- 1Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 2Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy

- 3Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 4Dipartimento ad Attività Integrate di Salute Mentale e Dipendenze Patologiche, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale (USL) IRCCS Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy

- 5Department of Mental Health and Dependence, AUSL of Modena, Modena, Italy

- 6Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

- 7Department of Humanities, Social Sciences and Cultural Industries, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

- 8Department of Mental Health and Pathological Addiction, Child and Adolescent Neuropsychiatry Service, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale (USL)-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy

- 9World Health Organiization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health and Service Evaluation, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, Section of Psychiatry, Verona, Italy

- 10IRCCS Istituto Delle Scienze Neurologiche di Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Introduction: Adolescents’ health and well-being are seriously threatened by suicidal behaviors, which have become a severe social issue worldwide. Suicide is one of the leading causes of mortality for adolescents in low and middle-income countries, with approximately 67,000 teenagers committing suicide yearly. Although an association between sleep disturbances (SDs) and suicidal behaviors has been suggested, data are still scattered and inconclusive. Therefore, to further investigate this association, we conducted a meta-analysis to verify if there is a link between SDs and suicidal behaviors in adolescents without diagnosed psychiatric disorders.

Methods: PubMed, CENTRAL, EMBASE, and PsycINFO were searched from inception to August 30th, 2024. We included studies reporting the estimation of suicidal behaviors in adolescents from 12 to 21 years of age, with SDs and healthy controls. The meta-analysis was based on odds ratio (OR, with a 95% confidence interval ([CI]), estimates through inverse variance models with random-effects.

Results: The final selection consisted of 19 eligible studies from 9 countries, corresponding to 628,525 adolescents with SDs and 567,746 controls. We found that adolescents with SDs are more likely to attempt suicide (OR: 3.10; [95% CI: 2.43; 3.95]) and experience suicidal ideation (OR: 2.28; [95% CI 1.76; 2.94]) than controls.

Conclusion: This meta-analysis suggests that SDs are an important risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in healthy adolescents. The findings highlight the importance of early identification of SDs to prevent suicidal behaviors in this population.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO, identifier CRD42023415526.

1 Introduction

Suicide is estimated as the fourth cause of death for people between the ages of 13 and 29 (1). Suicidality entails a wide range of phenomena, from death wishes and thoughts, also known as suicidal ideation (SI), to actual suicidal behaviors, comprising suicide attempts (SA) and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), which refers to the intentional harm to the body with no death desire and completed suicide. SI is relatively common in adolescence, with nearly 20% of 12-year-olds reporting such feelings in the past month (2). Also, NSSI typically occurs during adolescence, with a prevalence of 17% compared to 5% in adulthood (3). Despite these statistics, the prevention of adolescent suicide has received limited attention compared with suicide prevention in adults.

Previous research has shown that self-injures not only repeatedly inflicts painful injures but, also affects their cognitive and neurodevelopment trajectories (4).

Suicide imposes significant socioeconomic burdens on families, communities, and nations (5). Risk factors associated with suicidal behaviors in adolescents are multifactorial, complex, and interrelated (6).

Sleep disturbances (SDs) have recently gained attention as important risk factors for suicidal behaviors. SDs are defined as subjective experiences of difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakenings, short sleep duration, restless sleep, nightmares, and anxiety dreams, which affect approximately 7.8% to 23.8% of adolescents (5–7). Bedtimes get later with each passing year during adolescence, partially due to biological factors, such as adjustments to the homeostatic sleep regulating system that give greater tolerance for sleep deprivation, and sociocultural factors as the newly acquired autonomy (8). The average sleep duration during the weekend for the youngest adolescents is about 8.4 hours and about 6.9 hours for the high school seniors (9). Adolescents’ hours of sleep are significantly less than those recommended by the National Sleep Foundation (10). Furthermore, an Italian study revealed a different sleep profile across age groups: 16-years-olds subjects showed the highest percentage of insufficient sleep and frequent nocturnal awakenings, those between 18 and 19 years had the highest rate of insufficient sleep and difficulty falling asleep, and adolescents 17-year-old presented an elevated difficulty in waking up in the morning (11).

In adolescents, impaired sleep is associated with various psychosocial issues, such as an increased risk for depressed mood and anxiety disorders (12). Possibly, these disorders result from impaired emotion regulation that follows SDs. Indeed, a recent study showed that impaired emotion regulation strategies, such as decreased problem-solving and rumination, mediated the relation between SDs and anxiety and mood disorders (13). Lack of sleep is also associated with several health risk behaviors, such as increased substance use, excessive use of electronic media, and physical inactivity (14).

Previous reviews and meta-analyses found an association between SDs and suicide, including SI, SA, and completed suicide among adults (15–19). This association is, understandably, significantly reported among adult individuals with psychiatric diagnoses, in particular, the comorbidity of SDs (i.e., insomnia, parasomnia, and sleep-related breathing disorders, but not hypersomnia) and mental disorders (i.e., schizophrenia, depression, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder) was associated to an increased risk of completed suicide, a twofold risk of presenting SI and a fourfold risk of SA (20). Sleep is hypothesized to impact SI due to neurobiological factors such as the impact of sleep on serotonin and other factors involved in mood regulation, as well as the impact of nightmares (21). Adolescence witnesses notable alterations in sleep physiology, including reduced slow-wave sleep and delayed sleep phase syndrome. These changes have been linked to the emergence of SDs, such as insomnia symptoms. However, the precise mechanisms through which these physiological changes influence suicidal behaviors require further investigation (22). Sleep deprivation, a common consequence of SDs, can impair frontal lobe cognitive function. This impairment leads to compromised judgment and impulse control, potentially increasing the likelihood of engaging in suicidal behaviors (23). Adolescents, with their still-developing frontal lobe and emotional regulation circuitry, may be particularly vulnerable to these effects. Consequently, teenage sleep loss may promote young suicidality by increased impulsivity linked to the frontal lobe and emotional regulation circuitry that isn’t fully developed (24). Evidence suggests a link between SDs and weakened serotonergic systems. Individuals who have attempted suicide exhibit a more pronounced decline in serotonin production in the prefrontal cortex. This neurotransmitter imbalance may contribute to suicidal tendencies (25). Sleep-deprived adolescents may exhibit heightened reactivity in the mesolimbic network when exposed to pleasure-inducing stimuli. This heightened reactivity could potentially increase the inclination toward engaging in health-risk behaviors (26).

Adolescence is often characterized by changes in sleep patterns, in particular, adolescents reported poor sleep quality also due to physiological changes in sleep-wake architecture that become particularly pronounced from the onset to the end of puberty (27, 28). A significant gender gap must be highlighted, as female individuals report worse sleep quality than males due to hormonal changes; adolescents with SDs report more depression, anxiety, anger, inattention, drug and alcohol use, and reduced school performance. Adolescents also report more tiredness, less energy, a worse perception of health, and symptoms such as headache, stomachache, and back pain (29–31). SDs may increase the risk of suicide through psychosomatic disorders, which already represent a low level of health and possible risk factors for suicide.

