- 1Zodiak, Prinsenstichting, Purmerend, Netherlands

- 2Department of Clinical Psychology, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3Psychotrauma Practice, Rha, Netherlands

- 4Department of Special Needs Education, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 5Vrije Universiteit, Medical Library, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 6Department of Clinical Psychology, Biological Psychology, and Psychotherapy, University of Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Introduction: People with intellectual disabilities (ID) are at increased risk for developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Emerging evidence indicates that Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is feasible and potentially effective for this group. However, communication, cognition, stress regulation, and attachment difficulties may interfere with the EMDR process. Adaptation of the EMDR protocol seems therefore required for this population.

Aim: This review aims to systematically identify and categorize the difficulties in applying EMDR to people with ID and the adaptations made by therapists to overcome these challenges.

Methods: A literature search was performed in May 2023. Article selection was based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and quality appraisal.

Results: After screening, 13 articles remained for further review. The identified difficulties and adaptations were categorized into the three domains of adaptive functioning (i.e., conceptual, social, and practical functioning). Considerable difficulties in applying the EMDR protocol for this group were reported. The adaptations made by therapists to overcome these difficulties were highly variable. They could be divided into three main categories: adaptions in EMDR delivery (e.g., tuning to the developmental level of the client, simplifying language, decreasing pace), involvement of others (e.g., involving family or support staff during or in between sessions), and the therapeutic relationship (e.g., taking more time, supportive attitude).

Discussion: The variability of the number of mentioned difficulties and adaptations per study seems to be partly related to the specific EMDR protocol that was used. In particular, when the Shapiro adult protocol was administered, relatively more detailed difficulties and adaptations were described than in publications based on derived existing versions of an EMDR protocol for children and adolescents. A probable explanation is that already embedded modifications in these protocols facilitate the needed attunement to the client’s level of functioning.

Practical implications: The authors of this review suggest that EMDR protocols for children and adolescents could be adapted for people with an intellectual disability. Further research should focus on the involvement of trusted others in EMDR therapy for people with ID and the therapeutic relationship from an attachment and relational-based perspective.

Introduction

Children and adults with intellectual disabilities (ID) are at increased risk for adverse life experiences and trauma-related mental health problems (1, 2). ID is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a condition characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual and adaptive functioning (3). An IQ score of 70 or below means that there is a significant cognitive deficit. Adaptive functioning includes the conceptual, social, and practical domains (3). These domains contain skills that are learned and performed by people in their everyday lives and can be assessed with instruments such as Vineland-3 and the ADaptive Ability Performance Test (ADAPT) (3–5). The conceptual domain involves skills regarding memory, language, problem-solving, and judgment in novel situations. The social domain involves skills concerning awareness of others’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences; empathy, and communication. Finally, the practical domain contains skills concerning learning and self-management across life settings.

In the common population, the lifetime prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is estimated at 5–10% (6, 7). For individuals with ID, however, the prevalence rates of PTSD vary between 10 and 40% and are even higher in, for example (forensic) mental healthcare settings (8, 9). This relatively high risk for developing PTSD for people with ID appears to be caused by three factors.

First, people with ID are more frequently exposed to interpersonal traumatic events, such as physical, sexual, and emotional violence (10, 11). Second, a lower level of cognitive functioning is a well-known risk factor for the development of PTSD after traumatic exposure (12–14). Third, people with ID may also be more susceptible to the effects of upsetting and traumatic experiences due to impairments in stress regulation and adaptability (15, 16).

Despite the increased risk of developing PTSD, trauma-related symptoms often remain undiagnosed and untreated (17). This is partly caused by diagnostic overshadowing: classifying the core of the individual’s difficulties as a consequence of ID rather than trauma, leading to referral toward behavior-based rather than trauma-based therapies (18). Furthermore, limited cognitive and verbal abilities can hinder traditional treatment approaches that often rely on verbal communication (19, 20). Successful engagement in trauma-based therapy might also be complicated by challenges in establishing and maintaining therapeutic relationships with people with ID (21). The challenges are caused by an increased risk of attachment difficulties, such as interpersonal distrust, overly depending on other persons for support and preoccupation about possible abandonment (22).

The fact that PTSD is over-represented and poorly treated in the ID population requires feasible, safe, and effective trauma-focused psychological interventions for this specific group (23). For the treatment of PTSD in the common population, trauma-focused Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2013) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2018) guidelines (24). EMDR therapy might be a more suitable intervention for people with ID and PTSS because it is less reliant on verbal abilities than CBT (25, 26). The focus of this review therefore will be on EMDR therapy.

EMDR therapy is a protocolled, psychotherapeutic approach developed by Shapiro (27). It aims to resolve symptoms related to disturbing and unprocessed life events. According to Shapiro’s Adaptive Information Processing Model (AIP) experiencing a traumatic event might coincide with insufficient information processing and a lack of integration with existing memory networks. This results in the memory of the traumatic event being stored in its “raw” form along with associated disturbed thoughts, sensations, and emotions. The traumatic memory remains unprocessed which results in symptoms of PTSD and a wide range of other disorders (26).

EMDR therapy consists of a structured eight-phase method. Phase 1 encompasses history-taking and case formulation. Phase 2 is the preparation phase; the client is prepared for the therapy. Phase 3 focuses on determining the target memory. During phases 4–6, memory processing to adaptive resolution takes place. An important part of the procedure is the performance of a working-memory-demanding task, for example, the therapist moves his/her fingers back and forth in front of the participant and asks him/her to track the movements, while the participant focuses on the trauma memory. Repeatedly, the participant is asked to report about emotional, cognitive, and somatic sensations that appear. Distress level during this traumatic memory recall is measured using subjective units of distress (SUD). The installation phase (5) aims to associate positive cognition with a traumatic memory to avoid distressing dysfunctional responses. The Validity of Cognition (VOC) scale is applied to measure whether the participant truly believes this positive cognition. Phase 7 is dedicated to closing down the session and preparing the participant for the period between sessions. Phase 8 consists of re-evaluation and integration (26). Although the EMDR protocol does not provide an explicit description of the required therapeutic relationship, Shapiro (26) mentions the importance of establishing a firm therapeutic alliance. The client and clinician should have established a sufficient level of trust before EMDR processing should be initiated, and the clinician should offer compassion and unconditional support.

The standard EMDR protocol can be adapted for children and adolescents, necessitating modifications in language, tools, and technical aspects to align with their cognitive and developmental abilities (28, 29). The eight phases of the EMDR protocol are applied with considerations for the child’s age, level of development, and life context. Emphasis is placed on assessing explicit and nonverbal communication. The phases involve establishing a therapeutic relationship, explaining EMDR, determining family involvement, target identification, desensitization, adaptive resolution, positive cognition installation, body scan, closure, and re-evaluation. For children, target selection and bilateral stimulation may involve special objects, toys, drawings, or other therapeutic tools (28, 29).

The effectiveness of EMDR in PTSD has been established in various meta-analyses (30–32). According to NICE guidelines, EMDR is indicated in the treatment of PTSD for adults and should also be considered for children and young people aged 7 to 17 years. Research suggests that EMDR therapy could also be effective for children and adolescents with PTSD (33). NICE guidelines, however, lack information concerning effective treatment for PTSD for people with ID. Emerging evidence indicates that EMDR is feasible and potentially effective for people with ID and PTSD (23, 34–37). Nonetheless, according to a randomized controlled feasibility trial conducted by Karatzias et al., EMDR, although generating improvements in PTSD symptoms, showed no significant improvement compared to standard therapy (38). Unfortunately, scientific evidence in this field is limited and fragmented, with only a few controlled case studies, including the one mentioned above by Karatzias and colleagues. Furthermore, these studies differ in their study design, population characteristics, and the use of the (adapted) EMDR protocol, making it challenging to assess their effectiveness (23). Four literature reviews on the effectiveness of EMDR for people with ID were conducted in the past years (15, 23, 34, 39). These studies suggest that EMDR may be an effective treatment for people with ID and PTSD. However, in their scoping review, Smith and colleagues suggest that EMDR in people with ID may be less efficacious than previously thought. Moreover, they notice, between studies, an apparent difference in the protocols used and adaptations in administering EMDR. Therefore, Smith and colleagues highlight the need for future research, to develop a reliable EMDR protocol suitable for this target group.

