94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry, 29 February 2024

Sec. Addictive Disorders

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1230699

This article is part of the Research TopicSubstance Use Disorder: Above and Beyond AddictionView all 32 articles

Suzanne Maahs1

Suzanne Maahs1 Denise Leclair2*

Denise Leclair2* Baltazar Gomez-Mancilla3,4

Baltazar Gomez-Mancilla3,4 Brian D. Kiluk5

Brian D. Kiluk5 Velusamy Shanmuganathan Muthusamy6

Velusamy Shanmuganathan Muthusamy6 Partha S. Banerjee6

Partha S. Banerjee6 Shyamashree Dasgupta6

Shyamashree Dasgupta6 Katherine M. Waye1

Katherine M. Waye1Background: Cocaine use disorder (CUD) is characterized by the continued use of cocaine despite serious impacts on life. This study focused on understanding the perspective of individuals with current CUD, individuals in CUD remission, and their supporters regarding current therapies, future therapies, and views on clinical trials for CUD.

Methods: The online bulletin board (OBB) is a qualitative tool where participants engage in an interactive discussion on a virtual forum. Following completion of a screening questionnaire to determine eligibility, individuals in CUD remission and their supporters logged in to the OBB and responded to questions posed by the moderator. Individuals with current CUD participated in a one-time virtual focus group.

Results: All individuals with current CUD and 94% of those in CUD remission reported a diagnosis consistent with CUD or substance use disorder during screening. Individuals with current CUD and their supporters were recruited from the United States (US). Individuals in CUD remission were recruited from five countries, including the US. Individuals with current CUD reported hesitation about seeking treatment due to stigma, a lack of privacy, and being labeled as a drug seeker; barriers to therapy included time, cost, and a lack of privacy. Participants wanted a safe therapy to stop cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Seven clinical trial outcomes, including long-term abstinence and craving control, were suggested based on collected insights.

Conclusion: This study can help inform the design of clinical trials and emphasize the need for effective, safe, and accessible therapies. Recruiting participants will require significant trust building.

Cocaine is used by an estimated 20 million people globally, with an annual prevalence of use of 0.4% among those aged 15–64 years (1). Some of these individuals will develop cocaine use disorder (CUD), which is characterized by meeting at least two Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) criteria such as “hazardous use”, “social or interpersonal problems related to use”, and “neglected major roles due to use” (2). The 2016 Global Burden of Disease study estimated an age-standardized prevalence of 77.6 CUD cases per 100, 000 people worldwide (3). Furthermore, an increase of 39.7% in CUD diagnoses was reported from 2010 to 2016 (4), and rates of overdoses, including cocaine overdoses, have recently increased exponentially (5, 6).

Although there are approved pharmacotherapies for opioid, tobacco, and alcohol use disorders, the treatment options are limited for CUD, with no approved pharmacotherapies in the United States (US) or Europe despite multiple clinical trials in the last several decades (4, 7, 8). Brain stimulation modalities such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) are add-on therapies that have an acute effect on a person’s craving for drugs and alcohol. These modalities are utilized when pharmacological interventions are not successful, but may not always be available in certain regions or considered cost effective (9). Even though psychosocial and behavioral interventions have demonstrated efficacy in CUD, there is no one superior treatment, resulting in the use of a range of therapies (10). These therapies include evidence-based approaches such as individual counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), community reinforcement approach (CRA), and contingency management (CM) (8). These treatments often demonstrate clinical benefit, but long-term abstinence remains elusive for the majority of patients with CUD (7–9, 11).

Clinical trials frequently consider abstinence from cocaine use as the criterion of therapy efficacy (12). However, abstinence can be a difficult outcome to achieve, and may not be the ultimate goal for some patients. Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a status update declaring their interest in the use of novel, non-abstinence-based outcomes as part of product development, along with the development of new products that address a fuller range of symptoms of addiction, such as cravings (13–15).

Clinical trial participation and the response of the participant to psychotherapy are interconnected. Relapse rates are high in substance use disorder (SUD) studies, and dropout is an important predictor of relapse (16). Approximately 30% of participants drop out of SUD trials, and studies targeting cocaine use are associated with higher dropout rates than those involving tobacco smoking and heroin use. Because of this high dropout rate in SUD trials, it is difficult to observe the beneficial effect of treatment.

Supporters (defined here as friends or family members involved in caring for a patient with CUD) also play an important role in the effective treatment of patients with CUD. However, owing to the social stigma associated with CUD, few supporters share their burdens and perspectives, or receive support from their community (17). Some studies have explored the burden of the supporters in taking care of loved ones with alcohol use disorder (18–22) and with SUD (17, 22–24), but, to date, no studies have provided the supporters’ perspectives on CUD and treatment options for the individuals they care for and support.

The online bulletin board (OBB) method used in this study is a moderated, qualitative tool where participants engage in an interactive discussion in an open virtual forum (25). To date, studies using an OBB have provided valuable insights into different health conditions (25–28). To better understand patient and supporter perspectives, the current study used both an OBB and a supplemental virtual focus group to try and determine (1) patient and supporter preferences on an ideal therapy for CUD (2), patient and supporter perspectives on the design and execution of future CUD clinical trials, and (3) clinical trial potential outcomes that are the most important and useful to patients with CUD.

This study was conducted over 2 weeks from February to March 2021 across the following groups: individuals in CUD remission (five OBBs in the US, United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Brazil with individuals who reported they had recovered from CUD); supporters (one OBB in the US with friends or family members of someone with CUD); and individuals with current CUD (one focus group in the US with individuals currently diagnosed with CUD). An external vendor specializing in market research methodologies partnered with BGM, DL, SM, and KW to lead all recruitment, screening, and moderating efforts for the OBB and focus group.

A mix of recruitment methods were used, including contacting participants on market research panels, social media advertising in relevant special interest groups, and referrals from volunteers at rehabilitation clinics. Interested participants would then complete a series of screening questions (18 to 22 questions) over a secure survey platform. They would then receive a follow-up phone call from a trained staff member to confirm their eligibility and schedule their time in the OBB or virtual focus group.

