95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 28 September 2023

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1265910

As investigations into the efficacy of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to treat depression continue, there is a need to study the possible mechanisms of action that may contribute to the treatment’s antidepressant effects. Through a two-round Delphi design, the current study investigated experts’ opinions on the psychological mechanisms of action associated with the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and the ways such mechanisms may be promoted through the preparation, dosing, and integration components of treatment. Fourteen and fifteen experts, including both clinical psychedelic researchers and therapists, participated in Round 1 and Round 2 of the study, respectively. Thematic analysis identified nine important or promising ‘mechanistic themes’ from Round 1 responses: psychological flexibility, self-compassion, mystical experiences, self-transcendence, meaning enhancement, cognitive reframing, awe, memory reconsolidation and ego dissolution. These mechanisms were presented back to experts in Round 2, where they rated ‘psychological flexibility’ and ‘self-compassion’ to be the most important psychological mechanisms in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for depression. Strategies or interventions recommended to promote identified mechanisms during the preparation, dosing, and integration components of treatment were nonspecific to the endorsed mechanism. The findings from this study provide direction for future confirmatory mechanistic research as well as provisional ideas for how to support these possible therapeutic mechanisms.

There is increasing evidence to support classic psychedelics with psychotherapy as novel treatments for depression (1). Classic psychedelics are a group of psychoactive substances that includes lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin, N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT; often consumed as ayahuasca) and mescaline. Recent clinical trials have found that psilocybin, ayahuasca and LSD alongside professional support produced significant, rapid reductions in depression (2–7), which in some cases has been sustained at long term follow up (8, 9). Much of this research has delivered psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, whereby psychedelic dosing is paired with several psychotherapy sessions. With a few exceptions, many of the trials to date have had small sample sizes or lacked control groups, although several large-scale randomized controlled trials are currently underway globally. Further, there is growing pressure for these substances to be implemented into clinical practice, with Australia recently approving authorized psychiatrists to prescribe psilocybin to those with treatment resistant depression (10).

As efficacy trials continue and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy appears closer to being implemented into clinical practice, it is vital that there are simultaneous investigations into how psychedelics may be working to alleviate symptoms of depression. Gaining a greater understanding of the underlying mechanisms of action enables treatment outcomes to be optimized through the identification of ‘active ingredients’ of treatment (11). Such components may then be specifically targeted in treatments, while redundant elements are removed (12). This knowledge may extend to the development or modification of other depression therapies, while also contributing to the refinement of theories of depression and increasing the ability to implement preventative measures (11). Mechanistic research can also establish individuals who may be unsuitable for a particular treatment or who are unlikely to respond (13).

Unlike typical pharmacological treatments of depression, psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy generally entails a substantial altered state of consciousness. Participants from clinical trials have reported their acute psychedelic experiences to be personally relevant and meaningful (14), often relating to processes attributed to the maintenance of depression symptoms by the individual (15). These reports may suggest that psychological mechanisms of action may be operating to alleviate depression symptoms within the acute psychedelic experience and beyond. Psychological mechanisms of action are a powerful level of analysis to investigate in antidepressant treatments, due to the possibility of amending and manipulating active treatment components (11, 12). However, there is also notable complexity in investigating such processes in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, due to the various intervention types employed in various treatment phases (e.g., preparation, dosing and integration sessions) as well as the challenges in measuring variables associated with altered states of consciousness.

Preliminary findings have provided support for the role of a variety of psychological mechanisms of action for the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. This research has largely focused on examining the role of the acute psychedelic experience. Findings have suggested that ‘peak’ psychedelic experiences, such as undergoing a mystical experience (feeling a sense of unity with others and the universe, transcendence of time and space, intense positive mood, and a sense of ineffability), may mediate the relationship between psychedelic use and reductions depression post therapy (16, 17). Others have investigated more conventional psychological mechanisms, such as experiential avoidance (18) and rumination (19), with these processes also found to be reduced following psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. The identification of seemingly dissimilar mechanism types, with some relating to acute experiences and others relating to changes in the psychology of a person, highlights the complexity of conceptualizing how treatments may produce change and has been described in other psychotherapy research [(e.g., 20)]. While there is ultimately a need to understand the relationships between various types of mechanism in a change process, studies to date have typically investigated a single mechanism (e.g., mystical experiences) or mechanism type (e.g., variations on the acute psychedelic experience).

There is currently a dearth of investigations into how psychological mechanisms may operate or be addressed across the whole treatment to support lasting antidepressant effects. The current study, therefore, seeks to explore the possible mechanisms of action in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for depression across the treatment process through a two-round Delphi technique of experts in the field. The Delphi technique was selected to complement findings of a systematic review on the same topic (under review), as the Delphi technique typically provides a more contemporary depiction of current thinking. This is particularly relevant in fields which are novel and quickly developing, like the psychedelic literature. Furthermore, it enables the exploration of experts’ experiences which may not be included in the available literature, such as those of therapists delivering the treatment. The primary aim of this study was to explore expert views on the psychological mechanisms of action associated with the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Aim 1). A secondary aim was to gain expert views on how such mechanisms may be promoted through psychotherapy in the preparation, dosing, and integration components of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Aim 2).

