- 1Department of Mental Health, School of Medicine, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

- 2Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

- 3School of Medicine, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

- 4Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Introduction: In response to the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns about mental health, particularly anxiety levels, have become prominent. This study aims to explore the relationship between neuroticism, a personality trait associated with emotional instability, and anxiety during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted using the Cochrane Library, HINARI, Google Scholar, and PUBMED, resulting in the identification of 26 relevant papers. The study protocol has been registered with PROSPERO under the number CRD42023452418. Thorough meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V4 software.

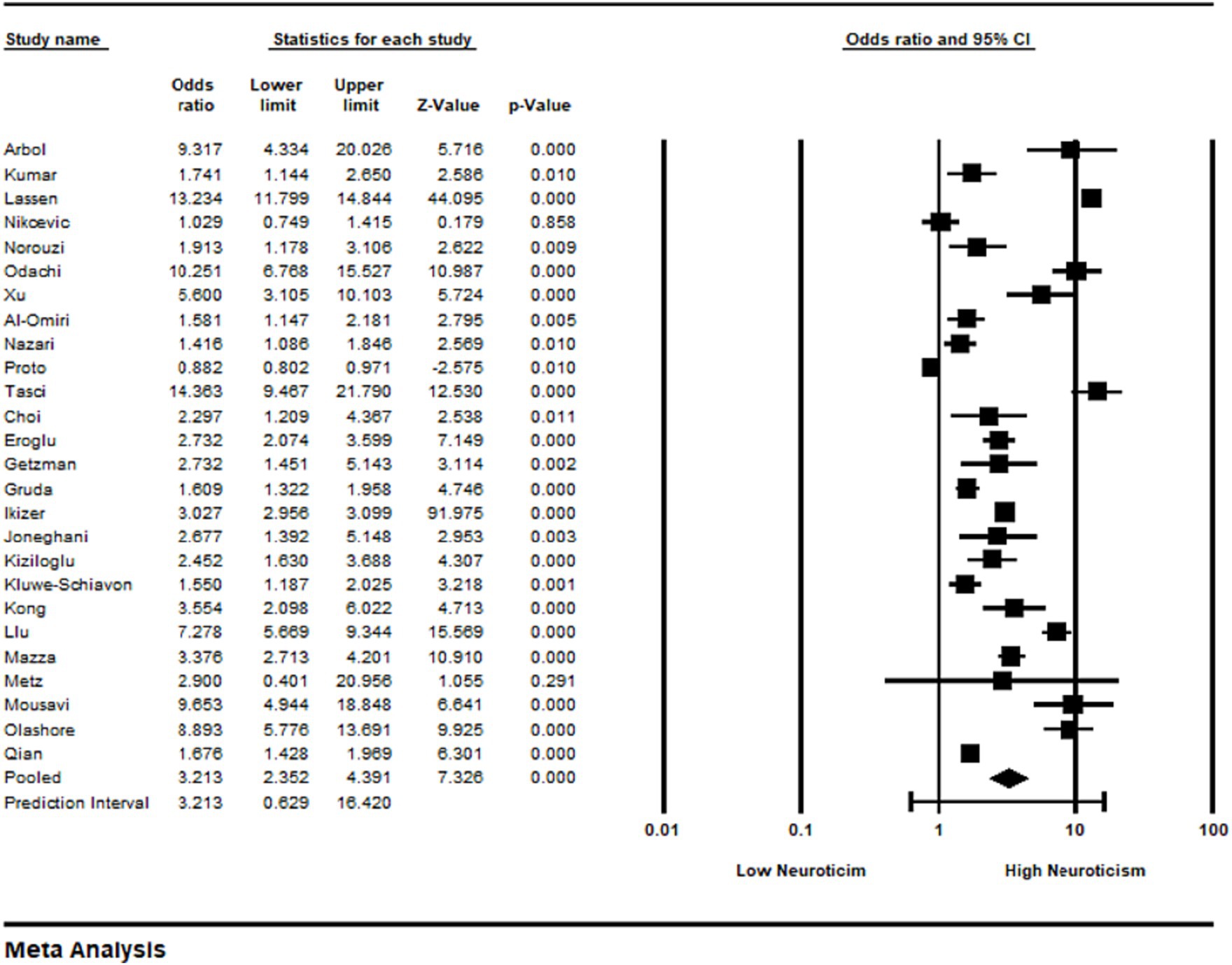

Results: Meta-analysis revealed a significant positive relationship between anxiety and neuroticism, with 26 studies supporting this association (OR = 3.213, 95% CI 2.352 to 4.391). The findings underscore the importance of considering personality traits, particularly neuroticism, in understanding psychological responses to major global crises such as the COVID-19 epidemic.

Discussion: The observed connection between neuroticism and heightened anxiety levels emphasizes the need for targeted interventions, especially for individuals with high levels of neuroticism. Further research into potential therapeutic approaches for mitigating anxiety consequences in the context of a significant global catastrophe is warranted.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#CRD42023452418.