Individuals in CUD remission and their supporters were requested to log in to the OBB for a total of 60 min split across 8 days over a 2-week period and respond to the questions posed by a trained moderator that spoke in the participant’s respective native language. Depending on the day of the OBB, participants were asked anywhere from a total of 5 to 13 questions (Supplementary Material 2: Screeners). Participants were encouraged to engage in anonymous discussions with other participants to exchange their views and experiences.

Individuals with current CUD were requested to join a virtual focus group once for a 90-min discussion that was conducted by a trained moderator who asked a series of 40 open-ended questions that explored the objectives in Section 2.3. The virtual focus group occurred on a confidential online platform (InterVu, FocusVision, USA) to ensure that participant names and/or locations were not displayed. All recordings of the focus group were destroyed after transcription.

For the purpose of simplicity, pharmacological treatments, 12-step programs, and other community mutual help groups were included within the definition of therapies, as many individuals with SUD engage in these programs as an integral part of their remission.

During screening, to qualify as an individual with current CUD, participants had to report the use of “cocaine” or “crack cocaine” regularly, report a diagnosis consistent with CUD or SUD, or answer “yes” to at least five DSM-5 criteria questions about CUD to ensure the inclusion of patients with self-reported CUD to have moderate to severe CUD. Individuals in CUD remission must have said “yes” to regularly using “cocaine” or “crack cocaine” in the past, reported a past history of substance use—including cocaine use—or must have said “yes” to at least five DSM-5 criteria questions to attempt to ensure the inclusion of moderate to severe CUD.

A supporter was defined as a friend or family member of someone who regularly used cocaine. A supporter was eligible to participate if they stated they were caring for or supporting someone currently using “crack cocaine” or “cocaine”. They must have said “yes” to five or more DSM-5 criteria questions about their loved one’s current cocaine use or confirmed a past diagnosis of CUD or SUD.

The study objectives were as follows:

a) Gather participants’ insights into current therapies.

b) Assess satisfaction levels with current therapies.

c) Identify barriers to accessing treatment.

d) Obtain participants’ insights into an ideal future therapy for CUD.

e) Obtain participants’ insights into the design of future clinical trials for CUD therapy.

The main output for the OBB and the virtual focus group was a transcript of the discussion. The OBB also generated some additional outputs, such as images and responses to closed questions (e.g., agreement with statements or polling) that were analyzed alongside the transcripts. The anonymized data underwent thematic analysis by trained staff. Transcripts were reviewed iteratively by several team members to identify and examine key themes and patterns within interviews, within and across markets and patient demographics.

Additional details on the methodology as well as screener, OBB, and focus group questions can be found in the Supplementary Material Sections 1-3.

All individuals with current CUD (N = 5) and 94% of those in remission reported a diagnosis consistent with current or past CUD or SUD. The remaining 6% of those in remission reported cocaine use consistent with CUD by patient history and DSM-5 criteria. Individuals with current CUD and supporters participating in the study were aged 22–49 years (n = 5) and 33–53 years (n = 6), respectively. Those in CUD remission (N = 35) were aged 22–65 years and were from Brazil (n = 7), France (n = 4), Spain (n = 6), US (n = 12), and UK (n = 6). Details of participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

