- 1Rocky Mountain Mental Illness, Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) for Suicide Prevention, Rocky Mountain Regional Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Aurora, CO, United States

- 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 3Steve Hicks School of Social Work, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

- 4Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

- 5Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States

- 6Veterans Affairs (VA) Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention, Veterans Affairs (VA) Finger Lakes Health Care System, Canandaigua, NY, United States

- 7Department of Psychiatry, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

- 8Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 17 Clinical Resource Hub, Texas Valley Costal Bend Veterans Affairs (VA), Harlingen, TX, United States

- 9Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Affairs (VA) Central Office, Washington, DC, United States

- 10Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, United States

- 11Research and Development Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX, United States

- 12Department of Psychology, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, United States

- 13Suicide Prevention Center of New York, Albany, NY, United States

- 14Zero Suicide Institute Faculty, Education Development Center, Waltham, MA, United States

- 15Division of Prevention and Community Research, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 16Booz Allen Hamilton, Arlington, VA, United States

- 17Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, Houston, TX, United States

- 18Central Texas Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, Temple, TX, United States

- 19Veterans Affairs (VA) Portland Health Care System, Portland, OR, United States

- 20Veterans Affairs (VA) Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Aurora, CO, United States

- 21Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans, Waco, TX, United States

- 22Department of Psychiatry, Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States

The majority of Veterans who died by suicide in 2021 had not recently used Veterans Health Administration (VA) services. A public health approach to Veteran suicide prevention has been prioritized as part of the VA National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide. Aligned with this approach, VA’s Patient Safety Center of Inquiry—Suicide Prevention Collaborative piloted a Veteran suicide prevention learning collaborative with both clinical and non-clinical community agencies that serve Veterans. The VA COmmunity LeArning CollaboraTive (CO-ACT) uses a quality improvement framework and facilitative process to support community organizational implementation of evidence-based and best practice suicide prevention strategies to achieve this goal. This paper details the structure of CO-ACT and processes by which it is implemented. This includes the CO-ACT toolkit, an organizational self-assessment, a summary of recommendations, creation of a blueprint for change, selection of suicide prevention program components, and an action plan to guide organizations in implementing suicide prevention practices. CO-ACT pilot outcomes are reported in a previous publication.

Introduction

An average of 17.5 Veterans died by suicide daily in 2021 (1). Of these Veterans, 61.9% had not used Veterans Health Administration (VA) services in 2020 or 2021 (1). Thus, Veterans not using VA services are a critical subgroup to target in suicide prevention efforts.

VA has developed and implemented a multicomponent suicide prevention program that is unmatched by other healthcare system in the public or private sectors (2–5). In particular, VA has transitioned to implementing a public health approach to suicide prevention that calls on VA and non-VA clinical and community organizations to implement suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention services, as detailed in the VA’s National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide (6).

The National Strategy (6) describes four pillars of suicide prevention: 1) Healthy and Empowered Veterans, Families, and Communities, 2) Clinical and Community Preventive Services, 3) Treatment, Recovery, and Support Services, and 4) Surveillance, Research, and Evaluation. VA implemented a new national initiative with these pillars in mind, namely, Community-Based Interventions for Suicide Prevention (CBI-SP). Through the CBI-SP initiative and embracing collaborations with community partnerships, VA has expanded its capacity to prevent suicide among Veterans not connected to VA care. The CBI-SP model encourages establishing community-based suicide prevention coalitions that target priority areas aimed at increasing: 1) identification of Veterans and family members within the community and increasing screening for suicide risk; 2) connectedness within the community and during improved care transitions; and 3) community-wide lethal means safety and safety planning.

Aligning with the CBI-SP initiative, the VA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry for Suicide Prevention (PSCI-SPC), a national suicide prevention research center sponsored by the VA National Center for Patient Safety, developed and tested the VA COmmunity LeArning CollaboraTive (CO-ACT). CO-ACT employs a learning collaborative model as one method to engage and partner with clinical and nonclinical community organizations to expand suicide prevention programming (7, 8). Prior literature details a collaborative learning model developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, known as the Breakthrough Series (9). This model provides a structured and time-limited process (6- to 16-months) for healthcare organizations to learn from each other and subject matter experts. Participating teams then utilize quality improvement methods to translate that knowledge into action at their respective organizations. The Zero Suicide Institute also uses a learning collaborative method to assist organizations in implementing the Zero Suicide Model (10, 11). However, suicide prevention learning collaboratives beyond Zero Suicide are limited, and none target preventing suicide among military Veterans, a population with substantially higher suicide rates than non-Veteran adults. In 2021, after adjusting for sex and age, the rate of Veteran suicide deaths was 71.8% greater than non-Veteran adults (1).