The conclusions cannot be applied directly to the adolescent population because of the specific substantial differences in sleep–wake patterns that are considerably different from those of adults.

Specifically, during adolescence, the circadian rhythm becomes delayed, and the homeostatic sleep pressure is reduced, which leads to a change in sleep-wake patterns with later onset of sleep. Beyond this biological modification, behavioral and social factors further contribute to later bedtimes, as well as the increased use of electronic media and less parental involvement in setting bedtimes (32).

Furthermore, among healthy adolescents, the association is still inconsistent. A study showed that increased sleep duration among adolescents was associated with a low probability of having a suicide plan (33). Liu and colleagues showed in their review that in cross-sectional analyses, adolescents with SDs were at higher risk of SI and SA than those without SDs, while prospective reports indicated that SDs in adolescents significantly predicted the risk of SI but not of SA; finally, the retrospective study did not support the association between SDs and SA (34).

Therefore, considering that the association between SDs and suicidal behaviors could impact future suicide prevention strategies in adolescents and given the literature gaps, this meta-analysis aims to comprehensively examine the literature on the association between SDs and suicidal behaviors among adolescents without a formal psychiatric diagnosis.

2 Methods

The protocol of this study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023415526) and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematics Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines (35).

2.1 Eligibility criteria and search strategy

A literature search was carried out through the electronic databases PubMed, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and PsycINFO from inception to August 30th, 2024 (search terms are tailed in the Supplementary Material). The literature search was restricted to the English language and peer-reviewed journals.

Studies were included if they reported data on suicidal behavior, including SA, SI, NSSI, and death by suicide in individuals exposed to SDs compared to individuals unexposed. SDs were identified based on whether insomnia symptoms or other sleep problems were evaluated. Specifically, SDs were examined through specific questionnaires if they were available or through the hours of sleep.

We included studies on participants aged between 12 and 21 years without limitation of gender or ethnicity. To focus on the effect of SDs on suicidal behaviors and to minimize the confounding impact of concurrent psychiatric disorders, we excluded the studies involving participants with any formal psychiatric conditions. In particular, we did not include adolescents with a previous diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorders, Anxiety Disorder, Schizophrenia, or other mental illnesses certified by a psychiatrist.

A couple of authors (among VB, MG, and GR) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full text. A third author (MM) resolved the discrepancies by discussion and adjudication.

2.2 Data extraction and study quality assessment

A meta-analysis of the overall comparison of suicidal behavior rates among people with and without SDs was performed. Pooled Odds Ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were generated using inverse variance models with random effects (36). The results were summarized using forest plots. Standard Q tests and the I2 statistic (i.e., the percentage of variability in prevalence estimates attributable to heterogeneity rather than sampling error or chance, with values of I2 ≥75% indicating high heterogeneity) were used to assess between-study heterogeneity (37). Leave-one-out analysis and meta-regression were performed to examine sources of between-study heterogeneity on a range of study-prespecified characteristics (i.e., sex, age, risk of bias, use of alcohol or drugs, cigarette smoking, school attainment, and bullying experience).

If the meta-analysis included more than ten studies, we performed funnel plot analysis and the Egger test to test for publication bias (38). The Egger test quantifies bias captured in the funnel plot analysis using the value of effect sizes and their precision (i.e., the standard errors [SE]) and assumes that the quality of study conduct is independent of study size. If analyses showed a significant risk of publication bias, we would use the trim and fill method to estimate the number of missing studies and the adjusted effect size (39–42). All the analyses were performed in R (RStudio 2021) using meta and metafor packages (43, 44). Statistical tests were 2-sided and used a significance threshold of p-value <0.05.

The studies included in the final section were assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which calculates the risk of bias in observational studies on the three domains (selection, comparability, and exposure) and provides an overall score ranging from 1 (the highest risk of bias) to 9 (the lowest risk of bias). Two authors (MG, GR) assessed the risk independently, and disagreements were discussed with a third author (VB).

