95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Psychiatry , 27 October 2023

Sec. Mood Disorders

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1221746

Kelen Recco1

Kelen Recco1 Gerardo Garcia Bonetto2

Gerardo Garcia Bonetto2 Christian Lupo3

Christian Lupo3 Antonio E. Nardi4

Antonio E. Nardi4 Arnulfo Morales5

Arnulfo Morales5 Claudia Becerra-Palars6

Claudia Becerra-Palars6 Sergio Perocco7

Sergio Perocco7 Alanna Pfau8*

Alanna Pfau8*Introduction: Depressive Disorders are on the rise worldwide. This is also the case in Latin America (LatAm). Treatment-Resistant Depressive Disorder (TRD) poses additional burden to patients with depression. Impacts quality of life (QoL) and other dimensions, and standard of care (SOC) is insufficient to achieve the desired clinical outcomes. Evidence from LatAm is, however, lacking. The present study was devised as a 1-year follow-up of the SOC in TRD patients in LatAm to explore the burden of TRD.

Methods: This was an observational, multinational, longitudinal study. Patients with clinical diagnosis of TRD in LatAm were included in a 1-year follow-up with SOC. Beyond the Sociodemographic characterization, outcome measures were QoL (EQ-5D-5L), disability (Sheehan Disability Scale - SDS), work productivity (Work Productivity and Activity Incapacity Questionnaire: depression - WPAI:D) and depression severity (Patient Health Questionnaire-PHQ9). Patients were assessed every 3-months and comparison was performed based on change from baseline to each visit and end of study (EOS - 12 months).

Results: Patients averaged 48 (± 13.12) years, mostly female (80.9%) and married/consensual union (42.5%) or single patients (34.4%). Despite the SOC treatment, three-quarters of the patients remained symptomatic at EOS, regardless of the significant longitudinal decrease (p ≤ 0.001). Similar trends were found for disability (p ≤ 0.001) -82.2% of the patients reporting work/school disruption at EOS-, percentage of work (34%) and activity impairment (40%) at EOS (p ≤ 0.001) and only 29.2% of patients with depressive severity “none” at EOS (p ≤ 0.001). The results portray the need to improve clinical outcomes in this complex and burdensome disease in LatAm.

Discussion: Here we show that the burden of TRD remains significant in essential dimensions of everyday life at EOS underlining the need for better therapeutic solutions. The improvements in most patients do not provide the desired outcome of return to the state before the condition. Further research should focus on identifying which treatments provide better outcomes in a real-world context.

The impact of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), a severe form of depression, is well-known and documented in literature. This makes MDD one of the most significant contributors to overall disability (1–3), and one of the priorities to be addressed in the next decade. A major concern regarding MDD is the lack of clinical response in a significant proportion of the patients-more than one third- (4–6) over long periods of treatment with Standard of Care (SOC) (7), resulting in Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD). TRD is often defined as a failure to respond to two or more antidepressants at adequate therapeutic doses, over an appropriate period of time, within the current depressive episode (8). However, there is not a clear consensus on the definition, and recent efforts have been made to make it more specific and operational (9). This lack of consensus is an obstacle for robust comparison between trials and hinders essential conclusions on the effectiveness of specific therapeutics on this condition (10). A recent consensus guideline has made some strides in addressing this issue by providing practical and insightful recommendations on how to design and implement clinical trials for TRD set on addressing current and future unmet needs, as well as knowledge gaps, so more structured trials should be expected in the near future (11).

SOC usually includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or even antipsychotics and other non-pharmacological therapies such as psychotherapy (9). The efficacy of current treatments in SOC raises concerns since it is far from the desired outcome. Only around 44% of the TRD patients achieve clinically meaningful response (12). Improvement may potentially be achieved through the inclusion of novel therapeutics that have been shown to present promising results (13–15). Although the diversity of therapeutics and treatment combinations is increasing, the proportion of patients not achieving response or response without remission can be higher than previously mentioned, even in countries such as Italy (16). Moreover, there is no consensus on the best therapeutics to improve clinical outcomes, and real-world studies have provided extensive evidence on this topic (17). Augmentation and combination are frequently used. In some cases, the added potential of including additional therapeutics in the treatment regimen have even proven to be counterproductive-such is the case of atypical antipsychotics-compared to switching to another antidepressant (18). Also, due to the uncertainty of the condition and the possibility of life-threatening outcomes, even in most cases in which response is not obtained, treatment changes seem to be less frequent than maintenance (17). Recent research on new treatment strategies shows the potential and promise of new treatments, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (19), the magnetic seizure therapy as an alternative to electroconvulsive therapy (20), monoaminergic reuptake inhibitor – toludesvenlafaxine- (21), glutamatergic modulators (22–25), deep brain stimulation (26), and others currently being explored to add to the therapeutic arsenal for TRD treatment (27). The current advances in cognitive neuroscience have also brought forward new approaches to managing depression and anxiety, which should contribute to more focused and individualized therapies (28).

As in other conditions, namely psychiatric disorders, clinical outcomes are no longer the only focus of research and intervention. In a context in which patient-centered care is becoming increasingly more present, models that include shared decision-making can improve engagement and subsequent outcomes even in complex populations such as war veterans (29). These models address an identified unmet need concerning patient education (30). TRD patients have more severe clinical presentation than other MDD patients, are more prone to suicidality, have a higher proportion of comorbidities, have higher healthcare resource utilization, resulting in higher economic burden of the disease, and negative outcomes on quality of life (4, 31, 32). The added impact on healthcare resource utilization in patients with TRD, matched with non-TRD patients, have been demonstrated in a population-wide study (33). TRD impacts several dimensions of daily living, such as work impairment, disability and other Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) (4, 34–36). In this regard, the impact on instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) should be considered, which should desirably be returned to the state previous to the episode of MDD/TRD. Previous real-word evidence has shown that outcomes of MDD/TRD are significant in dimensions such as quality of life and disability, and this is more evident in non-responders to treatment (16). The significanlty high indirect effect of absenteeism should not be discarded, as it accounts for 70% of the costs associated with a major depressive episode in a study in Belgium (37).

