94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 04 March 2024

Sec. Adolescent and Young Adult Psychiatry

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1351629

This article is part of the Research TopicSocial support for preventing suicide in children and adolescentsView all 6 articles

Omid Dadras1,2*

Omid Dadras1,2* Naoki Takashi3,4

Naoki Takashi3,4Introduction: Bullying, both in person and online, is a significant risk factor for a range of negative outcomes including suicidal behaviors among adolescents and it is crucial to explore the protective effects of parental, school, and peer connectedness on suicidal behaviors among victims.

Methods: This study is a secondary analysis of the Argentina Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS 2018). Logistic regression analysis, adjusting for age and sex, determines the likelihood of suicidal thoughts and attempts among bullying victims. To explore the modifying effect of school, parental, and peer connectedness on the association between bullying and suicide behaviors, the interaction term was included. Sampling design and weights were applied in all analyses in STATA 17.

Results: The study included 56,783 students in grades 8-12, with over half being female. Adolescents aged 14-15 exhibited the highest prevalence of bullying, cyberbullying, suicidal thoughts, and attempts, with females displaying a higher prevalence in all measured categories. The study found that adolescents who reported being bullied or cyberbullied demonstrated a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing suicidal thoughts and attempting suicide. Furthermore, protective factors such as school, parental, and peer connectedness were found to play a critical role in mitigating the adverse impacts of bullying and cyberbullying on suicidal thoughts and attempts.

Conclusion: The findings underscore the critical prevalence of both bullying and cyberbullying among school-going Argentinian adolescents and their profound association with suicidal behaviors. The study emphasizes the importance of supportive family environments and peer and school connectedness in mitigating the negative effects of bullying and cyberbullying on mental health and suicide risk among adolescents.

Bullying is a pervasive issue in schools, characterized by repeated aggressive behavior and an imbalance of power (1). This is considered cyberbullying if it involves using information and communication technologies (ICTs) to harm others. Cyberbullying occurs most frequently through email and social networking sites, with mobile phones being the primary method in some countries (2). Bullying, both in person and online, is a significant risk factor for a range of negative outcomes including mental health issues and suicidal behaviors among school-going adolescents, with a higher prevalence in Latin America and other low- and middle-income countries (3–5). Approximately 10-20% of youth are bullied by their peers, and 5-15% engage in bullying behavior (6). The association between bullying and suicide risk is particularly concerning, with studies indicating that any involvement in bullying increases the likelihood of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (5, 6). This correlation is particularly concerning among school-going adolescents in Argentina with approximately 22% of students aged 13-17 years experiencing bullying victimization and having suicidal thoughts in the past 12 months according to the Global School-based Student Health Survey 2018 (GSHS 2018) (7).

Bullied children and adolescents may exhibit psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches and musculoskeletal pains, which can be indicative of deeper psychological distress and potential suicidal behaviors. Research has shown that bullying can cause an emotional toll on its victims, leading to physical manifestations of mental anguish, including symptoms like unusual headaches, loss of appetite, sleeping problems, and abdominal pain (8–11). These psychosomatic symptoms serve as important indicators of the psychological impact of bullying, and recognizing this connection is crucial for early diagnosis and intervention to prevent suicidal ideation and attempts among bullied youths (10). The impact of bullying on mental health can be long-lasting, leading to feelings of rejection, exclusion, isolation, low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (12). Therefore, it is essential to address bullying and its associated psychological and physical consequences to ensure the well-being of children and adolescents.

In addition to the detrimental effects of bullying victimization, the protective role of connectedness to family, school, peers, and community has been highlighted in mitigating the risk of adverse outcomes among adolescents (13, 14). It has been found that family and school connectedness was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and conduct problems, as well as higher self-esteem and more adaptive use of free time (13, 14). Additionally, the importance of social support, particularly from family, in promoting good mental health and protecting bullied adolescents from poor academic achievement has been documented (15). Research also underscored the significance of caring and connectedness, particularly a sense of connectedness to family and school, in reducing high-risk behaviors among youth (16) and those who felt more connected to parents and school reported lower levels of depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and non-suicidal self-injury (13).

Given the significance of these issues, it is crucial to explore the protective effects of parental, school, and peer connectedness on suicidal behaviors among bullying victims among Argentinian adolescents. In particular, this research focuses on whether Argentinian students who have been the victim of either traditional or cyberbullying experience more suicidal thoughts and attempts and how the suggested protective factors including parental understanding, school connectedness, and having close friends could modify this relationship. By understanding the effect of these potential protective factors, strategies, and interventions can be formulated to reduce the prevalence of bullying and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in Argentina.

This cross-sectional study used data from the 2018 Argentina Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS), a nationally representative school-based survey among students in 8-12th grades in Argentina. The GSHS uses self-administered questionnaires to collect information on health behavior and protective factors among a nationally representative sample of school-going adolescents in different countries.

