- Department of Psychology, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX, United States

Introduction: While stigma toward autistic individuals has been well documented, less is known about how autism is perceived relative to other stigmatized disabilities. As a highly stigmatized condition with similar social cognitive features to autism, schizophrenia may offer a useful comparison for stigma. Previous studies have found that autistic people may be perceived more favorably than those with schizophrenia, but little is known about the underlying volitional thoughts that contribute to differences in how these conditions are perceived.

Methods: The present study utilizes a mixed-methods approach, allowing for a detailed understanding of how young adults perceive different diagnostic labels. 533 college undergraduates completed questionnaires reflecting their perceptions of one of eight diagnostic labels: four related to autism (autism, autistic, autism spectrum disorder, or Asperger’s), two related to schizophrenia (schizophrenia or schizophrenic), and two related to an unspecified clinical condition (clinical diagnosis or clinical disorder). Participants also completed an open-ended question regarding their thoughts about, and exposure to, these labels. Responses were compared across broader diagnostic categories (autism, schizophrenia, general clinical condition), with thematic analysis used to assess the broader themes occurring within the open-ended text.

Results: While perceptions did not differ significantly for person-first and identity-first language within labels, several differences were apparent across labels. Specifically, quantitative results indicated greater prejudice towards autism and schizophrenia than the generic clinical condition, with schizophrenia associated with more perceived fear and danger, as well as an increased preference for social distance, compared to autism. Patterns in initial codes differed across diagnostic labels, with greater variation in responses about autism than responses about schizophrenia or the general clinical condition. While participants described a range of attitudes toward autism (patronizing, exclusionary, and accepting) and schizophrenia (fear, prejudice, and empathy), they refrained from describing their attitudes toward the general clinical label, highlighting the centrality of a cohesive group identity for the development of stigma. Finally, participants reported a number of misconceptions about autism and schizophrenia, with many believing features such as savant syndrome to be core characteristics of the conditions.

Conclusion: These findings offer a more detailed account of how non-autistic individuals view autism and may therefore aid in the development of targeted programs to improve attitudes toward autism.

Introduction

Stigma has traditionally been defined as the social discrediting and marginalization that occurs in response to negatively perceived attributes within a prevailing society (1), with more modern conceptualizations emphasizing the lower status and power afforded to stigmatized groups (2, 3). One marginalized group that continues to be stigmatized across many cultures (4–6), despite recent increases in acceptance and awareness (7), is autistic people. Autistic children and adults often behave and communicate in non-normative ways, and these differences are reliably rated by non-autistic observers as less socially appealing (8, 9). Attitudes about autism do vary among non-autistic people (10), with greater autism acceptance occurring among those with more autism knowledge and experience [for a review, see Kim et al. (11)], but non-autistic observers as a whole express a general reluctance to interact with autistic people (9). This process is mitigated somewhat but still persists when raters are informed that the person they are observing is autistic [(12); for a review see, Thompson-Hodgetts et al. (13)], or when they are first educated about autistic differences, neurodiversity, and inclusion (14–17).

Stigma toward autistic differences contributes to the social exclusion of autistic people (18), increases experiences of minority stress (19), affects mental health (20), and impedes personal and professional achievement (13). This stigma can also turn inward among autistic people (19) and contribute to conscious and unconscious concealment strategies to avoid victimization (21) that are mentally and emotionally taxing and associated with poor mental health outcomes (22, 23).

Although the nature, experiences, and consequences of stigma toward autism has received considerable attention (18), less is known about how autism stigma compares to the stigma associated with other specific clinical conditions, or perceptions of clinical conditions more generally. Charting responses to a generic, unspecified clinical condition may provide a baseline to extract aspects of stigma associated with autism, and comparisons to another stigmatized neurodivergent group can specify the aspects of stigma unique to autism that can be used to target prejudice or misconceptions that are specific to autism, inform knowledge-based interventions, and improve education and dissemination of autism-relevant information.

For instance, comparing autism-related stigma to stigma toward another stigmatized condition, schizophrenia, may be instructive. Like autism, schizophrenia is defined in part by social difficulties (24), is misunderstood in the general population (25, 26), and is associated with considerable stigma (27). Unlike autism, however, schizophrenia is often characterized by negatively viewed symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. Exaggerated and distorted media portrayals (28) have reinforced stereotypes and misperceptions of people with schizophrenia as unpredictable and dangerous (29), which may contribute to fear-based stigma that is less present with autism (30). In truth, research indicates that non-clinical factors such as age and gender are stronger predictors of violence than schizophrenia (31), and those with severe mental illness are more often the victims of violence than the perpetrators of it (32).

Previous research comparing attitudes toward autism and schizophrenia suggests that stigma toward the two conditions often differs, and may relate to knowledge and stereotypes about the conditions (30). While the majority of adults can recognize the terms autism and schizophrenia, far fewer can accurately describe their characteristics (33). In particular, non-autistic people show large variability in their understanding of the causes, age of onset, and need for lifelong treatment associated with an autism or schizophrenia diagnosis (33), but tend to believe that autistic people are more capable of living a “normal” life than those with schizophrenia. In line with greater functional assessments, non-autistic people also report less stigma toward autism (34), perceiving them as intelligent and creative, while people with schizophrenia were more likely to be perceived as dangerous (30). The increased severity of stigma toward people with schizophrenia extends to social attitudes; while non-autistic people report a reluctance to interact with both autistic people and people with schizophrenia (30), this stigma is more severe and wider ranging for hypothetical interactions with a person with schizophrenia, extending to familial, workplace, and educational settings (33).

Most studies of stigma have used quantitative measures and scales to assess attitudes about autism and schizophrenia. Such approaches are useful for comparing individuals and groups of people on a uniform set of items, but they restrict responses to pre-determined questions and therefore may fail to fully capture conscious feelings. Complementing quantitative assessments with qualitative analysis in which participants describe clinical conditions in their own words allows for a richer view of how conditions are perceived. For instance, qualitative data can be used to assess specific patterns in how people stigmatize a condition instead of just quantifying degrees of stigma, help inform the underlying volitional thoughts that drive quantitative results, and determine whether emergent themes are consistent with survey data.

The present study utilizes a mixed-method approach that incorporates both self-report questionnaires and open-ended responses to understand how adults perceive autism-related diagnostic labels compared to schizophrenia-related labels, as well as general clinical labels. We hypothesized that participants would endorse more negative attributes and attitudes toward autism-related labels and a lower willingness to interact with individuals with these labels, compared to labels associated with a general diagnostic condition. However, based on previous data showing high levels of stigma toward individuals with schizophrenia, particularly around misperceptions (35, 36), as well as findings that autistic people are perceived more positively when they are labeled as autistic compared to when they are labeled as having schizophrenia (12), we hypothesized that autism-associated labels would be perceived more favorably than schizophrenia-associated labels.