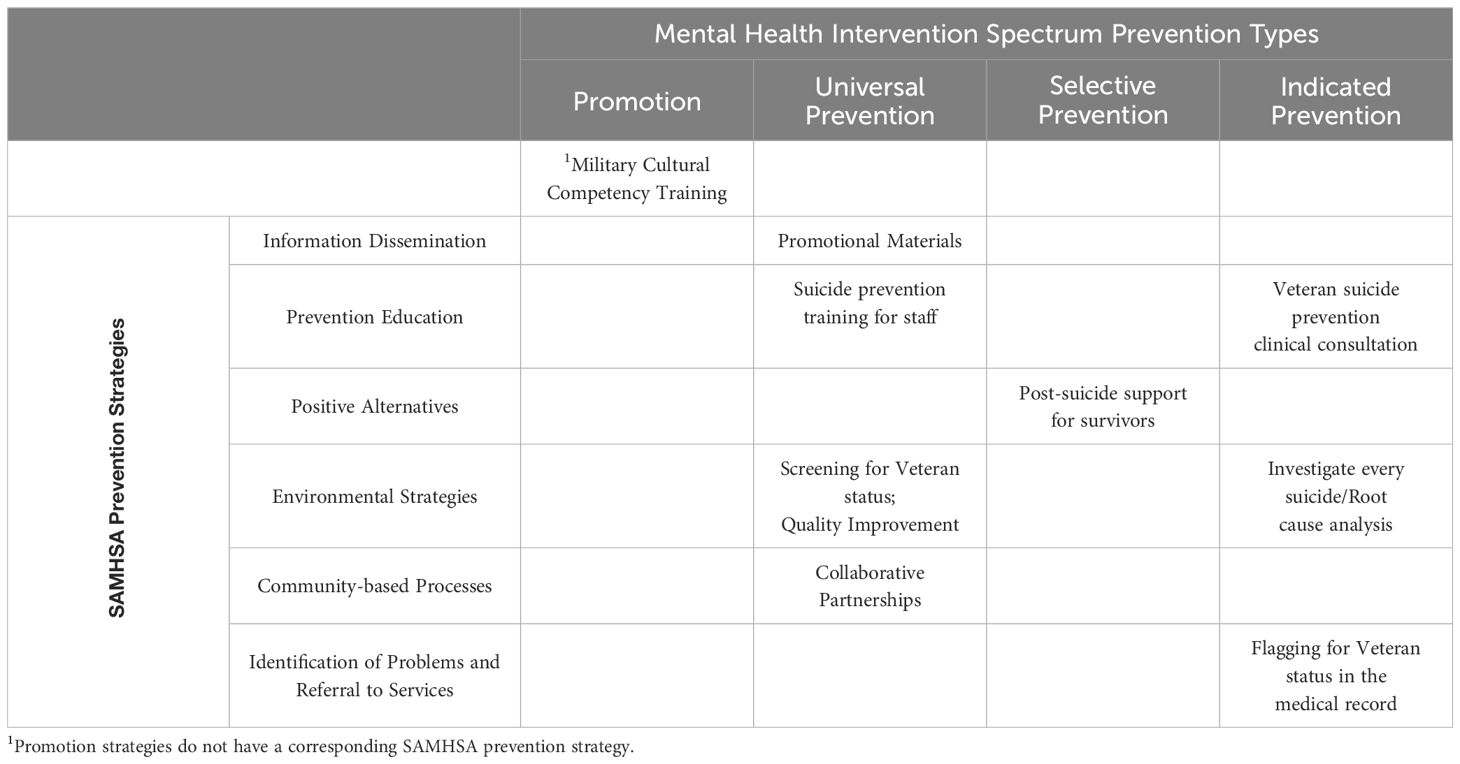

The CO-ACT suicide prevention learning collaborative draws heavily from existing prevention models. Namely, the Mental Health Intervention Spectrum is rooted in the National Academy of Medicine’s (formerly named Institute of Medicine) prevention model and outlines strategies from promotion to recovery (12–14). While the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) prevention classification system was originally created to target substance misuse, it’s use is applicable to suicide prevention efforts (15). Using a Veteran suicide prevention lens, the learning collaborative focused on Promotion and Prevention strategies (12, 13, 16). Promotion efforts broadly target the general public. Prevention is divided into three stages that target increasingly specific populations through strategies that include: universal prevention (e.g., targets the general population, such as through suicide prevention awareness and education), selective prevention (e.g., targets individuals at increased risk for suicide), and indicated prevention (e.g., targets individuals at high risk for suicide due to a past suicide attempt or current suicidal ideation; 13).

CO-ACT utilizes the integrated—Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework (17). i-PARIHS framework identifies three components as key to successfully implement evidence-based and best practices: context, recipients, and the innovation. Considering these key components prior to initiating implementation can increase the likelihood of success. Context refers to the work setting in which implementation will occur and relates to multiple levels (i.e., local, organizational, external health system). An innovation that does not fit into a clinic’s ongoing workflow is unlikely to be successfully implemented. The recipient refers to the individuals impacted by implementation at the individual and collective team levels. Recipients must understand the implementation and be able to implement the innovation into practice. For example, if a selected implementation requires independently licensed providers, the recipients implementing it must be clinically licensed. The innovation is the specific practice or change the team aims to implement and should be clearly defined and provide an advantage over current practices. Receptivity to implement an innovation is impacted both by evidenced-based and practice-based knowledge. Harvey and Kitson (2015) described how the compatibility of a proposed change can be enhanced by “aligning external explicit evidence [for an innovation] with local priorities and practice…” (p. 4) (17). Attending to these three key components can facilitate rapid implementation by preventing stuck points and improving the likelihood of implementation success.

CO-ACT has four aims: 1) create sustained organizational change so that organizations can adequately respond to Veteran suicide risk; 2) provide technical assistance, support, and education in building a suicide prevention program within community organizations; 3) build relationships and collaborations between the VA and community organizations to support suicide prevention; and 4) build relationships between community organizations to strengthen a Veterans suicide prevention safety net in the community. From 2020–2021, CO-ACT was pilot tested with clinical and non-clinical organizations across the broader Denver and Colorado Springs, Colorado region. The aim of the current paper is to detail CO-ACT’s structure and processes. In doing so, the authors seek to increase knowledge of mechanisms of learning collaboratives for Veteran suicide prevention, specifically methods that facilitate rapid implementation of needed Veteran suicide prevention strategies into community organizations.