To address study aims, a two-step modified Delphi technique utilizing online surveys was adopted. The Delphi technique assumes the opinion of the group is more valid than that of an individual, so seeks to gather the opinions of a group of experts in the field of interest (21). The Delphi method is characterized by four main features:

(1) anonymity, enabling the expression of opinions without influence of the group;

(2) feedback, allowing experts to clarify or alter their opinions from previous rounds;

(3) iteration, permitting the refinement on views based on feedback from prior rounds; and

(4) statistical analysis of responses (22).

Commonly, the method commences with a brainstorming round, whereby experts are able to provide their general opinions on the topic in response to open-ended questions, followed by a round whereby variables are rated on their importance (23). Finally, a third round of ranking variables against one another may be conducted (23). This final step was not conducted here, due to the study’s fundamentally exploratory aims.

The Delphi method utilizes purposeful, rather than random sampling to recruit identified experts in the chosen field (21). Heterogeneity within experts is considered desirable as it may elicit a wide variety of opinions within the field. In the present study, expert heterogeneity was achieved by compiling lists of international researchers as well as therapists who had been involved in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy trials. Explicit inclusion criteria were developed to identify individuals with specialized knowledge in the field of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for depression: (i) researchers were eligible if they had at least one first or last author publication that was included in a systematic review of the same topic being completed concurrently by the current authors (under review); (ii) therapists were recruited through existing professional networks and considered eligible for participation if they had conducted psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for depression in the context of a clinical trial.

Following ethical approval from Swinburne University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 20215758-8858), eligible experts were emailed an invitation to participate in the study. A total of 75 researchers and 15 therapists were invited to participate in the study. The substantial skew toward inviting researchers was due to the ease of identifying relevant researchers compared to therapists. These two groups were collapsed during analysis.

The study was an iterative process that involved two rounds of surveys administered online through Qualtrics software, version 2022 (Qualtrics, 2022). See Figure 1 for a flow chart of the study design and Supplementary material for the surveys. The aim of Round 1 was twofold: to brainstorm various psychological mechanisms of action that experts believe to be relevant to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Aim 1); and to gain expert views on how such mechanisms may be promoted through psychotherapy across the preparation, dosing and integration components of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Aim 2). Each mechanism was probed individually in a series of items. The online survey permitted participants to loop back to the start to include as many mechanisms as desired. For each mechanism, participants were asked to:

(1) describe a mechanism they believed to be ‘important or promising’ to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. In accordance with the study’s exploratory nature, the term ‘promising’ was used to encourage experts to include mechanisms that may not have extant published support (Aim 1);

(2) give their rationale for including the mechanism. To provide guidance, brief examples of possible rationales were offered: “e.g., empirical evidence, theoretical importance, anecdotal or personal experience” (Aim 1);

(3) indicate whether the mechanism was related to a specific classic psychedelic (e.g., ayahuasca, LSD, DMT, psilocybin, mescaline or ‘other’). Experts were able to select as many psychedelics as they desired (Aim 1), and;

(4) describe ways in which this mechanism could be ‘supported or promoted’ during preparation, dosing, and integration sessions (Aim 2).

Experts were then directed to demographic questions relating to their age, gender identity, main country of work, role in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and expertise in working with a specific classic psychedelic.

The Round 2 survey exclusively addressed Aim 1 of the study and intended to rate the mechanisms (derived from the data analysis of Round 1 responses) on importance to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. In the Round 2 survey, experts were presented with the mechanisms derived from the analysis of Round 1 responses and were asked to rate the importance of the mechanism on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all important to 5 = Extremely important), alongside an optional reason. A definition was provided alongside the mechanism and experts were requested to rate the importance of the mechanism based on the definition provided to allow for comparison between responses. Demographic questions from Round 1 were then repeated.

The process of analyzing responses relating to Aim 1 of Round 1 was similar to that described by Moynihan and colleagues (24) and Milat and colleagues (25). An inductive thematic analysis was used to interpret the responses to the open-ended questions of mechanisms associated with the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. These responses were examined, synthesized, and integrated under broad coding themes, with the aim of identifying themes that linked participants descriptions of mechanisms. These themes were then presented back to experts in Round 2 as ‘mechanisms’ and will henceforth be referred to as ‘mechanistic themes.’ An inductive approach was deemed appropriate due to the exploratory nature of the study aims (26). Once finalized, a definition was developed to accompany each mechanistic theme in the Round 2 survey for the sake of clarity. Both emic (via participant responses) and etic (via accepted definitions from the literature) perspectives were employed in the development of definitions (24). Emic perspectives were utilized when reported themes were not ideas commonly discussed in the literature, or experts had provided clear, specific, and consistent definitions themselves. Etic perspectives were employed when themes had overwhelmingly agreed upon definitions regularly drawn upon in the literature or when experts themselves had directly drawn from accepted theories or relevant psychometric measures.

