samples, clinical follow-up every 3 months, for 3 years, via PANNS for symptomatology | >25 modules or “network” type structures of co-expres-sed genes. Module sizes (in number of genes) varied from 41 to 5627. | Genome-wide expression analysis to construct the modules or “networks” of co-expressed genes. Preservation analysis to examine longitudinal changes to these modules. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis [] to assess the predictive properties of selected modules. Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression analysis to assess the effect of the best performing network on time taken to relapse. | >To examine whether changes in network connectivity properties of co-expressed gene clusters can predict relapse. | DarkRed module consisting of 53 genes (alongside DarkGrey, 41 genes) were semi-conserved (i.e. Zsummary statistic > 2 but <10. The Zsummary statistic is used to assess similarity in connectivity patterns between two networks, with higher values indicating more similar, persisting patterns) after 3 years of follow-up and at relapse. Relapse prediction accuracy of the semi-conserved modules was tested with ROC curve analysis. DarkRed module had the highest predictive value (AUC = 0.603, CI = 0.464-0.742), followed by Dark-Grey (AUC = 0.556, CI = 0.414–0.699), but all p values > 0.05. Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression analysis: Patients were split based on gene expression for DarkRed module. Those at the highest 75 percentile (N = 20) showed higher risk of suffering a relapse (OR = 2.10, CI = 1.01–4.33,beta = 0.742 ± 0.370, p = 0.045). | The ability of semi-conserved networks of co-expressed genes to predict relapse did not reach the significance threshold. However, patients with higher expression of genes in the DarkRed module showed higher risk of relapse and earlier appearance of relapse. DarkRed module genes participate in biological processes related to the ubiquitin proteosome system, which influences neuronal development. | |

| Segura et al.2023 (24) (Spain) | Cross sectional | n = 114 patients (SCZ, DSM-IV)/ 58 relapse, 56 non-relapse | Genomic DNA from blood samples, clinical follow-up every 3 months, for 3 years, via PANNS for symptomatology | >Polygenic risk score | Binary logistic regression, with relapse as the dependent variable and polygenic risk score as the independent variable. (covariates: sex, age, ethnicity and the first 10 components of the genetic Principal Components Analysis) | >Find group differences in Polygenic risk scores between relapsers and non-relapsers. | 4 groups for High Polygenic Risk (for Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, educational attainment, cognitive performance). At the p= 0.05 threshold for selecting risk alleles, there was a significant association with relapse risk only in the Educational Attainment group. (β = -0.042, p = 0.043), with an R squared value of 2.1%. | For high-risk SCZ and BP groups, there was no significant association between Polygenic Risk Score and relapse, for any of the p threshold values for selecting risk alleles. | |

Presentation of analysis results for papers using genetic biomarkers.

Table 5

| Study/Country | Study Design | Sample (Diagnosis) | Data Collection Process | Biomar-kers examined | Analysis Tools | Main objectives | Statistical Results | Synthesis of main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaddurah-Daouk et al., 2012 (25) (USA) | Cross sectional | n = 40 patients (SCZ, DSM-IV)/20 drug-naive FEP, 20 acutely relapsed | Blood samples, assessment of plasma lipid profiles. BPRS for clinical symptom severity. | >5 different human plasma phospholi-pids | Wilcoxon rank-sum test to assess differences between patients and controls, as well as FEP and relapsed patients. False discovery rate was used to correct for multiple comparisons. | >Comparing different plasmalogens concentrations in FEP vs relapsed patients. | There were no significant differences in any of the examined plasmalogens (Phosphatidylethanolamine class, containing fatty acids 16:0, 18:0, 18:1n7, 18:1n9/Phosphatidylcholine class, containing fatty acids 16:0, 18:0, 18:1n7, 18:1n9). Statistical data was not shown in the paper, as the main focus was the comparison between all patients combined and healthy controls. | Plasmalogens correlate with diagnosis of SCZ, but no significant differences were observed between FEP and relapsed patients, indicating that they are probably not appropriate biomarkers to predict chronic disease course. | |

| Schwartz et al.2012 (26) (Germany) | Prospective | n = 77 patients (DSM-IV SCZ)/18 experienced relapse, 59 did not. Patients who relapsed were further classified into two groups, each consisting of 9 subjects, depending on the time elapsed between last clinical visit and relapse. (short-term relapse vs long-term relapse) | Blood samples at baseline (acute phase), after 6 weeks of treatment, and during relapse (for patients who relapsed). Multiplexed immuno-assays to measure serum concentra-tions of 191 proteins and small molecules. Clinical assessment with PANNS. | >191 proteins and small molecules | Shapiro-wilk test to test normality of each analyte’s distribution. Associations were examined with non-parametric Spearman’s correlations, adjusted for false discovery rate. Group comparisons (short-term relapse vs long-term relapse) were performed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. For classification of patients in the relapse or non-relapse group based on the values of serum molecules, a Random Forests analysis was utilized. | >Identify predictors of time to relapse among a panel of 191 candidate molecules. | Random forests analysis lead to the selection of a group of molecules comprised of leptin,proinsulin, TGF-a, b-cellulin, CD5L, CD40, Apo CI, clusterin, insulin, interleukin-8, MIP-1-b and matrix metalloproteinase 3, whose combination predicted short vs long term relapse at an accuracy of 94.5%. BMI changes alone achieved a predictive accuracy of 83.4%. Non-parametric Wilcoxon tests for each molecule, resulted in significant differences for 13 of those after performing ANCOVA (on log10 transformed data) to account for the effect of BMI. Those were Leptin (p = 0.033), Proinsulin (p = 0.021), Transforming growth factor alpha (p = 0.018), b-Cellulin (p = 0.015), CD5 L (p = 0.002), Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (p = 0.029), CD40 (p = 0.011), Macrophage-derived chemokine (p = 0.021), Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (p = 0.042), Apolipoprotein CI (p = 0.046), Matrix metalloproteinase 7 (p = 0.045), b-2–Microglobulin (p = 0.046) and Tumor necrosis factor receptor like 2 (p = 0.039). | Alterations in the concentrations of certain serum molecules may be predictive of the time to relapse. However, antipsychotic treatment (or non-compliance to it), remains a significant confounding factor, especially for molecules related to metabolism, such as leptin, pro-insulin, insulin and C-peptide. | |