TRAL (Treatment-Resistant Depression in America Latina) was a multinational study aiming primarily to estimate the prevalence of TRD in LatAm. TRAL generated much needed real-world epidemiological data on MDD and TRD patients under SOC treatment at regional reference sites on multiple dimensions-from clinical to economic, humanistic, quality of life and work productivity dimensions (4, 34, 36, 38). A longitudinal 1-year follow-up of TRD patients under SOC at reference centers in LatAm (phase 2) followed the epidemiological design. Some previously published results from phase 2 of the TRAL study (12) focused more on a clinical characterization and response to SOC of TRD patients, highlighting the unmet needs in TRD treatment in LatAm-mostly associated with low treatment response rates and the proportion of relapses with current SOC. Hence, this is not exclusive toLatAm, as recent efforts in other regions-such as Europe-provided evidence to address the same unmet need (17).

This paper reports on the results obtained from the PROs (quality of life, disability and work impairment) of TRD patients over a 1-year follow-up, as well as some clinical characterization of depression severity. The main objective was to assess the burden of the disease using the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) and work-related activities-beyond the clinical characterization of TRD. By addressing the objectives, TRAL has the potential to close the knowledge gap in LatAm concerning outcomes of SOC. Also, it aims to inform all stakeholders, ensuring that strategies for the regions can be set on solving some of the unmet needs affecting TRD patients in LatAm.

TRAL was a multicenter, multinational, observational study conducted in a real-world setting (October 2017–December 2018) which included regional psychiatric sites from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. A thorough description of TRAL’s methodology can be found in previous publications of the project (12, 39). This study followed a similar approach to other real-world studies set on characterizing the clinical and non-clinical outcomes of TRD based on the routine standard of care (16–18, 33, 40). The importance of real-world evidence in this context should not be understated given the differences between clinical trials and the routine management of TRD patients, in which real-world evidence better depicts the treatment unmet needs. The present analysis refers to the longitudinal analysis of PROs and a depression severity scale over a 1-year follow-up of TRD patients under SOC. SOC was considered as a diagnostic and treatment process that a clinician followed for a certain type of patient, illness, or clinical circumstance according to best available evidence, and that is used in the routine clinical practice. Regional centers were all reference psychiatric treatment sites, as seen in previous publications. From 430 TRD patients clinically diagnosed, 420 patients were included in the follow-up. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study has been previously published (12, 39). For the purpose of this study, TRD was defined as failure to respond to two or more antidepressants at adequate therapeutic doses, over an appropriate period of time, as assessed by in the routine clinical setting. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of TRD based on adequate follow up and treatment with at least 2 antidepressants, and without complete response to treatment [based on Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (37)]. Diagnosis of TRD was based on DSM-V criteria, and on MINI, and considered the study’s TRD definition.

Depression severity was assessed with the Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (41), a 10-item scale with good discrimination between responders and non-responders to antidepressants, to determine response to SOC over a 1-year time span. Based on MADRS, the following variables were calculated: (a) Change of MADRS score from visit 1 (%) – The following formula must be considered:

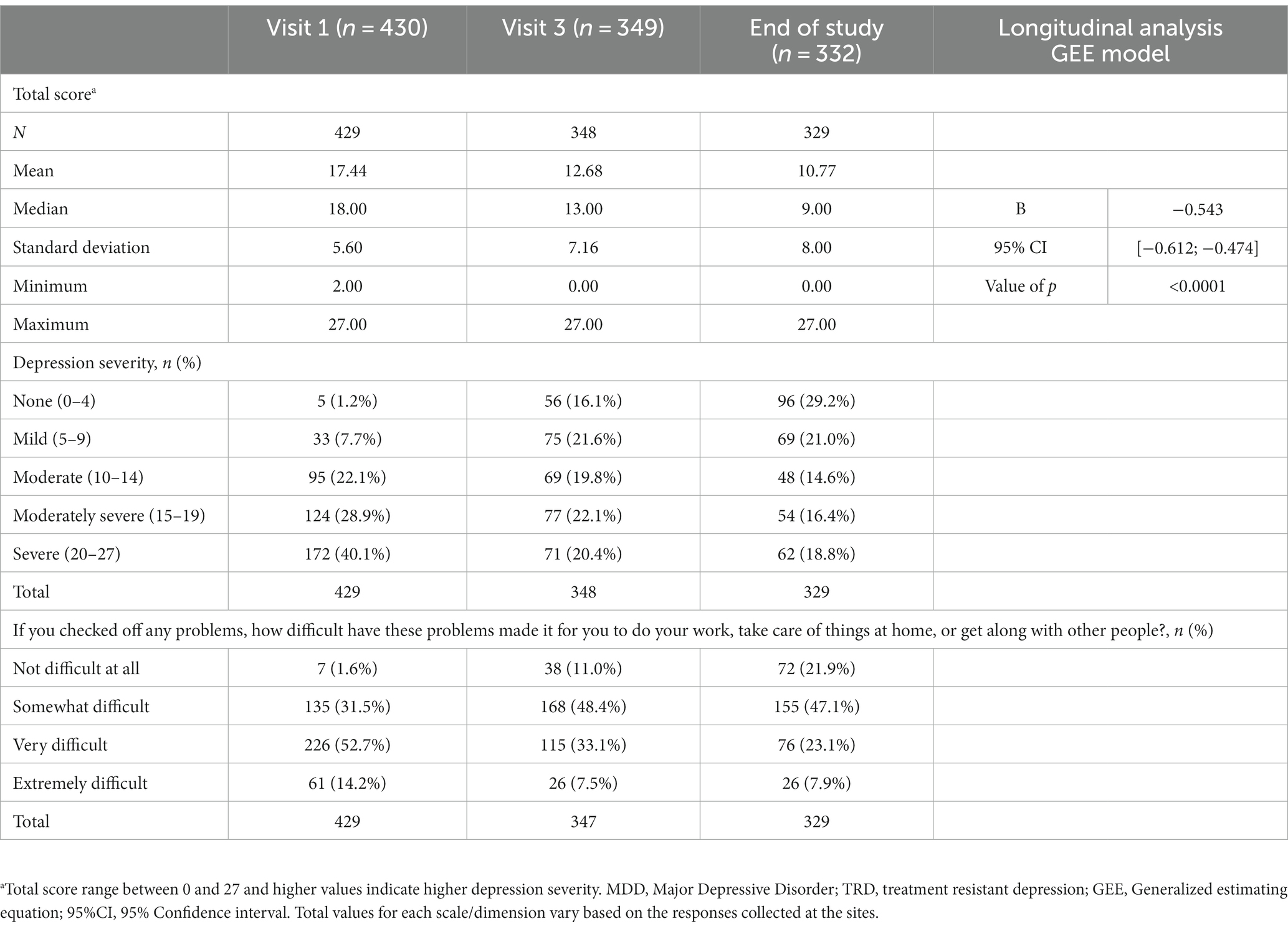

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was also included to assess depression severity (42, 43). This is a 10-item questionnaire that characterizes the severity of symptoms on a 4-point scale (0 – Not at all, 1 – Several days, 2 – More than half the days, 4 – Nearly every day) relative to a pre-defined time frame, usually the last 2 weeks. PHQ-9 can be scored as ‘None’ (score between 0 and 4), ‘Mild’ (score between 5 and 9), ‘Moderate’ (score between 10 and 14), ‘Moderately severe’ (score between 15 and 19) and ‘Severe’ (score between 20 and 27).