As stated before in this introduction, successful engagement in psychological (trauma) therapy for people with ID is complicated due to cognitive deficiencies, limited social and communicative skills, and attachment difficulties (22, 40, 41). We assume that these problems would also influence the process of EMDR therapy for people with ID and that adaptations are therefore required. Creating a safe and accepting therapeutic relationship, an important precondition for conducting EMDR (26) may form a particular challenge in EMDR therapy for people with ID. Their less effective coping strategies and attachment difficulties could demand more support in reducing stress during the recall of traumatic memories (22, 42). People with ID are often more likely to have relationships based on practical support than on emotionally focused support (43). Further, their position in relationships is weakened by difficulties in communication and comprehension. Developing a therapeutic relationship in which the client’s emotions are the focus, will therefore be challenging (43).

To our awareness, no systematic literature overview is available that specifically addresses these challenges regarding the delivery of EMDR to people with ID as described in our introduction (e.g., cognitive and communicative impairments, difficulties with attachment, and coping strategies), as well as possible solutions and adaptations. A detailed overview of difficulties related to, and adaptations regarding the use of the EMDR protocol for people with ID can be relevant to overcome challenges and thereby improve the acceptability and quality of EMDR treatment and therapy outcomes for this group (16). Additionally, such information might contribute to constructing a reliable EMDR protocol suitable for people with an ID that could be used in further research. This study aims, therefore, to systematically identify and categorize the difficulties in applying EMDR to people with ID and adaptations made so far by therapists to overcome these challenges.

Methods

Literature review

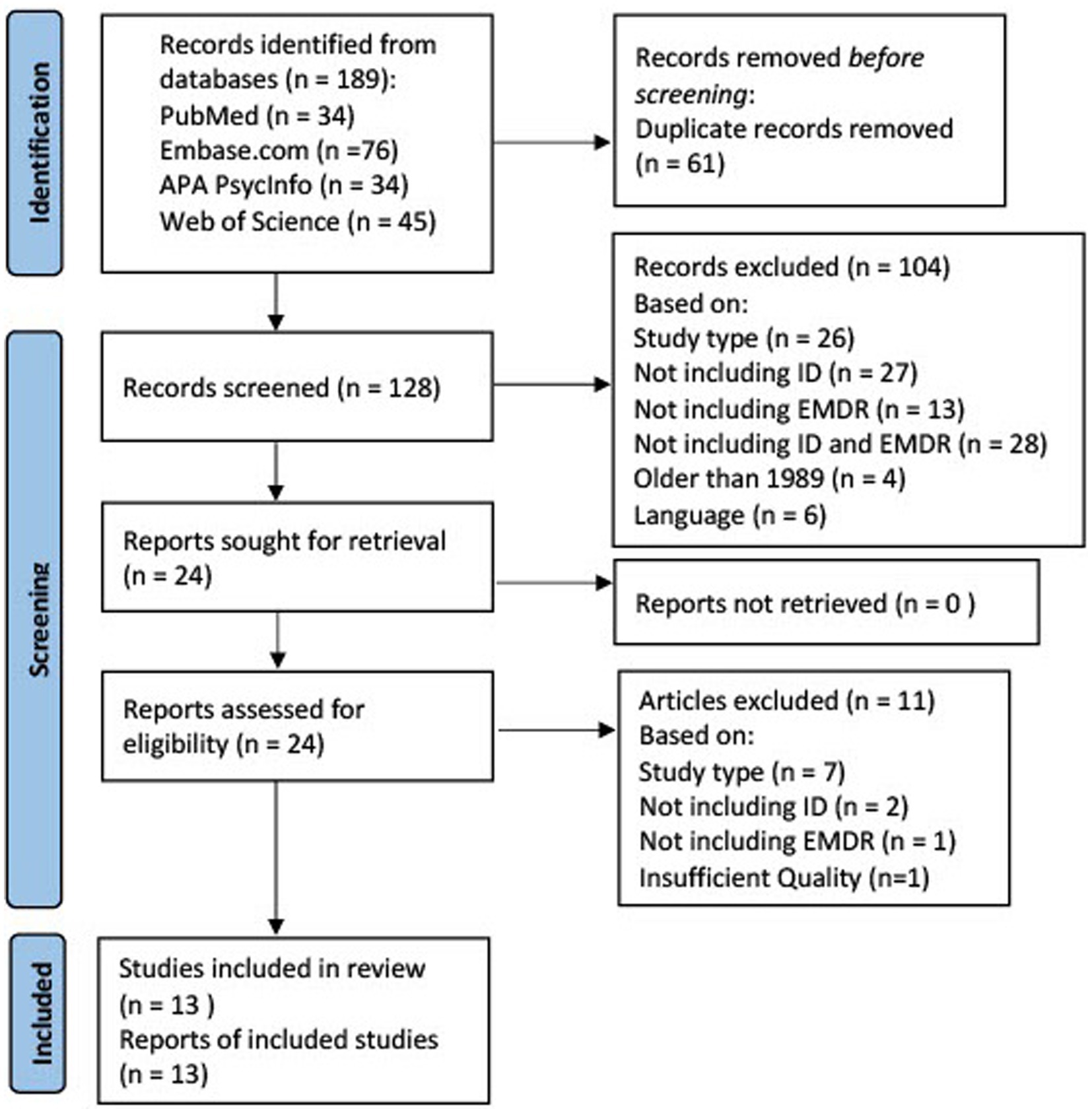

This systematic literature review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (44).

Search strategy

To identify all relevant publications, systematic searches were conducted in the bibliographic databases PubMed, Embase, APA PsycInfo (Ebsco), and Web of Science (Core Collection) from inception up to May 1, 2023, in collaboration with a medical information specialist. The following terms were used (including synonyms and closely related words) as index terms or free-text words: “Eye Movement Desensitization,” “Intellectual Disability,” and “Cognitive Dysfunction.” Duplicate articles were excluded using Endnote X20.0.1 (Clarivate™), following the Amsterdam Efficient Deduplication (AED)-method (45) and the Bramer method (46). The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the Supplementary material.