| Borovcan-in et al., 2015 (27) (Serbia) | Cross sectional | n = 125 patients: 78 FEP (F23 according to ICD-10) and 47 acutely relapsed (F20 according to ICD-10) | Blood samples and ELISA immunoassay to determine IL-23 levels. Clinical assessment with PANNS. | >IL-23 | Shapiro-wilk test to assess normality of IL-23 distribution. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate group differences in IL-23 levels. | >Comparing IL-23 levels between FEP patients, relapsed patients, and healthy controls. | There was no significant difference in serum IL-23 levels between FEP and relapsed patients. (511.70 ± 66.25 for FEP, 652.08 ± 119.24 for relapse, p = 0.63) No changes for FEP or relapsed patients in IL-23 levels after 4 weeks of treatment (p = 0.656 and p = 0.706). | IL-23 could be a useful trait marker for SCZ, since they differ between SCZ patients and HC, but not a state marker, since there were no differences in IL-23 levels between FEP patients and relapsed patients. | |

| Morera-Fumero et al., 2017 (28) (Spain) | Prospective (samples at admission, and at discharge) | n = 43 SCZ patients (DSM-IV) | Blood samples collected at admission-discharge. Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) was measured, which is the antioxidant capacity of water soluble molecules such as albumin or transferrin. Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) scale for clinical symptoms. | >Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) | ANOVA for repeated measures to compare group mean at admission and discharge. | >Comparing TAC values during acute psychotic relapse and after remission in the same group of patients. | TAC values did not differ significantly between admission and discharge (mean values: 0.66+/- 0.14 and 0.64+/- 0.15, p > 0.05) | While patients have significantly lower TAC values than controls, both at admission and discharge, the difference within the patient group at the two time points did not reach significance. | |

| Szymona et al.2017 (29) (Poland) | Prospective (2 samples, during relapse and remission) | n = 51 patients (SCZ, ICD-10) | Blood samples during relapse then at remission, determined by PANNS. EDTA tubes were used for plasma cytokines analysis and clot activating tubes were used for serum analyses of kynurenines. | >Kynurenic Acid (KYNA), 3-Hydroxykynurenine (3-HK), sIL-2R, IFN-α, IL-4 | Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons between the same group of patients at relapse and at remission. | >Assessing levels of kynurenic acid, 3-hydroxyky-nurenine, and various cytokines during relapse and remission | There were no significant differences between relapse and remission in any of the examined biomarkers. Mann-Whitney U test results for KYNA measured in pmol/100μl (relapse: 0.95 ± 0.45, remission: 0.97 ± 0.33, p > 0.05), for 3HK in pmol/100μl (relapse: 8.54 ± 4.19, remission: 10.1 ± 6.75, p > 0.05), for sIL-2R in ng/ml (relapse: 0.88 ± 0.46, remission: 0.88 ± 0.32, p > 0.05), for IFN-α in pg/ml (relapse: 13.1 ± 22.66, remission: 9.14 ± 15.64, p > 0.05). | While KYNA, 3HK and IL-4 levels differed between patients and controls, and thus have potential as trait markers, none of the examined substances differed between relapse and remission, indicating that they are not likely candidates as state markers for acute relapse. | |

| Pillai et al., 2017 (30) (USA) | Prospective (maximum 23 samples per subject over a period of 30 months) | n = 221 patients with SCZ or SAD according to DSM-IV | Blood sample every 6 weeks or at relapse, BDNF assessed with ELISA. Clinical follow up for 30 months. | >plasma BDNF | ROC curve analysis to test the predictive value of baseline BDNF for relapse. Cox regression to model time to relapse as a function of baseline BDNF. Linear regression of successive BDNF values on visit number was performed to measure rate of change, which, alongside summary statistics such as per subject mean, mode, and variance was compared in the group of relapsers vs non-relapsers, via the Wilcoxon rank sum test. | >Correlating baseline BDNF and BDNF variation in time with the occurre-nce of relapse. | ROC curve analysis yielded negative results for BDNF as a predictor of relapse.(AUC = 0.495, p = 0.901 when comparing with the minimally accepted AUC value) Cox regression did not associate baseline BDNF with risk of relapse(Hazard Ratio = 1.000,95% CI = 0.998 - 1.001, p = 0.717) Mean per subject BDNF values did not differ between the group of relapsers and non-relapsers.(p = 0.893) | Although BDNF has been found to correlate with diagnosis of SCZ, it does not seem to have predictive value for adverse outcomes throughout the course of the disease. In a large sample which was prospectively followed up on, neither baseline BDNF values, nor their average over a 30 month time period, could distinguish between the group of patients who subsequently relapsed and the group of those who did not. | |

