- 1General Adult Psychiatry, Gloucestershire Health and Care NHS Foundation Trust, Gloucester, United Kingdom

- 2Psychology Faculty, School of Psychology and Educational Sciences, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University, Iasi, Romania

- 3General Adult Psychiatry, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- 4Later Life, Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust, North Somerset, United Kingdom

- 5Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 6Psychology Department, School of Natural and Social Sciences, University of Gloucestershire, Gloucester, United Kingdom

Background: The relationship between dissociation and recovery from psychosis is a new topic, which could attract the interest of the researchers in the field of dissociation due to its relevance to their daily clinical practice. This review brings together a diversity of international research and theoretical views on the phenomenology of dissociation, psychosis and recovery and provides a synthesis by narrative and tabulation of the existing knowledge related to these concepts.

Aims: The objective was to make a synthesis by narrative and tabulation about what is known on the topic.

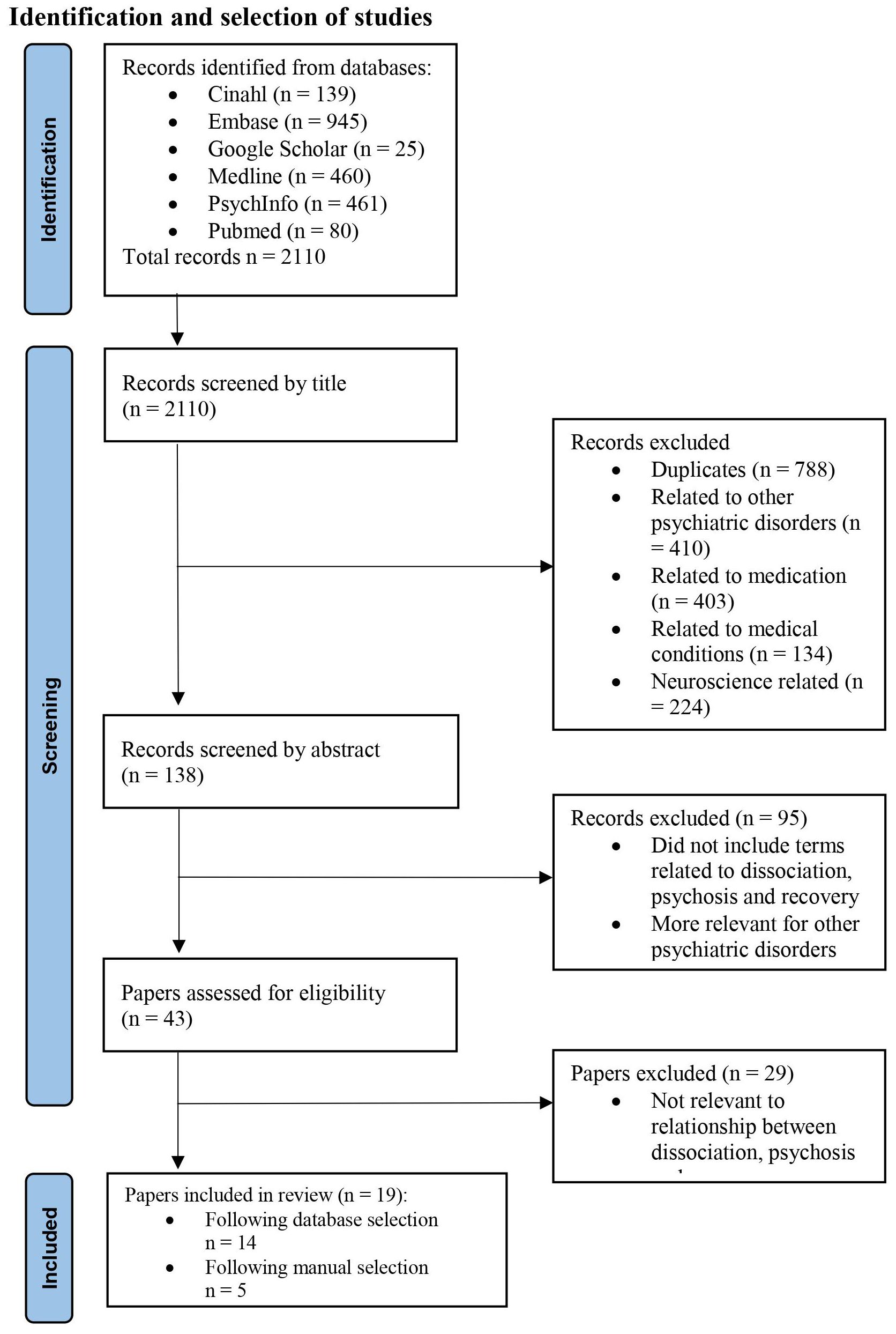

Methods: The systematic search was conducted according to the PRISMA-statement in the databases Medline, PsycInfo, PubMed and Google Scholar. 2110 articles were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed in the methods, and 19 records were included in the review.

Outcomes: None of the included publications put together, in the same conceptualisation or hypothesis, dissociation and the recovery from an episode of psychosis, therefore this matter remains unstudied at this time.

Conclusion: The process of reviewing the existing scientific literature in the field of dissociation and recovery from psychosis has been very useful for charting the direction that future research will take.

1 Introduction

The NHS is going through a transformation process as it is moving to a more inclusive, flexible model of care, in which patients get properly joined-up care at the right time in the optimal care setting. The focus will be on prevention, inequalities reduction, and on responsiveness to all those who use and fund the health service. As part of the new model, there is a strong drive to invest in the transformation of dedicated community mental health rehabilitation functions (1). The concept of recovery is at the core of this transformation plan, associated with that of severe mental illness. This means that the model will need to be more differentiated in its support offer to individuals. Improving access to psychological therapies for those with severe mental health problems is a top priority on the transformation agenda (2).