It is also possible that differences in how conditions are described can affect stigma, with certain labels increasing the salience of difference, disability, or severity than others. Therefore, a secondary aim was to determine whether perceptions of clinical conditions vary between person-first (e.g., person with autism) and identity-first labels (e.g., autistic person) within diagnostic categories, as well as between different labels within the autism spectrum (e.g., Asperger’s, on the spectrum). In general, autistic adults tend to prefer identify-first language, while professionals and practitioners continue to favor person-first language (37, 38). Within the diagnostic conditions, we expected more positive perceptions for the “person with Asperger’s” label relative to other autism-related labels, as some findings have suggested that the Asperger’s label is associated with less stigma and considered less severe compared to the autism label (39). We also explored whether person-first labels (“person with schizophrenia”) would be perceived more positively than identity-first labels (“schizophrenic person”) within the schizophrenia condition, as would be predicted by proponents of person-first language who seek to separate the person from a highly stigmatized condition (40). There is a lack of consensus on preferred technology among people with severe mental illness, with individual preferences often varying across situations and contexts (41), while clinicians often encourage person-first language in an effort to reduce stigma (42). However, because person-first language in practice is typically restricted to conditions that are stigmatized, such efforts may backfire and unintentionally accentuate stigma rather than reduce it (43). While previous literature has suggested an association between identity-first language and greater stigma (44), more recent findings suggest that it is the lack of an explicit diagnostic label, rather than the phrasing of the label, that elicits the greatest impact on stigma (45, 46). In particular, vignettes of people with schizophrenia were associated with greater fear, anger, blame, and perceived danger when a diagnostic label was not provided, while these responses did not differ significantly when person-first and identity-first labels were used (46). Likewise, videos of autistic adults are typically rated more favorably when the person’s diagnosis is disclosed (12), regardless of whether person-first or identity-first language is used (10).

In order to emphasize a data-driven approach, no specific a priori hypotheses were generated for the qualitative portion of this study, though we expected differences in the themes used to describe diagnostic labels for autism, schizophrenia, and a general diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 533 college undergraduates aged 18–63 (M = 21.22, SD = 5.67) were recruited from the University of Texas at Dallas. Four participants with an IQ below 80, as estimated by the Reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test 3 [WRAT3; (47)], were excluded from analysis, resulting in a final sample of 529 participants (MIQ = 109.26). Participants were predominantly female (78%) and a plurality were White (43%), with the remaining participants identifying as Asian (40%), Black (7%), American Indian/Alaska Native (1%), or other races (9%). To better approximate a general population sample, participants were not screened for psychological or psychiatric conditions. Participants received course credit for their participation. All aspects of this protocol were approved by the UT Dallas Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants completed the WRAT3 and several computerized questionnaires assessing their perceptions of different diagnostic labels, along with an open-ended question regarding their thoughts about, and exposure to, each label. Participants were randomly assigned to a survey condition in which the wording of each measure was modified to feature one of eight labels: four related to autism (AUT; person with autism, person with autism spectrum disorder, person with Asperger’s, or autistic person), two related to schizophrenia (SCZ; person with schizophrenia or schizophrenic person), and two related to a general clinical condition (CDX; person with a clinical diagnosis or person with a clinical disorder). These labels enabled the comparison of perceptions of: (1) person-first relative to identity-first language; (2) autism-related labels to a distinct clinical condition also characterized by social difficulties, schizophrenia; and (3) autism and schizophrenia labels to a more general clinical condition. The inclusion of the general clinical label allowed us to determine whether autism and schizophrenia are perceived more positively or negatively relative to the invocation of clinical diagnoses more generally. Due to the larger number of autism-related labels relative to schizophrenia and general labels, the sample size of participants assigned to autism-related labels was larger than that of the other two categories (NAUT = 269, NSCZ = 129, and NCDX = 130).

Measures

Stigma questionnaires

The attributes and reactions scale (AAR)

The AAR (35) is a five-point Likert scale originally designed to measure attitudes toward schizophrenia and depression. In the first part of this measure, participants were given eight stigma-related behavioral attributes (unpredictable, lacking self-control, aggressive, frightening, dangerous, needy, dependent on others, and helpless) and asked to rate the extent to which each attribute applied to a person with the assigned diagnostic label, with higher scores indicating greater agreement. Due to a technical error, ratings for “aggressive” were not collected. Responses were averaged across two subscales (35): perceived dangerousness and perceived dependency.

For the second portion of this measure, participants were given nine emotional labels (fear, uneasiness, feelings of insecurity, pity, empathy, desire to help, anger, ridicule, and irritation) and asked to indicate the degree to which they would respond in such a way toward a person with the given label, with higher scores indicating a more likely emotional reaction. Responses were averaged to form three subscales (35): fear, pity, and anger. The behavioral attributes portion of this scale showed strong internal consistency across all diagnostic categories (αAUT = 0.819, αSCZ = 0.841, and αCDX = 0.811), while the emotional reactions portion showed lower, but acceptable internal consistency (αAUT = 0.701, αSCZ = 0.635, and αCDX = 0.648).

The prejudice scale

The Prejudice Scale (36) is an 18-item scale developed to measure negative attitudes toward schizophrenia. The scale was adapted in this study by replacing “schizophrenia” with each of the eight tested labels. Participants were shown items reflecting prejudiced attitudes toward the assigned label [e.g., “(Label) patients/patients with (label) should be kept in hospitals”] and answered either “I agree” or “I disagree” for each statement. Scores of either 1 or 2 were assigned to each response based on agreement or disagreement, with higher scores indicating more negative attitudes toward the label. A total score was generated by summing individual item scores (36), with possible scores ranging from 18 to 36. Internal consistency for the overall measure was low to modest across groups (αAUT = 0.433, αSCZ = 0.610, and αCDX = 0.426).

The social distance scale (SDS)

The SDS (48) is a six item Likert scale developed to assess stigma toward autistic individuals and adapted here to include each of the eight labels. Participants were shown 6 items assessing their willingness to form hypothetical social relationships with a person with each label [e.g., “How willing would you be to make friends with a person with (label)?”]. Responses were scored on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating a lower willingness to interact. Scores on each item were summed to form a composite score, with possible scores ranging from 6 to 24. This measure showed strong internal consistency within each diagnostic category (αAUT = 0.824, αSCZ = 0.803, and αCDX = 0.811).

Open ended question

Participants were also given an open-ended question about their assigned label, which formed the basis for a qualitative analysis. Participants were asked “what do you think of when you hear the word(s) (label)?” Open-ended questions were administered privately via computer, and participants were given as much time to respond as needed. Responses ranged from 0 to 788 characters in length, with a mean length of 136.34 characters (SD: 111.03), and eight participants providing no response.