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire (WPAI:D) was included to assess the impact of the condition in work related activities (44). Questions relate to the last 7 days. Results can be organized in the following dimensions: Percent work time missed due to depression, Percent impairment while working due to depression, Percent overall work impairment due to depression and Percent activity impairment due to depression. For more information, please refer to previous publications (12).

Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) is a 3-item questionnaire, corresponding to 3 scales, aimed at assessing the level of functional disability from a specific condition (45). Each scale of the SDS questionnaire was recoded according to the following cut-offs: ‘Not at all’ – score equal to 0, ‘Mildly’ – score between 1 and 3, ‘Moderately’ – score between 4 and 6, ‘Markedly’ – score between 7 and 9 and ‘Extremely’ – score equal to 10. Total SDS score was obtained by summing the 3 scales/items that range between 0 (unimpaired) and 30 (highly impaired). A patient that scores 5 or more in any of the scales should be closely monitored since it implies significant functional impairment.

Quality of life was assessed with the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire (46). This is a 5-dimension questionnaire that performs a self-report on Mobility, Self-Care, Usual Activities, Pain/Discomfort, Anxiety/Depression, and a global assessment visual analog 100-point scale. Score were also converted to the EQ-5D-3L score using responses in the EQ-5D-5L index values based on US values set (47).

Sociodemographic and clinical features at baseline were collected and assessed by a physician, while clinical features were again collected every 3 months until the end of the study (12 months from baseline).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by local Independent Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board.

Sample size calculations can be found in previous publications (12). 334 TRD patients were necessary, but 387 were recruited assuming a 15% dropout.

The overall TRD sample in LatAm included 420 patients. From 1,544 MDD patients, 387 were initially planned to be included, but was later increased to 420. When the required number was achieved, the remaining TRD patients were not included.

To reach the sample size and considering that the sites are specialized in the treatment of mental disorders, an estimated prevalence of 21.7% was assumed. Baseline assessment was performed on a sample of 1,544 MDD patients, intended for an even distribution in each country. However, due to recruitment constraints and lengthy regulatory decisions in Brazil, sample size was adjusted and even distribution was not achieved.

Quantitative variables were summarized as mean, median, standard deviation minimum and maximum, and qualitative variables were summarized as absolute frequency and percentage, overall and by TRD and non-TRD subgroups. Longitudinal comparisons on clinical outcomes were performed with a Generalized estimating equation for a 95% Confidence interval. Correlation was performed with the Spearman’s correlation coefficient in accordance with recommended statistical procedures based on sample size and normality assumptions.

There was no imputation of missing data. Statistical significance was set at 5%. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary).

From an initial sample of 1,475 MDD patients enrolled in the study in 4 LatAm countries, 430 were diagnosed with TRD based on the criteria defined by protocol, but only 420 patients with TRD were included in the second phase (1-year follow-up) of the study [for the reason for non-inclusion, please consult previous TRAL publications (12, 39)]. Of these, around 75% completed the 1-year follow-up due to previously disclosed factors.

Sociodemographic characterization suggests that mean age was approximately 48 years (±13.12), predominantly female patients (80.9%) and married or in a consensual union (42.5%) or single patients (34.4%) [see Supplementary Table S1, as seen in previous publications (12)].