Context for an initial test of a suicide prevention learning collaborative

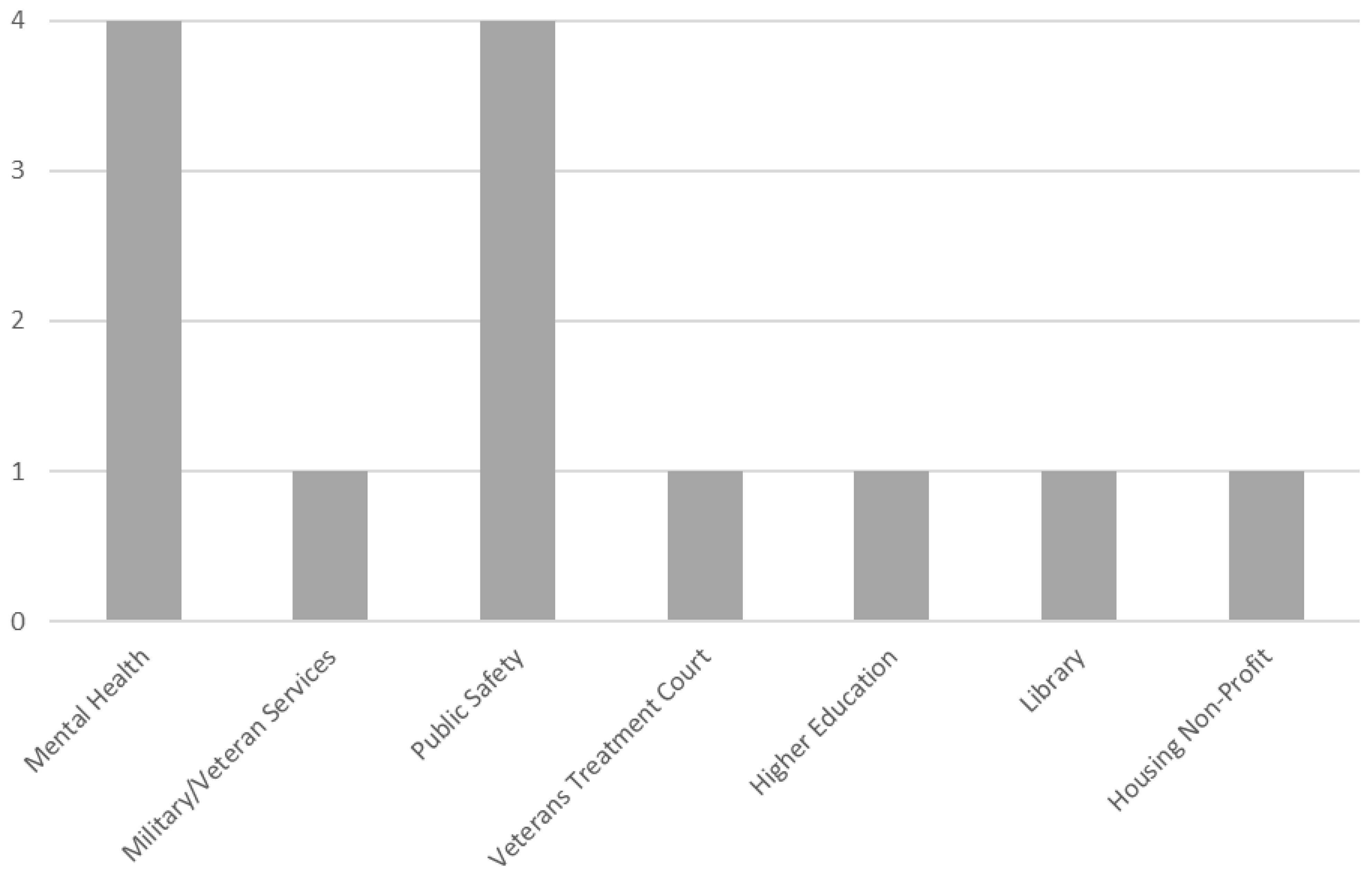

Colorado has notably high rates of suicide. In 2021, Veterans in Colorado had a significantly higher rate of suicide compared to the national Veteran suicide rate and the national general population suicide rate (1). To expand and improve upon existing suicide prevention efforts across the state in its pilot test, CO-ACT employed community mapping to understand the landscape of community organizations serving Veterans in the greater Denver area and support organization recruitment. Further, snowball recruitment was used to identify and invite other clinical and non-clinical organizations serving Veterans to participate. Local VA and community leaders provided recommendations and/or connected the CO-ACT team to these potential organizations. In 2020, 13 clinical and non-clinical community organizations were invited and participated in a pilot test of CO-ACT. Five of these organizations provided mental health services to Veterans and/or Military Service Members, while the remaining eight provided non-healthcare services [see Figure 1 for additional details, as reported in DeBeer et al., 2023b (8)]. At the discretion of each organization, each organization’s team size ranged from one to four members.

Figure 1 Types of organizations in CO-ACT learning collaborative pilot (8).

Essential program components of CO-ACT: suicide prevention learning collaborative

CO-ACT was adapted for delivery using an entirely virtual learning collaborative (i.e., videoconference calls via Zoom™ and Microsoft Teams™) following early COVID-19 pandemic in-person meeting restrictions. CO-ACT occurred over 16 months, and consisted of 6 quarterly collaborative group meetings and 15 monthly individual organizational team facilitation calls. Implementation activities were guided by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) model (9), existing prevention models, and suicide prevention programs/frameworks (6, 11, 18–24). The iPARIHS framework (17), in conjunction with Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (25), guided implementation and quality improvement planning and action.

CO-ACT toolkit and program components

Program Components (i.e., the specific suicide prevention programming practices teams select to implement at their respective organizations) included suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention service options identified in one or more of four existing and prominent Veteran, active military, or civilian suicide prevention suicide prevention programs or models. Namely, these programs/models comprised of the Department of Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Program (6, 18), the Defense Suicide Prevention Program (DoD) (20, 21), the Zero Suicide program (11, 22), and the Division of Violence Protection National Center for Injury Prevention and Control-Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention program (23, 24). These four suicide prevention programs/models were compared to identify all possible suicide prevention strategies beneficial to VA and community suicide prevention programming (2). Once all distinct program components were identified, similar strategies were combined and re-defined to ensure integrity of the original definition.

This resulted in a comprehensive list of the suicide prevention program components detailed in the CO-ACT toolkit. Each program component was categorized according to two existing prevention frameworks. Specifically, the Mental Health Intervention Spectrum (adapted from the National Academy of Medicine Continuum of Care Model (12–14, 16) and the SAMHSA Prevention Model (15). The intent with labeling each program component according to these frameworks was to assist organizations in understanding the spread of their program components over different types of prevention. Consistent with Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model, prevention practices are strongest when they are spread over multiple types (26, 27).