Analysis plan

Quantitative analysis

Preliminary one-way ANOVAs were conducted to determine where person-first and identity-first labels were perceived differently within each diagnostic condition. Summary scores on each of the three stigma questionnaires did not differ significantly between any of the 4 labels within the autism-associated labels, nor did they differ between the 2 schizophrenia-associated labels or between the 2 general clinical diagnosis labels (Supplementary Figures 1–3). Subsequent analyses therefore were conducted at the level of diagnosis (i.e., labels within each of the three diagnostic conditions were combined). A one-way ANOVA was then used to assess whether summary scores on the seven stigma measures differed for autism, schizophrenia, and a general clinical condition. Significant findings were followed up with post hoc Tukey tests for multiple comparisons. Due to the large number of analyses performed, the significance cutoff was adjusted to 0.01.

Qualitative analysis

Because quantitative results did not differ between the different labels for each condition, qualitative analyses focused on each condition collapsed across labels (for an overview of the most common codes for all 8 labels, see Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, a thematic analysis was conducted to gain further insight concerning perceptions of autism, schizophrenia, and a general clinical condition, and to highlight differences in how participants describe these conditions. This method was chosen due to its ability to provide a rich analysis of large qualitative datasets, as well as its recent use within autism research (49, 50). Responses to open-ended questions were aggregated and themes were identified and coded by the first author based on the six-step approach to thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (51, 52). First, all responses were given an initial read-through by the first author to gain familiarity with the data prior to coding. Next, initial codes for the data were generated in a data-driven fashion using QDA Miner (53). Initial codes were created by identifying frequently occurring patterns of responses across the dataset. Similar codes were then clustered and organized into themes and sub-themes, which were further refined and simplified to eliminate any redundancies and minimize overlap. Once finalized, themes were named based on the shared narrative they conveyed. Codes, themes, and sub-themes were reviewed by both authors, and consensus was reached for any areas of disagreement.

Results

Quantitative analysis

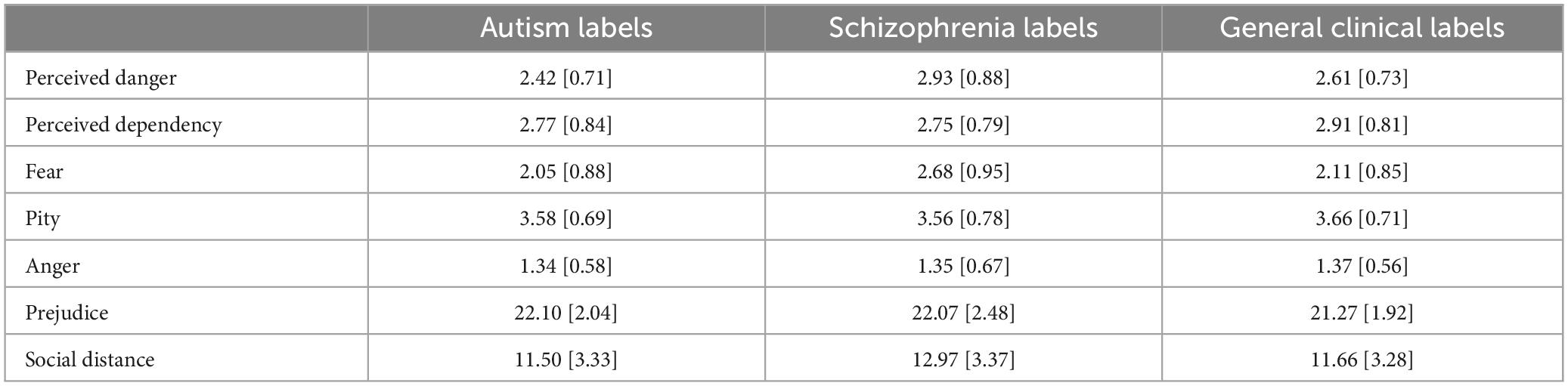

Means and Standard deviations (SDs) for the three label conditions are presented in Table 1. On the AAR, perceptions of danger differed significantly between diagnostic labels [F(2,526) = 19.77, p < 0.001], with greater danger attributed to schizophrenia compared to autism (p < 0.001) and a general clinical condition (p = 0.002). A similar pattern was found for fear [F(2,526) = 22.56, p < 0.001], with participants reporting greater feelings of fear in response to schizophrenia compared to autism and a general clinical condition (ps < 0.001). Perceived dependency did not differ significantly across diagnostic conditions [F(2,526) = 1.63, p = 0.197], nor did feelings of pity or anger (ps > 0.417).

Groups differed significantly for scores on the Prejudice Scale, [F(2,526) = 7.35, p = 0.001]. Both schizophrenia (p = 0.007) and autism (p = 0.001) were associated with more prejudice than the general clinical condition, but prejudice did not differ significantly between schizophrenia and autism (p = 0.988). However, many group differences were present at the individual item level for this measure, with participants believing that people with schizophrenia are more dangerous, untrustworthy, and pose greater harm to children, and reporting greater opposition to having a relative marry a person with schizophrenia, compared to an autistic person (ps < 0.001) or a person with a general clinical condition (ps < 0.01). Compared to schizophrenia, participants also believed that autism was more visibly detectable, less likely to require hospitalization, had greater potential for treatment and recovery, and benefited more from psychotherapy and pharmacological interventions, and showed more favorable attitudes toward having an autistic neighbor (ps < 0.01). On the SDS, schizophrenia was associated with greater stigma [F(2,526) = 8.97, p < 0.001], with participants endorsing a significantly larger social distance to schizophrenia relative to both autism (p < 0.001) and a general clinical condition (p = 0.005).