1 Introduction

Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have provided estimations of the prevalence of mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (1–6). Several key concerns emerge from the available studies. Firstly, there is substantial increase in global anxiety prevalence post-COVID-19, affecting a considerable number of individuals, with a prevalence of 35.1% (7). This increased prevalence is consistent across low and middle-income countries to high-income countries (2). Secondly, systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that cognitive-behavioral therapy, training, and physical exercise interventions prove notably effective in addressing anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (8, 9). Lastly, the relationship between mindfulness as a trait and its associations with the Big Five personality traits and anxiety are explored (9–12). However, the synthesis of these relationships is not yet thoroughly examined in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Big-Five model is the most widely accepted model of personality. Five personality qualities are included: extraversion (to be sociable and active), agreeability (to be kind and trusting), conscientiousness (to be meticulous and dependable), emotional stability (to be at ease and peaceful), and openness (to be creative and curious) are the five personality traits (13). The most used tools on personal traits are Big Five Personality Traits and Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (14–32). Among the four types of personal traits, neuroticism and anxiety are significantly connected (14–44). People with high levels of neuroticism may be more prone to excessive worry and ruminating because they are more sensitive to threat indicators. It’s possible that neuroticism has a significant impact in shaping people’s anxiety responses given the pandemic’s inherent challenges and uncertainties (45). Several observational studies have investigated the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic (26, 29, 31, 38, 46, 47). In addition to that, while a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis explored the psychometric properties and psychological correlates of the COVID-19 anxiety syndrome scale on a broader scale (48), there is currently no systematic review specifically addressing the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety during COVID-19.

The current work seeks to fill this gap by undertaking a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 epidemic. This study tries to improve our understanding of the intricate interplay between personality traits and psychological reactions during times of crisis by combining the current empirical information. Furthermore, the findings of this study have significance for both clinical practice and public health initiatives, providing insights that can inform targeted strategies to support those who are especially sensitive to heightened anxiety during the pandemic.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources and search strategy

To find relevant publications published between January 2020 and September 2023, a comprehensive literature search was done across key electronic databases such as MEDLINE (via PubMed), HINARI for access to research articles in developing nations and Google Scholar. Research protocol has been registered through protocol number CRD42023452418.

Search strategy: (“COVID-19” OR “coronavirus” OR “SARS-CoV-2”) AND (“anxiety” OR “stress” OR “psychological distress” OR “mental health”) AND (“personality traits” OR “neuroticism” OR “extraversion” OR “openness” OR “agreeableness” OR “conscientiousness”).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies considered in the systematic review satisfied following exposure-related inclusion requirements:

• Studies that measure exposure to neuroticism using standardized scales or questionnaires, such as the Big Five Inventory (BFI) or the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), are known as exposure studies. Known tools for measuring anxiety include the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) scale.

• Population: research on people who are affected by the COVID-19 epidemic, regardless of their age, gender, socioeconomic status, or location.

Studies that do not match the inclusion criteria or those that fall under the following categories was excluded:

• Studies that did not primarily examine the connection between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 epidemic were irrelevant in emphasis.

• Studies with insufficient data on measures of neuroticism and anxiety or those lacking the requisite statistical data are said to have incomplete data.

• Non-human studies: research involving animals or purely computer simulations or model systems.

• Articles, abstracts, conference proceedings, opinions, editorials, and non-systematic reviews that have not been peer-reviewed are considered non-peer-reviewed.

• Studies published in languages other than English due to a lack of resources for language translation.

• Research that was done before the COVID-19 pandemic.

• Duplicate data: to ensure data independence, studies having duplicate data from the same population and time was eliminated.

• Reviews, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews will be disqualified as non-original research. Only original research studies were considered.

2.2.1 Extraction of data

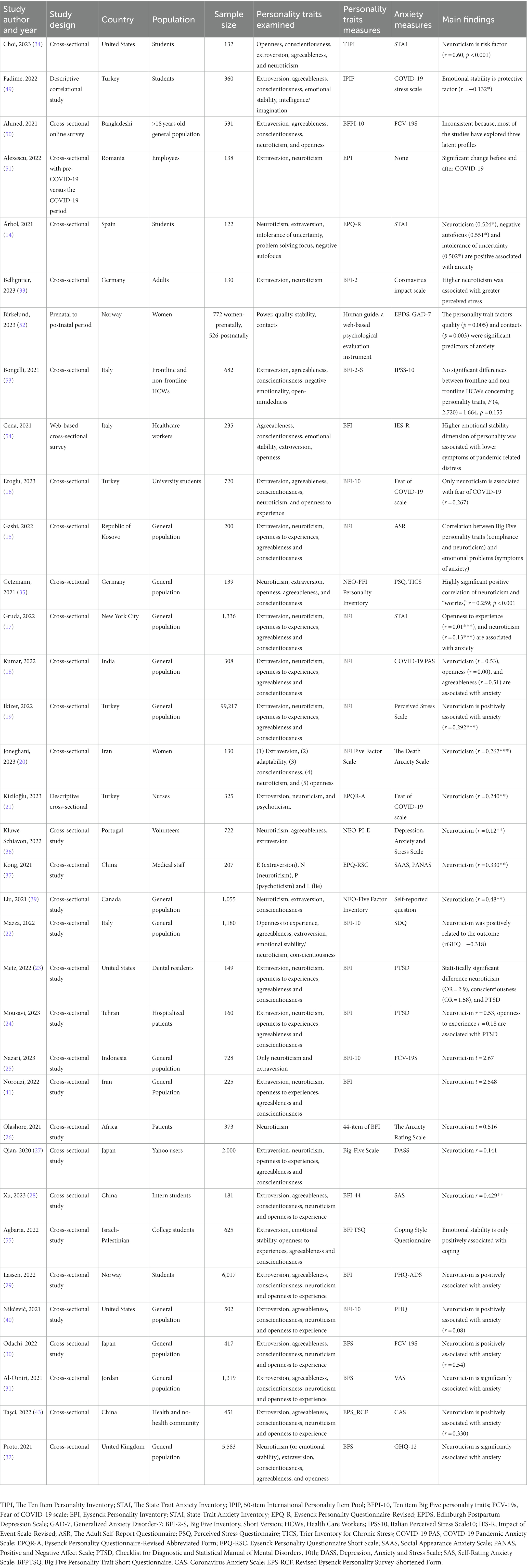

Following authors (ER*, MG, KZ, MS, and ST) retrieved pertinent data from the selected papers in a methodical manner, including study characteristics, sample size, methodology, and major conclusion which is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Studies included in the systematic review relationship between personality traits and anxiety during COVID-19.