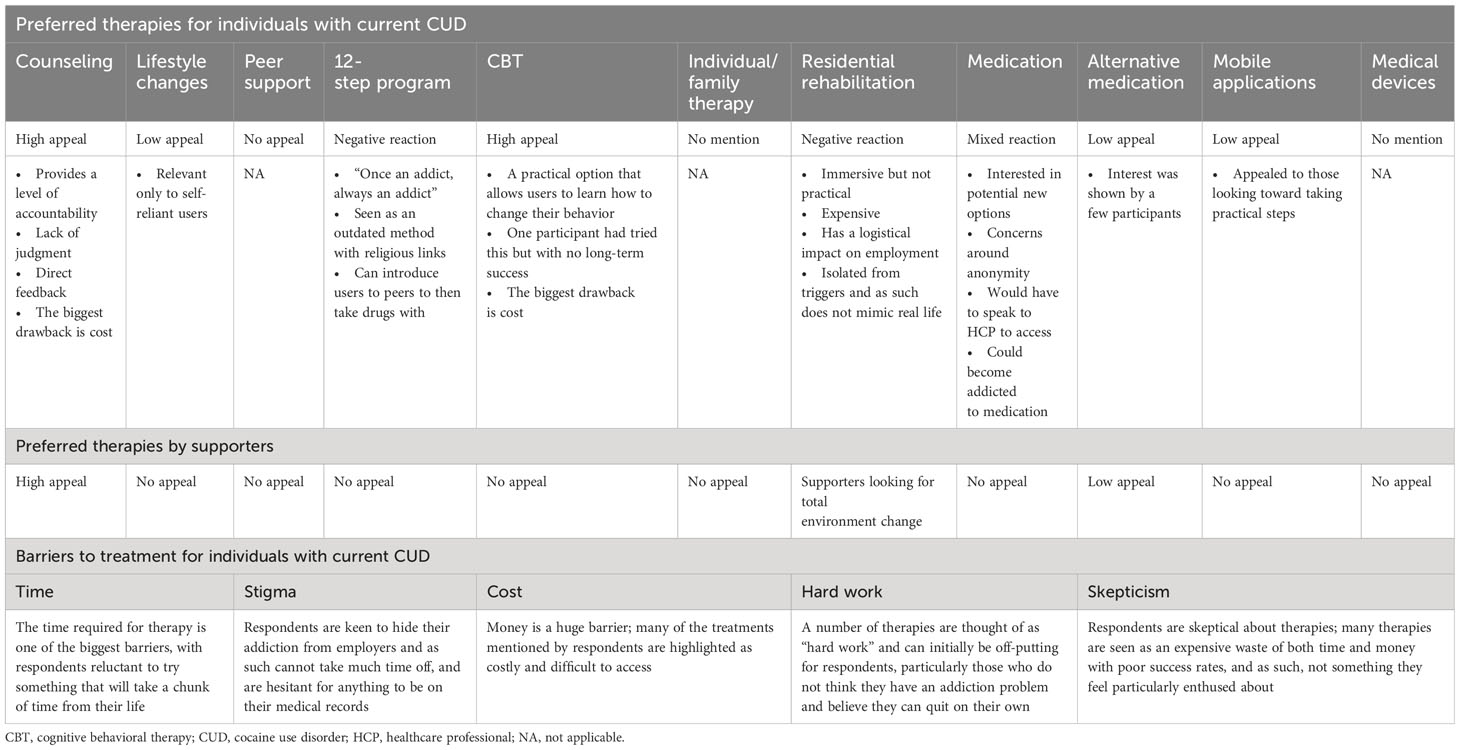

Individuals with current CUD reported moderate satisfaction with available therapies (average score of 4; scale of 1–7, with 7 being the highest possible score). Residential rehabilitation and 12-step programs prompted some negative feedback, while counseling and CBT were preferred. These individuals felt that society considered them as “once an addict, always an addict,” and that admitting they had a problem to a peer support group was challenging. Off-label medications received mixed views, as there were concerns about dependence and having to go to a healthcare professional (HCP). Most considered seeking professional help but were distrustful of HCPs due to concerns about a lack of anonymity or of being judged negatively by the HCP. Those who had approached HCPs were worried about the interventions being documented permanently in their medical records and being perceived as drug seekers in the future. Having a good connection with an HCP was considered a crucial factor for remission (Supplementary Material 4; Table S1).

Lifestyle changes were appealing to individuals with current CUD who were not interested in receiving formal treatment.

This participant group listed several barriers to available therapies, such as the time and effort required, the cost, and skepticism about the effectiveness of therapy. For working professionals, a concern was the potential stigma of requesting medical leave for the treatment of CUD. A summary of current therapies and barriers can be found in Table 2.

Table 2 Insights from individuals with current CUD and supporters regarding current therapies/community mutual help groups used by CUD patients.

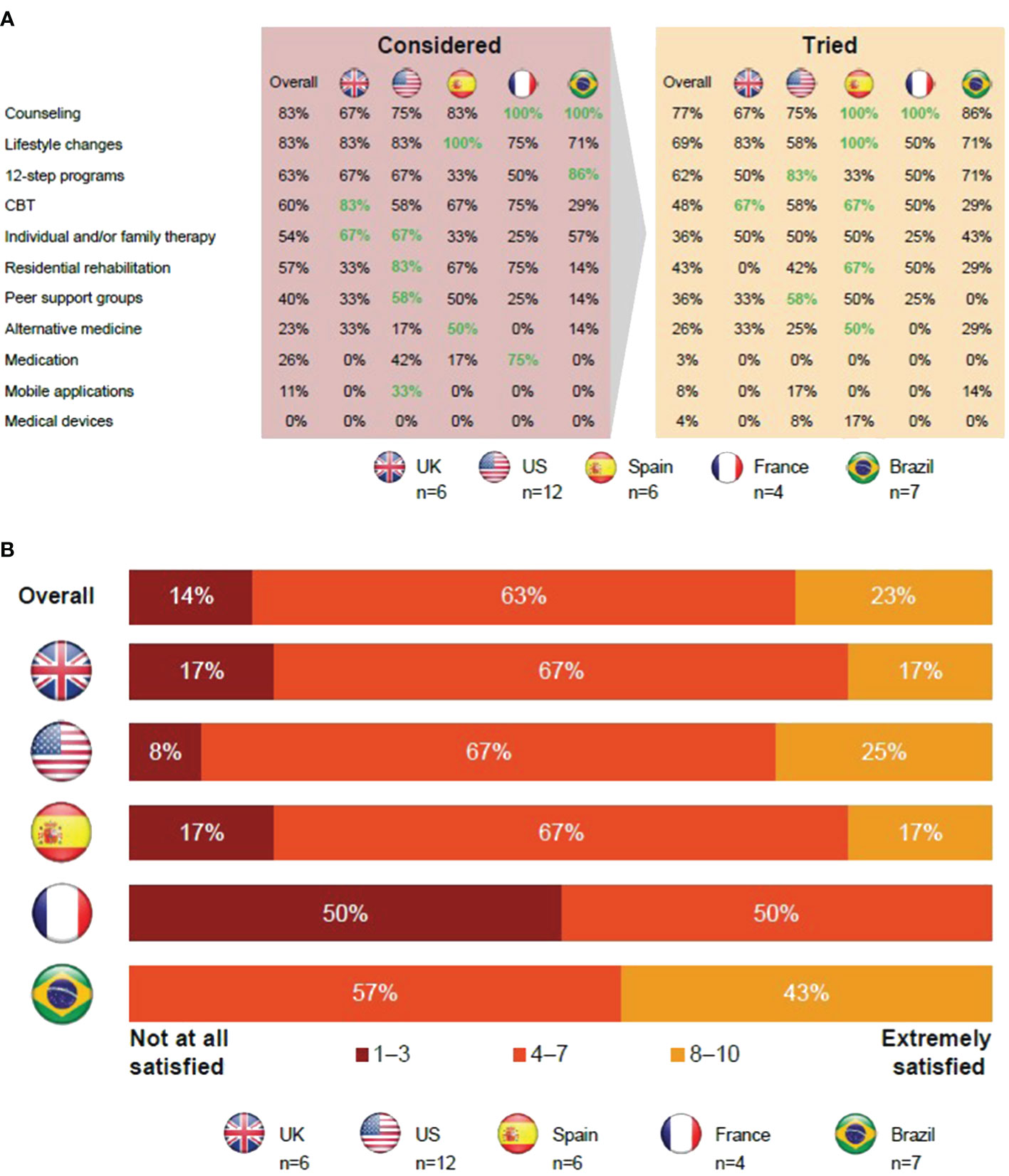

Of those in CUD remission, 86% were satisfied with the available therapies for CUD (Figures 1A, B). Individuals in CUD remission thought that CUD was not taken as seriously as other addictions, such as alcohol or opioid use disorders, so there were fewer options available (Supplementary Material 4; Table S1).

Figure 1 Insights from individuals in CUD remission regarding current therapies for CUD. (A) Those in CUD remission favored 12-step programs and cognitive behavioral therapy. (B) Most individuals in CUD remission were dissatisfied with current therapies. Apps, applications; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; CUD, cocaine use disorder; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Overall, 77% of those in CUD remission tried counseling as a form of treatment, with all participants from Brazil and France attempting it. A majority of the participants highlighted the neutral, judgment-free, professional approach to listening and being provided with useful guidance as the reason for trying counseling. However, either the perceived high cost or lack of health insurance coverage was a barrier for accessing counseling.