Argentina GSHS 2018 used a two-stage cluster sampling to recruit a representative sample of Argentinian students in the 8th grade (primary/polymodal schools) to 12 fifth-grade (polymodal schools). In the first stage, schools were selected proportionally to the size of the school. In the second stage, classes were randomly selected and all students in those classes were invited to participate in the survey and complete a self-administered questionnaire in Spanish [11]. The students were informed about the study objectives their right to withdraw from the study and voluntary nature of their participation as well as the anonymity and confidentiality of collected data. The response rate was 86% for schools and 74% for students with an overall response rate of 63%. A total sample of 56,981 adolescents in 8-12th grades participated in the survey [11] and was included in this study to assess the associations between suicidal and bullying behaviors and the protective effect of school, parental, and peer connectedness.

The outcomes of interest in this study were suicide ideation and attempt. Suicide thoughts were assessed by the question “During the past 12 months have you ever seriously considered attempting suicide?”. The suicide attempt was assessed by the question “During the past 12 months, how many times did you attempt suicide?” The answers to both questions were coded as 1 “yes” and 0 “no”.

The exposure variables of interest in this study were traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Traditional bullying was measured by asking the questions “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied on school property” and “During the past 12 months, have you ever been bullied when you were not on school property?”. The responses to this question were combined to construct a binary variable for bullying with alternative categories of 1 “yes” and 0 “no”. Cyberbullying was measured by asking the question “During the past 12 months, have you ever been cyberbullied? (Count being bullied through texting, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, Whatsapp, Edmodo, Messenger, or other social media.)” and the response was binary (1 “yes” and 0 “no”).

The protective variable of interest was school connectedness which was assessed by asking the question “During the past 30 days, how many days did you miss classes or school without permission?”, a desirable school connectedness was considered no missing classes during past 30 days and thus, the responses were coded as 1 “yes” and 0 “no”. The parental-child (parental) connectedness was assessed by the question “During the past 30 days, how often did your parents or guardians understand your problems and worries?” and the responses were categorized as always/often “1” and never/rarely/sometimes “0”. The peer connectedness was assessed by asking the question “How many close friends do you have?” having even one close friend was considered desirable and the responses were coded as 1 “yes” and 0 “no”.

Age and sex are the most important influencing factors on both traditional and cyberbullying (17–19) as well as suicidal behaviors and therefore, to measure the modifying impact of the protective factors in this study, we have adjusted all the models for the confounding effect of these two variables (20). Additionally, we have also included grades (8-12th) as a covariate, however, due to collinearity between this variable and age, it was not included in the multivariate analyses.

Descriptive statistics were employed to describe the sample demography and the distribution of outcome (suicide thoughts and attempts) and exposure variables (traditional bullying, cyberbullying) across demographic characteristics (age, sex, grade) among Argentinian adolescents in grades 8–12th. The chi-square test examined the association of exposure and outcome variables with demographic characteristics (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis, adjusting for age and sex, determines the likelihood of suicidal thoughts and attempts among bullying victims. To explore the modifying effect of school, parental, and peer connectedness on the association between bullying and suicide behaviors, the interaction term was included in multivariate analyses and the marginal effect was examined reporting the p-value for the interaction term. To specify the protective effect, the population was restricted to bullying victims, and the odds of suicide thoughts and attempts were examined across the categories of school, parental, and peer connectedness, and the results were reported as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI). Due to the complex sampling design in Argentina GSHS 2018, sampling design and weights were defined and applied in all analyses in STATA 17. The statistical significance level was set at p< 0.05.