2.3 Data analysis

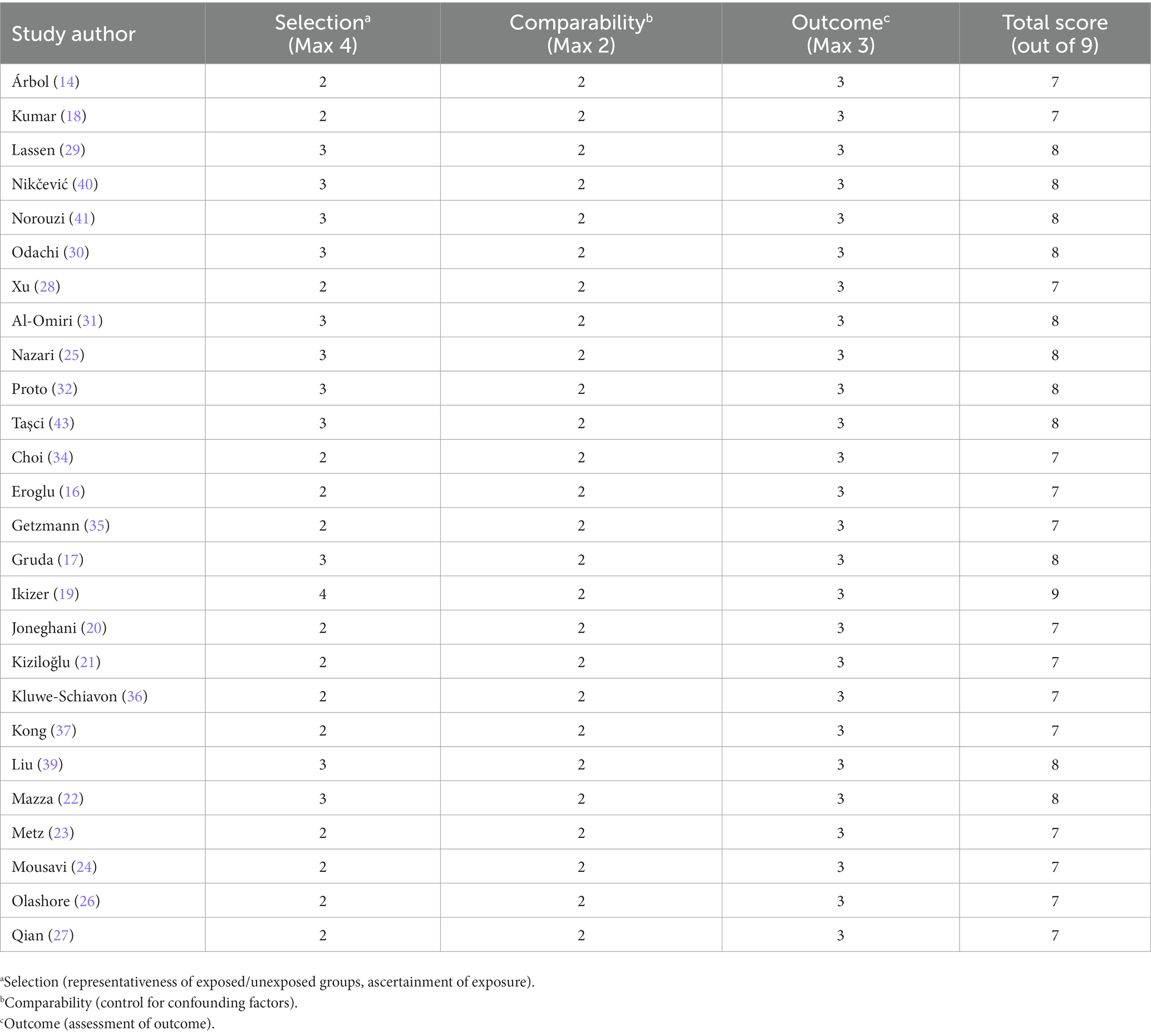

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to assess the quality and risk of bias of the included studies which was shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Quality assessment using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality and risk of bias of the included studies.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