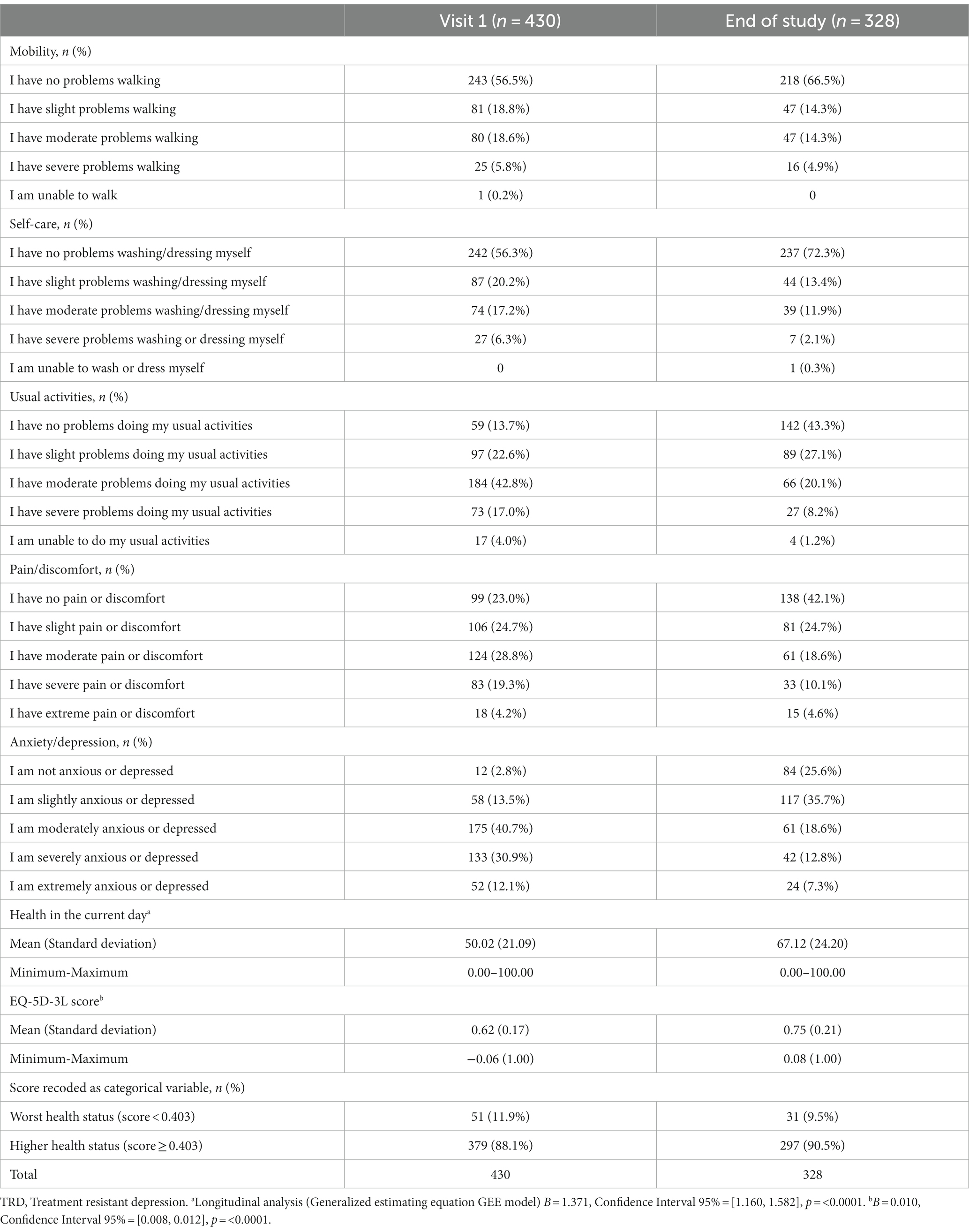

Table 1 presents the results of quality of life assessed through EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, collected at visit 1 for all TRD patients and at the end of study visit (TRD patients included in phase 2 dataset). Approximately 43.5 of the patients reported having problems walking at visit 1 and 33.5% at the end of study. Similarly, 43.7% reported having problems washing or dressing themselves at visit 1 and 27.7% of the phase 2 patients at the end of study. Around 87% at visit 1 and 56.7% at end of study visit of all TRD patients revealed problems doing their usual activities. Approximately 77% of the patients reported having pain or discomfort, while at the end of study the percentages were 57.9%. Almost 3% of the TRD patients did not feel anxious or depressed and 30.9% were severely anxious or depressed at visit 1. At the end of study almost three-quarters (74.4%) reported some anxiety or depression feelings, and the proportion of severe anxious or depressed patients was 12.9%. The patients rated their health at visit 1 with a mean of 50.0 points and 67.1 at the end of study visit, showing statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001) among TRD patients. Overall, although some improvement was observed from visit 1 to end of study visit, the proportion of patients with relevant symptoms is still substantial in all domains.

Table 1. Quality of life – EQ-5D-5L questionnaire over a 1-year follow-up of TRD patients – values per dimension.

The EQ-5D-3L score was computed and the mean value for all TRD patients at visit 1 was 0.62 points and 0.75 at the end of study visit. A statistically significant difference (p < 0.0001) was observed among phase 2 patients, with a mean monthly variation of 0.01 points.

Table 2 reports on the results for disability as assessed through the Sheehan Disability Scale. At visit 1, 17.3% of the patients reported that symptoms extremely disrupted their work/school, 17.4% of the patients reported the symptoms extremely disrupted their social life/leisure activities, while 10.9% reported that symptoms extremely disrupted their family life/home responsibilities (Table 2). At the end of the study, this intensity of symptoms was reported by 11.9, 10.3, and 5.1%, respectively. Overall, symptoms persisted in at least 80% of the patients at last visit, indicating a significant disability.

The mean total score of SDS was 20.3 in TRD patients at visit 1, while in visit 3 TRD patients presented a mean score of 14.8 points and 12.9 points at end of study visit. Statistically significant differences were identified (p < 0.0001) in the longitudinal analysis.

Table 3 present the results of the WPAI questionnaire to identify work impairment. In the 7 days prior to visit 1, the depression led to a median of 17.7% of work time missed, 60.0% impairment while working, 64.0% of overall work impairment and 70.0% of activity impairment. At the end of the study, the median values among TRD patients included in phase 2 were 0.0, 30.0, 30.0 and 40.0% respectively, a significant impairment in most dimensions after a 1-year of SOC with specialized treatment and physicians.

Results based on phase 2 patients, showed that all items of productivity and impairment described above presented a statistically significant result on the longitudinal analysis, with a mean monthly variation of-1.2, −1.6%, −2.0%, and −2.0%, respectively. Regardless, the percentage of work impairment at end of study visit remains high and significant for a relevant proportion of patients-in some cases over 40% of the sample (Table 3).

PHQ-9 was used to assess depression severity and impact on instrumental activities of daily living. At the end of study visit, 31% of the sample still characterized the impact of depression as very difficult/extremely difficult after 1-year under SOC. The mean total score of PHQ-9 at visit 1 was 17.4 points and, according to this scale, 28.9% had moderately severe depression and 40.1% severe depression. The mean score at the end of study for phase 2 patients was 10.8 points but 18.8% of these patients were still classified as severe, and 16.4% as moderately severe. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.0001) across the visits were identified, with a mean monthly variation of-0.5 points (Table 4).

Table 4. Reported analysis of TRD patients 1-year follow-up with questionnaire on patient’s health (PHQ-9).

As presented in Table 5, there was a statistically significant and positive correlation between the MADRS and PHQ-9 scores at visit 1 and also at the end of study visit, with positive and strong correlation at visit 1 (rs = 0.639, p < 0.0001) and again at end of study visit (rs = 0.894, p < 0.0001).

These results are consistent with the ones found and previously published (12) for the main clinical outcomes of the TRAL project, in which severity of depression was still present in a significant proportion of TRD patients. Moreover, the proportion of patients achieving response was well under 50%.

At the end of study visit, the impact of TRD was still considered to be significant in the patients’ assessment in multiple dimensions. Work impairment is a clear outcome in this context. The statistically significant reduction of disability scores should be noted, but the proportion of patients still reporting noticeable disability after one year of follow-up should not be underestimated. Lastly, the impact of TRD in quality of life remains significant at the end of study, although the study found a statistically significant reduction in the score over the longitudinal analysis.