| Piotrowski et al., 2019 (31) (Poland) | Cross sectional | n = 67 patients (DSM-IV SCZ, SAF, Schizophre-niform disorder, Brief psychotic episode) with 42 FEP patients and 25 acutely relapsed patients | Fasting blood samples, calculation of biochemical parameters in serum. Weight, height, hip and waste circumfe-rence measure-ments. PANNS, GAF, Social and Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) were used for clinical assessment. | >Allostatic (AL) Index, encompassing Systolic and Diastolic blood pressure, BMI, waste to hip ratio, high sensitivity CRP, fibrinogen, albumin, fasting glucose and insulin, total cholesteroltriglyce-rides and cortisol. | In normally distributed variables, ANOVA was used to test for group differences, whereas in non-normally distributed variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized instead. For group differences in the AL index, ANCOVA was used, with age, sex and smoking status as covariates. | >Comparing the level of biological dysfuncti-on, captured by an index comprised of 15 different biomarkers, in FEP and acutely relapsed patients. | ANCOVA resulted in a significant difference in AL index between FEP and acutely relapsed patients (F = 7.99, p < 0.001). Regarding single biomarkers there were significant differences in Systolic Blood Pressure (FEP: 120.2 ± 11.2, relapse: 127.8 ± 8.3, p = 0.001), Waste to Hip Ratio (FEP: 0.85 ± 0.10, relapse: 0.90 ± 0.09, p= 0.003), hsCRP (FEP: 1.2 ± 1.9,relapse: 3.4 ± 3.3, p = 0.006), insulin (FEP: 22.7 ± 22.3, relapse: 15.9 ± 13.5, p = 0.019) and cortisol (FEP: 334.2 ± 74.6, relapse: 443.8 ± 146.7, p < 0.001). | Chronic SCZ patients present more severe systemic biological dysregulations, captured by the AL index, compared to FEP patients. This could be due to continuously elevated stress levels, consistent smoking and poor dietary habits, as well as antipsychotic treatment side effects. | |

| Ozdin and Boke (32) (Turkey) | Retrospe-ctive (2 samples, during relapse and remission) | n = 105 patients (SCZ, DSM-IV) | Blood samples were collected during relapse and then at remission, determined by PANNS scores. Calculation of white blood count (WBC), neutrophils, platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes, as well as the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR) was performed. | >NLR, PLR, MLR, WBC, Neutro-phils, Platelets, Lympho-cytes, Monocytes | Wilcoxon rank-sum test to assess differences between the same patients at relapse and at remission. No reported correction for multiple comparisons. | >Identify differences in ratios of complete blood count markers, between relapse and remission in the same group of patients. | Wilcoxon rank sum tests yielded the following results, for patients at relapse and at remission. For the NLR: mean at relapse (interquartile range in parentheses): 119.80 (1.47), mean at remission: 91.20 (1.37), Z = −3.90, p < 0.01. For the PLR: mean at relapse: 112.84 (63.70), mean at remission: 98.16 (50.98), Z = −2.35, p = 0.019. For the MLR: mean at relapse: 121.01 (0.11), mean at remission: 89.99 (0.08), Z = −4.58, p < 0.01. For the WBC: mean at relapse: 115.68 (3.28), mean at remission: 95.32 (2.51), Z = −3.21, p = 0.001. For Neutrophils: mean at relapse: 119.04 (2.62), mean at remission: 91.96 (1.72), Z = −3.81, p < 0.01. For Platelets: mean at relapse: 110.17 (90.50), mean at remission: 100.83 (48.50), Z = −2.08, p = 0.033. For Monocytes: mean at relapse: 116.51 (0.22), mean at remission:94.49 (0.17), Z = −3.24, p = 0.001. For Lymphocytes: mean at relapse: 101.92 (0.84), mean at remission:109.08 (0.70), Z = −1.46, p = 0.143. | Multiple markers (with the exception of Lymphocytes), indicative of inflammation, originating from the complete blood count, were found to be significantly elevated during relapse compared to remission. These differences could be due to continuation of antipsychotic treatment. | |

| Luo et al.2019 (33) (China) | Prospective (2 samples, at admission and at discharge) | n = 68 patients (ICD-10 SCZ) | Fasting blood samples at admission and discharge, ELISA immunoassay to measure TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 concentrations. PANNS to assess clinical symptomatology. | >TNF-α, IL-6, IL-18 | Paired t-test to test for differences in cytokine concentrations between admission and discharge for the same group of patients. | >Assessing TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 as potential trait markers for SCZ, as well as state markers for relapse. | Paired t-tests for patients at admission and patients at relapse yielded the following (cytokines measured in pg/ml): for TNF-α (admission 12.15 ± 4.01, discharge 11.30 ± 3.66, p > 0.05) for IL-18 (admission 73.60 ± 13.92, discharge 68.47 ± 13.31, p > 0.05) and for IL- 6 (admission 5.61 ± 1.97, discharge 1.62 ± 0.19, p = 0.001) | TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-18 have been found to be elevated in SCZ patients when compared to controls, which was corroborated in this study. Only IL-6 differed significantly at discharge when compared to admission, potentially highlighting IL-6 as a state marker for relapse. | |