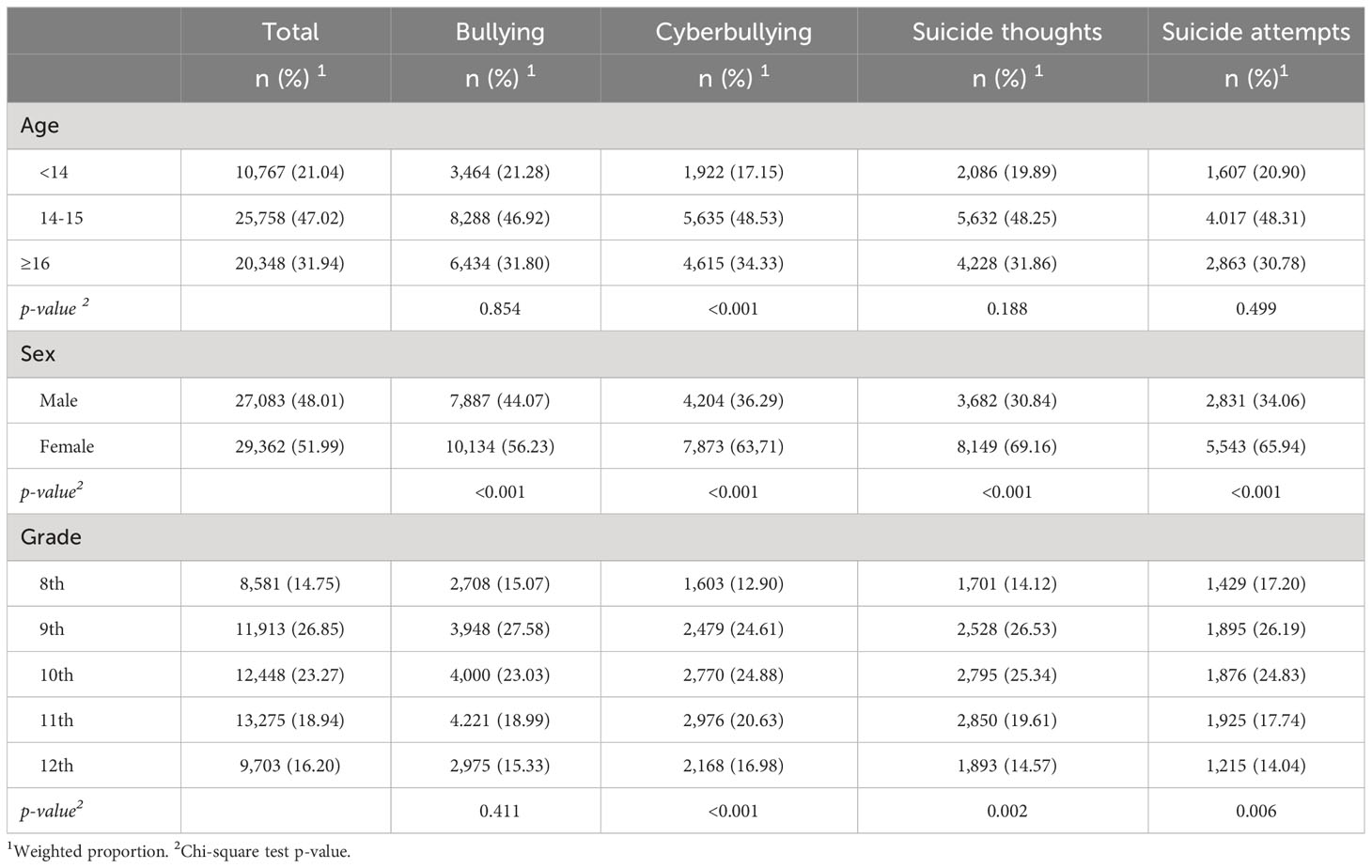

Table 1 The prevalence of suicidal and bullying behaviors among school-going Argentinian adolescents; by age, sex, and grade.

A total of 56,783 students in grades 8-12th included in the present study. More than half were female (51.99%). The majority were in 9th (26.85%) and 10th (23.27%) grades.

Table 1 illustrates the prevalence of suicidal and bullying behaviors among Argentinian adolescents in grades 8-12th. No significant differences were observed in bullying prevalence across age groups (p = 0.854). However, significant differences were found in cyberbullying (p < 0.001) and suicide thoughts (p = 0.188) among different age categories. Adolescents aged 14-15 exhibited the highest prevalence of bullying (46.92%), cyberbullying (48.53%), suicide thoughts (48.25%), and suicide attempts (48.31%); followed by those aged ≥16 years with the lowest prevalence among those aged <14 years old. Females displayed higher prevalence in all measured categories, notably in cyberbullying (63.71%), suicide thoughts (69.16%), and suicide attempts (65.94%). Significant differences were observed between sexes across all measured categories (p < 0.001). Middle grades (9th-11th) demonstrated a slightly higher prevalence of bullying and suicide behaviors. Significant differences were observed in cyberbullying (p < 0.001), suicide thoughts (p = 0.002), and suicide attempts (p = 0.006) among different grades.