The transformation process and the reshaping of the rehabilitation community services has to be founded on robust and up to date evidence-based data and research. This is the right time for new psychological interventions, more person tailored and more innovative, focusing on different concepts such as ‘trauma’, ‘dissociation’ and ‘recovery’, to be created.

For about a century, dissociative disorders and dissociative symptoms have been associated with trauma and traumatic experiences. There is a vast body of literature demonstrating the relationship between trauma and dissociative experiences, in longitudinal and prospective studies (3, 4). The meaning of dissociation has been a topic for scientific debate for a very long time and although there continue to be differences in opinion among clinicians and researchers, one aspect has been unanimously agreed upon; namely the fact that dissociation involves the loss of the ability of the mind to integrate some of its superior functions (4).

Whereas there is extensive scientific literature on the relationship between dissociation and psychosis (5–7) there is little if any on the topic of dissociative mechanisms and the process of recovery from psychotic episodes. Research in the field of recovery is difficult to undertake, but has included publications in the form of outcome studies, theoretical publications, meta-analyses, book chapters and conference presentations. The authors believed that the process of reviewing the existing scientific literature in the field of dissociation and recovery from psychosis may be useful to understand the current state of knowledge and for charting the direction of future research.

2 Concepts

2.1 Dissociation

Dissociation is “the fragmentation of the usual continuity of subjective experience”;8 “disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of conscience, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control and behaviour” (8) “partial or total loss of the normal integration between the memory of the past, identity awareness and body movements control” (9). This idea derived from the concept of “disintegration” of the integrative function, introduced by Pierre Janet (1859-1947). This would result in a process of fragmentation at different mental levels, from consciousness to the personality unity itself (10). As opposed to Freud’s theory which defined dissociation as a defensive mechanism, Janet associated it with the loss of the connexion between normally integrated and overlapped mental functions, due to a “structural collapse” caused by traumatic experiences (10).

2.2 Psychosis

“The term “psychosis” lies at the heart of modern psychiatry” (11). DSM (8) and ICD-10 (9) describe specific diagnostic criteria for different psychotic conditions. Sadock and colleagues define the concept of psychosis as a group of mental illnesses where the loss of reality testing and the boundaries of the self are the main characteristics (12). Schizophrenia is often referred to in the specialist literature as representative for the psychosis group. It is a serious mental illness where the misinterpretation of stimuli from the external environment influences the information processing. As a result, a series of abnormal phenomena will occur in the form of positive symptoms (delusions and hallucinations), negative symptoms (apathy, anhedonia, dull affect, and loss of social cohesion), and cognitive ones.

Although distinctive symptoms for schizophrenia and dissociative disorders are listed by both ICD-10 and DSM-5, studies have shown an overlap between psychotic symptoms (for example, auditory hallucinations) and dissociation manifestations (13, 14). The causal relationship between dissociation and psychosis remains unexplored (3). Cernis and colleagues are of the view that this may be due to a possible lack of clarity about the role of dissociation in mental health (15).

2.3 Recovery

There are different points view of recovery but in this paper, the definition we used is the one coined by Anthony (16), who defined recovery as “a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by the illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness”. For this review, we aimed to identify articles that defined personal recovery.

3 Aim of the literature review

The aim of this review is to conduct an evaluation of the literature on recovery from psychosis and dissociation, using broader inclusion criteria thereby providing a synthesis by narrative and tabulation about what is known on the topic.

4 Methods

4.1 Search strategy

We limited the search to papers in the English language as we did not have access to volunteer or paid interpreters. We restricted the search to papers referring to population of any age within the interval 18-65. Medline, PsycInfo, PubMed databases were systematically searched using strings for dissociation, psychosis and recovery concepts: (dissociat* OR compartmentali* OR detach* OR absorption OR depersonalisation OR derealisation OR amnesia* OR “coping mechanism*” OR fragment*) AND (psychosis OR psychotic OR hallucinat* OR delusion* OR “positive symptom*” OR “negative symptom*” OR schizophreni* OR “thought disorder*” OR schizoaffective) AND (recover* OR outcome* OR recuperat* OR rehabilitat* OR improve* OR hope*). Google Scholar database was also searched using the following search strategy: Articles with any of these words in the article (Dissociate/compartmentali/psychosis/schizophrenia/psychot/hallucinate/recover/rehabilitat/outcome) or with these words in the title (psychosis/dissociation/therapeutic). 14 studies were identified using this method.

Beside the database search, a hand-search of references and citations from eligible articles was also performed in order to identify additional studies. Five studies were included using this method.

Articles were assessed for eligibility based on screening of titles, abstracts and full texts and only retained for review with consensus agreement from four reviewers. The search and screening procedure are presented in Figure 1.

4.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

1. Publications on dissociation and psychosis and recovery, including terms (utilised in the search strategy) such as:

• Dissociation – compartmentalisation, detachment, absorption, depersonalisation, derealisation, amnesia, copying mechanism, fragmentation.

• Psychosis - hallucinations, delusions, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, schizophrenia, thought disorder, schizoaffective, psychotic, delusional.

• Recovery – outcome, recuperation, rehabilitation, improvement, hopefulness.

2. Articles published in English;

3. No date or age limits;

4. Studies on clinical and/or non-clinical population.

Exclusion criteria:

1. Articles about dissociation and psychiatric conditions other than psychosis;

2. Articles about dissociation and medical conditions;

3. Studies from the neuroscience domain.

4.3 Identification and selection of studies

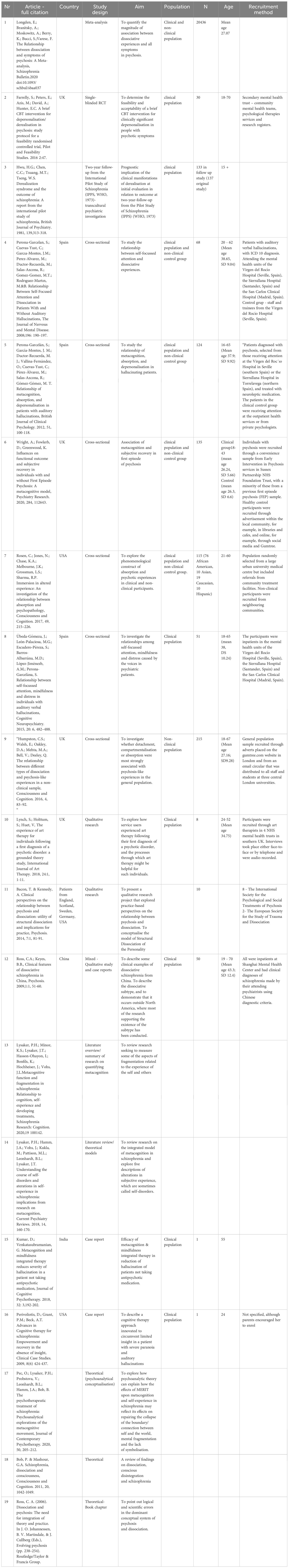

Following the selection process, 19 articles were included in this review. They are described in Table 1.

4.4 Quality assessment

Studies were reviewed by four authors individually. Disagreements related to the eligibility of the studies were resolved by finding additional information and through discussions between the authors. Due to the diverse designs of the studies and articles included, a narrative synthesis approach was employed in order to obtain a summary of the information and data encompassed by the selected literature.

4.5 Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by three authors and systematically checked for accuracy by the main author. Information extracted from the primary studies was recorded on a standardised form including general characteristics (authors, publication title, country, publication year), design, sample characteristics (age, clinical/non-clinical, recruitment method), measures used to assess dissociation, psychosis and other dimensions, who applied the instruments and the limitations of the studies.

5 Results

5.1 Study design

The design and the type of included studies and articles were diverse, including: a randomised controlled trial (17), a meta-analysis (7), a longitudinal study (18), seven cross-sectional studies (6, 19–24), two qualitative studies (5, 25), one mixed methods design (26), two literature reviews (27, 28), a case report (29), two articles summarising theoretical views (30, 31), and a book chapter (32).

The included studies and articles are described in Table 1, which has inevitably some incomplete sections as the information that would have populated the respective sections, was not reported in the publications included.

5.2 Definitions used in the included publications

There are different conceptualisations of the notions on which we focussed our review. We did not analyse them as they were not always reported in the included articles, therefore we thought appropriate to presented them as used in the studies that reported them.

We looked at how the papers defined the keywords included in the database search (dissociation, psychosis and recovery) and the associated terms (compartmentalisation, detachment, absorption, depersonalisation, derealisation, amnesia, copying mechanism, fragmentation, hallucinations, delusions, positive symptoms, negative symptoms, schizophrenia, thought disorder, schizoaffective, psychotic, delusional, outcome, recuperation, rehabilitation, improvement, hopefulness). Most commonly defined terms were schizophrenia, psychosis, dissociation, compartmentalisation, and absorption.

The term psychosis as a broader concept is used in three papers (5, 17, 25). Most of them use the notion of schizophrenia as representative for psychosis (18, 22, 24, 27, 28, 31, 32). None of the papers include definitions for terms related to recovery or rehabilitation. Five publications do not include any definitions of the concepts relevant to this paper (20, 21, 23, 30, 32).

The concept of dissociation was defined either as a general concept or by referring to specific dissociative mechanisms. Longden and colleagues refer to the DSM-5 definition of dissociation as ‘‘a disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control and behaviour’’ (7, 8). Humpston and colleagues look at which type of dissociation is most associated with psychosis-like experiences (6). They refer to the notions of “compartmentalisation-type dissociation which stems from the work of Pierre Janet [ … ] who originated the modern concept of dissociation as the compartmentalisation of normally integrated mental functions leading to the loss of conscious control or awareness of specific mental, physical or sensory processes” (33) and absorption “which relates to the ability to become immersed in thoughts and experiences’’ (6, 34).

Farelly and colleagues define psychosis as “a general term covering a range of psychiatric diagnoses such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder” (17) and dissociation “as a disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control and behaviour” (17), as per DSM-5 (8). Further, they offer definitions for detachment: “(it) concerns a person’s sense of separation from experience, including from their sense of self [ … ] or from the external world’’ and for compartmentalisation: “a disruption in normally integrated functions that is not accessible to conscious control and includes dissociation’’ (17).

Rosen and colleagues talk about the “ipseity of schizophrenia (the term refers to the nature of self in schizophrenia), involving two core components of disturbed basic sense of self: hyperreflexivity and diminished self-affection (22). Hyperreflexivity refers to the process by which events, sensations and cognitions that would normally be experienced as tacit [ … ] become explicit’’ and “diminished self-affection described the loss of attenuation of a normal sense of the self-existing as the subject [ … ] of consciousness” (22). They also define the concept of absorption, which “describes a state of immersion in (or capture by) mental imagery or perceptual stimuli and correlates vivid imagination or fantasy’’ (22).

Bacon and Kennedy differentiate between “psychosis-as-PTSD’’ and “psychosis-as-dissociation’’ (5). Focusing on the term relevant to this paper (dissociation), they further explain that in the case of ‘‘psychosis-as-dissociation’’ is ‘‘where psychotic symptoms represent interplay between deeply fragmented and incohesive ego-states, and the deterioration of the ego” (5).

Bob and Mashour refer to Eugen Bleuler’s definitions of schizophrenia: “in 1911 Eugen Bleuler introduced the term schizophrenia as a description of this mental illness [ … ], which replaced Kraepelin’s term dementia praecox’’ (31). For the term dissociation they mention several definitions, from Pierre Janet and Bleuler’s definition: “Janet used the term dissociation to denote a splitting of the psyche and analogously Bleuler [ … ] used the term dissociation as a synonym for splitting’’ to a more recent definition: “the recent definition of dissociation as a special form of consciousness in which events that would ordinarily be connected are divided from one another, leading to a disturbance or alteration in the normally integrative functions of identity, memory, consciousness” (31).