Selection process

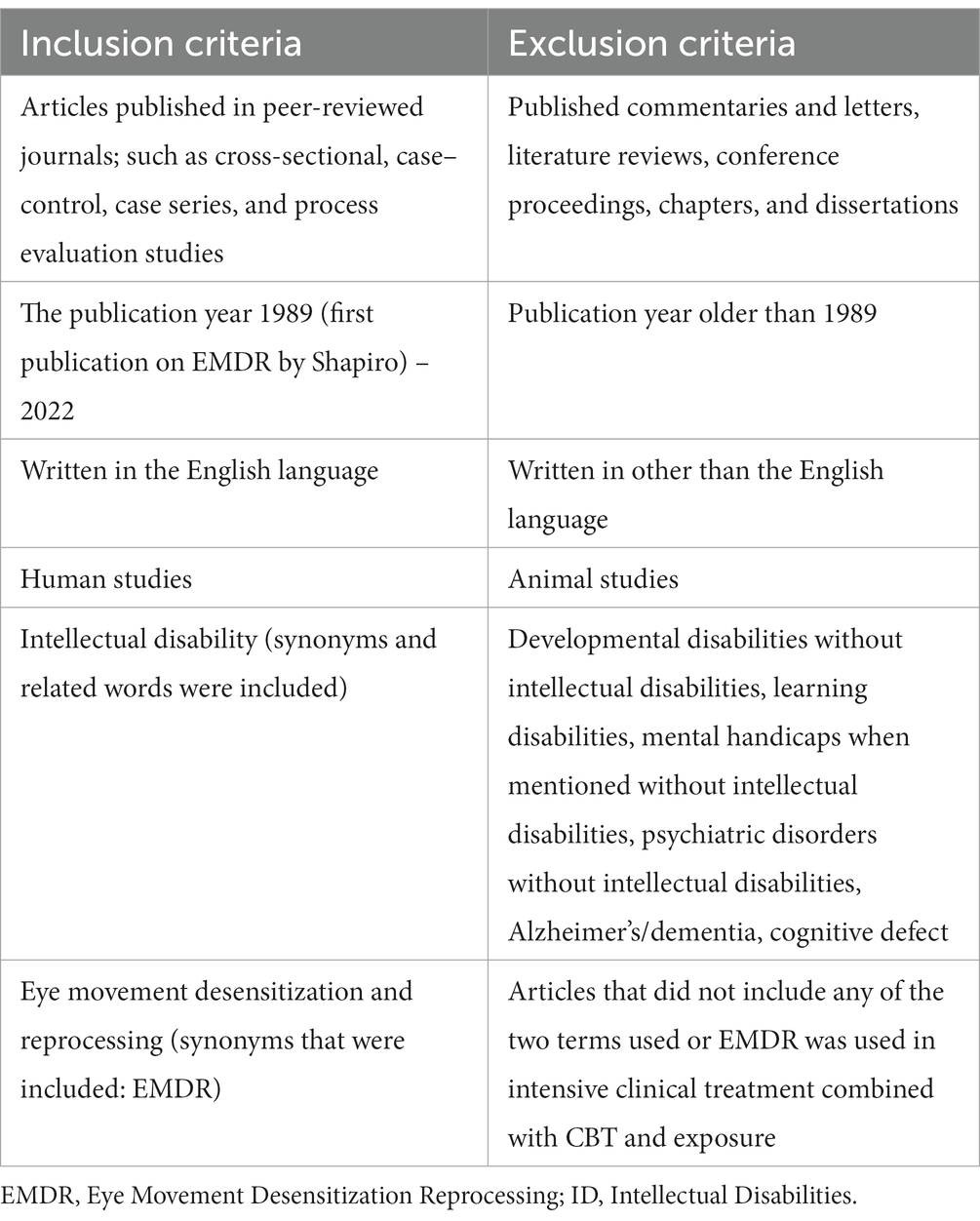

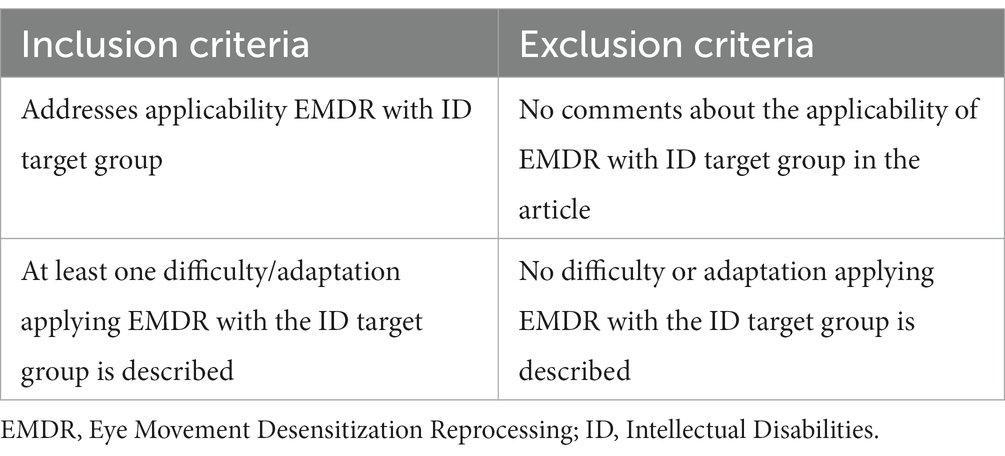

Three authors (SS, NdK, LM) independently screened all potentially relevant titles and abstracts for eligibility. Differences in judgment were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. Studies were included if they met the criteria in Table 1. The full text of the selected articles was obtained for further review. The same three authors did an additional full-text screening. Differences in judgment were, again resolved by discussing them until consensus was reached. Studies were only included if they met the criteria displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for EMDR treatment for people with intellectual disabilities.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria full text for EMDR treatment for people with intellectual disabilities.

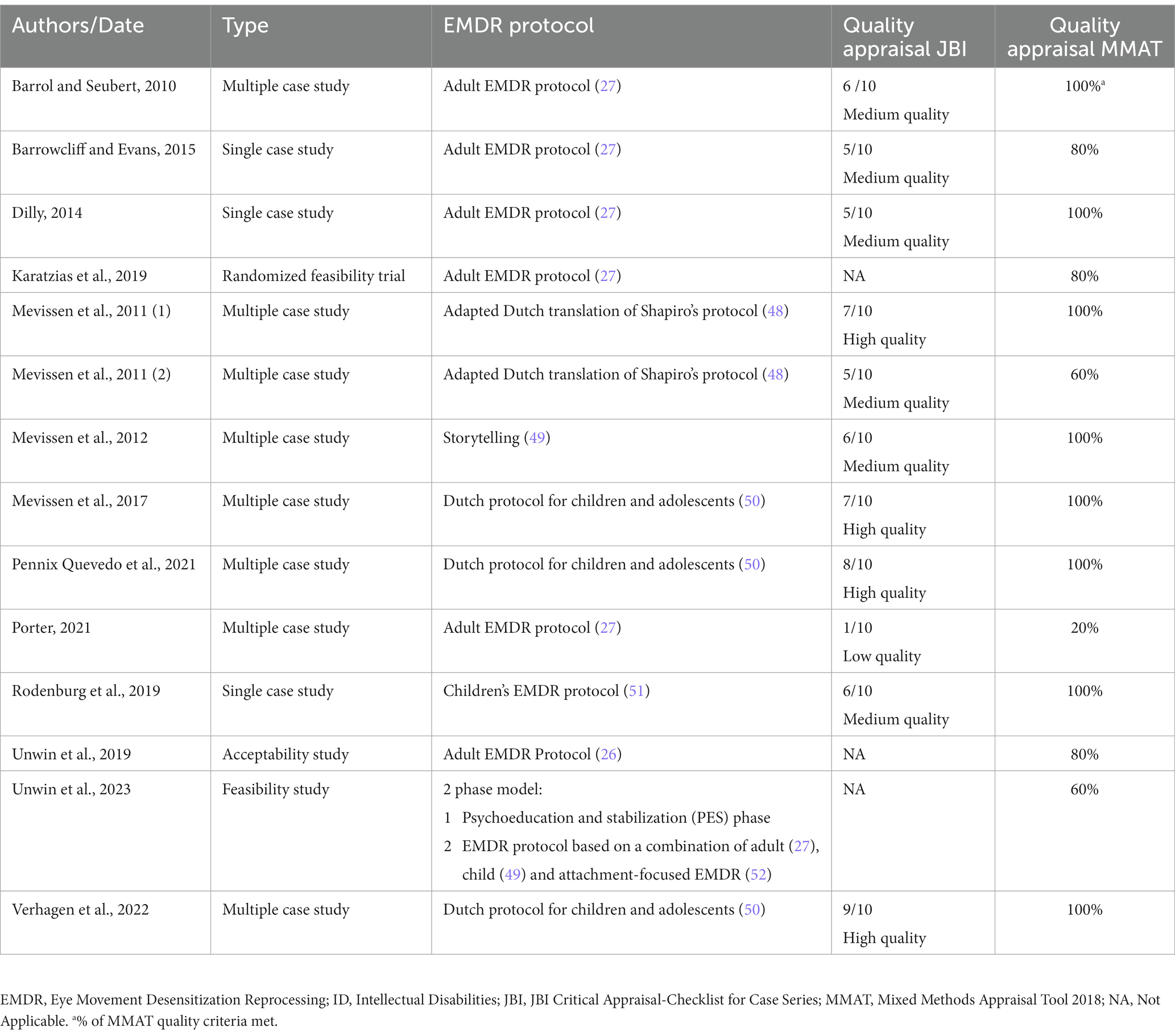

The three authors then independently evaluated the methodological quality of the full texts using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series (47). This checklist includes 10 questions addressing the internal validity, risk of bias in case series designs (e.g., confounding, selection, and information bias), and report clarity. The following quality thresholds were used: low quality (0–33% of criteria met), medium quality (34–66% of criteria met), and high quality (at least 67% or more of criteria met). Table 3 presents details of the quality assessment. A second quality appraisal was performed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, MMAT 2018 (53). This tool addresses the methodological quality of five categories of studies: qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods studies. Only studies of medium and high quality were included for further analyses. Differences in judgment were resolved through consensus.

Data extraction and assessment

The first author screened each included study for explicitly mentioned difficulties and adaptations in applying EMDR to people with ID. Subsequently, findings over all studies were combined, labeled according to the corresponding phase in the EMDR process, and categorized into the three domains of adaptive functioning: the cognitive/conceptual, social, and practical domains (3).

