- 1Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, England, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Forensic and Neurodevelopmental Science, School of Academic Psychiatry, King’s College London, London, England, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Centre, School of Mental Health & Psychological Sciences, King’s College London, London, England, United Kingdom

Complex trauma is associated with complex-posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). While dissociative processes, developmental factors and systemic factors are implicated in the development of CPTSD, there are no existing systematic reviews examining the underlying pathways linking complex trauma and CPTSD. This study aims to systematically review evidence of mediating factors linking complex trauma exposure in childhood (birth to eighteen years of age) and subsequent development of CPTSD (via self-reports and diagnostic assessments). All clinical, at-risk and community-sampled articles on three online databases (PsycINFO, MedLine and Embase) were systematically searched, along with grey literature from ProQuest. Fifteen articles were eligible for inclusion according to pre-determined eligibility criteria and a search strategy. Five categories of mediating processes were identified: 1) dissociative processes; 2) relationship with self; 3) emotional developmental processes; 4) social developmental processes; and 5) systemic and contextual factors. Further research is required to examine the extent to which targeting these mediators may act as mechanisms for change in supporting individuals to heal from complex trauma.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, identifier CRD42022346152.

Introduction

Complex post-traumatic stress

Experiences in early life have a lasting impact on psychological development, even if not consciously remembered (1, 2). When these experiences are traumatic – when they overwhelm an individual’s capacity to cope – the consequences are often severe (3). When the trauma is ‘complex’ – when it is repeated and prolonged, as in childhood abuse or domestic violence – it is associated with a complex post-traumatic stress response (4, 5). The ICD-11 conceptualises this as ‘Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder’ (‘CPTSD’) and characterises this response through two domains – a ‘Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder’ domain (‘PTSD’; 1) traumatic re-experiencing; 2) hypersensitivity to potential threat, and; 3) behavioural avoidance of situations which may trigger re-experiencing) and a ‘Disturbances in Self-Organisation’ domain (‘DSO’; 1) emotion dysregulation; 2) a persistent negative self-perception and; 3) interpersonal difficulties; 6).

Prevalence estimates for CPTSD in the general population range from 2.6-7.7% (7, 8; 9) and are higher for at-risk populations such as adults with lived experience of psychological difficulty (12.72%; 10) and refugees (between 2.2 and 50.9%; 11). CPTSD greatly impacts psychosocial functioning, particularly through leading to a fear of relationships, relationship depression, and preoccupations with intimate relationships (12).

Despite this, there is a relative paucity of research investigating the mechanisms through which complex trauma and CPTSD are associated (13). Furthermore, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) do not yet provide specific guidance on evidence-based CPTSD interventions (14). Therefore, there is a need for further research to examine the mechanisms involved in the development of CPTSD to inform clinical understanding and intervention.

Identifying mechanisms and pathways linking complex trauma and CPTSD

Currently, there are no existing systematic reviews examining the underlying pathways linking complex trauma and CPTSD. Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses have focused primarily on establishing evidence for the CTPSD construct (15), the prevalence of CPTSD in specific populations (11), and exploring the efficacy of interventions targeting CPTSD (16). While these reviews provide key information, there is a need for further improving understandings of the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD.

Evidence suggests that factors involving dissociation (4), child development (17), attachment security (18; 19), and wider systemic factors such as family environment (20, 21) may explain the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD. Due to the nature of these factors and how they theoretically relate to the domains of CPTSD (i.e. interpersonal difficulties), it is possible that some identified mediators may conceptually overlap with CPTSD outcomes. Mediation analyses help identify which factors may influence the effects of an antecedent event (i.e. experiencing complex trauma) towards a particular outcome (i.e. CPTSD; 22). Identifying mediators is therefore one approach to understanding the underlying pathways and mechanisms linking complex trauma and CPTSD, and will provide an important first step in subsequent identification of causal mechanisms in the development of CPTSD (23).

The current review

This systematic review therefore aims to examine and collate evidence regarding the underlying mechanisms and pathways mediating the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD. All observational and experimental studies which have examined factors mediating the association between childhood complex trauma and subsequent presentation of CPTSD in childhood, adolescence, or adulthood, will be included.