| Martínez-Pinteño et al., 2022 (34) (Spain) | Prospective (2 samples: at baseline and after 3 years or at relapse | n = 69 patients (DSM-IV SCZ spectrum)/32 relapse - 37 non-relapse | peripheral blood sample, BDNF and NGF (Nerve growth factor) assessed with ELISA. Clinical follow up every 3 months for 3 years, via PANNS for symptoma- tology | >plasma BDNF and NGF | ROC curve analysis to test the predictive value of baseline BDNF and NGF for relapse. Mann-Whitney U test to assess differences between baseline and follow up BDNF/NGF levels. These differences were then correlated with relapse classification (between subjects variable), using general linear models with repetitive measures and time as the within subject factor | >Correlating longitudi-nal variation of BDNF/NGF with relapse classificati-on. | ROC curve analysis yielded negative results for BDNF/NGF as predictors of relapse. (AUC = 0.473, p = 0.0698 for BDNF and AUC = 0.444, p = 0.931 for NGF) Longitudinal differences between relapse and non-relapse groups did not differ significantly. (F = 2.339, p-value=0.131 for BDNF and F = 2.633, p-value=0.110 for NGF) | Neither BDNF nor NGF differences (relapse- baseline) correlated with relapse classification. Furthermore, in the relapse group, no differences were observed between baseline and relapse BDNF/NGF values, indicating that BDNF/NGF are unlikely to be suitable as biomarkers for psychotic relapse prediction. | |

| Marques and Ouakinin 2022 (35) (Portugal) | Prospective (2 samples: first during relapse, then at remission) | n = 60 patients: 30 SCZ, 30 SAF according to ICD-10) | Fasting blood samples and calculation of Unconju-gated Bilirubin (UCB = total Bilirubin - direct bilirubin). PANNS for assessment of psychotic symptoma-tology/PSP for social functioning. | >Unconju-gated bilirubin | At relapse: ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, to evaluate differences between the three groups. Same process for remission. Same analysis was also utilized to compare relapse and remission within each group. | >Assessing UCB as a biomarker for SCZ and SAF, both at relapse and at remission. | At relapse, UCB levels differed significantly for both SCZ and SAF, when compared to the Bipolar Disorder group, utilized as a control group. (p < 0.05, no F-Statistic reported) At remission, the analysis yielded the same results, with an added difference between SCZ and SAF. (p = 0.05, no F-Statistic) Regarding group differences between relapse and remission, there was a decrease, which did not reach significance for the SCZ group (p = 0.05, no F-Statistic) but did for the SAF group (p = 0.34, no F-Statistic). | Unconjugated bilirubin was found to differ significantly between SCZ or SAF and BP patients, both during relapse and during remission. Furthermore, UCB could serve as a biomarker for relapse, due to the difference reported within each group between relapse and remission. | |

| Fabrazzo et al., 2022 (36) (Italy) | Cross sectional | n = 152 patients with psychiatric diagnosis (SCZ, SAF, OCD, BP) according to DSM-V. 74 during acute relapse, 78 stable out-patients. | Blood samples and measure-ment of 25-OH Vitamin D and Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) via chemilumi-nescence immuno-assays. BPRS for symptom severity. | >Vit-D, PTH | Students t-test for independent samples was utilized with serum levels of PTH, 25-OH-VitD and calcium by patient status (relapsed inpatient vs stable outpatients | >Comparing Vit-D, PTH and calcium levels of acutely relapsed patients with stable outpatients | Vit-D for relapsed vs stable outpatients respectively: 23.1 ± 13.4 pg/mL and 28.3 ± 15.0 pg/mL (p < 0.001, no t-statistic reported) PTH same comparison: 30.6 ± 20.1 pg/mL and 38.5 ± 24.4 pg/mL (p < 0.001, no t-statistic) Calcium same comparison: 9.3 ± 6.4 mg/dL and 9.2 ± 0.8 mg/dL, no group difference. | Significant differences in serum Vit-D and PTH between in-patients experiencing acute relapse and stable outpatients, could implicate deficiencies of these two biomarkers in the pathogenesis of relapse. | |

| Miller et al., 2023 (37) (USA) | Prospective (blood samples up to every 3 weeks, for 30 months) | n = 200 patients (SCZ)/70 relapse, 130 non-relapse | Blood samples collected up to every 3 weeks for the 30-month duration of the study. (mean number of samples was 10.6 per subject due to missed visits etc.) Measure-ment of plasma cytokines and chemokines with the Luminex 8-panel assay. | >IL-2, IL-4 IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, Interferon-γ(IFN-γ) and granulo-cyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). | Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons of baseline values by relapse status. Wilcoxin signed rank test (within-subjects, paired samples design) to compare biomarkers at the visit preceding relapse and the visit after relapse. For those markers which differed significantly, logistic regression was used to test whether their baseline values predicted relapse, with age, sex, race, BMI, smoking and medication as covariates. | >Prospe-ctive design to assess group differences in cytokines levels of patients who relapsed and those who did not, as well as longitudi-nal variation of cytokine levels within the relapse group. | Mann-Whitney U tests revealed no significant differences based on relapse status (IL-2: p = 0.95, IL-4: p = 0.95, IL-6: p = 0.6, IL-8: p = 0.4, IL-10: p = 0.555, TNF-α: p = 0.787, IFN-γ: p = 0.07(trend that did not reach significance, GM-CSF: p = 0.97). Paired data for individual biomarkers (pre and post relapse, 4.4 weeks average temporal distance) revealed a significant decrease in IL-6(p=0.019) and IFN-γ (p=0.012). Logistic regression showed that neither of those at baseline was a predictor of relapse. (IL-6: OR=1.007, 95% CI 0.997–1.017, p=0.157, IFN- γ: OR=1.004, 95% CI 0.996–1.012, p=0.294) | No group differences between relapsed and non-relapsed patients were reported. Within the relapse group, there were significant decreases in IL-6 and INF-γ levels, when comparing pre and post relapse values, implicating both as potential state markers for relapse. However, baseline values of both those cytokines did not predict relapse. | |