Qualitative content analysis was used to describe the ways in which each specific mechanism could be promoted during each stage of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Aim 2). This included synthesizing expert responses for clarity and conciseness, as well as removing repetition. Qualitative content analysis seeks to provide literal, descriptive reports of patterns across data, rather than attempting to develop rich meaning or theory from responses (27). This analytic approach was utilized for Aim 2, as the majority of responses were too brief to support more nuanced inferences (28).

Descriptive and frequency statistics were calculated in in IBM SPSS (version 28) to analyze the perceived level of importance of the different mechanisms presented in the survey. Qualitative content analysis was conducted on responses to open ended questions regarding the inclusion of the mechanism as a promising or important mechanism, as well as the corresponding definition. Qualitative content analysis was also conducted on the open-text responses regarding additional mechanisms that were not included in the Round 2 survey that experts considered important to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

A total of 90 experts (75 researchers, 15 therapists) were invited to participate in the Round 1 survey. Fourteen experts completed the entirety of the Round 1 survey and 15 completed Round 2 (see Table 1 for participant demographics).

In Round 1, a total of 27 responses were provided regarding promising mechanisms of action. Eighty percent of responses indicated that the mechanism was not related to a specific psychedelic. Psilocybin and ayahuasca were the only specific psychedelics endorsed to be associated with specific mechanisms. Thematic analysis generated nine themes from responses regarding important or promising mechanisms of action in Round 1. In Round 2, these themes were expressed as mechanisms and presented with definitions back to experts, where they rated each mechanism on its importance to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Psychological flexibility was identified as the most important mechanism, receiving a mean importance rating of 4.32. This was closely followed by self-compassion, which received a mean importance rating of 4.31. See Table 2 and Figure 2 for expert rated importance of mechanisms in the antidepressant effects of psychedelic therapy. Results from Round 1 and Round 2 are presented together below.

This mechanistic theme encompasses responses which described psychological flexibility and components of the acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) hexaflex [acceptance, contact with the present moment, cognitive defusion, self-as-context, values and committed action (29)], as responses typically described these facets when elaborating on ‘psychological flexibility’. It was suggested that psychedelics may encourage “being in contact with the present moment, fully aware of emotions, sensations, and thoughts, welcoming them, including the undesired ones, and moving in a pattern of behavior in the service of chosen values.” Another expert suggested that psychedelics may encourage flexibility in “considering both one’s story (major life narrative) [and] expectations of how one should behave in the moment [which may] loosen habitual patterns that maintain depression.” Several experts detailed just one of the six core processes in their response (e.g., psychedelics may “lead to moments of experiencing self-as-context”), which may suggest that some aspects of the ACT model may be considered more relevant than others in the context of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

The mechanistic theme of self-compassion referred to expert’s descriptions of witnessing participants experience acute self-compassion during the peak psychedelic experience, and for this compassion to continue following treatment. This theme was indicated to be associated with psychological flexibility and memory reconsolidation, with one expert describing psychedelics to lead into “re-experiencing specific, traumatic events, and eventually those experiences softening into moments of self-compassion and alternate perspectives.” Self-compassion was also reported to be important independent of other processes, mechanisms, or themes. During analysis, self-compassion was recognized as a mechanistic theme independent from others due to the reporting of its importance across various response types.

Several participant responses were collated under the mechanistic theme of mystical experiences. These responses either directly used the term ‘mystical experience’ or included facets of ineffability (difficulty describing the experience), sacredness, unity with all things and noetic quality (sense of experiencing truth and the ultimate reality).

The mechanistic theme of self-transcendence referred to participant descriptions of identifying with something larger than the self. Experts described this experience as potentially reducing the ingrained self-narratives commonly experienced by those with depression. It was suggested that this experience may promote the ‘self-as-context’ principle that is a core component of ACT, as well as being associated with oceanic boundlessness (a term often linked to mystical experiences). Responses under this mechanistic theme differed from those of ego dissolution (see below) in that self-transcendence was discussed as both an experience and a trait which extended beyond the peak psychedelic experience, while ego dissolution was exclusively discussed in the context of the peak psychedelic experience.

Experts described psychedelic engendered meaning enhancement to play an important role in the antidepressant effects of psychedelic therapy. As defined in the literature, meaning enhancement can relate to the amplification of the perceived meaning of objects, activities, relationships, emotions, thoughts and beliefs (30). Specifically relating to the treatment of depression, one participant identified that psychedelics may result in an “amplified significance of … therapeutic insights which emerge during treatment.”

The mechanistic theme of cognitive reframing referred to participant responses describing a change or reframe of an individual’s ingrained cognitions (e.g., thoughts, beliefs, memories, perspectives) about the self, world and others that contribute to the ongoing experience of depression. Responses described the capacity for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy to encourage “the emergence of new perspectives on existing mental issues and life situations,” which were previously “outside the minds habituated ways of action.” “The discovery of different options [and] patterns of thought and behavior” may apply to “many different areas – worldview, relationships, self-esteem, etc.’. These responses differed from those relating to psychological flexibility as they emphasized altering thoughts, perspective, or beliefs, and not defusion from thoughts.