Lysaker and colleagues discuss the concept of schizophrenia from different perspectives: as defined by Kraepelin, Bleuler, Rosenbaum (“disconnection of images, affects and ideas and causes a breach in the unity of the self and threatens the many symbolic link characterising its integrating capacities and its reality testing”), from a psychoanalytic point of view, from an existential perspective with Laing’s focus on subjective experience of schizophrenia (“fundamental kind of alienation or a rent in his relation with his world [ … ] and a disruption of his relation with himself”), the phenomenological and ipseity model of self-experience in schizophrenia, the rehabilitation and recovery based models of disturbance in self-experience in schizophrenia, and the dialogical models of schizophrenia (27, 28).

Two articles refer to the definitions and diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR and the American Psychiatric Association for a dissociative subtype of schizophrenia (32, 35). Perivoliotis and colleagues define schizophrenia as a “chronic disorder associated with significant disability and poor quality of life” (24). Hwu and colleagues refer to Eugen Bleuler’s definition of schizophrenia “as a constellation of fundamental symptoms” (18). Lynch and colleagues mention that “there are different ways of conceptualising ‘psychosis’ or ‘psychotic experiences’ (25) which include hearing voices and having unusual beliefs’’ (36).

Perona-Garcelan and colleagues use terms such as dissociation, hallucinations, schizophrenia, absorption, depersonalisation, however they do not define them (20).

Detachment and absorption are two dissociative phenomena explored by some of the studies included in this review. Detachment refers to a mental process also sometimes termed depersonalisation/derealisation. These phenomena encompass the experience of detachment from self and environment where the self and the environment are experienced as unfamiliar or altered (37). DSM-5 describes depersonalisation/derealisation as a dissociative disorder per se and also as a symptom characterising other psychiatric conditions (8).

Other authors describe a more “normal” aspect of dissociation. Buttler introduces the idea of “normal” dissociation and describes absorption as representative for this type of dissociation (38). Absorption is very often referred to as “normal” or non-pathological dissociation (39). It represents the involuntary tendency to attention narrowing to the extension of ignoring the environment and implies a temporary suspension of the reflective consciousness (38).

5.3 Participants

14 studies of the 19 publications selected for this review, included population samples of different sizes (see Table 1), the total number of participants being 21.377. The study by Logden was substantially the largest (7). They were recruited from the adult population aged between 18 and 70, with two studies recruiting younger participants (18, 20). The majority of the studies recruited participants from the clinical population. Seven studies were developed on clinical popuations only (17, 18, 23–26, 29). One cross-sectional study included only a non-clinical population (6). Five studies selected their control groups from a non-clinical population (7, 19–22). One study does not report which population the participants were recruited from (5).