Program components were also categorized as either a best practice or an evidence-based practice (28–33). Best practices are generally accepted treatments, techniques, or methods by health care experts that are used by professionals as appropriate treatments for certain disorders that have proven helpful over time and that are conferred as being measurable, replicable, and notably successful (31, 33), In contrast, an evidence-based practice is one that has undergone scientific evaluation to validate its effectiveness and which is recognized in peer-reviewed scientific journals (28–33).

Each program component in the CO-ACT toolkit was labeled according to the Zero Suicide classification to assist teams in determining how practices implemented through CO-ACT fit with the Zero Suicide framework (11). Zero Suicide categorizes suicide prevention components as: Lead (i.e., interventions promoting suicide prevention at a systems level), Train (i.e., training staff to promote high quality care services), Identify (i.e., identifying those at risk using a screening tool), Engage (i.e., using suicide care management plans for those at risk), Treat (i.e., using evidenced-based treatments and other best practices to reduce risk), Transition (i.e., using best practices for care coordination to ensure the Veteran remains connected to services), and Improve (i.e., using quality improvement to continually improve suicide prevention practices) (11).

Procedures

Pre-collaborative assessment

After agreeing to participate in CO-ACT, each member organization completed an organizational self-study and interview. Specifically, each organization completed a modified Zero Suicide survey focused on identifying each organizational structure and existing Veteran suicide prevention practices (11). These data were used to inform a follow-up hour-long individual interview aimed at providing the VA CO-ACT facilitation leads with a fuller picture of each organization’s existing structure and suicide prevention program components. Together, this information was used to create a summary of specific Veteran suicide prevention component recommendations that each member organization could consider implementing in the near future.

Learning collaborative structure

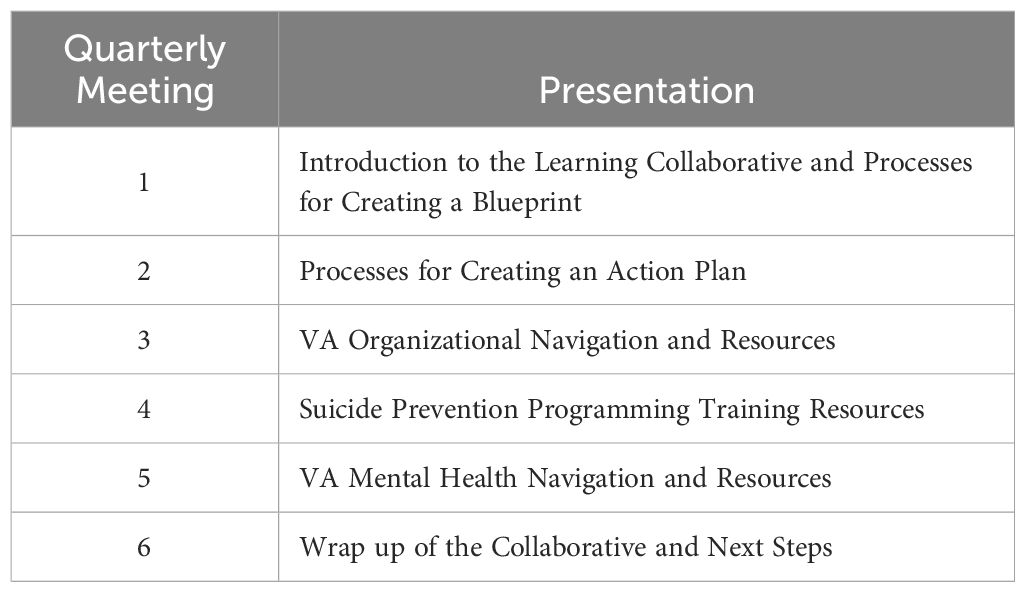

Following a 4-hour kick-off group meeting (see Table 1 for content of group quarterly meetings), each team participated in their first monthly 1-hour coaching call with VA CO-ACT facilitation leads. In this call, VA CO-ACT facilitation leads engaged each team in a collaborative review of information collected during the organizational self-study and interview. VA CO-ACT facilitation leads identified and prioritized potential suicide prevention program components for implementing over the course of the learning collaborative. Factors impacting selection and prioritization of program components included consideration of each organization’s current suicide prevention programming, along with its leadership interest and available resources. Priority was placed on implementing sustainable programming (e.g., having leadership approve a new training policy on suicide risk assessment practices regarding who is trained, how, and when before an organization initiates efforts to train staff), as well as a desire to have as large of an impact as possible on reducing Veteran suicide. This information was used to develop each team’s Blueprint (i.e., a roadmap used to guide selection of the suicide prevention program components of interest to each organization) and Action Plan (i.e., detailed plan created to enhance the likelihood of implementation success; see Tables 2, 3).

Each team’s evolving Blueprint and associated Action plan were reviewed during monthly facilitation calls with the CO-ACT learning collaborative leader. Additionally, each organization provided brief updates about these materials during the second through the sixth quarterly group learning collaborative meetings. Quarterly group meetings were also used to educate members about numerous areas associated with Veteran care and suicide prevention. Topics covered can vary between CO-ACT cohorts, as the learning collaborative leader is encouraged to add or remove topics to accommodate specific requests. The topics discussed during the initial pilot at quarterly group meetings are detailed in Table 1.

Following selection of program components to implement, each CO-ACT team considered how implementation success could be impacted by the context, innovation, and recipient, as defined by iPARIHS model (17). PDSA cycles provided a model to guide a continuous approach to quality improvement efforts (25) that allowed for ongoing revisions to each PDSA cycle, until a practice is well-integrated into an organization’s operations. This quality improvement approach facilitates a process to assist teams in breaking down larger implementations into manageable tasks.