Undergoing an experience of awe was identified as a mechanistic theme in participant responses. Originally presented in the context of psychedelics by Hendricks (31), awe is an emotion suggested to arise in response to coming into contact with vastness, which must be accommodated through changes to existing knowledge structures (32, 33). Accommodation is required for one to make sense of the encounter with vastness, which may either be perceptual (e.g., witnessing a boundless ocean or large human made structure) or conceptual (e.g., an idea with wide reaching implications). In the current study, participants described awe in a spiritual context, and suggested it could be promoted by ‘exposure to nature, music, art and other stimuli’ while under the influence of a psychedelic.

Various participant responses highlighted the relevance of memories, particularly memories of traumatic events, as possibly associated with the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Experts indicated that throughout the psychedelic dosing sessions, individuals may re-experience traumatic events and the emotions this event precipitated. This occurrence may lead to further processing of the events and memories being reconsolidated with a more adaptive perspective. One expert suggested that, in this way, psychedelics may act as a catalyst for undergoing exposure-like therapy.

Defined as the disruption to boundaries between the self and world and the increased sense of unity with others and one’s surroundings, ego dissolution is a commonly described mechanism in the literature (34, 35). One participant noted that ego dissolution “is arguably just one sub-measure of mystical-type experiences.” However, as ego dissolution was reported exclusive to mystical experience by some experts and is often discussed in the literature independent of mystical experiences [(e.g., 36)], it was decided to distinguish between the two.

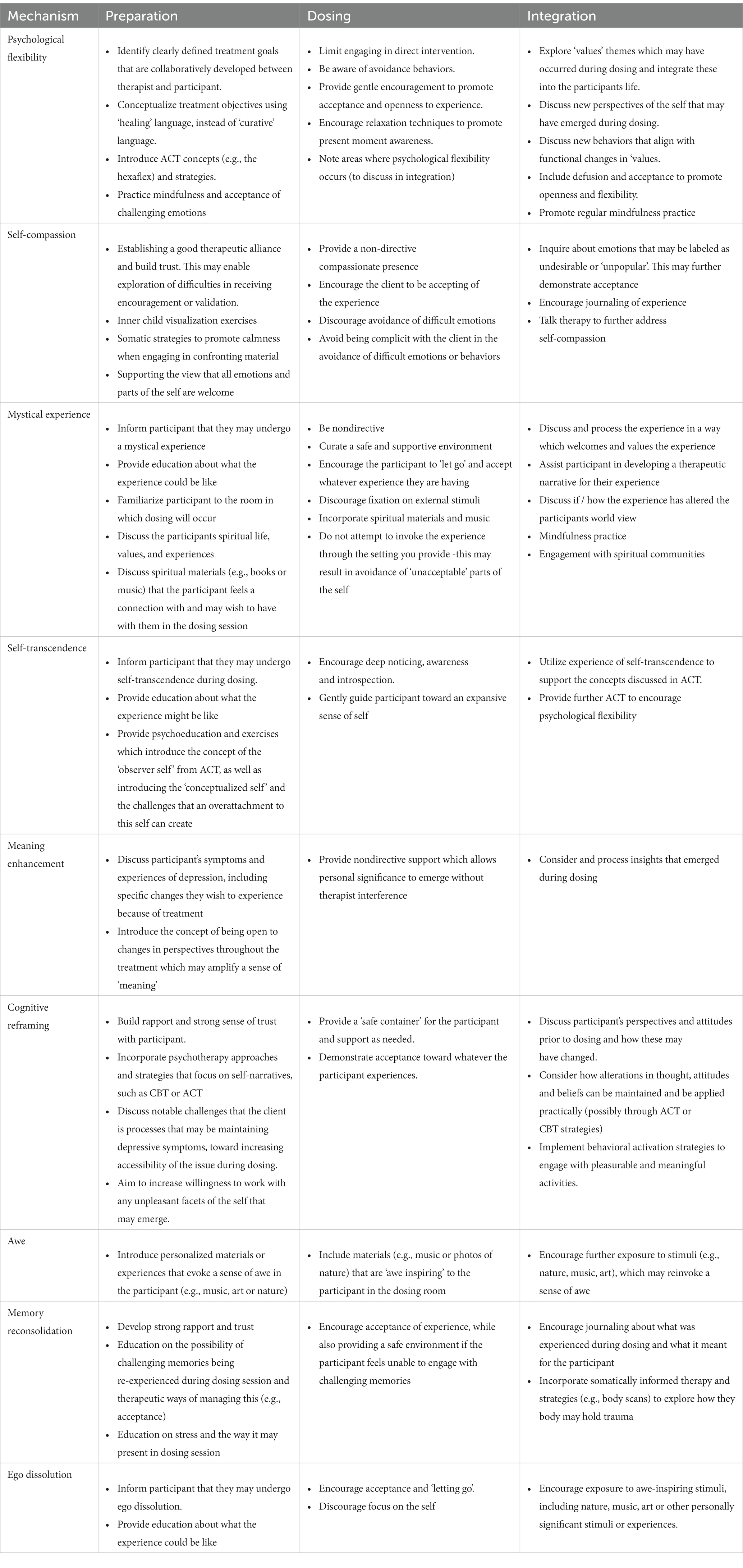

Experts provided a wide variety of strategies or techniques to promote mechanisms during preparation, dosing and integration. See Table 3. Common responses related to educating participants about peak psychedelic experiences that may occur during dosing, as well as conducting general psychoeducation, rapport building and goal setting. However, due to the small sample size, these strategies should be considered highly exploratory.