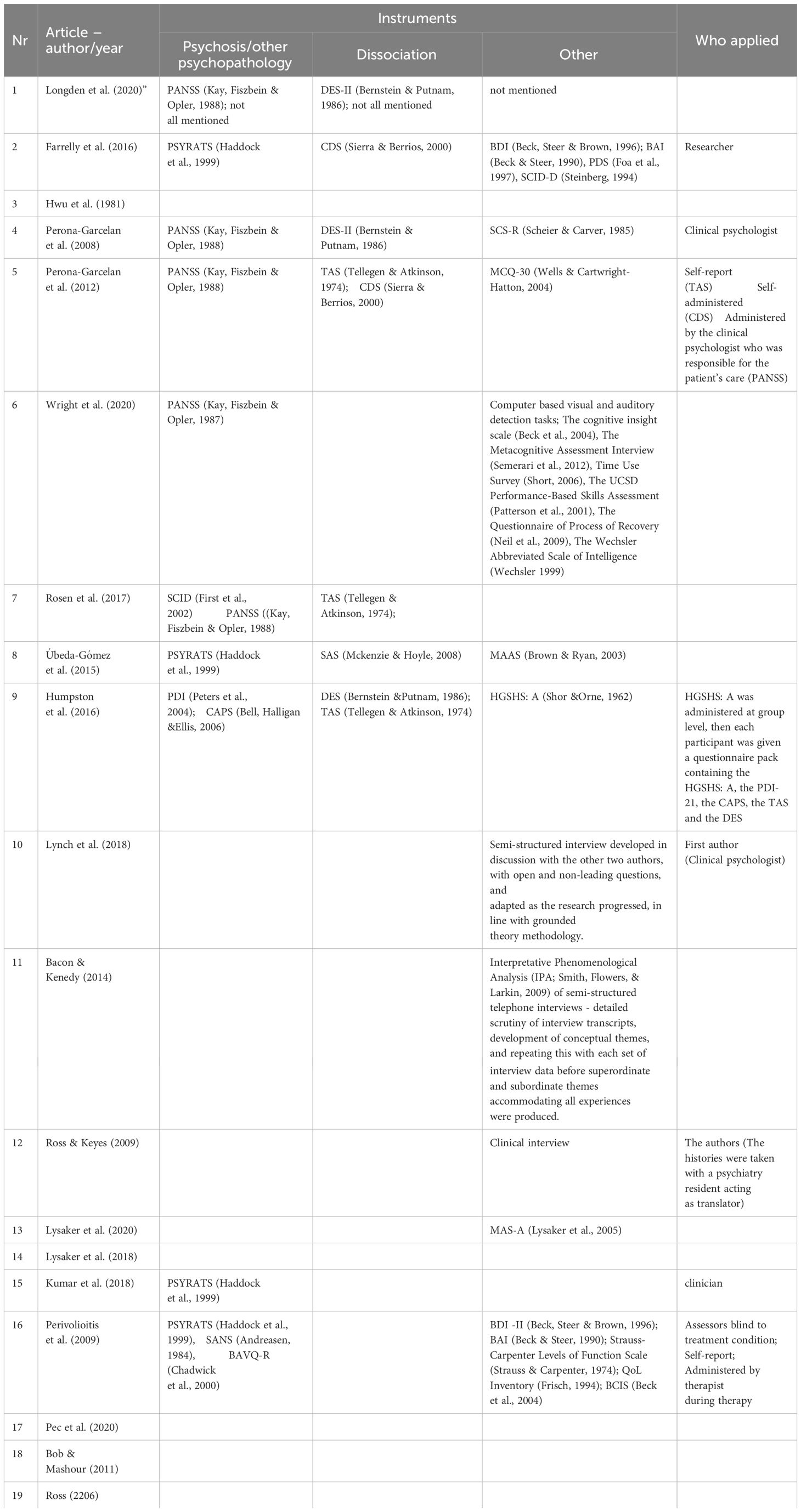

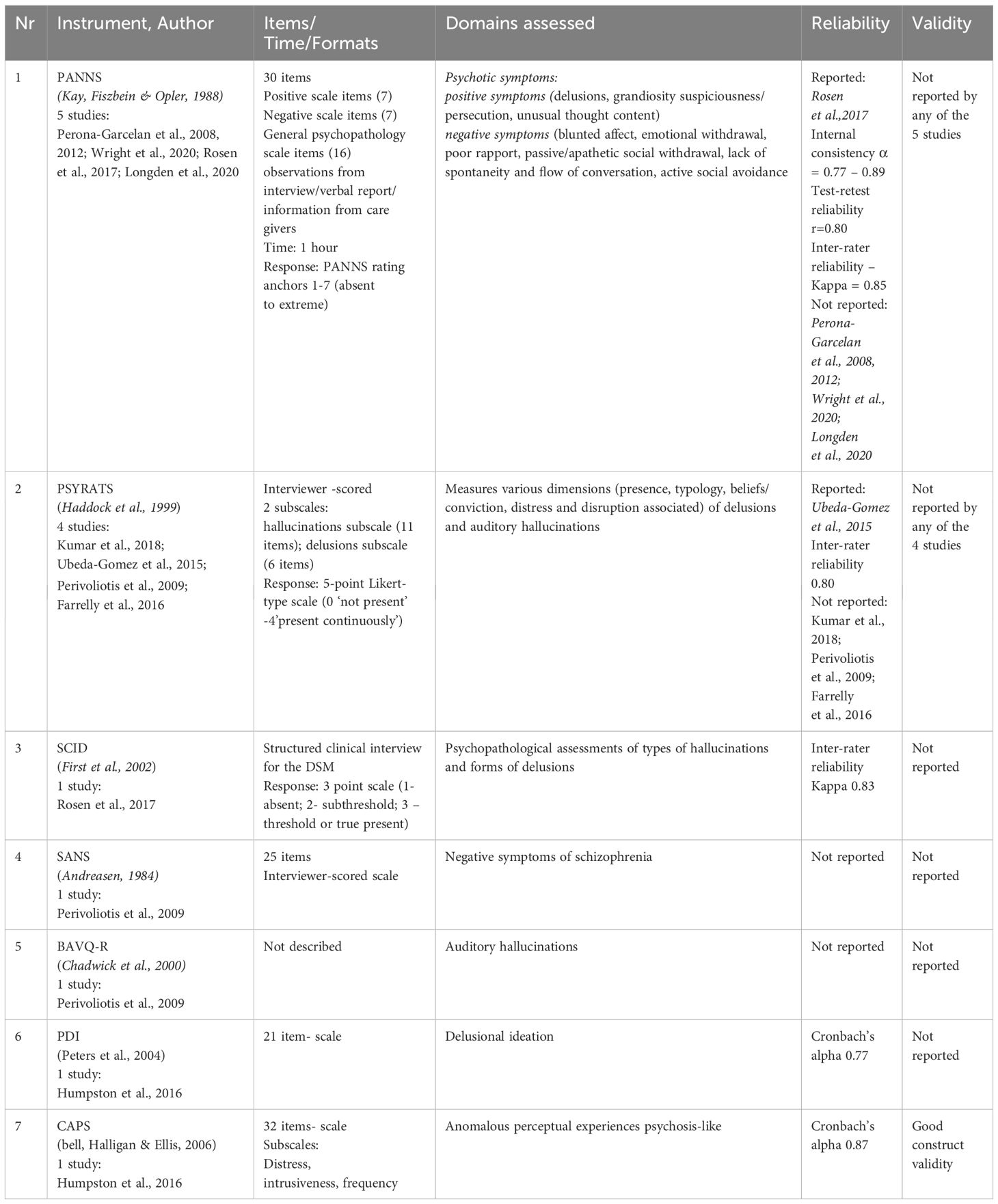

5.4 Assessment tools

The 19 studies included in our review encompass a wide variety of tools. Out of them, one appears in a third of the studies, namely the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (40). A total of 33 measuring instruments including clinical interviews were used (see Table 2), which we grouped into the following categories:

• Scales for the measurement of psychosis (see Table 3).

• Scales for the measurement of dissociative experiences (see Table 4).

• Other scales (see Table 5).

There is a huge variation in the degree of detail in which they were described by the authors of the articles included in this literature review, and also with regards to reporting aspects related to the reliability and validity of the instruments used.

6 Discussion

Studies that looked at the relationship between trauma and dissociation in people with psychosis demonstrate that patients with psychosis who have had traumatic experiences in childhood score higher on the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) than those who have not experienced traumas (26).

Classically but not always, dissociative experiences occur in response to psychological trauma. Watkins and Watkins referred to dissociation as an organising principle which allows people to adapt, thus moving the focus from a pathological perspective to a constructive potential and adaptive function of dissociation (41). Bowins expressed his view that dissociative manifestations can buffer disturbing emotional states, facilitating adaptive coping; they are employed by individuals to protect themselves against stress, therefore aiding recovery (42, 43). This shift in the way dissociation is now seen, and our clinical observations that people who are recovering from an episode of psychosis, are at the core of our initiative to carry out this overview of the existent literature looking at the usage of dissociation in the process of recovery from psychosis.