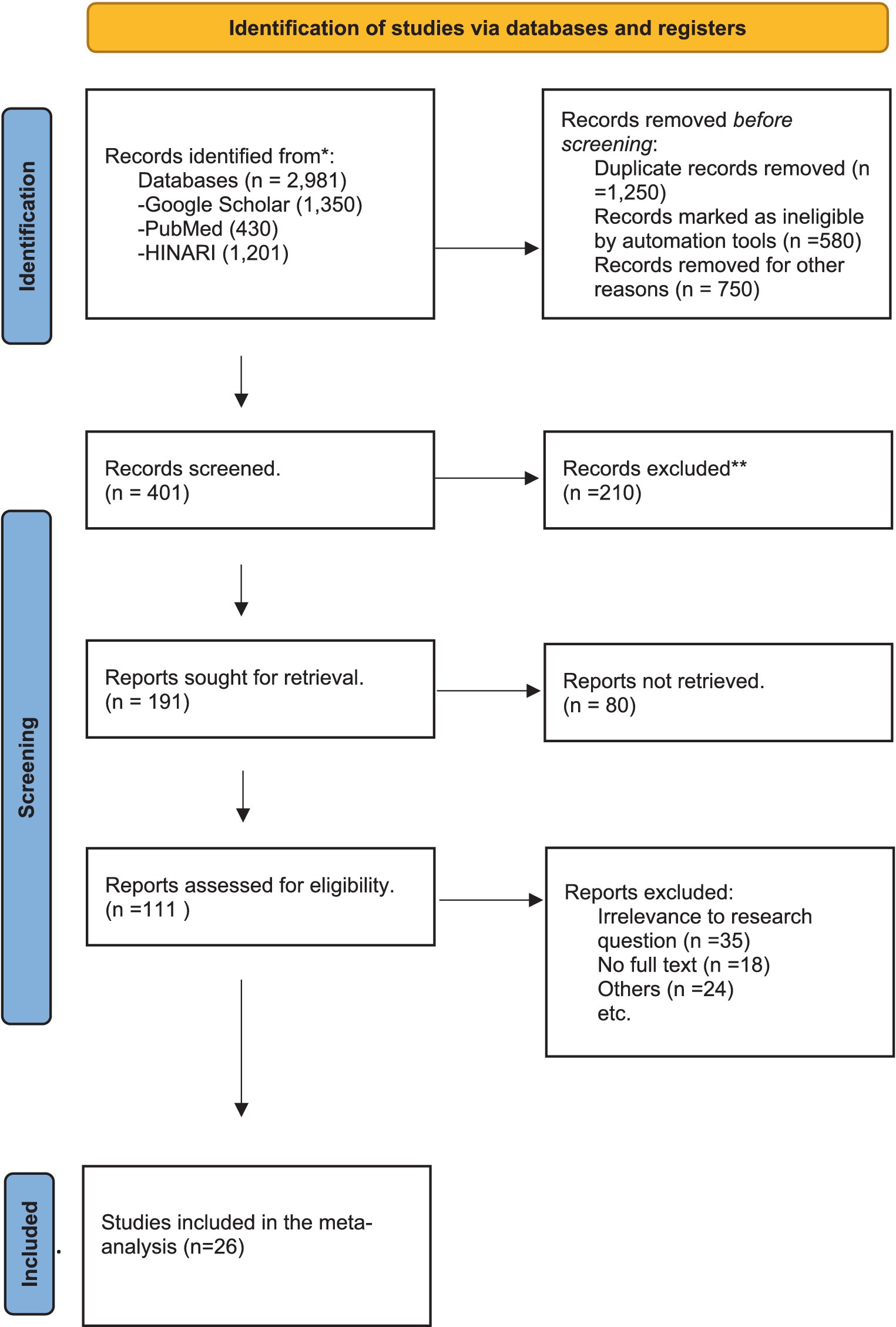

The procedure for a systematic review is shown in Figure 1. Five thousand nine hundred sixty-two documents were first found across several databases. Two thousand nine hundred eighty-one of them came from PubMed and Hinari, and 1,350 from Google Scholar when appropriate keywords were used. One thousand two hundred fifty duplicate records were eliminated, and then automation was used to mark 580 records as invalid. A further 750 records were excluded for factors other than duplication or eligibility. Four hundred one records underwent screening, with titles and abstracts being examined for appropriateness.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram used for this systematic reviews which included searches of articles (56).

Two hundred ten of these data were left out because they did not suit the study’s parameters or subject. One hundred ninety-one records from the screened records were chosen for further analysis. Eighty retrievals were made, but none were successful, probably owing to access restrictions. One hundred eleven of the collected papers underwent an extensive eligibility review. Of these, 24 were removed for predetermined reasons, such as methodological difficulties, and 24 were deemed irrelevant, 18 did not have full-text access.

Ultimately, 26 eligible papers were picked for the meta-analysis following thorough examination. The Newcastle–Ottawa risk of bias evaluation determined that these studies satisfied its requirements. This procedure makes sure that the final choice is trustworthy and pertinent to the goal of the investigation.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. The studies were conducted between 2020–2023 and encompassed 36 geographical regions such as United States, Turkey, Bangladesh, Romania, Spain, Germany, Norway, Italy, Republic of Kosovo, New York City (United States), India, Isfahan (Iran), Portugal, China, Canada, Tehran (Iran), Indonesia, Iran, Africa, Japan, Israeli-Palestinian, Norway, United States, Jordan, United Kingdom, and China with sample sizes ranging from min 130 to 99,217 max sample size. Most studies employed a cross-sectional study design, and the populations under investigation included list populations, along with students, people over the age of 18 in the general population, employees, adults, women, frontline and non-frontline healthcare workers, nurses, volunteers, medical staff, dental residents, hospitalized patients, Yahoo users, intern students, and college students. The outcomes/exposures evaluated in these studies varied.