TRAL was a comprehensive project that provided relevant and much needed data on the epidemiological characterization of TRD in the region. Beyond this, clinical features and outcomes in this setting were also the focus of the cross-sectional (39, 48) and longitudinal analyses (12). Although PROs have increased in importance for RWD generation, these were commonly not included and longitudinally analyzed. The most salient results of the current longitudinal analysis show that regardless of the statistically significant reduction in some of the dimensions, the burden of the disease after 1-year of SOC remains significant, namely in severity of the symptoms, disability, quality of life and work-impairment. Given this, and in accordance with the cross-sectional stage of this project, the unmet need concerning the lack of evidence in LatAm on epidemiological data and burden of the disease in TRD patients was addressed.

The first key finding from the study identifies another unmet need in the region. Current SOC does not accomplish the level of psychosocial and clinical outcomes desired in TRD patients, even under direct supervision of specialized psychiatrists and on permanent clinical follow-up at reference sites. This had already been stated in other TRAL publications (12), but the present results obtained for QoL, disability and work impairment underline these conclusions. SOC fails to provide TRD patients with the necessary return to pre-disease status (34, 35). Previous research identified diminished proportion of TRD patients that achieved a clinical response (slightly over 40%). Present results corroborate such claims since almost 50% of patients under SOC after 1-year follow-up still present moderate to severe depressive symptomatology (PHQ-9). Other publications identified that the severity clinically depressive symptoms was associated with a higher burden of the disease (49). Concomitantly, TRD patients incur much higher healthcare expenditure compared to MDD and to controls. A European study found that TRD patients elicit significantly higher healthcare costs, with worse quality of life and higher work productivity costs (34). Results obtained with SOC were subpar and hence newer therapies with better efficacy are needed.

The simultaneous utilization of PHQ-9 and MADRS showed a high correlation. Research with novel therapies for the treatment of TRD had shown the consistency of positive clinical outcomes using both scales as efficacy tools (50, 51). Concerning the lack of consensus on both the clinical definition of TRD (8, 52) and clinical outcomes (response, relapse and remission) assessment, consistent results between two instruments increases the methodological soundness.

The present results obtained in QoL, disability and Work-impairment instruments are also of note. Although there was a statistically significant improvement in QoL (EQ-5D) over time, the scores obtained are still distanced from the normative scores (47, 53). TRD patients’ results after 1-year of SOC are closer to MDD patients reference values, far from the desired outcome, representing a very negative outcome in QoL. The same can be stated for disability. On average, these patients remain with moderate disability after 1-year. However, the improvement seems to be statistically significant. Concerning work-impairment, improvement is visible in a portion of the sample, but the detrimental impact in the work performance remains, in line with previous research (54, 55). This study reveals that despite improvements observed in quality of life, work impairment and disability outcomes after 1-year of SOC among TRD patients, the management of patients still needs to be optimized.

The primary TRAL publication focused on the clinical outcomes of SOC treatment, which provided a solid depiction of current trends and unmet need in LatAm, this study has several strengths. Beyond the use of clinically validated instruments, sampling was adequately defined, and the diversity of reference centers and locations attest for the generalization potential to LatAm, although the same is not recommended at country-level (12). The use of real-world data is both a positive feature and a challenge. The variability of treatment protocols and therapies in the study centers limit the inferences that can be performed on the effectiveness of a specific treatment. The same can be said for the clinical presentation of the patients, as disease severity at baseline or the time from diagnosis were not considered as co-variates in the longitudinal analysis. Nevertheless, this also increases the heterogeneity of patient profiles and allows for a broader characterization of real-world practice. The drop-out from baseline to the end-of-study visit is around 23%, which although expected in these patients may have artificially incremented the efficacy of SOC.

Future TRAL publications will increase the knowledge in this regard, but currently available publications and the present results clearly underline the unmet needs concerning current SOC. Previous publications (39) showed the increased burden in all analyzed dimensions-from an economic to a more humanistic perspective-in the lives of TRD compared to other MDD (56). Healthcare decision-makers should analyze these data and promote a set of measures to increase the availability of other treatment options, since the burden of TRD is not only clear in a clinical standpoint, but also poses a significant threat for quality of life and overall living standards of the patients afflicted by this condition. Irrespective of the severity of the clinical presentation of TRD, this prevalent condition with a refractory nature should always be considered an often life-threatening and serious condition.

The current research protocol, as previously stated, was developed to address both epidemiological and burden of disease characterization in TRD patients in LatAm. The current results add to the previously published (12, 48, 57, 58) by addressing different dimensions and for the longitudinal analysis of the outcomes. There are some limitations inherent to the study design that should be mentioned. The sample is not necessarily representative of the region nor of each of the individual countries analyzed since only patients followed regularly and attending routine medical appointments were included. Moreover, and given the discussion surrounding the definition of TRD, and while considering that the definition used in this manuscript was aligned with reference literature (8, 11, 59), it should be assumed that this condition is underdiagnosed even in MDD patients followed at reference treatment centers. The heterogeneity of patient’s profile and clinical management provided by this observational design and the study population is both a strong feature and a limitation of this study. On one hand, it clearly depicts the real-world context of TRD, but on the other hand may have produced data that is incomplete or biased, given the differences between countries, regions and centers. Future research should consider aspects such as a representative sample of the region-which can be achieved by including other countries and a larger sample-, to analyze differences in the outcomes between treatment regimens, and to compare TRD and non-TRD patients over time, which can provide essential evidence of the added burden of TRD and on the clinical complexity of managing patients clinically diagnosed with this condition.

Concerning the implications for the clinical setting, diagnosis remains a concern and this should be addressed. To achieve better diagnostic outcomes, further efforts should be placed in a practical and applicable operational definition of TRD. The considerable burden of TRD, the heterogeneity of patient’s profile, and the diversity of therapeutic options should also lead to a revised approach to patient management, in which individualized, and patient-centric strategies must be considered. Given the outcomes identified in both clinical and non-clinical dimensions in the TRAL project, and lack of response, treatment switching and optimization seems to be a necessity.

Some important measures to decrease the burden of TRD include patient education, increased treatment adherence and seeking earlier help after symptom onset. This has the potential, alongside the training of primary care physicians and more synergies between primary care and psychiatry, to increase early diagnosis and shorten the time from symptom onset to treatment initiation. Given the overall impact of MDD, the significant proportion of patients developing TRD, and both the humanistic and economic burden of this condition, research on this subject should be prioritized to identify best practices and address the major identifies unmet needs.