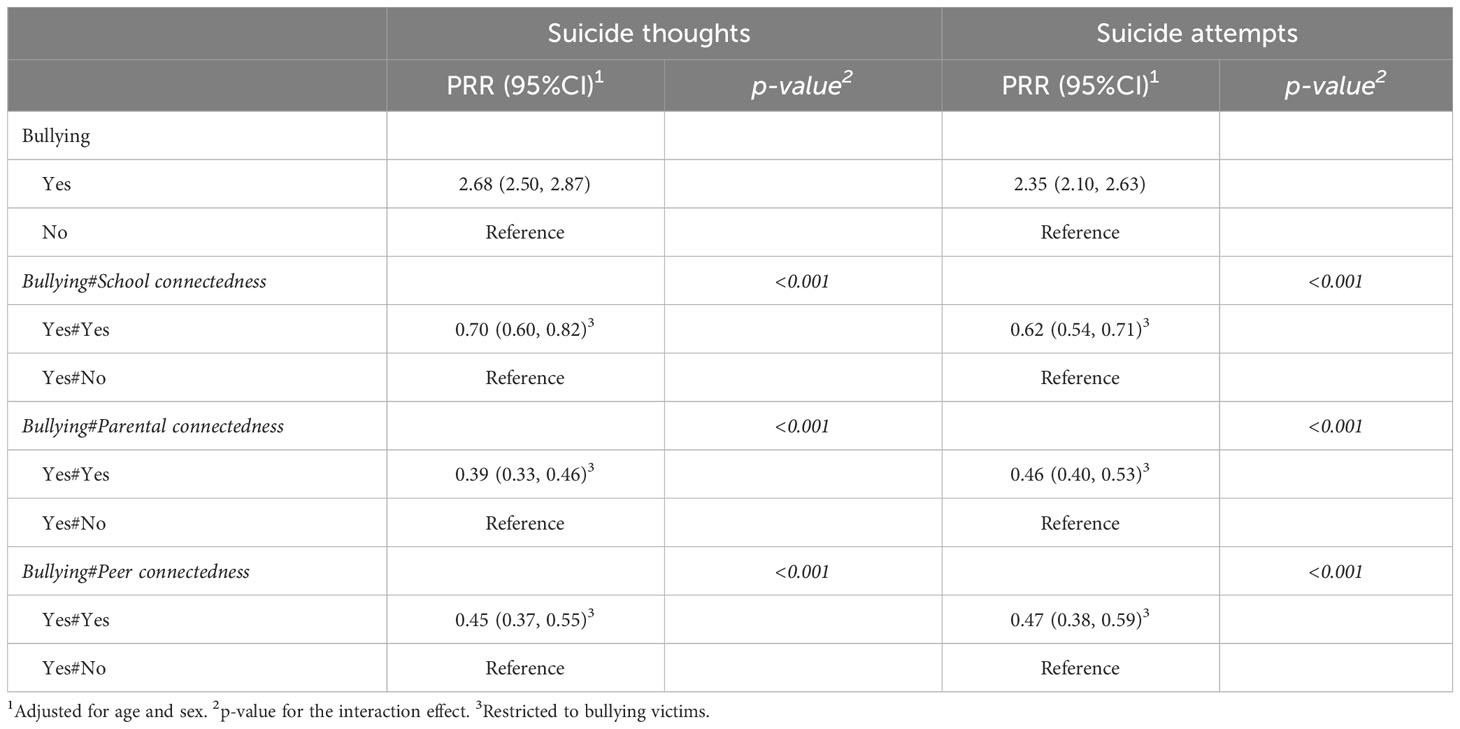

Adolescents who reported being bullied demonstrated significantly higher likelihoods of experiencing suicidal thoughts (PRR: 2.68, 95% CI: 2.50-2.87) and attempting suicide (PRR: 2.35, 95% CI: 2.10-2.63) compared to those who were not bullied. As Table 2 illustrates, all interactions between bullying and protective factors were statistically significant (p < 0.001), highlighting the significant moderating roles of school, parental, and peer connectedness in attenuating the impact of bullying on suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Among bullying victims, having favorable school connectedness significantly reduced the likelihood of suicide thoughts (PRR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.60-0.82) and suicide attempts (PRR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.54-0.71) compared to victims without such connectedness. Bullying victims with strong parental connectedness exhibited notably lower likelihoods of suicide thoughts (PRR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.33-0.46) and suicide attempts (PRR: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.40-0.53) compared to victims lacking such connections with parents. Bullying victims who reported having good peer connectedness showed reduced likelihoods of suicidal thoughts (PRR: 0.45, 95% CI: 0.37-0.55) and suicide attempts (PRR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.38-0.59) compared to those without close peer connections.

Table 2 The relationship between bullying and behaviors among school-going Argentinian adolescents in grades 8-12th, GSHS 2018.