Results

Search results

The literature search generated a total of 189 references. After removing duplicates 13 references remained. Figure 1 displays the flowchart of the search and selection procedure.

In total, 13 articles were analyzed after exclusion: 10 case studies, one randomized feasibility trial, one acceptability, and one feasibility study. Tables 3–7 summarize our findings. Table 3 gives an overview of the included study, the study characteristics, the EMDR protocol that was used, and the results of the quality appraisal. The results of the quality appraisal show that four of the case studies yielded a methodological high quality on JBI and a 100% MMAT score. Another four case studies were considered to have a medium quality on JBI and a 100% MMAT score. The two remaining case studies reached a JBI medium quality and an MMAT score of, respectively, 80 and 60%. The RCT (29 participants, effect size ηp2 = 0.07–0.22) obtained a 100% MMAT score. The acceptability and feasibility studies were granted an MMAT score of, respectively, 80 and 60%. After the quality appraisal, one study of low quality, Porter (2022), was excluded. A detailed overview of the quality appraisal can be obtained through the first author of this review.

In the included studies, EMDR was administered by therapists with various levels of training and experience, both in EMDR itself and in working with individuals with ID. The provided EMDR therapy was based on the Shapiro EMDR Adult or Child protocols (26), the Dutch translation of Shapiro’s protocol (48), or the Dutch protocol for children and adolescents (50), including the Storytelling method (49). In addition, we found high variability in the number of EMDR sessions offered (between 3 to 25 sessions) and the length of the sessions (45 up to 120 min).

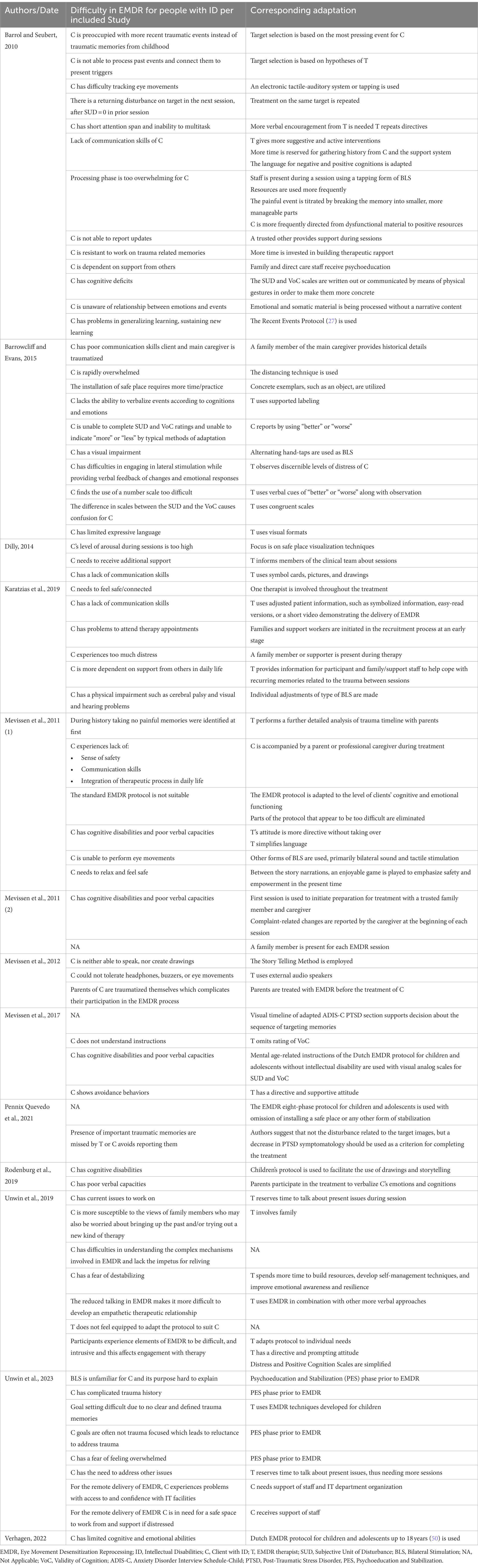

Most studies found positive effects of EMDR. Table 4 displays a detailed overview of the difficulties in administering EMDR to people with ID described in each study and the corresponding adaptations that therapists made to overcome these difficulties. The numbers of mentioned difficulties and adaptations vary between studies and seem to be partly related to the specific EMDR protocols that were used. Notably, in papers referring to EMDR with the Shapiro adult protocol (2001) (16, 18, 38, 54, 55), relatively more detailed difficulties and adaptations were described than in publications referring to EMDR with a version of the child’s EMDR protocol (35–37, 56–59). The publication by Unwin et al. introduces a significant modification to the EMDR protocol; the addition of a phase called psycho-education and emotional stabilization (PES) (25).

Table 4. Identified difficulties and corresponding adaptations in EMDR for people with ID per included Study.