CO-ACT quality improvement process

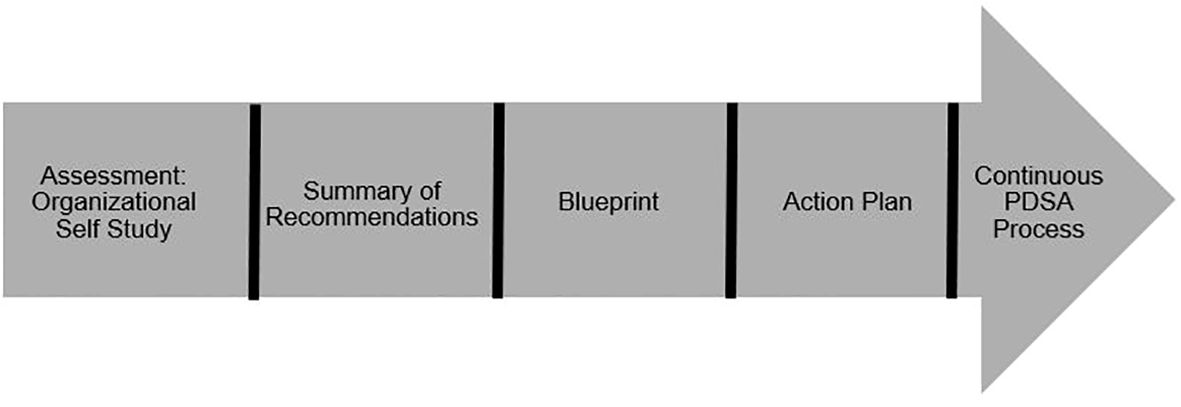

Figure 2 depicts the CO-ACT 5-step process to facilitate rapid implementation of Veteran suicide prevention in partner organizations. Each step in this process is described in detail below.

Step 1: assessment: organizational self-study and interview

As previously mentioned, all teams were required to complete an organizational self-study survey and an interview prior to the start of CO-ACT. The organizational self-study was modified from Zero Suicide to be specific to Veteran suicide prevention (11, 22). The survey consists of questions regarding the functions of the organizations and populations served. Additionally, it assesses information regarding each organization’s current Veteran suicide prevention programming and goals for participation in CO-ACT. The interview following the survey provided an opportunity for the VA CO-ACT facilitation leads to review the organization’s current programming, relationship with the VA, and relationship with other collaborative organizations.

Step 2: summary of recommendations

After completing the organizational self-study and the interview, CO-ACT leads reviewed the results and organized them into a summary of recommendations. The learning collaborative leader sought to understand the population served by the organization, paying particular attention to how much of that population is comprised of Veterans. Some organizations were Veteran-focused, serving only Veterans, whereas others served much smaller concentrations. This information influenced how implementation was approached at each organization. The VA CO-ACT facilitation leads reviewed practices and identified gaps in the organization’s Veteran suicide prevention programming, then collaboratively worked with each organizational team to determine the top three areas of Veteran suicide prevention to begin implementing best practices and/or evidence-based practices.