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of included studies

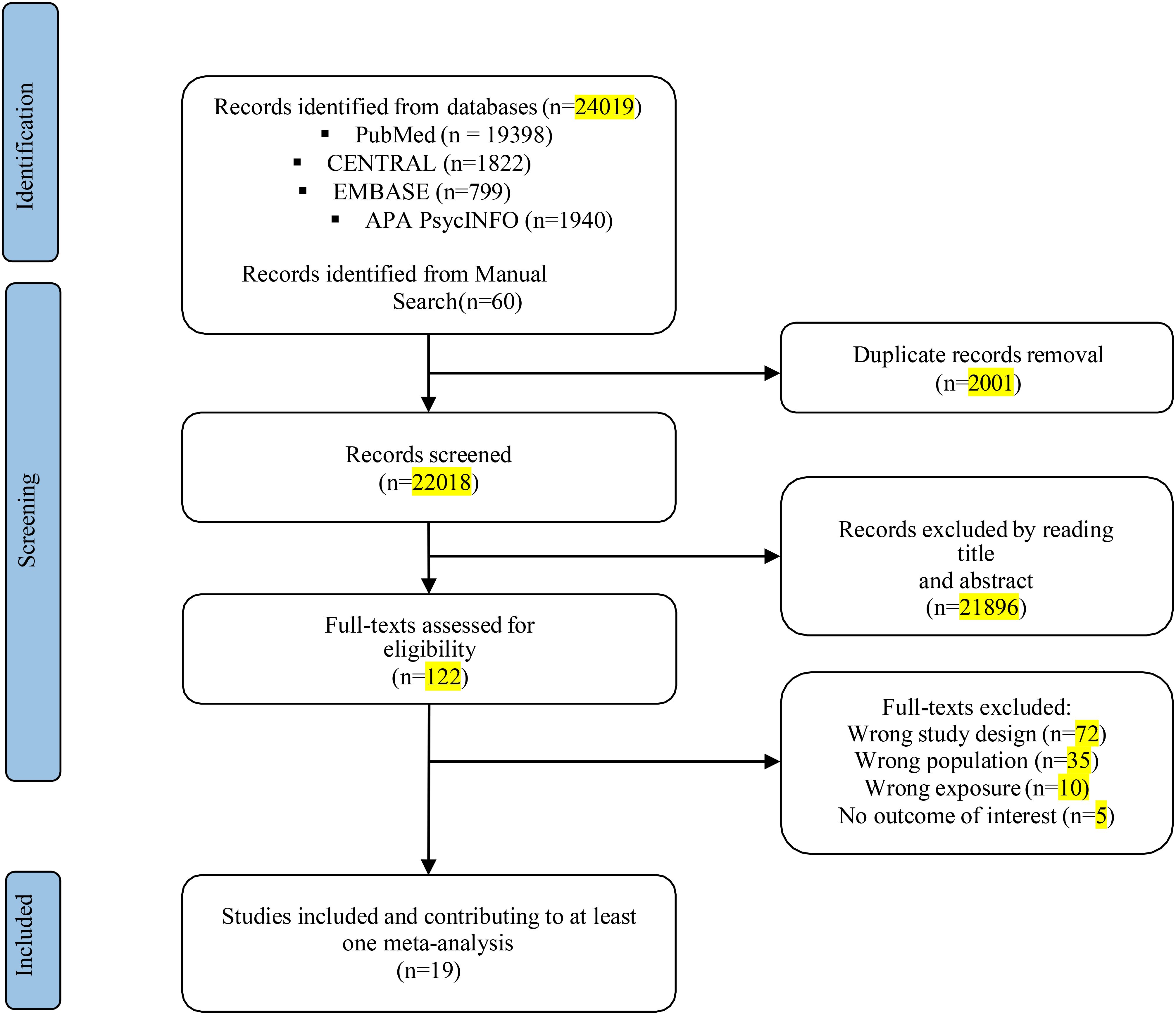

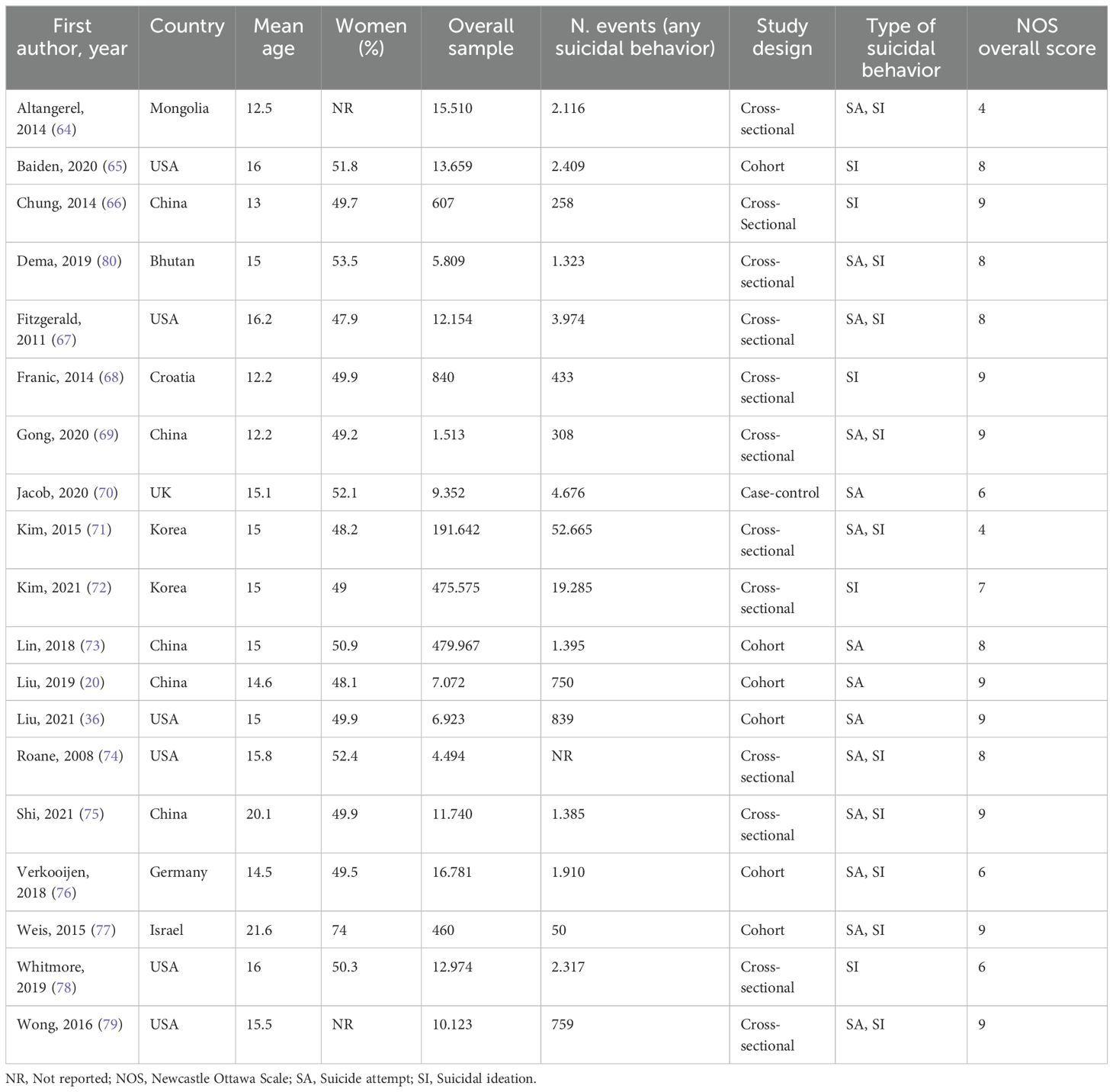

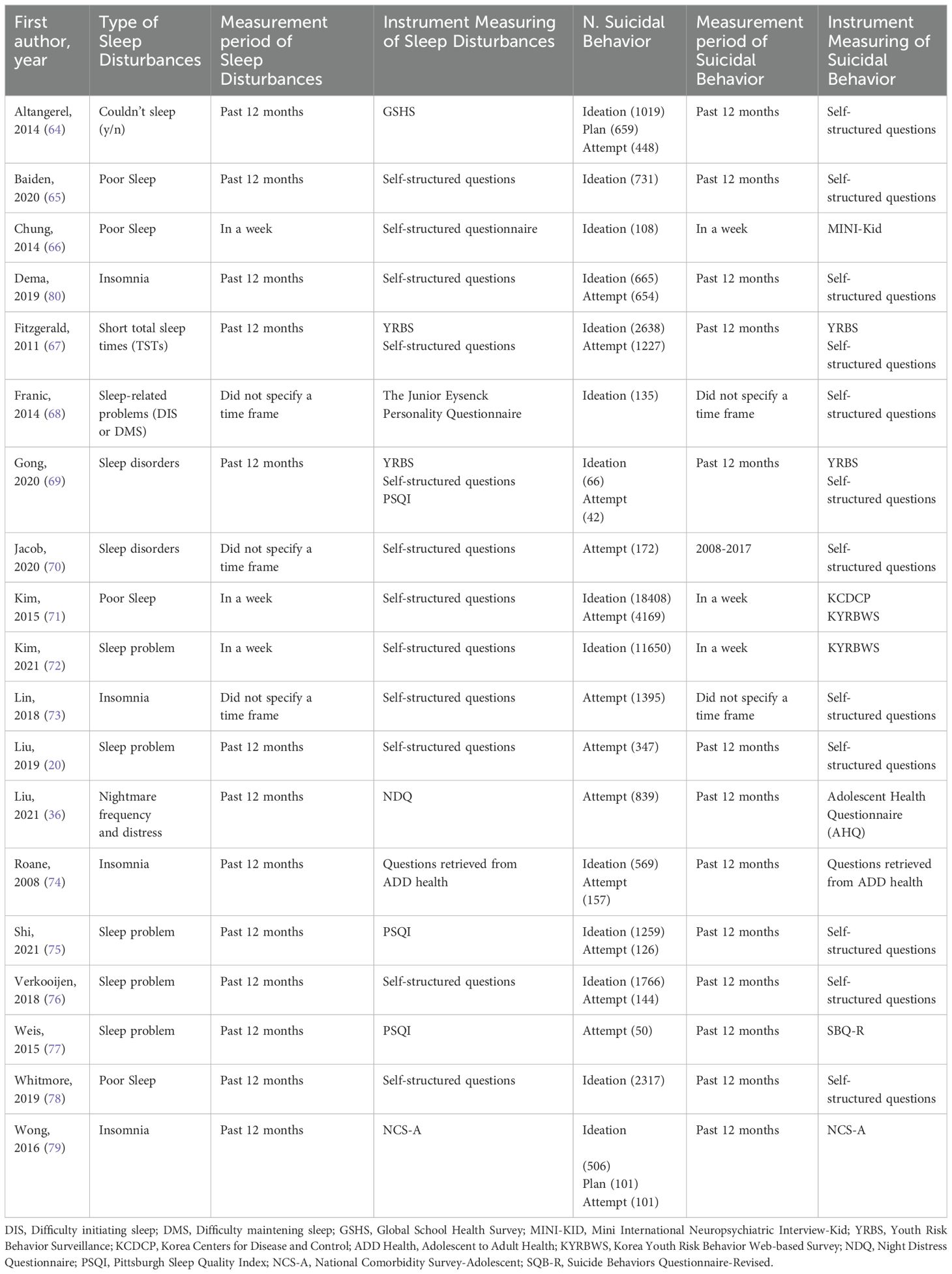

The literature search using electronic methods resulted in a total of 24,019 records. After removing duplicate entries, 22,018 records were subjected to title and abstract screening. After the preliminary stage, 122 completed texts were evaluated for eligibility. Of these, 19 studies met the pre-specified inclusion criteria. These studies encompassed a sample size of 628,525 adolescents with SDs (including insomnia symptoms or other sleep problems) and 567,746 control participants (see Figure 1). Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of the participant characteristics observed in the studies included in the analysis. The studies included in this analysis quantify SDs in terms of hours and assess sleep quality. The characteristics of the studies were reported in Table 2.