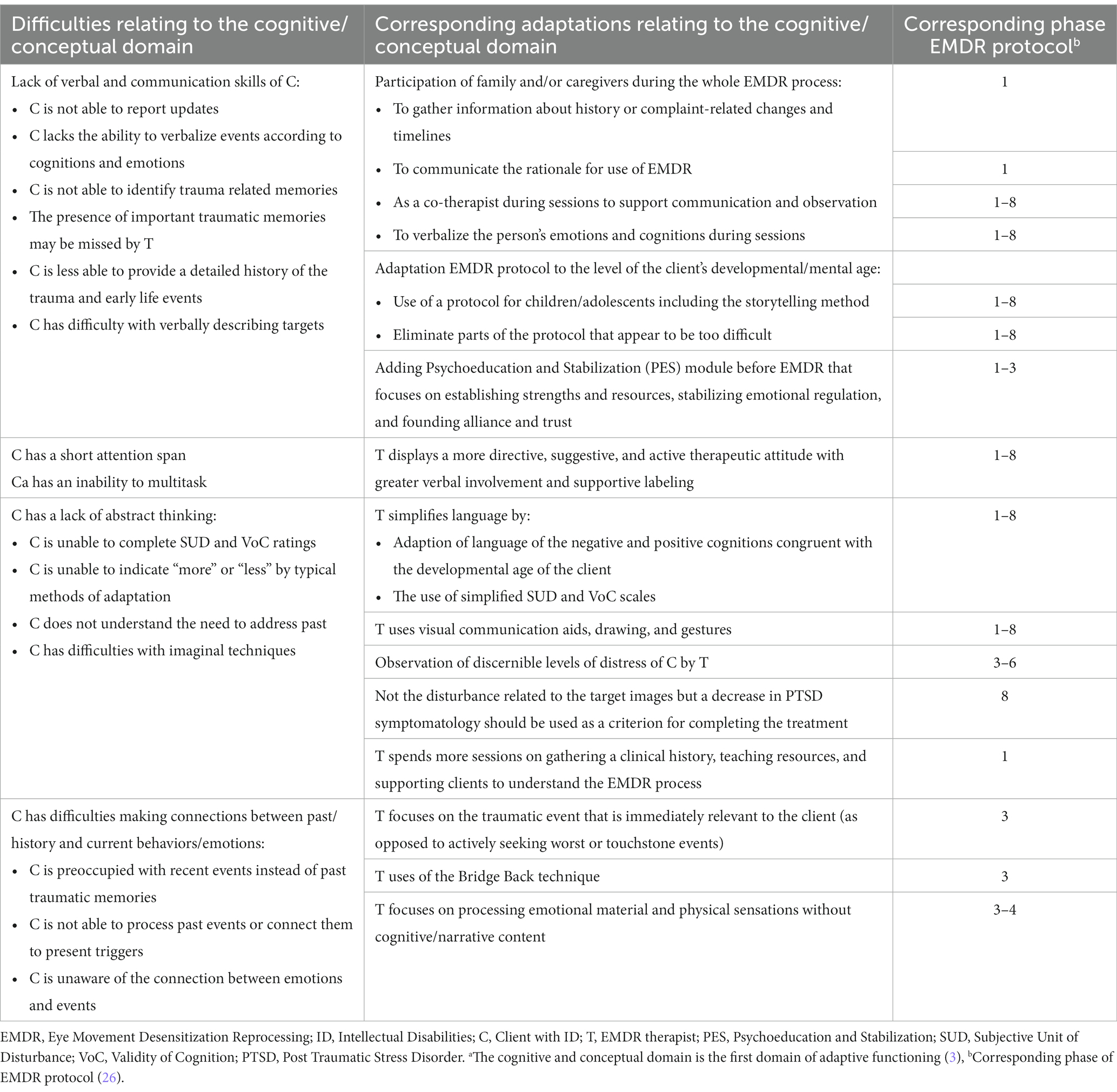

In the following analyses, the first author (SS) categorized the difficulties and adaptations described in Table 4 into the three domains of adaptive functioning (3): the cognitive/conceptual, social, and practical domains (Tables 5–7, respectively). Subsequently, the difficulties and adaptations were classified by the first and third author (SS and LM) into the corresponding phase in the EMDR process (26). In the cognitive/conceptual domain (Table 5), the identified difficulties that may hinder EMDR therapy for people with ID include a lack of verbal and communication skills; a short attention span; an inability to multitask; a lack of abstract thinking, and difficulties in making connections between past and current behaviors. To overcome these difficulties, the parts of the protocol that appear to be too difficult for these reasons, are eliminated (18, 36, 57). In addition, a protocol for EMDR with children and adolescents is often used, which is adapted to the client’s developmental age level (35–37, 50, 59). This includes the ‘storytelling method’ developed by Lovett for applying EMDR to children under 3, where parents/caregivers narrate the traumatic event (58). Other adaptations in this domain include the use of simplified language and materials, and/or focusing on emotional material and physical sensations without cognitive/narrative content (18, 38, 54, 55). Furthermore, the EMDR therapist adapts his/her behavior by displaying a more directive attitude and greater verbal involvement (18, 54, 57). All the articles identified in this review highlight the significant role played by the support system, which includes family members and caregivers. They participate in the therapy sessions in various ways, such as providing information, verbalizing the person’s emotions and thoughts during the sessions, or acting as co-therapists to support communication. This adaptation seems crucial in this domain and is present in all the articles reviewed. All aforementioned adaptations in the cognitive/conceptual domain are applied during all phases of the EMDR protocol.

Table 5. Categorization of identified difficulties and corresponding adaptations in EMDR for people with ID relating to the cognitive and conceptual domain.a

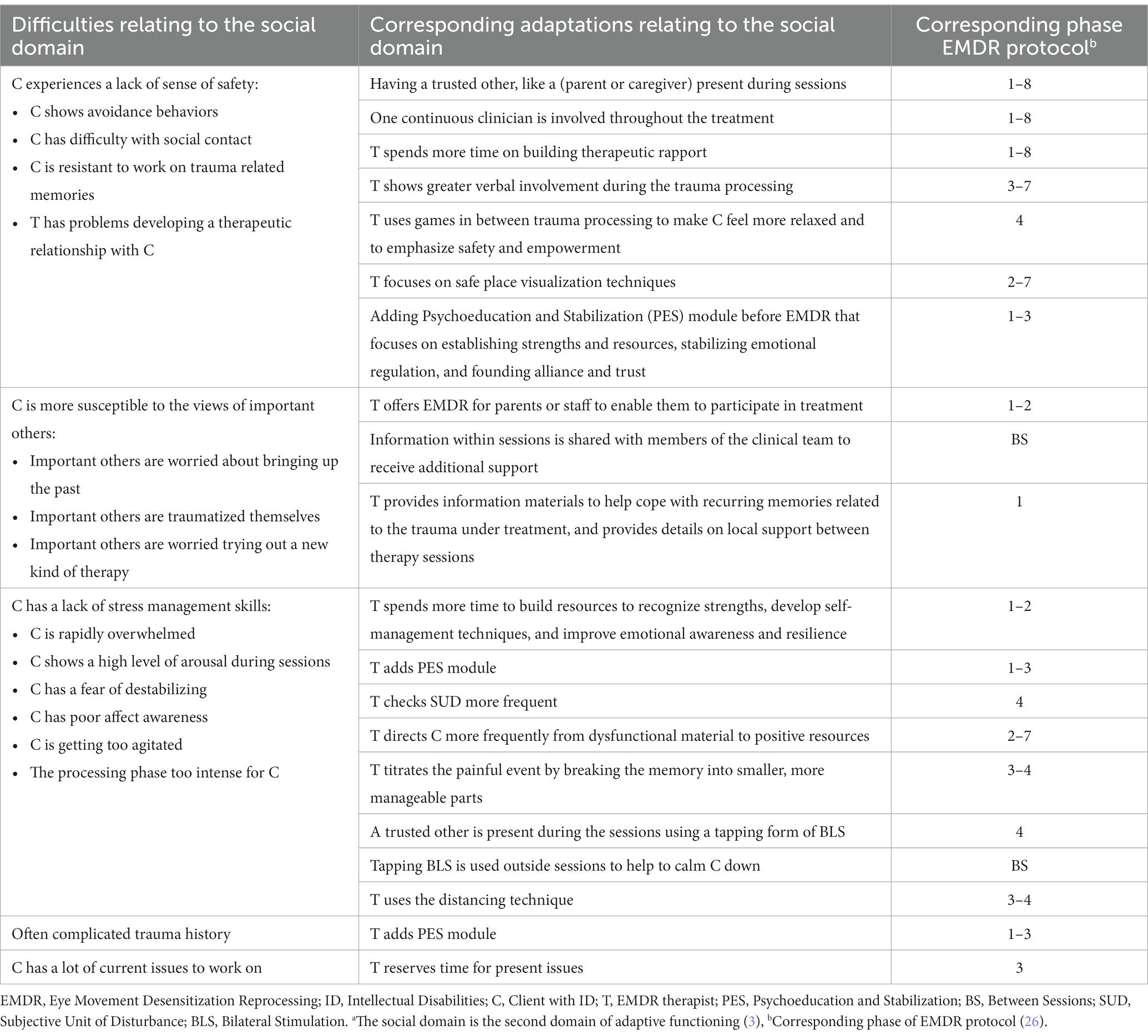

Table 6. Categorization of identified difficulties and corresponding adaptations in EMDR for people with ID relating to the social domaina.