| Lin et al., 2023 (38) (China) | Cross sectional | n = 64 SCZ patients (34 FEP, 30 recurrent) | Blood samples and identification of metabolites with the Automatic Statistical Identification in Complex Spectra package. The relationship between traits and metabolites was examined with Weighted correlation network analysis. | >LC-MS (Liquid Chromato-graphy-Mass Spectro-metry) and HNMR (Hydrogen-Nuclear Magnetic resonance) metabolo-mics: modules or “networks” of different metabo-lites | WGCNA (Weighted correlation network analysis), MCODE (Molecular Complex Detection), CytoHubba and Lilikoi algorithms were used to identify weighted co-expression networks that were then correlated with traits. Student’s t test (for differences between two groups) and one-way ANOVA (among three groups), with p 0.05 as the significance threshold. | >Using weighted correlation networks to identify clusters of metaboli-tes associated with SCZ relapse. | WGCNA using a total of 458 metabolites, yielded 4 different modules. The turquoise module, containing 317 metabolites, resulted in the highest module-trait correlation (Pearson r = -0.78, p <0.0001. Trait refers to the status of the subjects, i.e. FEP, recurrent patients. Phenylalanylphenylalanine isolated as the key biomarker. One-way ANOVA revealed significantly lower phenylalanylphenylalanine levels in recurrent compared to FEP patients (p <0.05). | Weighted correlation network analysis revealed a cluster of 317 metabolites which correlated with clinical condition (FEP, recurrent patients and healthy controls). Phenylalanylphenylalanine was isolated as a potential state biomarker, as it differed between FEP and recurrent patients. | |

| Isayeva et al., 2024 (39) (Italy) | Prospective (4 samples, every 6 months for 2 years) | n = 105 patients with 64 SCZ and 41 Schizoaffe-ctive Disorder, according to DSM-IV | Blood sample every 6 months for 2 years and BDNF assessed with ELISA. Clinical evaluation every visit via PANNS and PSP for social functioning. | >serum Brain-Derived Neurotro-phic Factor (BDNF) | Linear mixed effects model, with clinical remission, functional remission and relapse at various timepoints (T1 = 6 months etc.) as the independent variable (age, sex as covariates) and serum BDNF as the dependent variable | >Correlating baseline BDNF and BDNF variation in time with the state of maintained remission or relapse. | There was no statistically significant association between Clinical remission at 6,12,18 or 24 months, or recovery at 6 and 12 months with serum BDNF levels.(Z1 = 0.623, p1 = 0.533/Z2 = − 0.526, p2 = 0.599/Z3 = 0.073, p3 = 0.942/Z4 = 0.399, p4 = 0.689/Z5 = 0.474, p5 = 0.635/Z6 = − 0.521, p6 = 0.603) However, there was a significant correlation between baseline BDNF levels for subjects in clinical remission at 6 months (z = − 2.543, p = 0.011). | Longitudinal variation in serum BDNF did not correlate with the level of clinical or functional remission. Baseline BDNF levels significantly correlated with maintained remission for at least 6 months. | |

Presentation of synthesized findings from papers using non-genetic, blood-based biomarkers.

Table 6

| Study/Country | Study Design | Sample (Diagnosis) | Data Collection Process | Biomar-kers examined | Analysis Tools | Main objectives | Statistical Results | Synthesis of main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lieberman et al., 2001 (40) (USA) | Prospective | n = 107 patients at baseline (SCZ or SAF) 51 patients had MRI data after at least 12 months of follow-up (study attrition) | structural MRI scans at baseline and every 18 months during follow-up Clinical follow-up for up to 6 years via SADS, SANS, CGI, and EPS scales. | structural MRI, various regional volumes (sub-cortical structures not included) | mixed model MANCOVA (multivariate analysis of covariance), encompassing effects at baseline, effects at the last MRI scan, as well as the effect of change between the two time points. The following characteristics was utilized: volume of each region was the dependent variable, while gender and group (poor vs good outcome, patients vs controls) were the between-subject factors. Age, interscan interval, sex and height were covariates. | Assessing longitudi-nal variation in MRI cortical volumes and their correlation with illness course (good versus poor outcome, defined by symptom recurrence) | Clinical assessments classified 64% of patients in the good outcome group and 36% in the poor outcome group. MANCOVA identified the following effects: There was no significant difference in baseline total ventricular volume between poor outcome and good outcome patients (F = 0.01, p = 0.92). There was a significant group-by-time interaction (F = 5.10, p = 0.0089). The ventricles of poor outcome patients increased in volume, something that did not occur in the good outcome group. Post-hoc comparisons of change scores in ventricular volume between poor and good outcome groups revealed a significant difference (F = 9.69, p = 0.0028). | Ventricular enlargement was significant in patients who did not respond to treatment, or relapsed during follow-up, compared to patients who achieved maintained remission. These structural changes in time could be associated with the presence and persistence of SCZ symptoms. | |