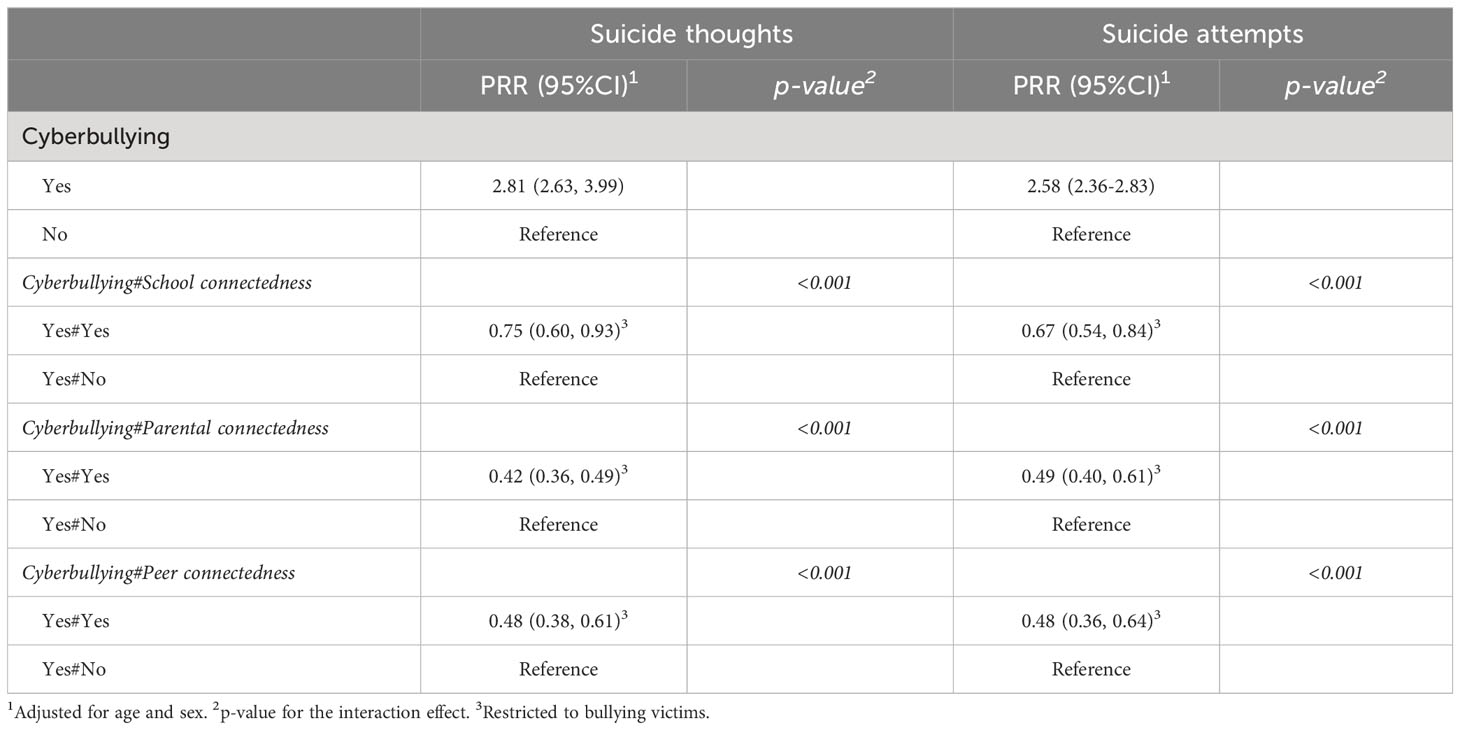

Adolescents who experienced cyberbullying exhibited significantly higher likelihoods of reporting suicidal thoughts (PRR: 2.81, 95% CI: 2.63-3.99) and attempting suicide (PRR: 2.58, 95% CI: 2.36-2.83) compared to those who did not report cyberbullying incidents. As Table 3 indicates, all interactions between cyberbullying and protective factors were statistically significant (p < 0.001), emphasizing the significant moderating roles of school, parental, and peer connectedness in mitigating the impact of cyberbullying on suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Among cyberbullying victims, favorable school connectedness significantly reduced the likelihood of suicidal thoughts (PRR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.60-0.93) and suicide attempts (PRR: 0.67, 95% CI: 0.54-0.84) compared to victims without such connectedness. Adolescents experiencing cyberbullying but having strong parental connectedness exhibited notably lower likelihoods of suicide thoughts (PRR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.36-0.49) and suicide attempts (PRR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.40-0.61) compared to victims lacking such connections with parents. Cyberbullying victims who reported having good peer connectedness showed reduced likelihoods of suicide thoughts (PRR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.38-0.61) and suicide attempts (PRR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.36-0.64) compared to those without close peer connections.

Table 3 The relationship between cyberbullying and behaviors among school-going Argentinian adolescents in grades 8-12th, GSHS 2018.

The findings of this study underscore the critical prevalence of both bullying and cyberbullying among Argentinian adolescents and their profound association with suicidal behaviors, highlighting several noteworthy points. Adolescents aged 14-15 experienced the highest prevalence of bullying (46.92%), cyberbullying (48.53%), suicide thoughts (48.25%), and suicide attempts (48,31%); followed by those older than 16 years old. Studies have highlighted mid-adolescence (around 14-15 years) as a critical period where bullying, cyberbullying, and suicidal tendencies tend to peak. This peak in mid-adolescence aligns with the developmental phase where physical and psychological changes are most pronounced (21, 22) and often marks increased vulnerability to social stressors and peer influences, contributing to heightened prevalence (23, 24), with females being more affected than males (25). This vulnerability is exacerbated by the developmental factors of adolescence, such as heightened emotionality and risk-taking behavior (26). These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions and support for adolescents during this pivotal developmental phase. The exact reasons for gender differences remain unclear, but some theories suggest they might stem from variations in socialization, coping mechanisms, and the nature of bullying experienced by different genders (27).