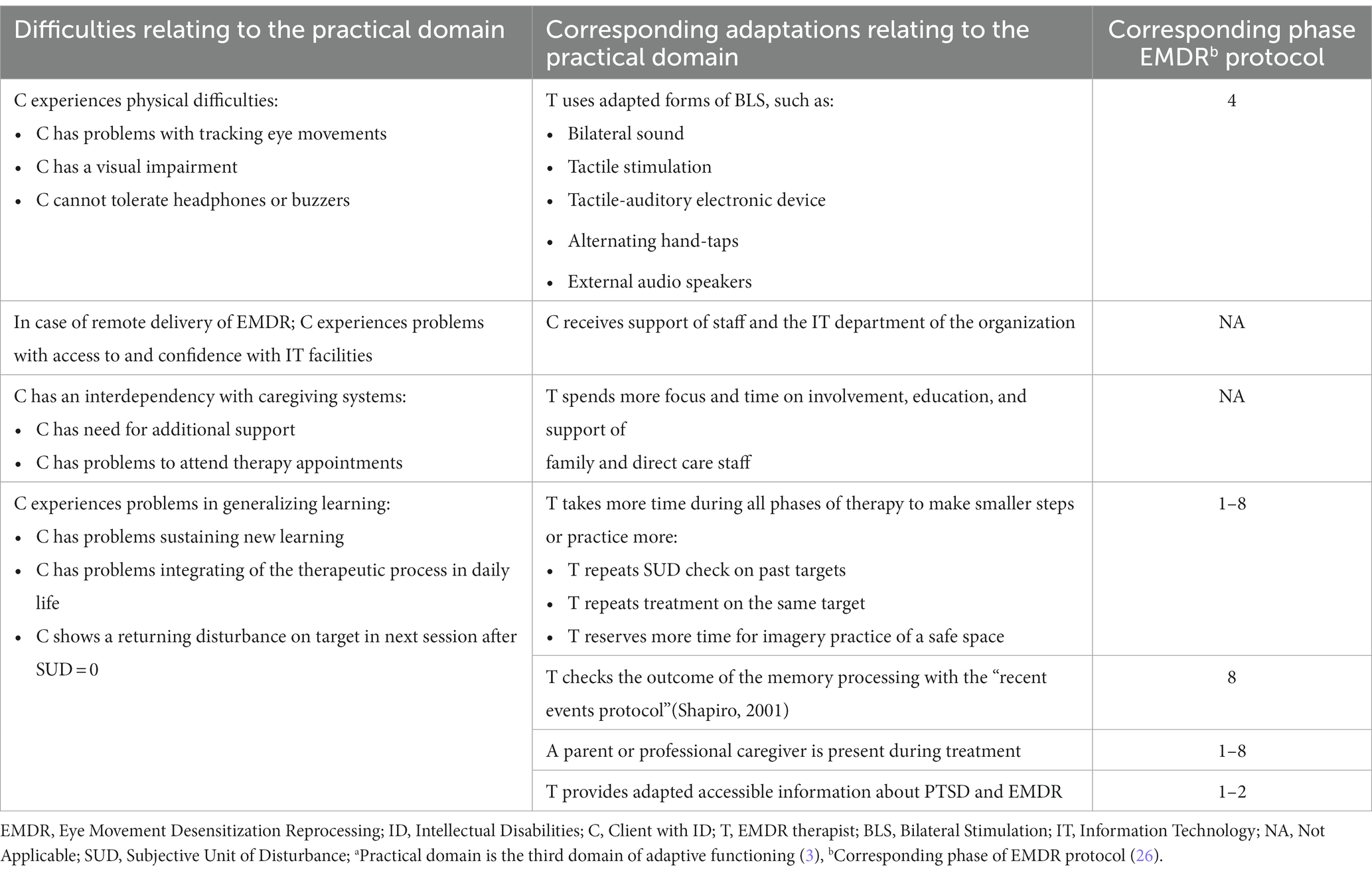

Table 7. Categorization of identified difficulties and corresponding adaptations in EMDR for people with ID relating to the practical domaina.

The social domain (Table 6) includes patient difficulties with feeling safe and/or developing social contact, which hinders the formation of a therapeutic relationship needed for engaging in EMDR. Regarding this domain, some authors (16, 18, 25, 38, 54, 55) also mention a lack of stress management skills, causing the person with ID to feel agitated or overwhelmed during the EMDR process. Furthermore, high susceptibility to the views of others and complex trauma histories are put forward as difficulties (16, 25). Many adaptations to cope with the difficulties in this domain also are identified, for all phases of the EMDR protocol. Examples are: having the accompany of a trusted other to give support during, and in between sessions; and taking more time to build the therapeutic relationship. Also, therapists employ greater verbal involvement, focus on positive resources, and teach affect management and self-soothing skills. In addition, EMDR was sometimes administered to parents who were traumatized themselves, enabling them to participate in treatment (58). The publication by Unwin et al. introduces a PES phase, which aims to build a strong alliance and trust between the client and therapist, stabilize emotional regulation, and install strengths and resources in the client (25).

Regarding the practical domain (Table 7), EMDR therapy for people with ID can be challenging due to physical impairments like visual or hearing deficiencies, or muscular problems. However, these challenges are overcome by using alternative forms of bilateral stimulation like tactile stimuli such as hand taps or buzzers or auditory ones such as sounds and headphones that suit the specific needs of the person (18, 38, 54, 57, 58). Another difficulty faced by individuals with ID in the practical domain is their struggle with generalizing learned skills from EMDR therapy to daily life. This is resolved by taking more time during all phases of EMDR therapy to enable smaller steps or to practice more (18, 57). Another challenge in the practical domain is the interdependence of individuals with ID and their caregiving systems. For instance, they may require extra assistance between EMDR therapy sessions or be unable to attend therapy appointments unaccompanied. Therefore, it is crucial to involve, educate, and support family members and direct care staff throughout all phases of EMDR therapy (16, 18, 25, 38, 55).

In conclusion, our findings revealed a wide range of adaptations that correspond to the three domains of adaptive functioning (3). These adaptations, which are presented in Tables 5–7, can be broadly categorized into three main groups: adaptations in EMDR delivery, adaptations in the engagement of others, and adaptations in the therapeutic relationship. Adaptations in EMDR delivery involve modifying the protocol to suit clients’ developmental levels, adjusting materials, adding or omitting certain elements, simplifying language, and adapting the pace of the sessions. Similarly, adaptations in the engagement of others include involving family members or support staff to facilitate communication and provide support during and between sessions or as a source of information. Finally, adaptations in the therapeutic relationship comprise elements such as taking more time to establish therapeutic rapport, increased verbal interaction, or a more supportive attitude from the therapist.

Discussion

The current review aimed to systematically identify and categorize the difficulties described in the literature in applying EMDR to people with ID as well as adaptations made to overcome these challenges. Though findings suggest the potential effectiveness of EMDR with individuals with ID and PTSD, (23, 60) considerable difficulties in applying the EMDR protocol for this group are reported, corresponding to the three domains of limited adaptive functioning (3). The adaptations made by therapists to overcome these difficulties are highly variable and can be divided into three main categories: adaptations in EMDR delivery, in the engagement of others, and adaptations in the therapeutic relationship.

It appears that the number of difficulties and adaptations mentioned per study may be partly linked to the specific EMDR protocol utilized. In particular, when the Shapiro adult protocol (27) was administered, relatively more detailed difficulties and adaptations were described than in publications based on a version of the EMDR protocol for children (50). A probable explanation is that modifications are already embedded in these child protocols tailoring to the clients’ level of functioning, which for people with ID will not reach above a developmental level of 12 years. It is also possible that the high variability in difficulties and adaptations found between studies can be attributed to the diverse and variable nature of the group of people with ID. This variation implies that individuals with ID will have a broad range of abilities, needs, and challenges, which depend on the severity of their disability, social and communication skills, and level of attachment difficulties (22). Given this wide variability, EMDR therapy needs to be flexible and adapted to the individual’s unique characteristics and circumstances. Additionally, people with ID often experience interpersonal and/or complex trauma (10, 11), which may require modifications or additions to the EMDR protocol. For instance, it can be necessary to spend more time building therapeutic rapport and resources or to include a complete PES phase (18, 25). This concept of an extended EMDR treatment model is also demonstrated in the intensive inpatient trauma treatment program for families; KINGS ID (61).

The findings of our research align with the adaptations for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for individuals with ID as described by Dagnan et al. (62). The authors emphasize the importance of customizing CBT techniques to suit the specific needs of this group. This includes using activities instead of verbal interactions, simplifying processes, involving caregivers, adapting to the developmental level of the individual with ID, modifying language, being flexible, and using directive methods. The authors also highlight the significance of establishing a strong therapeutic alliance through rapport-building and communication strategies that are tailored to the individual’s cognitive abilities (62).

Limitations

Regardless of our efforts to conduct this review systematically and rigorously, some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. First, our focus had been on qualitative analysis and categorization of difficulties and adaptations of EMDR for people with ID, hindering a more quantitative comparison with findings from other studies such as Dagnan et al. (62). Second, the high variability of the design and population characteristics of the reviewed studies interferes with the generalizability of results. Depending on the severity of ID or the type of experienced trauma, some of the identified adaptations may be more applicable. On the other hand, this variability could also be considered a strength since this has led to a high number of identified difficulties and adaptations. Third, information was not constantly reported across the studies. Some studies did not provide detailed information regarding the level of training and experience of therapists using EMDR with individuals with ID, which may have influenced the reported difficulties. Additionally, some studies did not describe the EMDR protocol used in detail, making it harder to identify any adaptations. Moreover, many articles did not specify the exact number or duration of EMDR sessions, making it more challenging to identify possible adaptations in this area.