Methodology

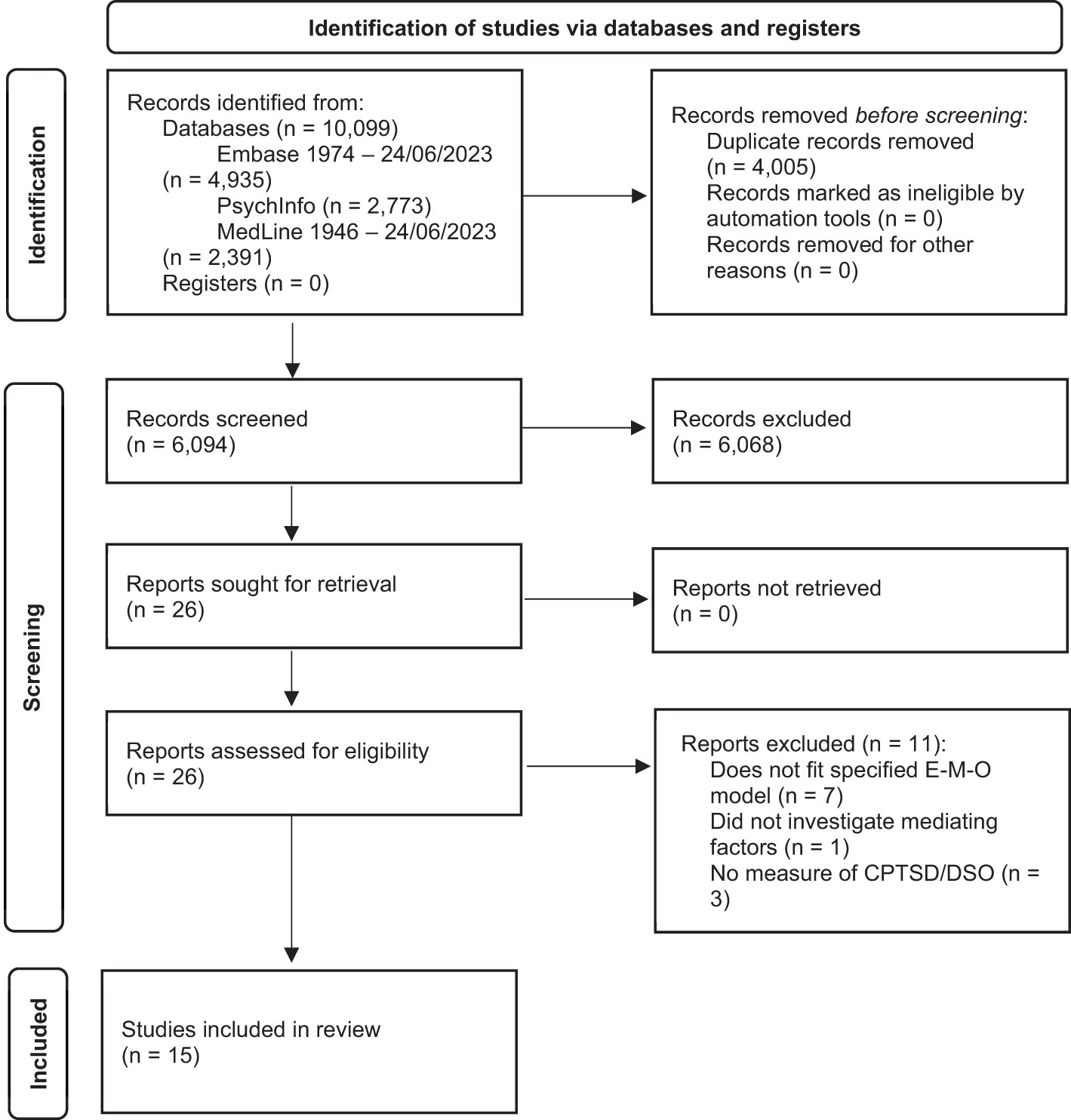

This review was conducted with the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (24) and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022346152).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The definition of ‘complex trauma’ used was: “Exposure to multiple and/or prolonged traumatic events – often of an invasive, interpersonal nature” (National Child Traumatic Stress Network, 17). Observational and experimental studies were included based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) Clinical, at-risk or community samples in childhood, adolescence, adulthood, older adulthood; 2) Complex trauma experienced during childhood and adolescence (i.e. birth-18 years), assessed with a validated measure – retrospective self-reports and clinical interviews. There were no other timing requirements for trauma exposures; 3) Demonstration of established CPTSD outcomes with validated CPTSD assessments – self-reports and diagnostic assessments; 4) Reporting of mediators linking complex trauma and CPTSD; 5) Inclusion of peer-reviewed articles and grey literature. Exclusion criteria were: 1) Presence of singular or discrete trauma; 2) Articles not written in or translated to English. As previous research has demonstrated that the CPTSD, PTSD and BPD diagnostic constructs describe separate clinical presentations, despite apparent similarities (25, 26), articles solely examining singular-event PTSD and BPD were not included in the inclusion/exclusion criteria or search process.

Information sources

Three online databases were selected (PsycINFO, MedLine and Embase) based on clinical research emphases. These were searched up to and including 24/06/2023. To reduce article bias associated with solely reviewing published research (27) grey literature was retrieved from ProQuest. A forward and backward search was conducted to ensure all potentially relevant articles were identified. All identified articles were exported to EndNote.

Search strategy

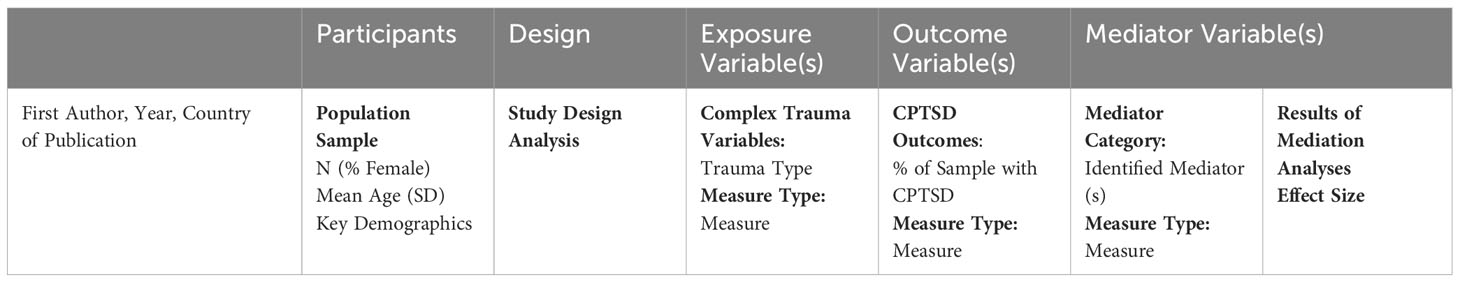

A search strategy was developed using the PICO framework for systematic reviews to identify studies which examined mediators of the relationship between complex trauma exposure and CPTSD (see Table 1; 28). An ‘A’ (‘Analysis’) component was added to the framework to include mediation analyses in the search.

Table 1 The search terms used to identify articles which examined mediators of the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD.

Study selection

The primary author screened the titles and abstracts of all exported articles for eligibility. A random sample of 20% of exported articles were then screened by a separate rater. Inter-rater reliability was very high (Cohen’s κ = 1.00). Following establishment of inter-rater reliability, eligible studies were fully screened by the primary author and another random 20% were screened by the second rater. Again, inter-rater reliability was very high (Cohen’s κ = 1.00).

Methodological quality

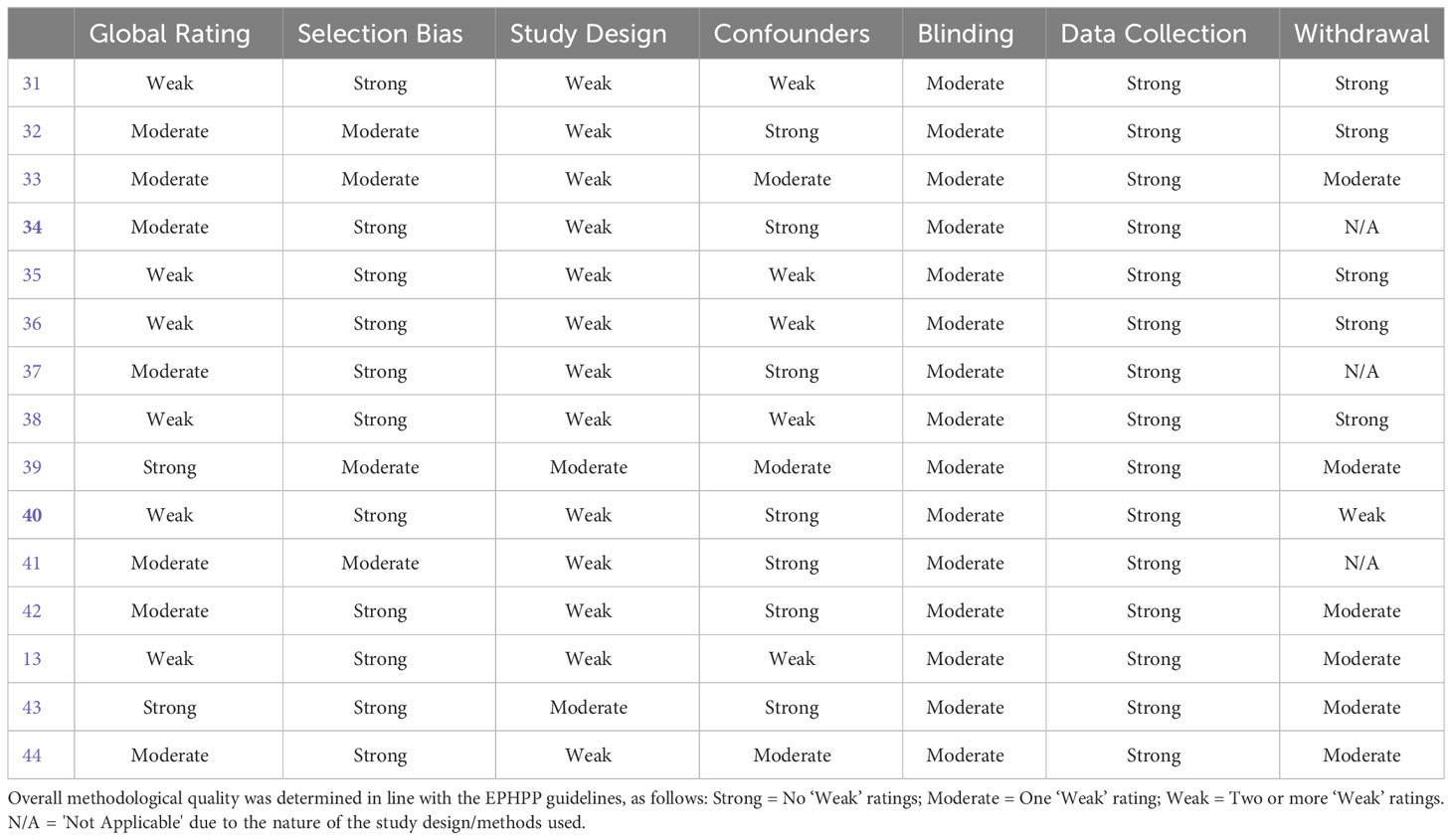

The methodological quality of all included articles was assessed by separate raters via the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (29). Articles were rated as ‘Overall Strong’ if there were no individual ‘Weak’ ratings, ‘Overall Moderate’ if there was one individual ‘Weak’ rating, and ‘Overall Weak’ if there were two or more individual ‘Weak’ ratings.