The next most commonly tried approaches were lifestyle changes and 12-step programs with 69% and 62% of participants having tried them, respectively. These approaches were reported to have few cost-related barriers; however, participants believed that it was critically important that individuals had sufficient motivation to try these approaches. Peer support groups and 12-step programs were favored by older (aged >49 years) individuals in CUD remission.

The majority of participants considered engaging in CBT, and 48% actually tried it.

In the UK, CBT is available through the National Health Service and can also be free or compulsory if compelled by law enforcement. However, in other locations, participants reported that it may be more difficult to access or find CBT options.

Individual and/or family therapy was tried by 36% of those in CUD remission. Participants thought therapy could help them recover from CUD and address other factors that led to their CUD. Involving family in therapy was viewed as a chance to mend relationships and allows the participant’s family to better understand them. However, participants did state that involving family can be uncomfortable.

For participants in the US, residential rehabilitation was widely known, but the quality of such residential facilities was thought to vary in quality and approach. Residential rehabilitation was favored by those aged <49 years but was also deemed expensive and there was a perceived risk of relapse upon returning to everyday life.

Alternative therapies for CUD, including yoga, reiki, and hypnosis, were not well-known. In addition, only 3% of participants tried medications. Available off-label medications were considered unsuitable due to perceived factors like dependency, side effects, or concerns about being labeled a drug seeker.

Mobile applications were considered convenient but also thought to be impersonal and boring to use. Medical devices were mostly unheard of, and those individuals who were aware of them thought they were expensive and ineffective.

Concerns over lack of confidentiality was another barrier that prevented users from seeking out different therapies. However, participants had fewer concerns about visiting HCPs for medical care compared with those with current CUD.

In summary, in France and Spain, all participants tried counseling, and this was also a common therapy option in Brazil. Medication was considered more frequently in France than elsewhere. On average, the therapies detailed above were used less frequently in the UK than in other countries. Twelve-step programs were most widely used in the US, had a lower uptake in Spain, and were common in Brazil along with mobile applications. Residential rehabilitation was considered an option by participants in the US, but cost was a barrier.

See Supplementary Material 4; Table S1 for a detailed summary of insights from individuals in CUD remission regarding current therapies and barriers.

Residential rehabilitation was favored by supporters looking for a total environment change. However, residential rehabilitation was considered expensive with a perceived risk of relapse upon returning to everyday life (Table 2). Counseling was considered meaningful. Social stigma and concerns over confidentiality were viewed as barriers that prevented their loved ones from seeking out the different therapies.

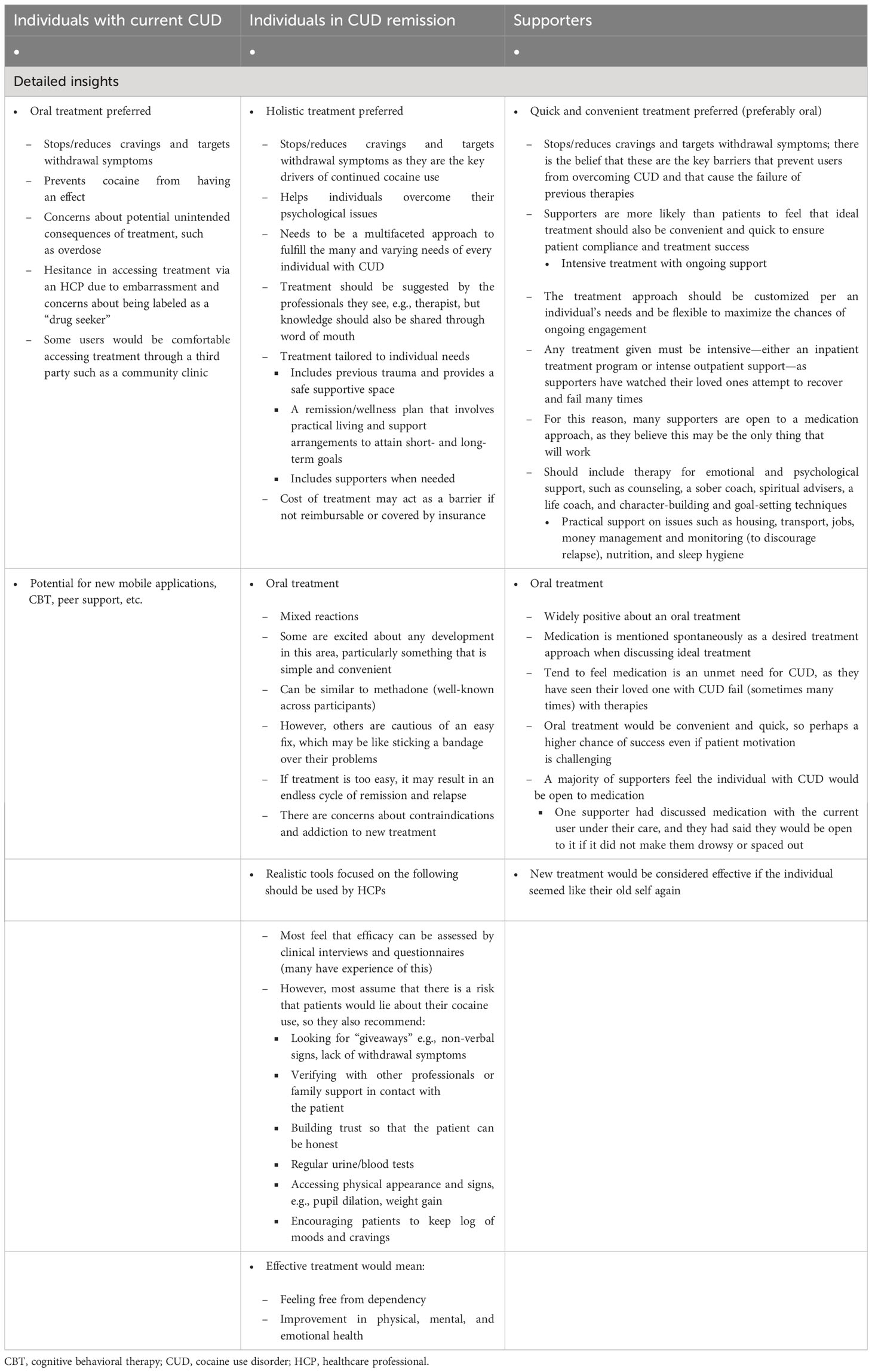

Individuals with current CUD, when prompted to describe an “ideal” therapy, stated that they wanted a therapy that addressed cravings, withdrawal symptoms, and the “lows” of cocaine use (low mood, anxiety, and paranoia caused by the effect of cocaine wearing off) without developing a new addiction (Table 3). Access to these new therapies should be through HCPs but, again, users mentioned hesitancy about approaching HCPs.