The investigation into the relationship between bullying/cyberbullying and suicidal behaviors among Argentinian adolescents emphasized significantly elevated risks among victims. This is in line with previous studies indicating a greater risk of self-harm and suicidal behaviors among bullying and cyberbullying victims (24, 28, 29). This has been attributed to factors such as hopelessness, lowered self-esteem, psychological insecurity, increased fears of loneliness, emotional intelligence, and depressive symptoms (24, 30). These findings have significant implications for policies and interventions aimed at addressing bullying and cyberbullying among adolescents. It is crucial to recognize the heightened risk of suicidal behaviors among victims of bullying and cyberbullying and to implement targeted interventions to address these issues. This may involve the development and implementation of comprehensive anti-bullying programs in schools, as well as mental health support services for victims of bullying and cyberbullying. It is also important to recognize that adolescents subjected to bullying often have pre-existing personal issues that exacerbate their vulnerability, suggesting that interventions should focus on addressing these primary personal issues alongside bullying (31–33). These issues can range from poor parental support and monitoring to academic and social difficulties. The role of schools in identifying and supporting these adolescents is crucial, considering that both bullies and victims often face family and personal challenges (31). Therefore, a comprehensive approach to addressing bullying should also take into account the underlying personal fragilities that may contribute to both bullying and poor social connections (31, 32).

The findings of the present study also showed that protective factors such as school connectedness can have a critical role in mitigating the adverse impacts of bullying and cyberbullying on suicidal thoughts and attempts among school-going Argentinian adolescents. Research consistently demonstrates the protective role of school connectedness in mitigating the adverse impacts of bullying and cyberbullying on adolescent mental health (20, 34). Evidence have shown that youth who feel connected to their school are less likely to experience poor mental health, sexual health risks, substance use, and violence (35). Higher levels of school connectedness are associated with lower levels of suicidal behavior and depression, and with higher levels of self-esteem. This is particularly true for victims of cyberbullying, suggesting that school connectedness can buffer the negative effects of cyberbullying on mental health (34). A similar study among Korean adolescents found that school connectedness moderated the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation, regardless of SES. These findings underscore the importance of school connectedness in protecting adolescents from the harmful effects of bullying and cyberbullying.

Another important finding of the present study was the moderating effect of parent-child connectedness on the association between bullying and suicidal behaviors among school-going Argentinian adolescents. A study on family factors related to suicidal behavior in adolescents found that insecure attachment and rigid or negligent relationships between parents and children were associated with bullying and cyberbullying, which in turn were risk factors for suicidal behavior (36). Insecure attachment, resulting from parenting that is inattentive and unsupportive, can lead to children perceiving themselves as unlovable and others as harsh, and it has been correlated with a lack of interpersonal sensitivity and heightened aggression (36, 37). Additionally, parental styles of rejection and indifference and the non-disclosure of bullying and suicidal ideation. This point further underscores the significance of parental involvement in mitigating the risks associated with bullying (38). Another study suggested that secure attachment to parents can moderate the association between sibling bullying and depression/suicidal ideation among children and adolescents, leading to a weaker association between sibling bullying involvement and depression/suicidal ideation among children with secure attachments with their parents (39). Additionally, research performed in different countries has indicated that bullying at school is associated with psychological distress and suicidal behaviors, highlighting the importance of parent-adolescent bonding in mitigating these negative outcomes (40–42). These findings underscore the crucial role of parent-child connectedness in influencing the relationship between bullying and suicidal behaviors, emphasizing the need for supportive family environments to promote adolescents’ mental health. This can be facilitated through implementing programs that aim to improve both the parental and the children behavior. This could include parenting skills training, stress management, and strategies for effective family communication (43).

Having close friends, translated into peer connectedness in the present study, also appeared to moderate the effect of bullying victimization on the likelihood of suicidal thoughts and attempts. A study found that adolescents who reported greater improvements in peer connectedness were half as likely to attempt suicide during 12 months (44). Social connectedness, particularly with close friends, can play a protective role in mitigating the negative effects of bullying victimization on suicide risk (14, 45, 46). These findings highlight the importance of peer and school connectedness in mitigating the negative effects of bullying victimization on mental health and suicide risk among adolescents. Thus, policies and interventions should focus on promoting school, parental, and social connectedness among adolescents to mitigate the negative impact of bullying and cyberbullying on mental health.

The study utilized data from the 2018 Argentina Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS), which employed self-administered questionnaires to collect information on health behavior and protective factors among a nationally representative sample of school-going adolescents in Argentina. However, the response rate was 63%, which may introduce non-response bias and affect the generalizability of the findings. Nonetheless, the large sample size of the study compensates for that, thereby ensuring the robustness and broader applicability of the results. The cross-sectional nature of the study design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between the variables of interest. Additionally, the study relied on self-reported measures for outcomes such as suicide ideation and attempt, as well as exposure variables like traditional bullying and cyberbullying which may be subject to recall bias and social desirability bias, potentially impacting the accuracy of the results. While the study adjusted for age and sex, other potential confounding variables such as socioeconomic status, mental health history, and family dynamics were not included. Failure to account for these factors may limit the ability to draw robust conclusions about the associations observed.