The average age of the participants was 15.2 years, and the average proportion of females was 46.3%. Of the nineteen studies examined, thirteen showed a low risk of bias based on a total score of 8-9 according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Conversely, the remaining studies exhibited a moderate risk of bias, with a total score ranging from 4 to 7. For further details, refer to the appendix, specifically Data Sheet 1 (Supplement 1).

3.2 Association between sleep disturbances and suicidal behaviors

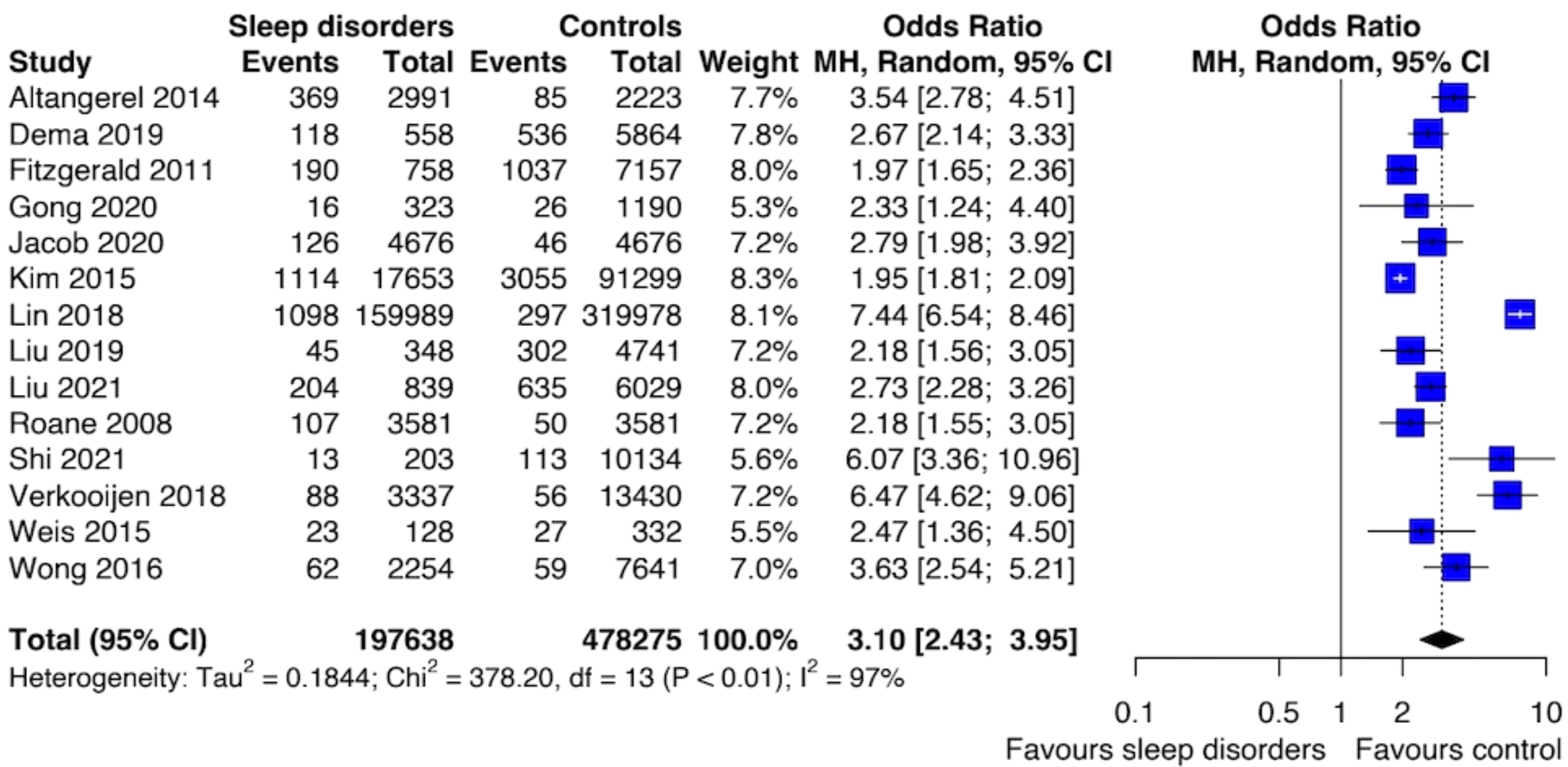

The prevalence of SI ranges from 5% to 19.8%, whereas the prevalence of SA ranges from 0.3% to 10.6%. The meta-analysis of the SA risk was based on 14 studies and showed an association with SDs (OR 3.10; [95% CI: 2.43; 3.95]) (Figure 2). The level of between-study heterogeneity was high (I2 = 96.6%). By looking at the forest plot of SA, it is possible to notice that the study by Lin et al. (2018) provided higher odds for SA. This study focused on adolescents with insomnia, however, the authors did not provide a timeframe to which the assessment of both SA and SDs were referred. Interestingly, this study is also the one with the largest sample size.