Table 3 Insights from participants regarding future therapies, including an ideal tool to measure treatment efficacy.

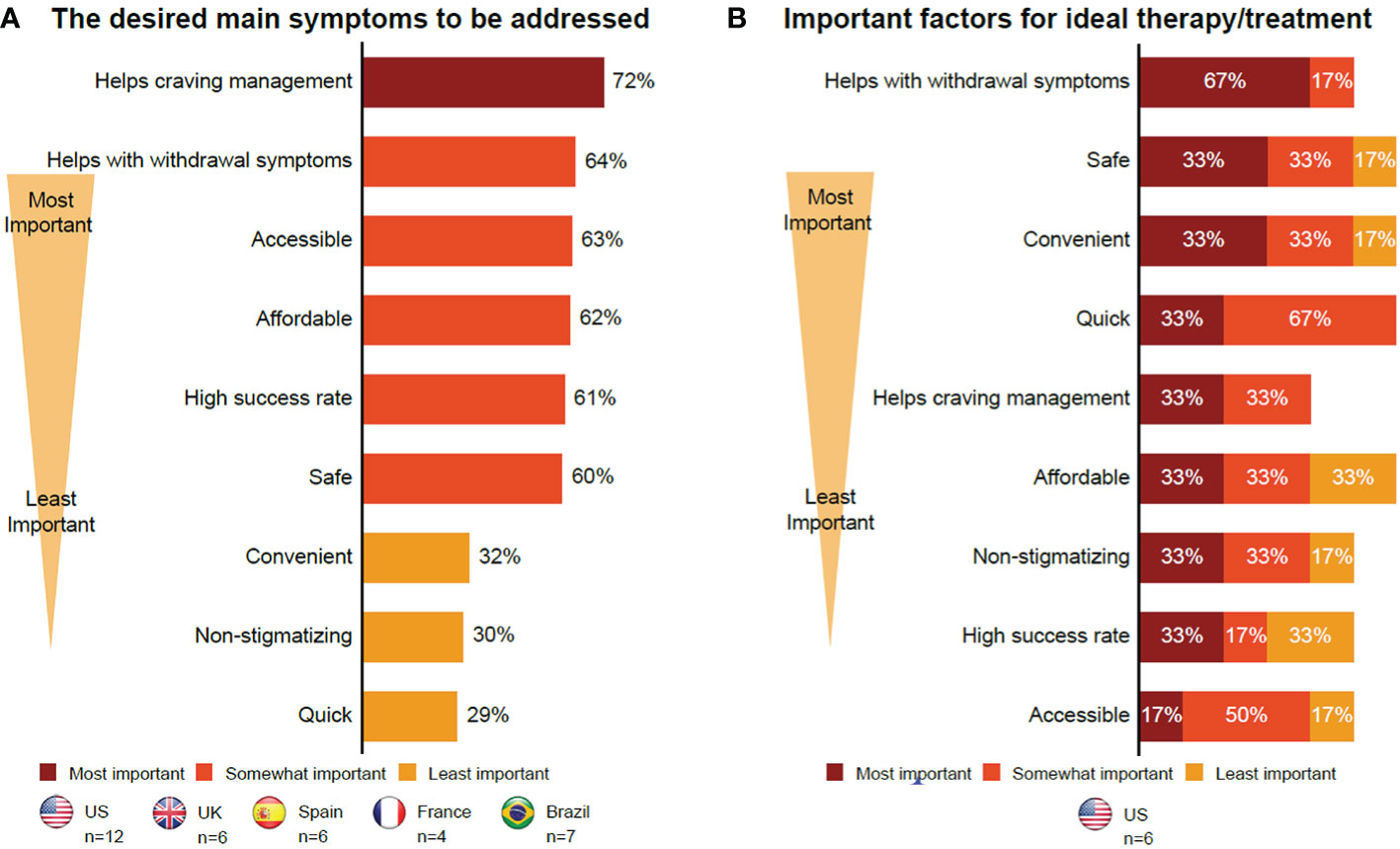

Individuals in CUD remission had similar views on future therapies to those with current CUD, including the importance of new therapies stopping or reducing cravings (72% of participants) and withdrawal symptoms (64% of participants) (Table 3; Figure 2). Individuals in CUD remission were more interested in holistic treatment options that were tailored to individual needs. They felt that if a pharmacological treatment existed, it should exist alongside a support system that would promote physical and mental health, improve one’s quality of life (QoL), and everyday relationships. To determine how individuals are doing on a new therapy, they recommended realistic HCP tools that combined clinical interviews and questionnaires with parameters such as assessment on physical appearance, patient logs on moods and cravings, and verifications with family and other professionals in contact with the patient.

Figure 2 Insights into future therapies. (A) Individuals in CUD remission. (B) Supporters. The format of the focus group with those with current CUD did not allow collection of certain data. Therefore, this group is not included here. CUD, cocaine use disorder; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Supporters wanted therapies, especially pharmacological therapies, that would stop or reduce cravings (33% of participants) and withdrawal symptoms (67% of participants). They also wanted long-term intensive therapies that were holistic and affordable, and included mental support for users and care for supporters (Table 3; Figure 2). They also noted that these therapies should be convenient and quick to ensure compliance and long-term abstinence (Figure 2), with an emphasis on therapies that can improve QoL. Location, treatment flexibility, and willingness to undergo treatment were the barriers cited by the supporters. The cost of therapy was a potential barrier for supporters, if not reimbursable or covered by insurance (Supplementary Material 5; Table S2). Lastly, all participants had mixed views on pharmacological therapies due to concerns about safety, dependence, and an overall concern with pharmacological therapies being “easy fixes” that would cater more to the symptoms than the root causes of their CUD. In their opinion, this could lead to relapse.