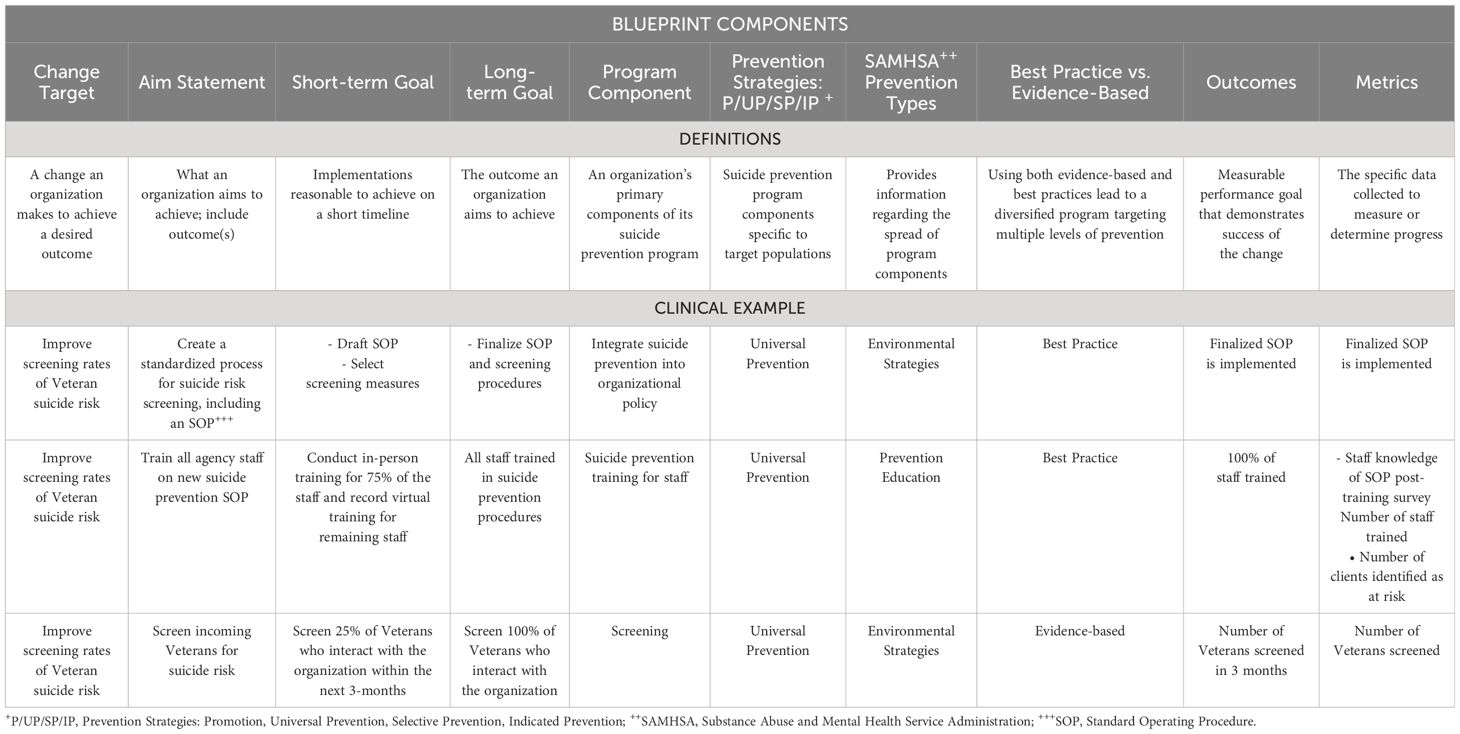

Step 3: Blueprint

Each organization’s team built a Blueprint for change (see Table 2 for an illustrative Blueprint of an organization that delivers mental health services) that is subsequently enacted using an action plan. A Blueprint provides a roadmap to guide what suicide prevention programming components an organization implements, whereas the Action Plan details how to enact the Blueprint, similar to a project management plan. A Blueprint consists of a change target, aim statement, necessary tasks in preparation for implementing suicide prevention programming, short- and long-term goals, outcomes, and metrics. A change target, which refers to the change that the team makes to improve the desired outcome at their organization, may have one or multiple sub-component implementations connected to it (9). The aim statement is a succinct and measurable statement about what the organization aims to accomplish and for which specific population, and identifies the outcomes to be assessed. Teams were encouraged to regularly revisit their aim statement to prevent project drift, and as needed, to revise or refocus this statement while implementing changes. Both short- and long-term goals were identified and defined to reflect actions with a specified target completion date (9). Teams were encouraged to identify goals believed to be most effective in producing intended results (i.e., see “Program Component Selection” section below). Short-term goals can typically be completed in 1 to 3 months, while long-term goals reflect an end state the organization aims to accomplish, usually in 12 to 16 months.

Program component selection

The VA CO-ACT facilitation leads assisted each team in selecting program components that best fit each organization. Consistent with the VA’s community-based suicide prevention priorities (6), each Co-ACT team was encouraged to consider the top three aforementioned Veteran suicide prevention program components: 1) identifying service members, Veterans, and their families and screening for suicide risk, 2) promoting connectedness and improving care transitions, and 3) increasing lethal means safety and safety planning. Teams were asked to consider both the level of involvement their respective organizations have with at-risk Veterans and were asked questions about feasibility (e.g., access to necessary resources) to assist in selecting strategies best suited for their organization. For example, while mental health organizations may find evidence-based treatments and tools to assess for suicide risk a priority for their practice, organizational leaders providing services to Veterans outside of health care may find strategies such as providing promotional materials and training staff in military cultural competency the best fit.

Teams were asked to define and track intended outcomes of newly implemented suicide prevention practices. While the ultimate outcome was to reduce Veteran suicide deaths, measuring this outcome as a result of implementing any one suicide prevention practice is difficult due to the rarity of the event within a single organization. Consequently, other implementation-related outcomes (e.g., number of patients assessed for Veteran status, number of providers trained in suicide prevention and lethal means safety) provided means for tracking implementation metrics and suicide prevention outcomes.