Table 3. Expert reported strategies for promotion psychological mechanisms of action during preparation, dosing, and integration sessions.

This study aimed to explore experts’ views on important or promising psychological mechanisms of action that may contribute to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, and the ways in which such mechanism may be promoted during the preparation, dosing, and integration components of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. To our knowledge, it is the first study to utilize the Delphi technique in the field of psychedelic research. We identified nine mechanistic themes from responses given in Round 1 of the study. As expected, these were varied in type, with some relating to participant experiences during psychedelic dosing, while others described changes in the participant’s perspectives and cognitions. A wide variety of recommendations were provided regarding the ways in which such mechanisms may be promoted during the preparation, dosing and integration components of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Mechanisms were fed back to experts in Round 2, with psychological flexibility rated to be the most important mechanism of action for the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

The high average rating of importance received for the role of psychological flexibility in the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is in line with previous research. Psychological flexibility and the components of the ACT hexaflex have been proposed to have relevance in the therapeutic processes of all components of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Even without the inclusion of psychotherapy sessions, one trial in healthy participants found psychological flexibility to correlate with reductions in depression scores following ayahuasca use (37) and similar findings have been reported in a retrospective survey study (38). This has led to suggestions that including a modified version of current ACT protocols may be an appropriate therapeutic modality to pair with psychedelics, as it could assist in engendering further improvements in psychological flexibility and thus, depression (39, 40).

The high importance rating that self-compassion received from experts was an unexpected finding, as self-compassion has received limited attention within the psychedelic literature thus far. However, retrospective surveys of individuals who had previously used a classic psychedelic found increases in self-compassion to be associated with reductions in depression symptoms (41). In addition, interviews with clinical trial participants experiencing cancer-related distress found self-compassion to be a major theme during participant’s psilocybin experience (15), with similar reports from individuals undertaking psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for alcohol use disorder (42). Several participants from this trial specifically attributed the clinical improvements they had observed to increases in self-compassion (42). These findings and others have led to the recent development of a compassion focused therapeutic protocol for psychedelic therapy (43), which has yet to be implemented in practice. Additionally, there has yet to be mediational analysis published on the relationship between self-compassion and depression change within a psychedelic clinical trial, to the best of our knowledge. Considering findings from the current study, further investigations into the role of self-compassion in the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy are needed.

Several mechanisms relating to peak psychedelic experiences, such as mystical experiences, self-transcendence, and ego dissolution, were reported by experts. Self-transcendence has received considerably less attention than mystical experiences in the current literature, despite there being overlap between the two constructs regarding the experience of unity and connectedness. In the current study, some experts suggested that mystical experiences, self-transcendence, ego-dissolution, and awe all describe a variation of the same peak psychedelic experience. This was despite other experts reporting more than one of these experiences to be important in their Round 1 responses and providing distinct definitions for the various peak psychedelic experiences. Future studies should attempt to characterize the similarities and differences of these overlapping constructs as well as continuing to investigate the role these variables may have on the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Experts emphasized the importance of appropriate integration for peak psychedelic experiences, including meaning enhancement and memory reconsolidation, to support antidepressant effects. It was also suggested that such experiences may be counter-therapeutic if resolution did not occur, consistent with previous research (44).

Several important strategies or interventions were identified that may promote the mechanisms identified within the first round of responses. There was substantial overlap between experts in terms of their support for specific methods to promote efficacious psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, regardless of the primary mechanism they had endorsed. As such, discussion of these strategies here is organized by the phase of treatment they related to, rather than the specific mechanism.

Experts identified several important activities or tasks that should be conducted in the preparation sessions to promote antidepressant effects. Providing education regarding the psychedelic experience and the types of experiences participants may undergo was regularly reported, particularly in the context of the acute psychedelic experience being identified as an important antidepressant mechanism. These responses were in line with the current and historical literature in terms of the emphasis on an individual’s set and their expectations for the psychedelic experience (45). Other responses were more consistent with the typical tasks completed in early sessions of psychotherapeutic interventions, such as history-taking, building rapport, collaborative goal setting and psychoeducation. Some suggested orientating participants to certain psychotherapeutic modalities, such as ACT or cognitive behavior therapy (46), through strategies or techniques commonly employed in such modalities. This included practicing relaxation and mindfulness strategies that participants could draw on during dosing sessions if necessary. Importantly, the inclusion of specific psychotherapeutic techniques within preparation sessions, with the exception of relaxation tools, is not a focal component of the current psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for depression manuals that have been published [e.g. (39, 40)].