Figure 2. Forest plot of primary analysis between association of suicide attempt and sleep disturbances.

Sensitivity analysis removing studies with a high risk of bias confirmed the association between SDs and SA (OR: 3.03; [95% CI: 2.26; 4.06]) with a similar level of heterogeneity (I2 = 97%). We performed meta-regression analyses for mean age, female gender, alcohol and drug abuse, and smoking cigarettes [see Appendix, Data Sheet 1 (Supplement 2)].

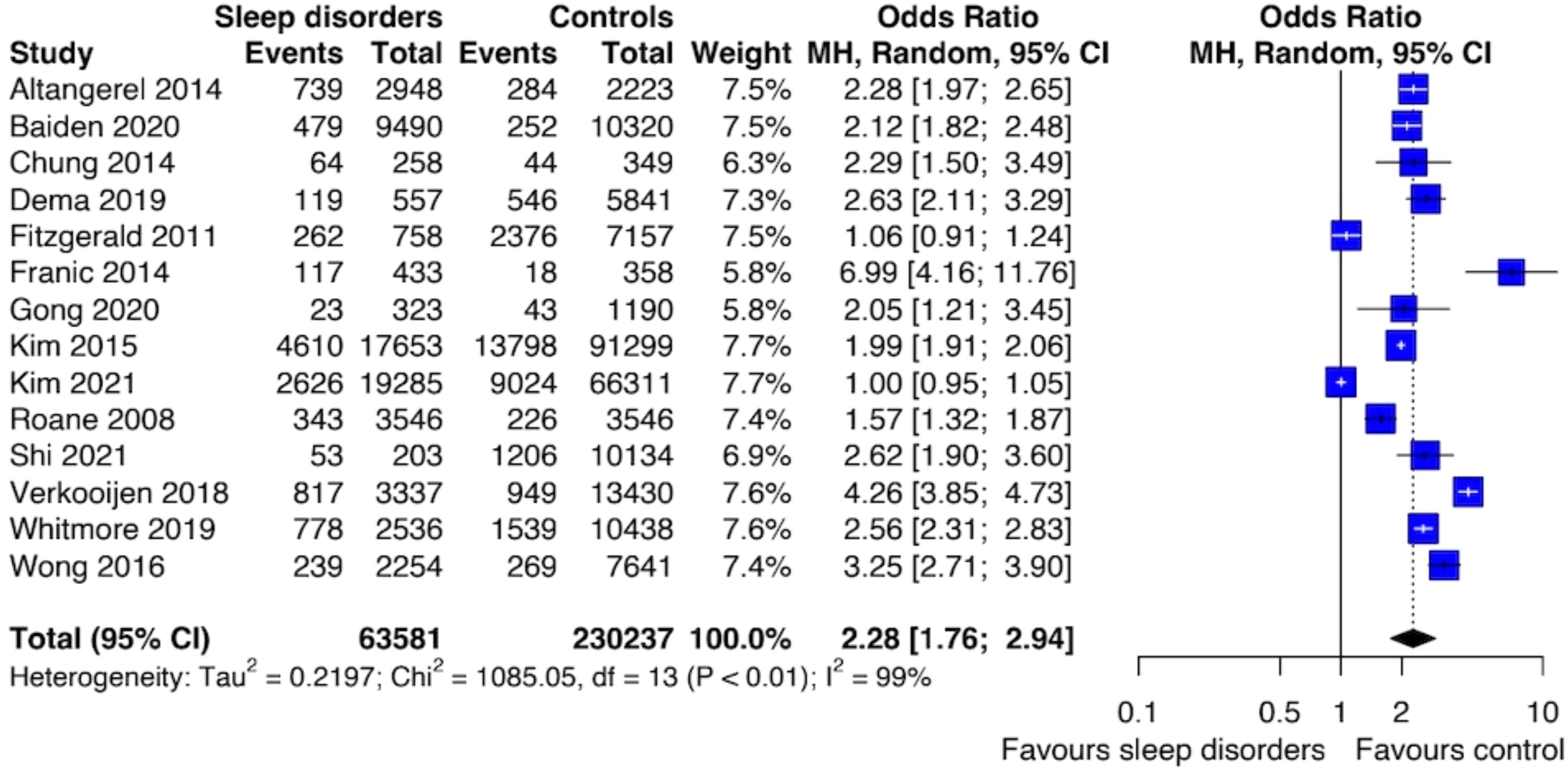

The results of the meta-analysis of the risk of SI were based on 14 studies and showed that individuals with SDs had an increased risk of SI compared to those unexposed to SDs (OR: 2.28; [95% CI 1.76; 2.94]) (Figure 3). The level of heterogeneity was high (I2 = 99%). Also, sensitivity analysis performed by removing studies with increased risk of bias revealed an association between SDs and SI (OR: 2.34; [95% CI: 1.69; 3.23]) with a reduction of heterogeneity (I2 = 94%).

Figure 3. Forest plot of primary analysis between association of suicide ideation and sleep disturbances.

There was no evidence of publication bias in either the meta-analysis, as shown by Egger’s test p-value > 0.05, and by the funnel plots displayed in Data Sheet 1 (Supplement 3).

We could not perform a meta-analysis on NSSI and death by suicide as none of the included studies reported these outcomes.

4 Discussion

The present meta-analysis explored the association between SDs and the risk of suicidal behaviors among adolescents. Our results showed that individuals with SDs had a probability almost tripled for SA and doubled for developing SI compared to controls.

Suicidal behaviors have multifactorial causes, and our findings suggest that adequate sleep may be a protective factor that reduces suicide rates in adolescents. Mechanisms linking sleep to suicidality may differ and vary. One possibility is that being awake at night creates a window of vulnerability for suicidality. Both sleep deprivation and circadian might contribute to the hypoactivation of the frontal lobe, associated with reduced problem-solving abilities and increased impulsive behavior, possibly increasing suicide risk (45). Further, the serotoninergic system has been proposed to mediate the association between SDs and suicide (46). A previous study showed that the prefrontal cortex exhibited low serotonin synthesis in suicide attempters compared to healthy controls (47). Lower neuron density and deficient serotonin input in the prefrontal cortex, which controls executive function, may contribute to impulsive and aggressive traits that are associated with suicidal behaviors (48). Serotonin and its brain receptors also play a crucial role in sleep-wake regulation. Serotonin secretion is highest during wakefulness and decreases during sleep (49). Increasing evidence suggests that SDs result in loss of sensitivity or desensitization of postsynaptic serotonin receptors (50). Under these scenarios, SDs might lead to a loss of serotonin function and thus adversely affect impulse control, which increases the likelihood of suicide. Explanations for the relation between SDs and increased suicidality are currently speculative.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors peak in mid-adolescence and subsequently decline in late adolescence. This observed pattern aligns with previous research findings, indicating significant developmental shifts in these phenomena during the teenage years (51). Preventive interventions for SI and SA in adolescents, particularly those without prior psychiatric treatment, are currently underdeveloped.