Most participants across the three groups were interested in clinical trials (Table 4), but expressed some specific concerns, as outlined below.

Access to free trial medication, an eagerness to advance scientific research on CUD, and assured anonymity were key motivators to participate in a clinical trial (Table 4). Clinical trials were perceived as an opportunity for CUD to be taken more seriously in the medical and scientific fields. However, concerns about the potential side effects of medication and their privacy while being in a clinical trial were cited. Specifically, when prompted about their thoughts on taking medication via a video recording for compliance purposes, most participants were not supportive of this approach as it was considered intrusive. Although privacy was a concern, participants noted that anonymity in a clinical trial could also be a good motivator as they could take a potential trial treatment for their CUD without it being documented in their medical records.

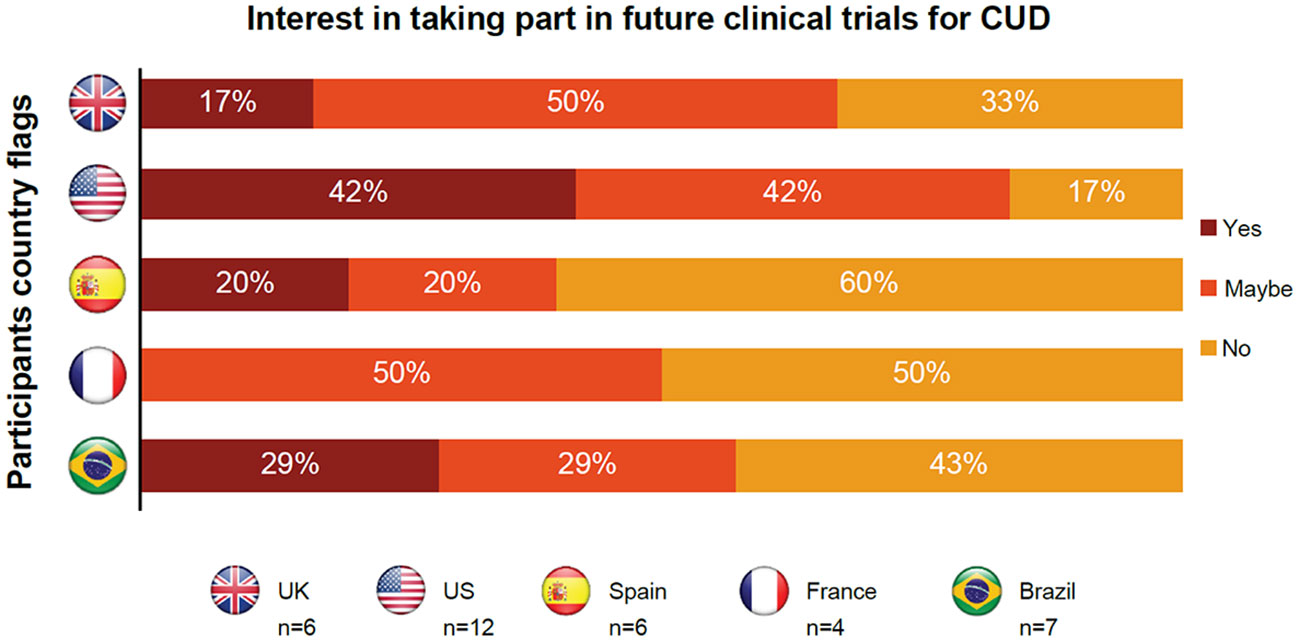

Individuals in remission had overall positive perceptions about participating in clinical trials but were concerned about their privacy and a lack of confidentiality (Table 4). They were also worried about receiving placebo instead of an active treatment. Participants from the US were most interested in clinical trial participation, with 42% of participants showing definite interest and 42% of participants showing possible interest (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Insights from individuals in CUD remission regarding participating in future clinical trials for cocaine use disorder. CUD, cocaine use disorder; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Supporters thought that clinical trials could save lives and provide hope to loved ones who had multiple relapses (Table 4). However, they were skeptical about the willingness of their friends and relatives to participate in these trials due to their loved one’s potential lack of interest in stopping their cocaine use or concerns over confidentiality and privacy. Similar to those with current CUD, supporters were also uncomfortable about their loved ones taking treatment on camera.

Based on the insights collected regarding current and future therapies as well as regarding potential clinical trials, seven outcomes were suggested by participants for the success of a therapy. To achieve long-term abstinence, a blood/urine test was run in only individuals in CUD remission. To stop or reduce cravings, a patient log was maintained, and a clinical interview was conducted in individuals with current CUD and individuals in CUD remission. To feel free from dependency, a patient log was maintained, a clinical interview was conducted, and verifying with other professionals or supporters was done in individuals in CUD remission as well. To improve physical health/prevent long-term problems, a full physical exam and clinical tests were performed in individuals in CUD remission. To improve mental health, an interview with a trusted, empathetic person/read non-verbal signs was conducted in individuals with current CUD, individuals in CUD remission, and supporters. To improve QoL, including with work and relationships, an interview with a trusted, empathetic person/read non-verbal signs was conducted in individuals in CUD remission. To achieve all of the above, a realistic tool that combines clinical interviews and questionnaires with other parameters such as physical appearance, patient logs on moods and cravings, and verifications with family and other professionals in contact with the patient were performed in individuals in CUD remission.

Studies on substance use and SUD have found individual counseling, CBT, and 12-step programs, among others, to be effective interventions (29–31). In the present study, counseling was the most popular therapy. Where it was available, CBT was popular among those looking for practical techniques to support their remission. Peer support groups and 12-step programs were of interest to older individuals in CUD remission (aged >49 years). Those with current CUD and some in remission found it challenging to connect with peers in a group setting and subsequently rejected the 12-step programs as outdated and religious in nature. Those with current CUD thought medication for comorbidities could be useful, but going to an HCP generated concerns about privacy, anonymity, stigma, and documented treatment. Both current and recovered individuals with CUD were concerned about off-label medications leading to dependence, or about being perceived or labeled as drug seekers. Residential rehabilitation was not frequently tried due to the high cost. Alternative medicine was not well-known as a CUD therapy. Medical devices and mobile applications were the least-used approaches for CUD therapy.