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the critical prevalence of both bullying and cyberbullying among school-going Argentinian adolescents in grades 8-12 and their profound association with suicidal behaviors. The study highlights the need for targeted interventions to address these issues, including the development and implementation of comprehensive anti-bullying programs in schools, and mental health support services for victims of bullying and cyberbullying. The study also emphasizes the importance of supportive family environments and peer and school connectedness in mitigating the negative effects of bullying and cyberbullying on mental health and suicide risk among adolescents. Given the gravity of the issue, in 2022, for the first time, the Argentinian government introduced a national strategy aimed at preventing, addressing, and eradicating bullying and cyberbullying in children and youth. This initiative is outlined in Bill No. 3038-D/2022, which focuses on creating a comprehensive approach to combat these issues in educational institutions in the country. The effect of this program in reducing bullying, however, should be explored in future studies.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog.

This was a secondary analysis of the Argentina Global School-Based Student Health Survey conducted in 2018 (GSHS 2018). The GSHS protocol received approval and guidance from Argentina’s Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Public Health and written informed consent was obtained from the participants or their guardians before the survey.

OD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NT: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We would like to thank the World Health Organization NCD Microdata Repository for granting us with access to Argentina GSHS 2018.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Menesini E, Salmivalli C. Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychol Health Med. (2017) 22:240–53. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

2. Brandtzæg PB, Staksrud E, Hagen I, Wold T. Norwegian children’s experiences of cyberbullying when using different technological platforms. J Children Media. (2009) 3:349–65. doi: 10.1080/17482790903233366

3. Okobi OE, Egbujo U, Darke J, Odega AS, Okereke OP, Adisa OT, et al. Association of bullying victimization with suicide ideation and attempt among school-going adolescents in post-conflict Liberia: findings from the global school-based health survey. Cureus. (2023) 15(6):e40077. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40077

4. Fei W, Tian S, Xiang H, Geng Y, Yu J, Pan C-W, et al. Associations of bullying victimisation in different frequencies and types with suicidal behaviours among school-going adolescents in low-and middle-income countries. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2022) 31:e58. doi: 10.1017/S2045796022000440

5. Cooper GD, Clements PT, Holt KE. Examining childhood bullying and adolescent suicide: Implications for school nurses. J School Nursing. (2012) 28:275–83. doi: 10.1177/1059840512438617

6. Gini G, Espelage DL. Peer victimization, cyberbullying, and suicide risk in children and adolescents. Jama. (2014) 312:545–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3212

7. WHO. Argentina Global school-based student health survey. (2018). Available at: https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/866

8. Bjereld Y, Augustine L, Turner R, Löfstedt P, Ng K. The association between self-reported psychosomatic complaints and bullying victimisation and disability among adolescents in Finland and Sweden. Scand J Public Health. (2023) 51:1136–43. doi: 10.1177/14034948221089769

9. Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Bully victims: psychological and somatic aftermaths. Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa: Township)). (2008) 5 6:62–4.

10. Fekkes M, Pijpers FIM, Fredriks AM, Vogels T, Verloove-vanhorick SP. Do bullied children get ill, or do ill children get bullied? A prospective cohort study on the relationship between bullying and health-related symptoms. Pediatrics. (2006) 117:1568 – 74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0187

11. Polese D, Belli A, Esposito D, Evangelisti M, Luchetti A, Di Nardo G, et al. Psychological disorders, adverse childhood experiences and parental psychiatric disorders in children affected by headache: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 140:104798. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104798

12. Verkuil B, Atasayi S, Molendijk ML. Workplace bullying and mental health: A meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0135225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135225

13. Foster CE, Horwitz A, Thomas A, Opperman K, Gipson P, Burnside A, et al. Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents. Children Youth Serv review. (2017) 81:321–31. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.011

14. Arango A, Cole-Lewis Y, Lindsay R, Yeguez CE, Clark M, King C. The protective role of connectedness on depression and suicidal ideation among bully victimized youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2018) 48:728–39. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1443456

15. Rothon C, Head J, Klineberg E, Stansfeld S. Can social support protect bullied adolescents from adverse outcomes? A prospective study on the effects of bullying on the educational achievement and mental health of adolescents at secondary schools in East London. J adolescence. (2011) 34:579–88. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.02.007

16. Resnick MD, Harris LJ, Blum RW. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. J paediatrics Child Health. (1993) 29:S3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x

17. Smith PK. Making an impact on school bullying: Interventions and recommendations. London: Routledge (2019). doi: 10.4324/9781351201957

18. Tokunaga RS. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput Hum behavior. (2010) 26:277–87. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

19. Kowalski RM, Limber SP, McCord A. A developmental approach to cyberbullying: Prevalence and protective factors. Aggression violent behavior. (2019) 45:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.02.009

20. Lucas-Molina B, Pérez-Albéniz A, Solbes-Canales I, Ortuño-Sierra J, Fonseca-Pedrero E. Bullying, cyberbullying and mental health: The role of student connectedness as a school protective factor. Psychosocial Intervention. (2022) 31:33. doi: 10.5093/pi2022a1

21. Lancet T. An age of uncertainty: mental health in young people. (2022) 400:539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01572-0

22. Maccari S, Polese D, Reynaert M-L, Amici T, Morley-Fletcher S, Fagioli F. Early-life experiences and the development of adult diseases with a focus on mental illness: the human birth theory. Neuroscience. (2017) 342:232–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.05.042