Data extraction and analyses

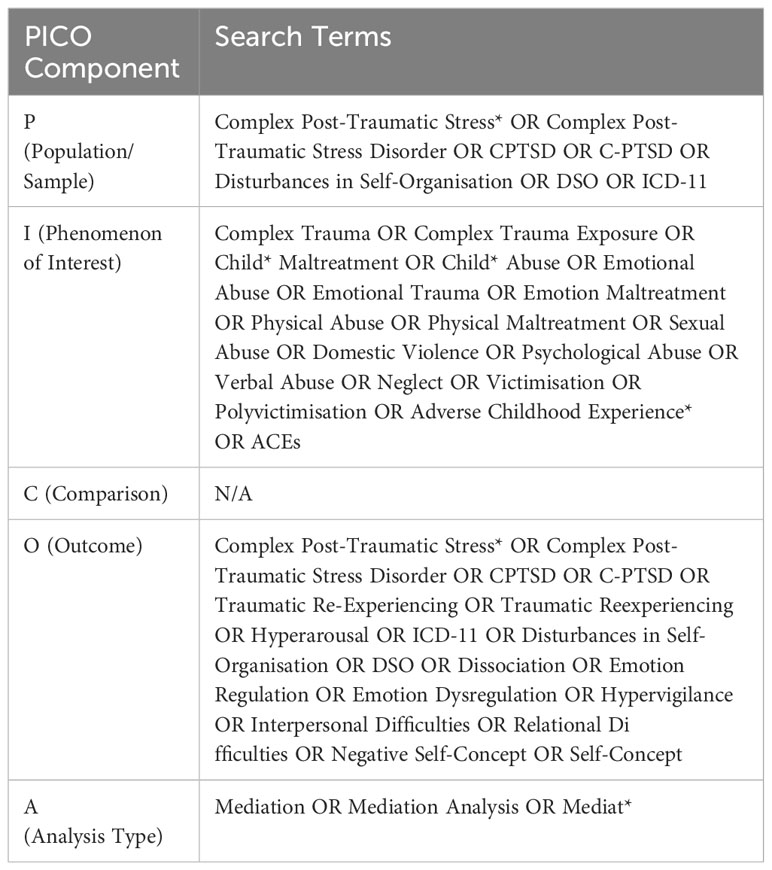

As shown through the custom data collection form (Appendix A) data was extracted regarding: Article Characteristics; Participants; Design; Exposure Variables; Outcome Variables; and Mediator Variables. Data were then analysed through a narrative synthesis approach (30). This involved: 1) describing results mediator of the association between complex trauma exposure in childhood and CPTSD; 2) constructing mediator categories based on theoretical relationships between identified mediators.

Results

Study selection

The final review consisted of fifteen articles. The results at each stage of the search and screening process are represented in Figure 1.

Quality assessment

Through the EPHPP Guidelines (29), the majority of studies were assessed as having overall “Moderately Strong” methodologies (k = 9). The remaining studies were assessed as having overall “Weak” methodologies (k = 6). Detailed ratings from the quality assessment are provided in Table 2.

Table 2 Results of the quality assessment of studies included in the review using the EPHPP Quality Assessment Tool.

Sample characteristics

The majority of articles were European, with one article published in China and one article published in the USA. A mixture of clinical (k = 7), at-risk (k =5) and community samples (k = 3) were utilised. At-risk samples experienced social adversities such as being looked after in foster care facilities, experiencing homelessness, experiencing enforced occupation measures, and previous experience of complex trauma. Participants varied greatly in age, ranging from adolescence to older adulthood at time of participation (mean age = 40.27 years, SD = 10.47, range = 14-77). Participants had varying levels of educational attainment (i.e. secondary school, university-educated and post-graduate educated) and a range of marital statuses (i.e. single, partnered, married). Only three articles reported information on participants’ racial backgrounds and five articles reported information on participants’ geographical backgrounds. In articles where these variables were reported, participants came from a variety of racial (i.e. white, Latino, Asian, black, mixed) and geographical backgrounds (i.e. Austrian, UK, Western Europe, African Caribbean, African). No articles reported information on participants’ sexualities.

The majority of articles described studies utilising a cross-sectional design (k= 14), with one study utilising a case-control study design. There was considerable heterogeneity in the types of statistical analyses undertaken (i.e. simple mediation analyses, multiple mediation analyses, path analyses, multigroup path analyses, network analysis), with further variation in the reporting of outcomes. Despite this, several mediators of the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD were identified consistently across articles, allowing for the meaningful categorising of mediators. All articles were published from 2013 onwards.

Complex trauma (exposure) and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (outcome)

Complex trauma was mainly assessed retrospectively through self-reports, the most common being the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; 18). All articles identified childhood complex trauma which occurred during childhood, but only one study distinguished between specific exposure timepoints (i.e. childhood and adolescence; 34). The primary identified type of complex trauma was childhood abuse (physical, emotional and sexual) and neglect (physical and emotional). All articles reported an association between complex trauma and CPTSD. CPTSD was mainly assessed through self-report questionnaires, most commonly with the International Trauma Questionnaire (45). The majority of articles (k= 9) examined the PTSD and DSO domains of CPTSD as distinct variables, whereas the remaining articles (k= 6) examined CPTSD as a composite variable comprising both domains.

Mediators of complex trauma and CPTSD

Through a narrative synthesis approach, twenty-four mediators of the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD were identified and described. These were categorised as: 1) ‘Dissociative Processes’, 2) ‘Relationship with Self, 3) ‘Emotional Development’, 4) ‘Social Development’, and 5) ‘Systemic and Contextual Factors’. Each category contained a variety of risk and protective factors. Table 3 details each mediator group and mediator.

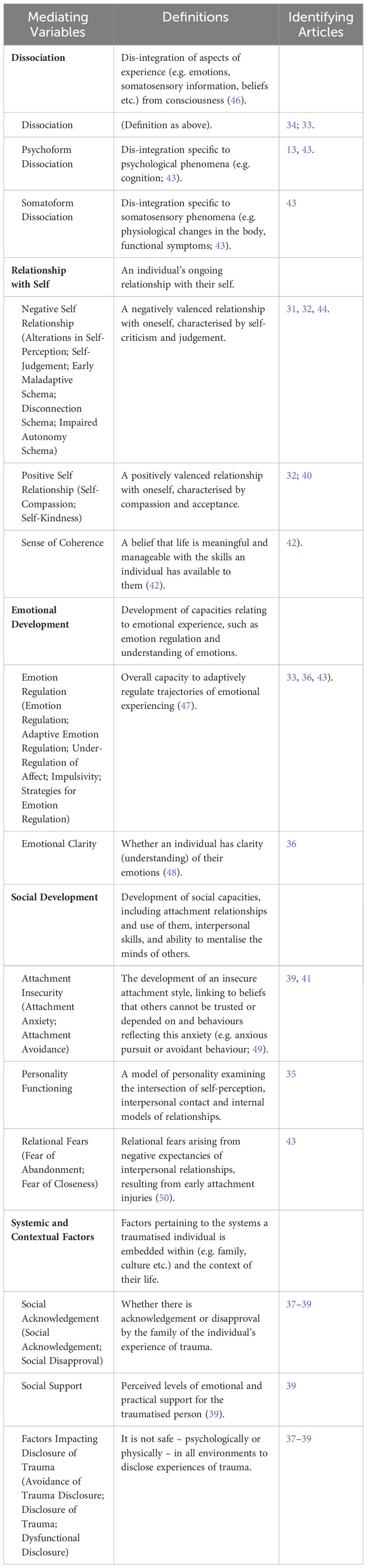

Table 3 Descriptions of mediator categories and individual mediators of complex trauma and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD).