Implications

From a clinical perspective, an EMDR child protocol [e.g., the EMDR protocol for children and adolescents (50)] seems to provide the best base for EMDR treatment of people with ID, because it encompasses a considerable amount of the identified adaptations and it is adjusted to these clients level of functioning. It is crucial that therapists have sufficient training and experience in both administering the EMDR protocol and in working with individuals with ID. Concerning EMDR delivery, the studies included in this review provide detailed descriptions of adaptations of the EMDR protocol. It is advisable to conduct further research to determine the most suitable adaptations, taking into account various subgroups defined by factors such as the severity of ID, physical limitations, and verbal capabilities (23). Focusing on the second category, the engagement of others, all studies described family or support staff as (more or less) active participants in the treatment. Involving family and/or support staff in the therapeutic process to provide comfort, support communication, and promote generalization of skills, seems a fundamental condition for an effective enrolment of individuals with ID in (EMDR) therapy (17, 62). The specific role of the family member or support staff, however, has not been explicitly defined in all studies. It seems important to clearly communicate the role of trusted others in EMDR sessions since their involvement can greatly influence the process. Also, there are often practical challenges in the continuity of carers, which makes it difficult for the same trusted other to be consistently present throughout therapy (21, 61). Finally, insight gained by the family member or support staff involved in the treatment could be an alternative explanation for the improvements reported (39). It is advisable to explore how trusted individuals can best contribute to each phase of the EMDR process and the amount of input they provide. Subsequently, the third category, the adaptations in the therapeutic relationship, might form the biggest challenge. It appears that there is currently a lack of explicit description of the therapeutic relationship required for EMDR therapy in research (63). According to Hase and Brisch, the therapeutic alliance should be described as an essential part of EMDR therapy. Since attachment theory offers a view on the development of interpersonal relationships in general, from their perspective, an attachment-based perspective of the therapeutic relationship required for EMDR would be desirable (63). This would be of even more importance for people with ID, especially those who struggle with attachment difficulties or complex or interpersonal trauma (21, 22, 64). A clear description of the necessary components of the therapeutic relationship in terms of speech, rhythm, eye contact, touch, and attunement of the therapist to the individual, could be a useful addition to the EMDR protocol for this specific group. Gentle Teaching (65), an attachment and relationship-based approach that focuses on building safe and loving alliances with people with ID, might be promising in pursuit of this objective. It could be worthwhile to incorporate elements of Gentle Teaching in the EMDR protocol to increase the accessibility and effectiveness of EMDR therapy for this group.

Conclusion

The findings of this review show that, although research underlines the potential effectiveness of EMDR for individuals with ID and PTSD, applying the EMDR protocol to this population presents therapists with considerable difficulties in all three domains of these clients’ adaptive functioning. Adaptations in EMDR delivery, in the engagement of others, and in the therapeutic relationship are often required. Difficulties in EMDR delivery could largely be addressed by adaptations that are incorporated into EMDR protocols for children and adolescents. It is recommended to focus further research on how to involve trusted others in EMDR therapy for people with ID and on how to establish a therapeutic relationship from an attachment and relational-based perspective.

Author contributions

SS-E: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. RV: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Prinsenstiching, an organization that provides support and treatment for people with intellectual disabilities in the Netherlands, employer of the first and second author.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1328310/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Mevissen, L, Didden, R, and de Jongh, A. Assessment and treatment of PTSD in people with intellectual disabilities In: CR Martin, VR Preedy, and VB Patel, editors. Comprehensive guide to post-traumatic stress disorders. Switzerland: Springer. (2016). 281–99.

2. Didden, R, and Mevissen, L. Trauma in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: introduction to the special issue. Res Dev Disabil. (2022) 120:104122. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104122

3. American Psychiatric Association . Intellectual disability (intellectual developmental disorder). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fifth ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

4. Jonker, F, Didden, R, Goedhard, L, Korzilius, H, and Nijman, H. The ADaptive ability performance test (ADAPT): a new instrument for measuring adaptive skills in people with intellectual disabilities and borderline intellectual functioning. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2021) 34:1156–65. doi: 10.1111/jar.12876

5. Pepperdine, CR, and McCrimmon, AW. Test review: Vineland adaptive behavior scales, Third Edition by S. S. Sparrow, D. V. Cicchetti, and C. A Saulnier. Can J Sch Psychol (2017);33:157–163, doi: 10.1177/0829573517733845

6. de Vries, GJ, and Olff, M. The lifetime prevalence of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands. J Trauma Stress. (2009) 22:259–67. doi: 10.1002/jts.20429

7. Kessler, RC, Chiu, WT, Demler, O, and Walters, EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2005) 62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

8. Nieuwenhuis, JG, Smits, H, Noorthoorn, E, Mulder, CL, Maria Penterman, E, and Inge, NH. Not recognized enough: the effects and associations of trauma and intellectual disability in severely mentally ill outpatients. Eur Psychiatry. (2019) 58:63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.02.002

9. Mevissen, L, Didden, R, de Jongh, A, and Korzilius, H. Assessing posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with mild intellectual disabilities or borderline intellectual functioning. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. (2020) 13:110–26. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2020.1753267

10. Rittmannsberger, D, Weber, G, and Lueger-Schuster, B. Applicability of the post-traumatic stress disorder gate criterion in people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities: do additional adverse events impact current symptoms of PTSD in people with intellectual disabilities? J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2020) 33:1100–12. doi: 10.1111/jar.12732

11. Wigham, S, and Emerson, E. Trauma and life events in adults with intellectual disability. Curr Dev Disord Rep. (2015) 2:93–9. doi: 10.1007/s40474-015-0041-y

12. Brewin, CR, Andrews, B, and Valentine, JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2000) 68:748–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.748

13. Munir, KM . The co-occurrence of mental disorders in children and adolescents with intellectual disability/intellectual developmental disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2016) 29:95–102. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000236

14. Zohar, J, Fostick, L, Cohen, A, Bleich, A, Dolfin, D, Weissman, Z, et al. Risk factors for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder following combat trauma: a semiprospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. (2009) 70:1629–35. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04378blu

15. Mevissen, L, and de Jongh, A. PTSD and its treatment in people with intellectual disabilities: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. (2010) 30:308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.005

16. Unwin, G, Willott, S, Hendrickson, S, and Stenfert, KB. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for adults with intellectual disabilities: process issues from an acceptability study. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2019) 32:635–47. doi: 10.1111/jar.12557

17. Keesler, JM . Trauma-specific treatment for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a review of the literature from 2008 to 2018. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. (2020) 17:332–45. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12347

18. Barol, BI, and Seubert, A. Stepping stones: EMDR treatment of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and challenging behavior. J EMDR Prac Res. (2010) 4:156–69. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.4.4.156

19. Scott, K, Hatton, C, Knight, R, Singer, K, Knowles, D, Dagnan, D, et al. Supporting people with intellectual disabilities in psychological therapies for depression: a qualitative analysis of supporters' experiences. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2019) 32:323–35. doi: 10.1111/jar.12529

20. Fletcher, R, Barnhill, J, and Cooper, SA. Diagnostic manual intellectual disability 2: A textbook of diagnosis of mental disorders in persons with intellectual disability: New York. NY: NADD Press (2016).

21. Dagnan, D, Jahoda, A, and Kildahl, AN. Preparing people with intellectual disabilities for psychological treatment In: JL Taylor, WR Lindsay, R Hastings, and C Hatton, editors. Psychological therapies for adults with intellectual disabilities. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell (2013)

22. Hamadi, L, and Fletcher, HK. Are people with an intellectual disability at increased risk of attachment difficulties? A critical review. J Intellect Disabil. (2021) 25:114–30. doi: 10.1177/1744629519864772

23. Smith, AN, Laugharne, R, Oak, K, and Shankar, R. Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing therapy for people with intellectual disability in the treatment of emotional trauma and post traumatic stress disorder: a scoping review. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. (2021) 14:237–84. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2021.1929596

24. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE guideline NG116). (2018). Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

25. Unwin, G, Stenfert-Kroese, B, Rogers, G, Swain, S, Hiles, S, Clifford, C, et al. Some observations on remote delivery of eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing to people with intellectual disabilities. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. (2023) 20:205–15. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12452

26. Shapiro, F . Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, third edition: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Publications (2017).