Qualitative analysis

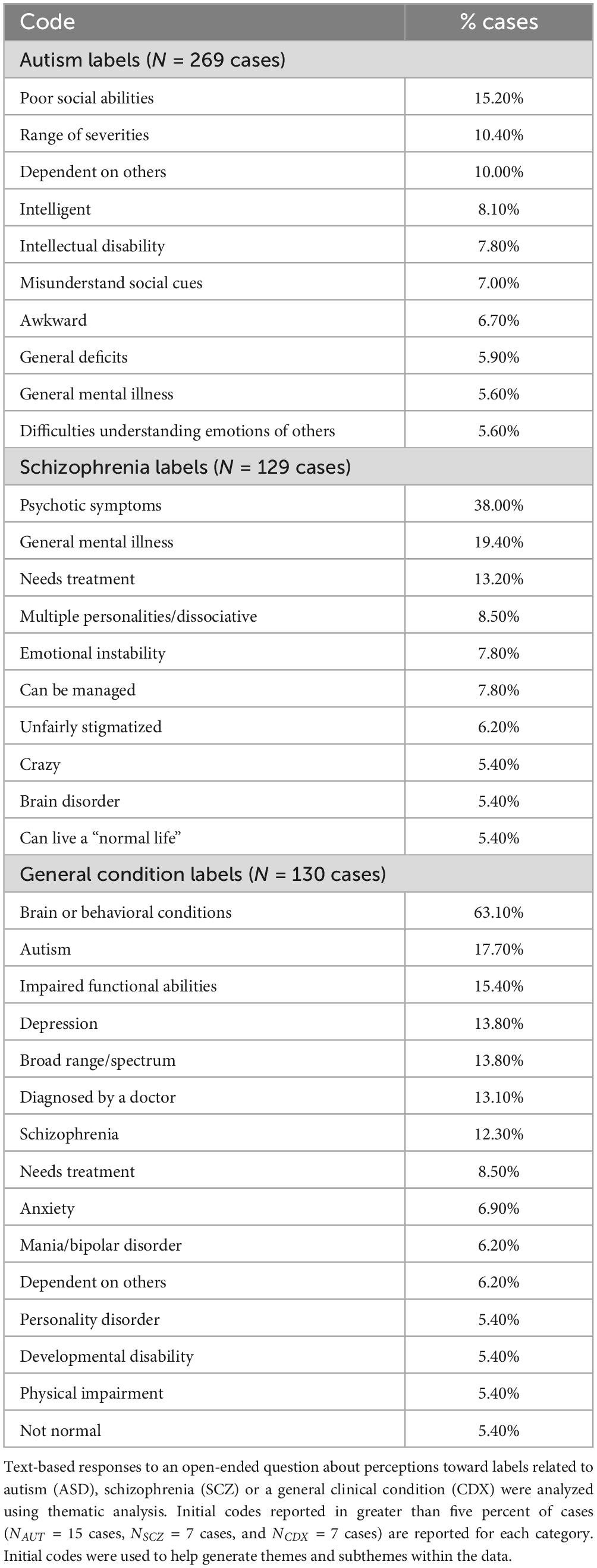

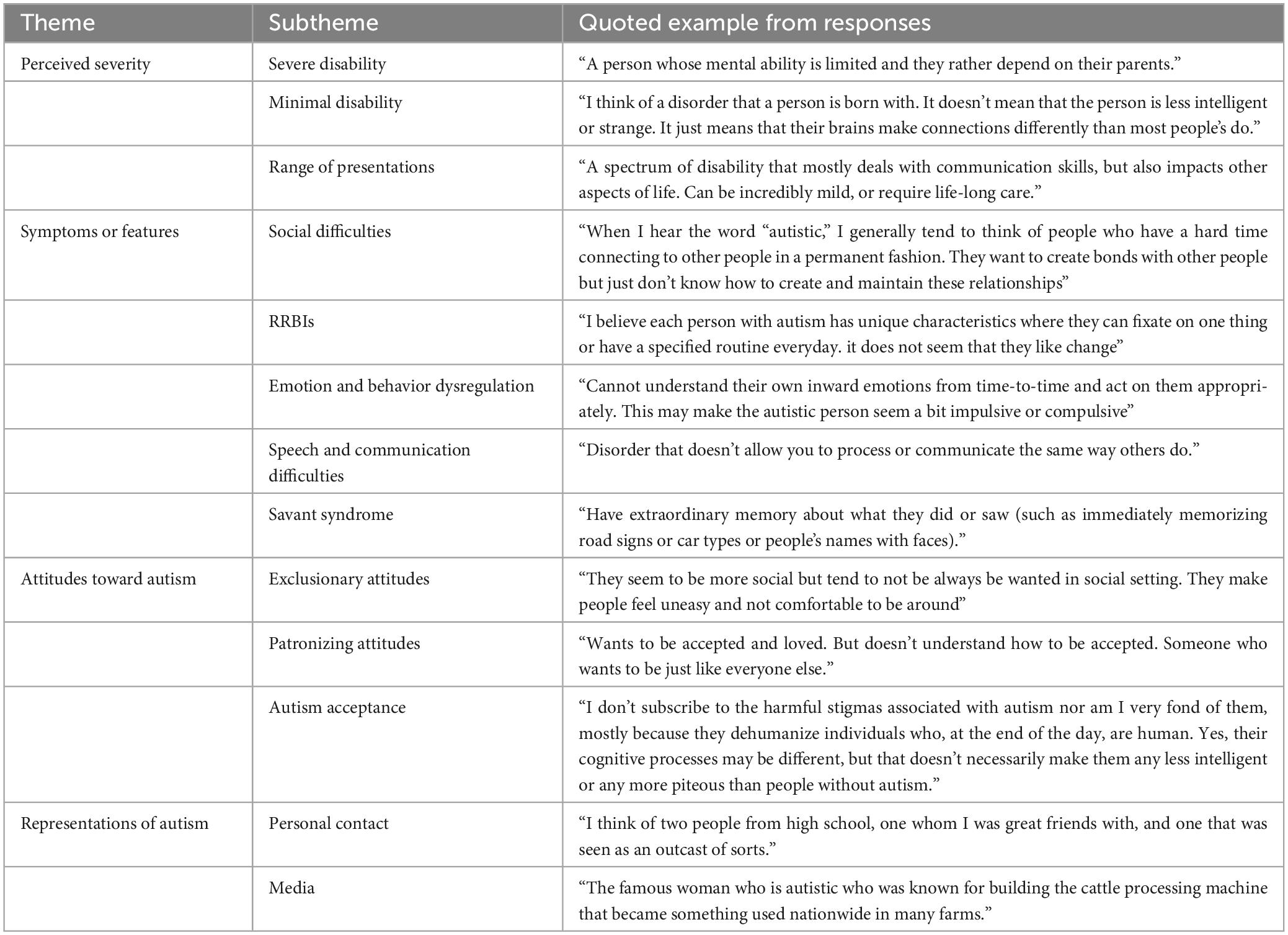

Autism

A total of 88 initial codes were generated for autism, with each code occurring in <1–15% of cases. These codes reflected a wide range of perceptions, with the most frequently occurring codes (Table 2) focusing on poor social abilities (15%), a range of severities (10%), and dependence on others (10%). Initial codes and their context within the data were used to generate four themes: (1) perceived severity, (2) symptoms or features, (3) attitudes toward autism, and (4) representations of autism. Each theme was further divided into subthemes. Full themes and subthemes, along with representative responses, are reported in Table 3.