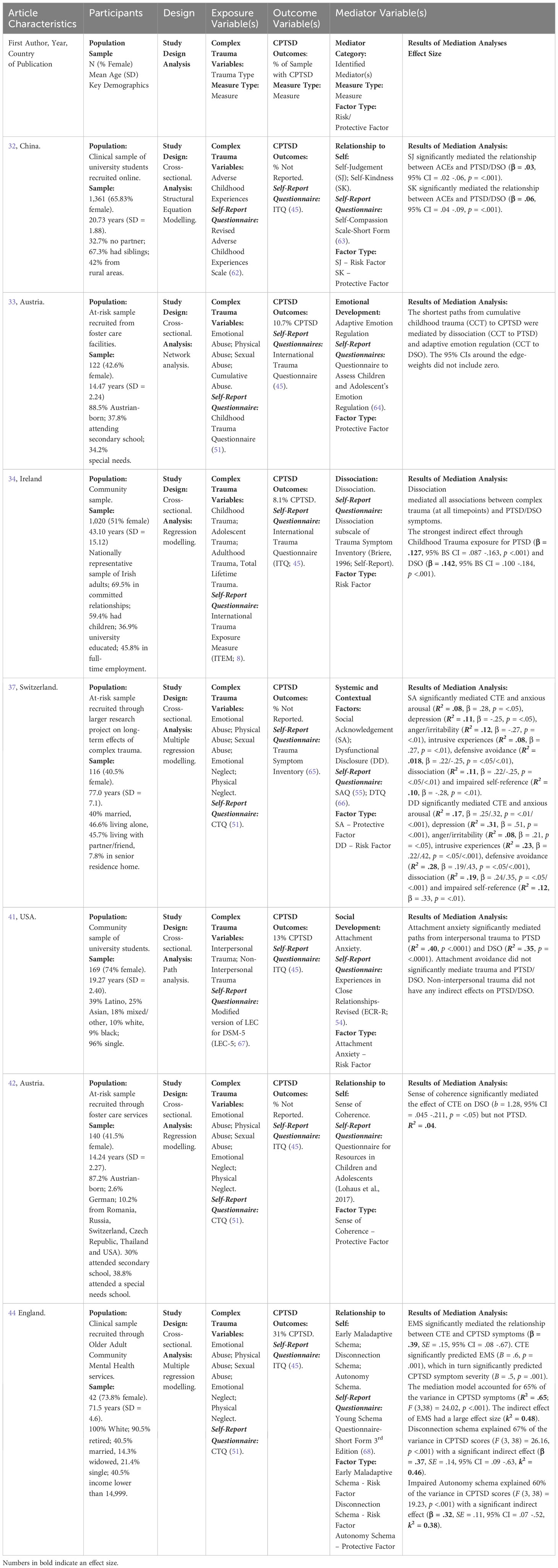

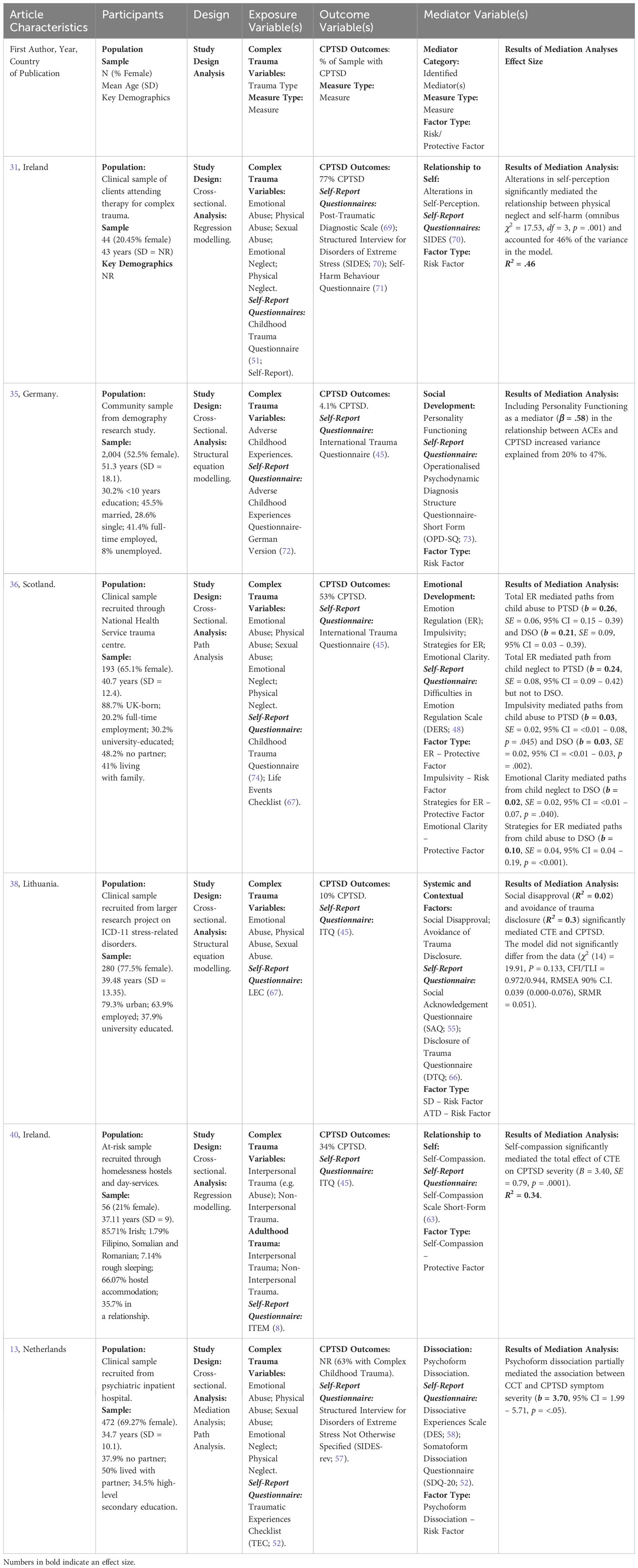

The majority of articles described controlled for confounding variables such as gender, age and social desirability. Inferential statistics for each mediation effect are shown in Tables 4, 5 and 6. A range of small, medium and large effect sizes were identified.

Table 4 Extracted data on study characteristics and results from articles with an EHPP Global Rating of ‘Strong’.

Table 5 Extracted data on study characteristics and results from articles with an EHPP Global Rating of ‘Moderate’.

Table 6 Extracted data on study characteristics and results from articles with an EHPP Global Rating of ‘Weak’.