The review brings together a diversity of international research and theoretical views on the phenomenology of dissociation, psychosis and recovery. Due to the diverse designs of the studies and articles included, a narrative synthesis approach was more appropriate in order to try and understand the views on these three concepts and how they may be linked to each other. While none of them includes studies or views on the relationship between dissociation and recovery from psychosis, they do provide some perspectives and findings that could guide the discussion on this pioneering topic and inform and stimulate specific research on the matter.

The findings of this review (see Table 6) indicate that the prevalence of the derealisation syndrome is not different between the groups of participants diagnosed with schizophrenia and those without this diagnosis (18). An important finding showed that patients recovered from hallucinations had a significantly higher mean DES-II score than the nonclinical control group (t=11·130, p=0·009) and that the participants with psychotic disorder who had never had hallucinations, had a significantly higher score on the DES-II scale than the participants in the non-clinical control group (t=5·668, p=0·007) (19). Other findings were that compartmentalisation-type dissociation did not predict psychosis-like experiences and a post hoc cluster analysis indicated that detachment-type dissociation and absorption are largely distinct from psychosis-like experiences and do not reflect similar constructs (6).

These findings are consistent with the views that dissociation phenomena can spread on a continuum of distress and disability (7), ranging from nonpathological experiences to chronic and extremely disabling conditions (44).

7 Limitations

Table 6 summarises the limitations of the studies as reported by the authors.

One of the major limitations is the small number of publications included in the review and their very diverse nature. Because research in this field is difficult to undertake due to the difficulty to conceptualise dissociation and the overlapping of the phenomenological manifestations of dissociation and psychosis (35), we identified a very small number of publications that could be included in our review, despite the initial identification of a large number of publications in the world literature. None of them put together, in the same conceptualisation or hypothesis, dissociation and the recovery from an episode of psychosis, therefore this matter remains unstudied at this time. For the purpose of this review of the literature, we did not differentiate between the psychotic conditions because they are a large group of nosological entities. Although characterised by similar types of symptoms, psychotic conditions can differ in their manifestations, severity, response to treatment, prognosis and duration (45). This is an aspect that may be helpful to consider in a future research project.

We acknowledge the fact that our review of the literature only focussed on the relationship between dissociation and recovery from psychosis, and did not evaluate the factors that can influence the complex interaction between dissociation and psychosis, such as treatment, psychotherapy and history of trauma. The role of psychotherapeutic interventions in the recovery from psychosis is essential (46–48) but this was not evaluated during our survey. Another important factor is the treatment and response to treatment. There are instances where recovery can be difficult to achieve due to resistance to treatment. Resistance to drug therapy is reported in approximately 30–50% of patients with schizophrenia (49, 50). Panov (2022) (51) conducted a study that looked at the relationship between the degree of dissociation and resistance to therapy. The findings showed a high degree of dissociation in patients with resistant schizophrenia compared with those in remission. It has been demonstrated that those with a high degree of dissociation have a more severe course of illness (52). Consideration needs to be given also to the mechanism of action of antipsychotics as pharmacotherapy is crucial in the process of recovery from psychosis. An interesting hypothesis about the mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics is proposed by Kapur and Seeman (2001) (53) explaining the “atypical” antipsychotic effect of the second generation antipsychotics. According to that, the fast dissociation from the D2 receptor makes an antipsychotic more accommodating of physiological dopamine transmission, permitting an antipsychotic effect without major side effects. This will improve compliance with treatment and subsequently facilitate the alleviation of symptoms and the process of recovery (54). Trauma is another factor that mediates the relationship between dissociation and psychosis (55, 56) and would need to be addressed in order to facilitate recovery. An interesting finding was reported by Van der Linde et al. (2023) who conducted a study that investigated the role of dissociation related beliefs about memory in trauma-focussed treatment. The results showed that dissociation-related beliefs do not influence the outcome of trauma-focussed treatment (57), The authors of some of the included studies report limitations to their projects. These, we believe, are important sources of learning and they could inform further research and stimulate curiosity to explore whether dissociative mechanisms are used by people with psychosis when they recover from an episode of illness.

One of the main learning points is that there are fundamental differences in the conceptualisation of the notions explored and their assessment by different measures (7). There is no consistency in reporting dissociation scale scores in the papers included in this review and therefore a cross-sectional comparison of the outcomes was not possible. Although the articles included report studies conducted in different countries, the search strategy was limited to those published in English. Although the population samples used for these studies include a wide range of ages and sources, the potential influence exercised by the cultural factor onto the dissociative experiences suggests that the results communicated by the Western studies may not always fully translate to other cultural settings (6). The small sample size studies (19, 22) and the cross-sectional design (6, 19–24) limited the generalizability of findings and the possibility to extract causal relationships among the variables studied. Another factor that could have influenced the findings, could be the recruitment methodology: approached by clinicians based on diagnoses (17, 19–21, 23, 25, 26), advertisement within the local community (6, 21), random selection from an urban university medical centre and neighbouring communities (22); from research registers (17). Many factors such as participant nationality, profession, recruitment organisation may have influenced the findings and for this reason they cannot be considered representative (5).

8 Conclusion

Dissociation is a complex phenomenon involving different mechanisms that can modulate both the psychopathological processes underlying psychosis and recovery. The idea of integrative dissociation, suggested by Bacon and Kennedy (5), actually opens up the way to a new conceptualisation of dissociation, with potential impact on therapeutic intervention.

The process of reviewing the existing scientific literature in the field of dissociation and recovery from psychosis has been useful for charting the direction that future research projects will take. The putative association which we have raised, between dissociation and recovery from psychosis, has not previously been researched.

The literature is extremely diverse and dissociation is a phenomenon with many facets, difficult to measure unitarily, but which can be conceptualised very specifically through its processes. As a future project, a review of the different conceptual- definitions of dissociation, would seem of value given the diversity of its conceptualisation in the material presented.