Costs of therapy, lack of anonymity, and social stigma were the frequently cited barriers to treatment for all groups of participants in this study, similar to other studies (32). The time required for therapy was a major barrier for those with current CUD, whereas location and flexibility of therapy were a concern for the supporters.

In the present study, those with current CUD were most interested in new therapies, and those in remission and supporters were more focused on other aspects such as psychosocial therapies. Although supporters were looking forward to fast-acting, effective oral therapies, those with current CUD or in remission were fearful about dependence or quick fixes where the root cause remained unaddressed. However, a common point of agreement among all participants was that a new therapy could stop or reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms, and achieve long−term abstinence.

Despite the potential drawbacks identified for clinical trials, such as intrusivity of being filmed if that was part of the clinical trial compliance measures, the interventions and questions in clinical trials as a possible trigger for relapse and paranoia, side effects, and concerns over receiving a placebo, there was a general interest and desire to contribute to science. The anonymity and privacy afforded by a clinical trial setting were also viewed favorably.

Limitations of the study included a modest study sample. Owing to the limitations of the format of the focus group, some questions varied between the OBB and the focus group. Because of cultural differences toward addiction and the willingness to talk about it, individuals with current CUD and their supporters were only from the US, which may have led to bias in the results. Consistent with qualitative research, the patient population was not balanced as in a standard clinical trial. Moreover, some participants (6% of the individuals in CUD remission) had no diagnosis consistent with CUD, although they did have at least five criteria of SUD per DSM-5 criteria.

Experiences with therapy varied among participants, and several attempts were often needed to stop or reduce cocaine use. Satisfaction with the available treatment options was low, with concerns about efficacy, therapies not being tailored to cocaine use, and cost to the patient. A holistic treatment—that is, pharmacological treatment with personalized therapy that helps reduce cravings and is affordable—was considered as ideal. Interest in a potential new oral treatment was mixed, with some concerns around dependence or misuse. Patient information and support tailored to stopping cocaine use would be beneficial, particularly if it is adaptable to the unique psychosocial needs of the individuals with current CUD or in CUD remission.

Long-term abstinence may be the main goal for a clinical trial; however, based on the perspectives of individuals with current or past CUD and supporters, other outcomes such as reduced cravings, improvement in physical and mental health, improvement in QoL, and prevention of long-term problems were also viewed as important considerations for potential clinical trials. Therapy outcomes need to include patient-led evaluation and objectives to realistically assess if the patient is still using cocaine.

Enthusiasm about clinical trials was high among the participants due to the anticipation of improved treatment options specific to CUD. However, those with current CUD reported many barriers to participation, particularly paranoia, which could be worsened if the trial required treatment compliance to be documented by video recording. This study suggests that participants require efforts to be made on building trust and ensuring the privacy of their personal information. Furthermore, although many legal and ethical safeguards exist to ensure anonymity and privacy of a clinical trial participant’s data, this study made it clear that special care must be taken to explain to participants in CUD trials about their privacy rights and provide additional plain language educational materials regarding their privacy rights outside of the informed consent form. Participants had many concerns about their privacy and documentation of a potential CUD prescription drug in their medical record. As medical record privacy is a major barrier to individuals seeking professional help, it is important to identify ways to create an environment of assured privacy and anonymity once a medication is available on the market (e.g., coding the medication in the record).

With a growing interest in patient-informed clinical trial designs, this study highlights the unmet needs of individuals with current, or in remission from, CUD and their supporters. There is an urgent need to continue investing in research for new CUD therapies, given the scope of the problem and the soaring rates of cocaine use globally.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

This study was conducted in accordance with EphMRA guidelines which state that ethics committee approval is not required if study met the criteria of market research. Therefore, Institutional Review Board approval was not sought for this market research study. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and guidelines for Good Epidemiology Practice. Standard procedures were adhered to for the protection of participants’ rights, including written informed consent, data privacy, anonymity, and the right to withdrawal, as well as thorough assessment of the qualifications of the vendor was undertaken. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SM: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, project administration, funding acquisition; writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. DL: Conceptualization and writing the original draft; visualization, supervision, funding and acquisition; reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. BG-M: Conceptualization, methodology, visualization, supervision, funding and acquisition; reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. BK: Visualization and writing the original draft; reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. VSM: Formal analysis and data curation. PB: Conceptualization, methodology, writing the original draft; reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. SD: Writing the original draft and reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. KW: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, visualization, project administration; writing the original draft; reviewing and editing the subsequent drafts. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study received funding from Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research and Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation (Global Health Development Unit, GDD), Basel, Switzerland.

The authors thank all of the participants of this study. They are also thankful to Adelphi Research, an independent market research agency, for conducting the OBB and the focus group, and compiling the data. The authors thank Shyamashree Dasgupta and Praful Narayan Kamble (NBS CONEXTS, Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd.) for assistance in writing the manuscript, formatting, referencing, preparing tables and figures, incorporating the authors’ revisions.

BG-M was employed by Novartis Pharma AG at the time of this study. He is now employed by McGill University. DL, KW, SD, PB, VSM, and SM are employed by Novartis. BK is a paid consultant to CBT4CBT, LLC, which provides a digital CBT program to qualified clinical providers and organizations on a commercial basis. This conflict is managed by Yale University.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research and Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation (Global Health Development Unit, GDD). The funder had the following involvement with the study: collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1230699/full#supplementary-material

1. UNODC. World Drug Report 2021, Booklet 4 - Drug market trends: Cocaine, Amphetamine-type stimulants. Vienna, Austria: United Nations Publication (2021). Available at: https://www.unodc.org/res/wdr2021/field/WDR21_Booklet_4.pdf

2. Hasin DS, O'Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, et al. Dsm-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. (2013) 170:834–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782

3. Alcohol GBD, Drug Use C. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. (2018) 5:987–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7

4. Brandt L, Chao T, Comer SD, Levin FR. Pharmacotherapeutic strategies for treating cocaine use disorder-what do we have to offer? Addiction. (2021) 116:694–710. doi: 10.1111/add.15242

5. Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2018. NCHS Data Brief. (2020) 356):1–8.