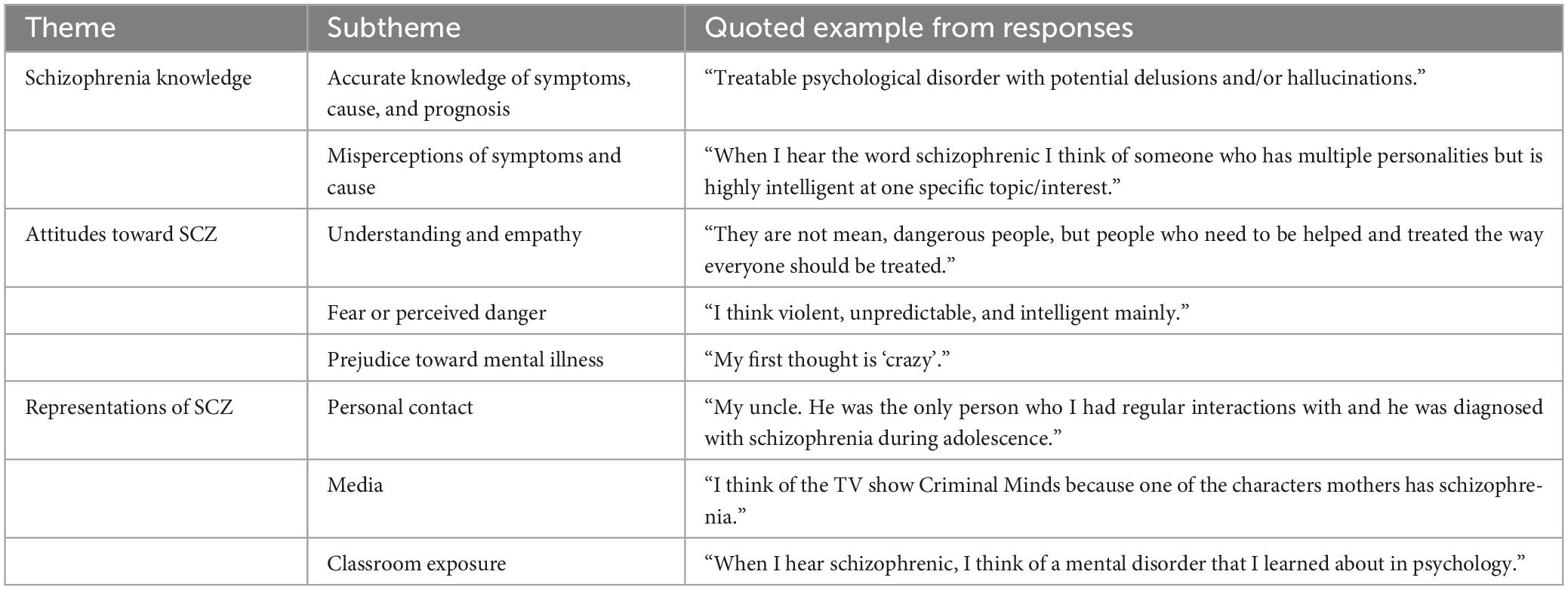

Schizophrenia

Open-ended responses for schizophrenia labels were used to generate 86 initial codes, which appeared within <1–38% of cases. Psychotic symptoms (38%), general mental illness (19%), and the need for treatment (13%) were among the most frequently occurring codes (Table 2). These codes and their associated responses centered around three general themes: (1) schizophrenia knowledge, (2) attitudes toward schizophrenia, and (3) representations of schizophrenia. These themes and their respective subthemes, along with representative responses, are reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Themes and subthemes within open-ended responses for schizophrenia labels, with text examples.

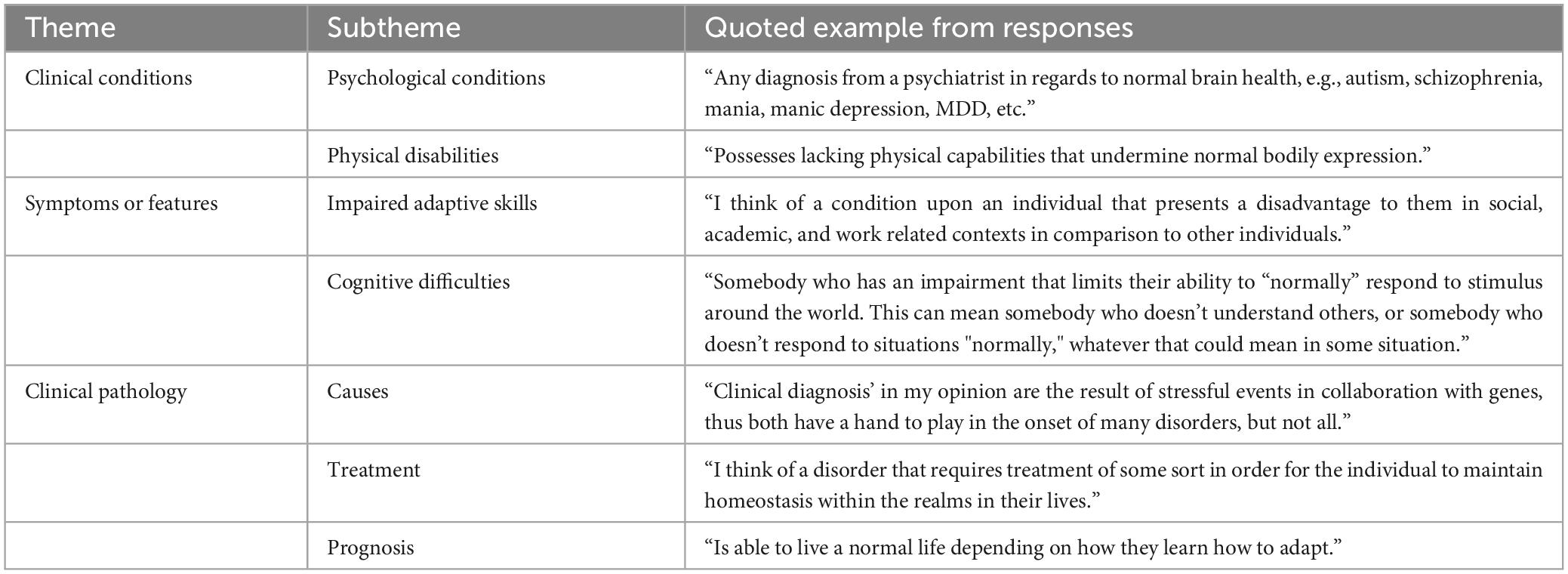

General clinical condition

Participant responses for general clinical labels produced 62 initial codes, which appeared within 1 to 63% of cases. References to brain or behavioral conditions (63%), autism (18%), and impaired functional abilities (15%) were among the most frequent codes for these labels. These codes and the responses in which they occurred were used to generate three broader themes: (1) clinical conditions, (2) symptoms or features, and (3) clinical pathology. These themes were divided into subthemes, which are reported in Table 5, along with representative responses.