Further research is needed to observe what happens to dissociative phenomena throughout the evolution of psychosis and not just in the acute phase of this illness. This work could helpfully include qualitative, patient experience studies and outcome research using tools identified in this review.

This overview of the literature should be considered a preliminary attempt to explore dissociation in recovery as we believe it to be a topic of clinical interest in a time of change in how therapeutic interventions are provided within the mental health services. It would be of interest to replicate the survey and evaluate also the factors which we did not include in this review.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. RM: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization. SC: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. MZ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. RK: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. KR: Writing – review & editing, Validation. CS: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. JW: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mark Walker, the Head of Research and Development Department at the Gloucestershire Health and Care NHS Foundation Trust, for encouraging and supporting this project and the authors’ views expressed in this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

3. Diseth TH. Dissociation following traumatic medical treatment procedures in childhood: a longitudinal follow-up. Dev Psychopathol. (2006) 18:233–51. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060135

4. Dutra L, Bureau JF, Holmes B, Lyubchik A, Lyons-Ruth K. Quality of early care and childhood trauma: A prospective study of developmental pathways to dissociation. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2009) 197:383. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a653b7

5. Bacon T, Kennedy A. Clinical perspectives on the relationship between psychosis and dissociation: utility of structural dissociation and implications for practice. Psychosis. (2015) 7:81–91. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2014.910252

6. Humpston CS, Walsh E, Oakley DA, Mehta MA, Bell V, Deeley Q. The relationship between different types of dissociation and psychosis-like experiences in a non-clinical sample. Conscious Cognit. (2016) 41:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2016.02.009

7. Longden E, Branitsky A, Moskowitz A, Berry K, Bucci S, Varese F. The relationship between dissociation and symptoms of psychosis: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. (2020) 46:1104–13. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa037

8. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Am. Psychiatric Assoc Press (1994).

9. World Health Organisation. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision. Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

10. Van Der Hart O, Dorahy M. Pierre Janet and the concept of dissociation. Am J Psychiatry. (2006) 163:1646–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1646a

11. Beer MD. Psychosis: a history of the concept. Compr Psychiatry. (1996) 37:273–91. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(96)90007-3

12. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Kaplan H. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (2007).

13. Dorahy MJ, Shannon C, Seagar L, Corr M, Stewart K, Hanna D, et al. Auditory hallucinations in dissociative identity disorder and schizophrenia with and without a childhood trauma history: Similarities and differences. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2009) 197:892–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c299ea

14. Renard SB, Huntjens RJ, Lysaker PH, Moskowitz A, Aleman A, Pijnenborg GH. Unique and overlapping symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum and dissociative disorders in relation to models of psychopathology: a systematic review. Schizophr Bull. (2017) 43:108–21. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw063

15. Černis E, Freeman D, Ehlers A. Describing the indescribable: A qualitative study of dissociative experiences in psychosis. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.022909

16. Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc rehabil J. (1993) 16:11–23. doi: 10.1037/h0095655

17. Farrelly S, Peters E, Azis M, David A, Hunter EC. A brief CBT intervention for depersonalisation/derealisation in psychosis: study protocol for a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2016) 2:47. doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0086-7

18. Hwu HG, Chen C, Tso Tsuang M, Tseng WS. Derealization syndrome and the outcome of schizophrenia: A report from the international pilot study of schizophrenia. BJPsych. (1981) 139:313–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.139.4.313

19. Perona-Garcelán S, Cuevas-Yust C, García-Montes JM, Pérez-Álvarez M, Ductor-Recuerda J, Salas-Azcona RM, et al. Relationship between self-focused attention and dissociation in patients with an without auditory hallucinations. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2008) 196:190–7. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318165c7c1

20. Perona-Garcelán S, García-Montes JM, Ductor-Recuerda MJ, Vallina-Fernández O, Cuevas-Yust C, Pérez-Álvarez M, et al. Relationship of metacognition, absorption, and depersonalization in patients with auditory hallucinations. BJPsych. (2012) 51:100–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02015.x

21. Wright A, Fowler D, Greenwood K. Influences on functional outcome and subjective recovery in individuals with and without First Episode Psychosis: A metacognitive model. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 284:112643. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112643

22. Rosen C, Melbourne JK, Grossman LS, Sharma RP, Jones N, Chase KA. Immersion in altered experience: An investigation of the relationship between absorption and psychopathology. Conscious Cognit. (2017) 49:215–26. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2017.01.015

23. Ubeda-Gomez J, Leon-Palacios MG, Escudero-Perez S, Barros-Albarran MD, Perona-Garcelan S, Lopez-Jimenez AM. Relationship between self-focused attention, mindfulness and distress in individuals with auditory verbal hallucinations. Cognit Neuropsychiatry. (2015) 20:482–8. doi: 10.1080/13546805.2015.1089225

24. Perivoliotis D, Grant PM, Beck AT. Advances in cognitive therapy for Schizophrenia: Empowerment and recovery in the absence of insight. Clin Case Stud. (2009) 8:424–37. doi: 10.1177/1534650109351929

25. Lynch S, Holttum S, Huet V. The experience of art therapy for individuals following a first diagnosis of a psychotic disorder: a grounded theory study. Int J Art Ther: Inscape. (2019) 24:1–11. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2018.1475498

26. Ross CA, Keyes BB, Benjamin B. Clinical features of dissociative schizophrenia in China. Psychosis. (2009) 1:51–60. doi: 10.1080/17522430802517641

27. Lysaker PH, Hamm JA, Vohs JK, Marina Pattison ML, Bethany LL, et al. Understanding the course of self-disorders and alterations in self-experience in schizophrenia: Implications from research on metacognition. Curr Psychiatr. (2018) 14:160–70. doi: 10.2174/1573400514666180816113159

28. Lysaker PH, Minor KS, Lysaker JT, Hasson-Ohayon I, Bonfils K, Hochheiser J, et al. Metacognitive function and fragmentation in schizophrenia: Relationship to cognition, self-experience and developing treatments. Schizophr Re: Cognit. (2019) 19:100142. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2019.100142