Overall, the TRAL study highlighted the burden of TRD in LatAm on multiple dimensions, most notably including severe impact in TRD patients’ psychological adjustment, work performance and overall independence in conducting instrumental activities of daily living, as well as low general QoL. After a 1 year of follow-up in TRD patients under SOC, the burden of the disease is still significant, and depressive symptoms afflict a significant proportion of patients. Moreover, the improvement of clinical symptoms obtained with SOC is insufficient. The use of PROs is essential to provide a good depiction of the burden of the disease, and to highlight the increased challenges posed by TRD. The impact of the unmet needs in the treatment of TRD may be reduced with the introduction of novel therapies, as well as earlier diagnoses. Present results should constitute a catalyst for a more profound and robust intervention by all relevant stakeholders involved in the mental healthcare ecosystem. Policy makers, as well as all involved in the process must cooperate to find ways to provide patients with better therapies, facilitating the return to their original condition prior to TRD.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Argentina: 1. Comité Independiente de Ética de Investigación en Salud Prof. Dr. Marcelino Rusculleda, 2. Comité de Bioética e Investigación de la Fundación para el Estudio y Tratamiento de las Enfermedades Mentales (FETEM), 3. CAICI – CIAP Instituto Centralizado de Asistencia e Investigación Clínica Integral – Centro de Investigación y Asistencia en Psiquiatría, 4. Instituto Médico Platense S.A., 5. Comité Independiente de Ética para Ensayo en Farmacología Clínica. Fundación de Estudios Farmacológicos y de Medicamentos Prof. Luis M. Zeiher. Brazil: 1. Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa – CONEP, 2. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Investiga – Instituto de Pesquisa, 3. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Instituto de Psiquiatria da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – IPUB/UFRJ, 4. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Secretaria de Estado da Saúde de Santa Catarina – SES, 5. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio da Universidade Federal do Ceará – UFC, 6. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Instituto de Neurologia de Curitiba, 7. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – UFMG, 8. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal de Pelotas – UPEL, 9. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Hospital Universitário Professor Edgard Santos-UFBA, 10. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul – UFRGS, 11. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo – USP, 12. Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Hospital São José. Colombia: 1. C.E.I. Campo Abierto LTDA, 2. E.S.E. Hospital Mental de Antioquia, 3. Clínica CEIC de la Fundación Centro de Investigación Clínica, CIC, 4. C.E.I. Campo Abierto LTDA. Mexico: 1. Investigación Biomédica para el Desarrollo de Fármacos, S.A. de C.V, 2. Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía Manuel Velazco Suárez, 3. Hospital La Misión, S.A. de C.V., 4. Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, 5. Hospital Central Dr. Ignacio Morones Prieto. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

KR, GB, CL, AN, AM, CB-P, SP, and AP contributed to the conception, design, analysis, interpretation of available data, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed drafts. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors would like to thank our patients and their families for the consent and time dedicated to this study, as well as the teams involved in the study conduction and data collection. Clinical Trial & Consulting Services (CTI) provided statistical analysis support to the TRAL funded by Janssen LatAm. Diogo Morais from Clinical Trial & Consulting Services (CTI) provided medical writing assistance and editorial support with this manuscript, funded by Janssen LatAm. Janssen LatAm participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the content. All the authors had access to all relevant data and participated in writing, review, and approval of this manuscript.

SP was an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical at the time this research was conducted. AP is currently an employee at Janssen Pharmaceutical and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. KR: Principal Site Investigator for Janssen Pharmaceutical research. GB: Research grants from Janssen, Lundbeck, Boehringer. CL: Current Principal Investigator in research studies of Janssen Pharmaceutical. Principal investigator of Laboratories: Novartis, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Servier, AstraZeneca, Bago, Wyeth, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Sunovion, Janssen Pharmaceutical. Participated as speaker for laboratories: Eli Lilly, Servier, Lundbeck, Chobet and Janssen Pharmaceutical. AN: Research grants from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Fundação Carlos Chagas de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and Janssen Pharmaceutical, Inc. AM: Principal Site Investigator at ISSEMyM for Janssen Studies. CB-P: Research grants from the National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt) and Janssen Pharmaceutical, Inc., Astra Zeneca, Armstrong. The authors declare that this study received funding from Janssen LatAm, an affiliate of Janssen, Inc. The funder had the following involvement in the study: Janssen LatAm participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the content. CTI provided medical writing and editorial support funded by Janssen LatAm. Authors received honorarium as investigators in the TRAL study.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Malhi, GS, and Mann, JJ. Depression. Lancet. (2018) 392:2299–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2

2. World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. (2017). 1–24. World Health Organization: Geneva.

3. Kennedy, SH. Core symptoms of major depressive disorder: relevance to diagnosis and treatment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2008) 10:271–7. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.3/shkennedy

4. Mrazek, DA, Hornberger, JC, Altar, CA, and Degtiar, I. A review of the clinical, economic, and societal burden of treatment-resistant depression: 1996–2013. Psychiatr Serv. (2014) 65:977–87. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300059

5. Gaynes, BN, Warden, D, Trivedi, MH, Wisniewski, SR, Fava, M, and Rush, AJ. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. (2009) 60:1439–45. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1439

6. John Rush, A, Trivedi, MH, Wisniewski, SR, Nierenberg, AA, Stewart, JW, Warden, D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. (2006) 163:1905–17. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905

7. Stegenga, BT, Kamphuis, MH, King, M, Nazareth, I, and Geerlings, MI. The natural course and outcome of major depressive disorder in primary care: the PREDICT-NL study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2012) 47:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0317-9

8. Conway, CR, George, MS, and Sackeim, HA. Toward an evidence-based, operational definition of treatment-resistant depression: when enough is enough. JAMA Psychiatry. (2017) 74:9–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2586

9. Bennabi, D, Charpeaud, T, Yrondi, A, Genty, JB, Destouches, S, Lancrenon, S, et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of treatment-resistant depression: French recommendations from experts, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology and the fondation FondaMental. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:262–12. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2237-x

10. Li, CT. Overview of treatment-resistant depression. Prog Brain Res. (2023) 278:7. doi: 10.1016/BS.PBR.2023.03.007

11. Sforzini, L, Worrell, C, Kose, M, Anderson, IM, Aouizerate, B, Arolt, V, et al. A Delphi-method-based consensus guideline for definition of treatment-resistant depression for clinical trials. Mol Psychiatry. (2022) 27:1286–99. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01381-x

12. Caldieraro, MA, Tung, TC, Agudelo Baena, LM, Vilapriño Duprat, M, Corral, RM, Alviso de la Serna, LD, et al. Depression and suicidality severity among TRD patients after 1-year under standard of care: findings from the TRAL study, a multicenter, multinational, observational study in Latin America. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. (2022). doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2022.06.002

13. FDA. FDA briefing document psychopharmacologic drugs advisory committee (PDAC) and drug safety and risk management (DSaRM) Advisory Committee Meeting, November 2, 2018 (2019). 1–135.