| de Castro-Manglano et al., 2011 (41) (Spain) | Prospective (regarding clinical follow up, however, only 1 MRI scan was performed) | n = 28 patients (SCZ and affective disorders, ICD-10 F20 and F30-39) | Baseline structural MRI scan. Each voxel represented the average amount of local grey (GM) or white matter. Clinical assessment was performed at baseline and after 3 years, via PANNS, HDRS, CGI and other scales. | >structural MRI, grey matter (GM) volume | two-sample t-test at baseline between patients with poor outcome versus good outcome (no apparent remission of symptoms, continuous hospitalization, unemployment) | >Compar-ing GM values between patients with good versus poor outcome. | two-sample t-test showed that the GM volume, specifically in the right hippocampus, was lower in the group of patients with poor outcome. (Z = 4.42, p < 0.001, uncorrected) | Lower Grey Matter volume in the right hippocampus was correlated with poorer outcome and thus could be associated with acute relapse in chronic patients. | |

| Yamadar et al., 2013 (42) (USA) | Cross sectional | n = 86 patients (DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders), divided into three groups: 13 FEP, 27 relapsed, 46 chronic stable | SORT (Semantic association retrieval task), where a pair of words is presented, that either elicits a third word (retrieval trial) or does not (non-retrieval trials). An example is the word pair “honey and “stings” which triggers the word “bees”. For the sort task, subjects completed a total of 92 trials (46 retrieval, 46 non-retrieval), while getting the fMRI scan. | >Accuracy (correct classifica-tion of retrieval or not) and reaction time in the SORT behavio-ral task. fMRI scan | Accuracy, defined as the correct number of responses for retrieval over the total number of retrieval trials, summed with the correct number of responses for non-retrieval over the total number of non-retrieval trials, was analyzed with a 2-condition (Retrieval, No-Retrieval) x 4-group mixed ANOVA. Reaction time (RT) was analyzed with a 2-accuracy (hit, miss) x 2-condition (Retrieval, No-Retrieval) x 3-group mixed ANOVA. Group differences were further evaluated (pairwise post-hoc comparisons). Contrast values in fMRI were obtained by creating spherical regions of interest around peak activity. | >Assessing differe-nces in a behavioral paradigm between FEP, chronic stable, and relapsed patients and simulta-neous alterations in inferior parietal lobule (IPL) activation in fMRI. | Mixed ANOVA for accuracy showed no differences between any of the SCZ groups (all p > 0.774). Mixed ANOVA for RT showed significantly faster RT ins the FEP and chronic stable groups when compared to the relapse group. (p < 0.01 and p= 0.016) Regarding fMRI data, left and right IPL activity was not significantly different between any of the SCZ groups. (left IPL: all p > 0.304, right IPL: all p > 0.699) | While fMRI activity in the left and right inferior parietal lobules has been shown to correlate with symptom severity (PANNS scores), it did not present any characteristic differences in relapsed patients, compared to first episode, or chronic stable patients. Regarding behavioral data, while accuracy did not correlate with group, RTs were significantly longer in the relapse group compared to both other groups, indicating that RT could be a useful metric in relapse identification. | |

| Nieuwenhuis et al., 2016 (43) (Nether-lands, UK, Brazil, Australia, Spain) | Prospective (regarding clinical follow up, however, only 1 MRI scan was performed) | n = 389 patients from multiple centers (SCZ spectrum). Of those, only those with a continuous or remitting illness course were included in the study (n = 212). | baseline structural MRI scan, calculation of spatially normalized grey matter probabilities Clinical follow-up for 3-7 years (multi-center study) | >structural MRI, grey matter (GM) probabili-ty in each of 170000 voxels per subject | A support vector machine (SVM) classifier was used to distinguish between patients with a continuous and patients with a remitting course of illness. Classification accuracy was evaluated via calculation of the positive and negative predictive accuracy. | >Classify-ing individuals into groups of different illness courses using machine learning (SVM) on baseline MRI scan data. | When including data from all centers, the classification accuracy did not differ from chance level. (52% positive and 52% negative predictive accuracy). When examining data from each center individually, the classification was significantly more accurate than chance level (68% PPA, 70% NPA, p < 0.02, p< 0.007) in only one center (London, UK). | Classification of patients into groups of different illness course based on grey matter density was not more accurate than chance level in the multi-center analysis, while in the single-center analysis, classification accuracy reached significance in only one center. | |

| Kim et al., 2020 (44) (Korea) | Prospective (2 PET scans, before and after discontinua-tion of medication) | n = 25 patients (DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, FEP) | [18F]DOPA PET scans at baseline and after 6 weeks (i.e. two weeks after the 4 week medication discontinua-tion process). A [11C]raclo-pride PET scan was performed a week after the second [18F]DOPA PET scan. Clinical follow-up for up to 12 weeks, via PANNS, BPRS. | >[18F]DOPA PET and A [11C]raclopride PET scans, influx rate constants (Ki[cer] (l/min)) relative to the cerebel-lum, tracer binding potential (BP[ND]) to dopamine D2/3 receptors in the striatum | Linear mixed effects model to test the effect of group on Ki[cer] and BP[ND]. Group, modeled as a categorical variable: 1 =healthy controls, 2 = patients without relapse, 3 = patients with relapse) and the time point of PET imaging were modeled as fixed effects, and subjects were modeled as random effects. Pearson correlation between baseline Ki[cer] and the time to relapse. | >Examining longitudi-nal changes in Ki[cer] and BP[ND] values obtained from PET scans and their differe-nces between patients who relapsed versus those who did not. | Linear mixed effects models yielded a significant group by time effect for changes in Ki[cer] values between the three groups. (Week*Group: F = 4.827, df = 2,253.193, p = 0.009). Ki[cer] values were not significantly different among groups at baseline (F = 0.467, df = 2,211.080, p = 0.628), but were at week 6 (F = 3.512, df = 2,202.165, p = 0.032) Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between Relapse and Non-relapse (p = 0.043) and between healthy controls and Non-relapse (p = 0.019), but not between Relapse and healthy controls (p = 0.854). In the Relapse group, a significant negative correlation was observed between baseline Ki[cer] values and time elapsed until relapse (R squared = 0.518, p = 0.018). No differences were observed in BP[ND] among the three groups (F = 1.402, df =2,32.000, p = 0.261). | Changes in striatal dopamine levels were found to correlate with psychotic relapse, and the time elapsed until it occurred. These results point at aberrant dopamine autoregulation as a contributing factor for psychotic relapse. | |