SDs are common in people who use specialist mental health services (52). The important role of SDs and their relation with suicidal behaviors emerges in several clinical populations, such as bipolar, schizophrenia, depressive, and anxiety disorders (53, 54). Research suggests improving sleep in people experiencing psychosis could reduce symptoms and improve functioning, however, patients frequently accept SDs as an inevitable part of their condition (55).

Given the findings of this study, the presence of SDs in adolescents may trigger the need for further evaluation of increased risk for suicide. A comprehensive suicide risk assessment may include evaluating sleep quality and maintenance. Screening measures such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which assesses sleep quality, efficiency, duration, disturbances and has good reliability and validity in detecting SDs, may assist in this effort (56). A suicide risk assessment that includes an evaluation of SDs may not only add to the estimation of risk but may also provide a potential target for intervention.

Recognizing the challenges in screening and treating these behaviors in nonclinical samples, this meta-analysis emphasizes the potential role of interventions such as sleep hygiene and behavioral counseling. Sleep hygiene interventions can promote healthy sleep patterns by advocating consistent sleep schedules, caffeine avoidance before bedtime, avoidance of smartphone use in bed, and creating a conducive sleep environment (57). Furthermore, problem-solving and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have shown promise in reducing repeated self-harm and suicidal ideation within a year, though engaging adolescents in these treatments can be challenging (58). Indeed, CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) has also been shown to be an effective non-pharmacological treatment for SDs (59). CBT-I typically consists of cognitive components such as cognitive restructuring, stress management, problem-solving skills, sleep education, and one or more behavioral components such as sleep restriction, relaxation training, and increasing activity levels (60). Behavioral counseling, which aims to increase homeostatic sleep drive and normal circadian rhythms, is also known to be effective in treating children and adolescents with SDs (61).

Timely intervention, before the appearance of suicide behaviors, remains a crucial consideration in mitigating the risk associated with SDs.

Our study has several limitations. Cohort and cross-sectional studies generally recruited individuals with no current suicide behaviors and collected data on SDs and suicide behaviors retrospectively through rating scales, while case-control studies recruited individuals based on current suicide behaviors and compared them with controls, collecting SDs retrospectively. Due to the cross-sectional design of most of the studies included in this meta-analysis, a causal link between SDs and suicide risk cannot be established; therefore, these results should be regarded as hypothesis-generating. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies to elucidate the cumulative contribution of risk factors to SI and SA prediction. Otherwise, by examining data from cross-sectional research, this study emphasizes the role of SDs in leading to the risk of SA and SI. Future research should also investigate the causal association between sleep disruptions and juvenile SA, for example, using more precise measures of SDs and suicidality, prospective designs, or other methods exploiting instrumental variables, such as Mendelian randomization. Finally, future research should aim to investigate the specific impacts of various types of SDs on suicidal behaviors to provide a more nuanced understanding of these associations.

Despite the limitations highlighted, our results have relevant implications for clinical practice and policy. SDs in adolescents are a red flag that should be intercepted by pediatrists and school counters to guarantee an in-depth study of mental health for early recognition of the suicide risk associated with it. Moreover, SDs and mood changes are among the clinical criteria for early risk recognition for bipolar disorder and adolescence represents a typical moment of the first onset of the symptoms that frequently are undiagnosed (62, 63).

Preventive interventions for SI and SA in adolescents, particularly those without prior psychiatric treatment, are currently underdeveloped.

5 Conclusion

This study documents the role of SDs in influencing the risk of suicidal behaviors by analyzing data from many adolescents not diagnosed with psychiatric disorders.

Regarding public health implications, our findings highlight the importance of screening and managing SDs, particularly insomnia, warranting future research on the impact of that on suicide prevention. Additional prospective studies are required to establish the causal relationship between SDs and youth suicide plans and attempts using reliable SDs and suicidality measures.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. MG: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. GR: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. MM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. LP: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. SF: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. DD: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. GV: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. FS: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. CF: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. AM: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. MP: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology. GO: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology. FP: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. GG: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. GP: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The publication of this article was support by the “Ricerca Corrente” funding from the Italian Ministry of Health.

Conflict of interest

GP has received honoraria for advisory board and consulting fees from Bioprojet, Jazz, Takeda, and Idorsia. FP has received honoraria for presentations from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, for participation in the advisory board by Tadeka, and for meeting attendance support from Bioprojet.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1341686/full#supplementary-material

References

1. World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019 (2021). Available online at: https://wwwwhoint/publications/i/item/9789240026643 (Accessed June 16, 2021).

2. Simcock G, Andersen T, McLoughlin LT, Beaudequin D, Parker M, Clacy. A, et al. Suicidality in 12-year-olds: The interaction between social connectedness and mental health. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. (2021) 52:619–27. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01048-8

3. Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2014) . 44:273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070

4. Sharp C, Wall K. Personality pathology grows up: adolescence as a sensitive period. Curr Opin Psychol. (2018) . 21:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.11.010

5. World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A global imperative (2014). Available online at: https://wwwwhoint/publications/i/item/9789241564779 (Accessed August 17, 2014).

6. Cheng Y, Tao M, Riley L, Kann L, Ye L, Tian X, et al. Protective factors relating to decreased risks of adolescent suicidal behaviour. Child Care Health Dev. (2009) 35:313–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00955.x

7. Lavie P. Sleep disturbances in the wake of traumatic events. N Engl J Med. (2000) 345:1825–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012893

8. Dohnt H, Gradisar M, Short MA. Insomnia and its symptoms in adolescents: comparing DSM-IV and ICSD-II diagnostic criteria. J Clin Sleep Med. (2012) . 8:295–9. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1918

9. Hysing M, Pallesen S, Stormark KM, Lundervolt AJ, Sivertesen B. Sleep patterns and insomnia among adolescents: a population-based study. J Sleep Res. (2013) 22:549–56. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12055

10. Tarokh L, Saletin JM, Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescence: Physiology, cognition and mental health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2016) 70:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.008

11. Crowley SJ, Van Reen E, LeBourgeois MK, Acebo C, Tarokh L, Seifer R, et al. A longitudinal assessment of sleep timing, circadian phase, and phase angle of entrainment across human adolescence. PloS One. (2014) 9:e112199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112199

12. Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. (2015) . 1:40–3. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010