29. Kumar D, Venkatasubramanian G. Metacognition and mindfulness integrated therapy reduces severity of hallucination in a patient not taking antipsychotic medication. J Cognit Psychother. (2018) 32:192–202. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.32.3.192

30. Pec O, Bob P, Lysaker PH, Probstova V, Leonhardt BL, Hamm JA. The psychotherapeutic treatment of schizophrenia: psychoanalytical explorations of the metacognitive movement. J Contemp Med. (2020) 50:205–12. doi: 10.1007/s10879-020-09452-w

31. Bob P, Mashour GA. Schizophrenia, dissociation, and consciousness. Conscious Cognit. (2011) 20:1042–9. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2011.04.013

32. Johannessen JO, Martindale BV, Cullberg J. (Eds.) Evolving psychosis. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. (2006) pp:238–54.

33. Van der Hart O, Horst R. The dissociation theory of Pierre Janet. J Trauma Stress. (1989) 2:397–412. doi: 10.1007/BF00974598

34. Tellegen A, Atkinson G. Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J Abnorm Psychol. (1974) 83:268–77. doi: 10.1037/h0036681

35. Ross CA, Keyes BB, Yan H, Wang Z, Zou Z, Xu Y, et al. A cross-cultural test of the trauma model of dissociation. J Trauma Dissociation. (2008) 9:35–49. doi: 10.1080/15299730802073635

36. Kelleher I, Wigman JT, Harley M, O'Hanlon E, Coughlan H, Rawdon C, et al. Psychotic experiences in the population: association with functioning and mental distress. Schizophr Res. (2015) 165:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.020

37. Carlson EB, Putnam FW. An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation: Prog Dissociative Disorder. (1993) 6:16–27. doi: 10.1037/t86316-000

38. Butler LD. Normative dissociation. Psychiatr Clin N Am. (2006) 29:45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.004

39. Soffer-Dudek N. Daily elevations in dissociative absorption and depersonalization in a nonclinical sample are related to daily stress and psychopathological symptoms. Psychiatry. (2017) 80:265–78. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2016.1247622

40. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opfer LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261

42. Bowins B. Psychological defense mechanisms: A new perspective. Am J Psychoanal. (2004) 64:1–26. doi: 10.1023/B:TAJP.0000017989.72521.26

43. Bowins B. How psychiatric treatments can enhance psychological defense mechanisms. Am J Psychoanal. (2006) 66:173–94. doi: 10.1007/s11231-006-9014-6

44. Brown RJ. Different types of “Dissociation” Have different psychological mechanisms. J Trauma Dissociation. (2006) 7:7–28. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n04_02

45. Coutts F, Koutsouleris N, McGuire P. Psychotic disorders as a framework for precision psychiatry. Nat Rev Neurol. (2023) 19:221–34. doi: 10.1038/s41582-023-00779-1

46. Burns AM, Erickson DH, Brenner CA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant psychosis: a meta-analytic review. Psychiatr Serv. (2014) 65:874–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300213

47. Fonagy P. The effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapies: an update. World Psychiatry. (2015) 14:137–50. doi: 10.1002/wps.v14.2

48. Bjornestad J, Veseth M, Davidson L, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, et al. Psychotherapy in psychosis: experiences of fully recovered service users. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:1675. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01675

49. Potkin SG, Kane JM, Correll CU, Lindenmayer J-P, Agid O, Marder SR, et al. The neurobiology of treatment-resistant schizophrenia: paths to antipsychotic resistance and a roadmap for future research. NPJ Schizophr. (2020) 6:1. doi: 10.1038/s41537-019-0090-z

50. Correll CU, Howes OD. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: definition, predictors, and therapy options. J Clin Psychiatry. (2021) 82:MY20096AH1C. doi: 10.4088/JCP.MY20096AH1C

51. Panov G. Dissociative model in patients with resistant schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:845493. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.845493

52. Justo A, Risso A, Moskowitz A, Gonzalez A. Schizophrenia and dissociation: its relation with severity, self-esteem and awareness of illness. Schizophr Res. (2018) 197:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.029

53. Kapur S, Seeman P. Does fast dissociation from the dopamine d(2) receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics?: A new hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry. (2001) 158:360–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.360

54. Rao KN, George J, Sudarshan CY, Begum S. Treatment compliance and noncompliance in psychoses. Indian J Psychiatry. (2017) 59:69–76. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_24_17

55. Vogel M, Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. The role of trauma and PTSD-related symptoms for dissociation and psychopathological distress in inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. (2006) 39:236–42. doi: 10.1159/000093924

56. Uyan TT, Baltacioglu M, Hocaoglu C. Relationships between childhood trauma and dissociative, psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: a case-control study. Gen Psychiatr. (2022) 35:e100659. doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2021-100659

Keywords: dissociation, recovery, rehabilitation, psychosis, schizophrenia

Citation: Calciu C, Macpherson R, Chen SY, Zlate M, King RC, Rees KJ, Soponaru C and Webb J (2024) Dissociation and recovery in psychosis – an overview of the literature. Front. Psychiatry 15:1327783. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1327783

Received: 25 October 2023; Accepted: 12 March 2024;

Published: 05 April 2024.

Edited by:

Teresa Sanchez-Gutierrez, University of Cordoba, SpainReviewed by:

Massimo Tusconi, University of Cagliari, ItalyGeorgi Panov Panov, Tracia University, Bulgaria

Copyright © 2024 Calciu, Macpherson, Chen, Zlate, King, Rees, Soponaru and Webb. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claudia Calciu, Y2xhdWRpYWFudGFsekB5YWhvby5jb20=

†ORCID: Claudia Calciu, orcid.org/0000-0001-7326-5366

Claudia Calciu

Claudia Calciu Rob Macpherson1

Rob Macpherson1 Camelia Soponaru

Camelia Soponaru