Table 5. Themes and subthemes within open-ended responses for general clinical labels, with text examples.

Discussion

The current study used a mixed-methods approach to compare stigma between autism, schizophrenia, and a generic clinical condition. Quantitative results indicated greater prejudice toward autism and schizophrenia than the generic clinical condition, with schizophrenia differentiated from autism by being associated with perceptions of danger and fear, and a greater preference for social distance than from autism. Qualitative results supported and expanded these findings, with autism described in greater depth but with less cohesion than the other conditions, and schizophrenia more commonly described with references to danger and more frequent uses of derogatory terms for mental illness.

A secondary aim of the study was to compare stigma toward clinical conditions labeled with person-first language (e.g., “person with autism”) relative to identity-first language (e.g., “autistic person”). Language choices for autism and other clinical conditions are often intensely debated and discussed, as use of person-first versus identity-first language can reflect ideological differences that may affect conceptualizations and biases (54). However, preliminary examination indicated that stigma did not differ between person-first and identity-first language, either for autism or schizophrenia, nor did it differ between different labels of the autism spectrum (“autism,” “on the spectrum,” “Asperger’s”), and thus subsequent quantitative analyses were pursued after collapsing across person-first and identity first-labels. The lack of a language effect here aligns with a previous study that found that referring to autistic people with person-first or identify-first language does not affect the first impressions they receive from non-autistic observers (12), as well as research suggesting that it is the lack of a label, rather than person-first or identity-first language, that most contributes to stigma toward schizophrenia (46). Broader language use surrounding disability, however, still influences perpetuation of stigma in other ways (54), and it is possible that the use of person-first and identity-first language may have differing effects on those to whom the label is attributed Because preferred terminology has been the subject of recent debate within disability communities, with the preferences of disabled people differing from those of clinicians and stakeholders (55, 56), future research examining the effect of person-first and identity-first language on self-esteem and internalized stigma may offer greater explanation to the potential impact of differing terminologies.

Although stigma did not differ among labels within each clinical condition, it did differ between the conditions themselves in a number of ways. First, autism and schizophrenia were ascribed more stigma than a generically labeled clinical condition. This suggests that autism and schizophrenia are more stigmatized conditions than clinical conditions are generally, with each exceeding the baseline of stigma attributed to a non-specified clinical status. However, stigmatizing attitudes may also be generated to a greater degree when a specific diagnostic label is provided compared to a generic one. Encountering the terms “autism” or “schizophrenia” may trigger certain stereotypes, encourage consideration of specific knowledge and (mis)information, and inspire personal reflection on experiences with each condition. In contrast, a generic clinical label may not be associated with specific enough experience or information to generate high levels of stigma. Supporting this interpretation, the thematic analysis of the qualitative data indicated that the general clinical condition did not elicit as many discernable attitudes or references to first-hand exposure as did participant descriptions of autism and schizophrenia. This suggests that discrete clinical labels may play a central role in the development of stigma by providing categories that can be linked to specific attitudes, information, and biases.

Second, both quantitative and qualitative analyses suggested important differences in the stigma ascribed to autism and schizophrenia. Descriptions of autism were more detailed and wide-ranging than those of schizophrenia, covering more concepts, characteristics, and attitudes. This may reflect greater familiarity with autism than schizophrenia, both interpersonally and from broader cultural messaging, awareness campaigns, and media portrayals. Given comparable prevalence estimates for autism and schizophrenia of about 1% (57, 58)−at least until recent reported increases for autism (59)−greater familiarity with autism is likely not driven by substantially higher cases of autism within communities than schizophrenia. Rather, it may reflect increasing awareness, acceptance, and inclusion of autism that has not occurred to the same degree for schizophrenia (60). This disparity in stigma may also be echoed in diagnostic disclosure decisions. Although disclosing one’s autism can be a fraught decision for many autistic people that often depends on many internal and external factors (61), disclosure of schizophrenia may be especially perilous given rampant biases, beliefs, and misinformation about the condition (62). Disparities in disclosure between the two conditions may in some respects be a reflection of disparities in the stigma attached to them.

Over time, increases in disclosure can demystify clinical conditions, facilitate personal exposure, and help reduce stigma (63), yet findings from this study underscore reasons people may be hesitant to disclose a schizophrenia diagnosis. Although misconceptions were common for both autism and schizophrenia, with wide variability in participant understanding and acceptance of autism, schizophrenia was uniquely characterized by misinformation concerning propensity for violence and disparaging comments about mental illness. This pattern was especially prevalent within the quantitative data, with participants reporting similar levels of pity, anger, and perceived dependency toward both autism and schizophrenia, but associating schizophrenia with significantly greater fear, perceived danger, untrustworthiness, and potential to harm children. Perceived danger, which is more frequently attributed to schizophrenia than other conditions (33), is a strong predictor of stigma (64) and may underlie the persistent stigma attached to schizophrenia (65). Indeed, while overall prejudice did not differ significantly between conditions, participants were more hesitant to interact with a hypothetical person with schizophrenia than an autistic person, even for less intimate interactions. This is consistent with previous literature reporting greater social distance for schizophrenia than autism (30, 33), and highlights the need for improved education and targeted initiatives to counter stigma about schizophrenia (66).

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings reported here. Most notably, the sample−while large−consisted exclusively of university students, who generally are more inclusive and progressive about disability and mental health differences than the general population (67, 68). Participants were also racially diverse, and younger and more educated than the general population. Because schizophrenia is often diagnosed in early to mid-adulthood (57), while autism is typically diagnosed in childhood (69), it is possible that participants may have had less exposure to schizophrenia than autism. However, many participants in both the autism and schizophrenia conditions described personal contacts with both autistic people and people with schizophrenia, and literature suggests that reported contact with autistic people and people with schizophrenia may occur at similar rates in adults (33). Therefore, it is uncertain whether exposure to the two conditions may have impacted the reported findings. Participants were recruited through the university’s psychology research pool, meaning that the majority of these individuals were actively enrolled in a psychology course and may have been exposed to ideas about autism and schizophrenia through their coursework. This may explain the unexpected, but relatively frequent references to autism and schizophrenia in responses to the control labels. Thus, the stigma reported here for autism and schizophrenia may not reflect stigma in the population more broadly, and may be a conservative estimate of stigma that would be found in a more representative sample.