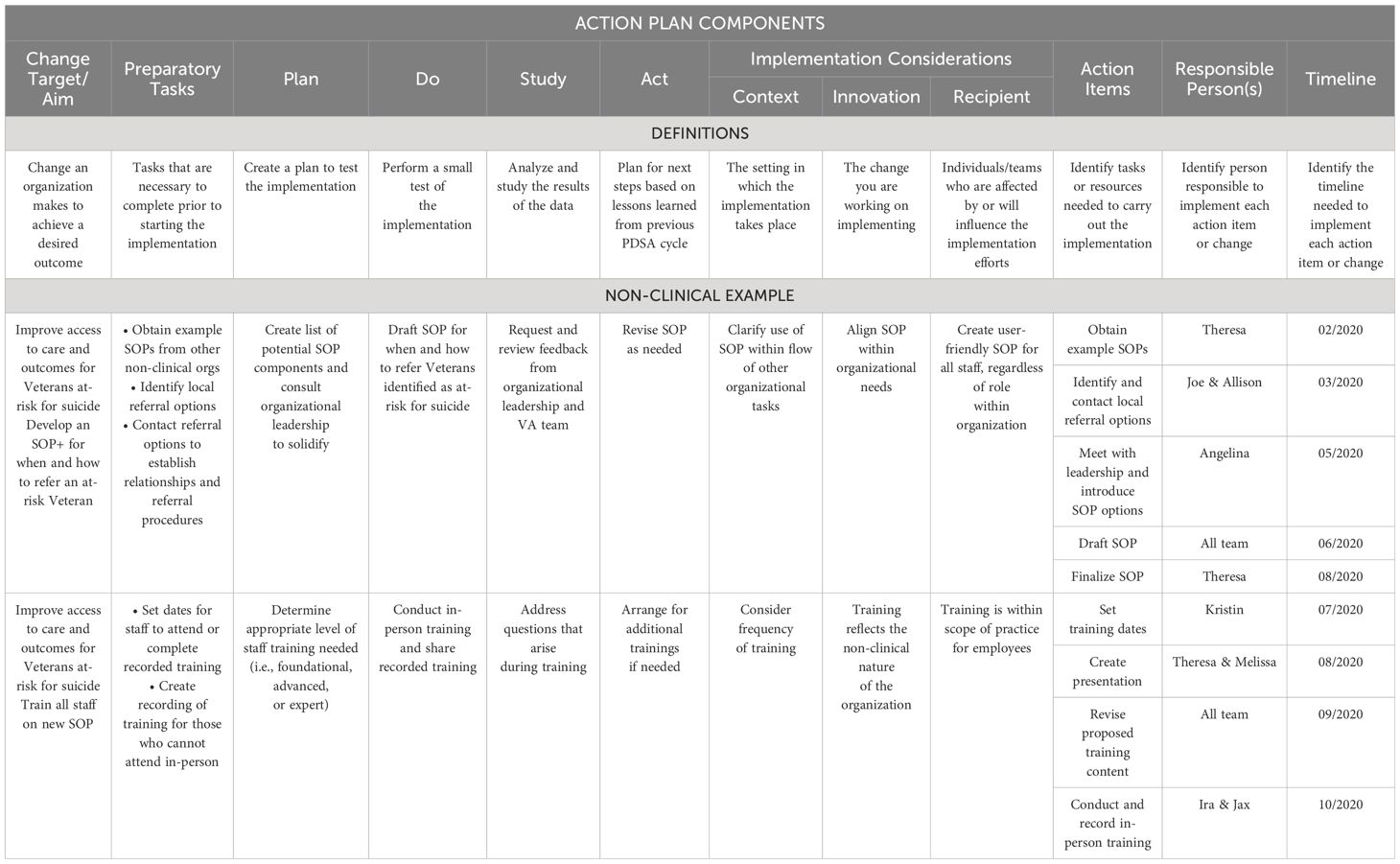

Step 4: action plan

After creating the Blueprint, each team worked to build the Action Plan. The Action Plan provided a project management plan to focus organizational efforts in rapid implementation of the identified change target (see Table 3). The Action Plan starts with the same change target and aim identified in the Blueprint, then a PDSA cycle is used to plan subsequent implementation activities (25). A critical piece of the PDSA cycle is determining any preparatory-PDSA cycle tasks. For example, if a training is planned as one cycle, the organization needs to first determine the type of training they want to provide. In the PDSA cycle, the first step is the Plan. The team and learning collaborative leader worked together to create a plan to test the implementation (25). The second step is Do. In this step, a test of the implementation is conducted. In the third step, Study, results of the test are analyzed. In the final step, Act, lessons learned in implementation are used to plan for subsequent cycles. Oftentimes, each PDSA cycle results in further clarity regarding what should be done next. Clarity surrounding who is moving the work of the implementation forward and the timeline is key; when this is not clear, breakdowns in implementation can occur. The Action Plan provides space to determine who is responsible for each step during implementation, and completion dates are concurrently determined. Although timelines can vary, each action item is typically due within a month, corresponding to the next scheduled facilitation call.

Step 5: continuous PDSA process

Once organizations move through a PDSA cycle and successfully implement new suicide prevention programing, the organization will return to the Blueprint to determine which program component to implement next. Often, engaging in a PDSA cycle process brings to light additional program components to implement, which is encouraged in the spirit of creating an environment of continuous quality improvement. A matrix is used to map the diversity of an organization’s programming (see illustrative Matrix in Table 4). Once existing suicide preventing programing is mapped using this matrix, an organization can examine diversification of their programming to assist selection of what to implement next. For example, if an organization is using all universal prevention strategies that are community-based processes, the organization could consider implementing a different classification strategy, in order to promote a diversity of prevention strategies. This process reveals which types of prevention in each organization’s suicide prevention programming overlap, and which are different. Optimally, each organization implements a wide range of prevention strategies. However, organizations that do not provide clinical services will likely have fewer selective prevention and indicated prevention strategies.

Discussion

The current paper described the structure and processes of CO-ACT, a Veteran suicide prevention focused learning collaborative (7) that employs a quality improvement framework to enact a public health approach toward reducing suicide. CO-ACT uses a learning collaborative model (9) to implement best and evidence-based suicide prevention program practices applicable to Veterans (6, 11, 18–24) in community organizations providing clinical or non-clinical services to Veterans. By utilizing a continuous quality improvement process (i.e., PDSA cycles) (25) and the i-PARIHS model (17) to guide implementation efforts, this learning collaborative was designed to enact sustainable Veteran suicide prevention programming into community organizations (8). With this intention, priority was given to implementing programming that was likely to be sustained after the learning collaborative ended. For example, before implementing a training for staff in suicide risk assessment, a new training policy was first implemented on who should be trained, when, and how often staff should be retrained.

The format and structure of the learning collaborative allowed teams to have a framework from which to: 1) conceptualize the current state of their program; 2) determine how to move forward in building an internal Veteran suicide prevention program; and to 3) utilize existing internal and external resources to support a continuous quality improvement process. As reported in DeBeer and colleagues (2023), organizational teams found these processes to be acceptable and feasible, and facilitated significant implementation of suicide prevention programming across all partnering organizations (8). Further, as reported in DeBeer and Colleagues (2024), participating in CO-ACT resulted in an increase in the quantity and quality of relationships/partnerships between participating community organizations and the VA (34).

In contrast to how learning collaboratives typically focus on healthcare systems (9), the current collaborative included non-healthcare organizations. This was done to be consistent with the VA’s public health approach to suicide prevention (6), reaching Veterans at opportunities outside of healthcare interactions. Decisions were also made during the course of this pilot to consolidate program materials as a means of improving their usability. Specifically, the initial CO-ACT toolkit was conceptualized as a toolkit with a companion workbook. However, informal feedback from organizational teams and co-investigators suggested these materials should be package into one document. Consequently, the workbook was integrated into the toolkit to provide a single resource for partner organizations to utilize during CO-ACT.

VA CO-ACT facilitation leads collaboratively worked with each organization’s team in an effort to overcome challenges to implementing recommended suicide prevention programming. There were two commonly encountered barriers. First, organizations often lacked necessary resources (e.g., staffing shortages) and/or had staffing with significant constraints on their time. Second, not all organizations had data platforms available to easily track the implementation of suicide prevention programming, and tracking is an essential component to engaging in a continuous quality improvement process.

In light of encouraging findings from this pilot (8), subsequent tests are applying the same structure and processes of CO-ACT to a learning collaborative focused only on VA Community Care organizations (i.e., health care organizations the VA contracts with to provide Veteran health care services). Learning collaboratives can serve as a powerful vehicle for enhancing suicide prevention practices across organizations and offer promise as a solution to address Veteran suicide deaths in community settings.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JM: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PR: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EB: Writing – review & editing. CB: Writing – review & editing. LM: Writing – review & editing. KB: Writing – review & editing. EV: Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – review & editing. AP: Writing – review & editing. JH: Writing – review & editing. NM: Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – review & editing. KW: Writing – review & editing. MP: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. BK: Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing. TA: Writing – review & editing. JB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. BD: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA National Center for Patient Safety.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (2023). Available online at: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023NationalVeteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf (Accessed February 1, 2023).