14. ICER. Esketamine for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression: Effectiveness and value. Final evidence report prepared for CEPAC. (2019).

15. Wilkinson, ST, Howard, DH, and Busch, SH. Psychiatric practice patterns and barriers to the adoption of Esketamine. JAMA. (2019) 322:1039–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10728

16. Perugi, G, Calò, P, De Filippis, S, Rosso, G, Vita, A, Adami, M, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of 124 Italian patients with treatment resistant depression: a real-world, prospective study. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:769693. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.769693

17. Heerlein, K, Perugi, G, Otte, C, Frodl, T, Degraeve, G, Hagedoorn, W, et al. Real-world evidence from a European cohort study of patients with treatment resistant depression: treatment patterns and clinical outcomes. J Affect Disord. (2021) 290:334–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.073

18. Park, HJ, Park, CM, Woo, JM, Shin, JY, Lee, EK, and Kwon, SH. Real-world data analysis of the clinical and economic burden and risk factors in patients with major depressive disorder with an inadequate response to initial antidepressants. J Med Econ. (2021) 24:589–97. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1918922

19. De, DZ, Robins, PL, Dannhauer, M, Haugen, LM, Port, JD, and Croarkin, PE. Optimizing TMS coil placement approaches for targeting the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in depressed adolescents: an electric field modeling study. Biomedicine. (2023) 11:2320. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11082320

20. Bellini, H, Cretaz, E, Carneiro, AM, da Silva, PHR, dos Santos, LA, Gallucci-Neto, J, et al. Magnetic waves vs. electric shocks: a non-inferiority study of magnetic seizure therapy and electroconvulsive therapy in treatment-resistant depression. Biomedicine. (2023) 11:2150. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11082150

21. Vasiliu, O. Efficacy, Tolerability, and safety of Toludesvenlafaxine for the treatment of major depressive disorder—a narrative review. Pharmaceuticals. (2023) 16:411. doi: 10.3390/ph16030411

22. Dean, RL, Hurducas, C, Hawton, K, Spyridi, S, Cowen, PJ, Hollingsworth, S, et al. Ketamine and other glutamate receptor modulators for depression in adults with unipolar major depressive disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021) 2021:CD011612. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011612.pub3

23. Wang, Y-T, Wang, X-L, Feng, S-T, Chen, N-H, Wang, Z-Z, and Zhang, Y. Novel rapid-acting glutamatergic modulators: targeting the synaptic plasticity in depression. Pharmacol Res. (2021) 171:105761. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105761

24. Khoodoruth, MAS, Estudillo-Guerra, MA, Pacheco-Barrios, K, Nyundo, A, Chapa-Koloffon, G, and Ouanes, S. Glutamatergic system in depression and its role in Neuromodulatory techniques optimization. Front. Psychiatry. (2022) 13:6918. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.886918

25. Henter, ID, De Sousa, RT, and Zarate, CA. Glutamatergic modulators in depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. (2018) 26:307–19. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000183

26. Vila-Merkle, H, González-Martínez, A, Campos-Jiménez, R, Martínez-Ricós, J, Teruel-Martí, V, Lloret, A, et al. Sex differences in amygdalohippocampal oscillations and neuronal activation in a rodent anxiety model and in response to infralimbic deep brain stimulation. Front Behav Neurosci. (2023) 17:2163. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1122163

27. Tanaka, M, and Telegdy, G. Involvement of adrenergic and serotonergic receptors in antidepressant-like effect of urocortin 3 in a modified forced swimming test in mice. Brain Res Bull. (2008) 77:301–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.08.012

28. Adamu, MJ, Qiang, L, Nyatega, CO, Younis, A, Kawuwa, HB, Jabire, AH, et al. Unraveling the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: insights from structural magnetic resonance imaging studies. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1188603. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1188603

29. Allen, CM, and Bray, C. Improving patient-centered care for veterans with treatment-resistant depression using shared decision-making tools. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. (2023) 29:7–14. doi: 10.1177/10783903221141885

30. Shillington, AC, Langenecker, SA, Shelton, RC, Foxworth, P, Allen, L, Rhodes, M, et al. Development of a patient decision aid for treatment resistant depression. J Affect Disord. (2020) 275:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.014

31. Johnston, KM, Powell, LC, Anderson, IM, Szabo, S, and Cline, S. The burden of treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review of the economic and quality of life literature. J Affect Disord. (2019) 242:195–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.045

32. Pilon, D, Sheehan, JJ, Szukis, H, Morrison, L, Zhdanava, M, Lefebvre, P, et al. Is clinician impression of depression symptom severity associated with incremental economic burden in privately insured US patients with treatment resistant depression? J Affect Disord. (2019) 255:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.100

33. Lundberg, J, Cars, T, Lööv, SÅ, Söderling, J, Sundström, J, Tiihonen, J, et al. Association of Treatment-Resistant Depression with Patient Outcomes and Health Care Resource Utilization in a population-wide study. JAMA Psychiatry. (2023) 80:167–75. doi: 10.1001/JAMAPSYCHIATRY.2022.3860

34. Jaffe, DH, Rive, B, and Denee, TR. The humanistic and economic burden of treatment-resistant depression in Europe: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2019) 19:247–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2222-4

35. Dibernardo, A, Lin, X, Zhang, Q, Xiang, J, Lu, L, Jamieson, C, et al. Humanistic outcomes in treatment resistant depression: a secondary analysis of the STAR∗D study. BMC Psychiatry. (2018) 18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1920-7

36. Amos, TB, Tandon, N, Lefebvre, P, Pilon, D, Kamstra, RL, Pivneva, I, et al. Direct and indirect cost burden and change of employment status in treatment-resistant depression: a matched-cohort study using a us commercial claims database. J Clin Psychiatry. (2018) 79:11725. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11725