3.3 Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment results for individual studies are presented in Figure 2. Studies were evaluated for potential biases using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale is a frequently employed instrument for evaluating the caliber of non-randomized research in meta-analyses by study authors OR and NL. It assesses three key areas: exposure ascertainment, group comparability, and study group selection. Based on criteria within these domains, the scale provides stars to each study, allowing users to assess the inclusion of studies’ methodological quality and bias risk. Table 2 gives a thorough breakdown of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale quality evaluation performed for the included research, evaluating both the quality and risk of bias. The ratings are based on how well the selection (maximum score of 4) and comparability (maximum score of 2) and outcome assessment (maximum score of 3) criteria were evaluated. A number of notable studies, including Joneghani and Sajjaian (20), Árbol et al. (14), Kumar and Tankha (18), and Xu et al. (28), got a total score of 7, while others, such Ikizer et al. (10) received the highest total score of 9, indicating solid quality and minimal danger of bias. The three main criteria of the scale—selection, comparability, and outcome—are applied to assess the methodological merits and limitations of the studies, resulting in a more thorough comprehension of their validity and reliability in examining the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.4 Quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis)

A forest plot of the pooled effect estimates for anxiety is shown in Figure 2. The meta-analysis of 26 studies investigating anxiety revealed an odds ratio, 95% CI. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software has been used to analyze meta-analysis. Our meta-analysis used a random-effects model. The random-effects model was used because it assumes that variations in population, methodology, or other factors may cause the true impact magnitude to differ between studies. This method takes possible heterogeneity into consideration and is more conservative.

To evaluate heterogeneity among the included studies, we computed the I2 statistic. Significant heterogeneity was observed in the results [p < (0.0001), and I2 = (48%)].

The heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I2 statistic and was found to be heterogeneity value I2 = 48% indicating moderate heterogeneity. Figure 2 shows a forest plot with the combined effect size for the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety. An intensely positive association between anxiety and neuroticism was found by meta-analysis, which was supported by 26 number of research (OR = 3.213, 95% CI 2.352 to 4.391). The findings of the systematic review as shown in Figure 2 provide a thorough summary of the correlation coefficients and statistical parameters obtained from several studies evaluating the connection between personality characteristics and anxiety during the COVID-19 epidemic. Among other noteworthy results, Árbol’s et al. (14) study showed a substantial positive association (0.524) between neuroticism and anxiety among Spanish students. In a similar vein, Lassen’s research (29) on a sizable student sample shows a substantial correlation coefficient of 0.58 between particular personality qualities and anxiety. The study also emphasizes the importance of correlation coefficients in research like Xu’s et al. (28), where neuroticism and anxiety in intern students are reported to have a substantial association of 0.429. Similar findings are shown in Ikizer’s et al. (19) study, which shows that neuroticism and anxiety have a moderate connection (0.292) in a sizable general sample. Notably, odds ratios are introduced as pertinent indicators in Metz’s et al. (23) research. Together, the results of this systematic review help us gain a more nuanced understanding of the complex relationship that exists between personality traits and anxiety in the context of the difficulties brought on by the COVID-19 epidemic.

4 Discussion

Our meta-analysis has found that there is a positive relationship between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. This result is consistent with earlier theoretical models that contend there is a close connection between these two notions (14, 18, 20, 24, 25, 29–32, 34, 35, 40, 41, 44, 45). An extensive systematic review and meta-analysis, involving the examination of 17,789 individuals, demonstrated that anxiety was positively correlated with neuroticism, but inversely correlated with extraversion. This study is also limited by its study design and lacks information about the pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic period (48). However, 134 cohort including systematic review and meta-analysis showed that no changes were found for general mental health (57). The highest anxiety prevalence during COVID-19 was found among health care workers (6). Our systematic review did not focus on subgroup analysis. However, women displayed higher scores on anxiety during COVID-19 (47). Initially, our study wanted to subgroup analysis by lower and higher resource setting, but this study did not find any significant differences when we deal with anxiety during COVID-19 (26). Neuroticism is associated with emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those high in neuroticism tend to pay more attention to COVID-19 information and worry extensively about its consequences (crisis preoccupation) (38).

Personality traits were found to be correlated with the effects of COVID-19. The significance of the relationship between personality traits and COVID-19-related changes is illustrated by these results (31). Cross-sectional online survey, utilizing the German version of the COVID Stress Scales (CSS) and standard psychological questionnaires highlight neuroticism as a risk factor and extraversion as a protective factor influencing pandemic-related stress responses (58).

Although our research provides valuable insights into the correlation between neuroticism and anxiety amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to acknowledge its inherent limitations. When interpreting the results, it is crucial to consider these limitations, which also indicate potential areas for future research to improve:

• Study design and temporal data deficiency: the experimental nature of the study restricts our capacity to establish causation, as it merely provides associations rather than causal connections.

• Temporal limitations: the lack of data prior to and following the pandemic hinders the development of a comprehensive comprehension of the relationship between neuroticism and anxiety over an extended period. To overcome this constraint, longitudinal designs may be implemented.

• Disparity among research studies: the presence of substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 48%) suggests that there is considerable variation among the studies. Potential sources of variation include disparities in populations, approaches, or uncontrolled variables, all of which may influence the dependability of the aggregate effect estimates.

• Analysis of subgroups and resource configurations: the research did not conduct an in-depth examination of subgroup dynamics, such as variations in resources and demographics. The consideration of subgroup-specific subtleties may yield supplementary perspectives.

• Gender bias: although the research identified elevated anxiety levels among women, the exclusive attention to gender-specific trends might restrict the applicability of the results to more extensive demographic cohorts.

• Definitions of resource setting variations: the preliminary objective of examining variations in anxiety levels in relation to resource settings produced inconclusive findings. Subsequent investigations ought to thoroughly examine this facet.

• Bias in publications: publication bias may arise due to the possibility that studies with significant findings will be selectively reported, which could have an impact on the overall effect estimate.

• Regional and cultural particularities: the limited presence of cultural diversity in the literature under analysis may impose restrictions on the generalizability of the study. Further investigation is warranted to examine the extent to which the association between neuroticism and anxiety differs across cultures in the context of pandemics.

• The presence of variability in the psychometric instruments utilized across studies could potentially introduce inconsistencies in measurements, which could have an adverse impact on the precision of the aggregated effect estimates.