2. DeBeer B, Mignogna J, Talbot M, Villareal E, Mohatt N, Borah E, et al. Suicide prevention programs: Comparing four prominent models. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. Psychiatr Services. (2023). doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20230173

3. The Joint Commission. “Suicide Prevention Resources to support Joint Commission Accredited organizations implementation of NPSG 15.01.01. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission. (2020).

4. O'Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, Price RA, Hussey P, Farmer C, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: A systematic review. J Gen Internal Med. (2017) 32:105–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide: 2018–2028 (2018). Available online at: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf.

7. DeBeer B, Baack S, Bongiovanni K, Borah E, Bryan C, Bryant K, et al. The Veterans Affairs Patient Safety Center of Inquiry – Suicide Prevention Collaborative: Creating novel approaches to suicide prevention among Veterans receiving community services. Federal Practitioner. (2020) 37:512–21. doi: 10.12788/fp.0071

8. DeBeer B, Mignogna J, Borah E, Bryan C, Monteith LL, Russell P, et al. A pilot of a veteran suicide prevention learning collaborative among community organizations: Initial results and outcomes. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. (2023) 53:628–41. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12969

9. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2003). Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx.

10. National Council for Behavioral Health. Zero Suicide Breakthrough Series: Outcomes and Recommendations (2015). Available online at: https://zerosuicide.edc.org/sites/default/files/Breakthrough%20Series.pdf.

11. Zero Suicide Institute. Zero suicide toolkit: Lead, train, identify, engage, treat, transition, improve. Available online at: https://zerosuicide.sprc.org/.

12. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research. Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US (1994).

13. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2009).

14. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention strategies & interventions for preventing NMUPD and opioid overdose across the IOM continuum of care. Available online at: https://cadcaworkstation.org/public/DEA360/Shared%20Resources/Root%20Causes%20and%20other%20research/Crosswalk%20PST_USI_models%20with%20NMUPD_PDO:%20examples_9_27_2016_revised.pdf.

15. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services. Focus on prevention: Strategies and programs to prevent substance abuse. (2017). Available online at: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma10-4120.pdf.

16. Gordon RS. An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Rep. (1983) 98:107–9.

17. Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Sci. (2015) 11:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

18. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention guidebook (2018). Available online at: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/VA-Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-Guidebook-June-2018-FINAL-508.pdf.

19. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. The national violent death reporting system (NVDRS): NVDRS State Profiles . Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/datasources/nvdrs/stateprofiles.html.

20. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. DoD Instruction 6490.04: Mental health evaluations of members of the military services (2013). Available online at: https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/649004p.pdf.

21. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. DoD instruction 6490.16: Defense suicide prevention program (2017). Available online at: https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/649016p.pdf?ver=2020-09-11-122632-850.

22. Sisti D, Joffe S. Implications of Zero Suicide for suicide prevention research. JAMA. (2018) 320:1633–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13083

23. Centers for Disease (CDC) Control and Prevention. Preventing suicide: Program activities guide (2010). Available online at: https://taadas.s3.amazonaws.com/files/0b4d65da8c9011fff4238236061861f5-Preventing%20Suicide%20Program%20Activities.pdf.

24. Stone D, Holland K, Bartholow B, Crosby A, Davis S, Wilkins N. Preventing suicide: A technical package of policy, programs, and practices. (2017). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicidetechnicalpackage.pdf.

25. Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan–do–study–act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. (2014) 23:290–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862

27. Reason J. Human error: models and management. Br Med J. (2000) 320:768–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768

28. Community Toolbox: Analyzing Community Problems and Designing and Adapting Community Interventions. Community Toolbox. Available online at: https://ctb.ku.edu/en.

29. Driever MJ. Are evidenced-based practice and best practice the same? Western J Nurs Res. (2002) 24:591–7. doi: 10.1177/019394502400446342

30. Goode CJ, Piedalue F. Evidenced-based clinical practice. J Nurs Administration. (1999) 29:15–21. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199906000-00005

31. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Best practice. NCI Dictionary. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/best-practice.

32. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidenced-based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t? Br Med J. (1996) 312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

33. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide (2019). Available online at: https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/srb/.

Keywords: suicide prevention, veterans, learning collaborative, public health, community case study

Citation: Mignogna J, Russell PD, Borah E, Bryan CJ, Monteith LL, Bongiovanni K, Villareal E, Hoffmire CA, Peterson AL, Heise J, Mohatt N, Baack S, Weinberg K, Polk M, Mealer M, Kremer BR, Gallanos J, Blessing A, Scheihing J, Alverio T, Benzer J and DeBeer BB (2024) Veteran suicide prevention learning collaborative: implementation strategy and processes. Front. Psychiatry 15:1392218. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1392218

Received: 27 February 2024; Accepted: 13 June 2024;

Published: 10 July 2024.

Edited by:

Tadashi Takeshima, Kawasaki City Inclusive Rehabilitation Center, JapanReviewed by:

Gwenyth Wallen, Clinical Center (NIH), United StatesManami Kodaka, Musashino University, Japan

Copyright © 2024 Mignogna, Russell, Borah, Bryan, Monteith, Bongiovanni, Villareal, Hoffmire, Peterson, Heise, Mohatt, Baack, Weinberg, Polk, Mealer, Kremer, Gallanos, Blessing, Scheihing, Alverio, Benzer and DeBeer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bryann B. DeBeer, YnJ5YW5uLmRlYmVlckB2YS5nb3Y=

Joseph Mignogna

Joseph Mignogna Patricia D. Russell

Patricia D. Russell Elisa Borah

Elisa Borah Craig J. Bryan

Craig J. Bryan Lindsey L. Monteith1,2,7

Lindsey L. Monteith1,2,7 Claire A. Hoffmire

Claire A. Hoffmire Alan L. Peterson

Alan L. Peterson Jenna Heise

Jenna Heise James Gallanos

James Gallanos Bryann B. DeBeer

Bryann B. DeBeer