Dissociation

Four articles examined dissociation, defined either as a single process (i.e. ‘dissociation’) or as two sub-processes (‘psychoform’ and ‘somatoform’ dissociation). All four articles identified statistically significant mediation effects of dissociation in a variety of geographical samples, indicating cross-cultural effects: a nationally representative community sample in Ireland, an at-risk sample of adolescents in foster care in Austria, and two clinical samples from psychiatric inpatient services in the Netherlands. It was found that the strongest mediation effect occurred when exposure to complex trauma was during childhood (as opposed to during adolescence), that dissociation mediated paths specifically from exposure to the PTSD symptom cluster of CPTSD (but not to the DSO symptom cluster), and specifically that the psychoform subtype of dissociation mediates complex trauma and CPTSD association. This effect was identified as being independent of the relationship between complex trauma and BPD.

Relationship with self

Five articles examined processes linked to one’s relationship to self: self-judgement, self-kindness, self-compassion, sense of coherence, early maladaptive schema and alterations in self-perception. Self-compassion was identified as a statistically significant mediator of complex trauma (e.g. abuse) and CPTSD both in a sample of adults in Ireland experiencing homelessness and a community sample of university students in China, demonstrating a cross-cultural effect. Of these, one article demonstrated further specific mediation effects of self-compassion on the associations between complex trauma and both the PTSD and DSO domains of CPTSD. In this same sample of university students, self-judgement additionally mediated the associations between complex trauma and the PTSD and DSO domains. In a clinical sample of older adults accessing community mental health services in England, early maladaptive schemas were further found to mediate the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD with medium-to-large effect sizes. Other articles indicated a mediation effect of self-related factors more specifically between complex trauma and the DSO domain. In an at-risk sample of adolescents in foster care in Austria, sense of coherence mediated the relationship between complex trauma and the DSO domain but not the PTSD domain. Similarly, in a clinical sample of adults in Ireland attending therapy for complex trauma, alterations in self-perception mediated the relationship between complex trauma exposure and a specific form of DSO (i.e. self-harm).

Emotional development

Three articles examined the mediating role of emotional development. Firstly, in a clinical sample of psychiatric inpatients, under-regulation of affect was identified as a mediator of complex trauma exposure and CPTSD. This mediation effect was independent of the association between complex trauma and BPD. Similarly, in an at-risk sample of adolescents in foster care, adaptive emotion regulation was found to be a mediator of the association between exposure and DSO. Lastly, using an adult clinical sample in Scotland, another article identified more specific emotional developmental processes which mediated specific forms of complex trauma and the PTSD and DSO domains: total emotion regulation mediated relationships between child abuse and PTSD/DSO, and mediated the link between child neglect and PTSD; impulsivity mediated the relationship between child abuse, PTSD and DSO; emotional clarity mediated the relationship between child neglect and DSO, and strategies for emotion regulation mediated the relationship between child abuse and DSO.

Social development

Four articles examined the mediating role of social development: personality functioning, attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, fear of abandonment, and fear of closeness. In a nationally representative community sample in Germany, a primarily interpersonal model of personality functioning was found to mediate complex childhood trauma and CPTSD in adulthood at a large effect size. In both a community sample of university students and an at-risk sample of adults, attachment anxiety significantly mediated the relationship between interpersonal trauma and DSO, and was involved in multiple mediation paths from emotional abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect to PTSD and DSO. Furthermore, in a clinical sample of inpatients in a psychiatric hospital in the Netherlands, the relationship between complex trauma exposure and CPTSD was significantly mediated by fear of abandonment and fear of closeness. These mediation effects were identified as independent of the association between complex trauma and BPD.

Systemic and contextual factors

Three articles examined systemic and contextual factors: social disapproval, avoidance of trauma disclosure, social acknowledgement, social support, disclosure of trauma and dysfunctional disclosure. Social disapproval of close family or friends and avoidance of trauma disclosure were found to significantly mediate the association between complex trauma exposure and CPTSD in both a clinical sample and an at-risk sample of adults. In this same at-risk sample, lack of social support was found to mediate complex trauma in childhood and DSO in adulthood. In another at-risk sample of adults, social acknowledgement and dysfunctional disclosure of trauma significantly mediated the following aspects of the PTSD and DSO domains: anxious arousal; depression; anger/irritability; intrusive experiences; defensive avoidance; dissociation; and impaired self-referencing.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This is the first systematic review identifying factors which mediate the relationship between complex trauma in childhood and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). The findings indicate that a multitude of processes mediate this relationship: 1) dissociative processes, 2) an individual’s relationship to self, 3) emotional developmental processes, 4) social developmental processes, and 5) systemic factors contextualising the traumatised individual’s experience. These mediation effects were identified in clinical, at-risk and community samples across a variety of geographical locations. The mediating factors identified in this review are represented in a conceptual multiple mediation model in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Conceptual multiple mediation model of the relationship between complex trauma exposure and complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD). Definitions: ‘PTSD’, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; ‘DSO’, Disturbances in Self-Organisation.

Comparison to previous research

The mediators identified in this review are supported by an extant literature examining the role of these processes in relation to both complex trauma exposure and CPTSD. Previously, dissociation has been conceptualised as a defensive biological capacity which acts as an ‘escape where there is no escape’ (75). It describes the process by which traumatic experiences are split off from consciousness and represented by dis-integrated fragments across different levels of the memory system (46), and is proposed to be responsible for the re-experiencing of trauma through ‘flashbacks’ (34; 76, 77). Additionally, in the context of complex trauma which frequently occurs within attachment relationships, it is likely that traumatic experiences in childhood are internalised as negative meanings about the self (78). Indeed, it has been proposed that childhood complex trauma should be viewed as a developmental process that results in a distorted self-concept (79). Furthermore, previous research suggests that such complex trauma occurring within attachment relationships would interrupt emotional development and the development of social cognition and social information processing (80–83). Lastly, systemic factors contextualising the experience of complex trauma have previously been found to play an important role in the development of CPTSD (20). This is not least because, by their nature, many forms of complex trauma (e.g. childhood abuse) occur within the contexts of relationships themselves.

To an extent, some of these mediating processes overlap with mediating processes involved in other clinical presentations, such as PTSD (i.e. dissociation, emotion dysregulation; 84; 85) and borderline personality disorder (‘BPD’; i.e. attachment insecurity; 86). It is possible that such processes reflect transdiagnostic mechanisms across these clinical presentations (87). Indeed, as PTSD is a required feature of the broader CPTSD construct, some overlap in mediating processes is to be expected; a meta-analysis has indicated the potential relevance of PTSD interventions in the treatment of CPTSD (16). Despite this, there are also differences in the mediating processes involved in CPTSD, PTSD and BPD. For example, this review identified one article which found that disconnection and impaired autonomy schemas acted as mediators in the association of complex trauma and CPTSD, whereas similar research examining BPD identified schemas of vulnerability to harm and defectiveness as mediators involved in the development of BPD (88). Additionally, another article in this review demonstrated that dissociative, emotional developmental and social developmental processed mediated complex trauma and CPTSD independently of BPD (43), thus indicating separate mediating pathways for CPTSD and BPD. This fits with previous research which has differentiated CPTSD and BPD as distinct constructs (25, 26). Further research will be required to determine which combinations of overlapping mediating processes interact to differentiate the development of each clinical presentation as either CPTSD, PTSD, or BPD.

More broadly, the findings of this review complement previous systematic reviews centred on CPTSD (11, 15, 16) by taking steps towards better understanding mediators of the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD.