• Insights into limited interventions: the research predominantly investigates correlations, thereby offering restricted perspectives on intervention strategies. Subsequent investigations ought to address this knowledge deficit by examining efficacious approaches to alleviate anxiety associated with neuroticism.

• External considerations regarding validity: the findings of this study may be limited in their applicability to different crisis contexts or stressors due to its narrow focus on the COVID-19 pandemic.

• Exclusive emphasis on neuroticism: the research primarily centers on neuroticism, disregarding the potential ramifications of multiple factors influencing anxiety. Further investigation is warranted to examine an even broader spectrum of contributing factors.

Further research should utilize longitudinal designs to examine the temporal dimensions of the relationships between neuroticism and anxiety over an extended period. This would enable a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics underlying these constructs. By adopting this methodology, valuable insights could be gained regarding the long-term course of psychological reactions following the acute phase of the pandemic. Comprehensive subgroup analyses encompassing a wide range of demographic variables, including but not limited to age, socioeconomic standing, and cultural distinctions, may reveal intricate patterns within the correlation between neuroticism and anxiety. Gaining insight into the way these variables interact with individual personality traits can inform community-specific interventions. An examination of protective factors, in addition to extraversion, may contribute to the advancement of knowledge regarding resilience in the face of adversity. The exploration of factors that alleviate the effects of neuroticism on anxiety may provide valuable insights for the development of interventions and support systems that aim to improve psychological health.

Conducting comparative studies across various global regions may shed light on cultural differences in the correlation between neuroticism and anxiety in the context of pandemics. Conducting cross-cultural research has the potential to unveil unique coping strategies and reactions, thereby enhancing our overall comprehension of whether these associations are universal or culturally specific.

The significance of incorporating neuroticism into anxiety intervention design, especially in times of crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, is highlighted by our findings. Personalized therapeutic strategies that target the distinct obstacles encountered by individuals with elevated levels of neuroticism might prove to be more efficacious in alleviating symptoms associated with anxiety. By incorporating the findings of this study into their messaging and public health campaigns, communication strategies that effectively connect with individuals who exhibit high levels of neuroticism can be developed. Developing communications that offer reassurance, trustworthy information, and coping mechanisms could prove to be especially advantageous for this specific demographic. The integration of our findings into clinical practice can be achieved by mental health professionals through the integration of neuroticism assessments during the evaluation of anxiety. By incorporating personalized treatment plans that recognize the impact of neuroticism on anxiety, therapeutic interventions can be rendered more efficacious. Community support programs that seek to enhance mental well-being should contemplate the customization of assistance services to cater to the needs of individuals who exhibit elevated levels of neuroticism. To address the unique requirements of this demographic, these programs may encompass focused counseling sessions, seminars on stress management, and community-building exercises.

In brief, forthcoming research ought to further investigate the intricacies of the correlation between neuroticism and anxiety by utilizing a variety of methodologies and considering a broad spectrum of influential factors. The practical ramifications underscore the necessity for focused interventions and approaches that can be applied in public health, clinical, and community environments to assist people experiencing crises who exhibit differing degrees of neuroticism.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ER: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. MG: Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MS: Data curation, Software, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ST: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. OR: Writing – review & editing. NL: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Sousa, GMD, Tavares, VDO, de Meiroz Grilo, MLP, Coelho, MLG, Lima-Araújo, GL, Schuch, FB, et al. Mental health in COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-review of prevalence meta-analyses. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703838

2. Delpino, FM, da Silva, CN, Jerônimo, JS, Mulling, ES, da Cunha, LL, Weymar, MK, et al. Prevalence of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 2 million people. J Affect Disord. (2022) 318:272–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.003

3. Lasheras, I, Gracia-García, P, Lipnicki, D, Bueno-Notivol, J, López-Antón, R, de la Cámara, C, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:9353. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249353

4. Ludwig-Walz, H, Dannheim, I, Pfadenhauer, LM, Fegert, JM, and Bujard, M. Anxiety among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. (2023) 12:64. doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02225-1

5. Panchal, U, Vaquerizo-Serrano, JD, Conde-Ghigliazza, I, Aslan Genç, H, Marchini, S, Pociute, K, et al. Anxiety symptoms and disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychiatry. (2023) 37:100218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpsy.2023.06.003

6. Saeed, H, Eslami, A, Nassif, NT, Simpson, AM, and Lal, S. Anxiety linked to COVID-19: a systematic review comparing anxiety rates in different populations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:2189. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042189

7. Quek, TT, Tam, WW, Tran, BX, Zhang, M, Zhang, Z, Ho, CS, et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2735. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16152735

8. Patra, I, Muda, I, Ketut Acwin Dwijendra, N, Najm, MA, Hamoud Alshahrani, S, Sajad Kadhim, S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on death anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic. Omega. (2023):302228221144791. doi: 10.1177/00302228221144791. [Epub ahead of print].