| Mi et al., 2021 (45) (China) | Cross sectional | n = 32 patients (SCZ, DSM-IV or V) | EEG acquisition, while subjects performed a double oddball paradigm, with da/as the frequent stimulus and ba/and du/as the deviant ones, eliciting the consonant and vowel Mismatch Negativity respectively. Clinical outcomes were assessed retrospecti-vely based on previous interviews (PANNS, GAF). | >EEG, vowel and conso-nant induced phonetic Mismatch Negativity (MMN) | Pearson correlation between phonetic MMN reduction in 9 channels (F3, Fz, F4, FC3, FCz, FC4, C3, Cz, C4) and illness relapse. | >Correla-ting phonetic MMN amplitude with illness relapse (hospitali-zations, medica-tion dosage increase of 25% or more, suicidal ideation) | For the consonant induced MMN (da-ba) there was no significant correlation in any of the 9 electrodes with illness relapse (all p > 0.18). For the vowel induced MMN (da-du) significant differences were found in 6 of the 9 electrodes. F3: r = 0.428, p = 0.015//Fz: r = 0.420, p = 0.017//FC3: r = 0.435, p = 0.013//FCz: r = 0.380, p = 0.032//FC4: r = 0.370, p = 0.037//C3: r = 0.367, p = 0.039. | Significant correlations between vowel phonetic MMN amplitude and illness relapse, implicate automatic speech processing deficits as a potential contributor in relapse occurrence. | |

| Solanes et al., 2022 (46) (Spain) | Prospective (regarding clinical follow up, however, only 1 MRI scan was performed) | n = 277 patients (SCZ, SAF, Bipolar Disorder and other)/120 HC | Structural MRI at baseline (T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence). Clinical assessment for up to 24 months, or until relapse, defined via PANNS. | >structural MRI image | Data was segmented into a train set, to obtain model parameters and a test set, for which relapse was predicted. Lasso regression was utilized, and each parameter value was multiplied by the corresponding variable value for each individual. After obtaining the sum of these terms, if the result was <= 0, the individual was classified as low risk for relapse, and if it was >0, as high risk. To test classification accuracy, a mixed-effects Cox proportional hazards regression model was used. | >Using machine learning to classify individuals into two groups, correspo-nding to low and high risk of relapse, based on baseline MRI images. | 16 relapses were recorded (9.4% relapse rate in 24 months), corresponding to 70% statistical power to detect a Hazard Ratio of 4.3. Lasso regression selected the following key variables: diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, lack of difficulty in abstract thinking and poor impulse control, and the increase or decrease of unmodulated and modulated gray and white matter in several brain regions. Cox regression resulted in a Hazard Ratio of 4.58, meaning that patients in the high risk group had almost 5 times more risk to relapse. This result reached statistical significance. (Hazard Ratio 95% confidence interval = 1.01–20.74, Z = 1.98, p = 0.048) | While a model using combined clinical and MRI parameters did classify low vs high risk for relapse, that was not possible with the sole use of MRI data. Furthermore, issues of statistical power arose in the study, given the low number of relapse events recorded. To sum up, evidence from this study suggests that MRI could combine with clinical follow-up, resulting in more precise risk stratification for psychotic relapse. | |

| Sasabaya-shi et al., 2022 (47) (Japan) | Prospective (regarding clinical follow up, however, only 1 MRI scan was performed) | n = 52 patients (SCZ, according to ICD-10)/19 relapsed - 33 did not relapse | Structural MRI at baseline. Calculation of the local gyrification index (LGI), which refers to the cortical “folding”, or the amount buried within troughs of the cortex, in 800 regions of interest. Clinical assessment for up to 3 years, or until relapse. | >structural MRI image, Local gyrifica-tion index (LGI) | Group differences were assessed via one-way ANOVA or the chi-squared test. Monte Carlo simulations were run to perform multiple comparisons (10000 iterations for each comparison). p < 0.05 defined significant clusters. | >Compar-ing LGI values across 800 regions, between the group of patients who relapsed and those who did not. | The relapse group exhibited a significantly higher LGI in 3 clusters with sizes (in mm^2) of 4022.36, 707.22, 646.85. The first cluster (p = 0.0001) corresponded to the left precuneus and cuneus cortex, isthmus cingulate gyrus, pericalcarine cortex, and lingual gyrus. The second cluster (p = 0.0161) corresponded to the left superior parietal lobule. The third cluster (p = 0.0328) corresponded to the right precuneus cortex, posterior and isthmus cingulate gyrus. | Significant differences in LGI between the relapse and non-relapse groups across various regions, could hint at neurodevelopmental anomalies in the pathogenesis of psychotic relapse. | |