37. Gillain, B, Degraeve, G, Dreesen, T, De Bruecker, G, Buntinx, E, Beke, D, et al. Real-world treatment patterns, outcomes, resource utilization and costs in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: PATTERN, a retrospective cohort study in Belgium. Pharmacoecon Open. (2022) 6:293–302. doi: 10.1007/s41669-021-00306-2

38. Chow, W, Doane, MJ, Sheehan, J, Larry, A, and Le, H. Economic burden among patients with major depressive disorder: an analysis of healthcare resource use, work productivity, and direct and indirect costs by depression severity. Am J Manag Care. (2019) 76:155–62. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09298

39. Soares, B, Kanevsky, G, Teng, CT, Pérez-Esparza, R, Bonetto, GG, Lacerda, ALT, et al. Prevalence and impact of treatment-resistant depression in Latin America: a prospective, Observational Study. Psychiatric Quarterly. (2021) 92:1797–815. doi: 10.1007/s11126-021-09930-x

40. Pérez-Sola, V, Roca, M, Alonso, J, Gabilondo, A, Hernando, T, Sicras-Mainar, A, et al. Economic impact of treatment-resistant depression: a retrospective observational study. J Affect Disord. (2021) 295:578–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.036

41. Montgomery, SA, and Asberg, M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. (1979) 134:382–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

42. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, and Williams, JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

43. Spitzer, RL, Kroenke, K, and Williams, JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. J Am Med Assoc. (1999) 282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

44. Reilly, MC, Zbrozek, AS, and Dukes, EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics. (1993) 4:353–65. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006

45. Sheehan, KH, and Sheehan, DV. Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the Discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2008) 23:70–83. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f2b4d6

46. Herdman, M, Gudex, C, Lloyd, A, Janssen, M, Kind, P, Parkin, D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. (2011) 20:1727–36. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

47. van Hout, B, Janssen, MF, Feng, Y-S, Kohlmann, T, Busschbach, J, Golicki, D, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. (2012) 15:708–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008

48. Corral, R, Alessandria, H, Agudelo Baena, LM, Ferro, E, Duque, X, Quarantini, L, et al. Suicidality and quality of life in treatment-resistant depression patients in Latin America: secondary interim analysis of the TRAL study. Front Psychiatry. (2022) 13:812938. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.812938

49. Lynch, F, Dickerson, J, O’Keeffe-Rosetti, M, Sengupta, S, Chow, W, and Jaqueline, P. Incremental healthcare costs for persons with treatment resistant depression in managed care organizations. Am J Manag Care. (2020) 1–3.

50. Bahr, R, Lopez, A, and Rey, JA. Intranasal Esketamine (SpravatoTM) for use in treatment-resistant depression in conjunction with an oral antidepressant. P T. (2019) 44:340–75.

51. Hudgens, S, Floden, L, Blackowicz, M, Jamieson, C, Popova, V, Fedgchin, M, et al. Meaningful change in depression symptoms assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Montgomery-Åsberg depression rating scale (MADRS) among patients with treatment resistant depression in two, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled trials of Esketamine nasal spray combined with a new Oral antidepressant. J Affect Disord. (2021) 281:767–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.066

52. Demyttenaere, K, and Van Duppen, Z. The impact of (the concept of) treatment-resistant depression: an opinion review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. (2019) 22:85–92. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyy052

53. Janssen, MF, Szende, A, Cabases, J, Ramos-Goñi, JM, Vilagut, G, and König, HH. Population norms for the EQ-5D-3L: a cross-country analysis of population surveys for 20 countries. Europ J Health Econ. (2019) 20:205–16. doi: 10.1007/s10198-018-0955-5

54. Rizvi, SJ, Grima, E, Tan, M, Rotzinger, S, Lin, P, McIntyre, RS, et al. Treatment-resistant depression in primary care across Canada. Can J Psychiatr. (2014) 59:349–57. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900702

55. Congio, AC, Norcia, M, Urbano, MR, Verri, WA, and Vargas Nunes, SO. Association of clinical features and biomarkers with treatment-resistant depression. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. (2020) 36:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.npbr.2020.02.004

56. Kubitz, N, Mehra, M, Potluri, RC, Garg, N, and Cossrow, N. Characterization of treatment resistant depression episodes in a cohort of patients from a US commercial claims database. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e76882–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076882

57. Vázquez Hernández, JL, Alviso de la Serna, LD, Cruz, C, Becerra Palars, C, Ibarreche Beltran, J, Kanevsky, G, et al. (2023). Prevalence of treatment resistant depression: TRAL study sub analysis in a Mexican sample |. Archivos de Neurociencias. Available at: https://archivosdeneurociencias.org/index.php/ADN/article/view/448 (Accessed June 19, 2023)

58. Cordoba-Rojas, R, Ferro, E, Agudelo Baena, LM, Kanevsky, G, and Cabrera, P. Epidemiology and burden of treatment-resistant depression in Colombia: analysis of the TRAL study. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. (2023). doi: 10.1016/J.RCP.2023.04.009

59. Gaynes, BN, Asher, G, Gartlehner, G, Hoffman, V, Green, J, Boland, JLL, et al. Definition of treatment-resistant depression in the Medicare population. Technology assessment program – technology assessment; project ID: PSYT0816. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) (2018). 115 p.

Keywords: treatment-resistant depressive disorder, longitudinal study, quality of life, standard of care, patient reported outcome measures, Latin America

Citation: Recco K, Bonetto GG, Lupo C, Nardi AE, Morales A, Becerra-Palars C, Perocco S and Pfau A (2023) Treatment-Resistant Depression in America Latina study: one-year follow-up of treatment resistant depression patients under standard of care reveals insights on quality of life, disability, work impairment, and depressive symptoms. Front. Psychiatry. 14:1221746. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1221746

Received: 12 May 2023; Accepted: 03 October 2023;

Published: 27 October 2023.

Edited by:

Rafael Christophe Freire, Queen's University, CanadaReviewed by:

Jie Lei, Peking University Hospital of Stomatology, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Recco, Bonetto, Lupo, Nardi, Morales, Becerra-Palars, Perocco and Pfau. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alanna Pfau, QVBmYXU3QElUUy5KTkouY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.