23. Memon AM, Sharma SG, Mohite SS, Jain S. The role of online social networking on deliberate self-harm and suicidality in adolescents: A systematized review of literature. Indian J Psychiatry. (2018) 60:384–92. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_414_17

24. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res. (2010) 14:206–21. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2010.494133

25. Nikolaou D. Does cyberbullying impact youth suicidal behaviors? J Health economics. (2017) 56:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.09.009

26. Gunn JF, Goldstein SE. Bullying and suicidal behavior during adolescence: A developmental perspective. Adolesc Res Review. (2017) 2:77–97. doi: 10.1007/s40894-016-0038-8

27. Kim S, Kimber M, Boyle MH, Georgiades K. Sex differences in the association between cyberbullying victimization and mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. (2019) 64:126–35. doi: 10.1177/0706743718777397

28. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The relationship between bullying and suicide: What we know and what it means for schools. Chamblee, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention (2014).

29. John A, Glendenning AC, Marchant A, Montgomery P, Stewart A, Wood S, et al. Self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. (2018) 20:e9044. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9044

30. Maurya C, Muhammad T, Dhillon P, Maurya P. The effects of cyberbullying victimization on depression and suicidal ideation among adolescents and young adults: a three year cohort study from India. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04238-x

31. Erginoz E, Alikasifoglu M, Ercan O, Uysal O, Alp ZZ, Ocak S, et al. The role of parental, school, and peer factors in adolescent bullying involvement. Asia-Pacific J Public Health. (2015) 27:NP1591 – NP603. doi: 10.1177/1010539512473144

32. Craig W, Pepler DJ. Identifying and targeting risk for involvement in bullying and victimization. Can J Psychiatry. (2003) 48:577 – 82. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800903

33. Juvonen J, Graham SH, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: the strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics. (2003) 112:6. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231

34. Kim J, Walsh E, Pike K, Thompson EA. Cyberbullying and victimization and youth suicide risk: the buffering effects of school connectedness. J school nursing. (2020) 36:251–7. doi: 10.1177/1059840518824395

35. CDC. School connectedness helps students thrive (2023). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/protective/school_connectedness.htm#print.

36. Alvarez-Subiela X, Castellano-Tejedor C, Villar-Cabeza F, Vila-Grifoll M, Palao-Vidal D. Family factors related to suicidal behavior in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:9892. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19169892

37. Murphy G, Peters K, Wilkes L, Jackson D. A dynamic cycle of familial mental illness. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2014) 35:948–53. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2014.927543

38. Estévez-García JF, Cañas E, Estévez E. Non-disclosure and suicidal ideation in adolescent victims of bullying: an analysis from the family and school context. Psychosoc Interv. (2023) 32:191–201. doi: 10.5093/pi2023a13

39. Bar-Zomer J, Brunstein Klomek A. Attachment to parents as a moderator in the association between sibling bullying and depression or suicidal ideation among children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. (2018) 9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00072

40. DeSmet A, Rodelli M, Walrave M, Portzky G, Dumon E, Soenens B. The moderating role of parenting dimensions in the association between traditional or cyberbullying victimization and mental health among adolescents of different sexual orientation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:2867. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062867

41. Nguyen HTL, Nakamura K, Seino K, Al-Sobaihi S. Impact of parent-adolescent bonding on school bullying and mental health in Vietnamese cultural setting: evidence from the global school-based health survey. BMC Psychol. (2019) 7:16. doi: 10.1186/s40359-019-0294-z

42. Peprah P, Asare BY-A, Nyadanu SD, Asare-Doku W, Adu C, Peprah J, et al. Bullying victimization and suicidal behavior among adolescents in 28 countries and territories: a moderated mediation model. J Adolesc Health. (2023) 73:110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.01.029

43. Thanhäuser M, Lemmer G, de Girolamo G, Christiansen H. Do preventive interventions for children of mentally ill parents work? Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2017) 30:283–99. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000342

44. Czyz EK, Liu Z, King CA. Social connectedness and one-year trajectories among suicidal adolescents following psychiatric hospitalization. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2012) 41:214–26. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.651998

45. Arango A, Brent D, Grupp-Phelan J, Barney BJ, Spirito A, Mroczkowski MM, et al. Social connectedness and adolescent suicide risk. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13908

Keywords: adolescents, bullying, cyberbullying, suicide, Argentina

Citation: Dadras O and Takashi N (2024) Traditional, cyberbullying, and suicidal behaviors in Argentinian adolescents: the protective role of school, parental, and peer connectedness. Front. Psychiatry 15:1351629. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1351629

Received: 07 December 2023; Accepted: 16 February 2024;

Published: 04 March 2024.

Edited by:

Rasmieh Al-amer, Yarmouk University, JordanReviewed by:

Daniela Polese, Sant’Andrea University Hospital, ItalyCopyright © 2024 Dadras and Takashi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Omid Dadras, b21pZC5kYWRyYXNAdWli

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.