Limitations of articles

All but two studies in this review were assessed as having moderate or weak methodological quality, largely employing cross-sectional designs which prevent casual inferences (89). This contributes to bias across studies; without longitudinal or experimental evidence, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the exact roles of each mediator in the pathways linking complex trauma and CPTSD. Furthermore, the lack of temporal precedence accounted for by cross-sectional designs can lead to difficulty in disambiguating the temporality of the mediation relationship (90). Despite this, atemporal statistical mediation effects were nevertheless demonstrated, thus indicating how the identified mediating factors explained the variance in CPTSD outcomes when accounting for the shared relationship between complex trauma, CPTSD and each mediating factor (90). In order to address this limitation, longitudinal research must be conducted in order to examine the replicability of the current findings within a temporal design, and to better understand the temporality of the established atemporal mediation relationships (90). This is particularly important when considering the conceptual overlap between several identified mediators (e.g. ‘Relationship to Self’) and CPTSD outcome domains (e.g. ‘Negative Self-Concept’), which poses difficulties in differentiating the identified mediating processes from CPTSD outcome domains.

One possible approach to understanding this at a conceptual level is through considering the difference between mediating processes and CPTSD outcome domains. For example, the ‘Relationship to Self’ category of mediators reflects a variety of maladaptive underlying processes (e.g. alterations in self-perception, self-judgement, early maladaptive schema) and protective processes (e.g. self-compassion, self-kindness) that were operationalised differently to how CPTSD outcomes were operationalised (i.e. through CPTSD-specific assessment measures) and interact to culminate in the outcome (i.e. a negative self-percept). This fits with previous research indicating the relevance of the identified mediating processes in the development of CPTSD (21; 18; 20; 17; 4, 19). As many studies utilised formal mediation analyses, this indicates that a mediation effect of these mediating variables influenced outcome variables at a statistical level (22). Despite this, as the studies included in this review operationalised mediator and outcome variables in cross-sectional study designs, it is difficult to disambiguate mediator and outcome variables beyond a conceptual level (91).

In order to more confidently conclude that the identified mediator variables are indeed mediators, as opposed to outcome variables, further research utilising longitudinal designs which can assess the temporality of relationships between variables will help to ensure the mediator and outcome variables are sufficiently disambiguated (92). Future research should involve examining the role of mediating factors in the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD over at least two timepoints in order to establish the temporality and mechanistic nature of these mediation relationships.

Additionally, these studies relied on retrospective self-reports of complex trauma exposure; although the validity of these accounts is not in question, it is possible that the extent of trauma is under-reported (93). Furthermore, there was a lack of consideration given to the duration of complex trauma experiences. Despite this, some studies did account for the potential impact of confounding factors (e.g. gender, age) and showed that mediation effects were maintained in models which incorporated confounding factors. Longitudinal research is required to better understand the specific ways in which the mediators identified by studies in this review interact with complex trauma exposure in the development of CPTSD over time.

Additionally, although systemic factors relating to disclosure and acknowledgement of trauma within an individual’s system were identified, no studies examined the potential mediating role of wider systemic factors (e.g. community factors, poverty, discrimination). Furthermore, although studies were conducted across a wide range of cultural and geographical settings, only two studies collected data on the racial backgrounds of participants and five studies collected data on geographical background. No studies collected data on participant sexuality. It will be important for researchers to pay closer attention to variables such as race and sexuality due to minority stress and how experiences of minoritisation may moderate the relationship between complex trauma and CPTSD (94, 95). Examination of potential neurobiological and genetic mediators will also be of importance.

Lastly, the mediators identified through this review were tested across a range of studies. Future research should aim to assess the significance of these mediators in a single study, in order to examine the relative effects of each mediator along with potential interaction and cumulative effects. As the identified mediators are relevant to a range of clinical presentations, including PTSD and BPD, future research should also aim to identify which patterns of mediators may contribute to a particular outcome over another.

Clinical implications

The identification of these mediators helps in better understanding possible underlying pathways and mechanisms involved in the development and prevention of CPTSD. Currently, in the United Kingdom, there is no ‘gold standard’ treatment recommendation for CPTSD (14). Although dissociation, emotion dysregulation, interpersonal difficulties and negative self-perception in CPTSD are noted as ‘barriers to engaging with trauma-focused therapies’ by NICE (14), these are not in and of themselves identified by NICE as targets for preventative action or therapeutic intervention for the alleviation of CPTSD itself. The findings of this review indicate that, beyond acting as barriers to engaging with trauma-focused therapies, it is possible these aspects of CPTSD could play an important mechanistic role in linking complex trauma and CPTSD and may be important targets for clinical intervention. However, further clinical research is required to examine whether targeting the mediators identified in this review could act as a mechanism for change and healing from complex trauma.

Conclusions

There are many factors which mediate the relationship between complex trauma exposure in childhood and CPTSD. These mediators can be organised as processes relating to: 1) dissociation, 2) a disturbed relationship to self, 3) emotional development, 4) social development, and 5) systemic and contextual factors. Despite this, the methodological limitations of the studies which identified these mediating processes lead to difficulty in understanding the extent to which awareness of these mediating factors should inform prevention strategies, clinical formulation and intervention for CPTSD. This is particularly true when considering that these factors are not necessarily specific to CPTSD. Future longitudinal research is required to gain a deeper understanding of the possible developmental role of each mediating factor in the aetiology of CPTSD, and in examining the clinical utility of incorporating these mediators as targets for intervention in the treatment of CPTSD.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. VS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Fundings

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Professor Eva Loth was supported by funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint UNdertaking under grant agreement No.115300 (for EU-AIMS) and No. 777394 (for AIMS-2-TRIALS), which receives support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme and EFPIA and Autism Speaks, Autistica, SFARI, the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (CANDY) under grant agreement No. 847818, and the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative )SFARI) under Award ID 640710.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Graham A, Fisher P, Pfeifer J. What sleeping babies hear: A functional MRI study of interparental conflict and infants’ emotion processing. psychol Sci. (2013) 24:782–9. doi: 10.1177/0956797612458803

2. Cusack R, Ball G, Smyser C, Dehaene-Lambertz G. A neural window on the emergence of cognition. Ann New York Acad Sci. (2016) 1369:7–23. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13036

3. Powers A, Fani N, Cross D, Ressler K, Bradely B. Childhood trauma, PTSD, and psychosis: Findings from a highly traumatised, minority sample. Child Abuse Negl. (2016) 58:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.06.015

4. Herman J. Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Traumatic Stress. (1992) 5:377–91. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050305

5. Kliethermes M, Schact M, Drewery K. Complex trauma. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clinics North America 23. (2014) 2:338–261. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.12.009

6. World Health Organisation. ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision) (2019). Available online at: https://icd.who.int/.

7. Cloitre M, Hyland P, Bisson J, Brewin C, Roberts N, Karatzias T, et al. ICD-11 posttraumtic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: A population-based study. J Traumatic Stress. (2019) 32:833–42. doi: 10.1002/jts.22454

8. Hyland P, Vallieres F, Cloitre M, Ben-Ezra M, Karatzias T, Olff M, et al. Trauma, PTSD, and complex PTSD in the Republic of Ireland: Prevalence, service use, comorbidity, and risk factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2020) 56:649–58. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01912-x

9. Ben-Ezra M, Karatzias T, Hyland P, Brewin C, Cloitre M, Bisson J, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD) as per ICD-11 proposals: A population study in Israel. Depression Anxiety 35 (2018) 3:264–74. doi: 10.1002/da.22723

10. Lewis C, Lewis K, Roberts A, Edwards B, Evison C, John A, et al. Trauma exposure and co-occurring ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder in adults with lived experience of psychiatric disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scandinavia. (2022) 146:258–71. doi: 10.1111/acps.13467

11. De Silva U, Glover N, Katona C. Prevalence of complex post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry Open. (2021) 7:E194. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.1013

12. Dorahy M, Corry M, Shannon M, Webb K, McDermott B, Ryan M, et al. Complex trauma and intimate relationships: The impact of shame, guilt and dissociation. J Affect Disord. (2013) 147:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.010

13. Van Dijke A, Ford J, Frank L, Van der Hart O. Association of childhood complex trauma and dissociation with complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adulthood. J Trauma Dissociation. (2015) 16:428–41. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2015.1016253

14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Post-traumatic stress disorder [NICE Guideline No. NG116] (2018). Available online at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/chapter/Recommendations#care-for-people-with-ptsd-and-complex-needs.