27. Shapiro, F . Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press (2001).

28. Greenwald, R . Eye movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Lanham: Jason Aronson (1999).

29. Civilotti, C, Margola, D, Zaccagnino, M, Cussino, M, Callerame, C, Vicini, A, et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in child and adolescent psychology: a narrative review. Curr Treat Options Psych. (2021) 8:95–109. doi: 10.1007/s40501-021-00244-0

30. Chen, L, Zhang, G, Hu, M, and Liang, X. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2015) 203:443–51. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000306

31. Moreno-Alcazar, A, Radua, J, Landin-Romero, R, Blanco, L, Madre, M, Reinares, M, et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy versus supportive therapy in affective relapse prevention in bipolar patients with a history of trauma: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2017) 18:160. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1910-y

32. Novo Navarro, P, Landin-Romero, R, Guardiola-Wanden-Berghe, R, Moreno-Alcázar, A, Valiente-Gómez, A, Lupo, W, et al. 25 years of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): the EMDR therapy protocol, hypotheses of its mechanism of action and a systematic review of its efficacy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. (2018) 11:101–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2015.12.002

33. Manzoni, M, Fernandez, I, Bertella, S, Tizzoni, F, Gazzola, E, Molteni, M, et al. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: the state of the art of efficacy in children and adolescent with post traumatic stress disorder. J Affect Disord. (2021) 282:340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.088

34. Jowett, S, Karatzias, T, Brown, M, Grieve, A, Paterson, D, and Walley, R. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults with intellectual disabilities: a case study review. Psychol Trauma. (2016) 8:709–19. doi: 10.1037/tra0000101

35. Mevissen, L, Didden, R, Korzilius, H, and de Jongh, A. Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in a child and an adolescent with mild to borderline intellectual disability: a multiple baseline across subjects study. J App Res Intel Disab: JARID. (2017) 30:34–41. doi: 10.1111/jar.12335

36. Penninx Quevedo, R, de Jongh, A, Bouwmeester, S, and Didden, R. EMDR therapy for PTSD symptoms in patients with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning and comorbid psychotic disorder: a case series. Res Dev Disabil. (2021) 117:104044. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104044

37. Verhagen, I, van der Heijden, R, de Jongh, A, Korzilius, H, Mevissen, L, and Didden, R. Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of emdr therapy in adults with ptsd and mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning and mental health problems: a multiple baseline study. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. (2023) 16:291–313. doi: 10.1080/19315864.2022.2148791

38. Karatzias, T, Brown, M, Taggart, L, Truesdale, M, Sirisena, C, Walley, R, et al. A mixed-methods, randomized controlled feasibility trial of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) plus standard care (SC) versus SC alone for DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2019) 32:806–18. doi: 10.1111/jar.12570

39. Gilderthorp, RC . Is EMDR an effective treatment for people diagnosed with both intellectual disability and post-traumatic stress disorder? J Intellect Disabil. (2015) 19:58–68. doi: 10.1177/1744629514560638

40. Adams, Z, and Boyd, S. Ethical challenges in the treatment of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Ethics Behav. (2010) 20:407–18. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2010.521439

41. van Herwaarden, A, Schuiringa, H, van Nieuwenhuijzen, M, Orobio de Castro, B, Lochman, JE, and Matthys, W. Therapist alliance building behavior and treatment adherence for dutch children with mild intellectual disability or borderline intellectual functioning and externalizing problem behavior. Res Dev Disabil. (2022) 128:104296. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104296

42. Janssen, CG, Schuengel, C, and Stolk, J. Understanding challenging behaviour in people with severe and profound intellectual disability: a stress-attachment model. J Intellect Disabil Res. (2002) 46:445–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00430.x

43. Ramsden, S, Tickle, A, Dawson, DL, and Harris, S. Perceived barriers and facilitators to positive therapeutic change for people with intellectual disabilities: client, carer and clinical psychologist perspectives. J Intellect Disabil. (2016) 20:241–62. doi: 10.1177/1744629515612627

44. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

45. Otten, R, de Vries, R, and Schoonmade, L. Amsterdam efficient deduplication (AED) method (version 1): Zenodo (2019). Available at: https://zenodo.org/records/3582928

46. Bramer, WM, Giustini, D, de Jonge, GB, Holland, L, and Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. (2016) 104:240–3. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014

47. Munn, Z, Barker, TH, Moola, S, Tufanaru, C, Stern, C, McArthur, A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. (2020) 18:2127–33. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

48. de Jongh, A, and ten Broeke, E. Handboek EMDR: een geprotocolleerde behandelmethode voor de gevolgen van psychotrauma. 4th ed. Amsterdam: Pearson (2009).

50. de Roos, C, Beer, R, Jongh, A, and ten Broeke, E. EMDR protocol voor kinderen en jongeren tot 18 jaar. [EMDR protocol for children and youth until age 18 years]. Amsterdam: Pearson (2012).

51. Beer, R, and de Roos, C. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (emdr) bij kinderen en adolescenten. Kind en adolescent. (2004) 25:24–33. doi: 10.1007/BF03060901

52. Parnell, L . Attachment-focused EMDR: Healing relational trauma. New York, NY, US: W W Norton & Co (2013).

53. Hong, QN, Bartlett, G, Vedel, I, Pluye, P, Fabregues, S, Boardman, F, et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. (2018) 34:285–91. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

54. Barrowcliff, AL, and Evans, GAL. EMDR treatment for PTSD and intellectual disability: a case study. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. (2015) 9:90–8. doi: 10.1108/AMHID-09-2014-0034

55. Dilly, R . Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing in the treatment of trauma with mild intellectual disabilities: a case study. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. (2014) 8:63–71. doi: 10.1108/AMHID-06-2013-0036

56. Mevissen, L, Lievegoed, R, and de Jongh, A. EMDR treatment in people with mild ID and PTSD: 4 cases. Psychiatry Q. (2011) 82:43–57. doi: 10.1007/s11126-010-9147-x

57. Mevissen, L, Lievegoed, R, Seubert, A, and De Jongh, A. Do persons with intellectual disability and limited verbal capacities respond to trauma treatment? J Intellect Dev Disabil. (2011) 36:274–9. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2011.621415

58. Mevissen, L, Lievegoed, R, Seubert, A, and de Jongh, A. Treatment of PTSD in people with severe intellectual disabilities: a case series. Dev Neurorehabil. (2012) 15:223–32. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2011.654283

59. Rodenburg, R, Benjamin, A, Meijer, AM, and Jongeneel, R. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in an adolescent with epilepsy and mild intellectual disability. Epilepsy Behav. (2009) 16:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.07.015

60. McNally, P, Taggart, L, and Shevlin, M. Trauma experiences of people with an intellectual disability and their implications: a scoping review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. (2021) 34:927–49. doi: 10.1111/jar.12872

61. Mevissen, L, Ooms-Evers, M, Serra, M, de Jongh, A, and Didden, R. Feasibility and potential effectiveness of an intensive trauma-focused treatment programme for families with PTSD and mild intellectual disability. Eur J Psychotraumatol. (2020) 11:1777809. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1777809

62. Dagnan, D, Taylor, L, and Burke, C-K. Adapting cognitive behaviour therapy for people with intellectual disabilities: an overview for therapist working in mainstream or specialist services. Cog Behav Therapist. (2023) 16:e3. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X22000587

63. Hase, M, and Brisch, KH. The therapeutic relationship in EMDR therapy. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.835470

64. Taylor, JL, Lindsay, WR, Hastings, R, and Hatton, C. Psychological therapies for adults with intellectual disabilities. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons (2013).

Keywords: eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, EMDR, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, intellectual disabilities, ID, trauma

Citation: Schipper-Eindhoven SM, de Knegt NC, Mevissen L, van Loon J, de Vries R, Zhuniq M and Bekker MHJ (2024) EMDR treatment for people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review about difficulties and adaptations. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1328310. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1328310

Edited by:

Alisan Burak Yasar, Gelisim University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Dursun Hakan Delibaş, Izmir Bozyaka Training and Research Hospital, Türkiye Tayfun Öz, Ankara Etlik City Hospital, Türkiye Canan Citil Akyol, Cumhuriyet University, TürkiyeCopyright © 2024 Schipper-Eindhoven, de Knegt, Mevissen, van Loon, de Vries, Zhuniq and Bekker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simone M. Schipper-Eindhoven, c2kuc2NoaXBwZXJAcHJpbnNlbnN0aWNodGluZy5ubA==

Simone M. Schipper-Eindhoven

Simone M. Schipper-Eindhoven Nanda C. de Knegt1

Nanda C. de Knegt1 Ralph de Vries

Ralph de Vries Majlinda Zhuniq

Majlinda Zhuniq Marrie H. J. Bekker

Marrie H. J. Bekker