13. Nosetti L, Lonati I, Marelli S, Salsone M, Sforza M, Castelnuovo A, et al. Impact of pre-sleep habits on adolescent sleep: an Italian population-based study. Sleep Med. (2021) 81:300–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.054

14. Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J Psychosom Res. (2002) 53:561–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00446-4

15. Palmer CA, Oosterhoff B, Bower JL, Kaplow JB, Candice AA. Associations among adolescent sleep problems, emotion regulation, and affective disorders: Findings from a nationally representative sample. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) . 96::1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.09.015

16. Sivertsen B, Harvey AG, Pallesen S, Hysing M. Mental health problems in adolescents with delayed sleep phase: results from a large population-based study in Norway. J Sleep Res. (2015) . 24:11–8. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12254

17. Bernert RA, Kim JS, Iwata NG, Perlis ML. Sleep disturbances as an evidence-based suicide risk factor. Curr Psychiatry Rep. (2015) . 17:554. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0554-4

18. Chiu H-Y, Lee H-C, Chen P-Y, Lai YF, Tu FK. Associations between sleep duration and suicidality in adolescents: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2018) . 42:119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.07.003

19. Kearns JC, Coppersmith DDL, Santee AC, Insel C, Pigeon WR, Glenn CR, et al. Sleep problems and suicide risk in youth: A systematic review, developmental framework, and implications for hospital treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2020) . 63:141–51. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.09.011

20. Liu X, Liu ZZ, Wang ZY, Yang Y, Liu BP, Jia CX, et al. Daytime sleepiness predicts future suicidal behavior: a longitudinal study of adolescents. Sleep. (2019) 42:zsy225. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy225

21. Pigeon WR, Pinquart M, Conner K. Meta-analysis of sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Clin Psychiatry. (2012) . 73:e1160–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07586

22. Malik S, Kanwar A, Sim LA, Prokop LJ, Wang Z, Benkhadra K, et al. The association between sleep disturbances and suicidal behaviors in patients with psychiatric diagnoses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. (2014) . 25:18. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-18

23. Bernert RA, Joiner TE. Sleep disturbances and suicide risk: a review of the literature. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2007) . 3:735–43. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s1248

24. Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression in adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. (2014) 18:521–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.006

25. Perlis ML, Grandner MA, Chakravorty S, Bertner RA, Brown GK, Thase ME, et al. Suicide and sleep: is it a bad thing to be awake when reason sleeps? Sleep Med Rev. (2016) 29:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.10.003

26. Bernert RA, Joiner TE JR, Cukrowicz KC, Schmidt NB, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep. (2005) 28:1135–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1135

27. Leyton M, Paquette V, Gravel P, Rosa-Neto P, Weston F, Diksic M, et al. [amp]]alpha;- [11C] methyl-L-tryptophan trapping in the orbital and ventral medial prefrontal cortex of suicide attempters. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (2006) 16:220–3. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.09.006

28. Gujar N, Yoo SS, Hu P, Walker MP. Sleep deprivation amplifies reactivity of brain reward networks, biasing the appraisal of positive emotional experiences. J Neurosci. (2011) 31:4466–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3220-10.2011

29. Dahl RE, Lewin DS. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. J Adolesc Health. (2002) 31:175–84. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2

30. Millman RP, Working Group on Sleepiness in Adolescents/Young Adults; and AAP Committee on Adolescence. Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics. (2005) 115:1774–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0772

31. Fredriksen K, Rhodes J, Reddy R, Way N. Sleepless in Chicago: tracking the effects of adolescent sleep loss during the middle school years. Child Dev. (2004) 75:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00655.x

32. Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Restricted sleep among adolescents: prevalence, incidence, persistence, and associated factors. Behav Sleep Med. (2011) 9:18–30. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.533991

33. Uccella S, Cordani R, Salfi F, Gorgoni M, Scarpelli S, Gemignani A, et al. Sleep deprivation and insomnia in adolescence: implications for mental health. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:569. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13040569

34. Kaldenbach S, Leonhardt M, Lien L, Bjærtnes AA, Strand TA, Holten-Andersen MN. Sleep and energy drink consumption among Norwegian adolescents–a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:534. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12972-w

35. Chiu VW, Ree M, Janca A, Waters A. Sleep in schizophrenia: exploring subjective experiences of sleep problem, and implications for treatment. Psychiatr Q. (2016) . 87:633–48 569. doi: 10.1007/s11126-015-9415-x

36. Liu X, Yang Y, Liu ZZ, Jia CX. Longitudinal associations of nightmare frequency and nightmare distress with suicidal behavior in adolescents: mediating role of depressive symptoms. Sleep. (2021) 44:zsaa130. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa130

37. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. (2021) 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

38. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. (1986) 1:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

39. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) . 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186

40. Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. (2011) . 22:343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002

41. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and Fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias on meta-analyses. Biometrics. (2000) . 56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x

42. Sterne JA, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing reporting biases. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention. John Wiley & Sons (2008).

43. Sutton AJ, Duval SJ, Tweedie RL, Abrams KR, Jones DR. Empirical assessment of effect of publication bias on meta-analyses. BMJ. (2000) . 10:1574–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1574

44. Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J, Olkin I. Adjusting for publication bias in the presence of heterogeneity. Stat Med. (2003) . 22:2113–26. doi: 10.1002/sim.1461

45. Balduzzi S, Rùcker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: apractical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. (2019) 22:153–60. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117

46. Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analysis in R with the metafor package. J Stat Software. (2010) . 5:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03

47. Jang SI, Lee KS, Park EC. Relationship between current sleep duration and past suicidal ideation or attempt among Korean adolescents. J Prev Med Public Health. (2013) . 46:329–35. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.6.329

48. Kohyama J. Sleep, serotonin and suicide in Japan. J Physiol Anthropol. (2011) . 30:1–8. doi: 10.2114/jpa2.30.1

49. Kerr DCR, Owen LD, Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Prevalence of suicidal ideation among boys and men assessed annually from ages 9 to 29 years. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2008) . 38:390–402. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.390

50. Underwood MD, Kassir SA, Bakalian MJ, Galfavy H, Mahn JJ, Arango V, et al. Density and Serotonin receptor binding in prefrontal cortex in suicide. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2012) . 15:435–47. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000691

51. Portas CM, Bjorvatn B, Ursin R. Serotonin and the sleep/wake cycle: special emphasis on microdyalisis studies. Progr Neurobiol. (2000) . 60:15–35. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00097-5

52. Roman V, Walstra I, Luiten PG, Meerlo P. Too little sleep gradually desensitizes the serotonin 1A receptor system. Sleep. (2005) . 28:1505–10.