9. He, J, Lin, J, Sun, W, Cheung, T, Cao, Y, Fu, E, et al. The effects of psychosocial and behavioral interventions on depressive and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:19094. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45839-0

10. Améndola, L, Weary, D, and Zobel, G. Effects of personality on assessments of anxiety and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 141:104827. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104827

11. Sep, M, Steenmeijer, A, and Kennis, M. The relation between anxious personality traits and fear generalization in healthy subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biobehav Rev. (2019) 107:320–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.029

12. Banfi, J, and Randall, J. A meta-analysis of trait mindfulness: relationships with the Big Five personality traits, intelligence, and anxiety. J Res Pers. (2022) 101:104307. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2022.104307

13. Mughal, AY, Devadas, J, Ardman, E, Levis, B, Go, VF, and Gaynes, BN. A systematic review of validated screening tools for anxiety disorders and PTSD in low to middle income countries. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:338. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02753-3

14. Árbol, JR, Ruiz-Osta, A, and Montoro Aguilar, CI. Personality traits, cognitive styles, coping strategies, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on healthy youngsters. Behav Sci. (2021) 12:5. doi: 10.3390/bs12010005

15. Gashi, D, Gallopeni, F, Imeri, G, Shahini, M, and Bahtiri, S. The relationship between Big Five personality traits, coping strategies, and emotional problems through the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. (2022) 42:29179–88. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03944-9

16. Eroglu, A, Suzan, OK, Hur, G, and Cinar, N. The relationship between fear of COVID-19 and psychological resilience according to personality traits of university students: a PATH analysis. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2023) 42:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2022.11.001

17. Gruda, D, and Ojo, A. All about that trait: examining extraversion and state anxiety during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic using a machine learning approach. Personal Individ Differ. (2022) 188:111461–1. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111461

18. Kumar, VV, and Tankha, G. The relationship between personality traits and COVID-19 anxiety: a mediating model. Behav Sci. (2022) 12:24. doi: 10.3390/bs12020024

19. Ikizer, G, Kowal, M, Aldemir, İD, Jeftić, A, Memisoglu-Sanli, A, Najmussaqib, A, et al. Big Five traits predict stress and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence for the role of neuroticism. Personal Individ Differ. (2022) 190:111531. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2022.111531

20. Joneghani, NA, and Sajjaian, I. The mediating role of perceived stress in the relationship between neuroticism and death anxiety among women in Isfahan during the coronavirus pandemic. J Educ Health Promot. (2023) 12:78. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_505_22

21. Kiziloğlu, B, and Karabulut, N. The effect of personality traits of surgical nurses on COVID-19 fear, work stress, and psychological resilience in the pandemic. J Perianesth Nurs. (2023) 38:572–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2022.10.006

22. Mazza, C, Ricci, E, Marchetti, D, Fontanesi, L, Di Giandomenico, S, Verrocchio, MC, et al. How personality relates to distress in parents during the COVID-19 lockdown: the mediating role of child’s emotional and behavioral difficulties and the moderating effect of living with other people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6236. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176236

23. Metz, M, Whitehill, R, and Alraqiq, HM. Personality traits and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder among dental residents during COVID-19 crisis. J Dent Educ. (2022) 86:1562–72. doi: 10.1002/jdd.13034

24. Mousavi, N, Effatpanah, M, Molaei, A, and Alesaeidi, S. The predictive role of personality traits and demographic features on post-traumatic stress disorder in a sample of COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. (2023) 30:52. doi: 10.1186/s43045-023-00323-3

25. Nazari, N, Safitri, S, Usak, M, Arabmarkadeh, A, and Griffiths, MD. Psychometric validation of the Indonesian version of the fear of COVID-19 scale: personality traits predict the fear of COVID-19. Int J Ment Heal Addict. (2023) 21:1348–64. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00593-0

26. Olashore, AA, Akanni, OO, and Oderinde, KO. Neuroticism, resilience, and social support: correlates of severe anxiety among hospital workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria and Botswana. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:398. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06358-8

27. Qian, K, and Yahara, T. Mentality and behavior in COVID-19 emergency status in Japan: influence of personality, morality and ideology. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0235883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235883

28. Xu, Q, Li, D, Dong, Y, Wu, Y, Cao, H, Zhang, F, et al. The relationship between personality traits and clinical decision-making, anxiety and stress among intern nursing students during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2023) 16:57–69. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S387682

29. Lassen, ER, Hagen, K, Kvale, G, Eid, J, Le Hellard, S, and Solem, S. Personality traits and hardiness as risk-and protective factors for mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Norwegian two-wave study. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:610. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04237-y

30. Odachi, R, Takahashi, S, Sugawara, D, Tabata, M, Kajiwara, T, Hironishi, M, et al. The Big Five personality traits and the fear of COVID-19 in predicting depression and anxiety among Japanese nurses caring for COVID-19 patients: a cross-sectional study in Wakayama prefecture. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0276803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276803

31. Al-Omiri, MK, Alzoubi, IA, Al Nazeh, AA, Alomiri, AK, Maswady, MN, and Lynch, E. COVID-19 and personality: a cross-sectional multicenter study of the relationship between personality factors and COVID-19-related impacts, concerns, and behaviors. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.608730

32. Proto, E, and Zhang, A. COVID-19 and mental health of individuals with different personalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2021) 118:e2109282118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2109282118

33. Bellingtier, JA, Mund, M, and Wrzus, C. The role of extraversion and neuroticism for experiencing stress during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:12202–12. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02600-y

34. Choi, J. Effects of Big Five personality traits on self-perceived anxiety before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mod Psychol Stud. (2023) 29:18. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol29/iss1/18

35. Getzmann, S, Digutsch, J, and Kleinsorge, T. COVID-19 pandemic and personality: agreeable people are more stressed by the feeling of missing. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10759. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182010759

36. Kluwe-Schiavon, B, de Zorzi, L, Meireles, J, Leite, J, Sequeira, H, and Carvalho, S. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal: the role of personality traits and emotion regulation strategies. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0269496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269496