In line with past research, experts overwhelmingly agreed that therapists should predominantly take a non-directive approach during psychedelic dosing sessions, regardless of the mechanism they may be intending to promote. This includes ensuring the participants feel supported and safe throughout the process. Encouraging introspection and discouraging attending to external stimuli was recommended if attempting to elicit a peak psychedelic experience, such as a mystical experience or self-transcendence. There was some disagreement among experts regarding the curation of the setting to elicit such experiences, with some suggesting that incorporating spiritual materials may assist in engendering a mystical experience. However, one expert noted that excessive focus on promoting a ‘spiritual’ experience via a curated setting may inadvertently facilitate participants’ avoidance of addressing personally challenging content. Experts also suggested encouraging acceptance of whatever experience the participant was facing and for therapists to note any avoidance or inflexible behaviors that may occur (for discussion in integration sessions). This was suggested within the context of psychological flexibility, cognitive restructuring, and self-compassion mechanisms. Published manuals on conducting psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for depression similarly recommend therapists take ‘an attentive but non-intrusive presence’ throughout the dosing session (39).

Integration sessions were reported to be important to both process the acute psychedelic experience and promote long term behavior change. Experts emphasized the importance of developing a therapeutically beneficial narrative of the psychedelic experience, particularly in responses which identified peak psychedelic experiences to be an important mechanism to the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Current manuals prescribe an integration session one day following the dosing session to have participants describe their psychedelic experience from beginning to end, with minimal direction from therapists (39, 40). This may assist in committing the experience to memory, as well as commencing the process of the participant connecting insights they may have had during their psychedelic experience to their personal experience of depression. Journaling was also recommended by experts in this study and current manuals as a tool to assist the participant in making both sense and meaning of the experience.

Experts suggested drawing upon the acute psychedelic experience to provide experiential support for processes utilized in conventional psychological modalities (particularly ACT) and thus, long term behavioral change. This may include drawing upon new insights or perspectives from the psychedelic experience into identifying personal values and ways to engage in committed action (47) or discussing the experience of self-transcendence as an (extreme) example of viewing the self-as-context. All other components of the ACT hexaflex (48) were discussed to be important for promoting long term behavior change, as was behavioral activation and cognitive restructuring. Other suggestions included general talk therapy and somatically informed therapy, particularly if the participant has a history of trauma.

The findings from this study should be investigated by future research for reliability and generalizability. Given the current dearth of research emphasizing self-compassion within the psychedelic literature, and its apparent important as identified by experts in the current study, investigations into the mediational role this plays in depression change following psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is needed. Similar investigations are needed into psychological flexibility, particularly in the context of a clinical trial with a depression sample. The results of this study also underscore the importance of promoting long-term behavior change following psychedelic therapy, which has not been a major focus of research to date. Incorporating strategies from evidence-based psychotherapies into the psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy model may see further improvements on the efficacy of the treatment model and should be investigated (49). Additional research is also needed into the role of self-transcendence on clinical outcomes. There appears to be overlap between the various forms of the peak psychedelic experience (e.g., mystical experience, self-transcendence, ego dissolution and awe) discussed both within this study and in the literature in general [(e.g., 50)], with some experts in this study suggesting that the specific type of the experience may be of less important than developing a therapeutically beneficial narrative of the experience during integration sessions. Further investigation into how these experiences may be similar and different, as well as if a certain type of experience is more influential on clinical outcomes than others, may advance response prediction and the refinement of treatment design. Broadly, there is also a need for investigations into the potential conceptual and/or causal relationships between the mechanisms identified here.

The current study has several limitations that should be taken into consideration when interpreting findings. Firstly, the small sample size and low response rate may mean that the opinions of the experts including in this study are not representative of the opinions of experts in the field of psychedelic research more generally. Secondly, the strategies for promoting certain mechanisms during preparation, dosing and integration were not presented back to experts in Round 2 for discussion, and typically represented a small sample of results. Thirdly, as email addresses were not linked to expert responses, it was not possible to only invite experts to Round 2 who had fully completed the Round 1 survey. Finally, we opted to include all components relating to the ACT hexaflex under the broad term ‘psychological flexibility’ for the sake of brevity. This has impacted the specificity of findings and further investigations into the role of all components of the hexaflex have on clinical outcomes on psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy are needed.