| Rubio et al., 2022 (48) (USA) | Cross sectional | n = 50 patients (SCZ, SAF, Bipolar Disorder I and others, according to DSM-IV. Patients were split into the Break-through Psychosis group (BAMM: breakthrough on antipsychotic maintenance medication) consisting of 23 individuals and the Antipsychotic free group (APF, relapse after voluntary discontinuation of treatment), consisting of 27 individuals | Approxima-tely 20 minutes of resting state (awake, eyes closed) fMRI Calculation of the Striatal Connectivity Index (SCI), which involved measuring functional connectivity of subregions in the striatum, creating connectivity maps and extracting the strength in 91 of those connections to obtain the SCI. (single value per scan, or per participant) | >resting state fMRI, Striatal Connecti-vity Index (SCI) | Linear regression model, with group status (Breakthrough psychosis, psychotic relapse after discontinuation of medication, healthy controls) as the independent variable, SCI as the dependent variable and sex and age as covariates. Post hoc analysis (re-run of the same model), including only SCZ and SAF diagnosis. | >Examining differen-ces in the SCI between acutely relapsed patients and controls, as well as differences between patients who relapsed despite continuation of mainte-nance treatment and those who relapsed after disconti-nuation of treatment. | Group comparisons for the entire patient group yielded the following results: SCI values were significantly lower in the BAMM group than in the APF patient group as well as the HC group. (APF: Cohen’s d = 0.58, linear regression: ß = 0.86, p = 0.032, HC: d = 0.99, linear regression: ß = 1.47, p < 0.001). When comparing APF to HC there was a trend toward lower values in the APF group, that did not reach the p < 0.05 significance level. (Cohen’s d = 0.44, linear regression: ß =0.61, p = 0.09). Post hoc analysis including only SCZ and SAF patients resulted in the same significant difference between BAMM and HC (p < 0.001), only now both the trend differences between BAMM and APF, as well as APF and HC, did not reach significance. (p = 0.07 and p = 0.08 respectively) | This study provides evidence that striatal functional connectivity could be impaired (lower SCI value) in individuals experiencing psychotic relapse. Differences in SCI values were significantly more prominent for the group of patients who relapsed despite guaranteed continuation of antipsychotic treatment, which could hint at SCI as a marker of treatment non-response. | |

| Odkhuu et al., 2023 (49) (Korea) | Prospective (regarding clinical follow up, however, only 1 fMRI scan was performed) | n = 30 patients (SCZ spectrum or other, DSM-IV, recovered at recruitment). Patients were split into two groups, those who relapsed and those who did not | 5 minutes of resting state fMRI Calculation of functional connectivity (FC) matrices, to obtain the Global FC strength (mean of all pairwise correlation coefficients) Clinical follow-up every 2 months for 1-2 years, via PANNS, SOFAS and the Calgary Depression Scale for SCZ. | >resting state fMRI, Global Functio-nal Connecti-vity strength (GFC) | one-way ANOVA for group differences in GFC between patients and healthy controls (first comparison) and relapsed patients, relapse free patients and healthy controls (second comparison). | >Compa-ring GFC values between chronic patients and controls, as well as within the patient group, between individuals who relapsed and those who did not. | Regarding patient- HC differences in GFC, the ANOVA showed that GFC was significantly higher in patients (patients: 0.240 ± 0.035, HC: 0.223 ± 0.028, p < 0.0001). ANOVA for relapsed and relapse free patients showed a significantly higher GFC in relapsed patients (Relapse: 0.290 ± 0.040, Non-relapse: 0.216 ± 0.039, p = 0.0002). For relapsed patients and controls the same significant difference was observed. (Relapse: 0.290 ± 0.040, HC: 0.223 ± 0.028, p < 0.0001). Comparison of the non-relapse group with HC did not yield significant differences. | The results of this study implicate global metrics in baseline resting state fMRI as state markers for relapse, since GFC values were found to differ significantly in the group of patients who subsequently relapsed, compared to both patients who achieved prolonged remission and healthy controls. | |

Main points regarding sample, methodology, analysis, and results for papers examining neuroimaging/neurophysiology biomarkers.

Table 7

| Study/Country | Study Design | Sample (Diagnosis) | Data Collection Process | Biomar-kers examined | Analysis Tools | Main objectives | Statistical Results | Synthesis of main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al.2005 (50) (Hong Kong) | Prospective (2 cognitive assess-ments, at admission and after stabilization, clinical follow-up for 3 years) | n = 93 patients (SCZ, SAF, Schizophreniform disorder according to DSM-IV) | Cognitive assess-ments at admission and after stabilization included the forward digit span test, the Logical Memory test, the Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and a semantic fluency test. Clinical follow-up every 4 months for 3 years via PANNS. | >Various cognitive factors | A multiple binary logistic regression model was used with relapse (categorical, 0 or 1) as the dependent variable and standardized Z-scores for cognitive function scores as independent variables. | >Examining whether scores in various cognitive tests related to memory, sematic association and executive function could predict the occurrence of relapse in a 3-year follow-up period. | 40% of patients relapsed within the full 3 year follow-up period. (21% and 33% for years 1 and 2) In the multiple logistic regression model, only the preservative error in the Wisconsin test yielded a significant odds ratio of 2.46 (p = 0.027). | While both visual and verbal memory, as well as semantic fluency were not significantly associated with relapse, executive dysfunction as assessed by the Modified Wisconsin Card Sorting Test could be a predictor of adverse outcomes in SCZ. | |