37. Kong, X, Cao, Y, Luo, X, and He, L. The correlation analysis between the appearance anxiety and personality traits of the medical staff on nasal and facial pressure ulcers during the novel coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Nurs Open. (2021) 8:147–55. doi: 10.1002/nop2.613

38. Kroencke, L, Geukes, K, Utesch, T, Kuper, N, and Back, MD. Neuroticism and emotional risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Pers. (2020) 89:104038. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2020.104038

39. Liu, S, Lithopoulos, A, Zhang, CQ, Garcia-Barrera, MA, and Rhodes, RE. Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy. Personal Individ Differ. (2021) 168:110351. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110351

40. Nikčević, AV, Marino, C, Kolubinski, DC, Leach, D, and Spada, MM. Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. (2021) 279:578–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.053

41. Norouzi Zad, Z, Bakhshayesh, A, and Salehzadeh Abarghoui, M. The role of personality traits and lifestyle in predicting anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based cross-sectional study. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. (2022) 31:84–101. Available at: http://journal.gums.ac.ir/article-1-2428-en.html

42. Rossi, C, Bonanomi, A, and Oasi, O. Psychological wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: the influence of personality traits in the Italian population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:5862. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115862

43. Taşci, G, and Özsoy, F. Relation of anxiety and hopelessness levels of healthcare employees with personality traits during COVID-19 period. J Contemp Med. (2022) 12:509–14. doi: 10.16899/jcm.1094939

44. Üngür, G, and Karagözoğlu, C. Do personality traits have an impact on anxiety levels of athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic? Curr Issues Pers Psychol. (2021) 9:246–57. doi: 10.5114/cipp.2021.106138

45. Widiger, TA, and Oltmanns, JR. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry. (2017) 16:144–5. doi: 10.1002/wps.20411

46. Çıvgın, U, Yorulmaz, E, and Yazar, K. Mediator role of resilience in the relationship between neuroticism and psychological symptoms: COVID-19 pandemic and supermarket employees. Curr Psychol. (2023) 42:20226–38. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-04725-8

47. Pérez-Mengual, N, Aragonés-Barbera, I, Moret-Tatay, C, and Moliner-Albero, AR. The relationship of fear of death between neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.648498

48. Akbari, M, Seydavi, M, Babaeifard, M, Firoozabadi, MA, Nikčević, AV, and Spada, MM. Psychometric properties and psychological correlates of the COVID-19 anxiety syndrome scale: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2023) 30:931–49. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2861

49. Bayrı Bingöl, F, Dişsiz, M, and Demirgöz Bal, M. The effect of personality traits on COVID-19 stress level during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Eur Arch Med Res. (2023) 39:30–8. doi: 10.4274/eamr.galenos.2022.82612

50. Ahmed, O, Hossain, KN, Siddique, RF, and Jobe, MC. COVID-19 fear, stress, sleep quality and coping activities during lockdown, and personality traits: a person-centered approach analysis. Personal Individ Differ. (2021) 178:110873. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110873

51. Alexescu, T-G, Nechita, MS, Maierean, AD, Vulturar, DM, Handru, MI, Leucuța, DC, et al. Change in neuroticism and extraversion among pre-university education employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicina. (2022) 58:895. doi: 10.3390/medicina58070895

52. Birkelund, KS, Rasmussen, SS, Shwank, SE, Johnson, J, and Acharya, G. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's perinatal mental health and its association with personality traits: an observational study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2023) 102:270–81. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14525

53. Bongelli, R, Canestrari, C, Fermani, A, Muzi, M, Riccioni, I, Bertolazzi, A, et al. Associations between personality traits, intolerance of uncertainty, coping strategies, and stress in Italian frontline and non-frontline HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic—a multi-group path-analysis. Healthcare. (2021) 9:1086. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9081086

54. Cena, L, Rota, M, Calza, S, Janos, J, Trainini, A, and Stefana, A. Psychological distress in healthcare workers between the first and second COVID-19 waves: the role of personality traits, attachment style, and metacognitive functioning as protective and vulnerability factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11843. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211843

55. Agbaria, Q, and Mokh, AA. Coping with stress during the coronavirus outbreak: the contribution of Big Five personality traits and social support. Int J Ment Heal Addict. (2022) 20:1854–72. doi: 10.1007/s11469-021-00486-2

56. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

57. Sun, Y, Wu, Y, Fan, S, Dal Santo, T, Li, L, Jiang, X, et al. Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. BMJ. (2023) 380:e074224. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-074224

Keywords: anxiety, COVID-19, neuroticism traits, systematic review, meta analysis

Citation: Regzedmaa E, Ganbat M, Sambuunyam M, Tsogoo S, Radnaa O, Lkhagvasuren N and Zuunnast K (2024) A systematic review and meta-analysis of neuroticism and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1281268. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1281268

Edited by:

Ana Benito, Hospital General Universitario De Valencia, SpainReviewed by:

Mohammad Ali Zakeri, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, IranHesham Fathy Gadelrab, Mansoura University, Egypt

Copyright © 2024 Regzedmaa, Ganbat, Sambuunyam, Tsogoo, Radnaa, Lkhagvasuren and Zuunnast. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Khishigsuren Zuunnast, a2hpc2hpZ3N1cmVuQG1udW1zLmVkdS5tbg==

Enkhtuvshin Regzedmaa

Enkhtuvshin Regzedmaa Mandukhai Ganbat

Mandukhai Ganbat Munkhzul Sambuunyam

Munkhzul Sambuunyam Solongo Tsogoo

Solongo Tsogoo Otgonbayar Radnaa4

Otgonbayar Radnaa4 Khishigsuren Zuunnast

Khishigsuren Zuunnast