The current Delphi study has provided insight into the mechanisms experts in the field believe to be important when psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy reduces depression. In addition, this study outlined several approaches that could be employed to support these mechanisms, according to experts. Notably, psychological flexibility was identified by experts to be the most important psychological mechanism for the antidepressant effects of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. With respect to professional support, experts highlighted the need to promote long-term behavior-change beyond the dosing session, an insight which has received minimal attention in the current literature. Future studies should conduct confirmatory investigations on the identified mechanisms, as well as investigating the potential clinical utility of therapeutic approaches reported here.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Swinburne University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

LJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MN: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. GM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The article processing charge was funded by the Centre for Mental Health, Swinburne University of Technology. These funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. LJ is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

We would like to thank the experts who provided their time and knowledge to participate in this study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1265910/full#supplementary-material

1. Schimmel, N, Breeksema, JJ, Smith-Apeldoorn, SY, Veraart, J, van den Brink, W, and Schoevers, RA. Psychedelics for the treatment of depression, anxiety, and existential distress in patients with a terminal illness: a systematic review. Psychopharmacology. (2022) 239:15–33. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-06027-y

2. Carhart-Harris, RL, Bolstridge, M, Rucker, J, Day, CMJ, Erritzoe, D, Kaelen, M, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. (2016) 3:619–27. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7

3. Davis, AK, Barrett, FS, May, DG, Cosimano, MP, Sepeda, ND, Johnson, MW, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. (2021) 78:481–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3285

4. Osório, FL, Sanches, RF, Macedo, LR, dos Santos, RG, Maia-de-Oliveira, JP, Wichert-Ana, L, et al. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a preliminary report. Brazilian J Psychiatr. (2015) 37:13–20. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1496

5. Palhano-Fontes, F, Barreto, D, Onias, H, Andrade, KC, Novaes, MM, Pessoa, JA, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med. (2019) 49:655–63. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001356

6. Sanches, RF, de Lima, OF, Dos Santos, RG, Macedo, LR, Maia-de-Oliveira, JP, Wichert-Ana, L, et al. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a SPECT study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2016) 36:77–81. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000436

7. Gasser, P, Holstein, D, Michel, Y, Doblin, R, Yazar-Klosinski, B, Passie, T, et al. Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. J Nerv Ment Dis. (2014) 202:513–20. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000113

8. Gukasyan, N, Davis, AK, Barrett, FS, Cosimano, MP, Sepeda, ND, Johnson, MW, et al. Efficacy and safety of psilocybin-assisted treatment for major depressive disorder: prospective 12-month follow-up. J Psychopharmacol. (2022) 36:151–8. doi: 10.1177/02698811211073759

9. Agin-Liebes, GI, Malone, T, Yalch, MM, Mennenga, SE, Ponté, KL, Guss, J, et al. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. J Psychopharmacol. (2020) 34:155–66. doi: 10.1177/0269881119897615

10. Therapeutic Goods Administration. (2023) Notice of final decision to amend (or not amend) the current poisons standard – Psilocybine and MDMA 2023. Available at: https://tga.gov.au/resources/publication/scheduling-decisions-final/notice-final-decision-amend-or-not-amend-current-poisons-standard-june-2022-acms-38-psilocybine-and-mdma (Accessed June 1, 2023).

11. Lemmens, LH, Müller, VN, Arntz, A, and Huibers, MJ. Mechanisms of change in psychotherapy for depression: an empirical update and evaluation of research aimed at identifying psychological mediators. Clin Psychol Rev. (2016) 50:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.09.004

12. Moldovan, R. Mechanisms of change in psychotherapy: methodological and statistical considerations. Cogn Brain Behav. (2015) 19:299:311.

13. Carey, TA, Griffiths, R, Dixon, JE, and Hines, S. Identifying functional mechanisms in psychotherapy: a scoping systematic review. Front Psych. (2020) 11:291. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00291

14. Swift, TC, Belser, AB, Agin-Liebes, G, Devenot, N, Terrana, S, Friedman, HL, et al. Cancer at the dinner table: experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of cancer-related distress. J Humanist Psychol. (2017) 57:488–519. doi: 10.1177/0022167817715966

15. Malone, TC, Mennenga, SE, Guss, J, Podrebarac, SK, Owens, LT, Bossis, AP, et al. Individual experiences in four cancer patients following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:256. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00256

16. Griffiths, RR, Johnson, MW, Carducci, MA, Umbricht, A, Richards, WA, Richards, BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1181–97. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675513

17. Ross, S, Bossis, A, Guss, J, Agin-Liebes, G, Malone, T, Cohen, B, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1165–80. doi: 10.1177/0269881116675512

18. Carhart-Harris, R, Giribaldi, B, Watts, R, Baker-Jones, M, Murphy-Beiner, A, Murphy, R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:1402–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032994

19. Watts, R, Day, C, Krzanowski, J, Nutt, D, and Carhart-Harris, R. Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Humanist Psychol. (2017) 57:520–64. doi: 10.1177/0022167817709585

20. Huibers, MJ, Lorenzo-Luaces, L, Cuijpers, P, and Kazantzis, N. On the road to personalized psychotherapy: a research agenda based on cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Front Psych. (2021) 11:607508. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.607508

21. Turoff, M, and Linstone, HA. The Delphi method-techniques and applications. Addison-Wesley. (2002).

22. Rowe, G, and Wright, G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: issues and analysis. Int J Forecast. (1999) 15:353–75. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2070(99)00018-7