53. Rueter MA, Kwon H. Developmental trends in adolescent suicidal ideation. J Res Adolesc. (2005) . 15:205–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00092.x

54. O’Sullivan M, Rahim M, Hall C. The prevalence and management of poor sleep quality in a secondary care mental health population. J Clin Sleep Med. (2015) . 11:111–6. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4452

55. Gershon A, Singh MK. Sleep in adolescents with bipolar I disorder: stability and relation to symptom change. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2017) . 46:247–57. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188699

56. Urrila AS, Karlsson L, Kiviruusu O, Pelkonen P, Strandholm T, Marttunen M, et al. Sleep complaints among adolescent outpatients with major depressive disorders. Sleep Med. (2012) . 13:816–23. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.04.012

57. Waite F, Shaeves B, Isham L, Reeve S, Freeman D. Sleep and schizophrenia: from epiphenomenon to treatable causal target. Schizophr Res. (2020) . 221:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.11.014

58. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) . 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

59. John B, Bellipady SS, Bhat SU. Sleep promotion program for improving sleep behaviors in adolescents: A randomized controlled pilot study. Scientifica. (2016), 80134131. doi: 10.1155/2016/8013431

60. Sayal K, Roe J, Ball H, Atha C, Hughes CK, Guo B. Feasibility of a randomised controlled trial of remotely delivered problem-solving cognitive behaviour therapy versus usual care for young people with depression and repeat self-harm: lessons learnt (e-DASH). BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:42. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-2005-3

61. Ong JC, Shapiro SI, Manber R. Combining mindfulness meditation with cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: a treatment-development study. Behav Ther. (2008) . 39:171–82. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.002

62. Morin C, Bastien C, Savard J. Current status of cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia: evidence for treatment effectiveness and feasibility. In: Perlis M, Lichstein KL, editors. Treating Sleep Disorders: Principles and practice of behavioral sleep medicine. John Wiley & Sons, New York (2003). p. 262–85.

63. Vieta E, Salagre E, Grande I, Carvalho AF, Fernandes BS, Berk M, et al. Early intervention in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. (2018) 175:411–26. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17090972

64. Altangerel U, Liou JC, Yeh PM. Prevalence and predictors of suicidal behavior among mongolian high school students. Community Ment Health J. (2014) 50:362–72. doi: 10.1007/s10597-013-9679-0

65. Baiden P, Tadeo SK, Tonui BC, Seastrunk JD, Boateng GO. Association between insufficient sleep and suicidal ideation among adolescents. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112–79. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112179

66. Chung MS, Chiu HJ, Sun WJ, Lin CN, Kuo CC, Huang WC, et al. Association among depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, sleep disturbance, and suicidal ideation in Taiwanese adolescents. Asia Pac Psychiatry. (2014) 6(3):319–25. doi: 10.1111/appy.12026

67. Fitzgerald CT, Messias E, Buysse DJ. Teen sleep and suicidality: results from the youth risk behavior surveys of 2007 and 2009. J Clin Sleep Med. (2011) 7:351–6. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1248

68. Franić T, Kralj Ž, Marčinko D, Knez R, Kardum G. Suicidal ideations and sleep-related problems in early adolescence. Early Interv Psychiatry. (2014) 8:155–62. doi: 10.1111/eip.12032

69. Gong Q, Li S, Wang S, Li H, Han L. Sleep and suicidality in school-aged adolescents: a prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 287:112918. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112918

70. Jacob L, Oh H, Koyanagi A, Smith L, Kostev K. Relationship between physical conditions and attempted or completed suicide in more than 9,300 individuals from the United Kingdom: a case-control study. J Affect Disord. (2020) 274:457–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.116

71. Kim JH, Park EC, Lee SG, Yoo KB. Associations between time in bed and suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts in korean adolescents. BMJ Open. (2015) 5. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008766

72. Kim CW, Jeong SC, Hwang SW, Hui S, Kim SH. Evidence of sleep duration and weekend sleep recovery impact on suicidal ideation in adolescents with allergic rhinitis. J Clin Sleep Med. (2021) 17:1521–32. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9262

73. Lin HT, Lai CH, Perng HJ, Chung CH, Wang CC, Chen WL, et al. Insomnia as an independent predictor of suicide attempts: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry (2018) 18:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1982-4

74. Roane BM, Taylor DJ. Adolescent insomnia as a risk factor for early adult depression and substance abuse. Sleep. (2008) 31:1351–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.10.1351

75. Shi X, Zhu Y, Wang S, Wang A, Chen X, Li Y, et al. The prospective associations between different types of sleep disturbance and suicidal behavior in a large sample of Chinese college students. J Affect Disord. (2021) 279:380–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.005

76. Verkooijen S, De Vos N, Bakker-Camu BJ, Branje SJ, Kahn RS, Ophoff RA, et al. Sleep disturbances, psychosocial difficulties, and health risk behavior in 16,781 Dutch adolescents. Acad Pediatr. (2018) 18:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.11.002

77. Weis D, Rothenberg L, Moshe L, Brent DA, Hamdan S. The effect of sleep problems on suicidal risk among young adults in the presence of depressive symptoms and cognitive processes. Arch Suicide Res. (2015) 19:321–34. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1028162

78. Whitmore LM, Smith TC. Isolating the association of sleep, depressive state, and other independent indicators for suicide ideation in united states teenagers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2019) 23:471–90. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12468

79. Wong MM, Brower KJ, Craun EA. Insomnia symptoms and suicidality in the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement. J Psychiatr Res. (2016) 81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.015

Keywords: suicide, sleep disturbances, adolescence, insomnia, sleep disorders, suicidal ideation

Citation: Baldini V, Gnazzo M, Rapelli G, Marchi M, Pingani L, Ferrari S, De Ronchi D, Varallo G, Starace F, Franceschini C, Musetti A, Poletti M, Ostuzzi G, Pizza F, Galeazzi GM and Plazzi G (2024) Association between sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 15:1341686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1341686

Received: 20 November 2023; Accepted: 11 September 2024;

Published: 02 October 2024.

Edited by:

Mehmet Y. Agargün, Istanbul Medipol University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Shuang-Jiang Zhou, Peking University HuiLongGuan Clinical Medical School, ChinaStefania Sette, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2024 Baldini, Gnazzo, Rapelli, Marchi, Pingani, Ferrari, De Ronchi, Varallo, Starace, Franceschini, Musetti, Poletti, Ostuzzi, Pizza, Galeazzi and Plazzi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Valentina Baldini, dmFsZW50aW5hLmJhbGRpbmlAdW5pbW9yZS5pdA==

Valentina Baldini

Valentina Baldini Martina Gnazzo2

Martina Gnazzo2 Giada Rapelli

Giada Rapelli Mattia Marchi

Mattia Marchi Luca Pingani

Luca Pingani Silvia Ferrari

Silvia Ferrari Fabrizio Starace

Fabrizio Starace Christian Franceschini

Christian Franceschini Alessandro Musetti

Alessandro Musetti Giovanni Ostuzzi

Giovanni Ostuzzi Gian Maria Galeazzi

Gian Maria Galeazzi Giuseppe Plazzi

Giuseppe Plazzi