15. Brewin C, Cloitre M, Hyland P, Shevlin M, Maercker A, Bryant R, et al. A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 58:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.001

16. Karatzias T, Murphy P, Cloitre M, Bisson J, Roberts N, Shevlin M, et al. Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. psychol Med. (2019) 49:1761–75. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000436

17. Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, et al. Complex trauma. Psychiatr annals 35 (2005) 5:390–8. Available at: https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//complex_trauma_in_children_and_adolescents.pdf.

18. Spinazzola J, van der Kolk B, Ford J. When nowhere is safe: Interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity as antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder and developmental trauma disorder. J Traumatic Stress 31 (2018) 5:631–42. doi: 10.1002/jts.22320

19. Bailey H, Moran G, Pederson D. Childhood maltreatment, complex trauma symptoms, and unresolved attachment in an at-risk sample of adolescent mothers. Attachment Hum Dev. (2007) 9:139–61. doi: 10.1080/14616730701349721

20. Haskell L, Randall M. Disrupted attachments: A social context complex trauma framework and the lives of aboriginal peoples in Canada. J Aboriginal Health. (2009) 5:48–99. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1569034.

21. Daniels A, Bryan J. Resilience despite complex trauma: Family environment and family cohesion as protective factors. Family J. (2021) 29:336–45. doi: 10.1177/10664807211000719

22. MacKinnon D, Fairchild A. Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr Dir psychol Sci. (2009) 18:16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x

23. Tryon W. Mediators and mechanisms. Clin psychol Sci. (2018) 6:619–28. doi: 10.1177/2167702618765791

24. Page M, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Hoffman T, Mulrow C, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br Med J (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

25. Cloitre M, Garvert D, Weiss B, Carlson E, Bryant R. Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2014) 5:25097. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25097

26. Jowett S, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Albert I. Differentiating symptom profiles of ICD-11 PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis in a multiply traumatised sample. Pers Disorders: Theory Research Treat. (2020) 11:36–45. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2021.1934936

27. Paez A. Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. J Evidence-Based Medicine 10 (2017) 3:233–40. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12266

28. Richardson W, Wilson W, Nishikawa J, Hayward R. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. Am Coll Physicians J Club (1995) 123, 3:12–3.

29. Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles C, Hagen N, Biondo P, Cummings G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A compassion of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. (2012) 18:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

30. Popay K, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. (2006). doi: 10.13140/2.1.1018.4643

31. Dyer K, Dorahy M, Shannon M, Corry M. Trauma typology as a risk factor for aggression and self-harm in a complex PTSD population: The mediating role of alterations in self-perception. J Trauma Dissociation. (2013) 14:56–68. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2012.710184

32. Guo T, Huang L, Hall D, Jiao C, Chen ST, Yu Q, et al. The relationship between childhood adversities and complex posttraumatic stress symptoms: A multiple mediation model. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2021) 12:1936921. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1936921

33. Haselgruber A, Knefel M, Solva K, Lueger-Schuster B. Foster children’s complex psychopathology in the context of cumulative childhood trauma: The interplay of ICD-11 complex PTSD, dissociation, depression, and emotion regulation. J Affect Disord. (2021) 282:372–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.116

34. Jowett S, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Hyland P. Psychological trauma at different developmental stages and ICD-11 CPTSD: The role of dissociation. J Trauma Dissociation 23 (2022) 1:52–67. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2021.1934936

35. Kampling H, Kruse J, Lampe A, Nolte T, Hettich N, Brahler E, et al. Epistemic trust and personality functioning mediate the association between adverse childhood experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in adulthood. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 10:919191. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.919191

36. Knefel M, Lueger-Schuster B, Karatzias T, Shevlin M, Hyland P. From child maltreatment to ICD-11 complex post-traumatic stress symptoms: The role of emotion regulation and re-victimisatoin. J Clin Psychology 75. (2019) 3:392–403. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22655

37. Krammer S, Kleim B, Simmen-Janevska K, Maercker A. Childhood trauma and complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older adults: A study of direct effects and social-interpersonal factors as potential mediators. J Trauma Dissociation. (2016) 17:593–607. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2014.991861

38. Kvedaraite M, Gelezelyte O, Karatzias T, Roberts N, Kazlauskas E. Mediating role of avoidance of trauma disclosure and social disapprove in ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder: Cross-sectional study in a Lithuanian clinical sample. Br J Psychiatry Open. (2021) 7:e217. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.1055

39. Maercker A, Bernays F, Rohner S, Thoma M. A cascade model of complex posttraumatic stress disorder centred on childhood trauma and maltreatment, attachment, and socio-interpersonal factors. J Traumatic Stress. (2021) 35:446–60. doi: 10.1002/jts.22756

40. McQuillan K, Hyland P, Vallieres F. Prevalence, correlates, and the mitigation of ICD-11 CPTSD among homeless adults: The role of self-compassion. Child Abuse Negl (2022) 127:105569. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105569

41. Sandberg D, Refrea V. Adult attachment as a mediator of the link between interpersonal trauma and International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder symptoms among college men and women. J Interpersonal Violence. (2022) 0:1–21. doi: 10.1177/08862605211072168

42. Solva K, Haselgruber A, Lueger-Schuster B. The relationship between cumulative traumatic experiences and ICD-11 post-traumatic symptoms in children and adolescents in foster care: The mediating effect of sense of coherence. Child Abuse Negl. (2020) 101:104388. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104388

43. Van Dijke A, Ford J. Affect dysregulation, psychoform dissociation, and adult relational fears mediate the relationship between complex posttraumatic stress disorder independent of the symptoms of borderline personality disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2018) 9:1400878. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1400878/

44. Vasilopoulou E, Karatzias T, Hyland P, Wallace H, Guzman A. The mediating role of early maladaptive schemas in the relationship between childhood traumatic events and complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older adults (>64 years). Journal of Loss and Trauma (2020) 25(2):141–58. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2019.1661598

45. Cloitre M, Shevlin M, Brewin C, Bisson J, Roberts N, Maercker A, et al. The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 138 (2018) 6:536–46. doi: 10.1111/acps.12956

46. Van der Kolk B, Brown P, Van der Hart O. Pierre Janet on post-traumatic stress. J Traumatic Stress. (1989) 2:365–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00974596

47. Gross J. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. psychol Inq. (2015) 26:1–26. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

48. Gratz K, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess (2004) 26:41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

50. Palihawadana V, Broadbear J, Rao S. Reviewing the clinical significance of ‘fear of abandonment’ in borderline personality disorder. Australas Psychiatry (2019) 27, 1:60–3. doi: 10.1177/1039856218810154

51. Bernstein D, Stein J, Newcomb M, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl (2003) 272:169–90. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00531-0

52. Nijenhuis E, van der Hart O, Kruger K. The psychometric characteristics of the traumatic experiences checklist (TEC): First findings among psychiatric outpatients. Clin Psychol Psychother (2002) 93:200–10. doi: 10.1002/cpp.332

53. Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalised self-efficacy scale. Measures Health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal control beliefs (1995), 35–7.