While the current study was underpowered to test for differences based on participant age, it is possible that these results may not generalize to an older sample of raters, and future research should aim to characterize the effects of age on perceptions of autism and schizophrenia. Further, this study should not be taken as a comprehensive examination of attitudes and beliefs about autism and schizophrenia. Although the mixed method approach used here provided deeper and more nuanced information concerning the nature of stigma attributed to the two conditions, the measures used were limited, and the lack of inclusion of other clinical conditions precluded the opportunity to examine how autism and schizophrenia are perceived relative to other types of disability and conditions. A within-subjects comparison of quantitative and qualitative accounts of stigma toward these labels may offer greater clarity regarding the relationship between one’s perceptions of a label and their associated social attitudes.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current study provides quantitative and qualitative evidence that attitudes about autism and schizophrenia vary widely among participants. Although many emphasized the importance of understanding, acceptance, and inclusion, negative attitudes and misinformation were also common. In particular, results indicated that schizophrenia remains a highly stigmatized condition, driven primarily by participants’ beliefs concerning danger and fear that was not present in attitudes about autism. Countering these misconceptions, reducing stigma, and promoting inclusion should be important priorities for educators and clinical practitioners.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/3k6zj/?view_only=681901d6f3f44de1a5da2f021ce4f41b.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of Texas at Dallas Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualization, Writing−original draft, Writing−review and editing. NS: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing−review and editing, Writing−original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by the American Psychological Foundation’s Visionary Grant Program (PI: Jones).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1263525/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity - Erving Goffman. New Jersey: Prentice Hall (1963).

2. Frost DM. Social stigma and its consequences for the socially stigmatized. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. (2011) 5:824–39.

3. Herek GM, McLemore KA. Sexual prejudice. Annu Rev Psychol. (2013) 64:309–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826

4. Araujo AGR, da Silva MA, Bandeira PFR, Gillespie-Lynch K, Zanon RB. Stigma and knowledge about autism in Brazil: a psychometric and intervention study. Autism. (2023) doi: 10.1177/13623613231168917 [Epub ahead of print].

5. Kim SY, Cheon JE, Gillespie-Lynch K, Kim YH. Is autism stigma higher in South Korea than the United States? Examining cultural tightness, intergroup bias, and concerns about heredity as contributors to heightened autism stigma. Autism. (2022) 26:460–72. doi: 10.1177/13623613211029520

6. Obeid R, Daou N, DeNigris D, Shane-Simpson C, Brooks PJ, Gillespie-Lynch KA. Cross-cultural comparison of knowledge and stigma associated with autism spectrum disorder among college students in Lebanon and the United States. J Autism Dev Disord. (2015) 45:3520–36. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2499-1

7. White D, Hillier A, Frye A, Makrez E. College students’ knowledge and attitudes towards students on the autism spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord. (2019) 49:2699–705. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2818-1

8. Grossman RB. Judgments of social awkwardness from brief exposure to children with and without high-functioning autism. Autism. (2015) 19:580–7. doi: 10.1177/1362361314536937

9. Sasson NJ, Faso DJ, Nugent J, Lovell S, Kennedy DP, Grossman RB. Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:40700. doi: 10.1038/srep40700

10. Morrison KE, DeBrabander KM, Faso DJ, Sasson NJ. Variability in first impressions of autistic adults made by neurotypical raters is driven more by characteristics of the rater than by characteristics of autistic adults. Autism. (2019) 23:1817–29. doi: 10.1177/1362361318824104

11. Kim SY, Song DY, Bottema-Beutel K, Gillespie-Lynch K, Cage E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of associations between primarily non-autistic people’s characteristics and attitudes toward autistic people. Autism Res. (2023) 16:441–57. doi: 10.1002/aur.2867

12. Sasson NJ, Morrison KE. First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism. (2019) 23:50–9. doi: 10.1177/1362361317729526

13. Thompson-Hodgetts S, Labonte C, Mazumder R, Phelan S. Helpful or harmful? A scoping review of perceptions and outcomes of autism diagnostic disclosure to others. Res Autism Spectr Disord. (2020) 77:101598.

14. Jones DR, DeBrabander KM, Sasson NJ. Effects of autism acceptance training on explicit and implicit biases toward autism. Autism. (2021) 25:1246–61. doi: 10.1177/1362361320984896

15. Jones DR, Morrison KE, DeBrabander KM, Ackerman RA, Pinkham AE, Sasson NJ. Greater social interest between autistic and non-autistic conversation partners following autism acceptance training for non-autistic people. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:739147. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.739147

16. Scheerer NE, Boucher TQ, Sasson NJ, Iarocci G. Effects of an educational presentation about autism on high school students’ perceptions of autistic adults. Autism Adulthood. (2022) 4:203–13. doi: 10.1089/aut.2021.0046

17. Gillespie-Lynch K, Bisson JB, Saade S, Obeid R, Kofner B, Harrison AJ, et al. If you want to develop an effective autism training, ask autistic students to help you. Autism. (2022) 26:1082–94. doi: 10.1177/13623613211041006

18. Turnock A, Langley K, Jones CRG. Understanding stigma in autism: a narrative review and theoretical model. Autism Adulthood. (2022) 4:76–91. doi: 10.1089/aut.2021.0005

19. Botha M, Frost DM. Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Soc Ment Health. (2020) 10:20–34.

20. Mitchell P, Sheppard E, Cassidy S. Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. Br J Dev Psychol. (2021) 39:1–18. doi: 10.1111/bjdp.12350

21. Han E, Scior K, Avramides K, Crane L. A systematic review on autistic people’s experiences of stigma and coping strategies. Autism Res. (2022) 15:12–26. doi: 10.1002/aur.2652

22. Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. Autistic adults’ experiences of camouflaging and its perceived impact on mental health. Autism Adulthood. (2021) 3:320–9. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0071

23. Cook J, Hull L, Crane L, Mandy W. Camouflaging in autism: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2021) 89:102080. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102080

24. Sasson NJ, Pinkham AE, Carpenter KL, Belger A. The benefit of directly comparing autism and schizophrenia for revealing mechanisms of social cognitive impairment. J Neurodev Disord. (2011) 3:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11689-010-9068-x

25. Angermeyer MC, Dietrich S. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2006) 113:163–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00699.x

26. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. (1999) 89:1328–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328

28. Stuart H. Media portrayal of mental illness and its treatments: what effect does it have on people with mental illness? CNS Drugs. (2006) 20:99–106. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620020-00002

29. Vahabzadeh A, Wittenauer J, Carr E. Stigma, schizophrenia and the media: exploring changes in the reporting of schizophrenia in major U.S. newspapers. J Psychiatr Pract. (2011) 17:439–46. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000407969.65098.35

30. Jensen CM, Martens CS, Nikolajsen ND, Skytt Gregersen T, Heckmann Marx N, Goldberg Frederiksen M, et al. What do the general population know, believe and feel about individuals with autism and schizophrenia: Results from a comparative survey in Denmark. Autism. (2016) 20:496–508. doi: 10.1177/1362361315593068

31. Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey on the frequency of violent behavior in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Res. (2005) 136:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.06.005

32. Choe JY, Teplin LA, Abram KM. Perpetration of violence, violent victimization, and severe mental illness: balancing public health concerns. Psychiatr Serv. (2008) 59:153–64. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.153

33. Durand-Zaleski I, Scott J, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. A first national survey of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and autism in France. BMC Psychiatry. (2012) 12:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-128

34. Williams K, Foulser A, Tillman KA. Effects of language on social essentialist beliefs and stigma about mental illness. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 44. (2022). Available online at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/92m9h735

35. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The stigma of mental illness: effects of labelling on public attitudes towards people with mental disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (2003) 108:304–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00150.x

36. Hori H, Richards M, Kawamoto Y, Kunugi H. Attitudes toward schizophrenia in the general population, psychiatric staff, physicians, and psychiatrists: a web-based survey in Japan. Psychiatry Res. (2011) 186:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.019

37. Kenny L, Hattersley C, Molins B, Buckley C, Povey C, Pellicano E. Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism. (2016) 20:442–62. doi: 10.1177/1362361315588200

38. Taboas A, Doepke K, Zimmerman C. Preferences for identity-first versus person-first language in a US sample of autism stakeholders. Autism. (2023) 27:565–70. doi: 10.1177/13623613221130845

39. Kite DM, Gullifer J, Tyson GA. Views on the diagnostic labels of autism and Asperger’s disorder and the proposed changes in the DSM. J Autism Dev Disord. (2013) 43:1692–700. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1718-2

40. Jensen ME, Pease EA, Lambert K, Hickman DR, Robinson O, McCoy KT, et al. Championing person-first language: a call to psychiatric mental health nurses. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. (2013) 19:146–51. doi: 10.1177/1078390313489729

41. Mizock L, Dilts G, Sotilleo E, Cherry J. Preferred terminology of people with serious mental illness. Psychol Serv. (2022) doi: 10.1037/ser0000717 [Epub ahead of print].

42. Granello DH, Gorby SR. It’s time for counselors to modify our language: it matters when we call our clients schizophrenics versus people with schizophrenia. J Counsel Dev. (2021) 99:452–61.

43. Gernsbacher MA. Editorial perspective: the use of person-first language in scholarly writing may accentuate stigma. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2017) 58:859–61. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12706

44. Fernandes PT, de Barros NF, Li LM. Stop saying epileptic. Epilepsia. (2009) 50:1280–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01899.x

45. Noble AJ, Marson AG. Should we stop saying epileptic? A comparison of the effect of the terms epileptic and person with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2016) 59:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.03.016

46. Masland SR, Null KE. Effects of diagnostic label construction and gender on stigma about borderline personality disorder. Stigma Health. (2022) 7:89–99.

48. Gillespie-Lynch K, Brooks PJ, Someki F, Obeid R, Shane-Simpson C, Kapp SK, et al. Changing college students’ conceptions of autism: an online training to increase knowledge and decrease stigma. J Autism Dev Disord. (2015) 45:2553–66. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2422-9

49. Botha M, Cage E. Autism research is in crisis: A mixed method study of researcher’s constructions of autistic people and autism research. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:1050897. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1050897

50. Crompton CJ, Hallett S, Ropar D, Flynn E, Fletcher-Watson S. ’I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism. (2020) 24:1438–48. doi: 10.1177/1362361320908976

54. Bottema-Beutel K, Kapp SK, Lester JN, Sasson NJ, Hand BN. Avoiding ableist language: suggestions for autism researchers. Autism Adulthood. (2021) 3:18–29. doi: 10.1089/aut.2020.0014

55. Beresford P. ‘Mad’, Mad studies and advancing inclusive resistance. Disabil Soc (2020) 35:1337–42.

56. Botha M, Hanlon J, Williams GL. Does language matter? identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: a response to Vivanti. J Autism Dev Disord. (2023) 53:870–8. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w

57. Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. (2005) 2:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141

58. Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, Ibrahim A, Durkin MS, Saxena S, et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. (2022) 15:778–90. doi: 10.1002/aur.2696

59. Shaw KA, Bilder DA, McArthur D, Williams AR, Amoakohene E, Bakian AV, et al. Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2023) 72:1–15. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7201a1

60. Grinker RR. Autism, “stigma,” disability a shifting historical terrain. Curr Anthropol. (2020) 61:S55–S67.

61. Love AMA, Edwards C, Cai RY, Gibbs V. Using experience sampling methodology to capture disclosure opportunities for autistic adults. Autism Adulthood. (2023). [Epub ahead of print].

62. Hampson ME, Watt BD, Hicks RE. Impacts of stigma and discrimination in the workplace on people living with psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. (2020) 20:288. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02614-z

63. Rüsch N, Kösters M. Honest, open, proud to support disclosure decisions and to decrease stigma’s impact among people with mental illness: conceptual review and meta-analysis of program efficacy. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2021) 56:1513–26. doi: 10.1007/s00127-021-02076-y

64. Gillespie-Lynch K, Daou N, Obeid R, Reardon S, Khan S, Goldknopf EJ. What contributes to stigma towards autistic university students and students with other diagnoses? J Autism Dev Disord. (2021) 51:459–75. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04556-7

65. Corrigan PW, Rowan D, Green A, Lundin R, River P, Uphoff-Wasowski K, et al. Challenging two mental illness stigmas: personal responsibility and dangerousness. Schizophr Bull. (2002) 28:293–309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006939

66. Morgan AJ, Reavley NJ, Ross A, Too LS, Jorm AF. Interventions to reduce stigma towards people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 103:120–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.017

67. Campbell C, Horowitz J. Does college influence sociopolitical attitudes? Sociol Educ. (2016) 89:40–58.

68. Scior K. Public awareness, attitudes and beliefs regarding intellectual disability: a systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. (2011) 32:2164–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.005

Keywords: autism, schizophrenia, stigma, qualitative, terminology

Citation: Jones DR and Sasson NJ (2023) A mixed method comparison of stigma toward autism and schizophrenia and effects of person-first versus identity-first language. Front. Psychiatry 14:1263525. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1263525

Received: 19 July 2023; Accepted: 29 September 2023;

Published: 27 October 2023.

Edited by:

April Hargreaves, National College of Ireland, IrelandReviewed by:

Alexander Westphal, Yale University, United StatesKatherine Rice Warnell, Texas State University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Jones and Sasson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Desiree R. Jones, ZHJqb25lc0B1bWQuZWR1

†Present address: Desiree R. Jones, Department of Psychology, The University of Maryland, College Park, College Park, MD, United States

Desiree R. Jones

Desiree R. Jones Noah J. Sasson

Noah J. Sasson