6. McCall Jones C, Baldwin GT, Compton WM. Recent increases in cocaine-related overdose deaths and the role of opioids. Am J Public Health. (2017) 107:430–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303627

7. Bentzley BS, Han SS, Neuner S, Humphreys K, Kampman KM, Halpern CH. Comparison of treatments for cocaine use disorder among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e218049. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8049

8. Kampman KM. The treatment of cocaine use disorder. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaax1532. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax1532

9. Salling M, Martinez D. Brain stimulation in ddiction. Neuropsychopharmacol. (2016) 41:2798–809. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.80

10. Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. (2008) 165:179–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851

11. Penberthy JK, Ait-Daoud N, Vaughan M, Fanning T. Review of treatment for cocaine dependence. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. (2010) 3:49–62. doi: 10.2174/1874473711003010049

12. Czoty PW, Stoops WW, Rush CR. Evaluation of the "Pipeline" for development of medications for cocaine use disorder: A review of translational preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical trial research. Pharmacol Rev. (2016) 68:533–62. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011668

13. USFDA. Opioid Use Disorder: Endpoints for demonstrating effectiveness of drugs for treatment guidance for industry. (2020). Available at: https://https://www.fda.gov/media/114948/download

14. Gottlieb S. Remarks from Fda Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., as Prepared for Oral Testimony before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce Hearing, “Federal Efforts to Combat the Opioid Crisis: A Status Update on Cara and Other Initiatives. Administration USFD (2017). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm582031.htm

15. Kiluk BD, Carroll KM, Duhig A, Falk DE, Kampman K, Lai, et al. Measures of outcome for stimulant trials: Acttion recommendations and research agenda. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2016) 158:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.004

16. Lappan SN, Brown AW, Hendricks PS. Dropout rates of in-person psychosocial substance use disorder treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. (2020) 115:201–17. doi: 10.1111/add.14793

17. Uluyol FM, Bademli K. Feelings, thoughts and experiences of caregivers of individuals with substance use disorder. ADDICTA: Turkish J Addict. (2020) 7:199–205. doi: 10.5152/addicta.2020.20055

18. Vaishnavi R, Karthik MS, Balakrishnan R, Sathianathan R. Caregiver burden in alcohol dependence syndrome. J Addict. (2017) 2017:8934712. doi: 10.1155/2017/8934712

19. Swaroopachary R, Kalasapati L, Ivaturi S, Reddy C. Caregiver burden in alcohol dependence syndrome in relation to the severity of dependence. Arch Ment Health. (2018) 19:19–23. doi: 10.4103/amh.Amh_6_18

20. Shekhawat BS, Jain S, Solanki HK. Caregiver burden on wives of substance-dependent husbands and its correlates at a tertiary care centre in Northern India. Indian J Public Health. (2017) 61:274–7. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_396_16

21. Rospenda KM, Minich LM, Milner LA, Richman JA. Caregiver burden and alcohol use in a community sample. J Addict Dis. (2010) 29:314–24. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2010.489450

22. Kadam K, Unnithan V, Mane M, Angane A. Brewing caregiver burden: Indian insights into alcohol use disorder. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. (2020) 36:236–42. doi: 10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_117_19

23. Maina G, Ogenchuk M, Phaneuf T, Kwame A. "I can't live like that": The experience of caregiver stress of caring for a relative with substance use disorder. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2021) 16:11. doi: 10.1186/s13011-021-00344-3.25

24. Mannelli P. The burden of caring: Drug users & Their families. Indian J Med Res. (2013) 137:636–8.

25. Cook NS, Nagar SH, Jain A, Balp MM, Maylander M, Weiss O, et al. Understanding patient preferences and unmet needs in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (Nash): Insights from a qualitative online bulletin board study. Adv Ther. (2019) 36:478–91. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0856-0

26. Patalano F, Gutzwiller FS, Shah B, Kumari C, Cook NS. Gathering structured patient insight to drive the pro strategy in copd: Patient-centric drug development from theory to practice. Adv Ther. (2020) 37:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01134-x

27. Griffiths KM, Reynolds J, Vassallo S. An online, moderated peer-to-peer support bulletin board for depression: User-perceived advantages and disadvantages. JMIR Ment Health. (2015) 2:e14. doi: 10.2196/mental.4266

28. Cook NS, Tripathi P, Weiss O, Walda S, George AT, Bushell A. Patient needs, perceptions, and attitudinal drivers associated with obesity: A qualitative online bulletin board study. Adv Ther. (2019) 36:842–57. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-00900-1

29. Magill M, Ray L, Kiluk B, Hoadley A, Bernstein M, Tonigan JS, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: Treatment efficacy by contrast condition. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2019) 87:1093–105. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000447

30. Bøg M, Filges T, Brännström L, Jørgensen A-MK, Fredrikksson MK. 12-step programs for reducing illicit drug use. Campbell Systematic Rev. (2017) 13:1–149. doi: 10.4073/csr.2017.2

31. McGovern MP, Lambert-Harris C, Alterman AI, Xie H, Meier A. A randomized controlled trial comparing integrated cognitive behavioral therapy versus individual addiction counseling for co-occurring substance use and posttraumatic stress disorders. J Dual Diagn. (2011) 7:207–27. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2011.620425

Keywords: cocaine use disorder, online bulletin board, individuals with current cocaine use disorder, individuals in cocaine use disorder remission, unmet needs, clinical trial outcomes

Citation: Maahs S, Leclair D, Gomez-Mancilla B, Kiluk BD, Muthusamy VS, Banerjee PS, Dasgupta S and Waye KM (2024) Patient perspectives on current and potential therapies and clinical trial approaches for cocaine use disorder. Front. Psychiatry 15:1230699. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1230699

Received: 29 May 2023; Accepted: 30 January 2024;

Published: 29 February 2024.

Edited by:

Dasiel Oscar Borroto-Escuela, Karolinska Institutet (KI), SwedenReviewed by:

Sean Regnier, University of Kentucky, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Maahs, Leclair, Gomez-Mancilla, Kiluk, Muthusamy, Banerjee, Dasgupta and Waye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denise Leclair, ZGVuaXNlLmxlY2xhaXJAbm92YXJ0aXMuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.