23. Schmidt, RC. Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decis Sci. (1997) 28:763–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.1997.tb01330.x

24. Moynihan, S, Paakkari, L, Välimaa, R, Jourdan, D, and Mannix-McNamara, P. Teacher competencies in health education: results of a Delphi study. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0143703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143703

25. Milat, AJ, King, L, Bauman, AE, and Redman, S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int. (2013) 28:285–98. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar097

26. Guest, G, MacQueen, KM, and Namey, EE. Introduction to applied thematic analysis. Appl Thematic Anal. (2012) 3:1–21. doi: 10.4135/9781483384436.n1

27. Vaismoradi, M, Jones, J, Turunen, H, and Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. JNEP. (2016) 6:100. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100

28. Hsieh, H-F, and Shannon, SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

29. Hayes, SC, Strosahl, KD, and Wilson, KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York: Guilford Press (1999).

30. Hartogsohn, I. The meaning-enhancing properties of psychedelics and their mediator role in psychedelic therapy, spirituality, and creativity. Front Neurosci. (2018) 12:129. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00129

31. Hendricks, PS. Awe: a putative mechanism underlying the effects of classic psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 30:331–42. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1474185

32. Keltner, D, and Haidt, J. Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognit Emot. (2003) 17:297–314. doi: 10.1080/02699930302297

33. Yaden, DB, Kaufman, SB, Hyde, E, Chirico, A, Gaggioli, A, Zhang, JW, et al. The development of the AWE experience scale (AWE-S): a multifactorial measure for a complex emotion. J Posit Psychol. (2019) 14:474–88. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1484940

34. Nour, MM, and Carhart-Harris, RL. Psychedelics and the science of self-experience. Br J Psychiatry. (2017) 210:177–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.194738

35. Grof, S. Psycholytic and psychedelic therapy with LSD: toward an integration of approaches. Address to the conference of the European Association for Psycholytic Therapy, Frankfurt, West Germany. (1969).

36. Nour, MM, Evans, L, Nutt, D, and Carhart-Harris, RL. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the ego-dissolution inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. (2016) 10:269. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

37. Agin-Liebes, G, Zeifman, R, Luoma, JB, Garland, EL, Campbell, WK, and Weiss, B. Prospective examination of the therapeutic role of psychological flexibility and cognitive reappraisal in the ceremonial use of ayahuasca. J Psychopharmacol. (2022) 36:295–308. doi: 10.1177/02698811221080165

38. Davis, AK, Barrett, FS, and Griffiths, RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2020) 15:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.004

39. Guss, J, Krause, R, and Sloshower, J. The Yale manual for psilocybin-assisted therapy of depression (using acceptance and commitment therapy as a therapeutic frame). PsyArXiv. (2020).

41. Fauvel, B, Strika-Bruneau, L, and Piolino, P. Changes in self-rumination and self-compassion mediate the effect of psychedelic experiences on decreases in depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychol Conscious Theory Res Pract. (2021) 10:88–102. doi: 10.1037/cns0000283

42. Bogenschutz, MP, Forcehimes, AA, Pommy, JA, Wilcox, CE, Barbosa, PCR, and Strassman, RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. (2015) 29:289–99. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144

43. Pots, W, and Chakhssi, F. Psilocybin-assisted compassion focused therapy for depression. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:2930. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.812930

44. Roseman, L, Haijen, E, Idialu-Ikato, K, Kaelen, M, Watts, R, and Carhart-Harris, R. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the emotional breakthrough inventory. J Psychopharmacol. (2019) 33:1076–87. doi: 10.1177/0269881119855974

45. Hartogsohn, I. Set and setting, psychedelics and the placebo response: an extra-pharmacological perspective on psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 30:1259–67. doi: 10.1177/0269881116677852

47. Luoma, JB, Sabucedo, P, Eriksson, J, Gates, N, and Pilecki, BC. Toward a contextual psychedelic-assisted therapy: perspectives from acceptance and commitment therapy and contextual behavioral science. J Contextual Behav Sci. (2019) 14:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.10.003

48. Hayes, SC, Luoma, JB, Bond, FW, Masuda, A, and Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. (2006) 44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

49. Walsh, Z, and Thiessen, MS. Psychedelics and the new behaviourism: considering the integration of third-wave behaviour therapies with psychedelic-assisted therapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 30:343–9. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2018.1474088

Keywords: psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, mechanisms of action, psychological processes, depression, Delphi study

Citation: Johansen L, Liknaitzky P, Nedeljkovic M and Murray G (2023) How psychedelic-assisted therapy works for depression: expert views and practical implications from an exploratory Delphi study. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1265910. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1265910

Received: 24 July 2023; Accepted: 05 September 2023;

Published: 28 September 2023.

Edited by:

Keming Gao, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

João Carlos Alchieri, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, BrazilCopyright © 2023 Johansen, Liknaitzky, Nedeljkovic and Murray. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lauren Johansen, bGpvaGFuc2VuQHN3aW4uZWR1LmF1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.