54. Fraley R, Waller N, Brennan K. Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire-Revised. APA Psych Tests (2000). doi: 10.1037/t03763-000

55. Maercker A, Muller J. Social acknowledgement as a victim or survivor: A scale to measure a recovery factor of PTSD. J Traumatic Stress (2004) 17:345–51. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000038484.15488.3d

56. Fydrich T, Gert S, Tydecks S, Elmar B. Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU): Standardisation of short form (K-14). Z fur Medizinische Psychol (2009) 18, 1:43–8.

57. Ford J, Kidd P. Early childhood trauma and disorders of extreme stress as predictors of treatment outcome with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Traumatic Stress (1998) 114:743–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1024497400891

58. Bernstein E, Putnam F. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nervous Ment Dis (1986) 17412:727–35.

59. Vorst H, Bermond B. Validity and reliability of the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire. Pers Individ Dif (2001) 303:413–34. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00033-7

60. Weaver T, Clum G. Early family environments and traumatic experiences associated with borderline personality disorder. J Consulting Clin Psychology 61 (1993) 6:1068–75. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.6.1068

61. Griffin D, Bartholomew K. Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol (1994) 67, 3:430–45. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430

62. Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, Hamby S. A revised inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse Negl (2015) 48:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011

63. Raes F, Pommier E, Neff K, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother (2011) 183:25–255. doi: 10.1002/cpp/702

64. Grob A, Smolenski C. FEEL-KJ. Fragebogen zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation bei Kindern un Jugendlichen (2009).

65. Briere J, Elliott D, Harris K, Cotman A. Trauma symptom inventory: Psychometrics and association with childhood and adult victimisation in clinical samples. J Interpersonal Violence (1995) 10, 4:387–401. doi: 10.1177/088626095010004001

66. Müller J, Maercker A. Disclosure und wahrgenommene gesellschaftliche Wertschätzung als Opfer als Prädiktoren von PTB bei Kriminalitätsopfern [Disclosure and perceived social acknowledgement as victim as PTSD predictors in crime victims]. Z für Klinische Psychol und Psychotherapie: Forschung und Praxis (2006) 35(1):49–58. doi: 10.1026/1616-3443.35.1.49

67. Weathers F, Blake D, Schnurr P, Kaloupek D, Marx B, Keane T. The life events checklist for DSM-5 (2013). Available at: www.ptsd.va.gov.

69. Foa E. Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems (1995).

70. Pelcovitz D, van der Kolk B, Roth S, Mandel F, Kaplan S, Resick P. Development of a criteria set and a structured interview of disorders of extreme stress (SIDES). J Traumatic Stress (1997) 10, 1:3–16. doi: 1-.1002/jts.2490100103

71. Gutierrez P, Osman A, Barrios F, Kopper B. Development and initial validation of the self-harm behaviour questionnaire. J Pers Assess (2001) 77, 3:475–90. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08

72. Schafer I, Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C. ACE-D. Deutsche version des adverse childhood experiences questionnaire, 11-5. Diagnostische Verfahren der Sexualwissenscharft (2014).

73. Ehrenthal J, Dinger U, Horsch L, Komo-Lang M. The OPD Structure Questionnaire (OPD-SQ): First results on reliability and validity. Pscyhotherapie Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychol. (2012) 62:25–32. doi: 10.1055/s-0031.01295481

74. Bernstein E, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report-Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation (1998).

75. Boyle M. Power in the power threat meaning framework. J Constructivist Psychol. (2022) 35:27–40. doi: 10.1080/10720537.2020.1773357

76. Van der Kolk B, Fisler R. Dissociation and the fragmentary nature of traumatic memories: Overview and exploratory study. J Traumatic Stress. (1995) 8:505–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02102887

77. Reinders A, Nijenhuis E, Paans A, Korf J, Willemsen A, Boer J. One brain, two selves. NeuroImage. (2003) 20:2119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.021

78. Lieberman A. Traumatic stress and quality of attachment: Reality and internalisation in disorders of infant mental health. Infant Ment Health J. (2004) 25:336–51. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20009

79. Finkelhor D. The trauma of child sexual abuse. J Interpersonal Violence 2 (1987) 4:347–445. doi: 10.1177/088626058700200402

80. Van Reems L, Fischer T, Zwirs B. Social information processing mechanisms and victimisation: A literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2014) 17:3–25. doi: 10.1177/152483014557286

81. Ebbert A, Infurna F, Luthar S, Lemery-Chalfant K, Corbin W. Examining the link between emotional childhood abuse and social relationships in midlife: The moderating role of the oxytocin receptor gene. Child Abuse Negl. (2019) 98:104151. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104151

82. Hudson A, De Coster L, Spoormans H, Verbeke S, van der Jeught K, Brass M, et al. Childhood abuse and adult sociocognitive skills: Distinguishing between self and other following early trauma. J Interpersonal Violence. (2020) 36:23–4. doi: 10.1177/0886260520906190

83. Bertie L, Johnston K, Lill S. Parental emotion socialisation of young children and the mediating role of emotion regulation. Aust J Psychol. (2021) 73:293–305. doi: 10.1080/00049530.2021.1884001

84. Otis C, Marchand A, Courtois F. Peritraumatic dissociation as a mediator of peritraumatic distress and PTSD: A retrospective, cross-sectional study. J Trauma Dissociation. (2012) 13:469–77. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

85. Benoit M, Bouthillier D, Moss E, Rousseau C, Brunet A. Emotion regulation strategies as mediators of the association between level of attachment security and PTSD symptoms following trauma in adulthood. Anxiety Stress Coping (2010) 23(1):101–18. doi: 10.1080/106158002638279

86. Erkoreka L, Zamalloa I, Rodriguez S, Munoz P, Mendizabal I, Zamalloa I, et al. Attachment anxiety as a mediator of the relationship between childhood trauma and personally dysfunction in borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2022) 29:501–11. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2640

87. Dalgleish T, Black M, Johnston D, Bevan A. Transdiagnostic approaches to mental health problems: Current status and future directions. J Consulting Clin Psychol. (2020) 88:179–95. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000482

88. Khosravi M. Child maltreatment-related dissociation and its core mediation schemas in patients with borderline personality disorder. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:405. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02797-5

89. Van der Stede W. A manipulationist view of causality in cross-sectional survey research. Accounting Organisations Society 39 (2014) 7:567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2013.12.001

90. Winer S, Cervone D, Bryant J, McKinney C, Liu R, Nadorff M. Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: Atemporal associations do not imply causation. J Clin Psychol (2016) 729:947–55. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22298

91. Fiedler K, Schott M, Meiser T. What mediation analysis can (not) do. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2011) 47:1231–6. doi: 10.1177/088626058700200402

92. O’Laughlin K, Martin M, Ferrer E. Cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal mediation processes. Multivariate Behav Res. (2018) 53:375–402. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1454822

93. Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45 (2004) 2:260–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x

94. Meyer I. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. (1995) 36:38–56. doi: 10.2307/2137286

95. Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2015) 10:e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

Appendix

Keywords: complex trauma, CPTSD, mediator, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD), systematic review, mediation

Citation: Harris J, Loth E and Sethna V (2024) Tracing the paths: a systematic review of mediators of complex trauma and complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychiatry 15:1331256. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1331256

Received: 31 October 2023; Accepted: 20 February 2024;

Published: 06 March 2024.

Edited by:

Ravi Philip Rajkumar, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), IndiaReviewed by:

Antje Bühler, Military Hospital Berlin, GermanyOmneya Ibrahim, Suez Canal University, Egypt

Copyright © 2024 Harris, Loth and Sethna. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vaheshta Sethna, dmFoZXNodGEuc2V0aG5hQGtjbC5hYy51aw==

Joseph Harris

Joseph Harris Eva Loth

Eva Loth Vaheshta Sethna

Vaheshta Sethna